Engineered carbon limitation after deletion of four Ci-uptake systems in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is compensated by an extensive phenocopy of wild-type acclimation to low CO2 and multilayered Ci regulation.

Abstract

Cyanobacteria have efficient carbon concentration mechanisms and suppress photorespiration in response to inorganic carbon (Ci) limitation. We studied intracellular Ci limitation in the slow-growing CO2/HCO3−-uptake mutant ΔndhD3 (for NADH dehydrogenase subunit D3)/ndhD4 (for NADH dehydrogenase subunit D4)/cmpA (for bicarbonate transport system substrate-binding protein A)/sbtA (for sodium-dependent bicarbonate transporter A): Δ4 mutant of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. When cultivated under high-CO2 conditions, ∆4 phenocopies wild-type metabolic and transcriptomic acclimation responses after the shift from high to low CO2 supply. The ∆4 phenocopy reveals multiple compensation mechanisms and differs from the preacclimation of the transcriptional Ci regulator mutant ∆ndhR (for ndhF3 operon transcriptional regulator). Contrary to the carboxysomeless ∆ccmM (for carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism protein M) mutant, the metabolic photorespiratory burst triggered by shifting to low CO2 is not enhanced in ∆4. However, levels of the photorespiratory intermediates 2-phosphoglycolate and glycine are increased under high CO2. The number of carboxysomes is increased in ∆4 under high-CO2 conditions and appears to be the major contributing factor for the avoidance of photorespiration under intracellular Ci limitation. The ∆4 phenocopy is associated with the deregulation of Ci control, an overreduced cellular state, and limited photooxidative stress. Our data suggest multiple layers of Ci regulation, including inversely regulated modules of antisense RNAs and cognate target messenger RNAs and specific trans-acting small RNAs, such as the posttranscriptional PHOTOSYNTHESIS REGULATORY RNA1 (PsrR1), which shows increased expression in ∆4 and is involved in repressing many photosynthesis genes at the posttranscriptional level. In conclusion, our insights extend the knowledge on the range of compensatory responses of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 to intracellular Ci limitation and may become a valuable reference for improving biofuel production in cyanobacteria, in which Ci is channeled off from central metabolism and may thus become a limiting factor.

Cyanobacteria evolved more than 2.5 billion years ago and shaped the atmosphere by decreasing the CO2 concentration while increasing the proportion of molecular oxygen. In marine environments, cyanobacteria are still important CO2 sinks and contribute significantly to the global carbon cycle (Stuart, 2011) via net fixation of inorganic carbon (Ci). Cyanobacteria are the evolutionary ancestors of all eukaryotic plastids (Mereschkowski, 1905; Deusch et al., 2008; Ochoa de Alda et al., 2014) and serve as prokaryotic models in which to study photosynthesis and plant Ci fixation.

Rubisco catalyzes the central reaction of photosynthetic Ci fixation, in which ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate reacts with CO2 to produce two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3PGA). High levels of atmospheric CO2 in Earth’s early history (Berner, 1990) favored the carboxylation reaction. However, Rubisco also accepts oxygen as a substrate. The oxygenase reaction competes with Ci fixation and produces equimolar amounts of 3PGA and 2-phosphoglycolate (2PG). 2PG is an intracellular toxin that inhibits the Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes phosphofructokinase and triosephosphate isomerase (Kelly and Latzko, 1977; Husic et al., 1987; Norman and Colman, 1991).

Cyanobacteria adapted to decreasing CO2 and increasing oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere by largely avoiding 2PG production via the evolution of an efficient CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) that increases the local CO2 concentration in the vicinity of Rubisco (Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999; Giordano et al., 2005) and by evolving mechanisms for 2PG degradation through photorespiratory 2PG metabolism (Eisenhut et al., 2008a, 2008b). Photorespiratory 2PG metabolism in cyanobacteria involves the canonical photorespiratory cycle that is also active in plants (Bauwe et al., 2010) and regenerates one molecule of 3PGA from two molecules of 2PG. Alternative pathways also contribute to 2PG detoxification by regeneration of 3PGA from glyoxylate or by complete degradation of 2PG to CO2 in some cyanobacteria (Eisenhut et al., 2008b). Photorespiratory 2PG metabolism of cyanobacteria is essential for growth in ambient air (Eisenhut et al., 2008b) and becomes activated when cyanobacteria are shifted from a high-CO2 (HC) to a low-CO2 (LC) environment (Huege et al., 2011; Young et al., 2011; Schwarz et al., 2013). Shifts of CO2 availability are associated with a defined pattern of transient changes in primary metabolite pools, which includes photorespiratory intermediates and has been termed the photorespiratory burst (Klähn et al., 2015).

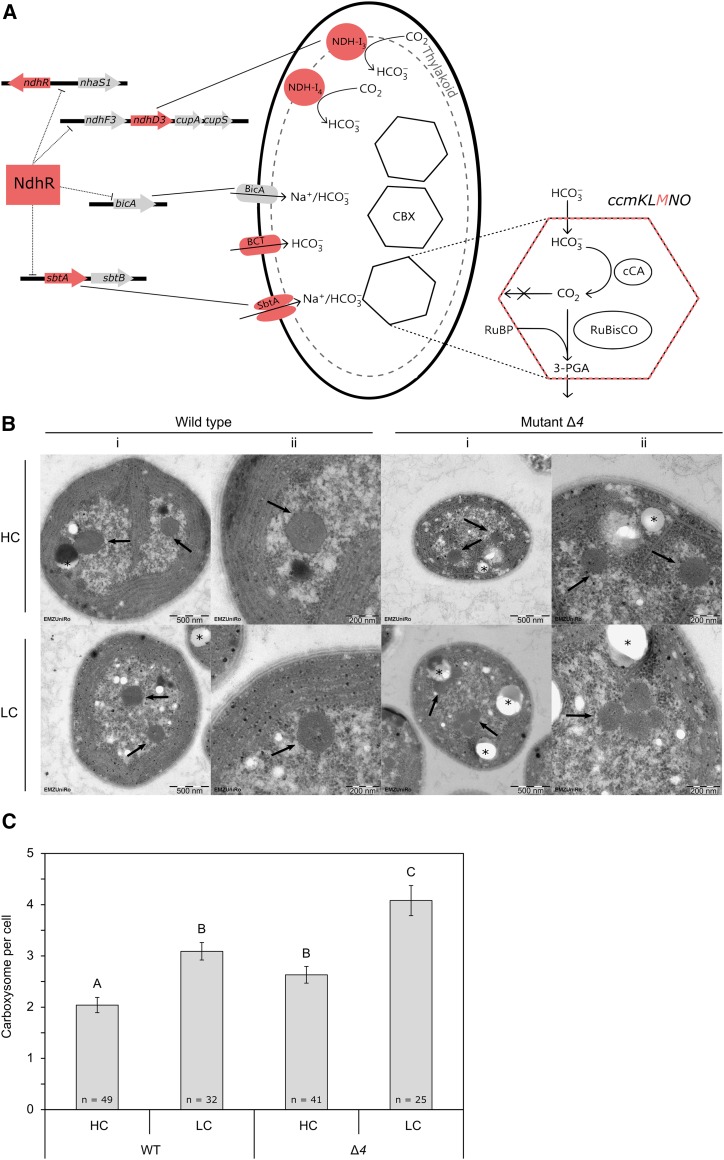

The expression of the CCM is an energy- and nutrient-consuming process that is activated under LC conditions. The CCM consists of two major components, a structural part, the carboxysomes, and a Ci acquisition component comprising several high-affinity CO2- or HCO3−-uptake systems (Fig. 1A). Carboxysomes are bacterial microcompartments that contain Rubisco and carbonic anhydrase within a monolayered protein shell (Kerfeld et al., 2010). Carbonic anhydrase converts HCO3−, which enters the carboxysome from the cytosol, into CO2, which accumulates in the vicinity of Rubisco, allowing carboxylation at saturating CO2 levels. The cytoplasmic HCO3− pool is fed by five CO2/HCO3−-uptake systems in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis 6803): (1) BCT1, a high-affinity HCO3− transporter of the ATP-binding cassette type, which is inducible under LC conditions and encoded by the bicarbonate transport system substrate-binding protein (cmp) ABCD operon (Omata et al., 1999); (2) SbtA, an inducible high-affinity Na+/HCO3− symporter (Shibata et al., 2002); (3) BicA, a low-affinity Na+-dependent HCO3− transporter (Price et al., 2004); (4) NADH dehydrogenase (NDH)-14, a constitutive low-affinity CO2-uptake system (Shibata et al., 2001); and (5) NDH-13, an inducible and high-affinity CO2-uptake system (Ohkawa et al., 2000). Both NDH-13 and NDH-14 are specialized NDH-1 complexes (Battchikova et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

The Synechocystis 6803 mutants of this study and their respective deficiencies. A, The ∆4 mutant is a quadruple carbon transporter mutant that lacks four of the five HCO3−/CO2-uptake systems known in Synechocystis 6803 (Shibata et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2008). The ∆4 mutant is compared with the ∆ndhR mutant (Klähn et al., 2015) and the ΔccmM mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012). NdhR is a central regulator of carbon metabolism in Synechocystis 6803 and, among others, a repressor of ndhD3 and sbtA. NdhR expression is feedback regulated by autorepression. Note that the expression of the deleted genes ΔndhD4 and ΔcmpA, which are part of the NDH-14 and BCT1 transporter complexes, is not controlled by NdhR. CmpA is part of the cmpABCD operon, which is controlled by the transcriptional regulator CmpR. The ΔccmM mutant does not express CcmM, one of the shell proteins of carboxysomes (CBX) that is encoded in the ccmKLMNO operon and serves as a reference mutant with a carboxysomeless phenotype (Hackenberg et al., 2012). (This scheme was modified from Daley et al. [2012] and Rae et al. [2013]). B, Electron micrographs of Synechocystis 6803 wild type and the ∆4 mutant under HC and LC conditions. Arrows indicate carboxysome cross sections within cells. Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) bodies are marked by asterisks. i = 23,000-fold original magnification, and ii = 50,500-fold original magnification. C, Number of carboxysomes in Synechocystis 6803 wild type (WT) and the ∆4 mutant under HC and LC conditions. Each bar represents the average number of carboxysomes per cell, and error bars indicate se. Significant differences between sample groups were assessed by heteroscedastic Student’s t test and are indicated by different letters (P < 0.01).

Expression of the Ci-uptake systems is tightly regulated in cyanobacteria (Burnap et al., 2015; Fig. 1). Genes coding for the Ci-uptake systems are maximally expressed under LC conditions of ambient air and are repressed under HC conditions (Wang et al., 2004). In contrast, genes of the structural components of the CCM are mostly not Ci regulated. Three transcriptional regulators of Ci utilization are known, CyAbrb2 (sll0822), CmpR (sll0030), and NdhR (also known as CcmR, sll1594). CyAbrb2 may balance carbon and nitrogen metabolism (Ishii and Hihara, 2008; Lieman-Hurwitz et al., 2009; Yamauchi et al., 2011; Kaniya et al., 2013). CmpR activates BCT1 expression under LC conditions (Omata et al., 2001). NdhR mainly acts as a repressor under HC conditions (Wang et al., 2004) but may also function as a transcriptional activator (Klähn et al., 2015). In vitro studies have revealed that NdhR and CmpR are targets of metabolic regulation by primary metabolites and photorespiratory intermediates (Nishimura et al., 2008; Daley et al., 2012). As an alternative, Woodger et al. (2007) proposed a regulatory role of the internal bicarbonate pool.

To investigate the impact of carbon uptake systems on the suppression of 2PG production and their importance for LC acclimation and the establishment of a functional CCM, we analyzed genetically engineered carbon limitation in cells of a Synechocystis 6803 Ci-uptake mutant of Ogawa and coworkers. This quadruple mutant ΔndhD3 (for NADH dehydrogenase subunit D3)/ndhD4 (for NADH dehydrogenase subunit D4)/cmpA (for bicarbonate transport system substrate-binding protein A)/sbtA (for sodium-dependent bicarbonate transporter A; ∆sll1733/sll0027/slr0040/slr1512 = Δ4) lacks four of the five Ci-uptake systems (Shibata et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2008). The Δ4 mutant compensates Ci limitation caused by the lack of NdhD3, NdhD4, CmpA, and SbtA by BicA activity and grows in ambient air, although at a reduced rate compared with the Synechocystis 6803 wild type. Here, we present a functional systems analysis of engineered intracellular Ci limitation in the Δ4 mutant and compare it with the wild type, with the regulatory mutant ∆ndhR (∆sll1594; Klähn et al., 2015), and with the carboxysomeless ∆ccmM (∆sll1031) mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012). We compare HC- and LC-grown cells and focus on the integration of primary metabolic pathways, including photorespiration and global transcriptional changes. Thereby, we additionally aim to elucidate whether metabolites and/or bicarbonate pools serve as signals for CCM regulation in vivo. Our data suggest that multiple layers of Ci regulation exist that involve early metabolic and transcriptional responses to changing Ci availability as well as modules of antisense RNAs (asRNAs) or regulatory trans-acting small RNAs (sRNAs) and their mRNA targets.

RESULTS

The Δ4 Mutant Does Not Exhibit the Photorespiratory Burst upon LC Shift

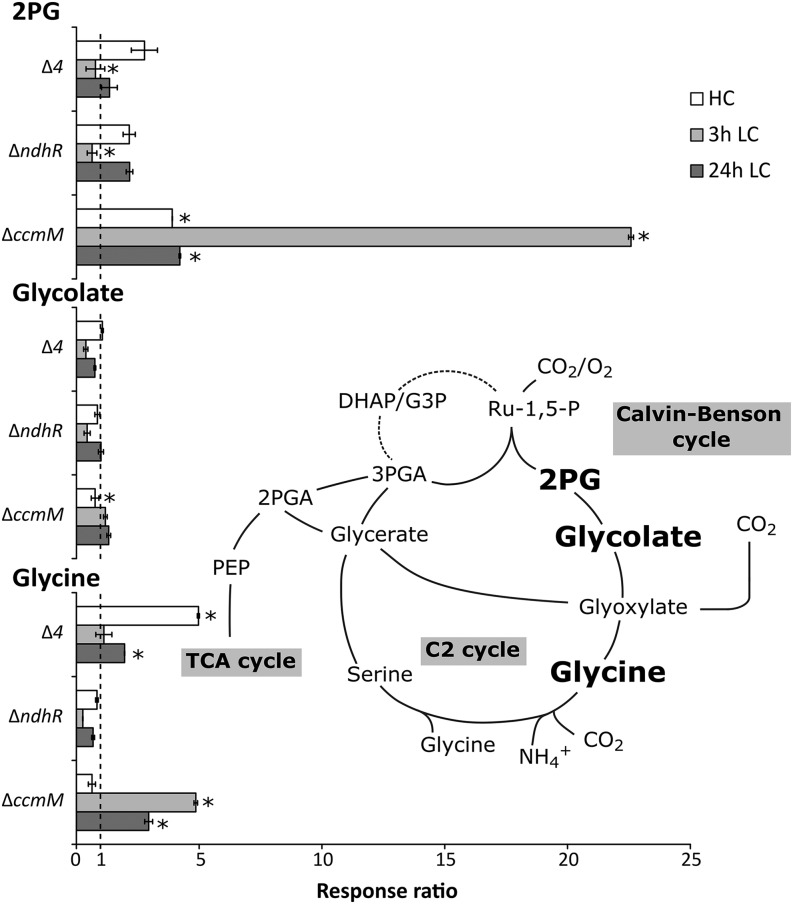

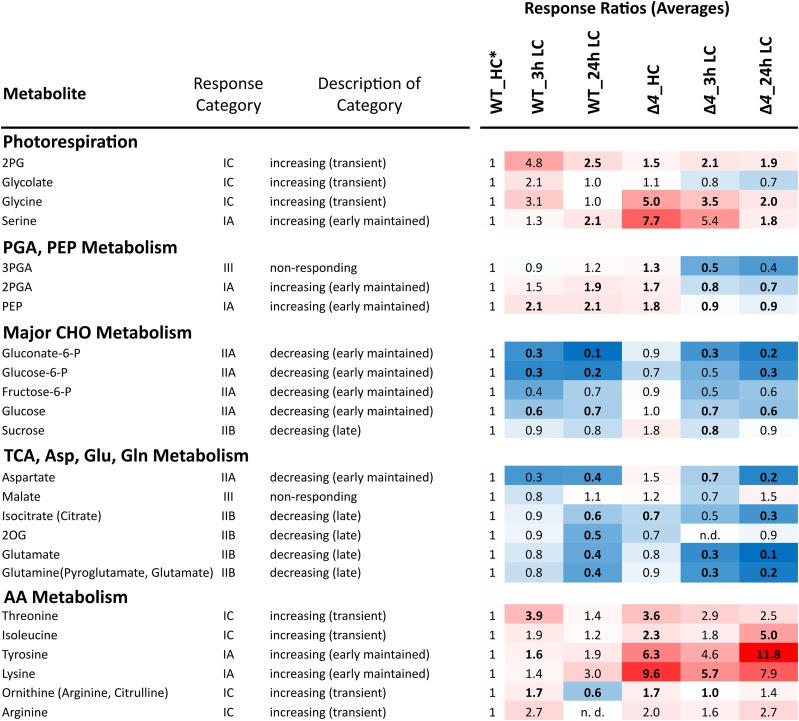

We initially assumed that the lack of most components of the Ci-uptake machinery would create a physiological state opposite to that of the ∆ndhR mutant, which showed higher expression of the Ci-uptake systems under HC conditions (Klähn et al., 2015). Because the ∆4 mutant grows only slowly in the presence of CO2 less than 0.6% (v/v; Xu et al., 2008), we expected increased levels of photorespiratory metabolites under HC conditions and an intensified response after the shift from HC supply to LC supply. Contrary to our expectations, the key metabolites of the photorespiratory C2 cycle, 2PG, glycolate, and Gly, were only slightly increased under HC conditions. They also did not exhibit the typical strong increases upon a shift from HC to LC conditions, indicating an attenuated photorespiratory burst in the ∆4 mutant (Fig. 2). In fact, the response of the Δ4 mutant was similar to the Ci-shift response of the regulatory ΔndhR mutant. However, the carboxysomeless ΔccmM mutant had a phenotype opposite to these two, with a strongly enhanced photorespiratory burst (Fig. 2; ΔccmM and ΔndhR mutant data extracted from Hackenberg et al. [2012] and Klähn et al. [2015]). Surprisingly, Gly and Ser, which close the canonical photorespiratory C2 cycle, accumulated under HC conditions in the ∆4 mutant (Figs. 2 and 3). Additionally, 3PGA, glycerate-2-phosphate (2PGA), and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), which connect the Calvin-Benson cycle to the tricarboxylic acid cycle, increased under HC conditions in the ∆4 mutant. Upon shifting to LC conditions, 3PGA, 2PGA, and PEP decreased significantly in ∆4, contrary to their approximately 2-fold higher accumulation in wild-type or in ∆ndhR cells (Klähn et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Relative pool sizes of metabolites from the photorespiratory C2 cycle in the ∆4 mutant, the Ci-regulatory ΔndhR mutant, and the carboxysomeless ΔccmM mutant compared with the respective Synechocystis 6803 wild-type controls. Each bar represents the response ratio (i.e. the relative pool size of the mutant metabolite pool compared with the respective wild-type controls that were sampled under identical conditions, namely 24 h of HC conditions, 3 h of LC conditions, and 24 h of LC conditions). Error bars indicate se. Data for the ∆ccmM mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012) and ∆ndhR mutant (Klähn et al., 2015) were taken from previous studies. Glyoxylate was not detectable in all experiments. The position of the highlighted C2 cycle metabolites within central carbon metabolism is shown by the inserted pathway scheme. Significant changes in the mutant compared with the wild type are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.05). For complete underlying statistical assessments of the ∆4 mutant and the full set of profiled metabolites, see Supplemental Table S1. TCA, Tricarboxylic acid.

Figure 3.

Overview of Ci-responsive metabolites in the wild type (WT) compared with the ∆4 mutant. The heat map shows response ratios relative to the wild type under HC conditions (*). Metabolites are sorted according to general metabolic context and classified by response category in the wild type (Klähn et al., 2015). Significant differences between the wild type and the ∆4 mutant were assessed by heteroscedastic Student’s t test (P < 0.05; boldface values). For complete underlying statistical assessments and the full set of profiled metabolites, see Supplemental Table S1. AA, Amino acid; CHO, carbohydrate.

The Δ4 Mutant Accumulates Amino Acids upon the LC Shift

The tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates isocitrate/citrate and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) as well as Glu and Gln, which link central carbon to nitrogen assimilation, were depleted compared with the wild type under HC conditions. When exposed to LC, these metabolites are depleted faster and more than in the wild type (Fig. 3). Whereas Asp followed the same general pattern, other amino acids, such as Thr, Ile, Tyr, and Lys, increased in the Δ4 mutant under both HC and LC conditions. Specifically, Tyr and Ile accumulated under long-term LC conditions (Fig. 3). In the wild type, these amino acids increased only transiently 3 h after the shift to LC conditions. In contrast to photorespiratory 2PG and amino acid metabolism, soluble carbohydrate metabolism was largely unchanged in the ∆4 mutant compared with the wild type. Both the wild type and the ∆4 mutant responded to LC supply with rapid and persistent pool size decreases of Glc, Glc-6-P, Fru-6-P, and gluconate-6-phosphate, indicating decreased activity of the oxidative pentose-phosphate cycle (Fig. 3).

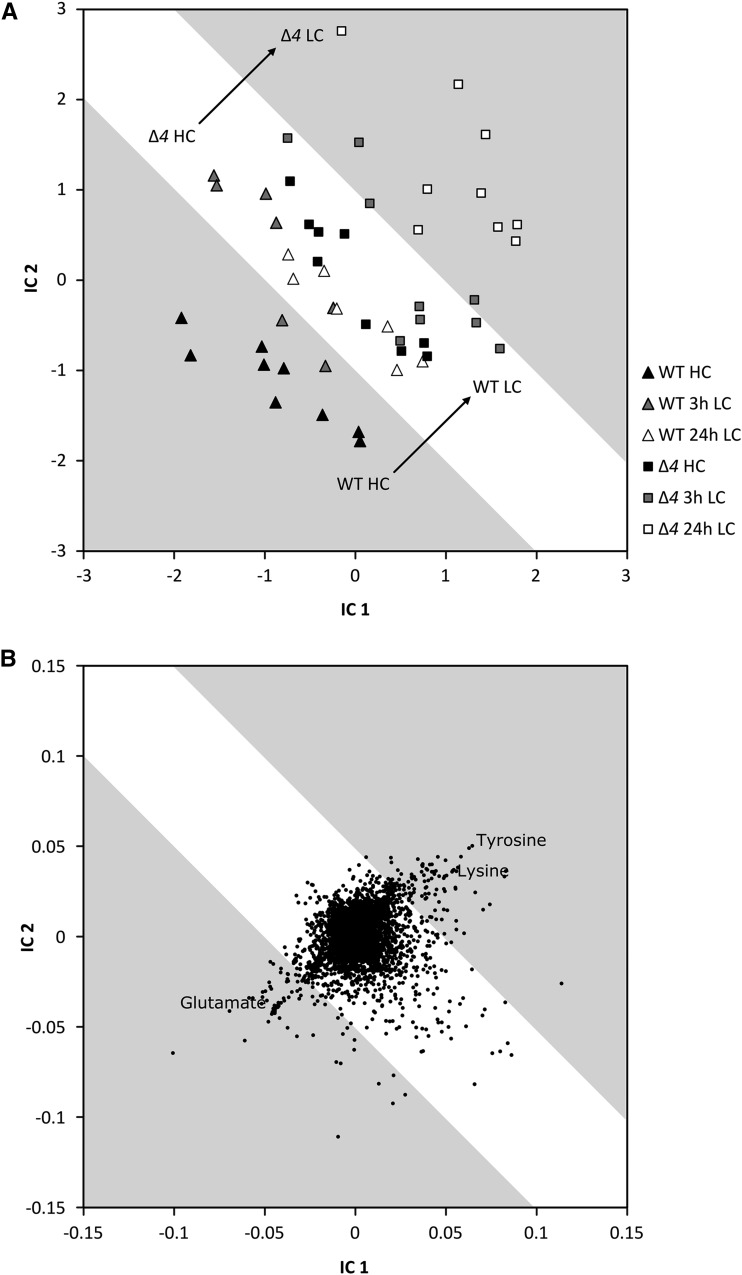

The Metabolome of the Δ4 Mutant under HC Conditions Phenocopies the Wild-Type Metabolome under LC Conditions

The preformed increases of 3PGA, 2PGA, PEP, and Ci-responsive amino acids (Thr, Ile, Lys, and Tyr) implied that the intracellular physiological state of the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions was similar to that of the wild type under LC conditions. To support this hypothesis, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) and subsequent independent component analysis (ICA) of all 9,935 observed mass features, including the 63 identified metabolites (Supplemental Table S1). This nontargeted pattern analysis supported the existence of an extensive metabolic phenocopy (i.e. a partial or full agreement of metabolic pool size changes in response to different environmental or genetic perturbations). The metabolic phenotype of Δ4 mutant samples taken under HC conditions matched with the wild-type samples taken 24 h after a shift to LC supply (Fig. 4A). The metabolites contributing most to the phenocopy are Glu, Tyr, and Lys pools and several Ci-responsive mass spectral tags, which represent yet nonidentified metabolites (Fig. 4B). As expected for a mutant lacking Ci-uptake systems, the Ci-limited state became even more extreme when shifted from HC to LC conditions. All 24-h LC samples of the Δ4 mutant transgressed the limits of wild-type acclimation to LC conditions (Fig. 4A). For example, the changes in key amino acid levels (e.g. Glu and Tyr) exceeded the wild-type response by far (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, other aspects of the physiological state of Δ4 clearly differed from the wild type and the ∆ndhR mutant (Supplemental Fig. S1; compare with PC1).

Figure 4.

Global responses of metabolism to a shift from HC to LC conditions in the wild type (WT) compared with the ∆4 mutant. A, Sample scores plot of a nontargeted ICA based on all observed mass features from gas chromatography-electron ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (GC-EI-TOF-MS) metabolite profiles. Arrows mark the metabolic transition of the wild type (triangles) from HC to LC conditions and the corresponding but displaced transition of the ∆4 mutant (squares). The HC metabolome of the ∆4 mutant (black squares) matches the wild-type metabolome after shifting to LC conditions (white and gray triangles). Regions of metabolic phenocopy and of divergent wild-type and ∆4 mutant metabolism are indicated by white and gray underlay. B, Corresponding loadings plot of metabolites and yet nonidentified mass spectral tag. Changes in the Glu, Lys, and Tyr pools and of several nonidentified mass features contribute most to the HC to LC conditions transition of the wild type and the ∆4 mutant metabolome. The ICA was based on the first five components of a PCA, which covered 46.3% of the total variance of the data set. The data set consists of three independently repeated biological experiments with two to three replicate samples from each culture and condition.

Correlation analysis of the metabolite levels confirmed the metabolic phenocopy of the Δ4 mutant (Supplemental Fig. S2A). The change in pool sizes in the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions relative to the wild type under HC conditions was correlated to the changes in the wild type at 24-h LC conditions relative to the wild type under HC conditions. In comparison, the same metabolite pools from the HC metabolome of the ∆ndhR mutant (Klähn et al., 2015) were not correlated to the respective LC-shift response of the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S2B). However, the extent of the metabolic changes in the Δ4 mutant relative to the wild type under HC conditions was moderate compared with the ΔccmM mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012). The ΔccmM mutant had more depleted carbohydrate pools (e.g. Glc, Suc, and gluconate-6-phosphate) as well as Glu and Asp levels under HC conditions (Hackenberg et al., 2012). Unlike the Δ4 mutant, the ΔccmM mutant did not accumulate 3PGA, PEP, Gly, and Ser. Most of the amino acid pools that were increased in the Δ4 mutant were either decreased (e.g. Gly and Ser) or not detectable in the ΔccmM mutant (e.g. Tyr or Lys; Hackenberg et al., 2012).

Enrichment Analysis Reveals a Broad Transcriptional Phenocopy of LC-Shift Responses in the Δ4 Mutant under HC Conditions

To integrate the observed Ci responses of primary metabolism in the Δ4 mutant relative to the wild type with a system-wide functional assessment of RNA levels, an advanced Synechocystis 6803 microarray was used (Mitschke et al., 2011). The microarray results for the wild type (Supplemental Table S2) in regard to Ci-responsive protein-coding genes (mRNAs) as well as Ci-regulated asRNAs and trans-encoded sRNAs were consistent with previous studies (Wang et al., 2004; Eisenhut et al., 2007; Klähn et al., 2015). Supplemental Data Set S1 provides a genome-wide graphical overview of probe localization and corresponding signal intensities for the wild type and the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions as well as 3 and 24 h after a shift to LC conditions.

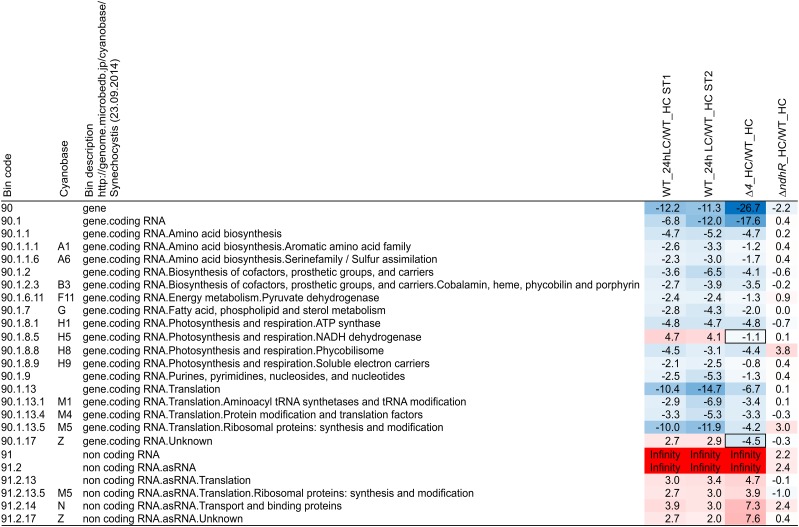

We applied enrichment analysis to the transcriptome data from this and previous studies using the MapMan software suite to identify functional categories (i.e. BINs) of genes showing significantly up- or down-regulated transcripts compared with random samplings of transcripts from noncategory members (Thimm et al., 2004; Usadel et al., 2006). Ci-responsive BINs were highly reproducible (Fig. 5) compared with our preceding study in the wild type at 24 h after the shift from HC to LC conditions (Klähn et al., 2015). The phenocopy of the Δ4 mutant was confirmed at a global functional level and was clearly not established under HC conditions in the ∆ndhR mutant (Fig. 5; Supplemental Table S4).

Figure 5.

Ci-responsive functional categories (BINs) from CyanoBase. The Ci responsiveness of functional categories (i.e. BINs) was analyzed for Synechocystis wild-type (WT) data at 24 h after shifting from HC to LC supply in this study (ST1; Supplemental Table S2) with respect to the wild-type data from a previous study (ST2; Klähn et al., 2015). The phenocopy of the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions is compared with a paralleled functional enrichment analysis of the ∆ndhR mutant under HC conditions from study ST2. All transcript data were normalized to the paired average expression levels of the wild type under HC conditions from the respective studies. Transcript data were averaged from two independently repeated biological shift experiments per genotype. The table contains the PageMan analysis results (i.e. the z-scores of P values from Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected Wilcoxon rank sum tests [Usadel et al., 2006]). Positive z-scores indicate significant up-regulation of transcripts in a given BIN, and negative z-scores indicate preferential down-regulation. High absolute z-score values indicate high significance. The term infinity indicates highly significant z-scores that were beyond exact calculation from the underlying algorithm. Boxed cells in the table indicate BINs that are inversely regulated in the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions compared with the wild type at 24 h after shifting to LC conditions. The table contains Ci-responsive BINs with z-scores of −2 or less (blue) or +2 or more (red) in both studies, ST1 and ST2. The complete set of z-scores including all BINs is provided in Supplemental Table S3.

BINs with down-regulated transcripts in Δ4 relative to the wild type under HC conditions comprised parts of amino acid biosynthesis, specifically the aromatic amino acid, Glu, and Ser families, and parts of energy metabolism, namely the glycolysis and pyruvate dehydrogenase BINs. Moreover, most of the photosynthesis and respiration BINs were part of this category, such as ATP synthase, cytochrome b6/f, both photosystems, phycobilisomes, and the respective photosystem cofactor biosynthesis. Transcripts of the transcription, the translation, and especially the ribosomal protein synthesis and modification BINs were preferentially down-regulated.

Transcripts of the NADH dehydrogenase BIN (Fig. 5) were up-regulated upon the LC shift in wild-type cells. This BIN contains the NDH-13 and NDH-14 CO2-uptake systems, which are defective in the Δ4 mutant. Consistently, this BIN was not part of the Δ4 phenocopy. Contrary to mRNAs, the global asRNA BIN was up-regulated. Specifically, asRNAs of the photosynthesis and respiration, translation, ribosomal protein synthesis and modification, and transport and binding protein BINs were preferentially up-regulated. Three of these asRNA BINs, photosynthesis and respiration, translation, and ribosomal protein synthesis and modification, showed an inverted enrichment pattern compared with their respective mRNA BINs.

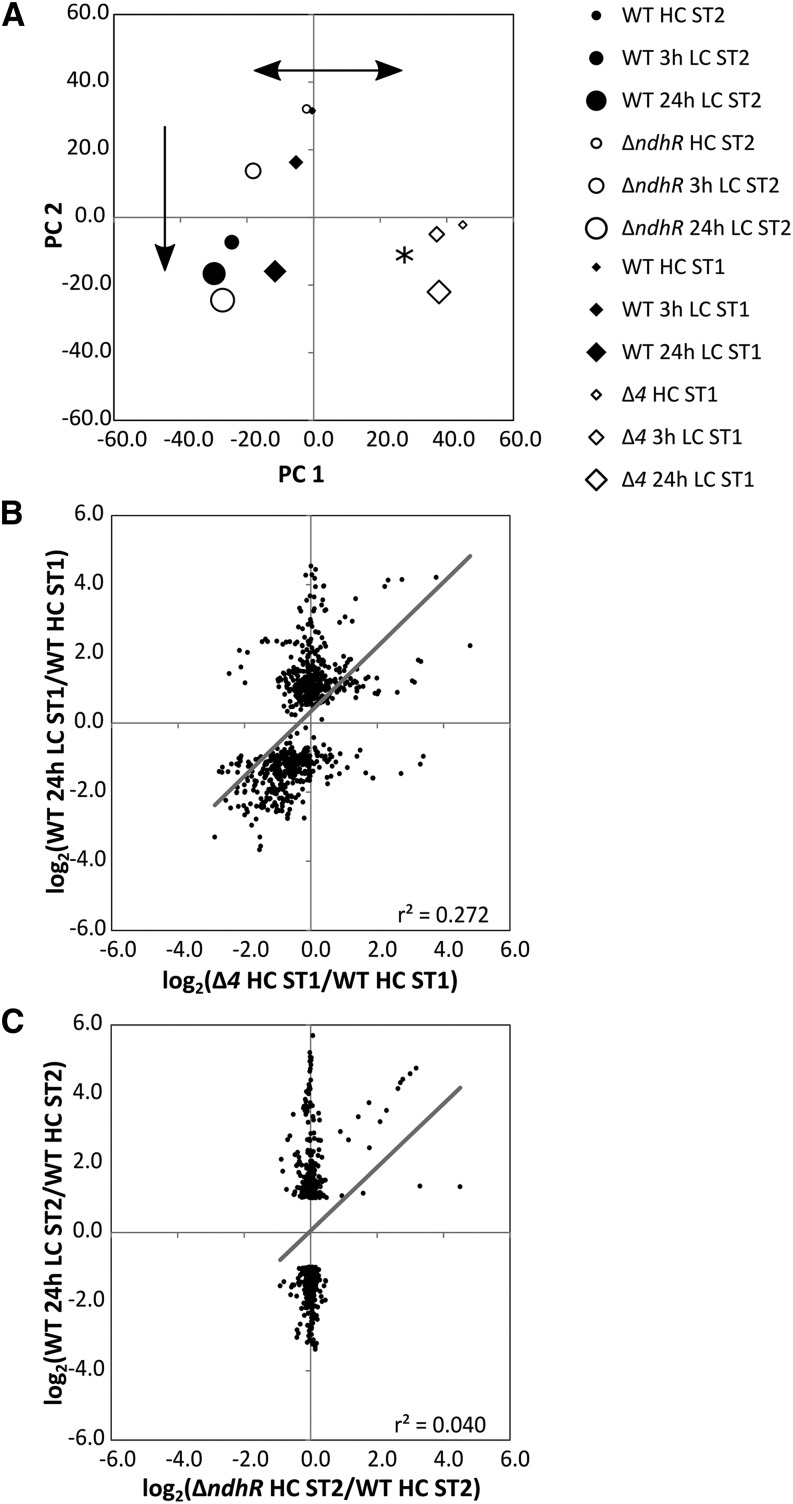

PCA of transcript responses of the wild type, the ∆4 mutant (this study), and the ∆ndhR mutant (Klähn et al., 2015) resulted in a corresponding pattern of changes to that found previously in primary metabolism analysis (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S1). The Δ4 transcriptome differed from those of the wild type and the ∆ndhR mutant under HC conditions (Fig. 6A, PC1), but they had common responses when shifted from an HC supply to an LC supply (Fig. 6A, PC2). However, the Ci responses appeared attenuated in the Δ4 mutant. In contrast to the ∆ndhR mutant, the transcriptional changes in the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions were largely correlated to the LC responses of the wild type. These pattern analyses indicate a broad phenocopy also at the transcriptional level (Fig. 6, B and C).

Figure 6.

Global responses of the wild-type (WT) transcriptome to a shift from HC to LC supply compared with the transcriptional differences of the ∆4 and ∆ndhR mutants. A, PCA scores plot of a nontargeted PCA based on all transcript changes from this study (ST1) compared with an independent previous study, ST2 (Klähn et al., 2015). Arrows mark the constitutive differences of the ∆4 mutant compared with both the wild type and the ∆ndhR mutant as well as the common transitions of the transcriptome from HC to LC supply. A transcriptional phenocopy of the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions is indicated (asterisks). B, Preformed transcriptional changes in the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions compared with the significant wild-type 24-h LC shift response of this study (ST1). Note the partial correlation of both increased and decreased transcripts, which is indicative of a transcriptome phenocopy. C, Preformed transcriptional changes in the ∆ndhR mutant under HC conditions compared with the significant wild-type 24-h LC shift response of study ST2. Note the absence of common down-regulated transcripts and the few correlated up-regulated transcripts that constitute part of the subtle preacclimation of this mutant to LC conditions (Klähn et al., 2015). All transcript data from these analyses were normalized to the paired average expression levels of the wild type under HC conditions from the respective studies. Transcript data were averaged from two independently repeated biological shift experiments per genotype (Supplemental Table S2). Fold changes were regarded significant if the log2 value was −1 or less or +1 or more and the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected P value was P < 0.05.

Transcripts of ATP Synthase Subunits, Nitrogen Metabolism, and Photosynthesis Proteins Are Hallmark Transcripts of the Δ4 Phenocopy of LC-Shifted Wild-Type Cells

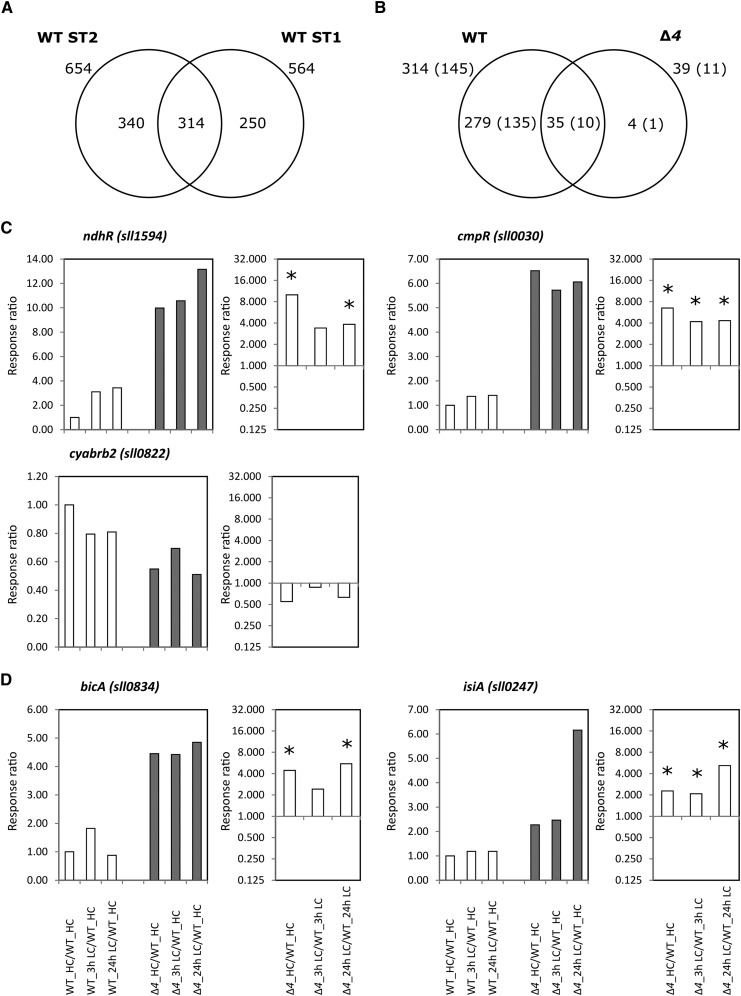

To identify the hallmark transcripts constituting the phenocopy of the mutant HC transcriptome, we focused on 314 Ci-responsive transcripts with an absolute fold change greater than 2 (P < 0.05) at 24-h LC conditions in the wild type (Fig. 7A). The Δ4 mutant HC transcriptome comprised transcripts of 30 protein-coding mRNAs, which increased only after the LC shift in the wild type (Table I). Four of these mRNAs were up-regulated. They encode the C-terminal processing protease ctpA (slr0008), the pilin polypeptide pilA1 (sll1694), and two proteins of unknown function (Table I). The levels of all other protein-coding RNAs constituting the phenocopy decreased. Among those are the genes coding for ATP synthase subunits (sll1321–sll1327) and the ATP synthase C chain of CF(0), atpH (ssl2615). Transcripts of genes related to nitrogen metabolism and photosynthesis were also part of the phenocopy, such as the nrtB-D (sll1451-sll1453) and amt1 (sll0108) nitrate/nitrite- and ammonium/methylammonium-uptake systems, the psbO (sll0427) manganese-stabilizing polypeptide of PSII, the cpcG2 (sll1471) phycobilisome rod-core linker polypeptide, and the allophycocyanin subunits apcA (slr2067) and apcB (slr1986; Table I). The down-regulation of phycobilisome-associated transcripts correlates with the changed expression of nblA1 (ssl0452) and nblA2 (ssl0453) coding for the phycobilisome degradation protein NblA in Δ4 under HC conditions (Supplemental Table S5). These genes showed no alteration in the ΔndhR transcriptome (Table I).

Figure 7.

Transcriptomic responses of the wild type (WT) and the ∆4 mutant to a shift from HC to LC supply. A, Venn diagram of common and specific transcriptome changes upon shifting from HC to LC supply comparing wild-type samples of this study (ST1) with those of an independent previous study (ST2; Klähn et al., 2015). B, Venn diagram of common and specific transcriptome changes upon a shift from HC to LC supply comparing the robustly changed transcripts of the wild type (compare with the intersection of A) with the significant transcript changes in the ∆4 mutant. Numbers of coding mRNAs among these transcripts are given in parentheses, and additional numbers include all transcripts. Note that the single mRNA that is specifically responsive to the shift from HC to LC supply in the ∆4 mutant codes for isiA (compare with D). C, Changes in transcripts for transcriptional regulators of Ci utilization in the ∆4 mutant compared with the wild type. D, Changes in transcripts of the only remaining Ci-uptake system of ∆4, bicA, and the single mRNA that is specifically changed in the ∆4 mutant upon a shift from HC to LC supply in the ∆4 mutant compared with the wild type. Response ratios in the left part of each pair are all calculated relative to the transcript levels of the wild type under HC conditions (WT_HC/WT_HC = 1). Response ratios in the right part of each pair represent the expression of the ∆4 mutant divided by the expression of the wild type under the same conditions and at the same time points. Significant changes (P < 0.05, Student’s t test) are indicated by asterisks.

Table I. Ci-responsive mRNAs constituting the partial preformed LC-shift phenocopy of the ∆4 mutant transcriptome under HC supply.

This table features the intersection of preformed transcriptional changes in the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions with robust Ci-responsive protein-coding transcripts of the wild type 24 h after shift from HC to LC supply and provides a comparison with respective changes in transcript levels in the ∆ndhR mutant under HC conditions (Klähn et al., 2015). The wild-type data set of this study (ST1) is compared with an independent previous study, ST2 (Klähn et al., 2015). Fold changes in expression levels were regarded as relevant for the intersection analysis and the selection of robust Ci-responsive transcripts if log2 of the change in expression level was −1 or less or +1 or more and at P ≤ 0.05. The same criteria were used to determine significance. Significant changes are displayed in boldface. All transcript data from these analyses were normalized to the paired average expression levels of wild-type HC conditions from the respective studies. All transcript data were averaged from two independently repeated biological shift experiments per genotype.

| Systematic Gene Name | Gene Name | Protein Name | Wild-Type 24-h LC Conditions/Wild-Type HC Conditions (ST1) | Wild-Type 24-h LC Conditions/Wild-Type HC Conditions (ST2) | Δ4 24-h HC Conditions/Wild-Type HC Conditions (ST1) | ∆ndhR 24-h HC Conditions/Wild-Type HC Conditions (ST2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induced genes | ||||||

| slr0008 | ctpA | C-terminal processing protease | 1.17 | 1.22 | 1.38 | −0.06 |

| sll1694 | pilA1 | Pilin polypeptide PilA1 | 1.51 | 1.97 | 1.01 | −0.38 |

| slr0442 | Unknown protein | 1.75 | 1.18 | 1.10 | −0.07 | |

| ssr2153 | Unknown protein | 1.22 | 1.60 | 3.06 | 0.26 | |

| Suppressed genes | ||||||

| sll1069 | fabF | 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase II | −1.35 | −1.29 | −1.02 | 0.04 |

| ssl2084 | acpP | Acyl carrier protein | −1.35 | −1.30 | −1.08 | 0.11 |

| slr2067 | apcA | Allophycocyanin α-subunit | −2.58 | −1.43 | −1.90 | 0.20 |

| slr1986 | apcB | Allophycocyanin β-subunit | −2.49 | −1.46 | −1.93 | 0.18 |

| sll0108 | amt1 | Ammonium/methylammonium permease | −2.78 | −2.17 | −1.64 | −0.15 |

| sll1317 | petA | Apocytochrome f, component of cytochrome b6/f complex | −1.59 | −1.01 | −1.38 | −0.07 |

| sll1322 | atpI | ATP synthase A chain of CF(0) | −2.19 | −1.30 | −1.50 | −0.08 |

| sll1326 | atpA | ATP synthase α chain | −2.35 | −1.62 | −1.47 | −0.01 |

| sll1324 | atpF | ATP synthase B chain (subunit I) of CF(0) | −2.27 | −1.73 | −1.36 | −0.06 |

| ssl2615 | atpH | ATP synthase C chain of CF(0) | −2.52 | −1.47 | −1.29 | 0.01 |

| sll1325 | atpD | ATP synthase δ chain of CF(1) | −2.30 | −1.65 | −1.43 | −0.06 |

| slr1330 | atpE | ATP synthase ε chain of CF(1) | −1.78 | −1.52 | −1.15 | −0.02 |

| sll1327 | atpC | ATP synthase γ chain | −2.43 | −1.97 | −1.41 | 0.01 |

| sll1323 | atpG | ATP synthase subunit b′ of CF(0) | −2.41 | −1.79 | −1.51 | −0.08 |

| sll1185 | hemF | Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, aerobic (oxygen dependent) | −1.82 | −1.37 | −1.69 | 0.28 |

| ssl0020 | petF | Ferredoxin I, essential for growth | −2.31 | −1.39 | −1.44 | 0.45 |

| sll1321 | atp1 | Hypothetical protein | −1.92 | −1.50 | −1.19 | −0.03 |

| sll1638 | Hypothetical protein | −1.56 | −1.16 | −1.02 | −0.02 | |

| sll1452 | nrtC | Nitrate/nitrite transport system ATP-binding protein | −2.31 | −1.70 | −1.08 | −0.09 |

| sll1453 | nrtD | Nitrate/nitrite transport system ATP-binding protein | −2.39 | −1.74 | −1.04 | −0.03 |

| sll1451 | nrtB | Nitrate/nitrite transport system permease protein | −2.51 | −1.86 | −1.02 | −0.07 |

| sll0427 | psbO | PSII manganese-stabilizing polypeptide | −2.16 | −1.09 | −1.32 | 0.10 |

| sll1471 | cpcG2 | Phycobilisome rod-core linker polypeptide | −3.30 | −1.54 | −2.90 | 0.41 |

| sll0222 | phoA | Putative purple acid phosphatase | −1.34 | −1.07 | −1.06 | −0.05 |

| sll1070 | tktA | Transketolase | −1.47 | −1.22 | −1.09 | −0.04 |

| ssl2814 | Unknown protein | −2.00 | −1.48 | −1.09 | −0.02 | |

Consistent with the observed preformation of wild-type responses to Ci shift in the Δ4 mutant, only 10 mRNAs remained significantly Ci responsive as in the wild type (Fig. 7B). They include amt1 (sll0108), nrtA (sll1450), cyp (slr1251), and urtA (slr0447), encoding proteins involved in nitrogen metabolism, which become globally down-regulated in LC-shifted cells. Several transcripts coding for proteins of unknown function, namely, sll1864 (a probable chloride channel protein), slr0373, slr0374, slr0376 (Singh and Sherman, 2002), slr1634, and ssr1038, also remained significantly Ci responsive in the Δ4 mutant (Supplemental Table S5). Most of the 135 Ci-responsive protein-coding transcripts of the wild type remained only slightly (statistically not significant) LC inducible in Δ4.

Although the Main Regulators of Carbon Metabolism, the Remaining HCO3−-Uptake System, and Carboxysomal Genes Are Deregulated, Carboxysome Structures Are Maintained in the Δ4 Mutant

As a further step toward understanding the Ci regulation in the Δ4 mutant, we examined gene expression for the CCM regulators. The transcript level of NdhR (sll1594) increased in the wild type upon shifting from HC to LC supply (Figge et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004; Klähn et al., 2015) but remained LC-shift unresponsive in the Δ4 mutant. This loss of Ci responsiveness in the mutant is linked to a high (approximately 10-fold higher than in the wild type under HC conditions) transcript level of ndhR (Fig. 7C). Additionally, transcription of CmpR (sll0030) is induced approximately 6-fold under HC conditions in the Δ4 mutant and is also not further increased under LC conditions. By contrast, the expression of CyAbrB2 (sll0822) was slightly decreased in the Δ4 mutant under both HC and LC conditions (Fig. 7C). Transcript levels of the remaining low-affinity HCO3−-uptake system, BicA (sll0834), increased significantly under all conditions in Δ4 (e.g. approximately 4-fold relative to the wild type under HC conditions; Fig. 7D).

Among the genes significantly down-regulated in the Δ4 mutant, we observed mRNAs coding for carboxysome proteins, namely ccmM (sll1031) and ccmN (sll1032). Additionally, rbcS (slr0012), rbcL (slr0009), and rbcX (slr0011), which code for both subunits of Rubisco and a Rubisco chaperonin, were down-regulated. However, electron microscopy revealed that the transcriptional down-regulation of carboxysome components in the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions was not associated with a loss of carboxysome structures (Fig. 1B). By contrast, the Δ4 mutant maintained significantly higher numbers of carboxysomes than the wild type with HC supply (Fig. 1C). After the LC shift, the carboxysome number increased in both strains, the wild type and the Δ4 mutant. Additionally, the Δ4 mutant also had more PHB bodies under HC conditions, which is characteristic for Synechocystis 6803 wild-type cells exposed to carbon excess under high-light conditions, leading to a reducing intracellular environment (Hauf et al., 2013).

Photooxidation and General Stress Transcripts Are Up-Regulated in the Δ4 Mutant

In addition to Ci-specific genes, a transcript subset indicated a general stress response of Δ4. For example, an enhanced expression of isiA (sll0247), coding for the chlorophyll-binding protein CP43′, was detected. IsiA was already increased in the Δ4 mutant under HC supply and further accumulated (approximately 5-fold compared with the wild type) upon the shift to LC conditions (Fig. 7D). This gene was initially described as an iron-stress protein, but Havaux et al. (2005) demonstrated that IsiA also responds to high light and protects Synechocystis 6803 cells against photooxidative stress. Transcriptional activation of isiA was accompanied by equally decreased expression of IsrR (Supplemental Table S2), an asRNA of isiA with a known inverse regulatory interaction (Dühring et al., 2006). Moreover, transcripts of the alternative sigma factors sigB (sll0306), sigD (sll2012), and sigH (sll0856) were highly induced in Δ4, irrespective of Ci supply. These transcripts responded to general stress (Los et al., 2010), high-light and redox stress (Imamura et al., 2003), oxidative stress (Li et al., 2004), or heat stress (Huckauf et al., 2000; Tuominen et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2006). Additionally, the expression of slr1738, coding for a peroxide responsive regulator (PerR)/ferric uptake regulation protein (FUR)-type transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress (Li et al., 2004; Garcin et al., 2012), was constitutively up-regulated more than 4-fold. Transcripts of the PerR/FUR-regulated gene sll1621, encoding an antioxidant type 2 peroxiredoxin (Kobayashi et al., 2004), were also accumulated in Δ4. Additional oxidative and high-light stress-responsive genes such as high light-inducible polypeptide C (hliC; small Cab-like protein [scp]B scpB, ssl1633), encoding a light-inducible protein associated with reaction center II (Knoppová et al., 2014), and ocp (slr1963), encoding the orange carotenoid protein for nonphotochemical quenching (Sedoud et al., 2014), were enhanced in Δ4. The up-regulation of these transcripts was consistent with the reported high-light sensitivity of the Δ4 mutant (Xu et al., 2008) and an overreduced cytoplasm, as indicated by the presence of PHB.

The constitutive and more than 5-fold up-regulation of the His kinase hik34 (slr1285) indicated a second stress component of Δ4. Hik34 regulates the expression of heat shock genes, but it is also stimulated as a general stress response by salt or hyperosmotic stress (Marin et al., 2003; Murata and Suzuki, 2006). We tested the Δ4 mutant for the specific expression of a set of 52 hyperosmotic stress-inducible genes in Synechocystis 6803 (Paithoonrangsarid et al., 2004). Twenty-six of these genes were induced in the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions. Except for sigD, none of these genes were significantly induced upon LC shift in the wild type (Table II). For example, the expression of the chaperonins GroEL1 (slr2076), GroEL2 (sll0416), and GroES (slr2075) decreased significantly to less than 0.5-fold in the wild type upon shifting from HC to LC conditions but were constitutively accumulated more than 2-fold in the Δ4 mutant.

Table II. Transcriptional changes of hyperosmotic stress-inducible genes in the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions.

This table features a list of hyperosmotic stress-inducible genes identified by Paithoonrangsarid et al. (2004) and the respective transcriptional changes in the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions. Fold changes in expression levels were regarded as significant (boldface) if log2 of the change in expression level was −1 or less or +1 or more and at P ≤ 0.05. Transcripts showing an inverse regulation in the wild type and the ∆4 mutant are underlined. All transcript data from these analyses were normalized to the paired average expression levels of the wild type under HC conditions. All transcript data were averaged from two independently repeated biological shift experiments per genotype. Groups are according to Paithoonrangsarid et al. (2004): group 1, genes in which induction by hyperosmotic stress was diminished or significantly reduced in Δhik33 cells; group 2, genes in which induction by hyperosmotic stress was diminished or significantly reduced in Δhik34 cells; group 3, genes in which induction by hyperosmotic stress was diminished or significantly reduced in Δhik16 and Δhik41 cells; group 4, genes in which induction by hyperosmotic stress was unaffected in Δhik33, Δhik34, Δhik16, or Δhik41 cells.

| Systematic Gene Name | Gene Name | Protein Name | Wild-Type 24-h LC Conditions/Wild-Type HC Conditions | ∆4 24-h HC Conditions/Wild-Type HC Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | ||||

| sll1483 | Periplasmic protein, similar to transforming growth factor-induced protein | −0.43 | 3.22 | |

| sll0330 | fabG | Sepiapterin reductase | 0.23 | 3.99 |

| slr1544 | Unknown protein | −1.13 | 2.90 | |

| ssl2542 | hliA, scpC | High-light-inducible polypeptide HliA, CAB/ELIP /HLIP superfamily | −0.64 | 0.39 |

| ssr2595 | hliB, scpD | High-light-inducible polypeptide HliB, CAB/ELIP /HLIP superfamily | −0.96 | 2.73 |

| ssr2016 | Hypothetical protein | −0.61 | 3.13 | |

| ssl1633 | hliC, scpB | High-light-inducible polypeptide HliC, CAB/ELIP /HLIP superfamily | 0.19 | 1.57 |

| ssl3446 | Hypothetical protein | 0.01 | 3.31 | |

| slr0381 | Lactoylglutathione lyase | 0.30 | 0.00 | |

| sll2012 | sigD | Group 2 RNA polymerase sigma factor SigD | 1.30 | 1.99 |

| sll1541 | Hypothetical protein | 0.02 | 0.43 | |

| Group 2 | ||||

| sll1514 | hspA | 16.6-kD small heat shock protein, molecular chaperone | −0.94 | 3.09 |

| sll0846 | Hypothetical protein | −0.35 | 3.18 | |

| slr1963 | ocp | Water-soluble carotenoid protein | −0.88 | 0.99 |

| slr1641 | clpB1 | ClpB protein | −0.07 | 1.88 |

| slr0959 | Hypothetical protein | −0.19 | 1.92 | |

| slr1516 | sodB | Superoxide dismutase | 0.01 | 1.29 |

| sll0430 | htpG | HtpG, heat shock protein90, molecular chaperone | −0.26 | 0.79 |

| sll1884 | Hypothetical protein | −0.07 | 0.93 | |

| slr1603 | Hypothetical protein | 0.54 | 1.75 | |

| slr1915 | Hypothetical protein | 0.05 | 2.42 | |

| ssl2971 | Hypothetical protein | −0.28 | 0.17 | |

| slr1285 | hik34 | Two-component sensor His kinase | −0.23 | 2.37 |

| slr1413 | Hypothetical protein | 0.11 | 1.04 | |

| sll0170 | dnaK2 | DnaK protein2, heat shock protein70, molecular chaperone | 0.16 | 2.21 |

| sll0005 | Hypothetical protein | 0.65 | 0.49 | |

| slr2076 | groEL1 | 60-kD chaperonin | −1.29 | 1.11 |

| slr0093 | dnaJ | DnaJ protein, heat shock protein40, molecular chaperone | 0.04 | 1.51 |

| slr2075 | groES | 10-kD chaperonin | −1.60 | 1.88 |

| sll0416 | groEL2 | 60-kD chaperonin2, GroEL2, molecular chaperone | −1.45 | 1.66 |

| Group 3 | ||||

| sll0939 | Hypothetical protein | −0.09 | −0.17 | |

| slr0967 | Hypothetical protein | −1.20 | 3.30 | |

| Group 4 | ||||

| sll1863 | Unknown protein | −1.13 | 0.76 | |

| sll1862 | Unknown protein | −0.24 | 1.08 | |

| sll0528 | Hypothetical protein | −0.13 | 3.06 | |

| slr1204 | htrA | Protease | −0.96 | 3.40 |

| slr0423 | rlpA | Hypothetical protein | 0.21 | 0.64 |

| sll1722 | Hypothetical protein | 0.08 | 1.75 | |

| sll0306 | sigB | RNA polymerase group 2 sigma factor | 0.62 | 2.99 |

| slr0581 | Unknown protein | 0.32 | 2.53 | |

| ssr1853 | Unknown protein | 0.35 | 0.62 | |

| slr1119 | Hypothetical protein | 0.31 | 0.55 | |

| slr0852 | Hypothetical protein | 0.22 | 2.42 | |

| ssr3188 | Hypothetical protein | 0.48 | 0.51 | |

| slr0112 | Unknown protein | 0.41 | 1.42 | |

| sll0294 | Hypothetical protein | 0.09 | 0.75 | |

| slr0895 | Transcriptional regulator | −0.56 | −0.48 | |

| ssl3177 | repA | Hypothetical protein | −0.37 | 1.48 |

| sll1085 | glpD | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| slr1051 | envM | Enoyl-[acyl carrier protein] reductase | −0.63 | −0.33 |

| sll0293 | Unknown protein | 0.46 | 1.21 | |

| sll0470 | Hypothetical protein | −0.17 | 1.42 | |

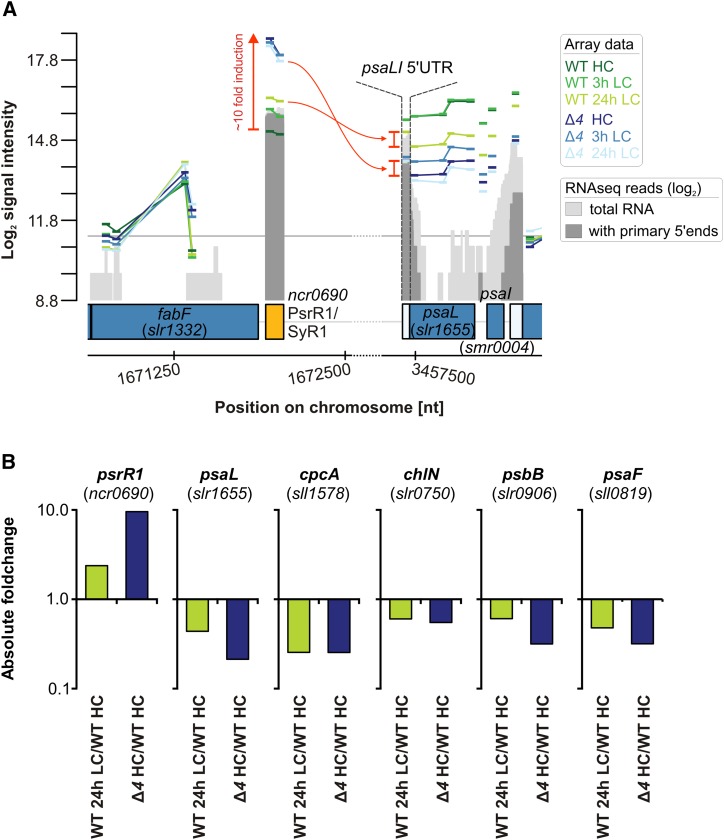

The Posttranscriptional PHOTOSYNTHESIS REGULATORY RNA1 Is Up-Regulated in the Δ4 Mutant

In Synechocystis 6803, the 131-nucleotide sRNA PHOTOSYNTHESIS REGULATORY RNA1 (PsrR1) functions as a posttranscriptional regulator leading to the down-regulation of psaLI, cpcA, chlN, psbB, and psaFJ mRNA levels and/or their translation (Georg et al., 2014). Previous analyses showed that PsrR1 in the wild type is strongly induced by shifts to high light but transiently also by shifts from HC to LC conditions (Mitschke et al., 2011; Kopf et al., 2014; Klähn et al., 2015). However, in the Δ4 mutant, PsrR1 abundance was constitutively increased (Fig. 8A), which is consistent with the down-regulation of genes related to the BINs photosystems and phycobilisomes (Fig. 5). In particular, the psaL mRNA, encoding the PSI reaction center protein subunit XI, becomes destabilized upon the binding of PsrR1 to a site overlapping the putative ribosome-binding site and start codon (Fig. 8A). This destabilization is caused by specific cleavage by the endonuclease RNase E, which separates the psaLI 5′ untranslated region (UTR) fragment that becomes selectively stabilized compared with the remaining truncated psaL mRNA, resulting in its characteristic higher abundance in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 8A). This finding indicated that the PsrR1-mediated down-regulation of psaL was part of the oxidative stress response in cells of the Δ4 mutant. Additionally, inverse relations with PsrR1 were also observed for the transcript levels of psaLI, cpcBA, chlN, psbB, and psaFJ (Fig. 8B), which are other known targets of PsrR1 or, in the case of psaI and psaF, constitute an operon with one of these targets (Georg et al., 2014).

Figure 8.

Posttranscriptional regulon of the sRNA PsrR1. A, Graphical overview of array signal intensities mapped along the genomic loci of PsrR1 and its main target psaL. The color-coded bars represent signals derived from individual microarray probes. The signal intensities on the y axis are given as log2 values. Protein-coding genes are represented by blue boxes, and sRNA-coding regions are represented by yellow boxes. All probes for the same RNA feature are connected by lines. The gray graphs represent RNA sequencing data given as log2 read numbers, which were extracted from Mitschke et al. (2011). nt, Nucleotides. B, Absolute changes in PsrR1 abundance and its verified target mRNAs, psaL, cpcA, chlN, psbB, and psaF, in the ∆4 mutant under HC conditions and in wild-type (WT) cells shifted to LC conditions for 24 h (fold changes relative to wild-type levels under HC conditions = 1).

DISCUSSION

We applied multiple comparative approaches for metabolic and transcriptional pattern recognition to gain insight into the physiological state of the Δ4 mutant. We expected the Δ4 mutant to exhibit a strong photorespiratory phenotype when shifted from HC to LC supply because of the absent Ci-uptake systems. Instead, we observed a complex physiological plasticity of Synechocystis 6803, which compensates intracellular Ci limitation and suppresses the Rubisco oxygenation reaction.

The Δ4 Phenocopy of the Wild-Type Response to Decreased CO2 Supply

The Δ4 mutant has an intracellular Ci limitation caused by the inactivation of four of the five Ci sequestration systems known in Synechocystis 6803 (Xu et al., 2008). It can grow in ambient air (Xu et al., 2008) because Ci uptake by the low-affinity HCO3− transporter BicA (sll0834) remains possible (Price et al., 2004, 2008). In fact, bicA expression was constitutively increased in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 7D; Supplemental Table S2), indicating a compensatory response that activated the residual HCO3− transport system. This observation, taken together with the deregulation of ndhR expression, is consistent with the hypothesis that bicA is controlled by NdhR combined with an additional regulatory mechanism (Klähn et al., 2015).

Our main finding was that the wild-type response to a shift from HC to LC supply is extensively phenocopied in the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions, both at the metabolomic and the transcriptomic systems levels (Figs. 4–6). The Δ4 mutant, therefore, can be regarded as a model of genetically engineered intracellular Ci limitation. The strong Δ4 phenocopy under HC conditions differs from the changes in the ΔndhR mutant (Figs. 5 and 6; Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2) and the ΔccmM mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012). The Δ4 mutant was expected to show enhanced photorespiration, because Ci limitation should favor the oxygenase reaction of Rubisco. Consistent with this expectation, the 2PG level was constitutively increased in the Δ4 mutant, but only moderately. However, the photorespiratory burst typically found in wild-type cells after a shift from HC to LC conditions was attenuated in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 2), in contrast to the intensified response in the carboxysomeless ΔccmM mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012). Apparently, the presence of carboxysomes in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 1B), despite transcriptional down-regulation of carboxysomal genes, suppresses the oxygenase function of Rubisco considerably. This finding indicates that the conversion of bicarbonate to CO2 within the carboxysome and the carboxysomal structure itself are the major factors that help to avoid photorespiration.

The photorespiratory burst of Synechocystis 6803 wild-type cells indicates that the oxygenase function of Rubisco is insufficiently suppressed upon a rapid LC shift (Eisenhut et al., 2008a; Huege et al., 2011; Klähn et al., 2015). During the shift, the CCM activation is subject to a lag phase because of reduced energy and carbon resources. The lack of a photorespiratory burst in the Δ4 mutant indicates a preformed carboxysome-dependent compensating mechanism that is active before shifting to LC conditions (Fig. 2). Intermediates of photorespiration were suggested to serve as metabolic sensors for Ci limitation (see refs. and discussion in Burnap et al., 2015). Given the changed levels of photorespiratory metabolites in the Δ4 mutant, such a compensating mechanism might be triggered by increased 2PG or Gly levels (Fig. 2). Alternatively, the Δ4 phenocopy and most of the wild-type LC-shift responses may be linked to the sensing of intracellular Ci pools, where a high intracellular bicarbonate pool represses the LC response (Woodger et al., 2005, 2007). However, we cannot rule out that other intracellular metabolites or changes in redox status might be sensed by Synechocystis 6803, because some Ci-responsive transcripts remained LC-shift responsive in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Table S5).

Deregulation of Ci Control in the Δ4 Mutant

Ci utilization under a changing Ci supply is tightly regulated in cyanobacteria. CCM genes, particularly those coding for the Ci-uptake systems, are maximally expressed under Ci-limiting conditions but are repressed when the cells are provided with elevated CO2 levels (Wang et al., 2004). Ci metabolism in Synechocystis 6803 is controlled by three currently known transcriptional regulators: NdhR, CmpR, and CyAbrB2. CyAbrB2 appears to mediate between carbon and nitrogen regulation, because it controls gene transcription involved in both parts of metabolism (Ishii and Hihara, 2008; Lieman-Hurwitz et al., 2009; Yamauchi et al., 2011; Kaniya et al., 2013). In this study, CyAbrB2 transcripts are slightly responsive to the reduced LC supply but not significantly altered in Δ4. In conclusion, it is rather unlikely that CyAbrB2 is involved in the control of genes for nitrogen assimilation and utilization associated with intracellular Ci limitation. CmpR and NdhR primarily regulate the high-affinity CO2/HCO3−-uptake systems. In contrast to the ΔccmM mutant, in which ndhR expression is slightly (2.5-fold) increased upon LC shift (Hackenberg et al., 2012), both transcriptional Ci regulators are maximally expressed under HC and LC supply in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 7C). CmpR promoter binding is dependent on 2PG and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (Nishimura et al., 2008). CmpR up-regulation in the Δ4 mutant indicates negative feedback regulation of intracellular Ci on cmpR expression. A regulatory role of stimulated photorespiratory 2PG metabolism was analyzed previously in photorespiratory mutants (Eisenhut et al., 2007), the ΔccmM mutant (Hackenberg et al., 2012), and a Synechocystis 6803 strain overexpressing 2PG phosphatase (Haimovich-Dayan et al., 2015). Photorespiratory metabolism may also contribute to the deregulation of cmpR transcription in the Δ4 mutant, because the 2PG pool is constitutively increased (Fig. 3). In contrast to CmpR, NdhR mainly represses genes encoding CO2/HCO3−-uptake systems under HC conditions (Figge et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004; Woodger et al., 2007). However, we recently showed that NdhR might also act as a regulator of genes under LC conditions (Klähn et al., 2015). Maximum expression of ndhR in the Δ4 mutant is likely caused by the loss of autorepression because of intracellular signals other than 2PG. The metabolites 2OG and NADP+ were shown to be NdhR corepressors in vitro and contribute to ndhF3 (sll1732) repression and ndhR autorepression in vitro (Daley et al., 2012). However, 2OG is not significantly changed in the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions and accumulates to a similar degree as in the wild type after LC shift. Therefore, it is unlikely that 2OG is the cause of ndhR deregulation in the Δ4 mutant. The deregulation of ndhR may instead be explained by a low level of NADP+ or a low NADP+-NADPH ratio. The assumption of a low NADP+ pool in the Δ4 mutant is consistent with the proposed full reduction of the electron transport chain (ETC) in the Δ4 mutant (Xu et al., 2008) caused by a lowered consumption of NADPH by the decreased Ci-uptake and low Ci-fixation activities. A low NADP+ pool in the Δ4 mutant is further supported by the presence of PHB bodies (Fig. 1B), a response that has been linked previously to an NADPH + H+ overflow (Hauf et al., 2013).

Moreover, the hypothesis of an overreduced intracellular state of the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions is also supported by the elevated transcription of genes involved in oxidative and high-light stress responses. It is known that, under high-light and Ci-limiting conditions, the consumption of NADPH + H+ is limited, causing photoinhibition (Burnap et al., 2015). The Δ4 mutant is photodamaged by overreduction of the ETC (Xu et al., 2008). Our study also indicates constitutive photooxidative stress. Accordingly, sigma factors (SigD, SigB, and SigH), the PerR-type transcriptional regulator (slr1738), the type 2 peroxiredoxin (sll1621), the photoprotective chlorophyll-binding proteins CP43′ (IsiA), HliC, and the orange carotenoid protein OCP are all stress regulated in the wild type and show changed expression in the Δ4 mutant. Because the Δ4 mutant does not phenocopy all photooxidative stress responses (Supplemental Table S6), we conclude that photooxidative stress is mostly compensated under the moderate continuous illumination regime (approximately 80 μmol photons m−2 s−1) employed in this study.

Intracellular Ci Limitation Modifies Nitrogen Utilization and Activates Resource Saving

Under HC conditions, a large fraction of carbon is used for carbohydrate biosynthesis in Synechocystis 6803 (Huege et al., 2011; Young et al., 2011; Schwarz et al., 2014). LC conditions reduce the carbon-nitrogen ratio and favor the partitioning of carbon into the glycolytic pathway. This response leads to the LC-characteristic accumulation of 2PGA and PEP in wild-type cells that is also part of the Δ4 phenocopy (Fig. 3). The Δ4 phenocopy also includes the preformed accumulation of several amino acids, such as Gly, Ser, Thr, Lys, and Tyr (Fig. 3), which was discussed previously as being part of the photorespiratory burst and the changed carbon partitioning under Ci limitation (Schwarz et al., 2014; Klähn et al., 2015). By contrast, Gln and Glu, the entry points of nitrogen assimilation into central metabolism, are already reduced at 3 h after the LC shift in the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 3). This observation indicates a stronger down-regulation of nitrogen assimilation in the Δ4 mutant than in the wild type after shifting to LC conditions. This assumption is supported by the globally reduced expression of genes related to Gln biosynthesis and nitrogen assimilation (Fig. 5) and the low expression of all nitrogen-uptake systems in Δ4 (Supplemental Table S5). The strong pool size increases of Ser and Tyr are inconsistent with the decreased expression of aromatic amino acid and Ser transcripts. We argue that the respective amino acid pool size increases are not caused by activated de novo biosynthesis but rather by the reduced use of amino acids. Reduced consumption of amino acids is consistent with saving carbon and nitrogen resources and tuning growth to intracellular Ci limitation. Accordingly, the decrease in transcript abundance related to translation (Fig. 5), as well as to de novo fatty acid biosynthesis (e.g. acpP [ssl2084] and fabF [sll1069]), is consistent with the reduced growth rate of the Δ4 mutant that was reported previously (Xu et al., 2008). Thus, the Δ4 mutant limits the expression of bulk proteins, such as ribosomal proteins, Rubisco, the main constituents of phycobilisomes and photosynthesis, and carboxysomal proteins (Supplemental Table S5). The maintenance of significantly higher numbers of carboxysomes by the Δ4 mutant (Fig. 1) despite down-regulated transcript levels may indicate reduced degradation of carboxysome proteins. Posttranscriptional rather than transcriptional regulation of increased carboxysome numbers in LC-treated cells of Synechocystis 6803 has been suggested previously (Eisenhut et al., 2007).

Posttranscriptional Regulators Involved in the Response to Low Ci

Our data suggest multiple layers of Ci regulation, including the inverse regulation of mRNAs and asRNAs (Georg and Hess, 2011). Examples include down-regulation of the asRNA IsrR and up-regulation of its target isiA, a protectant against photooxidative stress, in the Δ4 mutant. This module constitutes a known regulatory interaction, which is executed by codegradation (Dühring et al., 2006). A recently identified asRNA (sll1730-as1; Klähn et al., 2015) was increased in the ∆4 mutant (Supplemental Table S5). This asRNA has not yet been functionally studied in detail, but it overlaps with and shows a similar regulatory pattern to the NdhR-controlled sll1732 (ndhF3) mRNA.

Another category of posttranscriptional regulators is the class of trans-encoded sRNAs, which in bacteria frequently control multiple genes (Wright et al., 2013). We previously observed several low-Ci-stimulated sRNAs in Synechocystis 6803. Noncoding RNA, Ncr0210, which was suggested as an NdhR-regulated sRNA (Klähn et al., 2015), was up-regulated in the ∆4 mutant. This observation is consistent with the deregulation of the autoregulatory ndhR gene as well as other NdhR target genes such as bicA, slr1592, or slr2006-2013 (Supplemental Table S2). The regulatory sRNA PsrR1 is superinduced in the Δ4 mutant and becomes induced under LC conditions also in the wild type. PsrR1 is a posttranscriptional regulator of several photosynthesis-related genes (Georg et al., 2014). The data from this study suggest that at least seven different genes are affected by PsrR1 under Ci limitation in the wild type and under intracellular Ci limitation in the Δ4 mutant. It should be noted, however, that PsrR1 is not the only regulator of these genes (Seino et al., 2009). Conversely, we cannot rule out that the expression of additional genes is controlled by PsrR1 under these conditions, as several additional potential PsrR1 targets were computationally predicted previously (Georg et al., 2014). Most of these potential targets are photosynthesis-related genes. The importance of PsrR1 for the posttranscriptional regulation of photosynthesis-related genes raises the question of which regulatory factors are involved in the activation of PsrR1 transcription. In addition to induction by low Ci, the expression of PsrR1 is activated by shifts to higher light intensities (Georg et al., 2014). Based on the results presented here, a regulatory protein linked to the redox status of the cell or to the photosynthetic electron transfer chain could be a plausible candidate PsrR1 regulator.

CONCLUSION

Our integrated analysis of engineered intracellular Ci limitation in the Δ4 mutant demonstrated that Synechocystis 6803 compensates for intracellular Ci limitation under HC conditions by activating a wide range of wild-type responses to shifts from HC to LC conditions. The compensation encompasses central cellular functions, such as photosynthesis and translation, and activates the only remaining Ci-uptake system, enabling slow growth under HC and LC supply. The detailed analysis of the ∆4 phenocopy explains the unexpected finding that photorespiration was only moderately affected and that the photorespiratory burst upon shifting from HC to LC conditions was not enhanced. These observations are likely caused by the maintenance of carboxysomes in ∆4 under HC conditions and support the conclusion that protection of the Rubisco reaction by carboxysomes and the conversion of HCO3− to CO2 within carboxysomes are the major factors of the CCM to avoid photorespiration under intracellular Ci limitation. The deregulation of Ci control in ∆4 acts at different regulatory levels. Metabolic signals, such as 2PG, Gly, or NADP+, the ETC redox status, transcriptional Ci regulators, namely ndhR and cmpR, and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are obviously involved. The intracellular Ci availability of Synechocystis 6803 cells affects posttranscriptional regulation through multiple inversely regulated mRNA and asRNA pairs and trans-encoded sRNAs. Thus, our data suggest that many additional layers of Ci regulation may await discovery.

Looking beyond fundamental insights into carbon regulation, our data may also serve as a reference for global responses to intracellular Ci limitation among cyanobacteria. These organisms are increasingly used for biotechnological approaches, which channel off carbon from central metabolism with the aim of direct biofuel production from assimilated Ci. The engineered pathways tap into central metabolism by accessing pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, or methylglyoxal pools and irreversibly withdraw carbon (Savakis and Hellingwerf, 2015). If such engineered pathways become more efficient, these biotechnological modifications are likely to generate intracellular Ci limitation. Such a situation occurs if ethanol production by cyanobacteria (Deng and Coleman, 1999) exceeds the current limits of 0.1 to 0.5 g L−1 d−1 (Dexter et al., 2015). Our analysis of system responses to intracellular Ci limitation in the Δ4 mutant indicates the wide range of responses of cyanobacteria to fluctuating Ci availability and may help overcome the current limits of redirected Ci utilization for biofuel production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Growth Conditions

The Glc-tolerant strain Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (wild type) was a gift from N. Murata (National Institute for Basic Biology) and was used as the wild type reference strain in this study. The Δ4 mutant (∆ndhD3/ndhD4/cmpA/sbtA) of Synechocystis 6803 (Shibata et al., 2002) was obtained from T. Ogawa. Mutant cells were maintained in the presence of spectinomycin, kanamycin, hygromycin, and chloramphenicol, as reported previously (Shibata et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2008) in BG11 medium (Rippka et al., 1979) that was buffered by 20 mm TES-KOH at pH 8. The wild type was cultivated without antibiotics under otherwise identical conditions. The general growth conditions were a constant temperature of 29°C with continuous light set to approximately 80 μmol photons m−2 s−1 and otherwise as detailed by Schwarz et al. (2011).

For CO2-shift experiments, cells were precultivated at least 24 h in advance by bubbling CO2-enriched air adjusted to 5% (v/v) CO2 through the culture (defined as HC conditions). Before the shift experiments, cells in the exponential growth phase were harvested by centrifugation (5 min at 3,000g, 20°C), washed, resuspended in fresh BG11 medium with a pH of 7, and adjusted to optical density at 750 nm (OD750) = 0.8. After approximately 1 h of continued cultivation under HC conditions, the cells were shifted to bubbling with ambient air (0.035% [v/v] CO2; defined as LC conditions). Samples were taken under HC conditions immediately before the shift and 3 or 24 h after the shift to LC conditions using fast filtration in light and immediate shock freezing the collected cells from the filter in liquid nitrogen (Huege et al., 2011; Schwarz et al., 2011).

Microarray Analysis and Data Processing

RNA for microarray analysis was prepared from 15 mL of exponentially growing cultures at OD750 approximately 0.8 that were harvested by 10 min of centrifugation at 6,000 rpm and 4°C. Cells were lysed in 1 mL of PGTX, with the following composition: 39.6% (w/v) phenol, 7% (v/v) glycerol, 7 mm 8-hydroxyquinoline, 20 mm EDTA, 97.5 mm sodium acetate, 0.8 m guanidine thiocyanate, and 0.48 m guanidine hydrochloride (Pinto et al., 2009). RNA extraction was performed as described by Hein et al. (2013). RNA of two independent biological replicates for each sampling point (i.e. of the wild type or the Δ4 mutant under HC conditions, 3 h of LC conditions, or 24 h of LC conditions) was hybridized to a custom-made microarray (Mitschke et al., 2011). Before labeling, 10 µg of total RNA were treated with Turbo DNase (Invitrogen-Life Technologies) and precipitated with ethanol/sodium acetate. Then, 3 µg of RNA was labeled, and 1.65 µg of the labeled RNA was hybridized exactly as described by Georg et al. (2009).

Data were processed and statistically evaluated using open-access R software for statistical computing (http://www.r-project.org/) as described previously (Georg et al., 2009). In Supplemental Data Set S1, the microarray data are presented as a graphical overview of log2 signal intensities for individual probes that are mapped along the Synechocystis 6803 chromosome. Transcript features are separated into mRNAs, asRNAs, ncRNAs, 5′ UTRs, and transcripts derived from internal transcriptional start sites. The annotation of ncRNAs can be ambiguous and overlap with the UTRs. The RNA annotation of this study is based on Mitschke et al. (2011).

The full data set of the wild type and the Δ4 mutant from this study is accessible from the Gene Expression Omnibus database with the accession number GSE68250. The expression data for related mutants were extracted from previous studies for comparative pattern analysis. Transcript data for the ΔccmM mutant and the ΔndhR mutant were taken from the tables and the supplements of Hackenberg et al. (2012) and Klähn et al. (2015). The full data sets of the ΔccmM and ΔndhR mutants are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus database via accession numbers GSE31672 and GSE63352, respectively.

Functional Enrichment Analysis of Transcriptome Profiles

For the functional enrichment analysis, we used the hierarchical functional categories provided by the CyanoBase genome annotation of Synechocystis 6803 (http://genome.microbedb.jp/cyanobase/Synechocystis; downloaded September 23, 2014; Kaneko et al., 1996). For functional categorization, we distinguished between mRNA probes that represent protein-coding sequences and asRNA probes that were reverse complements of coding sequences. Probes corresponding to 5′ UTRs, potential internal transcriptional start sites, and noncharacterized intergenic regions that may contain novel ncRNAs were not assessed. Both the mRNAs and asRNAs were classified according to the full set of functional categories from CyanoBase to create 69 functional categories (i.e. BINs) of mRNAs and, because of lower coverage, 66 asRNA BINs. The resulting Synechocystis 6803 gene ontology was formatted as a hitherto not available probe-mapping file (Supplemental Table S4) that enabled access to the tools of the MapMan (Thimm et al., 2004) and PageMan (Usadel et al., 2006) software suite. Wilcoxon rank-sum testing with Benjamini-Hochberg correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) for multiple testing was applied to statistically evaluate and select functional categories with preferentially increased or decreased transcripts relative to the wild type under HC conditions. The PageMan software returns z-scores of P values from the Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (Usadel et al., 2006). Positive z-scores indicate significant up-regulation in a given BIN, and negative z-scores indicate preferential down-regulation. High absolute z-score values indicate high significance. The term infinity indicates highly significant positive z-scores that were beyond exact calculation of the underlying PageMan algorithm.

Metabolome Analysis

A metabolite fraction enriched for primary metabolites was profiled, and relative pool size changes were determined by GC-EI-TOF-MS as described previously (Klähn et al., 2015). In summary, metabolome profiling experiments were performed using triplicate independent cell cultures. Each single biological replicate was analyzed by at least two technical replicate samples. The metabolome analysis of the wild type and the mutant samples of this study was paired with the metabolome analysis of Klähn et al. (2015; i.e. the experiments were performed, and the biological samples were generated, in parallel). Furthermore, the GC-EI-TOF-MS profiling analysis of this and the previous study (Klähn et al., 2015) was simultaneous, so that the wild-type data could be shared between these studies.

Metabolite profiles were analyzed by nontargeted and multitargeted approaches. For the nontargeted approach, all detectable mass features were analyzed. The multitargeted approach used only annotated metabolite data. The relative amounts of mass features and annotated metabolites were calculated by normalization of the recorded intensities to an internal standard (i.e. [d-13C6]sorbitol; CAS 121067-66-1; Sigma-Aldrich) and to the amount of cell material in each sample determined by OD750 (Huege et al., 2011). Metabolites were annotated manually using the reference data from the Golm Metabolome Database (Hummel et al., 2010). Criteria for positive annotation were the presence of at least three specific mass fragments per compound, a retention index deviation less than 1% (Strehmel et al., 2008), and a mass spectral match. Relative pool size changes in metabolites or mass features are expressed by response ratios (i.e. x-fold factors of normalized amounts), comparing all mutant and LC-shifted cells with a single reference condition, namely the mean of wild-type samples under HC conditions, if not stated otherwise. Metabolite response categories were according to Klähn et al. (2015).

Statistical analyses were performed using log10-transformed response ratios and averaged technical replicates. The two-way ANOVA and the Mack-Skillings test (Supplemental Table S1) were performed using the multiexperiment viewer software MeV, version 4.9, available at http://www.tm4.org/mev.html (Saeed et al., 2003). Heteroscedastic Student’s t tests were calculated using the Microsoft Excel 2010 program. PCA and ICA and were performed after log10 transformation using the MetaGeneAlyse Web-based tool (http://metagenealyse.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/). ICA was based on the first five components of a preceding PCA.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Fixation and processing for transmission electron microscopy were performed as described previously (Hackenberg et al., 2012) with the following modifications. After embedding in low-melting-point agarose, specimens were postfixed with 1% (v/v) osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded series of acetone, and embedded in Epon 812 epoxy resin (Serva). Ultrathin sections were analyzed with Zeiss EM 902 and Zeiss Libra 120 electron microscopes (Carl Zeiss) that were equipped with a 1kx2k FT-slow-scan CCD camera (Proscan) and a 2kx2k slow-scan CCD camera (TRS Tröndle Restlichtverstärkersysteme), respectively. Carboxysome analysis included 25 to 49 representative cells of the wild type or the Δ4 mutant sampled from HC or LC conditions.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Global responses of metabolism to a shift from HC to LC conditions in the wild type compared with the ∆4 mutant and the ∆ndhR mutant.

Supplemental Figure S2. Correlation analysis between metabolic changes in the ∆4 mutant and the ∆ndhR mutant under HC compared with the wild type 24 h-LC shift response.

Supplemental Table S1. Complete data set of the metabolome analysis of the ∆4 mutant compared with the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 wild type upon shift from a high to a low inorganic carbon supply.

Supplemental Table S2. Complete data set of the transcriptome analysis of the ∆4 mutant compared with the Synechocystis 6803 wild type upon shift from a high to a low inorganic carbon supply.

Supplemental Table S3. Probe mapping file of the transcriptome profiling platform (Mitschke et al., 2011) to the functional categories provided by the cyanobase genome annotation of Synechocystis 6803.

Supplemental Table S4. Complete enrichment analysis of Ci-responsive functional categories in the ∆4 mutant compared with the Synechocystis 6803 wild type upon shift from a high to a low inorganic carbon supply.

Supplemental Table S5. Subsets of the transcriptome analyses which report significantly changed transcripts in various pairwise comparisons.

Supplemental Table S6. Transcriptional changes of oxidative stress-inducible genes in the ∆4 mutant under HC.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Graphical overview of the microarray data set comprising log2 signal intensities mapped along the Synechocystis 6803 chromosome (see Fig. 8A).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Teruo Ogawa (Bioscience Center, Nagoya University) for the Δ4 mutant of Synechocystis 6803; Dr. Norio Murata (National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki) for the Glc-tolerant strain Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803; Dr. Jan Hüge, whose enthusiasm and fundamental work enabled these studies; Dr. Lothar Willmitzer (Max-Planck-Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology) and the Max-Planck Society for longstanding support; Klaudia Michl (Plant Physiology, University of Rostock) and Gudrun Krüger (Genetics and Experimental Bioinformatics, University of Freiburg) for skillful technical assistance; and Ute Schulz and Gerhard Fulda (University Medicine Rostock) for technical assistance with electron microscopy.

Glossary

- Ci

inorganic carbon

- 3PGA

3-phosphoglycerate

- 2PG

2-phosphoglycolate

- CCM

CO2-concentrating mechanism

- HC

high-CO2

- LC

low-CO2

- asRNA

antisense RNA

- sRNA

small RNA

- 2PGA

glycerate-2-phosphate

- PEP

phosphoenolpyruvate

- 2OG

2-oxoglutarate

- PCA

principal component analysis

- ICA

independent component analysis

- PHB

polyhydroxybutyrate

- UTR

untranslated region

- ETC

electron transport chain

- ncRNA

noncoding RNA

- OD750

optical density at 750 nm

- GC-EI-TOF-MS

gas chromatography-electron ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant nos. HA2002/8–3 and KO2329/3–3 and Research Unit FOR 1186, Photorespiration: Origin and Metabolic Integration in Interacting Compartments) and by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (CYANOSYS grant no. 0316183).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Battchikova N, Eisenhut M, Aro EM (2011) Cyanobacterial NDH-1 complexes: novel insights and remaining puzzles. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807: 935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H, Hagemann M, Fernie AR (2010) Photorespiration: players, partners and origin. Trends Plant Sci 15: 330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57: 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA. (1990) Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels over phanerozoic time. Science 249: 1382–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnap RL, Hagemann M, Kaplan A (2015) Regulation of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. Life (Basel) 5: 348–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SME, Kappell AD, Carrick MJ, Burnap RL (2012) Regulation of the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating mechanism involves internal sensing of NADP+ and α-ketoglutarate levels by transcription factor CcmR. PLoS One 7: e41286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng MD, Coleman JR (1999) Ethanol synthesis by genetic engineering in cyanobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 523–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deusch O, Landan G, Roettger M, Gruenheit N, Kowallik KV, Allen JF, Martin W, Dagan T (2008) Genes of cyanobacterial origin in plant nuclear genomes point to a heterocyst-forming plastid ancestor. Mol Biol Evol 25: 748–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter J, Armshaw P, Sheahan C, Pembroke JT (2015) The state of autotrophic ethanol production in cyanobacteria. J Appl Mirobiol 119: 11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]