Abstract

Background

Bipolar affective disorder has a high rate of comorbidity with a multitude of psychiatric disorders and medical conditions. Among all the potential comorbidities, co-existing anxiety disorders stand out due to their high prevalence.

Aims

To determine the lifetime prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in bipolar affective disorder under the care of psychiatric services through systematic review and meta-analysis.

Method

Random effects meta-analyses were used to calculate the lifetime prevalence of comorbid generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, agoraphobia, obsessive compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in bipolar affective disorder.

Results

52 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The rate of lifetime comorbidity was as follows: panic disorder 16.8% (95% CI 13.7–20.1), generalised anxiety disorder 14.4% (95% CI 10.8–18.3), social anxiety disorder13.3% (95% CI 10.1–16.9), post-traumatic stress disorder 10.8% (95% CI 7.3–14.9), specific phobia 10.8% (95% CI 8.2–13.7), obsessive compulsive disorder 10.7% (95% CI 8.7–13.0) and agoraphobia 7.8% (95% CI 5.2–11.0). The lifetime prevalence of any anxiety disorders in bipolar disorder was 42.7%.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a high rate of lifetime concurrent anxiety disorders in bipolar disorder. The diagnostic issues at the interface are particularly difficult because of the substantial symptom overlap. The treatment of co-existing conditions has clinically remained challenging.

Abbreviations: GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; ICD, International Classification of Diseases

Keywords: Comorbidity, Bipolar affective disorder, Anxiety disorders, Inpatient, Outpatient clinic

Highlights

-

•

There is a high comorbidity between bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders.

-

•

Panic disorder is the most common comorbid anxiety disorder in bipolar disorder.

-

•

The presence of comorbid anxiety disorders may adversely affect the overall outcome in bipolar disorder.

Bipolar affective disorders are among the most disabling psychiatric conditions with relatively high rates of morbidity and mortality. A substantial proportion of patients with these conditions also suffer from other co-existing psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety disorders, which may adversely affect their overall outcome and prognosis. Previous studies have indicated the presence of a high level of heterogeneity regarding the prevalence of comorbidity. This meta-analysis is an attempt to estimate the prevalence of comorbidity between these two conditions by summarising the findings of primary studies. We hope that this review will populate and generate research hypotheses, as well as assist clinicians alike.

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorders with the prevalence rate of 4% are among the most common psychiatric disorders (Ketter, 2010). It is considered to be the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide due to its significant economic, social, familial and individual burdens (Woods, 2000). Lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder type I or type II (which includes at least one hypo/manic episode during a lifetime) has been estimated at 2% (Oldani et al., 2005). The relationship between bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders can create a more difficult course of treatment if comorbid (McIntyre et al., 2006). Studies suggest that the rate of anxiety disorders in individuals with bipolar disorder is in fact greater than those of the general population (Keller, 2006).

Bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), specific phobia, agoraphobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are psychiatric illnesses that individually cause significant mortality and morbidity, as reflected in suicide rates (Allgulander and Lavori, 1991, Schneier et al., 1992, Osby et al., 2001), substance abuse rates (Chengappa et al., 2000, Grant et al., 2004), total medical burden (Klerman et al., 1991, Tolin et al., 2008, Lauterback et al., 2005), economic costs (Souètre et al., 1994, Wyatt and Henter, 1995) and quality of life (Wittchen et al., 1992, Mendlowicz and Stein, 2000).

Clinical and epidemiological studies have reported lifetime prevalence rates for comorbid anxiety disorders in bipolar disorder of 50% (Cassano et al., 1999, Pini et al., 1997, McElroy et al., 2001). The Epidemiological Catchment Area study found the lifetime prevalence for panic disorder in bipolar illness to be 20.8%, more than twice the rate of 10% reported in patients with major depressive disorder (Pini et al., 1997, Chen and Dilsaver, 1995a, Chen and Dilsaver, 1995b, Perugi et al., 2001). The frequency of GAD at 30% in bipolar disorder is reported by two studies (Pini et al., 1997, Young et al., 1993). The prevalence of comorbid social anxiety disorder ranges between 7.8% (Szadoczky et al., 1998) and 47.2% (Kessler et al., 1997) and the prevalence rate of OCD has been found to be between 3.2% and 35% (Pini et al., 1997, Perugi et al., 2001, Szadoczky et al., 1998, Krüger et al., 1995). Although the association between PTSD and bipolar disorder has been less extensively studied, the rate of comorbidity between these two conditions may exceed by 40% (Musser et al., 1998).

Previous studies have suggested that multiple anxiety disorder comorbidities occur in a significant minority of patients with bipolar disorder. For example, Young et al. (1993) found multiple anxiety disorders in 32% of bipolar disorder outpatients. Cassano et al. (1999) studied 77 inpatients presenting with severe mood disorders with psychotic features, including bipolar I, and found the presence of one anxiety disorder in 34% of cases, while 14% of patients had two or three. Similarly, Henry et al. (2003) studied 318 inpatients most of whom had bipolar I disorder and found the rate of one or more lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders to be 24% and 11%, respectively. The extent to which anxiety and the presence of single or multiple anxiety disorders impact on course and outcome in bipolar disorder has been studied only in a limited way (Ghoreishizadeh et al., 2009, Deckersbach et al., 2014).

Compared to those with uncomplicated bipolar disorder, this co-occurrence with anxiety disorders is associated with increased suicide attempts and ideation (Young et al., 1993, Simon et al., 2003, Lee and Dunner, 2008, Frank et al., 2002, Angst et al., 2005), substance abuse (Young et al., 1993, Simon et al., 2003, Lee and Dunner, 2008, Angst et al., 2005, Toniolo et al., 2009), increased severity of mood episodes (Frank et al., 2002, Angst et al., 2005, Toniolo et al., 2009, Gaudiano and Miller, 2005), and more mood episodes. Young et al. (1993) and Feske et al. (2000) also found a decrease in lithium responsiveness in the presence of anxiety disorders. Other studies showed this combination has led to a longer recovery time (Feske et al., 2000, Otto et al., 2006) and an earlier age at the onset of bipolar illness (Simon et al., 2003, Lee and Dunner, 2008, Pini et al., 2006).

The co-occurrence of an anxiety disorder leads to a particularly difficult challenge in the treatment of bipolar illness since antidepressant medication, the mainstay of pharmacologic treatments for anxiety, may adversely alter the course of bipolar disorder. Furthermore, the common co-occurrence of alcohol and substance use disorders with bipolar disorder, limits the utility of benzodiazepines. Identification of anxiety disorders in bipolar patients is important. The treatment plan needs to balance the potential benefits to harm of antidepressant administration (El-Mallakh and Hollifield, 2008) and benzodiazepines (Brunette et al., 2003) administration.

In view of the presence of a high heterogeneity about the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with bipolar disorder, we aimed to quantitatively summarise the lifetime prevalence of robustly defined anxiety disorders in co-occurrence bipolar disorder (mainly type I) in psychiatric inpatient and outpatient population.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

BN and AJM designed the review protocol and extraction form in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). A systematic search of PsycINFO, Medline, and CINAHL abstract databases was done by BN, from 1992 to 2013.

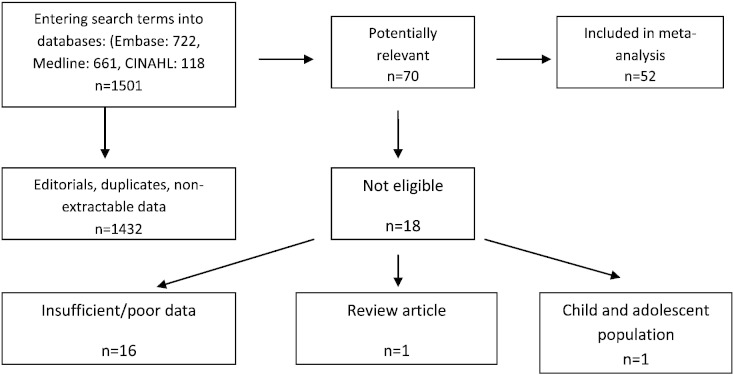

We included studies with data for the lifetime comorbidity between bipolar affective disorder and anxiety disorders among population of patients with bipolar affective disorder under the care of psychiatric services, and we excluded the data from any community-based samples. When it was possible, we only included the data from bipolar I studies in order to minimise selection bias, as previous studies suggested different prevalence of comorbidity between bipolar I and II with anxiety disorders. Otherwise, we used the data of those studies, which had clearly reported no significant differences in their findings regarding the type of bipolar disorder. Hence, the term of ‘bipolar affective disorder’ in this paper mainly indicates bipolar disorder type I. The included studies were stratified into those comorbidities with all anxiety disorders and those with a specific subtype of anxiety disorder, including GAD, panic disorder, OCD, PTSD, SAD, specific phobia and agoraphobia. We excluded the data from any diagnoses of cyclothymia. In order to minimise selection bias, we also excluded the community-based studies, as well as the data from child and adolescent studies. We took extra care to exclude duplicate publications (i.e. two or more studies investigating the same sample) in order to avoid multiple or duplication bias (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trail flow of selecting studies.

3. Validity Assessment

3.1. Data Abstraction and Classification

We extracted the primary data independently, which was reviewed systematically. Based on the Cochrane Bias Method Group recommendations, a four-point quality rating and a five-point bias risk were applied to each study. The quality rating score was used to assess the study sample size, design, attrition, criterion method and method of dealing with possible confounders using the following scale: 1 = low quality; 2 = low-to-medium quality; 3 = medium-to-high quality; and 4 = high quality. The bias rating score was similarly used to assess possible bias in assessments of age, clinical setting with the following score: 1 = low bias risk; 2 = low-to-medium bias risk; 3 = medium-to-high bias risk; and 4 = high bias risk. Finally the sampling method was assessed for each study, because this could affect the interpretation of the comorbidity data. Any area of disagreement was resolved by BN and AJM.

3.2. Outcome Measures

We defined the main outcomes of interests as the lifetime prevalence of comorbidity between bipolar affective disorder type I and anxiety disorders, as well as any specific type of anxiety disorders, defined by the DSM-III, DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, ICD-9 and ICD-10 criteria.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Overall effects estimates were calculated using the DerSimonian–Laird meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was invariably moderate to high. Therefore, a random effects meta-analysis was chosen over a fixed effects model with StatsDirect (version 2.7.7). For comparative and sub-analyses, we needed a minimum of three independent studies to justify analysis according to convention. The impact of heterogeneity on the pooled estimates of the individual outcomes of the meta-analysis was assessed using Cochran's Q, a χ2 statistic. This was used to test whether the differences between studies was due to chance. A P value close to 1 suggests a high probability that the observed heterogeneity was due to sampling error. We also used the I² test to assess heterogeneity (thresholds were ≥ 80% = moderate and ≥ 90% = high).

We examined the presence of publication bias with the Begg funnel plot (Dear and Begg, 1992). In addition, we used the following three tests to see if asymmetry in the funnel plot is caused by publication bias. 1) Begg–Mazumdar test (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994), which tests the inter-dependence of variance and effect size with a rank correlation method. B) The Egger test (Egger et al., 1997), which tests for asymmetry of the funnel plot. C) The Harbord test (Harbord et al., 2006), which is similar to the Egger test but uses a modified linear regression method to reduce the false-positive rates. We also used Spearman correlation with adjusted r² to assess the association between linear variables.

4. Results

We identified 1501 relevant articles, with 70 including lifetime prevalence of bipolar patients with anxiety disorders' comorbidity who were assessed using an interview-based diagnostic method (Fig. 1). A total of 18 out of 70 studies were excluded because they either contained insufficient data for analysis (16 studies) or were a review article. One study was excluded as it was conducted on a child and adolescent population with the mean age of 12.7 years old (Sala et al., 2010). We identified 52 relevant articles including 13,656 individuals with established diagnosis of bipolar disorder with lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders, including GAD, PTSD, SAD, specific phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder and OCD (Table 2). The majority of the studies (32 out of 52) were carried out in outpatient clinic populations and 13 studies were conducted in inpatient settings. Seven studies included both inpatient and outpatient individuals. 36 studies used consecutive samples, whereas a further 16 studies used convenience sampling method (Table 2). Data extraction is shown in Fig. 1 in accordance with the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses Guidelines (Moher et al., 1999).

Table 2.

Overview of prevalence studies of anxiety disorders in patients with bipolar disorder.

| Authors | Sampling methoda Settingb |

Qualityc | Bias riskd | No with bipolar disorder | Mean age (years) | Type of anxiety disorders | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angst et al. (2013) | 1 IN/OP | 4 | 1 | 685 | 44.1 | GAD, SAD, AGR, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Hernandez et al. (2013) | 1 OP | 4 | 1 | 3158 | 39.9 | PTSD | USA |

| Alvarez et al. (2012) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 40 | 39.4 | PTSD | Spain |

| Bellani et al. (2012) | 1 OP | 4 | 0 | 205 | 36.6 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, PTSD Agoraphobia, OCD AD | USA |

| Castro e Couto et al. (2012) | 1 OP | 4 | 0 | 95 | 40.9 | GAD, PD | Brazil |

| Chang et al. (2012) | 1 OP | 4 | 1 | 120 | 31.4 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, PD, SP, OCD, AD | Taiwan |

| Dell'Osso et al. (2011) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 508 | 44.4 | GAD, PD, OCD | Italy |

| Saunders et al. (2012) | 0 IN/OP | 4 | 1 | 736 | 42.6 | SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Tsai et al. (2012) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 306 | 37.0 | GAD, SAD, SP, AGR, PD, AD | Taiwan |

| Fracalanza et al. (2011) | 1 OP | 4 | 0 | 62 | 40.0 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, PD, OCD | Canada |

| Okan Ibiloglu and Caykoylu (2011) | 0 IN/OP | 4 | 0 | 96 | 38.7 | PTSD, SP, PD, OCD | Turkey |

| Watson et al. (2011) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 165 | 39.5 | AD | Australia |

| Altshuler et al. (2010) | 1 OP | 4 | 1 | 711 | 41.9 | PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Koyuncu et al. (2010) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 214 | 34.7 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD | Turkey |

| Magalhães et al. (2010) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 259 | 41.6 | OCD, AD | Brazil |

| Mantere et al. (2010) | 0 IN/OP | 4 | 0 | 144 | 38.0 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | Finland |

| Azorin et al. (2009) | 0 IN | 4 | 1 | 1090 | 43.0 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, AGR, PD, OCD, PD | France |

| Nery-Fernandes et al. (2009) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 62 | 42.0 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, AGR, PD, OCD, PD | Brazil |

| Grabski et al. (2008) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 73 | 44.6 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, PTSD Agoraphobia, OCD AD | Poland |

| Ciapparelli et al. (2007) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 56 | 35.8 | SAD, PD, OCD, AD | Italy |

| Kauer-Sant'Anna et al. (2007) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 162 | 43.1 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, PTSD Agoraphobia, OCD AD | Brazil |

| Levander et al. (2007) | 1 OP | 4 | 0 | 350 | 41.7 | PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Simon et al. (2007) | 1 OP | 4 | 1 | 120 | 44.2 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, AGR, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Altindag Abdurrahman et al. (2006) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 70 | 34.7 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, PTSD Agoraphobia, OCD AD | Turkey |

| Otto et al. (2006) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 918 | 40.6 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, AGR, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Pashinian et al. (2006) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 56 | 28.9 | SAD, SP, PD, OCD | Israel |

| Pini et al. (2006) | 0 IN | 4 | 1 | 189 | 33.5 | SAD, PD, OCD | Italy |

| Wilk et al. (2006) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 154 | NR | PD | USA |

| Zutshi et al. (2006) | 1 OP | 4 | 1 | 80 | 30.0 | GAD, SAD, PD, OCD, AD | India |

| Bauer et al. (2005) | 1 IN | 4 | 0 | 328 | 46.6 | PTSD, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Boylan et al. (2004) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 138 | 42.0 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | Canada |

| Simon et al. (2004) | 1 OP | 4 | 0 | 475 | 41.7 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, AGR, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Henry et al. (2003) | 0 IN | 4 | 1 | 318 | 53.3 | PD, OCD, AD | France |

| Pini et al. (2003) | 0 IN | 4 | 0 | 151 | 36.2 | PD | Italy |

| Simon et al. (2003) | 1 OP | 4 | 1 | 122 | 40.8 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Craig et al. (2002) | 1 IN/OP | 4 | 0 | 138 | NR | PD, OCD | USA |

| Tamam and Ozpoyraz (2002) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 70 | 33.4 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | Turkey |

| Vieta et al. (2001) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 129 | 40.9 | SAD, SP, PD, OCD | Spain |

| Yerevanian et al. (2001) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 35 | 39.8 | GAD, PTSD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

| Krüger et al. (2000) | 1 IN | 4 | 1 | 143 | 44.0 | GAD, SP, PD, OCD | Germany |

| Cassano et al. (1999) | 0 IN | 4 | 1 | 48 | 33.5 | SAD, PD, OCD | Italy |

| Pini et al. (1999) | 0 IN | 4 | 0 | 125 | 24.7 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD | Italy |

| Cosoff and Hafner (1998) | 0 IN | 4 | 1 | 20 | 34.8 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | Australia |

| Strakowski et al. (1998) | 0 IN | 4 | 0 | 77 | 25.0 | GAD, PTSD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD | USA |

| Pini et al. (1997) | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 24 | 37.9 | GAD, SAD, SP, PD, OCD, AD | Italy |

| Chen and Dilsaver, 1995a, Chen and Dilsaver, 1995b | 0 OP | 4 | 0 | 167 | 20.6 | PD, OCD | USA |

| Krüger et al. (1995) | 1 IN | 4 | 1 | 37 | 49.0 | OCD | Canada |

| Sharma et al. (1995) | 0 IN/OP | 4 | 1 | 25 | 37.8 | GAD, SAD, SP, AGR, PD, OCD | Canada |

| Shoaib and Dilsaver (1995) | 0 IN | 3 | 1 | 41 | 33.1 | PD | USA |

| Strakowski et al. (1995) | 0 IN/OP | 4 | 1 | 39 | 29.6 | GAD, PTSD, OCD | USA |

| Young et al. (1993) | 0 OP | 4 | 1 | 81 | 37.6 | GAD, PD, AD | Canada |

| Strakowski et al. (1992) | 0 IN | 4 | 1 | 41 | 31.6 | SP, PD, OCD, AD | USA |

AD = anxiety disorders. GAD = generalised anxiety disorder. NR = not reported. OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder. PD = panic Disorder. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. RDC = research diagnostic criteria. SAD = social anxiety disorder. SP = simple phobia.

All studies used DSM (III, III-R, IV) criteria for the diagnoses of bipolar and anxiety disorders, except Young et al. (1993), using RDC (Research Diagnostic Criteria) criteria.

1 = convenience sample, 0 = consecutive sample.

(IN) = Inpatient, (OP) = outpatient.

1 = low quality, 2 = low-to-medium quality, 3 = medium-to-high quality, 4 = high quality.

0 = no appreciable bias risk, 1 = low bias risk, 2 = low-to-medium bias risk, 3 = medium-to-high bias risk, and 4 = high bias risk.

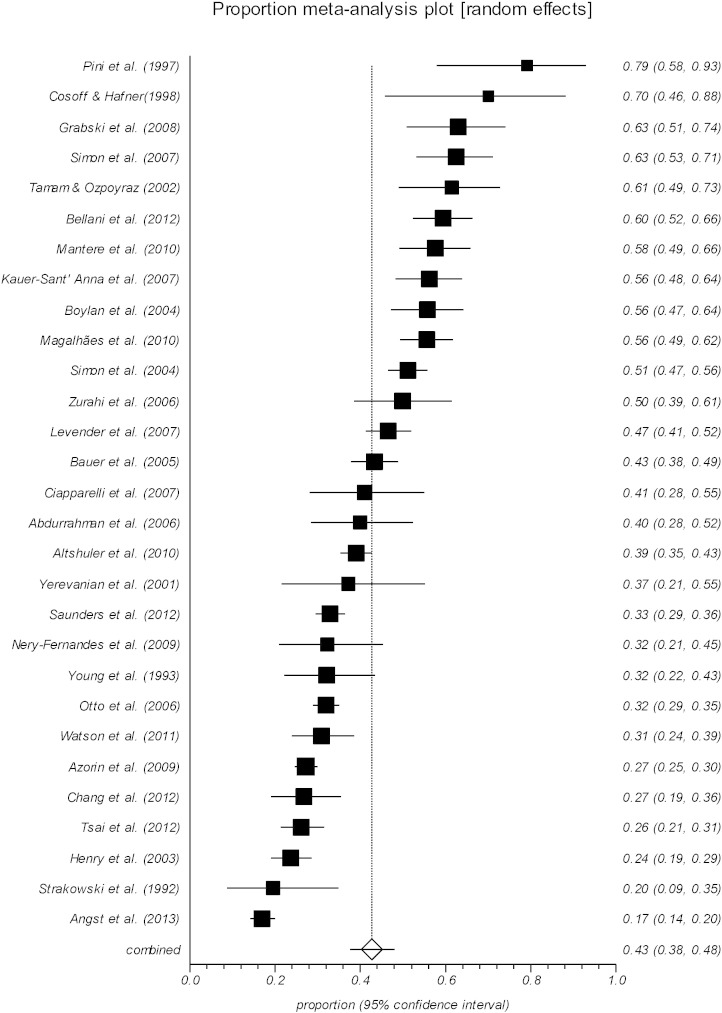

From the identified articles, we were unable to demonstrate the total comorbidity between bipolar disorder and all anxiety disorders confidently, as some of the individual studies examined only one or two subtypes of the anxiety disorders, e.g. GAD or OCD. However, in twenty-nine out of fifty-two articles which including 3064 individuals, we were able to extract the total lifetime comorbidity with anxiety disorders (Fig. 2). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of lifetime comorbidity of any anxiety disorders in bipolar disorder was 42.7% (95% CI 37.5–48.0) with high heterogeneity (Table 1). It should be noted that a higher prevalence rate of comorbid anxiety disorders is mainly due to the fact that some individuals have had multiple identified anxiety disorder conditions.

Fig. 2.

Lifetime anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

Table 1.

Summary of lifetime prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in bipolar I, publication bias and heterogeneity findings.

| Comorbid anxiety disorders | Number of studies | Total number of cases | Lifetime prevalence (95% CI) | Cochran Q (P value) | Heterogeneity I² (95% CI) | Begg-Mazumdar (P value) | Egger (95% CI) | Harbord (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | 29 | 3064 | 42.7% (37.5–48.0) | 575.62 (P < 0.0001) | 95.1% (94.2–95.8) | 0.167 (0.210) | 5.1 (2.1–8.0) | 4.3 (1.4–7.2) |

| Panic disorder | 45 | 1537 | 16.8% (13.7–20.1) | 775.97 (P < 0.0001) | 94.2% (93.3–94.9) | 0.273 (0.007) | 4.0 (2.4–5.7) | 2.6 (0.2–5.0) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 30 | 892 | 14.4% (10.8–18.3) | 478.00 (P < 0.0001) | 93.9% (92.7–94.9) | 0.149 (0.256) | 4.0 (1.8–6.1) | 1.1 (− 1.6–3.9) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 25 | 1185 | 10.8% (7.3–14.9) | 678.29 (P < 0.0001) | 96.5% (95.9–96.9) | 0.193 (0.185) | 3.9 (0.6–7.2) | − 1.3 (− 4.4.1.7) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 43 | 808 | 10.7% (8.7–13.0) | 424.42 (P < 0.0001) | 90.1% (87.9–91.7) | 0.229 (0.030) | 3.4 (2.4–4.3) | 3.7 (1.9–5.4) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 32 | 921 | 13.3% (10.1–16.9) | 553.76 (P < 0.0001) | 94.4% (93.3–95.2) | 0.209 (0.095) | 4.0 (2.3–5.8) | 2.9 (0.1–5.7) |

| Specific phobia | 26 | 448 | 10.8% (8.2–13.7) | 185.39 (P < 0.0001) | 86.5% (81.7–89.6) | 0.286 (0.041) | 2.7 (0.9–4.4) | 1.3 (− 1.1–3.7) |

| Agoraphobia | 11 | 251 | 7.8% (5.2–11.0) | 101.16 (P < 0.0001) | 90.1% (84.8–93) | 0.381 (0.121) | 3.0 (0.7–5.3) | 4.7 (0.3–9.0) |

Heterogeneity interpretation: Cochrane test: a P value of <.1 is considered significant for the presence of statistical heterogeneity. I²: greater than 80% = moderate, I² greater than 90% = high.

Publication bias interpretation: Begg–Mazumdar test: P value < 0.05 is considered significant and indicates a presence of publication bias. Egger and Harbord tests: if the intercept differs significantly from zero, this may indicate that publication bias is present.

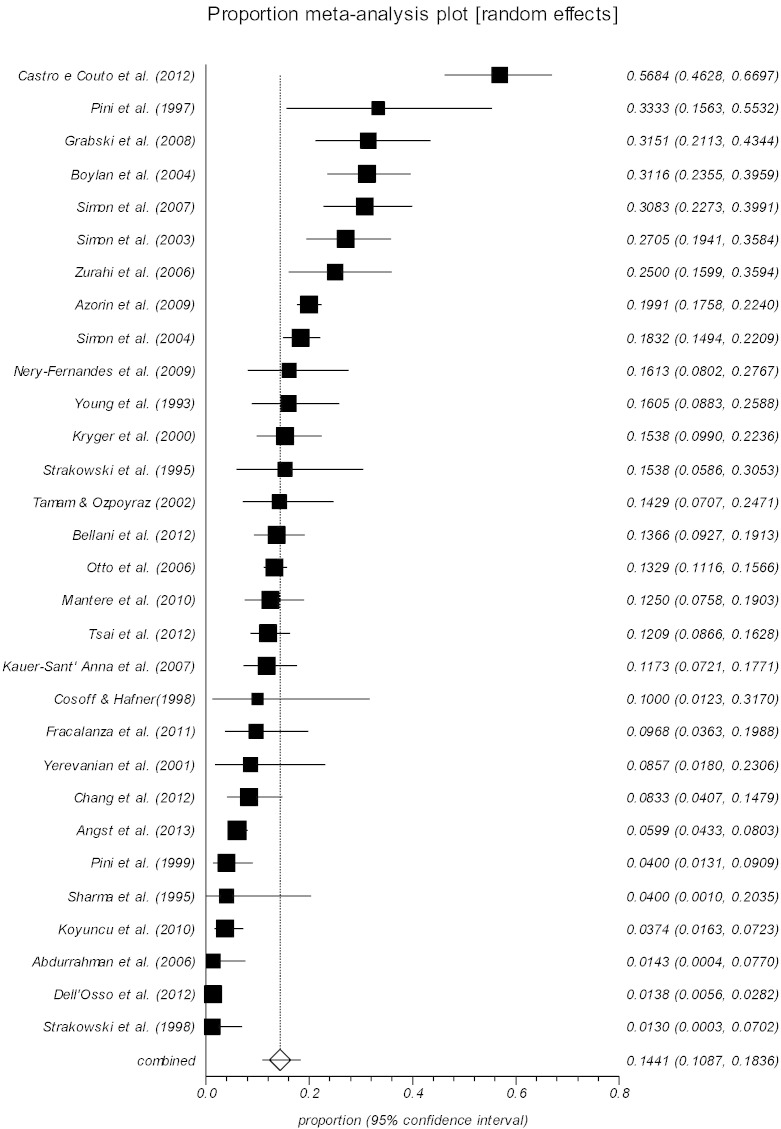

4.1. Lifetime GAD Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 30 relevant articles which including 892 individuals with lifetime comorbid GAD in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 3). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of GAD in individual studies ranged from 1.3% (95% CI 0.03–7.0) (Strakowski et al., 1992) to 56.8% (95% CI 46.2–66.9) (Castro e Couto et al., 2012). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid GAD was 14.4% (95% CI 10.8–18.3) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Infrequent reports of very low or very high prevalence in small studies suggest possible publication bias, as such studies are prone to take longer to be published; or the results not conforming to the desired outcome may not even be reported (Rothman and Greenland, 1998).

Fig. 3.

Lifetime GAD comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

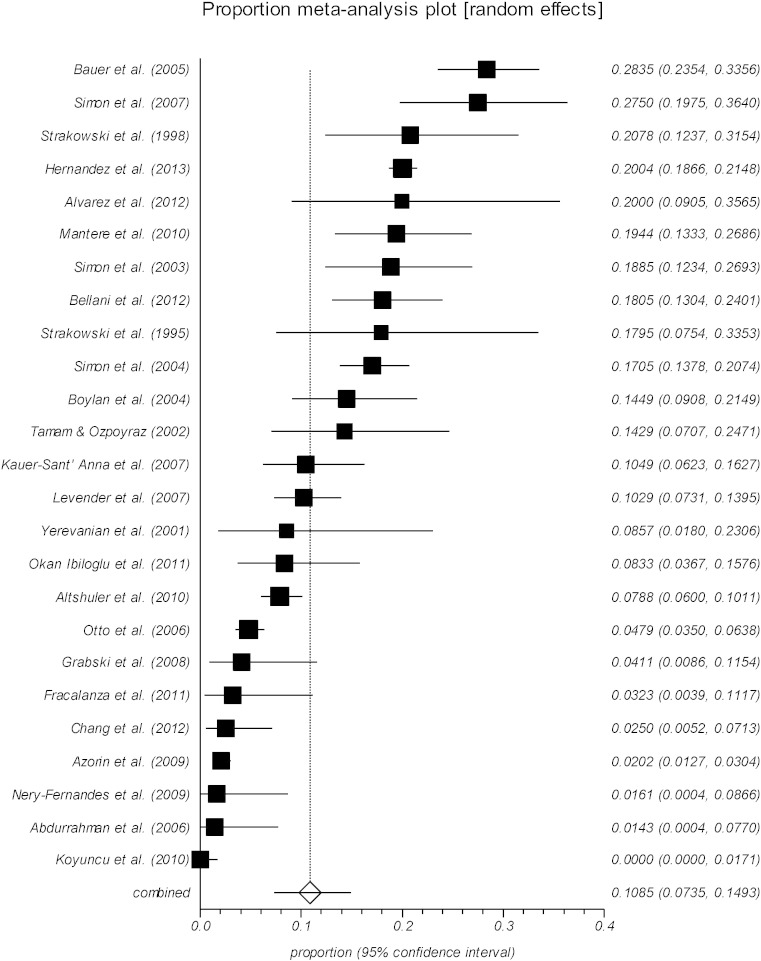

4.2. Lifetime PTSD Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 25 relevant articles which including 1185 individuals with PTSD lifetime comorbidity in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 4). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD in individual studies ranged from none (Koyuncu et al., 2010) to 28.3% (95% CI 23.5–33.5) (Bauer et al., 2005). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid PTSD was 10.8% (95% CI 7.3–14.9) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Lifetime PTSD comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

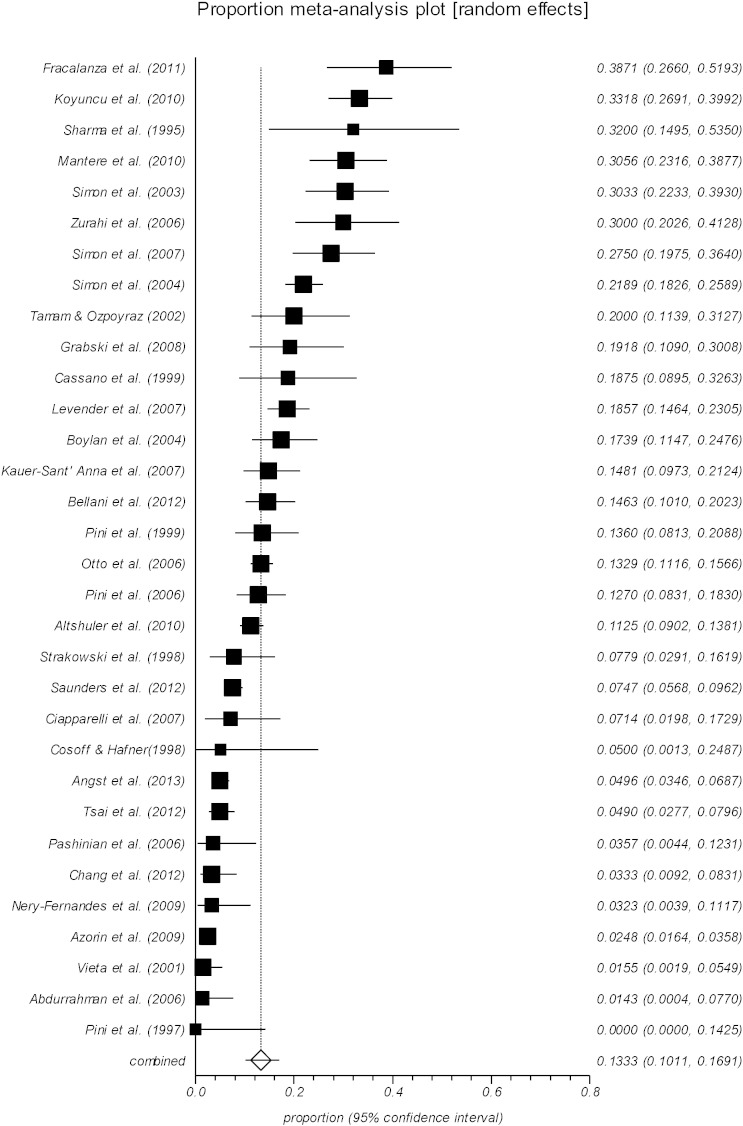

4.3. Lifetime SAD Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 32 relevant articles which including 921 individuals with lifetime social anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 5). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of social anxiety disorder in individual studies ranged from none (Pini et al., 1997) to 38.7% (95% CI 26.6–51.9) (Fracalanza et al., 2011). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid social anxiety disorder was 13.3% (95% CI 10.1–16.9) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Lifetime social anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

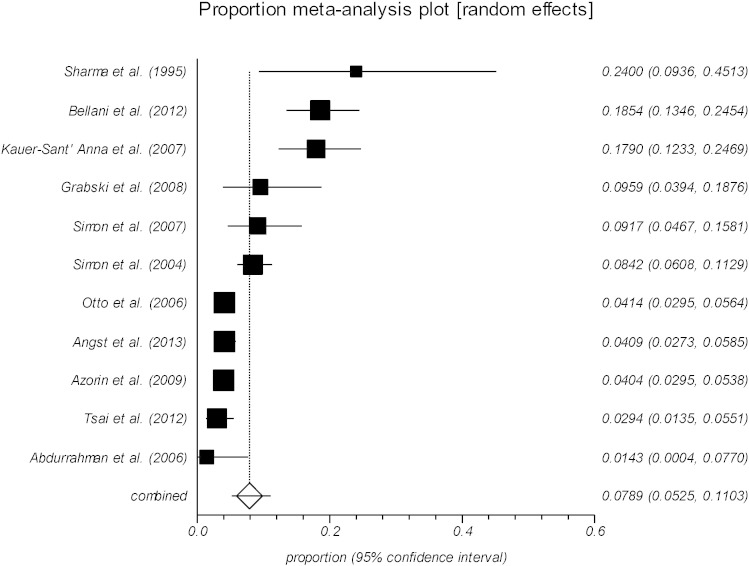

4.4. Lifetime Agoraphobia Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 11 relevant articles which including 251 individuals with lifetime agoraphobia comorbidity in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 6). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of agoraphobia in individual studies ranged from 1.4% (95% CI 0–7.7) (Altindag et al., 2006) to 24.0% (95% CI 9.3–45.1) (Sharma et al., 1995). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid agoraphobia was 7.8% (95% CI 5.2–11.0) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Lifetime agoraphobia comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

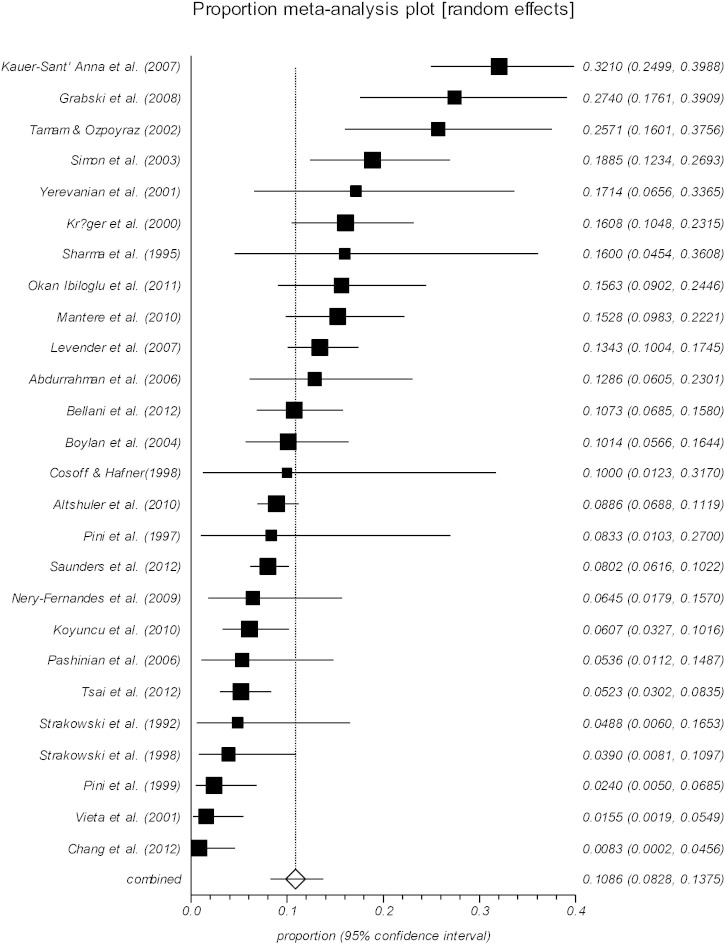

4.5. Lifetime Specific Phobia Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 26 relevant articles which including 448 individuals with lifetime specific phobia comorbidity in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 7). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of specific phobia in individual studies ranged from 0.8% (95% CI 0–4.5) (Chang et al., 2012) to 32.1% (95% CI 24.9–39.8) (Kauer-Sant'Anna et al., 2007). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid specific phobia was 10.8% (95% CI 8.2–13.7) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Lifetime specific phobia comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

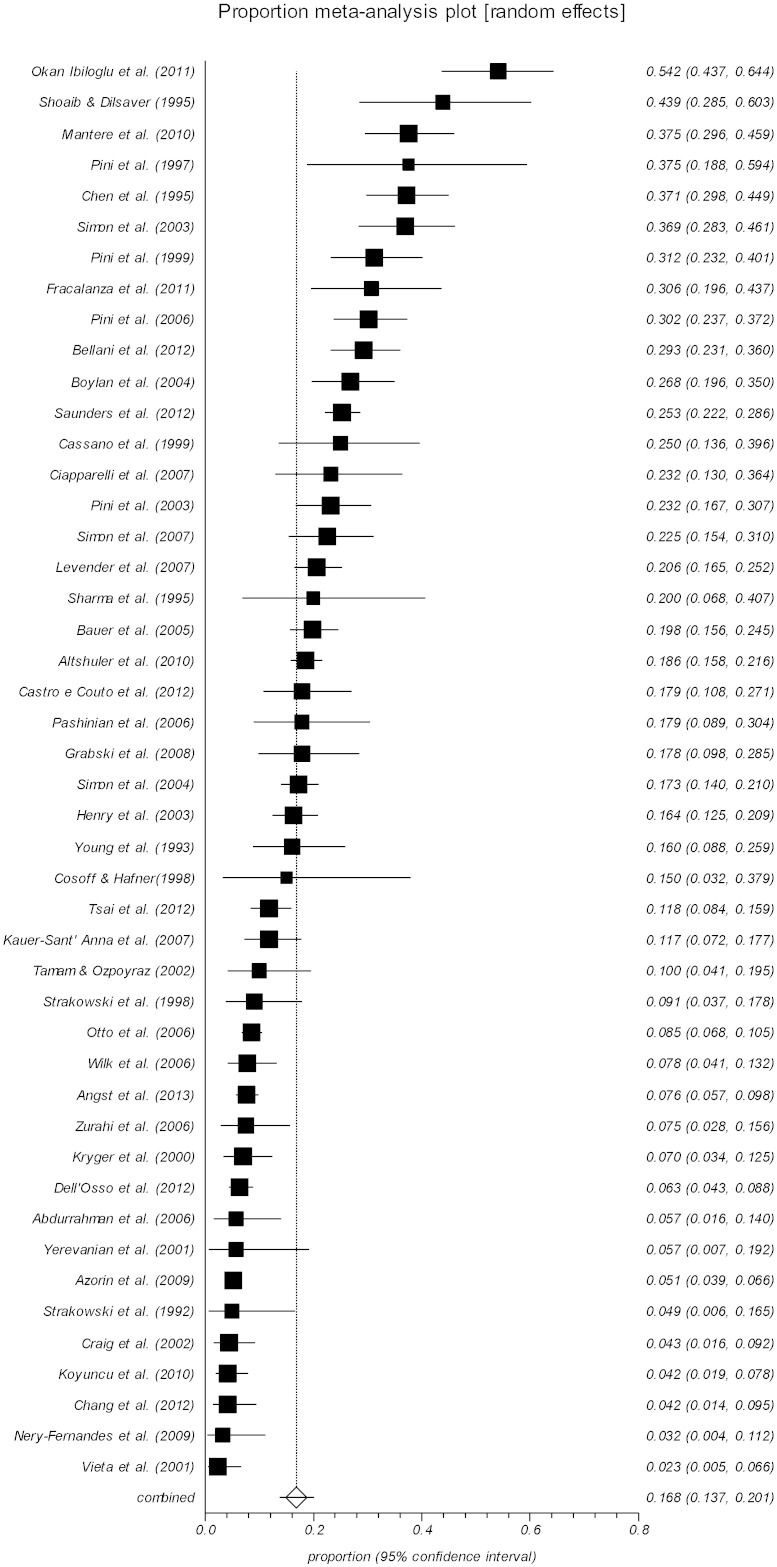

4.6. Lifetime Panic Disorder Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 46 relevant articles which including 1537 individuals with lifetime panic disorder comorbidity in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 8). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of panic disorder in individual studies ranged from 2.3% (95% CI 0.5–6.6) (Vieta et al., 2001) to 54.2% (95% CI 43.7–64.4) (Okan Ibiloglu and Caykoylu, 2011). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid panic disorder was 16.8% (95% CI 13.7–20.1) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Lifetime panic disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

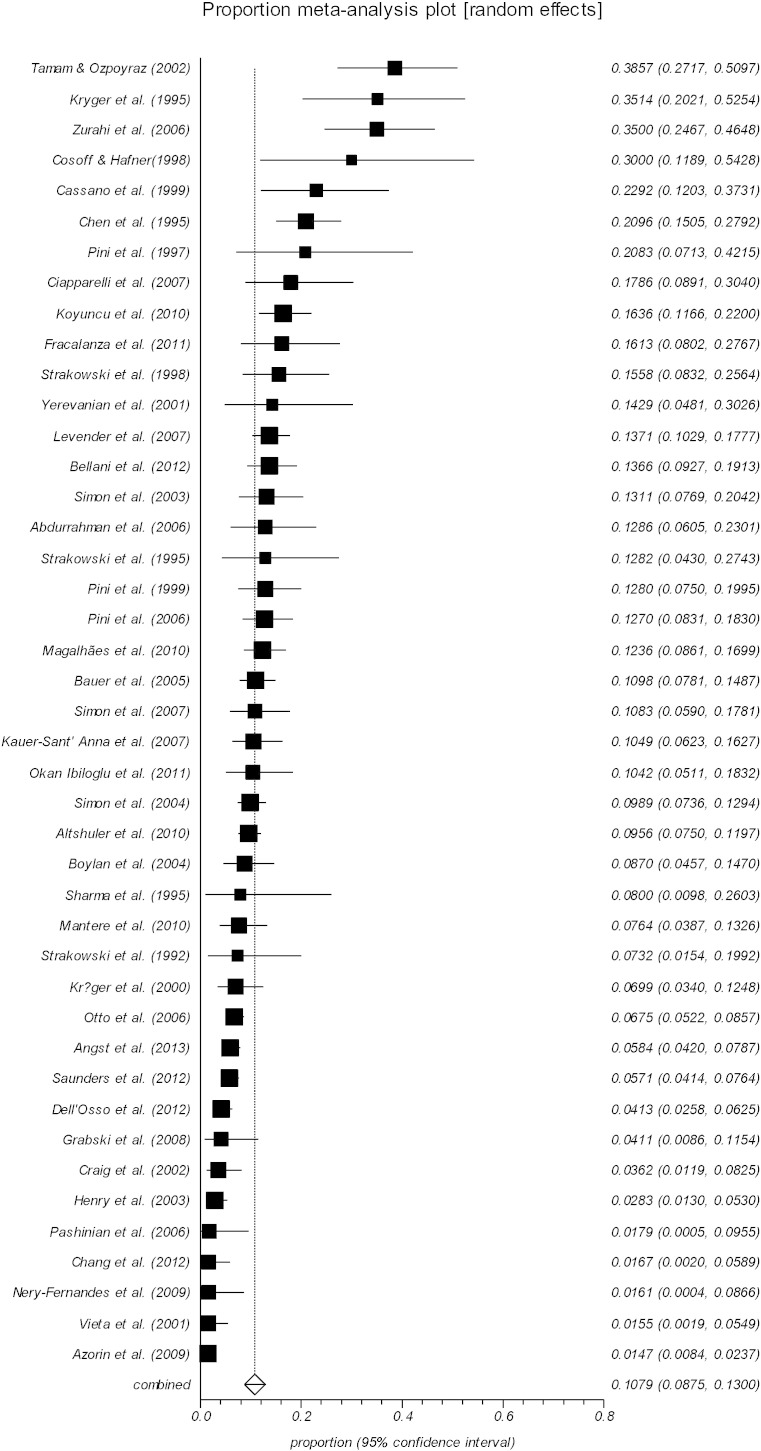

4.7. Lifetime OCD Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder

We identified 43 relevant articles which including 808 individuals with lifetime OCD comorbidity in bipolar affective disorder (Fig. 9). All studies were carried out in either psychiatric outpatient clinics or inpatient settings. The lifetime prevalence of OCD in individual studies ranged from 1.4% (95% CI 0.8–2.3) (Azorin et al., 2009) to 38.5% (95% CI 27.1–50.9) (Tamam and Ozpoyraz, 2002). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of comorbid OCD was 10.7% (95% CI 8.7–13.0) with high heterogeneity (Table 1 and Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Lifetime OCD comorbidity in bipolar disorder.

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous meta-analysis examining the lifetime prevalence of comorbidity between bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders. As expected, a large amount of variation in prevalence across studies was found by graphical representation of estimates and by indices of heterogeneity. Despite this wide variation, pooled estimates are often useful to indicate the clinical burden of the comorbidities. All original studies were carried out according to interview-based methods of defining bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders, using comprehensive and fully structured tools, such as CIDI and SCID-IV and were conducted by trained interviewers. In total, we were able to identify 52 studies consisting of 13,656 individuals with bipolar affective disorder, for whom the lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders had been examined (Table 2). Meta-analysis pooled prevalence of the lifetime comorbidity of any anxiety disorders in 29 out of 52 studies was 42.7% (95% CI 37.5–48.0). However, it is to be noted that the total number of individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders was less than the above number, as some individuals had more than one identified anxiety disorder comorbidity. To examine the impact of single versus multiple anxiety disorder comorbidities, Boylan et al. (2004) found no significant differences between the groups of patients with 1, 2, 3 or more anxiety disorders for any of the outcome measures (all P values > 0.15).

Whenever possible, we only used the data for bipolar type I, as some studies such as the Bridge Study (Angst et al., 2013) found higher prevalence of lifetime comorbidity in type II (27.5% vs. 16.9%). Otherwise we only included the data when the authors clearly reported no significant differences in their findings between types I and II.

We found the overall rate of anxiety disorders, as well as the type of anxiety disorder in clinical samples varied widely. To explain such variety, we found no significant differences in sampling settings as to be either inpatient or outpatient. One explanation may be the cross-national variability of the primary studies. Other suggested contributory factors include having different methodological approaches, such as being in different phase of bipolarity at comorbidity assessment; and assessment method used in diagnosis and evaluation of period or lifetime prevalence.

Some of primary studies (Boylan et al., 2004, Angst et al., 2013, Grabski et al., 2008) found GAD to be the most common comorbid anxiety disorder in bipolar disorder. However the majority of studies found panic disorder as the most common comorbid anxiety disorder in bipolar disorder (Okan Ibiloglu and Caykoylu, 2011, Shoaib and Dilsaver, 1995). Wittchen et al. (1994) reported strong lifetime comorbidity between GAD and affective disorder (mania 10.5%, major depression 62.4% and dysthymia 39.5%).

With regard to the effects of single vs. multiple comorbid anxiety disorders, in a sample of 153 bipolar I inpatient cases, Ghoreishizadeh et al. (2009) identified 43% rate of anxiety disorders with no significant relationship between anxiety disorders and the severity of bipolar disorder and the duration of hospitalisation. Their findings were consistent with the results of a study by Henry et al. (2003), but contrary to the results of some other studies (El-Mallakh and Hollifield, 2008, Sharma et al., 1995, Masi et al., 2007, Dilsaver and Chen, 2003, Dineen Wagner, 2006). Using a random effect meta-analysis in our pooled data, we found panic disorder to be the most common comorbid anxiety disorder in bipolar disorder: 16.8% (95% CI 13.7–20.1), followed by GAD and social anxiety disorder with a prevalence of 14.4% (95% CI 10.8–18.3) and 13.3% (95% CI 10.1–16.9), respectively. We also estimated the rate of lifetime comorbidity between bipolar disorder and PTSD, specific phobia, OCD and agoraphobia to be 10.8% (95% CI 7.3–14.9), 10.8% (95% CI 8.2–13.7), 10.7% (95% CI 8.7–13.) and 7.8% (95% CI 5.2–11.0), respectively.

Finally, in limited studies it has been suggested that the presence or absence of any particular comorbid anxiety disorders may alter the pattern and prognosis of bipolar disorder. For instance, Pini et al. (1997) suggested three patterns in association with anxiety and affective disorder: (i) GAD was found to be stronger associated with dysthymia than bipolar or unipolar depression; (ii) panic disorder was found to have a greater tendency to co-occur with bipolar disorder than with dysthymia and possibly than with unipolar depression; (iii) social phobia was less common in bipolar cases. Duffy et al. (2010) suggested a staging model: anxiety disorders appear as an early manifestation of psychopathology in high-risk youth who go on to develop bipolar illness. Perugi et al. (2001) suggested that social phobia most often precedes mania and then resolves, while other comorbid anxiety disorders tend to persist.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

Based on our experience with previous meta-analyses, we acknowledge that we may have missed studies and/or made data entry errors. We encourage readers to inform us of any missing studies or errors in the data. Updated lists of relevant studies and raw data will be available from the authors. We note several limitations to this analysis.

-

1.

Due to the large degree of variation across studies, the heterogeneity and publication bias were present. It is possible that some studies were not identified in the searches if they were not published in mainstream journals. There may have been some time lag bias, with smaller studies, or studies with unremarkable results, coming through to publication slower than larger studies.

-

2.

The included studies were of a variable quality. Although they all received a high methodological quality score, their findings cannot be easily compared or generalised. Prevalence studies have often used different diagnostic instruments, sampling procedures, case definitions and time frames for the diagnoses (e.g. lifetime, six month prevalence or current diagnoses), as well as different severity ratings for diagnostic decisions (Weissman et al., 1989).

-

3.

We acknowledge that the definitions of prevalence could vary slightly across studies, typically relying on cross-sectional assessment at different stages of the illness, and occasionally used convenience sampling.

-

4.

Lifetime prevalence rate in comparison to current or point prevalence usually provides a higher rate, as it comprises the proportion of the population who have ever had the disease. In contrast, current and period prevalence rate gives a figure at a single point or period in time (Jekel et al., 2001).

-

5.

Interview methods commonly underestimate the prevalence of anxiety disorders when compared with self-report scales. However, the consensus is that interview is methodologically superior to self-report, as it is objective and comparable between individuals, which may reduce the rate of false positive.

-

6.

We were unable to extract many correlates of different anxiety disorders because of limitations in the underlying dataset. It is unlikely that it would ever be possible to measure and record all potentially important covariates.

-

7.

A further limitation was the scarcity of data for non-DSM defined anxiety disorders, as none of the studies used explicit ICD criteria.

-

8.

Some criticism directed at the studies demonstrates how the association of bipolar disorder with anxiety disorders are with regard to the diagnostic criteria employed. For instance, in GAD, as well as in PTSD, there are criteria which prevail over those of bipolar disorder (Cox et al., 1990).

5.2. Clinical Implications

Previous studies suggest that patients with high anxiety scores were more likely to have made a suicide attempt. Since anxiety itself is related to suicidal behaviour, anxiety symptoms in bipolar patients may be an important risk factor for suicide (Weissman et al., 1989). Similarly, the strong relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol abuse (Cox et al., 1990, Kushner et al., 1990) also suggest that bipolar patients with high anxiety scores may be at risk of alcohol misuse. Kessler et al. (1997) suggested a high comorbidity with substance misuse, including alcohol in bipolar disorder could represent attempts to modulate the mood liability associated with bipolar disorder or that they could be symptoms of mood disturbance. Young et al. (1993) observed a trend toward lithium non-responsiveness in his high anxiety group of patients. There is also some contradictory evidence between anxiety and impulsivity in bipolar disorder. While some studies (Oosterlaan, 1998, Pliszka et al., 1999, Brown, 2000, Manassas et al., 2000) found anxiety as a protective factor for impulsiveness, others (Summmerfeldt et al., 2004, Taylor et al., 2008) found it an aggravating factor.

With regard to the psychopharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders in bipolar disorder, in the absence of any robust evidenced-based data, it will remain challenging and perhaps risky, particularly because of the concern that antidepressants may destabilise mood in bipolar patients, and benzodiazepines are problematic in patients with comorbid alcohol/substance use disorders. In the presence of bipolar disorder, the first choice of anxiolytic medication may be shifted towards a medication covering both conditions, such as a typical or atypical antipsychotic. However, the effect of atypical antipsychotic (e.g. olanzapine, quetiapine and lurasidone) on anxiety during bipolar depression should be viewed with caution and as preliminary (Tohen et al., 2003, Calabrese et al., 2005, Loebel et al., 2014a, Loebel et al., 2014b). It is also suggested that comorbid anxiety disorders can be effectively treated in bipolar patients using psychological interventions. There is some evidence in favour of CBT (Baer et al., 1985, Bowen and D'Arcy, 2003, Hamblen et al., 2004, Mueser et al., 2008, Mueser et al., 2007, Provencher et al., 2010, Rosenberg et al., 2004) (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Miklowitz et al., 2009, Williams et al., 2008), in the treatment of anxiety comorbid to bipolar disorder. On the other hand, interpersonal therapy (Frank et al., 2005) and family therapy (Gaudiano and Miller, 2005) would not seem to offer any significant benefit to this group. Finally, the co-occurrence of more than one anxiety disorder in an individual may limit the utility of psychotherapy in patients with bipolar disorder (Deckersbach et al., 2014).

6. Conclusion

Interest in the co-occurrence of bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders has grown markedly in the past two decades. Our results, in line with previous studies, suggest that anxiety disorders co-occur frequently in patients with bipolar illness. However, it is unclear if this is an expression of the pathology of two independent and distinct disorders or an additive interaction of the coexisting disorders.

More detailed information on the patterns of response to psychological and psychopharmacological interventions among those with bipolar disorder with or without anxiety disorders may be useful in further delineating the aetiological significance (e.g. shared neurobiological mechanisms) of the co-occurrence of bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders. In addition, more in-depth examinations of the temporal relationship between the onset of bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders using longitudinal designs may be helpful in understanding aetiology and developing interventions that could delay or even prevent the onset of bipolar disorder among those at high risk. The diagnostic issues at the interface of affective and anxiety disorders are particularly difficult because of the substantial symptom overlap. Although some advances have recently been made, the treatment of co-existing conditions has clinically remained challenging. As with its companion studies on the prevalence of comorbidities, we hope that the current review will populate and generate the hypotheses. Paradoxes such as this can be a powerful catalyst for advancing knowledge.

Role of Funding Source

There was no funding source for this study. AJM had access to the raw data. BN had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. DN revised the final draft before being submitted.

Contributor

AJM designed the study and analysed the data. BN extracted the data and AJM supervised the data extraction. BN wrote and AJM revised subsequent drafts of the report. DN revised the final draft before being submitted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allgulander C., Lavori P.W. Excess mortality among 3,302 patients with ‘pure’ anxiety neurosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1991;48:599–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810310017004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altindag A., Yanik M., Nebioglu M. The comorbidity of anxiety disorders in bipolar I patients: prevalence and clinical correlates. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2006;43:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler L.L., Kupka R.W., Hellemann G., Frye M.A., Sugar C.A., McElroy S.L. Gender and depressive symptoms in 711 patients with bipolar disorder evaluated prospectively in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167:708–715. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez M.J., Rowa P., Foguet Q., Osés A., Solà J., Arrufat F.X. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity and clinical implications in patients with severe mental illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012;200:549–552. doi: 10.1097/nmd.0b013e318257cdf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J., Gamma A., Bowden C.L., Azorin J.M., Perugi G., Vieta E. Evidence-based definitions of bipolar-I and bipolar-II disorders among 5,635 patients with major depressive episodes in the Bridge Study: validity and comorbidity. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013;263:663–673. doi: 10.1007/s00406-013-0393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J., Gamma A., Endrass J., Hantouche E., Goodwin R., Ajdacic V. Obsessive–compulsive syndromes and disorders: significance of comorbidity with bipolar and anxiety syndromes. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005;255:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azorin J.M., Kaladjian A., Adida M., Hantouche E.G., Hameg A., Lancrenon S. Psychological correlates of lifetime anxiety comorbidity in bipolar I patients: findings from a French National Cohort. Psychopathology. 2009;42:380–386. doi: 10.1159/000241193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer L., Minichiello W.E., Jenike M.A. Behavioural treatment in two cases of obsessive–compulsive disorder with concomitant bipolar affective disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1985;142:358–360. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M.S., Alshuler L., Evans D.R., Beresford T., Williford W.O., Hauger R. Prevalence and distinct correlates of anxiety, substance, and combined comorbidity in a multi-site public sector sample with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2005;85:301–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellani M., Hatch J.P., Nicoletti M.A., Ertola A.E., Zunta-Soares G., Swann A.C. Does anxiety increase impulsivity in patients with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder? J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012;46:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen R.C., D'Arcy C. Response of patients with panic disorder and symptoms of hypomania to cognitive behavioural therapy for panic. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:144–149. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan K.R., Bieling P.J., Marriott M., Begin H., Young L.T., MacQueen G.M. Impact of comorbid anxiety disorders on outcome in a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2004;65:1106–1113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.E. American Psychiatric Press; Washington DC: 2000. Attention Deficit Disorders and Comorbidities in Children Adolescents and Adults. [Google Scholar]

- Brunette M.F., Noordsy D.L., Xie H., Drake R.E. Benzodiazepine use and abuse among patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003;54:1395–1401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.10.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese J.R., Keck P.E., Macfadden W., Minkwitz M., Ketter T.A., Weisler R.H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression (for the BOLDER study group) Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:1351–1360. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano G.B., Pini S., Saettoni M.B., Dell'Osso L. Multiple anxiety disorder co-morbidity in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic features. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:474–476. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro e Couto T., Neves F.S., Machado M.C.L., Vasconcelos A.G., Correa H., Malloy-Diniz L.F. Assessment of impulsivity in bipolar disorder (BD) in comorbidity with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): revisiting the hypothesis of protective effect. Clin. Neuropsychiatr. J. Treat. Eval. 2012;9:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.H., Chen S.L., Chen S.H., Chu C.H., Lee S.Y., Yang H.F. Low anxiety disorder comorbidity rate in bipolar disorders in Han Chinese in Taiwan. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Boil. Psychiatr. 2012;36:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.W., Dilsaver S.C. Comorbidity for obsessive–compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02752-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.W., Dilsaver S.C. Co-morbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152:280–282. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa K.N., Levine J., Gershon S., Kupfer D.J. Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:191–195. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciapparelli A., Paggini R., Marazziti D., Carmassi C., Bianchi M., Taponecco C. Comorbidity with axis I anxiety disorders in remitted psychotic patients 1 year after hospitalization. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:913–919. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900015704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosoff S., Hafner R.J. The prevalence of comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 1998;32:67–72. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox B.J., Norton G.R., Swinson R.P., Endler N.S. Substance abuse and panic-related anxiety: a critical review. Behav. Res. Ther. 1990;28:385–393. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90157-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T., Hwang M.Y., Bromet E.J. Obsessive–compulsive and panic symptoms in patients with first-admission psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:592–598. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear K., Begg C.B. An approach to assessing publication bias prior to performing a meta-analysis. Stat. Sci. 1992;7:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T., Peters A.T., Sylvia L., Urdahl A.U., Magalhães P.V.S. Do comorbid anxiety disorders moderate the effects of psychotherapy for bipolar disorders? Results from STEB-BD. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:178–186. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Osso B., Buoli M., Bortolussi S., Camuri G., Vecchi V., Altamura A.C. Patterns of axis I comorbidity in relation to age in patients with bipolar disorder: a cross-sectional analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;130:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver S.C., Chen Y.W. Social phobia, panic disorder and suicidality in subjects with pure and depressive mania. J. Affect. Disord. 2003;77:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineen Wagner K. Bipolar disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A., Alda M., Hajek T., Grof P., Milin R., MacQueen G.M. Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;121:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mallakh S., Hollifield M. Comorbid anxiety in bipolar disorder alters treatment and prognosis. Psychiatr. Q. 2008;79:139–150. doi: 10.1007/s11126-008-9071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske U., Frank E., Mallinger A.G., Houck P.R., Fagiolini A., Shear M.K. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:956–962. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fracalanza K.A., McCabe R.E., Taylor V.H., Antony M.M. Bipolar disorder comorbidity in anxiety disorders: relationship to demographic profile, symptom severity, and functional impairment. Eur. J. Psychiatry. 2011;24:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Cyranowski J.M., Rucci P., Shear M.K., Fagolini A., Thase M.E. Clinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:905–911. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Kupfer D.J., Thase M.E., Mallinger A.G., Swartz H.A., Fagiolini A.M., Grochocinski V., Houck P., Scott J., Thompson W., Monk T. Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Arch. Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:996–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano B.A., Miller I.W. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar I disorder: relationship to depression severity and treatment outcome. Depress. Anxiety. 2005;21:71–77. doi: 10.1002/da.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreishizadeh M.A., Amiri S., Bakhshi S., Gholmirzaei J., Shafiee-Kandjani A.R. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders and substance abuse with bipolar mood disorders and relationship with clinical course. Iran. J. Psychiatry. 2009;4:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Grabski B., Dudek D., Datka W., Mączka G., Zięba A. Lifetime anxiety and substance use disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder and its relationship to selected variables. Gender and bipolar subtype differences in comorbidity. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2008;3:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.F., Stinson F.S., Dawson D.A., Chou S.P., Dufour M.C., Compton W. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblen J.L., Jankowski M.K., Rosenberg S.D., Mueser K.T. Cognitive-behavioural treatment for PTSD in people with severe mental illness: three case studies. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2004;7:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Harbord R.M., Egger M., Sterne J.A. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat. Med. 2006;25(20):3443–3457. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry C., Van den Bulke D., Bellivier F., Etain B., Rouillon F., Leboyer M. Anxiety disorders in 318 bipolar patients: prevalence and impact on illness severity and response to mood stabilizer. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003;64:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez J.M., Cordova M.J., Ruzek J., Reiser R., Gwizdowski I.S., Suppes T. Presentation and prevalence of PTSD in a bipolar disorder population: a STEP-BD examination. J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekel J.F., Elmore J.G., Katz D.L. 2nd ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 2001. Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Preventive Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Kauer-Sant'Anna M., Frey B.N., Andreazza A.C., Ceresér K.M., Gazalle F.K., Tramontina J. Anxiety comorbidity and quality of life in bipolar disorder patients. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2007;52:175–181. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.B. Prevalence and impact of comorbid anxiety and bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Rubinow D.R., Holmes C., Abelson J.M., Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol. Med. 1997;27:1079–1089. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter T.A. Diagnostic features, prevalence and impact of bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71 doi: 10.4088/JCP.8125tx11c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman G.L., Weissman M.M., Ouellette R. Panic attacks in the community: social morbidity and health care utilization. JAMA. 1991;265:742–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu A., Tϋkel R., Ӧzyildirim I., Meteris H., Yazici O. Impact of obsessive–compulsive disorder comorbidity on the sociodemographic and clinical features of patients with bipolar disorder. Compr. Psychiatry. 2010;51:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger S., Bräunig P., Cooke R.G. Comorbidity of obsessive–compulsive disorder in recovered inpatients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:71–74. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger S., Cooke R.G., Hasey G.M., Jorna T., Persad E. Co-morbidity of obsessive–compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 1995;34:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00008-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner M.G., Sher K.J., Beitman B.D. The relationship between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1990;147:685–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterback D., Vora R., Rakow M. The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported health problems. Psychosom. Med. 2005;67:939–947. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188572.91553.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.H., Dunner D.L. The effect of anxiety disorder comorbidity on treatment resistant bipolar disorders. Depress. Anxiety. 2008;25:91–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levander E., Frye M.A., McElroy S., Suppes T., Grunze H., Nolen W.A. Alcoholism and anxiety in bipolar illness: differential lifetime anxiety comorbidity in bipolar I women with and without alcoholism. J. Affect. Disord. 2007;101:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel A., Cucchiaro J., Silva R., Kroger H., Hsu J., Sarma K. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar 1 depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:160–168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel A., Cucchiaro J., Silva R., Kroger H., Sarma K., Xu J. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;171:169–177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães P.V.S., Kapczinski N.S., Kapczinski F. Correlates and impact of obsessive–compulsive comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Compr. Psychiatry. 2010;51:353–356. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manassas K., Tannock R., Barbosa J. Dichotic listening and response inhibition in children with comorbid anxiety disorders in ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2000;39:1152–1159. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantere O., Isometsä E., Ketokivi M., Kiviruusu O., Suominen K., Valtonen H.M. A prospective latent analyses study of psychiatric comorbidity of DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi G., Perugi G., Millepiedi S., Toni C., Mucci M., Bertini N. Clinical and research implications of panic-bipolar comorbidity in children and adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy S.L., Alshuler L.L., Suppes T., Keck P.E., Jr., Frye M.A., Denicoff K.D. Axis I psychiatric co-morbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:420–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R.S., Soczynska J.K., Bottas A., Bordbar K., Konarski J.Z., Kennedy S.H. Anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:665–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlowicz M.V., Stein M.B. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:669–682. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz D.J., Alatiq Y., Goodwin G.M., Geddes G.R., Fennell M.J.V., Dimidijan S., Hauser M., Williams J.M.G. A pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder. Int. J. Cog. Ther. 2009;2:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Cook D.J., Eastwood S., Olkin I., Rennie D., Stroup D.F. Improving the quality of report of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;62:1006–1012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser K.T., Bolton E., Carry P., Bradley M., Ahlgren K., DiStaso D., Gilbride A., Liddell C. The Trauma Recovery Group: a cognitive behavioural program for post-traumatic stress disorder in persons with severe mental illness. Community Ment. Health. 2007;43:281–304. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser K.T., Rosenberg S.D., Xie H., Jankowski M.K., Bolton E.E., Lu W., Hemblen J.L., Rosenberh H.J., McHugo G.J., Wolfe R. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008;76:259–271. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser K.T., Goodman L.B., Trumbetta S.L., Rosenberg S.D., Osher F.C., Vidaver R. Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998;66:493–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nery-Fernandes F., Quarantini L.C., Galvão-de-Almeida A., Rocha M.V., Kapczinski F., Miranda-Scippa A. Lower rates of comorbidities in euthymic bipolar patients. World J. Biol. Psychiatr. 2009;10:474–479. doi: 10.1080/15622970802688929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okan Ibiloglu A., Caykoylu A. The comorbidity of anxiety disorders in bipolar I and bipolar II patients among Turkish population. J. Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldani F., Sullivan P.F., Pedersen N.L. Mania in the Swedish Twin Registry: criterion validity and prevalence. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2005;39:235–243. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterlaan J. Response inhibition and response re-engagement in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, disruptive, anxious and normal children. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;1:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osby U., Brandt L., Correia N., Ekbom A., Sparén P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:844–850. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M.W., Simon N.M., Wisniewski S.R., Miklowitz D.J., Kogan J.N., Reilly-Harrington N.A. STEP-BD Investigators. Prospective 12-month course of bipolar disorder in out-patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;189:20–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashinian A., Faragian S., Levi A., Yeghiyan M., Gasparyan K., Weizman R. Obsessive–compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder patients with first manic episode. J. Affect. Disord. 2006;94:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugi G., Akiskal H.S., Toni C., Simonini E., Gemignani A. The temporal relationship between anxiety disorders and (hypo)mania: a retrospective examination of 63 panic, social phobic and obsessive-compulsive patients with co-morbid bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2001;67:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S., Cassano G.B., Simonini E., Savino M., Russo A., Montgomery S.A. Prevalence of anxiety disorders co-morbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J. Affect. Disord. 1997;42:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S., Dell'Osso L., Amador X.F., Mastrocinque C., Saettoni M., Cassano G.B. Awareness of illness in patients with bipolar I disorder with or without comorbid anxiety disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2003;37:355–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S., Dell'Osso L., Mastrocinque C., Marcacci G., Papasogli A., Vignoli S. Axis I comorbidity in bipolar disorder with psychotic features. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1999;175:467–471. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.5.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini S., Maser J.D., Dell'Osso L., Abelli M., Muti M., Gesi C. Social anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with bipolar disorder: a clinical replication. J. Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:1148–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka S.R., Carlson C., Swanson J.M. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. ADHD with Comorbid Disorders: Clinical Assessment and Management. [Google Scholar]

- Provencher M.D., Thienot F., St-Amand J. 2010. Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder for Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Single Case Experimental Design. Poster Presented to the World Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S.D., Mueser K.T., Jankowski M.K., Salyers M.P., Acker K. Cognitive-behavioural treatment of PTSD in severe mental illness: results of a pilot study. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2004;7:171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K.J., Greenland S. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. Modern Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- Sala R., Axelson D.A., Castro-Fornieles J., Goldstien T.R., Ha W., Liao F. Comorbid anxiety in children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorder: prevalence and clinical correlates. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71:1344–1350. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05845gre. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders E.F.H., Fitzgerald K.D., Zhang P., McInnis M.G. Clinical features of bipolar disorder comorbid with anxiety disorders differ between men and women. Depress. Anxiety. 2012;29:739–746. doi: 10.1002/da.21932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier F.R., Johnson J., Horing C.D., Liebowitz M.R., Weissman M.M. Social phobia, comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiological sample. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1992;49:282–288. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Mazmanian D., Persad E., Kueneman K. A comparison of comorbid patterns in treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar depression. Can. J. Psychiatr. 1995;40:270–274. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib A., Dilsaver S.C. Panic disorder in subjects with pure mania and depressive mania. Anxiety. 1995;1:302–304. doi: 10.1002/anxi.3070010611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon N.M., Otto M.W., Wisniewski S.R., Fossey M., Sagduyu K., Frank E. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–2229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon N.M., Smoller J.W., Fava M., Sachs G., Recette S.R., Perlis R. Comparing anxiety disorders and anxiety-related traits in bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2003;37:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon N.M., Zalta A.K., Otto M.W., Ostacher M.J., Fischmann D., Chow C.W. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007;41:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souètre E., Lozet H., Cimarosti I., Martin P., Chignon J.M., Ades J. Cost of anxiety disorders; impact of comorbidity. J. Psychosom. 1994;38:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski S.M., Keck P.E., McElroy S.L., Lonczak H.S., West S.A. Chronology of comorbid and principal syndromes in first-episode psychosis. Compr. Psychiatry. 1995;36:106–112. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski S.M., Sax K.W., McElroy S.L., Keck P.E., Hawkins J.M., West S.A. Course of psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes co-occurring with bipolar disorder after a first psychiatric hospitalization. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:465–471. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski S.M., Tohen M., Stoll A.L., Faedda G.L., Goodwin D.C. Comorbidity in mania at first hospitalisation. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1992;149:554–556. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summmerfeldt L.J., Kloosterman P.H., Antony M.M., Richter M.A., Swinson R.P. The relationship between miscellaneous symptoms and major symptom factors in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004;42:1453–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szadoczky E., Papp Z.S., Vitrai J., Rihmer Z. The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders in Hungary: results from a national epidemiologic survey. J. Affect. Disord. 1998;50:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamam L., Ozpoyraz N. Comorbidity of anxiety disorder among patients with bipolar I disorder in remission. Psychopathology. 2002;35:203–209. doi: 10.1159/000063824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C.T., Hirshfeld-Becker D.R., Ostacher M.J., Chow C.W., LeBeau R.T., Pollack M.H. Anxiety is associated with impulsivity in bipolar disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:868–876. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohen M., Vieta E., Calabrese J.R., Ketter T.A., Sachs G., Bowden C. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine–fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:1079–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Frost R.O., Steketee G., Gray K.D., Fitch K.E. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toniolo R.A., Caetano S.C., Da Silva P.V., Lafer B. Clinical significance of lifetime panic disorder in the course of bipolar disorder type I. Compr. Psychiatry. 2009;50:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H.C., Lu M.K., Yang Y.K., Huang M.C., Yeh T.L., Chen W.J. Empirically derived subgroups of bipolar I patients with different comorbidity patterns of anxiety and substance use disorders in Han Chinese population. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;136:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E., Colom F., Corbella B., Martinez-Arán A., Reinares M., Benabarre A. Clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in bipolar I patients. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson H.J., Swan A., Nathan P.R. Psychiatric diagnosis and quality of life: the additional burden of psychiatric comorbidity. Compr. Psychiatry. 2011;52:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M.M., Klerman G.L., Markowitz J.S., Ouellette R. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and attacks. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;321:1209–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911023211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk J.E., West J.C., Narrow W.E., Marcus S., Rubio-Stipec M., Rae D.S. Comorbidity patterns in routine psychiatric practice: is there evidence of underdetection and underdiagnosis? Compr. Psychiatry. 2006;47:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.M., Alatiq Y., Crane C., Barnhofer T., Fennell M.J., Duggan D.S. Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) in bipolar disorder: preliminary evaluation of immediate effects on between-episode functioning. J. Affect. Disord. 2008;107:275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.U., Essau C.A., Von Zerssen D., Krieg J.G., Zaudig M. Lifetime and six-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Munich Follow-up Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1992;241:247–258. doi: 10.1007/BF02190261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.U., Zhao S., Kessler R.C., Eaton W.W. DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994;51:355–364. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods S.W. The economic burden of bipolar disease. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2000;13:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt R.J., Henter I. An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1995;30:213–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00789056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerevanian B.I., Koek R., Ramdev S. Anxiety disorders comorbidity in mood disorder subgroup: Data from a mood disorders clinic. J. Affect. Disord. 2001;67:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L.T., Cooke R.G., Robb J.C., Janine C., Levitt A.J., Joffe R.T. Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 1993;29:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zutshi A., Janardhan Reddy Y.C., Thennarasu K., Chandrashekhar C.R. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders in patients with remitted bipolar disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;256:428–436. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]