Abstract

We evaluated a transformed core curriculum for the Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health (New York, New York) master of public health (MPH) degree. The curriculum, launched in 2012, aims to teach public health as it is practiced: in interdisciplinary teams, drawing on expertise from multiple domains to address complex health challenges.

We collected evaluation data starting when the first class of students entered the program and ending with their graduation in May 2014.

Students reported being very satisfied with and challenged by the rigorous curriculum and felt prepared to integrate concepts across varied domains and disciplines to solve public health problems. This novel interdisciplinary program could serve as a prototype for other schools that wish to reinvigorate MPH training.

Motivated by the need to restructure public health education to address 21st-century health challenges,1–7 we undertook a comprehensive reenvisioning of the Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health master of public health (MPH) core curriculum.8–10 To best prepare students for their professional careers, we decided to build expanded and more rigorous content for core MPH training, which would nurture strong disciplinary skills while fostering interdisciplinary competence, feature interdisciplinary team teaching as a tangible model of interdisciplinary collaboration, and enable students to translate classroom-based knowledge and research into better public health programs and outcomes.

When we embarked on the curriculum renewal initiative, we implemented a thorough and wide-ranging plan for ongoing evaluation of the student experience to track our progress and identify areas for improvement.10 We first offered the new core curriculum in fall 2012. Two years later, in May 2014, the first full cohort who studied under the new curriculum had graduated from the program. We have presented data from those students to characterize the degree to which we have achieved our aims. These results can be considered short term because the effects of a curriculum should last a lifetime. But this is our first look at a complete cohort from start to finish of the 2-year MPH degree and our first opportunity to assess students’ learning outcomes and their overall experience in a radically redesigned MPH curriculum.

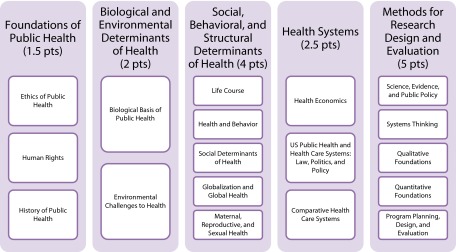

The design of the new Columbia core curriculum is thoroughly described in an earlier article9; it includes (1) an intensive and integrated first-semester core curriculum that emphasizes a life course approach to prevention in which concepts, topics, and skills are addressed in multiple contexts and across disciplines (Figure 1); (2) a new, case-based course called “Integration of Science and Practice,” which is designed to foster decision-making and critical thinking skills; and (3) a new course, “Leadership and Innovation,” which is intended to develop skills in communication, teamwork, leadership, and professionalism and an enhanced capacity for creative thinking. Although we offer various timelines for the completion of the MPH degree to meet the needs of a diverse student body, the modal MPH student completes the degree after 2 years of full-time study.

FIGURE 1—

Contents of new core curriculum for masters of public health students entering in fall 2012: Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY.

Note. The course–module boxes are not drawn to scale. Each module ranged in duration from 6 to 30 sessions, with total sessions in the studio reflected by the points allocated to it (in parentheses).

METHODS

We sought extensive student input throughout the 2-year program. Student input was intended to guide both short-term improvements to the curriculum, anticipating that such significant curricular change would face inevitable obstacles that would benefit from immediate feedback, and longer-term improvements that could ensure the curriculum evolved to meet changing student and pedagogic imperatives over time. The final plan for student feedback incorporated several elements; these are summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2—

Key elements of the student evaluation plan: Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY; 2012–2014.

Note. MPH = master of public health.

The incoming MPH cohort of fall 2012 comprised 376 students, about 77% of whom were enrolled in the 2-year MPH program, 17% in the accelerated (1-year) MPH curriculum for advanced professionals or related dual degree programs, and the remainder in a 16-month program offered to a subset of students in health policy and management. The cohort was 79% women and aged 26 years on average. Students came from 38 states across the United States and 30 different countries. Admission requirements include documented writing and quantitative ability and submission of a personal statement that demonstrates strong commitment to the values and principles of public health. Full details on applying and a profile of the student body can be found at https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/become-student/apply/process/faq.

RESULTS

Per the longitudinal panel survey (LPS) and random sample survey (RSS) protocols described in Figure 2 and an earlier article,10 we surveyed students about every 2 weeks during the first, intensive core semester. Response rates ranged from 55% to nearly 100%. There was a high degree of consistency between responses from the LPS and RSS samples for most questions. We anticipated some differences because we asked the LPS respondents to characterize their experiences over the past 2 weeks only, whereas we invited the RSS respondents to characterize their experiences from the start of the term until the present point in time.

One of the goals of curriculum renewal was to increase the rigor of the MPH core. Over the 15 weeks of the first semester, 75% to 100% of the LPS and RSS survey respondents indicated that they felt somewhat or extremely intellectually challenged by the new curriculum (on a scale from 1 “not challenged at all” to 4 “extremely challenged”). This represented a change from previous years, because surveys of pre–curriculum renewal graduates indicated that the core curriculum was not as challenging as they had anticipated. Overall, 42% to 93% stated that the course workload was heavier or much heavier than expected (on a scale from 1 “much lighter than expected” to 4 “much heavier”). Students reported peak workload burden around the time of midterm examinations (late October through early November).

Although high demands are not necessarily undesirable for graduate study, we were concerned about students’ ability to manage the workload; so we also asked a further question about their “ability to keep up academically,” with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Unlike for most questions, responses differed somewhat for the LPS and RSS samples. The proportion disagreeing (strongly or somewhat) with the statement “I have been able to keep up academically” among the LPS sample ranged from 23% to 90%; consistent with the workload questions, students felt least able to keep up during midterms. By contrast, the proportion disagreeing with the “keeping up” question among the RSS sample was lower and ranged from 11% to 55% (also peaking during midterm time), perhaps suggesting a better ability to keep up academically among the RSS sample (or merely reflecting the different periods covered in the 2 survey formats). Finally, we also inquired whether students felt they had adequate academic support to meet the challenges of the new curriculum (with 3 possible responses: not adequate, adequate, and more than adequate). Overall, 67% to 92% of both samples reported that they received adequate or more than adequate academic support throughout the fall term.

When we asked students in real time to rate their overall experience in the fall term on a 4-point scale (extremely negative to extremely positive), we saw differences between the LPS and RSS samples. The proportion positive for the LPS sample ranged from 30% to 95%, whereas the corresponding proportion for the RSS varied from 62% to 89% (Table 1). Students felt least positive about the program during midterms, and positivity rates began gradually to improve from that point until the end of the semester.

TABLE 1—

Responses of the Longitudinal Panel Survey (LPS) and Random Sample Survey (RSS) Samples to Check-In and Satisfaction Surveys: Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY; 2012–2014

| Date | No. | Extremely Positive, % | Somewhat Positive, % | Somewhat Negative, % | Very Negative, % |

| LPS: How would you rate your experience over the past 2 weeks? | |||||

| 9/14/12 | 39 | 44 | 51 | 5 | 0 |

| 9/28/12 | 29 | 3 | 87 | 3 | 7 |

| 10/12/12 | 32 | 9 | 63 | 25 | 3 |

| 10/26/12 | 26 | 19 | 46 | 35 | 0 |

| 11/9/12 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 47 | 23 |

| 11/23/12 | 29 | 0 | 45 | 45 | 10 |

| 12/7/12 | 28 | 4 | 50 | 39 | 7 |

| RSS: How would you rate your experience so far? | |||||

| 9/14/12 | 35 | 31 | 52 | 17 | 0 |

| 9/28/12 | 30 | 33 | 50 | 17 | 0 |

| 10/12/12 | 34 | 24 | 56 | 12 | 9 |

| 10/26/12 | 27 | 19 | 70 | 4 | 7 |

| 11/9/12 | 29 | 3 | 60 | 34 | 3 |

| 11/23/12 | 35 | 3 | 63 | 26 | 9 |

| 12/7/12 | 31 | 16 | 65 | 16 | 3 |

Course Evaluations for the Core

Students completed course evaluations for each of the 18 modules in the core at the end of the fall 2012 term. Response rates ranged from 38% to 81% (with lower rates toward the end of the semester).

Overall course evaluations were strong, with few exceptions. When rating each module overall on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent), the overall average computed as 3.98 (good), which we interpreted as a very good showing for new courses. In addition, the majority (59%–96%) of students rated the course as good or excellent in 14 of 18 modules; only 4 modules had less than half of students rating the module as good or excellent.

Faculty Evaluation of Student Performance

With respect to level of academic preparation and student learning outcomes, 69% of core faculty rated the incoming fall 2012 class as somewhat or very well prepared academically, and 100% of core faculty felt that the students had a strong (24%) or adequate (76%) understanding of the core material by semester’s end.

This finding on student learning was also supported by core grades, which were strong, with modal grades of B+ or A in almost every course. Perhaps more telling, the total number of grades of incomplete (an easily measured and reasonably objective indicator of students in difficulty) given to any student in any 1 of 6 core studio courses was lower in fall 2012 (n = 37) than in the year before curriculum renewal (n = 70), even though class sizes were similar.

The First January Breather Survey

After a month-long break from classes, at the end of January 2013, students were again surveyed about the fall 2012 semester; 78% of students responded. They reported on core content, quality of courses, quality of instruction, their overall experience during the fall term, and their self-perceived ability to integrate concepts across the different courses in the core.

Using a scale from 1 (very negative) to 4 (very positive), a large majority of students (78%) felt positive (somewhat or very) about the overall experience in fall 2012; 83% responded positively about the quality of the courses, and 90% felt positive about the quality of the teaching. Roughly half of the students felt that “too many” topics were covered in the core. However, when asked about the content of each of the 18 core modules, the majority of students wanted the number of module sessions to remain the same or to increase in 17 of 18 modules; in only 1 case did a majority wish to see a decrease in the number of sessions. We interpret this to mean that although they recognized the core as ambitious, overall they enjoyed it and wanted deeper knowledge.

To evaluate the elusive goal of integration, we also asked students whether they were able to integrate concepts across modules in the core curriculum. Of the responding students, 98% reported that they could integrate content from module to module, either easily (72%) or with some difficulty (26%). Only 2% reported feeling unable to integrate content across core courses.

Case-Based and Leadership Courses

The Integration of Science and Practice course was a 2-semester sequence offered in fall 2012 and spring 2013. The Leadership and Innovation course was offered in spring 2013. We administered course evaluations at the end of each semester. Of the students, 61% responded to the Integration of Science and Practice survey for the fall 2012 term, and 75% to 76% of students responded to the surveys for Integration of Science and Practice and Leadership and Innovation at the end of the spring 2013 term.

Approximately 64% of students rated the fall Integration of Science and Practice course as good to excellent; this percentage increased to 81% in the spring Integration of Science and Practice course. Integration of Science and Practice students were queried about their self-perceived level of preparation for working collaboratively to solve public health problems; the scale ranged from 1 (very poorly prepared) to 5 (very well prepared). At the end of the fall 2012 term, 47% of students reported feeling well or very well prepared to work collaboratively; another 38% felt adequately prepared. At the end of the spring 2013 term, those figures increased to 75% well and very well prepared, with another 22% feeling adequately prepared.

The Leadership and Innovation course presented numerous challenges in both design and implementation. It encountered resistance from students at the onset of the course, with students expressing some skepticism about its utility for them at early career stages (especially in their first year of training). They also contested the structure and some of the content of the course throughout the spring 2013 term. At the end of the term, just under half (45%) of the respondents indicated that they felt positive or neutral about whether the course would contribute to their long-term career goals.

One element of the Leadership and Innovation course that students endorsed in large numbers was the final project, known as the “innovation challenge.” The goal of the project was to provide students, working in teams, an opportunity to apply their core knowledge and skills to address a significant public health problem identified by a selected client. The client, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, requested that students develop innovative strategies to increase physical activity and encourage healthy eating among middle school children in New York City schools.

Twenty teams of approximately 18 to 20 students competed against one another for the best project, producing written materials and videos to present their ideas. Students voted on one another’s projects, and the top 4 teams were given the opportunity to present their recommendations to representatives from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene during the final class session, which chose the ultimate winner. The winning group visited the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to present to a larger group of colleagues so that their proposal might be considered for implementation citywide. Although some students objected to a project that required them to work in an unfamiliar area, the challenge gave them an authentic experience developing a public health intervention for which one may not feel totally prepared, as often happens in the workplace. In the end, many students felt the challenge was the best part of the course.

The Second January Breather Survey

We surveyed the cohort entering in fall 2012 again during the middle of their second year of study. At this point, the student sample was reduced from 376 to 292, because of the 1-year and 16-month program students graduating and most dual degree students departing to the relevant partner schools.

The proportion responding to this survey was slightly lower than usual (about 67%). Of 195 respondents, 96% indicated that they were able to apply concepts from the core to their subsequent coursework (79% easily and 17% with some difficulty), and 82% reported the ability to apply core knowledge during the practicum (58% easily and 24% with difficulty).

The Graduate Exit Survey

We invited all graduates from the first class of the renewed MPH (all programs and time formats combined) to take an exit survey, and 68% (255/376) completed it (although not all respondents completed all questions). We repeated some of the same questions asked earlier in the program to get a sense of whether students’ perceptions of the new curriculum changed over time as they approached the program’s conclusion.

On a scale from 1 (very poorly prepared) to 5 (very well prepared), students self-assessed their level of preparation across several domains. Of the respondents, 51% rated themselves as well prepared or very well prepared for integrating course content across disciplines, with 37% feeling adequately prepared. With respect to using knowledge and skills across disciplines, 65% felt well or very well prepared, and 32% felt adequately prepared. Finally, with respect to working on interdisciplinary teams, 76% reported feeling well or very well prepared, and 22% felt adequately prepared.

Echoing responses on the January 2013 and January 2014 breather surveys, 96% of students said they could apply core knowledge to their departmental coursework easily (77%) or with difficulty (19%). Similarly, 89% reported being able to apply core concepts in their practicum work (62% easily; 27% with difficulty).

Overall, students expressed high levels of satisfaction with the academic and practical aspects of their MPH education (Table 2); 92% reported feeling satisfied or very satisfied with their level of preparation for a career in public health, and 94% were satisfied or very satisfied with their preparedness to apply public health concepts to address public health problems. In addition, approximately 90% of students were positive about their overall program experience, the quality of courses, and the quality of instruction (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Student (n = 249) Responses to Graduate Exit Survey Regarding Satisfaction With Curricular Components of Core and Overall MPH Program: Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY; 2012–2014

| Area | Very Satisfied, % | Somewhat Satisfied, % | Somewhat Dissatisfied, % | Very Dissatisfied, % |

| Satisfaction with disciplinary and cross-cutting curricular components of the MPH program | ||||

| Foundations of public health | 48 | 45 | 6 | 1 |

| Biological and environmental determinants of health | 42 | 52 | 4 | 1 |

| Social, behavioral, and structural determinants | 30 | 43 | 21 | 7 |

| Health systems | 48 | 41 | 9 | 2 |

| Methods for research design and evaluation | 46 | 41 | 10 | 2 |

| Problem solving | 36 | 49 | 12 | 2 |

| Diversity and cultural awareness | 31 | 45 | 19 | 5 |

| Communication skills | 18 | 51 | 22 | 9 |

| Leadership and innovation | 10 | 33 | 27 | 30 |

| Satisfaction with their MPH education overall | ||||

| Overall experience | 32 | 59 | 8 | 1 |

| Quality of courses | 31 | 55 | 12 | 2 |

| Quality of teaching | 46 | 46 | 7 | 1 |

Note. MPH = master of public health.

Likelihood of Recommending the Program

One of the key indicators we have used over the years to evaluate our programs is the response to the question “How likely are you to recommend your program to a friend with similar interests?” The responses to this question capture a broad continuum of the students’ perceptions of their experience of the program, including academic and nonacademic aspects, reflecting whether they found the program worthwhile and satisfying. Among 230 spring 2012 graduates (the last pre–curriculum renewal cohort), 73% were very likely (33%) or somewhat likely (40%) to recommend the program. These numbers increased markedly for the very first curriculum renewal cohort on graduation, with 84% of 240 respondents reporting that they were very (39%) or somewhat (45%) likely to recommend the program.

DISCUSSION

Comprehensive evaluation is necessary for the success of any educational program, and particularly for new programs.11–14 We relied heavily on student feedback to guide the deployment of the new Columbia MPH curriculum. Although response rates to our surveys varied over time, response rates were generally higher than expected, often close to or exceeding 70% or 75%, and much credit goes to the students for their generosity in providing such extensive feedback.

Students were generally very satisfied with the new program, but they expressed significant anxiety about their ability to keep up around the time of midterm examinations in the first semester. It is worth noting that this period also coincided with the occurrence of Hurricane Sandy in the New York region, which left some students, faculty, and staff without power for a week or more, resulting in canceled classes and the inability to communicate and keep up with the workload.

Core faculty carefully reviewed feedback pertaining to relevance and adequacy of assessment methods after the fall 2012 semester; we adopted numerous changes to the methods and timing of assessments for the following year as a result of this evaluation. In addition, students noted the degree to which the core content was integrated but contrasted this effort with the lack of integration in the assessment methods. In other words, although our goal was to give students a synthesized framework for public health by taking an interdisciplinary approach to key concepts and skills, our assessment methods tested isolated learning. Therefore, the assessments did not reflect the desired learning outcomes. This has motivated core faculty to consider more integrated examination questions and article topics going forward to more closely mirror the demands of public health practice.

The Integration of Science and Practice course evaluations improved substantially from the fall term to the spring term. This may reflect increases in instructor confidence and experience in using the case-based method of teaching (which was new to most instructors at the time). The second semester also allowed for some instructor turnover and incorporated some written assignments in response to student feedback; this also may have increased student satisfaction.

The Leadership and Innovation evaluations indicated that we needed to do further work to refine the course. In particular, the faculty has questioned the structure of the Leadership and Innovation course, which included a combination of 400-person lectures and break-out activities in groups of 20 to 25 students. Clearly a large lecture format is not ideal for improving individual leadership skills, and greater emphasis on small groups or the complete elimination of large lectures may be considered in the future.

These data demonstrate that we achieved our primary goal: to launch an MPH curriculum with expanded, more rigorous, and more interdisciplinary content. We would also argue that the data on learning outcomes and the ability to integrate information from multiple disciplines attest to success in achieving the goals regarding strong disciplinary skills and interdisciplinary competence. Finally, the ability to translate classroom-based knowledge into action is a long-term outcome that we cannot cover in this article; this will require extended follow-up of the achievements of our program graduates as they pursue their careers in public health.

Taking all the evaluation feedback as a whole, students like the new MPH core curriculum and value it enough to recommend it to a friend with similar interests. In the words of one student:

The best part was when I realized how much I learned this fall semester. I noticed it most when reading the news or describing topics we learned to friends. I really felt like I learned so much about public health and feel like I have a solid foundation of knowledge in all areas of public health.

Students reported that they found themselves capable of integrating knowledge and skills across disciplines. Clearly, integration is hard to define and even harder to measure. But the first step in a truly integrative, interdisciplinary mindset must be the ability to see connections between disparate content areas; thus, students are on their way to achieving “interdisciplinary conversance.”15 In the words of one student in the January 2013 breather survey:

I would get so excited sometimes when my friends and I would discuss how concepts in one course could be applied to another course. Once the core was over and we began our holiday break, I found myself in discussions with different people about healthcare and public health issues, and it was quite rewarding being able to supplement my argument with material I had learned during the core.

It will be important to continue to follow these students (now alumni) to track how their perceptions vary over time and to gain further insights for making MPH education even better in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

This work builds on the involvement of many colleagues engaged in the Columbia curriculum renewal process, and we owe our deepest thanks to all of them. Particular thanks go to Sasha Rudenstine and the faculty who teach in the new curriculum.

Human Participant Protection

The Columbia University Medical Center institutional review board determined this study to be exempt because it falls into the categories of educational testing, survey, and observational research.

References

- 1.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebbie KM, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. A master of public health degree for the 21st century: key considerations, design features, and critical content of the core. Available at: http://www.aspph.org/educate/models/mph-degree-report. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 4.Sommer A. Toward a better educated public health workforce. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1194–1195. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1194. [Comment in Educating the public health workforce. Am J Public Health. 2001] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moser JM. Core academic competencies for master of public health students: one health department practitioner’s perspective. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1559–1561. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen DJ, Hovinga ME, Pass MA, Kohler C, Oestenstad RK, Katholi C. Assuring public health professionals are prepared for the future: the UAB public health integrated core curriculum. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(5):496–503. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh HK, Nowinski JM, Piotrowski JJ. A 2020 vision for education the next generation of public health leaders. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(2):199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Begg MD, Bayer R, Galea S. MPH education for the 21st century: motivation, rationale, and key principles for the new Columbia public health curriculum. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):23–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begg MD, Galea S, Bayer R, Walker JR, Fried LP. MPH education for the 21st century: design of Columbia University’s new public health curriculum. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):30–36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galea S, Fried LP, Walker JR, Rudenstine S, Glover JW, Begg MD. Developing the new Columbia core curriculum: a case study in managing radical curriculum change. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 1):S17–S21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scriven M. The methodology of evaluation. In: Tyler RW, Gagné RM, Scriven M, editors. Perspectives of Curriculum Evaluation. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1967. pp. 39–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stake RE. The countenance of educational evaluation. Teach Coll Rec. 1967;68:523–540. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pancer SM, Westhues A. A developmental stage approach to program planning and evaluation. Eval Rev. 1989;13(1):56–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi PH, Freeman HE, Lipsey MW. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. 7th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Hartesveldt C, Giordan J. National Science Foundation. Impact of transformative interdisciplinary research and graduate education on academic institutions: workshop report. 2008. Available at: http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2009/nsf0933/igert_workshop08.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2010.