Abstract

Background/Aims:

Most pesticide formulations contain both chief and additive ingredients. But, the additives may not have been tested as thoroughly as the chief ingredients. The surfactant, nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40), is an additive frequently present in pesticide formulations. We investigated the effects of NP40 and other constituents of a validamycin pesticide formulation on cell viability and on the expression of genes involved in cell damage pathways.

Methods:

The effects of validamycin pesticide ingredients on cell viability and of NP40 on the mRNA expression of 80 genes involved in nine key cellular pathways were examined in the human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cell line.

Results:

The chemicals present in the validamycin pesticide formulation were cytotoxic to SK-N-SH cells and NP40 showed the greatest cytotoxicity. A range of gene expression changes were identified, with both up- and down-regulation of genes within the same pathway. However, all genes tested in the necrosis signaling pathway were down-regulated and all genes tested in the cell cycle checkpoint/arrest pathway were up-regulated. The median fold-change in gene expression was significantly higher in the cell cycle checkpoint/arrest pathway than in the hypoxia pathway category (p = 0.0064). The 70 kDa heat shock protein 4 gene, within the heat shock protein/unfolded protein response category, showed the highest individual increase in expression (26.1-fold).

Conclusions:

NP40 appeared to be particularly harmful, inducing gene expression changes that indicated genotoxicity, activation of the cell death (necrosis signaling) pathway, and induction of the 70 kDa heat shock protein 4 gene.

Keywords: Validamycins, Surface-active agents, Nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol, Gene expression, Cell damage pathways

INTRODUCTION

Pesticides are used to increase food production by reducing the loss of crops to weeds, insects, fungal infections, parasites, and rodent pests. However, pesticides can also have negative impacts on non-target organisms. Each year, hundreds of thousands of people around the world die from the effects of pesticide use or misuse [1].

Validamycin, also called validamycin A, is a non-systemic fungicidal antibiotic [2] that is particularly effective against soil-borne diseases [3]. Pesticide Action Network North America has described validamycin as “not acutely toxic,” since its median lethal dose (LD50) exceeds 20,000 mg/kg (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 1994). Until recently, there was no evidence that validamycin caused illness in humans. However, we recently encountered a patient showing hypotension, unconsciousness, hypoxia, and high anion gap metabolic acidosis after ingesting 200 mL of an undiluted validamycin herbicide preparation containing a range of chemicals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Validamycin formulation constituents

| Function | Ingredient (CAS number) | Content, %a |

|---|---|---|

| Active ingredient | Validamycin (37248-47-8) | –5.0 |

| Emulsifier | NP40 (9016-45-9) | –2.0 |

| Supplement | Methanol (67-56-1) | –5.0 |

| Supplement | Potassium hydroxide (1310-58-3) | < 0.1 |

| Stabilizer | Sorbic acid (110-44-1) | < 0.1 |

| Coloring | Acid yellow 17, disodium salt (6359-98-4) | < 0.1 |

| pH regulator | Sulfuric acid (7664-93-9) | < 0.1 |

| Antifoam | Silicones and siloxanes, dimethyl (63148-62-9) | < 0.1 |

| Solvent | Water (7732-18-5) | ~87.0 |

| Total | 100 |

CAS, chemical abstracts service; NP40, nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol.

Content, usually presented as “weight %” or “weight by volume” in the formulation, was undisclosed by the manufacturer. Therefore, we are only able to present estimates of these values.

Most pesticide formulations contain both “chief” and “additive” ingredients. Chief ingredients are used to target pests, and their efficacy is enhanced by the presence of the additive ingredients. Ingestion of a pesticide results in exposure to all of its ingredients. The additives may not have been tested as thoroughly as the chief ingredients, and are seldom disclosed on product labels. For this reason, physicians may need to be aware of the effects of additive ingredients.

After investigating the validamycin formulation ingested by our patient, we discovered that it contained a number of additives, including an emulsifier, a stabilizer, a coloring agent, a pH regulator, an antifoaming agent, and supplements (Table 1). We hypothesized that the symptoms observed in this patient were caused by one or more of these additives. To test this hypothesis, we studied the clinical features of the patient and performed In vitro experiments to analyze the cytotoxicity of each chemical in the formulation.

METHODS

Case study

A female patient aged 72 years was admitted to hospital in a critical condition within 1 hour of ingesting 200 mL of a validamycin formulation. Upon admission, she had shallow respiration and her O2 saturation was < 70%. After receiving first aid and undergoing tracheal intubation, the patient was transferred to the Pesticide Intoxication Institute at Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital.

When we first examined the patient, she was in a semi-coma state, with a blood pressure of 100/70 mmHg and a pulse rate of 76 beats per minute. Arterial blood gas analysis showed hypoxia, with a high anion gap [Na+ – (HCO3– + Cl–) = 32.4] metabolic acidosis (pH = 7.13).

Metabolic acidosis was corrected after a single session of hemodialysis. Lipid emulsion product (20%) was injected intravenously, using 500 mL over 2 hours as the loading dose, followed by a maintenance dose of 1,000 mL over the next 24 hours. The patient’s mental status improved, although she remained drowsy. We were able to remove her tracheal tube on her third hospital day, and she began taking a liquid diet on the following day. The patient was transferred to the general ward on her 7th hospital day and discharged on the 18th day, with no signs of any specific health abnormalities.

In vitro cytotoxicity studies

We explored the effects of the following ingredients of the validamycin formulation, as stated by its manufacturer: validamycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40, Sigma), methanol (Sigma-Aldrich), potassium hydroxide (KOH, Junsei Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan), sorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), acid yellow (yellow 17, Sigma-Aldrich), sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich), silicones (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), and siloxanes (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.).

Cell culture

We purchased the human neuroblastoma cell line, SKN-SH, from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). Cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640) medium (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). They were expanded in a humidified CO2 incubator (5%) at 37°C in T-75 flasks after trypsinization and subsequent washing in phosphate-buffered saline.

Cytotoxicity assays

Two types of assay were carried out to investigate the effects of each formulation ingredient on SK-N-SH cells. The MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Sigma-Aldrich) assay measured reduction of MTT to its purple tetrazolium salt by metabolically active cells. The intensity of this color (measured at 595 nm) was proportional to the number of metabolically active cells in each well. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay measured release of LDH (a stable cytoplasmic enzyme) from compromised cells with membrane damage. LDH reduces pyruvate to lactate by oxidizing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) to NAD+ and spectrophotometric measurement of NADH consumption provided an indication of the amount of LDH released.

Prior to each cytotoxicity assay, a stock concentration of each formulation ingredient was prepared in an appropriate vehicle. SK-N-SH cells (100 µL) were seeded into 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells/well, and incubated for 24 hours. When cells reached 70% to 80% confluence, 100 µL of the test chemicals (freshly prepared in RPMI media) were added into the wells at concentrations of 0.01 µM to 1 mM, and incubated for a further 24 hours at 37°C. The total volume of vehicle added to the cell culture plates was always ≤ 1.0% of the media volume, to minimize vehicle effects on the cells.

MTT assays were then performed using the method previously described by Mickisch et al. [4]. Briefly, the cells were treated with 100 µL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution and incubated for an additional 2 hours at 37°C. The MTT solution was then removed and 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well to dissolve the formazan. The absorbance was then measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

LDH release was measured at 490 nm using an ELISA reader, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA). The resulting value was expressed relative to the absorbance determined in cells exposed to 1% Triton X-100 (control).

Gene expression study

MTT and LDH assays indicated that NP40 had the greatest effect on SK-N-SH cell viability. To investigate the dominant pathway of NP40-mediated cytotoxicity, the expression levels of 80 genes responsible for human stress and toxicity pathways were quantified (Table 2). These gene products were involved in the following nine categories of cell damage pathways: oxidative/metabolic stress, hypoxia, cell death (comprising three subgroups relating to apoptosis signaling, autophagy signaling, and necrosis signaling), inflammatory response, DNA damage signaling (comprising two subgroups relating to cell cycle checkpoint/arrest and other responses), and heat shock proteins/unfolded protein response (Table 2).

Table 2.

Gene name and fold change in expression in nine categories of cell damage pathways after NP40 exposure

| GeneBank accession no. | Gene name | Symbol | Fold change |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP40 | p valuea | |||

| Oxidative/metabolic stress | ||||

| NM_003329 | Thioredoxin | TXN | –1.23 | 0.008b |

| NM_001498 | Glutamate-cysteine ligase, catalytic subunit | GCLC | –1.32 | 0.045b |

| NM_002061 | Glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit | GCLM | 4.02b | 0.048b |

| NM_000637 | Glutathione reductase | GSR | 1.30b | 0.689 |

| NM_000852 | Glutathione S-transferase pi 1 | GSTP1 | –4.24 | 0.389 |

| NM_002133 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | HMOX1 | 1.60b | 0.024b |

| NM_000903 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 | NQO1 | 1.99b | 0.016b |

| NM_002574 | Peroxiredoxin 1 | PRDX1 | –1.83 | 0.095 |

| NM_003330 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | TXNRD1 | 1.84b | 0.033b |

| NM_003900 | Sequestosome 1 | SQSTM1 | –2.44 | 0.045b |

| NM_002032 | Ferritin, heavy polypeptide 1 | FTH1 | 8.78b | 0.084 |

| Hypoxia | ||||

| NM_003376 | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | VEGFA | –6.09 | 0.009b |

| NM_001668 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator | ARNT | –2.86 | 0.022b |

| NM_004331 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3-like | BNIP3L | 1.18b | 0.046b |

| NM_001216 | Carbonic anhydrase IX | CA9 | –2.82 | 0.037b |

| NM_000799 | Erythropoietin | EPO | –2.75 | 0.017b |

| NM_002133 | Hemeoxygenase (decycling) 1 | HMOX1 | 1.60b | 0.024b |

| NM_005566 | Lactate dehydrogenase A | LDHA | –1.38 | 0.042b |

| NM_004994 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (gelatinase B, 92 kDa gelatinase, 92 kDa type IV collagenase) | MMP9 (Gelatinase B) | –1.25 | 0.048b |

| NM_000602 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 1 | SERPINE1 (PAI-1) | –7.17 | 0.000b |

| NM_006516 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 1 | SLC2A1 | 1.87b | 0.020b |

| NM_001124 | Adrenomedullin | ADM | –5.24 | 0.080 |

| Cell death (apoptosis signaling) | ||||

| NM_003842 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10b | TNFRSF10B (DR5) | 8.93b | 0.037b |

| NM_001065 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1A | TNFRSF1A | –1.17 | 0.044b |

| NM_021960 | Myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (BCL2-related) | MCL1 | 1.87 | 0.004b |

| NM_003844 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10a | TNFRSF10A | –2.90 | 0.038b |

| NM_033292 | Caspase 1, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase (interleukin 1, β, convertase) | CASP1 (ICE) | –1.72 | 0.022b |

| NM_000043 | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) | FAS | –15.12 | 0.081 |

| Cell death (autophagy signaling) | ||||

| NM_004849 | ATG5 autophagy related 5 homolog (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | ATG5 | –1.22 | 0.019b |

| NM_006395 | ATG7 autophagy related 7 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | ATG7 | –4.97 | 0.039b |

| NM_004707 | ATG12 autophagy related 12 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | ATG12 | 2.59b | 0.017b |

| NM_003766 | Beclin 1, autophagy related | BECN1 | 1.48b | 0.029b |

| NM_000043 | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) | FAS | –15.12 | 0.081 |

| NM_003565 | Unc-51-like kinase 1 (Caenorhabditis elegans) | ULK1 | –6.74 | 0.018b |

| Cell death (necrosis signaling) | ||||

| NM_017853 | Thioredoxin-like 4B | TXNL4B | 7.67b | 0.071 |

| NM_002086 | Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 | GRB2 | –1.99 | 0.029b |

| NM_001618 | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 | PARP1 (ADPRT1) | –1.56 | 0.025b |

| NM_006505 | Poliovirus receptor | PVR | 1.57b | 0.098 |

| NM_003804 | Receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | RIPK1 | 13.86b | 0.096 |

| NM_003844 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10a | TNFRSF10A | –2.90 | 0.038b |

| NM_003842 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1A | TNFRSF1A | –1.17 | 0.044b |

| NM_000043 | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) | FAS (TNFRSF6) | –15.12 | 0.081 |

| Inflammatory response | ||||

| NM_002982 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | CCL2 (MCP-1) | 8.16b | 0.037b |

| NM_000594 | Tumor necrosis factor | TNF | –11.48 | 0.079 |

| NM_000567 | C-reactive protein, pentraxin-related | CRP | 2.43b | 0.015b |

| NM_000619 | Interferon, γ | IFNG | –1.45 | 0.015b |

| NM_000575 | Interleukin 1, α | IL1A | –2.36 | 0.046b |

| NM_000600 | Interleukin 6 (interferon, β2) | IL-6 | 8.95b | 0.032b |

| NM_000584 | Interleukin 8 | IL-8 | –2.03 | 0.080b |

| NM_138554 | Toll-like receptor 4 | TLR4 | –4.55 | 0.017b |

| NM_000074 | CD40 ligand | CD40LG (TNFSF5) | 2.84b | 0.201 |

| DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) | ||||

| NM_004507 | HUS1 checkpoint homolog (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) | HUS1 | 3.30b | 0.012b |

| NM_001274 | CHK1 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) | CHEK1 | 4.36b | 0.076 |

| NM_007194 | CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) | CHEK2 (RAD53) | 3.15b | 0.000b |

| NM_004083 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | DDIT3 (GADD153/ CHOP) | 2.90b | 0.038b |

| NM_002873 | RAD17 homolog (S. pombe) | RAD17 | 1.78b | 0.012b |

| NM_004584 | RAD9 homolog A (S. pombe) | RAD9A | 1.44b | 0.029b |

| NM_000389 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) | CDKN1A (p21CIP-1WAF1) | 2.33b | 0.027b |

| NM_005590 | MRE11 meiotic recombination 11 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) | MRE11A | 1.99b | 0.019b |

| NM_002485 | Nibrin | NBN (NBS1) | 2.45b | 0.011b |

| DNA damage signaling (other responses) | ||||

| NM_000051 | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated | ATM | –9.50 | 0.061 |

| NM_001184 | Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related | ATR | –7.18 | 0.015b |

| NM_000107 | Damage-specific DNA binding protein 2, 48 kDa | DDB2 | –2.86 | 0.036b |

| NM_000546 | Tumor protein p53 | TP53 | –3.52 | 0.006b |

| NM_002875 | RAD51 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | RAD51 | –11.56 | 0.038b |

| NM_001924 | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, α | GADD45A | 1.05b | 0.026b |

| NM_004628 | Xerodermapigmentosum, complementation group C | XPC | –1.04 | 0.023b |

| Heatshock proteins/unfolded protein response | ||||

| NM_001675 | Activating transcription factor 4 (tax-responsive enhancer element B67) | ATF4 | 3.71b | 0.019b |

| NM_007348 | Activating transcription factor 6 | ATF6 | 1.72b | 0.018b |

| NM_004381 | Activating transcription factor 6 β | ATF6B | 2.15b | 0.029b |

| NM_014417 | BCL2 binding component 3 | BBC3 | 1.09b | 0.041b |

| NM_001196 | BH3 interacting domain death agonist | BID | 2.32b | 0.050b |

| NM_006260 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 3 | DNAJC3 | 2.73b | 0.013b |

| NM_004083 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | DDIT3 | –2.90 | 0.007b |

| NM_004343 | Calreticulin | CALR | –1.08 | 0.040b |

| NM_001017963 | Heat shock protein 90 kDa α (cytosolic), class A member 1 | HSP90AA1 | 1.15b | 0.048b |

| NM_003299 | Heat shock protein 90 kDa β (Grp94), member 1 | HSP90B1 (TRA1) | –5.85 | 0.096 |

| NM_002154 | Heat shock 70kDa protein 4 | HSPA4 (HSP70) | 26.10b | 0.049b |

| NM_005347 | Heat shock 70kDa protein 5 (glucose-regulated protein, 78kDa) | HSPA5 (GRP78) | –2.31 | 0.023b |

| NM_014278 | Heat shock 70kDa protein 4-like | HSPA4L | 3.00b | 0.015b |

NP40, nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; BCL2, B cell lymphoma 2; TNFRSF, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; ATG, autophagy protein; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; CHK, checkpoint kinase.

The p values are calculated based on a Student t test of the replicate 2^ (- Delta Ct) values for each gene in the control group and treatment groups.

p values less than 0.05.

Total RNA was isolated from SK-N-SH cells exposed to 0.001 µM NP40 or vehicle for 24 hours, using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized using the Maxime RT premix kit (Intron, Seongnam, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was quantified using the RT2 Profile PCR Array (Cat. no. PAHS-003ZD-12; QIAGEN). SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA) was added, and the arrays were run on a CFX96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using cycling programs recommended by the manufacturer. Relative gene expression levels were determined using the data analyzer template provided by QIAGEN (http://pcrdataanalysis.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php) using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, β-actin, and ribosomal protein L13a as reference genes. The non-stimulated condition was set to 1. The results were expressed as the fold-change (2^ [- delta delta Ct]) in normalized gene expression (2^ [- delta Ct]) in the test sample, as compared with the normalized gene expression (2^ [- delta Ct]) in the control sample. Fold-change values greater than one indicated up-regulation, and fold-change values less than one indicated down-regulation.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We performed three replicates of each in vitro experiment for cytotoxicity testing on three independent occasions. Inhibitory concentration (IC)50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), as appropriate. The results of the MTT and LDH assays were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey multiple comparison tests.

Student t test was used to compare the replicate (delta delta Ct) values for each gene expression level in the control group, versus those of the treatment groups (Table 3). Changes in gene expression in the nine key pathways were analyzed using Fisher exact test (Table 2). Comparison of the fold change of gene expression in these nine pathways was analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 3.

Gene expression changes in the nine key categories of human stress and toxicity pathways

| Category of the pathway | Gene expression |

|

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulation | Down-regulation | |

| Cell death (apoptosis signaling) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Cell death (autophagy signaling) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Cell death (necrosis signaling) | 0 | 4 (100.0) |

| DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) | 8 (100.0) | 0 |

| DNA damage signaling (other responses) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) |

| Heat shock proteins/infolded protein response | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Hypoxia | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) |

| Inflammatory response | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Oxidative/metabolic stress | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) |

Values are presented as number (%). p = 0.005 by Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

MTT assay

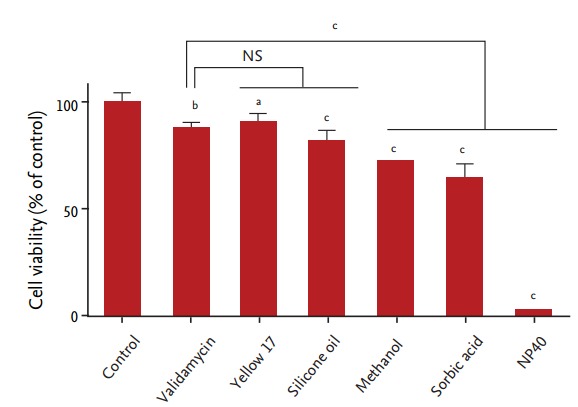

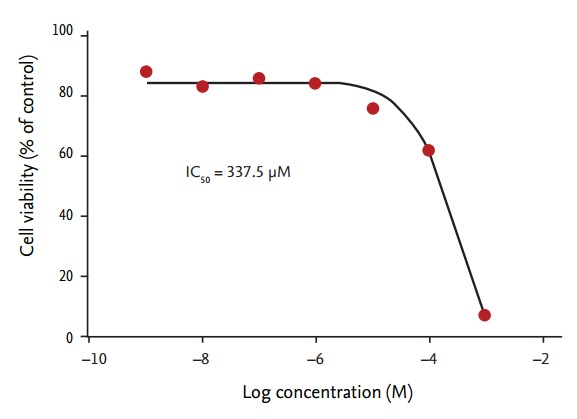

SK-N-SH cell viability decreased in a dose-dependent manner following exposure to all the chemicals tested (p < 0.01 for all, compared with vehicle control) (Fig. 1). After exposure to 1 mM validamycin, silicon oil, methanol, and sorbic acid, SK-N-SH cell viability was > 60% of that observed in control cells. Yellow 17 showed the least cytotoxicity, with 91.2% ± 4.3% cell viability following exposure to 1 mM of this coloring agent for 24 hours. In contrast, only 3.3% ± 0.2% cells were viable after incubation for 24 hours with 1 mM NP40 (IC50 = 337.5 µM) (Figs. 1 and 2). Based on these data, we divided the chemicals into three toxicity categories: slightly toxic (80% to 100% viability; validamycin, yellow 17, and silicon oil); moderately toxic (60% to 80% viability; methanol and sorbic acid); and severely toxic (< 10% viability; NP40).

Figure 1.

Cell viability following chemical exposure. Human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells were exposed to 1 mM of nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40). Cell viability was significantly reduced following exposure to all of the chemicals tested, as compared with the control group (n = 8 for each data point). NS, not significant. ap < 0.01. bp < 0.001. cp < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Cell viability following exposure to nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40). Human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of NP40, from 1 nM to 1 mM. Cell viability was measured using MTT assays. The inhibitory concentration (IC)50 was 337.5 μM (n = 6 for each data point).

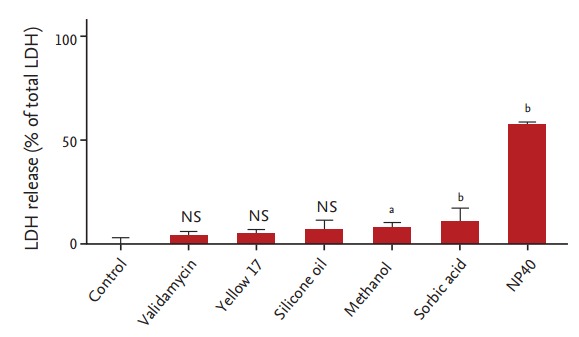

LDH assay

Validamycin, sorbic acid, and silicone oil did not cause any significant elevation of LDH release from SK-N-SH cells (p > 0.05), while methanol and sorbic acid caused only small amounts of LDH release (7.5% ± 2.6% and 10% ± 7.4%, respectively), even at a high concentration (1 mM). In contrast, and consistent with the MTT assay data, NP40 was moderately to severely cytotoxic (57.2% ± 1.5% LDH release) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release following chemical exposure. Human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells were exposed to the indicated chemicals for 24 hours prior to analysis of LDH release. One-way analysis of variance identified significant differences between cells treated with different chamicals (p < 0.0001). Validamycin, yellow 17, and silicone oil had negligible effects on LDH release from SKN- SH cells, as compared to the control treatment (p > 0.05). Exposure of these cells to methanol and sorbic acid caused some LDH release (7.5% ± 2.6% and 10% ± 7.4%, respectively), indicating some cytotoxicity, while nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40) had moderate to high cytotoxicity (57.2% ± 1.5%) (n = 7 for each data point). NS, not significant. ap < 0.001. bp < 0.0001.

Pathway-related gene expression following NP40 treatment

Sixty-three out of 80 genes showed significant expression changes, based on Student t tests of the replicate (delta delta Ct) values for each gene in the control and treatment groups (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The expression changes were varied, with some up-regulated and others down-regulated within the same pathway (Table 2). However, genes in the cell death (necrosis signaling) pathway and DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) pathways were the most noticeably affected, with down-regulated of all genes tested in the cell death (necrosis signaling) pathway and up-regulation of all genes tested in the DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) pathway (Table 2).

The mean fold-change in gene expression was 2.42 (SD, 0.67; range, 1.44 to 3.30) within the cell cycle checkpoint/arrest pathways, and –1.91 (SD, –0.74; range, –1.17 to –2.90) within the cell death (necrosis signaling) pathway (Table 2). The median fold change in gene expression was significantly higher in the DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) pathway than in the hypoxia pathway (p = 0.0064) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the fold change of gene expression in the nine categories of human stress and toxicity pathways

| Category of the pathway | No. | Median (interquartile range) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell death (apoptosis signaling) | 5 | –1.17 (–1.72 to 1.87) |

| Cell death (autophagy signaling) | 5 | –1.22 (–4.97 to 1.48) |

| Cell death (necrosis signaling) | 4 | –1.77 (–2.44 to –1.36) |

| DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) | 8 | 2.39a (1.89 to 3.02) |

| DNA damage signaling (other responses) | 6 | –3.19 (–7.18 to –1.04) |

| Heat shock proteins/unfolded protein response | 12 | 1.93 (0.01 to 2.87) |

| Hypoxia | 10 | –2.06a (– 2.86 to 1.18) |

| Inflammatory response | 6 | 0.49 (–2.36 to 8.16) |

| Oxidative/metabolic stress | 7 | 1.60 (–1.32 to 1.99) |

p = 0.0064 by Kruskal-Wallis test.

Same letters indicate statistical significance based on the Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner multiple comparison method.

The 70 kDa heat shock protein 4 gene (within the heat shock protein/unfolded protein response category) showed the highest individual increase in expression (26.1-fold) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the effects of the ingredients of a validamycin formulation on the human neuroblastoma cell line, SK-N-SH. NP40, a surfactant that acts as an emulsifier, produced the most cytotoxic effects. This finding was consistent with those of previous studies [5-7].

We have previously performed a number of studies investigating the roles of surfactants in pesticide intoxication [8-12]. These have revealed that surfactants negatively impact cells in a variety of ways, including breaking down the cell membrane, altering metabolic and mitochondrial activity, disrupting total protein synthesis [12], and facilitating mitochondrial damage-induced apoptosis and necrosis [9]. Based on our clinical experience, neurologic abnormalities such as unconsciousness and apnea are frequently observed clinical manifestations in patients with surfactant intoxication. For this reason, we choose a human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell line for the present study.

To identify the dominant pathway involved in NP40-mediated cytotoxicity, we investigated the expression of 80 genes involved in human stress and toxicity pathways. The effects of NP40 on gene expression varied greatly and we identified up- and down-regulation of genes within several pathways (Table 2). These findings suggested that intracellular signaling changes resulting from NP40 exposure were complex. The range of changes observed may result from components of the pathways affecting each other, or could reflect cross-talk between pathways [13,14].

However, the DNA damage signaling (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) pathway was the most noticeably affected, with up-regulation of all genes. The genes in this category were HUS1, CHEK2 (RAD53), DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT3) (GADD153/CHOP), RAD17, RAD9A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) (CDKN1A [p21CIP1WAF1]), MRE11 meiotic recombination 11 homolog A (MRE11A), and nibrin (NBN [NBS1]) (Table 3). The main function of the proteins encoded by these genes is to maintain genomic stability and conserve DNA integrity. The repair of damaged DNA is coupled to the completion of DNA replication by several cell cycle checkpoint proteins, including HUS1, RAD9A, and RAD17 [15,16]. CHEK2 is a protein kinase that is activated in response to DNA damage and may regulate cell cycle arrest. Hirao et al. [17] demonstrated that CHEK2–/–embryonic stem cells failed to maintain γ irradiation-induced G2 arrest.

Similarly, the other genes in this category, including DDIT3 (GADD153/CHOP) [18], CDKN1A (p21CIP1WAF1) [19], MRE11A [20], and NBN (NBS1) [21], are strongly activated in response to genotoxin-induced DNA damage. Taken together, our results suggested that NP40 acted as a potent genotoxin and activated DNA damage signaling within the cell cycle checkpoint/arrest pathway.

In contrast, expression of growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2), poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1 [ADPRT1]), tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10a (TNFRSF10A), and tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1A (TNFRSF1A) within the cell death (necrosis signaling) pathway was down-regulated when SK-N-SH cells were exposed to NP40 (Table 2). GRB2-associated binders are scaffolding proteins implicated in cell signaling via receptor tyrosine kinases. Inhibition of GRB2 function blocks transformation and proliferation of various cell types and targeted gene disruption of GRB2 is lethal at an early embryonic stage in mice [22]. PARP1 protects cells from genomic instability and is involved in the inflammatory response and in several forms of cell death [23]. TNFRSF10A [24] and TNFRSF1A [25] belong to the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) super family. These receptors appear to transmit their signals via protein-protein interactions, which convey either a death or survival signal.

The 70 kDa heat shock protein 4 gene, within the heat shock protein/unfolded protein response category, showed the highest individual increase in expression (26.1-fold) (Table 2). In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that various stressors transiently increase production of heat shock proteins as a protection against harmful insults, such as environmental stresses and infection [26].

A thorough discussion of treatment modality is beyond the scope of this paper. However, we would like to briefly address our administration of an intravenous lipid emulsion to this patient. The predominant theoretical basis for the use of lipid emulsions proposes that the creation of an expanded intravascular lipid phase drives toxic lipophilic drugs from the target tissues into this “lipid sink” [27]. Typically, surfactants are amphiphilic organic compounds, meaning that they contain both a hydrophobic group and a hydrophilic group [28]. They will diffuse in water and adsorb at the lipid-water interface when water is mixed with a lipid. Therefore, we believe that a circulating lipid emulsion probably alters surfactant kinetics and biological effects.

Our study had some limitations. First, we were unable to calculate how much of each chemical would have been absorbed after the herbicide was ingested, due to the lack of pharmacokinetic data. Second, it is impossible to precisely model the patient’s physiologic state in vitro. Even with this limitation, we demonstrated that ingredients previously considered to be inert had greater toxicity towards SK-N-SH cells than the chief ingredient in this validamycin formulation.

In conclusion, NP40 appeared to be particularly harmful, inducing gene expression changes that indicated genotoxic effects and activation of the cell death (necrosis signaling) pathway.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The surfactant, nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40) was the most cytotoxic chemical present in a validamycin pesticide formulation.

2. NP40 altered gene expression in various cell damage pathways, in particular the cell death (necrosis signaling) and DNA damage (cell cycle checkpoint/arrest) pathways.

3. Intravenous lipid emulsion administration may attenuate toxic symptoms in patients with NP40 intoxication.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project title: A study for improvement of treatment modality in patients with acute pesticide additives intoxication, Project No. PJ01083201)” Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Konradsen F, van der Hoek W, Cole DC, et al. Reducing acute poisoning in developing countries: options for restricting the availability of pesticides. Toxicology. 2003;192:249–261. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suami T, Ogawa S, Chida N. The revised structure of validamycin A. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980;33:98–99. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qian H, Hu B, Cao D, Chen W, Xu X, Lu Y. Bio-safety assessment of validamycin formulation on bacterial and fungal biomass in soil monitored by real-time PCR. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2007;78:239–244. doi: 10.1007/s00128-007-9148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mickisch G, Fajta S, Keilhauer G, Schlick E, Tschada R, Alken P. Chemosensitivity testing of primary human renal cell carcinoma by a tetrazolium based microculture assay (MTT) Urol Res. 1990;18:131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00302474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghirardini AV, Novelli AA, Likar B, Pojana G, Ghetti PF, Marcomini A. Sperm cell toxicity test using sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus lamarck (Echinodermata: Echinoidea): sensitivity and discriminatory ability toward anionic and nonionic surfactants. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2001;20:644–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galembeck E, Alonso A, Meirelles NC. Effects of polyoxyethylene chain length on erythrocyte hemolysis induced by poly[oxyethylene (n) nonylphenol] non-ionic surfactants. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;113:91–103. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(98)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin WS, Graham SE, Shea D, LeBlanc GA. Altered metabolic elimination of testosterone and associated toxicity following exposure of Daphnia magna to nonylphenol polyethoxylate. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1998;39:104–111. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1997.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seok SJ, Park JS, Hong JR, et al. Surfactant volume is an essential element in human toxicity in acute glyphosate herbicide intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49:892–899. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.626422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YH, Hong JR, Gil HW, Song HY, Hong SY. Mixtures of glyphosate and surfactant TN20 accelerate cell death via mitochondrial damage-induced apoptosis and necrosis. Toxicol In vitro. 2013;27:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song HY, Kim YH, Seok SJ, Gil HW, Hong SY. In vitro cytotoxic effect of glyphosate mixture containing surfactants. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:711–715. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.7.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil HW, Park JS, Park SH, Hong SY. Effect of intravenous lipid emulsion in patients with acute glyphosate intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013;51:767–771. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.821129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song HY, Kim YH, Seok SJ, et al. Cellular toxicity of surfactants used as herbicide additives. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:3–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulda S. Cross talk between cell death regulation and metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 2014;542:81–90. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416618-9.00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowland MA, Deeds EJ. Crosstalk and the evolution of specificity in two-component signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5550–5555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317178111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venclovas C, Thelen MP. Structure-based predictions of Rad1, Rad9, Hus1 and Rad17 participation in sliding clamp and clamp-loading complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2481–2493. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai RL, Yan-Neale Y, Cueto MA, Xu H, Cohen D. HDAC1, a histone deacetylase, forms a complex with Hus1 and Rad9, two G2/M checkpoint Rad proteins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27909–27916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirao A, Kong YY, Matsuoka S, et al. DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science. 2000;287:1824–1827. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luethy JD, Fargnoli J, Park JS, Fornace AJ, Jr, Holbrook NJ. Isolation and characterization of the hamster gadd153 gene: activation of promoter activity by agents that damage DNA. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16521–16526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagger G, Doetzlhofer A, Schuettengruber B, et al. The tumor suppressor p53 and histone deacetylase 1 are antagonistic regulators of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21/WAF1/CIP1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2669–2679. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2669-2679.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams GJ, Lees-Miller SP, Tainer JA. Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 conformations and the control of sensing, signaling, and effector responses at DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan Z, Seto E. A functional link between SIRT1 deacetylase and NBS1 in DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2869–2871. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.23.5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thumkeo D, Keel J, Ishizaki T, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse rho-associated kinase 2 gene results in intrauterine growth retardation and fetal death. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5043–5055. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.5043-5055.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosado MM, Bennici E, Novelli F, Pioli C. Beyond DNA repair, the immunological role of PARP-1 and its siblings. Immunology. 2013;139:428–437. doi: 10.1111/imm.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Workman LM, Habelhah H. TNFR1 signaling kinetics: spatiotemporal control of three phases of IKK activation by posttranslational modification. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1654–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiang JG, Tsokos GC. Heat shock protein 70 kDa: molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;80:183–201. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberg GL. Lipid resuscitation: more than a sink. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2521–2523. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318258e930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams GM, Kroes R, Munro IC. Safety evaluation and risk assessment of the herbicide Roundup and its active ingredient, glyphosate, for humans. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000;31(2 Pt 1):117–165. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1999.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]