Abstract

Arsenic exposure has been reported to cause neoplastic transformation through the activation of PcG proteins. In the present study, we show that activation of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is required for arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation. Exposure of cells to 0.5 µM arsenic increased CRE and c-Fos promoter activities that were accompanied by increases in p38α MAPK and CREB phosphorylation and expression levels concurrently with AP-1 activation. Introduction of short hairpin (sh) RNA-p38α into BALB/c 3T3 cells markedly suppressed arsenic-induced colony formation compared with wildtype cells. CREB phosphorylation and AP-1 activation were decreased in p38α knockdown cells after arsenic treatment. Arsenic-induced AP-1 activation, measured as c-Fos and CRE promoter activities, and CREB phosphorylation were attenuated by p38 inhibition in BALB/c 3T3 cells. Thus, p38α MAPK activation is required for arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation mediated through CREB phosphorylation and AP-1 activation.

Keywords: arsenic, cell transformation, p38α, AP-1, CREB

INTRODUCTION

Arsenic is a widespread and well-known human carcinogen. Chronic arsenic exposure is associated with skin, lung, bladder, liver, kidney and prostate cancers [1,2]. Accumulating evidence implicates chronic exposure to arsenic with the malignant transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells [3], human HaCaT keratinocytes [4,5], human lung epithelial BEAS-2B cells [6], human small airway epithelial cells [7], rat liver epithelial TRL1215 cells [8], and human prostate epithelial RWPE-1 cells with estrogen-induced epigenetic changes [9]. Even though chronic exposure to arsenic is known to be involved in carcinogenesis, the mechanism explaining the exact relationship of chronic arsenic exposure and tumor development is unclear.

The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family regulates various cellular stresses and inflammation. Many reports have suggested that p38 MAPK is an important regulator in bladder [10], prostate [11], liver [12] and lung [13] cancers. Overexpression or overactivation of p38 MAPK plays an important role in thyroid neoplasms [14] and transformed follicular lymphomas [15]. However, p38 MAPK also plays an inhibitory role in Ras-induced neoplastic transformation of cells [16], hepatocellular carcinoma [17] and human ovarian cancer metastatic colonization [18]. In addition, p38 MAPK specifically modulates malignant transformation induced by oncogenes that produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) [19]. It also stimulates migration in melanoma [20] and promotes the invasive and proliferative phenotype of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [21]. Although p38 MAPK exhibits some antitumor activities, it is also associated with cellular neoplastic transformation that is dependent on cancer stage or tumor type. However, the relationship between p38 MAPK and arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation is not clear.

In a previous study, we reported that polycomb (PcG) proteins, including BMI1 and SUZ12, were required for arsenic-induced cell transformation through the inhibition of tumor suppressor expression [22]. We sought to determine if p38α MAPK is involved in arsenic-induced fibroblast transformation and found that p38α MAPK plays a role in fibroblast proliferation induced by 0.5 µM arsenic possibly through AP-1 activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

Chemical reagents, including arsenic trioxide (As2O3) and basal medium eagle (BME) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Calf serum (CS) was from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY). The prestained protein marker and protease inhibitor cocktail were from GenDEPOT (Barker, TX). Antibodies against phospho-p38 MAPK, total p38α MAPK, phospho-MSK1, total MSK1, phospho-CREB, total CREB, phospho-ATF2 and total ATF2 were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA).

Cell culture and establishment of p38α-knockdown stable cells

Wildtype BALB/c 3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were from ATCC® (Manassas, VA). BALB/c 3T3 cells are an immortalized transformed fibroblast cell line, which have not undergone neoplastic transformation. Cells stably expressing knockdown p38α MAPK were grown in 10% CS/DMEM supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/mL; Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. To construct arsenic-induced transformed BALB/c 3T3 cells, As2O3 (0.5 µM in 0.1 M NaHCO3) or 0.1 M NaHCO3 only as a control was used to treat cells every two days with media change over 2 or 4 weeks. No additional arsenic was included in subsequent assays to assess neoplastic transformation or protein expression. To construct knockdown of p38α in BALB/c 3T3 cells, the shRNA-p38α (sh-p38α) or shRNA-GFP (sh-GFP) control vector (RNAi Core Facility, BioMedical Genomic Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) based on the pLKO.1 lentiviral vector, were infected into BALB/c 3T3 cells following the recommended protocols. Infected cells were selected in medium containing 2 µg/mL puromycin and the expression level of the p38α MAPK protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Analysis of protein phosphorylation profiles

To determine the effect of arsenic on protein phosphorylation, we analyzed phosphorylated proteins in untreated or arsenic-treated BALB/c 3T3 cell lysates using the Proteome Profiler™ Array/Human Phospho-Kinase Array Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Anchorage-independent colony formation assay

In brief, cells (8 × 103/mL) were cultured in 1 mL of 0.3% Basal Medium Eagle (BME) agar containing 10% CS. The cultures were maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 7 days and cell colonies were scored using a microscope and the Image-Pro PLUS (v.6) computer software program (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

Reporter gene assays

For reporter gene assays, transient transfections were conducted using jetPEI (QBIOgene, Irvine, CA) and cells were co-transfected with 200 ng of the AP1-, c-Fos- or CRE-reporter plasmid and 50 ng of a β-galactosidase (β-Gal)-expressing plasmid in arsenic-induced transformed or wildtype cells without arsenic treatment. The β-Gal-expressing plasmid was co-transfected for normalizing the transfection efficiency. Routinely, at 36 h after transfection, cells were washed and then cell lysates were prepared. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using the Luminoskan Ascent (Thermo Electron Corp., Marietta, OH) and Multiskan MCC (Thermo Electron Corp.), respectively.

RESULTS

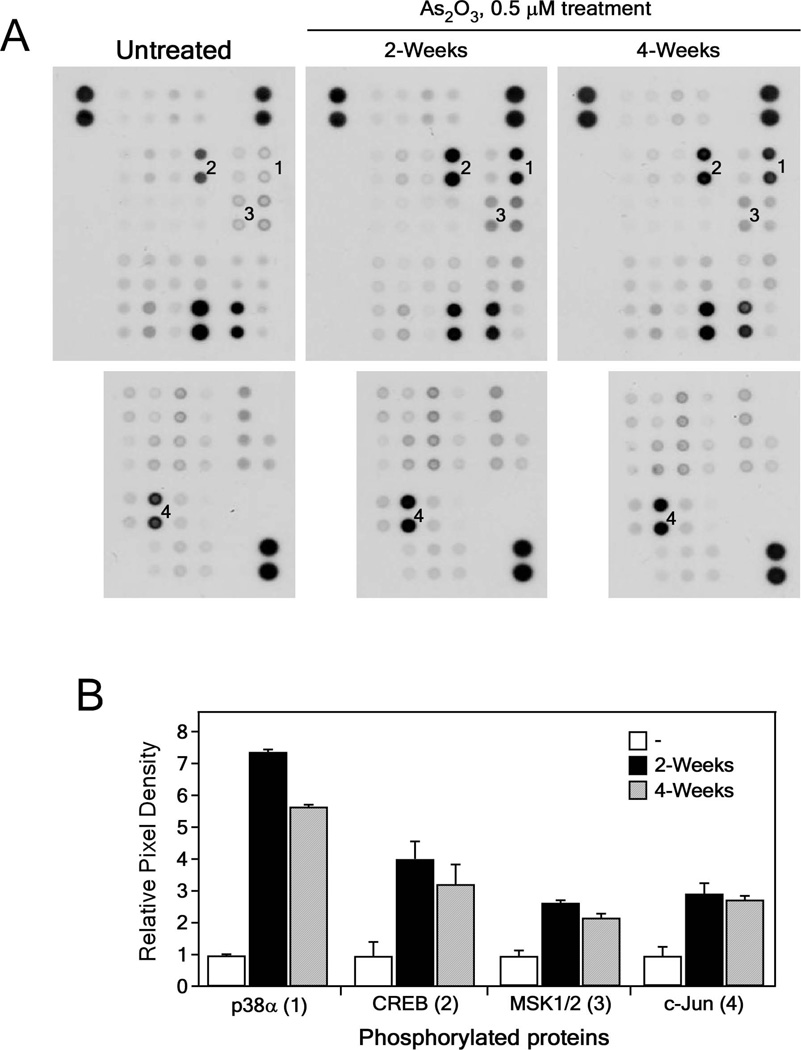

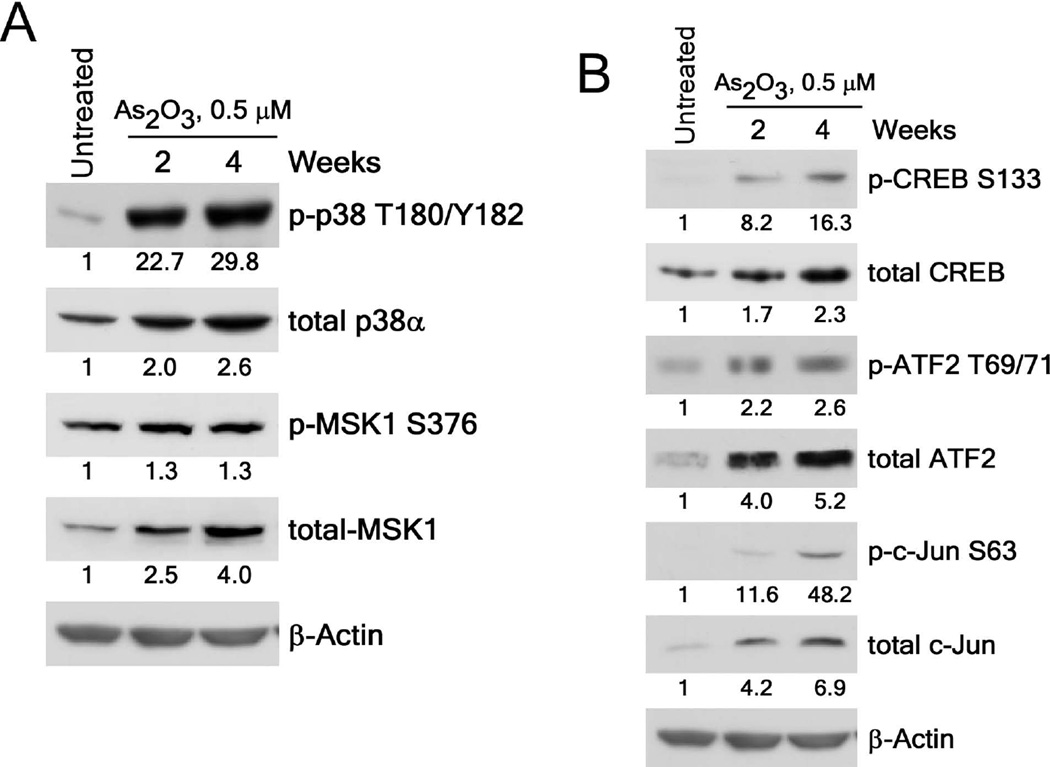

Arsenic activates p38α MAPK signaling

We previously reported that exposure to arsenic caused neoplastic transformation of BALB/c 3T3 cells and these transformed cells could form tumors in nude mice [22]. To begin to determine a mechanism of arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation, we used a phospho-kinase assay to examine the phosphorylated proteins from BALB/c 3T3 cells treated or not treated with 0.5 µM As2O3 for 2 or 4 weeks. We found that 0.5 µM exposure to arsenic significantly increased the phosphorylation of p38α MAPK, CREB, MSK1/2 and c-Jun proteins (Fig 1A, B). To determine which p38 MAPK isoforms were involved in arsenic-induced transformation, we detected p38α (Fig. 1), p38β, p38γ and p38δ (Fig. S1) isoform expression in BALB/c 3T3 cells treated or not treated with arsenic and found that only p38α MAPK was expressed. We then examined the phosphorylation and expression levels of p38α MAPK and confirmed that levels were increased up to almost 30-fold in arsenic treated BALB/c 3T3 cells (Figure 2A). In addition, the phosphorylation and expression levels of the transcription factors, CREB, c-Jun, and ATF2, were increased from about 2-fold up to 48-fold (Figure 2B). These findings demonstrated that the activation of p38α MAPK signaling is involved in arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation.

Figure 1.

Analysis of phosphorylated protein profiles in arsenic-treated BALB/c 3T3 cells. (A) Phospho-kinase array results for detection of phosphorylated proteins in untreated and arsenic (As2O3, 0.5 µM in 0.1 M NaHCO3)-treated BALB/c 3T3 cell lysates. BALB/c 3T3 cells were treated with arsenic for 2 or 4 weeks and then harvested for analysis of changes in the levels of phosphorylated proteins. Numbers on the blot correspond with changes in phosphorylated p38α (1, at T180/Y182); CREB (2, at S133); MSK1/2 (3, at S376/S360); and c-Jun (4, at S63). (B) Summary of changes in phosphorylated protein levels from untreated or arsenic-treated BALB/c 3T3 cell lysates. Data are represented as means ± S.D. of values obtained from duplicate spots on the membrane.

Figure 2.

Arsenic exposure activates the p38α-signaling cascade in BALB/c 3T3 cells. (A) Phosphorylation and expression of p38α are increased in arsenic-treated BALB/c 3T3 cells. (B) Arsenic increases the phosphorylation and expression levels of the CREB, ATF2 and c-Jun transcription factors in BALB/c 3T3 cell lysates. Numbering indicates the fold increase compared to untreated control as 1. Cellular proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and the protein levels were visualized by Western blotting with specific primary antibodies and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection of total β-actin was used to verify equal protein loading.

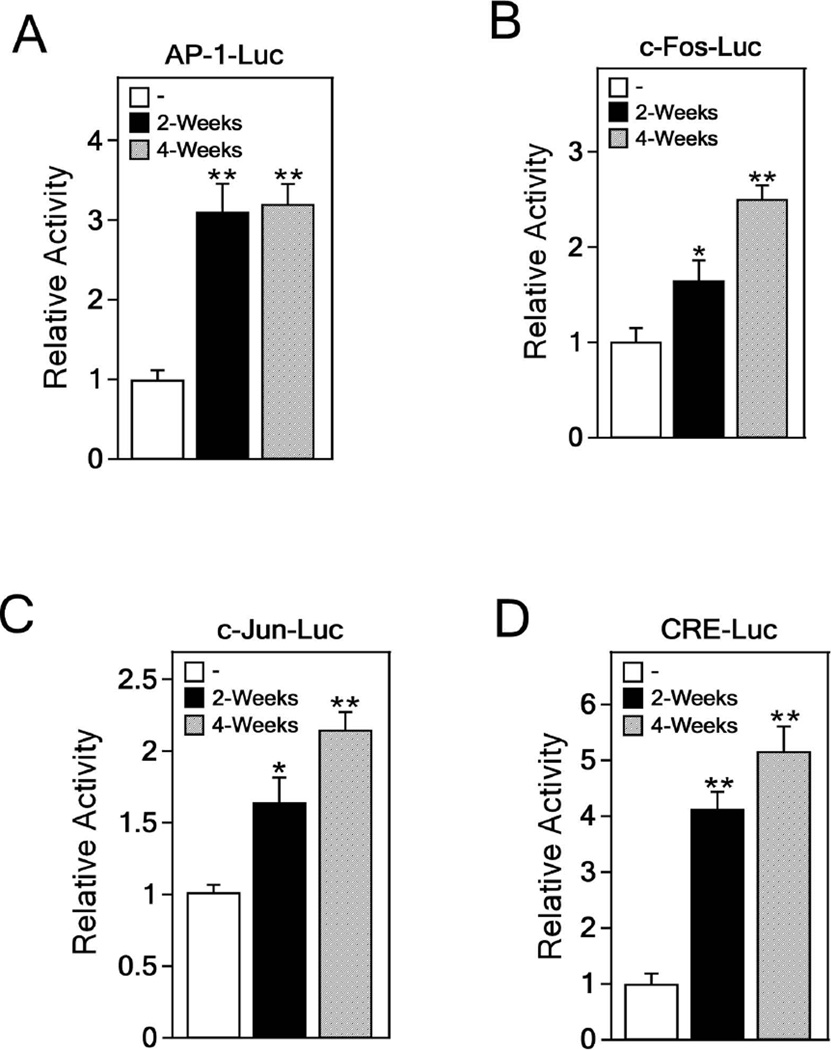

Exposure to arsenic increases AP-1 activation

The AP-1 transcription factor is a dimeric complex that can include combinations of Fos, Jun or ATF proteins [23]. AP-1 activation is known to play an important role in multistage development of tumors [24,25]. To determine whether arsenic affects AP-1 activation, we co-transfected the AP-1-, c-Fos-, c-Jun- or CRE-luciferase reporter plasmid and the pCMV-β-Gal gene into arsenic-treated or -untreated BALB/c 3T3 cells. Our results showed that arsenic significantly increased AP-1 activation (Figure 3A) and c-Fos (Figure 3B) and c-Jun (Figure 3C) promoter activity in transformed BALB/c 3T3 cells. We also found a significant enhancement of the CRE promoter activity in arsenic-treated BALB/c 3T3 cells (Figure 3D). CRE is a cAMP response promoter element that regulates RNA polymerase activity and binding of activated CREB in cAMP-response genes [26]. These data indicated that AP-1 transactivation activity and CRE promoter activity are induced in cells transformed by arsenic (0.5 µM) exposure.

Figure 3.

Increments of AP-1 activation in arsenic-induced transformed BALB/c 3T3 cells. The luciferase activity of AP-1 (A), c-Fos (B), c-Jun (C), or CRE (D) is increased in BALB/c 3T3 cells transformed by arsenic exposure. Arsenic-induced transformed BALB/c 3T3 cells were transfected with a plasmid mixture containing the AP-1-, c-Fos-, c-Jun- or CRE-luciferase reporter gene (200 ng) with the pCMV-β-Gal gene (50 ng) for normalization. At 36 h after transfection, the firefly luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates and normalized against β-galactosidase activity. Significant differences were evaluated using the Student’s t-test and the respective asterisks indicate a significant increase in luciferase activity in arsenic-treated cells compared to untreated cells (*, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01).

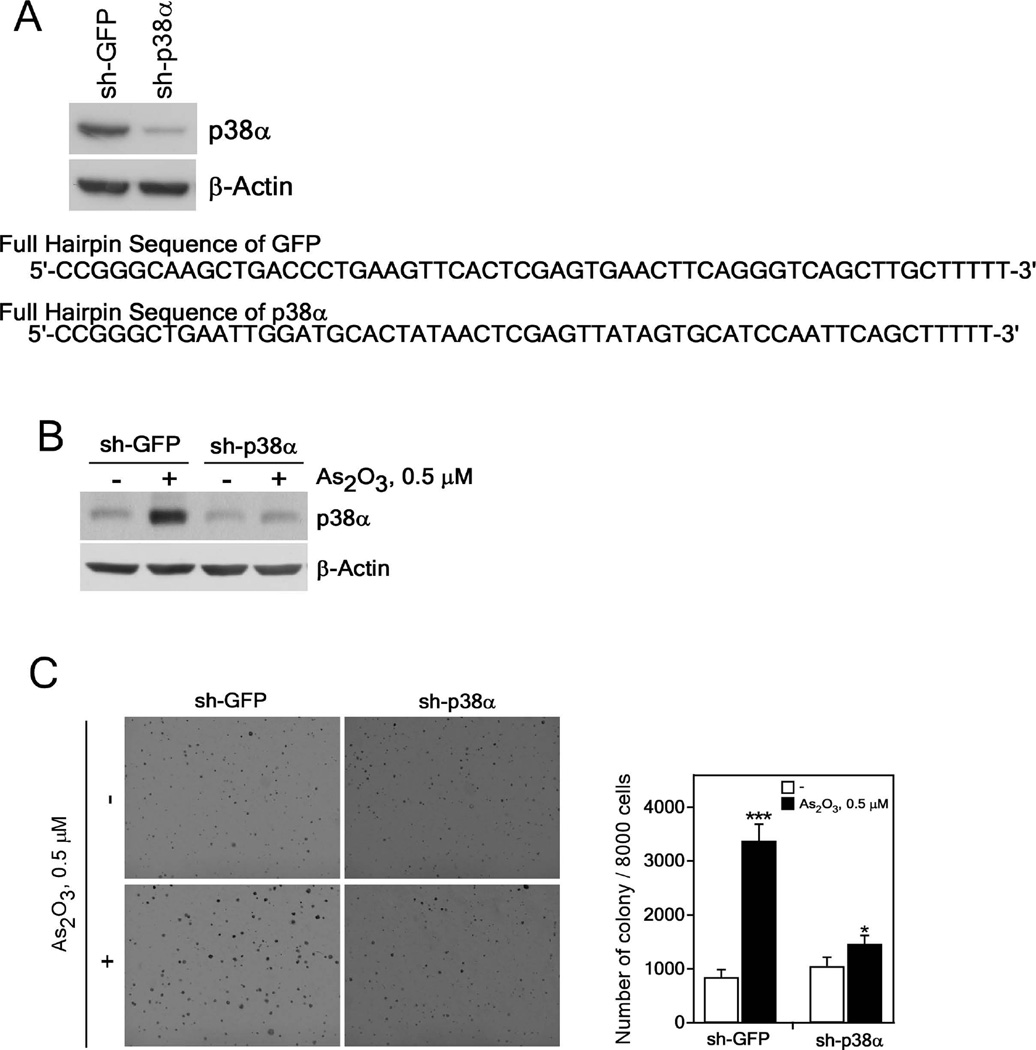

Knockdown of p38α MAPK effectively prevents neoplastic transformation induced by exposure to arsenic

To verify that the p38α MAPK protein is associated with neoplastic transformation induced by 0.5 µM arsenic exposure, we established knockdown of p38α in BALB/c 3T3 cells with sh-p38α to compare with cells transfected with a control vector (sh-GFP). Results indicated that endogenous p38α protein expression was suppressed by about 90% in p38α knockdown BALB/c 3T3 cells compared with cells expressing sh-GFP (Figure 4A). To examine the effect of suppressing p38α expression on arsenic-induced cell transformation, we stimulated cells with 0.5 µM As2O3 for 2 weeks in a 5% CO2 incubator. Arsenic exposure for 2 weeks had no effect on p38α expression in p38α knockdown cells compared with sh-GFP control cells (Figure 4B). Arsenic induction of neoplastic transformation in sh-p38α cells was significantly inhibited compared with cells expressing sh-GFP (Figure 4C). These results showed that p38α knockdown suppressed neoplastic transformation induced by 0.5 µM arsenic exposure. Overall, this result further demonstrated that p38α activation plays a key role in arsenic-induced cell transformation.

Figure 4.

Knocking down the p38α protein level suppresses anchorage-independent growth of arsenic exposed BALB/c 3T3 cells. (A) Knockdown of p38α efficiently suppresses the endogenous protein level of p38α (upper panel). The DNA sequences of sh-GFP and sh-p38α (lower panel) are shown. Knockdown p38α BALB/c 3T3 cells were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. The expression of p38α was analyzed in stably infected BALB/c 3T3 cells. (B) Expression of the p38α protein in sh-GFP- and sh-p38α-expressing BALB/c 3T3 cells treated with arsenic (0.5 µM) for 2 weeks. Lysate proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and the protein bands were visualized by Western blotting with a specific p38α primary antibody and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection of total β-actin was used to verify equal protein loading. (C) Cell transforming activity induced by arsenic is decreased in knockdown p38α stably-infected BALB/c 3T3 cells. sh-GFP- or sh-p38α-stably infected cells were exposed to 0.5 µM As2O3 in 0.1 M NaHCO3 for 2 weeks and these cells (8 × 103/mL) were cultured in 1 mL of 0.3% BME agar containing 10% calf serum (no additional arsenic was added). The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 7 days and then colonies were counted using a microscope and the Image-Pro PLUS (v.6) computer software program. The average colony number was calculated and photographed from 3 separate experiments and representative plates are shown. Significant differences were evaluated using the Student’s t-test and the respective asterisks indicate a significant increase in arsenic-treated sh-GFP cells compared to untreated or a decrease in arsenic-induced sh-p38 cell transformation compared with sh-GFP cells (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001).

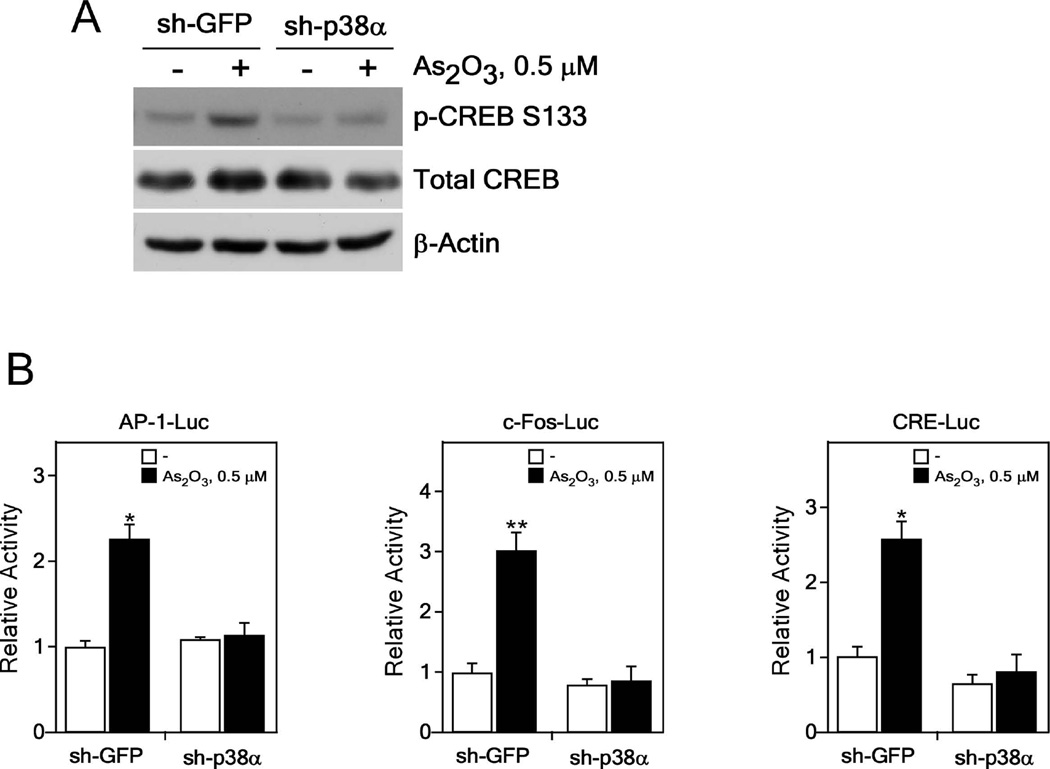

p38α MAPK knockdown suppresses AP-1 activation induced by arsenic exposure

We showed that arsenic-induced phosphorylation levels of CREB were decreased in p38α knockdown cells (Figure 5A). To determine whether knockdown of p38α inhibits AP-1 activation in arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation, we introduced the AP-1, c-Fos- or CRE-luciferase reporter plasmid and the pCMV-β-Gal gene into BALB/c 3T3 cells treated with arsenic for 2 weeks. Results demonstrated that induction of AP-1 activation was significantly decreased in p38α knockdown cells treated with arsenic for 2 weeks compared with sh-GFP control cells (Figure 5B, left). Similar results were obtained for arsenic-induced c-Fos promoter activity (Figure 5B, middle) and arsenic-induced CRE promoter activity (Figure 5B, right), confirming that the p38α protein plays a key role in AP-1 activation and c-Fos or CRE promoter activity induced in arsenic-treated transformed cells. These findings suggest that the p38α protein is involved in arsenic-induced cell transformation mediated through AP-1 activation and regulation of p38α downstream molecules, including the CREB transcription factor.

Figure 5.

AP-1 or CREB activation is repressed in p38α knockdown BALB/c 3T3 cells after arsenic exposure. (A) Phosphorylation of the p38α downstream CREB protein is suppressed in p38α knockdown BALB/c 3T3 cells. Lysate proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and the protein bands were visualized by Western blotting with specific primary antibodies and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection of total β-actin was used to verify equal protein loading. (B) The luciferase activity of AP-1 (left panel), c-Fos (middle panel) or CRE (right panel) is decreased in p38α knockdown BALB/c 3T3 cells treated with arsenic for 2 weeks. Arsenic-treated control (sh-GFP) or p38α knockdown BALB/c 3T3 cells were transfected with a plasmid mixture containing the AP1-, c-Fos- or CRE-luciferase reporter gene (200 ng) with the pCMV-β-Gal gene (50 ng) for normalization. At 36 h after transfection, the firefly luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates and normalized against β-galactosidase activity. Significant differences were evaluated using the Student’s t-test and the respective asterisks indicate a significant increase in luciferase activity of these proteins in arsenic-treated cells compared to untreated cells (*, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01).

Taken together, our results provide evidence showing that p38α MAPK signaling and AP-1 activation are required for neoplastic transformation induced by arsenic exposure. Finally, our findings suggest that p38α MAPK activation is essential for cell transformation induced by 0.5 µM exposure to arsenic.

DISCUSSION

Several studies indicated that an arsenic exposure was associated with malignant transformation in cancer cell lines and cancer patients [1,2,6,9,13,17,22]. Chronic arsenic exposure was reported to cause malignant transformation of lung cells and induce the expression of the mdig oncogene through JNK and STAT3 activation [27]. Others reported that the Ras oncogene is activated in malignant transformation of human prostate epithelial cells by arsenic [28]. HIF-2a-mediated inflammation is involved in arsenite-induced transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells [3] and c-Myc and c-Fos protein expression is increased in long-term arsenic-treated human small airway epithelial cells [7]. Epigenetic silencing of let7-c by Ras/NF-κB is reportedly involved in neoplastic transformation of human keratinocytes [29] and hypermethylation-mediated silencing of MLH1 is associated with chronic exposure of human epithelial cells to arsenic [9]. Herein, we found that BALB/c 3T3 cells is a cell line that can be useful for examining neoplastic transformation induced by arsenic treatment [22]. The BALB/c 3T3 cell model is widely used to study cancer development induced by chemicals, physical trauma and biological agents. The transformation mechanism is very likely somewhat different between epithelial and fibroblast cells but some similarities could also exist. However, caution should be used in comparing results between transformation of epithelial cells and fibroblasts. To determine the mechanism of arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation in BALB/c 3T3 cells, we examined the signaling pathways that were activated by arsenic treatment and found that 0.5 µM arsenic exposure significantly increased the phosphorylation and expression levels of p38α MAPK (Figures 1 and 2).

Many extracellular stimuli can induce the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK resulting in the activation of a wide range of substrates such as protein kinases, transcription factors, and other cytosolic and nuclear proteins [30]. Previous studies suggested that p38 MAPK exhibits tumor-suppressing functions [16,17,31]. However, p38 MAPK has also been associated with malignant transformation in many cancers [10,12,13,20,32]. Activated p38 MAPK contributed to cell migration and in vivo growth of melanoma [20] and TGF-β-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in mammary epithelial cells [26]. p38 MAPK promoted the malignant phenotype of squamous carcinoma cells by regulating survival, proliferation and invasion [21]. p38 MAPK plays a critical role in the H-Ras-induced invasive phenotype and migration in human breast epithelial cells [33]. Short-term exposure to arsenic reportedly activated the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in non-transformed human mammary epithelial MCF 10A cells [34] and human uroepithelial SV-HUC-1 cells [35]. Our study results suggested that p38α MAPK activation induced by arsenic exposure is heavily involved in neoplastic transformation (Figure 4). This finding supports the idea that p38α MAPK exhibits an oncogenic function and thus, p38α MAPK activation is linked with arsenic-induced cell transformation.

Based on an accumulation of evidence, AP-1 activation is closely associated with malignant transformation [24,36–39]. AP-1-mediated cyclin D1 expression plays an important role in arsenic-induced transformation of mouse epidermal cells [38] and c-Fos overexpression is correlated with cell transformation [39,40], late stage tumorigenesis [41], and tumor invasion [42]. Our data showed that the activation of AP-1 and c-Fos promoter activity were closely associated with cell transformation induced by exposure to arsenic (Figure 3A, B, and Figure 5B). Moreover, phosphorylation of CREB (Figure 1, 2B) and CRE promoter activity (Figure 3D) were significantly increased with arsenic treatment but decreased in cells when p38α MAPK expression was blocked (Figure 5A, B). Previous reports indicated that CREB might be linked with liver cancer development [43], hepatocellular carcinomas [44], tumorigenesis of endocrine tissues [45] and acute myeloid cell transformation [46]. Also, CREB phosphorylation by MSK1 reportedly mediated AP-1 activation or c-Fos gene expression in keratinocytes and promoted the growth of human epidermoid carcinoma cells [47,48]. We also found that phosphorylation and expression of MSK1, which is downstream of p38α MAPK, were increased in arsenic-treated transformed cells (Figure 1, 2A). The anchorage-independent colony formation ability induced by arsenic treatment was significantly decreased in BALB/c 3T3 cells deficient in MSK1 (Supplementary Figure 2A, B, C). Both AP-1 activation and c-Fos promoter activity were decreased in MSK1 knockdown cells (Supplementary Figure S2D). Taken together, AP-1 activation and increased c-Fos or CRE promoter activity and CREB expression are likely involved in arsenic-induced neoplastic transformation.

Overall, we demonstrated that total and phosphorylated p38α MAPK is required for cell transformation induced by 0.5 µM arsenic exposure. Arsenic exposure significantly increased AP-1 transcription activity and CREB activation, resulting in increased cell transformation. Taken together, our findings indicate that p38α MAPK could be a crucial target for cancer prevention or chemotherapy in arsenic-caused carcinogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Hormel Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants ES106548 and CA172457.

Abbreviations

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- MEFs

murine embryonic fibroblasts

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- CRE

cAMP response element

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- ATF2

activating transcription factor 2

- MSK1

mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1

- BMI1

B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog

- SUZ12

suppressor of zeste 12 homolog (Drosophila)

- sh-RNA

short hairpin-RNA

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- BME

basal medium eagle

- CS

calf serum

- As2O3

arsenic trioxide

- NaHCO3

sodium bicarbonate

- β-Gal

beta-galactosidase

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

NOTE: whole blots are presented in Supplementary Figures 3–9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Waalkes MP. Inorganic arsenic and human prostate cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(2):158–164. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebel TW. Arsenic and drinking water contamination. Science. 1999;283(5407):1458–1459. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1455e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu Y, Zhao Y, Xu W, et al. Involvement of HIF-2alpha-mediated inflammation in arsenite-induced transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;272(2):542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Ling M, Xu Y, et al. The repressive effect of NF-kappaB on p53 by mot-2 is involved in human keratinocyte transformation induced by low levels of arsenite. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116(1):174–182. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pi J, Diwan BA, Sun Y, et al. Arsenic-induced malignant transformation of human keratinocytes: involvement of Nrf2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(5):651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stueckle TA, Lu Y, Davis ME, et al. Chronic occupational exposure to arsenic induces carcinogenic gene signaling networks and neoplastic transformation in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;261(2):204–216. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen G, Calaf GM, Partridge MA, et al. Neoplastic transformation of human small airway epithelial cells induced by arsenic. Mol Med. 2008;14(1–2):2–10. doi: 10.2119/2007-00090.Wen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Qian X, et al. Further studies on aberrant gene expression associated with arsenic-induced malignant transformation in rat liver TRL1215 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216(3):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treas J, Tyagi T, Singh KP. Chronic exposure to arsenic, estrogen, and their combination causes increased growth and transformation in human prostate epithelial cells potentially by hypermethylation-mediated silencing of MLH1. Prostate. 2013;73(15):1660–1672. doi: 10.1002/pros.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar B, Koul S, Petersen J, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-driven MAPKAPK2 regulates invasion of bladder cancer by modulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity. Cancer research. 2010;70(2):832–841. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khandrika L, Lieberman R, Koul S, et al. Hypoxia-associated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated androgen receptor activation and increased HIF-1alpha levels contribute to emergence of an aggressive phenotype in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28(9):1248–1260. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Iyoda K, Sasaki Y, Horimoto M, et al. Involvement of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97(12):3017–3026. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg AK, Basu S, Hu J, et al. Selective p38 activation in human non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26(5):558–564. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomerance M, Quillard J, Chantoux F, Young J, Blondeau JP. High-level expression, activation, and subcellular localization of p38-MAP kinase in thyroid neoplasms. J Pathol. 2006;209(3):298–306. doi: 10.1002/path.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Jenson SD, Abbott RT, et al. Involvement of multiple signaling pathways in follicular lymphoma transformation: p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase as a target for therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(12):7259–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1137463100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pruitt K, Pruitt WM, Bilter GK, Westwick JK, Der CJ. Raf-independent deregulation of p38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases are critical for Ras transformation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(35):31808–31817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SN, Lee KT, Tsai CJ, Chen YJ, Yeh YT. Phosphorylated p38 and JNK MAPK proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2012;42(12):1295–1301. doi: 10.1111/eci.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickson JA, Huo D, Vander Griend DJ, Lin A, Rinker-Schaeffer CW, Yamada SD. The p38 kinases MKK4 and MKK6 suppress metastatic colonization in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer research. 2006;66(4):2264–2270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolado I, Swat A, Ajenjo N, De Vita G, Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. p38alpha MAP kinase as a sensor of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(2):191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estrada Y, Dong J, Ossowski L. Positive crosstalk between ERK and p38 in melanoma stimulates migration and in vivo proliferation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22(1):66–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junttila MR, Ala-Aho R, Jokilehto T, et al. p38alpha and p38delta mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms regulate invasion and growth of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(36):5267–5279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HG, Kim DJ, Li S, et al. Polycomb (PcG) proteins, BMI1 and SUZ12, regulate arsenic-induced cell transformation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(38):31920–31928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karin M, Liu Z, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(2):240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Ludes-Meyers J, Zhang Y, et al. Inhibition of AP-1 transcription factor causes blockade of multiple signal transduction pathways and inhibits breast cancer growth. Oncogene. 2002;21(50):7680–7689. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park YG, Nesterova M, Agrawal S, Cho-Chung YS. Dual blockade of cyclic AMP response element- (CRE) and AP-1-directed transcription by CRE-transcription factor decoy oligonucleotide. gene-specific inhibition of tumor growth. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(3):1573–1580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhowmick NA, Zent R, Ghiassi M, McDonnell M, Moses HL. Integrin beta 1 signaling is necessary for transforming growth factor-beta activation of p38MAPK and epithelial plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(50):46707–46713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun J, Yu M, Lu Y, et al. Carcinogenic metalloid arsenic induces expression of mdig oncogene through JNK and STAT3 activation. Cancer Lett. 2014;346(2):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ngalame NN, Tokar EJ, Person RJ, Xu Y, Waalkes MP. Aberrant microRNA Expression Likely Controls RAS Oncogene Activation During Malignant Transformation of Human Prostate Epithelial and Stem Cells by Arsenic. Toxicol Sci. 2014;138(2):268–277. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang R, Li Y, Zhang A, et al. The acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties and neoplastic transformation of human keratinocytes induced by arsenite involves epigenetic silencing of let-7c via Ras/NF-kappaB. Toxicol Lett. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coulthard LR, White DE, Jones DL, McDermott MF, Burchill SA. p38(MAPK): stress responses from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(8):369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bulavin DV, Phillips C, Nannenga B, et al. Inactivation of the Wip1 phosphatase inhibits mammary tumorigenesis through p38 MAPK-mediated activation of the p16(Ink4a)-p19(Arf) pathway. Nat Genet. 2004;36(4):343–350. doi: 10.1038/ng1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Li Y, Wang K, Wang Y, Yin W, Li L. P38/NF-kappaB/snail pathway is involved in caffeic acid-induced inhibition of cancer stem cells-like properties and migratory capacity in malignant human keratinocyte. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim MS, Lee EJ, Kim HR, Moon A. p38 kinase is a key signaling molecule for H-Ras-induced cell motility and invasive phenotype in human breast epithelial cells. Cancer research. 2003;63(17):5454–5461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Hock JM, Sullivan C, et al. Activation of the p38 MAPK/Akt/ERK1/2 signal pathways is required for the protein stabilization of CDC6 and cyclin D1 in low-dose arsenite-induced cell proliferation. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111(6):1546–1555. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu S, Wang F, Yan L, et al. Oxidative stress and MAPK involved into ATF2 expression in immortalized human urothelial cells treated by arsenic. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87(6):981–989. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong Z, Birrer MJ, Watts RG, Matrisian LM, Colburn NH. Blocking of tumor promoter-induced AP-1 activity inhibits induced transformation in JB6 mouse epidermal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(2):609–613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu G, Bibus DM, Bode AM, Ma WY, Holman RT, Dong Z. Omega 3 but not omega 6 fatty acids inhibit AP-1 activity and cell transformation in JB6 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(13):7510–7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131195198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Li J, Gao J, Huang C. c-Jun/AP-1 pathway-mediated cyclin D1 expression participates in low dose arsenite-induced transformation in mouse epidermal JB6 Cl41 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HG, Lee KW, Cho YY, et al. Mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1-mediated histone H3 phosphorylation is crucial for cell transformation. Cancer research. 2008;68(7):2538–2547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clayton AL, Rose S, Barratt MJ, Mahadevan LC. Phosphoacetylation of histone H3 on c-fos- and c-jun-associated nucleosomes upon gene activation. EMBO J. 2000;19(14):3714–3726. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reichmann E, Schwarz H, Deiner EM, et al. Activation of an inducible c-FosER fusion protein causes loss of epithelial polarity and triggers epithelial-fibroblastoid cell conversion. Cell. 1992;71(7):1103–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saez E, Rutberg SE, Mueller E, et al. c-fos is required for malignant progression of skin tumors. Cell. 1995;82(5):721–732. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Liu X, Wu H, et al. CREB up-regulates long non-coding RNA, HULC expression through interaction with microRNA-372 in liver cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):5366–5383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovach SJ, Price JA, Shaw CM, Theodorakis NG, McKillop IH. Role of cyclic-AMP responsive element binding (CREB) proteins in cell proliferation in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206(2):411–419. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg D, Groussin L, Jullian E, Perlemoine K, Bertagna X, Bertherat J. Role of the PKA-regulated transcription factor CREB in development and tumorigenesis of endocrine tissues. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shankar DB, Cheng JC, Kinjo K, et al. The role of CREB as a proto-oncogene in hematopoiesis and in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arthur JS, Fong AL, Dwyer JM, et al. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 mediates cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation and activation by neurotrophins. J Neurosci. 2004;24(18):4324–4332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schiller M, Bohm M, Dennler S, Ehrchen JM, Mauviel A. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 is critical for interleukin-1-induced, CREB-mediated, c-fos gene expression in keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2006;25(32):4449–4457. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.