Organic-inorganic 1D periodic necklace-like nanostructures are fabricated using confined synthesis of inorganic nanocrystals.

Keywords: uniform, organic-inorganic shish-kebabs, nanonecklace-like nanostructures, nanodisks, amphiphilic worm-like diblock copolymer, nanoreactors, simulations, self-consistent field theory

Abstract

Assembling nanoparticles into one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures with precisely controlled size and shape renders the exploration of new properties and construction of 1D miniaturized devices possible. The physical properties of such nanostructures depend heavily on the size, chemical composition, and surface chemistry of nanoparticle constituents, as well as the close proximity of adjacent nanoparticles within the 1D nanostructure. Chemical synthesis provides an intriguing alternative means of creating 1D nanostructures composed of self-assembled nanoparticles in terms of material diversity, size controllability, shape regularity, and low-cost production. However, this is an area where progress has been slower. We report an unconventional yet general strategy to craft an exciting variety of 1D nanonecklace-like nanostructures comprising uniform functional nanodiscs periodically assembled along a stretched flexible polymer chain by capitalizing on judiciously designed amphiphilic worm-like diblock copolymers as nanoreactors. These nanostructures can be regarded as organic-inorganic shish-kebabs, in which nanodisc kebabs are periodically situated on a stretched polymer shish. Simulations based on self-consistent field theory reveal that the formation of organic-inorganic shish-kebabs is guided by the self-assembled elongated star-like diblock copolymer constituents constrained on the highly stretched polymer chain.

Introduction

Owing to their structural anisotropy and unique optical, electrical, magnetic, and catalytic properties, the synthesis of one-dimensional (1D) inorganic nanostructures, including nanorods, nanowires, nanobelts, and nanotubes (1–4), has emerged as an important scientific activity in nanomaterials and nanotechnology for use in solar cells (5, 6), supercapacitors (7), hydrogen generation (8), photodetectors (9), light-emitting diodes (10), field-effect transistors (11), and biosensors (12, 13), to name but a few. 1D nanostructures are often produced by template-assisted electrochemical deposition (14), virus-enabled synthesis (15), chemical vapor deposition (16), and controlled colloidal synthesis (17, 18). In the latter context, effective colloidal synthetic approaches to 1D inorganic necklace-like morphology composed of self-assembled, periodically positioned nanocrystals with well-controlled dimension, chemical composition, and phase purity are comparatively few and limited in scope (19, 20).

The concept of organic molecular necklace was first proposed two decades ago for the description of a rotaxane containing many threaded α-cyclodextrins (α-CDs) (21). Inorganic nanonecklaces can be regarded as 1D nanostructures with desired functions and properties comprising well-defined nanoscopic building blocks. Many efforts in this area have been devoted to exploiting self-assembly techniques based on intrinsic interactions between the building blocks [for example, van der Waals force, electrostatic interactions (22), and dipole-dipole attraction (23)] or external fields [for example, a magnetic field (24, 25)] to achieve 1D nanonecklace-like nanostructures. However, most of the techniques are subject to certain limitations, such as non-uniform size and shape (26), and are difficult to generalize. It is worth noting that in comparison to the bulk reports on synthesis of nanotubes and nanowires, the preparation of nanonecklaces by chemical synthesis instead of by self-assembly or the application of external fields is surprisingly rare.

Here, we demonstrate a general and robust strategy for the in situ synthesis of a variety of 1D inorganic nanonecklaces composed of periodically assembled, uniform nanocrystals with precisely controlled size and composition by using the rationally designed, amphiphilic, unimolecular, worm-like diblock copolymers poly(acrylic acid)-block-polystyrene (PAA-b-PS) as nanoreactors. First, nanoreactors are judiciously synthesized by sequential atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) of tert-butylacrylate (tBA) and styrene (St) from a polyrotaxane-based macroinitiator, yielding worm-like poly(tert-butylacrylate)-block-polystyrene (PtBA-b-PS), followed by the hydrolysis of PtBA into PAA (that is, yielding PAA-b-PS). The polyrotaxane-based macroinitiator is virtually prepared by forming an inclusion complex between α-CD and linear polyethylene glycol (PEG). Subsequently, the preferential coordination interaction between metal moieties of precursors and functional groups of PAA in worm-like PAA-b-PS creates PS-capped inorganic nanonecklaces in which a wide range of regularly spaced disc-like nanocrystals (hereafter referred to as nanodiscs), including semiconductor CdSe, magnetic Fe3O4, and ferroelectric BaTiO3, are threaded by the flexible yet stretched PEG chain. Quite intriguingly, because PEG acts as the central stem with nanodiscs periodically grown on it, such linearly assembled nanonecklaces resemble organic-inorganic nanohybrid shish-kebabs. The nanodiscs (kebabs) are oriented perpendicular to the PEG shish, although the latter cannot be identified under transmission electron microscope (TEM) because of small size and low electron density. The average distance between adjacent nanodisc kebabs is 2 nm, with an average nanodisc size of 4 nm. To elucidate the mechanism governing the formation of nanonecklaces, we performed simulations based on self-consistent field theory (SCFT) and calculated the dimensions of nanonecklaces (that is, diameter, thickness, and spacing) from different samples, which are in substantial agreement with the experimental results. Our work reveals the versatility of the strategy of capitalizing on amphiphilic worm-like diblock copolymer template for directing the formation of a wide diversity of periodically spaced nanocrystals. These linearly assembled nanostructures may exhibit a broad range of new properties and applications as a result of size-dependent physical properties of individual nanocrystals and the collective interactions between nanocrystals because of their close proximity within nanostructures.

Results

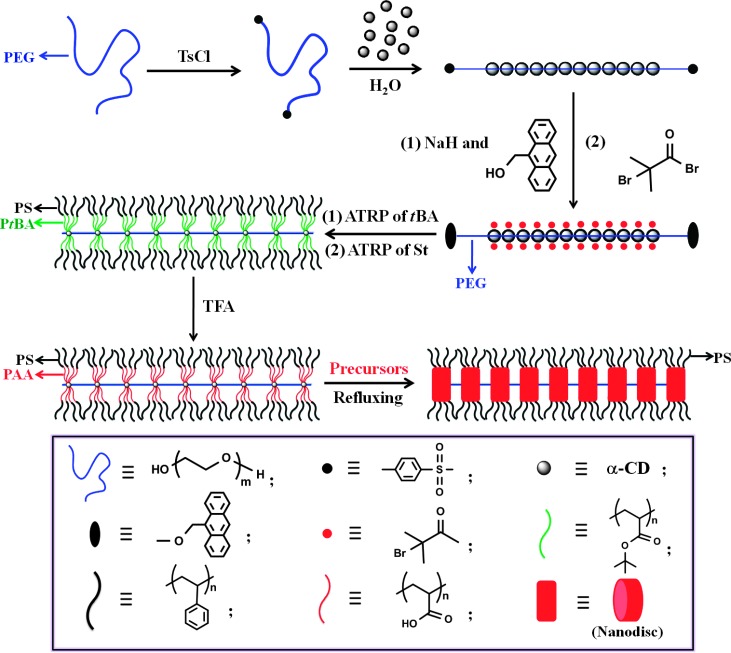

Synthesis of unimolecular worm-like diblock copolymer micelles

PEG (MPEO = 4 kg/mol) was tosylated at its chain ends to yield PEG-bis-tosylate (PEG-Ts2) (27) (upper middle panel in Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods). Polypseudorotaxanes (that is, α-CD–PEG-Ts2 with no stopper capped at the ends of PEG; upper right panel in Fig. 1) were then prepared by forming gel-like inclusion complexes between α-CDs and linear PEG-Ts2 (fig. S1) (27, 28). A larger stoppering agent, 9-hydroxymethylanthracene, was subsequently used in an attempt to prevent dethreading of α-CDs based on the previous work [that is, forming α-CD–PEG-bis-9-methylanthracenyl (α-CD–PEG-MA2); two ends of PEG were capped by 9-methylanthracenyl groups] (29). The 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of polyrotaxane α-CD–PEG-MA2 in DMSO-d6 (hexadeuterated dimethyl sulfoxide) only exhibited the broad signals of α-CD, signifying the typical threaded state (fig. S2) as free α-CDs result in the narrow signals instead. The esterification of 18 hydroxyl groups on α-CD with 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide resulted in a polyrotaxane macroinitiator, 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2 (central right panel in Fig. 1). In sharp contrast to the α-CD–PEG-MA2 polyrotaxane, the 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2 polyrotaxane had good solubility in CDCl3 (fig. S3). Worm-like PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymer was then synthesized by a “grafting from” approach through sequential ATRP of tBA and St using 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2 as macroinitiator. The worm-like architecture was virtually composed of a number of star-like PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymers on α-CDs that were connected by a PEG chain (central left panel in Fig. 1). Both inner PtBA blocks and outer PS blocks are hydrophobic. The hydrolysis of PtBA with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) yielded amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer containing inner hydrophilic PAA blocks and outer hydrophobic PS blocks (see Materials and Methods; lower left panel in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the synthesis of organic-inorganic shish-kebab–like nanohybrids (lower right panel) composed of periodic nanodisc-like kebabs (red) on PEO shish (blue) by exploiting amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer (lower left panel) as nanoreactor.

Notably, during the threading step, the threaded α-CDs pack closely (upper right panel) because of hydrogen bonding between adjacent α-CDs. After tBA and St monomers are sequentially polymerized (that is, grafted) from the worm-like macroinitiator (central right panel), α-CDs are separated because of steric crowding of the long PtBA and PS chains grafted. There are about 18 PtBA-b-PS chains on each α-CD because of the presence of 18 hydroxyl groups on each α-CD that allows the growth of 18 chains. For clarity, however, only four chains are shown on both sides. The stoppering units at the PEG chain ends in the central left and lower two panels are also omitted for clarity.

Three worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers with different molecular weights (that is, samples 1 to 3) were synthesized and characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy. As an example, figs. S4 to S6 display the NMR measurements on worm-like PtBA homopolymer, PtBA-b-PS, and PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer of sample 1, respectively. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) traces of worm-like PtBA homopolymer and PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymer were shown in fig. S7. Table 1 summarizes the structural parameters of the three worm-like PAA-b-PS samples used in the study.

Table 1. Molecular characteristics of worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers.

| Samples | Mn,PAA* | Mn, PS* | PDI† |

| Sample 1 | 9.6 K | 4.8 K | 1.19 |

| Sample 2 | 11.1 K | 5.2 K | 1.16 |

| Sample 3 | 6.8 K | 5.0 K | 1.15 |

*Molecular weight (Mn) of each arm was calculated from 1H NMR data.

†Polydispersity index (PDI) of PtBA-b-PS, the precursor of PAA-b-PS, was determined by GPC using polystyrene standards for calibration and THF as solvent. Samples 1 to 3 are the diblock copolymer templates for CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3, respectively.

Crafting organic-inorganic shish-kebabs

Amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers were then exploited as nanoreactors to structure-direct the precursors into inorganic functional nanostructures. Strikingly, rather than 1D nanorod- or nanowire-like inorganic nanostructures completely templated by worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers as one may have expected, chainlike inorganic nanostructures resembling a pearl necklace-type arrangement (nanonecklace) were yielded, within which distorted nanoparticles (that is, nanodiscs) were intimately and permanently capped with PS chains on the surface. The formation of these surprising nanonecklaces will be discussed in detail later.

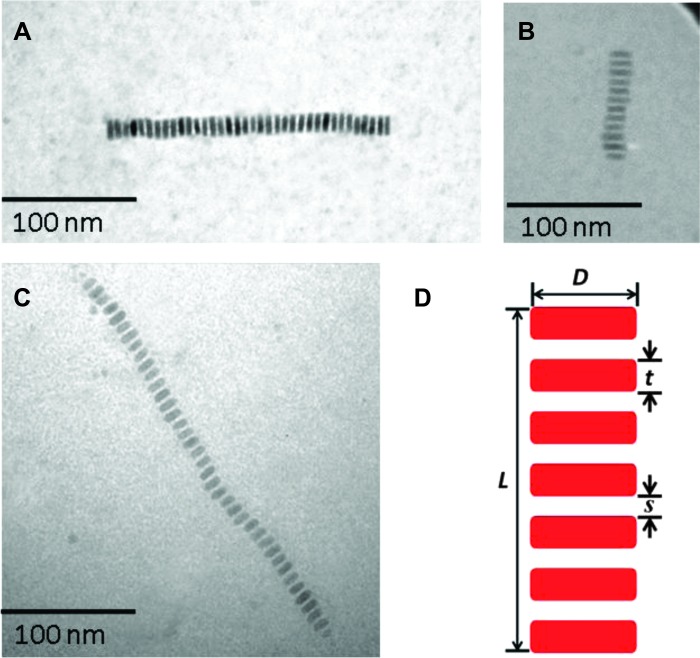

We first synthesized CdSe nanonecklace using amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer as template to demonstrate the effectiveness of our strategy in producing high-quality nanonecklace-like structures (Fig. 2A). The growth mechanism involves loading of the inner PAA region of amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS with the desired metal moieties. A certain amount of amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers (sample 1 in Table 1) was dissolved in a mixture of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and benzyl alcohol (BA) at DMF/BA = 9:1 (volume ratio) at room temperature, followed by the addition of CdSe precursors [that is, Cd(acac)2 and Se]. Tri-n-octylphosphine (TOP) to act as the reducing agent for Se. The inner PAA blocks in worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers are highly hydrophilic, rendering the preferential incorporation of precursors into the interior space occupied by PAA blocks through strong coordination interaction between the metal moieties of precursors and the carboxyl groups of PAA (30). Consequently, CdSe nanodiscs with PS chains capped on the surface were formed into a well-proportioned nanonecklace-like structure as unambiguously evidenced by TEM imaging obtained from a dilute CdSe solution. The emergence of highly oriented, long CdSe necklace suggested a template-assisted growth of CdSe nanodiscs. The CdSe nanodiscs capped by PS chains were connected by the PEG chain and closely packed along it. In this context, such nanostructures are reminiscent of nanoscopic organic-inorganic shish-kebabs (31, 32), in which nanodisc kebabs were closely and periodically spaced on the stretched PEG shish. It is noteworthy that the PEG shish was not visible under TEM because it is a single chain and has low electron density compared to inorganic CdSe nanodiscs. Similarly, the PS chains tethered on the surface of the nanodisc and PAA within the nanodisc were also not observed.

Fig. 2. TEM images of (A) semiconductor CdSe, (B) magnetic Fe3O4, and (C) ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanonecklaces.

(D) Schematic illustration of an individual nanonecklace showing dimensions: the diameter (D) and thickness (t) of a nanodisc, the spacing (s) between adjacent nanodiscs, and the total length (L) of a nanonecklace. The PS chains that intimately and permanently capped on the necklace surface, and the PEO stem that connected all nanodiscs are omitted for clarity in (D).

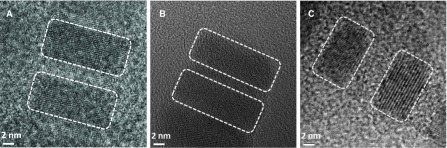

The representative high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) characterization of CdSe nanodiscs within nanonecklace revealed that they had continuous crystalline lattice (Fig. 3A). The crystal structure of CdSe based on HRTEM was further corroborated by x-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) microanalysis. The XRD of nanonecklaces showed the characteristic Bragg reflections that can be assigned to CdSe (fig. S8). Moreover, the EDS microanalysis displayed Cd and Se signals, confirming the successful synthesis of CdSe nanonecklaces (fig. S11). Notably, within the nanonecklace, CdSe nanodiscs remained individualized, an attribute that may impart the tailoring of electronic coupling strength of nanodiscs and lead to efficient electronic devices, such as solar cells (33).

Fig. 3. HRTEM images of two nanocrystal kebabs oriented perpendicularly to the substrate.

(A) Semiconductor CdSe. (B) Magnetic Fe3O4. (C) Ferroelectric BaTiO3. White dashed rectangles are for guidance. Scale bar, 2 nm.

On the basis of the worm-like diblock copolymer nanoreactor strategy, in addition to semiconductor CdSe, other functional nanonecklaces in which nanodiscs were directly capped by PS chains and laterally connected can be crafted, including magnetic Fe3O4 (Fig. 2B) and ferroelectric BaTiO3 (Fig. 2C), by adding appropriate precursors to selectively react with the PAA blocks in amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS (samples 2 and 3 in Table 1, respectively). The precursors were FeCl2·4H2O and FeCl3·6H2O for Fe3O4 nanonecklaces, and BaCl2·2H2O and TiCl4 for BaTiO3 nanonecklaces, respectively. The corresponding HRTEM images of Fe3O4 and BaTiO3 were shown in Fig. 3 (B and C), respectively. We note that the lattice fringes in Fe3O4 nanodiscs as well as BaTiO3 nanodiscs were not parallel to one another as in CdSe nanodiscs. It has been demonstrated that a slight sample tilting could result in the lattice fringes altering their orientation parallel to the long axis of nanocrystal to a perpendicular orientation (19). Here, it is plausible that a slight tilting of individual nanodiscs with respect to the substrate of TEM grid may occur because the PEG chain was flexible and α-CDs were threaded by the PEG axle. The success in synthesizing Fe3O4 and BaTiO3 nanostructures was also further confirmed by XRD and EDS characterizations (figs. S9, S10, S12, and S13). Such Fe3O4 and BaTiO3 nanonecklaces may find potential applications in spin electronic devices (34) and display photoelectric devices (35), respectively.

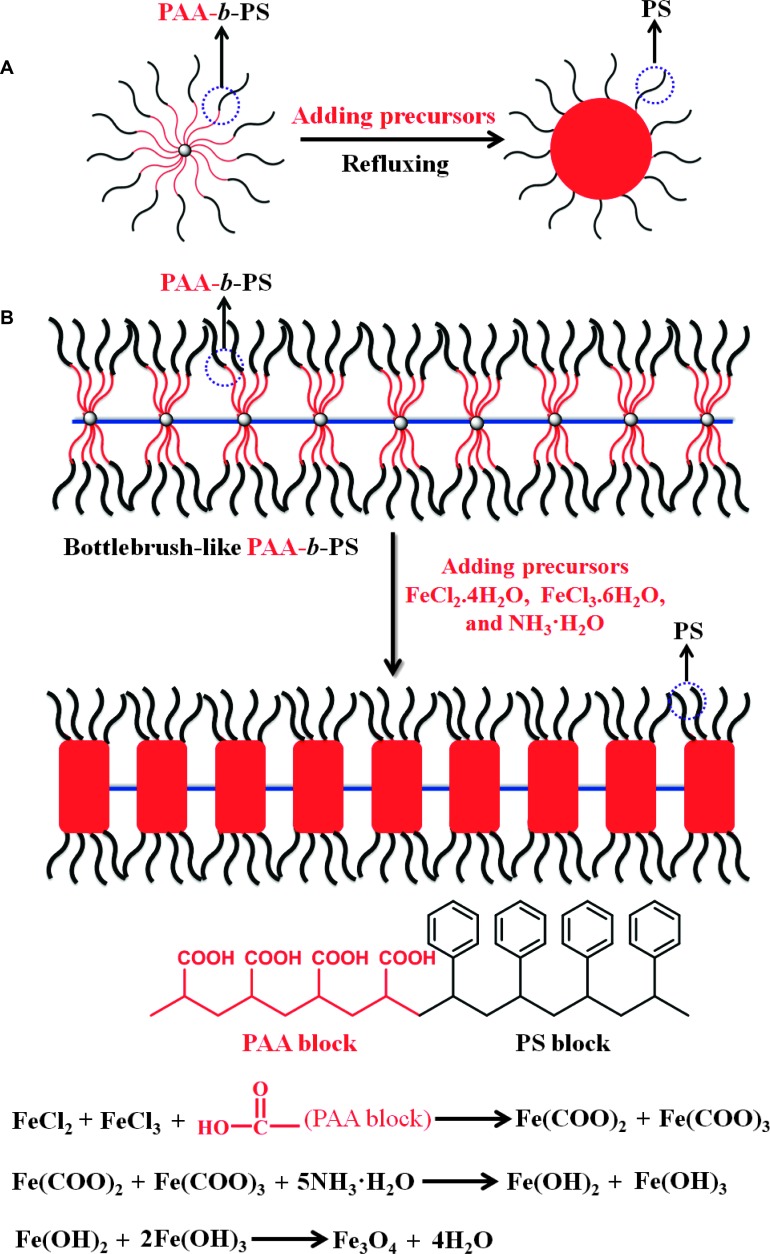

A variety of spherical colloidal nanoparticles have been synthesized by using star-like unimolecular micelle as template prepared from a β-CD core (30). It is not surprising that, by extension, using 1D micellar structures as template, anisotropic nanocrystals may be created, which is highly desirable because their physicochemical properties are often more interesting and unique than those of isotropic nanoparticles for many technological applications (36). Here, amphiphilic worm-like micelles rationally designed and synthesized were exploited as template to create surprising nanodiscs. It is obvious that the use of an amphiphilic star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer (37) as template would lead to the formation of spherical nanoparticles (Fig. 4A). In stark contrast, in an amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer template, both PAA and PS chains cannot retain their spherical random coil-like conformation as in star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer because all PAA-b-PS chains were confined on the PEG chain through the threaded α-CDs (that is, attached by one end). Moreover, because there were a number of α-CDs threaded on the PEG stem, PAA-b-PS chains grown from one α-CD core had to stretch out to alleviate the unavoidable steric crowding from the chains grafted from the neighboring α-CD core. These PAA-b-PS chains can be regarded as brushes. The interplay of the steric repulsion between adjacent α-CD–threaded PAA-b-PS brushes on the stretched PEG chain and the high density of threaded PAA-b-PS brushes on an individual α-CD (18 chains total) caused the energetically favored periodic separation of each α-CD–based PAA-b-PS brush. This explains why by capitalizing on amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers as nanoreactors, instead of continuous nanorods or nanowires, nanonecklaces were achieved despite the fact that a large amount of α-CDs were added in the reaction in an attempt to improve their threading density (Fig. 4B). Such high density of PAA-b-PS brushes constrained on the PEG was also responsible for forming stretched PEG chain despite the flexible nature of PEG. Together, each individual constituent of nanonecklace [that is, the 18-arm star-like PAA-b-PS diblocks connected to each α-CD (lower left panel in Fig. 1)] squeezed and extended perpendicularly with respect to the PEG stem, thereby forming elongated PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers (ellipsoid-shaped) of an α-CD rather than spherical shape, which in turn resulted in straight nanonecklaces consisting of periodic nanodiscs (that is, distorted rather than spherical nanoparticles) (Fig. 4B). To gain insight into the formation mechanism of nanonecklaces, we invoked the SCFT, a powerful method for solving the equilibrium problem, to calculate the self-assembly of star-like diblock copolymers threaded in the flexible yet highly stretched PEG chain, as elaborated later.

Fig. 4. Formation mechanisms of (A) spherical nanoparticle and (B) 1D nanonecklace.

The growth of Fe3O4 nanonecklace was taken as an example in (B). The formation of Fe3O4 nanonecklace underwent the coordination interaction between the precursors and amphiphilic star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer constituents, followed by the hydrolysis and condensation reaction at elevated temperature to yield Fe3O4 nanonecklace.

Discussion

The TEM characterizations showed that within an individual nanonecklace, the diameter D and thickness t of nanodiscs were remarkably uniform. Table 2 summarizes the dimensions of CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3 nanodiscs shown in Fig. 2. The D and t of CdSe nanodiscs were 10 ± 1 nm and 4 ± 0.5 nm, respectively. For Fe3O4 nanodiscs, D and t were 12 ± 1 nm and 3 ± 0.5 nm, respectively. A D of 8 ± 1 nm and a t of 5 ± 0.5 nm were found for BaTiO3 nanodiscs. It is not surprising that the D of CdSe nanodiscs was smaller than that of Fe3O4 nanodiscs, but larger than that of BaTiO3 nanodiscs, because the molecular weight of PAA block in the amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS template in sample 1 (Mn = 9.6 K; for CdSe synthesis) was lower than that in sample 2 (Mn = 11.1 K; for Fe3O4 synthesis) but higher than that in sample 3 (Mn = 6.8 K; for BaTiO3 synthesis) (Table 1). This observation may also be partially correlated to the separation distance, s, between adjacent nanodiscs. For example, the smaller s between neighboring nanodiscs indicated that PAA-b-PS diblocks in the worm-like template had to stretch more perpendicularly with respect to the PEG chain to accommodate the steric crowding with the adjacent diblocks as noted above, thereby leading to a decrease in t and an increase in D of PAA blocks in the worm-like template, and thus a reduced t and an increased D. This reflected well in HRTEM images (Fig. 3), where Fe3O4 nanodiscs were the most distorted, exhibiting the largest D/t (~4) as compared to CdSe nanodiscs (D/t ~2.5) and BaTiO3 (D/t ~2).

Table 2. Dimensions of CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3 nanonecklaces.

| Samples | D (nm)* | t (nm)* | s (nm)* | L (nm)* |

| CdSe | 10 ± 1 | 4 ± 0.5 | 2 ± 0.2 | 220 ± 5 |

| Fe3O4 | 12 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 105 ± 5 |

| BaTiO3 | 8 ± 1 | 5 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 320 ± 5 |

*The diameter (D), thickness (t), spacing (s), and length (L) within an individual nanonecklace were determined by TEM and HRTEM.

The ability to predict the dimensions of nanodisc and the spacing between adjacent nanodiscs within a nanonecklace on the basis of the chain lengths (that is, molecular weights) of PAA and PS in PAA-b-PS diblocks that are constrained on an α-CD and experience the steric repulsion from the adjacent α-CD–threaded PAA-b-PS diblocks, and compare them with experimental observations, would provide useful insight into the nanonecklace formation. First, the phase behaviors of star-like diblock copolymers without being threaded in PEG chain were investigated. Because mixed solvents of DMF and BA were used in the experiment, in which DMF is a good solvent for both PAA and PS, and BA is a good solvent for PAA, the parameters chosen in calculation were χABN = 350, χASN = 290, χBSN = 320 (A and B blocks refer to the inner PAA and outer PS blocks, respectively), and the polymer concentration ϕ = 0.35 (see Materials and Methods). The latter is reasonable to describe the local concentration near the nanonecklace, although the overall polymer concentration in the whole system is rather low. To compare with the experimental results, we chose three different volume fractions for samples 1 to 3 (Table 3). Because there is no threading of star-like diblock copolymers by a PEG chain, spherical micelles were observed (fig. S15). The corresponding diameters of inner PAA cores, DPAA (white arrows in fig. S15), were 0.49Rg (~4.9 nm), 0.64Rg (~6.4 nm), and 0.38Rg (~3.8 nm) for samples 1, 2, and 3, respectively, where Rg is the radius of gyration of linear diblock copolymer with the degree of polymerization N. Notably, all micelle diameters were smaller than Rg.

Table 3. Corresponding volume fraction used in calculation.

| Samples | Mn, PAA | Mn, PS | fA | fB |

| Sample 1 | 9.6 K | 4.8 K | 0.65* | 0.35† |

| Sample 2 | 11.1 K | 5.2 K | 0.75‡ | 0.35 |

| Sample 3 | 6.8 K | 5.0 K | 0.45‡ | 0.35 |

*The volume fraction of PAA block is defined as Mn, PAA/(Mn, PAA + Mn, PS).

†The volume fraction of PS block is defined as Mn, PS/(Mn, PAA + Mn, PS).

‡To consider the length of PAA block in samples 2 and 3, the volume fraction of PAA block in these two samples is calculated to be [Mn, PAA/Mn, PAA (sample1)] × fA (sample1).

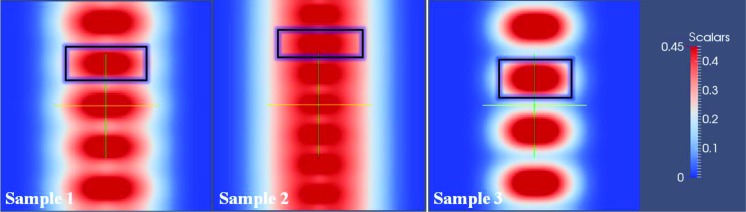

In the following, we concentrate on the phase behaviors of such star-like diblock polymer threaded in a PEG chain. The box size was chosen to be Lx = Ly = 3Rg (~30 nm), which is large enough for polymer in the direction perpendicular to the PEG stem. Remarkably, the calculations yielded the nanonecklace-like morphology composed of several star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers that were elongated because of the constraint imposed by the PEG chain (Fig. 5). We note that as the nanonecklace-like morphology formed in only one PEG chain was calculated, only a few elongated ellipsoid-shaped structures were observed in simulations as depicted in Fig. 5 (the density profile of outer PS blocks is shown in fig. S16). On the basis of the SCFT calculations, we obtained the dimensions of these elongated ellipsoid-shaped PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers. The length L of nanonecklace depends on the chain extension of PEG as described below and is difficult to predict in our model. Thus, we only calculated the D, t, s, and the number of elongated ellipsoid-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers per PEG chain, Nu. These parameters are summarized in table S1. Strikingly, the simulation results (table S1) correlated well with the experiments (Table 2). As the Mn of PAA increased, the D and Nu progressively increased from 8.5 ± 0.1 (sample 3) to 10.7 ± 0.8 (sample 1) to 11.5 ± 0.5 (sample 2), whereas t and s decreased from 5.1 ± 0.1 (sample 3) to 4.2 ± 0.1 (sample 1) to 3.0 ± 0.1 (sample 2). These values were in good accordance with those of CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3 nanonecklaces formed in experiments, substantiating that the elongated ellipsoid-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers acted precisely as nanoreactors to create inorganic nanodisc kebabs periodically situated on a stretched PEG shish. Moreover, in light of the experiments, Nu was 30/(4 + 2) ≈ 5 for CdSe nanodiscs, 30/(3 + 1.5) ≈ 7 for Fe3O4 nanodiscs, and 30/(5 + 2.5) ≈ 4 for BaTiO3 nanodiscs templated by the elongated ellipsoid-shaped PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymers, which were also successfully predicted by the model. The combination of theoretical calculations with experimental observations revealed the details of the formation mechanism of nanonecklaces.

Fig. 5. The calculated nanonecklace-like morphologies of three different star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers (that is, samples 1 to 3, from which CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3 nanonecklaces were grown, respectively) threaded in a PEG chain.

The box size is Lx = Ly = 3Rg (~30 nm).

It is worth noting that the formation of profoundly uniform nanodiscs was a direct consequence of the well-defined molecular architectures of each star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers threaded by the PEG chain (Fig. 1) as they were synthesized by ATRP, a living polymerization technique allowing for very high control of the chain length, that yielded individual star-like PAA-b-PS with narrow molecular weight distribution (that is, low PDI).

We now turn our attention to further understanding the formation of these uniquely long nanonecklaces containing regularly arranged uniform nanodiscs connected by the stretched PEG chain. A fully stretched PEG chain would have a length of about 30 nm (see the Simulation section in Materials and Methods). Given the dimensions of nanodiscs in Table 2, the number of nanodiscs within a nanonecklace is expected to be in the range of 4 to 7, and, ideally, the nanonecklace would be only 30 nm long. However, strikingly, a large number of nanodiscs, that is, nanonecklaces with a length of more than 30 nm, were created (Fig. 2, A to C, and fig. S17A, from which a representative histogram of the length distribution of CdSe nanonecklaces was depicted in fig. S17B). Quite intriguingly, an ultralong CdSe nanonecklace (~350 nm) composed of 55 densely and periodically positioned CdSe nanodiscs with a uniform D of 10 nm was obtained (fig. S18). It was also derived from sample 1 of threaded α-CD–based PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers (Table 1). The formation of long nanonecklace can be rationalized as follows. To introduce stoppering agent 9-hydroxymethylanthracene to synthesize 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2 (central right panel in Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods), we used 4-methylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (TsCl) as the activator to react with the hydroxyl groups of PEG (upper central panel; Fig. 1). Notably, it has been reported that TsCl is also a chain extension agent for PEG through inter-macromolecular coupling reactions to produce chain-extended linear PEG (scheme S1) (38–40). Thus, in addition to the formation of gel-like inclusion complexes between α-CDs and linear PEG-Ts2, it is highly possible to yield chain-extended linear inclusion complexes because of active Ts end groups in PEG-Ts2, because the PEG concentration used in the reaction was high (38–40). Therefore, the resulting worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers used as nanoreactors were chain-extended because of the chain-extension reaction of PEG. Thus, remarkably long inorganic functional nanonecklaces were yielded. The occurrence of different lengths of nanonecklaces (that is, different L for CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3 in Table 2) may be due to the different number of PEG connected to one another. We note that several short nanonecklaces containing four to seven nanodiscs in a non–chain-extended PEG (that is, a 30-nm-long PEG) may also self-assemble into long nanonecklace. Nonetheless, this would occur with a much lower possibility because such self-assembly is likely to form the kinks and misalignment of short nanonecklaces, which, however, were not observed in the study.

In summary, we have developed a general and viable strategy to create a large variety of 1D inorganic nanonecklaces with well-controlled dimensions and compositions. These functional nanonecklaces have the level of complexity enabled by capitalizing on amphiphilic worm-like diblock copolymers as nanoreactors. The nanonecklaces are composed of periodically chained, uniform nanodiscs intimately and permanently capped by hydrophobic polymer chains on the surface that afford the good solubility of the resulting nanonecklaces in nonpolar solvents. These intriguing nanonecklaces resemble organic-inorganic shish-kebabs having periodic nanodisc kebabs threaded by a flexible yet stretched polymer shish. Notably, the simulations based on real space SCFT agreed well with the experimental observations and offered insight into the mechanism of the formation of nanonecklaces. Further investigation on the physical properties of nanonecklaces and their utilizations is currently under way. Such 1D nanonecklaces may promise new opportunities for developing nanoscopic optical, electronic, optoelectronic, and magnetic materials and devices, as well as chemical sensors, catalysts, and surface-related chemical reactions because of the close proximity and larger active surface area of linearly assembled nanocrystals as compared to individual nanocrystals or aggregates.

Going beyond nonpolar solvent–soluble nanonecklaces, water-soluble nanonecklaces comprising uniform nanodiscs of diversified compositions can also be crafted by using double hydrophilic worm-like diblock copolymers [for example, poly(acrylic acid)-block-poly(ethylene oxide); PAA-b-PEO] for directed assembly and growth. Hence, the worm-like block copolymer nanoreactor approach may stand out as an emerging technique to produce a myriad of deterministically target nanonecklaces in a rational manner, which allow for exploration of new yet tailorable physical properties for applications in plasmonics, catalysis, optoelectronics, ferroelectrics, magnetic devices, and other areas.

Materials and Methods

Materials

α-CD (≥98%), PEG (average molecular weight, MPEG = 4000), p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (TsCl, ≥99%), sodium hydride [NaH, powder (moistened with oil), 55 to 65%], 9-hydroxymethylanthracene (97%), 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide (98%), and anhydrous 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP, 99.5%), N,N,N′,N′′,N′′-pentamethyldiethylene triamine (PMDETA, 99%), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. CuBr (98%, Sigma-Aldrich) was stirred overnight in acetic acid, filtered, washed with ethanol and diethyl ether successively, and dried in vacuum. tBA (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), anisole (Sigma-Aldrich, anhydrous, 99.7%), methyl ethyl ketone (Fisher Scientific, 99.9%), and DMF (Fisher Scientific, 99.9%) were distilled over CaH2 under reduced pressure before use. St (Sigma-Aldrich ≥99%) was washed with 10% NaOH aqueous solution and water successively, dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and CaH2 sequentially, and distilled under reduced pressure. Cadmium acetylacetonate [Cd(acac)2, ≥99.9% trace metals basis], iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O, ≥98%), iron(II) chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O, ≥99.0%), barium chloride dihydrate (BaCl2·2H2O, ≥99.0%), titanium(IV) chloride (TiCl4, ≥99.0%), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Selenium powder (Se, 99.5% metals basis), TOP (tech. 90%), and ammonium hydroxide (NH3·H2O, 28 to 30% NH3) were purchased from Alfa Aesar and used as received.

Synthesis of 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2

Polyrotaxane 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2 was synthesized according to the previous report (29) (central right panel in Fig. 1).

Synthesis of polypseudorotaxane α-CD–PEG-Ts2

First, PEG (10.0 g) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (25 ml) in a round-bottom flask at 0°C under a strong argon purge. 4-Methylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (p-TsCl) (4.0 g, 20.8 mmol) and pyridine (2.5 ml, 31.0 mmol) were then added into the solution. The reaction temperature was allowed to rise slowly to room temperature after 4 hours and then stirred overnight. The mixture was concentrated to about 5 ml and then added dropwise to 100 ml of diethyl ether (Et2O). The white precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with 3 × 50 ml of Et2O, and suspended in 100 ml of toluene. The solid was collected by filtration, dissolved in 8 ml of CH2Cl2, and then precipitated into 150 ml of Et2O. The white precipitate (PEG-Ts2, 75% yield) was dried at room temperature under vacuum for 3 days. Second, an aqueous solution of α-CD (3.0 g, 3.08 mmol) dissolved in 12 ml of water was added to 3 ml of tosylated PEG aqueous solution (200 mg, 0.1 mmol tosyl groups). The mixture was ultrasonically agitated for 15 min and became turbid. It was then allowed to stir overnight at room temperature, forming a white precipitate. The mixture was filtered to yield polypseudorotaxane α-CD–PEG-Ts2. The solid was dried at 50°C under vacuum for 5 days.

Synthesis of polyrotaxane α-CD–PEG-MA2

A solution of 9-hydroxymethylanthracene (4.6 g, 22.0 mmol) in 25 ml of DMF was slowly added to dry NaH (2.7 g, 67.5 mmol) in a round-bottom flask under a strong argon purge. The brown mixture was stirred for 10 min, and α-CD–PEG-Ts2 (2.7 g) was then introduced into the solution. After stirring overnight, the reaction mixture was poured into 150 ml of methanol. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with methanol, dissolved in 20 ml of DMSO, and precipitated into 150 ml of methanol. The procedure was repeated by the dissolution in 20 ml of DMSO and precipitation into 150 ml of water, and then filtered. Finally, the white solid product (polyrotaxane α-CD–PEG-MA2, 27% yield) was dried at 80°C overnight under vacuum.

Synthesis of 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2

Polyrotaxane α-CD–PEG-MA2 (200 mg) was dissolved in a solution of anhydrous 50 ml of NMP with LiCl (800 mg, 18.9 mmol) at 0°C. 2-Bromoisobutyryl bromide (2.0 g, 8.7 mmol) was then added dropwise to the solution with magnetic stirring. The reaction temperature was maintained at 0°C for 2 hours and then allowed to rise slowly to ambient temperature, after which the reaction was continued overnight. The worm-like macroinitiator [18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2, 48% yield; central right panel in Fig. 1; all 18 substitutable hydroxyl (–OH) groups on the surface of α-CD were converted into –Br because α-CD is a cyclic oligosaccharide consisting of six glucose units linked by α-1,4-glucosidic bonds] was obtained after the crude product was purified by washing sequentially with saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution and deionized water, and precipitated in cold hexane.

Synthesis of amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer

ATRP of tBA was performed using 18Br–α-CD–PEG-MA2 as a macroinitiator with 18 initiating sites (that is, allowing the formation of 18-arm star-like diblock copolymers as depicted below). The mixture of tBA/Br in the macroinitiator/CuBr/PMDETA = 800:1:1:2 (molar ratio) in methyl ethyl ketone (1 g of tBA in 1 ml of solvent) was degassed by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles in liquid N2 and then placed in an oil bath maintained at 60°C before polymerization. After the desired time, the mixture was dipped in an ice bath to terminate the reaction. The mixture was then diluted with acetone and passed through a column of neutral alumina to remove the copper salt. The product was precipitated in the mixed solvents of methanol/water (v/v = 1:1), filtered, and dried under vacuum to yield worm-like PtBA homopolymer. Subsequently, the mixture containing St/Br in the Br-end–functionalized PtBA macroinitiator/CuBr/PMDETA = 800:1:1:2 (molar ratio) in anisole (1 g of St in 1 ml of solvent) was degassed by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles in liquid N2 and then moved to an oil bath kept at 90°C (that is, subsequent ATRP of St). After the desired time, the reaction was terminated in liquid N2. Similarly, the reaction mixture was then diluted with tetrahydrofuran (THF) and passed through a neutral alumina column to remove the copper salt. The resulting product was precipitated in an excess amount of cold methanol, filtered, and dried under vacuum to yield double-hydrophobic worm-like PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymer (central left panel in Fig. 1). Notably, the worm-like diblock copolymer comprised a number of 18-arm star-like PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymers on α-CDs that were connected by a PEG chain. Finally, in a typical process, worm-like PtBA-b-PS diblock copolymer (0.3 g) was dissolved in 30 ml of CH2Cl2, followed by the addition of 10 ml of TFA. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 hours. After the hydrolysis, the resulting amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer (lower left panel in Fig. 1) was gradually precipitated in CH2Cl2. The final product was purified, washed with CH2Cl2, and thoroughly dried under vacuum at 40°C overnight.

Formation of organic-inorganic shish-kebabs comprising nanodisc kebabs periodically situated on the stretched flexible PEG shish

Linearly assembled semiconductor CdSe nanodiscs

In a typical synthesis, 10 mg of amphiphilic worm-like PAA-b-PS nanoreactor (that is, template) was dissolved in 9 ml of DMF in a three-neck flask, followed by the addition of 1 ml of BA and 107.8 mg of Cd(acac)2. The stirring was maintained for 2 hours under argon to ensure that Cd(acac)2 dispersed well in the DMF/BA (v/v = 9:1) mixture. When the temperature was slowly increased to the boiling point of DMF, 27.3 mg of selenium dissolved in 2 ml of TOP was injected dropwise into the three-neck flask. The reaction system was refluxed at 180°C for 2 hours to yield PS-capped semiconductor CdSe nanodiscs periodically assembled on PEG chain that was fully stretched (lower right panel in Fig. 1). The product was then washed three times with the toluene (solvent)/ethanol (nonsolvent) mixture at the volume ratio of toluene/ethanol = 1:2, followed by purification with a high-speed centrifuge to completely remove excess precursors.

Linearly assembled magnetic iron oxide nanodiscs (SPION)

Similarly, 10 mg of worm-like PAA-b-PS template was dissolved in 10 ml of mixed solvents containing DMF and BA at the volume ratio of DMF/BA = 9:1 in a 25-ml three-neck flask. FeCl2·4H2O (69 mg) and FeCl3·6H2O (93.7 mg) were added and purged with argon for 30 min with mechanical stirring. Ammonium hydroxide (2 ml) was then added at a rate of two drops per second. The solution gradually became turbid and turned from yellow to dark color. The reaction was carried out at 50°C for 30 min and then annealed at 80°C for 2 hours, yielding PS-capped magnetic Fe3O4 nanodiscs periodically arranged on the stretched PEG chain (lower right panel in Fig. 1). Magnetic separation was the easiest method to isolate linearly assembled Fe3O4 nanodiscs. Specifically, magnetic separation was performed by exposing the colloidal mixture (Fe3O4 nanoparticles and linearly assembled nanodiscs) to a strong magnet, followed by the redispersion of the ferrofluid by the vigorous shaking and then rapid collection of a fraction (that is, linearly assembled nanodiscs) on the wall of the vial with a weaker magnet (41).

Linearly assembled ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanodiscs

Likewise, 10 mg of worm-like PAA-b-PS template was dissolved in 10 ml of mixed solvents containing 9 ml of DMF and 1 ml of BA at room temperature, followed by the addition of 81 mg of BaCl2·2H2O, 13.9 mg of NaOH, and 65.8 mg of TiCl4. The solution was then refluxed under Ar at 180°C for 2 hours, yielding PS-capped ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanodiscs regularly spaced on the straight PEG chain (lower right panel in Fig. 1). A similar purification procedure as in the case of linearly assembled CdSe nanodiscs was performed.

Purification of nanonecklaces

It is noteworthy that as the precursors were in excess, when the reaction was finished, the final product contained nanonecklaces, nanoparticles obtained because of the dethreading of worm-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymer to form individual star-like PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers that served as templates, and precursors. On one hand, to obtain a pure fraction of nanonecklaces without precursors, the chain length of outer PS blocks should be increased during ATRP of St to improve the solubility of PS-capped nanonecklaces. Thus, nanonecklaces can be separated from precursors because of the solubility difference between nanonecklaces and precursors. On the other hand, the presence of outer PS blocks exerted steric hindrance that, to a certain extent, prevented the precursors from entering into the regime occupied by PAA blocks. Therefore, the outer PS blocks should not be too long. As a result, the PS chain lengths were optimized (Table 1) to facilitate the separation of nanonecklaces from precursors. Because the necklaces were much heavier than the nanoparticles and precursors, they were collected using high-speed centrifuge by gradually decreasing the speed.

TEM sample preparation

A drop of dilute PS-functionalized linearly assembled nanocrystals solution was deposited on a carbon-coated copper TEM grid (300 mesh) and allowed to slowly evaporate (covered with a watch glass) at room temperature. The use of high boiling point solvent, DMF, enabled slow evaporation at room temperature.

Characterizations

Molecular weights of polymers were measured by GPC (Shimadzu) equipped with an LC-20 AD HPLC pump and a refractive index detector (RID-10A, 120 V). THF was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min at 35°C. One Phenogel 5 μm Linear column and one Phenogel 5 μm 10E4A mixed bed column were calibrated with 10 PS standard samples with molecular weights ranging from 1.2 × 106 to 500 g/mol. All 1H NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer with the solvent resonances as the internal standard. The morphologies of CdSe, Fe3O4, and BaTiO3 nanostructures were imaged by TEM (JEOL TEM 100CX; operated at 100 kV). The EDS microanalysis of the samples was obtained by scanning electron microscopy (LEO 1530, Zeiss). The crystalline phase of the samples was examined by XRD (X’Pert PRO, Netherlands).

Simulations on self-assembly of star-like diblock copolymers unthreaded and threaded in one flexible yet highly stretched PEG chain based on the self-consistent filed theory

A binary blend consisting of incompressible 18-arm star-like (AB)18 diblock copolymers in the presence of solvent (S) was considered. The (AB)18 represents 18-arm star-like PAA-b-PS constituents in a worm-like diblock copolymer (see Materials and Methods), where 18 is the number of arms, and A and B blocks are the inner PAA and outer PS blocks, respectively, in star-like (AB)18 diblock copolymer. Because all α-CDs, from which 18-arm PAA-b-PS diblocks are grown, are threaded in a PEG chain, the star-like diblock copolymer core is thus constructed in the threaded area.

Each star-like diblock copolymer is assumed to have an equal degree of polymerization N, and thus, for each arm, the degree of polymerization is N/18. The volume fractions of A and B blocks, fA and fB, are defined as NA/N and NB/N, respectively, where NA and NB are the degree of polymerization of A and B blocks in a star-like diblock copolymer, respectively. ϕ is used to describe the concentration of star-like diblock copolymers. The interactions between i and j (i, j = A, B, and S) are characterized by Flory-Huggins interaction parameter χij. The lengths in SCFT are expressed in units of the radius of gyration of linear polymer, Rg = (Nb2/6)1/2, where b is the Kuhn length and N is the total degree of polymerization of star-like diblock copolymer. According to the many-chain Edwards theory (42–45), the free energy functional F per chain for star-like (AB)n diblock copolymer in the presence of solvent can be given by Eq. 1:

| 1 |

where ϕA(r) and ϕB(r) are the monomer densities, respectively, and ϕS(r) is the solvent density. QC and QS are the partition function of a single star-like diblock copolymer and a solvent molecule, respectively, given by Eqs. 2 and 3,

| 2 |

| 3 |

where qK(r, s) and K = A, B) are end-segment distribution functions. These distribution functions satisfy the modified diffusion equations in the following.

| 4 |

| 5 |

The initial condition for Eq. 5 is . To constrain α-CD on the PEG chain, the initial condition for Eq. 4 is (n = 18) (fig. S14) (46) if r is in the threaded area; otherwise, qA(r, 0) = 0.

The minimization of free energy with respect to the monomer densities and the mean fields leads to the following standard mean-field equations.

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

The split-step Fourier method (47, 48) was used to solve the modified diffusion equations for the end-segment distribution functions. The periodic boundary conditions are imposed automatically on the square cell in the split-step Fourier method. The box size chosen is to be 3Rg × 3Rg (~30 × 30 nm2); because the molecular weight of PEG, MPEG, was 4 kg/mol, the fully stretched PEG chain would have a length of ~30 nm based on the bond length and bond angle estimation (49), and be discretized into Nx × Ny = 128 × 128 lattices, representing the formation of nanonecklace in one PEG chain. The total chain contour, Ns, is divided into 720 segments.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This research was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-13-1-0101 and MURI FA9550-14-1-0037; to Z.L.), Minjiang Scholar Program (to Z.L.), National Science Foundation (ECCS-1305087; to Z.L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 21490573 to H. Xia and grant 21304051 to Y.X.), and the China Scholarship Council (H. Xu). Author contributions: Z.L. conceived the idea; H. Xu, X.P., H. Xia, and Z.L. initiated this work; Z.L., H. Xu, and X.P. designed the research program; H. Xu, X.P., Y.H., and J.J. performed the experiments; Y.X. performed the simulation; Z.L., H. Xia, H. Xu, X.P., and Y.X. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/e1500025/DC1

Fig. S1. Gel-like polypseudorotaxane α-CD–PEG–Ts2 inclusion complexes, in which α-CDs are threaded by linear PEG-Ts2.

Fig. S2. 1H NMR spectrum of polyrotaxane α-CD–PEG–MA2 in DMSO-d6.

Fig. S3. 1H NMR spectrum of polyrotaxane macroinitiator 18Br–α–CD–PEG-MA2 in CDCl3.

Fig. S4. 1H NMR spectrum of worm-like PtBA (sample 1 in Table 1) in CDCl3.

Fig. S5. 1H NMR spectrum of worm-like PtBA-b-PS (sample 1 in Table 1) in CDCl3.

Fig. S6. 1H NMR spectrum of worm-like PAA-b-PS (sample 1 in Table 1) in DMF-d7.

Fig. S7. GPC traces of worm-like PtBA (blue) and PtBA-b-PS (red) (sample 1 in Table 1).

Fig. S8. XRD pattern of semiconductor CdSe nanonecklaces.

Fig. S9. XRD pattern of magnetic Fe3O4 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S10. XRD pattern of ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S11. EDS spectrum of semiconductor CdSe nanonecklaces.

Fig. S12. EDS spectrum of magnetic Fe3O4 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S13. EDS spectrum of ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S14. Graphic illustration of the initial condition for qA(r, 0).

Fig. S15. Spherical micelles of 18-arm star-like diblock copolymer in the mixed solvents of DMF/BA.

Fig. S16. The calculated density profiles of A block (inner PAA) and B block (outer PS) in star-like diblock copolymers.

Fig. S17. (a) TEM image of a number of CdSe nanonecklaces obtained by drop-casting a high-concentration CdSe nanonecklace DMF solution on the TEM grid. (b) The corresponding histogram of the length distribution of CdSe nanonecklaces shown in (a).

Fig. S18. An ultralong CdSe nanonecklace.

Table S1. Calculated dimensions of elongated ellipsoid-shaped PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers on the PEG chain.

Scheme S1. Chain-extension reaction for the formation of chain-extended linear PEG.

References and Notes

- 1.Hu J. T., Odom T. W., Lieber C. M., Chemistry and physics in one dimension: Synthesis and properties of nanowires and nanotubes. Acc. Chem. Res. 32, 435–445 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia Y. N., Yang P. D., Sun Y. G., Wu Y. Y., Mayers B., Gates B., Yin Y. D., Kim F., Yan Y. Q., One-dimensional nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 15, 353–389 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Y., Duan X. F., Wei Q. Q., Lieber C. M., Directed assembly of one-dimensional nanostructures into functional networks. Science 291, 630–633 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C. L., Rosi N. L., Preparation of unique 1-D nanoparticle superstructures and tailoring their structural features. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6902–6903 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye M., Xin X., Lin C. J., Lin Z., High efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells based on hierarchically structured nanotubes. Nano Lett. 11, 3214–3220 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye M., Zheng D., Lv M., Chen C., Lin C., Lin Z., Hierarchically structured nanotubes for highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Mater. 25, 3039–3044 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Y. B., Li G. R., Wang Z. L., Su C. Y., Tong Y. X., Single-crystal ZnO nanorod/amorphous and nanoporous metal oxide shell composites: Controllable electrochemical synthesis and enhanced supercapacitor performances. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 1288–1292 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye M., Gong J., Lai Y., Lin C., Lin Z., High efficiency photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen generation enabled by palladium quantum dots sensitized TiO2 nanotube arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15720–15723 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z. X., Safdar M., Jiang C., He J., High-performance UV-visible-NIR broad spectral photodetectors based on one-dimensional In2Te3 nanostructures. Nano Lett. 12, 4715–4721 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen P. C., Shen G. Z., Chen H. T., Ha Y. G., Wu C., Sukcharoenchoke S., Fu Y., Liu J., Facchetti A., Marks T. J., Thompson M. E., Zhou C. W., High-performance single-crystalline arsenic-doped indium oxide nanowires for transparent thin-film transistors and active matrix organic light-emitting diode displays. ACS Nano 3, 3383–3390 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park W. I., Kim J. S., Yi G. C., Lee H. J., ZnO nanorod logic circuits. Adv. Mater. 17, 1393–1397 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feigel I. M., Vedala H., Star A., Biosensors based on one-dimensional nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 8940–8954 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigderman L., Khanal B. P., Zubarev E. R., Functional gold nanorods: Synthesis, self-assembly, and sensing applications. Adv. Mater. 24, 4811–4841 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin L., Park S., Huang L., Mirkin C. A., On-wire lithography. Science 309, 113–115 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam K. T., Kim D.-W., Yoo P. J., Chiang C.-Y., Meethong N., Hammond P. T., Chiang Y.-M., Belcher A. M., Virus-enabled synthesis and assembly of nanowires for lithium ion battery electrodes. Science 312, 885–888 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner R. S., Ellis W. C., Vapor-liquid-solid mechanism of single crystal growth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 4, 89–90 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gole A., Murphy C. J., Seed-mediated synthesis of gold nanorods: Role of the size and nature of the seed. Chem. Mater. 16, 3633–3640 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milliron D. J., Hughes S. M., Cui Y., Manna L., Li J., Wang L.-W., Paul Alivisatos A., Colloidal nanocrystal heterostructures with linear and branched topology. Nature 430, 190–195 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigman M. B., Ghezelbash A., Hanrath T., Saunders A. E., Lee F., Korgel B. A., Solventless synthesis of monodisperse Cu2S nanorods, nanodisks, and nanoplatelets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 16050–16057 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S. Z., Kou X. S., Yang Z., Shi Q. H., Stucky G. D., Sun L. D., Wang J. F., Yan C. H., Nanonecklaces assembled from gold rods, spheres, and bipyramids. Chem. Commun., 1816–1818 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada A., Li J., Kamachi M., The molecular necklace: A rotaxane containing many threaded α-cyclodextrins. Nature 356, 325–327 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H., Wang D. Y., Controlling the growth of charged-nanoparticle chains through interparticle electrostatic repulsion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3984–3987 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Z. Y., Kotov N. A., Giersig M., Spontaneous organization of single CdTe nanoparticles into luminescent nanowires. Science 297, 237–240 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu M. J., Lu Y., Zhang S., Guo S. R., Lin B., Zhang M., Yu S. H., High yield synthesis of bracelet-like hydrophilic Ni–Co magnetic alloy flux-closure nanorings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11606–11607 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Y. X., He L., Yin Y. D., Magnetically responsive photonic nanochains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3747–3750 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai Q., Worden J. G., Trullinger J., Huo Q., A “nanonecklace” synthesized from monofunctionalized gold nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 8008–8009 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao T., Beckham H. W., Direct synthesis of cyclodextrin-rotaxanated poly(ethylene glycol)s and their self-diffusion behavior in dilute solution. Macromolecules 36, 9859–9865 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larraneta E., Ramon Isasi J., Self-assembled supramolecular gels of reverse poloxamers and cyclodextrins. Langmuir 28, 12457–12462 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teuchert C., Michel C., Hausen F., Park D.-Y., Beckham H. W., Wenz G., Cylindrical polymer brushes by atom transfer radical polymerization from cyclodextrin–PEG polyrotaxanes: Synthesis and mechanical stability. Macromolecules 46, 2–7 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pang X., Zhao L., Han W., Xin X., Lin Z., A general and robust strategy for the synthesis of nearly monodisperse colloidal nanocrystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 426–431 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X. F., Li Y. L., One-dimensional hybrid nanostructures with light-controlled properties. Dalton Trans. 6447–6457 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C., Li L., Cai W., Kodjie S., Tenneti K., Nanohybrid shish-kebabs: Periodically functionalized carbon nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 17, 1198–1202 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Priyam A., Blumling D. E., Knappenberger K. L. Jr, Synthesis, characterization, and self-organization of dendrimer-encapsulated HgTe quantum dots. Langmuir 26, 10636–10644 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao Y., Liu S., Fang S., Jia D., Su H., Zhou W., Wiley J. B., Li F., Plum-like and octahedral Co3O4 single crystals on and around carbon nanotubes: Large scale synthesis and formation mechanism. RSC Adv. 2, 3496–3501 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu X., Zhang D., Zhao Q., Wang C., Zhang W., Wei Y., Large-scale synthesis of necklace-like single-crystalline PbTiO3 nanowires. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 27, 76–80 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zubarev E. R., Nanoparticle synthesis any way you want it. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 396–397 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pang X., Zhao L., Akinc M., Kim J. K., Lin Z., Novel amphiphilic multi-arm, star-like block copolymers as unimolecular micelles. Macromolecules 44, 3746–3752 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun T., Yu G.-E., Price C., Booth C., Cooke J., Ryan A. J., Cyclic polyethers. Polymer 36, 3775–3778 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singla S., Zhao T., Beckham H. W., Purification of cyclic polymers prepared from linear precursors by inclusion complexation of linear byproducts with cyclodextrins. Macromolecules 36, 6945–6948 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pang X., Wang G., Jia Z., Liu C., Huang J., Preparation of the amphiphilic macro-rings of poly(ethylene oxide) with multi-polystyrene lateral chains and their extraction for dyes. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 45, 5824–5837 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puntes V. F., Zanchet D., Erdonmez C. K., Alivisatos A. P., Synthesis of hcp-Co nanodisks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 12874–12880 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards S. F., Statistical mechanics of polymers with excluded volume. Proc. Phys. Soc. London 85, 613–624 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helfand E., Theory of inhomogeneous polymers: Fundamentals of the Gaussian random-walk model. J. Chem. Phys. 62, 999–1005 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 44.A. C. Shi, Development in Block Copolymer Science and Technology (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 45.G. H. Fredrickson, The Equilibrium Theory of Inhomogeneous Polymers (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu Y. C., Li W. H., Qiu F., Lin Z. Q., Self-assembly of 21-arm star-like diblock copolymer in bulk and under cylindrical confinement. Nanoscale 6, 6844–6852 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasmussen K. O., Kalosakas G., Improved numerical algorithm for exploring block copolymer mesophases. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 40, 1777–1783 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tzeremes G., Rasmussen K. O., Lookman T., Saxena A., Efficient computation of the structural phase behavior of block copolymers. Phys. Rev. E 65, 041806 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haller J., Beno B. R., Houk K. N., Why is the concerted (2+2) mechanism of the reactions of SO3 with alkenes favored over the (3+2) mechanism? Density functional and correlated ab initio calculations and a frontier MO analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 6468–6472 (1998). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/e1500025/DC1

Fig. S1. Gel-like polypseudorotaxane α-CD–PEG–Ts2 inclusion complexes, in which α-CDs are threaded by linear PEG-Ts2.

Fig. S2. 1H NMR spectrum of polyrotaxane α-CD–PEG–MA2 in DMSO-d6.

Fig. S3. 1H NMR spectrum of polyrotaxane macroinitiator 18Br–α–CD–PEG-MA2 in CDCl3.

Fig. S4. 1H NMR spectrum of worm-like PtBA (sample 1 in Table 1) in CDCl3.

Fig. S5. 1H NMR spectrum of worm-like PtBA-b-PS (sample 1 in Table 1) in CDCl3.

Fig. S6. 1H NMR spectrum of worm-like PAA-b-PS (sample 1 in Table 1) in DMF-d7.

Fig. S7. GPC traces of worm-like PtBA (blue) and PtBA-b-PS (red) (sample 1 in Table 1).

Fig. S8. XRD pattern of semiconductor CdSe nanonecklaces.

Fig. S9. XRD pattern of magnetic Fe3O4 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S10. XRD pattern of ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S11. EDS spectrum of semiconductor CdSe nanonecklaces.

Fig. S12. EDS spectrum of magnetic Fe3O4 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S13. EDS spectrum of ferroelectric BaTiO3 nanonecklaces.

Fig. S14. Graphic illustration of the initial condition for qA(r, 0).

Fig. S15. Spherical micelles of 18-arm star-like diblock copolymer in the mixed solvents of DMF/BA.

Fig. S16. The calculated density profiles of A block (inner PAA) and B block (outer PS) in star-like diblock copolymers.

Fig. S17. (a) TEM image of a number of CdSe nanonecklaces obtained by drop-casting a high-concentration CdSe nanonecklace DMF solution on the TEM grid. (b) The corresponding histogram of the length distribution of CdSe nanonecklaces shown in (a).

Fig. S18. An ultralong CdSe nanonecklace.

Table S1. Calculated dimensions of elongated ellipsoid-shaped PAA-b-PS diblock copolymers on the PEG chain.

Scheme S1. Chain-extension reaction for the formation of chain-extended linear PEG.