Abstract

Objective

In HIV-infected adults in sub-Saharan Africa, asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia at the time of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation is associated with a >20% increased mortality. Provisional recommendations for treatment of asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia are neither well-substantiated nor feasible in many resource-poor settings. After hospitals in Tanzania implemented a program providing serum cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) screening with four-week intensive fluconazole treatment for CrAg-positive patients, we were asked to assess the impact of this program on mortality.

Design

In this retrospective operational research study, we documented six-month outcomes of HIV-infected adults who had had CD4 counts <200 cells/μL at the time of starting ART and had been screened for cryptococcal antigenemia over a period of 15 months.

Methods

We randomly selected three CrAg-negative patients, matched for ART start date, for every CrAg-positive patient who had been identified and treated with the four-week intensive fluconazole course. The primary outcome was six-month mortality in CrAg-positive and CrAg-negative groups.

Results

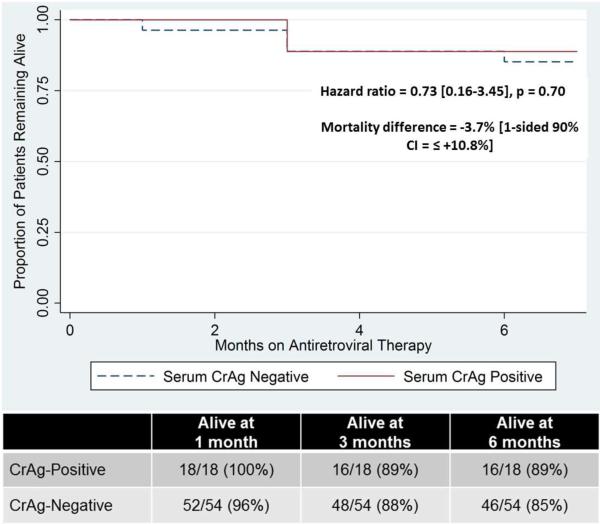

Mortality of CrAg-positive HIV-infected adults who received short-course fluconazole was non-inferior to CrAg-negative adults. At 6 months, 16/18 CrAg-positive and 46/54 CrAg-negative patients were alive (88.9% versus 85.1%, −3.9% absolute difference [1-sided 90% confidence interval +10.8%]). No deaths in the CrAg-positive group seemed to be due to cryptococcal meningitis.

Conclusions

This study suggests that even short-course intensive fluconazole could reduce the mortality of patients with asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia. Further studies are needed to confirm if this dose is both optimal for patient survival and feasible for wide implementation in resource-poor settings where mortality of cryptococcal disease is highest.

Keywords: cryptococcal antigenemia, HIV, fluconazole, sub-Saharan Africa, cryptococcal meningitis, antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, cryptococcal meningitis (CM) causes 720,000 deaths annually [1]. The mortality of CM in much of Africa is 40-66% [2,3]. This is due largely to factors including the unavailability of, or difficulty administering, gold-standard intravenous antifungal treatment with Amphotericin B and flucytosine [4–6], challenges monitoring for drug toxicity, and shortages of physicians able to perform serial lumbar punctures. For these reasons, preventing the disease altogether may most effectively reduce mortality. Screening asymptomatic patients for cryptococcal antigenemia provides a window for such pre-emptive intervention. Cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) becomes detectable in serum and urine an average of 22 days before symptom onset in patients who ultimately develop CM [2]. Asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia independently predicted mortality in patients initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) [7], and asymptomatic CrAg-positive HIV-infected adults have a 20% higher mortality than CrAg-negative adults [2,7,8].

Retrospective studies suggest that fluconazole at a variety of doses decreases mortality in CrAg-positive patients [2], and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends fluconazole for HIV-infected adults with asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia [9]. The WHO has provisionally recommended that fluconazole be dosed at 800mg daily for two weeks, then 400mg daily for eight weeks, then 200mg indefinitely, but admits that “the optimal antifungal regimen in this population remains to be determined” [9]. In resource-limited settings, such as our hospitals in Tanzania, fluconazole supply is limited and 5-10% of patients initiating ART are CrAg-positive [2,7]. Our hospital and many others in the region have therefore determined that implementing the current WHO-recommended fluconazole regimen is not feasible.

Therefore, two Tanzanian hospitals implemented a serum CrAg screening and shorter-course fluconazole treatment program for patients initiating ART. We were asked to determine outcomes and predictors of mortality after the program’s first 15 months. We hypothesized that the six-month mortality of CrAg-positive patients who received short-course intensive fluconazole would be comparable to that of CrAg-negative patients. This would be a remarkable achievement for patients whose mortality would otherwise be expected to exceed that of CrAg-negative patients by 15-20%.

Methods

This study was conducted at the outpatient HIV clinics of Bugando Medical Centre, the referral hospital for 13 million people in northwest Tanzania, and at Sekou-Toure Regional Hospital, both in Mwanza City.

The hospital screening program for asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia, which began in September 2012, was provided to all HIV-infected adults (≥18 years) initiating ART who had CD4+ T-cell counts (CD4 counts) ≤200 cells/μL. Patients were first screened for signs/symptoms of meningitis, and those who screened positive were referred for further workup. The remaining patients were tested for asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia using the serum CrAg lateral flow assay (Immuno-Mycologics, Inc, Oklahoma, USA), as previously described [10]. After CrAg-positive patients had been confirmed to have no signs or symptoms of meningitis, the program provided them with 800mg fluconazole orally for two weeks, followed by 400mg orally for two weeks, given at the same time that ART was initiated. This intense, short-course regimen was in accordance with the WHO’s conditional recommendation that CrAg-positive patients should be treated, as well as with hospital policy and feasibility based on fluconazole supply.

For our study, we identified all patients who had screened positive for CrAg during the first 15 months of the hospital program. We reviewed patients’ files and excluded from our analysis any who had a history of CM, prior fluconazole use, or who were subsequently transferred to other health facilities in the six months following their CrAg screening. For every CrAg-positive patient, we used the ART initiation record book to identify the subsequent three CrAg-negative patients who started ART. We obtained written informed consent from these CrAg-positive and CrAg-negative patients or their family members to review their charts and to re-test those who had been CrAg-positive for serum CrAg at least six months after they had been treated with short-course fluconazole.

We performed a single study visit approximately 6-10 months after patients’ initial CrAg screening and treatment. During this visit, we performed a physical examination and repeated the CrAg test. We also reviewed data from patients’ 1, 3, and 6-month visits to the CTC. Causes of death were determined from hospital records and verbal autopsy. Patients who were found to be CrAg-positive at the 6-10-month visit were given high-dose long-term fluconazole.

Data was analyzed using STATA13 (College Station, Texas). The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality rate in each group at six months. We conducted a non-inferiority analysis with an inferiority margin of 20%, based on the ~20% population-attributable mortality in CrAg-positive versus CrAg-negative patients [2,4,5]. Secondary endpoints included rates of cryptococcal meningitis and of non-meningeal cryptococcal disease in both groups. Medians and proportions were compared by Wilcoxon rank-sum and Fisher’s exact test respectively. Factors associated with mortality were evaluated by univariable and subsequent multivariable analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves and the Cox proportional hazards ratio were used to compare survival differences. Ethical clearance was obtained from the CUHAS/BMC/Sekou-Toure Ethics Committee and the IRB at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Results

From September 2012 to November 2013, 377 adults with CD4 counts <200 cells/μL initiated ART at our HIV clinics. Of these, 70 had had signs/symptoms that were possibly consistent with cryptococcal disease and had been referred for further workup rather than screening for asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia. In addition, 22 had used fluconazole previously, 59 were transferred to an outside facility in the six months following ART initiation, and 10 did not have serum CrAg testing. Therefore, 216 patients underwent serum CrAg screening in the first 15 months of the hospital program, and 18 of these (8.3%) tested positive. Among the remaining 198 CrAg-negative patients, 3 were selected serially after every positive patient was identified, yielding 54 CrAg-negative patients for comparison.

Study participants were 56% female, with a median age [interquartile range] of 36.5 [29.5-45] years, body mass index of 21.1 [18.8-23.7] kg/m2, and CD4 count of 96 [52-149.5] cells/μL. Over 65% had either WHO Stage 2 or 3 clinical disease. No statistically-significant differences were identified between CrAg-positive and CrAg-negative groups with respect to any of these characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and associations with mortality among HIV-infected patients with and without asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia at the time of antiretroviral therapy initiation.

| Characteristic | CrAg-positive patients (n=18) Number (%) or Median (IQR) |

CrAg-negative patients (n=54) Number (%) or Median (IQR) |

p-value for difference |

Association with Mortality (Univariable Analysis) (Odds Ratio, [95% Confidence Interval], p-value) |

Association with Mortality (Multivariable Analysis) (Odds Ratio, [95% Confidence Interval], p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.5 (34-49) | 36 (29-43) | 0.08 | 1.1 [1.02-1.18], p=0.008 | 1.3 [1.03-1.5], p=0.021 |

| Male gender | 5 (27.8%) | 27 (50%) | 0.17 | 6.3 [1.2-32.4], p=0.027 | 0.4 [0.02-10.6], p=0.64 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

20.0 (18.7-23.4) | 21.3 (18.8-24.0) | 0.63 | 0.73 [0.57-0.94], p=0.013 | 0.8 [0.5-1.3], p=0.38 |

| CD4+ T-cell count (cells/μL) |

89.5 (42-156) | 104 (56-148) | 0.95 | 0.98 [0.97-0.999], p=0.031 | 0.97 [0.95-1.00], p=0.051 |

| World Health Organization clinical stage |

1 – 3 (16.7%) 2 – 7 (38.9%) 3 – 6 (33.3%) 4 – 2 (11.1%) |

1 – 10 (18.5%) 2 – 13 (24.1%) 3 – 21 (38.9%) 4 – 10 (18.5%) |

0.66 |

13.6 [3.1-60.6], p=0.001 |

49.6 [2.4-1028], p=0.012 |

| Antiretroviral regimen AZT+3TC+EFZ AZT+3TC+NVP TDF+FTC+EFZ TDF+3TC+EFZ |

9 (50%) 6 (33%) 2 (11%) 1 (6%) |

21 (39%) 18 (33%) 11 (20%) 4 (7%) |

0.42 1 0.50 1 |

0.3 [0.1-1.6], p=0.15 2.3 [0.6-8.7], p=0.24 1.2 [0.2-6.2], p=0.86 1.6 [0.2-16.1], p=0.69 |

--- |

All CrAg-positive patients or their families retrospectively reported complete adherence to the four-week fluconazole regimen. In the CrAg-positive group, 2/18 (11.1%) died, compared to 8/54 (14.8%) in the CrAg-negative group by six months. In the CrAg-positive group, mortality incidence was 3.7% less (one-sided 90% CI, no more than 10.8% higher; two-sided 95% CI, [−3.4% − +25.6%]; Cox proportional hazards ratio=0.73 [0.16-3.45], p=0.70, Figure). In the positive cohort neither death was attributable to cryptococcal disease, whereas in the negative cohort, one patient died of CM confirmed by positive cerebrospinal fluid India ink and CrAg (Table 2). At the time of starting antiretroviral therapy three months prior to his death, the patient’s CD4 count had been 66 cells/μL.

Figure.

Survival of HIV-Infected Patients with and without Asymptomatic Cryptococcal Antigenemia at the time of ART Initiation.

Table 2.

Characteristics and findings of 10 HIV-infected patients who started antiretroviral therapy at Bugando Medical Centre and Sekou-Toure and died during six months of follow-up.

| Age (years) |

Sex | CD4 count at baseline (cells/μL) |

Month of Death |

Recorded cause of death |

Significant findings on history and examination from inpatient records |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrAg-positive patients | |||||

| 38 | Male | 16 | 3 |

Pneumocystis

jirovecii pneumonia |

Shortness of breath, cough, O2 saturation 68% on room air and 90% on 5L O2, CXR with bilateral opacities. Died on hospital day 2. |

| 55 | Male | 26 | 3 | Septic shock | Abdominal pain, BP 90/60, PR 105, RR 28, T 39.6°C, CXR normal. Given fluids and ceftriaxone; died on hospital day 1. |

| CrAg-negative patients | |||||

| 52 | Male | 2 | 1 | Disseminated tuberculosis |

Abdominal pain, cough, shortness of breath, O2 saturation 94% on room air, CXR with military pattern. Started on anti-TB regimen on hospital day 4; died on hospital day 9. |

| 37 | Female | 3 | 1 |

Pneumocystis

jirovecii pneumonia |

Cough, shortness of breath, O2 saturation 75% in room air and 92% on 8L of O2, chest clear on exam. Treated with ceftriaxone, azithromycin, cotrimoxazole, prednisone; died on hospital day 2. |

| 66 | Male | 63 | 3 | Hepatic encephalopathy |

Altered mental status, severe jaundice, ascites. No history of headaches, no neck stiffness on examination. Workup showed elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin and Hepatitis B surface antigen positivity; died on hospital day 5. |

| 44 | Male | 161 | 3 | Disseminated tuberculosis |

Cough, shortness of breath, night sweats, reduced urine output, abdominal pain, fevers. O2

saturation 97% on room air, BP 80/50, RR 30, PR 106. CXR with military pattern. Started on anti-TB regimen, ceftriaxone and fluids; died on hospital day 4. |

| 36 | Male | 66 | 3 | Cryptococcal meningitis |

Headaches worsening over 2 weeks, fever, neck stiffness. LP showed high opening pressure; CSF India ink and CrAg positive—diagnosed with possible IRIS cryptococcal meningitis. Started on IV fluconazole (1.2g/day); died on hospital day 4. |

| 40 | Female | 62 | 3 | Severe Malaria | High fevers (highest recorded during admission 40°C), vomiting. RBG on admission 4.6mmol/l, rapid test for malaria positive. Started on quinine; died on hospital day 2. |

| 50 | Male | 56 | 6 | Cardiogenic shock | Increasing fatigue, lower limb swelling and abdominal swelling over 3 weeks. BP 80/40, PR 78, RR 24. Bedside ultrasound showed reduced contractility of the heart and dilated chambers; died on hospital day 6. |

| 43 | Male | 148 | 6 | TB meningitis | Altered mental status, headaches and fever for past week, no cough. Brain CT scan showed no SOL. LP showed normal opening pressure, CrAg negative, India ink negative, increased white cell count. Started on anti-TB regimen and steroids; died on hospital day 5. |

List of abbreviations: CXR – chest X-ray, BP – blood pressure, PR – pulse rate, RR – respiratory rate, T – temperature, TB – tuberculosis, LP – lumbar puncture, IV – intravenous, CSF – cerebrospinal fluid, RBG – random blood glucose, CT computed tomography, SOL – space occupying lesion, WBC – white blood cell

Significant predictors of mortality on univariable analysis included: male gender (odds ratio (OR) 6.3 [1.2-32.4], p=0.027), older age (OR 1.10 [1.02-1.18] per year older, p=0.012), lower BMI (OR 0.73 [0.57-0.94] per unit increase, p=0.013), lower CD4 count (OR 0.98 [0.97-0.99)] per cell/μL increase, p=0.031), and advanced WHO clinical stage (OR 13.0 [3.1-60.6] per advancing stage, p=0.001). Of note, serum CrAg did not significantly predict mortality in either univariable or multivariable analysis (OR 0.72 [0.14-3.72], p=0.70 and OR 0.19 [0.005-7.6], p=0.38, respectively). Factors remaining significantly predictive of mortality on multivariable analysis were age, CD4 count, and WHO stage.

Two of the 16 living CrAg-positive patients had persistent antigenemia on serum retesting 6-10 months after their original screening and treatment with short-course high-dose fluconazole. The other fourteen patients were retested and were CrAg-negative. These patients, both women, had CD4 counts that had increased from 51 to 72 and 90 to 142 cells/ul on ART. Both remained asymptomatic and were restarted on long-term fluconazole.

Discussion

Six-month mortality of HIV-infected patients initiating ART with asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia who received an intensive four-week course of fluconazole was non-inferior to CrAg-negative patients. This finding is important at a time when the optimal fluconazole dose for CrAg-positive patients remains unknown, leading to conditional recommendations for high-dose and subsequent indefinite maintenance fluconazole. Lifelong fluconazole dosing may place severe strain on the fluconazole supply in resource-limited settings in which nearly 10% of patients initiating ART are CrAg-positive. Fluconazole is also the only treatment available for patients with invasive cryptococcal disease. A randomized, controlled trial recently demonstrated that a 10-week course of high-dose fluconazole (without the lifelong maintenance therapy afterwards) was associated with an approximately 15% reduction in mortality among HIV-infected African adults beginning antiretroviral therapy [8]. Ensuring that CrAg screening and treatment programs are feasible for wide implementation is critical to reducing AIDS-related mortality in the poorest settings.

Our study supports other data suggesting that fluconazole courses far shorter than the WHO recommendations may be beneficial in asymptomatic CrAg-positive patients. In Uganda, 71% of CrAg-positive patients treated with 200-400mg of fluconazole for 2-4 weeks survived for 30 months, compared with 0/5 who received no fluconazole [11]. In our cohort, we would have expected at least 4-5 of 18 CrAg-positive patients to develop CM if insufficiently treated. Instead, none developed CM and all but two cleared their antigenemia within 6 months. Notably, these two patients both had experienced a CD4 increase of <75 cells/μL, leading us to note that 2 of 4 patients with CD4 increases <75 cells/μL, compared with 0/12 patients with CD4 increases >75 cells/μL, had persistent antigenemia. This data suggests that shorter course fluconazole could be possible in people with good CD4 count recovery.

It is also possible that shorter, intense-course fluconazole could be less effective in patients with high fungal burdens. Due to limited resources, CrAg titers at the time of fluconazole initiation had not been measured in any patient in this study. Other possible causes of persistent antigenemia, denied by both of our patients, are poor adherence to fluconazole or use of concurrent medications (e.g. rifampin) that enhance fluconazole metabolism. Alternately, these patients, whose CD4 counts remained low after 6 months, may have cleared their initial antigenemia but subsequently become re-infected. Both patients restarted high-dose fluconazole and now remain on lifelong therapy, with ongoing follow-up.

Two important limitations of this study are the retrospective design and the small number of study subjects. Larger, prospective studies are underway to determine the relationship between CrAg titers and antigen clearance, as well as time to antigen clearance in asymptomatic patients given fluconazole.

Interestingly, one patient in our CrAg-negative cohort died of CM. A major strength of this work was our ability to trace causes of deaths for all ten patients. While we cannot determine whether this death represents a false-negative CrAg screen or a patient who acquired cryptococcal infection after starting ART, the 96-100% sensitivity of the serum CrAg assay [2] suggests the latter. The patient’s extremely low CD4 count (66 cells/μL at the time that he initiated ART three months prior to his death) suggests he may have remained susceptible to cryptococcal infection and acquired it shortly after beginning ART.

In conclusion, our work suggests that four weeks of high-dose fluconazole prevents death in CrAg-positive patients. Though small, the study’s robustness is attested by the finding that other well-known predictors (age, CD4 count, WHO stage) were significantly associated with mortality. Our work offers new hope for CM prevention even in settings where fluconazole is not limitless, and even where laboratory facilities are scarce since this study was done using a point-of-care diagnostic test. We strongly urge support for routine CrAg screening and pre-emptive fluconazole treatment for patients initiating ART, and for additional studies to further define optimal yet practical fluconazole dosing regimens.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the hard work and determination of the staff at the Care and Treatment Centres at Bugando and Sekou-Toure, as well as in the Department of Internal Medicine at the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences. We additionally deeply thank the patients for their willing participation in this study.

Support: This study was supported in part by grants from the NIH (K24 AI098627; K23 AI 110238).

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: SWK: designed the study, conducted data collection, performed data analysis, drafted the manuscript. KAM: assisted with study design, performed data collection, revised and approved the final manuscript. SEK: assisted with study design, assisted with data interpretation, approved the final manuscript. DWF: assisted with study design, assisted with analysis and interpretation, revised and approved the final manuscript. RNP: designed the study, assisted with data analysis and interpretation, revised and approved the final manuscript. JAD: designed the study, oversaw data collection, performed data analysis, drafted the manuscript.

No authors have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Park BJ, Wannemuehler K a, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–30. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajasingham R, Meya D, Boulware D. Integrating Cryptococcal Antigen Screening and Pre-Emptive Treatment into Routine HIV Care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:85–91. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824c837e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wajanga BM, Kalluvya S, Downs JA, Johnson WD, Fitzgerald DW, Peck RN. Universal screening of Tanzanian HIV-infected adult inpatients with the serum cryptococcal antigen to improve diagnosis and reduce mortality: an operational study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:48. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouwer AE, Rajanuwong A, Chierakul W, Griffin GE, Larsen RA, White NJ, et al. Combination antifungal therapies for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1764–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291–322. doi: 10.1086/649858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. AIDS. 2007;21:2119–29. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282a4a64d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liechty CA, Solberg P, Were W, Ekwaru JP, Ransom RL, Weidle PJ, et al. Asymptomatic serum cryptococcal antigenemia and early mortality during antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:929–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, Guinness L, Bottomley C, Simms V, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2173–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Rapid Advice Diagnosis, Prevention and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV infected adults, adolescents and children. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magambo KA, Kalluvya SE, Kapoor SW, Seni J, Chofle AA, Fitzgerald DW, et al. Utility of urine and serum lateral flow assays to determine the prevalence and predictors of cryptococcal antigenemia in HIV-positive outpatients beginning antiretroviral therapy in Mwanza, Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19040. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meya DB, Manabe YC, Castelnuovo B, Cook B a, Elbireer AM, Kambugu A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of serum cryptococcal antigen screening to prevent deaths among HIV-infected persons with a CD4+ cell count < or = 100 cells/microL who start HIV therapy in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:448–55. doi: 10.1086/655143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]