Abstract

Background

There is growing interest and debate about whether an addictive process contributes to problematic eating outcomes, such as obesity. Craving is a core component of addiction, but there has been little research on the relationship between addictive-like eating, craving, and eating-related concerns. In the current study, we examine the effect of both overall food craving and craving for different types of food on the relationship between addictive-like eating symptoms and elevated body mass index (BMI) and binge eating episodes.

Methods

In a community sample (n = 283), we conducted analyses to examine whether overall craving mediated the association between addictive-like eating and elevated BMI, as well as binge eating frequency. We also ran separate mediational models examining the indirect effect of cravings for sweets, fats, carbohydrates, and fast food fats on these same associations.

Results

Overall food craving was a significant partial mediator in the relationships between addictive-like eating and both elevated BMI and binge eating episodes. Cravings for sweets and other carbohydrates significantly mediated the relationship between addictive-like eating and binge eating episodes, while cravings for fats significantly mediated the relationship between addictive-like eating and elevated BMI.

Conclusions

Craving appears to be an important component in the pathway between addictive-like eating and problematic eating outcomes. The current results highlight the importance of further evaluating the role of an addictive process in problematic eating behaviors and potentially targeting food cravings in intervention approaches.

Keywords: craving, food addiction, binge eating, BMI

1. Introduction

The theory that certain foods can trigger an addictive process has recently gained attention (Avena, Rada, & Hoebel, 2008; Davis & Carter, 2009; Gearhardt, Corbin, & Brownell, 2009; Gold, Graham, Cocores, & Nixon, 2009; Ifland et al., 2009; Pelchat, 2002), although it remains controversial (Avena, Gearhardt, Gold, Wang, & Potenza, 2012; Ziauddeen, Farooqi, & Fletcher, 2012; Ziauddeen & Fletcher, 2013). Food and drug rewards appear to act on similar neural pathways (Berridge, Ho, Richard, & DiFeliceantonio, 2010; Volkow, Wang, Fowler, & Telang, 2008), rats exhibit behaviors resembling symptoms of addiction in response to sugar consumption (Avena et al., 2008; Colantuoni et al., 2001; Rada, Avena, & Hoebel, 2005). Craving appears to play an important role in compulsive use across addictive substances, predicting negative outcomes such as increased use and earlier relapse in alcohol, cocaine, and tobacco use (Bottlender & Soyka, 2004; Donny, Griffin, Shiffman, & Sayette, 2008; Epstein, Marrone, Heishman, Schmittner, & Preston, 2010; Flannery, Poole, Gallop, & Volpicelli, 2003; Oslin, Cary, Slaymaker, Colleran, & Blow, 2009; Weiss et al., 2003). Examining the association of addictive-like eating and food craving is important to evaluating the “food addiction” hypothesis. The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) was developed to assess addictive-like eating in humans by applying DSM-IV-TR substance dependence criteria to the consumption of certain foods (Gearhardt et al., 2009). YFAS “food addiction” symptoms are related to elevated craving (Gearhardt, Rizk, & Treat, 2014; Meule & Kübler, 2012), as well as elevated BMI and more frequent binge eating episodes (Davis et al., 2011; Gearhardt, Boswell, & White, 2014). Food craving appears to be associated with eating related problems, such as binge eating and elevated body mass index (BMI) (Greeno, Wing, & Shiffman, 2000; Waters, Hill, & Waller, 2001; White & Grilo, 2005). However, fat and sugar cravings appear to have different associations with “food addiction” (Gearhardt, Rizk, et al., 2014) and obesity (Drewnowski, Kurth, Holden-Wiltse, & Saari, 1992).

To our knowledge, no prior studies have investigated whether higher food craving may be a pathway through which addictive-like eating is associated with eating-related problems and whether this differs by the type of food that is craved. In the current study, we aim to test food craving as a mediator between addictive-like eating and both BMI and binge eating episodes. Additionally, we examine whether cravings for different types of foods (sweets, carbohydrates, fats, and fast food fats) may differentially mediate these associations.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study was approved by the Yale Institutional Review Board. Participants (n=283) were drawn from a sample of 420 community volunteers and were included in this study if they provided complete data on key study measures. Participants were on average 34.9 years old (range 18-69). The sample was 15.9% male (n=45) and 83.0% female (n=235), and 3 participants did not report gender. The racial/ethnic distribution for the study sample was: 73.1% Caucasian, 9.5% Hispanic, 7.8% African American, 4.9% Asian, and 3.9% “other.” Two participants did not report race/ethnicity. The participants' body weight ranged from underweight to severely obese (BMI range 14.75 to 66.07) with the average BMI in the overweight category (M=28.44, SD = 9.00).

2.2. Assessments and Measures

Participants provided basic demographic information and completed a battery of self-report measures. Self-reported height and weight were used to compute participant BMI (kg/m2).

The Yale Food Addiction Scale (Gearhardt et al., 2009) measures signs of “addiction” towards certain types of food (e.g. high in fat, high in sugar) based on criteria for substance dependence as stated in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The YFAS “symptom count” score reflects the number of addiction-like criteria (ranging 0-7) endorsed. In the current sample, the YFAS exhibited adequate internal consistency (α=77). The mean YFAS symptom count score in the current sample was 3.02 (SD=2.00).

The Food Craving Inventory (FCI) (White, Whisenhunt, Williamson, Greenway, & Netemeyer, 2002) is a 28-item measure that assesses the frequency of cravings for specific foods. The FCI yields a score of total food craving, as well as four subscales measuring cravings for high fats (e.g., bacon), carbohydrates/starches (e.g. bread), sweets (e.g., cookies), and fast food fats (e.g., hamburgers). Total and subscale scores each have a possible range of 1-5. In the current sample, the FCI exhibited excellent internal consistency (α=95). The mean total craving score in the current sample was 2.09 (SD=0.83). Mean subscale scores were as follows: fats (M=1.75, SD=0.88), fast food fats (M=2.36, SD= 0.99), sweets (M=2.32, SD=0.99), and carbohydrates (M=1.91, SD=0.90).

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), a well-established measure of eating disorder psychopathology (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; Luce & Crowther, 1999), was used to assess the number of binge eating episodes. The item used asked participants on how many times in the past 28 days they had experienced a binge eating episode (i.e., eaten an unusually large amount of food and felt a loss of control while doing so). In the current sample, the number of binge eating episodes reported ranged from 0-28, with a mean of 2.60 (SD=5.18)

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Binge eating episodes were skewed, thus we removed four outliers (SD > 2). Age was significantly correlated with BMI (r = .303, p < .001) and was included as a covariate in all analyses.

To test the hypothesized meditational models (e.g. addictive-like eating symptoms → food craving → BMI), we followed the guidelines described by Baron and Kenny (1986). To further examine any mediational effects, we employed the bootstrapping method with 10000 samples described by Preacher and Hayes (2008). We used the completely standardized indirect effect (abcs) described by Preacher and Kelley (2011) to compare the effect sizes of statistically significant indirect effects. Effect sizes can be interpreted as small (.01), medium (.09) or large (.25) (Kenny, 2014).

3. Results

3.1. Addictive-like Eating and BMI

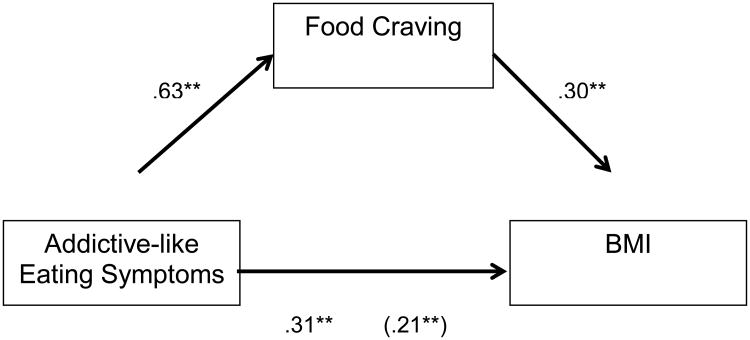

Addictive-like eating was significantly associated with both BMI and food craving (i.e., FCI - Total score), and food craving was significantly associated with BMI (see Figure 1). Food craving was a significant partial mediator between addictive-like eating and BMI (B = .46, SE = .24, 95% CI = .03-.99, abcs = .11).

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between addictive-like eating and BMI as mediated by food craving. The standardized regression coefficient between addictive-like eating and BMI controlling for food craving is in parentheses.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

3.2. Addictive-like Eating and Binge Eating Episodes

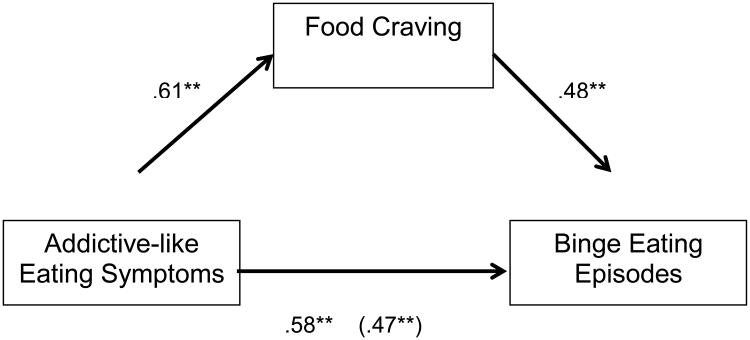

Food craving was a significant partial mediator between addictive-like eating and binge eating episodes (B = .29, SE = .14, 95% CI = .06-.62, (abcs = .12) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between addictive-like eating and binge eating episodes as mediated by food craving. The standardized regression coefficient between addictive-like eating and binge eating episodes controlling for food craving is in parentheses.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

3.3. Food Cravings for Specific Food Types

3.3.1. Fats

Fats craving was a significant partial mediator between addictive-like eating behaviors and BMI illustrated through both regression analysis (β = .155, p = .018, adj. R2 = .215) and bootstrapping (B = .31, SE = .19, 95% CI = .01 - .75, abcs = .08).

Craving for fats did not significantly predict number of binge eating episodes when addictive-like eating was included in the model (β = .108, p = .067, adj. R2 = .356) and did not significantly mediate the relationship according to bootstrapping (B = .18, SE = .10, 95% CI = -.04 - .34, abcs = .05).

3.3.2. Fast Food Fats

Craving for fast food fats did not significantly predict BMI when addictive-like eating was included (β = .098, p = .135, adj. R2 = .203) and did not significantly mediate this relationship according to bootstrapping (B = .21, SE = .14, 95% CI = -.04 - .52, abcs = .05). Craving for fast food fats also did not significantly predict number of binge eating episodes when addictive-like eating was included in the model (β = .097, p = .095, adj. R2 = .354), and did not significantly mediate this relationship according to bootstrapping (B = .11, SE = .07, 95% CI = -.01 - .27, abcs = .04).

3.3.3. Sweets

Craving for sweets did not significantly predict BMI when addictive-like eating was included in the model (β = .134, p = .067, adj. R2 = .207) and did not significantly mediate this relationship according to bootstrapping (B = .35, SE = .20, 95% CI = -.04 - .77, abcs = .09).

Sweets craving was a significant partial mediator between addictive-like eating behaviors and number of binge eating episodes illustrated through both regression analysis (β = .206, p = .001, adj. R2 = .374) and bootstrapping (B = .28, SE = .12, 95% CI = .08 - .56, abcs = .12).

3.3.4. Carbohydrates

Craving for carbohydrates did not significantly predict BMI when addictive-like eating was included in the model (β = .130, p = .060, adj. R2 = .212) and did not significantly mediate this relationship according to bootstrapping (B = .31, SE = .21, 95% CI = -.06 - .78, abcs = .08).

Carbohydrates craving was a significant partial mediator between addictive-like eating behaviors and number of binge eating episodes illustrated through both regression analysis (β = .178, p = .003, adj. R2 = .369) and bootstrapping (B = .22, SE = .12, 95% CI = .03 - .52, abcs = .09).

4. Discussion

In the current study, food craving was found to partially mediate the relationships between addictive-like eating and BMI and between addictive-like eating and number of binge eating episodes. Thus, consistent with an addiction perspective, craving appears to be an important component in the pathway between addictive-like eating and eating-related problems. Cravings for different types of foods differentially mediated the association between addictive-like eating and eating-related concerns. While many palatable foods contain high amounts of sugar and fat, these findings suggest there may be differences based on the prominence of each component in a particular food. Cravings for fats mediated the relationship between addictive-like eating and BMI, but not binge eating episodes. Fat consumption has been more closely related to weight gain and somatosensory processing than sugar, but may contribute less to behavioral outcomes related to addiction, such as binging (Avena, Rada, & Hoebel, 2009; Stice, Burger, & Yokum, 2013). Cravings for fast food fats did not significantly mediate the relationships between addictive-like eating and either BMI or binge eating episodes, possibly because this category of foods is too specific. Cravings for sweets significantly mediated the relationship between addictive-like eating and binge eating episodes, but not BMI. Sugar has been implicated in activating reward-related neural pathways and is related to the development of addictive-like eating behaviors, but not weight gain in rats (Avena et al., 2008; Stice et al., 2013). Cravings for foods high in non-sugar carbohydrates also significantly mediated the relationships between food addiction and binge eating episodes, but not BMI. Starchy carbohydrates are broken down into sugars during digestion and increase blood sugar levels (Ludwig, 2002), so it is possible that refined carbohydrates could trigger an addictive process much like sugar. Therefore, cravings for sugar or non-sugar carbohydrates appear to be more closely associated with addictive-like eating and binging, while cravings for fat appear to be more closely related to elevated BMI.

This study does have some limitations. Due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot make causal attributions. Future research should employ a longitudinal design. This sample consisted of volunteers recruited from an advertisement for a study on eating behavior and health, which could have led to some selection bias. The current sample also included mostly women, who tend to report higher rates of loss of control and binge eating (Striegel-Moore et al., 2009). These issues can be addressed in the future by replicating this study using a random and representative sample. BMI was calculated using self-reported height and weight and future studies would benefit from direct measurement of height and weight.

4.1. Conclusions

Akin to substances such as alcohol or cocaine (Bottlender & Soyka, 2004; Weiss et al., 2003), food craving appears to be associated with overconsumption in those experiencing addictive-like eating symptoms. Cravings for sweets and other high carbohydrate foods may be more closely associated with addictive-like eating behaviors such as bingeing, while cravings for fats appear to be more related to elevated BMI. Craving may be a particularly important intervention target for individuals who report greater addictive-like eating.

Highlights.

We test overall food craving as a mediator between addictive-like eating symptoms and BMI, and between addictive-like eating symptoms and binge eating episodes.

We test cravings for specific types of foods as mediators in these same relationships.

Overall craving is a significant partial mediator in both relationships.

Cravings for specific types of foods differentially mediate these relationships.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources: Partial funding for this study was provided by NIDDK Grant K23 DK071646. NIDDK had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors: Marney White designed and supervised the data collection and wrote the protocol. Michelle Joyner and Ashley Gearhardt developed the current study aims and conducted the statistical analyses. Michelle Joyner wrote the first draft of the manuscript and Ashley Gearhardt and Marney White aided in the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed text revision) Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Gearhardt AN, Gold MS, Wang GJ, Potenza MN. Tossing the baby out with the bathwater after a brief rinse? The potential downside of dismissing food addiction based on limited data. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(7):514. doi: 10.1038/nrn3212-c1. author reply 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(1):20–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Sugar and fat bingeing have notable differences in addictive-like behavior. J Nutr. 2009;139(3):623–628. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Ho CY, Richard JM, DiFeliceantonio AG. The tempted brain eats: pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1350:43–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottlender M, Soyka M. Impact of craving on alcohol relapse during, and 12 months following, outpatient treatment. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(4):357–361. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantuoni C, Schwenker J, McCarthy J, Ladenheim B, Cadet JL, Schwartz GJ, et al. Hoebel BG. Excessive sugar intake alters binding to dopamine and mu-opioid receptors in the brain. NeuroReport. 2001;12(16):3549–3552. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200111160-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Carter JC. Compulsive overeating as an addiction disorder. A review of theory and evidence. Appetite. 2009;53(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Curtis C, Levitan RD, Carter JC, Kaplan AS, Kennedy JL. Evidence that ‘food addiction’ is a valid phenotype of obesity. Appetite. 2011;57(3):711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Griffin KM, Shiffman S, Sayette MA. The relationship between cigarette use, nicotine dependence, and craving in laboratory volunteers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(3):447–455. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Kurth C, Holden-Wiltse J, Saari J. Food preferences in human obesity: carbohydrates versus fats. Appetite. 1992;18:207–221. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90198-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Marrone GF, Heishman SJ, Schmittner J, Preston KL. Tobacco, cocaine, and heroin: Craving and use during daily life. Addict Behav. 2010;35(4):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questonnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery BA, Poole SA, Gallop RJ, Volpicelli JR. Alcohol craving predicts drinking during treatment: an analysis of three assessment instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:120–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Boswell RG, White MA. The association of “food addiction” with disordered eating and body mass index. Eat Behav. 2014;15(3):427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009;52(2):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Rizk MT, Treat TA. The association of food characteristics and individual differences with ratings of craving and liking. Appetite. 2014;79:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MS, Graham NA, Cocores JA, Nixon SJ. Food addiction? Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2009;3(1):42–45. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318199cd20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeno CG, Wing RR, Shiffman S. Binge antecedents in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(1):95–102. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifland JR, Preuss HG, Marcus MT, Rourke KM, Taylor WC, Burau K, et al. Manso G. Refined food addiction: a classic substance use disorder. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72(5):518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Mediation. 2014 from http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm.

- Luce KH, Crowther JH. The reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination--Self-Report Questionnaire Version (EDE-Q) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25:349–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<349::aid-eat15>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287(18):2414–2423. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meule A, Kübler A. Food cravings in food addiction: the distinct role of positive reinforcement. Eat Behav. 2012;13(3):252–255. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Cary M, Slaymaker V, Colleran C, Blow FC. Daily ratings measures of alcohol craving during an inpatient stay define subtypes of alcohol addiction that predict subsequent risk for resumption of drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(3):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat ML. Of human bondage: food craving, obsession, compulsion, and addiction. Physiol Behav. 2002;76:347–352. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect Size Measures for Mediation Models: Quantitative Strategies for Communicating Indirect Effects. Psychological Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658.supp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rada P, Avena NM, Hoebel BG. Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell. Neuroscience. 2005;134(3):737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burger KS, Yokum S. Relative ability of fat and sugar tastes to activate reward, gustatory, and somatosensory regions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(6):1377–1384. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.069443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Rosselli F, Perrin N, DeBar L, Wilson GT, May A, Kraemer HC. Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(5):471–474. doi: 10.1002/eat.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Telang F. Overlapping neuronal circuits in addiction and obesity: evidence of systems pathology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1507):3191–3200. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters A, Hill A, Waller G. Internal and external antecedents of binge eating episodes in a group of women with bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29:17–22. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<17::aid-eat3>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mazurick C, Berkman B, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, et al. Moras K. The relationship between cocaine craving, psychosocial treatment, and subsequent cocaine use. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1320–1325. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Grilo CM. Psychometric properties of the Food Craving Inventory among obese patients with binge eating disorder. Eat Behav. 2005;6(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Whisenhunt BL, Williamson DA, Greenway FL, Netemeyer RG. Development and validation of the Food-Craving Inventory. Obesity Research. 2002;10(2):107–114. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziauddeen H, Farooqi IS, Fletcher PC. Obesity and the brain: how convincing is the addiction model? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(4):279–286. doi: 10.1038/nrn3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziauddeen H, Fletcher PC. Is food addiction a valid and useful concept? Obes Rev. 2013;14(1):19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]