Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune disease, characterized by a dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophagus, leading to bolus impaction and reflux-like symptoms. Traditionally considered a pediatric disease, the number of adult patients with EoE is continuously increasing, with a relatively higher incidence in western countries. Dysphagia and food impaction represent the main symptoms complained by patients, but gastroesophageal reflux-like symptoms may also be present. Esophageal biopsies are mandatory for the diagnosis of EoE, though clinical manifestations and proton pump inhibitors responsiveness must be taken into consideration. The higher prevalence of EoE in patients suffering from atopic diseases suggests a common background with allergy, however both the etiology and pathophysiology are not completely understood. Elimination diets are considered the first-line therapy in children, but this approach appears less effective in adults patients, who often require steroids; despite medical treatments, EoE is complicated in some cases by esophageal stricture and stenosis, that require additional endoscopic treatments. This review summarizes the evidence on EoE pathophysiology and illustrates the safety and efficacy of the most recent medical and endoscopic treatments.

Keywords: Eosinophilic esophagitis, Eotaxin, Immune system, Proton pump inhibitors-responsive eosinophilia, Endoscopic dilation

Core tip: Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune disease, characterized by a dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophagus, leading to bolus impaction and reflux-like symptoms. The pathophysiology of this entity is still unclear, however the involvement of both genetic and immune factors have been suggested. In this review we summarize the evidence on EoE pathophysiology and illustrate the safety and efficacy of the most recent medical and endoscopic treatments.

INTRODUCTION

The eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune disease, characterized by a dense eosinophilic infiltrate into the esophagus. Dysphagia and food impaction episodes are recognized as the main symptoms of EoE in adults, however regurgitation, chest pain and heartburn may also be referred[1].

Considered as a pediatric disease until few years ago, it is now clear that EoE may also occur in adults, especially young Caucasian man[2]. A rapid increase of incidence in the last decades has been registered, however a retrospective study[3] on biopsies collected between 1982 and 1999 revealed that the incidence of EoE appears stable, suggesting that the higher rate of new diagnosis depends, almost in part, on the improved disease recognition. African, West Asian and South American population share a low prevalence rate, but the real incidence of EoE in these countries remains unclear[4,5].

The EoE-symptoms pattern is heterogeneous and although dysphagia and food impaction are frequently reported, patients may also complain of typical and atypical gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, leading to a delay in the diagnosis.

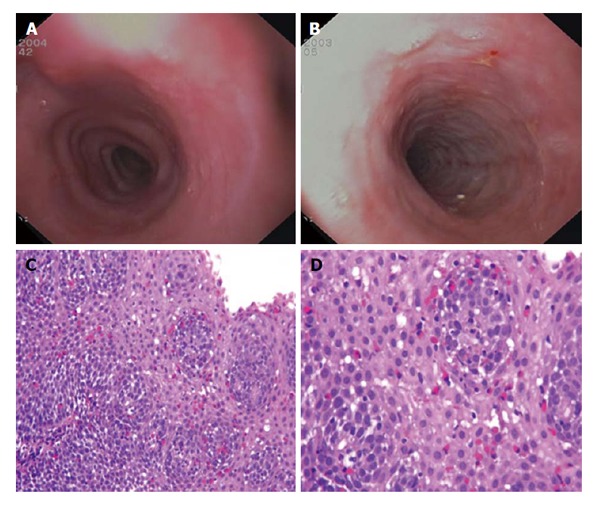

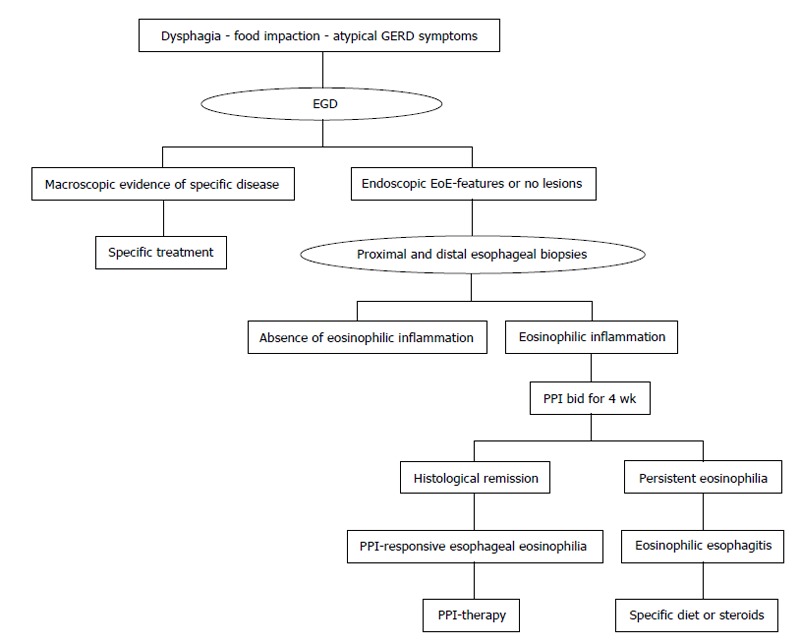

Endoscopic features, such as esophageal rings, white exudates or plaques, longitudinal furrows, diffuse esophageal narrowing, and mucosal fragility, may help the diagnosis, but histological identification of predominant eosinophilic-inflammation, with more than 15 eosinophils for high power field, represents the main diagnostic criterion for EoE (Figure 1 and Table 1). Nevertheless, the histological evidence of esophageal eosinophilia in a subset of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) responder patients further complicates the diagnosis. Previously considered a GERD-subtype, actually, PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) is considered a different entity, not distinguishable from EoE[1,6]; in the Figure 2 it is summarized the diagnostic algorithm in case of suspected EoE.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic and microscopic findings in eosinophilic esophagitis. A: Esophageal rings; B: White exudates, longitudinal furrows and mucosal fragility; C and D: Esophageal mucosa infiltrated by several eosinophils (red cells) (C: Original magnification HE 150 ×; D: HE 400 ×).

Table 1.

Endoscopic and histological features of eosinophilic esophagitis

| Endoscopic features |

| Esophageal rings |

| White exudates or plaques |

| Longitudinal furrows |

| Diffuse esophageal narrowing |

| Mucosal fragility |

| Histological features |

| Eosinophilic infiltration (≥ 15 eos/hpf) |

| Eosinophilic degranulation |

| Basal zone hyperplasia |

| Eosinophilic micro-abscesses |

| Spongiosis or dilated intercellular spaces |

| Intramucosal lymphocytes |

Figure 2.

Diagnostic flow-chart of eosinophilic esophagitis. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; EoE: Eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI: Proton pump inhibitors; EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

The pathogenesis of EoE is unknown, but it is supposed to be multifactorial with genetic, immunologic and environmental factors being all involved. There is evidence that EoE is more prevalent in patients suffering from food-allergy, rhinitis, asthma or atopic dermatitis[7,8]. Interestingly, all these pathologies share an altered immune response to common antigens, which determinates an aberrant Th2-response, and, hence, the uncontrolled activation of eosinophils, mast cells and basophils[9-13].

Specific allergy testing, or empiric elimination diets represent the first line therapy in children with EoE[1,14]. Topical corticosteroids are considered the mainstay of therapy for adult patients[1,15], while systemic steroids are reserved to patients with persistent eosinophilia[1]. Besides its central role in the diagnosis of EoE, endoscopy has also of great impact on the treatment of EoE fibrotic complications[1,16].

This review summarizes the most recent evidence on the pathogenesis of EoE, focusing on the role of genetic and immunologic factors and illustrates the safety and efficacy of the most recent medical and endoscopic treatments.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Genetic factors

The higher risk of EoE in familiars of affected patients supports the hypothesis of genetic predisposition. The latest familial study[17] estimated that 2.4% of proband siblings’ also had EoE, with a 40-folds higher risk, than general population.

The incidence of EoE is higher in monozygotic twins (41%), but the observation that the disease also occurs in 21% of dizygotic twins suggests a role for environmental factors, especially in the early-life[17]; by using a complex statistical model it has been estimated that the contribution to the familiar risk depends by hereditability and exposure to common environment for 14.5% and 80%, respectively[17].

Three different approaches have been used to identify the genes involved in EoE predisposition: The association with Mendelian syndromes, the search for a specific gene and the genome-wide association studies[18] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic factors involved in eosinophilic esophagitis

| Genes | Encoded protein | Mechanism of action | Ref. |

| Mendelian syndromes | |||

| FBN1 (Marfan syndrome) | Fibrillin | Alteration of TGF-β pathway | [19] |

| COL (Elher-Danlos syndrome) | Collagen | Alteration of TGF-β pathway | [19] |

| TGFBR (Loeys-Dietz syndrome) | TGF-β-promoters | Alteration of TGF-β pathway | [21] |

| STAT3 (Iper-IgE syndrome) | Transcription activator 3 | Aberrant cytokines production | [18] |

| DSG1 (SAM) | Desmoglein1 | Loss of cell-cell adhesion | [23] |

| EoE-associated genetic variants | |||

| CCL26 | Eotaxin-3 | Eosinophilic chemo-attraction | [25] |

| FLG | Filaggrin | Epithelium-ECM interaction | [18] |

| TSLP (5q22) | TSLP | Basophils chemo-attraction | [28,29] |

| CAPN14 | Calpain 14 | Proteolytic effects | [28] |

TGF: Transforming growth factor; ECM: Extracellular matrix; SAM: Severe atopic dermatitis, multiple allergies and metabolic syndrome.

An increased prevalence of EoE has been reported in patients affected by hypermobile connective tissue diseases, like Marfan, Ehler-Danlos and Loeys-Dietz Syndromes; interestingly, these pathologies are characterized by a defective transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathway, and the observation that this factor is increased in the esophagus of both syndromic and not EoE likely supports its causative role[19-21]. A major risk of EoE has been also described in some pro-allergenic Mendelian diseases, like the “Iper-IgE syndrome”[18] and an autosomal dominant disease belong to Mast-cell Activation syndromes, characterized by high levels of mast cell tryptase, this association strongly suggests the pathogenic association between EoE and atopic diseases[22]. This concept is further supported by the association between EoE and a rare syndrome characterized by severe atopic dermatitis, multiple allergies and metabolic syndrome (SAM); this syndrome is characterized by a mutation of desmoglein-1 gene’s[18,23], whose expression is significantly reduced in idiopathic EoE[24].

Candidate-gene identification studies allowed identifying the putative factors associated with EoE in non-Mendelian syndromes. A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the gene CCL26, encoding for the eotaxin-3, was associated with EoE[25]. This protein is overexpressed in esophageal epithelial cells of affected patients, and plays an important role in the chemotaxis of eosinophils[26,27]. Similarly, a SNP in the gene encoding for the filagrin, a structural membrane protein involved in epithelial cells-extracellular matrix interaction has also been identified[18]. Several genes were found to be associated with EoE by genoma wide association studies. In one of the most recent report[28] a significant association between a locus on 5q22, encoding for the cytokine thymic stromal limphopoietin (TSLP) and EoE was reported. Although the specific mechanism remains, yet, to be clarified, TSLP has been demonstrated to have a pivotal role in the activation of basophils in human and animal models of EoE[29,30]. In the same study[28] also the CAPN14 gene, encoding for the calpain subfamily of proteolytic systems, was identified; more precisely this protein, that is specifically expressed by epithelial cells of the esophagus, is activated by interleukin (IL)-13 and participates to inflammatory process[28].

Immune system factors

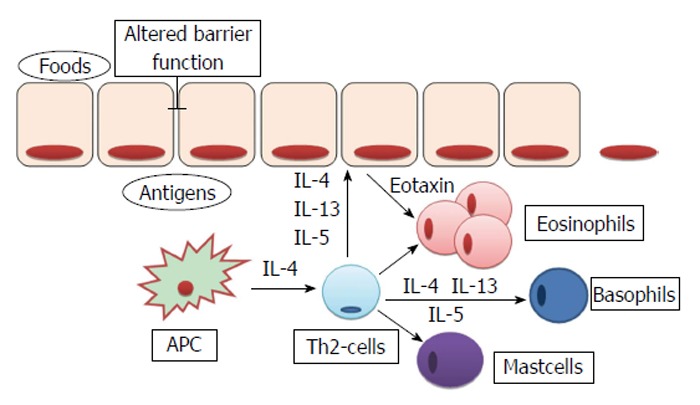

The EoE is characterized by a prevalent eosinophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria and submucosa of the esophagus. The precise mechanisms of such localized inflammatory reactions are not recognized yet, but it is suggested that different cytokines are involved in the maturation and migration of eosinophils. In particular, IL-5, IL-13 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor are produced by different cell types, included esophageal epithelial cells, after an appropriate stimulation by the antigen-presenting cells (APCs)[31]. As shown in Figure 3, the evidence that in EoE patients there is desmoglein-1-dependent altered barrier function[23] have led some authors to hypothesize that the increased permeability of esophageal epithelium could facilitate the passage of different antigens, that causes the activation of APCs and invariant natural killer T-cells. These cells, if properly stimulated, are able to prime a Th2 immune response, by the production of IL-13 and IL-4[32]. However, whether the barrier impairment represents a primum movens, or an epiphenomenon in the context of the eosinophilic-inflammation remains unclear. Sherrill et al[33] have demonstrated that esophageal epithelial cells express toll-like receptors, whose antigens-mediated activation, through the production of IL-5 and IL-13[34], is able to trigger a Th2-response with the production of other cytokines and the proliferation of eosinophils, T-cells, mast cells and basophils[31].

Figure 3.

Pathophysiological mechanism involved in eosinophilic infiltration of esophageal mucosa. IL: Interleukin; APC: Antigen-presenting cell.

The increased release of these cytokines in both the esophagus and the blood of EoE patients has been demonstrated in different studies[35,36], and, although need to be further clarified, their role in the pathogenesis of EoE appears to be fundamental.

IL-4 and IL-13 are able to prolong the T-cell survival and to increase eosinophilic migration through the release of Eotaxin-3 and TSLP by epithelial cells[37]; recently, Zhu et al[38] found that IL-15 is also enhanced in EoE and, most interestingly, they demonstrated that IL-15 receptor deficient mice are protected from EoE, but not from other allergic diseases, supporting a specific role of IL-15 in the “allergic-pathway” of esophagus. Although the eosinophilic infiltration represents the main characteristic, it is of relevance that other immune cells, like basophils and mast cells, are also involved in the pathogenesis of EoE and they likely contribute to the amplification of the esophageal inflammatory response and mucosal damage[18,20,29].

Mechanisms of mucosal damage and fibrosis

Food impaction and dysphagia are the main symptoms in patients with EoE and these are a direct consequence of the esophageal mucosa remodeling and fibrosis.

Eosinophils synthetize and release many proteins and mediators, in particular major basic protein (MBP), eosinophil cationic protein, eosinophil peroxidase, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, TGF-β, IL-13 and platelet-activating factor. Although all these mediators play a key role in the tissue damage and remodeling, the most robust data are about MBP and TGF-β[37].

MBP is able to directly damage epithelial cells, but also to induce mast cells degranulation, increasing the release of proteolytic enzymes, tryptase and chymase, that further participate to the deconstruction of the extracellular matrix[39]; MBP is also able to stimulate the production of fibroblast growth factor-9, leading to fibroblasts proliferation and activation[40]. Similarly, TGF-β induces both fibroblasts activation and contraction, causing their transformation into myo-fibroblasts[41]; in addition at high concentration TGF-β stimulates epithelial cells to assume phenotypical characteristic of fibroblasts, a process named epithelial-mesenchymal transition[42]. These mechanisms act synergistically, determining the altered synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen, tenascin-C and metalloproteinases[43]. In recent studies the periostin, that is highly expressed in the esophagus of EoE patients, has been proposed as a major determinant of extracellular matrix alteration and epithelial barrier function impairment, because of its ability to determine collagen cross-linking and to bind several matrix proteins and integrins[44].

As mentioned above, other immune cells rather than eosinophils participate to the inflammatory response described in the EoE; recently, the ability of epithelial and mesenchymal cells to synthetize and release different molecules has been also suggested to contribute to tissue damage[12,20,45]. In addition, some authors found a correlation between the inflammatory cells infiltrate and enteric neurons alterations, but the role of enteric nervous system impairment in the process of mucosal damage has not been clarified, yet[46].

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

The “3 D-approach” summarizes the three major treatments for EoE: Diet, drugs and dilation. Although clinical remission represents a good parameter to evaluate the effectiveness of therapy, the endoscopic and histological response is required. The main endpoint of diet and drug therapies is the resolution of both symptoms and inflammation, however the complete remission is rare, and the relief of esophageal symptoms in association with a significant reduction of mucosal eosinophilia should be considered a good response[1].

Dietary therapy

Specific dietary approaches are considered the first-line therapy in the treatment of EoE in children, due to the lack of adverse effects and the high rate of response. Three different dietary patterns may be used: (1) elemental diet; (2) allergy test-based diet; and (3) empiric elimination diet[47].

The elemental diet demonstrates the high rate of response (almost 90% in children, 70% in adults), with a rapid relief of symptoms associated with histological remission. This diet contemplates the use of amino-acid based liquid formulas for 4-6 wk, followed by the histological evaluation of response. If the remission is achieved, foods are slowly reintroduced, following a strict scheme which contemplates four different food groups, based on their allergenic potential. A single food of each group should be reintroduced every 5-7 d; in absence of symptoms’ recurrence, the endoscopic and histological evaluation should be performed before starting the reintroduction of foods from another group. If a specific food determinates esophageal symptoms, it should be excluded and the next food of the same group tested. Despite the high rate of response, this diet is rarely accepted by patients[48,49].

The allergic-test driven diets showed a rate of response of 70% in children, using the combination of both skin prick and patch tests to identify trigger-foods; this dietary pattern allows the elimination of specific foods, enhancing the compliance, however atopy patch test are not universally accepted for food allergy[50,51]. Moreover, given that the rate of response to this diet in adults is lower, this approach is not recommended in this patients.

The empiric diets, instead, are based on the exclusion of the most allergenic foods, such as cow’s milk protein, soy, wheat, egg, peanut/tree nut, and fish/shellfish, independently on allergic tests. This dietary therapy has shown a rate of response of almost 70% in both children and adults. However, if the remission is achieved, an endoscopic and histological evaluation should be performed after the reintroduction of each food[52,53].

In conclusion, although the exclusion of trigger-foods allows a long-term remission without drugs, the high cost of such diets, especially aminoacid based-formulas, the poor compliance and the need for multiple endoscopies, represent important disadvantages for dietary therapy.

Corticosteroids

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisolone or methylprednisolone, in the remission of both symptoms and eosinophilic infiltration, however the recurrence after the tapering is usually observed. Long-term therapy with corticosteroids is limited by the important adverse effects, hence systemic steroids may be used to rapidly induce remission, but a different maintenance therapy has to be set[54]. Topical steroids, in particular fluticasone and budesonide, have shown a good rate of response, reducing adverse effects also during long-term treatment[55,56]. Due to the lack of specific dispenser, multidose inhalers should be used, and patients have to be instructed to swallow, rather than inhale, the product[57]. A viscous compound of budesonide and sucralose, has also been tested, obtaining excellent results[58]. Topical steroids have shown a good safety profile, and are actually considered the first-line therapy, after the PPI trial, in EoE patients. However, some cases of esophageal candidiasis and herpes infections have been described[59,60].

PPI

When the first consensus guidelines for EoE was published in 2007, a physiological 24h-pH-metry and the persistence of symptoms despite PPI therapy were considered major criteria for diagnosis of EoE. In the last years, several studies have shown that almost 40% of patients with clinical, endoscopic and histological features of EoE responds to PPI therapy, independently on the results of 24 h-pH-metry[61,62].

These data questioned the relationship between GERD and EoE, introducing a novel entity, named PPI-REE, in the consensus of 2011[63]. Actually considered more a subtype of EoE, rather than atypical GERD, this pathology is defined by the presence of all hallmarks (clinical, endoscopic and histological) of EoE, associated with a complete (clinical, endoscopic and histological) remission during PPI therapy[1]. Considering that different studies have demonstrated that patients with PPI-REE share the same genetic and phenotypic background of EoE-subjects, nowadays PPI bid is considered the first-line therapy in all patients with EoE features[1,64].

PPI-REE opened a new field of research, focused on the role of reflux in the pathogenesis of esophageal eosinophilia[65]. The hypothesis that gastroesophageal reflux, even if not pathologic, could enhance epithelial barrier dysfunction, allowing the passage of multiple antigens through the mucosa, has been proposed and evaluated. Different studies have demonstrated that gastric reflux is able to enlarge intracellular space, and the increased transit of molecules through esophageal epithelium has also been observed in both GERD and EoE[66,67]. Accordingly, the exposition of several antigens to APC may induce, in predisposed subjects, a cascade of events, triggering a Th2-response, and, consequently, the eosinophilic infiltration. In this case the therapeutic effects of PPIs, will depend on their ability to favorite the regeneration of epithelial barrier, reducing the antigen exposition and, hence, the amplification of immune response.

According to others, also GERD, as EoE, represents an immune-mediated pathology, in which acid reflux stimulates the release of cytokines, inducing a specific Th1-response. Therefore, the activation of immune system and the production of toxic mediators determinates mucosal erosions, rather than the direct caustic action of acid[68]. These authors suggest that in “atopic-subjects”, the typical response to acid reflux switch to a Th2-response, causing an EoE-like damage of the esophagus. Therefore, the reduction of immunogenic trigger, by the inhibition of acid secretion, will determinate the resolution of damage. Furthermore, a direct anti-inflammatory effect of PPIs has been recently demonstrated. In particular, different studies have pointed out the reduction of eotaxin 3 and Th2-mediators, after treatment with PPI in the mucosa of patients with diagnosis of both EoE and PPI-REE. These events have been observed both in vitro and in vivo experiments, suggesting that PPIs anti-inflammatory action is acid-independent[69-71].

Summarizing, at the baseline, is not possible to discriminate between EoE and PPI-REE, and, although the probability of PPI response in patients with pathologic 24 h-pH-metria is higher, PPIs trial still represents the only instrument to differentiate these entities (Figure 2)[72,73].

Other pharmacological treatments

Given the association with other atopic diseases, leukotriene antagonist and mast cells stabilizers, such as montelukast and cromolym, have been tested in the treatment of EoE, however all studies showed a poor efficacy of these drugs in both symptomatic and histological remission[74].

Specific antibodies against IL-5 and IgE were also tested, especially for treating steroid-refractory patients. However, despite the initial promising results, the controlled clinical trials have shown a similar response in treated and placebo subgroups[75-78]. Interestingly, a recent trial testing a human antibody against IL-13 showed a significant improvement of symptoms and eosinophilic infiltration, however the primary endpoint, the reduction of 75% of esophageal eosinophils, have been not achieved[79].

The failure of such specific therapy likely depends on the redundancy, in fact multiple cytokines share similar effects, allowing the persistence of inflammation after the blockage of single molecules.

Endoscopic treatment

Due to the fibro-stenotic evolution, strictures are frequently found in patients affected by EoE, hence endoscopic dilation have a key role in the treatment of this entity[1]. Several studies have shown the efficacy and safety of esophageal dilation, independently on the chosen technique. Wire-guided bougies, through-the-scope balloons, and non-wire-guided bougies have been indistinctly used[80,81]. Nowadays, there are not available data on the best endoscopic technique, because comparing studies are lacking.

Due to the long-term efficacy of this procedure in the treatment of EoE-related dysphagia, some authors have proposed dilation as initial therapy, however a recent study have demonstrated that fluticasone inhaler, followed by dilation if necessary, is the most economical initial strategy. Moreover, although dilation rapidly improve symptoms, this procedure did not influenced esophageal inflammation, hence further therapies should be set after the treatment[82].

CONCLUSION

EoE represents a multifactorial disease, in which both genetic predisposition and environmental factors contribute to disease manifestations. Although in the last years many studies have been performed, its pathophysiology remains unclear, likely reflecting the heterogeneity of disease phenotype.

The EoE-symptoms pattern is heterogeneous, dysphagia and food impaction are frequently referred, however also atypical GERD symptoms may be reported. The histological identification of a prevalent eosinophilic esophageal infiltrate represents the major diagnostic criterion for EoE, however only the PPI-trial allows to distingue EoE from PPI-REE.

The good response to diet therapy in children, supports the role of food as a major trigger factor, leading to define EoE a subtype of food-allergy. For this reason, elimination diets and corticosteroids represent the mainstay of EoE-therapy, while endoscopic dilation have a key role in the treatment of fibrotic complication.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Hokama A S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 28, 2015

First decision: July 27, 2015

Article in press: September 28, 2015

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA; DAM American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:679–92; quiz 693. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBrosse CW, Collins MH, Buckmeier Butz BK, Allen CL, King EC, Assa’ad AH, Abonia JP, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME, Franciosi JP. Identification, epidemiology, and chronicity of pediatric esophageal eosinophilia, 1982-1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishimura N, Shimura S, Jiao D, Mikami H, Okimoto E, Uno G, Aimi M, Oshima N, Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y. Clinical features of eosinophilic esophagitis: differences between Asian and Western populations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30 Suppl 1:71–77. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiler T, Mikhail I, Singal A, Sharma H. Racial differences in the clinical presentation of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asher Wolf W, Dellon ES. Eosinophilic esophagitis and proton pump inhibitors: controversies and implications for clinical practice. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2014;10:427–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, Thien F, Gibson PR. Risk factors for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:1012–1019. doi: 10.1111/cea.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virchow JC. Eosinophilic esophagitis: asthma of the esophagus? Dig Dis. 2014;32:54–60. doi: 10.1159/000357010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon D, Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis and allergy. Dig Dis. 2014;32:30–33. doi: 10.1159/000357006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straumann A, Bauer M, Fischer B, Blaser K, Simon HU. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T(H)2-type allergic inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:954–961. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucendo AJ. Cellular and molecular immunological mechanisms in eosinophilic esophagitis: an updated overview of their clinical implications. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:669–685. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.909727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieder F, Nonevski I, Ma J, Ouyang Z, West G, Protheroe C, DePetris G, Schirbel A, Lapinski J, Goldblum J, et al. T-helper 2 cytokines, transforming growth factor β1, and eosinophil products induce fibrogenesis and alter muscle motility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1266–77.e1-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdulnour-Nakhoul SM, Al-Tawil Y, Gyftopoulos AA, Brown KL, Hansen M, Butcher KF, Eidelwein AP, Noel RA, Rabon E, Posta A, et al. Alterations in junctional proteins, inflammatory mediators and extracellular matrix molecules in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Immunol. 2013;148:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arias A, Lucendo AJ. Dietary therapies for eosinophilic esophagitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:133–142. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.856263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander JA. Steroid treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:357–373. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1238–1254. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander ES, Martin LJ, Collins MH, Kottyan LC, Sucharew H, He H, Mukkada VA, Succop PA, Abonia JP, Foote H, et al. Twin and family studies reveal strong environmental and weaker genetic cues explaining heritability of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1084–1092.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothenberg ME. Molecular, genetic, and cellular bases for treating eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1143–1157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abonia JP, Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan T, Griffith MS, Kemme KA, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Franciosi JP, von Tiehl KF, et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng E, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Tissue remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1175–G1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00313.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Guerrerio AL, Oswald G, Chichester K, Myers L, Halushka MK, Oliva-Hemker M, Wood RA, Dietz HC. TGFβ receptor mutations impose a strong predisposition for human allergic disease. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:195ra94. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyons JJ, Sun G, Stone KD, Nelson C, Wisch L, O’Brien M, Jones N, Lindsley A, Komarow HD, Bai Y, et al. Mendelian inheritance of elevated serum tryptase associated with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1471–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuelov L, Sarig O, Harmon RM, Rapaport D, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Isakov O, Koetsier JL, Gat A, Goldberg I, Bergman R, et al. Desmoglein 1 deficiency results in severe dermatitis, multiple allergies and metabolic wasting. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1244–1248. doi: 10.1038/ng.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherrill JD, Kc K, Wu D, Djukic Z, Caldwell JM, Stucke EM, Kemme KA, Costello MS, Mingler MK, Blanchard C, et al. Desmoglein-1 regulates esophageal epithelial barrier function and immune responses in eosinophilic esophagitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:718–729. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, Jameson SC, Kirby C, Konikoff MR, Collins MH, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–547. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiwara H, Morita A, Kobayashi H, Hamano K, Fujiwara Y, Hirai K, Yano M, Naka T, Saeki Y. Infiltrating eosinophils and eotaxin: their association with idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:429–432. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, Caldwell JM, Collins MH, Ahrens A, Buckmeier BK, Jameson SC, Greenberg A, Kaul A, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4033–4041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kottyan LC, Davis BP, Sherrill JD, Liu K, Rochman M, Kaufman K, Weirauch MT, Vaughn S, Lazaro S, Rupert AM, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:895–900. doi: 10.1038/ng.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noti M, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Giacomin PR, Nair MG, Benitez AJ, Ruymann KR, Muir AB, Hill DA, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1005–1013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cianferoni A, Spergel J. The importance of TSLP in allergic disease and its role as a potential therapeutic target. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:1463–1474. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.967684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Foster PS. Eosinophils: changing perspectives in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nri3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jyonouchi S, Smith CL, Saretta F, Abraham V, Ruymann KR, Modayur-Chandramouleeswaran P, Wang ML, Spergel JM, Cianferoni A. Invariant natural killer T cells in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:58–68. doi: 10.1111/cea.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherrill JD, Gao PS, Stucke EM, Blanchard C, Collins MH, Putnam PE, Franciosi JP, Kushner JP, Abonia JP, Assa’ad AH, et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:160–5.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim DM, Narasimhan S, Michaylira CZ, Wang ML. TLR3-mediated NF-{kappa}B signaling in human esophageal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1172–G1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00065.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhardwaj N, Ghaffari G. Biomarkers for eosinophilic esophagitis: a review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konikoff MR, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Buckmeier BK, Cohen MB, Heubi JE, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Potential of blood eosinophils, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, and eotaxin-3 as biomarkers of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1328–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Travers J, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophils in mucosal immune responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:464–475. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X, Wang M, Mavi P, Rayapudi M, Pandey AK, Kaul A, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME, Mishra A. Interleukin-15 expression is increased in human eosinophilic esophagitis and mediates pathogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:182–93.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gleich GJ, Frigas E, Loegering DA, Wassom DL, Steinmuller D. Cytotoxic properties of the eosinophil major basic protein. J Immunol. 1979;123:2925–2927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulder DJ, Pacheco I, Hurlbut DJ, Mak N, Furuta GT, MacLeod RJ, Justinich CJ. FGF9-induced proliferative response to eosinophilic inflammation in oesophagitis. Gut. 2009;58:166–173. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaughan MB, Howard EW, Tomasek JJ. Transforming growth factor-beta1 promotes the morphological and functional differentiation of the myofibroblast. Exp Cell Res. 2000;257:180–189. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piera-Velazquez S, Li Z, Jimenez SA. Role of endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1074–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts AB, McCune BK, Sporn MB. TGF-β: Regulation of extracellular matrix. Kidney International. 1999;41:557–559. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, McBride M, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Chang G, Stringer K, Abonia JP, Molkentin JD, Rothenberg ME. Periostin facilitates eosinophil tissue infiltration in allergic lung and esophageal responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:289–296. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flavahan NA, Slifman NR, Gleich GJ, Vanhoutte PM. Human eosinophil major basic protein causes hyperreactivity of respiratory smooth muscle. Role of the epithelium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:685–688. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hogan SP, Mishra A, Brandt EB, Royalty MP, Pope SM, Zimmermann N, Foster PS, Rothenberg ME. A pathological function for eotaxin and eosinophils in eosinophilic gastrointestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:353–360. doi: 10.1038/86365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vashi R, Hirano I. Diet therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis: when, why and how. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:407–415. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328362285d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, Ying J, Boynton KK, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, Adler DG, Clayton F. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:759–766. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peterson KA, Boynton KK. Which patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) should receive elemental diets versus other therapies? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16:364. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0364-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spergel JM, Andrews T, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Liacouras CA. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with specific food elimination diet directed by a combination of skin prick and patch tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:336–343. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ballmer-Weber BK. Value of allergy tests for the diagnosis of food allergy. Dig Dis. 2014;32:84–88. doi: 10.1159/000357077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodríguez-Sánchez J, Gómez Torrijos E, López Viedma B, de la Santa Belda E, Martín Dávila F, García Rodríguez C, Feo Brito F, Olmedo Camacho J, Reales Figueroa P, Molina-Infante J. Efficacy of IgE-targeted vs empiric six-food elimination diets for adult eosinophilic oesophagitis. Allergy. 2014;69:936–942. doi: 10.1111/all.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, González-Cervera J, Yagüe-Compadre JL, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, Jiménez-Contreras S, González-Castillo S, Rodríguez-Domíngez B, De Rezende LC, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukkada VA, Furuta GT. Management of refractory eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis. 2014;32:134–138. doi: 10.1159/000357296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Contreras EM, Gupta SK. Steroids in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, Lim JD, Steiner SJ, Gupta SK. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, Kirby C, Jameson SC, Buckmeier BK, Akers R, Cohen MB, Collins MH, Assa’ad AH, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zur E. Eosinophilic esophagitis: treatment with oral viscous budesonide. Int J Pharm Compd. 2012;16:288–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gupta SK, Vitanza JM, Collins MH. Efficacy and safety of oral budesonide suspension in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:66–76.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuang MY, Chinnaratha MA, Hancock DG, Woodman R, Wong GR, Cock C, Fraser RJ. Topical Steroid Therapy for the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e82. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molina-Infante J, Katzka DA, Dellon ES. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia: a historical perspective on a novel and evolving entity. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munday W, Zhang X. Proton pump inhibitor responsive esophageal eosinophilia, a distinct disease entity? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10419–10424. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.e6; quiz 21-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wen T, Dellon ES, Moawad FJ, Furuta GT, Aceves SS, Rothenberg ME. Transcriptome analysis of proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia reveals proton pump inhibitor-reversible allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Katzka DA. The complex relationship between eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2014;32:93–97. doi: 10.1159/000357080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katzka DA, Ravi K, Geno DM, Smyrk TC, Iyer PG, Alexander JA, Mabary JE, Camilleri M, Vaezi MF. Endoscopic Mucosal Impedance Measurements Correlate With Eosinophilia and Dilation of Intercellular Spaces in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1242–1248.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weijenborg PW, Smout AJ, Verseijden C, van Veen HA, Verheij J, de Jonge WJ, Bredenoord AJ. Hypersensitivity to acid is associated with impaired esophageal mucosal integrity in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease with and without esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G323–G329. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00345.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Souza RF, Huo X, Mittal V, Schuler CM, Carmack SW, Zhang HY, Zhang X, Yu C, Hormi-Carver K, Genta RM, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux might cause esophagitis through a cytokine-mediated mechanism rather than caustic acid injury. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1776–1784. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park JY, Zhang X, Nguyen N, Souza RF, Spechler SJ, Cheng E. Proton pump inhibitors decrease eotaxin-3 expression in the proximal esophagus of children with esophageal eosinophilia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molina-Infante J, Rivas MD, Hernandez-Alonso M, Vinagre-Rodríguez G, Mateos-Rodríguez JM, Dueñas-Sadornil C, Perez-Gallardo B, Ferrando-Lamana L, Fernandez-Gonzalez N, Bañares R, et al. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia correlates with downregulation of eotaxin-3 and Th2 cytokines overexpression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:955–965. doi: 10.1111/apt.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang X, Cheng E, Huo X, Yu C, Zhang Q, Pham TH, Wang DH, Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Omeprazole blocks STAT6 binding to the eotaxin-3 promoter in eosinophilic esophagitis cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kia L, Hirano I. Distinguishing GERD from eosinophilic oesophagitis: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:379–386. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Warners MJ, van Rhijn BD, Curvers WL, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia cannot be distinguished from eosinophilic esophagitis by endoscopic signs. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:506–511. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kern E, Hirano I. Emerging drugs for eosinophilic esophagitis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2013;18:353–364. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2013.829039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cianferoni A, Spergel JM. Immunotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:321–331. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Otani IM, Anilkumar AA, Newbury RO, Bhagat M, Beppu LY, Dohil R, Broide DH, Aceves SS. Anti-IL-5 therapy reduces mast cell and IL-9 cell numbers in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1576–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, Smith DA, Patel J, Byrne M, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010;59:21–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stein ML, Collins MH, Villanueva JM, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Buckmeier BK, Filipovich AH, Assa’ad AH, Rothenberg ME. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1312–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, Nadeau K, Kaiser S, Peters T, Perez A, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bohm ME, Richter JE. Review article: oesophageal dilation in adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:748–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schoepfer A. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis by dilation. Dig Dis. 2014;32:130–133. doi: 10.1159/000357091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kavitt RT, Penson DF, Vaezi MF. Eosinophilic esophagitis: dilate or medicate? A cost analysis model of the choice of initial therapy. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:418–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]