Background: PHD-histone interactions are essential in epigenetic signaling.

Results: Calixarenes can disrupt PHD-H3K4me complexes in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusion: The inhibitory activity of calixarenes depends on the binding affinities of PHD fingers for H3K4me and the methylation state of histone.

Significance: This approach provides new tools for probing histone binding activities of methyllysine readers.

Keywords: chromatin, histone, histone methylation, inhibitor, PHD finger, calixarene

Abstract

Plant homeodomain (PHD) finger-containing proteins are implicated in fundamental biological processes, including transcriptional activation and repression, DNA damage repair, cell differentiation, and survival. The PHD finger functions as an epigenetic reader that binds to posttranslationally modified or unmodified histone H3 tails, recruiting catalytic writers and erasers and other components of the epigenetic machinery to chromatin. Despite the critical role of the histone-PHD interaction in normal and pathological processes, selective inhibitors of this association have not been well developed. Here we demonstrate that macrocyclic calixarenes can disrupt binding of PHD fingers to methylated lysine 4 of histone H3 in vitro and in vivo. The inhibitory activity relies on differences in binding affinities of the PHD fingers for H3K4me and the methylation state of the histone ligand, whereas the composition of the aromatic H3K4me-binding site of the PHD fingers appears to have no effect. Our approach provides a novel tool for studying the biological roles of methyllysine readers in epigenetic signaling.

Introduction

The plant homeodomain (PHD)4 finger is found in a wide range of proteins that mediate epigenetic signaling (reviewed in Ref. 1). This evolutionarily conserved cysteine-rich module is present in a single copy or multiple copies in 291 Homo sapiens, 17 Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 58 Drosophila melanogaster, and 45 Caenorhabditis elegans proteins (SMART). The PHD fingers comprise one of the largest families of epigenetic effectors and, ultimately, histone readers. They bind to posttranslationally modified and unmodified histone H3 tails, recruiting and stabilizing their host proteins at chromatin. The most common function of this domain, exemplified by the PHD fingers of BPTF and ING2, is recognition of trimethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 (H3K4me3) (2–5). Another subset of the PHD fingers has been shown to bind to the unmodified histone H3 tail (6, 7), and a smaller number of PHD fingers are capable of associating with other posttranslational modifications (PTMs) (8).

PHD fingers that recognize histone H3K4me3 do so with high specificity and affinity. This interaction tethers various transcription factors and chromatin-modifying complexes to H3K4me3-enriched genomic regions and is required for fundamental biological processes, including transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling, nucleosome dynamics, cell cycle control, and DNA damage responses. Moreover, colocalization and stabilization of nuclear enzymes and subunits of enzymatic complexes at chromatin often depend on PHD finger activity. These enzymes, also known as writers and erasers, maintain the physiological PTM balance in a spatiotemporal manner that is crucial for cell homeostasis. Loss of such balance results in abnormal gene expression, which can lead to the inactivation of genes required during normal processes, for example tumor suppressor genes, and overexpression of naturally silenced genes, including oncogenes, therefore driving or contributing to the development of disease.

Aberrant chromatin-binding activities of PHD finger-containing proteins due to mutations, deletions, and translocations have been linked directly to cancer, immunodeficiency, and neurological disorders (reviewed in Refs. 9, 10). Deregulation of PHD-dependent H3K4me3 binding of the demethylase JARID1A, as a consequence of a gene fusion to the common translocation partner NUP98, triggers hematopoietic malignancies (11). Binding of the PHD fingers to H3K4me3 is essential for tumor-suppressive, or, in some instances, oncogenic mechanisms of the inhibitor of growth 1–5 (ING1–5) proteins (reviewed in Ref. 12). Loss of the third PHD (PHD3) finger of the methyltransferase MLL1 in the MLL-ENL translocation causes constitutive transactivation of the fused protein, which promotes leukemogenesis (13). Mutations in the PHD finger of RAG2 have been found in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome and in Omenn syndrome, in which V(D)J recombination and the formation of T and B cell receptors are impaired (14). Owing to their prominent role in epigenetic regulation, the PHD finger-containing proteins could be valuable diagnostic markers or pharmacological targets in preventing or treating these diseases.

Recent breakthroughs in biological and medical applications of small molecule antagonists for acetyllysine-binding bromodomain, methyllysine-binding MBT and chromodomain, and arginine-recognizing WD40 demonstrate the vast potential of targeting the histone readers (15–20). A number of epigenetic inhibitors are in clinical trials as anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents (15, 21, 22). Many more show beneficial effects in animal and cellular models and are used successfully in testing the biological activities of reader-, writer- and eraser-containing proteins. To date, various small molecule inhibitors and peptidomimetics have been designed to block the interaction of a histone reader by competing with a histone substrate for the same narrow, deep, and therefore druggable binding site. However, the histone H3K4me3 tail is bound in a wide and shallow binding site of the PHD finger. This binding site is not easily amenable to the design of conventional small molecule inhibitors, and only a few groups have reported progress in this regard (23, 24).

Alternatively, PTM-reader complexes could be disrupted using chemicals that target PTMs rather than readers. Supramolecular caging compounds, including synthetic receptors, chelating macrocycles, and calixarenes, have been shown to coordinate unmodified and posttranslationally modified amino acids and, therefore, can be applied for studying epigenetic mechanisms (25–31, 45, 46). We have demonstrated previously that calixarenes inhibit binding of the second PHD finger of CHD4 to histone H3 trimethylated at Lys-9, although this binding does not involve the formation of a methyllysine-recognizing aromatic cage (32, 33). Here we characterize the mechanisms by which calixarenes interact with the canonical PHD-H3K4me3 complexes and examine the effect of the aromatic cage architecture on these interactions. Our results reveal that calixarenes display selectivity in disrupting the association of PHD fingers with the methylated histone H3K4 tail. We show that the calixarene activity relies on differences in binding affinities of the PHD fingers for H3K4me and the methylation state of the histone substrate and that the caging compound can be modified further to enhance its inhibitory capability toward individual PHD fingers. This approach provides new tools for probing biological functions of the methyllysine readers.

Experimental Procedures

Synthesis of Calix[4]arene Derivatives

Calixarene (1) was purchased from TCI America. Calixarenes (2–8) were synthesized as described in Refs. 26, 32 and the supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Fluorescence Displacement Assay

The FDA was performed as described in the supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Protein Purification

The constructs containing the ING2 PHD (212–264), MLL5 PHD (117–181), MLL1 PHD3 (1565–1627), and JARID1A PHD3 (1608–1659) were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta2 BL21(DE3) pLysS cells in Luria broth or [15N]H4Cl-supplemented minimal media. Protein production was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 18 °C overnight. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. The 15N-labeled GST fusion proteins were purified by GST affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). The GST tag was cleaved with Prescission or Thrombin (GE Healthcare) proteases. The cleaved proteins were eluted and concentrated in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.9), 150 mm NaCl, and 5 mm dithiothreitol.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR experiments were performed on 500- and 600-MHz Varian INOVA spectrometers at 298 K. 1H,15N heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra were recorded for each 15N-labeled PHD finger (0.1 mm) in the absence and presence of saturating concentrations of H3K4me2 (1–12) or H3K4me3 (1–12) peptides (synthesized by the UCD Biophysics Core Facility). Subsequently, increasing amounts of calixarenes were added in a stepwise manner. Kd values were calculated by a nonlinear least squares analysis in Kaleidagraph using the following equation: Δδ = Δδmax((([L] + [P] + Kd) − sqrt(sqr([L] + [P] + Kd) − (4 × [P] × [L]))) / (2 × [P])), where [L] is the concentration of the peptide, [P] is concentration of the protein, Δδ is the observed chemical shift change, and Δδmax is the normalized chemical shift change at saturation. The normalized chemical shift change was calculated using the equation [(ΔδH)2 + (ΔδN / 5)2]0.5, where δ is chemical shift in parts per million (ppm).

Pulldown Assays

GST fusion MLL5 PHD and ING2 PHD proteins (50 μm) were incubated with 5 μm C-terminal biotinylated peptides (AnaSpec) corresponding to the H3K4me3 (residues 1–21) and H3K4me2 (residues 1–21) histone tails in the presence or absence of 100 μm of calixarenes in 50 μl of binding buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 0.2% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 2 h. Streptavidin-agarose resin (Thermo Scientific) was added to the reaction mixture and incubated for an additional 2 h. The beads were collected via centrifugation and washed with binding buffer. The bound protein was detected by Coomassie staining of an SDS-PAGE gel.

Fluorescence Polarization Assays

Peptides for fluorescence polarization (histone H3, residues 1–20) were synthesized as described previously (34) with the addition of 5-carboxyfluorescein at the C terminus. Binding assays were performed as described previously (35) with the following modifications. Reactions were performed in 25 μl in black flat bottom 384-well plates (Costar). Protein was titrated with 20 nm peptide in buffer containing 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, and 0.05% Nonidet P-40. Following a 10-min equilibration period at 25 °C, the plates were read on a PHERAstar microplate reader (BMG Labtech) using a 480-nm excitation filter and 520/530-nm emission filters. For displacement assays, the indicated concentrations of (1) were incubated with MLL5 PHD (10 μm) or ING2 PHD (5 μm) and 20 nm tracer peptide in the buffer described above. Anisotropy units were normalized to the signal in the absence of (1) (100% bound). IC50 values were determined by variable slope non-linear regression analysis and a least squares fit using GraphPad Prism v5.

Cell Line and Culture

C2C12 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml). To create the MLL5-expressing cell line, C2C12 cells were transfected with a Tol2 transposon containing full-length murine MLL5 with an N-terminal FLAG tag under the control of a Tet-responsive element and a puromycin resistance marker and the rtTA2S-M2 Tet activator under the control of a PGK promoter (the sequence file can be found in the in supplemental ExperimentalProcedures) along with the Tol2 transposase. Integrants were selected and maintained on 2 μg/ml puromycin.

Proximity Ligation Assay

10,000 C2C12:FLAG-MLL5 cells were seeded into each well of an 8-well Lab-Tek chamber slide with or without 1 μg/ml doxycycline and grown at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 16 h, (1) or vehicle control was added to the appropriate wells, and cells were incubated for a further 8 h. The final concentration of (1) was 100 μm diluted from a 25 mm stock in 50% DMSO. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin and 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and processed with the DuoLink proximity ligation assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. DUO92101) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. FLAG-MLL5 was labeled with a mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. F1804), and histone H3K4me3 was labeled with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Active Motif, catalog no. 39159) diluted 1:2000 and 1:500, respectively, in the diluent provided with the kit. Cells were imaged using a Delta Vision Elite fluorescence microscope with a ×60 objective, and images were analyzed by manually counting fluorescent spots in three dimensions using the Imaris software suite. 88–104 cells were quantitated for each condition.

Protein Extracts and Western Blot Analysis

Transfected cells were washed with PBS once, resuspended in Nonidet P-40/sucrose buffer (0.32 m sucrose, 3 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) and incubated on ice for 5 min. Nuclei were pelleted at 1500 × g and washed once with sucrose buffer without Nonidet P-40. For Western blots, the nuclei were resuspended in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, sonicated (avoiding overheating), and incubated on ice for 10 min. The samples were spun at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were recovered. 50 μg of extract was resolved in 4–20% acrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF by standard methods. Membranes were blotted with mouse anti-FLAG (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. F1804) and rabbit anti-PARP-1 (1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-1750).

Immunofluorescence

10,000 C2C12:FLAG-MLL5 cells were seeded into each well of an 8-well Lab-Tek chamber slide with or without 1 μg/ml doxycycline and grown at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. For calixarene-treated cells, vehicle or 100 μm (1) diluted from a 25 mm stock in 50% DMSO was added for the final 8 h. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% saponin, 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. FLAG-MLL5 was labeled with a mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. F1804) diluted 1:2000 and with an anti-mouse Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, catalog no. 715-165-150) diluted 1:250. H3K4me3 was labeled with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Active Motif, catalog no. 39159) diluted 1:500 and with an anti-rabbit Cy3 secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, catalog no. 711-165-152) diluted 1:250. Slides were mounted with the media included with the Duolink PLA kit and imaged using a Delta Vision Elite fluorescence microscope with identical exposure settings for each condition.

Results and Discussion

Design of Calixarene Derivatives

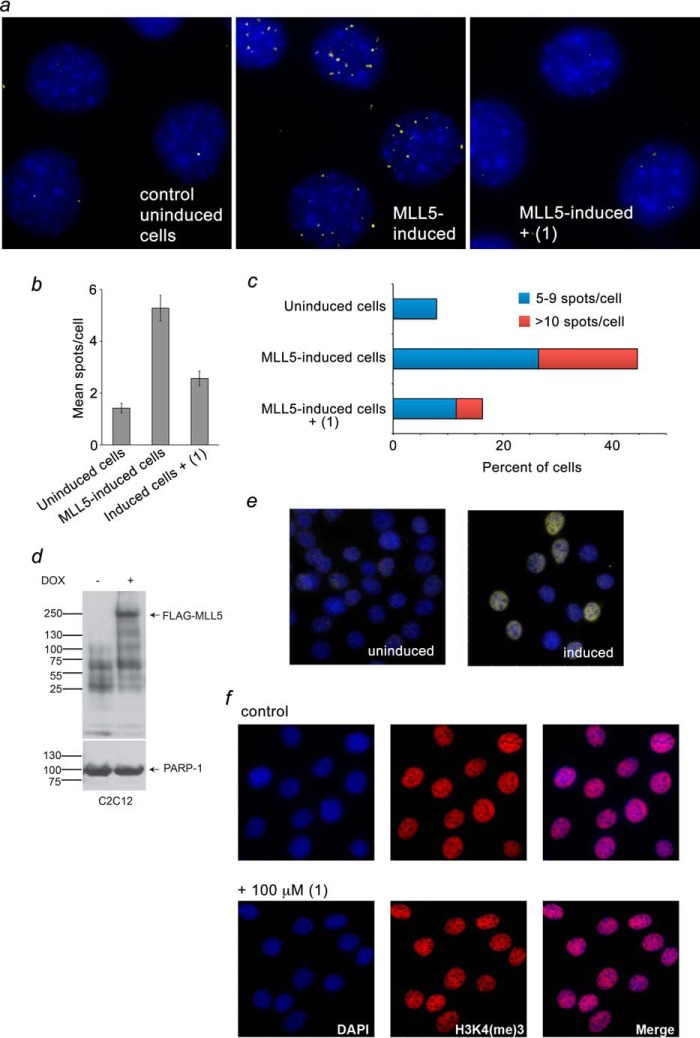

PHD fingers recognize histone H3K4me3 by enclosing trimethyllysine in a cage-like binding pocket that consists of at least one and up to four aromatic residues. Generally, the side chains of these aromatic residues protrude almost perpendicularly to the protein surface and to each other and are involved in cation-π interactions with the trimethylammonium group of Lys-4 (Fig. 1, a and b). In search for approaches to inhibit binding of the PHD fingers to H3K4me3, we designed a set of water-soluble calix[4]arenes (Fig. 1c). The four linked phenol repeats of calix[4]arenes form a rigid bucket-shape scaffold, enabling these compounds to trap methylated lysine in the internal cavity. Because the internal volume and the diameter of the upper rim of calix[4]arenes match the internal volume and distances between the aromatic groups in the aromatic cage of the PHD finger, we rationalized that these calixarenes can mimic the natural K4me3-binding site of the protein (Fig. 1b). The set of calixarenes included analogs of p-sulfonatocalixarene (1) carrying amide- or sulfonamide-linked substituents at one or two positions of its upper rim (2–8) (Fig. 1c) (26, 32). The bulkiness and electrostatic properties of the substituents varied to determine how change in polarity, size, and charge affects the ability of calixarenes to disrupt the PHD-H3K4me3 complexes.

FIGURE 1.

Calix[4]arenes mimic the aromatic cage of PHD fingers. a, schematic showing the disruption of the association of a PHD finger (orange) with the histone H3K4me3 tail by calixarene (yellow). b, distances between the aromatic groups in the methyllysine-binding cage of the BPTF PHD finger (left panel) and distances between sulfur and carbon atoms in calixarene (right panel) are indicated by dashed lines. c, the calixarene hosts used in this study.

Selectivities of Calixarenes for Methylated Histone H3

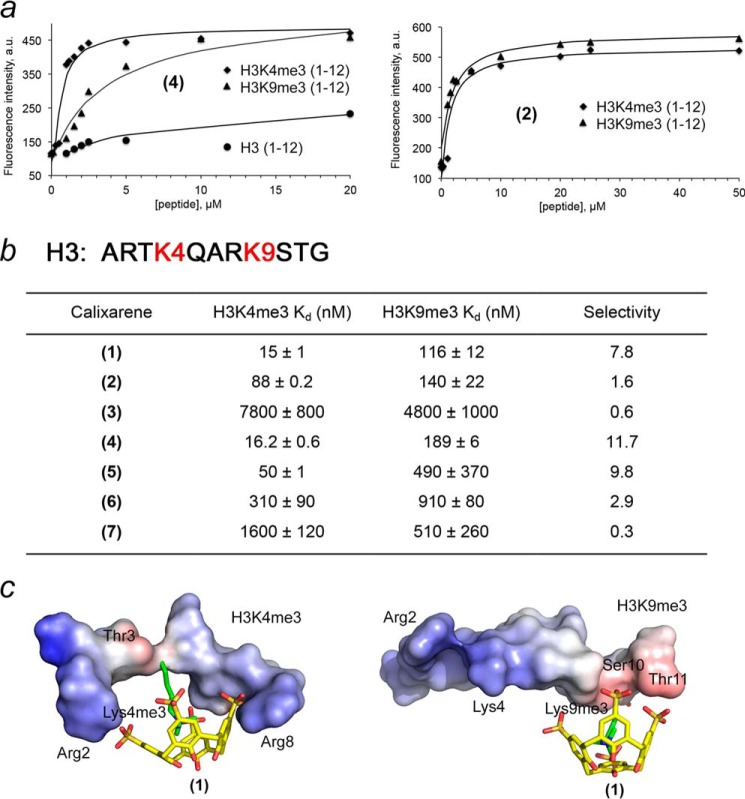

To examine the effect of substituents on the methyllysine-binding activity of (1), we characterized the association of calixarenes (1–7) with histone H3K4me3 peptide (residues 1–12 of H3) using an FDA (Fig. 2a). In this assay, the histone peptide was titrated into a calixarene sample containing a Lucigenin dye. Displacement of the dye by H3K4me3 was monitored through the change in fluorescence intensity at 485 nm. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) for the complex of calixarene (1) with H3K4me3 peptide was found to be 15 nm (Fig. 2b). Substitution of one of the sulfonate groups in (1) with a bulkier, negatively charged or neutral moiety had no effect on this interaction. However, p-bromo-phenyl substituents in (3) and (6) significantly reduced histone binding, which was further weakened in the case of (7), a calixarene carrying two p-carboxy-phenylsulfonamide groups.

FIGURE 2.

Calixarenes display a selectivity for methylated histone peptides. a, representative FDA binding curves for the indicated peptides and calixarenes. b, dissociation constants measured by FDA. Selectivity for H3K4me3 determined by the ratio of H3K4me3 versus H3K9me3. Data are mean ± S.D. c, modeling of the complexes of (1) with H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 peptides. The electrostatic surface potential of the peptides was generated in PyMOL.

The amino terminus of native histone H3 can also be trimethylated at Lys-9. Interestingly, the H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 PTMs are associated with opposite biological outcomes. Whereas the former is found at promoters of actively transcribed genes, the latter is a mark of transcriptionally inactive pericentric heterochromatin. To determine whether calixarenes select for specific sequences adjacent to trimethyllysine, we tested the binding of (1–7) to histone H3K9me3 peptide (residues 1–12 of H3) by FDA (Fig. 2). We found that the added substituents in general decrease binding of (1) to H3K9me3, and bromophenyl-substituted calixarenes (3) and (6) associate even weaker. A comparison of the binding affinities of calixarenes toward H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 reveals that some calixarenes display a preference for H3K4me3, whereas others select for H3K9me3. Particularly (1), (4), and (5) showed ∼8-, ∼12-, and ∼10-fold selectivity toward H3K4me3 over H3K9me3, respectively, whereas (3) and (7) slightly preferred H3K9me3. These data suggest energetically favorable contacts of (1), (4), and (5) with the peptide residues surrounding K4me3. Modeling of the H3K4me3-(1) complex positioned the negatively charged sulfonate groups of (1) in close proximity to the positively charged side chains of the Arg-2 and Arg-8 of the peptide. Such additional electrostatic interactions are not possible in the H3K9me3-(1) complex, where the negatively charged upper rim of (1) packs against the polar and hydrophobic Ser-10, Thr-11, and Ala-7 residues of the peptide. Together, FDA experiments demonstrate that (1), (4), and (5) preferentially bind H3K4me3 and can be used to modulate the histone-binding activities of H3K4me3-specific readers, including PHD fingers.

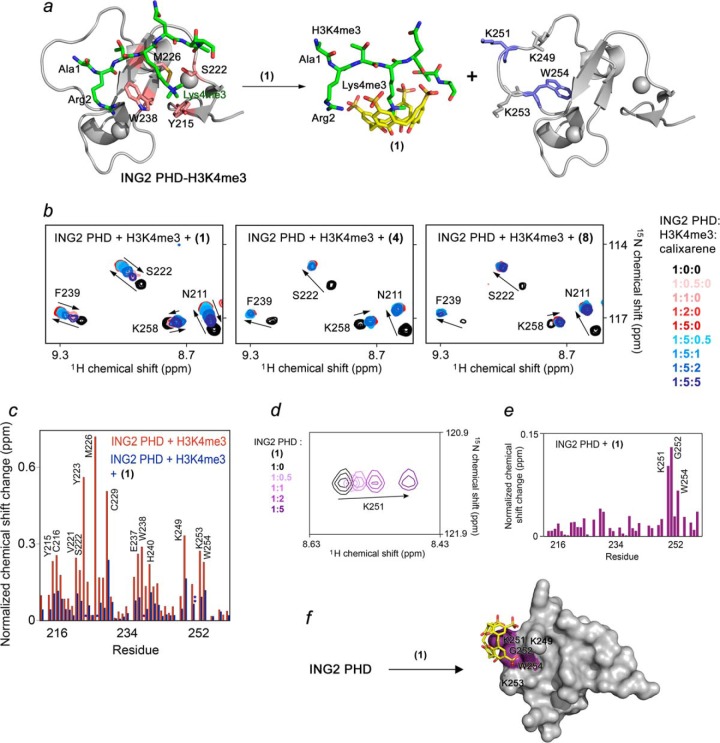

Inhibition of the ING2 PHD-H3K4me3 interaction

The ability of calixarenes to disrupt PHD finger binding to histone H3K4me3 was examined by NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 3). We collected 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the uniformly 15N-labeled PHD finger of ING2 while H3K4me3 peptide was added gradually to the NMR sample. As anticipated, the histone peptide induced large chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) in the protein, confirming direct interaction with H3K4me3 (Fig. 3b, first panel, red gradient colors). Progressive shifting and broadening of cross-peaks revealed an intermediate exchange regime on the NMR time scale, which was consistent with the binding affinity of the ING2 PHD finger measured for H3K4me3 (Kd, 1.5 μm) (3). Subsequent titration of (1) caused the amide resonances of the ING2 PHD finger to shift back to their positions in the ligand-free form of the protein (blue gradient colors, Fig. 3b), indicating dissociation of the PHD-H3K4me3 complex and formation of a supramolecular H3K4me3-(1) complex. Contrary to (1), we found that the carboxyphenylsulfonamide analog (4) does not disrupt the PHD-H3K4me3 complex despite the fact that both calixarenes interact with the H3K4me3 peptide almost equally well (Fig. 3b, second panel). The less bulkier phenyl analog (8) showed a weak inhibition at a PHD:H3K4me3:(8) ratio of 1:5:5 (Fig. 3b, third panel). These results suggest that steric hindrance reduces the inhibitory activity of calixarenes carrying large substituents toward the ING2 PHD finger complex.

FIGURE 3.

Calixarene (1) inhibits binding of the ING2 PHD finger to H3K4me3. a, molecular model depicting disassociation of the ING2 PHD-H3K4me3 complex because of (1). The crystal structure of the H3K4me3-bound ING2 PHD finger (PDB code 2G6Q) is shown as a ribbon diagram with the H3K4me3 peptide colored green. The ING2 residues comprising the methyllysine-binding aromatic cage are colored pink, whereas residues involved in a nonspecific interaction with (1) are shown in blue. b, superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of ING2 PHD, collected as first H3K4me3 peptide and then (1), (4), or (8) were titrated in. The spectra are color-coded according to the protein:peptide:calixarene molar ratio as shown in the right panel. c, the normalized chemical shift changes observed in the ING2 PHD finger upon binding to H3K4me3 (red) and inhibition by (1) (blue) as a function of residue. *, peaks disappear; **, peaks move in a different direction. d, superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of ING2 PHD collected as (1) was titrated in. e, the normalized chemical shift changes observed in the ING2 PHD finger upon interaction with (1) as a function of residue. f, the residues of the ING2 PHD finger, most perturbed because of the interaction with (1), are mapped onto the structure of the protein.

The majority of CSPs in the ING2 PHD finger triggered by H3K4me3 were reversed complementarily by (1), however, cross-peaks of Lys-251 and Trp-254 of the protein shifted to a different position (Fig. 3c and supplemental Fig. S1). To test whether these residues are involved in a nonspecific interaction with (1), we titrated (1) into the ING2 PHD finger in the absence of H3K4me3 (Fig. 3, d–f). Substantial CSPs observed for Lys-251 and Trp-254 confirmed that these residues are likely involved in an off-target interaction with (1). The calculated Kd value of ∼730 μm for this nonspecific interaction was ∼104-fold higher than the Kd value for the specific coordination of H3K4me3 and was in line with affinities measured previously for weak nonspecific associations between calixarenes and proteins (25).

Inhibition of the ING2 PHD-H3K4me3 interaction by (1) was corroborated by pulldown assays. We incubated GST-ING2 PHD with biotinylated histone H3K4me3 peptide (residues 1–20) and with streptavidin-Sepharose beads in the absence and presence of calixarenes. After collecting the bead fraction through centrifugation, the histone-bound PHD finger was detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4a). In the absence of (1), the ING2 PHD finger bound to H3K4me3, however, treatment with (1) abrogated this interaction. In support of the NMR titration experiments, (8) only slightly diminished the association of the PHD finger with H3K4me3. Therefore, among all calixarenes tested, (1) appears to be the most effective inhibitor of the ING2 PHD-H3K4me3 interaction. Fluorescence polarization displacement assays revealed a dose-dependent inhibition of the ING2 PHD-H3K4me3 complex by (1), with an IC50 of 108 μm (Fig. 4b).

FIGURE 4.

Calixarene (1) impairs the interaction of the ING2 PHD finger with H3K4me3 but does not disturb the interaction with H3K4me2. a, binding of the GST-fusion ING2 PHD finger to the indicated biotinylated histone peptides in the absence or presence of the indicated calixarenes was examined by pulldown assay. b, quantitation of the interaction of ING2 PHD with H3 (black) or H3K4me3 (blue) peptides by fluorescence polarization (top panel) or fluorescence polarization displacement (center panel) by (1). Bottom panel, quantitation of the interaction of (1) with H3 (black) or H3K4me3 (blue) peptides by fluorescence polarization (bottom). c, overlays of 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the H3K4me2-bound ING2 PHD finger recorded during gradual addition of (1) or (4).

Calixarenes Do Not Affect the ING2 PHD-H3K4me2 Complex

Both trimethylated species and dimethylated species, H3K4me3 and H3K4me2, have been found in overlapping genomic regions near the gene transcription start sites, however, these PTMs regulate chromatin in a different way. The ING2 PHD finger binds to H3K4me2 with an appreciable for an epigenetic reader affinity (Kd, 15 μm) even though it is ∼10-fold weaker as compared to the affinity of this protein for H3K4me3 (Kd, 1.5 μm) (3). We analyzed the ability of calixarenes to block binding of the ING2 PHD finger to H3K4me2 using 1H,15N HSQC titration experiments (Fig. 4c). In contrast to robust inhibition of the stronger interaction of the ING2 PHD finger with H3K4me3, we found that (1) does not inhibit the weaker interaction of the ING2 PHD finger with H3K4me2 at the same protein:peptide:calixarene ratio of 1:5:5. Calixarene (4) was also unable to disrupt the PHD-H3K4me2 complex. In agreement, the GST-ING2 PHD finger recognized immobilized biotinylated H3K4me2 peptide either in the presence or absence of (1), confirming that (1) does not eliminate binding of the PHD finger to H3K4me2 (Fig. 4a). This, at first glance counterintuitive, finding can be explained in terms of the host-guest capabilities of calixarenes. Calixarene (1) has been shown to select for a trimethylated lysine residue over an unmodified lysine residue by ∼70-fold (26), therefore, this high selectivity most likely accounts for its inability to disrupt the ING2 PHD-H3K4me2 complex.

Together, the NMR and pulldown data reveal that (1) inhibits binding of the ING2 PHD finger to H3K4me3 without affecting its binding to another physiologically relevant ligand, H3K4me2. The strong selectivity of (1) offers a unique approach to separate the two functions of the PHD finger, which would be impossible to achieve using a conventional small molecule inhibitor of the protein.

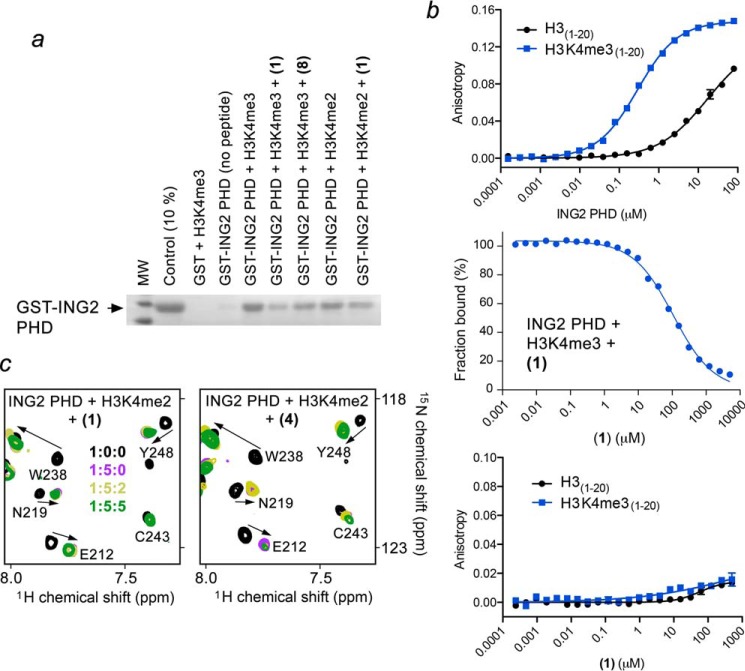

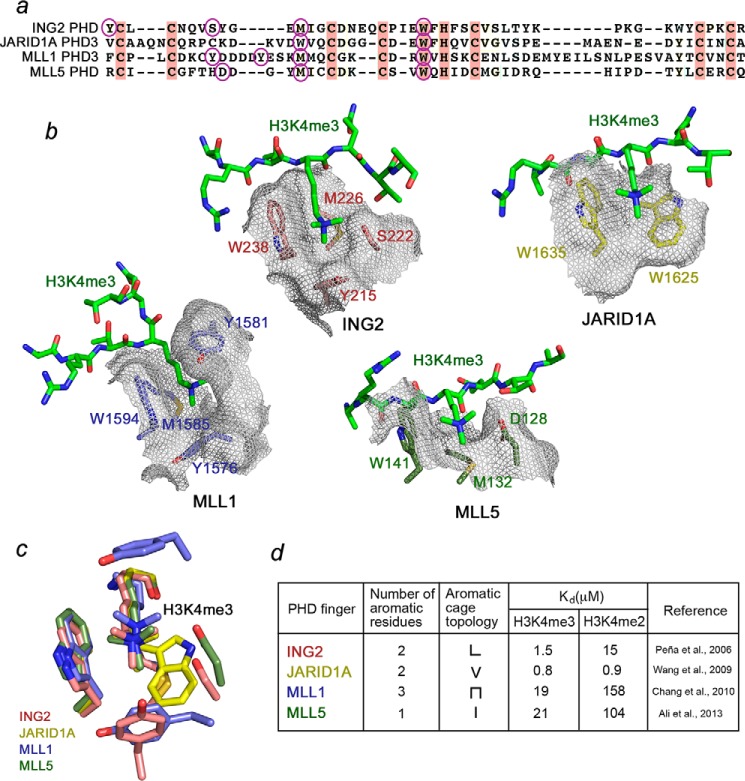

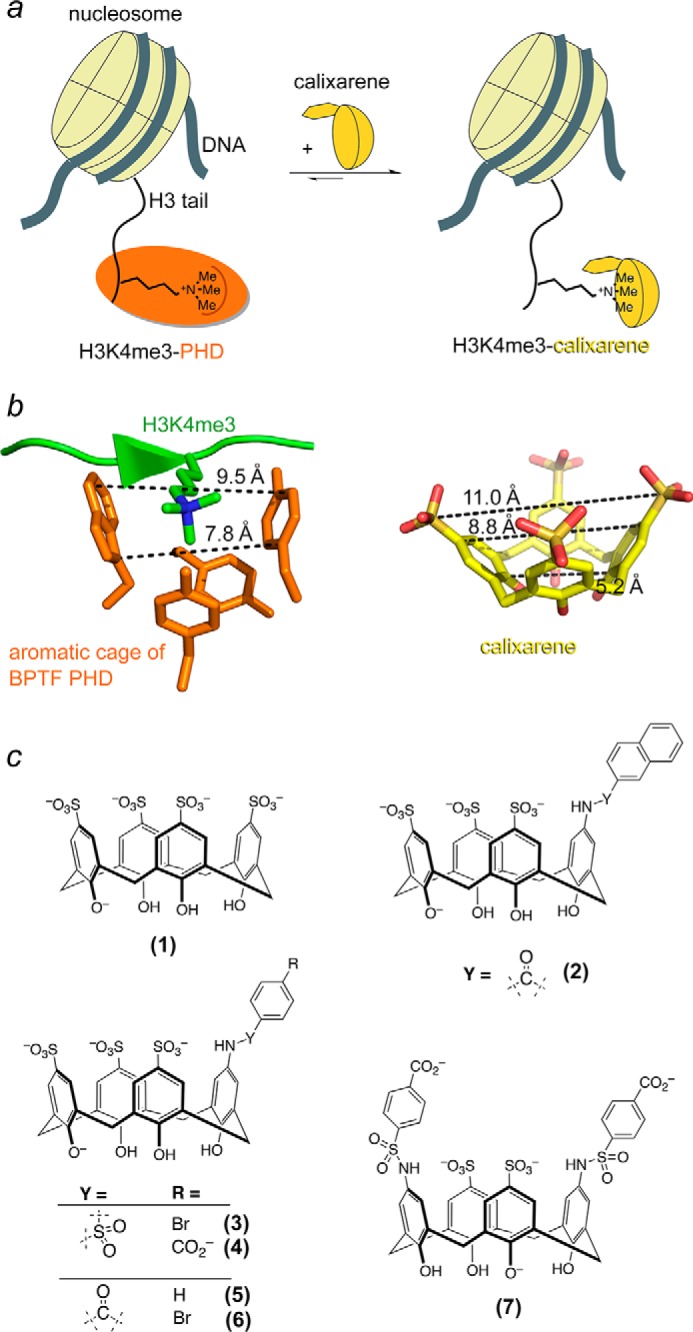

Effects of Affinity and the Aromatic Cage Topology

The topology of the aromatic cage and histone binding affinities vary significantly among PHD fingers. In attempt to develop calixarene-based derivatives selective for a particular group of readers, we compared the PHD fingers of JARID1A, ING2, MLL1, and MLL5. The aromatic cages of MLL5, JARID1A, ING2, and MLL1 contain one, two, two, and three aromatic residues, respectively (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the four PHD fingers have dissimilar methyllysine pocket geometries. The trimethylated lysine in the MLL5-H3K4me3 complex occupies a channel whose walls are made of Trp-141 and Asp-128, whereas Met-132 resides at the bottom (Fig. 5b) (36). JARID1A is characterized by a shallow V-shaped groove consisting of two tryptophan residues, Trp-1625 and Trp-1635 (11). By contrast, the two aromatic residues of ING2, Tyr-215 and Trp-238, are positioned upright and together with the side chain of Ser-222 form three walls of the cage, with Met-226 lining the bottom (3). The aromatic cage of MLL1 is unique because it undergoes a large conformational change upon binding of H3K4me3. A loop containing Tyr-1581 swings toward the aromatic cage composed of Tyr-1576, Trp-1594, and Met-1585. The aromatic ring of Tyr-1581 then acts as a lid, closing the cage and burying the trimethyllysine ligand (37).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of binding affinity and the aromatic cage topology. a, alignment of PHD finger sequences. Conserved residues are colored pink. The aromatic cage residues of each PHD finger are indicated by purple ovals. b, a close view of the aromatic cages of the PHD fingers of ING2 (PDB code 2G6Q), JARID1A (PDB code 3GL6), MLL1 (PDB code 3LQJ), and MLL5 (PDB code 2LV9) (3, 11, 36, 37). The aromatic cage residues of ING2, JARID1A, MLL1, and MLL5 are labeled and colored pink, yellow, blue, and green, respectively. c, an overlay of the K4me3-binding pockets of ING2, JARID1A, MLL1, and MLL5. d, summary of the Kd values and aromatic cage topologies of the PHD fingers.

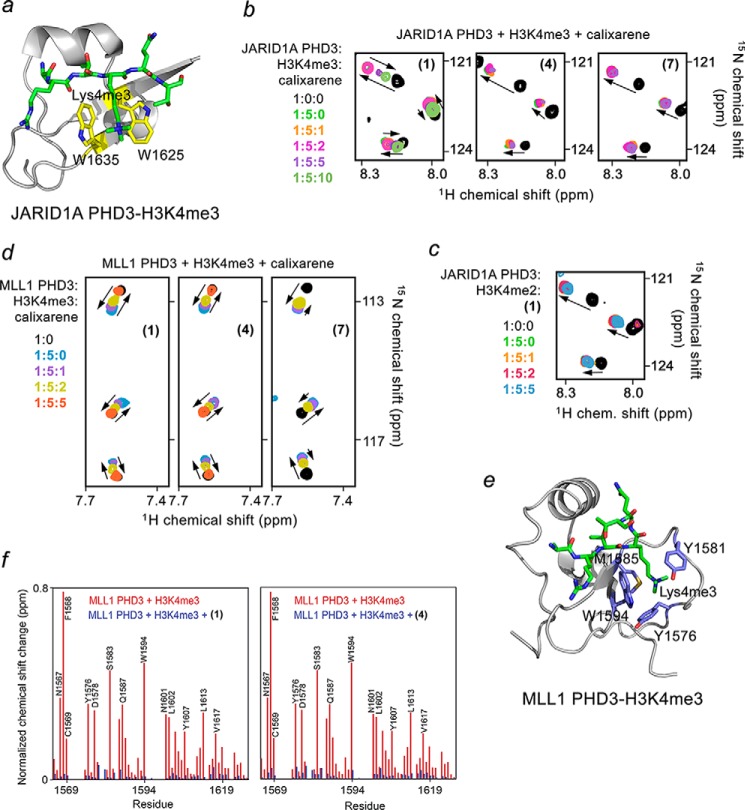

To determine whether (1) can impede the functions of other PHDs, we characterized the histone-binding activity of the JARID1A PHD3 finger. Addition of (1) to the 15N-labeled JARID1A PHD3 finger, prebound to the unlabeled H3K4me3 peptide, led to substantial CSPs and nearly restored the spectrum of the ligand-free PHD finger at a protein:H3K4me3:(1) ratio of 1:5:10 (Fig. 6). Much like the reverse pattern of CSPs observed earlier for ING2, the reverse pattern of CSPs for JARID1A indicated dissociation of the JARID1A PHD3-H3K4me3 complex. Although the JARID1A PHD3 finger has a more shallow aromatic cage, it binds to H3K4me3 twice as strong as ING2 PHD binds to H3K4me3 (3, 11). Accordingly, at least twice more of (1) was required to inhibit the association of the JARID1A PHD3 finger with H3K4me3. As expected, neither (4) nor (7) were able to perturb the JARID1A PHD3-H3K4me3 complex. Together, the NMR titration experiments suggest that the PHD-H3K4me3 complex dissociation constants, rather than the aromatic cage geometry, drive inhibition by calixarenes.

FIGURE 6.

Calixarenes exhibit selectivity for the PHD fingers of JARID1A and MLL1. a, the crystal structure of the JARID1A PHD3 finger in complex with H3K4me3 peptide (PDB code 3GL6). The aromatic cage residues are colored yellow. b, superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of JARID1A PHD3, collected as first H3K4me3 peptide and then (1), (4), or (7) were titrated in. The spectra are color-coded according to the protein:peptide:calixarene molar ratio. c, overlays of 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the H3K4me2-bound JARID1A PHD3 recorded during titration with (1). d, superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of MLL1 PHD3 collected as first H3K4me3 peptide and then (1), (4), and (7) were added gradually. e, the crystal structure of the MLL1 PHD3 finger in complex with H3K4me3 peptide (PDB code 3GL6). The aromatic cage residues are colored blue. f, the normalized chemical shift changes observed in the MLL1 PHD finger upon binding to H3K3me3 (red) and inhibition by (1) or (4) (blue) as a function of residue.

Unlike the ING2 PHD finger that binds to H3K4me2 ∼10-fold more weakly than it binds to H3K4me3, the JARID1A PHD3 finger recognizes both methylated states equally well (Kd values of 0.8 and 0.9 μm for H3K4me2 and H3K4me3, respectively) (3, 11). Titration of (1) into the JARID1A PHD3-H3K4me2 complex resulted in no CSPs, indicating that (1) is incapable of eliminating binding of the JARID1A PHD3 finger to H3K4me2 (Fig. 6c).

Calixarenes Disrupt Weak Complexes of MLL1 and MLL5

Whereas ING2 and JARID1A PHDs represent typical PHD modules, with binding affinities toward H3K4me3 being in the range of 1–10 μm, the PHD fingers of MLL1 and MLL5 bind H3K4me3 much weaker (Kd values of ∼ 20 μm) and associate with H3K4me2 in the 100–200 μm range (3, 11, 36–38). Despite the fact that trimethylated lysine in the MLL1 PHD3-H3K4me3 complex is completely buried in the aromatic cage, all tested calixarenes, including (1), (4), and (7), were able to inhibit this interaction on the basis of reverse CSPs observed in the HSQC titration experiments (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, (1) and (4) abolished the interaction equally well (Fig. 6f), implying that a particular calixarene host could be chosen to eliminate the histone binding activity of a particular PHD finger. For instance, (4) disrupts the complex of the MLL1 PHD finger, whereas it does not disrupt the complexes of ING2 or JARID1A PHD fingers at the same calixarene concentration.

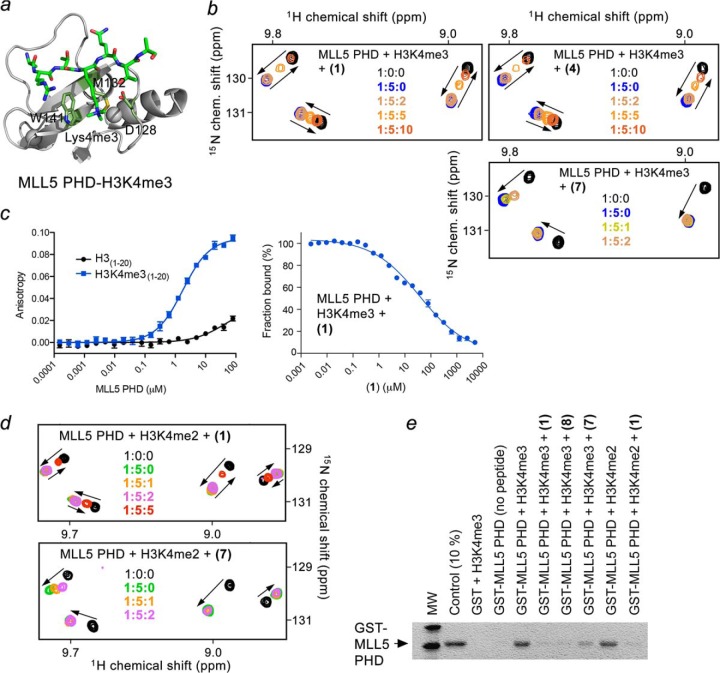

We next examined whether calixarenes can impede binding of the MLL5 PHD finger that contains a single aromatic residue in the binding cage using NMR and pulldown assays (Fig. 7). We found that (1), (4), (7), and (8) impair binding of the MLL5 PHD finger to H3K4me3, although (7) does so weakly (Fig. 7b). Inhibition by (1) was dose-dependent and had an IC50 of 37 μm as measured by fluorescence polarization (Fig. 7c). Moreover, (1) and (7) were capable of disrupting a weak (Kd, 104 μm) complex of the MLL5 PHD finger with H3K4me2 (Fig. 7, d and e). These findings reinforce our conclusion that the topology of the aromatic cage appears to have no effect on the inhibition but binding affinity does play a significant role. These results also suggest that calixarenes (4), (7), and (8) can be used to block the H3K4me-binding activity of the PHD fingers that weakly interact with this PTM (Kd, >20 μm) while not affecting the strong PHD-H3K4me complexes (Kd, ∼1 μm).

FIGURE 7.

Calixarenes block the histone-binding activity of the MLL5 PHD finger in vitro and in vivo. a, crystal structure of the MLL5 PHD finger in complex with H3K4me3 peptide (PDB code 2LV9). The aromatic cage residues are colored green. b, superimposed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of MLL5 PHD, collected as first H3K4me3 peptide and then (1), (4), or (7) were titrated in. The spectra are color-coded according to the protein:peptide:calixarene molar ratio. c, quantitation of the interaction of MLL5 PHD with H3 (black) or H3K4me3 (blue) peptides by fluorescence polarization (left) or fluorescence polarization displacement (right) by (1). d, overlays of 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the H3K4me2-bound MLL5 PHD recorded during titration with (1) or (7). e, binding of the GST-fusion MLL5 PHD finger to the indicated biotinylated histone peptides in the absence or presence of the indicated calixarenes.

Displacement of MLL5 by (1) in Vivo

Recruitment of MLL5 to chromatin has been shown to rely on binding of its PHD finger to H3K4me3 (36). To determine whether calixarene inhibitors can disrupt the interaction of the PHD finger with H3K4me3 in vivo, we tested the chromatin localization of MLL5 using a Duolink PLA (Fig. 8). We have previously optimized this assay to detect specifically and only directly interacting MLL5-H3K4me3 foci (36). We generated a C2C12 cell line with an inducible full-length murine MLL5 harboring an N-terminal FLAG tag. C2C12:FLAG-MLL5 cells were treated with ±100 μm (1) and subjected to the PLA with primary antibodies against the FLAG tag and H3K4me3. FLAG-MLL5-H3K4me3-interacting foci were detected by microscopy as fluorescent spots. In agreement with a previous report (36), in the absence of inhibitors, a large number of fluorescent spots were observed in each nucleus, indicating that MLL5 localizes at the genomic regions enriched in H3K4me3 (Fig. 8a, center panel). However, treatment of the cells with (1) substantially decreased the number of interacting foci, suggesting that MLL5 is disengaged from chromatin when calixarene is present (Fig. 8a, right panel). Quantitative analysis of the experiments confirmed that treatment with (1) considerably reduced both the mean number of spots per cell and the fraction of cells with multiple spots (Fig. 8, b and c). These results are consistent with in vitro inhibition data and demonstrate that (1) can be used to eliminate the MLL5 PHD-H3K4me3 interaction in intact cells.

FIGURE 8.

Calixarene (1) disrupts binding of MLL5 to H3K4me3 in vivo. a, C2C12 cells expressing FLAG-MLL5 were fixed and stained with anti-FLAG and anti-H3K4me3 antibodies and with secondary antibodies conjugated with Duolink PLA probes and Duolink PLA detection reagents and imaged using a fluorescence microscope. Yellow dots specify interacting foci. Nuclei are labeled blue (DAPI). b, mean ± S.E. of MLL5-H3K4me3-interacting foci per indicated cells. c, percentage of cells with 5–9 (blue) and more than 10 (red) MLL5-H3K4me3-interacting foci. The remaining cells (not shown) contain 0–4 foci. d, levels of FLAG-MLL5 were evaluated by Western blot analysis upon doxycycline (DOX) induction for 24 h. PARP-1 was used as a loading control. e, levels of FLAG-MLL5 were evaluated by immunofluorescence microscopy upon doxycycline induction for 24 h. Identical exposure settings and histogram adjustments were used for each condition (uninduced, left panel, and induced, right panel). f, H3K4me3 levels in C2C12:FLAG-MLL5 cells. Cells were treated with or without 100 μm (1) and processed for immunofluorescence. A z-slice from the nuclear midpoint is shown. Identical exposure settings and histogram adjustments were used for each condition.

Concluding Remarks

Impaired histone-binding function of PHD fingers causes mislocalization and nuclear-to-cytosolic redistribution of the host proteins and chromatin-associating complexes, leading to genomic instability and deregulation of various signaling pathways (39). Developing novel approaches to manipulate the activities of these proteins and complexes can be pivotal for understanding alterations in chromatin structure and gene expression patterns. A well documented link between aberrant activities of PHD finger-containing proteins and various human diseases points to vast therapeutic potential. Therefore, designing inhibitors of the PHD-histone interactions is also essential for advancing cutting edge, epigenetically driven therapeutic strategies (21).

In this study, we show that supramolecular caging compounds impair the association of the PHD fingers with methylated H3K4 tails. The inhibitory activity of calixarenes depends on differences in binding affinities and the methylation state of the histone ligand and can be augmented toward certain PHD finger-histone complexes by further amending the caging compound. We demonstrate that calixarenes can target trimethyllysine and disrupt PHD-H3K4me3 complexes in vitro and in vivo. A unique architecture of the H3K4me3-PHD interface, the geometric complementarity of calix[4]arenes to the trimethyllysine-binding aromatic cage, and their cell permeability substantially widen the experimental applicability of the supramolecular hosts (40). We expect these compounds to be used as novel tools in a wide array of biochemical assays, histone peptide microarrays, and high-throughput screens that aim to identify novel methyllysine readers and characterize histone binding mechanisms of known epigenetic readers. We note that further studies are necessary to examine whether calixarenes can disrupt complexes of other readers of the H3K4me3 PTM, including CHD1 double chromodomains, tandem Tudor domains of JMJD2A and SGF29, and a CW zinc finger of ZCWPW1 (41–44).

Author Contributions

M. A., K. D. D., D. E. S., S. B. R., H. R. A., H. F. A., and J. L. performed experiments and, together with B. D. S., F. H., and T. G. K., analyzed the data. T. G. K. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Supplementary Material

This research was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM101664 and GM100907 (to T. G. K.) and CA181343 (to S. B. R.). This work was also supported by grants from the W. M. Keck Foundation (to B. D. S.) and from Prostate Cancer Canada (to F. H.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1, experimental procedures, and references.

- PHD

- plant homeodomain

- H3K4me3

- trimethylated lysine 4 of histone H3

- PTM

- posttranslational modification

- FDA

- fluorescence displacement assay

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- PLA

- proximity ligation assay

- CSP

- chemical shift perturbation.

References

- 1. Musselman C. A., Kutateladze T. G. (2011) Handpicking epigenetic marks with PHD fingers. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9061–9071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li H., Ilin S., Wang W., Duncan E. M., Wysocka J., Allis C. D., Patel D. J. (2006) Molecular basis for site-specific read-out of histone H3K4me3 by the BPTF PHD finger of NURF. Nature 442, 91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peña P. V., Davrazou F., Shi X., Walter K. L., Verkhusha V. V., Gozani O., Zhao R., Kutateladze T. G. (2006) Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature 442, 100–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi X., Hong T., Walter K. L., Ewalt M., Michishita E., Hung T., Carney D., Peña P., Lan F., Kaadige M. R., Lacoste N., Cayrou C., Davrazou F., Saha A., Cairns B. R., Ayer D. E., Kutateladze T. G., Shi Y., Côté J., Chua K. F., Gozani O. (2006) ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature 442, 96–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wysocka J., Swigut T., Xiao H., Milne T. A., Kwon S. Y., Landry J., Kauer M., Tackett A. J., Chait B. T., Badenhorst P., Wu C., Allis C. D. (2006) A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature 442, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lan F., Collins R. E., De Cegli R., Alpatov R., Horton J. R., Shi X., Gozani O., Cheng X., Shi Y. (2007) Recognition of unmethylated histone H3 lysine 4 links BHC80 to LSD1-mediated gene repression. Nature 448, 718–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ooi S. K., Qiu C., Bernstein E., Li K., Jia D., Yang Z., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Lin S. P., Allis C. D., Cheng X., Bestor T. H. (2007) DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature 448, 714–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Musselman C. A., Lalonde M. E., Côté J., Kutateladze T. G. (2012) Perceiving the epigenetic landscape through histone readers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1218–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baker L. A., Allis C. D., Wang G. G. (2008) PHD fingers in human diseases: disorders arising from misinterpreting epigenetic marks. Mutat. Res. 647, 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chi P., Allis C. D., Wang G. G. (2010) Covalent histone modifications: miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in human cancers. Nat. Rev. 10, 457–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang G. G., Song J., Wang Z., Dormann H. L., Casadio F., Li H., Luo J. L., Patel D. J., Allis C. D. (2009) Haematopoietic malignancies caused by dysregulation of a chromatin-binding PHD finger. Nature 459, 847–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tallen G., Riabowol K. (2014) Keep-ING balance: tumor suppression by epigenetic regulation. FEBS Lett. 588, 2728–2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen J., Santillan D. A., Koonce M., Wei W., Luo R., Thirman M. J., Zeleznik-Le N. J., Diaz M. O. (2008) Loss of MLL PHD finger 3 is necessary for MLL-ENL-induced hematopoietic stem cell immortalization. Cancer Res. 68, 6199–6207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matthews A. G., Kuo A. J., Ramón-Maiques S., Han S., Champagne K. S., Ivanov D., Gallardo M., Carney D., Cheung P., Ciccone D. N., Walter K. L., Utz P. J., Shi Y., Kutateladze T. G., Yang W., Gozani O., Oettinger M. A. (2007) RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination. Nature 450, 1106–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Filippakopoulos P., Knapp S. (2014) Targeting bromodomains: epigenetic readers of lysine acetylation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 337–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao C., Herold J. M., Kireev D., Wigle T., Norris J. L., Frye S. (2011) Biophysical probes reveal a “compromise” nature of the methyl-lysine binding pocket in L3MBTL1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5357–5362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herold J. M., Wigle T. J., Norris J. L., Lam R., Korboukh V. K., Gao C., Ingerman L. A., Kireev D. B., Senisterra G., Vedadi M., Tripathy A., Brown P. J., Arrowsmith C. H., Jin J., Janzen W. P., Frye S. V. (2011) Small-molecule ligands of methyl-lysine binding proteins. J. Med. Chem. 54, 2504–2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. James L. I., Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Zhong N., Krichevsky L., Korboukh V. K., Herold J. M., MacNevin C. J., Norris J. L., Sagum C. A., Tempel W., Marcon E., Guo H., Gao C., Huang X. P., Duan S., Emili A., Greenblatt J. F., Kireev D. B., Jin J., Janzen W. P., Brown P. J., Bedford M. T., Arrowsmith C. H., Frye S. V. (2013) Discovery of a chemical probe for the L3MBTL3 methyllysine reader domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simhadri C., Daze K. D., Douglas S. F., Quon T. T., Dev A., Gignac M. C., Peng F., Heller M., Boulanger M. J., Wulff J. E., Hof F. (2014) Chromodomain antagonists that target the polycomb-group methyllysine reader protein chromobox homolog 7 (CBX7). J. Med. Chem. 57, 2874–2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ren C., Morohashi K., Plotnikov A. N., Jakoncic J., Smith S. G., Li J., Zeng L., Rodriguez Y., Stojanoff V., Walsh M., Zhou M. M. (2015) Small-molecule modulators of methyl-lysine binding for the CBX7 chromodomain. Chem. Biol. 22, 161–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arrowsmith C. H., Bountra C., Fish P. V., Lee K., Schapira M. (2012) Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 384–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Y., Liu K., Qin S., Xu C., Min J. (2014) Epigenetic targets and drug discovery: part 1: histone methylation. Pharmacol. Ther. 143, 275–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller T. C., Rutherford T. J., Birchall K., Chugh J., Fiedler M., Bienz M. (2014) Competitive binding of a benzimidazole to the histone-binding pocket of the Pygo PHD finger. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 2864–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wagner E. K., Nath N., Flemming R., Feltenberger J. B., Denu J. M. (2012) Identification and characterization of small molecule inhibitors of a plant homeodomain finger. Biochemistry 51, 8293–8306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGovern R. E., Fernandes H., Khan A. R., Power N. P., Crowley P. B. (2012) Protein camouflage in cytochrome c-calixarene complexes. Nature chemistry 4, 527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daze K. D., Ma M. C., Pineux F., Hof F. (2012) Synthesis of new trisulfonated calixarenes functionalized at the upper rim, and their complexation with the trimethyllysine epigenetic mark. Org. Lett. 14, 1512–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martos V., Bell S. C., Santos E., Isacoff E. Y., Trauner D., de Mendoza J. (2009) Molecular recognition and self-assembly special feature: Calixarene-based conical-shaped ligands for voltage-dependent potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10482–10486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Florea M., Kudithipudi S., Rei A., González-Álvarez M. J., Jeltsch A., Nau W. M. (2012) A fluorescence-based supramolecular tandem assay for monitoring lysine methyltransferase activity in homogeneous solution. Chemistry 18, 3521–3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. James L. I., Beaver J. E., Rice N. W., Waters M. L. (2013) A synthetic receptor for asymmetric dimethyl arginine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6450–6455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gamal-Eldin M. A., Macartney D. H. (2013) Selective molecular recognition of methylated lysines and arginines by cucurbituril and cucurbituril in aqueous solution. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 488–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinkin N. K., Waters M. L. (2014) Development and mechanistic studies of an optimized receptor for trimethyllysine using iterative redesign by dynamic combinatorial chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 7059–7067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allen H. F., Daze K. D., Shimbo T., Lai A., Musselman C. A., Sims J. K., Wade P. A., Hof F., Kutateladze T. G. (2014) Inhibition of histone binding by supramolecular hosts. Biochem. J. 459, 505–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mansfield R. E., Musselman C. A., Kwan A. H., Oliver S. S., Garske A. L., Davrazou F., Denu J. M., Kutateladze T. G., Mackay J. P. (2011) Plant homeodomain (PHD) fingers of CHD4 are histone H3-binding modules with preference for unmodified H3K4 and methylated H3K9. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11779–11791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rothbart S. B., Dickson B. M., Ong M. S., Krajewski K., Houliston S., Kireev D. B., Arrowsmith C. H., Strahl B. D. (2013) Multivalent histone engagement by the linked tandem Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1 is required for the epigenetic inheritance of DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 27, 1288–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rothbart S. B., Krajewski K., Nady N., Tempel W., Xue S., Badeaux A. I., Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Martinez J. Y., Bedford M. T., Fuchs S. M., Arrowsmith C. H., Strahl B. D. (2012) Association of UHRF1 with methylated H3K9 directs the maintenance of DNA methylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 1155–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ali M., Rincón-Arano H., Zhao W., Rothbart S. B., Tong Q., Parkhurst S. M., Strahl B. D., Deng L. W., Groudine M., Kutateladze T. G. (2013) Molecular basis for chromatin binding and regulation of MLL5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11296–11301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Z., Song J., Milne T. A., Wang G. G., Li H., Allis C. D., Patel D. J. (2010) Pro isomerization in MLL1 PHD3-bromo cassette connects H3K4me readout to CyP33 and HDAC-mediated repression. Cell 141, 1183–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang P. Y., Hom R. A., Musselman C. A., Zhu L., Kuo A., Gozani O., Kutateladze T. G., Cleary M. L. (2010) Binding of the MLL PHD3 finger to histone H3K4me3 is required for MLL-dependent gene transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 400, 137–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Musselman C. A., Kutateladze T. G. (2009) PHD fingers: epigenetic effectors and potential drug targets. Mol. Interv. 9, 314–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ghale G., Lanctôt A. G., Kreissl H. T., Jacob M. H., Weingart H., Winterhalter M., Nau W. M. (2014) Chemosensing ensembles for monitoring biomembrane transport in real time. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 2762–2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Flanagan J. F., Mi L. Z., Chruszcz M., Cymborowski M., Clines K. L., Kim Y., Minor W., Rastinejad F., Khorasanizadeh S. (2005) Double chromodomains cooperate to recognize the methylated histone H3 tail. Nature 438, 1181–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang Y., Fang J., Bedford M. T., Zhang Y., Xu R. M. (2006) Recognition of histone H3 lysine-4 methylation by the double tudor domain of JMJD2A. Science 312, 748–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bian C., Xu C., Ruan J., Lee K. K., Burke T. L., Tempel W., Barsyte D., Li J., Wu M., Zhou B. O., Fleharty B. E., Paulson A., Allali-Hassani A., Zhou J. Q., Mer G., Grant P. A., Workman J. L., Zang J., Min J. (2011) Sgf29 binds histone H3K4me2/3 and is required for SAGA complex recruitment and histone H3 acetylation. EMBO J. 30, 2829–2842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. He F., Umehara T., Saito K., Harada T., Watanabe S., Yabuki T., Kigawa T., Takahashi M., Kuwasako K., Tsuda K., Matsuda T., Aoki M., Seki E., Kobayashi N., Güntert P., Yokoyama S., Muto Y. (2010) Structural insight into the zinc finger CW domain as a histone modification reader. Structure 18, 1127–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McGovern R. E., Snarr B. D., Lyons J. A., McFarlane J., Whiting A. L., Paci I., Hof F., Crowley P. B. (2015) Structural study of a small molecule receptor bound to dimethyllysine in lysozyme. Chem. Sci. 6, 442–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Beaver J. E., Peacor B. C., Bain J. V., James L. I., Waters M. L. (2015) Contributions of pocket depth and electrostatic interactions to affinity and selectivity of receptors for methylated lysine in water. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 3220–3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.