Abstract

The narrow standard age range of menopause, ∼50 yr, belies the complex balance of forces that govern the underlying formation and progressive loss of ovarian follicles (the “ovarian reserve” whose size determines the age of menopause). We show here the first quantitative graph of follicle numbers, distinguished from oocyte counts, across the reproductive lifespan, and review the current state of information about genetic and epidemiological risk factors in relation to possible preservation of reproductive capacity. In addition to structural X-chromosome changes, several genes involved in the process of follicle formation and/or maintenance are implicated in Mendelian inherited primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), with menopause before age 40. Furthermore, variants in a largely distinct cohort of reported genes—notably involved in pathways relevant to atresia, including DNA repair and cell death—have shown smaller but additive effects on the variation in timing of menopause in the normal range, early menopause (age <45), and POI. Epidemiological factors show effect sizes comparable to those of genetic factors, with smoking accounting for about 5% of the risk of early menopause, equivalent to the summed effect of the top 17 genetic variants. The identified genetic and epidemiological factors underline the importance of early detection of reproductive problems to enhance possible interventions.

Keywords: female infertility, gonadal function, menopause, ovary, primary ovarian insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Menopause is the most sharply timed event during female aging, at 50 ± several years in all societies that have been studied [1]. The underlying process is thus rigorously controlled. Nevertheless, the age of menopause can vary because of a variety of factors. With the growing trend of women delaying reproduction, more complete understanding of ovarian reserve would help inform individual women about options.

Importantly, ∼10% of women have their last menses before age 45, and about 1% reach menopause before 40—primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) [2]. POI can result from a wide range of factors, but all converge on a single axis: the dynamics of the ovarian follicle pool. Each nongrowing primordial follicle (NGF) in the reserve comprises an oocyte arrested in the diplotene stage of meiotic prophase I surrounded by a layer of somatic pregranulosa cells. The reserve forms early in life, and NGFs can remain quiescent for decades; but as the pool progressively depletes, the numbers drop below a minimum and menopause ensues. As we review, any factor—genetic or epidemiological—that changes the number of follicles formed (histogenesis), their potency (response to hormones, etc.), or their maintenance/recruitment/turnover can modify the age of menopause. We review the process and sources of variability of follicle pool formation and subsequent decrease of the reserve. The results also provide information for fertility counseling, including risk of POI.

ESTABLISHMENT AND OVERALL DYNAMICS OF THE OVARIAN RESERVE

Formation and Depletion of the Reserve

Ovarian organogenesis can be divided into three phases [3–5]. First, gonadal morphogenesis involves massive invasion of the genital ridge by mesonephric-derived cells that associate with the primordial germ cells. The originally flat genital ridge is transformed into the voluminous primitive gonad [6].

Second, primary sex differentiation then forms a primitive ovary. The solid cell mass of the primitive gonad is cleaved into “ovigerous cords” of germinal and somatic cells, which finally extend from the wolffian duct to the ovarian surface.

In a final phase, definitive ovarian histogenesis takes place. The ovigerous cords compartmentalize into clusters of germinal and somatic cells from which the ovarian follicles develop [7]. The process begins about Week 19–20 postconception and continues through the first postnatal months [8].

The ovigerous cords comprise about 60% of the cortex of the early human fetal ovary [9]; this proportion diminishes to 14% at birth as follicles form while most germ cells are lost [10, 11], and the ovigerous cords are gone by 8 mo [9]. Full depletion of the ovigerous cords or naked oocyte clusters marks the end of definitive ovary formation.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation initiates follicular recruitment, growth, selection, and dominance of one follicle. Development of follicles requires continued gonadotropin stimulation. FSH must exceed a threshold to promote the final phase of follicular growth, influencing development through receptors on cumulus and granulosa cells [12]. Although theca cell steroidogenesis is mainly regulated by luteinizing hormone (LH), production of androgens, mainly androstenedione and testosterone, is under control of steroidogenic active regulatory protein (StAR). Androgens exert a paracrine effect both through androgen receptors and indirectly by aromatization to estrogens [13], promoting growth of granulosa cells, progesterone production, and conversion to 17β-estradiol. The androgens regulate. Estrogen promotes granulosa cell growth and increases the number of FSH and LH receptors. FSH in turn regulates estrogen production by p450 aromatase, and LH synergizes with FSH to promote follicular growth and ovulation to maintain a normal rate of growing follicles [14]. Later stages of follicle development are regulated by activins and estradiol, further increasing the number of FSH receptors. The dominant follicle (with higher aromatase activity) controls the growth of remaining growing follicles by suppressing FSH (see below), and itself escapes FSH control by increasing LH receptor numbers [13].

Transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) family activins and inhibins are additional important autocrine/paracrine regulators of gonadotropin synthesis at later stages of follicle development [15]. An unrelated TGFB member, follistatin, augments activin modulation of follicle growth and function, and counterbalancing inhibins A and B negatively regulate follicle growth by inhibiting FSH synthesis in the pituitary [16]. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), another TGFB superfamily member produced by granulosa cells in growing follicles, inhibits growth of primordial follicles, helping to maintain the follicle reserve. It is an independent biomarker of ovarian reserve [17, 18].

From the start of follicle recruitment, a percentage of follicles commence development. The percentage of growing follicles is not constant; it represents 0.4%–1.2% initially, but increases sharply towards the end of reproductive life [19–23].

But much more massive loss of germ cells occurs by apoptosis during embryonic formation of the reserve [24] and during follicle recruitment before puberty [25]. At puberty, FSH is also a survival signal that protects growing follicles from atresia. The dominant follicle then produces high levels of estrogens and inhibins [26] that inhibit FSH release from the pituitary, leading to atresia of the remaining follicles while the dominant one ovulates [27].

Atresia occurs both at the transition from primordial to primary follicles [28] and at late stages of follicle maturation [29]. In preantral follicles, the oocyte deteriorates after apoptosis in surrounding granulosa cells [30].

Apoptosis has been described as the predominant pathway of germ cell and follicle atresia, but recent studies also implicate autophagy [31, 32].

Given the continual loss of net oocyte and follicle content at every stage during reproductive life, the overwhelming importance of atresia in affecting the reserve is unsurprising. There are at least three effective “checkpoints” determining the survival of follicles. The first is during follicle formation, with the loss of about nine oocytes for every one preserved by incorporation in a follicle. The second is during the transition of follicles from primordial to ovulating state, with determinative steps governing the status of primordial follicles and the fate decision to mature one to a few follicles. The third is during the maintenance of the pool throughout the reproductive lifespan. The general thrust of genetic endowment and developmental processes produces the overall curve of ovarian reserve and the strongly regulated timing of menopause reflected in Figure 1, but various genetic and epidemiological factors can change the timing moderately or in some cases drastically, and in an additive way.

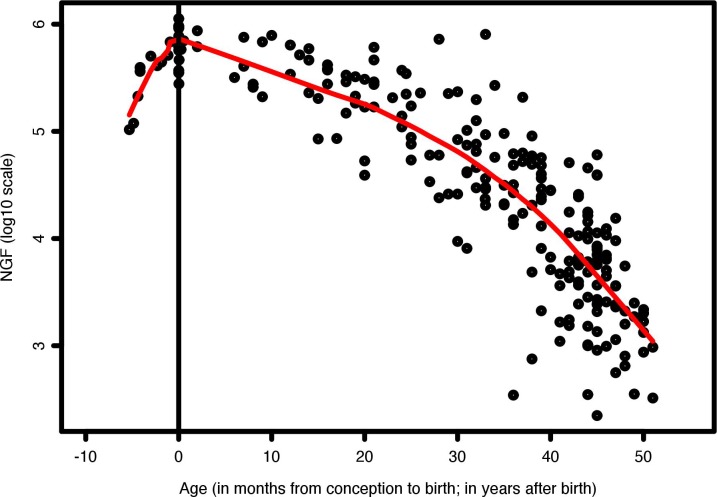

FIG. 1.

Number of NGFs per human ovary during prenatal and postnatal life. Prenatal data points are from Forabosco and Sforza, 2007 [19]; postnatal data points are from literature as compiled by Wallace and Kelsey, 2010 [53].

Normal Rates of Synthesis and Depletion of the Ovarian Reserve

For over 50 yr, notably starting with the work of Zuckerman [33] it has been accepted that in most mammalian species ovaries lose the capacity for germ cell renewal and follicle formation at the end of organogenesis. Thus, a finite pool of NGFs sustains a female's entire reproductive lifespan [3]. This notion, however, has been recently challenged. Johnson et al. [34] proposed that proliferative germ cells exist in adult ovaries, which could sustain postnatal follicle production, and rare germ-line stem-like cells have now been reported in postnatal mouse and human ovaries by several groups [35–37]. Nevertheless, skepticism remains in the scientific community about the capacity of these cells to contribute to follicular renewal in adults [38–41]. In any case, new follicles cannot counterbalance the ovulation and atresia leading to menopause.

Physical and humoral factors have been proposed to assess ovarian reserve, but are not directly related to primordial follicle number. Invasive methods such as biopsy also do not yield reliable estimates of ovarian reserve [42], because follicles are unevenly distributed [43, 44]. The most reliable assessment of ovarian reserve is ovarian removal followed by histomorphometry-based follicle counts in entire ovaries [45]. Two studies have thereby estimated the ovarian reserve formed before birth [19, 46]; four others have focused on ages after birth [20, 47–49].

Including more data than previous models [21, 49–52], Wallace and Kelsey [53] proposed a mathematical model to describe the establishment and decline of human ovarian reserve from conception to menopause. However, for analyses of data before birth, like all previous treatments, the model included free germ cells—far more numerous in early fetal life—along with measures of follicles. Consequently, the curve before birth describes overall dynamics of germ cell content rather than ovarian reserve [53]. By contrast, Figure 1 shows Lowess curves that include only follicle data up to birth and then up to age 52. Thus, the number of follicles before birth never exceeds later numbers.

The ovarian reserve—the NGFs per individual—was ∼100 000 at 15 wk postconception and increased to an average of about 680 000 perinatally. At 66 wk and 2 yr old, the numbers remained comparable (e.g., 625 000 in [49]).

Available data show limited decrement in follicle numbers from 2 yr to puberty. The decrease is the same order as recruitment—reported between 1% [44] and 3% [47]. Postnatal follicle assembly can be efficient at least until 66 wk. Stem cells that generate NGFs are still present in about 0.3% of the ovarian cortex [9]. Recently, new follicle formation at least during the first 1–2 yr of life has been indirectly confirmed by morphology and markers of premeiotic germ cells [39]. Thereafter, however, new follicle formation ceases or at least fails to make up for loss. From available analyses, an average of 463 000 of follicles remain around puberty (age 12–14) [49]. Thereafter, the reserve declines by follicle recruitment and atresia to <1000 NGFs, insufficient to support ovulation [20, 49–50].

The pool of oocytes begins at a far greater level and drops precipitously before birth. Mamsen et al. [54] estimated an average of 4 933 000 per ovary at 19 wk postconception (>2-fold the number assessed by Baker [55] with less precise techniques). Thus, ∼ 85% of oocytes in the ovary are destroyed without contributing to the follicle reserve. It remains unclear whether oocytes survive randomly or pass a selective checkpoint [6] or whether the lost oocytes serve a “nourishing” function, as in Drosophila [56].

GENETIC FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH VARIATION IN FOLLICLE DEPLETION AND AGE OF MENOPAUSE

Factors in POI

Of the extreme cases of follicle depletion (POI), about 40% result from cancer and chemotherapy [57]. Among POI cases associated with genetic mutations, the cause is unknown in up to 90% [58], but increasing progress has been made in identifying genetic factors [59].

X-Chromosome Number/Structure Changes

X-autosomal translocations and chromosomal changes.

Up to 1 in 200 live births have been estimated to carry a balanced translocation [60]. Among them, reciprocal autosomal or Robertsonian translocations can cause Mendelian disorders, but rarely if ever causes POI. By contrast, a substantial number of X-autosomal translocations result in POI. Breakpoints in X-autosomal cases of POI generally fall outside of genes [61] and far from any gene expressed in the ovary [62]. X-autosome chromosomes might instead have aberrant dynamic behavior [61]. This is also consistent with the selective increased risk of POI in women with deletions on the X (especially in Xq26-qter [63]), and with the suggestion that the notable decline in oocyte quality in the decade before menopause may result from increases in meiotic disjunction [64].

Turner syndrome.

One in 2000–5000 newborn girls [65] have part or all of one X chromosome missing, leading to the syndrome in which short stature and other phenotypes are accompanied by streak gonads, with loss of most to all oocytes by early adulthood. In addition to cases with one X chromosome (i.e., 45,X), over half of Turner patients have one of 16 chromosomal variants of X chromosome structure [66]. Consequently, the syndrome is rarely inherited. The effect on ovary function might again result from problems in chromosome dynamics, or from X gene dosage problems.

Fragile X syndrome premutation.

POI (“POF1” in OMIM 311360) has been consistently associated with women who have the “premutation” state of the Xq27.1 FMR1 gene (i.e., between 55 and 200 tandem copies of the CGG trinucleotide repeat in the gene). In two studies [67, 68], 3% of sporadic and 10%–13% of familial POI patients carried FRAXA premutations; in a more extensive follow-up, Murray et al. [69] found the permutation in 0.7% of 2000 women with early menopause and in 2% of women with POI (an odds ratio for POI of 5.4 compared with 0.4% in controls).

FMR1 has a primary effect in the brain [70], but is also implicated in the DNA damage response [71], and could thereby have a determinative effect on chromosome dynamics and oocyte stability. A similar POI phenotype is seen in FRAXE, associated with CGG triplet expansion in FMR2, in Xq28 [72]. In that study, additional microdeletions in FMR2 were found in 1.5% of POI individuals but only 0.04% of a general sample.

Other single-gene mutations.

Mutations in a variety of genes—both X-linked and autosomal—have been associated with sporadic cases of POI (Table 1). As indicated, frequencies are variable, and there is as yet no study in which mutations are systematically assessed for all the genes identified thus far.

TABLE 1.

Mutations in both X-linked and autosomal genes that have been associated with sporadic cases of POI.

Genetic Variants Associated with Regulation of Timing in Normal and Early Menopause: GWAS

In several studies, ∼50% of interindividual variability in menopausal age was inferred to be attributable to genetic variation [80, 81], and twin studies give estimates as high as 63% [82, 83]. As with other quantitative traits, a large number of DNA variants, each with relatively small effect size, are likely to underlie the high heritability of the age of menopause. Two large studies take pride of place, strongly implicating SNPs at 17 top loci. Most can be assigned to likely causative variants within a single gene or a few nearby genes.

The study of 17 438 women identified candidate genes MCM8, UIMC1/HK3, SYCP2L, and BRSK1 [84]. Three are plausibly expressed in the ovary—SYCP2L, involved in meiosis; UIMC1, also expressed in the pituitary-adrenal axis and acting as a transcriptional repressor; and MCM8, involved in DNA repair. BRSK1 seems a more remote candidate, affecting vesicle transport in neurons, and was later considered less likely than IL11 in a meta-analysis of 14 435 women from 22 genome-wide association studies [1].

Along with the 4 loci seen in the first study, Stolk et al. [1] inferred 13 additional loci with effects on the timing of menopause, with candidate genes known to be involved in DNA repair (EXO1, HELQ, UIMC1, FAM175A, FANCI, TLK1, POLG, and PRIM1) and immune function (IL11, NLRP11, and PRRC2A). Gene set enrichment analyses implicated mitochondrial dysfunction, exoDNAse, and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling. Low levels of mitochondrial function, which, like DNA repair, are associated with POLG activity, could speculatively cue cell turnover and increase follicle atresia and autophagy during the long interval of reserve storage, and NF-κB is deeply involved in cell death pathways as well as in the function of the immune system.

Interestingly, GWAS data provide a few hints of immune involvement in the timing of menopause [1]. Top signals included a coding variant in PRRC2A (encoding HLA-B transcript 2) and a coding variant in NLRP11 (encoding one of the NLRP protein components of inflammasomes, involved in the activation of inflammatory caspases). Another variant falls near IL11 (encoding a cytokine that stimulates B-cell development; suggestively, ablation of the cytokine receptor leads to infertility in female mice) [85].

As in other GWAS studies, the DNA variants revealed explained only part (up to 4.1%) of the variance of age of menopause in the populations studied. Nevertheless, their importance is increased by confirmatory GWAS findings in other ethnic groups (reviewed by [86]). Furthermore, other sources of variation, like the FRAXA expansion and FRAXE microdeletions, were not assessed, and analyses taking into account insertion/deletions and rare alleles and looking at larger cohorts will certainly explicate more of the genetic contribution to the timing of reproductive lifespan.

GWAS Variants Compared to POI Reports and “Candidate Genes”

Stolk et al. [1] also assessed possible associations in a group of 125 genes (their Supplementary Table 6), including all genes that had been suggested as candidates on the basis of ovary expression, mouse models, etc.—substantially overlapping the list assembled by Wood and Rajkovic [86], who also summarize substantial effects of many of the candidate genes in mice. Instead, the GWAS hits were startlingly different from the candidate gene list. Apart from four genes already found in the GWAS, only one gene, DMC1, reached nominal significance. DMC1 is a plausible candidate, because it functions in meiotic recombination and is expressed under the control of NOBOX (also associated with sporadic POI; Table 1).

POLG was the only gene initially found in which strongly deleterious mutations cause POI and other variants have less strong effects on the timing of menopause. Even genes mutated in Mendelian disorders that cause POI as a major feature, like FOXL2 lesions in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome [87], have no reported variants associated with modest changes in the timing of menopause. However, in a larger study, Perry et al. [88] now find that many variants associated with timing of typical menopause are also associated with early menopause (before age 45) and possibly with POI. Thus, POI reflects the risk both from the variants assessed by GWAS and from severe changes in often distinct genes involved in maintenance of stable reproduction.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL FACTORS AFFECTING AGE OF MENOPAUSE

INTRODUCTION

Most epidemiologic research on factors associated with age of menopause and early menopause has relied on self-reported age at cessation of periods collected retrospectively or concurrently in cross-sectional or prospective longitudinal studies. In addition to the shortcomings of retrospective self-report, another limitation concerns the wide variation across cohorts in rates of natural menopause, initiation of hormone therapy prior to natural menopause, and surgically determined menopause. Depending on the population, the proportion of women experiencing natural menopause can be less than 50% [89, 90]. For example, in the British birth cohort study of 1583 women, by age 57 yr, 695 (44%) had experienced natural menopause, 431 (27%) had started hormone therapy prior to natural menopause, 347 (22%) had undergone hysterectomy, and 110 (7%) had incomplete data or were using oral contraceptives [91]. Because the socio-demographic, social-environmental, and behavioral attributes of women experiencing these alternate pathways to menopause differ, studies of age of natural menopause are often restricted to nonrepresentative samples [89]. Additionally, not all studies are well designed and few can clearly distinguish cause and effect (e.g., parity). Discerning the direction of association is particularly challenging because even though menopause is typically considered as a single event analytically, it is more appropriately described as a process that can extend well over a decade. Lastly, studies of relatively rare exposures or conditions (e.g., specific autoimmune diseases, cancers and their treatments) are often underpowered. Nevertheless, population-based and case-control epidemiologic studies provide the basis for much of our knowledge of threats to reproductive health.

Biological measures of ovarian reserve such as follicular-stimulating hormone, antral follicle count (AFC), and AMH have been utilized with increasing frequency in epidemiologic studies of reproductive health, with AMH showing great promise as it is more stable across the menstrual cycle and not labor intensive [92]. Results differ using different kits [93], however, and AMH is elevated in polycystic ovary syndrome, which often accompanies autoimmune conditions [94].

Below we briefly summarize the epidemiologic research on age of menopause incorporating findings on biologic measures of ovarian reserve where applicable.

Effects of Specific Epidemiological Factors

Lifestyle.

Cigarette smoking is the most established and consistently observed risk factor for younger age at menopause, with estimates of impact on the order of about 1 yr [95–97] with a clear dose-response association [89, 98, 99]. Supporting these findings, recent work found current smokers had lower AMH levels than nonsmokers [100] and AMH was lower and declined more steeply in smokers beginning 13 yr before the final menstrual period [101]. In the largest population-based study of AMH, involving 2320 premenopausal women, current but not past smoking was associated with a lower age-specific AMH percentile, although pack-years among current and past smokers exhibited a dose-response relationship [102].

Findings regarding other lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption and physical activity have been less uniform [90, 95, 96, 103, 104]. Nonetheless, large or combined cohort studies typically find women with higher and lower socioeconomic status to have respectively an older and younger average age of menopause [89, 98, 103, 105, 106]. Other resource-related factors such as oral contraceptive use and parity and weight-related issues are discussed below. In the study examining AMH levels in over 2300 premenopausal women, only smoking exposure, oral contraceptive use, and parity—and not alcohol consumption, physical exercise, socioeconomic status, or body composition measured as body mass index (BMI) or waist circumference—were associated with age-specific AMH percentile [102].

Prenatal nutrition, birth weight, and early-life exposures.

Because the primordial follicle pool reaches its maximum during gestation, birth weight and other neonatal circumstances have been examined for their association with menopause status. In the British cohort study, women with low (<2.5 kg) or high birth weight (>4.0 kg) or high birth weight standardized for gestational age had higher odds (1.8–1.9) of being postmenopausal by age 44–45 yr than women of average birth weight [107]. In the same cohort, neither breastfeeding status nor weight at age 2 were found to be important [91]. Exposure to famine during gestation, but not birth weight, was associated with an earlier age of menopause in the Dutch famine study of 376 women [108]. In over 22 000 primarily white well-educated women, in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol was associated with earlier menopause, and low birth weight (<2.5 kg) had a suggestive association [109].

Adult weight.

Findings examining relative weight or body mass index have been inconsistent because of suboptimal study design, with widely differing study populations with respect to ethnicity, culture, and analytic approach. Thus, some studies find no association between body mass and age of menopause [89, 105], whereas others find higher body mass associated with later menopause or alternatively lower relative weight associated with earlier menopause [98]. In contrast, a large European study found BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 associated with earlier menopause [90]. One of the few studies with a life-course perspective found underweight (BMI <20 kg/m2) at age 36 modestly associated with a younger age of menopause compared to all other BMI groups combined [91]. The larger and more consistent association, however, is between underweight and greater use of hormone therapy prior to menopause, which was investigated separately from natural menopause. Lastly, to add to the inconsistent findings, one study examining AMH levels in late reproductive age found obese women had lower levels [110] and another found no association [101].

Parity and oral contraceptive use.

Consistent with the notion that reduced ovulation might effectively extend reproductive life, parity is often found positively associated with later age of menopause [90, 105], but arguably early menopause could drive lower parity. For example, using cross-sectional data, the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation found parity associated with an older age at menopause [89], but the longitudinal analysis did not support this observation [98]. Nevertheless, oral contraceptive use and later menopause has been consistently observed [89, 95, 98, 105, 111], and the association between longer cycle length and later menopause also supports a relationship between lifetime ovulatory cycles and age of menopause [95].

Epidemiology of Autoimmune Association.

Ovarian autoimmunity has recently been suggested as having a specific role in the etiology of POI [112, 113]. From 10% up to 30% of POI cases have an autoimmune condition [114–116], and some DNA variants in immune system genes affect the age of menopause, though only about 5% of POI cases are considered to have autoimmune oophoritis [116, 117]. The strongest associations are with aggressive autoimmune conditions such as Addison disease (OMIM 240200), myasthenia gravis (OMIM 254200), and autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy, caused by mutations in the AIRE gene [116, 118]. In one other instance, in a case-control study, lower AMH was found in women with Takayasu arteritis independent of treatment with gonadotoxic drugs, though FSH did not differ [93]. Also, women with Turner syndrome and women with karyotypically normal POI demonstrate greater prevalence of Hashimoto thyroiditis, 37% and 15%, respectively, than the general U.S. female population (6%) [119]. With respect to age of menopause excluding POI, no convincing data support a primary association between systemic autoimmune disorders such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis and earlier age of menopause. Thus, autoimmune antibodies often observed in POI [120–126] as well as in those with incipient menopause around age 50 [127] suggest an interactive phenomenon resulting from aging-related inflammation, immunosenescence, and hormonal changes. Additional studies are needed to ascertain the impact of autoimmunity on the onset of POI, and most importantly to assess if autoantibodies accompany rather than cause POI. In addition, some immune genetic variation contributes to the normal range of age of menopause [1].

Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance.

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) has been rarely evaluated as a risk factor for POI or early menopause, in part because T2DM rarely emerges before age 40, but a large cross-sectional multinational study in Latin American Hispanic women aged 40–58 found those with T2DM had a nearly 3-fold increased likelihood of having menopause before age 45 relative to nondiabetic women [128]. Consistent with this observation, a study tracking AMH over 13 yr found an increasingly higher HOMA-IR (homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance, a model for measuring insulin resistance and β-cell function) associated with closer time to the final menstrual period [101].

Cancer and cancer treatment.

Chemotherapy has been consistently shown to negatively impact reproductive health; a recent review of studies using AMH among other measures of ovarian reserve pretreatment and posttreatment confirms the treatment effects, but also highlights hematological cancers (e.g., lymphoma) as having a direct effect on ovarian reserve [129]. Additionally, although a drastic reduction in AMH is consistently observed immediately after treatment initiation whether or not alkylating agents are used, the pattern of ovarian recovery differs with treatment regimen [129]. Most studies find women treated with alkylating agents continue to have low or undetectable AMH levels through follow-up, whereas women treated with nonalkylating agents recover pretreatment levels within 6 mo. This general impression is echoed in a study of ovarian reserve in young women treated for cancer in childhood, which found sustained low levels of AMH in those treated with high gonadotoxic agents, whereas those treated with less gonadotoxic agents had only slightly lower levels than controls [130]. Another case-control study of cancer survivors substantiates the observation that exposure to alkylating agents and pelvic radiation are associated with reduced ovarian reserve, as evidenced by higher FSH and lower AMH and AFC [131] in cases versus controls.

Other chemical exposures.

The most-well-studied chemical exposures largely concern treatment of autoimmune conditions—such as lupus with cyclophosphamide, which has been found to affect risk of POI and age of menopause. Cyclophosphamide has been associated with follicular death and ovarian failure due to the mechanism of action of its metabolite, phosphoramide mustard, which causes apoptosis by crosslinking DNA. Age at treatment initiation and treatment duration as well as genetic and environmental factors appear to modify the association [132]. In a case-control study of ovarian reserve, women with childhood-onset lupus (n = 57) had lower AMH and AFC than controls (n = 21), but the difference may be driven by the effect of cyclophosphamide on ovarian reserve in treated cases [133]. In 19 cases treated exclusively with methotrexate, a DNA-synthesis inhibitor and receptor antagonist, cumulative dose was negatively associated with AMH [133].

The literature is less well developed for other agents, and most work has been done in experimental animal-based studies. The few human observational studies have identified two potential toxic agents: 2-bromopropane and cadmium [134]. Human research on the reproductive effects of bisphenol A indicates a possible increased risk of polycystic ovary syndrome and poorer oocyte quality and ovarian function [135], but evidence of impact on age of menopause or risk of POI remains inconclusive [136].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION, EVALUATION, AND TREATMENT OF POI

Balen [137] provides a magisterial discussion of POI in the context of infertility. Here we focus on the standing of genetic and epidemiological factors in current practice.

Although there are no definite diagnostic criteria for POI, operational criteria exclude chemotherapy, pelvic radiotherapy, and oophorectomy [138], and include menstrual irregularities for at least 4 mo (amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, polymenorrhea, metrorrhagia); climacteric symptoms; and elevated FSH in the menopausal range at least twice 1 mo apart below age 40. Infertility is a first indication, but POI can develop either gradually or suddenly.

POI can be sporadic or familial, primary or secondary, syndromic or nonsyndromic, and follicular or afollicular [139]. Cases with clear causation help in genetic counseling and in identifying other family members who may be at risk [140].

Particular attention must be paid to adolescents with menstrual irregularities, when early diagnosis of POI can help prevent adverse health consequences and, importantly, preserve fertility. The usual presentation is primary amenorrhea, and karyotype, 21-hydroxylase antibodies, FMR1 premutation status [140], and associated phenotypes like fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome are assessed [141–144]. For secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy test, biological autoimmune profile (anti-thyroid, anti-adrenal, and anti-parathyroid antibodies), TSH, FSH, LH, prolactin, and ovarian ultrasound are added to the clinical examination [57].

Nelson [145] has pointed out that for sporadic POI, referral to genetic research groups can now provide screening for mutations in candidate genes or even genomic DNA sequencing where familial data suggest a genetic cause.

Genetic counseling is mandatory, especially for fragile X-associated ovarian insufficiency, so that affected women will know about transmission of either the normal or the premutation allele and the likelihood of expansion of the premutation allele and its consequences. Additional management is personalized. In particular, young women with POI will have estrogen deficiency longer than women with natural menopause, significantly increasing osteoporosis and risk for cardiovascular disease [146]. Calcium and vitamin supplements and bone-density surveillance are standard [147].

It is important to inform patients that there is a 5%–10% chance of spontaneous recovery of ovarian function, increasing the likelihood of women choosing oral contraceptive use. Each patient also requires support to cope with anger, depression, and emotional stress; but the overriding effect of POI remains infertility. Currently, therapeutic alternatives for those with some residual reserve (or patients preparing for chemotherapy or radiotherapy) include ovary overstimulation with gonadotropins and in vitro fertilization, oocyte cryopreservation, and ovarian tissue or embryo cryopreservation. The options to preserve fertility for women at intrinsic risk of POI are dependent on the remaining follicle reserve, and can therefore be optimized by early diagnosis. Currently, POI is usually diagnosed after the fact—too late for many interventions; but women with a positive family history can be followed more closely, and several biochemical markers may provide a route to much earlier identification of early menopause in the general population as well. Markers that could be part of standard checkups include AMH, the hormone that changes earliest in the progression to normal menopause or POI.

CONCLUSIONS

The genetic and epidemiological factors affecting timing of menopause are increasingly known, and the extent to which they can account for the risk of early menopause and POI can now be more systematically evaluated in individuals and populations. Genetics points to possible eventual intervention in DNA repair and atresia-related processes that determine the conservation of follicles. Notably, the same genetic factors and remediable epidemiological factors, like smoking, likely also affect the progressive decline of oocyte quality up to 10 yr or more before menstruation ceases [148]. Such considerations reinforce the importance of early diagnosis, perhaps using measures like AMH levels, to promote optimization of reproductive life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank C. Ottolenghi for discussion.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

REFERENCES

- Stolk L, Perry JR, Chasman DI, He C, Mangino M, Sulem P, Barbalic M, Broer L, Byrne EM, Ernst F, Esko T, Franceschini N, et al. Meta-analyses identify 13 loci associated with age at menopause and highlight DNA repair and immune pathways. Nat Genet. 2012;44:260–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt CK. Primary ovarian insufficiency: a more accurate term for premature ovarian failure. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield AN. Development of follicles in the mammalian ovary. Int Rev Cytol. 1991;124:43–101. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia SV. Serra GB (ed.), The Ovary. New York: Raven Press; 1983. Morphological changes of the human ovary throughout life; pp. 57–81. In. [Google Scholar]

- Ottolenghi C, Uda M, Hamatani T, Crisponi L, Garcia JE, Ko M, Pilia G, Sforza C, Schlessinger D, Forabosco A. Aging of oocyte, ovary, and human reproduction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1034:117–131. doi: 10.1196/annals.1335.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu HP, Liao Y, Novak JS, Hu Z, Merkin JJ, Shymkiv Y, Braeckman BP, Dorovkov MV, Nguyen A, Clifford PM, Nagele RG, Harrison DE, et al. Germline quality control: eEF2K stands guard to eliminate defective oocytes. Dev Cell. 2014;10:561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni L, Upadhyay S, Bezard J, Luciani JM, Mauleon P. The role of the mesonephros in the development of the mammalian ovary. In: Tozzini RI, Reeves G, Pineta RL, editors. Endocrine Physiopathology of the Ovary. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland Biomedical Press; 1980. pp. 3–42. In. (eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Lintern-Moore S, Peters H, Moore GPM, Faber M. Follicular development in the infant human ovary. J Reprod Fertil. 1974;39:53–64. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0390053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforza C, Ferrario VF, De Pol A, Marzona L, Forni M, Forabosco A. Morphometric study of the human ovary during compartmentalization. Anat Rec. 1993;236:626–634. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pol A, Marzona L, Vaccina F, Negro R, Sena P, Forabosco A. Apoptosis in different stages of human oogenesis. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3457–3461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaskivuo TE, Anttonen M, Herva R, Billig H. Dorland M. te Velde ER Stenbäck F, Heikinheimo M, Tapanainen JS. Survival of human ovarian follicles from fetal to adult life: apoptosis, apoptosis related proteins, and transcription factor GATA-4. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3421–3429. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya C, Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Hobbs RJ, Gerasimova T, Uyar A, Erdem M, Oktem M, Erdem A, Gumuslu S, Ercan D, Sakkas D, Comizzoli P, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) alternative skipping of exon 2 or 3 affects ovarian response to FSH. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:630–643. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervásio CG, Bernuci MP, Silva-de-Sá MF, Rosa-E-Silva AC. The role of androgen hormones in early follicular development. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:818010. doi: 10.1155/2014/818010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rama Raju GA, Chavan R, Deenadayal M, Gunasheela D, Gutgutia R, Haripriya G, Govindarajan M, Patel NH, Patki AS. Luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone synergy: a review of role in controlled ovarian hyper-stimulation. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2013;6:227–234. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.126285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makanji Y, Harrison CA, Robertson DM. Feedback regulation by inhibins A and B of the pituitary secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone. Vitam Horm. 2011;85:299–321. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385961-7.00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight PG, Glister C. Local roles of TGF-beta superfamily members in the control of ovarian follicle development. Anim Reprod Sci. 2003;78:165–183. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(03)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliodromiti S, Nelson SM. Biomarkers of ovarian reserve. Biomark Med. 2013;1:147–158. doi: 10.2217/bmm.12.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer SL, Broekmans FJM, Laven JS, Fauser BCJM. Human anti-Mullerian hormone: ovarian reserve testing and its potential clinical implications. Reprod Update. 2014;20:688–701. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forabosco A, Sforza C. Establishment of ovarian reserve: a quantitative morphometric study of the developing human ovary. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SJ, Senikas V, Nelson JF. Follicular depletion during the menopausal transition: evidence for accelerated loss and ultimate exhaustion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:1231–1237. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-6-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ, Gosden RG. A model conforming the decline in follicle numbers to the age of menopause in women. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1484–1486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi E, Omari S, Michel M, Ding J, Amano T, Forabosco A, Schlessinger D, Ottolenghi C. Constitutively active Foxo3 in oocytes preserves ovarian reserve in mice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1843. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ, Gosden RG. A mathematical model of follicle dynamics in the human ovary. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:770–775. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coucouvanis EC, Sherwood SW, Carswell-Crumpton C, Spack EG, Jones PP. Evidence that the mechanism of prenatal germ cell death in the mouse is apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 1993;209:238–247. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce M, De Felici M. Apoptosis in mouse primordial germ cells: a study by transmission and scanning electron microscope. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1994;189:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00185438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeleznik AJ, Benyo DF. Control of follicular development, corpus luteum function, and the recognition of pregnancy in higher primates. In: Knobil E, Neill J, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 751–782. In. (eds.) [Google Scholar]

- diZerega GS, Hodgen GD. Folliculogenesis in the primate ovarian cycle. Endocr Rev. 1981;2:27–49. doi: 10.1210/edrv-2-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol-Gould SK, Kreeger PK, Selkirk CG, Kilen SM, Cook RW, Kipp JL, Shea LD, Mayo KE, Woodruff TK. Postnatal regulation of germ cells by activin: the establishment of the initial follicle pool. Dev Biol. 2006;298:132–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ, Telfer E, Gosden RG. The kinetics of pre-antral follicle development in ovaries of CBA/Ca mice during the first 14 weeks of life. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1987;20:551–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1987.tb01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine PJ, Payne CM, McCuskey MK, Hoyer PB. Ultrastructural evaluation of oocytes during atresia in rat ovarian follicles. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1245–1252. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues P, Limback D, McGinnis LK, Plancha CE, Albertini DF. Multiple mechanisms of germ cell loss in the perinatal mouse ovary. Reproduction. 2009;137:709–720. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingen CM, Bristol-Gould SK, Kiesewetter SE, Wellington JT, Shea L, Woodruff TK. Prepubertal primordial follicle loss in mice is not due to classical apoptotic pathways. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:16–25. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.074898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman S. The numbers of ococytes in the mature ovary. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1951;6:63–109. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru JK, Tilly JL. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White YA, Woods DC, Takai Y, Ishihara O, Seki H, Tilly JL. Oocyte formation in mitotically active germ cells purified from ovaries of reproductive-age women. Nat Med. 2012;18:413–421. doi: 10.1038/nm.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Fouad H, Zoma WD, Salama SA, Wentz MJ, Al-Hendy A. Expression of stem and germ cell markers within nonfollicle structures in adult mouse ovary. Reprod Sci. 2008;15:139–146. doi: 10.1177/1933719107310708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiarotti J, Maki C, Ramos T, Marh J, Howerton K, Wong J, Pham J, Anorve S, Chow YC, Izadyar F. Differentiation potential of germ line stem cells derived from the postnatal mouse ovary. Differentiation. 2010;79:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S, Papaioannou VE, Gosden RG. The oocyte population is not renewed in transplanted or irradiated adult ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2326–2330. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byskov AG, Høyer PE. Yding Andersen C, Kristensen SG, Jespersen A, Møllgård K. No evidence for the presence of oogonia in the human ovary after their final clearance during the first two years of life. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2129–2139. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zheng W, Shen Y, Adhikari D, Ueno H, Liu K. Experimental evidence showing that no mitotically active female progenitors exist in post natal mouse ovaries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12580–12585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L, Spradling AC. Female mice lack adult germ-line stem cells but sustain oogenesis using stable primordial follicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8585–8590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306189110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambalk CB, de Koning CH, Flett A, van Kasteren Y, Gosden R, Homburg R. Assessment of ovarian reserve. Ovarian biopsy is not a valid method for the prediction of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1055–1059. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforza C, Vizzotto L, Ferrario VF, Forabosco A. Position of follicles in normal human ovary during definitive histogenesis. Early Hum Dev. 2003;74:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(03)00081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt KL, Byskov AG. Nyboe Andersen A, Muller J, Yding Andersen A. Density and distribution of primordial follicles in single pieces of cortex from 21 patients and in individual pieces of cortex from three entire human ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1158–1164. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly JL. Ovarian follicle counts—not as simple as 1, 2, 3. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block EA. Quantitative morphological investigations of the follicular system in newborn female infants. Acta Anat. 1953;17:201–206. doi: 10.1159/000140805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block E. Quantitative morphological investigations of the follicular system in women; variations at different ages. Acta Anat. 1952;14:108–123. doi: 10.1159/000140595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gougeon A, Ecochard R, Thalabard JC. Age-related changes of the population of human ovarian follicles: increase in the disappearance rate of non-growing and early-growing follicles in aging women. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:653–663. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KR, Knowlton NS, Thyer AC, Charleston JS, Soules MR, Klein NA. A new model of reproductive aging: the decline in ovarian non-growing follicle number from birth to menopause. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:699–708. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ, Gosden RG, Gougeon A, Richardson SJ, Nelson JF. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1342–1346. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy MJ. Follicle dynamics during ovarian ageing. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;163:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxworth JE, Hawkes K. Ovarian follicle loss in humans and mice: lessons from statistical model comparison. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1796–1805. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace WH, Kelsey TW. Human ovarian reserve from conception to the menopause. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamsen LS, Lutterodt MC, Andersen EW, Byskov AG, Andersen CY. Germ cell numbers in human embryonic and fetal gonads during the first two trimesters of pregnancy: analysis of six published studies. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2140–2145. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TG. A quantitative and cytological study of germ cells in human ovaries. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1963;158:417–433. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1963.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Spradling AC. Fusome asymmetry and oocyte determination in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1995;16:6–12. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020160104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin-Maitre S, Braham R. General mechanisms of premature ovarian failure and clinical check-up. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2008;36:857–861. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricaire L, Laroche E, Bourcigaux N, Donadille B, Chrisin-Maitre S. Premature ovarian failures. Presse Med. 2013;42:1500–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic A. Genetics of ovarian failure and development. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:223–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-980215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Short communications chromosome abnormalities found among 34 910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus, Denmark. Hum Genet. 1991;87:81–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01213097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger D, Herrera L, Crisponi L, Mumm S, Percesepe A, Pellegrini M, Pilia G, Forabosco A. Genes and translocations involved in POF. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:328–333. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolio F, Sala C, Alboresi S, Bione S, Gilli S, Googan M, Pramparo T, Zuffardi O, Toniolo D. Epigenetic control of the critical region for premature ovarian failure on autosomal genes translocated to the X chromosome: a hypothesis. Hum Genet. 2007;121:441–450. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0329-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer CL, Lachlan K, Karcanias A, Affara N, Huang S, Jacobs PA, Thomas NS. Detailed clinical and molecular study of 20 females with Xq deletions with special reference to menstruation and fertility. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeksman FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 1998;30:1119–1125. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenger P. Sperling M . Pediatric Endocrinology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. Turner syndrome; pp. 664–697. In. (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Hook EB, Warburton D. Turner syndrome revisited: review of new data supports the hypothesis that all viable 45,X cases are cryptic mosaics with a rescue cell line, implying an origin by mitotic loss. Hum Genet. 2014;133:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodega B, Bione S, Dalpra L, Toniolo D, Ornaghi F, Vegetti W, Ginelli E, Marozzi A. Influence of intermediate and uninterrupted FMR1 CCG expansions in premature ovarian failure manifestation. Hum Reprod. 2006;14:952–957. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway GS, Payne NN, Webb J, Murray A, Jacobs PA. Fragile X premutation screening in women with premature ovarian failure. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1184–1188. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.5.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A, Schoemaker MJ, Bennett CE, Ennis S, Macpherson JN, Joones M, Morris DH, Orr N, Ashworth A, Jacobs PA, Swerdlow AJ. Population-based estimates of the prevalence of FMR1 expansion mutations in women with early menopause and primary ovarian insufficiency. Genet Med. 2014;16:19–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braat S, Kooy RF. Insights into GABAergic system deficits in fragile X syndrome lead to clinical trials. Neuropharmacology. 2015;88C:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpatov R, Lesch BJ, Nakamoto-Kinoshita M, Blanco A, Chen S, Stützer A, Armache KJ, Simon MD, Xu C, Ali M, Murn J, Prisic S, et al. A chromatin-dependent role of the fragile X mental retardation protein FMRP in the DNA damage response. Cell. 2014;157:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A, Webb J, Dennis N, Conway G, Morton N. Microdeletions in FMR2 may be a significant cause of premature ovarian failure. J Med Genet. 1999;36:767–770. doi: 10.1136/jmg.36.10.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Jiao X, Dalgleish R, Vujovic S, Li J, Simpson JL, Al-Azzawi F, Chen ZJ. Novel variants in the SOHLH2 gene are implicated in human premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1104–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries L, Behar DM, Smirin-Yosef P, Lagovsky I, Tzur S, Basel-Vanagaite L. Exome sequencing reveals SYCE1 mutation associated with autosomal recessive primary ovarian insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E2129–E2132. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasippilai T, MacArthur DG, Kirby A, Thomas B, Lambalk CB, Daly MJ, Welt CK. Mutations in eIF4ENIF1 area associated with primary ovarian insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1534–E1539. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AJ, Knight JA, Costello H, Conway GS, Rahman S. POLG mutations and age at menopause. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2243–2244. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aittomaki K, Lucena JLD, Pakarinen P, Sistonen P, Tapanaine J, Gromoll J, Kaskikari R, Sankila E-M, Lehvaslaiho H, Engel AR, Nieschlag E, Huhtaniemei I, et al. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell. 1995;82:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhangoo A, Buyuk E, Oktay K, Ten S. Phenotypic features of 46, XX females with StAR protein mutations. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2007;5:633–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangen D, Kaufman Y, Zeligson S, Perlberg S, Fridman H, Kanaan M, Abdulhadi-Atwan M, AbuLibdeh A, Gussow A, Kisslov I, Carmel L, Renbaum P, et al. XX ovarian dysgenesis is caused by a PSMC3IP/HOP2 mutation that abolishes coactivation of estrogen-driven transcription. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murabito JM, Yang Q, Fox C, Wilson PWF, Cupples LA. Heritability of age at natural menopause in the Framingham heart study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3427–3430. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Asselt KM, Kok HS, Pearson PL, Dubas JS, Peeters PH, Te Velde ER, van Noord PA. Heritability of menopausal age in mothers and daughters. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1348–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snieder H, MacGregor AJ, Spector TD. Genes control the cessation of a woman's reproductive life: a twin study of hysterectomy and age at menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1875–1880. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink J, Boomsma D. Modeling age at menopause. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1068. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Kraft P, Chen C, Buring JE, Parc G, Hankinson SE, Chanock SJ, Ridker PM, Hundeter DJ, Chasman DI. Genome-wide association studies identity loci associated with age at menarche and age at natural menopause. Nat Genet. 2009;41:724–728. doi: 10.1038/ng.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb L, Li R, Hartley L, Nandurkar HH, Koentgen F, Begley CG. Infertility in female mice lacking the receptor for interleukin 11 is due to a defective uterine response to implantation. Nat Med. 1998;4:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MA, Rajkovic A. Genomic markers of ovarian reserve. Semin Reprod Med. 2013;31:399–415. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisponi L, Deiana M, Loi A, Chiappe F, Uda M, Amati P, Bisceglia L, Zelante L, Nagaraja R, Porcu S, Ristaldi MS, Marzella R, et al. The putative forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is mutated in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:159–166. doi: 10.1038/84781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JRB, Corre T, Esko T, Chasman DI, Fischer K, Franceschini N, He C, Kutalik Z, Mangino M, Rose LM, VernonSmith A, Stolk L, et al. A genome-wide association study of early menopause and the combined impact of identified variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1465–1473. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, Samuels S, Greendale GA, Harlow SD, Skurnick J. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:865–874. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.9.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dratva J, Real FG, Schindler C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Gerbase MW, Probst-Hensch NM, Svanes C, Omenaas ER, Neukirch F, Wjst M, Morabia A, Jarvis D, et al. Is age at menopause increasing across Europe? Results on age at menopause and determinants from two population-based studies. Menopause. 2009;16:385–394. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818aefef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Mishra GD, Kuh D. Body mass index and age at menopause in a British birth cohort. Maturitas. 2008;59:304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Disseldorp J, Faddy MJ, Themmen APN, de Jong FH, Peeters PHM, van der Schouw YT, Broekmans FJM. Relationship of serum antimüllerian hormone concentration to age at menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2129–2134. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mont'Alverne ARS, Pereira RMR, Yamakami LYS, Viana VST, Baracat EC, Bonfá E, Silva CA. Reduced ovarian reserve in patients with Takayasu arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:2055–2059. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuten A, Hatipoglu E, Oncul M, Imamoglu M, Acikgoz AS, Yilmaz N, Ozcil MD, Kaya B, Misirlioglu AM, Sahmay S. Evaluation of ovarian reserve in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30:708–711. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.926324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, Signorello LB. Factors associated with early menopause. Maturitas. 2000;35:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney A, Kline J, Alcohol Levin B. caffeine and smoking in relation to age at menopause. Maturitas. 2006;54:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Tan L, Yang F, Luo Y, Li X, Deng H-W, Dvornyk V. Meta-analysis suggests that smoking is associated with an increased risk of early natural menopause. Menopause. 2012;19:126–132. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318224f9ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold EB, Crawford SL, Avis NE, Crandall CJ, Mattews KA, Waetjen LE, Lee JS, Thurston R, Vuga M, Harlow SD. Factors related to age at natural menopause: longitudinal analyses from SWAN. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:70–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhah MR, Clavarino A, Williams GM, Sina M, Najman JM. Cigarette smoking and age of menopause: a large prospective study. Maturitas. 2012;72:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante BJ, Cooper GS, Baird DD, Steiner AZ. The impact of smoking on antimüllerian hormone levels in women aged 38 to 50 years. Menopause. 2010;17:571–576. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c7deba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers MR, McConnell D, Yosef M, Jannausch ML, Harlow SD, Randolph JF., Jr. Relating smoking, obesity, insulin resistance, and ovarian biomarker changes to the final menstrual period. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1204:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dólleman M, Verschuren WMM, Eijkemans MJC, Dollé MET, Jansen EHJM, Broekmans FJM, van der Schouw YT. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-müllerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2106–2115. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano E, Galasso R, Berrino F, Fusconi E, Giurdanella MC, Tumino R, Sacerdote C, Fiorini L, Ciardullo AV, Mattiello A, Palli D, Masala G, et al. Correlates of age at natural menopause in the cohorts of EPIC-Italy. Tumori. 2003;89:608–614. doi: 10.1177/030089160308900604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elavsky S, Gonzales JU, Proctor DN, Williams N, Henderson VW. Effects of physical activity on vasomotor symptoms: examination using objective and subjective measures. Menopause. 2012;19:1095–1103. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824f8fb8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek M. The timing of natural menopause in Poland and associated factors. Maturitas. 2007;57:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoto R, Kaprio J, Uutela A. Age at natural menopause and sociodemographic status in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:64–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom SE, Cooper R, Kuh D, Guralnik JM, Hardy R, Power C. Fetal environment and early age at natural menopause in a British birth cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:791–798. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarde F, Broekmans FJM, van der Pal-de-Bruin KM, Schönbeck Y, Te Velde ER, Stein AD, Lumey LH. Prenatal famine, birthweight, reproductive performance and age at menopause: the Dutch hunger winter families study. Hum Reprod. 2013;38:3328–3336. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner AZ, D'Aloisio AA, DeRoo LA, Sandler DP, Baird DD. Association of intrauterine and early-life exposures with age at menopause in the Sister Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:140–148. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Garcia CR, Sammel MD, Lin H, Lim LC-L, Strauss JF., III Association of anti-mullerian hormone levels with obesity in late reproductive-age women. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noord PA, Dubas JS, Dorland M, Boersma H, te Velde E. Age at natural menopause in a population-based screening cohort: the role of menarche, fecundity, and lifestyle factors. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MH, Nelson LM. Mechanisms and models of immune tolerance breakdown in the ovary. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:308–316. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falorni A, Brozzetti A, Aglietti MC, Esposito R, Minarelli V, Morelli S. Sbroma Tomaro E, Marzotti S. Progressive decline of residual follicle pool after clinical diagnosis of autoimmune ovarian insufficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;77:453–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meskhi A, Seif MW. Premature ovarian failure. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18:418–426. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000233937.36554.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calongos G, Hasegawa A, Komori S, Koyama K. Harmful effects of antizona pellucida antibodies in folliculogenesis, oogenesis, and fertilization. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;79:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva CA, Yamakami LYS, Aikawa NE, Araujo DB, Carvalho JF, Bonfá E. Autoimmune primary ovarian insufficiency. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek A, Schoemaker J, Drexhage HA. Premature ovarian failure and ovarian autoimmunity. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:107–134. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perheentupa J. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy–candidiasis–ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) Horm Metab Res. 1996;28:353–356. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalov VK, Gutin L, Cheng CM, Zhou J, Sheth P, Shah K, Arepalli S, Vanderhoof V, Nelson LM, Bondy CA. Autoimmune disorders in women with turner syndrome and women with karyotypically normal primary ovarian insufficiency. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller-Kikkatalo K, Salumets A, Uibo R. Review on autoimmune reactions in female infertility: antibodies to follicle stimulating hormone. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:762541. doi: 10.1155/2012/762541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fénichel P, Sosset C, Barbarino-Monnier P, Gobert B, Hieronimus S, Bene MC, Hartet M. Prevalence, specificity and significance of ovarian antibodies during spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Hum Reprod. 1995;12:2623–2628. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.12.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky JL, Visintin I, Boyers S, Asari T, Caldwell B, DeCherney A. Ovarian antibodies detected by immobilized antigen immunoassay in patients with premature ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:69–75. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar RL, Meherji PK, Kadam SS, Gupta SK, Nandedkar TD. Circulating auto-antibodies against the zona pellucida and thyroid microsomal antigen in women with premature ovarian failure. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;66:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky J, Llanes B, Davies S, Binor Z, Radwanska E, Pong R. Ovarian autoimmunity: greater frequency of autoantibodies in premature menopause and unexplained infertility than in the general population. Clin Immunol. 1999;90:368–374. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen X, Qiao J, Li R, Wang L, Liu P. Serologic autoimmunologic parameters in women with primary ovarian insufficiency. BMC Immunol. 2014;15:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-15-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Košir Pogačnik R, Meden Vrtovec H, Vizjak A, Uršula Levičnik A, Slabe N, Ihan A. Possible role of autoimmunity in patients with premature ovarian insufficiency. Int J Fertil Steril. 2014;7:281–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kasteren YM, von Blomber M, Hoek A, de Koning C, Lambalk N, van Montfrans J, Kuik J, Schoemaker J. Incipient ovarian failure and premature ovarian failure show the same immunological profile. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2000;43:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2000.430605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterrosa-Castro A, Blümel JE, Portela-Buelvas K, Mezones-Holguín E, Barón G, Bencosme A, Benítez Z, Bravo LM, Calle A, Chedraui P, Flores D, Espinoza MT, et al. Type II diabetes mellitus and menopause: a multinational study. Climacteric. 2013;16:663–672. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2013.798272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peigné M, Decanter C. Serum AMH level as a marker of acute and long-term effects of chemotherapy on the ovarian follicular content: a systematic review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczuk-Rybak M, Leszcynska E, Poznanska M, Zelazowska-Rutkowska B, Wysocka J. The progressive reduction in the ovarian reserve in young women after anticancer treatment. Horm Metab Res. 2013;45:813–819. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia CR, Sammel MD, Freeman E, Prewitt M, Carlson C, Ray A, Vance A, Ginsberg JP. Impact of cancer therapies on ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammaritano LR. Menopause in patients with autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:M430–M436. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo DB, Yamakami LYS, Aikawa NE, Bonfá E, Viana VST, Pasoto SG, Pereira RMR, Serafin PC, Borba EF, Silva CA. Ovarian reserve in adult patients with childhood-onset lupus: a possible deleterious effect of methotrexate? Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;2:1–9. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2014.908237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béranger R, Hoffmann P, Christin-Maitre S, Bonneterre V. Occupational exposures to chemicals as a possible etiology in premature ovarian failure: a critical analysis of the literature. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta D, Di Segni N, Mallozzi M, Giovanale V, Mantovani A, Marci R, Moscarini M. Bisphenol A and the female reproductive tract: an overview of recent laboratory evidence and epidemiologic studies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz J, Vrooman L, Ricke WA, Hunt PA, Ehrlich S, Hauser R, Padmanabhan V, Taylor HS, Swan SH, VandeVoort CA, Flaws JA., Bisphenol A. and reproductive health: update of experimental and human evidence, 2007–2013. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:775–786. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balen AH. Infertility in Practice, 2nd ed. London: CRC Press, Informa Healthcare; 2014. Premature ovarian insufficiency (failure) and oocyte donation; pp. 239–250. In. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:606–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0808697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha P, Kuruba N. Premature ovarian failure. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:16–19. doi: 10.1080/01443610601016685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis E, Kaufmann WE, Ono MY, Tartaglia N, Lachiewicz A, Kronk R, Delahunty C, Hessl D, Visootsak J, Picker J, Gane L, et al. Advances in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:378–390. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafique S, Sterling EW, Nelson LM. A new approach to primary ovarian insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2012;39:567–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberger MD1, Hagerman RJ, Sherman SL, McConkie-Rosell A, Welt CK, Rebar RW, Corrigan EC, Simpson JL, Nelson LM. The FMR1 premutation and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. ACOG committee opinion No. 469: carrier screening for fragile X syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1008–1010. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fae884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolin SL, Brown WT, Glicksman A, Houck GE, Jr, Gargano AD, Sullivan A, Biancalana V, Bröndum-Nielsen K, Hjalgrim H, Holinski-Feder E, Kooy F, Longshore J, et al. Expansion of the fragile X CGG repeat in females with premutation or intermediate alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:454–464. doi: 10.1086/367713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LM. What's the best approach to spontaneous premature ovarian failure? Contemporary Ob/Gyn. 2004:46–55. 1 Nov: [Google Scholar]

- Davis SR. Premature ovarian failure. Maturitas. 1996;23:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00966-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AR, Baker VL, Sterling EW, Ryan ME, Woodruff TK, Nelson LM. The time is now for a new approach to primary ovarian insufficiency. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1890–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EJ, Treff NR, Scott RT., Jr. Fertility after age 45: from natural conception to assisted reproductive technology and beyond. Maturitas. 2011;70:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]