Groucho-related corepressors in plants bind a peptide motif found in numerous repressors through a novel peptide recognition fold.

Keywords: Topless, TPR, TPD, NINJA, EAR, IAA, jasmonate, auxin, Groucho, TUP1, TLE

Abstract

TOPLESS (TPL) and TOPLESS-related (TPR) proteins comprise a conserved family of plant transcriptional corepressors that are related to Tup1, Groucho, and TLE (transducin-like enhancer of split) corepressors in yeast, insects, and mammals. In plants, TPL/TPR corepressors regulate development, stress responses, and hormone signaling through interaction with small ethylene response factor–associated amphiphilic repression (EAR) motifs found in diverse transcriptional repressors. How EAR motifs can interact with TPL/TPR proteins is unknown. We confirm the amino-terminal domain of the TPL family of corepressors, which we term TOPLESS domain (TPD), as the EAR motif–binding domain. To understand the structural basis of this interaction, we determined the crystal structures of the TPD of rice (Os) TPR2 in apo (apo protein) state and in complexes with the EAR motifs from Arabidopsis NINJA (novel interactor of JAZ), IAA1 (auxin-responsive protein 1), and IAA10, key transcriptional repressors involved in jasmonate and auxin signaling. The OsTPR2 TPD adopts a new fold of nine helices, followed by a zinc finger, which are arranged into a disc-like tetramer. The EAR motifs in the three different complexes adopt a similar extended conformation with the hydrophobic residues fitting into the same surface groove of each OsTPR2 monomer. Sequence alignments and structure-based mutagenesis indicate that this mode of corepressor binding is highly conserved in a large set of transcriptional repressors, thus providing a general mechanism for gene repression mediated by the TPL family of corepressors.

INTRODUCTION

Gene expression is regulated by gene-specific transcriptional activators and repressors that interact through peptide motifs with general coactivator and corepressor complexes. Although transcriptional repression is thought to be equally important as activation, comparatively little is known about how transcriptional repressors communicate with corepressors (1). In Arabidopsis thaliana (At), all known types of repressor motifs can interact with members of the TOPLESS (TPL) class of corepressors (2). TPL is related to Tup1 in fungi and Groucho/TLE (transducin-like enhancer of split) in animals, which are believed to function as transcriptional repressor–recruited scaffolds for the binding of chromatin-modifying complexes, histones, and the Mediator complex (3, 4). TPL, Tup1, Groucho, and TLE have analogous functions and interactions. They share a similar domain organization, in which N-terminal tetramerization domains are separated by Q- and P-rich spacers from C-terminal WD40 repeat β-propeller domains (Fig. 1A) (1, 5). How TPL proteins recognize repressor motifs found in diverse transcriptional factors is unknown.

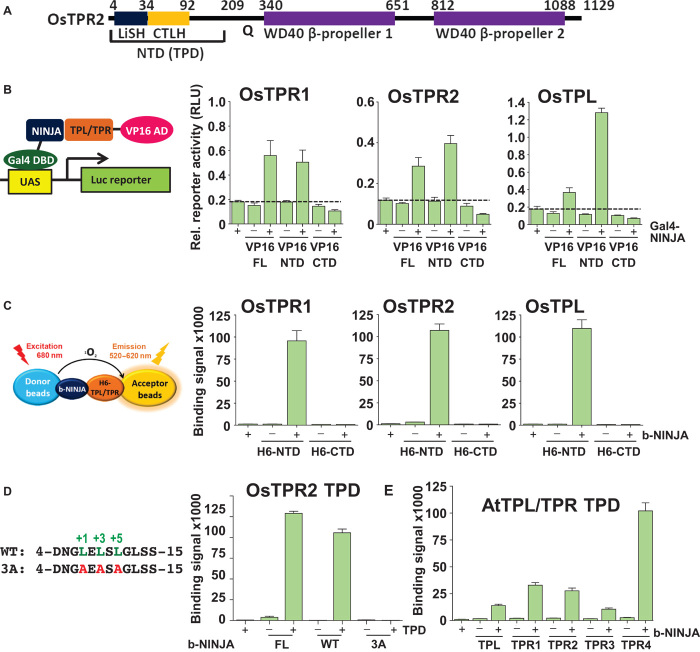

Fig. 1. The N terminus of TPL/TPR proteins binds the NINJA EAR motif.

(A) Schematic diagram of the domain structure of OsTPR2. In a search against the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database, we identified a seven-bladed β-propeller structure (PDB code: 3MXX) with a sequence identity of 26% to the first WD40 domain and 25% to the second WD40 domain of OsTPR2. Thus, the overall structure of the TPL/TPR C-terminal WD repeats can be modeled as two seven-bladed β-propeller domains. Q, P/G/T/Q-rich linker region. (B) Mammalian two-hybrid interaction between full length (FL), N-terminal domain (NTD; amino acids 1 to 209, 1 to 210, and 1 to 209), and CTDs {amino acids 211 [TPL(211–1133)] to 1133 [TPL(211–1133)]/210 to 1133 [TPR1(211–1133)]/210 to 1129 [TPR2(210 –1129)]} of rice TPL/TPR1/TPR2 proteins fused to VP16 transcriptional activation domain (VP16) and full-length NINJA fused to Gal4 DBD (Gal4-NINJA) (n = 3; error bars, SEM). UAS, upstream activating sequence; AD, activation domain; RLU, relative light units. (C) AlphaScreen luminescence proximity assay between the H6-NTD [same amino acids as in (A)] and H6-CTD (amino acids 323 to 1116/317 to 1113/316 to 1107) of rice TPL/TPR1/TPR2 proteins and biotinylated NINJA EAR motif peptide (b-NINJA) (n = 3; error bars, SD). (D) AlphaScreen interaction between the OsTPR2 N-terminal domain and biotinylated wild-type (WT) and mutant (3A) NINJA peptide or biotinylated MBP-tagged full-length NINJA protein. (E) AlphaScreen interaction between H6-tagged TPL/TPR N-terminal domains and b-NINJA.

The prototypic class of repressor motifs in plants are the ethylene response factor–associated amphiphilic repression (EAR) motifs (6, 7). Most EAR motifs belong to the LxLxL subclass, which is found in a large fraction of all transcription regulatory proteins (6), including those of at least eight of the major plant hormone signaling pathways [auxin (8), jasmonate (9, 10), abscisic acid (2, 10), brassinosteroids (11), strigolactones (12, 13), gibberellins (14), salicylic acid (15), and ethylene (15)] (fig. S1). An LxLxL EAR sequence consisting of only six amino acids (DLELRL) fused to the galactose 4 (Gal4) DNA binding domain (DBD) is sufficient to repress transcription in an Arabidopsis reporter gene assay (16). A yeast two-hybrid screen with the LxLxL motif–containing repressor of auxin signaling, IAA12 (auxin-responsive protein 12), as bait first identified TPL as repressor domain binding protein (17), and a high-throughput yeast two-hybrid screen with TPL as bait established TPL as a general corepressor that is recruited by numerous repressors, transcription factors (TFs), and transcriptional adaptor proteins (2).

TPL/TPR-interacting transcriptional repressors play a particularly prominent role in not only downstream signaling but also perception of several plant hormones, including auxins and jasmonates. Auxins and jasmonates function as “molecular glue” to induce an interaction between key transcriptional repressors and E3 ubiquitin ligases by formation of ternary repressor–hormone–E3 ligase complexes. This induced proximity results in the E3 ligase–catalyzed ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the repressor proteins to induce hormone target gene expression. For instance, auxin signaling is mediated by ubiquitination and proteolysis of Aux/IAA repressor proteins by auxin-mediated binding of TIR1 (transport inhibitor response 1) E3 ubiquitin ligases. In the absence of auxin, IAA repressors recruit TPL/TPR corepressors to ARF TFs to prevent expression of ARF target genes (18, 19). Similarly, jasmonate-isoleucine (JA-Ile) mediates an interaction between JAZ repressor proteins and COI1 (coronatine insensitive 1) E3 ubiquitin ligase (20, 21). In the absence of JA-Ile, JAZ repressors form complexes with helix-loop-helix TFs and the EAR motif–containing NINJA adaptor protein to indirectly recruit TPL/TPR to JAZ proteins to repress JA target gene expression (10, 20, 21). A subset of JAZ proteins also have EAR motifs and can directly interact with TPL/TPR proteins (2, 6, 9).

TPL proteins have a highly conserved N-terminal domain containing a lissencephaly homologous (LisH) dimerization motif and a C-terminal to LisH (CTLH) motif (17). The N-terminal domain of TPL can bind the IAA12 repressor, and this interaction is abrogated when the CTLH motif is deleted (17). Following the conserved N-terminal domain are a proline- and glutamine-rich linker and two C-terminal WD40 domains (Fig. 1A). Here, we report structural and biochemical studies of the interactions between TPL proteins and EAR motifs.

RESULTS

NINJA EAR binds the N-terminal domains of rice TPL/TPR proteins

To understand how TPL proteins interact with diverse transcriptional repressors, we first mapped the EAR motif–binding domain in all three members of the TPL corepressor family from rice (OsTPL, OsTPR1, and OsTPR2, also called ASP1, ASPR1, and ASPR2) (22). Using mammalian two-hybrid assays, we show that the full-length OsTPL/TPR proteins as well as their N-terminal domains directly bind the jasmonate-signaling NINJA protein from Arabidopsis (all proteins from rice will be labeled with Os in front of protein names and proteins from Arabidopsis with protein name only; Fig. 1B), consistent with the yeast two-hybrid interaction of TPL and TPL N-terminal domain with the repressor domain of IAA12 (17). In contrast, the C-terminal WD40 domains failed to interact with NINJA. To corroborate these results, we purified the conserved N-terminal and C-terminal domains (CTDs) of the three members of the rice TPL corepressor family. The N-terminal domains, in contrast to the CTDs, directly bound to a 12–amino acid NINJA LxLxL wild-type EAR motif peptide (Fig. 1, C and D), but not a mutant EAR motif in which the three conserved leucine residues were replaced with alanine. These results agree with the loss of EAR motif repressor activity upon replacement of the EAR leucine codons (8, 16) and the loss of TPL binding upon replacement of leucine residues in the IAA12 EAR motif (17). In addition, we also purified the N-terminal domains of all five Arabidopsis TPL/TPR proteins (TPL, TPR1, TPR2, TPR3, and TPR4) and demonstrated that each of them can interact with the NINJA EAR motif to variable degrees (Fig. 1E). Therefore, the TPL/TPR N-terminal domain and the EAR LxLxL motif are both required and sufficient for the interaction. Because the conserved N-terminal domain mediates EAR motif recognition, we termed this domain TOPLESS domain (TPD) to highlight its ability to interact with transcriptional repressors.

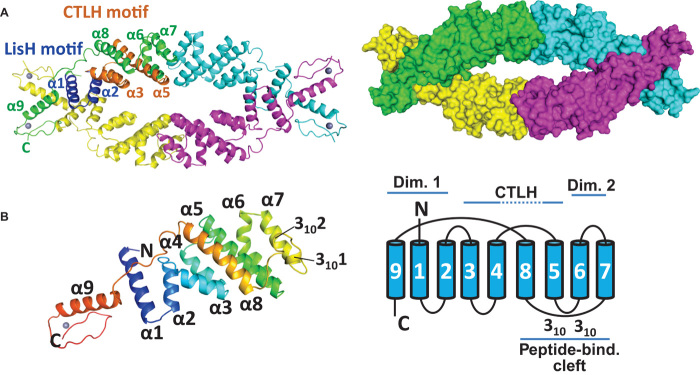

The OsTPR2 TPD forms an extended tetrameric structure

Extensive crystallization screening of the TPD of the five Arabidopsis and three rice TPL/TPR proteins allowed us to crystallize selenomethionine (SeMet)–substituted OsTPR2 TPD and to solve its structure at 2.5 Å by Se-SAD (single-wavelength anomalous diffraction) phasing. We also solved the structure of native OsTPR2 TPD by molecular replacement using the structure of the SeMet-substituted OsTPR2 TPD as search model at a resolution of 3.25 Å (Table 1). The TPD forms an extended, disc-like tetramer of ~160 Å in length with a large central cavity of ~60 × 15 Å that is lined by negatively charged residues (Fig. 2A and fig. S2). We confirmed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) that the tetramer seen in the crystal is the physiological oligomer for all rice and Arabidopsis TPL/TPR proteins (shown for the OsTPR2 TPD in fig. S3A). The TPD monomers form a fold composed of nine α helices (α1 to α9), two short 310 helices (3101 and 3102), and connecting loops (Fig. 2B). Helix 9 is followed by a long, flexible loop that is constrained by a zinc finger, in which two invariable C and H residues coordinate one Zn2+ ion (Fig. 2B), whose identity was confirmed by x-ray fluorescence (fig. S4).

Table 1. X-ray diffraction data and refinement statistics for TPR2 TPD structures.

| SeMet–TPR2 TPD | ApoTPR2 TPD | TPR2 TPD + NINJA complex | TPR2 TPD + IAA10 complex | TPR2 TPD + IAA1 complex | |

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P212121 | P42212 | P21 | P3121 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 70.2, 111.9, 145.0 | 59.0, 59.0, 171.7 | 81.7, 65.0, 107.7 | 162.7, 162.7, 157.3 | 58.4, 129.1, 79.1 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 105.4, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 110, 90 |

| Wavelength | 0.9787 (peak) | 1.278* | 1.078 | 1.078 | 0.9787 |

| Resolution | |||||

| All (Å) | 50–2.5 | 50–3.25 | 50–3.1 | 50–3.1 | 50–2.7 |

| Last shell (Å) | 2.64–2.5 | 3.43–3.25 | 3.31–3.1 | 3.27–3.1 | 2.85–2.7 |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.109 (1.0)† | 0.081 (1.26)† | 0.172 (0.566)† | 0.074 (0.93)† | 0.072 (0.678) |

| I/σI | 20.4 (3.2)† | 27.5 (3.5)† | 5.9 (2.2)† | 18.3 (2.0)† | 15.0 (2.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100)† | 100 (100)† | 99.9 (99.9)† | 99.9 (99.9)† | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 14.8 (15.0)† | 26.3 (28.2)† | 4.1 (4.2)† | 7.4 (7.6)† | 5.2 (4.3) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.5 | 50–3.25 | 50–3.1 | 50–3.1 | 50–2.7 |

| No. of reflections | 76,212 | 9,103 | 20,020 | 43,939 | 30,324 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.199/0.242 | 0.212/0.269 | 0.232/0.286 | 0.196/0.229 | 0.22/0.252 |

| No. of molecules per asymmetric unit | 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| No. of atoms | |||||

| Protein | 6,804 | 1,703 | 6,692 | 10,291 | 6,620 |

| Ligand/peptide | 0 | 1 | 188 | 344 | 241 |

| Water | 378 | 4 | 34 | 23 | 89 |

| B-factors | |||||

| Protein | 60.0 | 119.0 | 57.4 | 101.2 | 69.1 |

| Ligand/peptide | N.A. | 105.5 | 68.2 | 127.8 | 79.8 |

| Water | 54.1 | 54.1 | 41.5 | 88.3 | 63.3 |

| RMSDs | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.46 | 1.28 | 1.41 | 1.44 | 1.37 |

| Ramachandran | |||||

| Favored (%) | 98.1 | 98.0 | 98.9 | 98.4 | 99.0 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

*Native crystal data were collected at this wavelength to measure Zn anomalous signal.

†Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Fig. 2. The OsTPR2 TPD forms a novel tetrameric fold.

(A) The OsTPR2 TPD forms a tetramer. Left: Cartoon diagram of the tetrameric structure of OsTPR2 TPD with the LisH and CTLH motifs colored in blue and brown, respectively. The Zn2+ ions are shown as gray spheres. Right: Surface structure of the tetramer. (B) Structure of an OsTPR2 TPD monomer in rainbow color scheme from N terminus (N; blue) to C terminus (C; red). The secondary structure diagram of the OsTPR2 TPD fold is shown on the right.

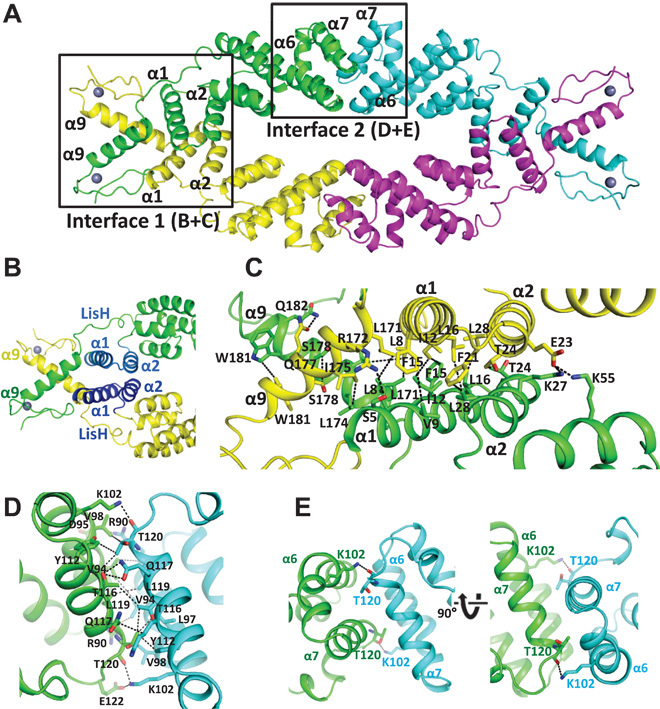

The tetramer is a dimer of dimers. The first dimerization interface is mediated by helices α1, α2, and α9 from each monomer. The N-terminal helices α1 and α2 comprise the LisH motif (23), an antiparallel four-helix bundle, that is extended by additional interactions between the C-terminal α9 helices in OsTPR2 (Figs. 2A and 3, A to C). The second interface is formed by a new dimerization motif, in which the antiparallel helices α6 and α7 from each monomer pack perpendicularly against helices α6 and α7 from the neighboring monomer (Figs. 2A and 3, D and E). The CTLH motif, implicated in EAR motif interaction (17), consists of helices α3 to α5 and forms the core of each monomer sandwiched between the two dimerization motifs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3. The OsTPR2 TPD tetramer has two distinct dimerization interfaces.

(A) View of the TPR2 TPD tetramer with boxed interfaces 1 and 2. (B) Overview of the dimerization domain 1. Dimerization interface 1 is formed by the N-terminal four-helix bundle of the LisH domain and the C-terminal helix α9. The two helices from each monomer forming the LisH domain are shown in blue. (C) A close-up view of the interface with key interacting residues shown as stick model and interactions as dashed lines. (D) Interface 2 with key interacting residues shown as stick model and interactions as dashed lines. (E) The interaction between α6 K102 from one monomer and α7 T120 from the other monomer induces a kink in α6 for antiparallel α6-α7 packing. This fold represents a novel dimerization motif. A structure homology search revealed an artificial, rationally designed homodimerization motif (PDB: 3V1F) as closest structure homolog in the PDB.

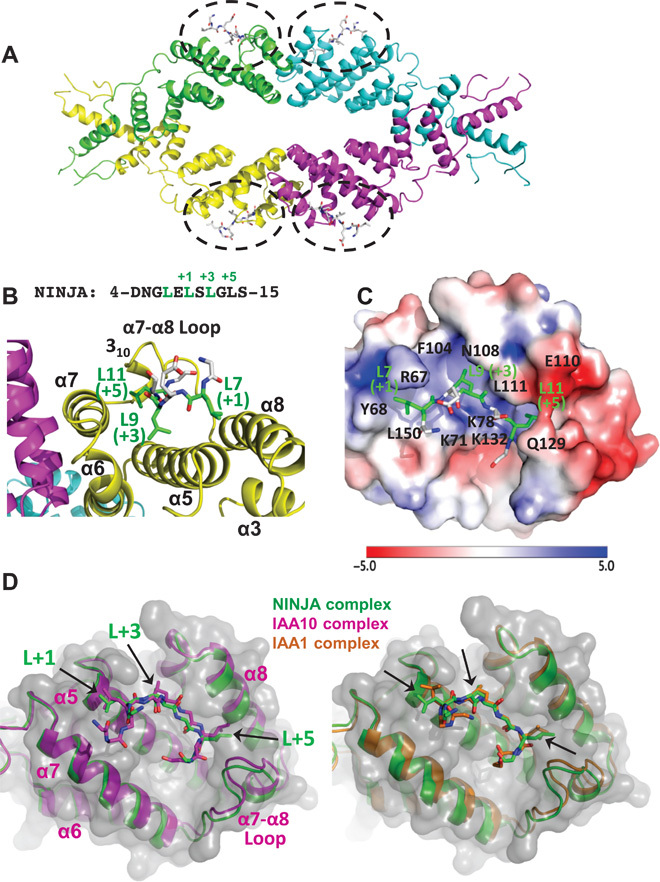

NINJA EAR binds a shallow groove in each of the four monomers of a TPD complex

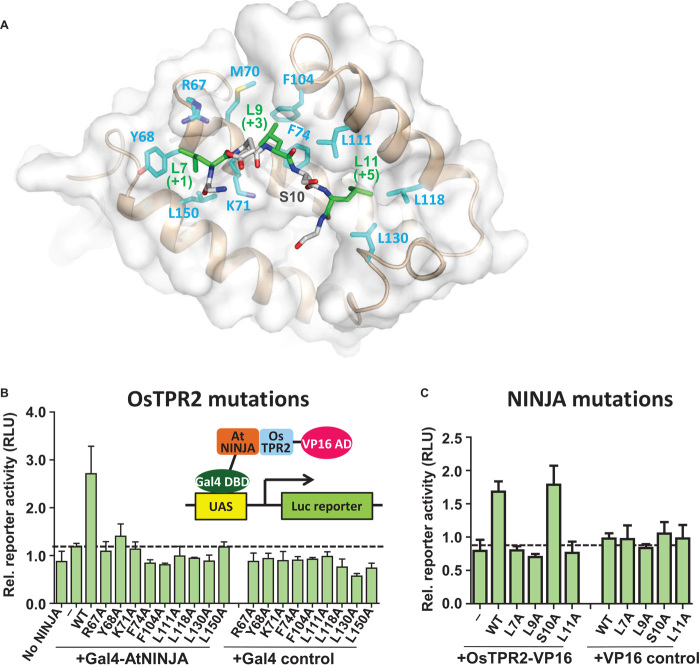

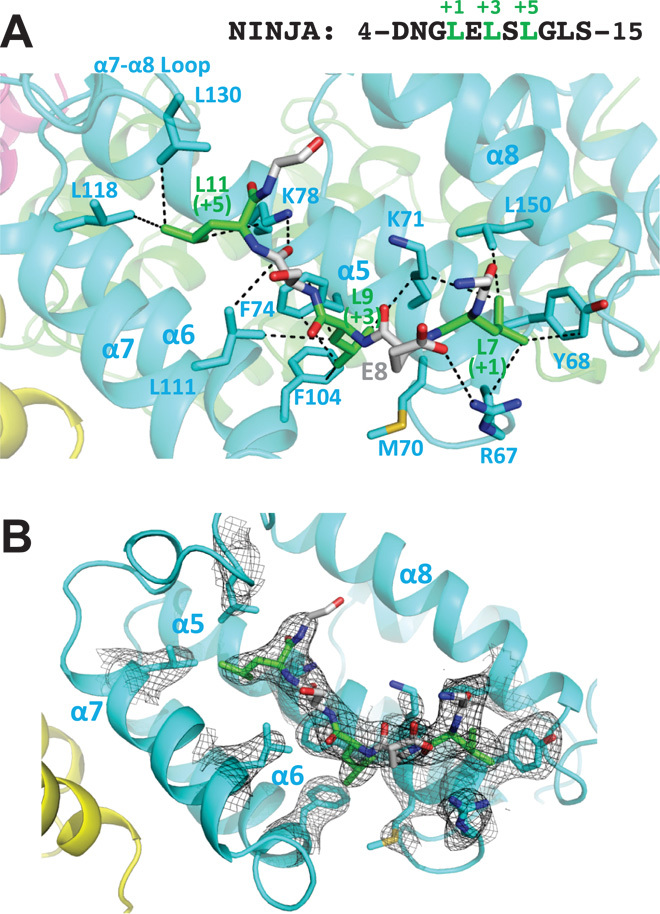

To understand the atomic detail of the interaction between TPL TPDs and LxLxL EAR motifs, we crystallized OsTPR2 TPD in complex with the NINJA EAR motif and determined the complex structure by molecular replacement at a resolution of 3.1 Å. The structure of the EAR-bound TPD is very similar to that of the apo protein (apo) TPD [overall root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.0 Å], with differences mostly in loop regions following α9 (fig. S5). Each EAR motif peptide binds to a groove lined by hydrophobic and positively charged residues contained within each OsTPR2 TPD monomer; thus, four NINJA EAR motif peptides are bound by one OsTPR2 tetramer (Fig. 4A). The groove is formed by helices α5 from the CTHL motif (cleft bottom), α6 and α7 from the second dimerization domain (left cleft side), α8 (right cleft side), and the α7-α8 loop with the 310 helices (back side of the cleft) (Fig. 4B). The three conserved leucine residues (L7, L9, and L11 at the +1, +3, and +5 positions) from the peptide are inserted into largely hydrophobic pockets of the OsTPR2 TPD cleft, which is formed by hydrophobic and positively charged cleft residues (L7: Y68, K71, R67, and L150; L9: M70, K71, F74, F104, and L111; L11 deep inside of the cleft: K78, L118, and L130) (Figs. 4C and 5). In addition to hydrophobic interactions, EAR E8 also makes an ionic interaction with TPD R67 in at least one of the four complexes. Sequence alignment showed that these residues are invariant in TPL and TPR proteins from rice and Arabidopsis (fig. S6).

Fig. 4. Four EAR motif peptides bind the hydrophobic surface grooves of one OsTPR2 TPD tetramer.

(A) Tetrameric structure of OsTPR2 TPD complexed with NINJA EAR motif peptides. The peptide binding sites are indicated by black dashed circles with peptides shown in stick representations. (B and C) Close-up views of a NINJA EAR motif (stick presentation) bound to the OsTPR2 TPD peptide-binding groove shown as cartoon presentation (B) or as charge potential surface (C) (blue, positive charge potential; red, negative charge potential). A color code bar (bottom) shows the electrostatic scale from –5 to +5 eV. (D) Structure overlays of the EAR motifs from NINJA, IAA1, and IAA10 in the OsTPR2 TPD surface pocket.

Fig. 5. Structure of OsTPR2 TPD in complex with NINJA EAR peptide.

(A) Close-up view with charge interaction, hydrogen bond, and hydrophobic interactions shown as black dashed lines. The NINJA peptide sequence is shown above the graph. The residue carbon atoms in the OsTPR2 TPD hydrophobic binding cleft are labeled in cyan, whereas the residue carbon atoms of the EAR motif are labeled in green for the three conserved leucine residues and gray for the rest of residues. (B) 2Fo − Fc electron density map contoured at 1σ of residues at the OsTPR2 TPD–NINJA EAR motif interaction interface.

IAA1 and IAA10 EAR-TPD complex structures reveal a conserved EAR binding mode

To test whether the EAR binding mode is conserved, we also determined the structures of OsTPR2 TPD in complex with EAR motifs from the auxin-signaling repressors IAA10 (fig. S7) and IAA1 (fig. S8) at resolutions of 3.1 and 2.7 Å, respectively (Table 1). Although there are small variations in the binding modes, the IAA1 and IAA10 peptides bind to the same grooves as the NINJA peptide (Fig. 4D). The TPD conformations and overall binding modes are very similar in the three complex structures (fig. S9). Therefore, we conclude that LxLxL-type EAR motifs share a common mode of interaction with the TPD that is mediated by key hydrophobic interactions between the three conserved leucine residues of EAR and highly conserved hydrophobic and positively charged cleft residues of TPD. In addition, the flanking residues of EAR motifs, especially the ones at the +2 position, also contribute to binding by forming hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with the OsTPR2 TPD (Fig. 5A).

We validated the observed interactions seen in the complex structure by mammalian two-hybrid assays in the context of full-length OsTPR2 and NINJA (Fig. 6). Whereas wild-type OsTPR2 and NINJA activated the luciferase reporter about twofold above background, single mutation of each of the key binding cleft residues (R67A, Y68A, K71A, F74A, F104A, L111A, L118A, L130A, and L150A) abolished the reporter gene activation (Fig. 6B). Conversely, when we examined the effect of NINJA EAR motif mutations in the context of full-length OsTPR2 and NINJA, the mutation of each of the three conserved leucine residues (L7A, L9A, and L11A) of the LxLxL motif abolished activation of the luciferase reporter (Fig. 6C), in agreement with the requirement of all three leucine residues of IAA17, ERF4, and SUPERMAN EAR motifs for repression in reporter gene assays (8, 16). This effect was specific, because mutation of S10, which is not conserved in the LxLxL motif, did not affect luciferase reporter activity. Therefore, these mutational data support that the interactions observed in the complex structure are also critical for the interaction between the full-length proteins.

Fig. 6. Mutations of OsTPR2 TPD–NINJA EAR motif interface residues abolish interaction between full-length OsTPR2 and NINJA in a mammalian two-hybrid assay.

(A) Stick presentation of NINJA and OsTPR2 interaction residues. The binding groove is shown as transparent surface. (B) Mutations of key residues of the OsTPR2 TPD hydrophobic cleft disrupt the interaction between full-length OsTPR2 and NINJA. (C) Effect of mutations of NINJA EAR motif residues on the OsTPR2-NINJA interaction.

TPL has important functions in axis establishment during embryonic development. A unique temperature-sensitive mutation in Arabidopsis, tpl-1 (N176H), transforms the shoot at elevated temperatures into a second root to give rise to double-root (hence “topless”) seedlings (24). Whereas tpl loss-of-function mutations show no obvious phenotype because of the functional redundancy between TPL and TPR proteins, tpl-1 is a dominant-negative, gain-of-function mutation with unknown molecular basis (24). N176 is located on helix 9 and faces away from the protein into solvent (fig. S10A). Consistent with the ability of cellular mutant tpl-1 protein to still both self-associate and associate with IAA repressors (17), the OsTPR2 TPD structure indicates that N176 does not contribute to the function of either of the two dimerization domains nor to EAR binding, Zn binding, or the integrity of the fold. However, most N176H OsTPR2 TPD mutant protein formed aggregates when expressed as recombinant protein, and most of the remaining protein eluted as higher-order oligomers or aggregates during SEC (fig. S10B). This suggests that N176H mediates or stabilizes intertetramer interactions that may lead to the formation of mixed TPL/TPR aggregates.

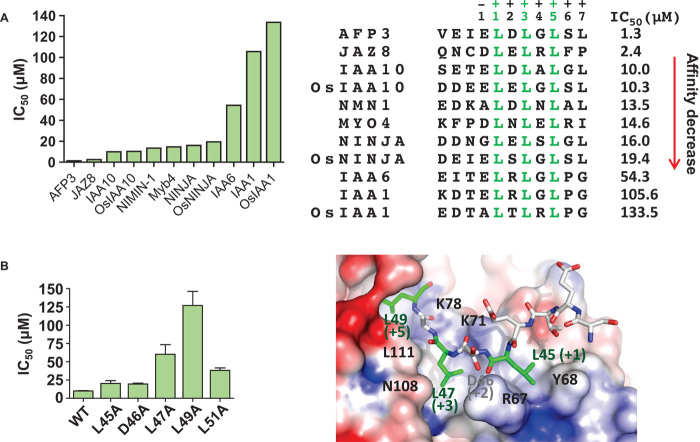

EAR sequence variations and repressor oligomeric states modulate TPD binding affinity

Given that a very large number of TFs, repressors, and adapters contain LxLxL-type EAR motifs (2), it has been important to establish whether the motifs found in endogenous proteins differ in their TPL binding affinities and to examine potential affinity determinants. We used an AlphaScreen competition assay to compare the ability of different Arabidopsis and rice EAR motif peptides to compete the binding between the NINJA EAR motif and OsTPR2 TPD. As seen in fig. S11 and summarized in Fig. 7A, median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values differed by ~100-fold. This implies that although the three conserved L residues are important for binding, the largely charged flanking residues are also important contributors to the total binding energy.

Fig. 7. EAR motifs differentially interact with OsTPR2 TPD.

(A) Relative OsTPR2 affinities of different EAR motifs. Affinities were determined by AlphaScreen competition curves (fig. S11) under conditions where the IC50 values approximate the dissociation constants (Kd) of the interactions. (B) Mutations of IAA10 EAR motif residues reduce interaction between EAR peptides and OsTPR2 TPD. Relative affinities were determined by AlphaScreen competition curves (fig. S12) under conditions where the IC50 values approximate the Kds of the interactions.

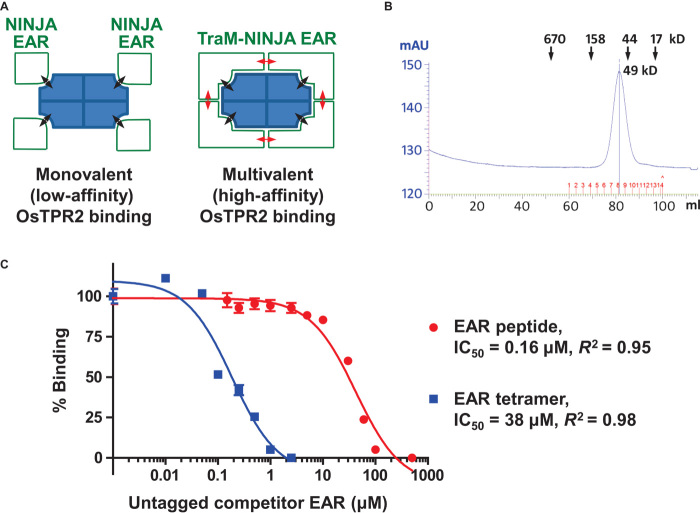

Many repressors, including JAZ (25, 26) and IAA (27) repressors, are dimeric/oligomeric and/or contain more than one EAR motif (7), suggesting that in addition to flanking sequences, higher binding affinities (avidities) could also be achieved by multivalent interaction stabilization of EAR motifs from one protein/oligomer to two or more binding sites of a TPD tetramer (see Fig. 8A for a model). To explore this possibility, we fused a 12–amino acid peptide (DNGLELSLGLSC) of the monomeric NINJA EAR motif to a small tetrameric protein, the bacterial F conjugation regulatory protein TraM [PDB: 2G7O (28)]. Whereas in an AlphaScreen competition assay the monomeric NINJA EAR interacts with OsTPR2 TPD with an IC50 of 38 μM, the tetrameric NINJA EAR fusion protein had a greater than 200-fold increased TPD avidity (IC50 of 0.16 μM), indicating that multivalent interactions between oligomeric repressors and the tetrameric TPD can indeed markedly stabilize complex formation (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Repressor oligomerization can greatly increase TPD affinity.

(A) Cartoon presentation of the interaction between tetrameric OsTPR2 TPD and either a monomeric 12–amino acid version of NINJA EAR (NINJA: DNGLELSLGLSC) or tetrameric TraM-NINJA EAR. Weak EAR-TPD interactions (black double-sided arrows) are greatly stabilized by simultaneous TraM EAR–TraM EAR (red arrows) interactions, resulting in a much more than additive increase in OsTPD binding affinity. (B) TraM-NINJA EAR forms a tetramer in solution. SEC elution profile with elution volumes of size standards indicated. Each monomer has a size of 10.9 kD. mAU, milliabsorbance units. (C) Homologous AlphaScreen competition curves of the interactions between H6-OsTPR2 TPD and either biotin-TraM-NINJA EAR (blue squares) or biotin-NINJA EAR peptide (red circles).

To systematically examine the contribution of EAR motif residues to OsTPR2 binding, we synthesized a set of IAA10 peptides in which the four leucine residues and the aspartate residue in the +2 position were individually replaced with alanine. Then, we tested the effect of the substitutions on the relative affinity of the EAR–OsTPR2 TPD interaction by AlphaScreen competition assay (Fig. 7B and fig. S12). Mutations of the first and second residues (L45A and D46A at the cleft surface) caused modest reduction in binding affinity, whereas mutations of the third and fifth residues (L47A and L49A), which stick deeply into the cleft (fig. S7B), caused strong reductions in binding affinity. The data are also consistent with a previous report that the second and third conserved leucine residues of an EAR motif are most important in TPL/TPR binding (16). Mutation of the seventh residue (L51A) caused moderate reduction in binding affinity. This fourth L residue is only present in a subset of EAR motifs (fig. S1) and may provide additional binding strength, particularly in motifs like the one from IAA10, in which the first conserved L does not insert deeply into the cleft.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have confirmed the conserved TPD of the TPL/TPR family as the repressor binding domain and determined its tetrameric structure both in the apo state and in complex with the EAR motif peptides from three different repressors. Together with the extensive mutagenesis and biochemical data, these structures define the molecular basis of how the TPL family of corepressors interacts with and is recruited by diverse repressors to regulate a wide spectrum of plant physiology, including the transcriptional programs of many plant hormone signaling pathways.

Whereas the TPD has been the only TPL/TPR domain identified to interact with repressor domains, animal TLE/Groucho proteins interact with a subset of repressor domains through their N-terminal tetramerization domains [for example, (29–32)] and with a separate subset through their C-terminal WD40 domain [for example, (33–37)]. Similarly, both the yeast Tup1 N-terminal tetramerization domain, via the Ssn6 adaptor protein (38), and C-terminal WD40 repeat domain (39) interact with transcriptional repressors. Whereas the WD40 domains of TLE, Tup1, and TPL are weakly conserved, the N-terminal tetramerization domains are not homologous and, in TLE and Tup1, form coiled-coil dimers of dimers (40, 41). However, these domains resemble the TPR2 TPD in their overall dimensions and two sites of strong negative charge potential flanking the tetramer center. The structural basis of the interaction of the N-terminal TLE and Tup1 domains with repressor motifs remains unknown.

TPL/TPR proteins are especially at the heart of many plant hormone signaling pathways. Hormones such as auxins, jasmonates, and strigolactones function by promoting the binding of TPL/TPR-interacting repressors to their respective E3 ligase receptors and mediating degradation of the repressors to relieve repression of target gene expression. The common TPL/TPR binding mode of transcriptional regulatory proteins from multiple hormone signaling pathways, here shown for IAA1, IAA10, and NINJA, raises the intriguing possibility that TPL/TPR competition may contribute to the extensive hormone signaling crosstalk.

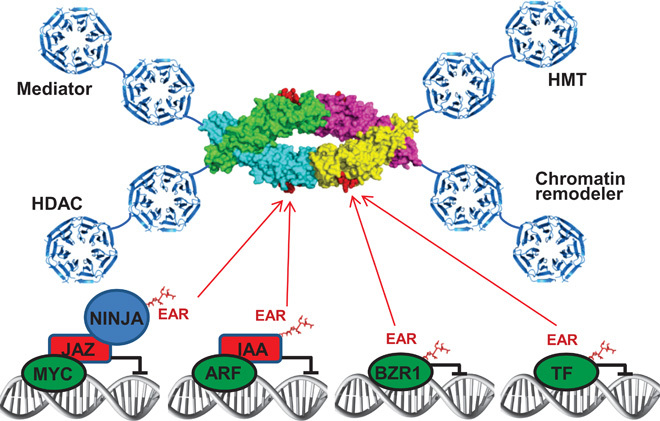

TPL/TPR are thought to exert their repressive function through recruitment of histone deacetylases (24, 42, 43) and chromatin remodelers with associated histone methyltransferases (2, 44, 45), and, in analogy to TLE/Tup1 proteins, possibly also by interaction with histones and the Mediator complex (4, 46, 47). Thus, TPL/TPR recruitment via the TPD may provide large, extended scaffolds containing eight seven-bladed β-propeller domains to mediate multiple direct and/or indirect interactions with chromatin-modifying complexes and components of the transcription preinitiation complex to mediate repression in a large number of signaling pathways (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Model of the recruitment of TPL/TPR corepressors by EAR motifs.

The EAR motifs shown are from adaptor proteins (NINJA, jasmonate signaling), repressors (IAA proteins, auxin signaling), and TFs [BZR1 (brassinazole resistant 1), brassinosteroid signaling]. The OsTPR2 TPD is shown as a space-filling structure based on this study, whereas the WD40 seven-bladed β-propeller domains are depicted as ribbon models based on the structure of the yeast Tup1 C terminus (PDB code: 1ERJ). TFs are shown in green, repressors in red, and the adaptor protein NINJA in blue. This model does not imply that EAR repressors from different signaling pathways can bind together on a single TPL tetramer but rather that different types of EAR-containing transcriptional proteins share the same TPL/TPR binding mode and may compete for TPL/TPR binding in vivo. HMT, histone methyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase.

Whereas a single NINJA EAR peptide only weakly binds OsTPR2 (Fig. 7A), fusion of the NINJA EAR motif to a tetrameric bacterial protein markedly increases OsTPR2 binding avidity (Fig. 8C). This suggests that repressor oligomerization may be an important affinity determinant for TPL/TPR binding. In support of these binding studies with purified proteins, both auxin-signaling ARF TFs and IAA repressors contain PB1 oligomerization domains (48, 49) that can form higher-order head-to-tail homo-oligomers (IAA-IAA and ARF-ARF) and hetero-oligomers (IAA-ARF). IAA heterodimerization through engineered PB1 domains is insufficient to efficiently repress auxin responses in plants, suggesting a requirement for IAA multimerization (50). Similarly, TLE/Groucho oligomerization is required for efficient repression in vivo (51). Members of the Tup1/Groucho family of corepressors are found in all eukaryotes and are of paramount importance in numerous signaling pathways across species. Thus, the synergistic binding of the EAR repressor motifs to the tetrameric form of the TPD may provide a general paradigm for the recruitment of the TPL/Tup1/Groucho family of corepressors by diverse transcriptional repressors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs and reagents

The Arabidopsis NINJA complementary DNA (cDNA) was a gift from S. Y. He (Michigan State University). The codon-optimized cDNAs encoding rice TPL(1–209), TPR1(1–209), and TPR2(1–210) and Arabidopsis TPL(1–209), TPR1(1–209), TPR2(1–209), TPR3(1–209), and TPR4(1–209) were synthesized by Genewiz and cloned into the pSumo expression vector (LifeSensors) with a His6Sumo tandem fusion tag, followed by a ULP1 (ubiquitin-like protease type 1) protease cleavage site at the N terminus. For mammalian two-hybrid assay, the full-length NINJA cDNA was cloned in fusion with an N-terminal Gal4 DBD, and the full-length and truncated OsTPL, OsTPR1, and OsTPR2 cDNAs were cloned in fusion with an N-terminal VP16 activation domain. To prepare a tetramer protein with or without NINJA peptide, TraM (PDB code: 2G7O) cDNA (a known tetrameric structure) with or without NINJA EAR peptide cDNA fusion was cloned into the pETDuet1 vector (Novagen) in fusion with an N-terminal hexahistidine (H6)–tagged maltose-binding protein (MBP) tandem tag, followed by a thrombin cleavage site. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChange method (Stratagene). All plasmid DNA constructs and mutations were confirmed by sequencing. All synthesized peptides were purchased from Peptide 2.0 Inc.

Protein expression and purification

The His6Sumo-tagged TPL and TPR TPD expression vectors were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells, and transformants were grown in 4 liters of LB medium. Protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 16°C overnight after cell density reached an OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of ~1.0. Cells were harvested, resuspended in buffer A [20 mM tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol], and lysed with an APV2000 cell homogenizer (SPX Corporation). The lysate was centrifuged for 30 min at 20,000g, and the supernatant was loaded on a 50-ml Ni-chelating HP Sepharose column (GE Healthcare). The His6Sumo-TPD fusion protein was eluted using step elution in buffer A plus 250 mM imidazole and cleaved overnight with ULP1 protease at a protease/protein ratio of 1:500 while dialyzing against buffer A at 4°C overnight. The cleaved His6Sumo tag was removed by passing through a 5-ml Ni-chelating HP Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), and the protein in the flow-through was further purified by gel filtration chromatography through a 300-ml HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). The protein eluted from the gel filtration column at a volume corresponding to the size of a tetramer at a purity >95% as judged by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (fig. S3A). To prepare biotinylated MBP-NINJA protein, the NINJA cDNA was cloned into the first cloning site of a pETDuet1 vector (Novagen) with an AviTag and MBP tag at the N terminus. The AviTag is a biotinylation recognition motif for the E. coli biotin ligase BirA, which biotinylates the motif at a single lysine residue in cells (52). The second cloning site included the coding sequence of the biotinylation enzyme BirA. BL21 (DE3) transformants were grown in the presence of 40 μM biotin to allow in vivo biotinylation of MBP-NINJA protein. The fusion protein was purified by affinity chromatography through an MBPTrap HP amylose affinity column (GE Healthcare) using buffer A plus 10 mM maltose as the elution buffer, followed by SEC through a 120-ml HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) as described (53). His6MBP-TraM and His6MBP-TraM-NINJA proteins were similarly expressed as His6Sumo-TPD proteins and purified by amylose affinity column using an elution buffer of buffer A plus 10 mM maltose, followed by thrombin digestion at a protease/protein ratio of 1:500 at 4°C overnight while dialyzing against buffer A. The cleaved His6MBP tag was removed by passing through a 5-ml Ni-chelating HP column, and the TraM and TraM-NINJA proteins were further purified using the 120-ml HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 gel filtration column. For analytical SEC (fig. S10B), wild-type and N176H His6Sumo-OsTPR2 TPD Ni-column eluates from above were directly loaded onto the 120-ml HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column without previous tag removal to maximize protein solubility.

The CTD of OsTPL (residues 323 to 1116), OsTPR1 (residues 317 to 1113), and OsTPR2 (residues 316 to 1107) were cloned in fusion with a His8MBP tag at the N terminus into the insect expression vector pFastBac (Life Technologies). High-titer recombinant baculovirus was obtained using the Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System (Life Technologies). Recombinant P0 baculovirus stocks were generated by transfecting 5 μg of recombinant bacmid containing the target gene using 1.5 μl of FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Roche) and 100 μl of Transfection Medium (Expression Systems) into Sf9 cells in suspension culture for 4 days with shaking at 28°C. P0 viral stocks were used to produce high-titer P1 baculovirus stocks. For protein expression, Sf9 cells at a density of 2 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells/ml were infected with P1 virus at a multiplicity of infection of 5. Cells were harvested 2 days after infection and stored at −80°C until use. Insect cell membranes were disrupted by thawing frozen cell pellets in a hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), followed by Dounce homogenization. After ultracentrifugation at 125,000g, the supernatant was adjusted to a NaCl concentration of 150 mM and incubated with amylose resin overnight. The resin was washed with 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol, and the protein was eluted with 50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM maltose, and 10% glycerol (pH 7.5).

Crystallization

Purified rice and Arabidopsis TPL/TPR TPD proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration to about 10 mg/ml (determined by the Bradford assay) before crystallization trials. Initial screening identified that polyethylene glycol (PEG) is favorable for crystal formation. Optimization trays using PEG were manually set up using the sitting-drop method at 20°C. Many different conditions produced protein crystals. However, most of the polygon-shaped crystals only diffracted x-ray to 6 to 8 Å, whereas the rod-shaped OsTPR2 TPD crystals diffracted to high resolution. The SeMet-substituted OsTPR2 TPD apo crystals were grown using 0.5 μl of the purified protein and 0.5 μl of well solution [25% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.2 M magnesium chloride, 0.1 M bis-tris (pH 6.5), and 19.6 mM 5% methyl-6-O-(N-heptylcarbamoyl)-α-d-glucopyranoside]. Rod-shaped crystals with a size of 100 to 200 μm in length were obtained, and these crystals diffracted x-rays to ~2.5 Å at Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT) of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) synchrotron. To prepare the OsTPR2 TPD and peptide complexes, OsTPR2 TPD was mixed with different EAR motif peptides at a molar ratio of 1:2 before setting up crystallization trials. OsTPR2 TPD and NINJA complex crystals were grown using a well solution of 25% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M bis-tris (pH 5.5), and 3.0% w/v D-(+)-glucose monohydrate. OsTPR2 TPD and IAA10 complex crystals were grown using a well solution of 20% (w/v) PEG 3350 and 0.2 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate. OsTPR2 TPD and IAA1 complex crystals were grown using a well solution of 25% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.2 M NaCl, and 0.1 M bis-tris (pH 5.5).

Data collection and structure determination

All crystals were transferred to the well solution with 22% (v/v) ethylene glycol as cryoprotectant before flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. Data collections were performed at sector 21-ID (LS-CAT) beamlines of the APS synchrotron. To solve the phase problem, a single data set of a SeMet-substituted OsTPR2 TPD crystal was collected at a wavelength of 0.9798 Å (peak wavelength) to measure the Se anomalous signal. The diffraction data for all complex crystals were collected at slightly different wavelengths as indicated, similar to collecting a native data set (Table 1). All the data sets were processed using XDS (54), combined using Pointless, and merged using Scala of the CCP4 suite (55). Initial phases were established by Se-SAD phasing using the Phenix AutoSol program. A total of 12 Se atoms were found with a score of 0.44, and a fourfold noncrystallographic symmetry was also identified. Subsequently, a crude model was automatically built with R/Rfree of 0.32/0.36. The model was further improved by using the Phenix autobuild program (56) and by several cycles of manual building using Coot (57) and refinements using the Refmac program of CCP4 (58) and Phenix refine program to an R factor of 0.20 and an Rfree factor of 0.24 (Table 1). The OsTPR2 TPD + NINJA peptide, OsTPR2 TPD + IAA10 peptide, and OsTPR2 TPD + IAA1 peptide complex structures were solved by molecular replacement using the apo OsTPR2 TPD structure as a search model. The initial model was refined using Refmac and Phenix refine programs (59), and the model for the peptide was built on the basis of the difference electron density map using Coot. Several cycles of manual model building and refinements were performed to refine the complex structures to reasonable R factor and Rfree values (Table 1). To confirm the presence of zinc ions in the native OsTPR2 TPD crystals, an x-ray fluorescence scan for Zn, K-edge was performed (fig. S4A), and a full data set was collected at a wavelength of 1.278 Å to measure the zinc anomalous signal (fig. S4B). All the structure figures were prepared using the program PyMOL (60).

AlphaScreen binding assay

Interactions between His6-tagged TPL TPD, TPR1 TPD, or TPR2 TPD and biotinylated NINJA protein or EAR motif–containing peptides were assessed by luminescence-based AlphaScreen technology (PerkinElmer) using a hexahistidine detection kit that our group has extensively used (61). Unless otherwise noted, 50 nM biotinylated protein or peptides were attached to streptavidin-coated donor beads, and 50 nM His6-tagged TPD proteins were attached to nickel-chelated acceptor beads. Donor beads contain a photosensitizer that, upon activation at 680 nm, converts ambient oxygen into singlet oxygen. When the acceptor beads are brought into close proximity of the donor beads by TPD-EAR interaction, energy is transferred from singlet oxygen to thioxene derivatives in the acceptor beads, resulting in light emission at 520 to 620 nm. The binding mixtures, containing the indicated amounts of tagged protein and protein/peptide and streptavidin-coated donor beads (5 μg/ml) and Ni-chelate–coated acceptor beads, were incubated in 50 mM Mops (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, and bovine serum albumin (0.1 mg/ml) for 2 to 3 hours before data collection using an EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer). For competition assays, increasing concentrations of untagged peptides were added in addition to the tagged protein and protein/peptide. The IC50 values were derived from curve fitting on the basis of a competitive inhibitor model with GraphPad Prism, using conditions where the concentrations of tagged binding partners were below Kd.

Mammalian two-hybrid assay

To construct the Gal4 DBD-NINJA plasmid, the Arabidopsis NINJA full-length coding sequence was polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified, digested, and ligated into the Gal4 plasmid pM (Clontech). To generate VP16 fusion constructs, full-length and truncated coding sequences of rice TPR2, TPR1, and TPL were PCR-amplified from pLexA-N fusion plasmids (13), digested, and inserted into the pVP16 plasmid (Clontech). The reporter plasmid pG5-Luc contains a luciferase gene under the control of a Gal4 upstream activating sequence element. Gal4 fusion constructs (30 ng) were cotransfected with VP16 fusion constructs (30 ng), together with 100 ng of pG5-Luc and 1 to 3 ng of phRG-TK/Renilla (Promega), into AD293 cells in 24-well plates by Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) method according to the manufacturer’s manual. Cells were harvested 17 hours after transfection with 1× Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). Luciferase/Renilla activities were measured with the Dual-Luciferase Kit (Promega), and data were plotted as firefly luciferase activity relative to Renilla luciferase activity.

Acknowledgments

Use of APS was supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We thank the staff members at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility beamline BL17U for assistance in initial crystal screening and data collection. We also thank S. Grant for administrative support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Funding: This work was supported by the Van Andel Research Institute (H.E.X. and K.M.); Ministry of Science and Technology (People’s Republic of China) grants 2012ZX09301001, 2012CB910403, 2013CB910600, XDB08020303, 2013ZX09507001, and NSF 91217311 (H.E.X.); and NIH grants DK071662 (H.E.X.) and GM102545 and GM104212 (K.M.). We thank staff members of LS-CAT of APS for assistance in data collection at the beamlines of sector 21, which is in part funded by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (grant 085P1000817). Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/6/e1500107/DC1

Fig. S1. Sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of different transcriptional repressors, TFs, and adapters that interact with TPL/TPR.

Fig. S2. Charge distribution surface views of the complex between OsTPR2 TPD and the NINJA EAR motif.

Fig. S3. Biochemical and stuctural characterization of the TPR2 TPD tetramer.

Fig. S4. The rOsTPR2 protein contains a zinc finger structure.

Fig. S5. Structural overlay of OsTPR2 TPD apo and NINJA peptide–bound structures.

Fig. S6. Sequence alignment of the TPD of TPL and TPR proteins from rice (Os) and Arabidopsis (At).

Fig. S7. Structure of OsTPR2 TPD in complex with IAA10 EAR peptide.

Fig. S8. Structure of OsTPR2 TPD in complex with IAA1 EAR peptide.

Fig. S9. Structural comparison of NINJA, IAA10, and IAA1 peptide–bound OsTPR2 TPD structures.

Fig. S10. OsTPR2 TPD N176H forms higher-order oligomers.

Fig. S11. Relative TPD affinities of different EAR motifs.

Fig. S12. Effects of EAR point mutations on TPD binding.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Krogan N. T., Long J. A., Why so repressed? Turning off transcription during plant growth and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 628–636 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Causier B., Ashworth M., Guo W., Davies B., The TOPLESS interactome: A framework for gene repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158, 423–438 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buscarlet M., Stifani S., The ’Marx’ of Groucho on development and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 353–361 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malavé T. M., Dent S. Y., Transcriptional repression by Tup1–Ssn6. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84, 437–443 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z., Karmarkar V., Groucho/Tup1 family co-repressors in plant development. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 137–144 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kagale S., Links M. G., Rozwadowski K., Genome-wide analysis of ethylene-responsive element binding factor-associated amphiphilic repression motif-containing transcriptional regulators in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152, 1109–1134 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagale S., Rozwadowski K., EAR motif-mediated transcriptional repression in plants: An underlying mechanism for epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Epigenetics 6, 141–146 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiwari S. B., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. J., Aux/IAA proteins contain a potent transcriptional repression domain. Plant Cell 16, 533–543 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shyu C., Figueroa P., Depew C. L., Cooke T. F., Sheard L. B., Moreno J. E., Katsir L., Zheng N., Browse J., Howe G. A., JAZ8 lacks a canonical degron and has an EAR motif that mediates transcriptional repression of jasmonate responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 536–550 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauwels L., Barbero G. F., Geerinck J., Tilleman S., Grunewald W., Pérez A. C., Chico J. M., Bossche R. V., Sewell J., Gil E., García-Casado G., Witters E., Inzé D., Long J. A., De Jaeger G., Solano R., Goossens A., NINJA connects the co-repressor TOPLESS to jasmonate signalling. Nature 464, 788–791 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh E., Zhu J. Y., Ryu H., Hwang I., Wang Z. Y., TOPLESS mediates brassinosteroid-induced transcriptional repression through interaction with BZR1. Nat. Commun. 5, 4140 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou F., Lin Q., Zhu L., Ren Y., Zhou K., Shabek N., Wu F., Mao H., Dong W., Gan L., Ma W., Gao H., Chen J., Yang C., Wang D., Tan J., Zhang X., Guo X., Wang J., Jiang L., Liu X., Chen W., Chu J., Yan C., Ueno K., Ito S., Asami T., Cheng Z., Lei C., Zhai H., Wu C., Wang H., Zheng N., Wan J., D14–SCFD3-dependent degradation of D53 regulates strigolactone signalling. Nature 504, 406–410 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang L., Liu X., Xiong G., Liu H., Chen F., Wang L., Meng X., Liu G., Yu H., Yuan Y., Yi W., Zhao L., Ma H., He Y., Wu Z., Melcher K., Qian Q., Xu H. E., Wang Y., Li J., DWARF 53 acts as a repressor of strigolactone signalling in rice. Nature 504, 401–405 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukazawa J., Teramura H., Murakoshi S., Nasuno K., Nishida N., Ito T., Yoshida M., Kamiya Y., Yamaguchi S., Takahashi Y., DELLAs function as coactivators of GAI-ASSOCIATED FACTOR1 in regulation of gibberellin homeostasis and signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2920–2938 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arabidopsis Interactome Mapping Consortium , Evidence for network evolution in an Arabidopsis interactome map. Science 333, 601–607 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiratsu K., Mitsuda N., Matsui K., Ohme-Takagi M., Identification of the minimal repression domain of SUPERMAN shows that the DLELRL hexapeptide is both necessary and sufficient for repression of transcription in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321, 172–178 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szemenyei H., Hannon M., Long J. A., TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Science 319, 1384–1386 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peer W. A., From perception to attenuation: Auxin signalling and responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 561–568 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang R., Estelle M., Diversity and specificity: Auxin perception and signaling through the TIR1/AFB pathway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 21, 51–58 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chini A., Fonseca S., Fernández G., Adie B., Chico J. M., Lorenzo O., García-Casado G., López-Vidriero I., Lozano F. M., Ponce M. R., Micol J. L., Solano R., The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 448, 666–671 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thines B., Katsir L., Melotto M., Niu Y., Mandaokar A., Liu G., Nomura K., He S. Y., Howe G. A., Browse J., JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCOI1 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448, 661–665 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida A., Ohmori Y., Kitano H., Taguchi-Shiobara F., Hirano H. Y., Aberrant spikelet and panicle1, encoding a TOPLESS-related transcriptional co-repressor, is involved in the regulation of meristem fate in rice. Plant J. 70, 327–339 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emes R. D., Ponting C. P., A new sequence motif linking lissencephaly, Treacher Collins and oral–facial–digital type 1 syndromes, microtubule dynamics and cell migration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2813–2820 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long J. A., Ohno C., Smith Z. R., Meyerowitz E. M., TOPLESS regulates apical embryonic fate in Arabidopsis. Science 312, 1520–1523 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chini A., Fonseca S., Chico J. M., Fernández-Calvo P., Solano R., The ZIM domain mediates homo- and heteromeric interactions between Arabidopsis JAZ proteins. Plant J. 59, 77–87 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung H. S., Howe G. A., A critical role for the TIFY motif in repression of jasmonate signaling by a stabilized splice variant of the JASMONATE ZIM-domain protein JAZ10 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 131–145 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J., Harter K., Theologis A., Protein–protein interactions among the Aux/IAA proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11786–11791 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu J., Edwards R. A., Wong J. J., Manchak J., Scott P. G., Frost L. S., Glover J. N., Protonation-mediated structural flexibility in the F conjugation regulatory protein, TraM. EMBO J. 25, 2930–2939 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brantjes H., Roose J., van De Wetering M., Clevers H., All Tcf HMG box transcription factors interact with Groucho-related co-repressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1410–1419 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roose J., Molenaar M., Peterson J., Hurenkamp J., Brantjes H., Moerer P., van de Wetering M., Destrée O., Clevers H., The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf-3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature 395, 608–612 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orian A., Delrow J. J., Rosales Nieves A. E., Abed M., Metzger D., Paroush Z., Eisenman R. N., Parkhurst S. M., A Myc–Groucho complex integrates EGF and Notch signaling to regulate neural development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15771–15776 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekiya T., Zaret K. S., Repression by Groucho/TLE/Grg proteins: Genomic site recruitment generates compacted chromatin in vitro and impairs activator binding in vivo. Mol. Cell 28, 291–303 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein R. E., Jiménez G., Cook O., Gur D., Paroush Z., Huckebein repressor activity in Drosophila terminal patterning is mediated by Groucho. Development 126, 3747–3755 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiménez G., Paroush Z., Ish-Horowicz D., Groucho acts as a corepressor for a subset of negative regulators, including Hairy and Engrailed. Genes Dev. 11, 3072–3082 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muhr J., Andersson E., Persson M., Jessell T. M., Ericson J., Groucho-mediated transcriptional repression establishes progenitor cell pattern and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell 104, 861–873 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paroush Z., Finley R. L. Jr, Kidd T., Wainwright S. M., Ingham P. W., Brent R., Ish-Horowicz D., Groucho is required for Drosophila neurogenesis, segmentation, and sex determination and interacts directly with hairy-related bHLH proteins. Cell 79, 805–815 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H., Levine M., Ashe H. L., Brinker is a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 15, 261–266 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzamarias D., Struhl K., Functional dissection of the yeast Cyc8–Tup1 transcriptional co-repressor complex. Nature 369, 758–761 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komachi K., Redd M. J., Johnson A. D., The WD repeats of Tup1 interact with the homeo domain protein α2. Genes Dev. 8, 2857–2867 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chodaparambil J. V., Pate K. T., Hepler M. R., Tsai B. P., Muthurajan U. M., Luger K., Waterman M. L., Weis W. I., Molecular functions of the TLE tetramerization domain in Wnt target gene repression. EMBO J. 33, 719–731 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsumura H., Kusaka N., Nakamura T., Tanaka N., Sagegami K., Uegaki K., Inoue T., Mukai Y., Crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the yeast general corepressor Tup1p and its functional implications. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26528–26538 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu Z., Xu F., Zhang Y., Cheng Y. T., Wiermer M., Li X., Arabidopsis resistance protein SNC1 activates immune responses through association with a transcriptional corepressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13960–13965 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krogan N. T., Hogan K., Long J. A., APETALA2 negatively regulates multiple floral organ identity genes in Arabidopsis by recruiting the co-repressor TOPLESS and the histone deacetylase HDA19. Development 139, 4180–4190 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogas J., Kaufmann S., Henderson J., Somerville C., PICKLE is a CHD3 chromatin-remodeling factor that regulates the transition from embryonic to vegetative development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13839–13844 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H., Rider S. D. Jr, Henderson J. T., Fountain M., Chuang K., Kandachar V., Simons A., Edenberg H. J., Romero-Severson J., Muir W. M., Ogas J., The CHD3 remodeler PICKLE promotes trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22637–22648 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jennings B. H., Ish-Horowicz D., The Groucho/TLE/Grg family of transcriptional co-repressors. Genome Biol. 9, 205 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez D., Bowen A. J., Carroll T. S., Conlan R. S., The transcription corepressor LEUNIG interacts with the histone deacetylase HDA19 and mediator components MED14 (SWP) and CDK8 (HEN3) to repress transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 5306–5315 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han M., Park Y., Kim I., Kim E. H., Yu T. K., Rhee S., Suh J. Y., Structural basis for the auxin-induced transcriptional regulation by Aux/IAA17. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 18613–18618 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nanao M. H., Vinos-Poyo T., Brunoud G., Thévenon E., Mazzoleni M., Mast D., Lainé S., Wang S., Hagen G., Li H., Guilfoyle T. J., Parcy F., Vernoux T., Dumas R., Structural basis for oligomerization of auxin transcriptional regulators. Nat. Commun. 5, 3617 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korasick D. A., Westfall C. S., Lee S. G., Nanao M. H., Dumas R., Hagen G., Guilfoyle T. J., Jez J. M., Strader L. C., Molecular basis for AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR protein interaction and the control of auxin response repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 5427–5432 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song H., Hasson P., Paroush Z., Courey A. J., Groucho oligomerization is required for repression in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 4341–4350 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith P. A., Tripp B. C., DiBlasio-Smith E. A., Lu Z., LaVallie E. R., McCoy J. M., A plasmid expression system for quantitative in vivo biotinylation of thioredoxin fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 1414–1420 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ke J., Harikumar K. G., Erice C., Chen C., Gu X., Wang L., Parker N., Cheng Z., Xu W., Williams B. O., Melcher K., Miller L. J., Xu H. E., Structure and function of Norrin in assembly and activation of a Frizzled 4–Lrp5/6 complex. Genes Dev. 27, 2305–2319 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabsch W., XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 , The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terwilliger T. C., Adams P. D., Read R. J., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Afonine P. V., Zwart P. H., Hung L. W., Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: The PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 582–601 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J., Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Moriarty N. W., Mustyakimov M., Terwilliger T. C., Urzhumtsev A., Zwart P. H., Adams P. D., Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 352–367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.W. DeLano, The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Melcher K., Ng L. M., Zhou X. E., Soon F. F., Xu Y., Suino-Powell K. M., Park S. Y., Weiner J. J., Fujii H., Chinnusamy V., Kovach A., Li J., Wang Y., Peterson F. C., Jensen D. R., Yong E. L., Volkman B. F., Cutler S. R., Zhu J. K., Xu H. E., A gate–latch–lock mechanism for hormone signalling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature 462, 602–608 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/6/e1500107/DC1

Fig. S1. Sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of different transcriptional repressors, TFs, and adapters that interact with TPL/TPR.

Fig. S2. Charge distribution surface views of the complex between OsTPR2 TPD and the NINJA EAR motif.

Fig. S3. Biochemical and stuctural characterization of the TPR2 TPD tetramer.

Fig. S4. The rOsTPR2 protein contains a zinc finger structure.

Fig. S5. Structural overlay of OsTPR2 TPD apo and NINJA peptide–bound structures.

Fig. S6. Sequence alignment of the TPD of TPL and TPR proteins from rice (Os) and Arabidopsis (At).

Fig. S7. Structure of OsTPR2 TPD in complex with IAA10 EAR peptide.

Fig. S8. Structure of OsTPR2 TPD in complex with IAA1 EAR peptide.

Fig. S9. Structural comparison of NINJA, IAA10, and IAA1 peptide–bound OsTPR2 TPD structures.

Fig. S10. OsTPR2 TPD N176H forms higher-order oligomers.

Fig. S11. Relative TPD affinities of different EAR motifs.

Fig. S12. Effects of EAR point mutations on TPD binding.