Abstract

Diatoms are among the most diverse eukaryotic microorganisms on Earth, they are responsible for a large fraction of primary production in the oceans and can be found in different habitats. Pseudo-nitzschia are marine planktonic diatoms responsible for blooms in coastal and oceanic waters. We analyzed the transcriptome of three species, Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis, Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima and Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata, with different levels of genetic relatedness. These species have a worldwide distribution and the last one produces the neurotoxin domoic acid. We were able to annotate about 80% of the sequences in each transcriptome and the analysis of the relative functional annotations allowed comparison of the main metabolic pathways, pathways involved in the biosynthesis of isoprenoids (MAV and MEP pathways), and pathways putatively involved in domoic acid synthesis. The search for homologous transcripts among the target species and other congeneric species resulted in the discovery of a sequence annotated as Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS), found uniquely in Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata. The predicted protein product contained all the domains of the canonical metazoan sequence. Putative NOS sequences were found in other available diatom datasets, supporting a role for nitric oxide as signaling molecule in this group of microalgae.

Diatoms are a very diverse group of eukaryotic microalgae, estimated to include about 200,000 different species. They can be recorded in a broad range of environments (oceans, freshwaters, soil) where water and light are available and can thrive in a wide variety of temperature, light and nutrient conditions, indicating that a broad range of adaptive strategies evolved in this lineage1. As photosynthetic organisms, they have a huge ecological importance, being responsible for approximately 20% of the global photosynthetic carbon fixation, an amount comparable to that of all terrestrial rain forests2. Diatoms have complex signaling mechanisms that allow the perception of environmental cues3, produce signaling molecules such as sexual pheromones4 and can control their competitors and grazers by synthesizing specific anti-mitotic agents5,6.

The de novo sequencing of diatom genomes showed that this relatively recent eukaryotic lineage harbors a combination of genes and metabolic pathways first thought to be exclusive to plants and animals7,8. Diatoms have the urea cycle and the ability to generate chemical energy from the breakdown of lipids that were considered distinctive animal features, and also have the C4 photosynthetic pathway that was recorded only in some plants8.

Among diatoms, the genus Pseudo-nitzschia has attracted much attention because of its ability to synthesize the toxin domoic acid (DA), a neurotoxin causing Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning (ASP) in humans and reported as harmful also for marine vertebrates and sea birds9,10. The genus Pseudo-nitzschia is widely distributed around the world, with several species reported also in the Mediterranean Sea11.

In this study, we performed a comparative analysis of the de novo transcriptomes of three Pseudo-nitzschia species to obtain preliminary insights on their molecular toolkits and to identify physiological and metabolic differences amongst them. Two of the target species, Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis and Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima, are genetically closely related, and are cryptic species, i.e. they can only be distinguished with molecular markers12,13. Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata belongs to a different phylogenetic clade and produces DA14. The three species exhibit distinct species-specific patterns of the secondary metabolites oxylipins15, suggesting the presence of distinct functional traits also amongst morphologically and genetically closely related species. They regularly bloom in the Gulf of Naples16, have a broad global distribution11, and have different levels of genetic relatedness and different secondary metabolites production15. For two of these species, we recently optimized genetic transformation17.

The genome sequences of two other diatoms, Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Thalassiosira pseudonana7,8, and other transcriptome sequences produced within the Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP)18, aided in the definition of shared and unique properties.

Whole transcriptome functional comparisons indicated that, in the exponential phase of growth, the three species express an overall comparable set of functions, however small differences could be found when looking in details at specific pathways, such as the pathways involved in the biosynthesis of isoprenoids (MAV and MEP pathways). This analysis highlighted the presence of a transcript encoding for a Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS), present in Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata but not in the other two diatoms. We expanded the search for NOS sequences in other datasets available for diatoms and present the result of a phylogenetic analysis supporting, for the first time, the existence of such enzyme in this group of algae.

Results

Sequencing data and assembly quality

The total number of assembled reads was ~35 million for Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis, ~34 million for P. delicatissima and ~118 million for P. multistriata (Table 1). The higher number of reads for P. multistriata is most likely due to the different sequencing methodology that resulted in deeper sequencing. The total contigs number, the N50 values of each transcriptome and the corresponding proteome sizes were comparable (Table 1).

Table 1. General statistics of transcriptomes and proteomes assemblies in the three Pseudo-nitzschiaspecies.

| DATA TYPE | P. arenysensis | P. delicatissima | P. multistriata |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contigs number | 19,852 | 17,595 | 21,632 |

| N50 | 2,224 | 2,560 | 2,340 |

| Reads | 35,278,872 | 34,418,919 | 118,619,362 |

| G + C content(%) | 46.9 | 48.1 | 48.8 |

| Median Contigs length (bp) | 1,568 | 1,717 | 1,730 |

| Average Contigs length (bp) | 1,865 | 2,092 | 1,984 |

| Protein number | 19,853 | 17,598 | 20,176 |

| Median Proteins length (aa) | 403 | 429 | 419 |

| Average Proteins length (aa) | 517 | 545 | 500 |

| 458 CEGs Complete (%) | 85.48 | 89.11 | 87.50 |

| 458 CEGs Complete + Partial(%) | 88.71 | 92.74 | 89.52 |

The transcriptome size and sequencing statistics of other Pseudo-nitzschia species (retrieved from the publicly available transcriptomes sequenced within the MMETSP) were overall similar to those of the three species of interest (the only exception being one of four conditions for Pseudo-nitzschia fraudulenta), indicating homogeneity within the genus (Supplementary Table S1).

Completeness of the P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima and P. multistriata transcriptomes, as percentage of complete core proteins, was estimated to be higher than 85% (Table 1) using CEGMA analysis. The completeness resulted even higher (>88%) when considering the percentage of the partial core proteins (fragmented or truncated alignment) aligned against the reference dataset (Table 1) and resulted comparable to the completeness of datasets derived from the genomes of other diatom species (91.13% and 90.73% for Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Thalassiosira pseudonana, respectively).

Functional annotations

Using the Annocript pipeline for annotation19, about 80% of the proteome sequences could be annotated: 15,818 (80%), 14,420 (82%) and 16,183 (80%) proteins annotated for P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima and P. multistriata respectively (Supplementary Tables S2, S3 and S4). Blastp results showed that, in terms of homology, the top ten matches mostly belonged to Heterokontophyta (Supplementary Fig. S1).

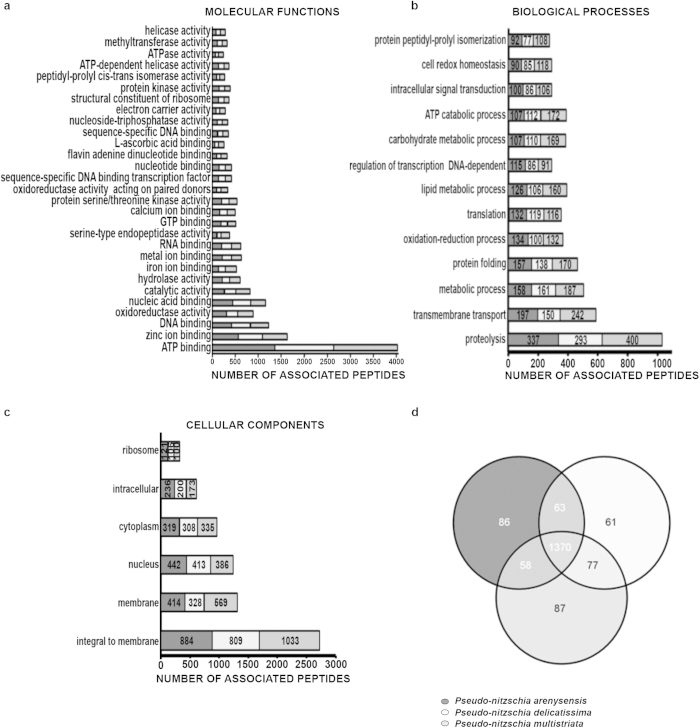

The annotation process assigned a similar number of Gene Ontology (GO) terms to each proteome (1577, 1571 and 1592 in P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima and P. multistriata, respectively), the majority of which belonged to the Molecular Function category. The GO terms “ATP-binding” in the Molecular Function category, “Proteolysis” in the Biological Process category and “Integral to membrane” in the Cellular Components category were the most represented (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 1. Breakdown of the GO terms describing the annotated proteomes.

GO-terms belonging to Molecular Function (a), Biological Processes (b) and Cellular Components (c) associated to at least 100 peptides, for Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis (dark grey), Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima (light grey) and Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata (grey). On the y axis are the GO-terms, on the x axis are the number of sequences associated to each GO-term. (d) Venn diagram of shared/unique GO terms among the three Pseudo-nitzschia: external numbers correspond to the number of unique GO terms for each species. Numbers in the overlapping areas correspond to the shared GO terms. 1370 GO terms are shared among the three species.

GO function enrichment analyses did not reveal any specific enrichments (Fisher test, data not shown), we were however able to identify uniquely annotated functions in each species of interest. The Venn diagram in Fig. 1d shows the unique mapping of 86, 61 and 87 GO terms in P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima and P. multistriata, respectively. Interestingly, while the unique P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima GO terms are mainly generic terms, the P. multistriata list of unique GO terms contains terms related to specific functions, such as ‘nitric oxide synthase’ (NOS) and ‘regulation of TOR signaling cascade’, absent in the other two species annotations.

The number of general pathways identified in P. arenysensis and in P. delicatissima was 62, whilst in P. multistriata it was 60 (Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Essential and secondary metabolic pathways were present (Supplementary Table S7 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

The C4 metabolism and the urea pathway, both unexpectedly discovered in diatom genomes8, were present in all three Pseudo-nitzschia (Supplementary Tables S8 and S9). Notably, P. multistriata lacked the PEPCK transcript, differently from P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima (Supplementary Table S10). However, a blastp search in the P. multistriata genome (Ferrante, in preparation) retrieved a PEPCK sequence (data not shown), indicating that the enzyme is present in P. multistriata.

Comparative transcriptomics

To identify novel and unique features of the target Pseudo-nitzschia species, we determined the homology level of the three transcriptomes among them as well as with respect to the pennate diatom P. tricornutum and the centric diatom T. pseudonana.

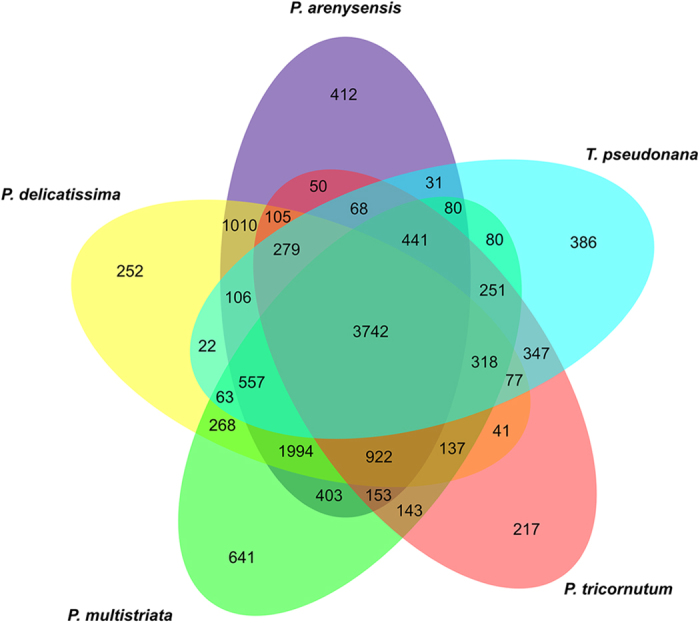

Table 2 reports the number of groups of homologous proteins found by OrthoMCL and their distribution in four classes of homology type. The species that had the highest percentage of similarity with all the other species was P. delicatissima and the one that shared less was T. pseudonana (Table 3). Specifically, we found that 10%, 14% and 22% of the proteome of the three Pseudo-nitzschia species was apparently not shared with other species, while 25% of the proteome of P. tricornutum and 39% of the proteome of T. pseudonana appeared to be missing from the other species (Table 3). The majority of the orthologous groups were common among all the species tested (Fig. 2): the central part of the Venn diagram, representing the overlapping among all the datasets used, showed 3,742 (27.52% of the total groups) groups of sequences common to all. The number of groups only shared between P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima was 1,010, highlighting, as expected, a closer relation between them with respect to P. multistriata. The groups shared only by P. multistriata and P. arenysensis were 403 whereas 268 groups were shared only by P. multistriata and P. delicatissima, suggesting that P. multistriata might be more similar to P. arenysensis than to P. delicatissima.

Table 2. Ortholog groups detected in the transcriptomes of the three Pseudo-nitzschiaspecies (P. multistriata, P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima) and in those of the model pennate diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum and the centric Thalassiosira pseudonana.

| Group types | Number of homologous groups | % on the total groups |

|---|---|---|

| ONEtoONE | 3752 | 27.6% |

| ONEtoMANY | 7301 | 53.7% |

| MANYtoMANY | 635 | 4.7% |

| PARALOGS | 1908 | 14.0% |

| TOTAL GROUPS | 13596 |

Table 3. Total number of peptides and number of peptides with at least one ortholog in the three Pseudo-nitzschiaspecies and in the model pennate diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutumand the centric Thalassiosira pseudonana, and percentage of peptides of each species finding homology with at least another species.

| Species | Total number of peptides | Number of orthologs | % with homologs |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. arenysensis | 19853 | 17156 | 86.4 |

| P. delicatissima | 17598 | 15908 | 90.4 |

| P. multistriata | 20176 | 15755 | 78.1 |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 10402 | 7865 | 75.6 |

| Thalassiosira pseudonana | 11674 | 7135 | 61.1 |

Figure 2. Venn diagram showing distribution of orthologous groups among five species of diatoms.

External numbers correspond to groups unique to a given species (in-paralogs). Numbers in the overlapping areas correspond to groups of orthologs.

The four pennate diatoms together shared 922 groups of proteins, showing significant enrichments for functions related to the carbohydrate metabolic process, regulation of transcription and signal transduction (Supplementary Table S11). The species with the highest number of ‘in-paralogs’ (groups of proteins present uniquely in a single species) was P. multistriata followed by P. arenysensis, T. pseudonana, P. delicatissima and P. tricornutum (Fig. 2, external numbers).

Examining the annotations corresponding to the proteins included in the ‘in-paralogs’ group and to the unique proteins (proteins that were not classified into any homology group either in the same species or in other species) of P. arenysensis (Supplementary Table S12), P. delicatissima (Supplementary Table S13) and P. multistriata (Supplementary Table S14), we observed that around 55% of the species-specific proteins did not get any annotation, and around 33% were annotated as predicted or uncharacterized proteins. The majority of the remaining species-specific proteins corresponded to leucine-rich repeat containing proteins, zinc finger like proteins, trypsins, lipases, heat shock proteins, transporters and receptors, indicating that rapidly evolving proteins exist in these classes. In P. arenysensis, the most represented molecular function in the list of species-specific proteins was related to the serine-type endopeptidase activity, while in P. delicatissima terms related to energy metabolism were abundant. Furthermore, the P. multistriata species-specific protein list was enriched in functions related to lipid metabolism, proteolysis, nitric oxide synthase, serine type endopeptidase activity, hydrolase and lipase activity, iron and oxygen binding. Finally, the species-specific P. multistriata list included proteins that were annotated as antibiotic synthesizing proteins and acetylcholine subunit type receptors.

Identification of a NOS sequence in diatoms

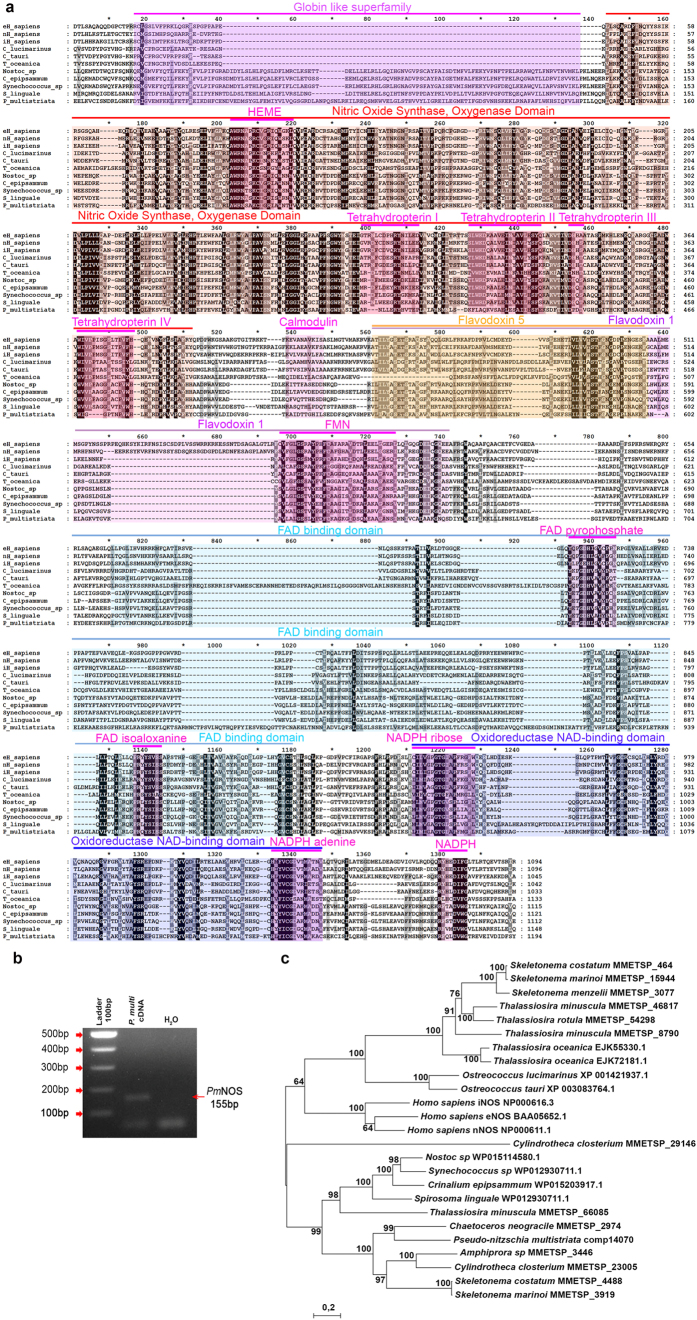

Because of the important role for nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in phytoplankton20, we focused on the ‘Nitric Oxide Synthase’ GO term uniquely annotated in P. multistriata. The presence of NOS sequences in photosynthetic organisms has been debated21. However, recently a NOS sequence was characterized in the green microalga Ostreococcus tauri22. A blastn search in the P. multistriata genome (Ferrante, in preparation) with the PmNOS transcript retrieved a locus with 99% identity (data not shown). The PmNOS transcript was analyzed for its sequence completeness, and the sequence was manually curated comparing the transcript isoforms and the genome sequence. The predicted protein had domain structure identical to the canonical metazoan NOS, with the two typical domains, the oxygenase (oxy) and the reductase (red) domains, fused in a unique sequence. Moreover, all the domains required for the enzymatic activity, Heme, Tetrahydropterin I-IV, Calmodulin, FMN, FAD pyrophosphate, FAD isoaloxanine, NADPH ribose, NADPH adenine, NADPH, were present (Fig. 3a). As an independent validation of the in silico data, we performed an RT-PCR amplifying PmNOS in three P. multistriata strains different from the ones used to produce the transcriptome or the genome (Fig. 3b and data not shown), confirming expression in standard growth conditions.

Figure 3. Analysis of the Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata nitric oxide synthase (PmNOS).

(a): Protein alignment of P. multistriata PmNOS with the corresponding NOS of Homo sapiens, cyanobacteria (Nostoc sp, Crinalium epipsammum, Synechococcus sp), bacteria (Spirosoma linguale), Mamiellophyceae (Ostreococcus tauri and O. lucimarinus) and diatoms (Thalassiosira oceanica), showing domains and conservation; (b): RT-PCR amplification of a PmNOS fragment, lane 1, 100 bp ladder, lane 2, P. multistriata cDNA, lane 3, blank; (c): Neighbor joining three phylogeny of NOS protein sequences identified in diatoms, cyanobacteria, Homo sapiens and Ostreococcus species.

PmNOS blastp searches in the NCBI database retrieved as top hits cyanobacterial sequences that displayed a putative canonical NOS (deposited in the database but not described in literature) followed by many vertebrates isoforms. The identity with the NOS sequence characterized in the green alga Ostreococcus tauri22 was lower (31%).

A PmNOS blastp search against the available diatom genomes (P. tricornutum, T. pseudonana, Fragilariopsis cylindrus, Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries) did not retrieve any sequence, while in other diatom protein datasets produced within the MMETSP project we could find putative NOS sequences (Supplementary Table S15 online). Interestingly none of the other Pseudo-nitzschia species sequenced in the MMETSP displayed any canonical NOS sequence, only separated oxy and red domains could be found. On the contrary, many centric diatoms species displayed in most of the cases two transcripts (Supplementary Table S15 online), one coding for a canonical NOS sequence with similarity to the Ostreococcus NOS sequence and one that had similarity with the cyanobacteria NOS sequence, sometimes lacking the globin domain. Moreover, when different datasets for the same strain grown in different conditions were available, the NOS sequence was not retrieved in all growth conditions (see Thalassiosira minuscula strain CCMP1093 and Thalassiosira rotula strain GSO102, Supplementary Table S15 online), indicating a possible regulation of NOS expression.

A phylogenetic tree of all diatom NOS sequences, including two Thalassiosira oceanica sequences found in NCBI and deriving from the genome sequence of this species23, showed two well-supported clades clearly separating the sequences by their similarity with the cyanobacteria or with the green alga Ostreococcus and Homo sapiens sequences (Fig. 3c). PmNOS confirmed its similarity with the cyanobacteria sequences together with more ancestral pennate diatoms such as Amphiprora sp and Cylindrotheca closterium. The two transcripts found in Thalassiosira minuscula, Skeletonema costatum or S. marinoi clustered each in one of the two clades.

Isoprenoids and domoic acid production

Domoic Acid (DA) is a member of kainoids, a group of compounds resembling glutamate. The proposed route for its synthesis is the fusion of two hypothetical precursors, one deriving from the citric acid cycle (a glutamate-like compound) and the other deriving from the isoprenoid pathways (a geranyl type molecule)24.

Although toxicity of the strains used to produce the transcriptomes was not measured at the time of RNA extraction, the P. multistriata strain selected for the study had been shown to produce DA, while all P. arenysensis strains tested in the laboratory have never been found to produce DA (Ferrante, unpublished, A. Zingone, personal communication). We compared the expression levels of transcripts associated to pathways that have been associated to DA biosynthesis (isoprenoid biosynthesis, in Fig. S2 and Table S6, acetyl-CoA biosynthesis, geranyl diphosphate biosynthesis, isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis via DXP pathway, isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis via mevalonate pathway, L-glutamate biosynthesis via GLT pathway, L-proline degradation into L-glutamate, pyruvate metabolism, tricarboxylic acid cycle, in Fig. S3 and Table S7)25 in the toxic P. multistriata with respect to the non-toxic P. arenysensis and did not find substantial differences. In a study comparing P. multiseries cells in the stationary phase (high DA production) versus the exponential phase (low DA production) a number of genes resulted upregulated26. We searched for homologs of these genes and found similar FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) values for each given transcript in the three species except for SLC6 (Sodium and Chloride-dependent amino acid transporter) for which the mean P. multistriata FPKM value was 7 and 11 fold higher than in P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima, respectively (35.16 FPKM versus 4.92 and 3.15 FPKM), indicating that this transcript might be more expressed in a toxin-producing species.

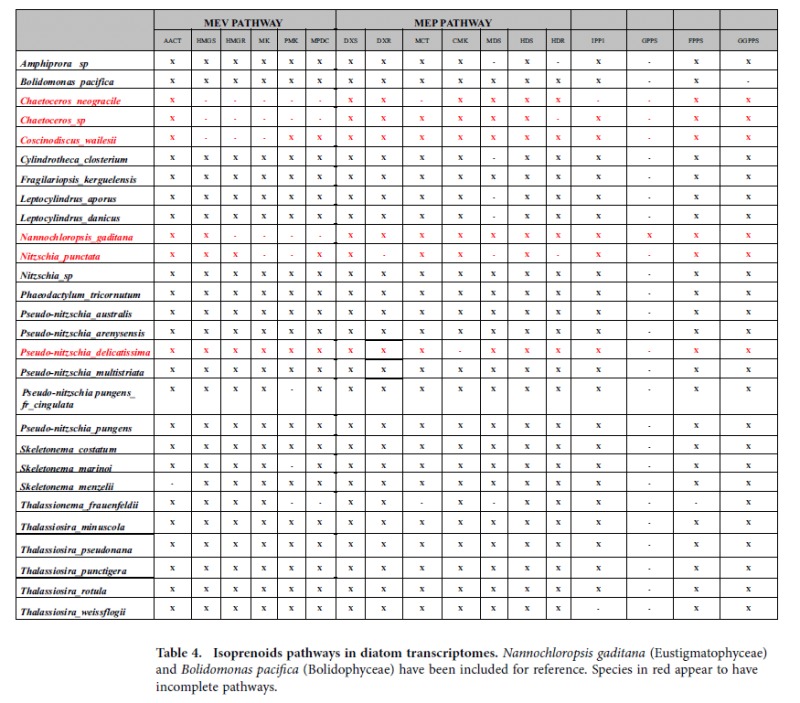

Finally, we looked at completeness of the isoprenoid pathway. Isoprenoids are a class of organic compounds including sterols, brassinosteroids, cytokinins, phytols, giberellins, plant hormones and carotenoids, and two routes are known for their production: the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) routes27.

The two isoprenoids routes were clearly identified in the three Pseudo-nitzschia species, with only CMK, one of the MEP route enzymes, missing in P. delicatissima (Table 4). The analysis was extended to other diatom datasets available in the MMETSP database at the time of the study, revealing that the MVA pathway appeared to be absent in two Chaetoceros species, and it was incomplete in Nitzschia punctata, Coscinodiscus wailesii, Pseudo-nitzschia pungens fr. cingulata, Skeletonema marinoi and Thalassionema frauenfeldii. On the other side, almost all enzymes of the MEP pathway were present in diatoms, except for Nitzschia punctata, which lacked a few of them (Table 4).

Table 4. Isoprenoids pathways in diatom transcriptomes.

Nannochloropsis gaditana (Eustigmatophyceae) and Bolidomonas pacifica (Bolidophyceae) have been included for reference. Species in red appear to have incomplete pathways.

The geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS) enzyme, responsible of the synthesis of the geranyl diphosphate from the MEP pathway in the plastid, appeared to be absent in all analyzed species (Table 4). A Nannochloropsis gaditana28 GPPS protein blastp against the P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima and P. multistriata datasets demonstrated that the sequence was present, albeit annotated with a different name (Solanesyl-diphosphate synthase). Phylogenetic trees to look at the conservation of key enzymes in the isoprenoid pathways among diatoms always provided a well-resolved phylogeny of the enzymes, with two main clades grouping the pennate or centric lineages. For all the proteins examined the nodes in each phylogenetic tree were well-supported. In the clade containing the Pseudo-nitzschia, P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima grouped together, as expected, and resulted more divergent with respect to the other congeneric species (Supplementary Figure S4).

Discussion

The comparative analysis of the transcriptomes of the three Pseudo-nitzschia species revealed an overall similarity among the datasets but also provided an inventory of species-specific transcripts. The two genetically closely related cryptic species, Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis and P. delicatissima appeared to have very similar transcriptomes, while P. multistriata displayed a larger fraction of unique functions, including a nitric oxide synthase (PmNOS), whose predicted protein structure had domains identical to the metazoan NOS. The transcriptomes of the three congeneric species analyzed in this study derived from strains grown at the same experimental conditions and collected in the exponential growth phase, thus providing a comparison between the genetic distance and their basic metabolic pathways. It is conceivable that a greater molecular diversity and larger differences in transcript levels might be detected when comparing responses to markedly different perturbations, which may highlight species-specific physiological capabilities/adaptations29. Even larger differences can be expected when comparing the response to the same experimental condition of species belonging to distinct genera. In fact, a study among two pennate diatoms, Fragilariopsis cylindrus and Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries, and one centric diatom, Thalassiosira pseudonana, grown in nitrogen-deprived condition, showed differences in non-orthologous gene subsets and in transcription levels, with less than 5% of the shared orthologous gene clusters similarly transcribed30.

For the general pathway content, our annotation retrieved sequences for all the major primary metabolic pathways, and complete C4, urea and isoprenoid pathways could be found, with little exceptions. A complete urea cycle, involved in nutrient sensing and contributing to the response of diatoms to episodic nitrogen availability, operates in Phaeodactylum tricornutum31 and our study indicated that in Pseudo-nitzschia species the same mechanisms could be used. In the P. multistriata transcriptome, PEPCK was absent but the gene was present in the genome, suggesting low levels of expression in the sample analyzed.

The presence of a canonical NOS sequence in P. multistriata was intriguing. It is important to note that we found the NOS sequence in the P. multistriata genome produced from an axenic strain, different from the strain chosen to produce the transcriptome, proving that this sequence is present in the species and does not derive from possible contaminations. The presence of a NOS enzyme in plants, green algae and diatoms is still a matter of debate21,32,33, however the product of its activity, nitric oxide, has been identified in diatoms and correlated with perception of stress cues20,34. Exploring different databases, we looked for the presence of NOS sequences in other diatom species. We could not find putative NOS sequences in any Pseudo-nitzschia transcriptome, or in the genome of P. multiseries. In these species, the oxygenase and reductase domains are present as separate genes. The absence of NOS in the P. multiseries genome suggests that absence of NOS in the transcriptomes of most Pseudo-nitzschia could be truly due to absence of the gene rather than to a bias in sequencing depth, sequence assembling or to suppressed expression. NOS sequences could not be found also in the genomes of the pennate diatoms F. cylindrus and P. tricornutum and of the centric diatom T. pseudonana. Two putative NOS sequences were instead present in the genome of Thalassiosira oceanica23 and one or more putative NOS sequences were found in the transcriptomes of species of the genera Thalassiosira, Skeletonema and Cylindrotheca sequenced in the MMETSP. We found a putative NOS in the Skeletonema marinoi strains FE7 and FE60, but not in the S. marinoi strain SkelA, where only oxygenase and reductase separated domains could be identified. In addition, for Thalassiosira rotula (strain GSO102) and Thalassiosira minuscula (strain CCMP1093), for which samples of different growth conditions were sequenced, putative NOS sequences could be found only in one or two but not in all conditions. These observations suggest that NOS expression could be regulated.

The presence of more than one NOS sequence in some species is puzzling. Without a reference genome for these species, any attempt to reconstruct the evolutionary history of these sequences proves difficult. Information about synteny or intron number and distribution might help in defining the relationships among the sequences. From our analyses, pennate diatoms, which are phylogenetically more recent than centrics35, seem to have only one gene, more similar to cyanobacterial NOS than to human or green algae, with the exception of Cylindrotheca closterium that has a second sequence with an ambiguous position in the phylogenetic tree.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that nitric oxide in marine phytoplankton is able to remove the oxidative damage due to different environmental stressors. NOS expression could be upregulated in response to stress conditions, as suggested by Vardi34,36, who demonstrated that nitric oxide is produced by diatoms exposed to sub lethal doses of the (2E,4E/Z)-decadienal aldehyde, a molecule that is synthesized when diatom cells are broken either by grazing or cell death. Functional studies on PmNOS will be needed to define the profile of expression and the possible role of this gene.

In P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima, leucine-rich repeat proteins were the majority in the list of unique proteins. Leucine-rich repeat proteins are required in various cellular processes and it seems that their major role would be protein-protein interaction. As they evolve rapidly, their repetitive structure can be useful in processes in which the rapid generation of new variants is needed, such as plant disease resistance and bacterial virulence37. The species-specific protein list contained mainly proteins associated to unknown functions, and proteins associated to known functions that were present in all the species considered. These unique proteins associated to common functions are likely divergent proteins belonging to related gene families. Unique and highly divergent proteins are likely responsible for the plasticity of the species and will deserve further studies.

Based on studies on P. multiseries in high DA producing versus low DA producing growth conditions26, we looked at genes hypothetically involved in DA synthesis. No major differences could be detected among our three target species, except for the SLC6-sodium and chloride-dependent amino acid transporter, very similar to kainoids molecules transporters (to which DA belongs) that could be involved in the transport of DA inside/outside the cell, which was, at least in silico, over represented only in the toxic P. multistriata.

The mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways were present in Pseudo-nitzschia, except for the CMK enzyme, which was absent in P. delicatissima, either due to technical issues or to a true loss during evolution. Compensatory routes in any case are known to overcome the lack of some enzymes38,39. Isoprenoids are considered to be the largest group of natural products, playing a wide variety of roles in physiological processes of plants and animals. Ancestral eukaryotes and animals generally have only the MVA pathway, while many photosynthetic organisms have acquired also the MEP pathway. The green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae have only the more recently acquired MEP pathway and eliminated the more ancestral MVA28. It was previously reported that Stramenopiles, as diatoms (P. tricornutum, T. pseudonana, Nitzschia ovalis) and brown algae (Ectocarpus siliculosus), had retained both39, however our comparative studies using several diatom species indicated variations and absence of some enzymes in different species, for instance in the genus Chaetoceros. Chemical searches for the ending products of the two pathways are needed to validate the possible different utilization of the pathways. The phylogenetic analysis of selected enzymes of the two isoprenoids pathways showed a good separation between the two groups of pennate and centric diatoms and confirmed the divergence between P. multistriata and the two cryptic species P. arenysensis and P. delicatissima. This divergence was strengthened also by the recovering of P. multistriata into the same clade with P. australis and P. pungens, two toxic Pseudo-nitzschia species belonging, together with P. multistriata, to the ‘seriata’ group40. P. multistriata was also more distantly related from the two other species in terms of percentages of shared proteins (Fig. 2).

When the analyses were extended to other diatom species, a broad diversity could be observed, suggesting caution in formulating general hypotheses based on information deriving from the study of a single diatom genome or transcriptome.

The representativeness of genes in whole transcriptome data with respect to genome data is not complete; however, transcriptome completeness CEGMA analysis for the three species indicated that the datasets were sufficiently representative of the potential gene repertoire. Despite the biases intrinsic to de novo transcriptome assemblies without a reference genome, we were able to describe and compare the basal physiological state of the species of interest. When comparing the three Pseudo-nitzschia to the two model diatoms P. tricornutum and T. pseudonana, we found that the pennate species had between 90 and 75% of peptides with at least one ortholog in another species, while T. pseudonana had 39% of peptides not shared with the four pennate diatoms, in agreement with what reported previously in similar comparisons including this species7,30.

Finally, we could find unique and still undiscovered functions, reporting for the first time the presence of a NOS sequences in diatoms.

Materials and Methods

Strains and RNA extraction

Pseudo-nitzschia strains were isolated at the Long Term Ecological Research Station MareChiara in the Gulf of Naples (40°48.5’N, 14°15’E). Clonal cultures were established by isolating single cells from phytoplankton net samples collected from the surface layer of the water column. Cultures were grown in sterile filtered oligotrophic seawater amended with f/2 nutrients41 at a temperature of 18 °C, at 12:12 h light:dark cycle, with a photon flux of 100 μmol photons m−2s−1.

Strains selected for RNA extraction for RNA-seq were Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata B85742, Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis B593 and Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima B653, both isolated on 27/04/2011. RNA was also extracted from the Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata strain B936, isolated on 24/05/2012, for RT-PCR validations.

Cultures with cell density of 2 × 105 cells ml−1 were harvested by filtration onto 1.2 μm pore size filters (RAWP04700 Millipore) and frozen in High Pure RNA Isolation reagent (Roche Applied Science). Before proceeding to the total RNA extraction protocol according to the manufacturer’s instructions, cells were disrupted with glass beads (G1277, Sigma-Aldrich) on a thermo-shaker (Eppendorf) at 60 °C for 10 minutes at maximum rpm. RNA was further purified on Qiagen columns (74104, RNeasy Mini Kit, including a step with DNase digestion). RNA concentration was determined using a Qubit®2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and a quality check was performed by gel electrophoresis (1% agarose w/v) and an Agilent2100 bioanalyzer.

Transcriptome sequencing, assembling and proteome annotation

Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima and Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis library preparation and sequencing were performed as part of the Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP) (http://marinemicroeukaryotes.org/)18. RNA libraries with an insert size of about 200 bp were sequenced from both ends (paired-end reads 2 × 50-nt) on the Illumina Hi-Seq2000. Assembly was performed by the National Center for Genome Resources (NCGR, http://www.ncgr.org/) using ABySS and CAP343. Transcriptome IDs are MMETSP0327 (Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima) and MMETSP0329 (Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis).

Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata RNA-seq was made in collaboration with the JGI (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/) within the project “A deep transcriptomic and genomic investigation of diatom life cycle regulation”. Raw reads are available at http://genomeportal.jgi.doe.gov/pages/dynamicOrganismDownload.jsf?organism=PsenittraphaseII, the library selected for transcriptome assembly, corresponding to sample B857, is HCUN. Poly-(A) RNA was isolated from 5 μg total RNA using Dynabeads mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen). Purified RNA was then fragmented using RNA Fragmentation Reagents (Ambion) at 70 °C for 3 mins, targeting fragments range 200–300 bp. Fragmented RNA was purified using Ampure XP beads (Agencourt). Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript II Reverse Transcription (Invitrogen). Double stranded cDNA fragments were purified and selected for targeted fragments (200–300 bp) using Ampure XP beads. The cDNA was blunt-ended, poly-adenylated, and ligated with library adaptors using Kapa Library Amplification Kit (Kapa Biosystems). Digestion of dUTP was performed using AmpErase UNG (Applied Biosystems) to remove second strand cDNA. Digested cDNA was cleaned up with Ampure XP beads. This was followed by amplification by 10 cycles PCR using Kapa Library Amplification Kit (Kapa Biosystems). The final library was cleaned up with Ampure XP beads. Sequencing was done on the Illumina platform generating paired end reads of 150 bp each. Raw reads were filtered and trimmed based on quality and adapter inclusion using Trimmomatic44 with the following parameters: threads = 20; phred = 64; ILLUMINACLIP:illumina_adapters.fa:2:40:15-LEADING:5-TRAILING:5-SLIDINGWINDOW:5:20-MINLEN:100. Reads were then normalized using the normalize_by_kmer_coverage.pl script from Trinity44 (ver. r2013_08_14) with the following parameters: seqType = fq; JM = 240G; max_cov = 30; SS_lib_type = RF; JELLY_CPU = 24.

Assembly was performed using Trinity on the trimmed, filtered and normalized reads using these parameters: seqType = fq; JM = 220G; inchworm_cpu = 22; bflyHeapSpaceInit = 22G; –bflyHeapSpaceMax = 220G; bflyCalculateCPU; CPU = 22; SS_lib_type = RF; min_kmer_cov = 2. Putative protein translations were extracted using ESTScan (v3.0.3, default parameters)45 based on the MMETSP protocol. Peptides shorter than 30 aa were filtered out. The contigs and peptide sequences for Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata can be found in the Supplementary Information. Peptide sequences, from all the species, were used for the subsequent analyses. To annotate the translated transcriptome we used the custom pipeline Annocript19 (See https://github.com/frankMusacchia/Annocript/tree/master/GUIDE). We used the Swiss-Prot (SP) and UniRef9046 (version: August 2013) for the blastp against proteins with the following parameters: word_size = 4; e-value = 10−5; num_descriptions = 5; num_alignments = 5; threshold=18. For each sequence the best hit, if any, was chosen. Rpsblast parameters, to identify domains composition of putative proteins in the Conserved Domains Database47, were: e-value = 10−5; num_descriptions = 20; num_alignments = 20.

The software returned GO functional classification48, the Enzyme Commission IDs49 and Pathways50 descriptions associated to the resulting best matches.

Finally, we removed from the transcriptomes sequences matching with bacterial ribosomal sequences. CEGMA v2.551 was used to provide the completeness of the transcriptome data using the set of 248 most highly conserved Core Eukaryotic Genes (CEGs). For comparisons purpose, CEGMA was also used with the Phaeodactylum tricornutum (v2.19) and Thalassiosira pseudonana (v1.19) genome data downloaded from EnsemblProtists52,53.

Paired aligned reads were used to calculate the Counts Per Million mapped reads (CPM) and the Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped (FPKM) of each sequence for each transcriptome as measure of expression levels. The CPM values were calculated as follows: reads paired aligned*1,000,000/total paired aligned reads. The FPKM were calculated as follows: FPKM = [mapped reads pairs]/([length of transcript]/1000)/([total reads pairs]/106).

To avoid sequencing and assembly artifacts we selected only the contigs showing an expression level with CPM greater than 1. R scripts were used to perform further analyses (http://www.r-project.org/).

For comparisons among the proteomes, we used FPKM. Between species we used the t-test to compare the FPKM for groups of peptides associated to the same GO/pathway and the Fisher exact test to compare the corresponding proportions of transcripts. Inside species we performed a GO enrichment analysis of the homologous peptides using the Fisher exact test and correcting p-values with the Benjamini and Hochberg method54.

Isoprenoid pathway identification

The list of the enzymes involved in the isoprenoid pathway was taken from Radakovits et al.28 describing the Nannochloropsis gaditana genome, and from Vranová et al.55.

To verify the presence of enzymes involved in the synthesis of isoprenoids in diatom species, the datasets available at the time of the analysis (see Supplementary Note) were downloaded from the MMETSP website (http://camera.calit2.net/mmetsp/list.php).

For each species, the corresponding isoprenoid pathway enzyme sequences were retrieved from the respective annotation tables generated in the MMETSP. The corresponding Nannochloropsis gaditana sequence IDs were retrieved from Radakovits et al.28, and the relative sequences were downloaded from the Nannochloropsis genome portal at the web address http://www.nannochloropsis.org/.

The Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Thalassiosira pseudonana protein sequences were identified by tblastn using Pseudo-nitzschia transcript sequences as query in the EnsemblGenomes portal53.

For each protein, the corresponding longest isoform, if any, was taken (see Supplementary Note). To verify the accuracy of annotations, the longest corresponding isoform for each protein was blasted in the NCBI database. For phylogenetic analyses, protein sequences were aligned using the ClustalX program v2.156 with default parameters for the “complete alignment”. To generate phylogenetic trees we used the Bootstrap Neighbor Joining algorithm with random number generator seed = 111 and Number of bootstrap trials = 10000. Trees were exported to the NJPlot program and then converted in graphic format.

Comparisons with other diatom species

To compare our transcriptomes statistics with the other diatoms sequenced through the MMETSP, the datasets corresponding to selected species (see Supplementary Table 1) were downloaded from the MMETSP website. The number of contigs was retrieved from the stats.txt file, relative to each species.

To predict orthologs and in-paralogs we used OrthoMCL (v2.0.8) with the 5 proteomes of P. multistriata, P. arenysensis, P. delicatissima, P. tricornutum and T. pseudonana. OrthoMCL is a tool to group proteins into ortholog/paralog groups by their sequence similarity exploiting blastp and a Markov clustering (MCL) algorithm (v12-135)57,58. The P. tricornutum (v2.19) and T. pseudonana (v1.19) proteomes were downloaded from EnsemblProtists release 19 (http://protists.ensembl.org/)53.

Orthologs from the five species were clustered using the following settings: E-value cutoff = 10E-5 and MCL inflation index = 1.5.

For each tested species, proteins into ortholog groups were counted by custom perl and R scripts and classified as follows: i) one-to-one orthologs: at most one corresponding ortholog for each species; ii) one-to-many and many-to-many orthologs: more than one ortholog in at least one of the species tested; iii) in-paralogs: two or more similar sequences in exclusively one species.

Nitric oxide synthase analysis

Using the Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata sequence as a query for blastp searches against the NCBI database, the NOS sequences of Nostoc sp (WP_015114580.1), Synechococcus sp (WP_006458277), Spirosoma linguale (WP_012930711.1), Crinalium epipsammum (WP_015203917.1) were retrieved. NOS sequences of Ostreococcus lucimarinus (XP_001421937.1) and Thalassiosira oceanica (EJK55330.1 and EJK72181.1) were retrieved by blastp search against the NCBI database using the NOS sequence of Ostreococcus tauri (XP_003083764.1). The three Homo sapiens NOS sequences (iNOS-inducible NP_000616.3, eNOS-endothelial BAA05652.1 and nNOS-neuronal NP_000611.1) were downloaded from the NCBI protein database.

The NOS sequences from the other diatom species were obtained as follow: peptides files of each species were downloaded from the MMETSP website. Each peptides file was indexed (following NCBI instructions: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1763/) and searched using the Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata NOS sequence as a query in a blastp search with default parameters. The sequences with highest similarity were blasted against the non-redundant (NR) NCBI database to verify the identity. Finally the NOS sequences selected were aligned and analyzed with the Mega6 software. Sequences alignments were performed by selecting the ClustalW alignment tool and the phylogenetic evolutionary analysis was performed selecting the Maximum likelihood Tree test with 10,000 bootstrap replications.

For RT-PCR amplification, the Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata strain B936 was used. Primers used to amplify a 155 bp long PmNOS fragment were: PmNOS_Forward 5’-CCCAGTATCGTGCAAACAGG and PmNOS_Reverse 5’-AGGTCTTTGTCCGCATAGCC. Taq DNA Polymerase was used (Roche Cat. No. 11146165001).

Refer to Supplementary Table S15 for IDs of the sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Di Dato, V. et al. Transcriptome sequencing of three Pseudo-nitzschia species reveals comparable gene sets and the presence of Nitric Oxide Synthase genes in diatoms. Sci. Rep. 5, 12329; doi: 10.1038/srep12329 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Marie Curie FP7-PEOPLE-2011-CIG n. 293887 and was funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through Grant #2637 to the National Center for Genome Resources. The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. S.P. has been supported by an Open University PhD fellowship from Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn. G.P. has been supported by a short term fellowship for a bioinformatics internship funded by MMETSP. We thank G. Fiorito for his support, G. d’Ippolito, A. Palumbo, A. Kumar and S. D’Aniello for their advices.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.I.F, V.D.D., R.S. and M.M. conceived the experiments, M.I.F. and V.D.D. conducted the experiments and V.D.D., F.M., G.P., S.P. and R.S. analyzed the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Armbrust E. V. The life of diatoms in the world’s oceans. Nature 459, 185–192 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C. B., Behrenfeld M. J., Randerson J. T. & Falkowski P. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281, 237–240 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falciatore A., d’ Alcalà M. R., Croot P. & Bowler C. Perception of environmental signals by a marine diatom. Science 288, 2363–2366 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillard J. et al. Metabolomics enables the structure elucidation of a diatom sex pheromone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 52, 854–857 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritano C., Carotenuto Y., Miralto A., Procaccini G. & Ianora A. Copepod population-specific response to a toxic diatom diet. PloS One 7, e47262 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralto A. et al. Embryonic development in invertebrates is arrested by inhibitory compounds in diatoms. Mar. Biotechnol. N. Y. N 1, 401–402 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C. et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 456, 239–244 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust E. V. et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science 306, 79–86 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K. P., Kumar S. P. & Nair G. A. Risk assessment of the amnesic shellfish poison, domoic acid, on animals and humans. J. Environ. Biol. Acad. Environ. Biol. India 30, 319–325 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra Beltrán A., Palafox-Uribe M., Grajales-Montiel J., Cruz-Villacorta A. & Ochoa J. L. Sea bird mortality at Cabo San Lucas, Mexico: evidence that toxic diatom blooms are spreading. Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology 35, 447–453 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainer V. L. et al. Pseudo-nitzschia physiological ecology, phylogeny, toxicity, monitoring and impacts on ecosystem health. Harmful Algae 14, 271–300 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Amato A. et al. Reproductive isolation among sympatric cryptic species in marine diatoms. Protist 158, 193–207 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijano-Scheggia S. I. et al. Morphology, physiology, molecular phylogeny and sexual compatibility of the cryptic Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima complex (Bacillariophyta), including the description of P. arenysensis sp. nov. Phycologia 48, 492–509 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Orsini L. et al. Toxic Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata (Bacillariophyceae) from the Gulf of Naples: morphology, toxin analysis and phylogenetic relationships with other Pseudo-nitzschia species. Eur. J. Phycol. 37, 247–257 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Lamari N. et al. Specificity of lipoxygenase pathways supports species delineation in the marine diatom genus Pseudo-nitzschia. PloS One 8 (8), e73281 10.1371/journal.pone.0073281 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero M. V. et al. Diversity and temporal pattern of Pseudo-nitzschia species (Bacillariophyceae) through the molecular lens. Harmful Algae 42, 15–24 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino V. et al. Establishment of genetic transformation in the sexually reproducing diatoms Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata and Pseudo-nitzschia arenysensis and inheritance of the transgene. Mar. Biotechnol. NYN. 10.1007/s10126-015-9633-0 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling P. J. et al. The Marine Microbial Eukaryote Transcriptome Sequencing Project (MMETSP): illuminating the functional diversity of eukaryotic life in the oceans through transcriptome sequencing. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001889 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchia F., Basu S., Petrosino G., Salvemini M. & Sanges R. Annocript: a flexible pipeline for the annotation of transcriptomes also able to identify putative long noncoding RNAs. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv106 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Liu C.-Y., Liu H., Zhang Q. & Wang L. Protective function of nitric oxide on marine phytoplankton under abiotic stresses. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. Off. J. Nitric Oxide Soc. 33, 88–96 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Aragunde N., Foresi N. & Lamattina L. Structure diversity of nitric oxide synthases (NOS): the emergence of new forms in photosynthetic organisms. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 232 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresi N. et al. Characterization of a Nitric Oxide Synthase from the plant kingdom: NO generation from the green alga Ostreococcus tauri is light irradiance and growth phase dependent. Plant Cell Online 22, 3816–3830 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommer M. et al. Genome and low-iron response of an oceanic diatom adapted to chronic iron limitation. Genome Biol. 13, R66 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage T. J., Smith G. J., Clark A. T. & Saucedo P. N. Condensation of the isoprenoid and amino precursors in the biosynthesis of domoic acid. Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology 59, 25–33 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey U. P., Douglas D. J., Walter J. A. & Wright J. L. Biosynthesis of domoic acid by the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries. Nat. Toxins 6, 137–146 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissonneault K. R. et al. Gene expression studies for the analysis of domoic acid production in the marine diatom Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries. BMC Mol. Biol. 14, 25 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr M., Schwender J. & Polle J. E. W. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in eukaryotic phototrophs: a spotlight on algae. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 185-186, 9–22 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radakovits R. et al. Draft genome sequence and genetic transformation of the oleaginous alga Nannochloropis gaditana. Nat. Commun. 3, 686 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A. W., Huang K., Saito M. A. & Chisholm S. W. Transcriptome response of high- and low-light-adapted Prochlorococcus strains to changing iron availability. ISME J. 5, 1580–1594 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender S. J., Durkin C. A., Berthiaume C. T., Morales R. L. & Armbrust E. V. Transcriptional responses of three model diatoms to nitrate limitation of growth. Aquat. Microbiol. 1, 3 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Allen A. E. et al. Evolution and metabolic significance of the urea cycle in photosynthetic diatoms. Nature 473, 203–207 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Palma J. M., del Río L. A. & Barroso J. B. Evidence supporting the existence of L-arginine-dependent nitric oxide synthase activity in plants. New Phytol. 184, 9–14 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Hayashi M., Mano S., Nishimura M. & Barroso J. B. Peroxisomes are required for in vivo nitric oxide accumulation in the cytosol following salinity stress of Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol. 151, 2083–2094 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardi A. Cell signaling in marine diatoms. Commun. Integr. Biol. 1, 134–136 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra W. H. C. F., Gersonde R., Medlin L. & Mann D. G. The origin and evolution of the diatoms: their adaptation to a planktonic existence in Evolution of primary producers in the sea (ed. by Paul G. Falkowski, Andrews H. Knoll Amsterdam) 207–249 (Elsevier, Academic Press, 2007).

- Vardi A. et al. A diatom gene regulating nitric-oxide signaling and susceptibility to diatom-derived aldehydes. Curr. Biol. CB 18, 895–899 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B. & Kajava A. V. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 725–732 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenreich W., Bacher A., Arigoni D. & Rohdich F. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids via the non-mevalonate pathway. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 61, 1401–1426 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvejić J. H. & Rohmer M. CO2 as main carbon source for isoprenoid biosynthesis via the mevalonate-independent methylerythritol 4-phosphate route in the marine diatoms Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Nitzschia ovalis. Phytochemistry 53, 21–28 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelong A., Hégaret H., Soudant P. & Bates S. S. Pseudo-nitzschia (Bacillariophyceae) species, domoic acid and amnesic shellfish poisoning: revisiting previous paradigms. Phycologia 51, 168–216 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Guillard R. R. L. in Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals (eds Smith W. L. & Chanley M. H. ) 29–60 (Springer: US, , 1975). [Google Scholar]

- Adelfi M. G. et al. Selection and validation of reference genes for qPCR analysis in the pennate diatoms Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata and P. arenysensis. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 451, 74–81 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. & Madan A. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 9, 868–877 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseli C., Jongeneel C. V. & Bucher P. ESTScan: a program for detecting, evaluating, and reconstructing potential coding regions in EST sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. ISMB Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 138–148 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzek B. E., Huang H., McGarvey P., Mazumder R. & Wu C. H. UniRef: comprehensive and non-redundant UniProt reference clusters. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 23, 1282–1288 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A. et al. CDD: conserved domains and protein three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D348–352 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A. The ENZYME database in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 304–305 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgat A. et al. UniPathway: a resource for the exploration and annotation of metabolic pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D761–769 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G., Bradnam K. & Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 23, 1061–1067 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersey P. J. et al. Ensembl Genomes: extending Ensembl across the taxonomic space. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D563–569 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersey P. J. et al. Ensembl Genomes: an integrative resource for genome-scale data from non-vertebrate species. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D91–97 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y. & Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Vranová E., Coman D. & Gruissem W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 665–700 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 23, 2947–2948 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Stoeckert C. J. & Roos D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Mackey A. J., Vermunt J. K. & Roos D. S. Assessing performance of orthology detection strategies applied to eukaryotic genomes. PLoS ONE 2, (4): e383. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000383 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.