Abstract

RAG1 and RAG2 proteins are key components in V(D)J recombination. The core region of RAG1 is capable of catalyzing the recombination reaction; however, the biological function of non-core RAG1 remains largely unknown. Here, we show that in a murine-model carrying the RAG1 ring-finger conserved cysteine residue mutation (C325Y), V(D)J recombination was abrogated at the cleavage step, and this effect was accompanied by decreased mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3. Further analyses suggest that un-ubiquitylated histone H3 restrains RAG1 to the chromatin by interacting with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1. Our data provide evidence for a model in which ubiquitylation of histone H3 mediated by the ring-finger domain of RAG1 triggers the release of RAG1, thus allowing its transition into the cleavage phase. Collectively, our findings reveal that the non-core region of RAG1 facilitates chromosomal V(D)J recombination in a ubiquitylation-dependent pathway.

Keywords: RAG1, ubiquitylation, V(D)J recombination, histone H3

Introduction

The adaptive immune system in vertebrates relies on an enormous repertoire of antigen receptors. The variable domains of antigen receptors are encoded by extensive arrays of variety, diversity and joining (V, D, and J) gene segments flanked by conserved recombination signal sequences (RSSs)1. During the early lymphoid-specific process known as V(D)J recombination, RAG1 and RAG2 recognize and pair two RSSs based on the 12/23 rule and introduce a pair of double-strand breaks (DSB) between each RSS and its adjoining coding segment2. The non-homologous DNA end-joining pathway then rejoins the coding segments together and generates functional receptors3.

Murine RAG1 contains 1 040 amino acids, and RAG2 contains 527 amino acids. Biochemical studies have confirmed that the core regions of RAG1 (aa 384-1 008) and RAG2 (aa 1-387) are fundamental for the cleavage reaction in vitro4. Core RAG1 is capable of recognizing RSSs and can form tetramers with RAG2 in which the DDE triad is responsible for the DNA cleavage activity5. Core RAG2 contains Kelch motifs that assist RAG1 binding and cutting of the RSSs6. The plant homology domain within the RAG2 non-core region has recently been shown to bind histone H3K4Me3 and activate the recombination reaction7,8. Regarding the non-core region, especially the N-terminal region of RAG1 (aa 1-383), several conserved clusters of basic residues have been identified within residues 1-2649. This region is thought to bind to a zinc ion and associate with KPNA1 and SRP110,11,12. A recently defined WW-like domain (aa 179-205) might mediate protein-protein interactions13. Residues 265-383 of RAG1 contain a C3HC4 ring-finger domain harboring E3 ubiquitin ligase activity14. However, the roles of these domains or motifs in V(D)J recombination have not been fully elucidated.

The impaired V(D)J recombination in core RAG1 knock-in mice suggests that non-core RAG1 increases the efficiency and accuracy of recombination, yet quite a number of lymphocytes can mature, indicating that non-core RAG1 is dispensable for basic recombination activity15. Nevertheless, in some Omenn syndrome (OS) patients who carry mutations within the non-core region of RAG1 (including a conserved cysteine residue mutation in the ring-finger domain, RAG1C328Y), T and B lymphocyte are barely detected. The severe defects of lymphocyte development caused by mutations within non-core RAG1 raise the key question of how non-core RAG1 modulates the V(D)J recombination.

Previous studies of the RAG1 ring-finger domain have revealed that the loss of E3 ubiquitin ligase activity correlates with decreased V(D)J recombination of episomal substrates16,17. Histone H3 was recently defined as a ubiquitylation substrate of the RAG1 ring-finger domain, suggesting a chromatin-mediated regulation of V(D)J recombination18,19. Whether and how RAG1's E3 ubiquitin ligase activity participates in V(D)J recombination in vivo is unknown.

In this study, we constructed a murine model (RAG1KI/KI mice) carrying the RAG1C325Y mutation that corresponds to the RAG1C328Y mutation in OS patients. We found that V(D)J recombination was severely impaired at the cleavage stage, and this was accompanied by decreased mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3 in RAG1KI/KI mice. When we compared the cleavage abilities of RAG1C325Y and wild-type RAG1 using different substrates, we found that RAG1C325Y was specifically unable to catalyze the recombination of chromatinized substrates. Further analyses suggest that histone H3 recruits RAG1 by interacting with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 but subsequently restrains its cleavage activity toward RSSs. Our data provide evidence for a model in which ubiquitylation of histone H3 mediated by the ring-finger domain triggers the release of RAG1, allowing its transition into the cleavage phase. Altogether, ubiquitylation of histone H3 mediated by the RAG1 ring-finger domain is required for RAG1 to catalyze chromosomal V(D)J recombination.

Results

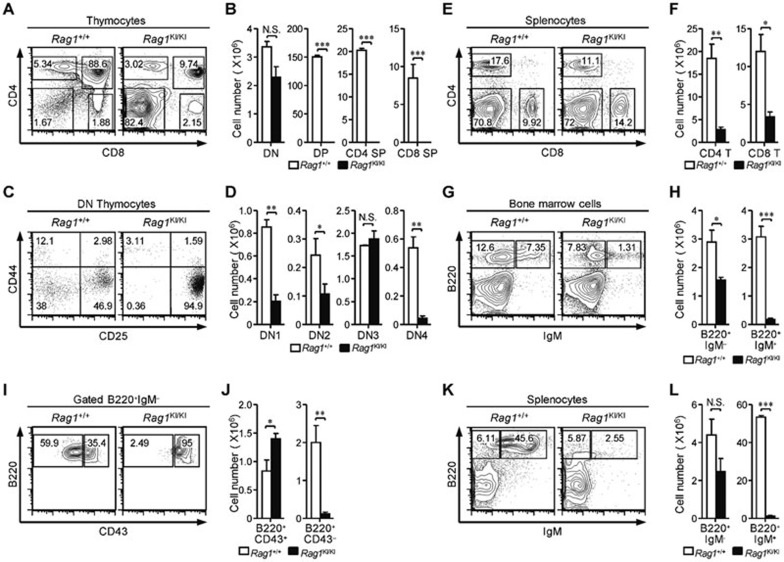

T and B lymphocyte development is severely blocked in RAG1KI/KI mice

To investigate the role of the N terminal region of RAG1 in V(D)J recombination, we constructed a murine model carrying the RAG1C325Y mutation (Supplementary information, Figure S1A-S1C). In agreement with the immune deficiency of OS patients, a severe defect in early T lymphocyte development was observed in the RAG1KI/KI mice. Thymic cellularity was drastically reduced with an obvious arrest of thymocyte differentiation at the CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN) stage (Figure 1A and 1B). The expression profile of CD44 and CD25 revealed that the DN thymocytes accumulated at the DN3 stage with a relative depletion of the DN4 subset (Figure 1C and 1D). The numbers of CD4, CD8 and γδ T cells were severely reduced in the spleen (Figure 1E and 1F; Supplementary information, Figure S1D). A deficiency in early B cell differentiation was also detected in the bone marrow (Figure 1G and 1H). The majority of early B cells stopped at the Pro-B stage (Figure 1I and 1J). Mature B lymphocytes were barely detected in the spleen (Figure 1K and 1L), whereas macrophage and NK cell development in the mutant mice was comparable to that of their wild-type littermates (Supplementary information, Figure S1D). Altogether, we found that the RAG1KI/KI mice exhibited severe defects in early T and B lymphocyte differentiation.

Figure 1.

Impaired T and B lymphocyte development in RAG1KI/KI mice. (A, B) Thymocyte development is arrested at the DN stage. Flow cytometric analysis of thymocytes, from the indicated mice, stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. The cell number of indicated thymocyte subsets is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3; ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test; N.S., no significance). (C, D) Thymocytes are primarily blocked at DN3 stage. Lin− cells were gated and analyzed for CD44 and CD25 expression. The cell number of the DN subsets is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test; N.S., no significance). (E, F) Mature T lymphocytes are reduced in the periphery. Splenocytes were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. The number of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes in spleen is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). (G, H) Early B cell development is impaired. Cells isolated from femurs were stained with anti-B220 and anti-IgM antibodies. The number of indicated B cell subsets in the bone marrow is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 4; ***P < 0.001 and *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). (I, J) B220+IgM− cells were gated and analyzed for CD43 expression. The number of pro-B-cell and pre-B-cell subsets are shown (mean ± SEM; n = 4; **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). (K, L) Mature B cells were barely detected in the spleen. Splenocytes were stained with anti-B220 and anti-IgM antibodies. The number of indicated B-cell subsets in spleen is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 4; ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test; N.S., no significance). All mice were analyzed at 4-5 wk of age.

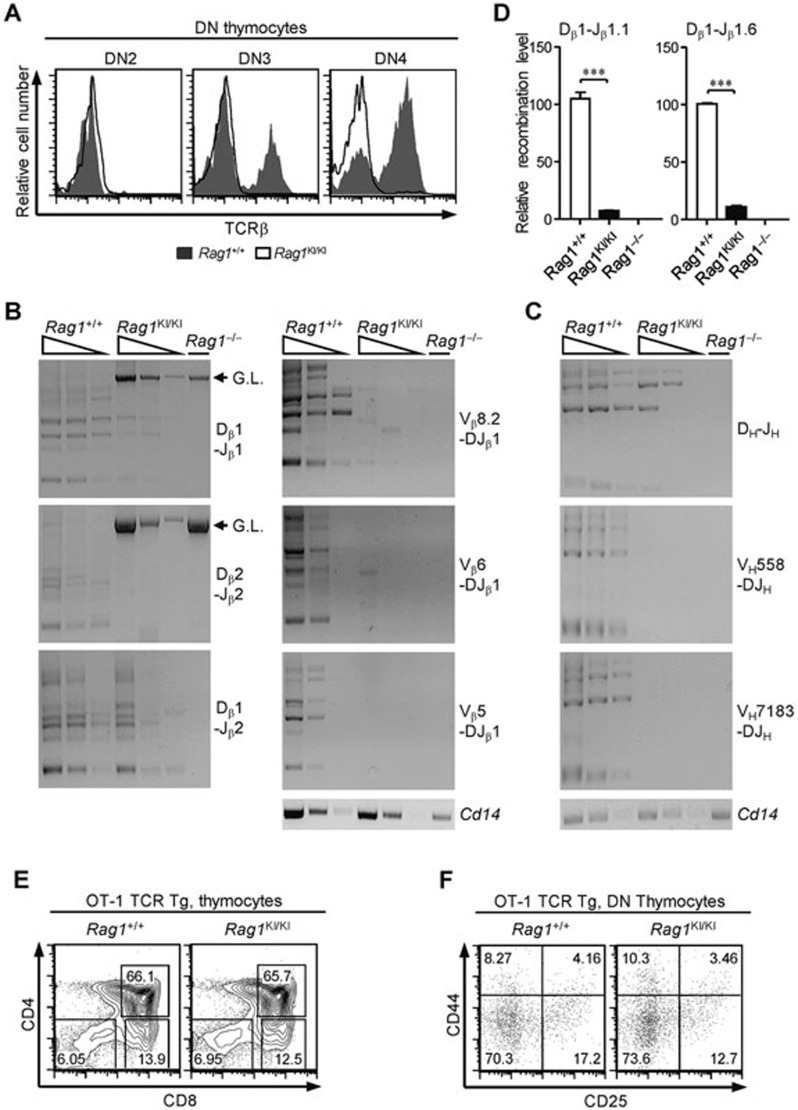

Deficiency in RAG1KI/KI mice is due to diminished V(D)J rearrangement

Given that the development of thymocytes stopped at the DN3 stage and the B-cell development stopped at the Pro-B stage, we inferred that RAG1C325Y failed to catalyze V(D)J recombination in vivo. Thus we assessed the expression of the TCRβ chain and found that the proportions of DN3 and DN4 thymocytes expressing TCRβ dropped dramatically in the RAG1KI/KI mice (Figure 2A). Next, we examined the recombination products from RAG1KI/KI mice. After genomic DNA was prepared from DN3 thymocytes and Pro-B cells, we performed PCR analysis to measure the joints of the Tcrb and Igh rearrangement. As expected, the recombination products of Dβ-Jβ were markedly lower in the RAG1KI/KI mice than in their wild-type littermates (Figure 2B). The complete Vβ-DJβ assembly was barely detected in the mutant mice (Figure 2B). The levels of DH-JH and VH-DJH rearrangement also decreased in Pro-B cells (Figure 2C). The levels of endogenous Dβ1-Jβ1.6 coding joint and Dβ1-Jβ1.1 signal joint in RAG1KI/KI mice were reduced to one-tenth of that detected in wild-type mice as shown by real-time PCR analysis (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Impaired Tcrb and Igh rearrangement in RAG1KI/KI mice. (A) The TCRβ expression level dropped markedly. Overlay of the TCRβ intracellular expression in the indicated DN subsets (solid line, RAG1KI/KI mice; shaded in gray, WT littermates). The results are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Tcrb rearrangement is reduced. Semi-quantitative PCR to detect Dβ-Jβ rearrangement or Vβ-DJβ1 recombination in DN3 thymocytes (CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25+) sorted from RAG1KI/KI mice, their WT littermates and RAG1−/− mice. Below, amplification of a Cd14 fragment (input control). G.L., germline fragment. PCR amplification was performed on serial fivefold dilutions of genomic DNA. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Igh rearrangement is impaired. Semi-quantitative PCR of DH-JH rearrangement or VH-DJH recombination in Pro-B cells (B220+IgM−CD43high) sorted from the indicated mice. Below, amplification of a Cd14 fragment (input control). PCR amplification was performed on serial five-fold dilutions of genomic DNA. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Quantification of the rearrangement products. Real-time PCR analysis quantification of the Dβ1-Jβ1.1 signal joints and Dβ1-Jβ1.6 coding joints (mean ± SEM; n = 3; ***P < 0.001 by Student's t-test). (E) Flow cytometric analysis of thymocytes from the indicated mice stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (F) CD4−CD8− cells were gated and analyzed for CD44 and CD25 expression. The results are representative of two independent experiments. All recombination products amplified by PCR were confirmed by sequencing.

To exclude the possibility that the impaired lymphocyte development was independent of V(D)J recombination, the OT-1 TCR transgene was introduced into the knock-in mice. Thymocyte differentiation was rescued by the ectopic TCR expression (Figure 2E and 2F). Taken together, our data showed that the murine RAG1C325Y failed to mediate V(D)J recombination in vivo, leading to abrogated lymphocyte development.

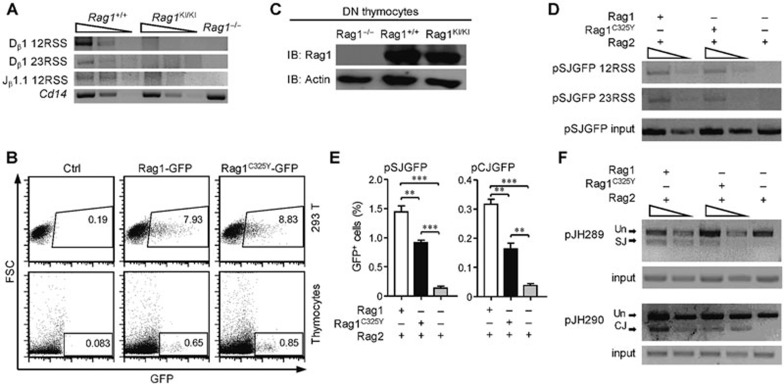

RAG1C325Y largely retains DNA endonuclease activity toward episomal substrates

The V(D)J recombination process is generally divided into a cleavage phase and a joining phase20. Thus we used LM-PCR to assess the RSS breaks in DN3 thymocytes. Contrary to the previous expectation18, we were unable to detect any accumulation of signal ends in RAG1KI/KI mice (Figure 3A). Collectively, the diminished level of signal ends accompanied by the considerable amount of remaining Dβ-Jβ germline bands (Figure 2B) suggests that V(D)J recombination stops at the cleavage phase in RAG1KI/KI mice.

Figure 3.

RAG1C325Y is unable to catalyze chromosomal substrates. (A) V(D)J recombination stopped at the cleavage phase in RAG1KI/KI mice. Detection of the signal ends of 5′ Dβ1, 3′ Dβ1 and 5′ Jβ1.1 in DN3 thymocytes sorted from indicated mice by LM-PCR. Below, amplification of a Cd14 fragment (input control). PCR amplification was performed on serial fivefold dilutions of genomic DNA ligated to a BW-linker. (B) RAGC325Y exhibited a normal expression level compared to WT RAG1 in vitro. RAG1-GFP and RAGC325Y-GFP were transiently transfected into thymocytes and HEK-293T cells. After 12 h, GFP expression and intensity was analyzed by FACS. (C) RAGC325Y exhibited a normal expression level compared to WT RAG1 in vivo. Western blot analysis of RAG1 and RAG1C325Y expression in DN3 thymocytes sorted from indicated mice. β-actin expression was assessed as a loading control. (D) LM-PCR analysis of the signal end of pSJGFP generated in HEK-293T cells. PCR amplification was performed on serial fivefold dilutions of template DNA. Control PCR amplification of a non-rearranging locus on pSJGFP was performed to normalize the input DNA. SE, signal end. (E) Fluorescent reporter substrates recombination assay in HEK-293T cells. The GFP level was measured by flow cytometric analysis. The percentages of GFP+ cells are shown (means ± SD; n = 3; ***P < 0.001 and **P < 0.01 by Student's t-test). (F) The recombination products of pJH289 and pJH290 in HEK-293T were analyzed by PCR. Un, unrearranged; CJ, coding joint; SJ, signal joint. PCR amplification was performed on serial three-fold dilutions of template DNA. Control PCR amplification of a non-rearranging locus on pJH289 and pJH290 was performed to normalize the input DNA. All results are representative of three independent experiments.

Given the cleavage deficiency observed in RAG1KI/KI mice, we wondered whether the ring-finger domain mutation influenced the expression level of RAG1. Therefore, we fused GFP to the C-termini of RAG1 and RAG1C325Y and introduced these constructs into thymocytes and HEK-293T cells by transient transfection. FACS analysis showed that the two constructs showed similar expression levels and fluorescence intensity in thymocytes and in HEK-293T cells (Figure 3B). Additionally, similar level of protein expression in vivo was detected by western blots of WT and RAG1KI/KI DN3 thymocytes (Figure 3C). We then questioned whether the ring-finger mutation interfered with RAG1's nuclease activity. Intriguingly, in the recombination experiments we performed with HEK-293T cells, RAG1 and RAG1C325Y generated comparable levels of DNA DSB in the episomal substrates (Figure 3D). The formation of recombination products catalyzed by RAG1C325Y was reduced to 50% of that catalyzed by RAG1 (Figure 3E and 3F). Thus the difference in the recombination activity between RAG1 and RAG1C325Y was smaller toward episomal substrates. As reported previously, the transiently tansfected episomal substrates consist of un-chromatinized and chromatinized DNA21,22. Taken together, these results suggest that the chromatin might be a decisive factor obstructing RAG1C325Y recombination activity in vivo.

We also analyzed the sequences of Dβ-Jβ recombination products and found that the signal joints from the mutant mice were similar to those from wild-type mice; however, certain differences between the coding joints were detected (Supplementary information, Figure S2A-S2C). These results were reminiscent of that of the core RAG1 knock-in study23.

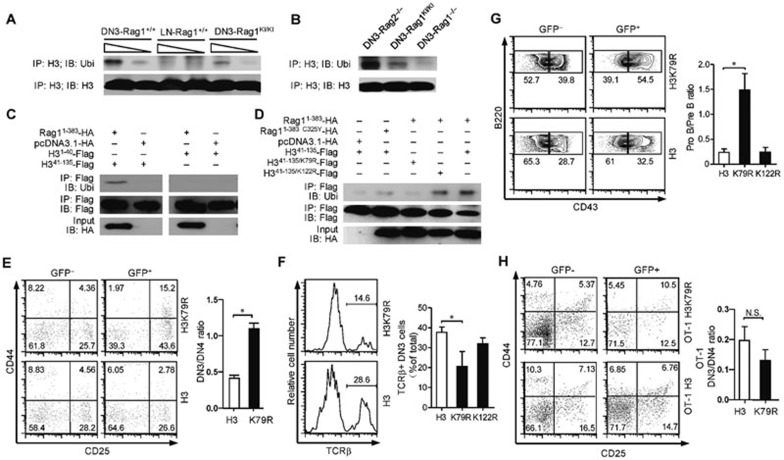

V(D)J recombination impairment in RAG1KI/KI mice correlates with decreased mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3

The C325Y mutation in the RAG1 ring-finger domain is known to abolish its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity toward histone H318,19. These observations and our results, strongly suggest that the ring finger's E3 activity regulates V(D)J recombination through a chromatin-mediated mechanism. Thus, we hypothesized that failure to ubiquitylate histone H3 may underlie the severe V(D)J recombination impairment observed in RAG1KI/KI mice.

As shown in Figure 4A, histone H3 was less mono-ubiquitylated in RAG1KI/KI DN3 thymocytes compared to wild type DN3 thymocytes. A lower level of mono-ubiquitylated histone H3 was detected in the RAG1KI/KI thymocytes than in the RAG2 knock-out thymocytes (Figure 4B), suggesting that the histone H3 mono-ubiquitylation is cleavage-independent. We then performed a deletion analysis of histone H3 and found that the N-terminal region of RAG1 preferentially mono-ubiquitylated histone H3 within the region between residues 41 and 135 (Figure 4C). This region of histone H3 contains two conserved lysine residues (K79, K122) that have been reported to be ubiquitylated by RAG1 in vitro19. Further substitution of lysine with arginine indicated that lysine 79 is most likely the ubiquitylation target (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Correlation between decreased mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3 and V(D)J impairment in RAG1KI/KI mice. (A, B) Histone H3 was less mono-ubiquitylated in RAG1KI/KI mice. Lysates of the indicated DN3 thymocytes and CD4 T cells in the lymph node were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-histone H3 antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody. The results are representative of three independent experiments. DN3,DN3 thymocytes. LN, CD4 T cells in the lymph node. (C, D) N-terminal RAG1 catalyzed the mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3 on lysine 79 in HEK-293T cells. The indicated constructs were co-transfected with N-terminal RAG1 into HEK-293T cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG M2 gel followed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (E) Overexpression of histone H3 K79R partially impairs DN3 thymocyte development. Flow cytometric analysis of DN thymocytes transfected with indicated mutant histone H3. CD4−CD8− cells were gated and analyzed for CD44 and CD25 expression. The results are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SEM; n = 3; *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). (F) Overexpression of histone H3 K79R reduces TCRβ expression in DN3 thymocytes. TCRβ intracellular expression in the indicated DN3 thymocytes (mean ± SEM; n = 4; *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). (G) Overexpression of histone H3 K79R partially blocks early B cells at the Pro-B stage. Flow cytometric analysis of the development of early B cells transfected with mutant histone H3 (mean ± SEM; n = 4; *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). (H) Overexpression of histone H3 K79R does not arrest OT-1 thymocyte differentiation. Flow cytometric analysis of OT-1 thymocytes transfected with indicated mutant histone H3. Lin− cells were gated and analyzed for CD44 and CD25 expression. The results are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SEM; n = 3; by Student's t-test; N.S., no significance).

We next performed bone marrow transfer experiments to overexpress mutant histone H3 in which lysine 79 had been replaced with arginine in otherwise wild-type bone marrow cells. We found that overexpression of H3 K79R led to a partial arrest of lymphocyte development (Figure 4E–4G; Supplementary information, Figure S3). To exclude the possibility that the impaired lymphocyte development was independent of V(D)J recombination, we also performed bone marrow transfer experiments to overexpress mutant histone H3 in OT-1 TCR transgenic bone marrow cells. Overexpression of the H3 mutant no longer hindered OT-1 thymocyte differentiation (Figure 4H). Taken together, our results suggest that the decreased mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3 is an important reason for the observed V(D)J recombination impairment in RAG1KI/KI mice.

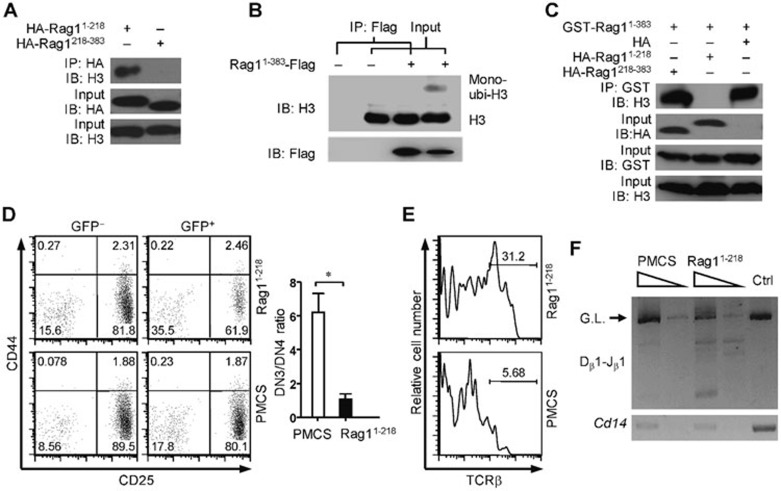

Mono-ubiquitylation of histone H3 releases RAG1 into the cleavage phase

To demonstrate the link between RAG1-mediated ubiquitylation of histone H3 and chromosomal RSS cleavage, we first analyzed the association between RAG1 and histone H3. Histone H3 is reported to specifically interact with the N terminal region of RAG118. By co-immunoprecipitation, we found the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 mediated interactions with histone H3 (Figure 5A). We further compared the association with the N-terminal region of RAG1 between histone H3 and mono-ubiquitylated histone H3. Intriguingly, the N-terminal region of RAG1 preferentially interacted with un-ubiquitylated histone H3 in HEK-293T cells (Figure 5B). Based on these results, we speculate that histone H3 may spatially immobilize RAG1 by associating with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 (RAG11-218), and ubiquitylation of histone H3 mediated by the ring-finger domain triggers the release of RAG1 from the nucleosomes. It is possible that the failure to ubiquitylate histone H3 could restrain RAG1C325Y at the nucleosomes, leading to impaired V(D)J recombination in RAG1KI/KI mice. We wondered whether the impaired V(D)J recombination in RAG1KI/KI mice could be rescued once RAG1 is dissociated from histone H3. By co-immunoprecipitation, we found that overexpression of RAG11-218 abrogated the association between the N-terminal region of RAG1 and histone H3 (Figure 5C). We then used bone marrow transfer to overexpress the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 in bone marrow cells from RAG1KI/KI mice. A moderate restoration of thymocyte differentiation was observed with increased Tcrb rearrangement (Figure 5D–5F; Supplementary information, Figure S4), supporting that releasing RAG1 from histone H3 initiates chromosomal V(D)J recombination.

Figure 5.

Shielding RAG1C325Y from histone H3 partially restores V(D)J recombination in RAG1KI/KI mice. (A) Residues between 1-218 within N terminal RAG1 interact with histone H3. Constructs encoding the indicated RAG1 were transfected into HEK-293T cells. The proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and immunoblotted with anti-histone H3 antibody. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (B) N-terminal RAG1 preferentially binds to un-ubiquitylated histone H3. Constructs encoding the indicated RAG1 sequences were transfected into HEK-293T cells. Proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 gel followed by immunoblotting with an anti-histone H3 antibody. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (C) Overexpressing the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 abrogates the association between N-terminal RAG1 and histone H3. Combined constructs were co-transfected into HEK-293T cells. Proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with GST-sepharose and immunoblotted with anti-histone H3 antibody. The results are representative of two independent experiments. (D) Abrogating the association between N-terminal RAG1 and histone H3 in RAG1KI/KI mice partially restores DN3 thymocyte differentiation. Flow cytometric analysis of the development of RAG1KI/KI DN thymocytes transfected with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1. Lin− cells were gated and analyzed for CD44 and CD25 expression (mean ± SEM; n = 3; *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test). RAG11-218, pMCs-RAG11-218-IRES-GFP; PMCS, pMCs-IRES-GFP vector. (E) Abrogating the association between N-terminal RAG1 and histone H3 in RAG1KI/KI mice partially restores TCRβ expression. TCRβ intracellular expression in the indicated transduced RAG1KI/KI DN3 thymocytes. (F) Abrogating the association between N-terminal RAG1 and histone H3 in RAG1KI/KI mice partially restores Tcrb rearrangement. Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of Dβ1-to-Jβ1 rearrangement in transduced RAG1KI/KI DN3 thymocytes (GFP+CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25+). Below, amplification of a Cd14 fragment (input control). G.L., germline fragment. PCR amplification was performed on serial five-fold dilutions of genomic DNA. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

Discussion

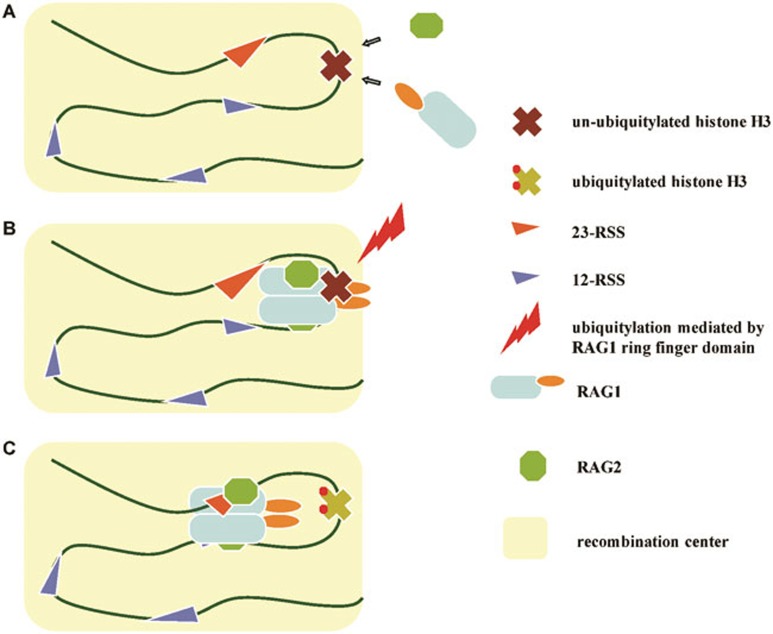

In this study, we report that V(D)J recombination is abrogated at the initiation step, correlating with decreased histone H3 mono-ubiquitylation in RAG1C325Y knock-in mice. Our results provide a ring-finger domain-dependent model in which histone H3 recruits and restrains RAG1 at the recombination center by associating with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1. Ubiquitylation of histone H3 mediated by the RAG1 ring-finger domain then triggers the transition of RAG1 into the cleavage phase (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Model showing how the N-terminal region of RAG1 modulates V(D)J recombination. (A) The interaction between the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 and histone H3 recruits RAG1 to the recombination center. (B) Un-ubiquitylated histone H3 restrains RAG1 from entering the cleavage phase. (C) The ring-finger domain triggers the release of RAG1 by catalyzing the ubiquitylation of histone H3.

We observed a decrease in bulk histone H3 ubiquitylation in RAG1C325Y DN3 thymocytes compared to wild type DN3 thymocytes (Figure 4A and 4B). Previous study has reported that accompanied by RAG2, RAG1 protein binding occurs in a highly focal manner to a small region of active chromatin encompassing antigen receptor gene segments24. It is reasonable to speculate that the RAG1-H3 interaction and H3 ubiquitylation occur within the “recombination center” during V(D)J recombination. However, we could not rule out the possibility that RAG1 might mediate histone H3 ubiquitylation outside the recombination center, which needs further investigation in the future. During the early stage of T and B lymphocyte development, the chromosomal loci of antigen receptor genes undergo reversible chromatin changes, including histone modifications and DNA hypomethylation, etc.25,26. Series of remodeling changes not only ensure the loci are open and accessible but also are involved in recruiting RAG2 via (H3K4Me3) and activating V(D)J recombination27,28. An additional aspect suggested by our results is that un-ubiquitylated histone H3 at the recombination center recruits RAG1 by associating with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1 (Figure 6A), thus explaining the attenuated recombination efficiency in the core RAG1 knock-in mice15 and the recombination deficiency caused by NΔ13-135 RAG129. Our study provides an explanation for how full-length RAG1 locates to the recombination center. A recent study identified acetylated and phosphorylated histone H3.3 in Pro-B cells as a substrate for the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of RAG119. The detailed mechanisms by which histones recruit RAG1 deserve further exploration.

The exact role of the non-core region of RAG1 during V(D)J recombination has been an open question for decades20. Biochemical studies have revealed a subsidiary role of the non-core, as core RAG1 is able to catalyze recombination in vitro4. The observation that V(D)J recombination in core RAG1 knock-in mice exhibits a lower efficiency and accuracy suggests that the non-core region of RAG1 acts as a positive regulator23,29. Nevertheless, studies of core-RAG1 knock-in mice cannot determine the exact mechanism of non-core RAG1. Based on the results from our RAG1KI/KI mice, the function of N-terminal RAG1 should be considered from two aspects. The correlation between the severe impairment of V(D)J recombination and the decreased ubiquitylation of histone H3 in vivo suggests that un-ubiquitylated histone H3 inhibits recombination by associating with the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1. After RAG1 is loaded at the recombination center, multiple encounters with RSSs require the confinement of RAG1 to prevent any nonspecific cleavage until a stable paired (synaptic) complex assembles20,30. It is plausible to speculate that the constitutive interaction between histone H3 and RAG1 prevents RAG1 from cleaving the RSSs (Figure 6B). The ring-finger domain's E3 activity towards histone H3 serves to release RAG1 to initiate the cleavage step (Figure 6C). Therefore, when we blocked the interaction between RAG1 and histone H3 in RAG1C325Y knock-in mice, we observed elevated V(D)J recombination in thymocytes. This partial rescue suggests that the deficiency of RAG1C325Y in vivo can be attributed to the constitutive interaction with un-ubiquitylated histones. Nucleosome structure and chromatin packaging are already known to sequester RSSs from the RAGs31. Our findings suggest a further hierarchy of RSS protection provided by the chromatin (most likely remodeled) and the N-terminal 218 amino acids of RAG1. The ring-finger domain's E3 activity prepares full-length RAG1 for the initiation of cleavage via the ubiquitylation of histone H3. Our results suggest that ubiquitylation of histone H3 spatially releases RAG1, however, we could not rule out the possibility that this transition into cleavage may also involve a conformational change in RAG116. The spatial release and an active conformation could be triggered simultaneously, and they are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

A previous study reported that after 48 h of co-transfection with episomal substrates, RAG1 containing the ring-domain mutation generates more signal ends than wild-type RAG118. When we shifted the time point to 24 h after the co-transfection, we found a comparable level of signal ends and decreased joints generated by RAG1C325Y compared to wild-type RAG1. Collectively, these data suggest that RAG1C325Y might be somewhat defective in the joining phase. A previous study found that although the V(D)J recombination mediated by some RAG1 N-terminal mutants is impaired, such impairment can be partially rescued by higher expression of the mutants29. That RAG1 and RAG1C325Y exhibited comparable cleavage ability in HEK-293T cells (Figure 3D) might as well be due to their high expression levels. We could not rule out the possibility that RAG1C325Y might be partially defective in the cleavage of episomal substrates.

Our results provide a model that chromatin functions in a “recruit”, “restrain” and “release” pattern prior to the initiation of V(D)J recombination. This new perspective regarding the relationship between non-core RAG1 and nucleosomes enriches our understanding of V(D)J recombination. Although the RAG1KI/KI mice showed a normal appearance at birth, the majority of them after the age of 8 weeks gradually began to exhibit hair loss, erythroderma and colitis-autoimmune phenotypes mimicking OS. Preliminary analysis showed that peripheral T cells were hyperactive in these mice (data not shown). Further study of cellular mechanisms such as T cell tolerance and expansion in these mice will enhance our understanding of OS pathophysiology.

Materials and Methods

Mice

RAG1KI/KI mice were generated by gene targeting. In brief, a targeting vector containing a C325Y mutation in a Kpn1/BamH1 fragment (covering the Rag1 coding region), a diphtheria toxin A negative selection cassette and a Neo-positive cassette was introduced into embryonic stem (ES) cells by electroporation. Targeted ES clones were first identified by PCR with a forward primer located upstream of the 5′ homologous arm and a reverse primer downstream of the Neo cassette. PCR products were further sequenced to verify the existence of mutation site. Positive clones were next analyzed by Southern blot using a probe located downstream of the 3′ homologous arm (a 1 500-bp fragment). The selected ES clone was then microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to produce chimeric mice. Male chimeras were bred to C57BL/6 female mice to generate heterozygous progeny mice. By crossing with CmvCre mice, the floxed Neo cassette was removed.

OT-1 TCR transgenic mice, RAG1−/− mice and RAG2−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities at the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center. All mice were genotyped using PCR before experimentation. All animal experiments were approved by The Institutional Animal Use Committee of the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Antibodies and reagents

For the flow cytometry analysis, anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8a (53-6.7), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD3e (145-2C11), anti-CD43 (S7), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-TCRβ (H57), anti-Ter119 (TER-119), anti-Gr-1(RB6-8C5), anti-IgM (R6-60.2) and anti-CD25 (PC61) were purchased from BD Biosciences.

In IP and co-IP assays, anti-FLAG (M2) mAb (F3165), and the affinity gel (A2220) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, anti-HA (sc-805) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, the glutathione sepharose 4B (27-4574-01) was purchased from GE and the anti-histone H3 (ab1791) was purchased from Abcam.

For western blots, the anti-RAG1 (sc-363, sc-5599), anti-GST (sc-138) and anti-ubiquitin (sc-166553) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. An additional anti-ubiquitin (ab134953) antibody was purchased from Abcam.

The 2× Taq Master Mix used in PCR was purchased from Vazyme, and the SYBER Green Master Mix used in the real-time PCR was purchased from Toyobo.

Iodoacetamide, N-ethylmaleimide and MG-132 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Detection of endogenous rearrangement by PCR

A single-cell suspension was prepared, and the surface was stained as previously described32,33. DN3 cells (CD4−CD8−CD44−CD25+) and Pro-B cells (B220+IgM−CD43high) were sorted by a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences). Genomic DNA was prepared as previously described32. The Tcrb recombination products were detected as previously described32, as were the Igh recombination products15. LM-PCR was carried out as previously described15.

To quantify the Dβ1-Jβ1.6 coding joints and Dβ1-Jβ1.1 signal joints, DN3 genomic DNA was digested with EcoRI and EcoRV and then recovered. Cd14 was used as an internal control. The junction levels relative to that of the first control sample (given a value of 100) were normalized by the mean value of the control group from three independent experiments. The following primer pairs were used: Dβ1-Jβ1.6-CJ: 5′-AGAAGGGCGGATACAAGA-3 and 5′-AGATGGGAAGGGACGACT-3′ Dβ1-Jβ1.1-SJ: 5′-GAGGGAATCTACCATGTTTGAC-3′ and 5′-TTATGGACGTTGGCAGAAGAGGAT-3′ and Cd14: 5′-CCTAGTCGGATTCTATTCGGAGCC-3′ and 5′-AACTTGGAGGGTCGGGAACTTG-3′.

Recombination assays in HEK-293T cells

Recombination substrate plasmids (pJH289 or pJH290, 0.7 μg), N-FLAG-RAG1-pcDNA3.1 or N-FLAG-RAG1C325Y-pcDNA3.1 (1.5 μg) and pEBG-RAG2 (1.5 μg) were co-transfected into 293T cells34. After 24 h, the transfected DNA was recovered by alkaline lysis. To analyze the recombination products, the recovered DNA was amplified by 25 cycles of PCR. All of the recombination products amplified by PCR were confirmed by sequencing. The following primer pairs were used: for pJH289-SJ and pJH290-CJ, 5′-CCCCAGGCTTTACACTTT-3′ and 5′-CCGTCTTTCATTGCCATAC-3′ for pJH289 and pJH290 input, 5′-TCTTTATAGTCCTGTCGGGTTT-3′ and 5′-GCGGTAATACGGTTATCCAC-3.

The recombination substrate plasmids (pSJGFP or pCJGFP, 0.7 μg), N-FLAG-RAG1-pcDNA3.1 or N-FLAG-RAG1C325Y-pcDNA3.1 (1.5 μg) and pEBG-RAG2 (1.5 μg) were co-transfected into 293T cells35. After 24 h, the signal joints and coding joints were assessed by determining the ratios of cells expressing GFP.

To analyze the signal end, the recovered DNA was ligated with a BW linker (BW1: 5′-GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTC-3′, BW2: 5′-GAATTCAGATC-3′).

The primer pairs used were as follows: for the 12RSS signal end, 5′-CCGGGAGATCTGAATTCCAC-3′ and 5′-CCCCAGGCTTTACACTTT-3′ for the 23 RSS signal end, 5′-CCGGGAGATCTGAATTCCAC-3′ and 5′-CCGTCTTTCATTGCCATAC-3′.

Cell lines and transient transfection

HEK-293T cells and Plat-E cells were transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation and maintained in DMEM. Freshly isolated thymocytes were electroporated and maintained in DMEM (20% FBS and 100 U/ml IL-7).

Anti-histone H3 immunoprecipitation

Iodoacetamide (final concentration 10 mM), N-ethylmaleimide (final concentration 10 mM), MG123 (final concentration 20 mM) and protease inhibitor cocktail were added into the immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (m/v) SDS and 5% (v/v) glycerol) before use. For in vivo IP, 1 × 106 fresh DN3 cells were sorted from the indicated mice and lysed on ice. After sonication and precipitation, the supernatant was gently agitated at 4 °C with anti- histone H3 (pre-linked with protein A/G) for 5 h. For the HEK-293T cell IP, the supernatant of 1 × 107 transfected HEK-293T cells was gently agitated with anti-FLAG M2 gel at 4 °C for 5 h. The precipitates were washed three times with immunoprecipitation buffer and eluted in SDS loading buffer.

Co-immunoprecipitation and GST precipitation assay

For the co-immunoprecipitation and GST precipitation assays, 1 × 107 HEK-293T cells were lysed and sonicated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 5% (v/v) glycerol) with the protease inhibitors, iodoacetamide (final concentration 10 mM), N-ethylmaleimide (final concentration 10 mM) and MG123 (final concentration 20 mM) added to preserve the ubiquitylated proteins in the lysis buffer. After precipitation, the supernatant was gently agitated with anti-HA antibody (pre-linked with proteinA/G), anti-FLAG M2 gel or GST-sepharose at 4 °C for 12 h. The precipitates were washed three times with lysis buffer and eluted in SDS loading buffer.

Retroviral bone marrow transfer

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer (based on pMCs-IRES-GFP vector) was performed as previously described33. Bone marrow cells were isolated from the indicated mice 5 day after the injection of 5-fluorouracil and maintained in pre-stimulation medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml rmSCF, 6 ng/ml rmIL-3 and 10 ng/ml rmIL-6 (PeproTech) for 18-24 h. After the retrovirus infection33,36, 1 × 106 bone marrow cells were injected into each 750 cGy-irradiated recipient. After 3-4 week, thymocytes and bone marrow cells were isolated from the recipients and analyzed to assess T and B lymphocyte differentiation.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The results were analyzed by Student's t-test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs David G Schatz, David Roth, Stephen Desiderio and Martin Gellert for providing recombination plasmids. We are grateful to our colleagues H Chen for animal husbandry and W Bian for cell sorting. This work was supported by grants from National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB835300 and 2012CB518700), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270936 and 81261120380) and Shanghai Municipal Government (12XD1405800).

Glossary

- V, D, and J

variety, diversity and joining

- RSSs

recombination signal sequences

- DSB

double-strand breaks

- OS

Omenn syndrome

- DN

double-negative

- ES

embryonic stem

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Generation of RAG1KI/KI mice.

Comparison of recombination products between RAG1KI/KI and RAG1+/+ mice.

Two additional repeats of the bone marrow transfer experiment in Figure 4.

Two additional repeats of the bone marrow transfer experiment in Figure 5.

References

- 1Alt FW, Oltz EM, Young F, et al. Vdj Recombination. Immunol Today 1992; 13:306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Bassing CH, Swat W, Alt FW. The mechanism and regulation of chromosomal V(D)J recombination. Cell 2002; 109:S45–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Cui XP, Meek K. Linking double-stranded DNA breaks to the recombination activating gene complex directs repair to the nonhomologous end-joining pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:17046–17051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Aidinis V, Dias DC, Gomez CA, et al. Definition of minimal domains of interaction within the recombination-activating genes 1 and 2 recombinase complex. J Immunol 2000; 164:5826–5832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Fugmann SD, Lee AI, Shockett PE, et al. The rag proteins and V(D)J recombination: complexes, ends, and transposition. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18:495–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Callebaut I, Mornon JP. The V(D)J recombination activating protein RAG2 consists of a six-bladed propeller and a PHD fingerlike domain, as revealed by sequence analysis. Cell Mol Life Sci 1998; 54:880–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7West KL, Singha NC, De Ioannes P, et al. A direct interaction between the RAG2 C terminus and the core histones is required for efficient V(D)J recombination. Immunity 2005; 23:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Matthews AG, Kuo AJ, Ramón-Maiques S, et al. RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination. Nature 2007; 450:1106–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Spanopoulou E, Cortes P, Shih C, et al. Localization, interaction, and RNA binding properties of the V(D)J recombination-activating proteins RAG1 and RAG2. Immunity 1995; 3:715–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Rodgers KK, Bu ZM, Fleming KG, et al. A zinc-binding domain involved in the dimerization of RAG1. J Mol Biol 1996; 260:70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Cortes P, Ye ZS, Baltimore D. Rag-1 interacts with the repeated amino-acid motif of the human homolog of the yeast protein Srp1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91:7633–7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Simkus C, Makiya M, Jones JM. Karyopherin alpha 1 is a putative substrate of the RAG1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol Immunol 2009; 46:1319–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Maitra R, Sadofsky MJ. A WW-like module in the RAG1 N-terminal domain contributes to previously unidentified proteinprotein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:3301–3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Yurchenko V, Xue Z, Sadofsky M. The RAG1 N-terminal domain is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Gene Dev 2003; 17:581–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Dudley DD, Sekiguchi J, Zhu CM, et al. Impaired V(D)J recombination and lymphocyte development in core RAG1-expressing mice. J Exp Med 2003; 198:1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Simkus C, Anand P, Bhattacharyya A, et al. Biochemical and folding defects in a RAG1 variant associated with Omenn syndrome. J Immunol 2007; 179:8332–8340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Simkus C, Bhattacharyya A, Zhou M, et al. Correlation between recombinase activating gene 1 ubiquitin ligase activity and V(D)J recombination. Immunology 2009; 128:206–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Grazini U, Zanardi F, Citterio E, et al. The RING domain of RAG1 ubiquitylates histone H3: a novel activity in chromatin-mediated regulation of V(D)J joining. Mol Cell 2010; 37:282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Jones JM, Bhattacharyya A, Simkus C, et al. The RAG1 V(D)J recombinase/ubiquitin ligase promotes ubiquitylation of acetylated, phosphorylated histone 3.3. Immunol Lett 2011; 136:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Schatz DG, Ji YH. Recombination centres and the orchestration of V(D)J recombination. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Mymryk JS, Fryer CJ, Jung LA, et al. Analysis of chromatin structure in vivo. Methods 1997; 12:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Vaughan EE, DeGiulio JV, Dean DA. Intracellular trafficking of plasmids for gene therapy: mechanisms of cytoplasmic movement and nuclear import. Curr Gene Ther 2006; 6:671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Talukder SR, Dudley DD, Alt FW, et al. Increased frequency of aberrant V(D)J recombination products in core RAG-expressing mice. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:4539–4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Ji Y, Resch W, Corbett E, Yamane A, Casellas R, Schatz DG. The in vivo pattern of binding of RAG1 and RAG2 to antigen receptor loci. Cell 2010; 141:419–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Subrahmanyam R, Du HS, Ivanova I, et al. Localized epigenetic changes induced by D-H recombination restricts recombinase to DJ(H) junctions. Nat Immunol 2012; 13:1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Kwon J, Morshead KB, Guyon JR, et al. Histone acetylation and hSWI/SNF remodeling act in concert to stimulate V(D)J cleavage of nucleosomal DNA. Mol Cell 2000; 6:1037–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Shimazaki N, Tsai AG, Lieber MR. H3K4me3 stimulates the V(D)J RAG complex for both nicking and hairpinning in trans in addition to tethering in cis: implications for translocations. Mol Cell 2009; 34:535–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Grundy GJ, Yang W, Gellert M. Autoinhibition of DNA cleavage mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 is overcome by an epigenetic signal in V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:22487–22492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Roman CAJ, Cherry SR, Baltimore D. Complementation of V(D)J recombination deficiency in RAG-1(−/−) B cells reveals a requirement for novel elements in the N-terminus of RAG-1. Immunity 1997; 7:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Wu C, Bassing CH, Jung D, et al. Dramatically increased rearrangement and peripheral representation of V beta 14 driven by the 3′Dbeta1 recombination signal sequence. Immunity 2003; 18:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Golding A, Chandler S, Ballestar E, et al. Nucleosome structure completely inhibits in vitro cleavage by the V(D)J recombinase. EMBO J 1999; 18:3712–3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Wang XM, Xiao G, Zhang YF, et al. Regulation of Tcrb recombination ordering by c-Fos-dependent RAG deposition. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Zhang YN, Xu K, Deng AQ, et al. An amphioxus RAG1-like DNA fragment encodes a functional central domain of vertebrate core RAG1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Hesse JE, Lieber MR, Gellert M, et al. Extrachromosomal DNA substrates in pre-B cells undergo inversion or deletion at immunoglobulin V-(D)-J joining signals. Cell 1987; 49:775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Corneo B, Wendland RL, Deriano L, et al. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature 2007; 449:483-U410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Rui JX, Liu HF, Zhu XY, et al. Epigenetic silencing of Cd8 genes by ThPOK-mediated deacetylation during CD4 T cell differentiation. J Immunol 2012; 189:1380–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Generation of RAG1KI/KI mice.

Comparison of recombination products between RAG1KI/KI and RAG1+/+ mice.

Two additional repeats of the bone marrow transfer experiment in Figure 4.

Two additional repeats of the bone marrow transfer experiment in Figure 5.