Abstract

Spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) can produce numerous male gametes after transplantation into recipient testes, presenting a valuable approach for gene therapy and continuous production of gene-modified animals. However, successful genetic manipulation of SSCs has been limited, partially due to complexity and low efficiency of currently available genetic editing techniques. Here, we show that efficient genetic modifications can be introduced into SSCs using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. We used the CRISPR-Cas9 system to mutate an EGFP transgene or the endogenous Crygc gene in SCCs. The mutated SSCs underwent spermatogenesis after transplantation into the seminiferous tubules of infertile mouse testes. Round spermatids were generated and, after injection into mature oocytes, supported the production of heterozygous offspring displaying the corresponding mutant phenotypes. Furthermore, a disease-causing mutation in Crygc (Crygc−/−) that pre-existed in SSCs could be readily repaired by CRISPR-Cas9-induced nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), resulting in SSC lines carrying the corrected gene with no evidence of off-target modifications as shown by whole-genome sequencing. Fertilization using round spermatids generated from these lines gave rise to offspring with the corrected phenotype at an efficiency of 100%. Our results demonstrate efficient gene editing in mouse SSCs by the CRISPR-Cas9 system, and provide the proof of principle of curing a genetic disease via gene correction in SSCs.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas9, spermatogonial stem cell, gene therapy

Introduction

Spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) can self-renew and undergo spermatogenesis, leading to the production of numerous spermatozoa, which transmit the genetic information to the next generation1,2. SSCs from different species can be maintained in vitro for long periods of time in medium supplemented with glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)3,4,5,6,7. Meanwhile, after transplantation into the testes of an infertile male, cultured SSCs can re-establish spermatogenesis and restore fertility1,8,9. As genetic manipulation of SSCs and the subsequent transplantation allow one to select for desired genetic modifications, these techniques hold great promise in producing gene-modified animal models and particularly in treating genetic diseases with the potential of generating healthy progeny at 100% efficiency1,10. However, so far there have been very limited reports of using these techniques for efficient production of gene-modified animals11,12, and their use in genetic disease correction has not yet been reported, partially due to complexity and low efficiency of currently available genetic editing techniques.

Recently, the CRISPR-Cas9 system from bacteria has enabled rapid genome editing in different species at a very high efficiency and specificity13,14,15,16,17. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing requires only a short single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to guide site-specific DNA recognition and cleavage, resulting in gene modification at a target locus via nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated insertions/deletions (indels) or homology-directed repair (HDR) based on an exogenously supplied oligonucleotide18. This system is relatively easy to implement compared to other genetic editing techniques19. By zygote injection of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs, mice or rats carrying desired mutations can be generated in one step18,20,21,22,23. Impressively, CRISPR-Cas9 can correct a defect associated with cystic fibrosis in human adult stem cells24. By delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 system through hydrodynamic injection, a Fah mutation in hepatocytes of a mouse model was corrected and the body weight loss phenotype was rescued25. Moreover, mice with mutations in the Crygc gene or dystrophin gene (Dmd) that causes cataracts or Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD)26,27 can be corrected by coinjection of Cas9 mRNA and an sgRNA targeting the mutant alleles into zygotes28,29, showing the feasibility of applying the CRISPR-Cas9 system to gene therapy30. Nevertheless, direct injection of the CRISPR-Cas9 system into zygotes could not produce healthy progeny at an efficiency of 100% and could potentially generate unwanted modifications in the offspring genome, including off-target modifications28, which would prohibit its use in the correction of human genetic diseases. We reasoned that successful gene editing in SSCs that contain a disease-causing mutation using the CRISPR-Cas9 system should allow for the selection of single SSC colonies or single SSCs that carry the desired gene modification without any other unwanted genomic changes and that such single colony-derived SSC lines or clonal SSC lines from single SSCs could then be used to produce healthy offspring at 100% efficiency. Here, we report the successful application of this approach in correcting a mouse genetic disease.

Results

Feasibility of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs

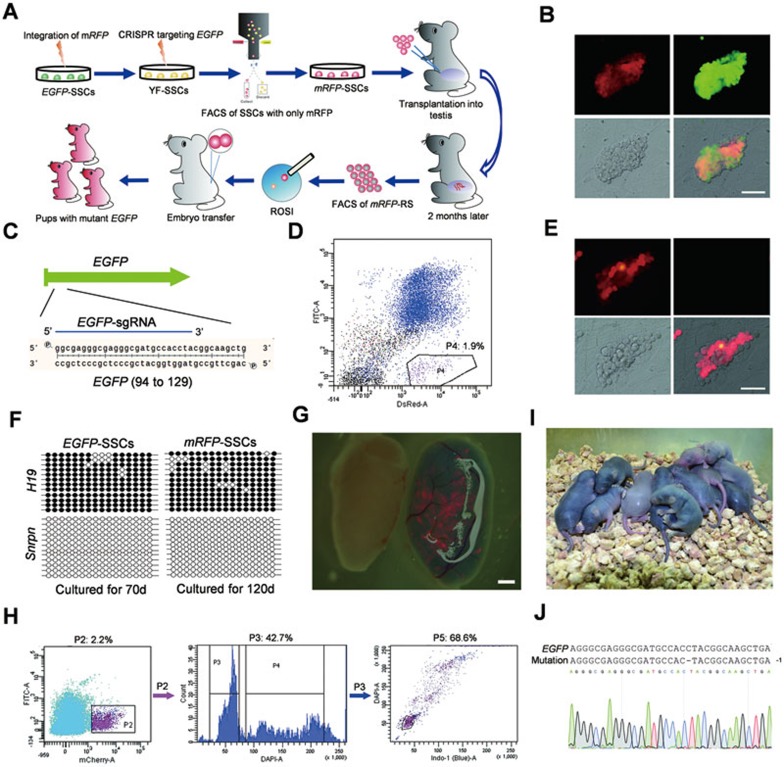

We first tested the feasibility of using the CRISPR-Cas9 system for gene editing in mouse SSCs. To this end, we attempted to disrupt an EGFP transgene in SSCs (Figure 1A) derived from testes of one 6.5-day-old actin-EGFP transgenic male mice (heterozygous, B6D2F1; termed EGFP-SSCs)31 according to the protocol described by Kanatsu-Shinohara M et al.32. To facilitate the tracking of EGFP-mutated SSCs, we attempted to derive SSCs carrying both EGFP and mRFP transgenes. For this the EGFP-SSCs were transfected with PB-mRFP and pBase (PB transposase enzyme). Two weeks after seeding the transfected single cell suspensions, SSCs were harvested and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). After FACS enrichment of SSCs expressing red fluorescent protein for 2 rounds, a SSC line expressing green and red fluorescent proteins simultaneously was established (termed YF-SSCs; Figure 1B). We then designed an sgRNA targeting the EGFP transgene (termed EGFP-sgRNA) and transfected pX330-mCherry plasmids expressing Cas9 and EGFP-sgRNA (Figure 1C) into 4 × 106 YF-SSCs. As we could not distinguish between the transient expression of mCherry, which was used as a marker to isolate the CRISPR-Cas9-transfected cells from cell populations and usually completely diminished in 4 days, and the expression of mRFP, we employed FACS two weeks after transfection, instead of one day after transfection, in other experiments to sort the SSCs expressing mRFP alone (Figure 1D). These cells, presumably carrying mutated EGFP transgenes and referred to as RFP-SSCs, were enriched and further expanded in SSC culture medium. The mRFP-positive SSCs showed typical SSC morphology (Figure 1E) and maintained paternal genomic imprints (Figure 1F). After being cultured for several passages in vitro, RFP-SSCs were harvested and transplanted into the testes of busulfan-treated male mice (Supplementary information, Table S1). One and half months later, we observed that RFP-SSCs recolonized in seminiferous cords (Figure 1G). Furthermore, mRFP-positive haploid cells (round spermatids, RS) could be isolated from these animals according to a reported protocol33 (Figure 1H). To test the function of exogenous SSC-derived spermatids, we performed intracytoplasmic round spermatid injection (ROSI). Injected oocytes were cleaved into 2-cell embryos efficiently. After transplantation of 2-cell embryos into oviducts of pseudopregnant females, a total of 39 pups were born at 19.5 days of gestation (Figure 1I and Table 1). As expected, none of the pups expressed EGFP. DNA sequencing analysis showed that about 50% (21/39) of the pups carried mutations in the EGFP transgene as a result of NHEJ-mediated indels (Figure 1J and Supplementary information, Figure S1) while the remaining pups did not carry the EGFP transgene, conforming to the expected Mendelian segregation pattern, as the EGFP-SSCs was heterozygous for actin-EGFP31.

Figure 1.

Mice carrying mutant EGFP transgene generated via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs. (A) Diagram for the generation of mice with mutant EGFP transgene through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs. EGFP-SSCs are electroporated with RFP vector to generate YF-SSCs. The EGFP transgene is mutated by CRISPR-Cas9, resulting in RFP-SSCs. Two months after transplantation of RFP-SSCs into infertile male mice, RFP-marked RS are enriched from reconstituted testes and injected into mature oocytes to produce mice carrying mutant EGFP transgenes. RS, round spermatids; ROSI, round spermatid injection. (B) Images of YF-SSCs. Top, red fluorescence (left) and green fluorescence (right); Bottom, bright-field image (left) and overlay (right). Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Schematic of sgRNA targeting EGFP transgene (EGFP-sgRNA). Blue line labels the sgRNA-targeting sequence. (D) FACS enrichment for RFP-SSCs after mutation of EGFP transgenes in YF-SSCs via the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Cells from P4 zone, which expressed RFP alone, were enriched for further expansion. (E) Images of RFP-SSCs. Top, red fluorescence (left) and green fluorescence (right); Bottom, bright-field image (left) and overlay (right). The EGFP transgene has been successfully mutated in YF-SSCs. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Methylation analysis of the DMRs of H19 and Snrpn in EGFP-SSCs and RFP-SSCs. Open and filled circles represent unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively. (G) RFP-SSCs can reconstitute the testis of busulfan-treated male mice. Normal testis (left); reconstituted testis with RFP-SSCs (right). RFP-positive seminiferous tubules can be observed in reconstituted testis with red fluorescence. Scale bar, 1 mm. (H) RFP-positive cells (cells of P2 zone in left image) are sorted from reconstituted testis and haploid cells (RS) are further isolated from RFP-positive cells according to DNA content. (I) Newborn pups developed from 2-cell embryos generated after injection of RFP-positive RS into mature oocytes. (J) DNA sequencing analysis of progeny. Note that the sequence of PCR products amplified from the EGFP transgene shows 1-bp deletion in one pup.

Table 1. Mice produced from round spermatids derived from gene-modified SSCs via CRISPR-Cas9.

| Target gene | Types of transplanted SSCs | Genetic background of SSCs | Injected oocytes | Transferred 2-cell embryos | Live-born pups | Gene-modified pups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | FACS-enriched RFP-SSCs after mutation of EGFP in YF-SSCs | B6D2F1 | 320 | 253 | 39 | 21 |

| Crygc | SSCs after mutation of Crygc in EGFP-SSCs | B6D2F1 | 495 | 453 | 23 | 13 (10 cataract mice) |

| mCrygc | Line-NHEJ-4 derived from expansion of single SSC colony (carrying modified but not repaired Crygc) | BALB/c | 207 | 192 | 5 | 5 (5 cataract mice) |

| mCrygc | Line-NHEJ-9 derived from expansion of single SSC colony (carrying corrected Crygc gene via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated NHEJ repair) | BALB/c | 399 | 361 | 9 | 9 (9 repaired mice) |

| mCrygc | Line-HDR1-8 derived from expansion of single SSC colony (carrying corrected Crygc gene via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR repair) | BALB/c | 103 | 95 | 3 | 3 (3 repaired mice) |

| mCrygc | Line-HDR1-11 derived from expansion of single SSC colony (carrying corrected Crygc gene via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR repair) | BALB/c | 278 | 234 | 27 | 27 (27 repaired mice) |

mCrygc: mutant Crygc gene

Efficient mutation of endogenous genes in SSCs by CRISPR-Cas9

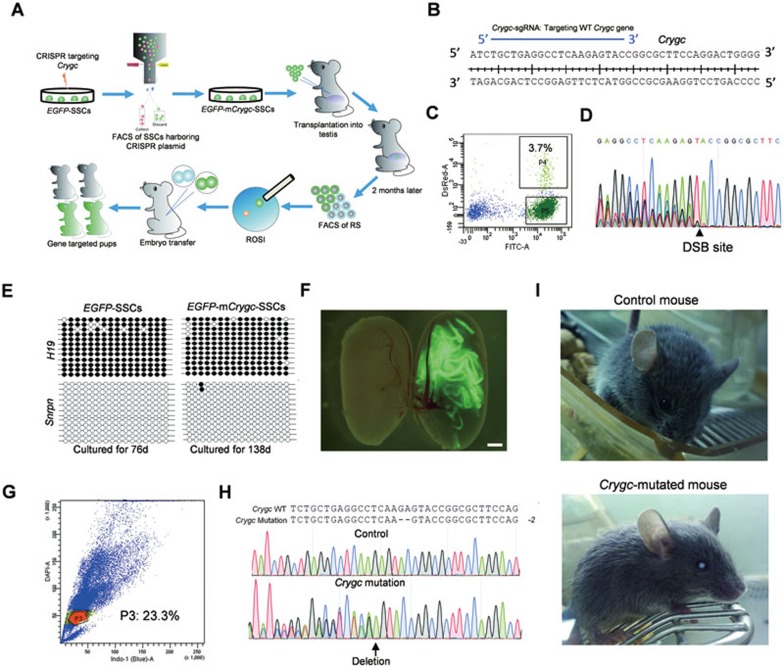

We next tested whether CRISRP-Cas9 system could also be applied to study the gene function by mutation of an endogenous gene in SSCs (Figure 2A). We chose the Crygc gene for this purpose since a 1-bp deletion in exon 3 of Crygc could lead to a stop codon at the 76th amino acid and thus the production of truncated γC-crystalin, resulting in nuclear cataracts in both homozygous and heterozygous mutant mice26. One day after transfection of EGFP-SSCs with pX330-mCherry plasmids expressing Cas9 and an sgRNA targeting the WT Crygc gene (termed Crygc-sgRNA) (Figure 2A and 2B), the SSCs expressing mCherry (around 3.7%, Figure 2C), in which the CRISPR-Cas9 system was successfully transfected, were enriched and plated at low density on plates. These cells, referred to as EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs, were expanded for one month in vitro. CRISPR-Cas9 could induce double strand breaks (DSB), leading to NHEJ-mediated indels in the Crygc gene (Figure 2D). To test the targeting efficiency, we randomly picked 25 SSC colonies. DNA sequencing of PCR products obtained from the amplified target site showed that 21 colonies carried mutant Crygc genes at one or two alleles (Supplementary information, Figure S2A and Table S2), showing high efficiency of gene editing in SSCs once the CRISPR-Cas9 system has been successfully transfected. We further validated the CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene targeting in SSCs by successful mutation of another endogenous gene p53 and by mutation of Crygc, p53 and Exo5 genes simultaneously (Supplementary information, Tables S2, S3 and Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Cataract mice generated via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs. (A) Diagram for the generation of cataract mice carrying mutant Crygc genes through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs. EGFP-SSCs are electroporated with CRISPR-Cas9 targeting the Crygc gene. One day after transfection, mCherry-positive cells, which presumably are successfully transfected with the CRISPR-Cas9 system, are enriched for further expansion. EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs are passaged for several times in vitro. Two months after transplantation of EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs into infertile male mice, EGFP-marked RS are enriched from reconstituted testes and injected into mature oocytes to produce cataract mice carrying mutant Crygc gene. (B) Schematic of sgRNA targeting endogenous Crygc gene (Crygc-sgRNA). Blue line labels the sgRNA-targeting sequence. (C) FACS enrichment for mCherry-positive cells (P4 zone), which represent the cells transfected with the CRISPR-Cas9 system, for further expansion. (D) CRISPR-Cas9 induces double strand breaks (DSB) efficiently and produces NHEJ-mediated indels in Crygc gene. Note that the sequence of PCR products amplified from the Crygc gene shows multiple peaks in SSCs. (E) Methylation analysis of the DMRs of H19 and Snrpn in EGFP-SSCs and EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs. Open and filled circles represent unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively. (F) EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs can reconstitute the testis of busulfan-treated male mice. Normal testis (left); reconstituted testis with EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs (right). EGFP-positive seminiferous tubules can be observed in reconstituted testis with green fluorescence. Scale bar, 1 mm. (G) RS are sorted from cells of reconstituted testes according to DNA content. 23.3% means the total of haploid cells, including the donor-derived and recipient-derived cells. (H) DNA sequencing analysis of two pups developing from reconstructed oocytes generated after injection of RS into mature oocytes. Note that the sequences of PCR products amplified from the Crygc gene show no gene modification in one pup and 2-bp deletion in the other one. (I) The same two pups in H, after growing up to adult, show normal lenses (top) and cataract phenotype (bottom), respectively.

Bisulfite sequencing analysis of EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs showed that typical paternal imprinting status was maintained in these SSCs (Figure 2E). We then transplanted EGFP-mCrygc-SSCs into the testes of busulfan-treated male mice (Supplementary information, Table S1). Two months later, FACS analysis indicated that the reconstituted testes (Figure 2F) contained about a total of 16.8%-32.4% of haploid cells (Figure 2G and Supplementary information, Table S1). ROSI experiments using spermatids harvested from these testes produced a total of 23 live pups (Table 1). By DNA sequencing analysis, we identified 13 mice carrying NHEJ-mediated indels in the Crygc gene (Figure 2H and Supplementary information, Figure S2B). Of these, 10 mice carried indels in exon 3 of Crygc (Figure 2H and Supplementary information, Figure S2B) that led to the formation of a stop codon; as expected, these animals displayed cataract phenotypes (Figure 2I and Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest that the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used for efficient gene editing in SSCs, which could then support the derivation of gene-modified mouse models after transplantation into recipient testes.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genetic repair in SSCs

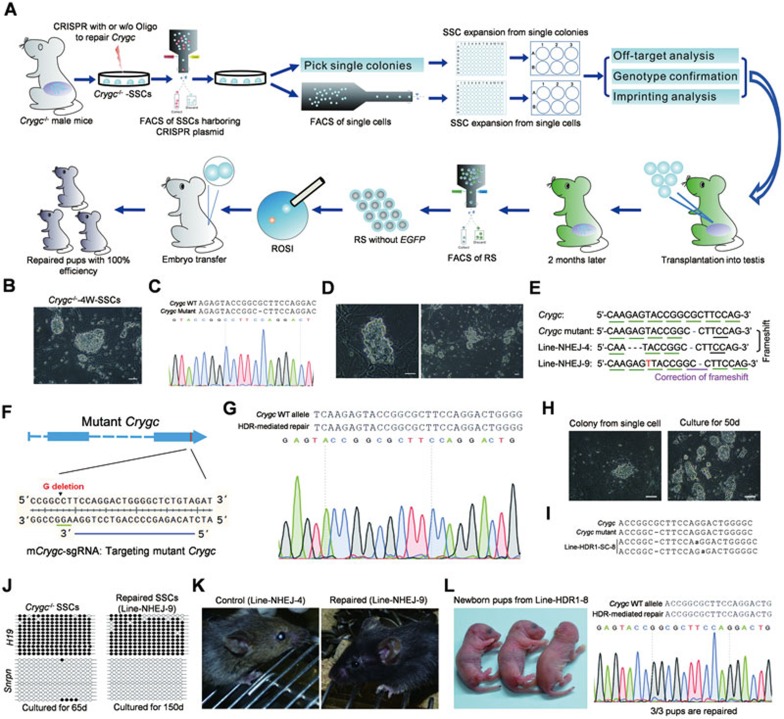

Single SSCs can be expanded in vitro for a long period of time and support the production of offspring11,34, providing a unique system in which SSCs can be well analyzed and pre-selected before transplantation (Figure 3A). Successful implementation of this system thus would enable the generation of desired gene-modified individuals at 100% efficiency (Figure 3A), which could be further applied to treat genetic diseases. To test this, we established two SSC lines from one 4-week-old and one 8-week-old homozygous cataract males26 (BALB/c) carrying a 1-bp deletion at both alleles of the Crygc gene (termed Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs and Crygc−/−-8W-SSCs), respectively (Figure 3B and 3C) and attempted to repair the mutant Crygc gene to produce cataract-free progeny. One day after electroporation of Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs, Crygc−/−-8W-SSCs or cells from both lines with pX330-mCherry plasmids expressing Cas9 and Crygc-sgRNA (Figure 2B), the SSCs expressing mCherry, in which the CRISPR-Cas9 system was successfully transfected, were enriched and plated at low density on plates. One week later, single SSC colonies were picked up and each colony was transferred to one well of the 96-well plate for derivation of SSC lines. SSC expansion proceeded from 96-well plates to 6-well plates for routine culture in SSC medium (Figure 3D). A total of 24 colonies were randomly selected for expansion, leading to 21 stable, single colony-derived SSC lines (Supplementary information, Table S4). DNA sequencing of PCR products amplified from the target site showed that 17 of them carried gene modifications at one allele or two alleles of the mutant Crygc gene (termed Line-NHEJ-1 to Line-NHEJ-17; Supplementary information, Table S4 and Figure S4). An analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the modified alleles in these 17 lines revealed that 12 cell lines carried repaired Crygc gene (Supplementary information, Table S4). For example, as shown in Figure 3E and Supplementary information, Figure S4, two lines (Line-NHEJ-9 and Line-NHEJ-13) carried NHEJ-mediated insertion of 1 bp (T) at the same position of two alleles in all sequenced colonies, which would result in restoration of the correct open reading frame in the Crygc gene.

Figure 3.

Correction of a genetic disease in mouse via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs. (A) Diagram for the correction of a genetic disease in mouse through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs. Crygc−/−-SSCs are established from male cataract mice carrying homozygous mutant Crygc gene. Crygc−/−-SSCs are electroporated with CRISPR-Cas9 targeting the Crygc gene with or without exogenously supplied oligonucleotide. mCherry-positive cells, which are transfected SSCs, are enriched for further expansion. Single colonies are picked and transferred into one well of 96-well plates for SSC line derivation. To derive SSC lines from singe SSCs, single mCherry-positive cells are deposited into one well of 96-well plates by BD FACSAriaII cell sorter for expansion. Clonal expansion of single SSCs or SSC colonies proceeds from 96-well plates to 6-well plates for routine culture in SSC medium. SSC lines derived from single SSCs or SSC colonies are characterized and SSC lines carrying corrected Crygc gene without off-target mutations are selected for transplantation into infertile male mice carrying homozygous EGFP transgenes. Two months later, non-EGFP-marked RS are isolated from reconstituted testes and injected into mature oocytes to produce healthy mice carrying corrected Crygc gene. (B) Crygc−/−-4W-SSC line show typical SSC morphology. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) DNA sequencing analysis of Crygc−/−-SSCs shows 1-bp deletion at both alleles. (D) Clonal expansion of single SSC colony from 96-well plates to 6-well plates for routine culture in SSC medium. Left, one SSC colony in one well of 96-well plate; Right, one established SSC line from single SSC colony in one well of 6-well plate. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) DNA sequencing analysis of SSCs from Line-NHEJ-4 and Line-NHEJ-9. Line-NHEJ-4 carries CRISPR-Cas9-mediated 3-bp deletion at the same loci of two alleles, which could not restore the correct open reading frame in Crygc gene. In contrast, Line-NHEJ-9 carries 1-bp insertion at the same loci of two alleles, thus restoring the correct open reading frame in Crygc gene. Deletions are indicated with (−). Letter marked in red represents the inserted nucleotide. (F) Schematic of sgRNA targeting mutant Crygc gene (mCrygc-sgRNA). Blue line labels the sgRNA-targeting sequence. The PAM is labeled with green line. (G) DNA sequencing analysis of SSCs from Line-HDR1–8. Note that the sequence of PCR products amplified from the Crygc gene shows that Line-HDR1-8 carries corrected Crygc gene. (H) SSC expansion of single SSC from 96-well plates to 6-well plates for routine culture in SSC medium. Left, one SSC colony formed from single SSC in one well of 96-well plate; Right, one established SSC line from single SSC in one well of 6-well plate. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I) DNA sequencing analysis of SSCs from Line-HDR1-SC-8. Line-HDR1-SC-8 carries NHEJ-mediated insertion of 1 bp (A) at 6 bp downstream of the deletion site at one allele and insertion of 1 bp (A) at 7 bp downstream of the deletion site at the other allele, which would result in the restoration of the correct open reading frame at both alleles of the Crygc gene. (J) Methylation analysis of the DMRs of H19 and Snrpn in Crygc−/−-SSCs and Line-NHEJ-9. Open and filled circles represent unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively. (K) One adult mouse from Line-NHEJ-4 shows cataract phenotype (left), and one adult mouse from Line-NHEJ-9 shows normal lenses (right). (L) Three newborn pups (left) developing from reconstructed oocytes generated after injection of RS from Line-HDR1-8 into mature oocytes. Genotyping analysis of the pups (right). Note that the sequence of PCR products amplified from the Crygc gene shows only one peak in 3 pups, indicating successful transmission of the corrected Crygc gene in repaired SSCs to progeny.

We next asked whether HDR-mediated precise genome editing could be implemented in SSCs carrying Crygc−/− by co-electroporation of plasmids encoding Cas9 and an sgRNA28, which could specifically target the mutant allele of Crygc gene (termed mCrygc-sgRNA; Figure 3F) and an exogenous single-strand oligonucleotide with WT sequence (Oligo-1)28 or with WT sequence harboring two synonymous mutations (Oligo-2)28. A total of 23 single colony-derived SSC lines were generated from electroporation of Oligo-1 (Supplementary information, Table S4). DNA sequencing results showed that 18 of them carried gene modifications of the mutant Crygc gene. Of these, 11 carried two repaired alleles of the Crygc gene induced by NHEJ or HDR (Supplementary information, Figure S5), in which one line carried HDR-mediated correction at one allele and NHEJ-mediated correction at the other allele (termed Line-HDR1-12) and two lines carried HDR-mediated correction at both alleles (termed Line-HDR1-8 and Line-HDR1-11, respectively; Figure 3G and Supplementary information, Figure S5). A total of 13 single colony-derived SSC lines were derived from electroporation of Olig-2, in which one line (termed Line-HDR2-2) carried HDR-mediated correction at both alleles (Supplementary information, Figure S5 and Table S4).

As SSCs readily aggregate in culture and colonies can be polyclonal, the derived single colony-derived SSC lines, while some of them showed identical genotype, may not be originated from single cells. To establish cured clonal SSC lines from single SSCs, one day after electroporation of Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs with CRISPR-Cas9 and Oligo-1, the SSCs expressing mCherry were enriched and expanded in vitro. One week later, single cell suspension was employed for FACS using a BD FACSAriaII cell sorter for depositing one individual cell into each well of the 96-well plates (Figure 3A) as previously reported35. From a total of 480 single SSCs, we established 11 stable clonal SSC lines (Figure 3H), in which 8 carried gene modifications of the mutant Crygc gene (Supplementary information, Table S4). Of these, 5 carried repaired Crygc gene (Supplementary information, Table S4), in which 3 lines carried NHEJ-mediated corrections at both alleles and 2 lines carried NHEJ-mediated and HDR-mediated correction at one allele, respectively (Supplementary information, Figure S5C). As an example, a cell line (referred to as Line-HDR1-SC-8), as shown in Figure 3I, carried NHEJ-mediated insertion of 1 bp (A) at 6 bp downstream of the deletion site at one allele and insertion of 1 bp (A) at 7 bp downstream of the deletion site at the other allele, which would result in the restoration of the correct open reading frame in both alleles of the Crygc gene.

A total of 34 cured SSC lines were derived from single colony or single SSC expansion after CRISPR-Cas9-mediated rescue of the mutant Crygc gene. To avoid the potential transmission of off-target mutations to progeny, we analyzed off-target effects in the 15 SSC lines derived from single SSC colony or single SSC that harbor Crygc corrected by HDR or HNEJ at both alleles. First, we searched the mouse genome for sites with a minimum of 14 consecutive nucleotides of shared identity with the authentic target sequence based on the recent findings that a maximum level of mismatch that could be tolerated in the “target” sequence is no more than five nucleotides36,37,38. This led to the identification of a total of 10 potential off-target sites28 (Supplementary information, Table S5). Second, we used the tool developed by Hsu et al.37 for predicting off-target loci. Top 11 (value > 1) potential “off-target” sites were selected for analysis (Supplementary information, Table S5). DNA sequencing of PCR products amplified from these genomic sites showed that no mutation had occurred at these loci in all 15 SSC lines examined. To investigate the off-target effect at single base resolution, we performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analysis of the corrected line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs derived from a single SSC and its parental Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs. In total, we obtained 22× and 24× sequencing data from Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs and Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs, respectively (Supplementary information, Table S6). The high-throughput sequencing data revealed normal karyotype of the Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs (Supplementary information, Figure S6A) and well-rescued open reading frame of Crygc gene (Supplementary information, Figure S6B), indicating that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing does not introduce significant copy number variations. From these data we detected 96 single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and 89 indels in the Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs compared with its parental Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs (Supplementary information, Table S7) after filtering the false-positive mutations according to a recent study39. Given that the Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs were amplified from an individual target cell to several millions of cells, the number of cell division during this process should be around 20–23. Thus, the average numbers of point mutations or indels per cell division were 4-5, which are comparable to the spontaneous germline mutation rate in vivo40,41. Moreover, none of the 96 SNVs or 89 indels were in the exon regions of RefSeq genes (Supplementary information, Table S8), except one indel located in exonic region of Crygc gene as expected, since this indel resulted in the restoration of the correct open reading frame at both alleles of the Crygc gene in Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs (Figure 3I and Supplementary information, Table S9). Besides, we checked all of the 28 374 genomic regions in the SSC genome that contain 1-5 bp mismatch to the designed sgRNA sequence. None of 89 indels overlapped with any of these 28 374 potential off-target genomic regions. Similarly, only one out of 96 SNVs detected in an intergenic region overlapped with a genomic region showing a 5 bp mismatch to the sgRNA sequence (Supplementary information, Table S10). Taken together, these data indicate that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene correction does not induce significant off-target alterations in SSC genome in general, consistent with the recent observations of low incidence of CRISPR-Cas9-induced off-target mutations in human cells using the similar analysis method42,43.

As the correct paternal imprinting state is critical for the function of SSCs, we then investigated the methylation profile of the imprinted genes in these cured SSCs. Bisulfite sequencing analysis of H19 and Snrpn showed that 8 lines stably maintained typical paternal imprinting status (Figure 3J). To further investigate whether CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in SSCs would change imprinting pattern in SSCs, we performed whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) analysis of the cured Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs derived from single SSC and its parental Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs (Supplementary information, Table S11). The methylation pattern of both samples showed no significant difference between each other at whole-genome scale (Supplementary information, Figure S7A). Furthermore, among all of the 21 known germline imprinting control regions44, we recovered 12 of them with enough coverage in both samples (Supplementary information, Figure S7B and S7C). The results showed that the Line-HDR1-SC-8 SSCs maintained a typical paternal imprinting status, which was comparable to their parental Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs (Supplementary information, Figure S7B and S7C). Moreover, the methylation pattern of the gene body and flanking region of Crygc gene (Supplementary information, Figure S7D) were same in both samples. Taken together, these data indicate that CRISPR-Cas9-meditated gene editing would not change the DNA methylation pattern in SSCs in general.

Finally, we transferred SSCs from three cured cell lines (Line-NHEJ-9, Line-HDR1-8 and Line-HDR-11) and one control cell line (SSCs of Line-NHEJ-4, in which both alleles of Crygc gene were targeted but not repaired) into recipient testes of infertile males with homozygous EGFP marker (Supplementary information, Table S1). Two months later, EGFP-negative haploid cells (Supplementary information, Figure S8 and Table S1) derived from all four cell lines were isolated and used for ROSI. A total of 39 live pups were born from SSCs of three cured cell lines, and as expected, genotyping analyses confirmed the successful transmission of the corrected Crygc gene in SSCs to progeny (Figure 3K, 3L and Table 1). As control, a total of 5 live pups were born using Line-NHEJ-4-derived spermatids, and all 5 displayed cataract phenotypes (Figure 3K and Table 1).

Discussion

Recent studies are showing great potential of applying CRISPR-Cas9 system to gene therapy. We28 and others29 reported that the CRISPR-Cas9 system, after being injected into zygotes, could correct disease-causing mutations in mice. Nevertheless, direct injection of CRISPR-Cas9 system into zygotes could not produce healthy progeny at an efficiency of 100% and could potentially generate off-target modifications. To circumvent these problems, the possible strategy is to correct genetic defects in germline cells, such as SSCs, which could be well established from male individuals3,4, select single SSCs that carry the desired gene modification without any other unwanted genomic changes, and use such SSC lines to produce healthy offspring at 100% efficiency. Here, we have demonstrated that the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be successfully applied in SSCs to efficiently generate gene-modified mouse models or correct genetic diseases in mouse. Pre-selection of SSC lines carrying the desired genotype without off-target mutations is feasible and this would enable the generation of healthy progeny, at an efficiency of 100%, from a father carrying a homozygous genetic defect. Importantly, using high throughput technologies, we have demonstrated that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene correction neither induces off-target mutations nor changes the paternal imprinting patter in SSC genome in general, showing great promise in using CRISPR-Cas9 to treat genetic diseases through germline cells.

Human SSCs have been maintained in vitro for long periods of time in several laboratories5,6; while these results need to be replicated in other laboratories45, we believe that in the future, after an standard protocol for high-efficient generation of human SSCs has been established, it would be of great interest to investigate whether similar gene editing strategies could be used for mutation correction in human SSCs in a setting related to paternal genetic diseases. The system of SSC-based gene therapy, in addition to the potential use in cases in which the father carries a homozygous genetic defect, could also be applied to treat the following genetic conditions: (1) male infertility induced by genetic defects, (2) father-carrying dominant disease alleles, and (3) sex chromosome-linked dominant genetic diseases46,47,48.

Materials and Methods

Animal use and care

All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the guidelines of the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences.

Construction of CRISPR plasmids

The Cas9 and sgRNA plasmid pX330 were obtained from Addgene (Addgene plasmid 42230). The CMV-mcherry-pA cassette was inserted into pX330 to get the pX330-mcherry as described previously28. The sgRNAs targeting EGFP, Crygc, p53 or Exo5 genes were synthesized, annealed and ligated to the pX330 plasmid that was digested with Bbs I (New England Biolabs).

Derivation of SSCs

To derive EGFP-SSC and Crygc−/−-SSC lines, we sorted cells from testes of 6.5-day-old actin-EGFP transgenic male mice and BALB/cAnSlac−Crygc<m1Sbao> male mice26 using two cell surface markers, c-kit and CD9. C-kit is a marker for differentiating spermatogonia49 and CD9 is a common surface marker for mouse and rat germline stem cells50. C-kit negative and CD9 positive (C-kit−:CD9+) cells represented enriched SSC population. C-kit−:CD9+ cells were seeded on the mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder cells and cultured with the modified SSC medium according to a previously reported protocol32.

The culture medium consisted of StemPro-34 SFM (Invitrogen) supplemented with StemPro supplement (Invitrogen), 25 μg/ml insulin, 100 μg/ml transferrin, 60 μM putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite, 6 mg/ml D-(+)-glucose, 30 μg/ml pyruvic acid, 1 μl/ml dl-lactic acid (Sigma), 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine (Millipore), β-mercaptoethanol (Millipore), minimal essential medium vitamin solution (Invitrogen), non-essential amino acid solution (Millipore), penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM ascorbic acid, 10 μg/ml d-biotin (Sigma), 20 ng/ml recombinant human epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml human basic fibroblast growth factor (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml recombinant human GDNF (Invitrogen) and 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS; ES cell-qualified, Invitrogen). The cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Culture medium was changed every 2-4 days. All cultured cells were tested to ensure that they are mycoplasma free.

Transplantation of SSCs

For SSC transplantation, busulfan (40 mg/kg)-treated 4-6 weeks old F1 or EGFP male mice were used as the recipient mice. Approximately 2-3 × 105 cells were injected with a micropipette (60 μm diameter tips) into the seminiferous tubules of the testes of recipient mice through the efferent duct. The mice were sacrificed 2 months later, and the testes were examined under a fluorescence microscope to detect existence of transplanted SSCs by their EGFP expression.

ROSI

Metaphase II-arrested oocytes were collected from superovulated B6D2F1 females (8-10 weeks) and cumulus cells were removed using hyaluronidase. After decapsulation and digestion, the testicular cell suspensions were filtered through a 40 m filter (Millipore). Then the suspensions were suspended with PBS containing 8% FBS. The haploid cells from the testes were sorted according to a reported protocol with minor modifications33. First, the cell suspensions were incubated with the Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing with PBS/FBS twice, haploid cells were sorted with flow cytometry (Influx™ cell sorter or BD FACSAria II cell sorter, BD Biosciences). The round spermatids were then injected into the oocytes in a droplet of HEPES-CZB medium containing 5 μg/ml cytochalasin B (CB) using a blunt Piezo-driven pipette. The injected oocytes were activated by treatment with SrCl2 for 5-6 h and maintained in the KSOM medium at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in air51. Two-cell embryos were transferred into the oviducts of pseudopregnant ICR females. Live fetuses were born on day 19.5 of gestation.

Electroporation of SSCs

The pX330-mcherry plasmids harboring corresponding sgRNAs and oligo DNA were transfected into SSCs with Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit L (Lonza) using Amaxa Nucleofector according to the manufacturer's instruction. For mutation of multiple endogenous genes, the pX330-mcherry plasmids harboring corresponding sgRNAs were simultaneously transfected into SSCs. 24 h after transfection, the SSCs expressing mCherry were separated with flow cytometry and plated on MEF feeders. Single colonies were picked and expanded for genotyping or transplantation. For the establishment of YF-SSC line, the EGFP-SSCs were nucleofected with PB-mRFP and pBase (PB transposase enzyme). After sorting of SSCs harboring red fluorescent protein with flow cytometry for 2 rounds, SSC line stably expressing EGFP and mRFP was established. For deriving SSC lines from single SSCs, FACS using a BD FACSAriaII cell sorter was adopted to deposit one mCherry-positive cell into each well of the 96-well plates.

Bisulfite sequencing

Bisulfite sequencing was performed using the EZ DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer's manual. Primers for bisulfite sequencing were listed in Supplementary information, Table S12. The PCR products were cloned into pMD18T TA cloning vector (Takara) and individual clones were then sequenced for subsequent analysis.

Cataract phenotype observation

For cataract phenotype analysis, the mouse pupils were dilated for 5-10 min with compound tropicamide eye drops before photographing.

DNA sequencing of target loci

Genomic DNA sequences around EGFP or Crygc mutation sites were amplified by PCR with specific primers (Supplementary information, Table S12) from SSC colonies, lines or gene-modified mice. First, the PCR products were sequenced using the primer listed in Supplementary information, Table S12 to confirm whether the sequencing results have single or double peaks. Subsequently, PCR products from each SSC lines or founder were cloned into pMD18T TA cloning vector (Takara) for transformation. After overnight culture at 37 °C, 8-16 colonies were randomly picked and sequenced.

WGS

A total of 6 × 105 Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs and 1.5 × 106 cured SSCs from Line-HDR1-SC-8 were used for gDNA extraction with DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) following the the manufacturer's instructions. For construction of WGS library, 1 μg gDNA was fragmented to around 300 bp by ultrasonication using Covaris S2 system. Then the sheared DNA fragments were used for library construction using Illumina TrueSeq DNA library preparation kit. The final quality-ensured libraries were sequenced on Illumina Hiseq 2000 or Hiseq 2500 for 100 bp pair-end reads. All the reads passing the quality control were converted into fastq files. For construction of WGBS library, 2-4 μg gDNAs with 1% spiked-in λDNA were sonicated to around 250-bp fragments. The DNA fragments were then end-repaired, added with an adenine at the 3′ end and ligated with Illunima DNA adaptors. After that the adaptor-ligated fragments were treated with MethylCode™ Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Invitrogen) to convert the unmethylated cytosines into uracils. Finally, the bisulfite-converted DNAs were PCR amplified for 4-7 cycles. The quality-ensured libraries were sequenced on Illumina Hiseq 2000 for 100 bp pair-end reads.

The raw sequencing reads were first filtered to remove low quality paired reads with the following criteria: (1) reads with more than 10% N bases; (2) reads with more than 50% bases with sequencing quality value less than 5; (3) reads with residual length less than 37 bases after the adaptor sequences were trimmed.

For WGS data, the reads were mapped to the mouse genome (mm9, downloaded from UCSC) using BWA tools with default parameters, while for the WGBS data, reads were mapped to the mouse genome using Bismark (version 0.7.6) with bowtie 1.

For SNV and indel calling, PCR duplications were removed for each sequencing library. Next, we merged all mapped data for the same sample. GATK tools were used to perform Indel realignment and base quality recalibration. We used VarScan (somatic function) to call SNV and Indel by comparing genomes of Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs and cured SSCs from Line-HDR1-SC-8 with criteria: (1) at least 8 reads covered at the same genome position for both samples considered to call mutations; (2) minor allele frequency > 0.35 for heterozygous SNV; (3) allele frequency > 0.9 for homozygous SNV; (4) somatic mutation P value (Fisher's exact test) should be < 0.05; (5) strand bias should be < 0.9; (6) average base quality for mutation supporting reads should be > 15.

To get accurate mutation callings, for all the called mutations, we next required that the genotype in mutant Crygc mouse should be homozygous without variant supporting reads, and the ratio of reads supporting variant in plus and minus (or minus/plus) strands should be less than 0.8 in CRISPR-repaired sample. At least 4 variant supporting reads were observed in both strands for indel calling. Mutations existing in dbSNP database for BALB and C57BL mouse genome were further filtered away. At last, we filtered away SNVs observed within 10 bp upstream and downstream of any Indels.

We first searched the reference genome to get genomic locations with 0-5 bp mismatches of designed oligo sequences. Next, we annotated the called mutations with these genomic locations besides their upstream and downstream 20 base pairs. Only if the called mutation is annotated with any of the genomic locations, it was defined as a putative CRISPR repair-associated mutation.

AnnoVar was used to annotate the called mutations with different genomic regions, including 5′ UTR, 3′ UTR, exonic regions, intronic regions, ncRNA regions, intergenic regions, downstream regions of transcription end site and upstream regions of transcription start site. Gene based annotation mode was used.

As called mutations located in the repeat regions are mainly false positive ones as reported in a previous study39, we followed this strategy to further filter the called SNVs and Indels within RepeatMasker annotated repetitive regions and their flanking 10-bp regions. And SNVs with adjacent distance within 10 bp were further filtered. Called mutations located in exonic region were manually checked.

WGBS

WGBS was performed to detect DNA methylation status of germline imprinting regions in both mutant Crygc and CRISPR-repaired samples. DNA methylation level of a single CpG site was estimated as the number of reported C divided by the total number of reported C and T. Only CpG sites with read coverage ≥ 3 were analyzed. To check the DNA methylation consistency between the two samples, we only focused on CpG sites covered in both samples. Germline imprinting annotation was referred from44.

Accession numbers

WGS and WGBS sets can be accessed as the GEO reference series SRP045395 and GSE60485, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2014CB964803 and 2011CB811304 to JL, 2012CB966704 and 2011CB66303 to FT, 2014CB943104 to LW), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31225017 and 91319310 to JL, 31271543 and 31322037 to FT), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01010403), and the Shanghai Municipal Commission for Science and Technology (12JC1409600 and 13XD1404000 to JL, 12JC1409400 to LW).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Summary of testis transplantation experiments

Summary of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated single gene editing in SSCs

Summary of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing in triple genes simultaneously

Summary of SSC lines derived from expansion of single colonies or single SSCs after CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene correction of mCrygc

The off-target analysis in cured SSC lines

Summary of whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis

Summary of whole genome mutations in Line-HDR1-SC-8

Annotation of called mutations in genomic regions

Description of one exonic mutation listed in Supplementary information, Table S8

Summary of off-target sites in Line-HDR1-SC-8 from WGS data

Summary of whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGSB)

The primers and oligonucleotides used in this study

The sequences of the EGFP transgene in mice carrying CRISPR-Cas9-induced modifications.

The sequences of the Crygc gene in SSC colonies (A) and mice (B) carrying CRISPR-Cas9-induced modifications.

The sequences of the p53 gene in SSC colonies (A) and the sequences of the p53, Crygc and Exo5 genes in SSC colonies (B).

The sequences of the Crygc gene in SSC lines generated from single SSC colonies derived from electroporation of Crygc-sgRNA into Crygc−/−-SSCs.

The sequences of the Crygc gene in SSC lines generated from single SSC colonies derived from electroporation of exogenous Olig-1 (A), Olig-2 (B) into Crygc−/−-SSCs or single SSCs derived from electroporation of Oligo-1 (C) into Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing rescued the mutant Crygc gene without causing CNVs.

DNA Methylation patterns were not disrupted by CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Isolation of non-EGFP haploid cells from testis reconstituted by transplantation of SSCs from Line-NHEJ-9 (upper) and Line-HDR1-8 (bottom) into recipient testes of infertile males with homozygous EGFP marker for ROSI.

References

- 1Kubota H, Brinster RL. Technology insight: In vitro culture of spermatogonial stem cells and their potential therapeutic uses. Nat Clin Pract Endocrino Metab 2006; 12:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Oatley JM, Brinster RL. The germline stem cell niche unit in mammalian testes. Physiol Rev 2012; 92:577–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Growth factors essential for self-renewal and expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:16489–16494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Ryu BY, Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Conservation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal signaling between mouse and rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102:14302–14307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5He Z, Kokkinaki M, Jiang J, Dobrinski I, Dym M. Isolation, characterization, and culture of human spermatogonia. Biol Reprod 2010; 82:363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Sadri-Ardekani H, Mizrak SC, van Daalen SK, et al. Propagation of human spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. JAMA 2009; 302:2127–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Muneto T, Lee J, et al. Long-term culture of male germline stem cells from hamster testes. Biol Reprod 2008; 78:611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Brinster RL, Avarbock MR. Germline transmission of donor haplotype following spermatogonial transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91:11303–11307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91:11298–11302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Dobrinski I. Male germ cell transplantation. Reprod Domest Anim 2008; 43(Suppl 2):288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ikawa M, Takehashi M, et al. Production of knockout mice by random or targeted mutagenesis in spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:8018–8023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Izsvak Z, Frohlich J, Grabundzija I, et al. Generating knockout rats by transposon mutagenesis in spermatogonial stem cells. Nat Methods 2010; 7:443–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Chang N, Sun C, Gao L, et al. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res 2013; 23:465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013; 339:819–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Dickinson DJ, Ward JD, Reiner DJ, Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat Methods 2013; 10:1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Friedland AE, Tzur YB, Esvelt KM, Colaiacovo MP, Church GM, Calarco JA. Heritable genome editing in C. elegans via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Methods 2013; 10:741–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 2013; 339:823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 2013; 153:910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Wei C, Liu J, Yu Z, Zhang B, Gao G, Jiao R. TALEN or Cas9 — rapid, efficient and specific choices for genome modifications. J Genet Genomics 2013; 40:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Li W, Teng F, Li T, Zhou Q. Simultaneous generation and germline transmission of multiple gene mutations in rat using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31:684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Shen B, Zhang J, Wu H, et al. Generation of gene-modified mice via Cas9/RNA-mediated gene targeting. Cell Res 2013; 23:720–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Yang H, Wang H, Shivalila CS, Cheng AW, Shi L, Jaenisch R. One-step generation of mice carrying reporter and conditional alleles by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 2013; 154:1370–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Li D, Qiu Z, Shao Y, et al. Heritable gene targeting in the mouse and rat using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31:681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Schwank G, Koo BK, Sasselli V, et al. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell 2013; 13:653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Yin H, Xue W, Chen S, et al. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat Biotechnol 2014; 32:551–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Zhao L, Li K, Bao S, et al. A 1-bp deletion in the gammaC-crystallin leads to dominant cataracts in mice. Mamm Genome 2010; 21:361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Bulfield G, Siller WG, Wight PA, Moore KJ. X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1984; 81:1189–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Wu Y, Liang D, Wang Y, et al. Correction of a genetic disease in mouse via use of CRISPR-Cas9. Cell Stem Cell 2013; 13:659–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Long C, McAnally JR, Shelton JM, Mireault AA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Prevention of muscular dystrophy in mice by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of germline DNA. Science 2014; 345:1184–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30High K, Gregory PD, Gersbach C. CRISPR technology for gene therapy. Nat Med 2014; 20:476–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Zhang M, Zhou H, Zheng C, et al. The roles of testicular C-kit positive cells in de novo morphogenesis of testis. Sci Rep 2014; 4:5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, et al. Long-term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod 2003; 69:612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Bastos H, Lassalle B, Chicheportiche A, et al. Flow cytometric characterization of viable meiotic and postmeiotic cells by Hoechst 33342 in mouse spermatogenesis. Cytometry A 2005; 65:40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. Genetic selection of mouse male germline stem cells in vitro: offspring from single stem cells. Biol Reprod 2005; 72:236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Wu Z, Luby-Phelps K, Bugde A, et al. Capacity for stochastic self-renewal and differentiation in mammalian spermatogonial stem cells. J Cell Biol 2009; 187:513–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31:822–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31:827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, Ma E, Doudna JA, Liu DR. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Botechnol 2013; 31:839–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Suzuki K, Yu C, Qu J, et al. Targeted gene correction minimally impacts whole-genome mutational load in human-disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cell clones. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 15:31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Lynch M. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet 2010; 26:345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Drost JB, Lee WR. Biological basis of germline mutation: comparisons of spontaneous germline mutation rates among drosophila, mouse, and human. Environ Mol Mutagen 1995; 25 (Suppl 26):48–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42Veres A, Gosis BS, Ding Q, et al. Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 15:27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Smith C, Gore A, Yan W, et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals high specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN-based genome editing in human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 15:12–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Xie W, Barr CL, Kim A, et al. Base-resolution analyses of sequence and parent-of-origin dependent DNA methylation in the mouse genome. Cell 2012; 148:816–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Valli H, Phillips BT, Shetty G, et al. Germline stem cells: toward the regeneration of spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril 2014; 101:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Singh SR, Burnicka-Turek O, Chauhan C, Hou SX. Spermatogonial stem cells, infertility and testicular cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2011; 15:468–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Miyamoto T, Hasuike S, Yogev L, et al. Azoospermia in patients heterozygous for a mutation in SYCP3. Lancet 2003; 362:1714–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Santos F, Fuente R, Mejia N, Mantecon L, Gil-Pena H, Ordonez FA. Hypophosphatemia and growth. Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Schrans-Stassen BH, van de Kant HJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM. Differential expression of c-kit in mouse undifferentiated and differentiating type A spermatogonia. Endocrinology 1999; 140:5894–5900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. CD9 is a surface marker on mouse and rat male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod 2004; 70:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Yang H, Shi L, Wang BA, et al. Generation of genetically modified mice by oocyte injection of androgenetic haploid embryonic stem cells. Cell 2012; 149:605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of testis transplantation experiments

Summary of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated single gene editing in SSCs

Summary of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing in triple genes simultaneously

Summary of SSC lines derived from expansion of single colonies or single SSCs after CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene correction of mCrygc

The off-target analysis in cured SSC lines

Summary of whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis

Summary of whole genome mutations in Line-HDR1-SC-8

Annotation of called mutations in genomic regions

Description of one exonic mutation listed in Supplementary information, Table S8

Summary of off-target sites in Line-HDR1-SC-8 from WGS data

Summary of whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGSB)

The primers and oligonucleotides used in this study

The sequences of the EGFP transgene in mice carrying CRISPR-Cas9-induced modifications.

The sequences of the Crygc gene in SSC colonies (A) and mice (B) carrying CRISPR-Cas9-induced modifications.

The sequences of the p53 gene in SSC colonies (A) and the sequences of the p53, Crygc and Exo5 genes in SSC colonies (B).

The sequences of the Crygc gene in SSC lines generated from single SSC colonies derived from electroporation of Crygc-sgRNA into Crygc−/−-SSCs.

The sequences of the Crygc gene in SSC lines generated from single SSC colonies derived from electroporation of exogenous Olig-1 (A), Olig-2 (B) into Crygc−/−-SSCs or single SSCs derived from electroporation of Oligo-1 (C) into Crygc−/−-4W-SSCs.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing rescued the mutant Crygc gene without causing CNVs.

DNA Methylation patterns were not disrupted by CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Isolation of non-EGFP haploid cells from testis reconstituted by transplantation of SSCs from Line-NHEJ-9 (upper) and Line-HDR1-8 (bottom) into recipient testes of infertile males with homozygous EGFP marker for ROSI.