Abstract

Parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor (PTH/PTHrP type 1 receptor; commonly known as PTHR1) is a family B G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that regulates skeletal development, bone turnover and mineral ion homeostasis. PTHR1 transduces stimuli from PTH and PTHrP into the interior of target cells to promote diverse biochemical responses. Evaluation of the signalling properties of structurally modified PTHR1 ligands has helped to elucidate determinants of receptor function and mechanisms of downstream cellular and physiological responses. Analysis of PTHR1 responses induced by structurally modified ligands suggests that PTHR1 can continue to signal through a G-protein-mediated pathway within endosomes. Such findings challenge the longstanding paradigm in GPCR biology that the receptor is transiently activated at the cell membrane, followed by rapid deactivation and receptor internalization. Evaluation of structurally modified PTHR1 ligands has further led to the identification of ligand analogues that differ from PTH or PTHrP in the type, strength and duration of responses induced at the receptor, cellular and organism levels. These modified ligands, and the biochemical principles revealed through their use, might facilitate an improved understanding of PTHR1 function in vivo and enable the treatment of disorders resulting from defects in PTHR1 signalling. This Review discusses current understanding of PTHR1 modes of action and how these findings might be applied in future therapeutic agents.

Introduction

Parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor (PTH/PTHrP type 1 receptor; commonly known as PTHR1) is a family B G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is expressed primarily in bone, kidney and cartilage but also in other tissues including the vasculature and certain developing organs.1 PTHR1 couples to several intracellular signalling pathways and transmits stimuli provided by two different naturally occurring polypeptide ligands: PTH, which is secreted from the parathyroid glands; and PTHrP, which is secreted from a diverse range of tissues.2 Although both PTH and PTHrP signal via the same receptor, the biological functions of the two ligands are distinct, as PTH acts in an endocrine manner on bone and kidney cells to regulate blood levels of calcium and phosphate, whereas PTHrP acts in a paracrine manner within developing tissues, such as the skeletal growth plate, to regulate cell differentiation and proliferation.2 The overall nature of the biological response resulting from activation of PTHR1, in terms of signal identity, magnitude and duration is determined by many variables, such as the structure of the bound ligand, the type of target cell and the prevailing homeostatic condition of the organism. Activation of PTHR1 in different cell types initiates distinct biochemical and cellular responses: activation of PTHR1 in osteoblastic cells and chondrocytes modulates rates of proliferation and apoptosis, and production of a variety of signalling factors involved in bone and cartilage metabolism.3,4 Conversely, activation of PTHR1 in renal tubule cells modulates the expression and function of proteins involved in transmembrane mineral ion transport.5 Regulation of the overall response to PTHR1 activation that occurs within an organism is achieved via processes operating at several levels, which include intracellular mechanisms of receptor desensitization,6,7 systemic feedback loops that control hormone release,8 and metabolic clearance and destruction mechanisms that remove the peptide hormone from the circulation.9 Despite numerous mechanisms regulating the activity of PTHR1, dysregulation can occur and cause serious physiological consequences.

This Review aims to provide a link between structural features of PTHR1 ligands and receptor function at the biochemical, cellular and organismal level. We present an initial overview of the fundamental aspects of ligand-binding and signalling mechanisms of PTHR1, highlighting the relationship between ligand structural modification and variation in PTHR1 signalling responses. We explore new findings relating to the emerging model of noncanonical PTHR1 signalling, which involves novel modes of action and termination within endosomes. The importance of such signalling mechanisms in the context of disease states in which PTHR1 function has an important role is also discussed.

PTHR1 ligand binding and signalling

Functional domains of PTH and PTHrP ligands

PTH and PTHrP exhibit similar propensities for initiating signalling through various intracellular pathways,10,11 and in many cases stimulate comparable responses in tissues when administered exo-genously.12 PTHR1 signals primarily by coupling with the GαS–adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) intracellular signalling pathway, but can also couple to the Gαq–phospholipase C (PLC) β–inositol triphosphate–cytoplasmic Ca2+–protein kinase C pathway,13 the Gα12/13–phospholipase D–transforming protein RhoA pathway,14 and the β-arrestin–extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathway.15,16 N-terminal fragments consisting of the first 34 residues of PTH and PTHrP are generally thought to contain the key functional determinants of receptor interaction present in the corresponding full-length, mature polypeptide chains, which contain 84 and 141 amino acid residues, respectively. PTH and PTHrP are distinct among the family B peptide ligands in containing extended C-terminal segments. The biological roles of these segments remain obscure, although some functional responses have been identified, such as a capacity of fragments corresponding to the C-terminal portion of PTH to induce pro-apoptotic effects in osteocytes17 and of fragments encompassing the mid-region of PTHrP, which contains a nuclear localization sequence, to induce proliferative effects on bone and vascular smooth muscle cells through an intracrine mechanism.18–20 Such effects of the C-terminal ligand fragments probably do not involve PTHR1, but rather some other receptors or protein mediators that have yet to be identified.

Two-site model of ligand binding at PTHR1

Ligand structure–activity relationship and receptor mutagenesis studies indicate that the bioactive PTH(1–34) and PTHrP(1–34) peptides each interact with PTHR1 via a two-component mechanism.21 Thus, the C-terminal portion of PTH(1–34) (approximately corresponding to residues 15–34) interacts with the amino-terminal extracellular domain of PTHR1 (site 1),22 whereas the N-terminal portion (approximately corresponding to residues 1–14) interacts with the transmembrane helices and extracellular connecting loops (site 2).23,24 The interactions with site 1 provide the majority of the energetic drive for binding,25,26 whereas contacts with site 2 induce the conformational changes in the receptor that initiate intracellular signalling.27,28 Crystallographic characterization of PTH(15–34)29 and PTHrP(12–34)30 peptides bound to the isolated extracellular domain of PTHR1 show a helix-into-cleft motif, with the α-helical ligand domain making extensive contacts with the receptor extracellular domain. Hydrophobic residues aligned along one face of the ligand helix—that is Trp23, Leu24 and Leu28 in PTH, or Phe23, Leu24 and Ile28 in PTHrP—have key roles in determining overall binding affinity for the ligand, presumably via interactions with complementary hydrophobic surfaces along the receptor cleft. Compared with that of PTH, a slight bend in the C-terminal portion of the bound PTHrP helixexists.

The interactions at site 2 are less well defined than that at site 1, as no crystal structures for this trans-membrane domain of PTHR1 have yet been reported. The recently reported crystal structures of the transmembrane domains of two other family B GPCRs, the glucagon receptor31 and the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 132 are promising developments in this regard. A large, extracellularly exposed V-shaped cavity is visible in each of these structures, which presumably accommodates the N-terminal portion of the cognate peptide ligand.33 For PTHR1, extensive studies using photoaffinity crosslinking and mutational analysis suggest that multiple residues near the N-terminus of the ligand participate in the interaction with the transmembrane domain, with the residues at positions 2, 5 and 8 (which are Val–Ile–Met in PTH and Val–His–Leu in PTHrP) having particularly important roles in binding and/or inducing signal transduction.27,34

Altered signalling of PTHR1 ligands

Pathway selective agonists and antagonists

Results from early structure–activity relationship studies on PTH have revealed that the ligand’s first few N-terminal residues have critical roles in signalling.35 These studies, therefore, provide guidance for the identification of novel PTH and PTHrP analogues with activity profiles that are different to those of the prototype peptides. Deletion of residues 1–6 from the PTH(1–34) scaffold produced analogues that no longer activate signalling via the cAMP–PKA pathway, but instead, function as competitive antagonists of PTHR1-mediated cAMP signalling.36 Further modification of the PTH(7–34) scaffold at residue position 12 produced an analogue, DTrp12-PTH(7–34), which in addition to competitively antagonizing cAMP signalling at PTHR1,37 also acts as an inverse agonist and consequently reduces basal cAMP signalling at certain constitutively active PTHR1 variants.38 Other PTH and PTHrP ligand analogues modified at residue position 1 have been developed that preferentially activate GαS-cAMP signalling over Gαq -PLC-β signalling.10,16,39,40

In addition to the antagonist and inverse agonist activities of DTrp12-PTH(7–34) on GαS–cAMP signalling, this peptide has also been reported to partially activate the β-arrestin-ERK1/2 pathway in transfected HEK-293 cells41 and, thus, functions as a so-called ‘biased agonist’.42 These initial cell-based studies were followed by in vivo experiments performed in mice lacking β-arrestin-2.41 However, in two other studies that were performed in different cell types, including PTHR1-transfected HEK-293 and Chinese hamster ovary cells, as well as the human osteoblastic cell line U2OS, no evidence was found to indicate that DTrp12-PTH(7–34) activates the β-arrestin–ERK1/2 pathway,10,43 despite the initial findings that suggested that this analogue has some ability to selectively activate β-arrestin-2 in preference to GαS–cAMP signalling. The apparent inconsistencies between these reports highlight a potential role for external factors, such as those relating to cellular context, that determine the signalling selectivity profile of any given PTH or PTHrP ligand. Indeed, certain scaffolding proteins that interact with PTHR1, and are expressed in some cell types but not in others, have been shown to alter PTHR1 signalling.44 In particular, members of the Na+/H+ exchange regulatory cofactor (NHERF) family regulate PTHR1 signalling by selectively promoting receptor coupling to the Gαq– PLC-β signalling pathway45–47 Assessment of the selectivity of ligands for PTHR1 and other GPCRs in biologically relevant cell types is, therefore, important to accurately relate a particular ligand-induced response to activation of one signalling pathway over another.

Extension of the biased-agonist concept

Ligand analogues that preferentially activate a distinct subset of the intracellular signalling responses that are usually activated by the parent ligand are known as ‘biased agonists’; these ligands are thought to achieve their selectivity by stabilizing distinct receptor conformations.42,48 By selectively activating certain pathways while not activating or inhibiting others, biased agonists can be useful to understand the contribution of specific signalling pathways to downstream responses in both the cell and the whole organism. These agonists might also enable the prospect of achieving ‘tailored’ results in vivo, such that the application of biased agonists might improve our understanding of basic receptor function and enable development of new therapeutics that have minimal adverse effects.49 Most research on the biased agonism of GPCRs has focused on connections between ligand structure and the efficacy of coupling to different intracellular effector systems. However, for PTHR1,50 as well as for several other GPCRs,51–54 new research has provided compelling evidence for the importance of ligand-directed alterations in both spatial and temporal signalling, which contributes to the overall biological response. Such alterations in the duration and cellular localization of signalling, enabled by use of ligands that stabilize specific receptor conformations, can also be considered biased agonism.55

Ligand binding to discrete PTHR1 conformations

Findings made using PTH and PTHrP ligand analogues support the notion that intracellular signalling responses activated by structurally distinct PTHR1 ligands might differ by the type of signalling pathway activated and the duration of the response, in addition to its sub-cellular localization. Initial studies comparing PTH with PTHrP ligands were prompted by the reported differences in biological function of the endogenous ligands (that is, endocrine versus paracrine), and by studies in humans, in which differences in the responses mediated by exogenously administered PTHrP(1–36) and PTH(1–34), such as an apparent reduced capacity of the former ligand to stimulate increases in blood levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and calcium, were found.56–58 Membrane binding assays developed to evaluate the affinity of ligands for PTHR1 in conformations formed upon coupling to a heterotrimeric G protein (RG conformation) or when PTHR1 is not coupled to a G protein (R0 conformation) provided the initial clues that structurally distinct PTH and PTHrP analogues can bind with altered affinities to the different receptor conformational states.59 Direct comparative studies of PTH(1–34) and PTHrP(1–36) demonstrated that although these two peptides maintain similar affinity for the RG state, they do not have the same affinity for the R0 state, with PTH(1–34) displaying a fourfold higher affinity for R0 than PTHrP(1–36).60

The functional consequences of this altered selectivity were revealed in cAMP assays. PTH(1–34) and PTHrP(1–36) had similar potencies in conventional cAMP dose-response assays (in accordance with their similar affinities for the RG state and a GαS-mediated mechanism of intracellular cAMP production). However, the duration of the responses induced by the two ligands (assessed using a time-course washout assay) was different, with PTH(1–34) showing a more prolonged response than PTHrP(1–36).60 This difference was particularly apparent when the analogues were assessed using a kinetic, Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based approach to detect changes in cellular cAMP levels at times following ‘washout’ of unbound ligand.60,61 The kinetic FRET reporter assays were performed in PTHR1-transfected HEK-293 cells, but the conclusion that PTH(1–34) forms more stable complexes with PTHR1 than PTHrP(1–36) was supported by additional evidence. Accumulation of cAMP was directly measured in an LLC-PK1 cell line (HKRK-B64), which expressed the transfected PTHR1 at relatively low levels (~90,000 receptor molecules per cell), as well by direct binding assays conducted in membranes prepared from ROS17/2.8 cells, an osteoblast-like cell line that expresses only the endogenous PTHR1.60

In general, the duration of the cAMP responses observed in the cell-based studies correlate with the different affinities that PTH(1–34) and PTHrP(1–36) exhibit for the R0 state, rather than with their affinities for the RG state, as assessed in membrane assays. As the R0 state is not coupled to a G protein and, hence, is inactive with regard to cAMP signalling, we can presume that although R0 complexes are fairly stable over time they can isomerizes to a functional G-protein-coupled state. Indeed, in additional FRET-based studies using PTHR1 and G-protein constructs fused with fluorescent proteins, the prolonged cAMP signalling induced by a ligand that binds tightly to the R0 state is accompanied by a prolonged association between PTHR1 and stimulatory GS proteins.61 The molecular basis by which PTH(1–34) forms more stable complexes with PTHR1 than PTHrP(1–36) is not well understood. Both ligands probably associate with PTHR1 via a similar two-component binding mechanism (as outlined earlier),28 and form overlapping, yet non-identical, sets of specific intermolecular contacts.30 Using the FRET approach, PTH(1–34) and PTHrP(1–36) were both shown to bind to PTHR1 with similar association kinetics.61 However, whereas PTHrP(1–36) dissociated completely from the receptor, a substantial fraction of the PTHR1–PTH(1–34) complexes remained associated over the duration of the experiment (several minutes).61 Such results support the notion that PTH(1–34) forms intrinsically more stable complexes with the receptor than PTHrP(1–36). One key structural determinant of R0 versus RG affinity that differs between PTH and PTHrP ligands can be traced to the identity of the residue at position 5; thus, replacing His5 in PTHrP(1–36) with the corresponding isoleucine of PTH markedly enhances affinity for R0 and extends the duration of the cAMP signalling response induced in target cells.60

Prolonged signalling by modified PTH analogues

The correlation between PTHR1 R0 affinity and the duration of intracellular cAMP responses observed for PTH and PTHrP analogues led to the hypothesis that PTHR1 ligands with improved R0 affinity might stimulate an even longer cAMP response than PTH(1–34). A number of such ligands were identified in a series of PTH analogues containing several side-chain modifications known to enhance receptor affinity.62,63 Compared with PTH(1–34), such modified PTH (M-PTH) analogues exhibit enhanced affinity for R0 and, as a result, induce cAMP responses in cells that last for several hours or more after initial binding.62,63 Moreover, when injected into mice, these analogues induced markedly protracted calcaemic and phosphaturic responses.63 These prolonged biological responses were not accompanied by prolonged persistence of the peptide in the bloodstream, which suggests that the prolonged responses were not due to altered pharmacokinetics but, rather, to altered receptor binding and signalling dynamics in target cells.

Interestingly, the prolonged mode of binding observed for these modified PTH ligand analogues seems to mimic, in many respects, the pseudo-irreversible mode of binding that is the mechanistic basis underlying the extended efficacies of several approved pharmaceuticals.64 Prolonged drug-target residence time, which frequently correlates with extended biological efficacy, is identified experimentally by slow dissociation of the ligand from the receptor. Prolonged drug-target residency has been demonstrated for a number of small molecule antagonist ligands that act on several members of the family A of GPCRs.65 However, this phenomenon has not generally been investigated for peptide agonists acting on members of the family B of GPCRs,66 with the exception of a 2014 study on the binding of salmon calcitonin to the human calcitionin receptor.54 The findings made with salmon calcitonin and with the long-acting PTH analogues suggest that such mechanisms of pseudo-irreversible binding and prolonged drug efficacy might extend to peptide agonists that act on members of the family B of GPCRs. Such molecules might indeed have therapeutic implications, particularly, for PTH analogues and the treatment of hypoparathyroidism.

Mechanisms of prolonged PTHR1 signalling

cAMP signalling and receptor internalization

The initial pharmacological and biological observations made with the conformationally selective long-acting PTH analogues suggested that an uncharacterized fundamental mechanism of PTHR1 action might be at play, particularly with regards to receptor trafficking and signal termination.63 Live-cell confocal microscopy studies performed in HEK-293 cells revealed that, within several minutes of initial binding, most of the PTH(1–34)–PTHR1 complexes co-localize with GαS and adenylyl cyclases in early endosomes.61 Given that cAMP signalling could still be robustly detected over the same time frame, this finding suggested an apparent temporal correlation between the persistent formation of cAMP and the bulk localization of ligand–receptor complexes to within the endosomal compartment. This finding led to the hypothesis that at least some of the cAMP signal observed in cells after initial PTH binding is the result of peptide–receptor complexes that are located in early endosomes and are functional, despite having been internalized.61 Although this model of endosomal PTHR signalling has not been unequivocally established by direct observation of cAMP production at an endosome, the model is supported by experiments in which inhibition of receptor internalization (achieved by transfecting PTHR1-expressing cells with dominant-negative variants of dynamin, a protein required for vesicle formation, or RAB5, a protein required for early endosome development) shortens the duration of the cAMP response induced by PTH(1–34).61,67

A key question that arises from the aforementioned observations made with PTH ligands and PTHR1 concerns the capacity of the ligand to remain associated with the receptor within endosomes. The persistent association of fluorescently-tagged PTH ligands and receptors observed throughout the internalization process via live-cell confocal microscopy61 suggests that the overall rate of receptor internalization is comparable to or faster than the rate of dissociation of the ligand–receptor complex. Once PTH and PTHR1 are internalized into an endosome they are confined together within the same limited volume (8 × 10–19 m3; equivalent to 800 attolitres per endosomal vesicle),68 which leads to a local concentration of ligand (2 nM) comparable to the equilibrium dissociation constant for the interaction of PTH with PTHR1 (1 nM),69 based on the assumption of one molecule of peptide per endosome. Accordingly, PTHR1 internalized with PTH is probably continually engaged by PTH within an endosome, as long as PTH retains the ability to remain bound to, and/or effectively rebind, the receptor during the early phases of endocytosis.

Modes of GPCR signalling and termination

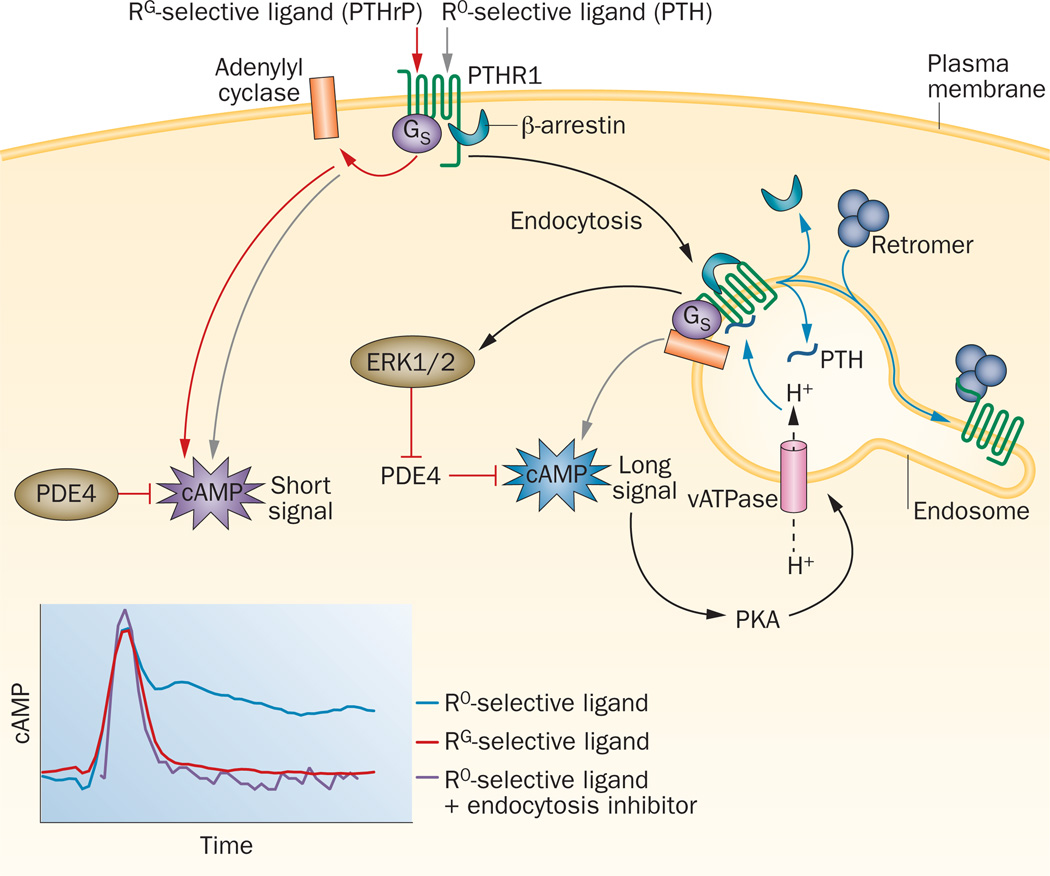

The notion that PTH ligand-induced signalling via GαS–cAMP can occur from early endosomes is contrary to the classical paradigm of GPCR regulation.70 In this classical paradigm, agonist-induced G-protein-mediated GPCR signalling is attenuated at the plasma membrane by a process that begins with phosphorylation of serine residues within the intracellular portion of the receptor by G-protein-receptor kinases. The modified serine residues promote recruitment of β-arrestins, which destabilize the interactions with G proteins, induce the dissociation of agonist, and initiate internalization by linking the receptor to the adaptor protein subunits of clathrin-coated pits. The classical model, therefore, necessitates that receptor internalization correlates temporally with the termination of G-protein signalling. Studies have shown that GPCRs other than the PTHR1, including the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor,51 the vasopressin V2 receptor52 and the α2-adrenergic receptor,53,71 can also utilize a noncanonical mode of endosomal cAMP signalling. Notably, studies of the α2-adrenergic receptor expressed in HEK-293 cells reveal that cAMP signalling from the internalized state is required to induce expression of a considerable proportion of the genes induced by isoproterenol (as shown by the effects of Dyngo, a chemical inhibitor of dynamin and thus also of receptor internalization), on the agonist-dependent gene transcription array profile.71 Moreover, in this study, the activation of a bacterial photo-inducible adenylyl cyclase (bPAC) targeted specifically to the plasma membrane stimulated expression of a smaller set of cAMP-dependent genes than that stimulated by activation of a bPAC construct targeted to the endosomal membrane.71 Such findings provide additional support for the hypothesis that endosomal cAMP production potentially provides a mechanism of biased signalling that operates at the level of subcellular localization of receptor-mediated signal generation (Figure 1).72–74 The combined results also highlight the need for further investigation into the biochemical steps and molecular events involved in regulating PTHR1 signalling after initial ligand binding and during movement of the complex along the endocytic pathway.

Figure 1.

Altered modes of cAMP signalling at PTHR1. Structurally distinct PTH and PTHrP ligands can bind preferentially to two different high affinity receptor conformations, R0 and RG, and thereby induce different modes of GαS-mediated cAMP signalling (inset, lower panel). RG-selective ligands (for example PTHrP) induce transient cAMP responses that are derived from signalling complexes localized at the plasma membrane, whereas R0-selective ligands (for example certain PTH analogues62,63) can also induce prolonged cAMP responses that are derived from complexes associated within endosomes. The internalized signalling complexes contain β-arrestin, which promotes, rather than terminates cAMP signalling by activating ERK1/2, leading to the inhibition of PDE4 enzymes.78 Termination of endosomal signalling correlates with an exchange at the complex of β-arrestin for retromer sorting proteins,75 and is promoted by vATPase-mediated vesicle acidification. The vATPases are activated by cAMP-dependent PKA, and thereby establish a negative feedback loop.67 PTHR1 activation of cAMP signalling that differs in duration and location of origin within the cell provides a potential mechanism for ligand-directed diversification of cellular responses.71–74 Abbreviations: ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; PKA, protein kinase A; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR1, PTH/PTHrP type 1 receptor; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; R0, G-protein-independent conformational state; RG, G-protein-dependent conformational state; vATPase, vacuolar H+-ATPase.

β-arrestins

The role of β-arrestins in regulating the signalling activity of PTHR1 and its internalization into endosomes was addressed in a series of kinetic studies that applied the optical approaches of FRET, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, total internal reflection fluorescence and confocal microscopy in live HEK-293 cells expressing PTHR1.75 In this study, transfecting the cells with β-arrestin-1[IV-AA] (a β-arrestin mutant protein that binds to receptors with enhanced affinity) prolonged the PTH(1–34)-induced cAMP response, compared with that in control cells. Conversely, transfection with siRNAs to reduce β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 expression shortened the duration of this response, an observation also found in osteoblast-like ROS17/2.8 cells.75 These results suggest that β-arrestin proteins can extend cAMP signalling at PTHR1 and, therefore, do not solely act to terminate signalling, as would be predicted by the canonical GPCR paradigm.

Two associated observations provide plausible mechanisms by which β-arrestins might promote, rather than terminate, PTHR1 cAMP signalling. First, U0126, an inhibitor of ERK1/2 signalling, shortened the cAMP response to PTH, whereas rolipram, an inhibitor of the cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) family extended the response.75 These findings suggest that β-arrestins might extend cAMP signalling at PTHR1 by activating ERK1/2,76 which, in turn, deactivates PDE477 and leads to an increase in the accumulation of cAMP. Second, β-arrestin-PTHR1 complexes formed following addition of a PTH agonist with high R0 affinity can undergo further association with Gβγ to yield a ternary complex of PTHR1-β-arrestin-Gβγ; this finding suggests that the docked Gβγ might act in a catalytic manner to promote recoupling of GαS and thereby prolong cAMP signalling.78

Termination of PTHR1-mediated cAMP signalling

The evidence suggesting that β-arrestin association can contribute to longer cAMP signalling by PTH-PTHR1 complexes has prompted additional studies to explore mechanisms specifically responsible for signal termination. By tracking the subcellular movements of fluorescently tagged proteins, termination of cAMP production from PTHR1 complexes was found to correlate temporally and spatially with the dissociation of β-arrestin from receptor complexes within the endosome.75 Moreover, dissociation of β-arrestin coincides with association of PTHR1 complexes with the retromer complex, a pentameric protein assembly involved in later-stage endosomal sorting and retrograde trafficking of vesicles through the Golgi and back to the plasma membrane.75 The exchange of β-arrestin for the retromer complex coincided with, and was perhaps promoted by, the activation of a negative feedback loop that involved cAMP, PKA and the vacuolar ATPase (vATPase) proton pump, which has a major role in endosome acidification.67 Consequently, the intracellular cAMP produced by functional PTHR1 complexes activates PKA, which then phosphorylates and activates vATPase proton pumps, which, in turn, acidify the endosome in a progressive fashion as it moves along the endocytic pathway67 Such endosomal acidification generally promotes dissociation of ligands from their internalized receptors79 and would, therefore, be expected to cause dissociation of PTH–PTHR1 complexes and terminate their signalling. Binding studies performed with isolated membranes containing PTHR1 confirmed that radiolabelled PTH(1–34)–PTHR1 complexes dissociate when the buffer is reduced to pH 5.5, which is approximately the pH of later-stage PTHR1-containing endosomes. In complementary studies using HEK-293 cells, inhibition of endosomal acidification by bafilomycin A1 treatment (a vATPase inhibitor) increases the duration of PTH–PTHR1 complex associ ation and the duration of cAMP signalling. Analogous experiments in ROS17/2.8 cells showed that bafilo mycin A1 also promotes prolongation of PTH(1–34)-induced cAMP responses in this osteoblastic cell model.67 In total, these findings support a model in which at least some of the cAMP signal generated by PTHR1, as activated by agonist ligands, including PTH(1–34), derives from noncanonical endosomal signalling. In this model, β-arrestin acts to prolong signalling within the endosome by providing a scaffolding function that helps maintain or enable successive rounds of GαS–protein complex assembly and activation. Termination ultimately results from the exchange of β-arrestin for retromer coinciding with PKA-vATPase-promoted acidification of endosomes.

Further characterization of the biochemical mechanisms that facilitate and regulate PTHR1-mediated GαS–cAMP signalling within endosomes, and the biological consequences of such signalling for PTHR1, is needed. Endosomal cAMP signalling might potentially have a role in differentiating the biological actions of PTH from those of PTHrP, and possibly helps explain why in clinical testing PTH(1–34) stimulates more enduring increases in serum levels of 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3, calcium and bone resorption markers than does PTHrP(1–36).56–58 However, additional studies linking differences in downstream actions of PTH and PTHrP (at the proteomic and genomic levels) in diverse target cells to differences in endosomal signalling are required to test this concept. How these mechanisms overlap with or differ from those used by other GPCRs, both family B receptors and those of other GPCR families, will also be of interest. Observations that support endosomal G-protein-mediated signalling by several dissimilar GPCRs74,80 suggest that this mode of signalling might not be an atypical feature of only a few GPCRs, but is found more broadly in the GPCR superfamily, and perhaps provides a means to extend and diversify receptor functionality.74 Conceivably, spatiotemporal differences in PTHR1 signalling properties, which might arise in part from altered degrees of ligand sensitivity to endosomal acidification, could enable this receptor to mediate its diverse catalogue of biological actions. These actions include responding to two distinct endogenous ligands (PTH and PTHrP) and the regulation of multiple processes in widely different target cells, such as osteoblasts, renal tubule cells and developing chondrocytes in skeletal growth plates. Future efforts to characterize and modulate the endosomal signalling capacity of PTHR1 at the ligand level might identify agents with useful therapeutic profiles, especially for treating hypoparathyroidism or osteoporosis.

PTHR1 in disease

PTHR1 function and pathological diversity

Dysregulation of PTHR1 activity occurs via a number of mechanisms and can lead to diverse pathologies (Table 1). PTHR1 is highly expressed in bone, kidney and growth plates, and in other tissues is expressed at lower levels at various times throughout development.1 PTHR1 expression in adult animals in bone and in the kidney is critically associated with homeostatic maintenance of blood calcium levels via the actions of PTH released from the parathyroid gland.8 This function is quite distinct from that mediated by PTHR1 in developing tissues, in which the regulation of proliferation and differentiation of primordial cells, such as chondrocytes in skeletal growth plates, and those leading to organogenesis of skin, mammary glands and teeth is the main function.81 Fetal expression of PTHR1 is linked both spatially and temporally with expression of PTHrP, which is consistent with the paracrine function of this ligand to stimulate precisely timed morphogenic responses between neighboring cells during development.82,83

Table 1.

Diseases associated with PTHR1 signalling

| Disease | Biological cause* | Physiological manifestation |

Current treatment | Prospective treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blomstrand’s lethal chondroplasia85 |

Abrogation of PTHR1 function by homozygous mutation in PTHR1 (Pro132Leu or nonsense mutation) |

Advanced endochondral bone formation Prenatal mortality |

None | None |

| Ollier’s disease86 | Heterozygous expression of inactive PTHR1 variants (Arg150Cys and other variants) |

Development of cartilaginous lesions and tumours in and around bone |

None | None |

| Familial primary failure of tooth eruption87 |

Heterozygous expression of inactive PTHR1 variants (Pro132Leu, Arg174Cys and other variants) |

Premature ceasing of posterior tooth eruption in children and adolescents |

None | None |

| Jansen’s metaphyseal chondroplasia88,89 |

Constitutive cAMP signalling at PTHR1 from heterozygous mutation in PTHR1 which yields receptor variants with mutations in transmembrane helices 2, 6 or 7 (His223Arg, Thr410Pro or Ile458Arg, respectively) |

Short limbed dwarfism Hypercalcaemia Hypophosphataemia |

None | Inverse agonists of constitutive PTHR1 signalling38,91 |

| Eiken syndrome90 | Alteration in PTHR1 function by homozygous nonsense mutation in PTHR1 (Arg485stop) |

Retarded ossification Epiphyseal dysplasia |

None | Inverse agonists of constitutive PTHR1 signalling38,91 |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism92 |

Oversecretion of PTH by parathyroid glands causes excessive PTHR1 activation |

Hypercalcaemia Kidney stones |

Surgical removal of offending PTH gland | Competitive antagonists of PTHR1 signalling97,98 |

| Humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy93 |

Oversecretion of PTHrP by cancer cells causes excessive PTHR1 activation (observed in 20–30% of patients with cancer) |

Hypercalcaemia Cachexia |

Bisphosphonates Denosumab in bisphosphonate-resistant cases | Neutralizing PTHrP antibodies94–96 Competitive PTHR1 antagonists |

| Brachydactyl type E99 | Heterozygous mutation of PTHLH resulting in expression of PTHrP variants (Leu44Pro and Leu60Pro, corresponding to positions 8 and 24 of mature PTHrP) with reduced activity |

Short metacarpals and metatarsals resulting in small hands and feet |

None | None |

| Hypoparathyroidism100–103 | Surgical damage to or removal of parathyroid glands, mutation in calcium sensing receptor expressed on parathyroid glands, defective PTH precursor processing |

Hypocalcaemia Tetany Numbness |

Oral calcium Vitamin D Daily PTH (can be administered separately or together) |

Long-acting PTH derivatives62,63,104 |

| Osteoporosis105–107,111,112 | Imbalance between bone resorption and bone building processes |

Reduction in BMD, alterations in skeletal architecture and increased fracture frequency |

Bisphosphonates Denosumab PTH |

Analogues of PTHR1 ligands with weak calcium mobilization activity (PTHrP, abaloparatide)112,115 |

Mutation or ligand.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR1, PTH/PTHrP type 1 receptor; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein.

As a consequence of such diverse biological involvement, dysfunctional and unregulated signalling at PTHR1 is associated with several disorders in humans (Table 1). Since the original identification and assignment of PTHR1 as the cognate receptor for PTH and PTHrP in the early 1990s,13,84 researchers have investigated how regulated, receptor-mediated signalling responses promote homeostasis, and how disruption of these processes causes disease. Mechanistic studies of PTHR1 signalling described in the previous sections provide an expanded framework in which the efficacy of various approaches for treating diseases of PTHR1 dysregulation can be evaluated. Improved understanding of the connections between PTHR1 ligand structure and alterations in ligand activity might thus facilitate efforts to develop new receptor ligands tailored to treat receptor-associated diseases, particularly hypoparathyroidism and osteoporosis.

Mutations in PTHR1

Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding PTHR1 result in receptor variants that are poorly expressed or are unable to efficiently bind and/or respond to PTH or PTHrP. Homozygous expression of inactive PTHR1 variants is associated with Blomstrand’s neonatal lethal chondroplasia (Table 1).85 Heterozygous expression of such receptor variants is also observed in enchondromas in patients with Ollier’s disease86 and is associated with familial primary failure of tooth eruption (Table 1).87 Gain-of-function receptor variants for which ligand binding is not required for activation of signal transduction have also been identified.88 Heterozygous expression of such constitutively active PTHR1 variants causes a rare, dominant disorder known as Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia (Table 1).89 Eiken syndrome, a recessive disorder observed solely within one consanguineous family, manifests as a phenotype with some similarities to Jansen’s metaphyseal chondroplasia and is proposed to result from expression of a PTHR1 variant with elevated constitutive receptor activity (Table 1).90

In some cases, the pathological conditions resulting from a PTHR1 mutation might be amenable to treatment with agents that normalize receptor function. In particular, PTHR1 ligand analogues, such as DTrp12-PTH(7–34), which can inhibit basal signalling at constitutively active receptors and, therefore, function as inverse agonists38,91 could potentially be helpful in preventing and/or correcting the developmental and homeostatic abnormalities occurring in patients with Jansen’s metaphyseal chondroplasia.

Overabundance of PTHR1 ligand

Abnormal physiological states caused by elevated PTHR1 signalling are not usually linked to mutations within the gene encoding the receptor; a more common source of receptor hyperactivation results from overproduction of PTH or PTHrP. Aberrant function of chief cells in the parathyroid gland can result in overproduction of PTH, which leads to primary hyperparathyroidism (Table 1).92 Some types of cancerous cells also overproduce PTHrP that is released into the circulation, which results in a disorder known as humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy (Table 1).93

Blocking the activity of excess circulating PTH or PTHrP at PTHR1 should ameliorate the pathological consequences of primary hyperparathyroidism and humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy. This objective has been pursued using agents that bind to PTHR1 ligands and prevent their association with the receptor (that is, antibodies directed against PTHrP) or agents that bind to the receptor and prevent the binding and activity of agonists (that is, competitive antagonists of PTHR1 signalling). PTHrP antibodies have been shown to reduce serum levels of calcium in mice transplanted with PTHrP-producing tumours94 and have been investigated as potential therapeutic modalities for treating humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy.95,96

Competitive antagonists of PTHR1 signalling, such as DTrp12-PTH(7–34) are of interest for their potential activity in treating primary hyperparathyroidism induced hypercalcaemia. Analogues of DTrp12-PTH(7–34) can inhibit PTH-induced cAMP responses in cells37 and calcaemic responses stimulated by exogenous PTH(1–34) in rats.97 However, trials in patients with hypercalcaemia owing to primary hyperparathyroidism revealed a complete lack of efficacy for such a DTrp12-PTH(7–34) analogue in reversing hypercalcaemia.98 The reasons for this lack of efficacy in patients is unclear; however, the prevailing high levels of endogenous PTH, as well as a capacity of the agonist to form persistent complexes with PTHR1 and engage in endosomal signalling, would probably counteract the processes of competitive inhibition. Indeed, in the rodent studies in which DTrp12-PTH(7–34) inhibited PTH(1–34)-induced calcaemic responses, the animals were rendered surgically deficient for endogenous PTH, and effective inhibition required that the antagonist be administered 1–2 h before administration of the PTH(1–34) agonist and at a 10–200-fold molar excess.97

Deficiency of PTHR1 ligand

PTHR1 signalling deficiency, typically caused by mutation-induced alterations in PTHrP structure or reduced concentrations of circulating PTHR1 ligands, is associated with specific anatomical and physiological disorders. Specific mutations in PTHLH (which encodes PTHrP) result in an autosomal dominant developmental disorder known as brachydactyly type E (Table 1).99 The presence of abnormally low levels of endogenous PTH, known as hypoparathyroidism, is caused by deficient release of bioactive PTH by the parathyroid glands in response to low levels of blood calcium (Table 1).100 The use of PTH peptides as hormone-replacement therapy holds considerable promise for the treatment of hypoparathyroidism,101 as recombinant PTH(1–84)—known as Natpara—was approved by the FDA in the USA as the first PTH-based therapy for this disease.102 However, a substantial challenge for any treatment of hypoparathyroidism is the need to maintain blood calcium levels at normalized steady-state levels, continuously throughout the day and in the face of fluctuating dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D3, to mimic the homeostatic conditions occurring in people who have normal parathyroid function. The overall effectiveness of the hormone-replacement approach, which typically involves a daily subcutaneous injection of an unmodified PTH peptide,101 can therefore be limited by the relatively short bloodstream half-life of PTH peptides, such that undesired variations in blood calcium levels might occur. PTH(1–34) delivery via an implanted pump mechanism has been investigated as one means to overcome this limitation.103

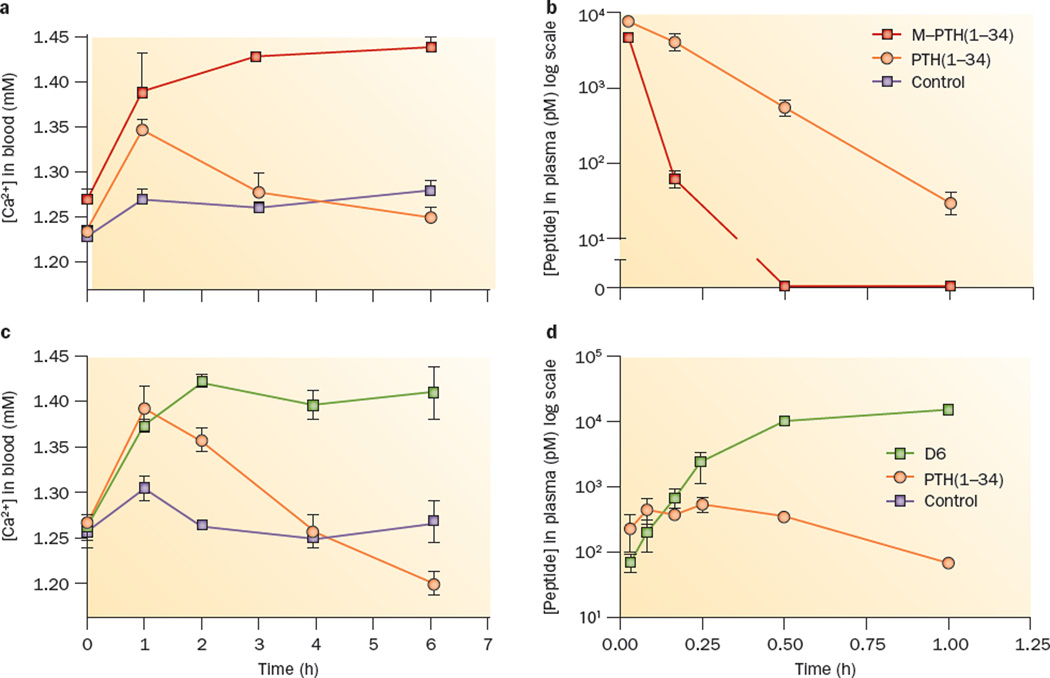

The development of long-acting PTH analogues represents another potential approach for treating hypoparathyroidism, for which agents that can normalize blood calcium levels for extended periods, if not continuously, are needed. Analogues of PTH, such as M-PTH(1–34), that have prolonged bioactivity in cells and animals by targeting the R0 conformation of PTHR1 might be useful in this regard. M-PTH(1–34) induces prolonged calcaemic responses in animals (Figure 2a),63 effects that are not due to prolonged bioavailability in the bloodstream (Figure 2b), but rather to pseudo-irreversible binding to PTHR1 (specifically the R0 conformation) in target tissues. A related, R0-targeting PTH/PTHrP hybrid peptide derivative, called long-acting PTH (LA-PTH), has particularly prolonged calcaemic actions in animals, and is therefore of considerable interest as a potential treatment alternative for hypo-parathyroidism.62 However, whether such a ligand can achieve the desired normalization of calcium levels, particularly given the challenges posed by variations in dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D3 remains to be proven.

Figure 2.

Distinct mechanisms of prolonged PTH analogue action in vivo. Both the receptor conformation-selective PTH analogue, M-PTH(1–34), and the backbone-modified, stabilized PTH analogue, D6, stimulate prolonged calcaemic responses when injected into mice as compared with unmodified PTH(1–34), but the underlying mechanisms are distinct, as reflected by markedly different pharmacokinetic profiles. Injection with either a | M-PTH(1–34) or c | D6 results in an increase in blood Ca2+ concentrations that persists longer than the response induced by an identical dose of PTH(1–34); however, b | M-PTH(1–34) disappears more rapidly from the bloodstream than does PTH(1–34) (intravenous injection), whereas d | D6 disappears more slowly than does PTH(1–34) (subcutaneous injection). These results can best be explained by the capacity of M-PTH(1–34) to bind in a pseudo-irreversible fashion to a specific PTHR1 conformation (R0) in target cells, and to an enhanced resistance of D6 to degradation by systemic proteases. Blood concentrations of PTH ligands were determined by cAMP-based bioassays; data are means ± SEM. Abbreviations: D6, backbone-modified PTH analogue; M–PTH(1–34), modified parathyroid hormone (1–34); PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR1, PTH/PTHrP type 1 receptor; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; R0, G-protein-independent conformational state. Panels a and b modified with permission from The National Academy of Sciences © Okazaki, M. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16525–16530 (2008). Panels c and d modified with permission from NPG © Cheloha, R. W. et al. Nat. Biotech. 32, 653–655 (2014).

An alternative PTH ligand-based strategy for achieving prolonged actions in vivo involves the introduction of structural modifications to the PTH(1–34) ligand that fortify the peptide scaffold against metabolic breakdown by endogenous protease enzymes. A series of PTH analogues have been generated that contain a number of β-amino acid substitutions that extend the peptide backbone by one methylene unit at each substituted position while leaving the residue side chain unaltered. A number of these peptides have receptor recognition properties that are comparable to that of natural PTH, while also exhibiting enhanced stability in the presence of isolated proteases.104 One such backbone-modified PTH analogue (known as D6) induced a long-lasting calcaemic response in mice (Figure 2c), which was likely facilitated by the substantially prolonged bloodstream bioavailability of this derivative compared with PTH(1–34) (Figure 2d).104 This strategy of introducing stability-enhancing backbone modifications into PTH ligands, and that of selectively targeting a ligand analogue to a specific PTHR1 conformation (that is, R0), offer complementary approaches for identifying agents that induce protracted responses through PTHR1. Combining conformation-selective PTHR1 targeting and stability-enhancing backbone modifications could conceivably yield PTH derivatives with even more prolonged bioactivity profiles, and increased efficacy in maintaining steady-state blood calcium levels than derivatives identified using either approach alone for use in patients with PTH-deficiency disease.

Treating osteoporosis by activating PTHR1

Osteoporosis, which affects >40 million people in the USA, is the most common disorder treated with PTHR1-based therapies.105,106 Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone mass and altered bone microarchitecture, which results in an increased frequency of fractures (Table 1). Antiresorptive agents that inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, such as bisphosphonates, are the most common therapeutics used for treating osteoporosis. However, these agents cannot restore bone mass or bone structure. PTH(1–34) (commonly known as teriparatide) can stimulate restoration of bone mass and is approved for the treatment of osteoporosis via once daily subcutaneous injections.106 One limitation of PTH-based osteoporosis therapies is that hypercalcaemia can occur.107 Such hypercalcaemia reflects the capacity of PTH administration to modulate the tight coupling of anabolic and catabolic processes in bone, as well as to stimulate the rates of renal calcium reabsorption and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production.

As PTHR1-mediated signalling through the cAMP–PKA pathway is associated with anabolic effects in bone tissue,108 connections between the duration of cAMP signal generation, stimulation of extracellular calcium mobilization and promotion of bone anabolism are of particular interest from a therapeutic perspective. Consequently, the observation that ligands that tightly bind the R0 state of PTHR1 stimulate prolonged cAMP responses in cell-based assays and, ultimately, stimulate enduring hypercalcaemia and net resorption of bone when administered in mice is of considerable therapeutic importance.63 A mechanistic interpretation of these findings in the context of intact bone tissue is complicated by an incomplete characterization of the signalling and regulatory steps that connect cAMP formation to processes that directly control bone anabolism and catabolism. Future studies to evaluate the link between temporal variations in the duration of cAMP signalling and the strength of downstream responses that promote bone anabolism (such as, growth factor production, intercellular signalling molecule production and signalling through the Wnt pathway109) might help in unravelling the paradox of the divergent effects of intermittent versus continuous PTH administration110 and enable the design of PTH-based therapies with fewer adverse effects.

Agents that stimulate bone anabolism via PTHR1 signalling without also promoting bone resorption and hypercalcaemia could have improved therapeutic utility, but the mechanistic basis by which such an agent might be derived remains largely unknown.111 The development of biased agonists of PTHR1 signalling could be one such approach. Surprisingly, DTrp12-PTH(7–34), which shows negligible activity in inducing G-protein-mediated cellular responses in PTHR1-expressing cells, can induce anabolic bone responses in mice without inducing bone resorption via a β-arrestin-dependent mechanism.41 The utility of any such β-arrestin-based biased agonist for PTHR1 as an osteoporosis therapy remains to be established.43,112

Application of agents that have altered durations of action at PTHR1 by selectively targeting specific receptor conformations might be another means to promote bone anabolism without inducing excessive bone catabolism. This hypothesis seems especially attractive given the tendency of continuous PTH exposure to favour catabolic responses in bone, whereas intermittent PTH exposure favours anabolic responses at bone.111 In this regard, it is intriguing that PTHrP binds more weakly than PTH to the R0 state of PTHR1 and induces briefer biological responses, despite equivalent binding to the RG receptor state and identical cAMP signalling potencies.60,61 Subcutaneous injection of PTHrP(1–36) stimulated substantial bone growth with minimal induction of bone resorption and hypercalcaemia in a small (n = 41) clinical study.113 A phase III clinical trial comparing the bone anabolic properties of an analogue of PTHrP(1–34), called abaloparatide, to PTH(1–34) (teriparatide) was completed in 2015.114 In this trial, abaloparatide stimulated bone anabolic responses that were comparable to or stronger than those seen with teriparatide, but with a significantly reduced frequency of hypercalcaemia.114 In vitro studies show that abaloparatide binds even more weakly than PTHrP to the PTHR1 R0 receptor state, but retains high affinity for the RG state and has good cAMP bioactivity.115 This reduced R0 PTHR1 affinity might contribute to the weak calcium mobilization activity reported for abaloparatide in clinical trials. These findings underscore the potential therapeutic utility of PTH or PTHrP ligand analogues that have receptor conformation-selective binding profiles, and provide encouragement for identifying new analogues with even greater selectivity.

Conclusions

PTHR1 function is indispensable for proper tissue development and maintenance of mineral ion homeostasis in humans. Efforts to characterize how PTHR1 performs these essential functions have provided mechanistic insights and have prompted a re-evaluation of how, where and when the signals from this GPCR are generated. New PTH ligand analogues have been developed that promote prolonged signalling responses by binding in a pseudo-irreversible fashion to a G-protein-independent (R0) PTHR1 conformation. Signalling mechanisms observed for such analogues have been difficult to reconcile with the classical model of ligand-stimulated initiation and termination of GPCR-mediated cAMP generation that occurs exclusively at the plasma membrane and suggests that PTHR1 signalling can also occur within endosomes. The extent to which such internalized signalling mechanisms might contribute to the biological responses mediated by the two naturally occurring ligands that activate PTHR1—PTH and PTHrP—in normal physiology and during disease states remain to be established. Development of new PTH analogues with structural modifications in the peptide backbone that reduce protease sensitivity and prolong peptide bioavailability in the bloodstream offers another approach for evolving the therapeutic utility of PTH ligands. These ongoing efforts to optimize the PTH ligand scaffold and define mechanisms of binding and signalling at PTHR1 should enable a better understanding of how this peptide hormone– GPCR system functions in normal physiology and how this system can be pharmacologically modulated to produce new therapeutic agents for diseases such as hypoparathyroidism and osteoporosis.

Key points.

-

▪

Parathyroid hormone (PTH)/parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) receptor (PTHR1) mediates the biological actions of two endogenous ligands, PTH and PTHrP and has key roles in regulating blood calcium levels and tissue development

-

▪

PTH and PTHrP interact with PTHR1 through similar, although not identical mechanisms, and preferentially stabilize distinct receptor conformations

-

▪

Certain structurally distinct PTH and PTHrP ligand analogues, which stabilize distinct receptor conformations, induce altered signalling responses that differ in signal type and duration

-

▪

Prolonged signalling by certain PTH ligand analogues correlates temporally with ligand-receptor complexes located in endosomes, which suggests mechanisms of signal generation and termination distinct from those described by traditional G-protein-coupled receptor models

-

▪

Consideration of ligand-based mechanisms that control signal duration provide insight into the processes of receptor dysfunction, as wells as guidance for addressing PTHR1-related diseases

-

▪

Identification and incorporation of specific structural features that promote or prevent long-lasting biological responses hold promise for the design of treatments for hypoparathyroidism and osteoporosis, respectively

Acknowledgements

R.W.C. was supported in part by a Biotechnology Training Grant from NIGMS (T32 GM008349). Work in the authors laboratories was supported by NIH grants R01-GM056414 (S.H.G.), RO1-DK087688, R01-DK102495 (J.-P.V.) and P01-DK11794 (T.J.G.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

All authors researched data for the article, provided substantial contributions to discussions of the content, wrote the article and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Contributor Information

Ross W. Cheloha, Department of Chemistry, 1101 University Avenue, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA

Samuel H. Gellman, Department of Chemistry, 1101 University Avenue, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA

Jean-Pierre Vilardaga, Laboratory for GPCR Biology, Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA.

Thomas J. Gardella, Endocrine Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, 50 Blossom Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA

References

- 1.Urena P, et al. Parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor messenger ribonucleic acids are widely distributed in rat tissues. Endocrinology. 1993;133:617–623. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.2.8393771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vilardaga JP, Romero G, Friedman PA, Gardella TJ. Molecular basis of parathyroid hormone receptor signaling and trafficking: a family B GPCR paradigm. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0465-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kousteni S, Bilezikian JP. The cell biology of parathyroid hormone in osteoblasts. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2008;6:72–76. doi: 10.1007/s11914-008-0013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jilka RL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone. 2007;40:1434–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaine J, Chonchol M, Levi M. Renal control of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium homeostasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015;10:1257–1272. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09750913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tawfeek HA, Qian F, Abou-Samra AB. Phosphorylation of the receptor for PTH and PTHrP is required for internalization and regulates receptor signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:1–13. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohse MJ. Molecular mechanisms of membrane-receptor desensitization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1179:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90139-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown EM. Extracellular Ca2+ sensing, regulation of parathyroid cell function, and role of Ca2+ and other ions as extracellular (first) messengers. Physiol. Rev. 1991;71:371–411. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habener JF, Rosenblatt M, Potts JT. Parathyroid hormone: biochemical aspects of biosynthesis, secretion, action, and metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 1984;64:985–1053. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.3.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cupp ME, Nayak SK, Adem AS, Thomsen WJ. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related peptide domains contributing to activation of different PTH receptor-mediated signaling pathways. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013;345:404–418. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.199752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean T, et al. Mechanisms of ligand binding to the PTH/PTHrP receptor: selectivity of a modified PTH(1–15) radioligand for GαS-coupled receptor conformations. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006;20:931–942. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz MJ, et al. Direct comparison of sustained infusion of human parathyroid hormone-related protein-(1–36) [HPTHrP-(1–36)] versus HPTH-(1–34) on serum calcium, plasma 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and fractional calcium excretion in healthy human volunteers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:1603–1609. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abousamra AB, et al. Expression cloning of a common receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide from rat osteoblast-like cells: a single receptor stimulates intracellular accumulation of both cAMP and inositol trisphosphates and increases intracellular free calcium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:2732–2736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh AT, Gilchrist A, Voyno-Yasenetskaya T, Radeff-Huang JM, Stern PH. Gα12/Gα13 subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins mediate parathyroid hormone activation of phospholipase D in UMR-106 osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2171–2175. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Syme CA, Friedman PA, Bisello A. Parathyroid hormone receptor trafficking contributes to the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases but is not required for regulation of cAMP signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11281–11288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gesty-Palmer D, et al. Distinct β-arrestin- and G protein-dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor-stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10856–10864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Divieti P, Geller AI, Suliman G, Juppner H, Bringhurst FR. Receptors specific for the carboxyl-terminal region of parathyroid hormone on bone-derived cells: determinants of ligand binding and bioactivity. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1863–1870. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toribio RE, et al. The midregion, nuclear localization sequence, and C terminus of PTHrP regulate skeletal development, hematopoiesis, and survival in mice. FASEB J. 2010;24:1947–1957. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Miguel F, et al. The C-terminal region of PTHrP, in addition to the nuclear localization signal, is essential for the intracrine stimulation of proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4096–4105. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao D, et al. Severe growth retardation and early lethality in mice lacking the nuclear localization sequence and C-terminus of PTH-related protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20309–20314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805690105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergwitz C, et al. Full activation of chimeric receptors by hybrids between parathyroid hormone and calcitonin. Evidence for a common pattern of ligand-receptor interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26469–26472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee C, et al. Role of the extracellular regions of the parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor in hormone binding. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1488–1495. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.4.7523099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardella TJ, et al. Determinants of [Arg2] PTH-(1–34) binding and signaling in the transmembrane region of the parathyroid hormone receptor. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1186–1194. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.3.8070362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luck MD, Carter PH, Gardella TJ. The (1–14) fragment of parathyroid hormone (PTH) activates intact and amino-terminally truncated PTH-1 receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 1999;13:670–680. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caulfield MP, et al. The bovine renal parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor has equal affinity for two different amino acid sequences: the receptor-binding domains of PTH and PTH-related protein are located within the 14–34 region. Endocrinology. 1990;127:83–87. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jüppner H, et al. The extracellular amino-terminal region of the parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor determines the binding affinity for carboxyl-terminal fragments of PTH-(1–34) Endocrinology. 1994;134:879–884. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.2.8299582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimizu M, Carter P, Gardella T. Autoactivation of type 1 parathyroid hormone receptors containing a tethered ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19456–19460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro M, Nikolaev VO, Palm D, Lohse MJ, Vilardaga JP. Turn-on switch in parathyroid hormone receptor by a two-step parathyroid hormone binding mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16084–16089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503942102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pioszak AA, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of parathyroid hormone by its G protein-coupled receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5034–5039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pioszak AA, Parker NR, Gardella TJ, Xu HE. Structural basis for parathyroid hormone-related protein binding to the parathyroid hormone receptor and design of conformation-selective peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:28382–28391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siu FY, et al. Structure of the human glucagon class B G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2013;499:444–449. doi: 10.1038/nature12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollenstein K, et al. Structure of class B GPCR corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1. Nature. 2013;499:438–443. doi: 10.1038/nature12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollenstein K, et al. Insights into the structure of class B GPCRs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu M, Potts JJ, Gardella T. Minimization of parathyroid hormone: novel amino-terminal parathyroid hormone fragments with enhanced potency in activating the type-1 parathyroid hormone receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:21836–21843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909861199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goltzman D, Peytremann A, Callahan E, Tregear GW, Potts JT., Jr Analysis of the requirements for parathyroid hormone action in renal membranes with the use of inhibiting analogues. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:3199–3203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doppelt SH, et al. Inhibition of the in vivo parathyroid hormone-mediated calcemic response in rats by a synthetic hormone antagonist. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:7557–7560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chorev M, et al. Modifications of position 12 in parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone related protein: toward the design of highly potent antagonists. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1580–1586. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardella TJ, et al. Inverse agonism of amino-terminally truncated parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related peptide (PThrP) analogs revealed with constitutively active mutant PTH/PTHrP receptors. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3936–3941. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bisello A, et al. Selective ligand-induced stabilization of active and desensitized parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor conformations. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38524–38530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takasu H, Gardella TJ, Luck MD, Potts JT, Bringhurst FR. Amino-terminal modifications of human parathyroid hormone (PTH) selectively alter phospholipase C signaling via the type 1 PTH receptor: implications for design of signal-specific PTH ligands. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13453–13460. doi: 10.1021/bi990437n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gesty-Palmer D, et al. A β-arrestin-biased agonist of the parathyroid hormone receptor (PTH1R) promotes bone formation independent of G protein activation. Sci. Transl Med. 2009;1 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000071. 1ra1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wisler JW, Xiao K, Thomsen AR, Lefkowitz RJ. Recent developments in biased agonism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;27:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Lee MM, et al. β-arrestin-biased signaling of PTH analogs of the type 1 parathyroid hormone receptor. Cell Signal. 2013;25:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahon MJ. The parathyroid hormone receptorsome and the potential for therapeutic intervention. Curr. Drug Targets. 2012;13:116–128. doi: 10.2174/138945012798868416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahon MJ, Donowitz M, Yun CC, Segre GV. Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 directs parathyroid hormone 1 receptor signalling. Nature. 2002;417:858–861. doi: 10.1038/nature00816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, et al. Na/H exchanger regulatory factors control parathyroid hormone receptor signaling by facilitating differential activation of Gα protein subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:26976–26986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ardura JA, Friedman PA. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor function by Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011;63:882–900. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:373–386. doi: 10.1038/nrd3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Violin JD, Crombie AL, Soergel DG, Lark MW. Biased ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors: promise and progress. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vilardaga JP, Gardella TJ, Wehbi VL, Feinstein TN. Non-canonical signaling of the PTH receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;33:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calebiro D, et al. Persistent cAMP signals triggered by internalized G-protein-coupled receptors. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feinstein TN, et al. Noncanonical control of vasopressin receptor type 2 signaling by retromer and arrestin. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:27849–27860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Irannejad R, et al. Conformational biosensors reveal GPCR signalling from endosomes. Nature. 2013;495:534–538. doi: 10.1038/nature12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreassen KV, et al. Prolonged calcitonin receptor signaling by salmon, but not human calcitonin, reveals ligand bias. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luttrell LM. Minireview: more than just a hammer: ligand ‘bias’ and pharmaceutical discovery. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014;28:281–294. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horwitz MJ, Tedesco MB, Gundberg C, Garcia-Ocana A, Stewart AF. Short-term, high dose parathyroid hormone-related protein as a skeletal anabolic agent for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:569–575. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horwitz MJ, et al. Continuous PTH and PTHrP infusion causes suppression of bone formation and discordant effects on 1,25(OH)2vitamin D. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005;20:1792–1803. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horwitz MJ, et al. A comparison of parathyroid hormone-related protein (1–36) and parathyroid hormone (1–34) on markers of bone turnover and bone density in postmenopausal women: the PrOP study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28:2266–2276. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoare SR, Gardella TJ, Usdin TB. Evaluating the signal transduction mechanism of the parathyroid hormone 1 receptor. Effect of receptor-G-protein interaction on the ligand binding mechanism and receptor conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:7741–7753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dean T, Vilardaga JP, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Altered selectivity of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related protein (PTHrP) for distinct conformations of the PTH/PThrP receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008;22:156–166. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrandon S, et al. Sustained cyclic AMP production by parathyroid hormone receptor endocytosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:734–742. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maeda A, et al. Critical role of parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor-1 phosphorylation in regulating acute responses to PTH. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:5864–5869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301674110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okazaki M, et al. Prolonged signaling at the parathyroid hormone receptor by peptide ligands targeted to a specific receptor conformation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:16525–16530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808750105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swinney DC. Biochemical mechanisms of drug action: what does it take for success? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:801–808. doi: 10.1038/nrd1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Copeland RA, Pompliano DL, Meek TD. Drug-target residence time and its implications for lead optimization. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:730–739. doi: 10.1038/nrd2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo D, Hillger JM, Ijzerman AP, Heitman LH. Drug-target residence time—a case for G protein-coupled receptors. Med. Res. Rev. 2014;34:856–892. doi: 10.1002/med.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gidon A, et al. Endosomal GPCR signaling turned off by negative feedback actions of PKA and V-ATPase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:707–709. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sonawane ND, Szoka FC, Jr, Verkman AS. Chloride accumulation and swelling in endosomes enhances DNA transfer by polyamine–DNA polyplexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44826–44831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoare SR, Usdin TB. Quantitative cell membrane-based radioligand binding assays for parathyroid hormone receptors. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 1999;41:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(99)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of β-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:455–465. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsvetanova NG, von Zastrow M. Spatial encoding of cyclic AMP signaling specificity by GPCR endocytosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:1061–1065. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calebiro D, Maiellaro I. cAMP signaling microdomains and their observation by optical methods. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;8:350. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baillie GS. Compartmentalized signalling: spatial regulation of cAMP by the action of compartmentalized phosphodiesterases. FEBS J. 2009;276:1790–1799. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsvetanova NG, Irannejad R, von Zastrow M. G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling via heterotrimeric G. proteins from endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:6689–6696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.617951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feinstein TN, et al. Retromer terminates the generation of cAMP by internalized PTH receptors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:278–284. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoffmann R, Baillie GS, MacKenzie SJ, Yarwood SJ, Houslay MD. The MAP kinase ERK2 inhibits the cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase HSPDE4D3 by phosphorylating it at Ser579. EMBO J. 1999;18:893–903. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wehbi VL, et al. Noncanonical GPCR signaling arising from a PTH receptor-arrestin-Gβγ complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1530–1535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205756110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Anderson RG, Russell DW, Schneider WJ. Receptor-mediated endocytosis: concepts emerging from the LDL receptor system. Ann. Rev. Cell Biol. 1985;1:1–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vilardaga JP, Jean-Alphonse FG, Gardella TJ. Endosomal generation of cAMP in GPCR signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:700–706. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Juppner H, Schipani E, Silve C. In: Principles of Bone Biology. 3rd Edn. Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, Martin TJ, editors. Vol. 2. Elsevier; 2008. pp. 1431–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen XS, et al. Initial characterization of PTH-related protein gene-driven LacZ expression in the mouse. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:113–123. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee K, Deeds JD, Segre GV. Expression of parathyroid hormone-related peptide and its receptor messenger ribonucleic acids during fetal development of rats. Endocrinology. 1995;136:453–463. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.2.7835276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Juppner H, et al. A G-protein linked receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Science. 1991;254:1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1658941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jobert AS, et al. Absence of functional receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide in Blomstrand chondrodysplasia. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:34–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Couvineau A, et al. PTHR1 mutations associated with Ollier disease result in receptor loss of function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:2766–2775. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]