Abstract

Study question Can avian influenza A (H7N9) virus be transmitted between unrelated individuals in a hospital setting?

Methods An epidemiological investigation looked at two patients who shared a hospital ward in February 2015, in Quzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Samples from the patients, close contacts, and local environments were examined by real time reverse transcriptase (rRT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and viral culture. Haemagglutination inhibition and microneutralisation assays were used to detect specific antibodies to the viruses. Primary outcomes were clinical data, infection source tracing, phylogenetic tree analysis, and serological results.

Study answer and limitations A 49 year old man (index patient) became ill seven days after visiting a live poultry market. A 57 year old man (second patient), with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, developed influenza-like symptoms after sharing the same hospital ward as the index patient for five days. The second patient had not visited any poultry markets nor had any contact with poultry or birds within 15 days before the onset of illness. H7N9 virus was identified in the two patients, who both later died. Genome sequences of the virus isolated from both patients were nearly identical, and genetically similar to the virus isolated from the live poultry market. No specific antibodies were detected among 38 close contacts. Transmission between the patients remains unclear, owing to the lack of samples collected from their shared hospital ward. Although several environmental swabs were positive for H7N9 by rRT-PCR, no virus was cultured. Owing to delayed diagnosis and frequent hospital transfers, no serum samples were collected from the patients, and antibodies to H7N9 viruses could not be tested.

What this study adds Nosocomial H7N9 transmission might be possible between two unrelated individuals. Surveillance on patients with influenza-like illness in hospitals as well as chickens in live poultry markets should be enhanced to monitor transmissibility and pathogenicity of the virus.

Funding, competing interests, data sharing Funding support from the Program of International Science and Technology Cooperation of China (2013DFA30800), Basic Work on Special Program for Science and Technology Research (2013FY114600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81402730), Special Program for Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in China (2013ZX10004218), US National Institutes of Health (1R01-AI108993), Zhejiang Province Major Science and Technology Program (2014C03039), and Quzhou Science and Technology Program (20111084). The authors declare no other interests and have no additional data.

Introduction

Since the emergence of human infections with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in February 2013, China has experienced three epidemic waves. The epidemic has affected extensive areas in 17 provinces and municipalities of mainland China. Several imported cases of the virus have been identified in Taiwan, Malaysia, Canada, and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China. As of 21 June 2015, 672 laboratory confirmed human cases with 271 deaths (fatality rate 40%) were reported.1

Experimental models using ferrets, mice, and pigs showed that the H7N9 virus isolates from people could replicate in mammalian and human airway cells, and be transmitted efficiently through direct contact. However, transmissibility by droplets was moderate,2 3 4 implying that the virus possesses the potential for person to person transmission. Reported person to person transmissions have all occurred in family clusters, suggesting that either common exposures or host genetic susceptibility might contribute to H7N9 infection.5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Here, we report a possible person to person transmission between two unrelated individuals in a hospital, and provide epidemiological and virological evidence supportive of nosocomial infection.

Methods

Description of the two patients

The index patient was a 49 year old man who worked in a local mine as a pneumatic drill operator. He developed a fever (37.5°C), cough, and sore throat on 16 February 2015, and sought medical care at a village clinic, and received oral cefalexin and fupoganmao capsules (Chinese medicine). The next day, he visited another clinic and was administered amoxicillin and vitamin C intravenously. Because of a constant fever (37.8°C) and severe cough, the patient was admitted to the district hospital (hospital A) on 18 February and treated with amoxicillin and levofloxacin. On the following day, the patient developed high fever (40°C) with a cough and given oxygen nasal cannula. A computed tomography scan on 22 February revealed bilateral lobe infiltrates (web fig S1).

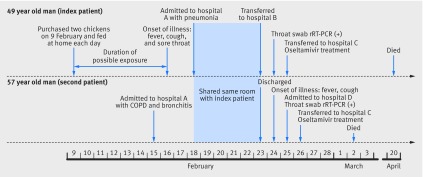

On the request of the index patient’s dependents, he was transferred to a provincial hospital (hospital B) on 23 February. He was identified with having the H7N9 virus by use of real time reverse transcriptase (rRT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on a swab specimen taken from his throat on 24 February. After confirmation of the diagnosis, the patient was transferred to specialist hospital (hospital C) on 25 February, and treated with oseltamivir. He was admitted to an isolation ward with intensive care facilities because of H7N9 infection, and died of multiorgan failure on 20 April. The figure summarises the timeline of events.

Timeline of events in 2015 associated with two human H7N9 infections in Quzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. rRT-PCR=real time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The second patient was a 57 year old man with a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for over 30 years. He was admitted to hospital A with a diagnosis of aggravated COPD on 15 February 2015, and was treated with methylprednisolone, spironolactone, furosemide, and sodium bicarbonate, and given oxygen by nasal cannula. On 18 February, the index patient was sent to the same ward, and stayed for five days. The second patient was discharged from hospital A on 23 February after his symptoms improved and main biochemical test results became normal. The next day, the second patient developed a fever (40°C) and cough. Because he was recognised as a close contact of the index patient and had become sick at that time, the second patient was promptly transported to a negative pressure ward of hospital D for isolation, diagnosis, and treatment on 25 February. His throat swab sample was collected on the same day, and was positive for the H7N9 virus when tested by rRT-PCR. After diagnosis of H7N9 infection was confirmed, the second patient was transferred to hospital C on 26 February and treated with oseltamivir. The second patient died of respiratory failure on 2 March (fig). Table 1 summarises the clinical characteristics of the two patients.

Table 1 .

Clinical characteristics of two patients with confirmed influenza A (H7N9) virus on hospital admission

| Characteristic | Index patient | Second patient |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49 | 57 |

| Sex | Male | Male |

| Occupation | Pneumatic drill operator | Farmer |

| Type of exposure | Visited live poultry market and bought two chickens | Shared same room with index patient |

| Underlying medical disorders | No | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Time spent smoking (years) | 30 | 0 |

| Relationship between two patients | Shared the same hospital ward | Shared the same hospital ward |

| Onset of illness | 16 February 2015 | 24 February 2015 |

| Date of hospital admission | 18 February 2015 (hospital A) | 25 February 2015 (hospital D) |

| Signs of illness | Fever, cough, and sore throat | Fever and cough |

| Temperature (°C) | 38.8 | 38.4 |

| White blood count (×109/L) | 6.4 | 17.8* |

| Neutrophils (×109/L) | 1.68 | 1.74 |

| Lymphocytes (×109/L) | 0.35 | 0.26 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 146 | 98 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 29.5 | 233* |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | n/a | 36.2 |

| PaO2 (mm Hg) | n/a | 62 |

| Saturation of peripheral oxygen (%) | 95 | 90.5 |

| Chest radiography | Pneumonia | n/a |

| Mechanical ventilation | Yes | Yes |

| Oseltamivir treatment | Yes | Yes |

| Oxygen treatment | Yes | Yes |

| Outcome | Died | Died |

n/a=not applicable.

*The second patient’s elevated white blood cell count, neutrophil cells, and C reactive protein suggests a bacterial infection, which could have been due to a mixed infection of the H7N9 virus and a bacterium.

Epidemiological investigations

Because the index patient was seriously ill at the time of investigation, public health staff from the local centres for disease control and prevention interviewed the second patient as well as both patients’ family members and healthcare workers. The epidemiological investigations focused on exposure history before the onset of illnesses, such as keeping birds or contact with birds, purchasing live poultry, visiting live poultry markets, and contact history with febrile people, to identify the possible infective source. We also reviewed all medical records from the hospitals where the two patients visited to verify the timelines of events and clarify their clinical courses.

To trace the possible infection sources of the index patient, we collected two faecal samples and two swabs from the cage, which had been used to keep the two chickens purchased from a live poultry market. We then went to the live poultry market where the two chickens were bought, and collected 11 environmental samples, including three swabs from chicken cages, two swabs from the molting machine, four chicken faeces samples, and two sewage samples.

To clarify the infection sources of the second patient, we first investigated the possible exposure at his dwelling place. Because he neither had a poultry farm nor kept any live poultry at home, we collected six swab samples from the surface of chicken eggs in the refrigerator, from the table surface, and from trash containers. In addition, we collected seven faecal samples from chicken faeces raised in courtyard of his neighbour and two pooled samples (one with five faecal samples, and the other with three water samples) from the only chicken farm about 1 km away from the second patient’s village. We were not able to collect any samples from the ward where the two patients simultaneously stayed, because the hospital had undergone terminal disinfection immediately after the index patient’s diagnosis of H7N9 virus infection was confirmed.

Medical observation of close contacts

Close contacts included all family members who lived with the two patients, healthcare workers and other people who had contact with the two patients within 1 metre without proper personal protection during the period from the symptom onset to isolation in specialist hospitals (web appendix). Close contacts were monitored for fever (≥38°C) and influenza-like symptoms for seven days. If any close contact developed an influenza-like illness, throat swabs were collected to detect H7N9 virus. Paired serum samples (separated by four weeks) from close contacts of the two patients were collected to detect specific antibodies against H7N9 for evaluating subclinical H7N9 infections.

Detection and identification of H7N9 virus

All the samples collected from people and environments were stored at −20 °C and transported to biosafety level (BSL) 2 and 3 laboratories for testing and isolating the H7N9 virus. An rRT-PCR assay targeting the influenza matrix gene was performed.14 For virus isolation, specimens positive for the virus were inoculated into allantoic cavities of 9 to 11 day old embryonated chicken eggs that were specific pathogen free (SPF), as previously described.15 Full length genome sequences were obtained by Ion Torrent PGM technology (Life Technologies) 16 and deposited in the GenBank (accession no KR351265-KR351272 for the index patient, KR351273-KR351280 for the second patient, and KR351260-KR351264 for one environmental sample). We used the maximum likelihood method to generate phylogenetic trees using MEGA version 6.0.6 (www.megasoftware.net/).

Receptor binding specificity of A/Quzhou/1/2015(H7N9) was analysed by a solid phase direct binding assay as previously described.17 We used the A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) and A/Chicken/Jiangsu/927/2014 (H5N1) viruses as controls (web appendix).

Serological assays

Serum samples from close contacts were tested with a haemagglutination inhibition assay with horse erythrocytes.18 If titres for this assay were at least 1:20, we used a microneutralisation assay19 to confirm results. The virus A/Quzhou/1/2015(H7N9) isolated from the index patient was used in both assays (web appendix).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or outcomes, designing the investigation or interpreting the data. Patient participants were not informed of the results of the study.

Results

The index patient lived with his wife, son, and two daughters in a courtyard of a village. They had not raised any poultry and other animals before. However, on 9 February, seven days before onset of his illness, he purchased two live chickens from a live poultry market (web fig S2) for the wedding ceremony of his elder daughter. According to local custom, fathers usually give two chickens to the bride to show best wishes, because the Chinese pronunciation of chicken is the same as that of “good luck.” Two chickens mean double luck. The two live chickens were kept and fed by the patient until he was ill. The patient had no other market exposure and no known contact with any person with a respiratory infection or fever during the 15 days before his illness. Two faecal samples from the chickens kept at his home as well as five (one from the chicken cage, one from the molting machine, two chicken faeces samples, and one sewage sample) of 11 samples from the live poultry market which he visited were positive for H7N9 virus.

The second patient lived with his wife in a village located at different county from that of the index patient. He had neither visited any live poultry market nor contacted with any poultry or birds within the 15 days prior to onset of his disease due to infection H7N9 virus. We investigated possible exposures at his residential place, and found neither live poultry nor other animals at his home. Tens of chickens were found in a household in the same village approximately 200 metres away from the patient’s home. There was a chicken farm about 1 km away from the village. However, he had never visited his neighbours or the chicken farm, because he usually stayed at home owing to having COPD. Furthermore, six swab samples from his home, seven faecal samples from chickens raised by his neighbours, and two pooled samples from the chicken farm were all negative for H7N9 virus.

On 15 February, the second patient was admitted to hospital A for treatment of his aggravated COPD. On admission, he had normal body temperature and normal results of routine blood tests according to his medical records. In the afternoon of 18 February, the index patient was admitted to the same ward as the second patient. The ward was about 25 m2 in size with three beds and a bathroom. A third patient, who had diabetes, also shared the ward. The index patient’s bed was close to the window. Next to it was the second patient’s bed. The bed of the patient with diabetes was next to the second patient’s bed, near the bathroom (web fig S3). The distance between beds was about 80 cm.

A spittoon was intermittently placed between the beds of the index and second patients between 18 and 23 February, because the index patient had a frequent cough and heavy expectoration. The index patient would normally spit directly into the spittoon or into a tissue paper. Both the index and second patients received supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula. The nurses used the same sphygmomanometer to measure their blood pressures. The patients did not share any other medical equipment. During his stay at hospital A, the second patient did not undertake any outdoor activities but occasionally walked about the room, and only ate the meals provided by the nutrition department of the hospital.

One virus strain was isolated from a throat swab of the index patient, and its full length genome was sequenced. The full length H7N9 virus genome was also obtained directly from a throat swab of the second patient. Sequences of segments from the second patient (polymerase basic (PB) 1, PB2, nucleoprotein, matrix, and non-structural protein) were identical to those of the strain isolated from the index patient. There was one base pair (bp) difference in the nucleotide sequence of the polymerase (PA) segment between the two viruses, without amino acid change. Compared with the index patient, the second patient had 1 bp and 2 bp differences in the nucleotide sequence of the haemagglutinin and neuraminidase segments, respectively, leading to an amino acid change (table 2). Sequences of five segments (except for the PB1, PB2, and PA segments) were yielded from a chicken faecal sample from the live poultry market. Compared with the avian origin strain from the live poultry market, the two patients’ sequences were slightly different (table 2).

Table 2 .

Differences between three strains of influenza A (H7N9) viruses from two patients and one environment sample in Quzhou, China, 2015

| Viral segment and virus strain | Proportion (%) of identical sequence (nucleotide/amino acid) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | A/Quzhou/2/2015 | A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | |

| Polymerase basic 2 | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 100/100 | n/a |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0/0 | —/— | n/a |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | n/a | n/a | —/— |

| Polymerase basic 1 | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 100/100 | n/a |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0/0 | —/— | n/a |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | n/a | n/a | —/— |

| Polymerase | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 99.95/100 | n/a |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0.05/0 | —/— | n/a |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | n/a | n/a | —/— |

| Nucleoprotein | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 100/100 | 99.98/100 |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0/0 | —/— | 99.98/100 |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | 0.02/0 | 0.02/0 | —/— |

| Haemagglutinin | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 99.94/99.82 | 99.88/99.82 |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0.06/0.18 | —/— | 99.82/99.64 |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | 0.12/0.18 | 0.18/0.36 | —/— |

| Neuraminidase | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 99.86/99.78 | 99.71/99.78 |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0.14/0.22 | —/— | 99.86/100 |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | 0.29/0.22 | 0.14/0 | —/— |

| Matrix | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 100/100 | 99.69/100 |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0/0 | —/— | 99.69/100 |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | 0.31/0 | 0.31/0 | —/— |

| Non-structural protein | |||

| A/Quzhou/1/2015 | —/— | 100/100 | 100/100 |

| A/Quzhou/2/2015 | 0/0 | —/— | 100/100 |

| A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015 | 0/0 | 0 | —/— |

A/Quzhou/1/2015=strain isolated from index patient; A/Quzhou/2/2015=strain from second patient; A/Chicken/Quzhou/1/2015=strain from environmental sample from the live poultry market; n/a=not applicable owing to the lack of sequencing data.

Phylogenetic analyses revealed that the viruses from patients and environment were clustered in the same clade, and were genetically similar to those from chickens in 2014 but different from those identified in China in 2013 (web fig S4). The three H7N9 viruses were examined for key mutations associated with virulence and mammalian adaption. No significant mutation site was identified in the three H7N9 viruses compared with previous strains in China (web table S1). Receptor binding specificity assays revealed that A/Quzhou/1/2015/H7N9 could bind to both human and avian receptors (web fig S5).

We identified a total of 38 close contacts of the two patients, including six family members, 18 healthcare workers, and four other people for the index patient; and five family members, one healthcare worker, and four other people for the second patient. A male doctor who was in charge of the index patient developed a light cough on 23 February and a fever (37.7°C) on 25 February, which persisted to 27 February. However, three throat swabs collected from the index patient’s doctor on 26 February were all found to be negative for H7N9 virus. He began to take oseltamivir on 27 February for seven days. The patient with diabetes who shared the same wards as the index and second patients did not develop any influenza-like signs or symptoms. No seroconversion of antibodies against H7N9 virus was identified by either the haemagglutination inhibition or microneutralisation assays from paired serum samples of all close contacts, which were collected separately on 26 February and 28 March.

Discussion

Although we cannot completely rule out an unidentified environmental exposure that might explain the H7N9 infection in the second patient, our findings suggest that H7N9 virus transmission occurred in the hospital setting between two unrelated people, the index patient and the second patient. Firstly, the second patient developed symptoms after five days’ contact with the index patient at hospital A. Secondly, the second patient had no history of poultry exposure, contact with other patients with respiratory illness, and had not visited a live poultry market or a poultry farm for 15 days before his illness. Thirdly, chicken and environmental samples collected from the second patient’s home, his neighbour’s home, and the only chicken farm in his village were all negative for H7N9 virus. Fourthly, the second patient had no fever before and immediately after his admission to hospital A. Lastly, the genome sequence of H7N9 virus from the second patient was nearly identical to that from the index patient. Hence, it seems most likely that the H7N9 virus was transmitted from the index patient to the second patient during their stay in the same ward. This transmission is novel, because previous reports of family clusters of H7N9 virus infection imply that either host genetic susceptibility to the virus or common exposures might contribute to the infection.

The three H7N9 viruses (from the index patient, second patient, and environmental sample from the live poultry market) shared similar sequence characteristics with each other and with available human strains. The viruses had the ability to bind to both human and avian receptors. Sequence data suggested that the viruses from the live poultry market had gained the ability to be transmitted from chickens to humans. This might be consistent with the increased number of people infected with H7N9 in the recent H7N9 epidemic wave. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that genome sequences of the three strains were most closely related to H7N9 viruses in 2014.

Our findings strongly suggest that the live poultry market is the most probable source of influenza H7N9 virus infection for the index patient, because no other animals were kept at his home and he had no exposure to poultry before he bought the two chickens from the market. Additionally, faecal samples from either the chickens he purchased or the live poultry market were positive for H7N9. This implication of live bird markets as an amplifying source of H7N9 is consistent with previous reports.20 21 22 23 24 25 In fact, shutting down live poultry markets has been strongly correlated with subsequent fall in human H7N9 infections.26 27

Important strengths and differences in relation to other studies

Compared with previously reported clusters of H7N9 infections among family members, we document a probable H7N9 transmission between two unrelated people in hospital setting. It is uncertain whether the second patient was infected by droplets or by direct contact with the index patient’s secretion. The index patient had a frequent cough and expectoration during his hospital stay. An experimental study indicates that a H7N9 virus isolated from humans is highly transmissible in ferrets via droplets.3 However, the third patient with diabetes, who had shared the same ward with the two patients with H7N9, was not infected with the virus. It seems probable that proximity to the index patient and his COPD contributed to the infection of the second patient.

Implications of the study

Although the person to person transmission occurred in a patient with COPD, the nosocomial infection of H7N9 should raise our concern about the increasing threat to public health. It is now the time to take infection control measures to reduce the risk of H7N9 virus transmission in hospital settings. Local hospitals should recognise the influenza A (H7N9) endemic, train their doctors to understand the disease and properly use personal protective equipment, and timely conduct laboratory tests for diagnosis in suspected patients. In addition, hospital hygiene should be strengthened to reduce the risk of nosocomial infections.

Weaknesses of the study

This study had several limitations. Firstly, although a likely nosocomial transmission between two unrelated persons was identified, how the transmission occurred remains unclear, owing to the lack of environmental samples collected from the shared ward where they stayed. Secondly, while several environmental swabs were positive for H7N9 by rRT-PCR, no virus was cultured. Thirdly, owing to delayed diagnosis and frequent hospital transfer of the patients, we did not receive serum samples from the two patients and could not test their antibodies to H7N9 viruses.

Unanswered questions and future research

With the continuing genetic evolution and extensive geographical spread of H7N9 virus in mainland China, the identification of person to person transmission between unrelated individuals implies greater challenges for the prevention and control of the emerging infectious disease. Thus, aetiological surveillance on patients with influenza-like illness in hospitals as well as chickens in live poultry markets should be enhanced to monitor transmissibility and pathogenicity of the novel virus.

What is already known on this topic

Since the emergence of human infections with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in February 2013, China has experienced three epidemic waves

Reported person to person transmissions have all occurred in family clusters, suggesting that either common exposures or host genetic susceptibility might contribute to H7N9 infection

What this study adds

Our investigation provides evidence of person to person transmission between unrelated individuals in a hospital setting

Surveillance on patients with influenza-like illness in hospitals as well as chickens in live poultry markets should be enhanced to monitor transmissibility and pathogenicity of the novel virus

We thank all the healthcare workers who helped us in this work, and all the participants for their cooperation.

Contributors: M-JM, GCG, L-QF, and W-CC designed the study. C-FF, M-JM, B-DZ, L-QF, GCG, E-FC, and W-CC drafted the manuscript. C-FF, B-DZ, S-ML, G-PC, J-MZ, S-QW, X-LH, E-FC, Y-JL, X-XW, WC, J-FJ, H-MY, and W-DX conducted the epidemiological investigation and collected samples. M-JM, YH, X-XY, JL, J-JZ, H-WY, and X-LL performed laboratory assays. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and approved the final draft. C-FF, M-JM, and B-DZ contributed equally to this study. L-QF, E-FC, and W-CC have equal contribution. L-QF and W-CC are guarantors.

Funding: This study was supported by the Program of International Science and Technology Cooperation of China (2013DFA30800), Basic Work on Special Program for Science and Technology Research (2013FY114600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81402730), Special Program for Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in China (2013ZX10004218), US National Institutes of Health (1R01-AI108993), Zhejiang Province Major Science and Technology Program (2014C03039), and Quzhou Science and Technology Program (20111084). The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the Program of International Science and Technology Cooperation of China, Basic Work on Special Program for Science and Technology Research, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Special Program for Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in China, US National Institutes of Health, Zhejiang Province Major Science and Technology Program, and Quzhou Science and Technology Program for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: An ethics waiver was granted and authorised under the National Emergent Public Health Events Act. According to this Act, collection of data related to H7N9 cases was an important part in epidemic analyses and subsequent control measures. Therefore, the investigation was exempt from institutional board assessment.

Patient consent: The family members of the two patients signed consent forms approving the investigation and its publication.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

C-FF, E-FC, L-QF, and W-CC affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;351:h5765

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix: Supplementary materials

References

- 1.FluTrackers. FluTrackers 2013-15 human case list of provincial/Ministry of Health/government confirmed Influenza A(H7N9) cases, 2015. https://flutrackers.com/forum/forum/china-h7n9-outbreak-tracking/143874-flutrackers-2013-15-human-case-list-of-provincial-ministry-of-health-government-confirmed-influenza-a-h7n9-cases-with-links.

- 2.Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature 2013;501:556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Shi J, Deng G, et al. H7N9 influenza viruses are transmissible in ferrets by respiratory droplet. Science 2013;341:410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu H, Wang D, Kelvin DJ, et al. Infectivity, transmission, and pathology of human-isolated H7N9 influenza virus in ferrets and pigs. Science 2013;341:183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q, Zhou L, Zhou M, et al. Epidemiology of human infections with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China. N Engl J Med 2014;370:520-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu T, Bi Z, Wang X, et al. One family cluster of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infection in Shandong, China. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi L, Guan D, Kang M, et al. Family clusters of avian influenza A H7N9 virus infection in Guangdong Province, China. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:22-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao HN, Yao HP, Liang WF, et al. Viral genome and antiviral drug sensitivity analysis of two patients from a family cluster caused by the influenza A(H7N9) virus in Zhejiang, China, 2013. Int J Infect Dis 2014;29:254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao H, Guo B, Wang F, et al. A study of family clustering in two young girls with novel avian influenza A (H7N9) in Dongyang, Zhejiang Province, in 2014. J Clin Virol 2015;63:18-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi X, Qian YH, Bao CJ, et al. Probable person to person transmission of novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in Eastern China, 2013: epidemiological investigation. BMJ 2013;347:f4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao XC, Li KB, Chen ZQ, et al. Transmission of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus from father to child: a report of limited person-to-person transmission, Guangzhou, China, January 2014. Euro Surveill 2014;19:20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu J, Zhu Y, Zhao B, et al. Limited human-to-human transmission of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, Shanghai, China, March to April 2013. Euro Surveill 2014;19:20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding H, Chen Y, Yu Z, et al. A family cluster of three confirmed cases infected with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in Zhejiang Province of China. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Real-time RT-PCR protocol for the detection of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, 2014. www.who.int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/cnic_realtime_rt_pcr_protocol_a_h7n9.pdf.

- 15.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1888-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu W, Fan H, Raghwani J, et al. Occurrence and reassortment of avian influenza A (H7N9) viruses derived from coinfected birds in China. J Virol 2014;88:13344-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma MJ, Yang XX, Qian YH, et al. Characterization of a novel reassortant influenza A virus (H2N2) from a domestic duck in Eastern China. Sci Rep 2014;4:7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Serological detection of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infections by modified horse red blood cells haemagglutination-inhibition assay, 2013. www.who.int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/cnic_serological_diagnosis_hai_a_h7n9_20131220.pdf.

- 19.Rowe T, Abernathy RA, Hu-Primmer J, et al. Detection of antibody to avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in human serum by using a combination of serologic assays. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:937-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster RG. Wet markets—a continuing source of severe acute respiratory syndrome and influenza? Lancet 2004;363:234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, Feng Z, Zhang X, et al. Human influenza A (H5N1) cases, urban areas of People’s Republic of China, 2005-2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mounts AW, Kwong H, Izurieta HS, et al. Case-control study of risk factors for avian influenza A (H5N1) disease, Hong Kong, 1997. J Infect Dis 1999;180:505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Cowling BJ, Wu P, et al. Human exposure to live poultry and psychological and behavioral responses to influenza A(H7N9), China. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:1296-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B, Havers F, Chen E, et al. Risk factors for influenza A(H7N9) disease—China, 2013. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:787-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao CJ, Cui LB, Zhou MH, Hong L, Gao GF, Wang H. Live-animal markets and influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu P, Jiang H, Wu JT, et al. Poultry market closures and human infection with influenza A(H7N9) virus, China, 2013-14. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:1891-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Y, Liu P, Tang S, et al. Live poultry market closure and control of avian influenza A(H7N9), Shanghai, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:1565-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary materials