Abstract

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) has been consistently associated with increased risk for cardiovascular diseases, including arrhythmias. The purpose of this review is to elucidate the several pathophysiologic pathways such as repetitive hypoxia and reoxygenation, increased oxidative stress, inflammation and sympathetic activation that may underlie the increased incidence of arrhythmias in SDB patients. We discuss in particular the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation and bradyarrhythmias in SDB patients. In addition, we discuss the electrocardiographic alteration such as ST-T changes during apneic events and QT dispersion induced by SDB that may trigger complex ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Finally, we consider also the therapeutic interventions such as continuous positive airways pressure therapy, a standard treatment for SDB, that may reduce the incidence and recurrence of supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias in patients with SDB.

Keywords: arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, bradyarrhythmias, sleep-disordered breathing

Introduction

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and central sleep apnea (CSA), has been consistently associated with increased risk for cardiovascular diseases and developing arrhythmias.1–3

Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by repetitive collapse of the upper airway, whereas the hallmark of CSA is recurrent complete or partial withdrawal of central respiratory drive.

In this review, we will focus on the mechanisms that mediate ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias in OSA and CSA, with emphasis on atrial fibrillation and available therapeutic strategies.

Sleep-disordered breathing and ventricular arrhythmias

Sleep-disordered breathing, including both OSA and CSA, is associated with increased incidence of isolated ventricular arrhythmias and nonsustained and sustained ventricular tachycardia.

Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and complex ventricular ectopy (bigeminy, trigeminy, or quadrigeminy) were more common among 228 patients aged 65 years or less with severe OSA [apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 30] compared with controls after adjustment for age, sex, obesity, and underlying cardiovascular disease.2

Whereas the prevalence of complex ventricular ectopy peaks in middle age and declines with advancing age, its presence correlates with the severity of OSA and the degree of intermittent hypoxia among elderly patients.2,3 Furthermore, in elderly patients with moderate SDB and normal left-ventricular function, the presence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and isolated ventricular arrhythmias is similar to controls free of SDB, suggesting that untreated severe SDB may be a significant contributor to ventricular arrhythmias observed in elderly patients.4

The recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia or premature ventricular complexes, after a successful catheter ablation, was greater in patients with untreated SDB than those without SDB (45 vs. 6%).5

In patients with decreased left-ventricular ejection fraction (≤40%), ventricular premature beats and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia are more common in patients with severe CSA than in those with mild or no CSA, suggesting that CSA may augment arrhymogenic potential of systolic dysfunction.6

In patients with acutely decompensated heart failure and CSA, the severity of CSA and increased levels of C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation, are associated with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia during daytime [1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00–6.92; and 5.82, 95% CI 2.58–56.1, respectively] and night-time (3.57, 95% CI 1.06–13.1; and 10.7, 95% CI 3.30–44.4, respectively). Although, patients with heart failure and concomitant CSA have greater mortality than patients with heart failure who are free of CSA, only 2.8% of heart failure/CSA patients had fatal ventricular tachyarrhythmias.7

Furthermore, ventricular ectopy and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia are not good predictors of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with heart failure.8 In contrast, both CSA and OSA are independent risk factors for life-threatening arrhythmias.9

In summary, the presence of ventricular ectopy and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia correlates directly with the severity of both OSA and CSA, supporting their association, which has been repeatedly observed in cross-sectional studies.

Sustained ventricular tachycardia and life-threatening arrhythmias are also associated with the presence of OSA and CSA.

In a case–control study involving 200 participants, greater QT dispersion, a well established contributor to ventricular arrhythmias, was observed in OSA patients compared with patients without OSA, suggesting a possible mechanistic link between OSA and ventricular arrhythmias.10 In addition to well established chronically elevated sympathetic activity, spontaneous prolongation of ST segment during sleep, which correlates with the risk of ventricular arrhythmias, may contribute to increased risk of SCD between midnight and 0600 h in patients with SDB.11

In a retrospective study conducted on 112 Minnesotans who underwent sleep study, SCD occurred between midnight and 0600 h in nearly half of the patients with OSA.12 In contrast, the peak hours of SCD were 0600 h until noon in the general population.13 Moreover, SCD occurred at a greater rate in OSA than in non-OSA patients (46 vs. 21%).13

Severity of OSA correlated directly with the relative risk of SCD occurring from midnight to 0600 h OSA patients with severe AHI (AHI ≥ 40) had a 40% increase likelihood of experiencing SCD between midnight and 0600 h compared to those with less severe OSA.12 These observations strongly support OSA as a condition that increases risk for SCD.

In heart failure patients with low left-ventricular ejection fraction and implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), severity of both CSA and OSA correlates with the risk for complex ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate defibrillation. A CSA AHI of at least 15 events/h doubles the risk for developing malignant ventricular arrhythmias and triples the risk for appropriate defibrillation. Similarly, patients with moderate to severe OSA (AHI ≥ 15 events/h) also have increased risk for complex ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate defibrillation, thereby strengthening the association between complex ventricular arrhythmias and SDB.14

Treatment of SDB may decrease the risk for ventricular arrhythmias in these patients. Treatment with continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) reduces ventricular ectopy in patients with SDB. In patients with concomitant heart failure and OSA, who had at least 10 ventricular premature beats/h despite receiving beta blockers, CPAP therapy reduced occurrence of arrhythmias during sleep compared with pretreatment baseline, thereby suggesting that treatment of SDB may reduce arrhythmia burden in these patients.15

Definitive evidence of a protective effect of CPAP against the occurrence of malignant arrhythmias is still lacking in OSA patients. Furthermore, a post-hoc analysis of the Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial trial showed some benefit of CPAP therapy on transplant-free survival in a subset of patients with CSA in whom CSA was suppressed with CPAP therapy.16 The impact of CPAP on survival in patients with CSA and malignant arrhythmias remains unknown.

Treatment of acute exacerbation of heart failure does not consistently improve CSA, and, presently, no data are available regarding therapeutic strategies to improve survival and reduce arrhythmia burden in patients with heart failure and concomitant CSA.17

Sleep-disordered breathing and atrial fibrillation

Sleep-disordered breathing is associated with atrial fibrillation independently from coexistent cardiovascular diseases.2

In a retrospective study of 3542 patients without past or current atrial fibrillation referred to the Sleep Center for suspected SDB, those with OSA and 65 years or less of age had increased risk for developing atrial fibrillation compared with patients without OSA after adjustment for potential confounders, such as male sex, BMI, and history of coronary artery disease (CAD).18 Moreover, OSA is associated with increased risk for atrial fibrillation independently from obesity.19

In elderly patients, only CSA, but not OSA, was associated with the presence of atrial fibrillation; moreover, prolonged hypoxia during sleep and overall severity of SDB are associated with atrial fibrillation in SDB.3,18,20

The presence of CSA may be associated with unrecognized heart failure in the elderly, which is a well known risk factor for atrial fibrillation.3,18 In addition, several well recognized risk factors for burden of atrial fibrillation such as atrial enlargement, valvular diseases and left-ventricular function have generally not been considered in large cohort studies, which may have biased their conclusions.

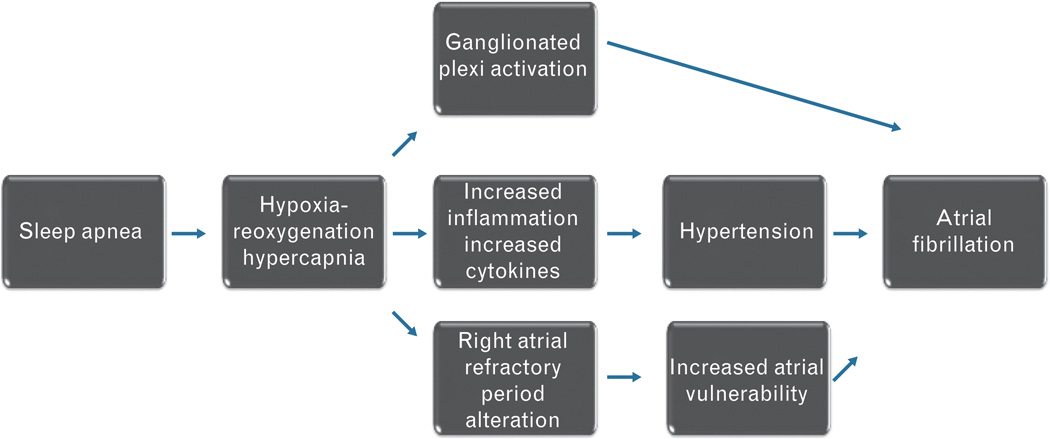

Several pathophysiologic mechanisms may mediate increased risk for atrial fibrillation in SDB (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The pathophysiologic pathways that may mediate increased risk for atrial fibrillation in patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

Repetitive hypoxia and reoxigenation associated with a transient cessation of breathing during apneas and hypopneas in SDB increase sympathetic activation, and systemic oxidative stress and inflammation.21 Increased levels of circulating catecholamines, proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6, and C-reactive protein may trigger atrial fibrillation. In addition, the severity of OSA is associated with the increase in blood pressure, which, in turn, leads to systemic hypertension that can promote atrial fibrillation.22,23

Similarly, the severity of CSA and increased levels of C-reactive proteins are associated with the presence of atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients [odds ratio (OR) 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–2.51].7

In an animal model of OSA, the tracheal negative pressure during an obstructive event induces vagal activation, which shortens right atrial refractory period and triggers atrial fibrillation.24 Furthermore, hypercapnia, rather than hypoxemia, may trigger atrial fibrillation in a sheep model of OSA. The effective refractory period of the right atrium is prolonged in hypercapnia and the conduction time increases after the resumption of eucapnic condition. The risk of triggering atrial fibrillation is low during the hypercapneic event, whereas the recovery phase is associated with the increased risk for atrial fibrillation.25

The autonomic blockade with beta blockers and the ablation of the right pulmonary artery ganglionated plexi during apneas reduce the inducibility of atrial fibrillation in a dog model of atrial fibrillation.25,26

Continuous positive airways pressure therapy reduces the incidence and recurrence of atrial fibrillation in patients with OSA. The risk of recurrence of atrial fibrillation in the year following direct current cardioversion in patients with OSA is reduced by 50% in patients who adhered with CPAP therapy, whereas untreated OSA patients have significantly greater recurrence rate (42 vs. 82%).27

In patients who underwent pulmonary vein isolation with different ablation techniques (radiofrequency and cryoablation), the risk of early recurrence of atrial fibrillation was greater in patients with moderate to severe SDB compared with non-SDB patients. The risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation in OSA patients was two-fold greater than OSA-free atrial fibrillation patients.28–30

Among 640 patients who underwent atrial fibrillation ablation, the long-term therapy with CPAP significantly reduced atrial fibrillation recurrence compared with untreated OSA patients (recurrence rate 68 vs. 79%). Moreover, a non-pulmonary vein trigger of atrial fibrillation was more prevalent in OSA patients, whereas a pulmonary vein trigger was more common in non-OSA patients, which may contribute in part to the failure to prevent atrial fibrillation recurrence.31

Whether obesity is an independent risk factor for atrial fibrillation relapse in patients with OSA remains unclear.

In a prospective study of 109 patients who underwent atrial fibrillation ablation, OSA patients, who were obese, had a two-fold increased risk of arrhythmic recurrence during 3-month follow-up.32 In contrast, other investigators reported that BMI does not affect atrial fibrillation relapse in patients with OSA.33 In a recent meta-analysis, OSA was a strong predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after atrial fibrillation ablation (risk ratio 1.40, 95% CI 1.16–1.68, P = 0.0004).34

Although the correlation between CSA and atrial fibrillation has been repeatedly observed, the optimal treatment of atrial fibrillation in patients with CSA has not been extensively investigated most likely due to common coexistence of CSA and heart failure. The presence of heart failure per se reduces the success of external cardioversion and ablation, which may be an important confounder in a study design.

Despite strong evidence that SDB is an important treatable risk factor for atrial fibrillation, stroke, and death, SDB is not included in conventional multiparametric risk scores such as Congestive heart failure Hypertension Age Diabetes mellitus Stroke2 and Euro Heart Survey.35,36 Atrial fibrillation patients with coexistent SDB, especially those with a moderate to severe AHI, should be considered at high risk of ischemic events and should be strongly encouraged to use CPAP and follow a specific anticoagulation regimen if indicated.35–37

Sleep-disordered breathing and bradyarrhythmias

Sleep-disordered breathing is associated with greater incidence of bradycardia in a small-sample study, and the severity of SDB correlates with duration and severity of bradycardia, whereas large-cohort studies generally do not report such association.2,3

A decrease in heart rate up to 16 b.p.m. is observed in patients with severe OSA, CSA and mixed apneas, and the occurrence of bradycardic episodes is associated with prolonged apneas and more pronounced oxyhemoglobin desaturation.38

Whether patients with SDB and sinus arrest of more than 3 s during night-time may benefit from an implantable pacemaker (PM) to avoid extreme arrhythmias and possible cardiac arrest is unkown.39 PM implantation in patients with sinus arrest are indicated in patients who have diurnal symptoms, whereas nocturnal symptoms do not warrant PM implantation according to the current guidelines.39,40

The majority of patients requiring cardiac pacing have undiagnosed sleep apnea.41 Right atrial overdrive during sleep has been suggested to reduce apneic events by decreasing the autonomic imbalance.42

Such an approach has, however, not proven to be effective in treating SDB. In a recent meta-analysis, including 11 studies in which the use of atrial overdrive was tested in patients with OSA, such therapy lead to a reduction in AHI of approximately 5 events/h, which is inferior to the standard therapy with CPAP, which normalizes AHI after appropriate titration.43

Pathophysiological pathways in sleep-disordered breathing and burden of arrhythmias

Different pathophysiological pathways of autonomic activation in OSA and CSA may contribute to the burden of arrhythmias. OSA and CSA, despite their different cause, share an increased sympathetic activity.

Cessation of respiration during OSA is associated with increased negative intrathoracic pressure due to the obstructive respiratory effort and stimulation of the chest wall mechanoceptors that, with repeated arousals and increased oxidative stress due to intermittent hypoxia, contribute to increased sympathetic nerve activation.44 In CSA, the increased respiratory effort is absent, and only the presence of peripheral mechanisms such as intermittent hypoxia, increased catecholamines, and frequent arousals is responsible for the increased sympathetic activation.45,46

The autonomic nervous system is a known key modulator of heart rate and rhythm during wakefulness and sleep. During non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, heart rate is reduced due to increased parasympathetic activation and decreased sympathetic tone. During rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, sympathetic activation can be elevated, decreased or unchanged compared to NREM sleep.47 Parasympathetic activity during sleep is considered protective from burden of arrhythmias in SDB patients, whereas sympathetic activation is often considered as one of the causes of the burden of arrhythmias in SDB patients.48,49

Somers et al.50 reported progressively increased sympathetic peroneal nerve activation during apneic phase in patients with OSA, followed by decrease in muscle sympathetic activity during resumption of breathing. But the peroneal nerve activation peaks and remains elevated after few seconds of apnea termination.50

In another study by Trinder et al.,51 the blood pressure peaks at apnea termination. The discrepancy between sympathetic activation peak and blood pressure peak and peroneal nerve activation may be due to a delay of the sympathetic response between the heart and the peroneal nerve, reduction of baroreflex activity, and a delay between the sympathetic activation and blood pressure and heart rate.45,51

Although the mechanisms underlying increased sympathetic activity in SDB have been investigated extensively, the direct causal link between increased sympathetic activation, SDB and arrhythmias remains to be proven definitively. Altered baroreflex sensitivity is highly predictive of arrhythmia burden and SCD, especially in patients with low left-ventricular ejection fraction.49,52

Impaired baroreflex activity may promote malignant ventricular tachycardia and SCD due to increased nocturnal sympathetic activation and parasympathetic withdrawal in CSA and OSA.14,45,50

Sympathetic activation leads to increase circulating catecholamines, activation of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and vasoconstriction, thereby contributing to arrhythmia burden in SDB. Increased chemosensitivity to both hypoxemia and hypercapnia in patients with heart failure and concomitant CSA is associated with arrhythmia burden such as ventricular arrhythmia and atrial fibrillation.53

Bradyarrhythmias, such as sinus pauses and atrioventricular blockade, and brady-tachy syndrome have been observed in SDB, but the pathophysiological mechanisms are still not clear.

Sympathetic and parasympathetic alternation in OSA may underlie the brady-tachy syndrome burden.47,54

Vagal hyperactivity during REM sleep in the absence of the compensatory sympathetic activation may result in bradycardia and sinus pauses of more than 2 s.55,56 Irrespective of the type of SDB, apnea and hypoxemia often result in bradycardia.38 The administration of supplemental oxygen during sleep results in prolongation of apnea and attenuation of cardiac deceleration in SDB.38

The importance of the carotid chemosensitivity in the pathogenesis of bradycardia during SDB is suggested by two studies conducted on healthy individuals with simulated OSA.57,58 Decreased heart rate during simulated OSA correlates with hypoxic response during wakefulness and heart rate variation is due to individual hypoxic chemosensitivy.57,58

In summary, increased sympathetic drive, altered baroreflex activation, vagal hyperactivity, carotid sensitivity, and parasympathetic and sympathetic alternations may underlie the increased burden of bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias in SDB patients.

Conclusions

In summary, strong evidence suggests that SDB increases the risk of arrhythmias. Inflammation, oxidative stress, sympathetic and parasympathetic activation promote atrial fibrillation and tachyarrhythmias, thereby increasing the risk of SCD in OSA patients. CPAP therapy may reduce the recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias in SDB patients and improve prognosis in OSA patients. CPAP therapy does not affect prognosis in congestive heart failure patients with concomitant CSA. New therapeutic strategies to reduce arrhythmia burden in this subgroup of patients are warranted.

References

- 1.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. AmericanHeart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Stroke Council; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American College of Cardiology Foundation. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College Of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council On Cardiovascular Nursing. In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health) Circulation. 2008;118:1080–1111. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, et al. Sleep Heart Health Study. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:910–916. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosy PD, et al. Nocturnal Arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep-disordered breathing in older men: outcomes of sleep disorders in older men (MrOS sleep) study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1147–1155. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padeletti M, Vignini S, Ricciardi G, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and arrhythmia burden in pacemaker recipients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:1462–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koshino Y, Satoh M, Katayose Y, et al. Sleep apnea and ventricular arrhythmias: clinical outcome, electrophysiologic characteristics, and follow-up after catheter ablation. J Cardiol. 2010;55:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanfranchi PA, Somers VK, Braghiroli A, et al. Central sleep apnoea in left ventricular dysfunction: prevalence and implications for arrhythmic risk. Circulation. 2003;107:727–732. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000049641.11675.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano K, Watanabe E, Hayano J, et al. Central sleep apnoea and inflammation are independently associated with arrhythmia in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1003–1010. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teerlink JR, Jalaluddin M, Anderson S, et al. Ambulatory ventricular arrhythmias in patients with heart failure do not specifically predict an increased risk of sudden death. PROMISE (Prospective Randomized Milrinone Survival Evaluation) Investigators. Circulation. 2000;101:40–46. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serizawa N, Yumino D, Kajimoto K, et al. Impact of sleep-disordered breathing on life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia in heart failure patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1064–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voigt L, Haq SA, Mitre CA, et al. Effect of obstructive sleep apnea on QT dispersion: a potential mechanism of sudden cardiac death. Cardiology. 2011;118:68–73. doi: 10.1159/000324796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo K, Kurita T, Inagaki M, et al. The circadian pattern of the development of ventricular fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:465–470. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gami AS, Howard DE, Olson EJ, et al. Day-night pattern of sudden death in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1206–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MC, Rohtla KM, Lavery CE, et al. Meta-analysis of the morning excess of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1512–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bitter T, Westerheide N, Prinz C, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and obstructive sleep apnoea are independent risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias requiring appropriate cardioverter-defibrillator therapies in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:61–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan CM, Usui K, Floras JS, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on ventricular ectopy in heart failure patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2005;60:781–785. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. CANPAP Investigators. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP) Circulation. 2007;115:3173–3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padeletti M, Green P, Mooney AM, et al. Sleep disordered breathing in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure. Sleep Med. 2009;10:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gami AS, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otto ME, Belohlavek M, Romero-Corral A, et al. Comparison of cardiac structural and functional changes in obese otherwise healthy adults with versus without obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1298–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padeletti L, Gensini GF, Pieragnoli P, et al. The risk profile for obstructive sleep apnea does not affect the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:727–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jelic S, Padeletti M, Kawut SM, et al. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and repair capacity of the vascular endothelium in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2008;117:2270–2278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leftheriotis DI, Fountoulaki KT, Flevari PG, et al. The predictive value of inflammatory and oxidative markers following the successful cardioversion of persistent lone atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drager LF, Polotsky VY, Lorenzi-Filho G. Obstructive sleep apnea: an emerging risk factor for atherosclerosis. Chest. 2011;140:534–542. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linz D, Schotten U, Neuberger HR, et al. Negative tracheal pressure during obstructive respiratory events promotes atrial fibrillation by vagal activation. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1436–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson IH, Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, et al. Atrial electrophysiology is altered by acute hypercapnia but not hypoxemia: implications for promotion of atrial fibrillation in pulmonary disease and sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghias M, Scherlag BJ, Lu Z, et al. The role of ganglionated plexi in apnea-related atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2075–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;107:2589–2594. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068337.25994.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bitter T, Nölker G, Vogt J, et al. Predictors of recurrence in patients undergoing cryoballoon ablation for treatment of atrial fibrillation: the independent role of sleep-disordered breathing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matiello M, Nadal M, Tamborero D, et al. Low efficacy of atrial fibrillation ablation in severe obstructive sleep apnoea patients. Europace. 2010;12:1084–1089. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoyer FF, Lickfett LM, Mittmann-Braun E, et al. High prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with resistant paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after pulmonary vein isolation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2010;29:37–41. doi: 10.1007/s10840-010-9502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel D, Mohanty P, Di Biase L, et al. Safety and efficacy of pulmonary vein antral isolation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: the impact of continuous positive airway pressure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:445–451. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.858381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chilukuri K, Dalal D, Gadrey S, et al. A prospective study evaluating the role of obesity and obstructive sleep apnea for outcomes after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:521–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jongnarangsin K, Chugh A, Good E, et al. Body mass index, obstructive sleep apnea, and outcomes of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:668–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng CY, Liu T, Shehata M, et al. Meta-analysis of obstructive sleep apnea as predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson KG, Johnson DC. Obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for stroke and atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;138:239. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yazdan-Ashoori P, Baranchuk A. Obstructive sleep apnea may increase the risk of stroke in AF patients: refining the CHADS2 score. Int J Cardiol. 2011;146:131–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwillich C, Devlin T, White D, et al. Bradycardia during sleep apnea. Characteristics and mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1982;69:1286–1292. doi: 10.1172/JCI110568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serafini A, Dolso P, Gigli GL, et al. Rem sleep brady-arrhythmias: an indication to pacemaker implantation? Sleep Med. 2012;13:759–762. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein AE, Dimarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: executive summary. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:934–955. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garrigue S, Pépin JL, Defaye P, et al. High prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome in patients with long-term pacing: the European Multicenter Polysomnographic Study. Circulation. 2007;115:1703–1709. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrigue S, Bordier P, Jaïs P, et al. Benefit of atrial pacing in sleep apnea syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:404–412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baranchuk A, Healey JS, Simpson CS, et al. Atrial overdrive pacing in sleep apnoea: a meta-analysis. Europace. 2009;11:1037–1040. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi VA, Stradling JR, Kohler M. Effects of obstructive sleep apnoea on heart rhythm. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:1439–1451. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spicuzza L, Bernardi L, Calciati A, Di Maria GU. Autonomic modulation of heart rate during obstructive versus central apneas in patients with sleepdisordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:902–910. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200201-006OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Passino C, Sleight P, Valle F, Spadacini G, Leuzzi S, Bernardi L. Lack of peripheral modulation by analysis of heart rate variability activity during apneas in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H123–H129. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holty JE, Guilleminault C. REM-related bradyarrhythmia syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.La Rovere MT, Pinna GD, Hohnloser SH, et al. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability in the identification of patients at risk for life-threatening arrhythmias. Implications for clinical trials. Circulation. 2001;103:2072–2077. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.16.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lown B, Tykocinski M, Garfein A, Brooks P. Sleep and ventricular premature beats. Circulation. 1973;48:691–701. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.48.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1897–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI118235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trinder J, Merson R, Rosenberg JI, et al. Pathophysiological interactions of ventilation, arousals, and blood heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:808–813. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9806080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.La Rovere MT, Bigger JT, Jr, Marcus FI, et al. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1998;351:478–484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giannoni A, Emdin M, Poletti R, et al. Clinical significance of chemosensitivity in chronic heart failure: influence on neurohormonal derangement, Cheyne-Stokes respiration and arrhythmias. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:489–497. doi: 10.1042/CS20070292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu K, Chemla D, Roisman G, et al. Overnight heart rate variability in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a time and frequency domain study. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39:901–908. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Janssens W, Willems R, Pevernagie, et al. REM sleep-related bradyarrhythmia syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2007;11:195e9. doi: 10.1007/s11325-007-0105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verrier RL, Josephson ME. Impact of sleep on arrhythmogenesis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:450–459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.867028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato F, Nishimura M, Shinano H, et al. Heart rate during obstructive sleep apnea depends on individual hypoxic chemosensitivity of the carotid body. Circulation. 1997;96:274–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Douglas NJ, White DP, Weil JV, et al. Hypoxic ventilatory response during sleep in normal man. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:286–289. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]