Abstract

Calcium signaling is a ubiquitous and versatile process involved in nearly every cellular process, and exploitation of host calcium signals is a common strategy used by viruses to facilitate replication and cause disease. Small molecule fluorescent calcium dyes have been used by many to examine changes in host cell calcium signaling and calcium channel activation during virus infections, but disadvantages of these dyes, including poor loading and poor long-term retention, complicate analysis of calcium imaging in virus-infected cells due to changes in cell physiology and membrane integrity. The recent expansion of genetically-encoded calcium indicators (GECIs), including blue and red-shifted color variants and variants with calcium affinities appropriate for calcium storage organelles like the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), make the use of GECIs an attractive alternative for calcium imaging in the context of virus infections. Here we describe the development and testing of cell lines stably expressing both green cytoplasmic (GCaMP5G and GCaMP6s) and red ER-targeted (RCEPIAer) GECIs. Using three viruses (rotavirus, poliovirus and respiratory syncytial virus) previously shown to disrupt host calcium homeostasis, we show the GECI cell lines can be used to detect simultaneous cytoplasmic and ER calcium signals. Further, we demonstrate the GECI expression has sufficient stability to enable long-term confocal imaging of both cytoplasmic and ER calcium during the course of virus infections.

Keywords: GCaMP5G, GCaMP6s, RCEPIAer, endoplasmic reticulum, rotavirus, enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus

1. Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous eukaryotic secondary messenger involved in many cellular signal transduction pathways that control critical cellular processes. The importance of Ca2+ signaling and control of intracellular Ca2+ levels is highlighted by the large number of Ca2+ channels, pumps, transporters, buffering proteins, and Ca2+-responsive signaling proteins evolved to transduce these signals (1). As obligate intracellular parasites, viruses have evolved a variety of mechanisms to exploit host cell Ca2+ signaling, which provides a replication advantage and is often an underlying cause of virus pathogenesis (2–4). The specific changes in Ca2+ homeostasis are different between different viral systems, but in general viruses often cause an elevation in the concentration of cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) in conjunction with either depletion of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ([Ca2+]ER) stores [e.g., rotavirus (RV)] or elevation of [Ca2+]ER leading to disruption in Ca2+ signaling between the ER and mitochondria (e.g., hepatitis B virus) (5–8). More recent studies have demonstrated that virus-induced Ca2+ signaling can activate cellular processes, such as store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), fluid secretion to cause diarrhea and serotonin release to cause vomiting, activation of the inflammasome leading to proinflammatory cytokine release, induction of the autophagy pathway, and disruption of the host cell’s cytoskeleton (9). To characterize the roles Ca2+ signaling plays in virus replication and pathogenesis for these viruses, virologists have capitalized on the development of live cell Ca2+ imaging technology to track changes in Ca2+ levels during infection and to determine the molecular mechanisms used by viruses to induce these signals.

1.1. Live cell calcium imaging technology

Ca2+ signals are regulated both in terms of magnitude (how large was the Ca2+ flux) and time (how long does the flux last). In order to study both aspects of Ca2+ signaling, a wide range of fluorescent Ca2+ indicators have been developed to enable real time observations of changes in Ca2+ levels [reviewed in (10)]. All Ca2+ indicators are based upon fluorescent molecules that bind Ca2+ ions and have different spectral properties between the Ca2+-free and the Ca2+-bound states. There are two classes of fluorescent Ca2+ indicators: [1] small molecule dyes that are loaded into target cells and [2] genetically-encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECIs) that are engineered fluorescent proteins that are expressed within target cells. Both classes of indicators are briefly reviewed below.

1.1.1. Small molecule dyes

Small molecule fluorescent Ca2+ indicators were first developed in the early 1980s and are a mainstay for live-cell Ca2+ imaging by researchers due to their availability and versatility (11). There is a large variety of indicators to choose from, including: [1] single-wavelength dyes: Fluo-4 (and similar derivatives, Fluo-2, Fluo-8), [2] dual excitation dyes: Fura-2 (typically used for microscopy), and [3] dual emission dyes: Indo-1 (typically used for flow cytometry). The popularity of small molecule dyes is mainly due to their being readily available from several commercial sources, and relative ease for intracellular loading of the acetoxymethyl ester (AM)-modified versions.

Many Ca2+ imaging studies of virus infections have used the small molecule Ca2+ indicator dyes, primarily to track elevation of [Ca2+]c over time using Fura-2 or Fluo-4 (12–14). We have also used Indo-1 and Fluo-2 dyes to monitor [Ca2+]c in cells expressing wild-type or mutant versions of the RV viroporin (viral ion channel) nonstructural protein 4 (NSP4) by flow cytometry (15, 16). However, there are several drawbacks to Ca2+ indicator dyes, including poor loading into some cell types, a tendency to become compartmentalized within subcellular organelles, and having poor retention or being subject to active efflux over time. Additionally, photobleaching that occurs over time limits the number of viable indicators that can be used, as they must be highly photostable. These potential abnormalities in dye loading/retention and dye photobleaching can be exacerbated due to the cytopathic effects of virus infection, which led us to explore GECIs as alternative indicators for Ca2+ imaging in virus-infected cells.

1.1.2. Genetically-encoded calcium indicators

GECIs are engineered hybrids between a fluorescent protein and a specific Ca2+ binding moiety, such that the spectral properties of the fluorescent protein are modified upon Ca2+ binding. There are three classes of GECIs: [1] bioluminescent sensors based on the aequorin protein, [2] Forester resonance energy transfer (FRET) based two-color fluorescent protein indicators, and [3] single fluorescent protein-based indicators. While there are many varieties of these GECIs [reviewed in (10, 17)], the function of both single color and the FRET based sensors are based on a similar mechanism, which uses a Ca2+ responsive element [typically calmodulin (CaM) and the M13 CaM-binding peptide] inserted into a fluorescent protein. In the case of the FRET based sensors, the CaM-M13 motif is inserted between CFP/YFP FRET pairs, such that upon Ca2+ binding the CaM conformational change brings CFP and YFP closer together resulting in increased FRET efficiency. In the case of the single color sensors, CaM and M13 are inserted at opposite termini of a circularly permuted (and therefore destabilized) fluorescent protein. Upon Ca2+ binding the N- and C- termini associate, stabilizing the chromophore and increasing the fluorescence emission (17).

The most commonly used GECIs used for imaging the relatively low Ca2+ levels found in the cytoplasm (~100 nM basal Ca2+) are the green fluorescent protein (GFP) based GCaMPs and the related G-GECO1 variants (18, 19). These GECIs have low KD values (GCaMP5G, 0.45 µM; GCaMP6s, 0.144 µM; and G-GECO1, 0.75 µM) suitable for measuring cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics (~100 – 1000 nM) during Ca2+ signaling (1). These have been successfully used for Ca2+ imaging in cell lines, as well as in vivo in worms, flies, and mice (20). Plasmid vectors of popular green GECIs are available on Addgene, and commercially available adenovirus vectors (Vector BioLabs, Malvern, PA) or adeno-associated virus vectors (University of Pennsylvania Vector Core) have been made. Red-shifted (RCaMP1, RGECO1, and O-GECO) variants have been developed and are available through Addgene (21). Fewer blue-shifted GECIs also have been developed, and they have narrower dynamic ranges (~2–8 fold) than the green and red GECIs (19). Finally, the potential of GECIs for both in vitro and in vivo Ca2+ imaging has led to the rapid development and specialization of different GECIs, including optimization of the indicators’ affinity for Ca2+ and addition of subcellular targeting motifs to make them appropriate for Ca2+ storage organelles (Ca2+ ranges between 100–1000 µM) such as the ER and mitochondria (CEPIA). Several ER-targeted GECIs have recently been developed (KD ~600 µM) and are available as both green (GCEPIAer) and red-shifted (RCEPIAer) counterparts (22–24).

We have previously used transient expression GCaMP5G, a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-based GECI, to measure changes in [Ca2+]c induced by RV NSP4 (8). Further, several previous studies have used ER or Golgi-targeted GECIs to examine Ca2+ in cells expressing the picornavirus 2B viroporin protein (25–27). However, the use of GECIs to monitor Ca2+ dynamics in virus-infected cells has not been reported. Thus, we have developed lentiviral vectors and methods to establish cell lines that stably express both cytoplasmic green (GCaMP5G or GCaMP6s) and ER-targeted red (RCEPIAer) GECIs. The chosen GECIs were previously developed and characterized in cell lines and some cases for in vivo imaging (18, 20, 22). These cell lines we have developed enable simultaneous measurements of both cytoplasmic and ER Ca2+ levels, and can be used to investigate virus-induced changes in Ca2+ signaling, which we validate using three different viruses (RV, poliovirus and respiratory syncytial virus). Finally, the stable expression of these GECIs enables the use of confocal microscopy for long-term live cell Ca2+ imaging during the course of virus infections.

2. Materials and methods

General methods for the development of the GECI cell lines are outlined below and specific reagents are listed in Table 1. In general, the reagents listed have worked well for us, but likely can be substituted with similar reagents at the investigators discretion.

Table 1.

Reagents used for development of the GECI cell lines.

| Tissue Culture | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name of Reagent | Manufacturer | Catalog Number |

| Corning® 100mm TC-Treated Culture Dish | Corning | 430167 |

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) high glucose | Sigma-Aldrich | D6429 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | LifeTechnologies | 16000-044 |

| 0.25% Trypsin EDTA | LifeTechnologies | 25200-056 |

| 1M HEPES buffer (15mM final) | LifeTechnologies | 15630080 |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin solution | LifeTechnologies | 15240-062 |

| Imaging | ||

| Name of Reagent | Manufacturer | Catalog Number |

| 96-well μ-clear Optiplate | Greiner Bio-One | 655090 |

| FluoroBright DMEM | LifeTechnologies | A18967-01 |

| 16% Paraformaldehyde | ThermoScientific (Pierce) | PI28906 |

| adenosine triphosphate (ATP) | Sigma Aldrich | A9187-1G |

| DMSO | Sigma Aldrich | D8418-250ML |

| 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate | Tocris | 1224 |

| KB-R7943 mesylate | Tocris | 1244 |

| Lentivirus Packaging and Transduction | ||

| MAX Efficiency Stbl2 Competent E. coli | LifeTechnologies | 10268-019 |

| Stellar Competent E. coli | Clontech | 636766 |

| HiSpeed Plasmid Maxi Kit (25) | Qiagen | 12663 |

| Poly-D-Lysine | Cultrex | 3439-100-01 |

| Opti-MEM | LifeTechnologies | 11058-021 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | LifeTechnologies | 11668-019 |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Polyscience Inc. | 23966-2 |

| Polybrene | Santa Cruz Biotech | sc-134220 |

| Puromycin dihydrochloride | LifeTechnologies | A1113802 |

| Hygromycin B | LifeTechnologies | 10687010 |

| Vectors | ||

| Constructs | Source | Addgene No. |

| pGP-CMV-GCaMP5G | Addgene | 31788 |

| pGP-CMV-GCaMP6s | Addgene | 40753 |

| pCMV-RCEPIAer | Addgene | 58216 |

| pLVX-Puro | Clontech | 632164 |

| pLVX-IRES-Hyg | Clontech | 632182 |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | 12260 |

| pCMV-VSV-G | Addgene | 8454 |

2.1. Cell lines and culture conditions

MA104 cells (African Green Monkey kidney cell line, ATCC CRL-2378.1) and HEK293FT cells were a kind gift from Dr. Mary Estes, Baylor College of Medicine. HeLa cells were a kind gift from Rick Lloyd, Baylor College of Medicine. Cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, MEM non-essential amino acids, and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2.

2.2. Vector development, cloning and preparation

Vectors pGP-CMV-GCaMP5G (Addgene plasmid #31788) and pGP-CMV-GCaMP6s (Addgene plasmid #40753) were kind gifts from Dr. Douglas Kim. The vector pCMV-R-CEPIAer (Addgene plasmid # 58216) was a kind gift from Masamitsu Iino. Lentivirus vectors were generated by subcloning the GCaMP5G or GCaMP6s genes into pLVX-puro and RCEPIAer into pLVX-IRES-Hygro using standard molecular cloning procedures. Expression vectors were propagated in DH5α or NEB 5α™ E. coli and lentivirus vectors were propagated in either Stellar™ or Stbl2™ E. coli according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Maxipreps were produced by inoculating a 5 mL LB broth culture, supplemented with either ampicillin or kanamycin as appropriate, with a single colony from a LB-agar plate streak out, and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking in 15 mL tubes with loose caps. The 5 mL culture was used to inoculate 200 mL of LB broth (with ampicillin or kanamycin) and again grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. Plasmids were purified using the Hi-Speed Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Vectors for lentivirus packaging used were psPAX2, a gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #12260), and a pCMV-VSV-G, a gift from Bob Weinberg (Addgene plasmid #8454). These were propagated by transforming Stbl2 E. coli and plated on LB-agar plates with ampicillin according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Well isolated colonies were directly inoculated into 200 mL LB with ampicillin and incubated at 37°C overnight with shaking. Plasmids were purified using the Hi-Speed Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Often yields of these plasmids are quite low, so we have found use of freshly transformed Stbl2 (or similar) E. coli critical for higher yields.

2.3. Lentivirus packaging

We have used a variety of systems for packaging of VSV-G pseudotyped lentivirus vectors, including our in-house core lab (Vector Development Core Lab, BCM, Houston, TX), commercial services (Cyagen Bioscience Inc.), and doing our own packaging within the lab. All of these have been successful, and we have included our protocol below. We now prefer producing our own vectors; however, optimizing high titer lentivirus vector yield may not be cost effective for labs that do not routinely use lentivirus or retrovirus vectors.

For packaging of the GECI lentivirus vectors, we have used both the Clontech Lenti-X system according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the second generation psPAX2/VSV-G system (available through Addgene), which is presented below. We have used both Lipofectamine 2000 and polyethylenimine (PEI) with good results, and the choice of transfection reagent is likely not critical.

Protocol

Split confluent HEK293FT cells and seed ~5 ×106 cells per 10-cm plate in 10 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin.

At 24 hours post seeding, the cells should be ~80–90% confluent to proceed with packaging.

- To a sterile Eppendorf tube, add the following reagents, then mix by inverting the tube 5 times and incubate 10 minutes at room temperature.

a. Opti-MEM 600 µL b. psPAX2 7 µg c. VSV-G 3 µg d. GECI vector 14 µg e. PEI (1ug/mL) 36 µL Without removing the media on the 10-cm plate, distribute the mixture drop-wise to the plate, tilt the plate to mix, and incubate at 37°C for 48 hours. Fluorescence should be detected by 24 hours post transfection and the transfection efficiency should be between 70–90% to expect high vector titers.

At ~48 hours post transfection, remove the media and filter through a 0.45 µm polyethersulfone (PES) filter, aliquot into single use vials and store at −80°C. Avoid freeze/thaw cycles, as this decreases viral titers.

A variety of methods can be used to determine the titer of the viral stocks, expressed as transduction units (TU) per mL. We frequently use Lenti-X GoStix as a rapid measure of good versus poor yields. Rough estimates of the titer are determined by transducing fresh HEK293FT cells, and determining the percent transduction by flow cytometry.

2.4. Transfection and/or transduction for stable GECI cell lines

We first generated stable lines expressing cytoplasmic GCaMPs, with GCaMP5G for MA104 (made prior to the release of GCaMP6s) and GCaMP6s for HeLa using lentivirus transduction (see protocol below). Then we introduced RCEPIAer by lentivirus transduction (MA104) and selected with hygromycin or plasmid transfection (HeLa) and selected with G418 (500 ug/mL). Since transfection protocols are common, they are not reviewed here. Our lentivirus transduction protocol is presented below, including special considerations for making GECI cell lines since they are functional biosensors and therefore much more dim than fluorescently labeled proteins.

Protocol

Seed MA104 or HeLa at ~5 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well plate in 3 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Incubate overnight.

Plan transductions for a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ~10–20. Higher MOIs can be used for difficult to transduce cells, but excess transduction could be detrimental to the cells, particularly due to the over-expression of the Ca2+ binding moieties in the GECIs. If the virus titer is low, it is better to use fewer cells (and therefore a smaller dish size, such as 5 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate) or to concentrate the virus, rather than doing a low MOI infection.

Mix DMEM + 10% FBS, lentivirus stock. Then, add 8 ug/mL polybrene. It is best to keep the inoculum volume as low as possible (1.5–2 mL for 6-well plate).

Remove the maintenance media from the cells and distribute the inoculum drop-wise onto the cells. Incubate overnight.

- Remove the inoculum and replace with fresh 10% FBS-DMEM. Monitor for GECI expression from 48–72 hours post-transduction.

- GECIs are not as bright as standard fluorescent proteins, particularly GCaMP5G/6s because basal cytoplasmic Ca2+ is maintained to low levels. Thus, expression is not as obvious as GFP/RFP positive controls early after transduction.

- When examining new transductions for fluorescence, it is helpful to replace the normal DMEM with phenol red-free media because the autofluorescence from phenol red masks the dim GCaMP signal. We commonly use FluoroBrite DMEM (LifeTechnologies), which is specialized high glucose DMEM for live-cell imaging.

Once fluorescence is detected (typically ~72 hours post-transduction), cells should be split 1:2 and selection drug added (GCaMP6s: 5 ug/mL puromycin; RCEPIAer: 100 ug/mL hygromycin). It is important to determine the minimal drug concentration needed for each cell line. Continue to grow cells with drug selection until the line is established.

If non-fluorescent/low fluorescent cells persist, then additional rounds of transduction can be performed or FACS sorting can be used to enrich for the desired expression levels, keeping in mind this is still a mixed population of cells. If a cloned cell line is desired, dilution cloning can be used to generate single-cell cloned sublines. However, it is important to note that lentivirus integration could inactivate genes important for the replication of some viruses and cloned cell lines should be compared to the parental cell line for normal virus replication prior to extensive studies.

The cell lines reported here were developed as follows:

MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells: We initially transduced with GCaMP5G lentivirus and after puromycin selection used FACS to enrich for the positive cells prior to transduction with the RCEPIAer-expressing lentivirus vector. Two rounds of RCEPIAer transduction (MOI 10) and selected with puromycin and hygromycin B to generate the reasonable RCEPIAer signal. Finally, this cell line was enriched for the top 50% RCEPIAer expressing cells by FACS. This step is particularly important for improving the uniformity of expression.

HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells: We initially transduced with GCaMP6s lentivirus and selected with puromycin. No FACS enrichment was required after the initial GCaMP6s transduction and selection. RCEPIAer was introduced using plasmid transfection by Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were selected with puromycin and G418 and then double-positive cells were enriched using FACS.

2.5. Live cell Ca2+ imaging

Once developed, the GECI-expressing cell lines have to be tested using known Ca2+ agonists to demonstrate expected fluorescence responses from the GECIs upon cell stimulation. Once proper GECI performance is validated, experiments comparing mock and virus-infected cells can be performed.

2.5.1. Validation and Ca2+ imaging of GECI cell lines

There are a number of commonly used Ca2+ agonists that work for testing GECI responses in most cells, including ATP (30–200 uM), histamine (30–100 uM), and carbarchol (30–100 uM). Further, it may be important to determine the dynamic range of each GECI for each given cell type, since resting Ca2+ levels vary between different cell lines. Calibrating GCaMP5G/GCaMP6s can be performed using a Ca2+ ionophore (e.g., ionomycin) and Ca2+-free or high Ca2+ buffers (17). However, in our hands 10 µM A23187 (a Ca2+ ionophore) in high Ca2+ Ringer’s buffer (20 mM Ca2+ final) caused an irreversible loss of RCEPIAer signal, suggesting this GECI is not stable under these conditions (data not shown). The group that developed RCEPIAer performed in vivo Ca2+ calibration of RCEPIAer in HeLa cells by first permeabilizing the plasma membrane with 150 µM β-escin and then adding various Ca2+-containing buffers in the presence of 3 µM ionomycin and 3 µM thapsigargin (22).

Below are general principles for setting up Ca2+ imaging experiments using example treatments typical for studies of RV and picornaviruses; however, the details of the treatment will be determined by the goal of the experiments. There are many suitable options for microscope/light source, culture plates and perfusion setup, so only a few details are presented here. A number of helpful reviews on the general principles and equipment for Ca2+ imaging are available (17, 28). It is important to note that while these GECIs can be imaged using standard GFP and mCherry filter sets, these may not provide the optimal signal-to-noise ratio needed for a given experiment. We found this to be true for RCEPIAer on our confocal microscope setup due to a relatively narrow emission filter, consistent with the spectrum reported by the creators of RCEPIAer (22). Thus, depending on the resolution needed for the purpose of an experiment, filters should be customized for the GECI being used if possible. Alternatively, GECI expression can be optimized by additional lentivirus transduction and/or FACS enrichment for better signal (see above).

2.5.2. Virus infections

Cells were seeded into black optical bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) ~24–48 hours prior to infection at 30,000 cells/well for MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer or 50,000 cells/well for HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer. Cells were washed using serum free FluoroBrite DMEM supplemented with 15 mM HEPES, sodium pyruvate and penicillin/streptomycin, then infected with RV (SA114F), poliovirus (PV; poliovirus type I, Mahoney strain), or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV; A/Tracy) at an MOI=10, except for those presented in Figure 3 where the MOI is indicated. Infections were done in a 30–50 µL final volume per well for 1 hour. For perfusion experiments, the cells were washed with FluoroBrite, 100 µL added to each well and incubated at 37°C. Imaging is typically performed at ~6–8 hours post-infection (hpi) for RV and 4–5 hpi for PV. For long-term imaging, after the 1 hour infection, 70 µL of FluoroBrite alone or for the Ca2+ channel blocker studies in the presence of 0.1% DMSO, or 50 µM 2-APB or 10 µM KB-R7943 (dissolved in DMSO) was added to bring the volume to 100 µL per well.

2.5.3. Calcium imaging with buffer perfusion

Proper data collection is the most critical aspect of high quality Ca2+ imaging experiments. While imaging of single color GECIs does not require very rapid filter changes, simultaneous two color imaging of different GECIs does require reasonably rapid filter switching. We use a Zeiss AxioObserver A1 inverted fluorescence microscope (on an anti-vibration air table) with a Sutter DG5 Illumination and Filter box. For dual GCaMP5G/6s and RCEPIAer imaging, we use the Zeiss filter set 56 HE. The excitation filters (GCaMP5G/6s: 470/27; RCEPIAer: 556/25) are placed in the DG5 filter box. The dichroic cube holds the beam splitter (DFT 490 + 575) and dual bandpass filter (DBP 512/30 + 630/98). Our scope is equipped with a CoolSNAP CCD camera (Photometrics Scientific Inc) and computer control of the DG5 filter box and data acquisition is done by MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices). Images for GCaMP5G and GCaMP6s used 200 millisecond (ms) snaps (Gain = 1, Binning = 3) and RCEPIAer used 500 ms snaps (Gain = 1, Binning = 3) using a 40× water immersion objective. However, many other suitable microscopes, lamps, and acquisition/analysis software are available (28). For buffer perfusion, we use a simple gravity feed system composed of 60 mL syringes (with plungers removed) clamped onto a ring-stand with tubing fed into a multiline manifold (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), and suction from the plate/well is through a standard vacuum trap.

For treatment of cells with ATP to induce a Ca2+ signal, cells were perfused for 3–5 minutes in normal Ringer’s buffer [160 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 using 1M NaOH] or FluoroBrite DMEM prior to image acquisition and image acquisition was started with normal Ringer’s buffer perfusion to measure basal fluorescence for 100–200 seconds. Then perfusion was changed to Ringer’s buffer containing ATP (MA104 cells: 250 µM; HeLa cells 30 µM) for ~100–150 seconds. Data was analyzed using ImageJ (29) by normalizing fluorescence intensity of selected regions of interest (ROIs) to the initial intensity value (F/F0), and graphs were produced using Excel (Microsoft, Redman, WA) or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All experiments were performed at least in triplicate with 3 or more replicates per condition.

2.5.4. Long-term live cell confocal Ca2+ imaging

For long-term confocal microscopy, cells were seeded into optical bottom 96-well plates and infected as described above. All of our live cell confocal imaging was performed using a Nikon A1-Rsi inverted confocal microscope with 40× objective (NA 0.95, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) in a unidirectional multi-track mode without averaging. Cells were maintained in a humidified, 5% CO2 environmental chamber at 37°C (OKOLab, Pozzuoli, Italy). A 488 nm Argon laser was used for GCaMP5G and GCaMP6s imaging with a 500–550 nm emission filter. A 561 nm diode laser was used for imaging RCEPIAer with a 570–620 nm emission filter. Laser intensities were set at 5% of the maximum output power (1.6 mW for 488 nm and 2.2 mW for 561 nm). The pinhole was set at 5 AU to get ~5µm optical slices and time-lapse images were collected for 14–15 hours at 2–3 minute interval (depending on the number of samples included in a given run). The more narrow emission filter on the confocal microscope is less optimal for RCEPIAer and resulted in somewhat lower signal resolution; however we needed to use this configuration in order to perform the GCaMP/RCEPIAer dual imaging experiments.

To determine the optimal emission range for RCEPIAer, we used the Nikon Spectral detector and found that a wider red-shifted emission (605–745 nm) provided better RCEPIAer resolution. Still images of RCEPIAer in Figures 1 and 4 were taken using a similar setup as described above; except the laser power was set to 10% of the maximum output power, the pinhole was set to 2 AU, and 4 frames averaged per image. For images obtained using the Spectrum Detector, the RCEPIAer emission was collected from 605–745 nm, which was more optimal for RCEPIAer than the 570–620 nm emission filter. All images were collected and processed using Nikon NIS-Element (Nikon Instruments, Japan) and saved in 12-bit format. Exported TIF files were analyzed using ImageJ (29).

3. Results

3.1. GCaMP/RCEPIAer cell lines

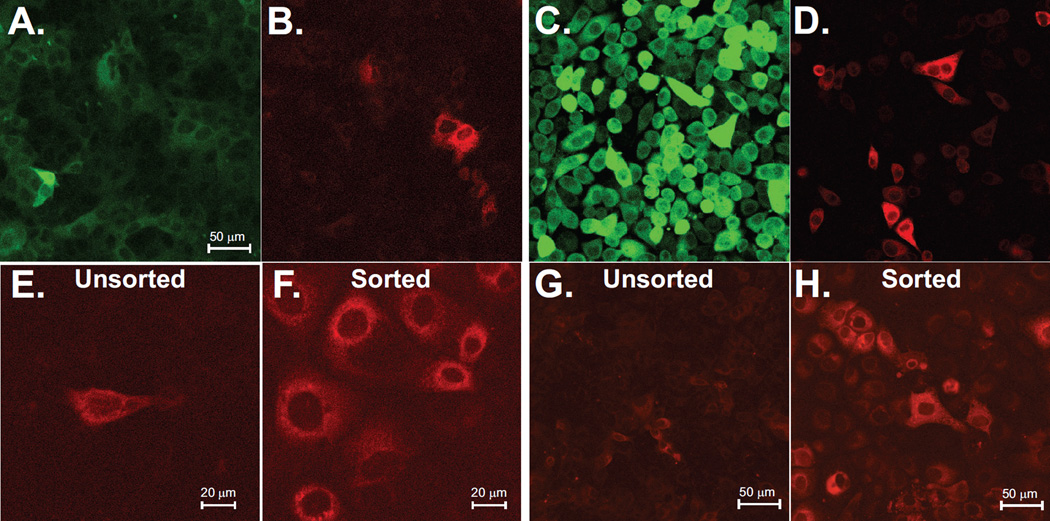

Our goal in developing the stable GCaMP/RCEPIAer double-positive cell lines was to take advantage of the ability to target different colored GECIs to the cytoplasm or ER, and then perform simultaneous Ca2+ measurements of both subcellular localizations during virus replication. Using lentivirus transduction and/or plasmid transfection, we have generated and characterized two different cell lines: MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer and HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer. In both cell lines, GCaMP5G and GCaMP6s were localized to the cytoplasm (Figure 1A and C) and RCEPIAer had a reticular distribution consistent with proper localization to the ER (Figure 1 B and D). Initially, the MA104 GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cell line had relatively low RCEPIAer signal in the majority of cells, with expression good enough for imaging on only about 30–50% of the cells (Figure 1B). To increase the uniformity and resolution, we enriched for double positive cells with the 50% brightest RCEPIAer expression by FACS. This increased the resolution of RCEPIAer and uniformity of strong expression (Figure 1F) compared to the unsorted cells (Figure 1E). Additionally, using a Spectral detector, we found that an emission filter with a wider/red-shifted emission range than standard tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)/mCherry filter cubes was better for imaging RCEPIA, with the best results being from ~690–700 nm. However, since standard cubes are more widely available and spectral detector capabilities are not compatible with two-color imaging, we performed imaging with the standardly available filter cubes (see the Materials and Methods section). Next, we performed live-cell Ca2+ imaging to detect concomitant changes in cytoplasmic and ER Ca2+ in uninfected and virus-infected cells. First, cells were equilibrated to FluoroBrite DMEM and then treated with ATP (250 µM for MA104, 30 µM for HeLa) by perfusion (Figure 2A–D). ATP treatment of MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells induced a strong increase in GCaMP5G with irregularly spaced oscillations and this was paired with an initial sharp decrease in RCEPIAer fluorescence and smaller magnitude decreases corresponding to the GCaMP5G oscillations (Figure 2A, arrows). A similar response was observed for ATP treatment of HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells; however, the Ca2+ oscillations are more regular in HeLa cells than in MA104 cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. Stable GECI cell lines.

Confocal microscopy of the established MA104 (A & B) and HeLa (C & D) cell lines for basal GCaMP5G (A), GCaMP6s (C) and RCEPIAer (B & D). Enrichment in RCEPIAer expressing cells by FACS is shown for unsorted (E) and sorted (F) cells. RCEPIAer signal was also improved using a wider filter emission range (605–745 nm) in both the unsorted (G) and sorted (H) cells.

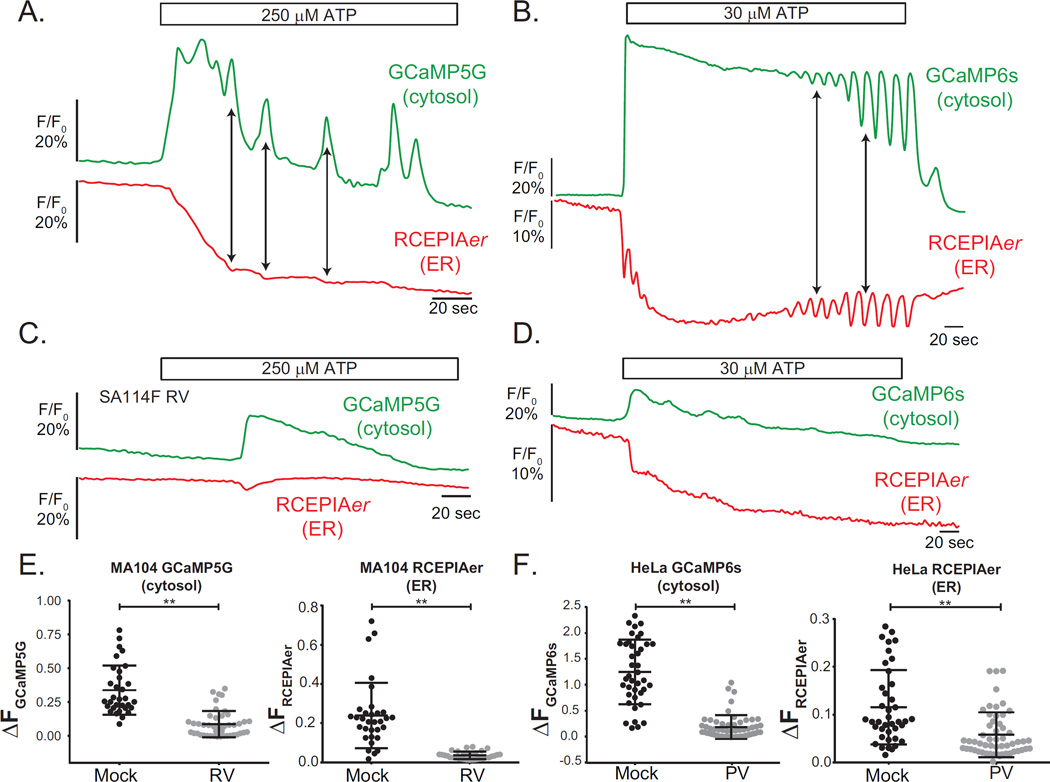

Figure 2. Evaluation of cytoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ responses in virus-infected GECI-expressing cells.

A–D. MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer (A & C) or HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer (B & D) were mock treated (A & B) or infected with RV (C) or PV (D). Cells were perfused with FluoroBrite DMEM and then treated with ATP for ~150 sec. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ increases paired with co-incident ER Ca2+ decreases are indicated by arrows. E. Relative change in GCaMP5G (left) or RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence after 250 µM ATP stimulation in mock (N=34) or RV-infected (N=44) cells showed delayed and reduced ATP responses in RV-infected cells. F. Relative change in GCaMP6s (left) or RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence after 30 µM ATP stimulation in mock (N=40) or PV-infected (N=56) showed reduced and dysregulated ATP-induced oscillations in PV-infected cells. **P < 0.0001. Each experiment was performed in triplicate with 3 replicates per condition.

3.2. Ca2+ imaging of virus-infected GCaMP/RCEPIAer cells

Both RV and PV deplete ER Ca2+ stores through expression of viroporins (RV NSP4 and PV 2B proteins) that target the ER and this reduces PLC/IP3-dependent Ca2+ signaling (9). We tested the response to ATP in RV-infected MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer and poliovirus-infected HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells and the results of a representative experiment are shown in Figure 2. As expected, RV-infected MA104 cells had a blunted and delayed response to ATP with no detectable oscillations (Figure 2C). The relative GCaMP5G and RCEPIAer response was significantly lower in RV-infected than mock cells (Figure 2E). PV-infected HeLa cells also had a severely blunted ATP response with small irregular oscillations (Figure 2D). Significantly lower GCaMP6s and RCEPIAer changes were detected from PV-infected than from mock cells (Figure 2F).

3.3. Long-term live cell calcium imaging

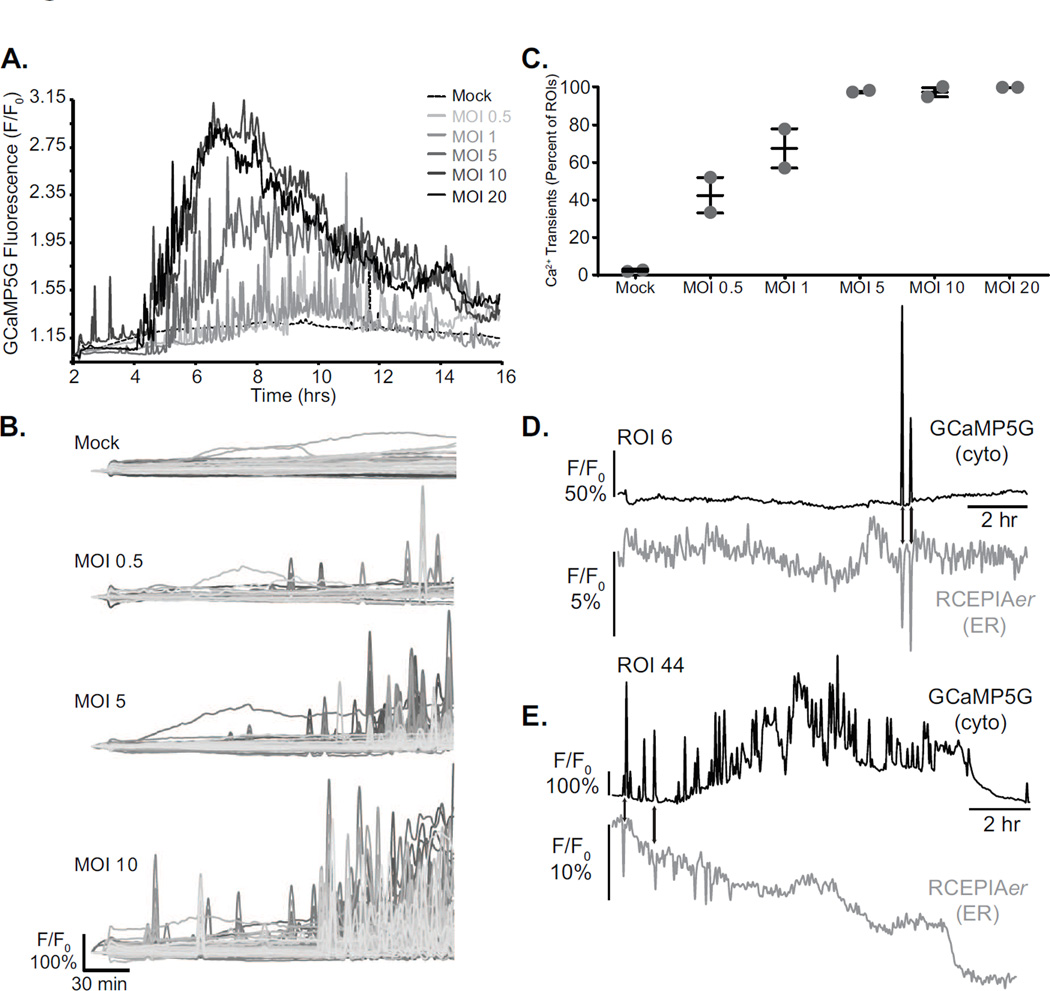

3.3.1. Rotavirus-induced calcium signaling

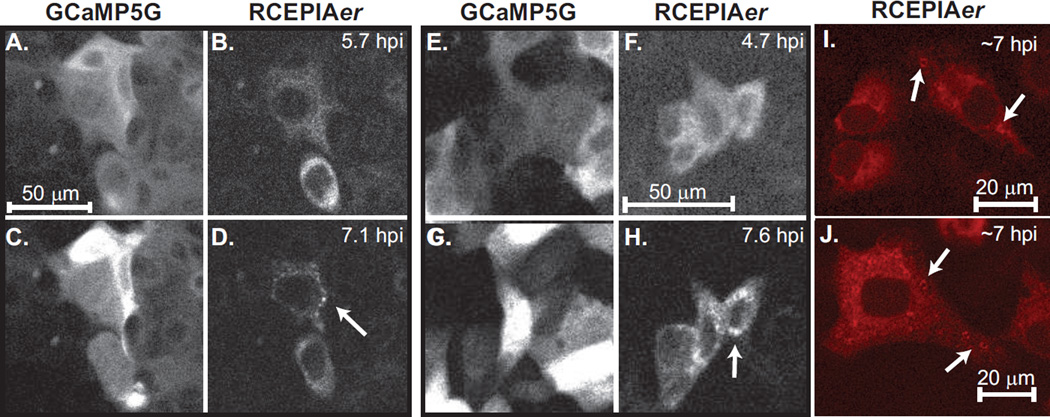

Unlike small molecule dyes, GECI technology enables stable indicator expression and therefore the potential to image changes in cytoplasmic and ER Ca2+ throughout an entire virus infection. To test this we mock treated or RV infected MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells at different multiplicities of infection (MOI= 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 20) and imaged them 2.5 minute intervals from ~2–14 hpi by confocal microscopy. The cells were maintained in a humidified, 5% CO2 and 37°C environmental chamber throughout the entire imaging run. For each experiment the infection was performed in duplicate and experiments have been performed at least twice. Representative analyses are presented below and movies are available in the online Supplemental material. Mock infected cells showed normal growth throughout the entire time course with only a few GCaMP5G cytoplasmic or RCEPIAer Ca2+ transients (Supplemental Movie 1, MA104_Mock). In contrast, RV-infected cells show numerous Ca2+ transients beginning as early as 2.5 hpi and substantial elevation in GCaMP5G signal between 4–6 hpi that lasts until cell death. Transients of reduced RCEPIAer were observed and coincided with the appearance of the GCaMP5G Ca2+ transients (Supplemental movie 2, MA104_RV_MOI10). The high degree of cell movement and shape change made accurate single-cell region-of-interest (ROI) analysis impossible, so we instead graphed the average GCaMP5G signal for the entire field-of-view (Figure 3A). Mock infected cells showed only a few, small magnitude Ca2+ transients, one large Ca2+ transient (~12 hr.), and a shallow steady-state increase in GCaMP5G signal up to 10 hpi, perhaps representing an increase in the number of cells in the field-of-view from continued cell division. In all RV-infected cells, a steady-state elevation in [Ca2+]c occurred by 6 hpi with strong Ca2+ transients observed even earlier (Figure 3A and Supplemental movie 3, MA104_RV_MOIs). To measure the number and magnitude of early (2–6 hpi) Ca2+ transients more accurately, we reanalyzed the images with an array of 100 square ROIs from ~2–6 hpi. The ROI array consists of a 10×10 array, with each ROI being 51×51 pixels, such that this encompassed the entire field-of-view. The number and magnitude of the Ca2+ transients increased with a higher RV dose (Figure 3B), which showed a clear dose-dependence (Figure 3C). Finally, although RCEPIAer had a relative weak signal in the majority of cells, we were able to observe concomitant changes in GCaMP5G and RCEPIAer Ca2+ during spontaneous Ca2+ transients in mock-infected cells (Figure 3D). Further, the early Ca2+ transients involved ER Ca2+ release since GCaMP5G spikes were concomitant with RCEPIAer drops (Figure 3E). Later during infection there was a decrease in RCEPIAer signal and loss of strong correlation between GCaMP5G and RCEPIAer signal changes. In a subset of cells, we observed that the elevation of [Ca2+]c (Figure 4A versus 4C and 4E versus 4G) correlated with a re-organization of the diffuse ER localized RCEPIAer protein (Figure4B and 4F) into discrete puncta (Figure4D and 4H). In a separate experiment using the sorted MA104 GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells, we were able to observe RCEPIAer localized to ring-like structures (Figure 4I–J), which are morphologically similar to the ER-derived membranes around RV replication complexes (called viroplasms) (30); however, since this was not seen in all infected cells (even at high MOIs) it is also possible this is related to RV-induced disruption in ER-Golgi trafficking (31). Alternatively, and a possible caveat for the use of GECIs in all viral systems, is the recent identification of a CaM binding site on the RV structural protein VP6 (32), which could cause sequestration of RCEPIAer. At the resolution used for these experiments, we were not able to determine whether the diffuse and punctate RCEPIAer displayed different responses to Ca2+ transients, which would indicate they are distinct pools within the cell.

Figure 3. Long-term live cell Ca2+ imaging during rotavirus infection.

A. Relative GCaMP5G fluorescence of RV-infected MA104 cells from ~2–14 hpi. Cells were infected with the indicated MOI in duplicate. Traces represent the average fluorescence intensity from the field of view of one of the two wells. B. The GCaMP5G fluorescence intensity from 2–6 hpi of mock treated cells (top), or cells infected with different MOIs (as indicated) were analyzed using a 10×10 ROI array. Ca2+ transients are observed as spikes in the individual traces. C. The percent of ROIs from the 10×10 array analyses in panel B are graphed as a function of the MOI. Values are shown with the mean +/− the standard error of the mean. D. Relative GECI fluorescence of concomitant cytoplasmic/ER Ca2+ transients in mock (D) or RV-infected (E) MA104 cells detected with GCaMP5G (black line) and RCEPIAer (grey line), respectively. Data are representative of two experiments with at least two replicates per MOI in each experiment.

Figure 4. Changes in RCEPIAer localization during rotavirus infection.

Examples (A–D and E–H) of RCEPIAer redistribution into discrete puncta during the long-term imaging of RV infection. The images were taken during the long-term confocal microscopy runs. GCaMP5G (A & C, E & G) shows the increase in fluorescence as the infection progresses. RCEPIAer signal is diffuse in the ER at 5–6 hpi (B and F) but moves into discrete puncta structures (D and H, arrows) by 7–8 hpi. RV-induced puncta were observed as ring-like structures at ~7 hpi in the sorted MA104 GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells (I & J, arrows).

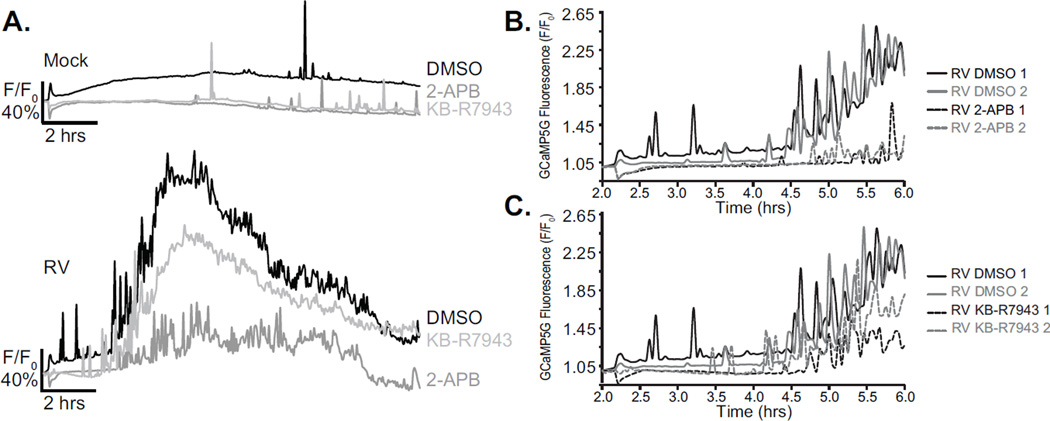

3.3.2. GECI calcium imaging for drug screening

Several pathways for Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane are predicted to be activated by RV, including store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) and activation of the sodium/calcium exchanger (NCX) in reverse mode (NCXrev), which results in calcium influx into the cytoplasm (8, 13). Next, we used this long-term live cell Ca2+ imaging method to assess the effect of Ca2+ channel blockers that antagonize these Ca2+ entry pathways on RV-induced Ca2+ signaling. Cells were mock treated or RV-infected (MOI 10), as described above, and then at 1 hpi treated with the non-specific SOCE blocker 2-APB (50 µM) or the NCXrev blocker KB-R7943 (10 µM) and imaged as before (Supplemental movie 4, MA104_RV_Ca2+Blockers). GCaMP5G fluorescence in mock-infected cells (Figure 5A, top) treated with either 2-APB (dark grey dashed line) or KB-R7943 (light grey dashed line) was lower than cells treated with DMSO alone (black dashed line), as would be expected for inhibition of potential Ca2+ entry pathways. Treatment of RV-infected cells with 2-APB (dark grey line) or KB-R7943 (light grey line) showed substantial decreases in the steady-state elevation in [Ca2+]c (Figure 5A, bottom), with 2-APB treatment being much more effective than KB-R7943. Further, treatment with 2-APB delayed the onset and reduced the magnitude of RV-induced Ca2+ transients between 2–6 hpi (Figure 5B). KB-R7943 treatment caused a minor reduction in the magnitude of the early Ca2+ transients but did not delay the onset of these signals (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Calcium channel blockers reduce rotavirus-induced Ca2+ signals.

A. Average traces from a representative well for mock (top) or RV-infected (bottom) cells treated with DMSO (black), 2-APB (dark grey), and KB-R7943 (light grey). B–C. RV-induced Ca2+ transients were measured by plotting the relative GCaMP5G fluorescence from RV-infected (2–6 hpi) cells mock treated (solid lines) or treated with 50 µM 2-APB (B, dashed lines) or 10 µM KB-R7943 (C, dashed lines). Each experiment was performed at least 2 times with 2–3 replicates per drug treatment.

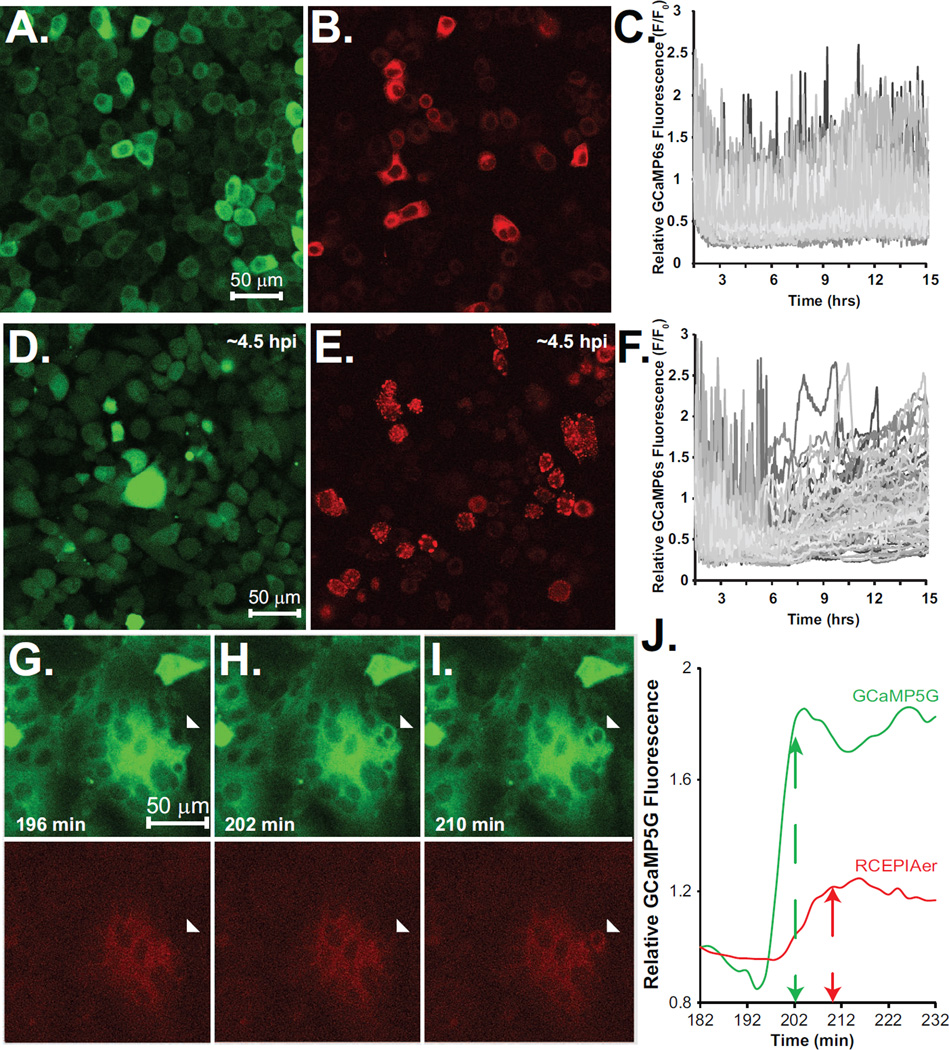

3.3.3. Long-term Ca2+ imaging of poliovirus and respiratory syncytial virus

We next sought to determine whether these GECI cell lines would be useful to monitor Ca2+ signaling induced by other viruses. We tested PV infection of the HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells and RSV infection of the MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells using the long-term live cell confocal microscopy method described above. HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells were mock treated or PV infected at an MOI 10 and imaged at 2:45 minute intervals from ~1.5 – 15 hpi. Mock infected HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells displayed a very high basal level of Ca2+, spontaneous fluxuations in [Ca2+]c (Supplemental movie 5, HeLa_Mock), as well as reticular distribution of RCEPIAer (Figure 6A &B). In PV-infected cells (Figure 6D–E), the [Ca2+]c fluxuations became erratic between 3–4 hpi (Figure 6F, Supplemental movie 6, HeLa_PV), which is concomitant with the rearrangement of the RCEPIAer signal into punctate structures (Figure 6E). By 6–10 hpi, apoptotic cell death can be observed; however, in many cells small magnitude subcellular Ca2+ transients can be observed.

Figure 6. Long-term Ca2+ imaging of poliovirus and respiratory syncytial virus-infected cells.

A–E. Confocal images of mock (A–B) or poliovirus-infected (D–E) HeLa-GCaMP6s/RCEPIAer cells. Cytoplasmic GCaMP6s (A and D) and ER-localized RCEPIAer (B–E). A 10×10 ROI array was used to examine relative GCaMP6s changes for [Ca2+]c in mock (C) and PV-infected (F) cells. G–I. Sequence of confocal images of RSV-infected MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells highlighting a cell fusion event (arrow head). J. Analysis of the cell fusion illustrating a spike in [Ca2+]c (GCaMP5G, green) precedes the elevation in [Ca2+]ER (RCEPIAer, red). Each long-term imaging experiment was performed twice with at least 3 replicates per infection.

Next we observed RSV-infected MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells at ~24–38 hpi, a time during which syncytia formation and cell death occur (Supplemental movie 7, MA104_RSV). MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells were infected at an MOI 10 and imaged at 2 minute intervals from ~24–38 hpi. We observed greater GCaMP5G signal, indicating elevated [Ca2+]c, as well as Ca2+ flux during cell fusions events (Figure 6G–I) first into the cytoplasm (GCaMP5G, upper panels) and then into the ER (RCEPIAer, lower panels). Single cell analysis was performed on a cell during the process of fusion with a multinucleated giant cell. We found an ~8 min delay between the increase in [Ca2+]c and elevation in [Ca2+]ER (Figure 6J). By approximately 28 hpi the steady-state [Ca2+]c begins to increase rapidly until ~34 hpi when large localized Ca2+ transients begin that lead to massive Ca2+ flux immediately preceding cell death (Supplemental movie 7).

4. Discussion

The recent work to develop more versatile GECIs, including greater dynamic range, color variants and Ca2+ affinities, which are appropriate for Ca2+ storage organelles, has opened the possibility to establish stable cell lines and knock-in animals for real-time monitoring of Ca2+ signing (20). Similarly, GECI technology is an attractive alternative to small molecule Ca2+ dyes for live cell Ca2+ imaging during virus infections. Here we describe the establishment and validation of stable GECI cells lines expressing both green cytoplasmic and red ER-localized GECIs and then used three different viruses that have been previously characterized to exploit Ca2+ homeostasis during virus replication (RV, PV, and RSV) to validate the use of GECIs in virus-infected cells (5, 14, 33). Using GECIs we are able to detect simultaneous cytoplasmic and ER Ca2+ fluxes induced by application of ATP, a Ca2+ agonist, and diminished responses in RV or PV-infected cells, similar to previous studies using Ca2+ dyes (25, 34).

GECIs are engineered biosensors based on fluorescent proteins and therefore exhibit greater long-term stability in cells than small molecule dyes, which enables long-term Ca2+ imaging experiments to be conducted during the course of virus infections and a more ‘hands-off’ approach for observing naturally developing Ca2+ signals. Using long-term live Ca2+ confocal microscopy imaging, we observed that RV induced a dose-dependent increase in both the steady-state [Ca2+]c and the number/magnitude of Ca2+ transients. Interestingly, even in cells infected with an MOI = 0.5, where only 20–30% of cells are expected to be infected, we observed numerous strong Ca2+ transients (Figure 3A & C) supporting the existence of a RV-induced paracrine signal that functions through a Ca2+ signaling pathway. The RV enterotoxin, which is a cleavage product of RV NSP4 that is secreted from RV-infected cells, is one possible candidate for such a paracrine signal because it binds to a receptor and elicits a phospholipase-C (PLC)-dependent Ca2+ transient from uninfected cells (35, 36). However, since typical PLC-dependent agonists (e.g., ATP, Figure 2) elicit reduced Ca2+ responses from RV-infected cells, the RV-induced Ca2+ transients observed in the long-term live cell imaging runs may also involve non-PLC-dependent signaling pathways (15). In addition to viral Ca2+ agonists, previous studies have identified SOCE and NCXrev as important host Ca2+ entry pathways exploited by RV to elevate [Ca2+]c. We found that both SOCE blocker 2-APB and NCXrev blocker KB-R7943 decreased the steady-state elevation in [Ca2+]c and magnitude of spontaneous Ca2+ transients observed in RV-infected MA104-GCaMP5G/RCEPIAer cells, similar to a previous study using small molecule Ca2+ dyes (13). While 2-APB is a blocker of the SOCE channel Orai1, this drug also targets other aspects of the SOCE pathway, including STIM1 puncta formation (37). Both activation of STIM1 and Ca2+ entry through SOCE have been observed in RV-infected cells, thus reduction of Ca2+ signaling by 2-APB using the GECI cell lines is consistent with previous studies; however, the ability to observe the Ca2+ signaling dynamics provides new information about when and how the Ca2+ signals manifest (8, 13).

Finally, we observed PV- and RSV-infected cells to demonstrate that GECI cell lines/technology can be applied to other viral systems, and other cell lines (e.g., HeLa cells). Of note, each of the viruses presented in this study showed dramatically different Ca2+ signaling phenotypes. For example RV caused an increase in Ca2+ transients but RSV elevated [Ca2+]c with few Ca2+ transients until just prior to cell death, and PV infection disrupted the normal Ca2+ oscillations of HeLa cells. Future studies using these GECI-expressing cell lines, as well as additional lines developed with other GECI varieties, will be able to further dissect the mechanisms by which viruses exploit ER Ca2+ signaling (10, 22, 23).

Supplementary Material

Mock-infected MA104 (treated with 0.1% DMSO) were imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RV at MOI 10 (treated with 0.1% DMSO) were imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RV at an MOI 10 (upper right), MOI 5 (upper left), MOI 1 (lower right) or MOI 0.5 (lower right) and imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RV at MOI 10, treated with 0.1% DMSO alone (vehicle control, left), 50 µM 2-APB, or 10 µM KB-R7943 at 1 hpi, and imaged for GCaMP5G at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

HeLa cells were imaged for GCaMP6s (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.75 min intervals from ~1.5–15 hpi.

HeLa cells were infected with PV at MOI 10 and then imaged for GCaMP6s (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.75 min intervals from ~1.5–15 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RSV at MOI 10 and then imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2 min intervals from ~24–37 hpi.

Highlights.

Genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) are now available in both green and red-shifted varients and designed for simultaneous imaging of cytoplasmic and ER Ca2+ signals.

GECIs have distinct advantages over traditional Ca2+ indicator dyes for long term and organellar Ca2+ imaging, particularly for imaging the Ca2+ dynamics during virus infections.

We used lentivirus transduction to establish stable cell lines (HeLa and MA104) expressing cytoplasmic GCaMP (green) and ER-targeted RCEPIAer (red) GECIs.

These cell lines enable real-time dynamics of virus-induced Ca2+ signaling to be observed in multiple viral systems (rotavirus, poliovirus and respiratory syncytial virus)

Using GECI-expressing cell lines to observe how Ca2+ signaling manifests during virus replication will provide key insights into viruses exploitation of Ca2+ signaling

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Light Microscopy Core Facilities of the Rice University Shared Equipment Authority (Houston, TX) for equipment use and technical support in performing the long-term live cell confocal Ca2+ imaging.. We also thank Dr. Mary Estes, Dr. George Rodney, and Dr. Sue Crawford for technical advice. This work was supported in part by NIH grants K01DK093657, Baylor College of Medicine new faculty seed funding, the American Gastroenterology Association Elsevier Pilot Grant, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center For AIDS Research CFAR, an NIH funded program (P30 AI027767) that was made possible by the following institutes: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, and OAR. FACS of cell lines was performed at the BCM Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core with funding from the NIH (AI036211, CA125123, and RR024574), and the expert assistance of Joel M. Sederstrom.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. doi:10.1038/35036035 [doi];35036035 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiz MC, Cohen J, Michelangeli F. Role of Ca2+in the replication and pathogenesis of rotavirus and other viral infections. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:137–149. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chami M, Oules B, Paterlini-Brechot P. Cytobiological consequences of calcium-signaling alterations induced by human viral proteins. Biochim. Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1344–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Frey TK, Yang JJ. Viral calciomics: interplays between Ca2+ and virus. Cell Calcium. 2009;46:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michelangeli F, Ruiz MC, del Castillo JR, Ludert JE, Liprandi F. Effect of rotavirus infection on intracellular calcium homeostasis in cultured cells. Virology. 1991;181:520–527. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90884-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zambrano JL, Diaz Y, Pena F, Vizzi E, Ruiz MC, Michelangeli F, Liprandi F, Ludert JE. Silencing of rotavirus NSP4 or VP7 expression reduces alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis induced by infection of cultured cells. J Virol. 2008;82:5815–5824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02719-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang B, Bouchard MJ. The hepatitis B virus X protein elevates cytosolic calcium signals by modulating mitochondrial calcium uptake. J Virol. 2012;86:313–327. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06442-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyser JM, Utama B, Crawford SE, Broughman JR, Estes MK. Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensor STIM1 and store-operated calcium entry by rotavirus requires NSP4 viroporin activity. J Virol. 2013;87:13579–13588. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02629-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyser JM, Estes MK. Annual Review of Virology. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-054846. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horikawa K. Recent progress in the development of genetically encoded Ca(2+) indicators. J Med. Invest. 2015;62:24–28. doi: 10.2152/jmi.62.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsien RY, Pozzan T, Rink TJ. Calcium homeostasis in intact lymphocytes: cytoplasmic free calcium monitored with a new, intracellularly trapped fluorescent indicator. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:325–334. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez JF, Ruiz MC, Chemello ME, Michelangeli F. Characterization of a membrane calcium pathway induced by rotavirus infection in cultured cells. J Virol. 1999;73:2481–2490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2481-2490.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz Y, Pena F, Aristimuno OC, Matteo L, De Agrela M, Chemello ME, Michelangeli F, Ruiz MC. Dissecting the Ca(2)(+) entry pathways induced by rotavirus infection and NSP4-EGFP expression in Cos-7 cells. Virus. Res. 2012;167:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Kuppeveld FJ, Hoenderop JG, Smeets RL, Willems PH, Dijkman HB, Galama JM, Melchers WJ. Coxsackievirus protein 2B modifies endoplasmic reticulum membrane and plasma membrane permeability and facilitates virus release. EMBO J. 1997;16:3519–3532. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyser JM, Collinson-Pautz MR, Utama B, Estes MK. Rotavirus disrupts calcium homeostasis by NSP4 viroporin activity. mBio. 2010;1 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00265-10. e00265-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyser JM, Utama B, Crawford SE, Estes MK. Genetic divergence of rotavirus nonstructural protein 4 results in distinct serogroup-specific viroporin activity and intracellular punctate structure morphologies. J Virol. 2012;86:4921–4934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06759-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCombs JE, Palmer AE. Measuring calcium dynamics in living cells with genetically encodable calcium indicators. Methods. 2008;46:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.015. doi:S1046-2023(08)00166-7 [pii];10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.015 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. doi:nature12354 [pii];10.1038/nature12354 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T, Campbell RE. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca(2)(+) indicators. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. doi:science.1208592 [pii];10.1126/science.1208592 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, Bargmann CI, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Looger LL. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. doi:nmeth.1398 [pii];10.1038/nmeth.1398 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindenburg L, Merkx M. Colorful calcium sensors. Chembiochem. 2012;13:349–351. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki J, Kanemaru K, Ishii K, Ohkura M, Okubo Y, Iino M. Imaging intraorganellar Ca2+ at subcellular resolution using CEPIA. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4153. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5153. doi:ncomms5153 [pii];10.1038/ncomms5153 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J, Prole DL, Shen Y, Lin Z, Gnanasekaran A, Liu Y, Chen L, Zhou H, Chen SR, Usachev YM, Taylor CW, Campbell RE. Red fluorescent genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators for use in mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. J. 2014;464:13–22. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140931. doi:BJ20140931 [pii];10.1042/BJ20140931 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang S, Wong HC, Wang ZM, Huang Y, Zou J, Zhuo Y, Pennati A, Gadda G, Delbono O, Yang JJ. Design and application of a class of sensors to monitor Ca2+ dynamics in high Ca2+ concentration cellular compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 2011;108:16265–16270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103015108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Jong AS, de Mattia F, Van Dommelen MM, Lanke K, Melchers WJ, Willems PH, van Kuppeveld FJ. Functional analysis of picornavirus 2B proteins: effects on calcium homeostasis and intracellular protein trafficking. J Virol. 2008;82:3782–3790. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02076-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Orba Y, Okada Y, Sunden Y, Kimura T, Tanaka S, Nagashima K, Hall WW, Sawa H. The human polyoma JC virus agnoprotein acts as a viroporin. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000801. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ito M, Yanagi Y, Ichinohe T. Encephalomyocarditis virus viroporin 2B activates NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002857. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Measuring calcium signaling using genetically targetable fluorescent indicators. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1057–1065. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.172. doi:nprot.2006.172 [pii];10.1038/nprot.2006.172 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins TJ. ImageJ for microscopy. Biotechniques. 2007;43:25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford SE, Hyser JM, Utama B, Estes MK. Autophagy hijacked through viroporin-activated calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta signaling is required for rotavirus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 2012;109:E3405–E3413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216539109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu A, Bellamy AR, Taylor JA. Immobilization of the early secretory pathway by a virus glycoprotein that binds to microtubules. EMBO J. 2000;19:6465–6474. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chattopadhyay S, Basak T, Nayak MK, Bhardwaj G, Mukherjee A, Bhowmick R, Sengupta S, Chakrabarti O, Chatterjee NS, Chawla-Sarkar M. Identification of cellular calcium binding protein calmodulin as a regulator of rotavirus A infection during comparative proteomic study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056655 [doi];PONE-D-12-24237 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shahrabadi MS, Lee PW. Calcium requirement for syncytium formation in HEp-2 cells by respiratory syncytial virus. J Clin. Microbiol. 1988;26:139–141. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.1.139-141.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz Y, Chemello ME, Pena F, Aristimuno OC, Zambrano JL, Rojas H, Bartoli F, Salazar L, Chwetzoff S, Sapin C, Trugnan G, Michelangeli F, Ruiz MC. Expression of nonstructural rotavirus protein NSP4 mimics Ca2+ homeostasis changes induced by rotavirus infection in cultured cells. J Virol. 2008;82:11331–11343. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00577-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang M, Zeng CQ, Morris AP, Estes MK. A functional NSP4 enterotoxin peptide secreted from rotavirus-infected cells. J Virol. 2000;74:11663–11670. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11663-11670.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo NS, Zeng CQ, Hyser JM, Utama B, Crawford SE, Kim KJ, Hook M, Estes MK. Inaugural article: integrins alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 are receptors for the rotavirus enterotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8811–8818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803934105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lefkimmiatis K, Srikanthan M, Maiellaro I, Moyer MP, Curci S, Hofer AM. Store-operated cyclic AMP signalling mediated by STIM1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:433–442. doi: 10.1038/ncb1850. doi:ncb1850 [pii];10.1038/ncb1850 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mock-infected MA104 (treated with 0.1% DMSO) were imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RV at MOI 10 (treated with 0.1% DMSO) were imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RV at an MOI 10 (upper right), MOI 5 (upper left), MOI 1 (lower right) or MOI 0.5 (lower right) and imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RV at MOI 10, treated with 0.1% DMSO alone (vehicle control, left), 50 µM 2-APB, or 10 µM KB-R7943 at 1 hpi, and imaged for GCaMP5G at 2.5 min intervals from ~2–14 hpi.

HeLa cells were imaged for GCaMP6s (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.75 min intervals from ~1.5–15 hpi.

HeLa cells were infected with PV at MOI 10 and then imaged for GCaMP6s (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2.75 min intervals from ~1.5–15 hpi.

MA104 cells were infected with RSV at MOI 10 and then imaged for GCaMP5G (left) and RCEPIAer (right) fluorescence at 2 min intervals from ~24–37 hpi.