Abstract

Nuclear lamins play central roles at the intersection between cytoplasmic signalling and nuclear events. Here, we show that at least two N- and C-terminal lamin epitopes are not accessible at the basal side of the nuclear envelope under environmental conditions known to upregulate cell contractility. The conformational epitope on the Ig-domain of A-type lamins is more buried in the basal than apical nuclear envelope of human mesenchymal stem cells undergoing osteogenesis (but not adipogenesis), and in fibroblasts adhering to rigid (but not soft) polyacrylamide hydrogels. This structural polarization of the lamina is promoted by compressive forces, emerges during cell spreading, and requires lamin A/C multimerization, intact nucleoskeleton-cytoskeleton linkages (LINC), and apical-actin stress-fibre assembly. Notably, the identified Igepitope overlaps with emerin, DNA and histone binding sites, and comprises various laminopathy mutation sites. Our findings should help deciphering how the physical properties of cellular microenvironments regulate nuclear events.

Cells exploit traction forces to sense the physical characteristics of their microenvironments, which co-regulate cell growth, migration and differentiation1-4. Forces can be transmitted to the nucleus by various modes as the cytoskeleton physically couples the cell periphery to the nuclear envelope (NE)5. Cytoskeletal tension generated by motor protein activity along cytoskeletal filaments is transduced across the NE via LINC-complexes that physically connect the cytoskeleton with the nuclear lamina6-8. The nuclear lamina is composed of a 10-60 nm thick protein layer beneath the inner nuclear membrane9-11 and its major constituents are A- and B-type lamins. A-type lamins (lamin A, AΔ10, C) are splice variants of a single gene, LMNA, while B-type lamins are encoded from two different genes LMNB1 (lamin B1) and LMNB2 (lamin B2, B3)12. Lamins are involved in the regulation of gene expression and control the mechanical stability of the nucleus13-15. Cell nuclei with abundant lamin-A are stiffer than nuclei lacking lamin A and the lamin A-to-B stoichiometry increases with increased stiffness of tissues1. Lamins display various hierarchical levels of structural organization. In vitro, lamins were shown to first dimerize in parallel fashion and then polymerize by overlapping the tail region of one dimer with the head of the adjacent one (Fig. 1d). These polymers further organize into protofilaments and finally assemble into 10 nm thick lamin filaments12, 16-19.

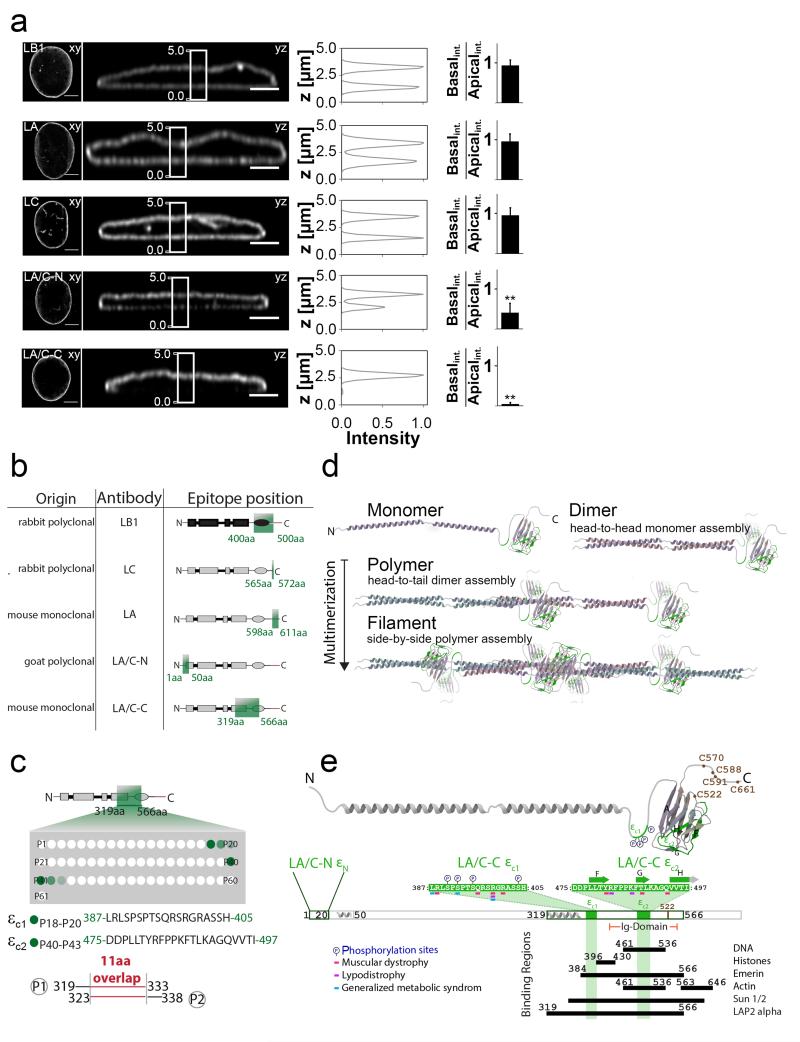

Figure 1. Some, but not all, lamin A/C antibody stains show a basal-to-apical polarization of the nuclear envelope (NE).

a, Antibody stains of various lamins within the nuclear envelope of 3T3 fibroblasts with xy- and yz-confocal sections of corresponding lamin stains (left) together with corresponding intensity profiles along z-axis from region previously defined in yz-section (left, white rectangles). The average peak-to-peak basal-to-apical intensity ratios of the respective immunostains show that L/A-C and L/A-N antibodies label the apical side of the nuclear lamina more intensively (right). **P<0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 22 – 36 cells from 2-3 replicates (see also Fig. S1). Scale bars 5 μm in xy and 3 μm in yz. b, Schematic representation of lamin’s structural domains and of the respective epitopes of lamin targeting antibodies (type-B lamins, black; type-A lamins, grey, epitopes, green) as provided by the suppliers (see Materials and Methods). c, Epitope mapping of the LA/C-C antibody by a PepSpot™ assay shows that the antibody recognized two separate peptide sequences of lamin A/C, at positions P18-20 and P40-43 thus suggesting that LA/C-C antibody recognizes a conformational epitope. The detection intensity is given by shades of green (additional information in Materials and Methods section and Fig. S2). d, Schematic representation of different stages of lamin A/C organization, from monomers to higher order multimers, modified from50 and by using the structures from16, 18, 19. e, Binding sites on lamin A/C and point mutations known to cause diseases, whereby the Lamin A/C structure (grey) shows the highlighted LA/C-N (εN, green) and LA/C-C epitope sequences (εc1 and εc2, green), phosphorylation sites (P) and cysteine residues (brown). Amino acid sequences of LA/C-C epitope with mappings of point mutations associated with laminopathies and of binding regions of lamin A/C’s binding partners (black bars).

Despite the recognition that cell contractility and actin cytoskeletal organization influence nuclear shape20, 21 and that lamins play a central role connecting cytoplasmic signaling with nuclear events and thus cell phenotype1, 14, rather little is known about how external physical stimuli alter the structural organization of the nuclear lamina15, 21, 22.

To address this, we exposed fibroblasts to various engineered microenvironmental niches with defined geometries and material properties to manipulate the physical forces that act on the nucleus in living cells and found that the nuclear lamina is structurally polarized for cells adhering to flat rigid surfaces. We identified two antibodies that selectively recognize lamin A/C epitopes in the apical, but not in the basal NE in 3T3-fibroblasts 120 min after seeding on fibronectin (Fn)-coated glass (Fig. 1a). One epitope locates at the N-terminus (LA/C-N), the other one right after the coiled coil region of lamin A/C (LA/C-C) (Fig. 1b). In contrast, different antibodies against lamin A, lamin C and lamin B1 (LA, LC and LB1) stained basal and apical NE equally well (Fig. 1a). To overcome absolute intensity variations between samples, relative intensities were quantified as the ratios between basal and apical NE from yz-confocal cross sections (Fig. 1a). While the basal-to-apical ratio was close to 1 for LA, LC and LB1 antibodies, it decreased to 0.41 ± 0.23 for LA/C-N and even further to 0.05 ± 0.04 for LA/C-C (Fig. 1a). Control experiments excluded potential fixation artifacts (result not shown). In order to compare variations of different lamin antibody distributions, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between intensity patterns of different antibody pairs. All different lamin antibody labeling pairs showed strong positive correlations except those involving LA/C-C (Fig. S1). Even though some antibodies suggest a complete spatial overlap of A- and B-type lamins within the entire nuclear lamina, certain A-type lamin epitopes targeted by specific antibodies may not be equally accessible throughout the intricate lamina network (Fig. S1), a possibility that was not considered before21, 22.

LA/C-C antibody recognizes a conformational epitope

The moderately inaccessible epitope of the goat-polyclonal LA/C-N antibody (εN) resides in the N-terminus of lamin A/C (residues 1-50, supplier’s information). We more accurately mapped the partially exposed C-terminal epitope of the mouse-monoclonal LA/C-C antibody, localized between the residues 319-566 (supplier’s information), using a specific PepSpot™ epitope-mapping assay. This mapping revealed that the LA/C-C epitope is composed of two separate C-terminal tail amino acid sequences that come into close spatial proximity in the native lamin A/C structure (Figs. 1c, e, S2). The first part of the LA/C-C epitope is located on an unstructured linker region connecting coiled-coil domains and Ig-domain (εc1, residues 387-405), while the second is located on the proximal side of the Ig-domain comprising its β-strands F-to-H (εc2, residues 475-497) (Fig. 1e) and overlaps with a major surface epitope of lamin A/C, where several monoclonal antibodies23 and many lamin A/C interaction partners were shown to bind. The εc1 overlaps with a region required for lamin multimerization, as truncated mini-lamin dimers containing the coil 2 segment and the highly conserved lamin A residues 345-425 can form head-to-tail polymers19. Furthermore, N-terminal residues 11-30 have been indicated to be critical for head-to-tail polymerization24.

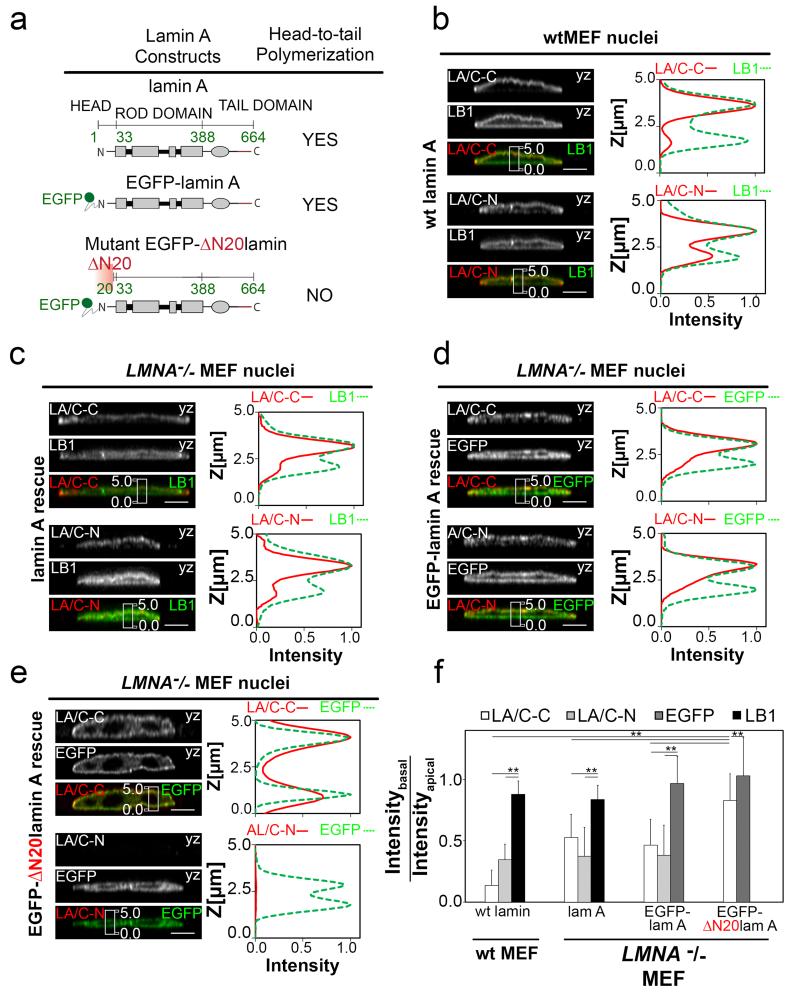

Lamin A/C multimerization reduces LA/C-C accessibility at basal NE

Deletion of the first 20 amino acids from the N-terminus blocks the linear head-to-tail polymerization of lamin A24, while it does not alter lamin dimerization19, nor the C-terminus functionality. To test if lamin multimerization affects exposure of these epitopes, we rescued lamin A null (LMNA -/-) MEFs using either full-length lamin A (EGFP-lamin A) or the referred N-terminal deletion mutant (EGFP-ΔN20lamin A) (Fig. 2c-e). The basal-to-apical LA/C-C ratio increased from 0.14 ± 0.12 for wtMEFs (Fig. 2b), to 0.50 ± 0.30 for lamin A, to 0.46 ± 0.21 for EGFP-lamin A and to 0.83 ± 0.22 for EGFP-ΔN20lamin A expressing MEFs (Fig. 2f). This suggests that reduction of lamin A/C multimerization increases the LA/C-C epitope accessibility. Importantly, the ratio of the basal-to-apical LA/C-N antibody immunostain was similar for wtMEFs (0.35 ± 0.13) and full length lamin A (0.38 ± 0.23) or EGFP-lamin A (0.37 ± 0.24) (Fig. 2b-f) rescues. However, the LA/C-N antibody did not immunolabel EGFP-ΔN20lamin A, confirming that its epitope resides within the first 20 residues of lamin A/C (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2. Multimerization-deficient lamin A mutant (ΔN20-terminal deletion) strongly reduces the basal-to-apical polarization of the LA/C-C stain.

a, Several lamin A-constructs together with indications from the literature whether or not they can polymerize. b, yz-Confocal cross section of wt-MEFs nuclei and respective z-profile showing the basal-to-apical polarized immunostaining of the LA/C-C or LA/C-N antibodies (red) in comparison to non-polarized LB1 antibody immunostain (green). Scale bars 5 μm. c-e, yz-confocal sections and respective z-profiles of the different LMNA null MEF rescues (EGFP signal, green) together with nuclear lamina immunostaining with LA/C-C and LA/C-N antibodies (red) or LB1 antibody (green), whereby the LMNA null MEF cells were transfected with either lamin A (c), or EGFP-lamin A (d), or with an EGFP-N-terminal lamin A truncation (ΔN20-lamin A) which inhibits lamin A polymerization (e). The MEFs were allowed to adhere to Fn-coated glass for 120 min prior to the immunostaining. Scale bars 5 μm. f, Average basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios quantified from the images shown in b-e. **P<0.01, (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 17 – 72 cells from 2-4 replicates.

In search for underpinning mechanisms that render these epitopes inaccessible at the basal NE, we then tested several hypotheses. Since lamins physically connect the NE spanning LINC-complexes7 with the chromatin and/or nuclear DNA, we first tested if LINC-complex proteins bury the LA/C-C epitope. We immunolabeled nesprin-2, nesprin-3 and SUN-2 2h after seeding 3T3-fibroblasts, and found that all of them distributed symmetrically between the apical and basal NE (Fig. S3b). Second, the same was true for emerin and HP125, which physically connect the nuclear lamina with chromatin and showed no basal-to-apical polarization (Fig. S3a,b). Third, to test whether direct DNA binding to lamin A/C regulates basal LA/C-C epitope access, we studied the lamin A mutant R482Q. This point mutation within the εc2 sequence (Fig. 1e) is known to cause lipodystrophy23 and it was previously shown to drastically reduce the affinity of lamin A/C to DNA26.We found that the R482Q mutation did not reduce the LA/C-C basal-to-apical polarization (Fig. S3c). The same was true for other mutants, including K486N (within εc1, Fig. 1e) which inhibits SUMOylation and also causes lipodystrophy27 and P-null (S390A, S392A, S395A and S404A), which inhibits phosphorylation in regions within the LA/C-C epitope. Finally, we tested by steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations how direct tensile forces acting on the Ig-domain of lamin A/C might structurally perturb the LA/C-C epitope (Fig. S4). While tension spatially separated εc1 from εc2, as the A-strand is separated from the remaining Ig-domain, thus partially splitting this epitope, such a mechanism cannot directly explain the simultaneous loss of accessibility of the C- and N-terminal lamin A/C epitopes at the basal NE, unless the resulting stretched Ig-intermediate and concomitant separation of εc1 could promote lamin A multimerization. Taken together, these findings suggest that lamin A/C multimerization and LA/C-C epitope inaccessibility at the basal NE are tightly correlated processes. This might also explain why another C-terminal lamin A antibody epitope has been reported to be accessible only when lamin A depolymerizes during mitosis28.

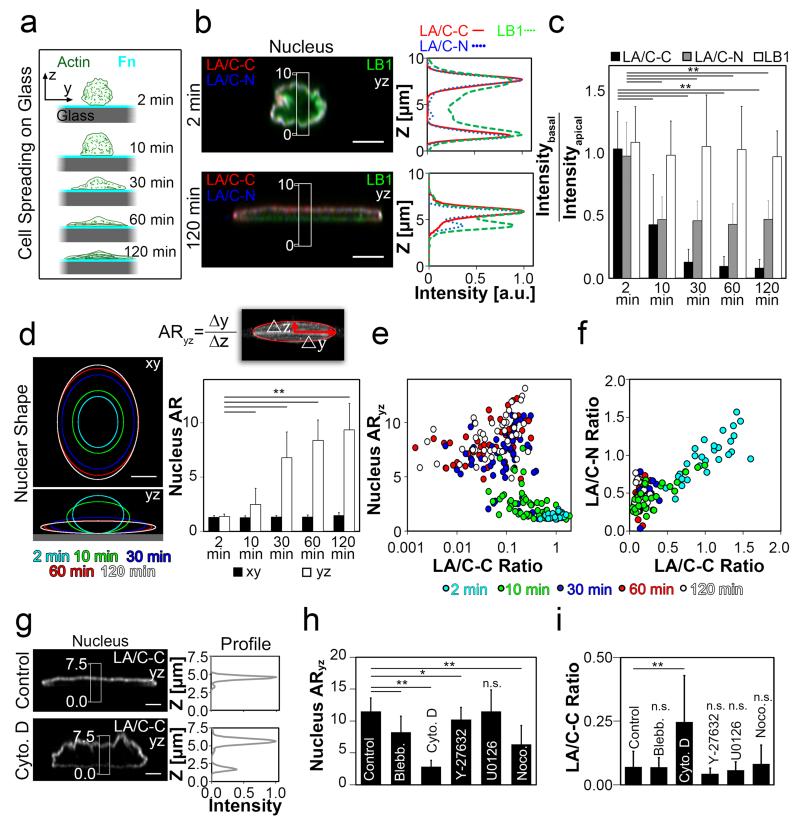

LA/C-C staining polarizes progressively as cells spread

To explore the possibility that cytoskeletal tension regulates the asymmetric epitope exposure, we asked whether nuclear shape changes that accompany cell spreading might affect the differential basal-to-apical LA/C-C and LA/C-N epitope exposures. 3T3-fibroblasts were allowed to spread on Fn-coated glass surfaces (Fig. 3a), whereby the basal-to-apical intensity ratios gradually decreased with time more than ten-fold for LA/C-C and two-fold for LA/C-N (Fig. 3b,c). During cell spreading, absolute intensity values of LA/C-C stayed mostly constant in the apical NE, confirming that the reduced basal-to-apical ratio indicates epitope masking in the basal NE (Fig. S5a). In contrast, the LB1 stained both sides of the NE equally well (Fig. 3b,c). During cell spreading, and as the cytoskeleton spanning the nucleus got assembled, the spherical nucleus gradually flattened (ARyz, Fig. 3d). The nuclear flattening occurred within the first 30 min of spreading (Fig. 3d), and was accompanied by nuclear length and width increases of +84% and +81%, respectively, while lowering the height by −58%, (Fig. S5b). The nuclear flattening correlated with lower LA/C-C ratios (Spearmans rank correlation coefficient, rs = −0.54, p < 0.001, Fig. 3e). The change in LA/C-C ratio was accompanied with similar, albeit smaller reduction in the LA/C-N ratio (rs = 0.67, p < 0.001, Fig. 3f). Finally, only Cytochalasin D treatment of well-spread fibroblasts significantly increased LA/C-C ratio from 0.07±0.06 (control) to 0.25±0.19, which was accompanied by induced nuclear rounding (Fig. 3g-i). We thus conclude that the assembly of the contractile actomyosin cytoskeleton contributes to rendering the LA/C-C epitope inaccessible at the basal NE.

Figure 3. Cell spreading coincides with the build-up of the basal-to-apical polarization of the LA/C-C and LA/C-N stains.

a, Nuclear changes as function of cell spreading time as sketched schematically using 3T3 cells (actin, green) spreading on Fn-coated (cyan) glass (grey). b, yz-Confocal cross sections of representative immunostained nuclei together with the respective intensity profiles along z-axis from the boxed-in regions (white rectangle), either at 2 min or 120 min after cell seeding (LB1 green; LA/C-C, red, LA/C-N. blue), reveal the build-up of a polarized intensity profile of LA/C C and LA/C-N immunostains. Scale bars 5 μm. c, Average basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios of LA/C-C, LA/C-N and LB1 immunostained nuclei for different times after cell seeding. **p<0.001. Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 30 – 59 cells from 2-4 replicates. Corresponding absolute basal and apical intensity changes are given in Fig. S5a. d, Elliptical fits of nuclear shapes at different times after cell seeding (color coded), together with the quantified aspect ratios in xy (ARxy) and yz (ARyz) show progressive nuclear flattening. The ellipses were fitted to the nuclear x-axis maximum intensity projections. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n.s.=not significant (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 21 – 58 cells from 2-4 replicates (see also Fig. S5b). e-f, Scatter-plot of nuclear aspect ratios ARyz as function of the basal-to-apical LA/C-C ratios for different time points (color coded) showing a correlation between LA/C-C ratios and nuclear ARyz, as well as between the epitope exposures of the two lamin A/C epitopes (LA/C-N and LA/C-C) that get buried at the basal NE. g, yz-Confocal cross sections of the immunostained nuclei of Cytochalasin D treated cells and their controls together with respective intensity profiles along the z-axis from the boxed-in region (white rectangle) after 60 min h incubation with control (carrier only, DMSO) or with Cytochalasin D (5μg/ml). Cells were seeded on Fn-coated glass 20 h prior to drug treatments. Scale bars 3 μm. h, Average nuclear ARyz 60 min after various drug treatments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n.s.=not significant (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 19 – 20 cells from 2 replicates. i, Average basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios of LA/C-C stained nuclei in control and after various drug treatments (detailed conditions described in Materials and Methods), showing that only Cytochalasin D treatment significantly reduced the polarized accessibility of the LA/C-C epitope in comparison to the other drugs and the control.

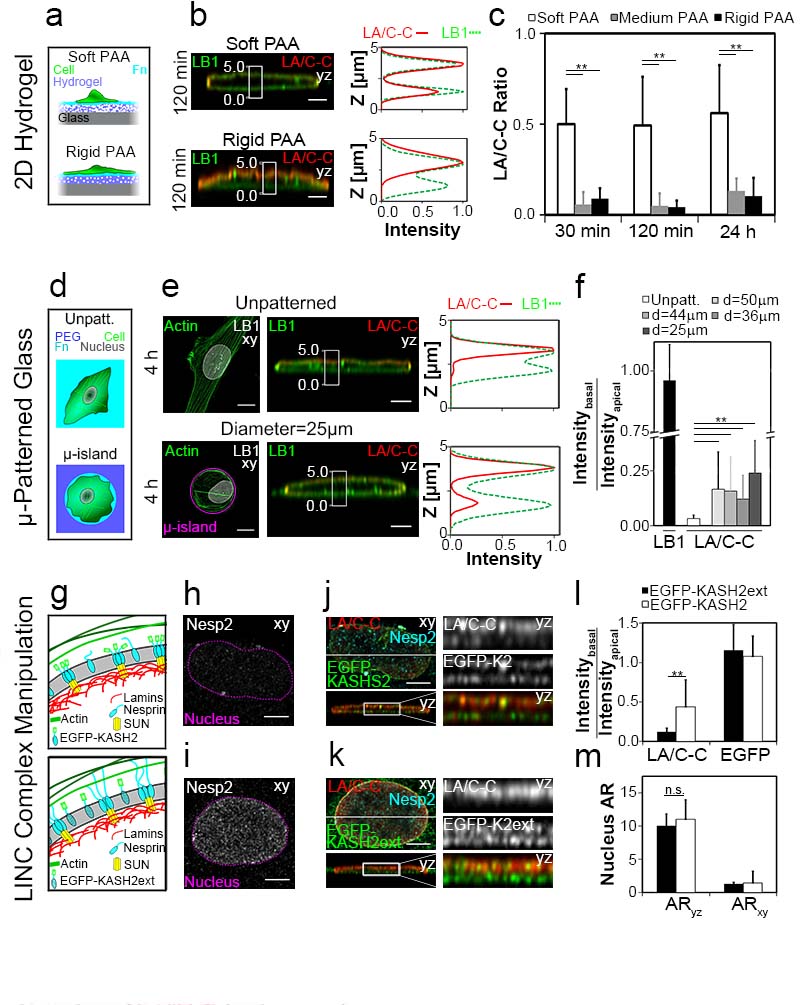

Engineered microenvironments regulate LA/C-C epitope accessibility

Since the physical properties of cellular microenvironments are well known to tune cellular functions, like promoting the faster formation of actin stress fibers on rigid than on soft polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAA)-substrates3, 4, 29-32, we asked how PAA-substrates with defined rigidities affect the structural polarization of the NE (Fig. 4a). As reported previously, cells on Fn-coated rigid (33 kPa) PAA spread to larger areas than on soft PAA (0.48 kPa), and their nuclei were substantially more flattened (24 h, ARyz = 7.4 ± 2.7 and 3.8 ± 0.9, respectively (p<0.001), Fig. S6). The asymmetric LA/C-C epitope exposure increased with the rigidity of Fn-coated PAA substrates, whereby a large fraction of the LA/C-C epitopes was already rendered inaccessible 30 min after cell seeding. In contrast, the epitopes remained mostly accessible over 24 h on soft PAA (Fig. 4b,c) despite the gradual increase in cell spreading area (Fig. S6a). These results indicate that the inaccessibility of LA/C-C epitope at the basal NE is regulated by the tensile state of the cytoskeleton and increases with the PAA-substrate rigidity.

Figure 4. Polarization of the LA/C-C stain can be altered by tuning engineered 2D cell environments and requires physically intact LINC complexes.

a, Schematic representation of 3T3 fibroblasts (cell, green) spreading on Fn-coated soft and rigid polyacrylamide (PAA) hydrogels (blue). b, Nuclear yz-confocal cross sections and respective intensity profiles along the z-axis from the boxed-in nuclear region (white rectangle) for 3T3 fibroblasts seeded on soft and rigid Fn-PAA (LB1, green; LA/C-C, red). Scale bars 3 μm. c, Average basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios of LA/C-C immunostains as function of time after cell seeding on Fn-PAA with specified rigidities (0.48, 10 and 33 kPa) show that the NE polarization is strongly reduced and remains unchanged with time for cells on soft PAA gels **P<0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 17 – 21 cells from 2-4 replicates (see also Fig. S6 and S7b-c). d, Schematic representation of 3T3 fibroblasts (cell, green; nucleus, grey) spread on unpatterned Fn-coated (cyan) glass and on adhesive circular Fn-coated μ-islands surrounded by nonadhesive PEG 4 h after seeding. e, Confocal z-maximum intensity projection of cells spreading for 4 h on unpatterned (top) and circular μ-islands (bottom; actin, green; pattern outline, magenta; LB1, grey) and corresponding nuclei yz-confocal cross sections (LB1, green; LA/C-C, red) together with respective intensity profiles along z-axis from the boxed-in region (white rectangle). Scale bars 10 μm for cell in xy and 3 μm for nuclei in yz. f, Average LB1 and LA/C-C basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios from nuclei of cells adhering to unpatterned glass and to μ-islands of different diameters. **P<0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 12 – 21 cells from 2 replicates (see also Fig. S5c and S7d). g, Schematic representation of disrupted LINC connections (top) between actin (green lines), SUN proteins (yellow) and lamins (red) in the NE (grey) of a cell expressing EGFP-KASH2 (cyan, green) together with similar representation of functional LINC complexes (bottom) in the NE in EGFP-KASH2ext (green, cyan with black cross) expressing cell. h, Nesprin-2 distribution in cells expressing EGFP-KASH2. NE is highlighted with a dashed line (magenta). i, Nesprin-2 distribution in cell expressing EGFP KASH2ext, nucleus is highlighted with a dashed line (magenta). Scale bars 5 μm. j, Confocal z-maximum intensity projection and corresponding yz-confocal cross section of the nucleus of EGFP-KASH2 (green) transfected MEF cell seeded for 120 min on Fn-coated glass (nesprin 2, cyan; EGFP-KASH2, green, LA/C-C, red). Blow-up from yz-section boxed-in region (white rectangle) k, Similar representation as in j, about EGFP-KASH2ext expressing cell. Scale bars 5 μm. l, Average LA/C-C and EGFP basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios from MEF cells expressing the different KASH constructs. m, Average nuclear aspect ratios in MEF cells expressing the different KASH constructs **P<0.01, n.s. = not significant (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 18 – 36 cells from 2 replicates.

As an alternative to tune the cytoskeletal organization and cell phenotype, we confined fibroblasts on microfabricated adhesive μ-islands3, 31-35 (Fig. 4d). Compared to flat surfaces, the nucleus was more rounded as the diameter of circular μ-islands decreased (from 50 to 25 μm) (Fig. S5c) and LA/C-C basal-to-apical ratio increased significantly (Fig. 4e,f). The structural polarization of the nuclear lamina during fibroblast spreading coincided with the formation of an actin cap20. For cells cultured on Fn-coated glass and on PAA, f-actin was first assembled at the apical side of the nucleus, while 120 min after seeding, equal amounts of actin fibers were found on both sides of the NE (Fig. S7a-c). Alternatively, when cell spreading was confined by Fn-coated circular μ-islands, the amount of apical actin fibrils was substantially reduced compared to unpatterned substrates (Fig. S7d), as expected36. Altogether, the inability of cells to build up a highly tensile cytoskeleton on circular islands kept the LA/C-C epitope more accessible at the basal NE, thereby increasing the basal-to-apical LA/C-C ratio.

Intact LINC-complexes are essential for structural NE polarization

Intact LINC-complexes are essential for the transmission of forces between the cyto- and nucleoskeleton networks6, 7, 15, 37. Here, we disturbed LINC-mediated connections by overexpressing the well-characterized EGFP-KASH2 construct, which has been shown to displace endogenous Nesprins from NE to the ER (Fig. 4g)7, 20, 38. In agreement with previous reports, Nesprin-2 did not preferentially localize to the NE in EGFP-KASH2 cells as compared to non-effective EGFP-KASH2ext cells (Fig. 4h,i)7, 20, 38. Importantly, in EGFP-KASH2 expressing cells, the basal-to-apical LA/C-C epitope exposure increased significantly, from 0.12 ± 0.05 to 0.48 ± 0.39 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4j-l), even though the nuclear shape did not change (Fig. 4m). This experiment shows that intact LINC-complexes are essential to drive the polarized accessibility of the LA/C-C epitope.

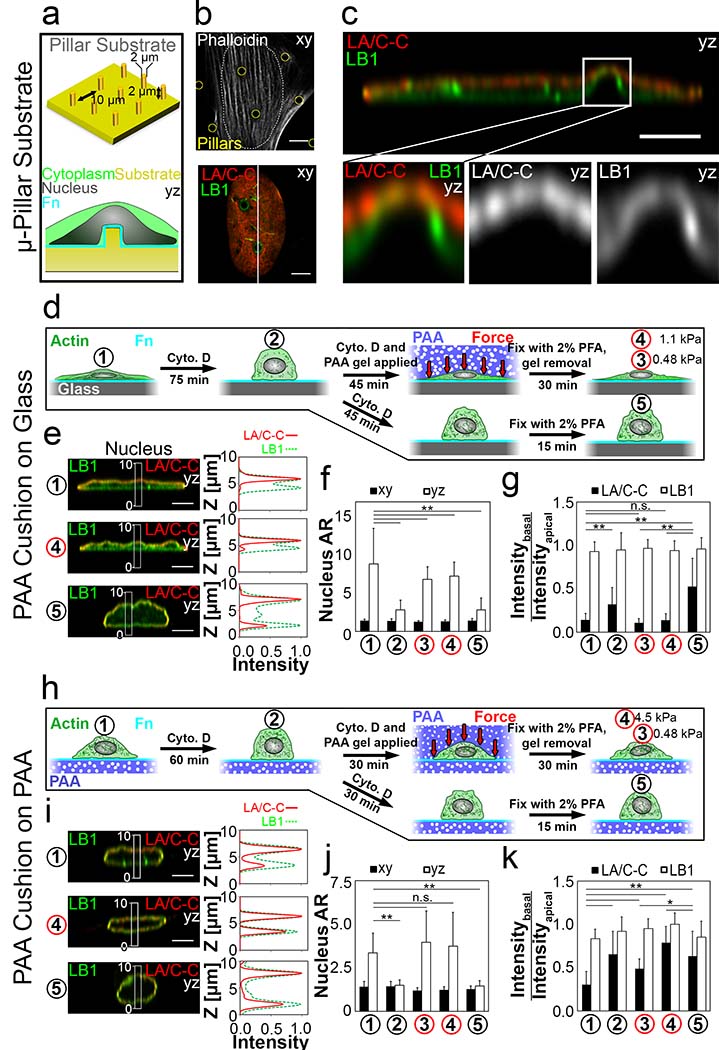

Structural NE polarization tuned by tensile vs compressive forces

Since cell spreading (Fig. 3a-c), confinement to circular islands (Fig. 4d-f) and PAA-substrate rigidity (Fig. 4a-c) all perturbed actin cytoskeleton integrity (Fig. S7), and affected simultaneously intracellular tension and nuclear shape (Figs. 3d and S5b,c, S6b), it became difficult to distinguish between the effects of tensile versus compressive forces acting on the NE, and the role of nuclear flattening in this process. We next designed two experiments to stretch the nuclear lamina. First, we allowed cells to adhere and bend the nucleus around the top of a rigid micropost (Fig. 5a). Even though the stretching of the NE was accompanied by a strong NE curvature, no further change of the basal LA/C-C epitope accessibility was observed (Fig. 5b,c). Thus, the LA/C-C ratio decreases with higher tensile state of the cytoskeleton, but is not further enhanced by the post-imposed NE deformation. Secondly, to mimic the compressive pressure exerted on the nucleus by the actin cap, we depolymerized the actin cytoskeleton by treating well-spread cells on Fn-coated glass with Cytochalasin D, and then applied pressure on the nucleus by compressing it from the top using a soft (0.48 kPa or 1.1 kPa) PAA hydrogel-cushion (Figs. 5d, S8). The LA/C-C basal-to-apical ratio increased from 0.14 ± 0.07 in controls, to 0.32 ± 0.20 in Cytochalasin D treated cells and was reduced back to 0.11 ± 0.05 or 0.14 ± 0.08 if compressed by soft PAA-cushions, 0.48 versus 1.1kPa, respectively, in the continued presence of Cytochalasin D (Fig. 5g). In contrast, the ratio reached 0.53 ± 0.33 if no PAA-cushion was applied during this time-period. These results show that compressive forces imposed by the cushion on the apical side cause the nucleus to flatten (Fig. 5e, f), and most significantly, these externally applied forces can restore the polarized accessibility of the LA/C-C epitope (Fig. 5e,g). We repeated the experiment by substituting the underlying Fn-coated glass substrate with a softer PAA-substrate (0.48 kPa) (Fig. 5h). Here, the polarization of the LA/C-C immunostains was less pronounced than before (Fig. 5e,i) and increased only from 0.31 ± 0.15 to 0.65 ± 0.20 upon Cytochalasin D treatment (Fig. 5k). Although the LA/C-C ratio was reduced to 0.49 ± 0.05 upon compression by a 0.48 kPa PAA-cushion, the initial polarization was not fully restored. Surprisingly, when applying a rigid PAA-cushion (4.5 kPa) to cells adhering to a soft substrate, the LA/C-C re-polarization was inhibited and LA/C-C ratio was even increased to 0.79 ± 0.05 (Fig. 5h-k). In this latter case, polarization of the LA/C-C immunostains was reduced even though the nuclei were significantly flattened (Fig. 5j).

Figure 5. Differential LA/C-C epitope accessibility is not altered when the cell nucleus is bend over a micropost, but can be re-established by cell compression using a nonadhesive PAA cushion.

a, Schematic representation of a nucleus (gray) bending over two Fn-coated (cyan) μ-posts (yellow) 4 h after cell seeding. b, xy-Confocal cross section of a cell sitting on top of a μ-post showing actin (actin, gray; posts, yellow nucleus is highlighted with a dashed line) or nuclear LB1 (green) and LA/C-C (red) immunostain intensities. Scale bars 5 μm. c, yz-Confocal cross section of the nuclear lamina with respective lamin immunostains and blow-up of boxed-in yz-section (white rectangle) with merged and separated LA/C-C (red) and LB1 (green) channels. Scale bar 5 μm. d, Schematic representation of the PAA-gel cushion experiments, where cells have spread on Fn-coated glass. Cellular actin (green) is first depolymerized using Cytochalasin D, which leads into the rounding of the nucleus (gray). Next pressure is applied to the cells (see Fig. S8) using a PAA-hydrogel cushion of 0.48 or 1.1 kPa (blue) in the continuous presence of Cytochalasin D, alternatively the drug treatment is continued without the cushion compression. Finally, the cells are fixed and the cushions are removed. e, yz-Confocal cross section of nuclei, LB1 (green) and LA/C-C (red) immunostains from the different phases of the experiment (numbered 1-5) together with respective intensity profiles along z-axis from the boxed-in nuclear region (white rectangle). Scale bars 5 μm. f, Average nuclear aspect ratios at different stages of the experiment g, Average basal-to-apical intensity ratios of LB1 and LA/C-C from the same experimental points. **P<0.01, n.s.=not significant (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 26 – 72 cells from 2 replicates. h, Schematic representation of the similar PAA-gel cushion experiments as in d–e, but now for cells adhering to Fn-coated PAA (0.48 kPa). i, yz-Confocal cross section of nuclei LB1 (green) and LA/C-C (red) immunostains from different steps (numbered 1-5) of the experiment together with intensity profiles along z-axis from the boxed-in nuclear region (white rectangle). Scale bars 5 μm. j, Average nuclear aspect ratios at different steps of the experiment k, Average basal-to-apical intensity ratio of LB1 and LA/C-C from the same experimental stages. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n.s. = not significant (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 22 – 25 cells from 2 replicates (Additional information in Supplementary Materials and Methods and Fig. S8).

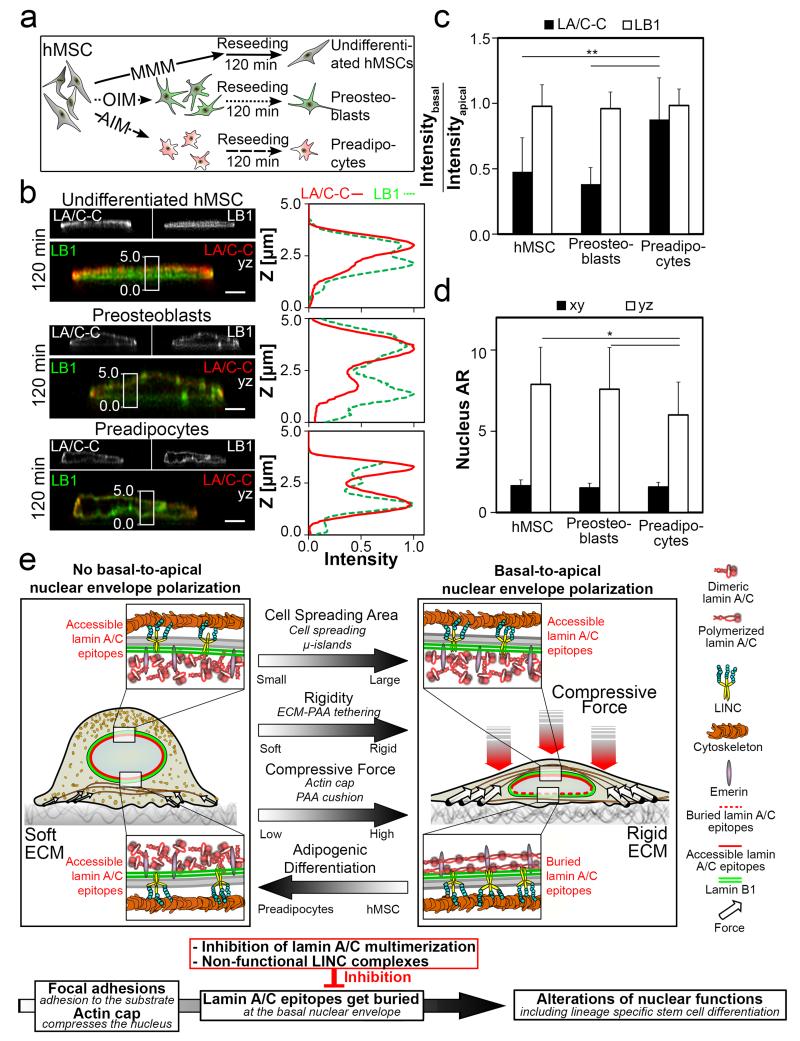

NE structural polarization is abolished in pre-adipocytes

Finally, since lamin A expression levels increase during embryonic stem cell differentiation39 and higher lamin A expression correlates with osteogenic but not adipogenic hMSC differentiation1, we asked how the polarized LA/C-C immunostaining within the NE is affected during this process. After exposing undifferentiated hMSCs to adipogenic or osteogenic conditioning media (10 days), hMSC were reseeded on Fn-coated culture chamber and allowed to spread (120 min, Fig. 6a). While LB1 stained equally both sides of the nuclear lamina and remained unchanged (Fig. 6b,c), the LA/C-C ratio increased considerably for pre-adipocyte differentiated hMSC in comparison to preosteoblasts or undifferentiated hMSC, which correlated with increased nuclear rounding (Fig. 6b-d). This important finding shows that the structural polarization of the nuclear lamina correlates with different hMSC lineage specifications.

Figure 6. Basal-to-apical polarization of the LA/C-C stains is reduced for preadipogenic hMSCs. Overview of factors regulating the differential basal-to-apical LA/C-C epitope accessibility within the NE.

a. Schematic representation of hMSC differentiation experiments. hMSCs (gray) are kept in either mesenchymal stem cell maintaining medium (MMM), in osteogenic induction medium (OIM) or in adipogenic induction medium (AIM) for 2 weeks. Next the cells are reseeded on Fn-coated cell culture chambers and allowed to spread for 120 min. b, yz-Confocal cross sections of the LB1 (green) and LA/C-C (red) immunostains in undifferentiated hMSC, preosteoblasts and preadipocytes, together with corresponding intensity profiles of LB1 and LA/C-C immunostains along the z-axis from the boxed-in nuclear region (white rectangle). Scale bars 3 μm. c, Average basal-to-apical peak intensity ratios of LA/C-C and LB1 immunostains from undifferentiated hMSC, preosteoblasts and preadipocytes d, Average nuclear aspect ratios from the same experimental conditions. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-test, two-tailed). Error bars represent the s.d. of the averages of 27 – 55 cells from 3 replicates. e, Schematic summary of different factors that influence the specific basal-to-apical lamin A/C epitope polarization within the nuclear lamina.

Physiological implications of structural NE polarization

Taken together, we identified two epitopes of lamins A/C that are only rendered inaccessible at the basal NE of those fibroblasts that have compressed nuclei, one is located at the N-terminus and the other involves the C-terminal Ig-domain (Figs. 1, S2). This NE polarization can be significantly tuned by many factors (Fig. 6e), however only few experimental conditions could abolish it completely (Fig. 3c, 5k, 6c). We revealed that the differential basal-to-apical accessibility of these epitopes correlates with changes in lamin A/C multimerization within the basal NE (Fig. 2, 6e). Importantly, this structural polarization is increased for cells in all those engineered microenvironmental niches (Figs. 4, S5, S6) that had previously been shown to upregulate actomyosin contractility and und thus tune diverse downstream cell functions, including differentiation4, 33, 35, 40-42 (Fig. 6e). Our data suggest that actin filaments regulate this process primarily through the compression of the nucleus by formation of the actin cap (Figs. 6e, S7), and that neither microtubules (verified by Nocodazole-treatment, Fig. 3h,i), nor vimentin (verified using vimetin-null cells, Fig. S3a) are critically involved. Depolymerization of the actincytoskeleton by Cytochalasin D treatment and selective LINC-complex disruption led to a significant increase of LA/C-C epitope accessibility at the basal NE (Figs. 3, 4, 6e). However, none of the immunostained LINC-complex components, nuclear lamina or chromatin-associated proteins (Fig. S3b) showed a polarized distribution within the NE. Finally, the structural polarization of the NE can be dynamically regulated by compression of the nucleus (Fig. 5d-k). Upon Cytochalasin D treatment of well-spread fibroblasts, the structural NE polarization was significantly reduced (Fig. 3g-i) and the original levels of polarization could subsequently be restored by compression of the nucleus with a non-adhesive PAA-cushion (Fig. 5h-g). Inversely, for cells adhered on a soft PAA-substrate, similar compression experiment using a more rigid PAA-cushion reduced LA/C-C structural polarization, but not if a soft PAA-cushion was applied (Fig. 5h-k). Since only the substrate and not the cushion is adhesive for integrins, our data suggest that the coupling of the cell-integrin-ECM-substratum adhesions4 to the basal NE are far more important in directing nuclear events than previously thought.

With the NE being at the intersection of cytoplasmic-to-nuclear communication, it is intriguing that the newly identified conformational lamin A/C epitope εc1-εc2 overlaps with key regions previously implicated in chromatin binding, and mutation sites responsible for various laminopathies (Fig. 1e) 26, 43-46. Lamin-bound heterochromatin comprises up to 40 % of the mammalian genome and lamin A/C serves as important tether of the peripheral heterochromatin to the NE during differentiation14, 45-47. Rendering epitopes inaccessible at the NE might thus have major physiological implications, possibly by playing a central role in the mechanoregulation of transcription processes. Our data suggest a novel force-dependent switch that mechanically regulates the differential accessibility of lamin A/C epitopes. Differential exposure or destruction of these lamin epitopes in different regions of the nuclear lamina might imprint a basal-to-apical directionality within the nucleus.

Methods

Cell Culture, transfections, drug treatments and antibodies

NIH-3T3 (CRL-1658, ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (#31966-021, Life-technologies) with 10% FBS. hMSC (PT-2501, Lonza) below passage 6 were cultured with the company recommended media (PT-3238). Differentiation induction followed the company protocol (PT-3238B and PT-4120). The transfections were conducted using Amaxa Biosystem Nucleofector II and specific kit (VDP-1004) according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Lonza). For the pharmaceutical inhibitor studies, cells were first allowed to adhere for 20 h on Fn-coated (25 μg/ml, PBS) coverslips, followed by medium replacement with new medium containing the drug of choice and subsequent incubation (1 h), unless specified otherwise. The used drugs and concentrations were: Blebbistatin (10 μM, Sigma), Cytochalasin D (5 μg/ml, Sigma), Y-27632 (10 μM, Sigma), U0126 (10 μM, Cell Signaling) and Nocodazole (10 μM, Sigma). Control cells were incubated with 1:1000 dilution of DMSO in DMEM. The antibodies and their dilutions were LA/C-C (Abcam, ab8984) and LA (Abcam, ab8980) 1:200, LA/C-N (Santa-Cruz Biochemicals, sc-6215) and LB1 (Abcam, ab16048) 1:500, LC (Abcam, ab106682), HP1 (Abcam, ab77256) 1:100, Nesprin 2 (ImmuQuest, IQ565) 1:500, Nesprin 3 (ImmuQuest, IQ566) 1:500 Emerin (Abcam, ab40688) 1:100 and SUN2 (generous gift from Dr. Ulrike Kutay) 1:1000, for secondary antibodies linked with Alexa-488, -555 or -633 (Invitrogen), 1:200 and Phalloidin Alexa-488 or -633 1:200 and 1:50, respectively. PPARγ Antibody (I-18) (Santa Cruz Biochemicals, sc-6285) and Alkaline Phosphatase (L-19) (Santa Cruz Biochemicals, sc-15065), both at 1:50 dilution, were used as pre-adipocyte and pre-osteocyte hMSC differentiation markers, respectively.

Different cell culture substrates

For the PAA gels, the glass coverslips were first plasma cleaned for 30s, followed by incubation with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) 4 min (RT). The coverslips were washed with nanopure water and incubated 30 min with 0.5% glutaraldehyde. These surfaces were washed again and dried in an air stream. The polyacrylamide (PAA) hydrogels with different rigidities were obtained from different mixtures of 40 % acrylamide and 2 % bis-acrylamide (Biorad) in PBS48. After polymerized, the gels were functionalized by 1mM of sulfosuccinimidyl 6-(4azido-nitrophenylamine) in PBS (pH 8.5) under UV, 10 min. The functionalized PAA were coated with Fn (25 μg/ml, PBS) for 1 h, RT. Finally, 3000 cells/cm2 were plated on the gels and fixed for different times after seeding.

Master structures of microposts (2 μm diameter, 12 μm pitch and 2 μm height) in thermoplastic polycarbonate were received from Jaslyn Law Bee Khuan (IMRE, Singapore). Master structures were fluorosilanized for 1 h and replica molded with PDMS (1:10 curing agent to prepolymer (w/w)), which was cured at 70 °C overnight. PDMS stamps were peeled off from the master structure and used for the production of SU-8 (2015, MicroChem, US) microposts on coverslips. SU-8 was spread between PDMS stamp and coverslip, degassed and UV-cured (40 mW/cm2 at 365 nm) before delamination. Finally, 3000 cells/cm2 were plated on the microposts and fixed after 4 h.

Circular adhesive μ-islands were prepared on glass coverslips using combined photolithography and lift-off processes49. S1818 photoresist (Micropost) was spin-coated on cover glasses in a two-step spinning process, followed by soft baking and UV light exposure. The resist pattern was rendered biopassive by 1 h incubation (RT) with 100 μg/ml PLL-g[3.5]-PEG(2) (SuSoS AG) in PBS. The photoresist was removed by chemical lift-off leaving the PLL-g-PEG coated regions on the surface. The non-PEGylated areas were backfilled with Fn (25 μg/ml, PBS) during 1 h (RT). Finally, 5 000 cells/cm2 were plated on the μ-islands substrates and fixed after 4h.

Epitope Mapping

LA/C-C epitope was mapped using custom-made PepSpot-membrane consisting of 61 peptides (residue 319 to 566, Lamin A/C, partially overlapping by 11 aa) (JPT Peptide Technologies GmbH, Berlin, Germany). In order to reduce any unspecific binding, the membrane was first incubated with the isotype control, mouse IgG1 kappa monoclonal (Abcam), 1:500 dilution, followed by HRP secondary (1:3000) incubation and ECL substrate developing. PepSpot-membrane washing and blocking steps followed the manufacture’s recommendations. In a second blotting step, the PepSpot membrane was incubated with the primary antibody of interest LA/C-C 1:1000, and further blotted using AP secondary antibody (1:3000) developed with CDPstar substrate.

Statistical analysis

All experimental conditions were repeated 2-4 times and 12-72 cells were imaged per repeat and condition. The imaged cells were randomly selected from the population. The final results contain all analyzed cells without any definite inclusion criteria, in some cases (6% of total cell number) cells were left out from the analysis due to the difficulties to perform the required measurements (cellular and nuclear deformations etc).

The data were then tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk normality test and since some of the data sets did not meet the normality criteria, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to see if the sample populations differ within the experiment. Finally, pair-wise comparison of the different conditions was conducted using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test to confirm the possible statistical significance between the experimental conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Melanie Burkhardt, Jaslyn Law Bee Khuan (IMRE, Singapore) and Susanna Früh for their valuable help with micropost and adhesive microisland substrates; Dr. Maija Vihinen-Ranta and Dr. Didier Hodzic for EGFP-lamin A and EGFP-KASH2 constructs, respectively; Prof. Roland Foisner, Prof. Ohad Medalia, Prof. Jan Lammerding and Prof. Reinhard Fässler for LMNA null, VIM null, EMD null and WT MEF cells, respectively; Prof. Ulrike Kutay for SUN2 antibody; Dr. Katharina Maniura for the usage of the Amaxa Nucleofector II system. This research was supported by Foundations’ Post Doc Pool, Finland; Academy of Finland, grants 252225 and 267471 (TOI); Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, doctoral grant SFRH / BD / 42019 / 2007 (LA); SystemsX.ch - “PhosphoNetX”, Internal Nr. 2-67124-08 (VV); ERC Advanced Grant European Community, GA233157 (VV); and SNF Swiss National Science Foundation, Grant 310030B_133122 (VV). Computational resources provided by the Swiss National Supercomputing Center (CSCS) and the University of Tampere Imaging Facility are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Swift J, et al. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science. 2013;341:1240104. doi: 10.1126/science.1240104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaalouk DE, Lammerding J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:63–73. doi: 10.1038/nrm2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel V, Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trappmann B, et al. Extracellular-matrix tethering regulates stem-cell fate. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nmat3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sosa BA, Rothballer A, Kutay U, Schwartz TU. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crisp M, et al. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isermann P, Lammerding J. Nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction in health and disease. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:R1113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aebi U, Cohn J, Buhle L, Gerace L. The nuclear lamina is a meshwork of intermediate-type filaments. Nature. 1986;323:560–564. doi: 10.1038/323560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerace L, Huber MD. Nuclear lamina at the crossroads of the cytoplasm and nucleus. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;177:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senda T, Iizuka-Kogo A, Shimomura A. Visualization of the nuclear lamina in mouse anterior pituitary cells and immunocytochemical detection of lamin A/C by quick-freeze freeze-substitution electron microscopy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2005;53:497–507. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6478.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dechat T, Adam SA, Taimen P, Shimi T, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000547. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lammerding J, et al. Lamins A and C but not lamin B1 regulate nuclear mechanics. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:25768–25780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solovei I, et al. LBR and lamin A/C sequentially tether peripheral heterochromatin and inversely regulate differentiation. Cell. 2013;152:584–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilluy C, et al. Isolated nuclei adapt to force and reveal a mechanotransduction pathway in the nucleus. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ncb2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuurman N, Sasse B, Fisher PA. Intermediate filament protein polymerization: molecular analysis of Drosophila nuclear lamin head-to-tail binding. J. Struct. Biol. 1996;117:1–15. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heitlinger E, et al. The role of the head and tail domain in lamin structure and assembly: analysis of bacterially expressed chicken lamin A and truncated B2 lamins. J. Struct. Biol. 1992;108:74–89. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(92)90009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strelkov SV, Schumacher J, Burkhard P, Aebi U, Herrmann H. Crystal structure of the human lamin A coil 2B dimer: implications for the head-to-tail association of nuclear lamins. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:1067–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapinos LE, et al. Characterization of the head-to-tail overlap complexes formed by human lamin A, B1 and B2 “half-minilamin” dimers. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396:719–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khatau SB, et al. A perinuclear actin cap regulates nuclear shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:19017–19022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908686106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DH, Wirtz D. Cytoskeletal tension induces the polarized architecture of the nucleus. Biomaterials. 2015;48:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimi T, et al. The A- and B-type nuclear lamin networks: microdomains involved in chromatin organization and transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3409–3421. doi: 10.1101/gad.1735208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manilal S, Randles KN, Aunac C, Nguyen M, Morris GE. A lamin A/C beta-strand containing the site of lipodystrophy mutations is a major surface epitope for a new panel of monoclonal antibodies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1671:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isobe K, Gohara R, Ueda T, Takasaki Y, Ando S. The last twenty residues in the head domain of mouse lamin A contain important structural elements for formation of head-to-tail polymers in vitro. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:1252–1259. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amendola M, van Steensel B. Mechanisms and dynamics of nuclear lamina-genome interactions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;28:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stierle V, et al. The carboxyl-terminal region common to lamins A and C contains a DNA binding domain. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4819–4828. doi: 10.1021/bi020704g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon DN, Domaradzki T, Hofmann WA, Wilson KL. Lamin A tail modification by SUMO1 is disrupted by familial partial lipodystrophy-causing mutations. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2013;24:342–350. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collard JF, Senecal JL, Raymond Y. Differential accessibility of the tail domain of nuclear lamin A in interphase and mitotic cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;173:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelham RJ, Jr, Wang Y. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:13661–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeung T, et al. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2005;60:24–34. doi: 10.1002/cm.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kihara T, Haghparast SM, Shimizu Y, Yuba S, Miyake J. Physical properties of mesenchymal stem cells are coordinated by the perinuclear actin cap. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;409:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tee SY, Fu J, Chen CS, Janmey PA. Cell shape and substrate rigidity both regulate cell stiffness. Biophys. J. 2011;100:L25–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain N, Iyer KV, Kumar A, Shivashankar GV. Cell geometric constraints induce modular gene-expression patterns via redistribution of HDAC3 regulated by actomyosin contractility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:11349–11354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300801110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thery M, Pepin A, Dressaire E, Chen Y, Bornens M. Cell distribution of stress fibres in response to the geometry of the adhesive environment. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2006;63:341–355. doi: 10.1002/cm.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupont S, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q, Kumar A, Makhija E, Shivashankar GV. The regulation of dynamic mechanical coupling between actin cytoskeleton and nucleus by matrix geometry. Biomaterials. 2014;35:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luxton GW, Gomes ER, Folker ES, Vintinner E, Gundersen GG. Linear arrays of nuclear envelope proteins harness retrograde actin flow for nuclear movement. Science. 2010;329:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1189072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart-Hutchinson PJ, Hale CM, Wirtz D, Hodzic D. Structural requirements for the assembly of LINC complexes and their function in cellular mechanical stiffness. Exp. Cell Res. 2008;314:1892–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Constantinescu D, Gray HL, Sammak PJ, Schatten GP, Csoka AB. Lamin A/C expression is a marker of mouse and human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:177–185. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramdas NM, Shivashankar GV. Cytoskeletal control of nuclear morphology and chromatin organization. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taniura H, Glass C, Gerace L. A chromatin binding site in the tail domain of nuclear lamins that interacts with core histones. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:33–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldberg M, et al. The tail domain of lamin Dm0 binds histones H2A and H2B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:2852–2857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guelen L, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Towbin BD, et al. Step-wise methylation of histone H3K9 positions heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery. Cell. 2012;150:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talwar S, Jain N, Shivashankar GV. The regulation of gene expression during onset of differentiation by nuclear mechanical heterogeneity. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2411–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tse JR, Engler AJ. Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. Curr. Protoc. Cell. Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1016s47. Chapter 10, Unit 10.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Möller J, Emge P, Avalos Vizcarra I, Kollmannsberger P, Vogel V. Bacterial filamentation accelerates colonization of adhesive spots embedded in biopassive surfaces. New Journal of Physics. 2013;15:125016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dittmer TA, Misteli T. The lamin protein family. Genome Biol. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-222. 222-2011-12-5-222. Epub 2011 May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.