Abstract

Background. The community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) epidemic in the United States is attributed to the spread of the USA300 clone. An epidemic of CA-MRSA closely related to USA300 has occurred in northern South America (USA300 Latin-American variant, USA300-LV). Using phylogenomic analysis, we aimed to understand the relationships between these 2 epidemics.

Methods. We sequenced the genomes of 51 MRSA clinical isolates collected between 1999 and 2012 from the United States, Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. Phylogenetic analysis was used to infer the relationships and times since the divergence of the major clades.

Results. Phylogenetic analyses revealed 2 dominant clades that segregated by geographical region, had a putative common ancestor in 1975, and originated in 1989, in North America, and in 1985, in South America. Emergence of these parallel epidemics coincides with the independent acquisition of the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) in North American isolates and a novel copper and mercury resistance (COMER) mobile element in South American isolates.

Conclusions. Our results reveal the existence of 2 parallel USA300 epidemics that shared a recent common ancestor. The simultaneous rapid dissemination of these 2 epidemic clades suggests the presence of shared, potentially convergent adaptations that enhance fitness and ability to spread.

Keywords: USA300, USA300-LV, MRSA, epidemics

Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen causing life-threatening infection in healthcare and community settings. In the past few decades, acquisition of several antibiotic resistance determinants by S. aureus has made the treatment of such infections an important clinical challenge. Most notably, the emergence and dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) throughout the world appears to follow an epidemic pattern, with MRSA clones disseminating in specific geographical areas. Prior to the 1990s most MRSA was associated with hospital settings. Since that time, community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) has become increasingly frequent in the United States [1, 2], an epidemiological change that coincides with an overall increase of skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTIs) and S. aureus–related hospitalizations [3, 4]. In North America, this CA-MRSA epidemic is widely attributed to the spread of a clone designated “USA300” [5].

The earliest report of the USA300 clone is from an outbreak of infections starting in November 1999 in a state prison in Mississippi [6]. Within a 3-year period, additional outbreaks were documented from several other states, including California, Colorado, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Texas, where USA300 appeared in community settings such as correctional facilities, military bases, and day-care centers and in sports teams. USA300 rapidly became more widespread in the community, and, by 2004, it had become the major cause of SSTIs in the United States [1]. USA300 also causes other life-threating diseases, such as community-acquired pneumonia, osteomyelitis, and bloodstream infections [7, 8]. The spread of USA300 has been linked to large increases in hospitalizations for severe SSTI from 2000 to 2009 [4, 9] and replacement of other, possibly less virulent S. aureus clones [10].

First identified in 2005 [11, 12], a USA300 Latin American variant (USA300-LV) has spread through community and hospital settings in Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador, replacing the prevalent but unrelated hospital-associated MRSA clone designated “Chilean/Cordobes” [12, 13]. USA300-LV appears to cause the same spectrum of disease as USA300 from North America, and it has become the most prevalent CA-MRSA strain in S. aureus infections in northern South America [13]. Isolates belonging to the USA300-LV clone are close relatives of North American USA300, based on standard molecular typing techniques, and they possess some of the key genetic signatures of the USA300 lineage, including a pathogenicity island that encodes the enterotoxin genes sek and seq (SaPI5) and the genes for Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), lukSF-PV [12, 13]. USA300-LV isolates differ from North American USA300 isolates in that they lack a genomic locus referred to as the “arginine catabolic mobile element” (ACME) [14, 15], which is thought to be an important determinant for the success of USA300 [16–18]. Most USA300-LV isolates also harbor a different variant of the methicillin resistance cassette (SCCmec IVc-E) [12, 13, 19, 20].

Because USA300-LV infections first were characterized 6 years after the initial description of USA300 isolates in North America, it has been assumed that South American CA-MRSA strains likely disseminated southward from a North American origin. In this study, we aimed to delineate the specific genetic relationships between USA300 and USA300-LV by using whole-genome sequencing to provide insights into the epidemiology and evolution of the CA-MRSA epidemics in the Americas. We show that the South American epidemic involving CA-MRSA is not an extension of the North American epidemic of USA300, but rather occurred simultaneously, with the 2 lineages sharing a common ancestor prior to their epidemic spread.

METHODS

Bacterial Strains

MRSA isolates from South America were collected from a surveillance study performed in tertiary hospitals in Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela between 2006 and 2007 [13]. We also included the first 2 characterized USA300-LV strains isolated in 2005 [11, 12] and the recently reported vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant MRSA strains recovered from a patient in Brazil, also related to the USA300 lineage [21]. Isolates from the United States were collected in multiple states from 1999 to 2012. Identification of all MRSA isolates, determination of antimicrobial susceptibility profiles, SCCmec typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and amplification of genes encoding PVL were performed as described before [13, 21]. All bacterial details of isolation are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Genome Sequencing

For the Illumina platform, genomic DNA was prepared using either the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) or the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) after lysostaphin treatment. Genomic DNA libraries were prepped using the NexteraXT DNA sample preparation kit and sequenced on a MiSeq desktop sequencer (Illumina) with 250-bp paired-end reads. Genome assembly was done using the paired-end implementation of ABySS [22] and CLCGenomics Workbench, version 8.1 (CLCBio, Aarhus, Denmark). GenBank accession codes are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

For the PacBio platform, genomic DNA was prepared from concentrated overnight cultures treated with lysostaphin. The Genomic DNA tips 500/G and Genomic Buffer Set (Qiagen) was then used for initial preparation of the DNA. Approximately 3.5 µg of DNA was used to construct SMRTBell libraries for the PacBio RS II DNA sequencing system (Pacific Biosciences), using polymerase enzyme–DNA bound complexes with an average insert size of approximately 20 kb. The binding chemistry was done using the PacBio P5-C3 DNA-polymerase binding kit. The DNA-polymerase complex of the sample was prepared using 0.5 nM of the SMRTbell library and 10× excess DNA polymerase. All 20-kb samples were loaded using MagBeads prior to immobilization on SMRTcells. The PacBio RS II DNA sequencing system used 180-minute continuous collection times and C3 sequencing chemistry, allowing collection of subreads of up to approximately 36 000 bp. We used the HGAP2 v2.1 de novo assembly pipeline [23]. GenBank accession numbers are shown in the Supplementary Table 2.

Antibiotic Resistance Genes (Resistome)

The presence of the most frequent genetic resistance determinants present in MRSA was evaluated using the BLASTn tool from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (e value, 0; identity, >98%; alignment coverage, >95%). Protein alignments were performed using ClustalW for GyrA and ParC. Accession numbers of the query genes are provided in the Supplementary Table 3.

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Calling and Phylogenetic Matrix Construction

Comparison of SNPs between isolates was done by means of short-read alignment to the genome of USA300 strain TCH1516 as reference, using the Burrows–Wheeler alignment (bwa) tool (available at: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net). SNP calls were made using samtools (available at: http://samtools.sourceforge.net). SNPs were identified as high quality if they were not listed as heterozygous and had a per base Q score ≥20. For preassembled genomes from public databases, we used whole-genome alignment with reference to the S. aureus TCH1516 genome, using the show-snps utility of NUCmer (available at: http://mummer.sourceforge.net). For Bayesian analysis, only SNPs defined by the samtools approach were used. All regions from the reference genome annotated as mobile genetic elements were excluded (Supplementary Table 4). We also applied a mask that excluded repetitive sequences from the reference genome that were >80% identical over at least 100 nucleotides to other genomic loci, based on pairwise MegaBLAST-based analysis.

Establishment of Gene Orthology and Presence/Absence Matrix

We determined orthologous gene sets from assembled isolate genomes, using a modified version of the OrthologID pipeline [24] that now uses OrthoMCL for gene family clustering [25]. The presence and absence of genes was determined from the resulting concatenated alignment matrix of orthologs. Select genes were confirmed by BLAST (available at: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Phylogenetic and Time of Divergence Analyses

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenies were constructed with the POSIX-threads build of RAxML, version 8.0.19 [26]. We used an ascertainment bias correction and a general time-reversible (GTR) substitution model [27], accounting for among-site rate heterogeneity by using the Γ distribution and 4 rate categories [28] (ASC_GTRGAMMA model) for 100 individual searches with maximum parsimony random-addition starting trees. Node support was evaluated with 1000 nonparametric bootstrap pseudoreplicates [29]. The number of bootstrap pseudoreplicates over which node support is not expected to be significantly altered was evaluated using the frequency-based (300 bootstrap iterations were sufficient) and extended-majority-rule (550 bootstrap iterations were sufficient) bootstrapping criteria [30]. The program SplitsTree4 was used to create a network of bootstrap trees (Figure 1A). The program FigTree (available at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) was used to make Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis shows relationships between whole-genome Staphylococcus aureus isolates. A, Phylogenetic network is based on 1000 maximum likelihood nonparametric bootstrap iterations for 88 Staphylococcus aureus genomes. Only sequence type 8 (ST8) strains are shown (8 genomes used as outgroups have been excluded for clarity). Areas of low support show higher amounts of reticulation. Note that the 2 epidemic lineages in the North American epidemic (NAE) and the South American epidemic (SAE) can be robustly distinguished from each other but exhibit high levels of reticulation internally. Whole genomes of BR-VRSA, COL, FPR3757, Newman, RN4220, TCH1516, USA500, and VC40 are shown for comparative purposes. B, Chronogram was constructed using core genome single-nucleotide polymorphisms from the 48 sequenced strains in a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis that coestimated the phylogenetic relationships among isolates, the times since the divergence of the major clades, and the rate of evolutionary change. We used a relaxed-clock model and a constant-size coalescent tree prior probability. Calendar dates of isolation were used to calibrate the clock. Branches are colored based on parsimony reconstruction of geographical location in North America (blue) or South America (red). Numbers on or near branches are Bayesian posterior probability support values. Ancestral branches with uncertain geographical reconstructions are black. Pie charts show proportional likelihood reconstructed for each of the key branches based on the mkt1 model (see “Methods” section). Early branching (EB) strains are also indicated. Key evolutionary acquisition events (eg, arginine catabolic mobile element [ACME] and copper and mercury resistance [COMER] element acquisition events) are indicated with arrows. The binary matrix shows presence (green; 1) and absence (white; 0) of selected genes associated with each lineage. Abbreviations: abi α, abortive phage infection; arcA, arginine deiminase; copB, putative ATPase copper exporter; lipo, putative lipoprotein; lukSF-PVL, Panton-Valentine leukocidin; mecA, PBP2a; mco, multicopper oxidase; merA, mercuric reductase; sek, enterotoxin K; seq, enterotoxin Q; speG, spermidine N(1)-acetyltransferase.

The time of divergence of genetic lineages was estimated in a Bayesian framework in BEAST, version 1.7.5 [31], by calibrating the tree using the dates of isolation of the strains (Supplementary Figure 1) [32]. Since only SNPs were included in the alignment, we accounted for the lack of constant sites by editing the XML input file according to recommendations made by the main BEAST developer (Andrew Rambaut, University of Edinburgh). Evolutionary rates along the tree were allowed to vary, as accommodated by the uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock [33], and a constant-size coalescent tree process was assumed [34]. Each run of the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) procedure consisted of 300 million steps with a 5000-step thinning. After inspection of the MCMC traces and the effective sample size (ESS) values of each run (ESS > 200), 10% of the first posterior samples were removed as a burn-in, and the posterior estimates from 3 individual runs were combined to form a posterior sample density based on 810 million samples. Departure from a strict molecular clock was confirmed by observing the posterior estimate of the coefficient of rate variation (mean, 1.0587; 95% highest posterior density interval (HPD), 0.7825–1.3718). The chronogram was plotted on the basis of the maximum clade credibility tree. A median rate of 8.7201 × 10 − 7 (95% HPD, 3.6595 × 10 − 7– 1.4463 × 10 − 6) was estimated for this analysis (Supplementary Figure 3). Tree files for Bayesian and ML analysis are included as Supplementary Materials.

Phylogeographic and Gene Presence/Absence Reconstruction

All phylogenetic reconstructions were done using parsimony and likelihood-based techniques in the application Mesquite, version 275 [35]. Likelihood reconstruction was based on the Mk1 (est.) model, a 1-parameter Markov k-state model [36]. Parsimony reconstruction was based on the Fitch optimization procedure [37]. States of presence or absence were assigned “1” or “0” for each taxon. For phylogeography, North America and South America were also coded as binary variables (“0” and “1,” respectively). In all instances, the outgroup taxon character state was treated as missing data.

Whole-Genome Alignment

We constructed whole-genome multiple alignments of PacBio Assemblies, using mummer (available at: http://mummer.sourceforge.net), with each genome, compared with the USA300 reference strain FPR3757, averaging the percentage identity score for all nucmer alignments that overlapped a given coordinate in the reference. Areas of no alignment were assigned a percentage identity score of 0. We then used the alignments to plot these as scores in Circos (available at: http://circos.ca).

Genealogy of the copB Gene

We used the copB gene from USA300 FPR3757 (ABD21730.1) to search for closely related genes in GenBank (wgs and nr databases), using BLAST. Genes with >99% nucleotide identity were included (Supplementary Table 5). Nucleotide sequences were aligned using the Geneious 6.1.4 alignment algorithm with default settings. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using RAxML, version 8.0.19, with the GTR substitution model; among-site rate heterogeneity was determined using the Γ distribution and 4 rate categories; and 100 individual searches were performed with maximum parsimony random-addition starting trees. Node support was evaluated with 500 nonparametric bootstrap pseudoreplicates.

RESULTS

To delineate the relationship between USA300 and USA300-LV, we sequenced the genomes of 51 MRSA isolates recovered from clinical samples between 1999 and 2012 from various locations throughout the United States, Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. We used a collection of the earliest known USA300-LV isolates that were recovered during 2005–2012 (n = 25) and selected USA300 isolates (n = 25) covering a wide geographic and temporal distribution within the United States, including the earliest-known existing USA300 isolate, which was recovered in Mississippi during 1999. We included the first CA-MRSA isolate belonging to the USA300-LV lineage that was identified in Colombia (Bogota) in 2005 [11, 12] and the recently reported vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant strains recovered from a patient in Brazil, also related to the USA300 lineage [38]. Initial comparative genomic analysis suggested that isolates belonging to USA300-LV are very closely related to USA300 isolates. The average number (±SD) of high-quality SNPs comparing South American genome sequences to the core genome of USA300 reference strain TCH1516 was 303 ± 47 (range, 265–385), whereas comparison of USA500 strain 2395 (USA300's putative closest relative) [39] to TCH1516 revealed 533 SNP differences, suggesting that USA300-LV are more closely related to North American USA300 isolates than USA500.

This close relationship was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis of 94 847 SNPs from 88 S. aureus genomes, including 80 clonal complex 8 (CC8) genomes (Figure 1A), and revealed 2 distinct sister clades that segregate by geographical region (Figure 1A). The genomic profiles of isolates from each of these clades match the profiles of the most prevalent epidemic strains in North and South America (for instance, ACME is only found in the North American clade), and antibiotic resistance gene profiles were also similar (Supplementary Figure 1). We designated these clades “NAE” and “SAE,” for North and South American epidemics, respectively. The range of isolation dates in the NAE clade (from 2001 to 2012) reflects almost the entire time frame of the epidemic. Therefore, it appears that the SAE and NAE clades diverged before the emergence of the USA300 epidemic in North America and, most importantly, that the SAE clade does not represent dissemination of the US epidemic.

To further explore the timing of these events, we used a Bayesian tip-calibration approach [33] to coestimate the evolutionary rate of change and the times since the divergence of the major clades (Figure 1B). We estimated that the parallel epidemics in North and South America shared a common ancestor in approximately 1975 (95% HPD, 1932–1993) and individually originated in 1989 (95% HPD, 1971–1999) and 1985 (95% HPD, 1962–1997) for NAE and SAE, respectively. Importantly, the credibility intervals on these dates place the origins of the 2 clades securely before the first reports of USA300 in North America (Supplementary Figure 2) and suggest that members of the USA300 clade have been present in the Western Hemisphere since the 1930s (median, 1933; 95% HPD, 1846–1977).

Interestingly, the early branches of the USA300 tree that diverge prior to NAE and SAE represent a mixed collection of isolates from both regions, suggesting that the USA300 lineage was repeatedly transmitted throughout the Americas long before the current epidemics. Because of this branching pattern, phylogeographic reconstructions using both parsimony and likelihood approaches were unable to definitively assign a North or South American origin to these early branch points (Figure 1B). Of interest, no early branching isolates or members of the SAE clade harbor the ACME locus (Figure 1). This absence strongly suggests that ACME was first acquired by an ancestor within the NAE clade. The estimated date, 1994 (95% HPD, 1981–2000), at the node that represents the first ACME-containing ancestor (Figure 1B) is consistent with previous estimates of the acquisition of this element by horizontal gene transfer [18, 40] and immediately precedes the North American epidemic.

To more fully characterize the genomic repertoires of the USA300-LV strains, we completed closed-circular genome sequences of 5 strains (V2200, M121, HUV05, CA15, and CA12) chosen on the basis of their phylogenetic position to capture the broadest phylogenetic diversity possible. These genomes are extremely similar to the TCH1516 reference both in sequence and gene order (Figure 2). The most divergent isolate within this sample is V2200, which harbor 431 SNPs, compared with TCH1516, and is characterized by a different spa-type (t932) and PFGE type from other USA300-LV isolates [13].

Figure 2.

Circular whole-genome alignment of closed circular Staphylococcus aureus USA300 lineage genomes. Width of each circular track is relative to nucleotide identity as calculated by whole genome alignment based on mummer (available at: http://mummer.sourceforge.net). From inside out, the tracks are TCH1516 (gray), CA12 (yellow), M121 (green), CA15 (blue), HUV05 (red), and V2200 (orange). Areas of difference corresponding to mobile elements are noted. Abbreviation: ACME, arginine catabolic mobile element.

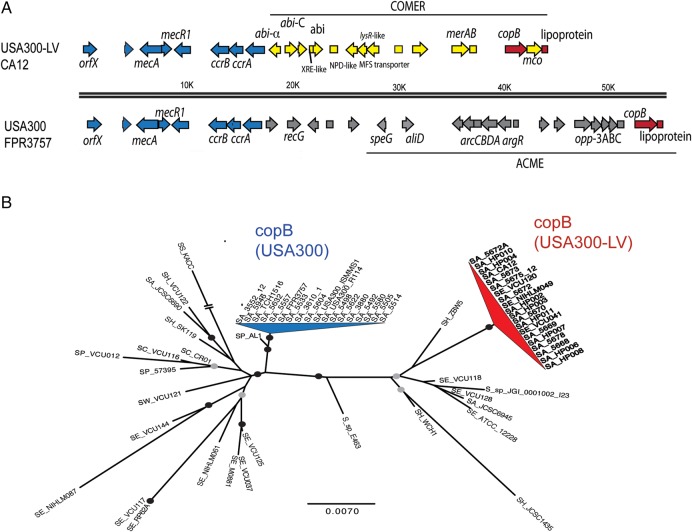

Most of the major differences between the genomes derive from regions that are integration sites of mobile genomic elements (Figure 2). To search for whole-gene differences that distinguish the NAE and SAE clades, we queried all of our sequences for genes that were exclusively found in the NAE and SAE clades. Several genes distinguish NAE and SAE individually from earlier branching strains. Most but not all members of these clades could be unambiguously classified by the combined presence or absence of these genes (Figure 1A). Only 2 genes were found that are exclusive to the combined NAE/SAE clade and found in >50% of the genomes: a gene encoding a putative ATPase copper exporter, copB (present in 83% of NAE genomes [15 of 18] and 72% of SAE genomes [13 of 18], respectively) and a putative lipoprotein (present in 83% [15 of 18] and 94% [17 of 18], respectively). Very similar genes are found in genomes of other staphylococcal species, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, and are found sporadically in S. aureus genomes in variants of the SCCmec mobile element [41] and on plasmids [42]. In USA300, the 2 genes are located in a single genetic locus at one end of ACME (Figure 3A). In USA300-LV strains, the 2 genes are located in a novel region that takes the place of the ACME immediately adjacent to the SCCmec element. This locus also contains genes for an abortive phage infection system and mercury resistance. We refer to this novel locus as the “COMER mobile element” because of its predicted function in copper and mercury resistance. Like ACME, phylogenetic analysis suggests that this locus is closely related to regions from S. epidermidis (Figure 3) but also that the copB gene was acquired in 2 distinct events in the NAE and SAE clades (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Comparison of locus adjacent to SCCmec element in North American epidemic (NAE) and the South American epidemic (SAE) Staphylococcus aureus strains. A, The arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) is characteristic of NAE strains, and the copper and mercury resistance (COMER) element is characteristic of SAE strains. Only the copB gene (corresponding to ABD21730.1 in FPR3757) and an adjacent putative lipoprotein (corresponding to ABD21221.1) are found in both elements. B, Unrooted maximum likelihood gene genealogy of copB genes from USA300 genomes and publicly available staphylococcal genome sequences. Clades for copB genes from North American USA300 (blue) and USA300 Latin American variant (USA300-LV; red) are distinct and appear to have been acquired in independent horizontal gene transfer events from other staphylococcal species. Black circles on branches represent nonparametric bootstrap values of 80%–100%; gray circles indicate bootstrap values of 50%–79%. The length of branches is proportional to the number of substitutions per site. Abbreviations: SA, S. aureus; SC, Staphylococcus capitis; SE, Staphylococcus epidermidis; SH, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; SP, Staphylococcus pettenkoferi; SS, Staphylococcus saprophyticus; SW, Staphylococcus warneri; SX, Staphylococcus xylosus; S_sp, Staphylococcus species.

DISCUSSION

The worldwide emergence and dissemination of CA-MRSA is an example of the ability of drug-resistant bacteria to establish a community reservoir and infect otherwise healthy individuals. In the United States, spread of MRSA strains belonging to the USA300 lineage occurred in a relatively short time, becoming an important public health problem [1]. Interestingly, apart from the United States, the only other part of the world where USA300-like strains have become endemic is the northern region of South America (specifically, Colombia and Ecuador) [13]. Although genetically closely related to the prototypical USA300 strain [12], South American strains have distinct genetic characteristics, including a variant of the SCCmec IV cassette and the absence of the ACME locus [12, 13].

Since the report, in 2005, of the first patient infected with a CA-MRSA belonging to the USA300-LV lineage, dissemination and spread of this strain has occurred rapidly [13, 20], initially leading to the assumption that the USA300 epidemic had spread from North to South America [12]. However, our phylogenetic findings suggest that the CA-MRSA epidemic in South America began to disseminate independently of the USA300 epidemic from North America. It is notable that, by 2006, USA300-LV was already the predominant clone in Ecuador and represented 30% of hospital-associated isolates in Colombian hospitals [13], suggesting that USA300-LV likely was circulating in the region before 2005. Although the USA300-LV epidemic is less well characterized than its North American counterpart, its clinical and epidemiological characteristics appear to be similar [13, 20]. A recent study of the transmission dynamics of CA-MRSA USA300 in northern Manhattan, where there is a large Latin American population, reported a small number of isolates with characteristics of USA300-LV (ACME negative, PVL positive, SaPI5 positive, and SCCmec IVc) [43], raising the possibility of spread of the SAE clade to the United States.

On the basis of tip-calibrated phylogenetic analysis, genomic elements within SaPI5 that encoded PVL (lukSF-PVL) and the enterotoxins SEK (sek) and SEQ (seq) were present in the USA300 lineage many years before the emergence of the epidemic clades. Therefore, these genes are probably not the key evolutionary factors that explain the remarkable success of the epidemic lineages. Likewise, differences in gene regulation of phenol soluble modulins (psm genes) and alpha toxin (hla) may predate the recent epidemics since these genes are expressed at increased levels in other close relatives, such as USA500 [10, 39, 44].

While the acquisition of ACME does coincide with the beginning of the NAE clade, this locus is not found in the SAE clade. Therefore, ACME-encoded adaptations that have been described so far [16–18] cannot explain the success of the South American USA300-LV clone. However, the copB locus, which appears to have been acquired independently as part of the ACME and COMER loci, is uniquely shared between the 2 epidemics. It is likely that these genes are involved in copper homeostasis/resistance [42], and given the antimicrobial properties of copper and its important role in innate immune defense, it is tempting to speculate that this locus may provide an important fitness advantage to both epidemic clades [45, 46].

USA300-LV now appears to be the predominant circulating MRSA clone in both Colombia and Ecuador [13, 20]. Further sampling will help elucidate the relationships of these isolates to other USA300-like CA-MRSA that are circulating in the Americas. For instance, the specific relationship of the USA300-like vancomycin-resistant isolate (BR-VRSA) from a patient in São Paulo, Brazil [38], to USA300 and USA300-LV remains unclear. Indeed, in the present analysis this genome appears to belong to a distinct, albeit closely related genetic lineage.

Our identification of highly virulent and closely related MRSA clades that have spread over 2 large regions of the Americas in parallel over a fairly short period suggests either convergent acquisition of traits that enhanced virulence or significant adaptations that occurred in their common ancestor. Therefore, understanding the common attributes of SAE and NAE strains could help to uncover the molecular determinants of the rapid dissemination of these lineages. While the exact geographic origin of the NAE and SAE clades remains obscure, the repeated transmission of USA300 throughout the Americas highlights both the long-standing fitness and success of this lineage. Our study also has implications for public health surveillance and preparation. It seems clear that whole-genome sequencing constitutes a new gold standard for tracking epidemics, identifying emerging strains, and distinguishing robust molecular markers (eg, copB). Whole-genome sequencing can be used to more precisely target interventions or identify the possible sources of emerging disease. Moreover, it may quickly lead to identification of new genetic determinants of disease.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant R01 AI093749 to C. A. A. and grant K08AI101005 to P. J. P.), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant R01 GM080602 to D. A. R.), the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Clinical Scientist Development Award to P. J. P.), the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society/St. Jude Award (to P. J. P.), and the John M. Driscoll, Jr, MD Children's Fund (to P. J. P.).

Potential conflicts of interest. P. J. P. has received lecture fees, research support, and consulting fees from Pfizer. C. A. A. has received lecture fees from Pfizer, Actavis, Novartis, Cubist (Merck), The Medecins Company, and Astra-Zeneca; consulting fees from Cubist, Bayer, Theravance, and the Medecins Company; and research support from Theravance, Actavis Pharmaceuticals, and Cubist. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Talan DA, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ et al. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections in US emergency department patients, 2004 and 2008. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in outpatients, United States, 1999–2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15:1925–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Hospitalizations and deaths caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999–2005. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13:1840–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu H, Wier LM, Elixhauser A. Hospital stays for children, 2009. Statistical brief 118. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011. [PubMed]

- 5.Tenover FC, McDougal LK, Goering RV et al. Characterization of a strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus widely disseminated in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:108–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin or soft tissue infections in a state prison--Mississippi, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50:919–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298:1763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Tenover FC et al. Changes in the epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units in US hospitals, 1992–2003. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:389–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenover FC, Goering RV. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: origin and epidemiology. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 64:441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery CP, Boyle-Vavra S, Adem PV et al. Comparison of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pulsotypes USA300 and USA400 in a rat model of pneumonia. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez CA, Barrientes OJ, Leal AL et al. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Colombia. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:2000–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arias CA, Rincon S, Chowdhury S et al. MRSA USA300 clone and VREF--a U.S.-Colombian connection? N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2177–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reyes J, Rincón S, Díaz L et al. Dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 sequence type 8 lineage in Latin America. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:1861–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 2006; 367:731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goering RV, McDougal LK, Fosheim GE, Bonnstetter KK, Wolter DJ, Tenover FC. Epidemiologic distribution of the arginine catabolic mobile element among selected methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:1981–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi GS, Spontak JS, Klapper DG, Richardson AR. Arginine catabolic mobile element encoded speG abrogates the unique hypersensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus to exogenous polyamines. Mol Microbiol 2011; 82:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Clark JR et al. Functional modularity of the arginine catabolic mobile element contributes to the success of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 13:100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Planet PJ, LaRussa SJ, Dana A et al. Emergence of the epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 coincides with horizontal transfer of the arginine catabolic mobile element and speG-mediated adaptations for survival on skin. MBio 2013; 4:e00889-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portillo BC, Moreno JE, Yomayusa N et al. Molecular epidemiology and characterization of virulence genes of community-acquired and hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Colombia. Int J Infect Dis 2013; 17:e744–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiménez JN, Ocampo AM, Vanegas JM et al. CC8 MRSA strains harboring SCCmec type IVc are predominant in Colombian hospitals. PLoS One 2012; 7:e38576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson DA, Enright MC. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47:3926–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJ, Birol I. ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res 2009; 19:1117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chin CS, Alexander DH, Marks P et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Mehods 2013; 10:563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu JC, Lee EK, Egan MG, Sarkar IN, Coruzzi GM, DeSalle R. OrthologID: automation of genome-scale ortholog identification within a parsimony framework. Bioinformatics 2006; 22:699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 2003; 13:2178–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006; 22:2688–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanave C, Preparata G, Saccone C, Serio G. A new method for calculating evolutionary substitution rates. J Mol Evol 1984; 20:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Z. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from DNA sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate methods. J Mol Evol 1994; 39:306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogeneties: an approch usig the bootstrap. Evolution 1985; 39:783–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds OR, Moret BM, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? J Comput Biol 2010; 17:337–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol 2012; 29:1969–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drummond AJ, Nicholls GK, Rodrigo AG, Solomon W. Estimating mutation parameters, population history and genealogy simultaneously from temporally spaced sequence data. Genetics 2002; 161:1307–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drummond AJ, Ho SY, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol 2006; 4:e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kingman J. The coalescent. Stochastic Process Appl 1982; 13:235–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75 2011. http://mesquiteproject.org.

- 36.Lewis PO. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst Biol 2001; 50:913–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitch WM. Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specific tree topology. Syst Zoology 1971; 20:406–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi F, Diaz L, Wollam A et al. Transferable vancomycin resistance in a community-associated MRSA lineage. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1524–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benson MA, Ohneck EA, Ryan C et al. Evolution of hypervirulence by a MRSA clone through acquisition of a transposable element. Mol Microbiol 2014; 93:664–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uhlemann AC, Kennedy AD, Martens C, Porcella SF, DeLeo FR, Lowy FD. Toward an understanding of the evolution of Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 during colonization in community households. Genome Biol Evol 2012; 4:1275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shore AC, Coleman DC. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec: recent advances and new insights. Int J Med Microbiol 2013; 303:350–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker J, Sengupta M, Jayaswal RK, Morrissey JA. The Staphylococcus aureus CsoR regulates both chromosomal and plasmid-encoded copper resistance mechanisms. Environ Microbiol 2011; 13:2495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uhlemann AC, Dordel J, Knox JR et al. Molecular tracing of the emergence, diversification, and transmission of S. aureus sequence type 8 in a New York community. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:6738–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li M, Diep BA, Villaruz AE et al. Evolution of virulence in epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:5883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Festa RA, Thiele DJ. Copper at the front line of the host-pathogen battle. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soutourina O, Dubrac S, Poupel O, Msadek T, Martin-Verstraete I. The pleiotropic CymR regulator of Staphylococcus aureus plays an important role in virulence and stress response. PLoS Pathog 2010; 6:e1000894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.