Abstract

An updated model of the GABA(A) benzodiazepine receptor pharmacophore of the α5-BzR/GABA(A) subtype has been constructed prompted by the synthesis of subtype selective ligands in light of the recent developments in both ligand synthesis, behavioral studies, and molecular modeling studies of the binding site itself. A number of BzR/GABA(A) α5 subtype selective compounds were synthesized, notably α5-subtype selective inverse agonist PWZ-029 (1) which is active in enhancing cognition in both rodents and primates. In addition, a chiral positive allosteric modulator (PAM), SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2), has been shown to reverse the deleterious effects in the MAM-model of schizophrenia as well as alleviate constriction in airway smooth muscle. Presented here is an updated model of the pharmacophore for α5β2γ2 Bz/GABA(A) receptors, including a rendering of PWZ-029 docked within the α5-binding pocket showing specific interactions of the molecule with the receptor. Differences in the included volume as compared to α1β2γ2, α2β2γ2, and α3β2γ2 will be illustrated for clarity. These new models enhance the ability to understand structural characteristics of ligands which act as agonists, antagonists, or inverse agonists at the Bz BS of GABA(A) receptors.

1. Introduction

The gamma-amino butyric acid A (GABAA) receptor is a heteropentameric chloride ion channel. This channel is generally made up of two α-subunits, two β-subunits, and a single γ-subunit arranged in an αβαβγ fashion. The GABAA receptors (GABAAR) are responsible for a myriad of brain functions. Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) and negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) act on the benzodiazepine (BZ) site of the GABAAR which can change the conformation of the receptor to inhibit or excite the neurons associated with the ion channel. To date, researchers have been unable to get an X-ray crystal structure of a functional Bz/GABAAR ion channel. Recently, Miller and Aricescu [1] have reported the crystal structure of a homopentameric GABAAR containing the β3-subunit at 3 Å resolution. Although this work provides great promise that other heteropentameric GABAARs will be crystallized in the near future, molecular modeling and structure-activity-relationships (SARs) still remain key tools to find better subtype-selective binding agents.

2. Subtype Selective Ligands for α5 GABA(A)/Bz Receptors

Interest in BzR/GABA(A) α5 subtypes began years ago when it was realized that α5β3γ2 Bz/GABA(A) subtypes are located primarily in the hippocampus. More recently this interest has been confirmed by the report of Möhler et al. [2–5] on α5 “knock-in mice.” This group has provided strong evidence that hippocampal extrasynaptic α5 GABA(A) receptors play a critical role in associative learning as mentioned above [6–11].

Earlier we synthesized a series of α5 subtype selective ligands (RY-023, RY-024, RY-079, and RY-080) based on the structure of Ro 15-4513 and reported their binding affinity [6], as well as several ligands by Atack et al. [12]. These ligands are benzodiazepine receptor (BzR) negative modulators in vivo and a number of these compounds have been shown to enhance memory and learning [13]. One of these ligands was shown by Bailey et al. [6] to be important in the acquisition of fear conditioning and has provided further evidence for the involvement of hippocampal GABA(A)/BzR in learning and anxiety [13]. This is in agreement with the work of DeLorey et al. [7] in a memory model with a ligand closely related to α5 subtype selective inverse agonists RY-024 and RY-079 including PWZ-029 (1).

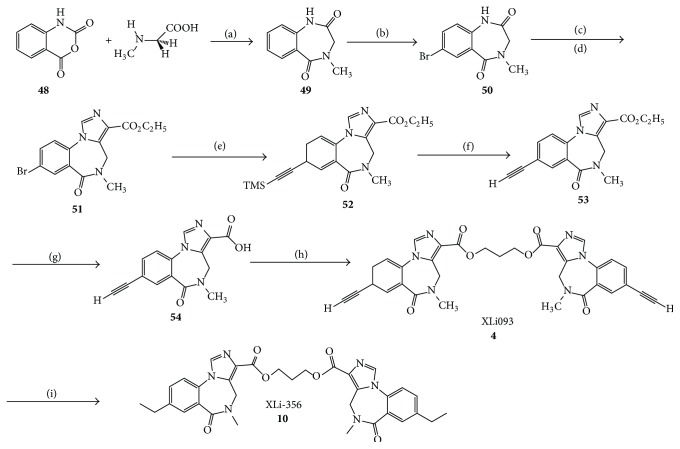

In order to enhance the α5 subtype selectivity, the bivalent form of RY-80 (3) was prepared to provide XLi-093 (4) [13]. The binding affinity of XLi-093 in vitro was determined on α 1–6 β3γ2 LTK cells and is illustrated in Figure 1. This bivalent ligand exhibited little or no affinity at α 1–4,6 β3γ2 BzR/GABA(A) subtypes, but this α5 ligand had a K i of 15 nM at the α5β3γ2 subtype [14]. Since this receptor binding study indicated bivalent ligand XLi-093 bound almost exclusively to the α5 subtype, the efficacy of this ligand on GABA(A) receptor subtypes expressed in Xenopus oocytes was investigated by Sieghart, Furtmueller, Li, and Cook [14, 15]. Analysis of the data indicated that XLi-093 up to a concentration of 1 μM did not trigger chloride flux in any one of the GABA(A) subtypes tested. At 1 μM XLi-093 did not modulate GABA induced chloride flux in α1β3γ2, α2β3γ2, or α3β3γ2 receptors, but very slightly inhibited chloride flux in α5β3γ2 subtypes. At 1 μM, XLi-093 barely influenced benzodiazepine (Valium) stimulation of GABA-induced current in α1β3γ2, α2β3γ2, and α3β3γ2 BzR but shifted the diazepam dose response curve to the right in α5β3γ2 receptors in a very significant manner [16]. Importantly, bivalent ligand XLi-093 was able to dose dependently and completely inhibit diazepam-stimulated currents in α5β3γ2 receptors. This was the first subtype selective benzodiazepine receptor site antagonist at α5 receptors. This bivalent ligand XLi-093 provided a lead compound for all of the bivalent ligands in this research [16].

Figure 1.

Alpha 5 selective compounds [13]. This figure is modified from that reported in [13].

Illustrated in Figure 2 is XLi-093 (4) aligned excellently within the pharmacophore-receptor model of the α5β3γ2 subtype [14, 16–19]. The fit to the pharmacophore-receptor and the binding data indicate that bivalent ligands will bind to BzR subtypes [14, 19]. It is believed that the dimer enters the binding pocket with one monomeric unit docking while the other monomer tethered by a linker extends out of the protein into the extracellular domain. If this is in fact true that the second imidazole unit is protruding into the extracellular domain of the BzR/GABA(A) α5 binding site, it could have a profound effect on the ligand design. This means other homodimers or even heterodimers may bind to BzR/GABA(A)ergic sites.

Figure 2.

XLi-093 (4) aligned in the included volume of the pharmacophore receptor model for the α5β3γ2 subtype [17, 18] (this figure is modified from the figure in Clayton et al., 2007) [23].

In this vein, Wenger, Li, and Cook et al. [13, 20, 21] earlier described preliminary data that XLi-093, an α5 subtype selective antagonist, enhances performance of C57BL/6J mice under a titrating delayed matching to position schedule of cognition, as illustrated in Figure 3 [14, 16–19]. This indicates, however, that this agent does cross the blood brain barrier.

Figure 3.

XLi-093 (4) effects on cognition enhancement by Wenger et al. (data on statistical significance not shown, unpublished results). Effects of 4 on cognition from the mean delay achieved by C57BL/6J mice titrating delayed matching-to-position schedule.

Bivalent ligands have a preferred linker of 3–5 methylene units, between the two pharmacophores (see XLi-093). This was established by NMR experiments run at low temperatures, X-ray crystallography, and molecular modeling of the ligands in question and will be discussed [14, 17, 18].

Based on this data, additional α5-subtype selective ligands have been prepared (see Figure 4). The basic imidazobenzodiazepine structure has been maintained [7]; however substituents were varied in regions around the scaffold based on molecular modeling [6]. These are now the most α5 subtype selective ligands ever reported [22]. Moreover, the ability to increase the subtype selectivity can be done by selecting specific substituents on these ligands to new agents with 400–1000-fold α5-selectivity over the remaining 5 subtypes. This is an important step forward to understanding the true, unequivocal physiological responses mediated by α5 subtypes in regard to cognition (amnesia), schizophrenia, anxiety, and convulsions, all of which in some degree are influenced by α5 subtypes. Based on the ligands in Figures 4 and 5, affinity has occurred principally at α5 subtypes. In addition, since XLi-093 bound very tightly only to α5 BzR subtypes, the bivalent nature and functionality presented here can be incorporated into other dimeric ligands.

Figure 4.

Binding data of selected imidazobenzodiazepines [22].

Figure 5.

Binding data of selected imidazobenzodiazepines substituted with an E-ring as compared to XLi-356 (10).

As shown previously in Figure 3, α5-antagonist XLi-093 (4) was shown to enhance cognition. In another study, a reduction of the two acetylenic groups of XLi-093 resulted in ethyl groups [14], providing a new bivalent ligand (XLi-356, 10) which shows α5-selective binding with very low affinity for α1 subtypes (Figure 5). Efficacy (oocyte) data shows XLi-356 is an α5 negative allosteric modulator [7, 13]. DeLorey et al. have recently shown in mice that XLi-356 does potently reverse scopolamine induced memory deficits [7]. This bivalent α5 inverse agonist enhanced cognition in agreement with work reported from our laboratory on monovalent inverse agonists RY-10 [6] and RY-23 [7].

The dimers XLi-093 (4) and XLi-356 (10) were sent to Case Western Reserve (NIMH supported PDSP program, Roth et al.) for full panel receptor binding and they do not bind to other receptors at levels of concern (Table 1).

Table 1.

Full PDSP panel receptor binding reported (Roth [138]) for XLi-093 and XLi-356.

| Cook code | 5ht1a | 5ht1b | 5ht1d | 5ht1e | 5ht2a | 5ht2b | 5ht2c | 5ht3 | 5ht5a | 5ht6 | 5ht7 | α1A | β1B | α2A | α2B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XLi093 | ∗ | Repeat | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ |

| XLi356 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Cook code | α2C | Beta1 | Beta2 | CB1 | CB2 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | DAT | DOR | H1 | H2 | H3 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| XLi093 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ |

| XLi356 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Cook code | H4 | Imidaz oline | KOR | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | MDR | MOR | NET | NMDA | SERT | σ1 | σ2 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| XLi093 | ∗ | ∗ | 2,024.00 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ |

| XLi356 | ∗ | ∗ | 6,118.00 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ |

Data (“secondary binding”) are K i values. K i values are reported in nanomolar concentration, Case Western Reserve University. “∗” indicates “primary missed” (<50% inhibition at 10 µM). See full data of the PDSP screen in the report of Clayton [22].

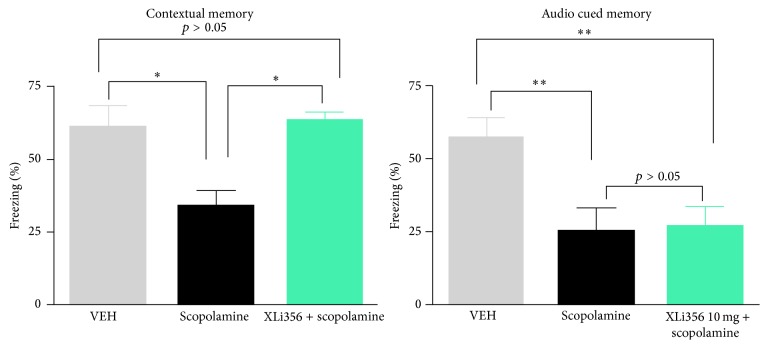

Although XLi-093 (4) was found to be an antagonist at the α5 subtype, XLi-356 (10) was found to be a weak agonist-antagonist. XLi-356 was found to reverse scopolamine induced memory deficits in mice. When XLi-356 was looked at in audio cued fear conditioning, the results show no activity. This suggests that the effect of XLi-356 is selective through α5 receptors which are abundant in the hippocampus which is highly associated with contextual memory. Audio cued memory instead is amygdala-based and should not be affected by an α5 subtype selective compound [39–42].

As illustrated in Figure 6, scopolamine (1 mg/kg) reduced freezing (i.e., impairs memory) generally due to coupling the context (the cage) with a mild shock. XLi-356 (10 mg/kg) attenuated the impairment of memory returning the freezing to the levels on par with subjects dosed with vehicle. In audio cued memory the response was activated by sound, not the context. XLi-356 was not able to reverse this type of memory effect which is amygdala driven. A similar effect was observed for XLi-093 by Harris et al. [43]. XLi-093 is the most selective antagonist for α5 subtypes reported to date [13, 43] and is a very useful α5 antagonist used by many in vivo [22, 44, 45].

Figure 6.

Visual and audio cued data for XLi-356 (10). This figure was modified from that in [22].

Molecular modeling combined with this knowledge was used to generate new lead compounds aimed at the development of α5-subtype selective positive and negative allosteric modulators to study cognition as well as amnesia mediated by the hippocampus. All of these compounds have been prepared based on the structure of current α5-subtype selective ligands synthesized in Milwaukee [46] (see Figures 4 and 5), as well as the binding affinity (15 nM)/selectivity of bivalent α5 antagonist XLi-093 (4) [13].

In efforts to enhance α5-selectivity in regards to cognition, Cook, Bailey, and Helmstetter et al. have employed RY-024 to study the hippocampal involvement in the benzodiazepine receptor in learning and anxiety [14, 19]. Supporting this Harris, DeLorey et al. show in mice that α5 NAMs (1) and RY-10 potently reversed scopolamine-induced memory impairment. These α5 NAMs provide insight as to how GABAARs influence contextual memory, an aspect of memory affected in age associated memory impairment and especially in Alzheimer's disease [13, 62–64]. In addition, Savić et al. have used the α1 preferring antagonist, BCCt, in passive avoidance studies, in which midazolam's amnesic effects are shown to be due to interaction of agonist ligands at α5 in addition to α1β3γ2 BzR subtypes [24, 65].

3. PWZ-029: A Negative Allosteric Modulator

PWZ-029 (1) has been studied extensively as an α5-GABAAR inverse agonist and in certain experimental models has been shown to enhance cognition. The binding data from three separate laboratories (Table 2) have all shown that it exhibits remarkable selectivity for the α5 subunit-containing receptors, all greater than 60-fold compared to the next subunit.

Table 2.

Affinity of PWZ-029 (1); K i (nM)a.

| Code | MW | α1 | α2 | α3 | α4 | α5 | α6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWZ-029 (1) | 291.73 | >300 | >300 | >300 | ND | 38.8 | >300 |

| PWZ-029 (1) | 291.73 | 920 | ND | ND | ND | 30 | ND |

| PWZ-029 (1) | 291.73 | 362 | 180 | 328 | ND | 6 | ND |

aData from three separate laboratories.

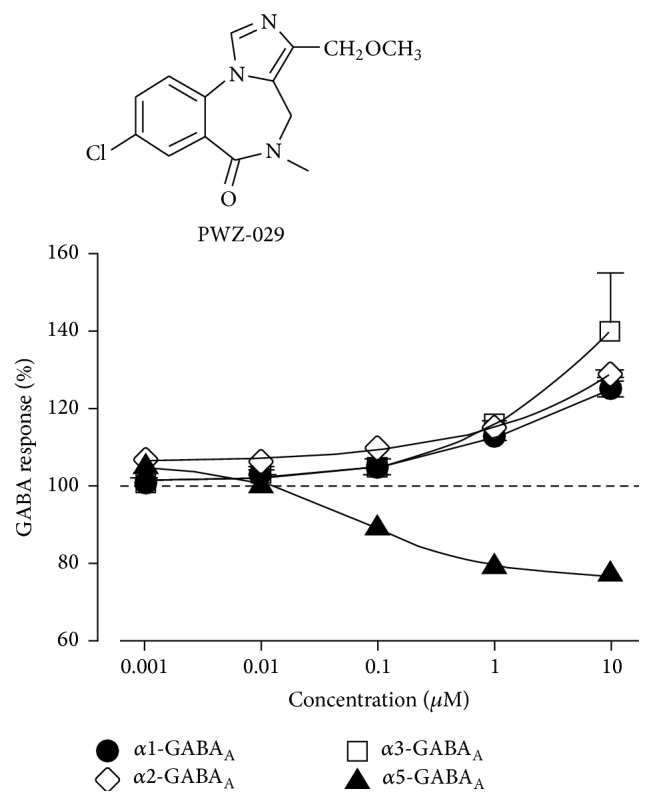

Electrophysiological efficacy testing done by Sieghart et al. in oocytes demonstrated that PWZ-029 (1) acts as a negative allosteric modulator at the α5-subunit, with a very weak agonist activity at the α1, α2, and α3 subunits (Figure 7). At a pharmacologically relevant concentration of 0.1 μM, PWZ-029 exhibits moderate negative modulation at the α5-subunit, while showing little or no effect at the α1, α2, or α3-subunits.

Figure 7.

Oocyte electrophysiological data of PWZ-029 (1) [24].

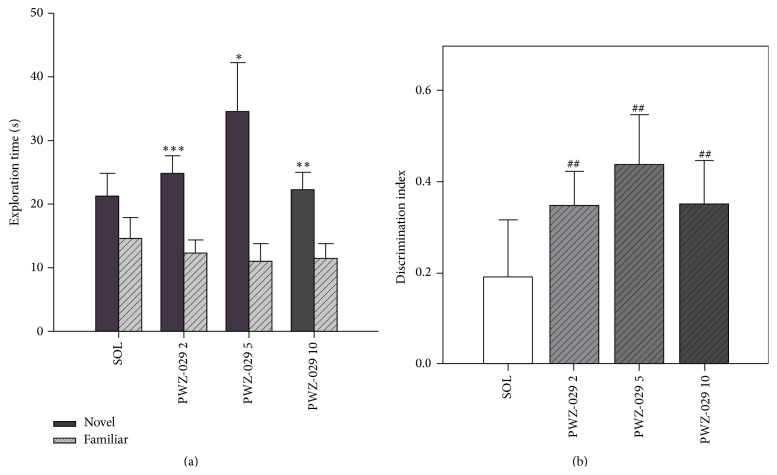

Milić et al. reported on the effects of PWZ-029 in the widely used novel object recognition test, which differentiates between the exploration time of novel and familiar objects. As shown by significant differences between the exploration times of the novel and familiar object (Figure 8(a)), as well as the respective discrimination indices (Figure 8(b)), all the three tested doses of PWZ-029 (2, 5 and 10 mg/kg) improved object recognition in rats after the 24 h delay period. Additionally, in the procedure with the 1 h delay between training and testing, the lowest of the tested doses of PWZ-029 (2 mg/kg) successfully reversed the deficit in recognition memory induced by 0.3 mg/kg scopolamine (Figure 9) [25].

Figure 8.

The effects of PWZ-029 (1) (2, 5 and 10 mg/kg) on (a) time exploring familiar and novel objects and (b) discrimination indices in the novel object recognition test using a 24 h delay (mean + SEM). Significant differences are indicated with asterisks (paired-samples t-test, novel versus familiar, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001). A significant difference from zero is indicated with hashes (one sample t-test, ## p < 0.01). The number of animals per each treatment group was 10. SOL = solvent [25].

Figure 9.

The effects of 0.3 mg/kg scopolamine (SCOP 0.3) and combination of 0.3 mg/kg scopolamine and PWZ-029 (1) (2, 5, and 10 mg/kg) on the rats' performance in the object recognition task after a 1 h delay: (a) time exploring familiar and novel objects and (b) discrimination index. Data are represented as mean + SEM. Significant differences are indicated with asterisks (paired-samples t-test, novel versus familiar, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01). A significant difference from zero is indicated with hashes (one sample t-test, # p < 0.05). The number of animals per each treatment group was 12–15. SAL = saline, SOL = solvent [25].

The results of the described study showed for the first time that inverse agonism at α5-GABAA receptors may be efficacious in both improving cognitive performance in unimpaired subjects and ameliorating cognitive deficits in pharmacologically impaired subjects, as assessed in two protocols of the same animal model [25].

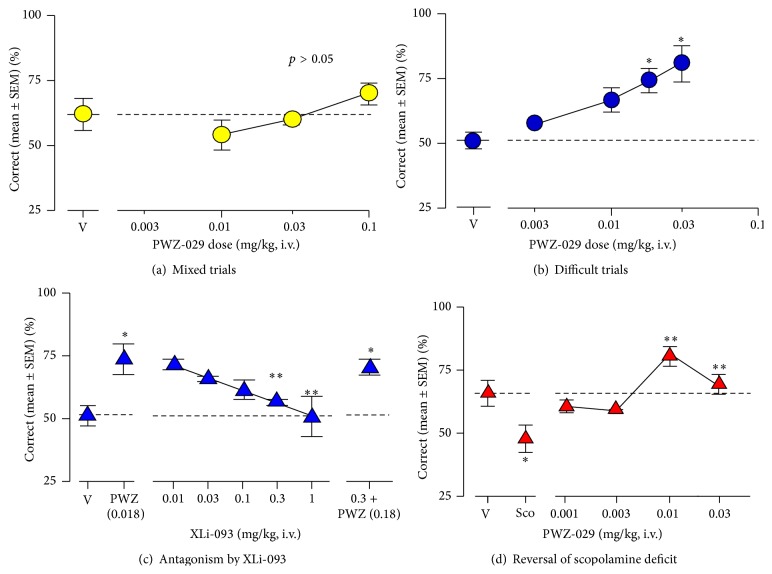

In a recent by Rowlett et al. [26], negative allosteric modulator PWZ-029 was evaluated in female rhesus monkeys (n = 4) in an Object Retrieval test with Detours (ORD; Figure 10 for details). 1 was administered via i.v. catheters in ORD trained monkeys and evaluated for cognition enhancement. A successful trial was determined by the ability of the subject to obtain a food reward within a transparent box with a single open side, with varying degrees of difficulty (“easy” or “difficult” or “mixed” as a combination of both) based on food placement within the box. In “mixed” trials using PWZ-029, no significant results were observed when compared to vehicle (Figure 11(a)). “Difficult” trials, however, exhibited an increasing dose-dependent curve for successful trials (Figure 11(b)). These results were attenuated by a coadministration α5-antagonist XLi-093 (Figure 11(c)). PWZ-029 was also shown to dose-dependently reverse the cholinergic deficits that were induced by scopolamine (Figure 11(d)) [26].

Figure 10.

ORD methods and procedure [26].

Figure 11.

Cognitive-enhancing effects of PWZ-029 in the rhesus monkey Object Retrieval with Detours (ORD) task (n = 5 monkeys). (a) Effects of PWZ-029 on ORD tests consist of both easy and difficult trials: (b) PWZ-029 enhanced performance on the ORD task when tested with difficult trials only; (c) enhancement of ORD performance by 0.018 mg/kg of PWZ-029 was attenuated by the α5 GABAA-preferring antagonist XLi-093 and this antagonism was surmountable by increasing the PWZ-029 dose; (d) PWZ-029 reversed performance impaired by 0.01 mg/kg of scopolamine [26]. ∗ p < 0.05 versus vehicle, ∗∗ p < 0.05 versus Scopolamine.

These findings suggest that PWZ-029 can enhance performance on the ORD task, only under conditions in which baseline performance is attenuated. The effects of PWZ-029 were antagonized in a surmountable fashion by the selective α5-GABAA ligand, XLi-093, consistent with PWZ-029's effects being mediating via the α5-GABAA receptor. The results are consistent with the view that α5 GABAA receptors may represent a viable target for discovery of cognitive enhancing agents.

In addition, we have new data showing that modulation of α5-GABAARs by PWZ-029 rescues Hip-dependent memory in an AD rat model [PMID: 23634826] as evidenced by a significant decrease in the latency to reach the hidden platform (memory probe trials) on spatial water maze task (Figure 12). Roche has employed a similar strategy at α5 subtypes and recently has a drug in the clinic to treat symptoms of dementia in Down syndrome patients. It is well known many Down syndrome patients develop Alzheimer's disease or a dementia with a very similar etiology. This is aimed at treating early onset Alzheimer's patients.

Figure 12.

PWZ-029 rescues spatial memory deficits in AD model as evidenced by a decrease in the latency to reach the hidden platform (probe test) in the water maze relative to vehicle (VEH, ∗ p < 0.05).

4. PWZ-029 Docking within α5γ2 GABAA Receptor Subunit Homology Model

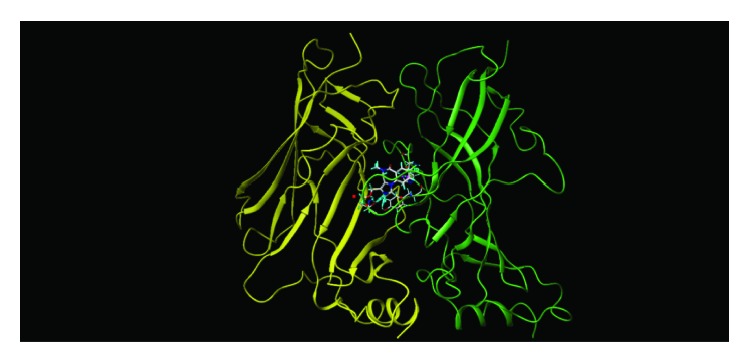

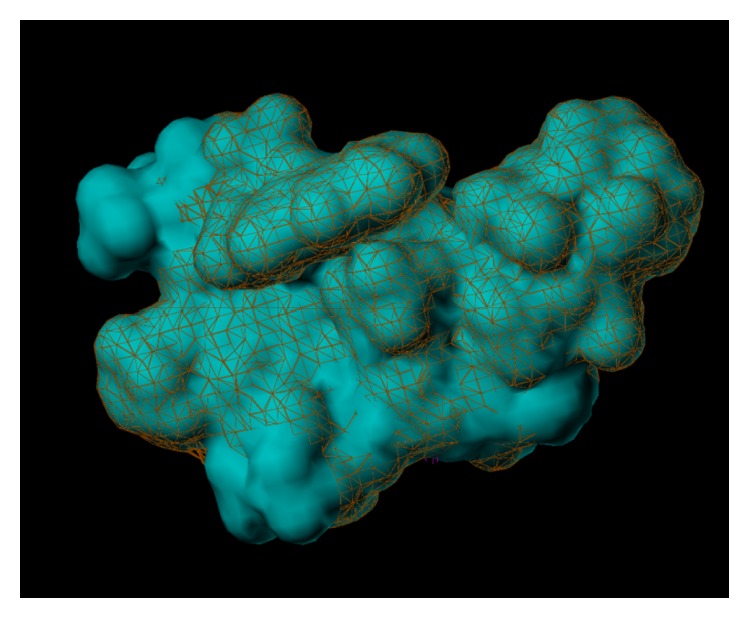

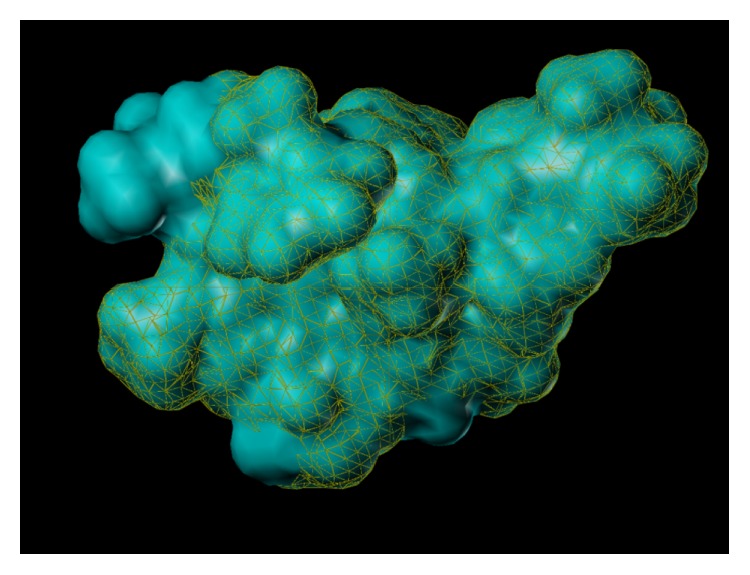

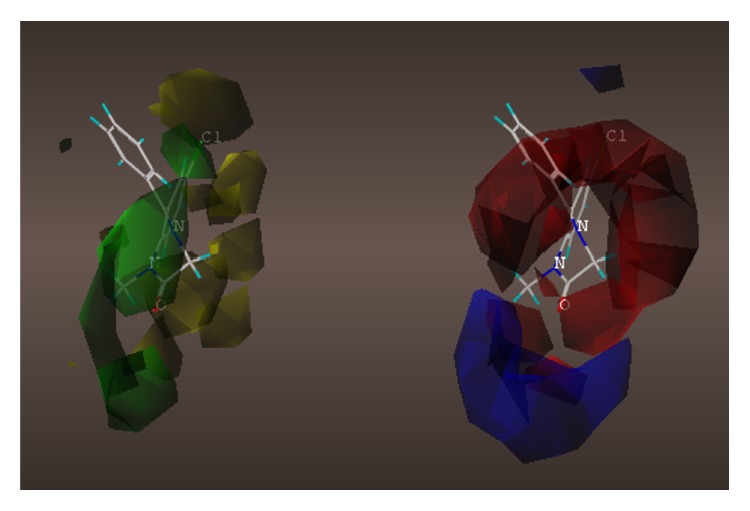

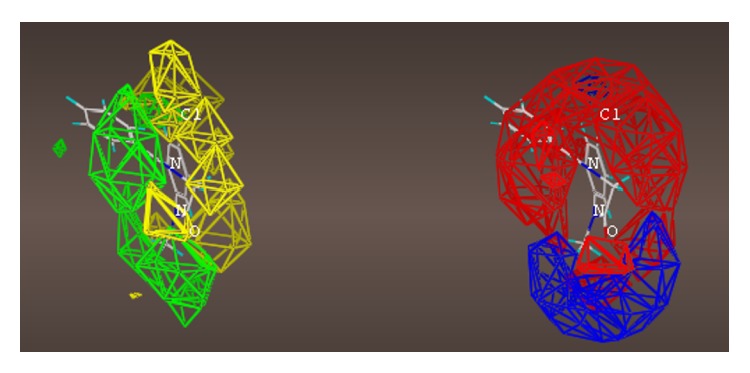

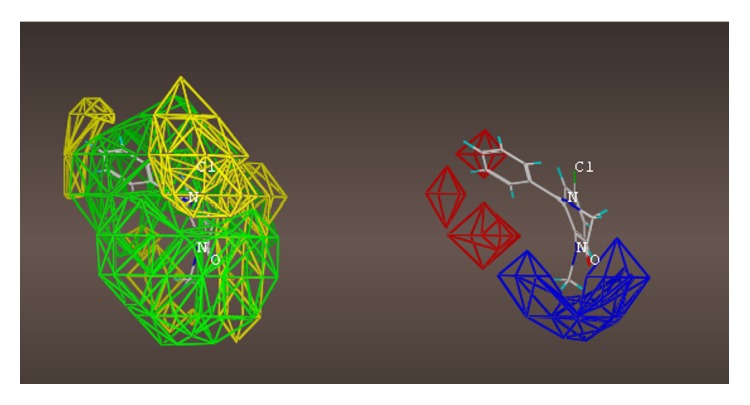

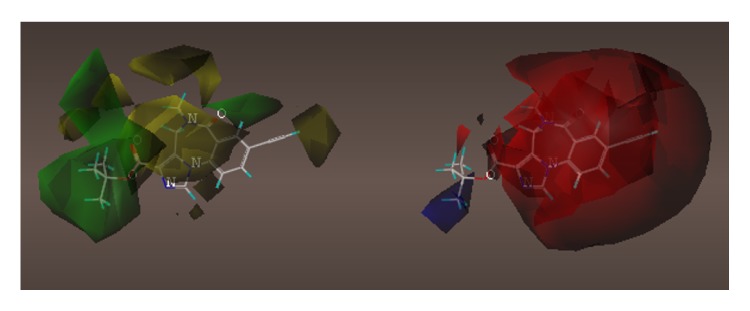

These studies with PWZ-029 led to the molecular model rendering of the compound docked within the α5γ2 BzR subtype (Figures 13– 16). The model figures have the following features:

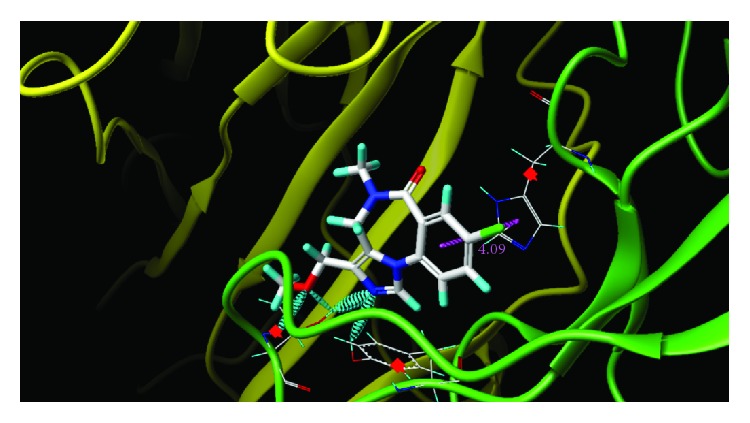

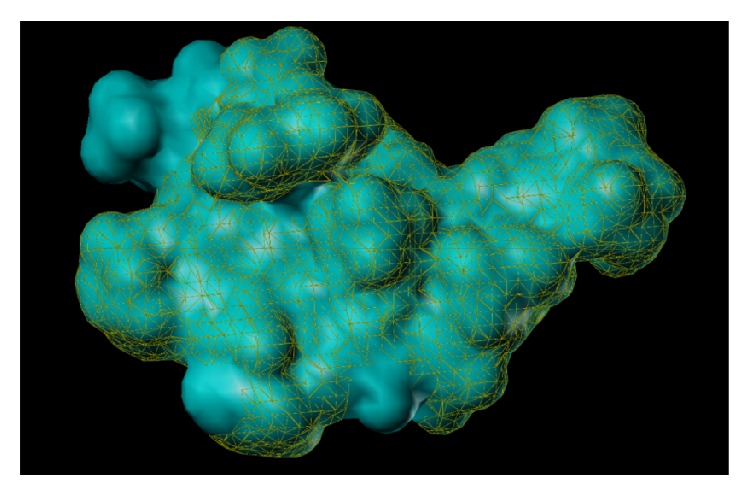

Figure 13.

PWZ-029 docked within α5γ2 BzR binding site (BS).

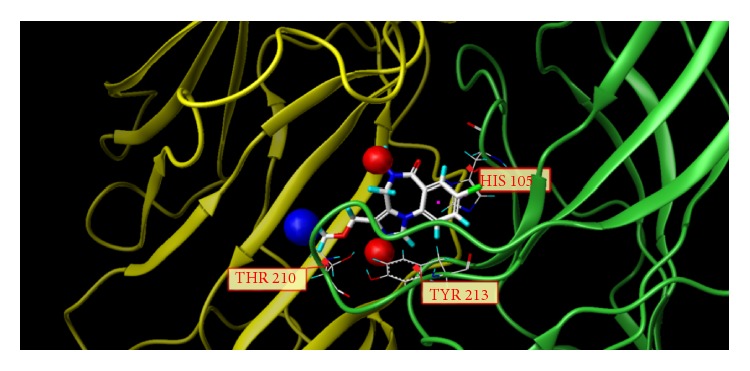

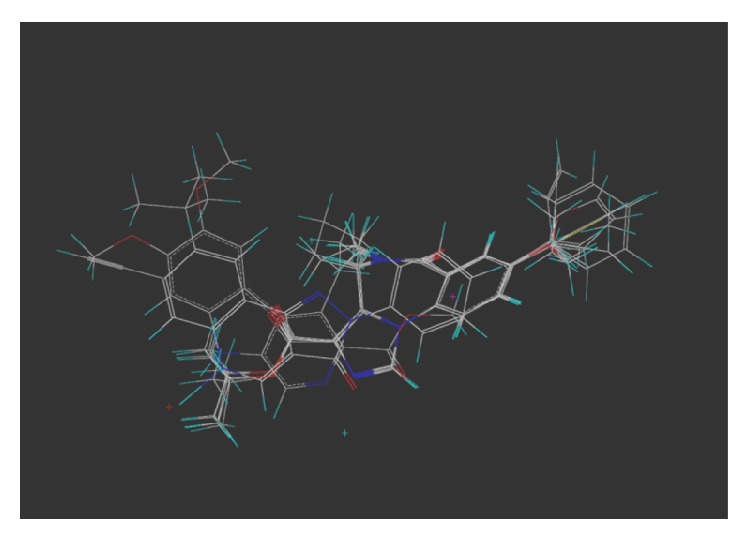

Figure 14.

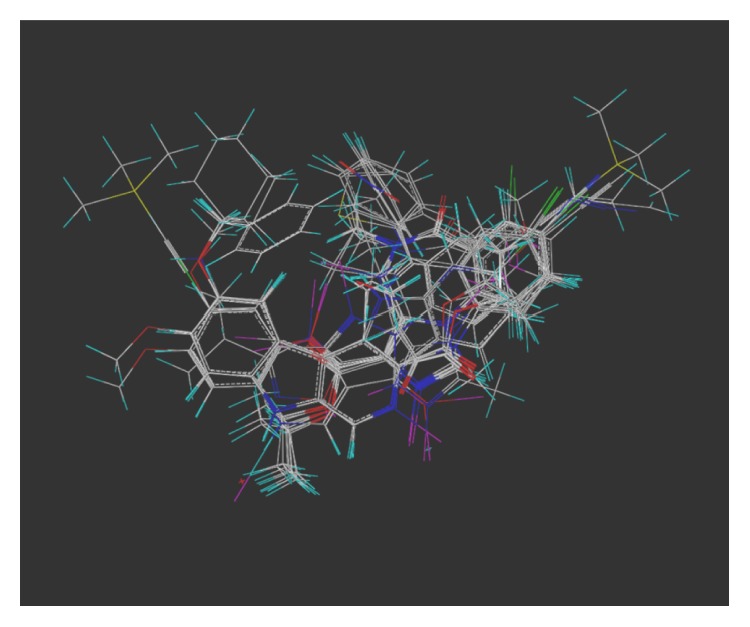

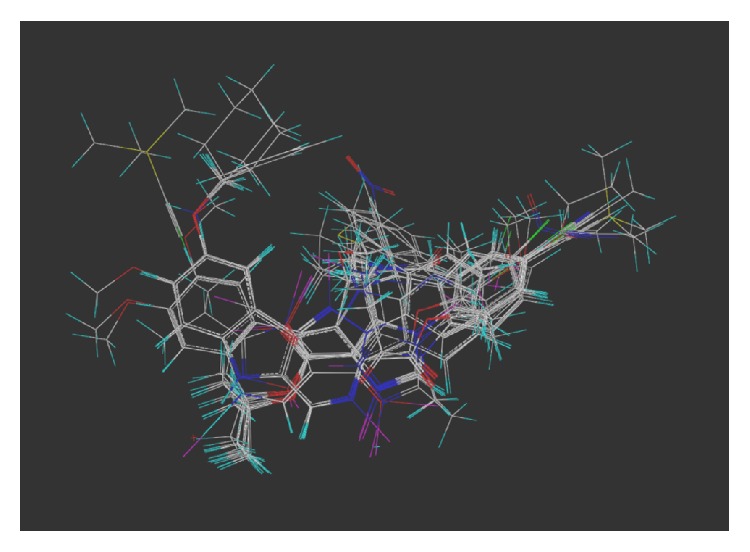

PWZ-029 docked with amino acid residues.

Figure 15.

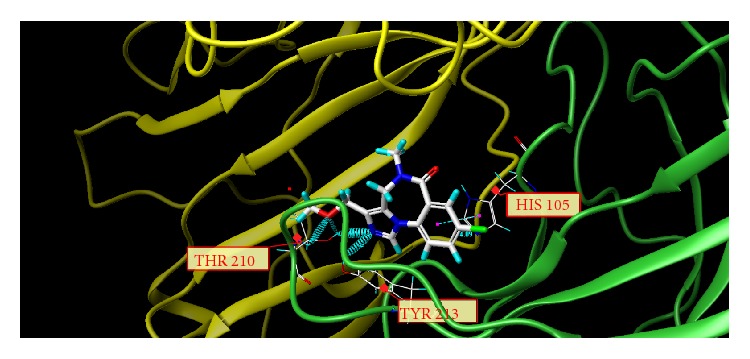

PWZ-029 docked with A.A. residue interactions.

Figure 16.

PWZ-029 docked with interactions. (1) HIS 105 π-stacking interaction with centroid of PWZ-029. (2) TYR 213 phenol OH hydrogen bonding to imidazole nitrogen lone pair. (3) THR 210 OH and lone pair on methoxy of PWZ029. (4) α5 ribbon being green. (5) γ2 ribbon being yellow. (6) Hydrogen bonding being aqua blue. (7) π-stacking being magenta.

The docking of PWZ-029 within the GABAA/BzR shows the molecule bound and interacting with specific amino acids. The A and B rings of the benzodiazepine framework undergo a π-stacking interaction with HIS 105, indicated by the magenta coloring. At the other end of the molecule the methoxy lone pair and imidazole nitrogen lone pair act as a hydrogen bond acceptors with THR 210 and TYR 213, respectively. These interactions are shown by the aqua-blue descriptors.

5. Subtype Selective Agonists for α5 GABAA/Bz Receptors

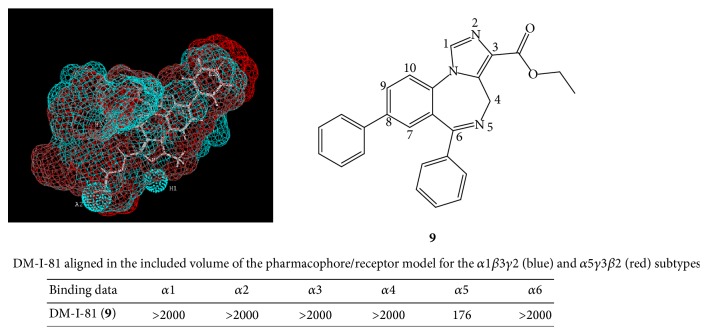

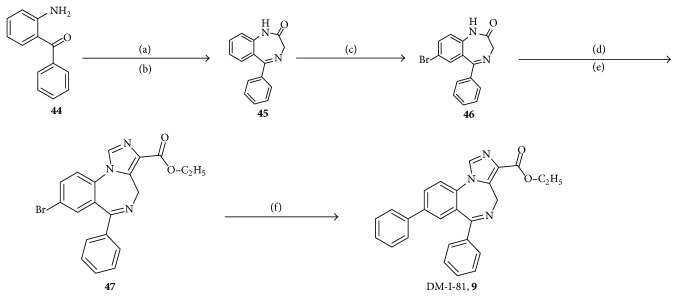

Möhler has proposed that α5 selective inverse agonists or α5 selective agonists might enhance cognition [5, 13, 16–18, 86]. This is because of the extrasynaptic pyramidal nature of α5β3γ2 subtypes, located almost exclusively in the hippocampus. Because of this, a new “potential agonist” which binds solely to α5β3γ2 subtypes was designed by computer modeling (see Figure 17). This ligand (DM-I-81, 9) has an agonist framework and binds only to α5β3γ2 subtypes [13, 17, 18, 86]. The binding potency at α5 subtypes is 176 nM. Although the 8-pendant phenyl of DM-I-81 was lipophilic and bound to the L 2 pocket, additional work on the 8-position of this scaffold has been abandoned and generally left as an acetylene or halide function, with a few exceptions. The steric bulk of the 8-phenyl moiety was felt detrimental to activity and potency which may have led to the weak binding affinity.

Figure 17.

The α5 selective agonist DM-I-81 (9), bound within the α1 and α5 subtypes. Binding data shown as K i (nM).

6. Alpha 5 Positive Allosteric Modulators in Schizophrenia

In addition to inverse agonists, a number of other α5-GABAAR positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) have been synthesized. These compounds, such as SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2), have been shown to decrease the firing rate of synapses controlling cognition and can be used to treat schizophrenia.

The following is reported by Gill, Cook, and Grace et al. [27–38].

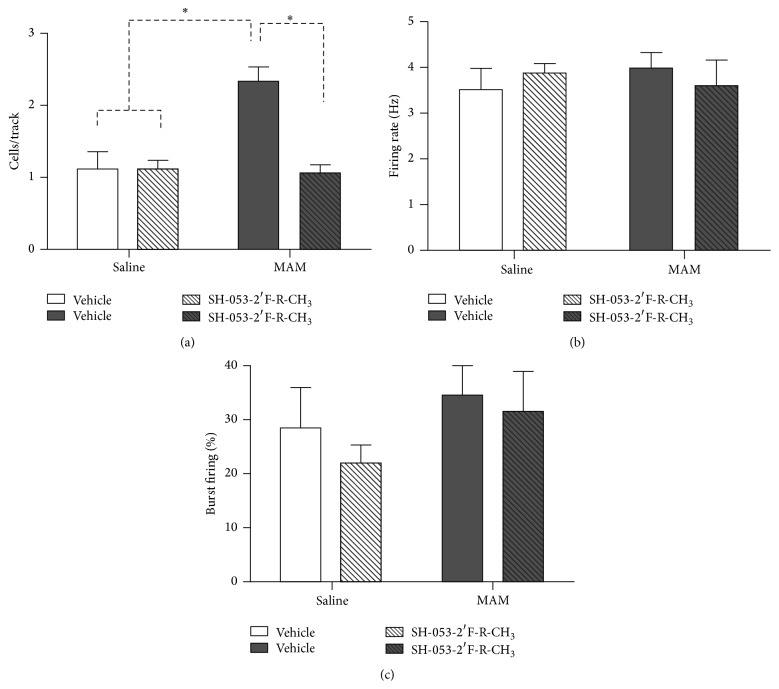

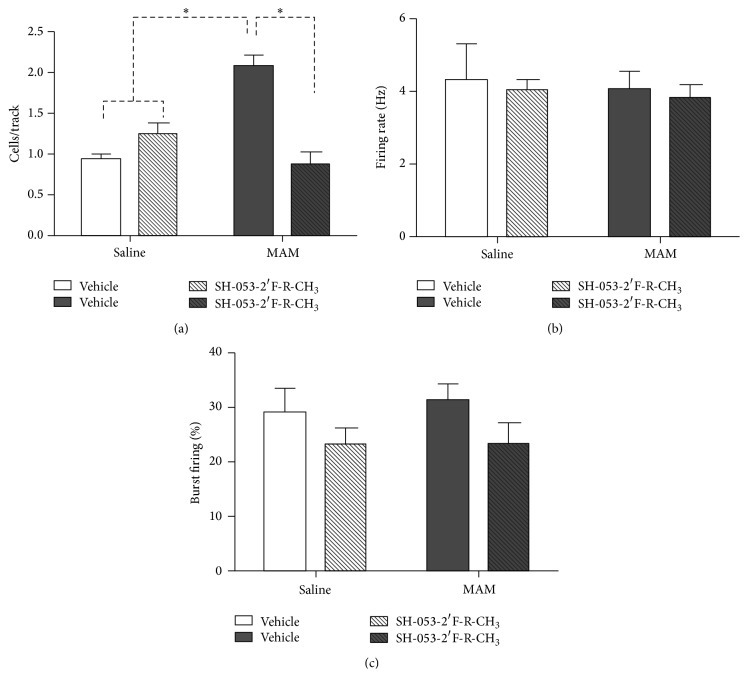

There are a number of novel benzodiazepine-positive allosteric modulators (PAMs), selective for the α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor, including SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2), which has been tested for its ability to effect the output of the HPC (hippocampal) in methylazoxymethanol- (MAM-) treated animals, which can lead to hyperactivity in the dopamine system [27–38]. In addition, the effect of this compounds (2) response to amphetamine in MAM-animals on the hyperactive locomotor activity was examined. Schizophrenic-like symptoms can be induced into rats when treated prenatally with DNA-methylating agent, methylazoxymethanol, on gestational day (GD) 17. These neurochemical outcomes and changes in behavior mimic those found in schizophrenic patients. Systemic treatment with (2) resulted in a reduced number of spontaneously active DA (dopamine) neurons in the VTA (ventral tegmental area) of MAM animals (Figure 18) to levels seen in animals treated with vehicle (i.e., saline). To confirm the location of action, 2 was also directly infused into the ventral HPC (Figure 19) and was shown to have the same effect. Moreover, HPC neurons in both SAL and MAM animals showed diminished cortical-evoked responses following α5-GABAAR PAM treatment. This study is important for it supports a treatment of schizophrenia that targets abnormal HPC output, which in turn normalized dopaminergic neuronal activity [27–38]. This is a novel approach to treat schizophrenia.

Figure 18.

Treatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.; patterned bars) normalizes the aberrant increase in the number of spontaneously firing dopamine neurons (expressed as cells/track) in methylazoxymethanol acetate- (MAM-) treated animals (a). There was no effect of SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 treatment in control animals (open bars, (a)–(c)) or on firing rate and burst activity in MAM animals (dark bars; (b)-(c)) (∗ p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post hoc; N = 5–7 rats/group) [27–38].

Figure 19.

Hippocampal (HPC) infusion of SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (1 μM/side; patterned bars) normalizes the aberrant increase in the number of spontaneously firing dopamine neurons (expressed as cells/track) in methylazoxymethanol acetate- (MAM-) treated animals (a). There was no effect of SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 treatment in control animals (open bars, (a)–(c)) or on firing rate in MAM animals (dark bars; (b)). Hippocampal (HPC) infusion of SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 significantly reduced the percentage of spikes occurring in bursts of dopamine (DA) neurons in MAM and control animals (c) (∗ p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post hoc; N = 7 rats/group) [27–38].

The pathophysiology of schizophrenia has identified hippocampal (HPC) dysfunction as a major mediator as reported by many including Anthony Grace [27–38]. This included morphological changes, reduced HPC volume, and GAD67 expression [27, 28] that have been reported after death in the brains of patients with schizophrenia. Both HPC activation and morphology changes have been identified that can precede psychotic symptoms or correlate with severity of cognitive deficits [29–33]. This has been shown in a cognitive test during baseline and activation.

Many animal models of schizophrenia were essential to behavioral pathology and have delivered new knowledge about the network disturbances that contribute to CNS disorder. This study shows that the offspring of MAM-treated animals showed both structural and behavioral abnormalities. These were consistent with those observed in patients with schizophrenia. The animals had reduced limbic cortical and HPC volumes with increased cell packing density and showed increased sensitivity to psychostimulants [34–36]. In addition, the startle response in prepulse inhibition was reduced in MAM-treated animals and deficits in latent inhibition were observed [35]. Furthermore, a pathological rise in spontaneous dopamine (DA) activity by the ventral tegmental area (VTA) was observed that can be attributed to aberrant activation within the ventral HPC [36]. It was suggested that reductions in parvalbumin- (PV-) stained interneurons might be the reason for the hyperactivation of the HPC and disruption of normal oscillatory activity in the HPC and cortex of MAM animals [38, 61]. At least this is the prevailing hypothesis at the moment put forth by many investigators (see references cited in [27–38]).

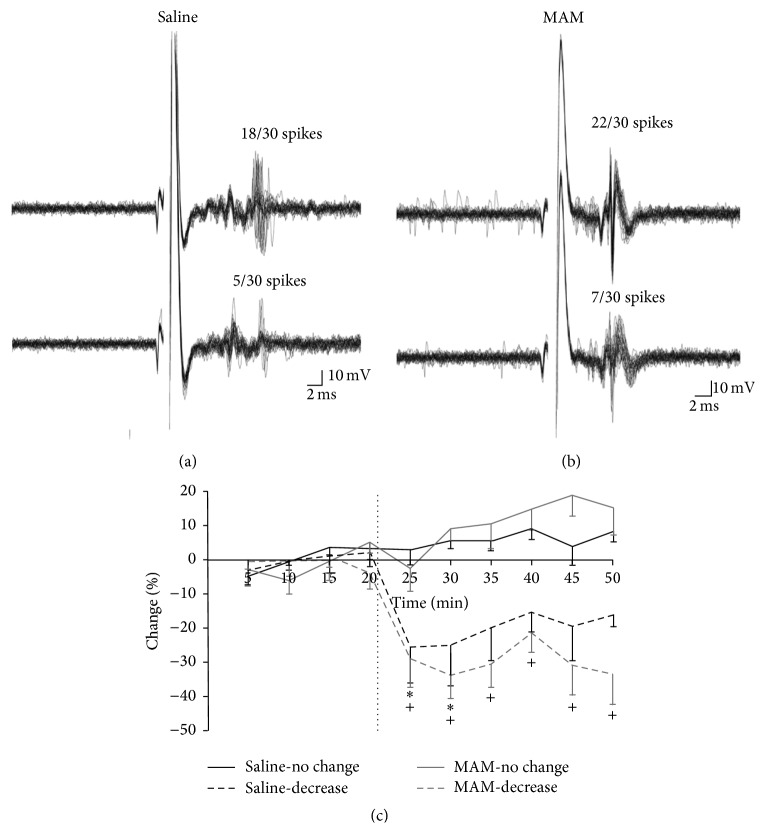

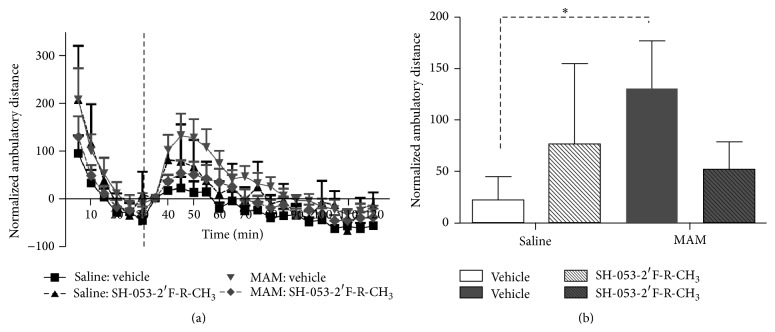

Selective α5-GABAAR positive allosteric modulator (2) was successful in reversing the pathological increase in tonic DA transmission in methylazoxymethanol rats by targeting abnormal hippocampal activity. In addition, the α5-PAM was able to reduce the behavioral sensitivity to psychostimulants observed in MAM rats (Figures 20 and 21). This suggests that novel α5-partial allosteric modulators should be effective in alleviating dopamine-mediated psychosis. However, if this drug can also restore rhythmicity within HPC-efferent structure, it may also affect other aspects of this disease state such as cognitive disabilities and negative symptoms. This study, using the MAM-model to induce symptoms of schizophrenia, shows that the use of α5-GABAAR targeting compounds could be an effective treatment in schizophrenic patients. The selective targeting solely of α5β3γ2 subunits, as opposed to unselective BZDs such as diazepam, could provide relief from the psychotic symptoms without producing adverse effects such as sedation [27–38].

Figure 20.

Extracellular recording traces illustrate the reduction in evoked responses in the ventral hippocampal (HPC) to entorhinal cortex stimulation in both MAM- and saline-treated animals (a, b). Treatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.) decreases the evoked excitatory response (dashed lines) of ventral HPC neurons to entorhinal cortex stimulation in both MAM- and saline-treated animals (c) (∗ p < 0.05 for saline and + p < 0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post hoc) [27–38].

Figure 21.

Treatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (10 mg/kg, i.p.) reduced the aberrant increased locomotor response to D-amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg i.p.) observed in MAM rats (a). MAM animals demonstrated a significantly larger peak locomotor response than both saline-treated animals and MAM animals pretreated with the alpha-5 PAM (b) (there was a significant difference between MAM-vehicle and all other groups, ∗ p < 0.05, two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Holm-Sidak post hoc) [27–38].

As reported by Gill, Grace et al. [36, 38, 47–61].

Often initial antipsychotic drug treatments (APD) for schizophrenia are ineffective, requiring a brief washout period prior to secondary treatment. The impact of withdrawal from initial APD on the dopamine (DA) system is unknown. Furthermore, an identical response to APD therapy between normal and pathological systems should not be assumed. In another study by Gill, Grace et al., α5 positive allosteric modulator SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) was used in the MAM neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia which was used to study impact of withdrawal from repeated haloperidol (HAL) on the dopamine system [36, 38, 47–61].

The following studies were designed to provide insight as to why a new drug to treat schizophrenia may be effective in Phase II clinical trials but fail in Phase III because of the large number of patients required for the study. Many of these patients in Phase III studies have altered neuronal pathways in the CNS because of long-term treatment with antipsychotics (sometimes 10–20 years) [36, 38, 47–61].

Importantly, spontaneous dopamine activity reduction was observed in saline rats withdrawn from haloperidol with an enhanced locomotor response to amphetamine, indicating the development of dopamine supersensitivity. In addition, PAM treatment, as well as ventral HPC inactivation, removed the depolarization block of DA neurons in withdrawn HAL treated SAL rats. In contrast, methylazoxymethanol rats withdrawn from HAL displayed a reduction in spontaneous dopamine activity and enhanced locomotor response that was unresponsive to PAM treatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 or ventral HPC inactivation [36, 38, 47–61].

Prior HAL treatment withdrawal can restrict the efficacy of subsequent pharmacotherapy in the MAM model of schizophrenia. This is an extremely important result indicating that testing a new drug for schizophrenia in humans treated for years with both typical and atypical antipsychotics may result in a false negative with regard to treatment. Studies that support this hypothesis follow here [36, 38, 47–61].

Novel therapeutics for the treatment of schizophrenia that exhibit initial promise in preclinical trials often fail to demonstrate sufficient efficacy in subsequent clinical trials. In addition, relapse or noncompliance from initial treatments is common, necessitating secondary antipsychotic intervention [47, 48]. Studies have shown that between 49 and 74% of schizophrenia patients discontinue the use of antipsychotic drug (APD) treatments within 18 months due to adverse side-effects [48, 49]. Current pharmacotherapies for schizophrenia target the pathological increase in dopamine system activity, as mentioned above. Common clinical practice for secondary antipsychotic application involves a brief withdrawal period from the initial APD. Unfortunately, the success of even secondary treatments is far from being optimal with the rehospitalization of patients being a common occurrence. The impact of repeated antipsychotic treatment and subsequent withdrawal on the dopamine system has not been adequately assessed [36, 38, 47–61].

As indicated above, schizophrenia is a complex chronic psychiatric illness characterized by frequent relapses despite ongoing treatment. The search for more effective pharmacotherapies for the treatment of schizophrenia continues unabated. It is not uncommon for novel pharmaceuticals to demonstrate promise in preclinical trials but fail to show an adequate response in subsequent clinical trials. Indeed, evaluating the benefits of one APD versus another is complicated by clinical trials beset with high attrition rates and poor efficacy in satisfactorily reducing rehospitalization [47, 49–52].

Previous work from the Gill, Grace et al.'s laboratory [36, 38, 47–61] with the MAM model of schizophrenia has identified a potential novel therapeutic, a α5GABAAR PAM. The dopamine system pathology in the MAM model is likely the result of excessive output from the ventral HPC [36]. The α5GABAAR PAM was identified as a potential therapeutic due to the relatively selective expression of α5GABAAR in the ventral HPC and its potential for reducing HPC activity [53–60]. When either administered systemically or directly infused into the ventral HPC, the α5GABAAR PAM (SH-053-2′F-R-CH3) was effective in reducing the dopamine system activation in MAM rats [38]. Anthony Grace, Gill et al. showed α5GABAAR PAM treatment was also effective in reducing the enhanced behavioral response to amphetamine in MAM rats, as stated above. Data from the present study sought to delineate whether the α5GABAAR PAM (SH-053-2′F-R-CH3) would remain effective in MAM rats withdrawn from prior neuroleptic treatment, a common occurrence in the patient population. In both SAL and MAM rats, there was a reduction in the spontaneous activity of dopamine neurons in the VTA after 7 days withdrawal from repeated HAL treatment. However, MAM rats continued to exhibit a greater activation of the dopamine system in comparison to SAL rats. Treatment with the α5GABAAR PAM was no longer effective in reducing the activity of dopamine neurons in the VTA in withdrawn HAL treated MAM rats. In contrast, α5GABAAR PAM treatment in the withdrawn HAL treated SAL rats instead increased the spontaneous activity of dopamine in the VTA (Figures 22 –25) [36, 38, 47–61].

Figure 22.

Repeated haloperidol treatment caused a reduction in the number of spontaneously active dopamine neurons in both SAL and MAM rats injected with vehicle compared to untreated control animals. Treatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.) reversed the haloperidol-induced reduction in cells/track in SAL, but not MAM, rats (a). Repeated haloperidol treatment had no effect on the firing rate of dopamine neurons recorded in SAL or MAM rats treated with vehicle. However, SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 caused an increase in firing rate of dopamine neurons in repeatedly haloperidol-treated SAL rats (b). Repeated haloperidol treatment, as well as SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 injection, had no impact on the percentage of spikes occurring in bursts for dopamine neurons recorded in SAL and MAM rats (c) [36, 38, 47–61]. ∗ p < 0.05.

Figure 23.

Repeated haloperidol treatment caused a reduction in the number of spontaneously active dopamine neurons in both SAL and MAM rats microinfused with vehicle in the ventral HPC compared to untreated control animals. Infusion of TTX in the ventral HPC reversed the haloperidol-induced reduction in cells/track in SAL, but not MAM, rats (a). Repeated haloperidol treatment had no effect on the firing rate of dopamine neurons recorded in SAL or MAM rats infused with vehicle or TTX in the ventral HPC (b). Repeated haloperidol treatment had no effect on the percentage of spikes occurring in bursts for dopamine neurons recorded in SAL or MAM rats infused with vehicle or TTX in the ventral HPC (c) [36, 38, 47–61]. ∗ p < 0.05.

Figure 24.

Administration of apomorphine (80 mg/kg i.v.) increased the number of spontaneously active dopamine neurons in SAL rats withdrawn from repeated HAL, while having no effect on the number of active dopamine neurons in MAM rats withdrawn from repeated HAL [36, 38, 47–61]. ∗ p < 0.05.

Figure 25.

Repeated haloperidol treatment causes an enhancement in the locomotor response to D-amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) in SAL animals that is reduced by pretreatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (10 mg/kg, i.p.) (a). MAM rats treated repeatedly with haloperidol exhibit a locomotor response following D-amphetamine similar to untreated MAM rats. However, repeated haloperidol treatment blocks the effect of SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 pretreatment in decreasing the locomotor response in MAM rats (b). Untreated MAM rats demonstrated a significantly larger peak locomotor response than untreated SAL rats. In addition, SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 pretreatment significantly reduced the peak locomotor response in untreated MAM rats, while having no effect in repeatedly haloperidol-treated MAM rats. In contrast, repeated haloperidol treatment enhanced the peak locomotor response to amphetamine in SAL rats that was reduced by SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 pretreatment (c) [36, 38, 47–61]. ∗ p < 0.05.

Similar to the effects seen following α5GABAAR PAM treatment, ventral HPC inactivation in withdrawn HAL treated SAL rats restored normal dopamine system activity by increasing the number of spontaneously active dopamine neurons. The disparate effect of withdrawal from HAL on the dopamine system between SAL and MAM rats provides a vital clue for the inconsistencies between preclinical trials for novel therapeutics that utilize normal subjects and subsequent clinical trials in a patient population [36, 38, 47–61].

The data suggests underlying dopamine system pathology alters the impact of withdrawal from prior repeated HAL in the MAM model of schizophrenia. In addition, subsequent novel APD treatment loses efficacy following withdrawal from repeated HAL in MAM animals. This certainly has relevance to Phase III clinical trials of new drugs to treat schizophrenia [36, 38, 47–61].

7. GABAA α5 Positive Allosteric Modulators Relax Airway Smooth Muscle

Emala, Gallos, et al. [66–75] have found that novel α5-subtype selective GABAA positive allosteric modulators relax airway smooth muscle from rodents and humans. The clinical need for new classes of bronchodilators for the treatment of bronchoconstrictive diseases such as asthma remains a major medical issue. Few novel therapeutics have been approved for targeting airway smooth muscle (ASM) relaxation or lung inflammation in the last 40 years [66]. In fact, several asthma-related deaths are attributed, in part, to long-acting β-agonists (LABA) [67]. Adherence to inhaled corticosteroids, the first line of treatment for airway inflammation in asthma, is very poor [68, 69]. Therapies that break our dependence on β-agonism for ASM relaxation would be a novel and substantial advancement.

These ASM studies were undertaken due to a pressing clinical need for novel bronchodilators in the treatment of asthma and other bronchoconstrictive diseases such as COPA. There are only three drug classes currently in clinical use as acute bronchodilators in the United States (methylxanthines, anticholinergics, and β-adrenoceptor agonists) [70]. Thus, a novel therapeutic approach that would employ cellular signaling pathways distinct from those used by these existing therapies involves modulating airway smooth muscle (ASM) chloride conductance via GABAA receptors to achieve relaxation of precontracted ASM [71, 72]. However, widespread activation of all GABAA receptors may lead to undesirable side effects (sedation, hypnosis, mucus formation, etc.). Thus, a strategy that selectively targets a subset of GABAA channels, those containing α subunits found to be expressed in airway smooth muscle, may be a first step in limiting side effects. Since human airway smooth muscle contains only α4 or α5 subunits [72], ligands with selectivity for these subunits are an attractive therapeutic option. Concern regarding nonselective GABAA receptor activation is not limited to the airway or other peripheral tissues. GABAA receptor ligands are classically known for their central nervous system effects of anxiolysis, sedation, hypnosis, amnesia, anticonvulsion, and muscle relaxant effects. Such indiscriminate activation of GABAA receptors in the CNS is exemplified by the side effects of classical benzodiazepines (such as diazepam) which were the underpinning for the motivation of a search for benzodiazepine (BZD) ligands that discriminate among the α subunits of GABAA receptors [73–75].

A novel approach to identify novel benzodiazepine derivatives to selectively target GABAA channels containing specific α subunits was developed by Cook et al. in the 1980s that employed a pharmacophore receptor model based on the binding affinity of rigid ligands to BDZ/GABAA receptor sites (as reviewed in 2007 [23]). From this series of receptor models for α 1–6 β3γ2 subtypes a robust model for α5 subtype selective ligands emerged, the result of which included the synthesis of a novel α5β3γ2 partial agonist modulator, SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2). The discovery of this and related ligands selective for α5 BDZ/GABAA-ergic receptors and the realization that only α4 and α5 subunits are expressed in GABAA channels on human airway smooth muscle yielded an ideal opportunity for targeting these α5-subunit containing GABAA channels for bronchorelaxation [66–75].

The GABAA α5 subunit protein was first localized to the ASM layer of human trachea while costaining for the smooth muscle specific protein α actin (Figure 26). The first panel of Figure 26 shows GABAA α5 protein stained with fluorescent green and blue fluorescent nuclear staining (DAPI). The second panel is the same human tracheal smooth muscle section simultaneously stained with a protein specific for smooth muscle, α actin, and the third panel is a merge of the first two panels showing costaining of smooth muscle with GABAA α5 and α actin proteins. The fourth panel is a control omitting primary antibodies but including nuclear DAPI staining [66–75].

Figure 26.

Protein expression of the GABAA α5 subunit in intact human trachea-bronchial airway smooth muscle. Representative images of human tracheal airway smooth muscle sections using confocal microscopy are depicted following single, double, and triple immunofluorescence labeling. The antibodies employed were directed against the GABAA α5 subunit (green), α-smooth muscle actin (SMA; red), and/or the nucleus via DAPI counterstain (blue). Panels illustrate the following staining parameters from left to right: (1st) costaining of DAPI and GABAA α5 subunit; (2nd) α-SMA staining alone; (3rd) triple-staining of GABAA α5, α-SMA, and DAPI; (4th) DAPI nucleus counterstain, with primary antibodies omitted as negative control. Modified from [66–75].

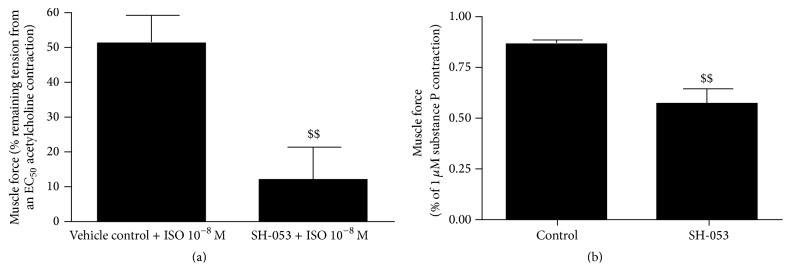

After demonstrating the protein expression of GABAA receptors containing the α5 subunit, functional studies of isolated airway smooth muscle were performed in tracheal airway smooth muscle from two species. Human airway smooth muscle suspended in an organ bath was precontracted with a concentration of acetylcholine that was the EC50 concentration of acetylcholine for each individual airway smooth muscle preparation. The induced contraction was then relaxed with a β-agonist (isoproterenol) in the absence or presence of the GABAA α5 ligand SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2). Figure 27(a) shows that the amount of relaxation induced by 10 nM isoproterenol was significantly increased if 50 μM SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) was also present in the buffer superfusing the airway smooth muscle strip. Studies were also performed in airway smooth muscle from another species, guinea pig, that measured direct relaxation of a different contractile agonist, substance P. As shown in Figure 27(b), the amount of remaining contractile force 30 minutes after a substance P-induced contraction was significantly reduced in airway smooth muscle tracheal rings treated with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) [66–75].

Figure 27.

SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) mediated activation of α5 subunit containing GABAA channels induces relaxation of precontracted airway smooth muscle. (a) SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) (SH-053) potentiates β-agonist-mediated relaxation of human airway smooth muscle. Cotreatment of human airway smooth muscle strips with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) (50 μM) significantly enhances isoproterenol (10 nM) mediated relaxation of an acetylcholine EC50 contraction compared to isoproterenol alone (N = 8/group, $$ = p < 0.01). Modified from [66–75]. (b) SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) activation of α5 containing GABAA receptors induces direct relaxation of substance P-induced airway smooth muscle contraction. Compiled results demonstrating enhanced spontaneous relaxation (expressed as % remaining force at 30 minutes following a 1 μM substance P mediated contraction) following treatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) compared to treatment with vehicle control (n = 4-5/group, $$ = p < 0.01) [66–75].

Following these studies in intact airway smooth muscle, cell based studies were initiated in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells to directly measure plasma membrane chloride currents and the effects of these currents on intracellular calcium concentrations. SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) induced a Cl− current in vitro using conventional whole cell patch clamp techniques [66–75]. These electrophysiology studies were then followed by studies to determine the effect of these plasma membrane chloride currents on intracellular calcium concentrations following treatment of human airway smooth muscle cells with a ligand whose receptor couples through a Gq protein pathway, a classic signaling pathway that mediates airway smooth muscle contraction.

SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) attenuated an increase in intracellular calcium concentrations induced by a classic Gq-coupled ligand, bradykinin (Figure 28(a)) [66–75]. The attenuation by SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) was significantly blocked by the GABAA antagonist gabazine (Figure 28(b)) indicating that SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) was modulating GABAA receptors for these effects on cellular calcium [66–75].

Figure 28.

SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) mediated activation of α5 containing GABAA receptors attenuates bradykinin-induced elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle cells. (a) Representative Fluo-4 Ca2+ fluorescence (RFU) tracing illustrating pretreatment with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) (SH-053) (10 μM) reduces cytosolic Ca2+ response to bradykinin (1 μM). This effect is reversed in the presence of gabazine (200 μM, GABAA receptor antagonist). Modified from [66–75]. (b) Compiled results illustrating SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) pretreatment of GABAA α5 receptors on human airway smooth muscle cells attenuates bradykinin-induced elevations in intracellular Ca2+ compared to levels achieved following pretreatment with vehicle control ($$ = p < 0.01). While gabazine-mediated blockade of GABAA channels does not significantly affect bradykinin-induced intracellular calcium increase compared to vehicle control, gabazine treatment did reverse SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) ability to attenuate bradykinin-induced elevations in intracellular calcium thereby illustrating a GABAA channel specific effect (n.s. = not significant). Modified from [66–75].

The major findings of these studies are that human airway smooth muscle expresses α5 subunit containing GABAA receptors that can be pharmacologically targeted by a selective agonist. The GABAA α5 subunit selective ligand SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) relaxed intact guinea pig airway smooth muscle contracted with substance P and augmented β-agonist-mediated relaxation of intact human airway smooth muscle. The mechanism for these effects was likely mediated by plasma membrane chloride currents that contributed to an attenuation of contractile-mediated increases in intracellular calcium, a critical event in the initiation and maintenance of airway smooth muscle contraction [66–75].

8. Recent Discovery of Alpha 5 Included Volume Differences: L 4 Pocket as Compared to Other Bz/GABAergic Subtypes

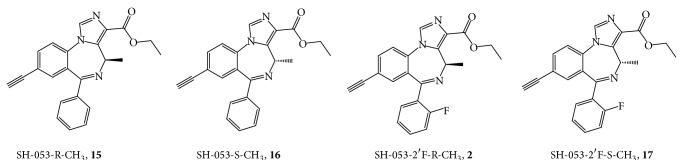

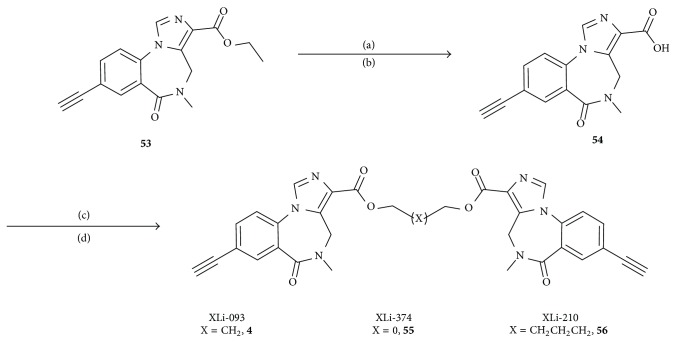

The findings in both the MAM-model of schizophrenia and the relaxation of airway smooth muscle have led to the study of SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 and related compounds bound within the α5-GABAA/BzR (Figure 29). The SH-053-R-CH3 (15) and SH-053-S-CH3 (16) isomers have been previously described [23]. These compounds along with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 and SH-053-2′F-S-CH3 have been tested for binding affinity and show selectivity for the α5-subunit (Table 3).

Figure 29.

Structures of enantiomers with 2′H (15, 16) and 2′F (2, 17).

Table 3.

Binding affinity at αxβ2γ2 GABAA receptor subtypes (values are reported in nM).

| Compounda | α1 | α2 | α3 | α4 | α5 | α6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH-053-R-CH3, (15) | 2026 | 2377 | 1183 | >5000 | 949.1 | >5000 |

| SH-053-S-CH3, (16) | 1666 | 1263 | 1249 | >5000 | 206.4 | >5000 |

| SH-053-2′F-R-CH3, (2) | 759.1 | 948.2 | 768.8 | >5000 | 95.17 | >5000 |

| SH-053-2′F-S-CH3, (17) | 350 | 141 | 1237 | >5000 | 19.2 | >5000 |

aData shown here are the means of two determinations which differed by less than 10%.

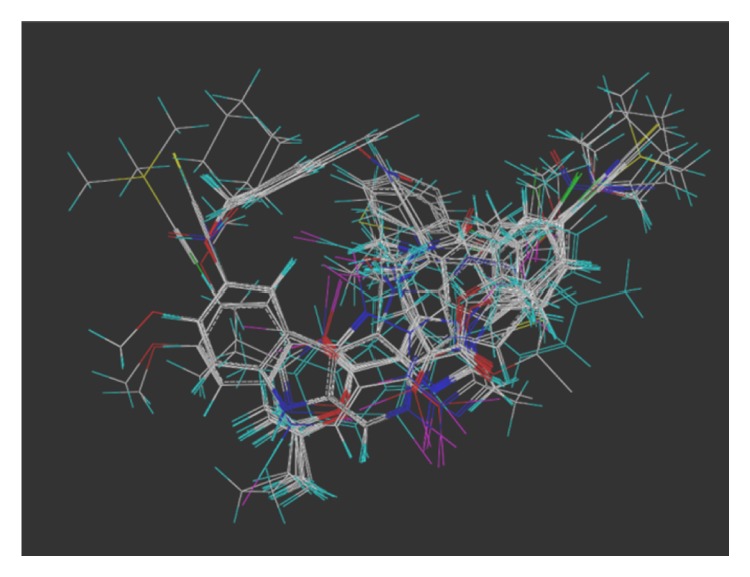

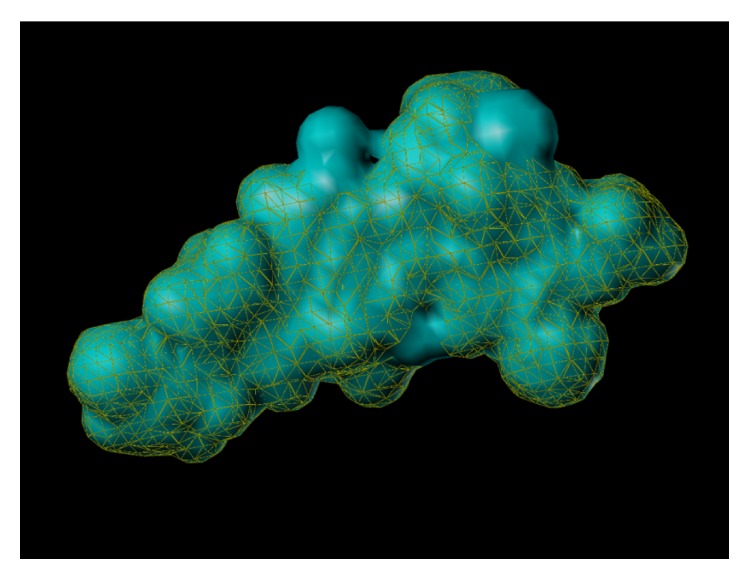

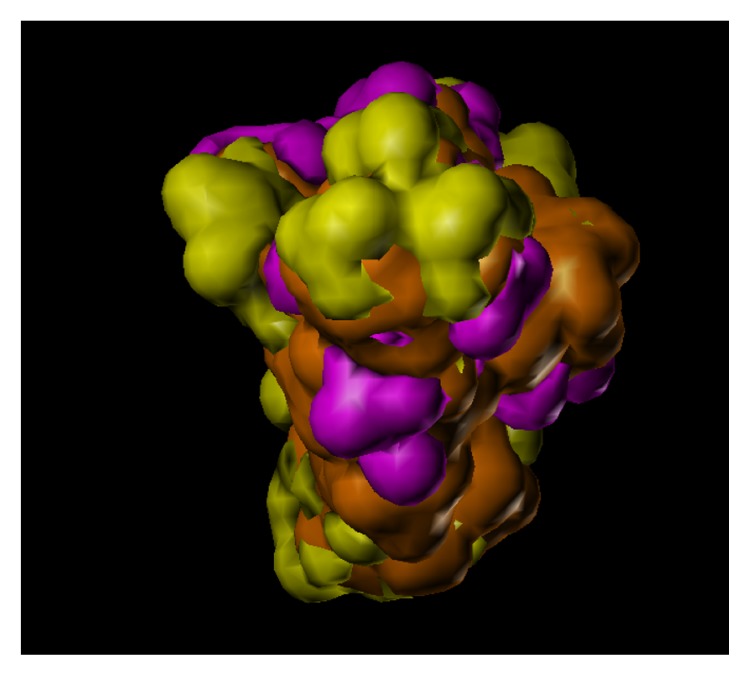

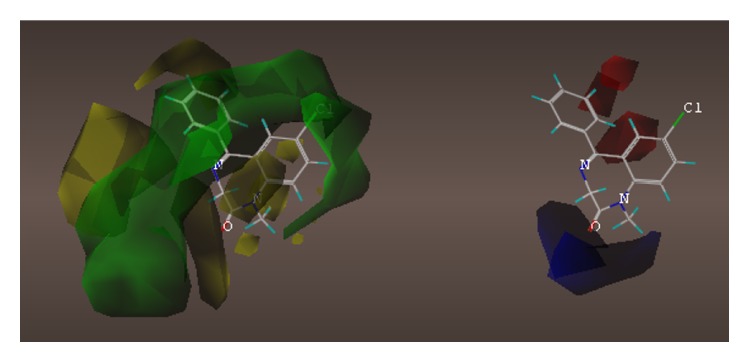

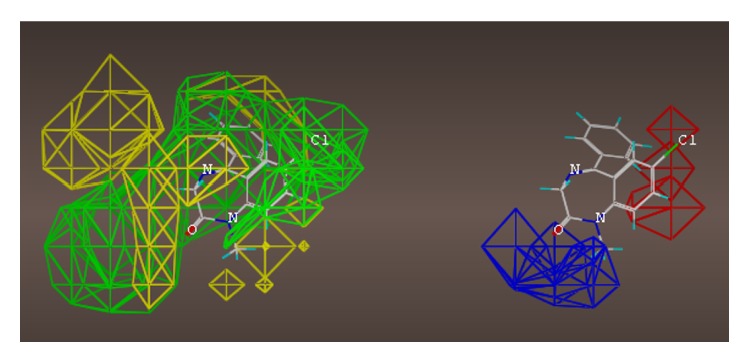

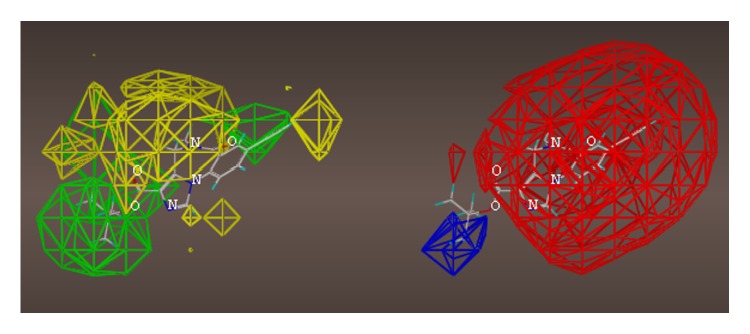

From examination of Figure 30 and Tables 3 and 4, it is clear the (R)-isomers bound to the α5 subtype while the (S)-isomers were selective for α2/α3/α5 subtypes.

Figure 30.

Included volume and ligand occupation of the SH-053-2′F-S-CH3 17 and SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 2 enantiomers in the α5 and γ2 pharmacophore/receptor models. This figure was modified and reproduced from that reported by Clayton et al. in [22, 23].

Table 4.

Oocyte electrophysiological data of benzodiazepinesa [87].

| Compound | α1 | α2 | α3 | α5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) | 111/154 | 124/185 | 125/220 | 183/387 |

| SH-053-2′F-S-CH3 (17) | 116/164 | 170/348 | 138/301 | 218/389 |

aEfficacy at αxβ3γ2 GABAA receptor subtypes as % of control current at 100 nM and 1 μM concentrations. Data presented as percent over baseline (100) at concentrations of 100 nM/1 μM.

From this data, these compounds were then used in examining the α5-binding pocket, most specifically the fluoroseries. In regard to molecular modeling, depicted in Figure 30 is the included volume and ligand occupation of the SH-053-2′F-S-CH3 (17) and SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 (2) enantiomers in the α5 subtype as well as the α2 subtype. It is clear a new pocket (L 4) has been located in the α5 subtype permitting 2 as well as 17 to bind to the α5 subtype. Examination of both ligands in the α2 subtype clearly illustrates the analogous region in the α2 subtype is not present and thus does not accommodate 2 for the pendant phenyl which lies outside the included volume in the space allocated for the receptor protein itself [23].

9. BzR GABA(A) Subtypes

In terms of potency, examination of the values in Table 4 [87], it is clear the R-isomer (2) shows more selectivity towards the α5-subunit, while the S-isomer (17) is potent at the α2/3/5 subunits. It is important, as postulated earlier [23], that the major difference in GABA(A)/Bz receptors subtypes stems from differences in asymmetry in the lipophilic pockets L 1, L 2, L 3, L 4, and L Di in the pharmacophore/receptor model and indicates even better functional selectivity is possible with asymmetric BzR ligands.

The synthetic switching of chirality at the C-4 position of imidazobenzodiazepines to induce subtype selectivity was successful. Moreover, increase of the potency of imidazobenzodiazepines can be achieved by substitution of the 2′-position hydrogen atom with an electron rich atom (fluorine) on the pendant phenyl ring in agreement with Haefely et al. [88], Fryer [89, 90], and our own work [22, 91]. The biological data on the two enantiomeric pairs of benzodiazepine ligands confirm the ataxic activity of BZ site agonists is mediated by α1β2/3γ2 subtypes, as reported in [23, 91–93]. The antianxiety activity in primates of the S isomers was preserved with no sedation. In only one study in rodents was any sedation observed; the confounding sedation was observed in both the S isomer (functionally selective for α2, α3, and α5 receptor subtypes) and R isomer (essentially selective for α5 subtype) and may involve at least, in part, agonist activity at α5 BzR subtypes. There are some α5 BzR located in the spinal cord which might be the source of the decrease in locomotion with SH-053-2′F-R-CH3 and SH-053-2′F-S-CH3; however, this is possibly some type of stereotypical behavior. Hence in agreement with many laboratories including our own [23, 92, 93] the best potential nonsedative, nonamnesic, antianxiety agents stem from ligands with agonist efficacy at α2 subtypes essentially silent at α1 and α5 subtypes (to avoid sedation) [91]. It must be pointed out again; however, in primates Fischer et al. [87] observed a potent anxiolytic effect with no sedation with the 2′F-S-CH3 (17) isomer, while the 2′F-R-CH3 (2) isomer exhibited only a very weak anxiolytic effect.

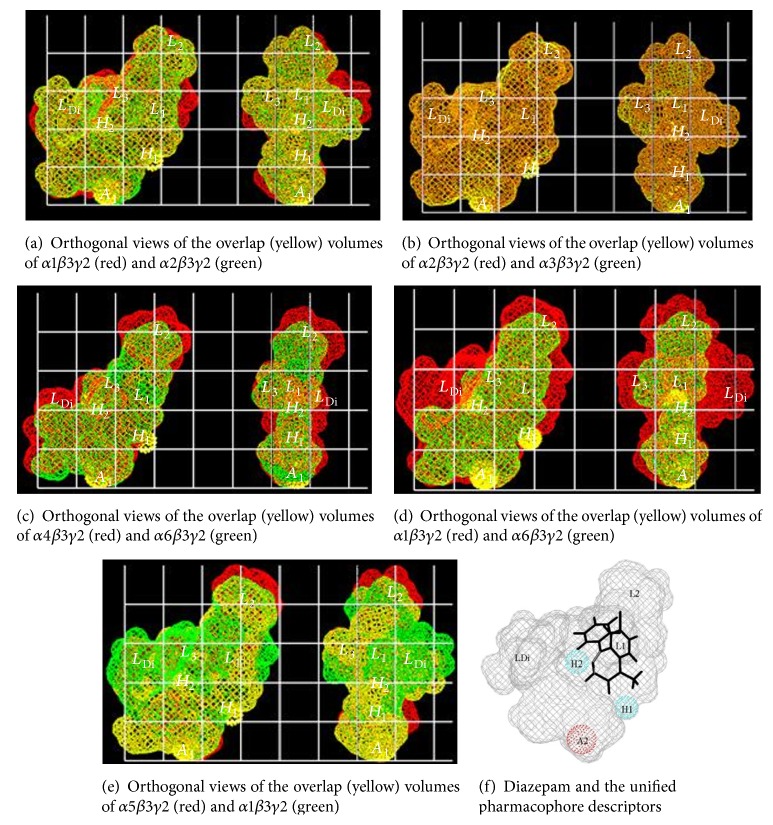

Numerous groups have done modeling and SAR studies on different classes of compounds which have resulted in a few different pharmacophore models based on the benzodiazepine binding site (BS) of the GABAA receptor [94]. These models are employed to gain insight in the interactions between the BS and the ligand. These have been put forth by Loew [7, 95, 96], Crippen [97, 98], Codding [76, 77, 99–101], Fryer [89, 90, 94], Gilli and Borea [102–105], Tebib et al. [106], and Gardner [107], as well as from Professors Sieghart, Cromer, and our own laboratory [21, 39, 40, 76, 78–82, 108–118].

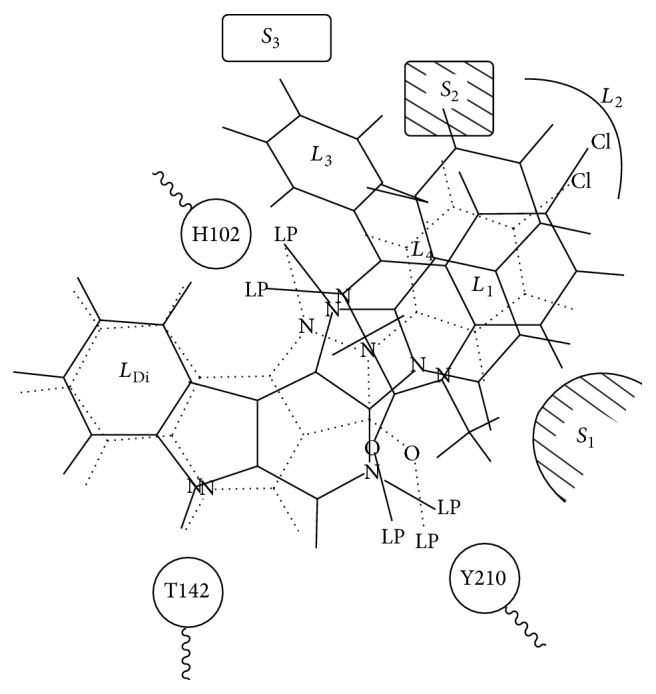

The Milwaukee-based pharmacophore/receptor model is a comprehensive building of the BzR using radioligand binding data and receptor mapping techniques based on 12 classes of compounds [20, 23, 39, 40, 42, 111, 119–122]. This model (Figure 31) [79] has brought together previous models which have used data from the activity of antagonists, positive allosteric modulators, and negative allosteric modulators and included the new models for the “diazepam-insensitive” (DI) sites [123]. Four basic anchor points, H 1, H 2, A 2, and L 1, were assigned, and 4 additional lipophilic regions were defined as L 2, L 3, L Di, and the new L 4 (see captions in Figure 31 for details); regions S 1, S 2, and S 3 represent negative areas of steric repulsion. As previously reported, the synthesis of both partial agonists and partial inverse agonists has been achieved by using parts of this model [99, 100, 104, 105, 119, 124–127].

Figure 31.

The two-dimensional representation of the Milwaukee-based unified pharmacophore with 3 amino acids in the binding site based on the rigid ligand template [23, 39, 42, 76–80]. This figure has been modified from that reported for PAMs, NAMs, and antagonists in [22, 23].

The cloning, expression, and anatomical localization of multiple GABA(A) subunits have facilitated both the identification and design of subtype selective ligands. With the availability of binding data from different recombinant receptor subtypes, affinities of ligands from many different structural classes of compounds have been evaluated.

Illustrated in Figure 31 is the [3,4-c]quinolin-3-one CGS-9896 (18) (dotted line), a diazadiindole (19) (thin line), and diazepam (20) (thick line) fitted initially to the inclusive pharmacophore model for the BzR. Sites H 1 (Y210) and H 2 (H102) represent hydrogen bond donor sites on the receptor protein complex while A 2 (T142) represents a hydrogen bond acceptor site necessary for potent inverse activity in vivo. L 1, L 2, L 3, L 4, and L Di are four lipophilic regions in the binding pharmacophore. Descriptors S 1, S 2, and S 3 are regions of negative steric repulsion.

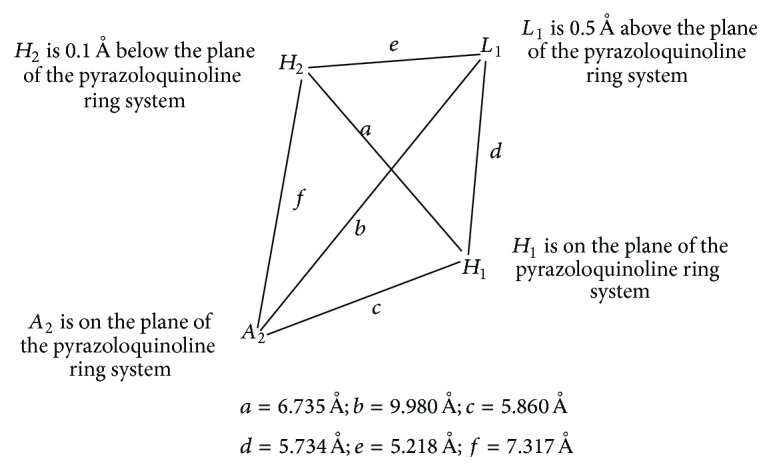

Based on SAR data obtained for these ligands at 6 recombinant BzR subtypes [128–132], an effort has been undertaken to establish different pharmacophore/receptor models for BzR subtypes. The alignment of the twelve different structural classes of benzodiazepine receptor ligands was earlier based on the least squares fitting of at least three points. The coordinates of the four anchor points (A 2, H 1, H 2, and L 1) employed in the alignment are outlined in Figure 32. Herein are described the results from ligand-mapping experiments at recombinant BzR subtypes of 1,4-benzodiazepines, imidazobenzodiazepines, β-carbolines, diindoles, pyrazoloquinolinones, and others [126]. Some of the differences and similarities among these subtypes can be gleaned from this study and serve as a guide for future drug design.

Figure 32.

The schematic representation of the descriptors for the initial inclusive BzR pharmacophore based on the rigid ligands (diindoles) [79, 81–84]. This figure has been modified from that reported in [79].

10. α1 Updates

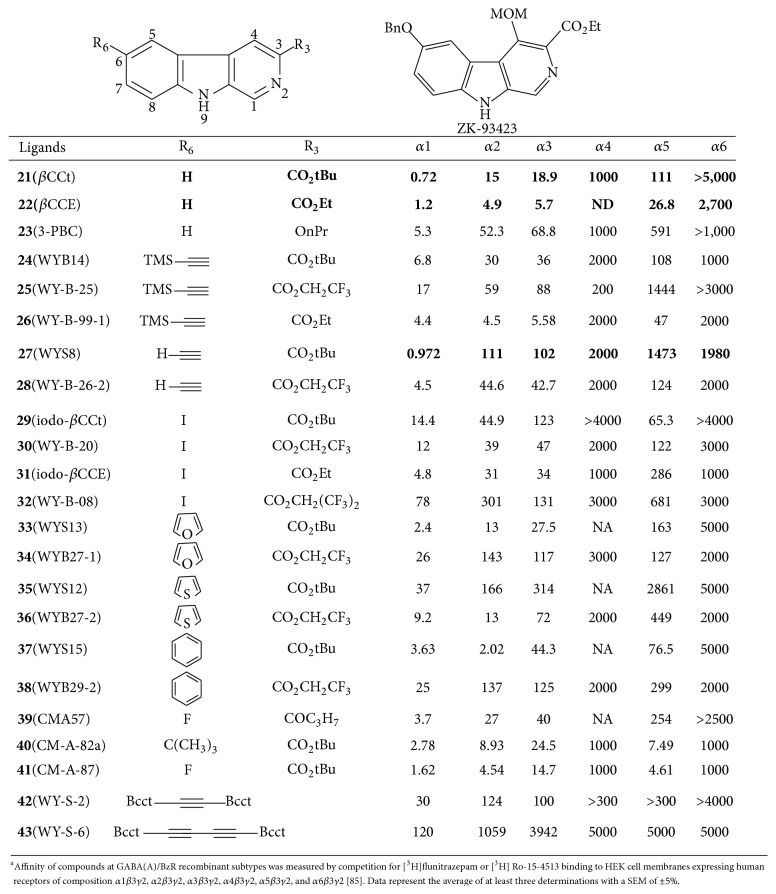

10.1. Beta-Carbolines

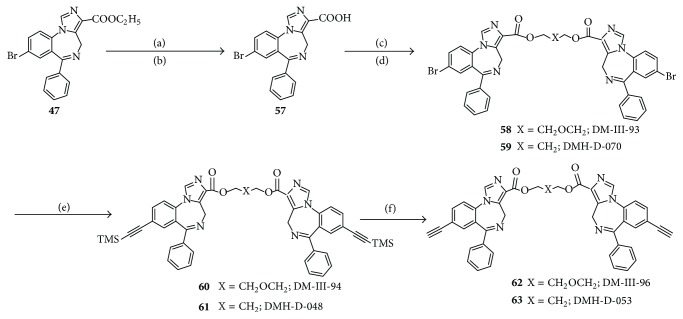

A series of 3,6-disubstituted β-carbolines was prepared and evaluated for their in vitro affinity at αxβ3γ2 GABA(A)/BzRr subtypes by radioligand binding assays in search of α1β3γ2 subtype selective compounds (Figure 33). A potential therapeutic application of such antagonist analogs is to treat alcohol abuse [133, 134]. Analogues of βCCt (21) were synthesized via a carbonyldiimidazole-mediated method by Yin et al. [85] and the related 6-substituted β-carboline-3-carboxylates including WYS8 (27) were synthesized from 6-iodo βCCt (29). Bivalent ligands (42 and 43) were also synthesized to increase the scope of the structure-activity relationships (SAR) to larger ligands. An initial SAR on the first analogs demonstrated that compounds with larger side-groups at C6 were well tolerated as they projected into the L Di domain (see 42 and 43) [85]. Moreover, substituents located at C3 exhibited a conserved stereo interaction in lipophilic pocket L 1, while N2 likely participated in hydrogen bonding with H 1. Three novel β-carboline ligands (21, 23, and 27) permitted a comparison of the pharmacological properties with a range of classical benzodiazepine receptor antagonists (flumazenil, ZK93426) from several structural groups and indicated these β-carbolines were “near GABA neutral antagonists.” Based on the SAR, the most potent (in vitro) α1 selective ligand was the 6-substituted acetylenyl βCCt (WYS8, 27). In a previous study both 21 and 23 were able to reduce the rate at which rats self-administrated alcohol in alcohol preferring and HAD rats but had little or no effect on sucrose self-administration [85]. 3-PBC (23) was also active in baboons [134]. This data has been used in updating the pharmacophore model in the α1-subtype.

Figure 33.

aAffinities (K i = nM) of 3,6-disubstituted β-carbolines at αxβ3γ2 (x = 1–3, 5, 6) receptor subtypes [85]. The structures versus code numbers of all ligands in the tables of this review can be found in the Ph.D. thesis of Terry Clayton (Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, December, 2011) [22] and in the Supporting Information.

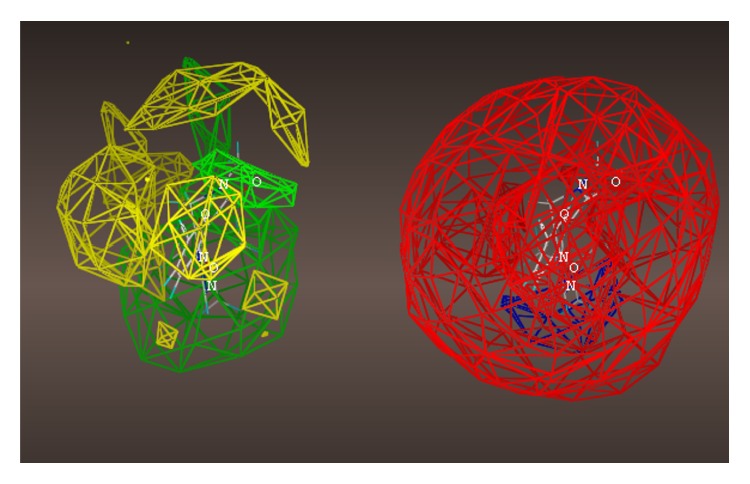

11. The Updated Included Volume Models

Illustrated in Figure 34 is the included volume of the updated pharmacophore receptor model of the α1β3γ2 subtype of Clayton [22]. The current model for the α1β3γ2 subtype has several new features. The cyclopropyl group of CD-214 extended 2 Å past the A 2 descriptor slightly increasing its volume. The trimethylsilyl group of QH-II-82 and WYS7 illustrates how well bulky groups are tolerated near the entrance of the binding pocket. Despite not being as potent, dimers of beta carbolines, WYS2 and WYS6, bound to α1 subtypes at 30 nM and 120 nM, respectively. Their ability to bind, albeit weakly, supports the location of the binding site entrance from the extracellular domain. The included volume of the α1β3γ2 subtype was previously 1085.7 cubic angstroms. The volume has now been measured as 1219.2 cubic angstroms. Volume measurements should be used carefully as the binding site is not enclosed and the theoretical opening near L DI is not clearly demarcated. Dimers were excluded from the included volume exercise because although they bound to the receptor, they represented compounds which were felt to extend outside the receptor binding pocket when docked to the protein. Where appropriate, their monomers were included in the included volume analysis. Ligands considered for the included volume in Table 5 exhibited potent binding at α1 subtypes (K i ≤ 20 nM) but were not necessarily subtype selective. The binding data for ligands at α 2–6-subtypes follow (Tables 6–10; structures located in Clayton [22] and Supporting Information, Appendix III in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/430248).

Figure 34.

Overlay of selected compounds for α1β3γ2 subtype from Table 5.

Table 5.

These ligands bound with potent affinity for α1; ligands bound with K i values <20 nM at this subtype.

| Cook codea | α1 | α2 | α3 | α4 | α5 | α6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WY-TSC-4 (WYS8) | 0.007 | 0.99 | 1.63 | 51.04 | ||

| SH-TSC-2 (BCCT) | 0.03 | 0.0419 | 0.035 | 69.32 | ||

| QH-II-090 (CGS-8216) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 17 | |

| XLI-286 | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.118 | 0.684 | ||

| QH-II-077 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 4 | |

| QH-II-092 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ND | 0.17 | ND |

| JYI-57 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.131 | ND | 0.036 | ND |

| QH-II-085 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 | ND | 0.08 | ND |

| XHE-II-024 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 14 | 0.24 | 11 |

| PWZ-007A | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.09 | ND | 0.2 | 10 |

| CGS8216 | 0.13 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 46 |

| SPH-121 | 0.14 | 1.19 | 1.72 | ND | 4 | 479 |

| QH-II-075 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.25 | ND | 1.3 | 40 |

| PZII-028 | 0.2 | ND | 0.2 | ND | 0.32 | 1.9 |

| CGS9895 | 0.21 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 9.3 |

| PWZ-0071 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.12 | ND | 0.44 | 17.31 |

| XHE-III-24 | 0.25 | ND | 8 | 222 | 10 | 328 |

| JYI-42 | 0.257 | 0.146 | 0.278 | ND | 0.256 | ND |

| CGS9896 | 0.28 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 181 |

| JYI-64 (C17H12N4FBr) | 0.305 | 1.111 | 0.62 | ND | 0.87 | 5000 |

| PZII-029 | 0.34 | ND | 0.79 | ND | 0.52 | 10 |

| BRETAZENIL | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.2 | ND | 0.5 | 12.7 |

| FG8205 | 0.4 | 2.08 | 1.16 | ND | 1.54 | 227 |

| YT-5 | 0.421 | 0.6034 | 36.06 | ND | 1.695 | ND |

| 6-PBC | 0.49 | 1.21 | 2.2 | ND | 2.39 | 1343 |

| QH-146 | 0.49 | ND | 0.76 | ND | 7.7 | 10000 |

| DM-II-90 (C17H12N4BrCl) | 0.505 | 1 | 0.63 | ND | 0.37 | 5000 |

| SPH-165 | 0.63 | 2.79 | 4.85 | ND | 10.4 | 1150 |

| BCCt | 0.72 | 15 | 18.9 | ND | 110.8 | 5000 |

| SH-I-048A | 0.774 | 0.1723 | 0.383 | ND | 0.11 | ND |

| alprazolam | 0.8 | 0.59 | 1.43 | ND | 1.54 | 10000 |

| Ro15-1788 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.05 | ND | 0.6 | 148 |

| WYS10 C14H9F3N2O2 | 0.88 | 36 | 25.6 | ND | 548.7 | 15.3 |

| WY-B-15 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 2080 | 4.42 | 646 |

| WY-A-99-2 (WYS8) | 0.972 | 111 | 102 | 2000 | 208 | 1980 |

| XHE-III-06a | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1.8 | 37 |

| Xli366 C22H21N3O2 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| JYI-59 (C22H13N3O2F4) | 1.08 | 2.6 | 11.82 | ND | 11.5 | 5000 |

| WYSC1 C16H16N2O2 | 1.094 | 5.44 | 12.3 | ND | 69.8 | 21.2 |

| MLT-I-70 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | ND | 40.3 | 1000 |

| SVO-8-30 | 1.1 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 15 |

| BCCE | 1.2 | 4.9 | 5.7 | ND | 26.8 | 2700 |

| XHE-III-04 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.1 | 219 | 0.4 | 500 |

| XLi350 C17H11ClN2O | 1.224 | 1.188 | ND | ND | 2.9 | ND |

| XHE-III-49 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 38.7 | 11.3 | 85.1 |

| PWZ-009A1 | 1.34 | 1.31 | 1.26 | ND | 0.84 | 2.03 |

| DM-239 | 1.5 | ND | 0.53 | ND | 0.14 | 6.89 |

| XLi351 C21H21ClN2OSi | 1.507 | 0.967 | ND | ND | 1.985 | ND |

| XLi352 C18H13ClN2O | 1.56 | 0.991 | ND | ND | 1.957 | ND |

| TG-4-39 | 1.6 | 34 | 24 | 5.6 | 1.4 | 23 |

| TG-II-82 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | ND | 1 | 1000 |

| CM-A87 | 1.62 | 4.54 | 14.73 | 1000 | 4.61 | 1000 |

| QH-II-082 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 | ND | 6.1 | 100 |

| JYI-49 (C20H12N3O2F4Br) | 1.87 | 2.38 | ND | ND | 6.7 | 3390 |

| LJD-III-15E | 1.93 | 14 | 19 | ND | 70.8 | 1000 |

| SPH-38 | 2 | 5.4 | 10.8 | ND | 18.5 | 3000 |

| XHE-I-093 | 2 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 1107 | 20 | 1162 |

| MSA-IV-35 | 2.1 | 16 | 21 | ND | 995 | 3000 |

| JYI-19 (C23H23N3O3S) | 2.176 | 205 | ND | ND | 34 | 12.7 |

| FLUNITRAZEPAM | 2.2 | 2.5 | 4.5 | ND | 2.1 | 2000 |

| YCT-5 | 2.2 | 11.46 | 16.3 | ND | 200 | 10000 |

| TJH-IV-51 | 2.39 | 17.4 | 14.5 | ND | 316 | 10000 |

| WYS13 C20H18N2O3 | 2.442 | 13 | 27.5 | ND | 163 | 5000 |

| YT-III-25 | 2.531 | 5.786 | 5.691 | ND | 0.095 | ND |

| XHE-III-14 | 2.6 | 10 | 13 | 2 | 7 | |

| WYS9 C16H15IN2O2 | 2.72 | 22.2 | 23.1 | ND | 562 | 122 |

| JYI-47 | 2.759 | 2.282 | 0.511 | ND | 0.427 | ND |

| CM-A82a | 2.78 | 8.93 | 24.51 | 1000 | 7.49 | 1000 |

| TG-4-29 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 0.18 | 3.9 |

| XLi268 C17H13BrN4 | 2.8145 | 0.6862 | ND | ND | 0.6243 | ND |

| JYI-54 (C24H15N3O3F4) | 2.89 | 172 | 6.7 | ND | 57 | 1890 |

| MMB-II-74 | 3 | 24.5 | 41.7 | 500 | 125.7 | 1000 |

| MMB-III-016 | 3 | 1.97 | 2 | 1074 | 0.26 | 211 |

| MMB-III-16 | 3 | 1.97 | 2 | 1074 | 0.26 | 211 |

| QH-II-080b | 3 | 3.7 | 4.7 | ND | 24 | 1000 |

| YCT-7A | 3 | 23.8 | 30.5 | ND | 240 | 10000 |

| JYI-32 (C20H15N3O2BrF) | 3.07 | 4.96 | ND | ND | 2.92 | 52.24 |

| Ro15-4513 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 2.5 | ND | 0.26 | 3.8 |

| XHE-II-017 | 3.3 | 10 | 7 | 258 | 17 | 294 |

| XLi-JY-DMH ANX3 | 3.3 | 0.58 | 1.9 | ND | 4.4 | 5000 |

| MLT-II-18 | 3.4 | 11.7 | 11 | ND | 225 | 10000 |

| TJH-V-88 | 3.41 | 30 | ND | 140.9 | 10000 | |

| XLI-2TC | 3.442 | 1.673 | 44.08 | ND | 1.121 | |

| WYS15 C22H20N2O2 | 3.63 | 2.02 | 44.3 | ND | 76.5 | 5000 |

| CM-A57 | 3.7 | 27 | 40 | ND | 254 | 1000 |

| XHE-II-006b | 3.7 | 15 | 12 | 1897 | 144 | 1000 |

| JYI-60 | 3.73 | 1.635 | 4.3 | ND | 1.7 | 5000 |

| RY-008 | 3.75 | 7.2 | 4.14 | ND | 1.11 | 44.3 |

| MLT-II-18 | 3.9 | 12.2 | 24.4 | ND | 210 | 10000 |

| OMB-18 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1733 | 0.8 | 5 |

| WY-B-09-1 | 3.99 | 8 | 32 | 1000 | 461 | 2000 |

| SHU-1-19 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 48 | 14 | 84 |

| ZK 93423 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 6 | ND | 4.5 | 1000 |

| WY-B-23-2 (WYS11) | 4.2 | 37.7 | 39 | 2000 | 176 | 69.4 |

| WY-B-23-2 (WYS11) | 4.2 | 37.7 | 73 | ND | 176 | 69.4 |

| WY-B-99-1 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.58 | 2000 | 47 | 2000 |

| WY-B-26-2 | 4.45 | 44.57 | 42.66 | 2000 | 124 | 2000 |

| XHE-II-006a | 4.7 | 4.4 | 20 | 1876 | 89 | 3531 |

| CM-B01 | 4.8 | 31 | 34 | 1000 | 286 | 1000 |

| PWZ-085 | 4.86 | 13 | 8.5 | ND | 0.55 | 40 |

| MLT-II-16 | 5.05 | 10.41 | 18.4 | ND | 260 | 10000 |

| 3 PBC | 5.3 | 52.3 | 68.8 | ND | 591 | 1000 |

| MA-3-PROPOXYL | 5.3 | 52.3 | 68.8 | ND | 591 | 1000 |

| TJH-IV-43 | 5.42 | 30.19 | 48.9 | ND | 475 | 10000 |

| DMCM | 5.69 | 8.29 | 4 | ND | 1.04 | 134 |

| DM-139 | 5.8 | ND | 169 | ND | 9.25 | 325 |

| XHE-II-073A (R ENRICHED) | 5.9 | 11 | 10 | 15 | 1.18 | 140 |

| MSR-I-032 | 6.2 | 18.7 | 4 | ND | 3.3 | 74.9 |

| JYI-70 (C19H13N4F) | 6.3 | 2.1 | ND | ND | 0.56 | 5000 |

| XLi343 C20H19ClN2OSi | 6.375 | 17.71 | ND | ND | 150.5 | ND |

| 3 EBC | 6.43 | 25.1 | 28.2 | ND | 826 | 1000 |

| DM-146 | 6.44 | ND | 148 | ND | 4.23 | 247 |

| DM-215 | 6.74 | ND | 7.42 | ND | 0.293 | 8.28 |

| ZG69A | 6.8 | 16.3 | 9.2 | ND | 0.85 | 54.6 |

| ZG-69a (Ro15-1310) | 6.8 | 16.3 | 9.2 | ND | 0.85 | 54.6 |

| WY-B-14 (WYS7) | 6.84 | 30 | 36 | 2000 | 108 | 1000 |

| YT-II | 6.932 | 0.8712 | 3.518 | ND | 5.119 | ND |

| SVO-8-67 | 7 | 41 | 26 | 15 | 2.3 | 191 |

| MLT-II-34 | 7.04 | 15.95 | 22.3 | ND | 158 | 1000 |

| SPH-195 | 7.2 | 168.5 | 283.5 | ND | 271 | 10000 |

| XHE-I-065 | 7.2 | 17 | 18 | 500 | 57 | 500 |

| ZG-234 | 7.25 | 22.14 | 9.84 | ND | 0.3 | 5.25 |

| SH-I-04 | 7.3 | 6.136 | 5.1 | ND | 7.664 | ND |

| XHE-I-038 | 7.3 | 5 | 34 | ND | 132 | 1000 |

| XHE-III-13 | 7.3 | ND | 7.1 | 880 | 1.6 | 311 |

| WY-B-25 | 7.6 | 40 | 66 | 2000 | 263 | 2000 |

| CM-A49 (R) | 7.7 | 32.5 | 43 | ND | 69 | 1000 |

| SVO-8-14 | 8 | 25 | 8 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 14 |

| TG-4-29 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 6.9 | ND | 0.4 | 7.61 |

| XHE-II-002 | 8.3 | 18 | 13 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 11 |

| WY-B-14 (WYS7) | 8.5 | 165 | 245 | ND | 1786 | 5000 |

| XHE-II-011 | 9 | 60 | 39 | 3233 | 90 | 1000 |

| WY-B-27-2 | 9.19 | 111 | 72 | 2000 | 449 | 2000 |

| QH-II-063 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 31 | ND | 7.7 | 3000 |

| JC184 C13H9BrN2OS | 9.606 | 10.5 | ND | ND | 6.709 | ND |

| ZG-208 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 10.9 | ND | 0.38 | 4.6 |

| RY-I-31 | 10 | 45 | 19 | ND | 6 | 1000 |

| WY-B-23-1 | 10 | 33 | 43 | 1000 | 189 | 2000 |

| RY-098 | 10.1 | 22.2 | 16.5 | ND | 1.68 | 100 |

| Hz148 C18H15N3 | 10.98 | 5000 | ND | ND | 256 | 5000 |

| SVO-8-20 | 11 | 40 | 28 | 19 | 8.6 | 138 |

| XHE-II-073B (S-ENRICHED) | 11 | 17 | 12 | 33 | 2.1 | 269 |

| SH-I-085 | 11.08 | 4.866 | 13.75 | ND | 0.24 | ND |

| PWZ-096 | 11.1 | 36 | 16.9 | ND | 1.07 | 51.5 |

| ZG-168 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 9.2 | ND | 0.47 | 9.4 |

| CM-A77 | 11.51 | 51.9 | 105.16 | 1000 | 42.62 | 1000 |

| WY-B-20 | 12 | 39 | 47 | 2000 | 122 | 3000 |

| ABECARNIL | 12.4 | 15.3 | 7.5 | ND | 6 | 1000 |

| SH-I-89S | 12.78 | 8.562 | 8.145 | ND | 3.23 | ND |

| ZG-213 | 12.8 | 49.8 | 30.2 | ND | 3.5 | 22.5 |

| EDC-I-071 | 12.9 | 83.1 | ND | ND | 314 | 5000 |

| MMB-III-14 | 13 | 13 | 6.9 | 333 | 1.1 | 333 |

| DM-173 | 13.1 | ND | 38.1 | ND | 0.78 | 118 |

| XLI-348 | 13.56 | 11.17 | 1.578 | ND | 82.05 | ND |

| EDC-I-093 | 13.6 | 423 | ND | ND | 2912 | 5000 |

| diazepam | 14 | 20 | 15 | ND | 11 | ND |

| XLi223 C22H20BrN3O2 | 14 | 8.7 | 18 | 1000 | 10 | 2000 |

| WYSC2 C15H11F3N2O2 | 14.14 | 113 | 170 | ND | 518 | 61.2 |

| SH-I-030 | 14.42 | 11.04 | 19.09 | ND | 1.89 | ND |

| CM-A100 | 14.49 | 44.91 | 123.8 | 1000 | 65.31 | 1000 |

| RY-033 | 14.8 | 56 | 25.3 | ND | 1.72 | 22.9 |

| HJ-I-037 | 15.07 | 8.127 | 28.29 | ND | 0.818 | ND |

| YT-6 | 15.31 | 87.8 | 60.49 | ND | 1.039 | ND |

| EDC-II-044 | 15.4 | ND | 293 | ND | 323 | 1000 |

| CM-A58 | 16 | 120 | 184 | ND | 1000 | 1012 |

| QH-II-067a | 16 | 31 | 52 | ND | 199 | 3000 |

| CD-214 | 16.4 | 48.2 | 42.5 | ND | 9.8 | 168 |

| JYI-06 (C23H23N3O4) | 16.5 | 5.48 | 5000 | ND | 12.6 | 5000 |

| CM-A50 (S) | 17 | 59 | 88 | ND | 144 | 1000 |

| RY-061 | 17 | 13 | 6.7 | ND | 0.3 | 31 |

| ZG-224 | 17.1 | 33.7 | 50 | ND | 2.5 | 30.7 |

| ZG-63A | 17.3 | 21.6 | 29.1 | ND | 0.65 | 4 |

| DM-II-30 (C20H13N3O2BrF3) | 17.6 | 13.4 | 28.51 | ND | 7.8 | 5000 |

| CM-A64 | 18 | 60 | 116 | ND | 216 | 1000 |

| RY-071 | 19 | 56 | 91 | ND | 7.2 | 266 |

| WZ-113 | 19.2 | 13.2 | 13.4 | ND | 11.5 | 300 |

| YT-III-23 | 19.83 | 23.65 | 19.87 | ND | 1.105 | ND |

| CM-E09b | 20 | 22 | 19 | 55 | 0.45 | 69 |

| MMB-II-90 | 20 | 24 | 5.7 | 9 | 0.25 | 36 |

aAffinity of compounds at GABAA/BzR recombinant subtypes was measured by competition for [3H]flunitrazepam or [3H] Ro15-4513 binding to HEK cell membranes expressing human receptors of compositions α1β3γ2, α2β3γ2, α3β3γ2, α4β3γ2, α5β3γ2, and α6β3γ2 [139]. Data represent the average of at least three determinations with a SEM of ±5%. The structures of these ligands are in the Ph.D. thesis of Clayton (2011) [22] and Supporting Information.

Table 6.

Ligands with potent affinity for α2; ligands bound with K i values <20 nM at this subtype. The structures of these ligands are in the Ph.D. thesis of Clayton (2011) [22].

| Cook codea | α1 | α2 | α3 | α4 | α5 | α6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QH-II-092 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ND | 0.17 | ND |

| SH-TSC-2 (BCCT) | 0.03 | 0.0419 | 0.035 | ND | 69.32 | ND |

| QH-II-085 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 | ND | 0.08 | ND |

| XLI-286 | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.118 | ND | 0.684 | ND |

| JYI-57 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.131 | ND | 0.036 | ND |

| QH-II-090 (CGS-8216) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ND | 0.25 | 17 |

| QH-II-077 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | ND | 0.12 | 4 |

| PWZ-007A | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.09 | ND | 0.2 | 10 |

| JYI-42 | 0.257 | 0.146 | 0.278 | ND | 0.256 | ND |

| PWZ-0071 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.12 | ND | 0.44 | 17.31 |

| SH-I-048A | 0.774 | 0.1723 | 0.383 | ND | 0.11 | ND |

| XHE-II-024 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 14 | 0.24 | 11 |

| QH-II-075 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.25 | ND | 1.3 | 40 |

| XLi-JY-DMH ANX3 | 3.3 | 0.58 | 1.9 | ND | 4.4 | 5000 |

| alprazolam | 0.8 | 0.59 | 1.43 | ND | 1.54 | 10000 |

| YT-5 | 0.421 | 0.6034 | 36.06 | ND | 1.695 | ND |

| BRETAZENIL | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.2 | ND | 0.5 | 12.7 |

| XLi268 C17H13BrN4 | 2.8145 | 0.6862 | ND | ND | 0.6243 | ND |

| WY-B-15 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 2080 | 4.42 | 646 |

| YT-II | 6.932 | 0.8712 | 3.518 | ND | 5.119 | |

| Ro15-1788 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.05 | ND | 0.6 | 148 |

| XLi351 C21H21ClN2OSi | 1.507 | 0.967 | ND | ND | 1.985 | ND |

| WY-TSC-4 (WYS8) | 0.007 | 0.99 | 1.63 | ND | 51.04 | ND |

| XLi352 C18H13ClN2O | 1.56 | 0.991 | ND | ND | 1.957 | ND |

| DM-II-90 (C17H12N4BrCl) | 0.505 | 1 | 0.63 | ND | 0.37 | 5000 |

| JYI-64 (C17H12N4FBr) | 0.305 | 1.111 | 0.62 | ND | 0.87 | 5000 |

| XLi350 C17H11ClN2O | 1.224 | 1.188 | ND | ND | 2.9 | ND |

| SPH-121 | 0.14 | 1.19 | 1.72 | ND | 4 | 479 |

| MLT-I-70 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | ND | 40.3 | 1000 |

| OMB-18 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1733 | 0.8 | 5 |

| 6-PBC | 0.49 | 1.21 | 2.2 | ND | 2.39 | 1343 |

| YT-III-271 | 32.54 | 1.26 | 2.35 | ND | 103 | ND |

| PWZ-009A1 | 1.34 | 1.31 | 1.26 | ND | 0.84 | 2.03 |

| DM-II-72 (C15H10N20BrCl) | 5000 | 1.37 | ND | ND | 2.02 | 5000 |

| JYI-60 (C17H11N2OF) | 3.73 | 1.635 | 4.3 | ND | 1.7 | 5000 |

| XLI-2TC | 3.442 | 1.673 | 44.08 | ND | 1.121 | ND |

| QH-II-082 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 | ND | 6.1 | 100 |

| TC-YT-II-76 | 101.1 | 1.897 | 5.816 | ND | 11.99 | ND |

| MMB-III-016 | 3 | 1.97 | 2 | 1074 | 0.26 | 211 |

| MMB-III-16 | 3 | 1.97 | 2 | 1074 | 0.26 | 211 |

| XHE-III-06a | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1.8 | 37 |

| XHE-III-04 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.1 | 219 | 0.4 | 500 |

| WYS15 C22H20N2O2 | 3.63 | 2.02 | 44.3 | ND | 76.5 | 5000 |

| FG8205 | 0.4 | 2.08 | 1.16 | ND | 1.54 | 227 |

| JYI-70 (C19H13N4F) | 6.3 | 2.1 | ND | ND | 0.56 | 5000 |

| JYI-47 | 2.759 | 2.282 | 0.511 | ND | 0.427 | ND |

| JYI-49 (C20H12N3O2F4Br) | 1.87 | 2.38 | ND | ND | 6.7 | 3390 |

| FLUNITRAZEPAM | 2.2 | 2.5 | 4.5 | ND | 2.1 | 2000 |

| JYI-59 (C22H13N3O2F4) | 1.08 | 2.6 | 11.82 | ND | 11.5 | 5000 |

| Ro15-4513 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 2.5 | ND | 0.26 | 3.8 |

| SPH-165 | 0.63 | 2.79 | 4.85 | ND | 10.4 | 1150 |

| YT-II-76 | 95.34 | 2.797 | 0.056 | ND | 0.04 | ND |

| TG-II-82 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | ND | 1 | 1000 |

| QH-II-080b | 3 | 3.7 | 4.7 | ND | 24 | 1000 |

| TG-4-29 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 0.18 | 3.9 |

| PS-1-34B C20H17N4BrO | ND | 4.198 | 3.928 | ND | ND | ND |

| ZK 93423 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 6 | ND | 4.5 | 1000 |

| XHE-II-006a | 4.7 | 4.4 | 20 | 1876 | 89 | 3531 |

| WY-B-99-1 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.58 | 2000 | 47 | 2000 |

| CM-A87 | 1.62 | 4.54 | 14.73 | 1000 | 4.61 | 1000 |

| OMB-19 | 22 | 4.6 | 20 | 3333 | 3.5 | 40 |

| SH-I-085 | 11.08 | 4.866 | 13.75 | ND | 0.24 | ND |

| BCCE | 1.2 | 4.9 | 5.7 | ND | 26.8 | 2700 |

| JYI-32 (C20H15N3O2BrF) | 3.07 | 4.96 | ND | ND | 2.92 | 52.24 |

| XHE-I-038 | 7.3 | 5 | 34 | ND | 132 | 1000 |

| SVO-8-30 | 1.1 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 15 |

| SPH-38 | 2 | 5.4 | 10.8 | ND | 18.5 | 3000 |

| WYSC1 C16H16N2O2 | 1.094 | 5.44 | 12.3 | ND | 69.8 | 21.2 |

| JYI-06 (C23H23N3O4) | 16.5 | 5.48 | 5000 | ND | 12.6 | 5000 |

| XHE-III-49 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 38.7 | 11.3 | 85.1 |

| YT-III-25 | 2.531 | 5.786 | 5.691 | ND | 0.095 | ND |

| SH-I-04 | 7.3 | 6.136 | 5.1 | ND | 7.664 | ND |

| XHE-I-093 | 2 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 1107 | 20 | 1162 |

| RY-008 | 3.75 | 7.2 | 4.14 | ND | 1.11 | 44.3 |

| DMH-D-053 (C43H30N6O4) | 236 | 7.4 | 272 | 5000 | 194.2 | 5000 |

| WY-B-09-1 | 3.99 | 8 | 32 | 1000 | 461 | 2000 |

| HJ-I-037 | 15.07 | 8.127 | 28.29 | ND | 0.818 | ND |

| DMCM | 5.69 | 8.29 | 4 | ND | 1.04 | 134 |

| SH-I-89S | 12.78 | 8.562 | 8.145 | ND | 3.23 | ND |

| XLi223 C22H20BrN3O2 | 14 | 8.7 | 18 | 1000 | 10 | 2000 |

| CM-A82a | 2.78 | 8.93 | 24.51 | 1000 | 7.49 | 1000 |

| QH-II-063 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 31 | ND | 7.7 | 3000 |

| 9.4 | 9.3 | 31 | ND | 7.7 | 3000 | |

| XHE-II-017 | 3.3 | 10 | 7 | 258 | 17 | 294 |

| TG-4-29 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 6.9 | ND | 0.4 | 7.61 |

| MLT-II-16 | 5.05 | 10.41 | 18.4 | ND | 260 | 10000 |

| JC184 C13H9BrN2OS | 9.606 | 10.5 | ND | ND | 6.709 | ND |

| ZG-168 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 9.2 | ND | 0.47 | 9.4 |

| XHE-II-073A (R ENRICHED) | 5.9 | 11 | 10 | 15 | 1.18 | 140 |

| XLI-8TC | 21.52 | 11.01 | 2.155 | ND | 4.059 | ND |

| SH-I-030 | 14.42 | 11.04 | 19.09 | ND | 1.89 | ND |

| XLI-348 | 13.56 | 11.17 | 1.578 | ND | 82.05 | ND |

| ZG-208 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 10.9 | ND | 0.38 | 4.6 |

| YT-TC-3 | 141.4 | 11.43 | 118.1 | ND | 29.22 | ND |

| YCT-5 | 2.2 | 11.46 | 16.3 | ND | 200 | 10000 |

| MLT-II-18 | 3.4 | 11.7 | 11 | ND | 225 | 10000 |

| XHE-II-O53-ACID | 50.35 | 11.8 | 44 | ND | 5.9 | 5000 |

| SHU-1-19 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 48 | 14 | 84 |

| RY-067 | 21 | 12 | 10 | ND | 0.37 | 42 |

| DM-III-01 (C18H12N3O2Br) | 5000 | 12 | ND | ND | 4.73 | 5000 |

| MLT-II-18 | 3.9 | 12.2 | 24.4 | ND | 210 | 10000 |

| SH-053-2′F | 21.99 | 12.34 | 34.9 | ND | 0.671 | ND |

| WYS13 C20H18N2O3 | 2.442 | 13 | 27.5 | ND | 163 | 5000 |

| PWZ-085 | 4.86 | 13 | 8.5 | ND | 0.55 | 40 |

| MMB-III-14 | 13 | 13 | 6.9 | 333 | 1.1 | 333 |

| RY-061 | 17 | 13 | 6.7 | ND | 0.3 | 31 |

| WZ-113 | 19.2 | 13.2 | 13.4 | ND | 11.5 | 300 |

| YT-II-83 | 32.74 | 13.22 | 24.1 | ND | 3.548 | ND |

| DM-II-30 (C20H13N3O2BrF3) | 17.6 | 13.4 | 28.51 | ND | 7.8 | 5000 |

| LJD-III-15E | 1.93 | 14 | 19 | ND | 70.8 | 1000 |

| YT-III-272 | 295.9 | 14.98 | 10.77 | ND | 103.3 | ND |

| BCCt | 0.72 | 15 | 18.9 | ND | 110.8 | 5000 |

| XHE-II-006b | 3.7 | 15 | 12 | 1897 | 144 | 1000 |

| ABECARNIL | 12.4 | 15.3 | 7.5 | ND | 6 | 1000 |

| MLT-II-34 | 7.04 | 15.95 | 22.3 | ND | 158 | 1000 |

| MSA-IV-35 | 2.1 | 16 | 21 | ND | 995 | 3000 |

| JYI-04 (C21H23N3O3) | 28.3 | 16 | ND | ND | 0.51 | 1.57 |

| PS-1-35 C23H22N5OBr | ND | 16.03 | 24.41 | ND | ND | ND |

| ZG69A | 6.8 | 16.3 | 9.2 | ND | 0.85 | 54.6 |

| ZG-69a (Ro15-1310) | 6.8 | 16.3 | 9.2 | ND | 0.85 | 54.6 |

| YT-III-42 | 382.9 | 16.83 | 44.04 | ND | 9.77 | ND |

| XHE-I-065 | 7.2 | 17 | 18 | 500 | 57 | 500 |

| XHE-II-073B (S-ENRICHED) | 11 | 17 | 12 | 33 | 2.1 | 269 |

| TJH-IV-51 | 2.39 | 17.4 | 14.5 | ND | 316 | 10000 |

| SH-I-047 | 1710 | 17.52 | 1222 | ND | 1519 | ND |