Stroke disparities are wide spread and pervasive throughout the world. In this review we will examine the effect of socio-economic status, race and ethnicity on stroke incidence and outcome. There are two main reasons that should compel us to fix the damage caused by stroke disparities. The first is based on the justice principle: no person or group should suffer more than others. While this reason should be a sufficient motivator, another incentive to remedy stroke disparities is the tremendous expense that disparities impose on society. Since minority populations have stroke at younger ages and are often more severe; the cost is far greater per capita then in majority populations1. We will look at opportunities to improve stroke prevention and stroke preparedness (recognizing stroke and alerting emergency medical services) in underserved populations towards remedying stroke disparities. Table 1 provides a summary of the potential intervention targets discussed in this paper.

Table 1.

Potential intervention targets and timing to reduce stroke disparities in developed and developing countries discussed in this article.

| Developed Countries | Developing Countries | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention | ||

| Improved health literacy | Now | Now |

| Hypertension Control | ||

| Tobacco cessation | Now | Now |

| Weight control & Diet | Now | Now |

| Exercise | Now | Now |

| Low-cost medication | Now | Now |

| Lipid control | Now | Now |

| Anti-platelet/anti-coagulant | Now | Now |

| Community focus | Now | Now |

| Genetic tailored focus | Future | Future |

| Preparedness | ||

| Public awareness | Now | Now |

| Health team readiness | Now | Now |

| Acute Treatment | ||

| Intravenous rt-PA | Now | In many locations |

| Catheter intervention | Now | Future |

| Rehabilitation | Now | Now |

Much of the work in this area is centered in the United States (U.S.). However, there are important data emerging from international locations. Indeed the epidemiologic transition, the change from infection and trauma to chronic diseases as major causes of death and disability in the developing world, speaks directly to the need for prevention and preparedness in the poorest parts of the globe. Paradoxically, increases in stroke risk and mortality in developing countries are associated with increasing socio-economic status (SES), but decreases in stroke risk and mortality in developed countries are associated with increasing SES2. In rural villages in China, higher incomes brought prosperity but also brought higher stroke risk3. It is likely that when new monies enter a previously impoverished area that certain unhealthful behaviors are initially adopted. These may include increased consumption of meat and sugar rich foods, as well as using motorized transport rather than walking. With increased health literacy, the economic advantage is put to good use with improved diet, exercise and access to medical prevention and treatment. A key goal will be to help developing countries control increasing stroke risk and obtain the same health benefits with prosperity seen in the West.

Non-U.S. Disparities

Prevention

Studies in non-U.S. developed countries show greater stroke risk and worse outcome in ethnic minority populations compared to those with European origin populations4–6. Efforts to prevent stroke in developing countries and in disadvantaged areas of developed countries have focused mainly on primary prevention. Since the largest population attributable stroke risk factor is hypertension it has become the most important target for stroke prevention. Hypertension is a formidable foe. It often does not cause pain or obvious stigmata until stroke, heart, kidney and/or eye disease are already quite advanced. It is, however, readily treatable with behavior modification (smoking cessation, weight control, diet, aerobic exercise) and low-cost pharmacotherapy.

The Nigerian anti-hypertensive adherence trial was a randomized population-based study. Hypertensive individuals (N=544) were randomized to receive nurse led clinic visits and home visits compared with just clinic visits. At baseline mean blood pressures of enrollees was 168/92. Diet and exercise interventions as well as low cost medication (thiazide diuretic +/− a beta blocker) were used. At six months, 77% had stayed in the study and 98% of these were compliant with the program. At six months 2/3 of the subjects in both arms of the study had blood pressure controlled <140/90; a phenomenal success for a low cost, low resource intervention7.

A second study conducted in China and Nigeria further illustrates how successful targeted risk factor reduction programs can be. The study enrolled 60 hypertensive patients at 10 pairs of primary care facilities and randomized the pairs to educational intervention (behavioral risk factor reduction and medication as needed) and control. There was significant reductions in blood pressure in the intervention compared with the control group. Interestingly the control group also showed significant blood pressure declines suggesting that participating in a clinical trial in the developing world may be beneficial by itself8.

The South London Stroke registry found a 75% increased chance of poor outcome among the lowest SES group compared with the highest after controlling for clinical variables including stroke severity9. The potent effect of SES on stroke outcomes suggests a tremendous need for improved resources for those recovering from stroke.

Preparedness

We have been unable to find evidence regarding stroke preparedness directed specifically at minority populations in the developing world. Indeed a recent systematic review of stroke preparedness for minority populations found 15 studies, all done in the U.S.10. This may, in part, be due to the expense associated with both intravenous thrombolysis and acute stroke intervention. Still, there is ample evidence that early presentation and expert acute stroke care improve stroke outcome even without thrombolysis and intervention11. While a lofty goal may be the spread of thrombolysis and intervention globally, it remains clearly important to advocate worldwide rapid presentation to a hospital equipped with the personnel and necessary equipment to properly manage fluid status, blood pressure and prevent stroke complications.

U.S. Disparities

Prevention

Epidemiologic studies in the U.S. show that race/ethnic minorities have a higher stroke risk and worse outcome than non-Hispanic whites12–14. Stroke risk in African Americans has varied by age, with highest risk in younger age groups and less disparity at older ages15–17. In a similar fashion, Mexican Americans had a higher cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke at younger ages with similar incidence rates in older age groups18. In studies with longitudinal data the stroke incidence rates for non-Hispanic whites has been decreasing19, 20 while incidence rates for race/ethnic minorities have not20, 21.

In clinical trials of recurrent stroke performed over the past 50 years, annual stroke recurrence rates have declined from 6.1% in the 1960’s to 5.0% in the 2000s. Following the linear trend, the stroke rate in the control group of secondary prevention trials over the next 10 years is projected to be as low as 2.3%22. This speaks to improvements in the optimal or “control” regimen for secondary stroke prevention. While hard to strictly implement such regimens outside of the rigorous environment of a clinical trial, recurrent stroke rates have declined in the broader U.S. population as well. Among elderly Medicare beneficiaries, recurrent stroke rates declined by almost 5% between 1994 and 200223. These results speak to the potential for multi-factorial risk-factor reduction including anti-platelets, anti-hypertensives, lipid lowering agents and behavior change in reducing the risk for stroke when systematically applied24, 25.

Regarding primary prevention, significant racial disparities have been noted in major stroke risk factors such as hypertension, even after controlling for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and for medication adherence26. Risk factor awareness has been consistently found to be lower in race/ethnic minority groups27. However, in one study African Americans were 30% more likely to be aware of their hypertension than whites, and when aware, were 70% more likely to be treated than whites, but still less likely to have adequate blood pressure control28. A recently reported primary prevention trial found significant improvement in behavioral risk factors for hypertension after a Catholic Church-based educational intervention aimed at Mexican Americans and non Hispanic whites. This study of 801 community residents found significant increases in fruit and vegetable intake and in sodium reduction, meeting its primary, pre-specified endpoint29.

In the future, targeted prevention strategies may emanate from specific genetic predispositions for stroke risk. Indeed, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have already yielded clues for genetic stroke risk in minority populations30.

In summary, the potential effectiveness of primary and secondary prevention in the U.S. is limited by the complex interwoven issues of adherence and compliance, inability to afford medications, unequal access to medical care, mistrust, low medical literacy, and medication side effects. These issues are more pronounced in race/ethnic minority groups31. It is of paramount importance to recognize that inefficiencies and inequalities in the healthcare system drive these issues, and that we should not blame the victims but rather look in the mirror for solutions. A possible solution to at least some of these issues is found in the Affordable Care Act which provides low cost health insurance to those in the U.S. and widens access for the poor to Federally Qualified Health Centers who provide guideline concordant vascular disease prevention32. Another key component to finding stroke treatments for minority population is the need to recruit minority populations into stroke clinical trials. A recent paper suggests specific key steps to improve minority recruitment that includes having the budget to perform outreach, using standard, practiced and culturally competent recruitment strategies, and the crucial role of partnering with the community33.

Preparedness

Studies of knowledge among US citizens vary widely in results obtained. In the best case results from the National Health Interview Survey in 2009, 51% of subjects were aware of 5 stroke warning symptoms and also knew to call 911 to seek treatment. In this study, female sex and higher level of education were associated with greater knowledge, and whites had higher awareness than race/ethnic minorities (the percent who were aware of all 5 stroke warning symptoms and would call 911 was 56% for whites, 47% for blacks, and 37% for Hispanics)34. In another study, only 3.6% of those surveyed could identify that acute stroke therapy existed35. The latter case demonstrates that preparedness is still lacking, and further educational efforts are needed. There have been some large studies aimed at improving stroke preparedness in minority populations. While a systematic review found that the effectiveness of interventions designed to promote stroke awareness in race/ethnic minority groups was considered inconclusive due to mixed results and design limitations, there have been some successes including four randomized clinical trials10. In one study, predominantly Mexican American middle school children received an intensive educational intervention aimed at stroke recognition and motivation to call 911. Students randomized to intervention compared with control were more knowledgeable about stroke and had more intent to call 911 for witnessed stroke36. Another impressive, on-going effort combines culturally appropriate music to teach African American elementary school students about stroke. Early reports on Hip-Hop Stroke suggest both engagement of the students and potential effectiveness of the intervention37.

Toward an Approach to Reducing Disparities

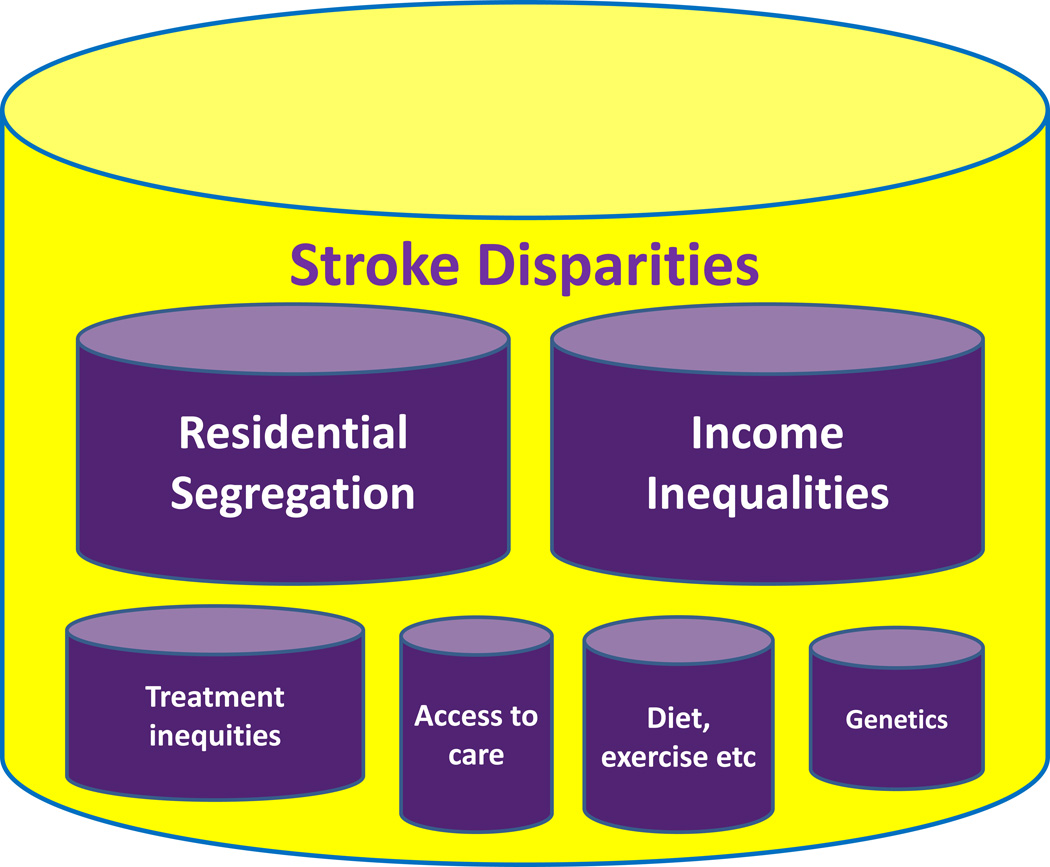

Approaches to remedying health disparities may fundamentally consider one of two approaches. The first is health equity; the implication being that if we really treat everyone equally that health outcomes will be equal across race/ethic and SES groups. This concept is fundamentally grounded in civil rights approaches to housing, health and other social factors. It has been more than a decade since the Institute of Medicine chronicled the poor quality of care given to minority populations in the United States38. It is absolutely crucial that we strive for health equity, and recent reports in other disciplines suggest that improved health equity reduces disparities and improves outcomes39. However, the problem is that disparities exist for a variety of reasons, only one of which is unequal treatment. As Figure 1 shows, health equity is likely just one of the many components that influence health and therefore stroke disparities. The second approach therefore is one that strives for health equity and also targets underserved populations for specific prevention and preparedness activities to actively reduce disparities. Evidence from other disciplines supports this approach and suggests the need for a multi-component and multi-level approach to reducing health disparities40.

Figure 1.

Potential contributors to stroke disparities.

Summary and recommendation

Stroke disparities are a ubiquitous problem facing populations around the world. Most research in documenting and remedying stroke disparities is from the U.S. but the epidemiologic transition argues for a far greater effort in developing countries. Regardless of the location, everyone in health care can make a difference on the individual patient, health system and community level. Working with individual patients to identify personal barriers to stroke prevention; improving health equity in health systems; and organizing communities to provide preventive resources and motivation to activate emergency medical systems in acute stroke are likely to have high yield in reducing stroke disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOURCES OF FUNDING

NIH R01 NS38916, R21 NS086144, R21 NS084081, R01 NS30678, U01 NS41588

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURE

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown DL, Boden-Albala B, Langa KM, Lisabeth LD, Fair M, Smith MA, et al. Projected costs of ischemic stroke in the United States. Neurology. 2006;67:1390–1395. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237024.16438.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu SH, Woo J, Zhang XH. Worldwide socioeconomic status and stroke mortality: An ecological study. International journal for equity in health. 2013;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang X, Laskowitz DT, He L, Ostbye T, Bettger JP, Cao Y, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and the prevalence of stroke and coronary heart disease in rural China: A population-based study. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:388–395. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNaughton H, Feigin V, Kerse N, Barber PA, Weatherall M, Bennett D, et al. Ethnicity and functional outcome after stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:960–964. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhopal RS, Bansal N, Fischbacher CM, Brown H, Capewell S, Scottish H. Ethnic variations in the incidence and mortality of stroke in the Scottish Health and Ethnicity Linkage study of 4.65 million people. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2012;19:1503–1508. doi: 10.1177/1741826711423217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heeley EL, Wei JW, Carter K, Islam MS, Thrift AG, Hankey GJ, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in stroke rates and outcome: Pooled analysis of stroke incidence studies in Australia and New Zealand. The Medical journal of Australia. 2011;195:10–14. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeyemo A, Tayo BO, Luke A, Ogedegbe O, Durazo-Arvizu R, Cooper RS. The Nigerian Antihypertensive Adherence trial: A community-based randomized trial. Journal of hypertension. 2013;31:201–207. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835b0842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendis S, Johnston SC, Fan W, Oladapo O, Cameron A, Faramawi MF. Cardiovascular risk management and its impact on hypertension control in primary care in low-resource settings: A cluster-randomized trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:412–419. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.062364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen R, Crichton S, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, Sheldenkar A, Wolfe CD. Association between socioeconomic deprivation and functional impairment after stroke: The South London Stroke Register. Stroke. 2015;46:800–805. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardois P, Booth A, Goyder E, Ryan T. Health promotion interventions for increasing stroke awareness in ethnic minorities: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:409. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davalos A, Castillo J, Martinez-Vila E. Delay in neurological attention and stroke outcome. Cerebrovascular diseases study group of the Spanish Society of Neurology. Stroke. 1995;26:2233–2237. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.12.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qian F, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Xian Y, Pan W, Hannan EL, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in outcomes in older patients with acute ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:284–292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ottenbacher KJ, Campbell J, Kuo YF, Deutsch A, Ostir GV, Granger CV. Racial and ethnic differences in postacute rehabilitation outcomes after stroke in the United States. Stroke. 2008;39:1514–1519. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisabeth LD, Sanchez BN, Baek J, Skolarus LE, Smith MA, Garcia N, et al. Neurological, functional, and cognitive stroke outcomes in Mexican Americans. Stroke. 2014;45:1096–1101. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kissela B, Schneider A, Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Miller R, Alwell K, et al. Stroke in a biracial population: The excess burden of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 2004;35:426–431. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110982.74967.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleindorfer D, Broderick J, Khoury J, Flaherty M, Woo D, Alwell K, et al. The unchanging incidence and case-fatality of stroke in the 1990s: A population-based study. Stroke. 2006;37:2473–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000242766.65550.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, McClure LA, Safford MM, Rhodes JD, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:619–627. doi: 10.1002/ana.22385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Risser JM, Uchino K, Garcia N, et al. Excess stroke in mexican americans compared with non-hispanic whites: The brain attack surveillance in corpus christi project. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:376–383. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carandang R, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Kelly-Hayes M, Kase CS, Kannel WB, et al. Trends in incidence, lifetime risk, severity, and 30-day mortality of stroke over the past 50 years. JAMA. 2006;296:2939–2946. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, Alwell K, Woo D, Flaherty ML, et al. Stroke incidence is decreasing in whites but not in blacks: A population-based estimate of temporal trends in stroke incidence from the greater Cincinnati/northern Kentucky stroke study. Stroke. 2010;41:1326–1331. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Sanchez BN, Brown DL, Zahuranec DB, Garcia N, et al. Persistent ischemic stroke disparities despite declining incidence in mexican americans. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:778–785. doi: 10.1002/ana.23972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong KS, Yegiaian S, Lee M, Lee J, Saver JL. Declining stroke and vascular event recurrence rates in secondary prevention trials over the past 50 years and consequences for current trial design. Circulation. 2011;123:2111–2119. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen NB, Holford TR, Bracken MB, Goldstein LB, Howard G, Wang Y, et al. Trends in one-year recurrent ischemic stroke among the elderly in the USA:1994–2002. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30:525–532. doi: 10.1159/000319028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, Jensen GV, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:383–393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, Turan TN, Fiorella D, Lane BF, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redmond N, Baer HJ, Hicks LS. Health behaviors and racial disparity in blood pressure control in the national health and nutrition examination survey. Hypertension. 2011;57:383–389. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones SP, Jenkinson AJ, Leathley MJ, Watkins CL. Stroke knowledge and awareness: An integrative review of the evidence. Age Ageing. 2010;39:11–22. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard G, Prineas R, Moy C, Cushman M, Kellum M, Temple E, et al. Racial and geographic differences in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Stroke. 2006;37:1171–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217222.09978.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown DL, Conley KM, Sánchez BN, Resnicow K, Cowdery JE, Sais E, et al. A multicomponent behavioral intervention to reduce stroke risk factor behaviors: The SHARE cluster-randomized controlled trial. [published online ahead of print September 15:2015] [Accessed September 21, 2015];Stroke. 2015 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010678. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/early/2015/09/15/STROKEAHA.115.010678.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carty CL, Keene KL, Cheng YC, Meschia JF, Chen WM, Nalls M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies genetic risk factors for stroke in African Americans. Stroke. 2015;46:2063–2068. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwamm LH, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Smith EE, Frankel MR, Olson D, et al. Race/ethnicity, quality of care, and outcomes in ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2010;121:1492–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.881490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skolarus LE, Jones DK, Lisabeth LD, Burke JF. The Affordable Care Act and stroke. Stroke. 2014;45:2488–2492. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boden-Albala B, Carman H, Southwick L, Parikh NS, Roberts E, Waddy S, et al. Examining barriers and practices to recruitment and retention in stroke clinical trials. Stroke. 2015;46:2232–2237. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moxaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleindorfer D, Khoury J, Broderick JP, Rademacher E, Woo D, Flaherty ML, et al. Temporal trends in public awareness of stroke: Warning signs, risk factors, and treatment. Stroke. 2009;40:2502–2506. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgenstern LB, Gonzales NR, Maddox KE, Brown DL, Karim AP, Espinosa N, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to teach middle school children to recognize stroke and call 911: The Kids Identifying and Defeating Stroke project. Stroke. 2007;38:2972–2978. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams O, DeSorbo A, Noble J, Shaffer M, Gerin W. Long-term learning of stroke knowledge among children in a high-risk community. Neurology. 2012;79:802–806. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182661f08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment. Washington, D.C.: The National Academic Press; 2003. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare of the Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trivedi AN, Nsa W, Hausmann LR, Lee JS, Ma A, Bratzler DW, et al. Quality and equity of care in U.S. Hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2298–2308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1405003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas JS, Linder JA, Park ER, Gonzalez I, Rigotti NA, Klinger EV, et al. Proactive tobacco cessation outreach to smokers of low socioeconomic status: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175:218–226. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]