Abstract

The piggyBac (PB) transposon is one of the most useful transposable elements, and has been successfully used for genetic manipulation in more than a dozen species. However, the efficiency of PB-mediated transposition is still insufficient for many purposes. Here, we present a strategy to enhance transposition efficiency using a fusion of transcription activator-like effector (TALE) and the PB transposase (PBase). The results demonstrate that the TALE-PBase fusion protein which is engineered in this study can produce a significantly improved stable transposition efficiency of up to 63.9%, which is at least 7 times higher than the current transposition efficiency in silkworm. Moreover, the average number of transgene-positive individuals increased up to 5.7-fold, with each positive brood containing an average of 18.1 transgenic silkworms. Finally, we demonstrate that TALE-PBase fusion-mediated PB transposition presents a new insertional preference compared with original insertional preference. This method shows a great potential and value for insertional therapy of many genetic diseases. In conclusion, this new and powerful transposition technology will efficiently promote genetic manipulation studies in both invertebrates and vertebrates.

Transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) are naturally conserved bacterial effector proteins derived from the Xanthomonas genus of plant pathogenic bacteria1. To date, TALE proteins have been described as having a simple modular DNA recognition code2,3, that is composed of repeat domains of 33–35 amino acids. The specificity of TALE is determined by the repeat-variable di-residues (RVDs) at positions 12 and 13 of these repeats4,5. In recent years, TALE nucleases (TALENs) have been successfully and widely used for the targeted editing of endogenous genes in various species, including yeast6, nematodes7, frogs8, insects9,10, fish11,12,13,14, plants15,16 and mammals17,18. TALE proteins have also been engineered with transcriptional regulatory domains to generate artificial transcription factors that can regulate the expression of targeted endogenous genes16,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Recent, studies have demonstrated that TALEs can be efficiently exploited to modify epigenomes in a targeted manner26,27,28.

The piggyBac (PB) transposon, which was originally isolated from the genome of the cabbage looper moth Trichoplusia ni29, is a type of non-viral vector characterized by a large cargo size30, low toxicity31 and long-term expression32,33. PB transposon-mediated gene transfer has been successfully performed in various organisms, both invertebrates and vertebrates. Studies in silkworm have benefited from this technology because the silk-gland bioreactor shows great potential for the production of vast quantities of valuable exogenous protein via PB-mediated transgenesis. The PB transposon system is undoubtedly a powerful genetic manipulation tool for transgenesis and insertional mutagenesis and is currently being applied to the development of a new generation vector for research in human gene therapy and induced pluripotent stem cells34,35,36. However, the efficiency of PB-mediated transposition remains limited and unstable. The earliest and most appropriate method for evaluating transposition efficiency in silkworm is to calculate the percentage of G1 positive broods among all G0 moths37. Using this method, we have collected and analyzed most of the published transgenic data. However, as the current average for transposition efficiency in silkworm is 8.8% (Supplementary Table S1). The present transposition level must be improved to satisfy the requirements of research and to further promote the application of the PB system.

This study presents a monomeric fusion protein engineered from TALE repeat arrays and PB transposase (PBase) to further exploit the potential functions of TALE. We find that the TALE-PBase fusion protein can significantly improve the transposition efficiency of the PB system.

Results

Transposition efficiency of piggyBac in silkworm

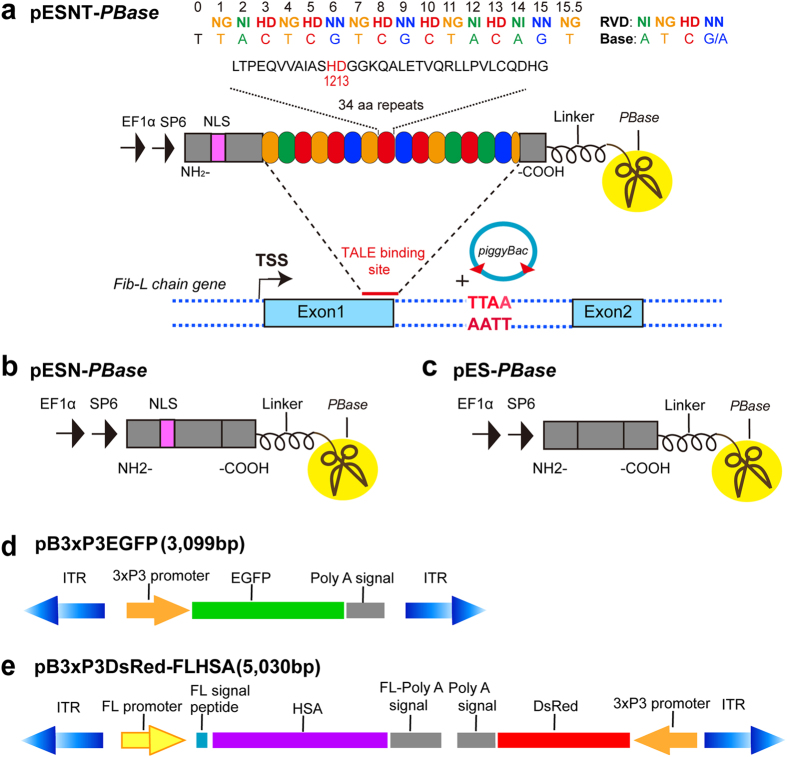

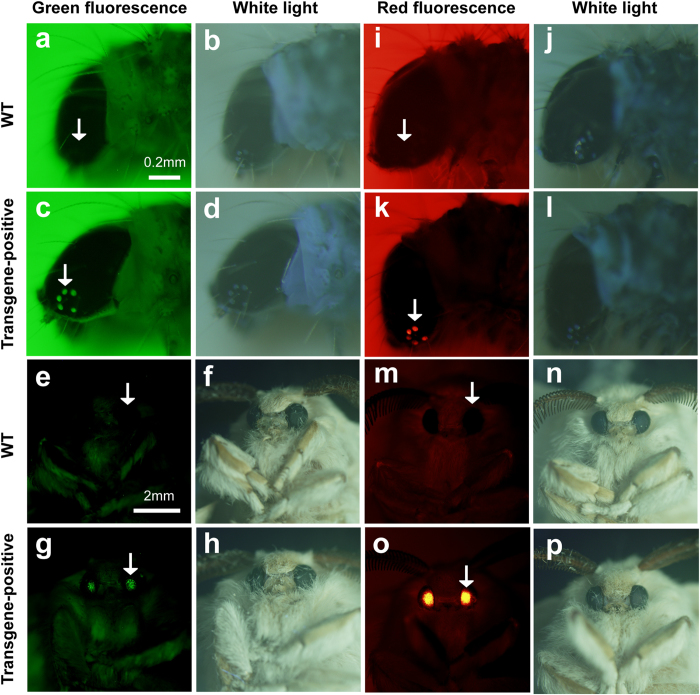

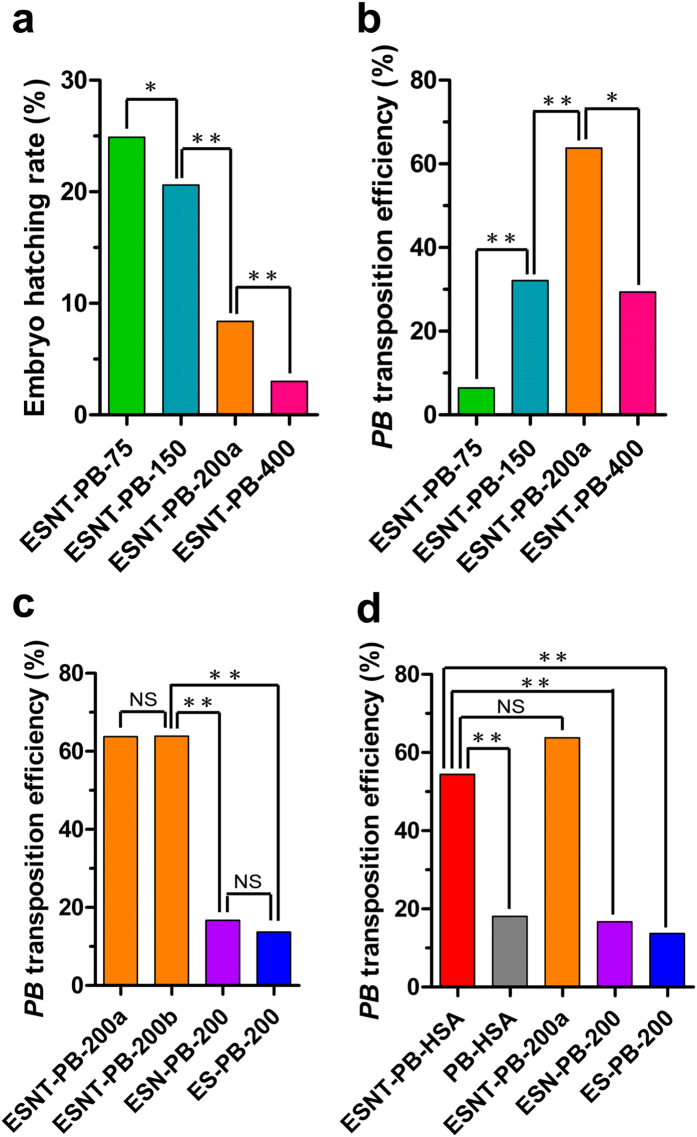

To investigate whether a programmable TALE could improve transposition efficiency, three types of plasmids were constructed: pESNT-PBase, consisting of EF1α and SP6 promoters, a nuclear localization signal (NLS), a TALE repeat domain targeting first exon of the fibroin light-chain gene and PBase (Fig. 1a); pESN-PBase, with the TALE sequence deleted (Fig. 1b); and pES-PBase, with both NLS and TALE sequence deleted (Fig. 1c). These plasmids were then transcribed in vitro to obtain mRNAs and each mRNA was mixed with the pB3 × P3EGFP transposon plasmid (Fig. 1d) and microinjected into fertilized embryos of the P50 silkworm strain. All of the positive silkworms exhibited a similar phenotype of larvae with green ocelli or moths with green compound eyes (Fig. 2a–h). To identify the optimal microinjection dose, four different concentrations of pESNT-PBase mRNA (Table 1) were injected. The hatching rate of the microinjected embryos decreased significantly with increasing concentration of pESNT-PBase mRNA (Table 1, Fig. 3a); the highest concentration (400 ng/μL) induced a high embryonic death rate, and only 3.0% of microinjected embryos hatched normally (Table 1). However, neither the highest or lowest mRNA concentration could result in the best transposition efficiency. Overall, injected of 200 ng/μL produced the best transposition efficiency, 63.8% (37/58), which was significantly higher than with the other concentrations (Table 1, Fig. 3b). Using this optimal concentration, we compared the transposition efficiencies of three different plasmids, pESNT-PBase, pESN-PBase and pES-PBase. PBase fused to the NLS (pESN-PBase) did not significantly improve the transposition efficiency in comparison with PBase alone (pES-PBase, P > 0.05) (Table 1, Fig. 3c). In contrast, the transformation frequency was significantly (P < 0.01) improved up to 63.9% (23/36) when pESNT-PBase, containing the TALE domain, was injected (Table 1, Fig. 3c). These data demonstrate that the TALE domain robustly improve transposition efficiency.

Figure 1. Design and construction of artificial TALE and PB transposon plasmids for producing transgenic silkworms.

(a) Schematic representation of the TALE tandem repeat domain and each repeat monomer, including the two repeat variable di-residues (RVD) at positions 12 and 13 of each amino acid sequence, which determine the base recognition specificity. TALE arrays comprising 16 repeats (colored ovals) fused to the PB transposase (PBase). EF1α, elongation factor-1 alpha promoter; SP6, a prokaryotic promoter used for high-efficiency mRNA transcription in vitro; NLS, nuclear localization signal; Fib-L gene, fibroin light-chain gene of silkworm; TSS, transcriptional start site; TTAA, the target insertion site of the PB transposon. (b) Schematic representation of the TALE repeats are deleted in the pESN-PBase plasmid based on the pESNT-PBase plasmid. (c) Both the TALE repeat and the NLS are deleted in the pES-PBase plasmid. (d,e) Diagram of the structure of PB transposon plasmids. ITR, inverted terminal repeats of the PB transposon; 3 × P3 promoter, an artificial promoter specifically driving reporter gene expression in the ocelli of larvae or compound eyes of moths; FL promoter, silkworm fibroin light-chain promoter; HSA, human serum albumin.

Figure 2. Fluorescence of EGFP or DsRed is specific in the eyes of transgenic silkworm.

The first and third columns are viewed under the excitation wavelengths of GFP and DsRed, respectively; the second and fourth columns are white light illumination. The first and third rows are wild-type (WT) larvae on the first day after hatching and moths, respectively; the second and fourth rows are transgenic larvae on the first day after hatching and moths, respectively.

Table 1. TALE-mediated piggyBac transposition efficiency in P50 strain.

| Transgenic strain | Injected mRNA/concentration (ng/μL) | Microinjected embryos | Hatched embryos (%) | G1 generation broods | Examined G1 broods | EGFP-positive G1 broods (From examined broods) | Percentage of transposition efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESNT-PB-75 | pESNT-PBase/75 | 770 | 192 (24.9) | 89 | 47 | 3 | 6.4 |

| ESNT-PB-150 | pESNT-PBase/150 | 1100 | 227 (20.6) | 83 | 56 | 18 | 32.1 |

| ESNT-PB-200a | pESNT-PBase/200 | 850 | 71 (8.4) | 58 | 58 | 37 | 63.8 |

| ESNT-PB-400 | pESNT-PBase/400 | 1450 | 44 (3.0) | 17 | 17 | 5 | 29.4 |

| ESNT-PB-200b | pESNT-PBase/200 | 900 | 75 (8.3) | 36 | 36 | 23 | 63.9 |

| ESN-PB-200 | pESN-PBase/200 | 900 | 203 (22.6) | 110 | 48 | 8 | 16.7 |

| ES-PB-200 | pES-PBase/200 | 800 | 93 (11.6) | 119 | 51 | 7 | 13.7 |

The microinjected PB transposon plasmid was pB3 × P3EGFP and the concentration was 300 ng/μL.

Figure 3. Statistical analysis of the embryos hatching rate and transposition efficiency.

(a) The hatching rate is directly related to the concentration of pESNT-PBase mRNA injected. The hatching rate was significantly reduced by increasing the microinjection concentration. (b) Statistical analysis of the transposition efficiency indicates that 200 ng/μL of pESNT-PBase mRNA is the optimal concentration for obtaining the highest transposition efficiency and a moderate hatching rate (ESNT-PB-200a series transgenic strains). (c,d) The TALE-PBase fusion can significantly enhance the transposition frequency and maintain transposition at a high level (ESNT-PB-200a, ESNT-PB-200b and ESNT-PB-HSA), even using a larger PB transposon plasmid and in a new silkworm strain. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, using a significance test for percentage of two samples.

To demonstrate the universality of pESNT-PBase-mediated high-efficiency transposition, we selected a different silkworm strain, Lan10, as the transgenic receptor and constructed a larger PB transposon as the donor plasmid (Fig. 1e). The reporter gene 3 × P3DsRed was specifically expressed in the eyes of all positive transgenic silkworms (Fig. 2i–p). Indeed, pESNT-PBase significantly (P < 0.01) improved transposition efficiency, reaching 54.4% (56/103) in ESNT-PB-HSA series transgenic strains compared with PB-HSA strains (18.1%, 21/116) and producing significantly (P < 0.01) higher transposition rates than the ESN-PB-200 (16.7%, 8/48) and ES-PB-200 (13.7%, 7/51) transgenic strains (Table 2, Fig. 3d). However, the transposition efficiency of ESNT-PB-HSA series transgenic strains was not significantly different from that of ESNT-PB-200a. These data again confirmed that the TALE-PBase fusion could significantly and stably increase transposition frequency, even with a larger cargo size of the transposon plasmid and in a different silkworm strain.

Table 2. TALE-mediated piggyBac transposition efficiency in Lan10 strain.

| Transgenic strain | Injected mRNA or DNA/concentration (ng/μL) | Microinjected embryos | Hatched embryos (%) | G1 generation examined broods | DsRed -positive G1 broods | Percentage of transposition efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESNT-PB-HSA | pESNT-PBase/200 | 1100 | 234 (21.3) | 103 | 56 | 54.4 |

| PB-HSA | PBase (DNA)/200 | 1100 | 258 (23.4) | 116 | 21 | 18.1 |

The microinjected PB transposon plasmid was pB3 × P3DsRed-FLHSA and the concentration was 200 ng/μL.

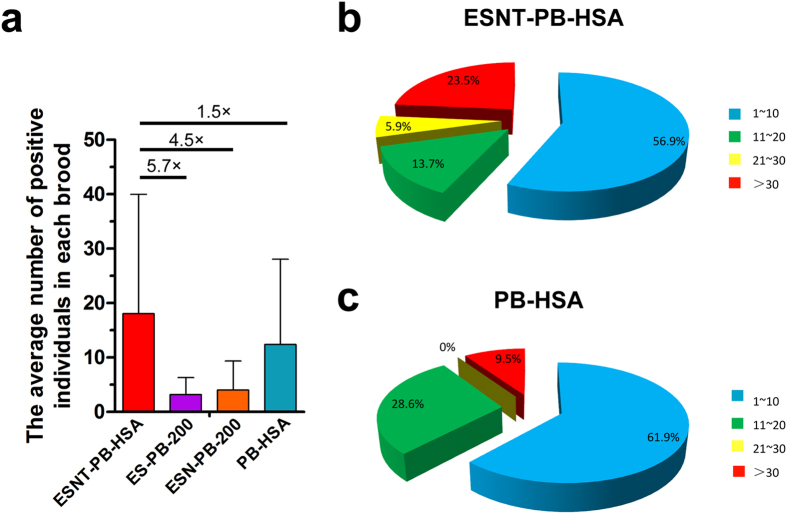

Furthermore, we compared the numbers of transgenic-silkworms in positive broods among ESNT-PB-HSA, PB-HSA, ESN-PB-200 and ES-PB-200. The average number of positive individuals in each ESNT-PB-HSA series transgenic brood reached 18.1, which was 1.5–5.7 times higher than for the three controls (Fig. 4a). We further performed a more detailed statistical analysis of the number of transgene-positive individuals between ESNT-PB-HSA and PB-HSA. The proportion of broods with more than 20 positive individuals, and especially with more than 30, was dramatically improved in ESNT-PB-HSA (Fig. 4b,c), for which nearly a quarter of positive broods were identified as containing over 30 transgene-positive silkworms. One positive brood (the ESNT-PB-HSA49 transgenic strain) contained 92 transgenic individuals (Supplementary Table S2). In general, TALE-mediated high-efficiency transposition is reflected in both the number of positive broods and the number of transgenic individuals per positive brood.

Figure 4. Quantification of transgenic individuals in each brood.

(a) The average number of positive silkworms in the ESNT-PB-HSA series transgenic strain was 5.7, 4.5 and 1.5 times higher than in ES-PB-200, ESN-PB-200 and PB-HSA, respectively. (b,c) Total positive broods are divided into four groups to more clearly present the distribution of the number of transgenic individuals in each brood. The pie charts show that the proportions of broods with 21–30 and > 30 transgenic individuals were dramatically improved in the ESNT-PB-HSA series transgenic silkworms compared with PB-HSA.

Analysis of insertion sites

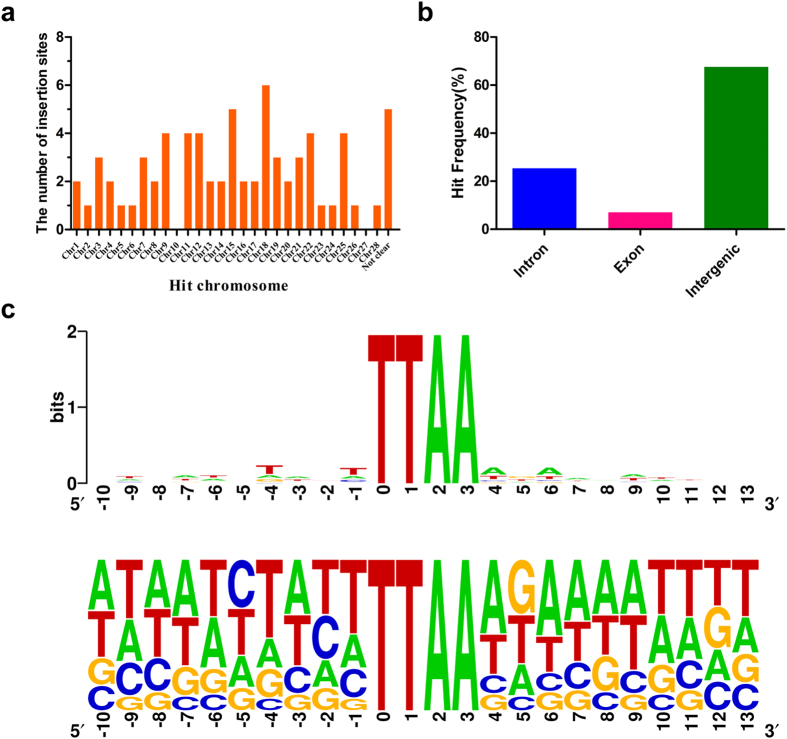

Previous studies have demonstrated that native PBase-mediated gene transposition primarily occurs at TTAA sites and has an insertional preference for AT-rich regions with 5 Ts before and 5 As after the TTAA sites in both insect and mammal38,39. Our analysis of integration sites indicated that all insertion events occurred in TTAA sites, which were widely distributed among the chromosomes (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table S3). Most of the transposition events occurred in introns and intergenic regions, with only 7.0% occurring in exons (Fig. 5b). Moreover, a sequence logo analysis indicated that the majority of insertion sites occurred in AT-rich regions (Fig. 5c). However, it is noteworthy that the proximal ten bases around the TTAA site presented a new pattern: the proportions of C, A and G bases at position −5, −3 and+5, respectively, were significantly enriched in comparison with previous studies (Fig. 5c). We believe that the insertional preference of PB was substantially altered by using the TALE-PBase fusion protein. In theory, the TALE-PBase fusion could achieve site-specific integration; however, no insertion events have been identified as occurring in a targeted manner. In the present study, two transposition events, ESNT-PB-200a26 and ESNT-PB-200b18, were identified integrating in the target chromosome (chromosome 14) and scaffold (scaffold 81) (Supplementary Table S3), but which were 278,440 bp and 156,461 bp away from the target integration site, respectively.

Figure 5. piggyBac insertion site analysis in silkworm.

(a) Distribution of PB integration sites on chromosomes. PB broadly targeted all chromosomes, except chromosomes10 and 27. (b) Analysis of integration sites in genes showing that most PB insertions were found in intergenic regions and introns, with only 7.0% appearing in exons. (c) Sequence logo analysis of the nucleotide composition of 20 bp flanking sequences around the insertion site “TTAA” based on 71 PB insertion events. All of the integrations show TTAA target site specificity, and an enrichment of As and Ts in the flanking sequences is observed. However, the nearest five nucleotides upstream and downstream of the integration sites are changed, presenting a novel pattern of nucleotide composition compared with previous reports.

Discussion

The extensive utilization of the PB transgenic system has been proven its value in genetic manipulation studies. In recent years, TALEs have demonstrated powerful functions in targeted gene editing, gene regulation and locus-specific histone modifications. So far, no reports have been found from available literatures about the TALE-PBase fusions can improve transposition efficiency in other species. The purpose of the present study was to engineer a TALE-PBase fusion to improve transposition efficiency. Our results show that PBase fused to an NLS cannot significantly enhance transposition efficiency, suggesting that PBase may already contain a functional nuclear targeting signal40. Therefore, TALE was the most important factor that improved PB transposition efficiency, which was enhanced by almost 64%, at least 7 times higher than the current average transposition efficiency in silkworm. In addition, the number of positive individuals in each transgenic brood was maximally increased by up to 5.7-fold. The improvements in these two characteristics present a breakthrough in the optimization of the PB transposon system. Moreover, modestly increasing the PB cargo size did not produce a significant reduction (P > 0.05) in the transposition efficiency. Thus, a PB element can simultaneously carry multiple genes to satisfy complex transgenic studies without reducing the frequency of transposition. The PB-mediated transgenic efficiency is affected by many factors, so it is hard to get a generally stable transgenic efficiency in the previous studies. In general, the transgenic efficiency of PB is insufficient in silkworms. From Supplementary Table S1 we could find that only one study achieved high-efficiency transgenesis (57.61%), but such a result was unstable, which merely appeared once from the four independent transgenic experiments41. In our study, the sufficient data demonstrate that the high transgenic efficiency is more stable and repeatable instead of appearing as an accidental phenomenon. So, our results fully illustrate the reliability of the TALE mediates high-efficiency transposition. The native PBase may be replaced by this new-type and high-efficient TALE-PBase fusion in the future. The next step of the research is to construct more TALE-PBase fusion proteins with different targets, which may help us to find more efficient TALE-PBase fusions.

This high TALE-mediated transposition frequency may be induced by multiple factors. The fusion of TALE and PBase may increase the three-dimensional structural stability of PBase, possibly prolonging the period of enzyme activity. As a result, more PB transposons are efficiently inserted into the genome. Furthermore, although the gene regulation is complex, it can be accurately long-range controlled by distant regulatory elements, including enhancers and repressors, to coordinated expression of genes in the third dimension42,43. TALE-mediated gene transposition may also be achieved in a long-range manner in the third dimension (Supplementary Fig. S1). In our study, a monomer TALE was fused to an intact PBase, producing an enzyme that can perform all the steps necessary for transposition. We therefore reason that the TALE-PBase fusion will combine with many potential candidate loci that may not perfectly matched the preferred TALE site. When TALE recognizes an appropriate site in the genome, PBase will execute transposition at multiple candidate “TTAA” sites (Supplementary Fig. S1) because the TALE-PBase fusion protein is larger than the native PBase protein and thus can perform transposition at a larger spatial scale. As some candidate “TTAA” sites may be hundreds of kilobases away from the TALE binding site (Supplementary Fig. S1a) or may even be located on different chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. S1b), the three-dimensionality of TALE-mediated transposition contributes to improving transposition efficiency.

Using a PBase coupled with a TALE, the first site-specific insertion of PB was recently identified in ~0.010-0.014% of stably transfected human cells44. Although this demonstrates that targeted insertions can be achieved, but the efficiency is still very low. Here, we have not found site-specific integration events, but TALE-mediated transposition has been shown to slightly alter the original insertion preference of PB (Fig. 5c). So, site-specific integration is still a challenge, but it may be markedly improved if the ability of PBase to recognize its target locus is weakened without compromising its catalytic function. Our results provide important clues for developing a high-efficiency insertional therapy tool which has shown greatly potential value in genetic disease therapy.

In summary, our study first demonstrates that the TALE-PBase fusion powerfully improves transposition efficiency in silkworms. This discovery introduces a new area for the application of TALE in research. To date, the PB system and TALE have been widely applied in various species of invertebrates and vertebrates. Thus, we believe that a TALE-PBase fusion will also function well in organisms other than silkworms. Our study will greatly promote PB-mediated genetic manipulation studies, including the generation of transgenic animals, insertional mutagenesis and gene therapy.

Methods

Construction of TALE-PBase fusion and transgenic plasmids

Target TALE assembly was performed using a FastTALETM TALEN kit (SIDANSAI biotechnology CO., LTD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The targeted binding site was in the first exon of the fibroin light chain (Fib-L) gene (chromosome14, scaffold81) (Supplementary Fig. S2), the expression product of which is the main component of fibroin in silkworm. The PBase gene was then engineered into the TALE vector, and the constructed plasmid was named pESNT-PBase due to the inclusion of EF1α, a ubiquitous promoter which exhibits a strong activity in eukaryotic cells, and SP6 promoters, an NLS, a TALE repeat domain and PBase. In addition, two control plasmids, pESN-PBase (TALE deleted) and pES-PBase (both TALE and NLS deleted), were constructed from pESNT-PBase. The mRNA of these vectors was synthesized in vitro using an SP6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). The donor plasmids pB3 × P3EGFP and pB3 × P3DsRed-FLHSA (FLHSA, human serum albumin gene driven by a Fib-L promoter) were constructed based on pBA3EGFP transposon plasmid. The marker gene (EGFP or DsRed) was controlled by a 3 × P3 promoter, an artificial promoter specifically driving expression in the eyes and nervous tissues, which is useful for the screening of positive individuals. All plasmids were extracted using the Quick Plasmids Miniprep kit (Invitrogen), followed by further purification to remove residual RNase A, as described in the SP6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). Briefly, plasmid DNA was treated with 0.5% SDS and proteinase K (200 μg/mL) for 30 min at 50 °C, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction (using an equal volume) and precipitation with 2 volumes of ethanol. Finally, the samples were centrifuged at 23,500 g for 15 min to harvest the purified DNA.

Transgenesis and screening of silkworms

The experimental animals P50 (Dazao) and Lan10, multivoltine silkworm strains with diapause ability, were reared on fresh mulberry leaves under standard conditions (25 °C, 80% R.H). Embryo microinjection and the screening of positive silkworms were performed as described previously37,45. Briefly, zygotes were collected promptly, and microinjection was completed within 4 h after oviposition. The helper plasmid pESNT-PBase mRNA was mixed with the donor plasmid pB3 × P3EGFP based on the actual concentration before injection into one-cell-stage fertilized eggs. The microinjected eggs were cultured under standard conditions, and each surviving moth was mated with wild-type moths to obtain G1 generations. Finally, positive individuals were screened from G1 broods based on the presence of green or red eyes using a fluorescence microscope SZX16 (Olympus). The procedures for the other two helper plasmid mRNAs, pESN-PBase and pES-PBase, were similar to the protocol described above.

Statistics of published transposition efficiency

The most appropriate method for the evaluation of silkworm transposition efficiency is to calculating the percentage of G1 positive broods in total G0 moths37. However, in some studies, transgenic G0 moths were mated with each other or mated within the same family to generate G1 broods, and the ratio of G1 positive broods/total G1 broods was calculated as the final transposition efficiency. This computation method led to transposition efficiencies that were nearly twice those obtained using the former method. Therefore, we calibrated these transposition efficiencies by halving them in an effort to standardize the method for computing transposition efficiency.

Analysis of insertion sites

Inverse PCR analysis37 was conducted after genomic DNA was isolated from each positive transgenic silkworm strain. Briefly, 1 μg of total genomic DNA was digested with Sau3A I at 37 °C for 2 h and then self-ligated overnight at 16 °C using T4 DNA ligase (TAKARA). A 25–50 ng sample of ligated products were amplified using EX Taq polymerase (TAKARA) and specific primers (pB3 × P3EGFP left arm primer pair, 5′-ATCAGTGACACTTACCGCATTGACA-3′ and 5′-TGACGAGCTTGTTGGTGAGGATTCT-3′; pB3 × P3EGFP right arm primer pair, 5′-TACGCATGATTATCTTTAACGTA-3′ and 5′-GGGGTCCGTCAAAACAAAACATC-3′). The PCR program was conducted with a 3 min denaturation cycle at 96 °C followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 96 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 2 min at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified PCR products were sequenced after cloning in pMD19-T (TAKARA) to identify the exact sites of PB insertion into silkworm chromosomes. Two pairs of primers were designed for PCR detection of the same insertion sites. The forward primer 5′-CCTGTGGTAGATTCTGCGAAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCTTTACATGAGCCTGACGTCA-3′ were used for identification of ESNT-PB-200a1 and ESNT-PB-200a17a transgenic strains; the forward primer 5′-TCTGTCGCAAGTCGCCAGTTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCTTTACATGAGCCTGACGTCA-3′ were used for the identification of ESNT-PB-200a31 and ESNT-PB-200b7 transgenic strains.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ye, L. et al. TAL effectors mediate high-efficiency transposition of the piggyBac transposon in silkworm Bombyx mori L. Sci. Rep. 5, 17172; doi: 10.1038/srep17172 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Toshiki Tamura (National Institute of Sericultural and Entomological Science, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan) for providing the piggyBac transposon plasmid pPIGA3EGFP and helper plasmid. We thank Ernst A. Wimmer (Lehrstuhl für Genetik, Universität Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany) for providing pPIG3 × P3EGFP and pPIG3 × P3DsRed transposon plasmid. This work is supported by the grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2012CB114601), Projects of Zhejiang Provincial Science and Technology Plans (No. 2013C32048, No. 2012C12910).

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.Y., B.Z. designed experiments. L.Y., Z.Y., Q.Q., Y.Z., J.C., J.S. and B.Z. conducted experiments. L.Y. and B.Z. performed data analysis. L.Y. wrote the paper. B.Z. revised manuscript and coordinated the study. All authors read manuscript before submission.

References

- White F. F., Potnis N., Jones J. B. & Koebnik R. The type III effectors of Xanthomonas. Mol Plant Pathol 10, 749–766 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J. et al. Breaking the Code of DNA Binding Specificity of TAL-Type III Effectors. Science 326, 1509–1512, doi: 10.1126/science.1178811 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscou M. J. & Bogdanove A. J. A Simple Cipher Governs DNA Recognition by TAL Effectors. Science 326, 1501–1501, doi: 10.1126/science.1178817 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak A. N. S., Bradley P., Cernadas R. A., Bogdanove A. J. & Stoddard B. L. The Crystal Structure of TAL Effector PthXo1 Bound to Its DNA Target. Science 335, 716–719, doi: 10.1126/science.1216211 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng D. et al. Structural Basis for Sequence-Specific Recognition of DNA by TAL Effectors. Science 335, 720–723, doi: 10.1126/science.1215670 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. et al. Modularly assembled designer TAL effector nucleases for targeted gene knockout and gene replacement in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Research 39, 6315–6325, doi: 10.1093/Nar/Gkr188 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A. J. et al. Targeted Genome Editing Across Species Using ZFNs and TALENs. Science 333, 307–307, doi: 10.1126/science.1207773 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y. et al. Efficient targeted gene disruption in Xenopus embryos using engineered transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). P Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 17484–17489, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215421109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Y. et al. Efficient and Specific Modifications of the Drosophila Genome by Means of an Easy TALEN Strategy. J Genet Genomics 39, 209–215, doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.04.003 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S. Y. et al. Highly Efficient and Specific Genome Editing in Silkworm Using Custom TALENs. PLoS One 7, doi: ARTN e45035 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045035 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedell V. M. et al. In vivo genome editing using a high-efficiency TALEN system. Nature 491, 114–U133, doi: 10.1038/Nature11537 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. et al. Heritable gene targeting in zebrafish using customized TALENs. Nature Biotechnology 29, 699–700, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.1939 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander J. D. et al. Targeted gene disruption in somatic zebrafish cells using engineered TALENs. Nature Biotechnology 29, 697–698, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.1934 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu Y. et al. TALEN-mediated precise genome modification by homologous recombination in zebrafish. Nature Methods 10, 329-+, doi: 10.1038/Nmeth.2374 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Liu B., Spalding M. H., Weeks D. P. & Yang B. High-efficiency TALEN-based gene editing produces disease-resistant rice. Nature Biotechnology 30, 390–392, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.2199 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak T. et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting (vol 39, pg e82, 2011). Nucleic Acids Research 39, 7879–7879, doi: 10.1093/Nar/Gkr739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesson L. et al. Knockout rats generated by embryo microinjection of TALENs. Nature Biotechnology 29, 695–696, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.1940 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson D. F. et al. Efficient TALEN-mediated gene knockout in livestock. P Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 17382–17387, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211446109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. C. et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nature Biotechnology 29, 143–U149, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.1755 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F. et al. Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nature Biotechnology 29, 149–U190, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.1775 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Zhou R. H., Kuo Y. C., Cunniff M. & Zhang F. Comprehensive interrogation of natural TALE DNA-binding modules and transcriptional repressor domains. Nat Commun 3, doi: Artn 968Doi 10.1038/Ncomms1962 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A., Lohmueller J. J., Silver P. A. & Armel T. Z. Engineering synthetic TAL effectors with orthogonal target sites. Nucleic Acids Research 40, 7584–7595, doi: 10.1093/Nar/Gks404 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay J. P., Chapdelaine P., Coulombe Z. & Rousseau J. Transcription Activator-Like Effector Proteins Induce the Expression of the Frataxin Gene. Human Gene Therapy 23, 883–890, doi: 10.1089/Hum.2012.034 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultmann S. et al. Targeted transcriptional activation of silent oct4 pluripotency gene by combining designer TALEs and inhibition of epigenetic modifiers. Nucleic Acids Research 40, 5368–5377, doi: 10.1093/Nar/Gks199 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung J. K. & Sander J. D. INNOVATION TALENs: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 14, 49–55, doi: 10.1038/Nrm3486 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall E. M. et al. Locus-specific editing of histone modifications at endogenous enhancers. Nature Biotechnology 31, 1133-+, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.2701 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S. et al. Optical control of mammalian endogenous transcription and epigenetic states. Nature 500, 472-+, doi: 10.1038/Nature12466 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder M. L. et al. Targeted DNA demethylation and activation of endogenous genes using programmable TALE-TET1 fusion proteins. Nature Biotechnology 31, 1137-+, doi: 10.1038/Nbt.2726 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary L. C. et al. Transposon Mutagenesis of Baculoviruses - Analysis of Trichoplusia-Ni Transposon Ifp2 Insertions within the Fp-Locus of Nuclear Polyhedrosis Viruses. Virology 172, 156–169, doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90117-7 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. A. et al. Mobilization of giant piggyBac transposons in the mouse genome. Nucleic Acids Res 39, e148, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr764gkr764 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo M., Belay E., Chuah M. K. & Vandendriessche T. Recent developments in transposon-mediated gene therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 12, 841–858, doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.684875 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H., Higuchi Y., Kawakami S., Yamashita F. & Hashida M. piggyBac transposon-mediated long-term gene expression in mice. Mol Ther 18, 707–714, doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.302mt2009302 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saridey S. K. et al. PiggyBac transposon-based inducible gene expression in vivo after somatic cell gene transfer. Mol Ther 17, 2115–2120, doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.234mt2009234 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C. The piggyBac transposon holds promise for human gene therapy. P Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 14981–14982, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607282103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoste A., Berenshteyn F. & Brivanlou A. H. An Efficient and Reversible Transposable System for Gene Delivery and Lineage-Specific Differentiation in Human Embryonic Stem Cells (vol 5, pg 332, 2009). Cell Stem Cell 5, 568–568, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.013 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltjen K. et al. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 458, 766–U106, doi: 10.1038/Nature07863 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T. et al. Germline transformation of the silkworm Bombyx mori L. using a piggyBac transposon-derived vector. Nat Biotechnol 18, 81–84, doi: 10.1038/71978 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. et al. piggyBac internal sequences are necessary for efficient transformation of target genomes. Insect Molecular Biology 14, 17–30, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00525.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S. et al. Efficient transposition of the piggyBac resource (PB) transposon in mammalian cells and mice. Cell 122, 473–483, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.013 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith J. H., Fraser T. S. & Fraser M. J. Analysis of the piggyBac transposase reveals a functional nuclear targeting signal in the 94 c-terminal residues. Bmc Molecular Biology 9, doi: Artn 72Doi 10.1186/1471-2199-9-72 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S. et al. Genetic Marking of Sex Using a W Chromosome-Linked Transgene. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 43, 1079–1086 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J. Gene regulation in the third dimension. Science 319, 1793–1794, doi: 10.1126/science.1152850 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A., Lajoie B. R., Jain G. & Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature 489, 109–U127, doi: 10.1038/Nature11279 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. B. et al. Transcription activator like effector (TALE)-directed piggyBac transposition in human cells. Nucleic Acids Research 41, 9197–9207, doi: 10.1093/Nar/Gkt677 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B., Li J., Chen J., Ye J. & Yu S. Comparison of transformation efficiency of piggyBac transposon among three different silkworm Bombyx mori Strains. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 39, 117–122 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.