Abstract

Objective:

To study biomarkers of angiogenesis in Parkinson disease (PD), and how these are associated with clinical characteristics, blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and cerebrovascular disease.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional analysis, 38 elderly controls and 100 patients with PD (82 without dementia and 18 with dementia) were included from the prospective Swedish BioFinder study. CSF samples were analyzed for the angiogenesis biomarkers vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); its receptors, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2; placental growth factor (PlGF); angiopoietin 2 (Ang2); and interleukin-8. BBB permeability, white matter lesions (WMLs), and cerebral microbleeds (CMB) were assessed. CSF angiogenesis biomarkers were also measured in 2 validation cohorts: (1) 64 controls and 87 patients with PD with dementia; and (2) 35 controls and 93 patients with neuropathologically confirmed diagnosis of PD with and without dementia.

Results:

Patients with PD without dementia displayed higher CSF levels of VEGF, PlGF, and sVEGFR-2, and lower levels of Ang2, compared to controls. Similar alterations in VEGF, PlGF, and Ang2 levels were observed in patients with PD with dementia. Angiogenesis markers were associated with gait difficulties and orthostatic hypotension as well as with more pronounced BBB permeability, WMLs, and CMB. Moreover, higher levels of VEGF and PlGF levels were associated with increased CSF levels of neurofilament light (a marker of neurodegeneration) and monocyte chemotactic protein–1 (a marker of glial activation). The main results were validated in the 2 additional cohorts.

Conclusions:

CSF biomarkers of angiogenesis are increased in PD, and they are associated with gait difficulties, BBB dysfunction, WMLs, and CMB. Abnormal angiogenesis may be important in PD pathogenesis and contribute to dopa-resistant symptoms.

Angiogenesis might be an important mechanism involved in pathophysiology of Parkinson disease (PD). Increased numbers of endothelial cell nuclei and blood vessels have been found postmortem in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) of patients with PD1,2 and parkinsonian primates.3 PD status at the time of death is also associated with greater expression of integrin αvβ3, a selective marker of angiogenic endothelial cells, in the SNpc, the locus ceruleus, and putamen.4

Angiogenesis is regulated by a plethora of different proteins, including members of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family (e.g., VEGF and its receptors, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, placental growth factor [PlGF]),5 the angiopoietin (Ang) family (e.g., Ang2),6 and proinflammatory chemokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]–8).7

Previous postmortem studies exploring the role of angiogenesis in PD have included few cases.1,2 Consequently, there is a need to determine whether biomarkers of angiogenesis are reliably changed in PD. Moreover, the contribution of aberrant angiogenesis to specific aspects of PD symptomatology (such as cognitive or motor dysfunction) has not been investigated. It would be also interesting to establish if changes in angiogenesis biomarkers are associated with overall cerebrovascular pathology. To this end, we measured several biomarkers of angiogenesis in CSF samples from a large cohort of patients with PD with and without dementia and healthy controls. We investigated cross-sectional associations between the measured angiogenesis markers and disease symptoms, blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, white matter lesions (WML), and cerebral microbleeds (CMB). Finally, the main findings of the study were replicated in 2 additional cohorts of healthy controls and patients with PD, of which one consisted of neuropathologically confirmed cases.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The Ethics Committee of Lund University approved both studies originating from Lund. Study participants gave informed consent to research. The study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration.

Study population.

Cohort 1.

One hundred patients with PD and 38 healthy controls were enrolled in the prospective Swedish BioFinder study (www.biofinder.se) at the Neurology Clinic, Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden. The PD group included 82 patients without dementia (PDND) and 18 patients with dementia (PDD). PD diagnosis was set according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Diagnostic Criteria.8 PDD was diagnosed according to the Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia Associated with Parkinson's Disease.9

Analysis of the data from cohort 1 indicated that to provide 90% power at an α level of 0.05, a total of 100 patients would be required.

Cohort 2.

The first validation cohort included 64 healthy controls and 87 patients (25 PDD and 62 dementia with Lewy bodies [DLB]), all assessed at the Memory Clinic, Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden.

Cohort 3.

The second independent validation cohort included 35 healthy controls, 27 PDND patients, and 66 PDD patients, all neuropathologically confirmed cases selected by the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders. All participants or their legal representatives signed an Institutional Review Board–approved informed consent form before the time of death. The PDD group included 32 patients without AD-related histopathology and 34 patients with sufficient load of plaques and tangles to meet criteria for AD diagnosis. The 2 dementia groups were finally merged into one single group of PDD cases because the concurrent AD pathology was found not to have any impact on the parameters under investigation.

Detailed information on all the study cohorts is available in the supplemental data on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org.

CSF sampling and biological assays.

In cohort 1 and cohort 2, CSF was collected as described previously.10 In cohort 3 with neuropathology confirmed cases, postmortem CSF was collected from the lateral ventricles while the brain was still in situ, after removal of the skullcap. VEGF, PlGF, sVEGFR-1, sVEGFR-2, Ang2, and IL-8 were quantified in CSF samples from cohort 1 using multiplex electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD; supplemental data). All the samples were measured in duplicate and the mean of the duplicate was used in the statistical analysis. Detection limits are provided in the supplemental data. The coefficient of variation (CV) was below 20% for all assays. The few samples with CV >20% did not affect the results and were therefore included in the statistical analysis. In the validation cohort, VEGF, PlGF, and sVEGFR-1 were measured using the same methodology as above. For further validation purposes, CSF levels of VEGF were also measured using VEGF V-PLEX kit using other antibodies than the VEGF assay mentioned above (see supplemental data for details).

The albumin ratio was calculated as CSF albumin (mg/L)/plasma albumin (g/L) and was used as a measure of the BBB function. Albumin and monocyte chemotactic protein–1 (MCP-1) were measured as described previously.11,12 Total tau (t-tau; ADx Neurosciences NV, Gent, Belgium), neurofilament light (NFL; Uman Diagnostics, Umeå, Sweden), phospho-tau (p-tau), and β-amyloid (Aβ) 42 (Fujirebio Europe, Gent, Belgium) were analyzed using commercially available ELISA kits.

MRI.

In cohort 1, 32 controls and 58 patients with PD underwent MRI scans using a 3T Siemens® system to quantify WMLs and CMB (see supplemental data for details).

Statistical analyses.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical calculations. Due to skewness, all CSF biomarkers were transformed into their natural logarithm before analyses. Untransformed and unadjusted values are shown in table 1, tables e-1 and e-2. For groupwise comparisons, we used Student t test or one-way analysis of variance adjusting for covariates. For associations between 2 continuous variables, Pearson partial correlation was used. Standard linear regressions were used to investigate associations between a continuous dependent variable and continuous or categorical independent variables.

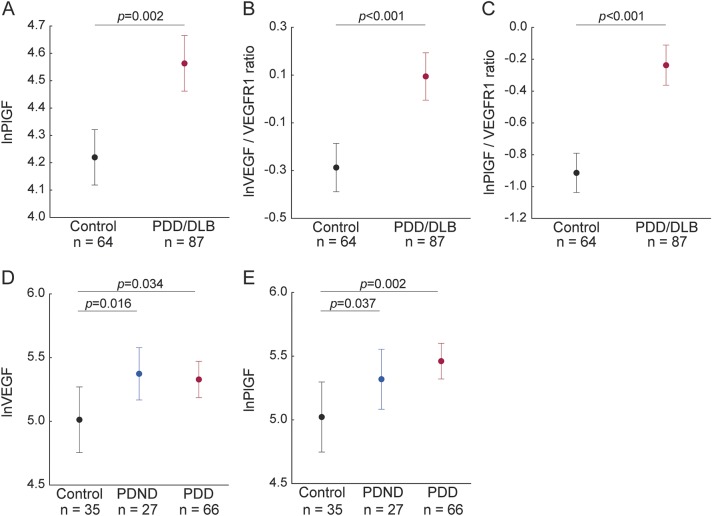

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and CSF levels of angiogenesis biomarkers in healthy controls, patients with PDND, and patients with PDD included in cohort 1

In addition to CSF concentrations of angiogenesis biomarkers, we also used the VEFG/sVEGFR-1 and PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratios when investigating associations with clinical data. The rationale for this is that sVEGFR-1 has direct antagonistic effect on VEFG and PlGF by sequestering the ligands from the membrane receptors.13–15 Consequently, high VEGF/sVEGFR-1 and PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratios provide an index of the bioactive levels of VEGF and PlGF.

In the control and patient groups, most of the analytes were positively associated with age (p < 0.05). There were also sex differences for VEGF, PlGF, and CSF/plasma albumin ratio (higher levels in men, p < 0.05). Therefore all the subsequent statistical analyses were controlled for age, whereas analyses of VEGF, PlGF, VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio, PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio, and CSF/plasma albumin ratio were also controlled for sex. In the PD group, status as de novo PD, disease duration, or levodopa equivalent were not associated with any of the measured CSF biomarkers, with the exception of IL-8, which correlated with levodopa equivalent (p < 0.05).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants as well as CSF concentrations of angiogenesis biomarkers for all the cohorts are given in table 1, tables e-1 and e-2.

Cohort 1: Group comparisons.

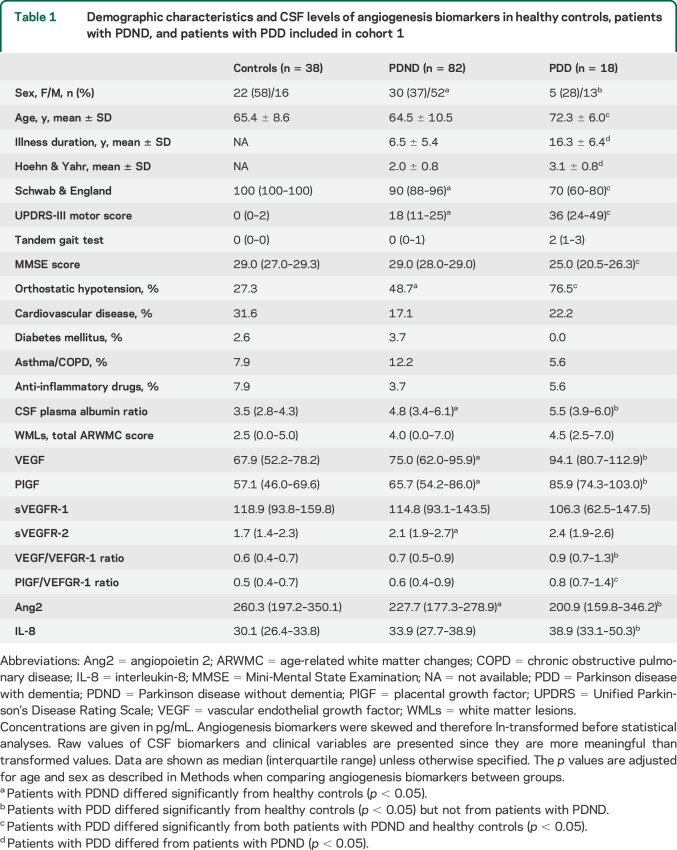

Univariate comparisons among the control, PDND, and PDD groups revealed altered levels of VEGF (p = 0.022), PlGF (p = 0.011), VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (p = 0.013), PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (p = 0.012), sVEGFR-2 (p = 0.001), Ang2 (p = 0.049), and IL-8 (p = 0.033). PDND patients displayed higher levels of VEGF (p = 0.012), PlGF (p = 0.020), and sVEGFR-2 (p < 0.001), and lower levels of Ang2 (p = 0.044), when compared to healthy controls (figure 1, A–D). Also in the PDD group, VEGF (p = 0.028) and PlGF (p = 0.005) were increased and Ang2 was decreased (p = 0.030) compared to controls (figure 1, A and B). Further, VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (p = 0.004), PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (p = 0.003), and IL-8 (p = 0.01) were selectively increased in PDD cases compared to controls (figure 1, E and F). Similar results were obtained with the VEGF V-PLEX kit (supplemental data, table e-3).

Figure 1. Angiogenesis biomarkers in CSF of healthy controls, PDND, and PDD patients (cohort 1).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (A), placental growth factor (PlGF) (B), sVEGFR-2 (C), angiopoietin 2 (Ang2) (D), VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (E), and PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (F) are altered in patients with Parkinson disease without dementia (PDND) and patients with Parkinson disease with dementia (PDD) compared to controls. Angiogenesis biomarkers were skewed and therefore ln-transformed before statistical analyses; p values are from analysis of covariance adjusting for age and sex as described in the Methods; data are presented as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Cohort 1: Angiogenesis biomarkers and clinical assessments.

In patients with PD (all participants), worse performance on the tandem gait test (indicating postural instability and gait difficulties) was associated with increased CSF levels of VEGF (β = 0.22, p = 0.037), PlGF (β = 0.34, p = 0.002), and IL-8 (β = 0.23, p = 0.014). We did not find any associations between angiogenesis biomarkers and cognitive performance assessed using Mini-Mental State Examination and Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale items 1–3. The associations between clinical symptoms and VEGF as well as PlGF were similar in the PDND group. However, in this group we also observed positive correlations between UPDRS-II item 15 (gait, off-state) and CSF VEGF (β = 0.46, p = 0.003) and PlGF (β = 0.38, p = 0.022) as well as a negative correlation between CSF Ang2 and UPDRS-III (β = −0.25, p = 0.029).

Orthostatic blood pressure might result in transient brain ischemia.16,17 PDND patients with a significant drop in diastolic blood pressure when standing had higher levels of VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio and PlGF/sVEGFR1 ratio compared with PDND patients without orthostatic diastolic hypotension (p = 0.029 and p = 0.014) or with controls (p = 0.004 and p = 0.005). The ratios did not differ between PDND patients without orthostatic diastolic hypotension and controls.

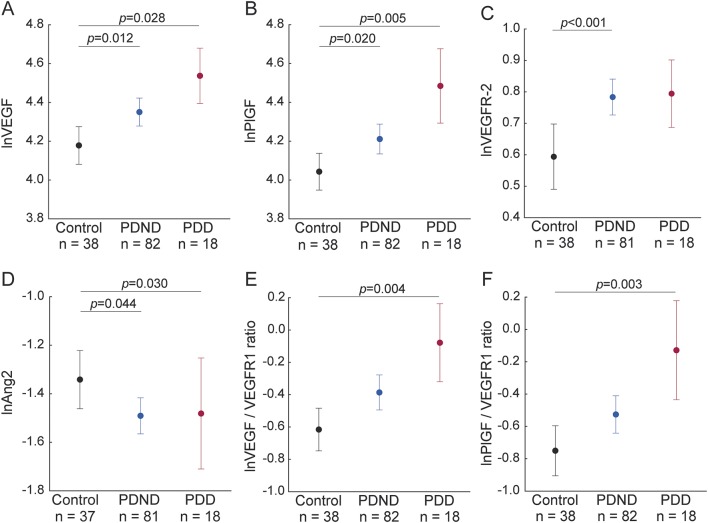

Cohort 1: Angiogenesis biomarkers and CSF/plasma albumin ratio.

Increased levels of CSF/plasma albumin ratio often reflects increased permeability of the BBB.18 The CSF/plasma albumin ratio differed between the diagnostic groups (p = 0.005; table 1). The ratio was higher in PDND patients (p = 0.001) and PDD patients (p = 0.027) compared to controls (figure 2A), while no difference was found between PDND patients and PDD patients. In all patients with PD, higher CSF/plasma albumin ratio was associated with higher CSF levels of VEGF (β = 0.48, p < 0.001; figure 2B) and PlGF (β = 0.43, p < 0.001; figure 2C), sVEGFR-2 (β = 0.41, p < 0.001), and IL-8 (β = 0.27, p = 0.009), as well as with higher VEGF/sVEGFR1 ratio (β = 0.33, p = 0.001) and PlGF/sVEGFR1 ratio (β = 0.29, p = 0.006). We observed similar associations when only including PDND patients (data not shown). In the control group, we did not find any significant associations between CSF/plasma albumin ratio and any of the angiogenesis variables or ratios (all p > 0.16).

Figure 2. Angiogenesis biomarkers, blood–brain barrier, and WMLs in controls, PDND, and PDD (cohort 1).

(A) The CSF/plasma albumin ratio is higher in patients with Parkinson disease without dementia (PDND) and patients with Parkinson disease with dementia (PDD) than in controls. (B–E) Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) are associated with the CSF/plasma albumin ratio and white matter lesions (WMLs) in patients with Parkinson disease. Angiogenesis biomarkers were skewed and therefore ln-transformed before statistical analyses; p values are from analysis of covariance (A) and from liner regression (B–E) adjusting for age and sex as described in the Methods; data in (A) are presented mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Cohort 1: Angiogenesis biomarkers, WMLs, and CMB.

WMLs (total age-related white matter changes [ARWMC] score) did not differ between the diagnostic groups (table 1). In patients with PD, the total burden of WMLs was associated with higher CSF levels of VEGF (β = 0.40, p = 0.004; figure 2D), PlGF (β = 0.42, p = 0.002; figure 2E), and IL-8 (β = 0.24, p = 0.044), as well as with higher VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (β = 0.37, p = 0.004) and PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (β = 0.38, p = 0.003). When only including PDND patients, we found similar results (data not shown). In the control group, we did not find any significant associations between total ARWMC score and any of the angiogenesis variables or ratios (all p > 0.14).

Patients with PD with signs of CMB (n = 13) had higher VEGF (p = 0.051) and PlGF (p = 0.020) levels than those who did not have CMB (n = 37).

Cohort 1: Angiogenesis biomarkers and markers of neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation.

NFL is a marker of axonal neurodegeneration.19 In patients with PD, higher levels of NFL in CSF are associated with more severe disease.20 Positive associations were found between CSF NFL levels and VEGF (β = 0.47, p = 0.001) and PlGF (β = 0.31, p = 0.021), as well as CSF/plasma albumin ratio (β = 0.41, p = 0.016) in patients with PD but not in controls. Supporting the role of NFL in axonal degeneration, we observed a strong association between WMLs (total ARWMC score) and CSF NFL levels (β = 0.60, p = 0.003).

CSF t-tau levels are considered to reflect cortical neurodegeneration,18 and the CSF tau levels did not correlate with PlGF or VEGF. Further, there were no correlations between PlGF and VEGF and the Alzheimer-specific biomarkers CSF p-tau or Aβ42.

To study possible associations of angiogenesis biomarkers with neuroinflammation, we measured the CSF levels of MCP-1, which is a chemoattractant expressed by microglia and astrocytes in the brain21 that can be reliably measured in CSF.22 MCP-1 was associated with VEGF in the patients with PD (β = 0.25, p = 0.027) but not in the controls.

The associations with markers of neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation were similar when only including PDND patients (data not shown).

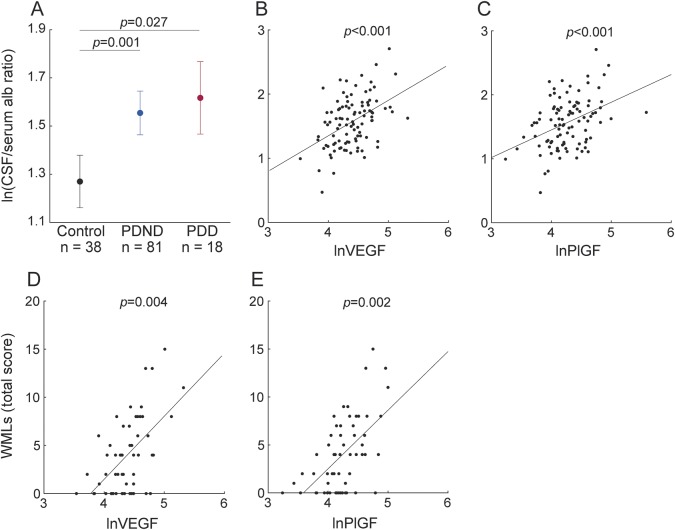

Cohort 2: Validation study.

In this cohort of controls and PDD/DLB patients, we analyzed CSF levels of VEGF, PlGF, and sVEGFR1. The patient group displayed higher mean levels of PlGF (p = 0.002), VEGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (p < 0.001), and PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio (p < 0.001) compared to the healthy controls (figure 3, A–C). In this cohort of patients we also confirmed the association of CSF/plasma albumin ratio with VEGF (β = 0.48, p < 0.001) and PlGF (β = 0.42, p = 0.002). Using VEGF V-PLEX kit, we found that VEGF levels were elevated in the PDD/DLB patients compared to the healthy controls (supplemental data).

Figure 3. CSF levels of angiogenesis biomarkers (cohorts 2 and 3).

(A–C) Placental growth factor (PlGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/sVEGFR-1 ratio, and PlGF/sVEGFR-1 ratio are higher in patients with Parkinson disease with dementia (PDD)/patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) than in controls in cohort 2. (D, E) VEGF and PlGF levels are elevated in patients with Parkinson disease without dementia (PDND) and patients with PDD compared to controls in cohort 3 with neuropathologically confirmed diagnosis. Angiogenesis biomarkers were skewed and therefore ln-transformed before statistical analyses; p values are from analysis of covariance adjusting for age and sex as described in the Methods; data are presented as mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Cohort 3: Validation study.

In this cohort of neuropathologically confirmed cases, we measured VEGF, PlGF, and sVEGFR-1 in postmortem ventricular CSF samples from PDND and PDD participants as well as healthy controls. In agreement with our previous findings, both the PDND and PDD groups showed elevated levels of VEGF (p = 0.016 and p = 0.034) and PlGF (p = 0.037 and p = 0.002) compared to the controls (figure 3, D and E). We did not find any difference in these analytes between the PDND and PDD groups. In all patients with PD, the total burden of WMLs was associated with higher CSF levels of VEGF (β = 0.24, p = 0.016), confirming our previous finding when comparing WMLs according to MRI and angiogenesis biomarkers in CSF. When only including the PDND patients, we found similar results (data not shown).

There were no associations between CSF levels of either VEGF or PlGF and amyloid plaque density (quantified according to the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease templates) or Braak tangle scores in patients with PD, suggesting that changes in angiogenic factors are not related to AD amyloid or tau pathology. These findings confirm the results obtained in cohort 1 using CSF AD biomarkers.

DISCUSSION

Using a well-characterized clinical sample, this study demonstrates that CSF levels of VEGF, PlGF, and sVEGFR-2 are high, while levels of Ang2 are low, in PDND and PDD patients compared to non-PD controls. We corroborate our findings of elevated CSF levels of VEGF and PlGF in 2 additional cohorts of patients with PD with and without dementia.

The increased CSF levels of angiogenesis factors in PD are in keeping with postmortem studies demonstrating high levels of VEGF and elevated numbers of endothelial cell nuclei and vessels in the SNpc of patients with PD, as well as primates with parkinsonian lesions.1–3,23 Previous reports have also suggested that PD might be accompanied by BBB dysfunction.24,25 In agreement with these reports, we found higher CSF/plasma albumin ratio in patients with PD compared to controls. Furthermore, we observed robust positive correlations between angiogenic factors and CSF/plasma albumin ratio, which is interesting considering that VEGF is a potent trigger of vascular leakage and BBB dysfunction.26,27 In other neurodegenerative diseases, mild but chronic increases in BBB permeability are known to contribute to neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration.28 Of relevance to PD, intranigral administration of VEGF induces BBB breakdown and loss of dopaminergic neurons.29 On the contrary, the angiogenic factor Ang2 decreases BBB leakage.30 Thus, increased levels of VEGF and PlGF, and decreased levels of Ang2, may concur to produce BBB dysfunction and neuronal toxicity in the affected brain regions. Accordingly, we found strong correlations between the CSF levels of NFL (a marker of axonal degeneration) and angiogenesis biomarkers in patients with PD.

BBB abnormalities are likely to be associated with structurally altered and leaky small vessels that may result in CMB.31 High serum VEGF and increased vascular permeability have been previously linked to CMB in acute ischemic stroke.32 Here we show that patients with PD with CMB have elevated CSF levels of VEGF and PlGF. These findings raise the possibility that angiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of CMB, in addition to BBB dysfunction, in PD.

The mechanisms behind the observed alterations in angiogenesis biomarkers in PD are yet to be elucidated. In the present study, we found that patients with PD with orthostatic diastolic hypotension have increased levels of VEGF and PlGF compared to patients without orthostatic diastolic hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension might result in recurrent episodes of transient cerebral hypoperfusion and hypoxia in cases with suboptimal autoregulation of cerebral blood flow as for example in PD.33,34 Hypoxia-induced VEGF signaling is one of the main molecular pathways triggering angiogenic responses.35 Hypoperfusion and hypoxia have been also proposed as a potential mechanism underlying previously observed association between orthostatic hypotension and WMLs.16,36 We found that increased levels of VEGF and PlGF in the CSF of patients with PD were related to more pronounced WMLs. Thus, elevated levels of angiogenesis biomarkers in patients with PD in our study may partly depend on the hypoxic environment associated with orthostatic hypotension and WMLs. WMLs have been linked to gait abnormalities and postural instability in large cohorts of healthy elderly individuals as well as patients with PD.37 Accordingly, in our PD cohorts elevated levels of VEGF and PlGF correlated with poor performance on the Tandem Gait Test. These findings suggest that WMLs and increased angiogenesis underpin, at least to some extent, the treatment-resistant symptoms that develop during the course of PD, such as postural instability and gait difficulties.

In our study, VEGF positively correlated with MCP-1, a proinflammatory chemokine expressed by astrocytes and microglia.21 Interestingly, one previous study reported a greater number of activated microglia together with signs of angiogenesis in the SNpc of parkinsonian brain.4 Others have shown that VEGF production can be triggered in astrocytes by proinflammatory cytokines.38,39 Collectively, these data suggest a possible link between neuroinflammation and angiogenesis in PD.

One potential limitation of the current study is the cross-sectional study design, thus causality may not be inferred. Another limitation is that it is not possible to obtain any regional or structural information using CSF. On the other hand, analysis of material, such as CSF, from living individuals with PD has some advantages over postmortem investigations. Relatively large series of patients can be studied, findings can easily be related to current symptomatology and imaging data in the same participants, and the results are not biased by death-related events, such as hypoxia. The proportion of individuals with major somatic comorbidities or using of anti-inflammatory medications did not significantly differ across groups, thus these factors are unlikely to have confounded our findings. A strength of the present study was the multimodal characterization of the original prospective cohort with clinical assessments, brain imaging, and different CSF biomarkers. Further, the main results obtained in the original cohort were validated in 2 independent cohorts, of which one consisted of neuropathologically confirmed cases. Finally, different ELISAs were used to measure VEGF in CSF, resulting in similar differences between diagnostic groups.

In the present study, we established that angiogenic factors are upregulated in the CSF in PD. The angiogenic activation was associated with gait difficulties, BBB dysfunction, WMLs, CBM, neuroinflammation, and axonal degeneration in patients but not in the control group, suggesting that these interactions are specific for PD. Our results warrant further mechanistic studies on the role of angiogenesis and cerebrovascular dysfunction in the development of some symptoms that respond poorly to dopamine replacement therapy in PD. These studies may have an important impact on the design of new personalized therapeutic approaches.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the research nurses, Ann Johansson, Jan Reimer, and Katarina Johansson, for their assistance in the clinical collection of CSF samples and data from study participants and healthy controls; and The Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium and the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona, for providing human CSF.

GLOSSARY

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- Ang

angiopoietin

- ARWMC

age-related white matter changes

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CMB

cerebral microbleeds

- CV

coefficient of variation

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- IL

interleukin

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein–1

- NFL

neurofilament light

- p-tau

phospho-tau

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PDD

Parkinson disease with dementia

- PDND

Parkinson disease without dementia

- PlGF

placental growth factor

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- t-tau

total tau

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WML

white matter lesions

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 1826

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.J. codesigned the study; collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; conducted literature searches; prepared figures; and cowrote the manuscript. D.L. codesigned the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, conducted literature searches, and cowrote the manuscript. V.F., S.H., H.Z., K.B., C.H.A., T.G.B., G.S., D.v.W., and E.L. collected and analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. M.A.C. codesigned the study, interpreted the data, conducted literature searches, overviewed data collection, cowrote the manuscript, and obtained funding. O.H. was the principal designer and coordinator of the study; overviewed collection, analysis, and interpretation of the study data; cowrote the manuscript; and obtained funding.

STUDY FUNDING

The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer's Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer's Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05–901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium), and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research. The study was supported by the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, the Parkinson Foundation of Sweden, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Crafoord Foundation, the Swedish Brain Foundation, the Swedish Federal Government under the ALF Agreement, The Torsten Söderberg Foundation, Multipark, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

S. Janelidze, D. Lindqvist, V. Francardo, S. Hall, and H. Zetterberg report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. K. Blennow has served on advisory boards for IBL International, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, Lilly, and Kyowa Kirin Pharma. C. Adler, T. Beach, G. Serrano, D. van Westen, E. Londos, M. Cenci, and O. Hansson report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faucheux BA, Bonnet AM, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Blood vessels change in the mesencephalon of patients with Parkinson's disease. Lancet 1999;353:981–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wada K, Arai H, Takanashi M, et al. Expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport 2006;17:705–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barcia C, Bautista V, Sanchez-Bahillo A, et al. Changes in vascularization in substantia nigra pars compacta of monkeys rendered parkinsonian. J Neural Transm 2005;112:1237–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai Bradaric B, Patel A, Schneider JA, Carvey PM, Hendey B. Evidence for angiogenesis in Parkinson's disease, incidental Lewy body disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neural Transm 2012;119:59–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med 2003;9:669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiedler U, Augustin HG. Angiopoietins: a link between angiogenesis and inflammation. Trends Immunol 2006;27:552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiefer F, Siekmann AF. The role of chemokines and their receptors in angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011;68:2811–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 1999;56:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2007;22:1689–1707; quiz 1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertze J, Nagga K, Minthon L, Hansson O. Changes in cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma levels of IGF-II and its binding proteins in Alzheimer's disease: an observational study. BMC Neurol 2014;14:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindqvist D, Hall S, Surova Y, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory markers in Parkinson's disease: associations with depression, fatigue, and cognitive impairment. Brain Behav Immun 2013;33:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zetterberg H, Jakobsson J, Redsater M, et al. Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier dysfunction in patients with bipolar disorder in relation to antipsychotic treatment. Psychiatry Res 2014;217:143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambati BK, Nozaki M, Singh N, et al. Corneal avascularity is due to soluble VEGF receptor-1. Nature 2006;443:993–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendall RL, Thomas KA. Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:10705–10709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi JW, Qin TT, Xu LX, et al. TNFSF15 inhibits vasculogenesis by regulating relative levels of membrane-bound and soluble isoforms of VEGF receptor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:13863–13868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruit MC, Thijs RD, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ, van Buchem MA, van Dijk JG. Syncope and orthostatic intolerance increase risk of brain lesions in migraineurs and controls. Neurology 2013;80:1958–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roman GC, Erkinjuntti T, Wallin A, Pantoni L, Chui HC. Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol 2002;1:426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blennow K, Hampel H, Weiner M, Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skillback T, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Mattsson N. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease and subcortical axonal damage in 5,542 clinical samples. Alzheimers Res Ther 2013;5:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall S, Ohrfelt A, Constantinescu R, et al. Accuracy of a panel of 5 cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the differential diagnosis of patients with dementia and/or parkinsonian disorders. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao Y, Tsirka SE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and the blood-brain barrier. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014;71:683–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westin K, Buchhave P, Nielsen H, Minthon L, Janciauskiene S, Hansson O. CCL2 is associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline during early stages of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One 2012;7:e30525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohlin KE, Francardo V, Lindgren HS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is upregulated by L-dopa in the parkinsonian brain: implications for the development of dyskinesia. Brain 2011;134:2339–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kortekaas R, Leenders KL, van Oostrom JC, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in parkinsonian midbrain in vivo. Ann Neurol 2005;57:176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pisani V, Stefani A, Pierantozzi M, et al. Increased blood-cerebrospinal fluid transfer of albumin in advanced Parkinson's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argaw AT, Asp L, Zhang J, et al. Astrocyte-derived VEGF-A drives blood-brain barrier disruption in CNS inflammatory disease. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2454–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature 2005;437:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 2008;57:178–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rite I, Machado A, Cano J, Venero JL. Blood-brain barrier disruption induces in vivo degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons. J Neurochem 2007;101:1567–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marteau L, Valable S, Divoux D, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is vasoprotective in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yates PA, Villemagne VL, Ellis KA, Desmond PM, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Cerebral microbleeds: a review of clinical, genetic, and neuroimaging associations. Front Neurol 2014;4:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dassan P, Brown MM, Gregoire SM, Keir G, Werring DJ. Association of cerebral microbleeds in acute ischemic stroke with high serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1186–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novak V, Novak P, Spies JM, Low PA. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in orthostatic hypotension. Stroke 1998;29:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vokatch N, Grotzsch H, Mermillod B, Burkhard PR, Sztajzel R. Is cerebral autoregulation impaired in Parkinson's disease? A transcranial Doppler study. J Neurol Sci 2007;254:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YW, Byzova TV. Oxidative stress in angiogenesis and vascular disease. Blood 2014;123:625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh YS, Kim JS, Lee KS. Orthostatic and supine blood pressures are associated with white matter hyperintensities in Parkinson disease. J Mov Disord 2013;6:23–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohnen NI, Albin RL. White matter lesions in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2011;7:229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Argaw AT, Zhang Y, Snyder BJ, et al. IL-1beta regulates blood-brain barrier permeability via reactivation of the hypoxia-angiogenesis program. J Immunol 2006;177:5574–5584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loeffler S, Fayard B, Weis J, Weissenberger J. Interleukin-6 induces transcriptional activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in astrocytes in vivo and regulates VEGF promoter activity in glioblastoma cells via direct interaction between STAT3 and Sp1. Int J Cancer 2005;115:202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.