Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether there are differences in the clinical presentation of symptoms and vulvar pain ratings in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) enrolled in a clinical trial, after correcting for estrogen deficiency.

METHODS

Questionnaire data was collected from seventy-six pre-menopausal and twenty post-menopausal women enrolled in a clinical trial for PVD. The questionnaire obtained information about the presence or absence of vulvar pain, the characteristics of this pain, and information about the women's demographic characteristics and reproductive health history.

Participants were clinically confirmed to have PVD by a positive cotton swab test on pelvic exam and either absence of, or corrected vulvovaginal atrophy based on Ratkoff staining with <10% parabasal cells. Women completed a standardized questionnaire describing their vulvar symptoms and rated daily pain on a visual analogue scale (0 = no pain to 10 = worse pain imaginable) from sexual intercourse, tampon insertion (as a surrogate measure of intercourse) and 24-hour vulvar pain for 2 weeks during the screening period. Pre-treatment data were analyzed prior to pharmacologic intervention. Chi-Square was used to determine differences between pre- and postmenopausal women in demographic characteristics and clinical presentation, and independent t-tests were used to analyze pain ratings by (0-10) numeric rating scale (NRS).

RESULTS

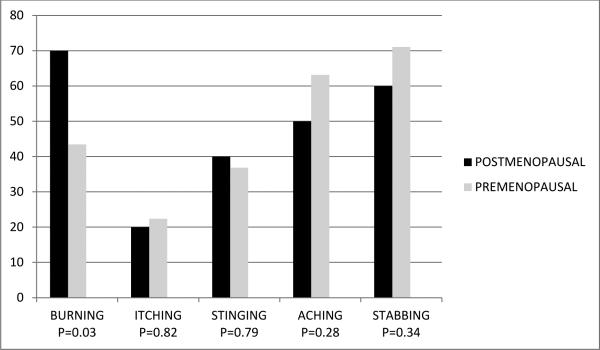

The average ages of premenopausal and postmenopausal women were (30.6 ± 8.6 years) and (54.4 ± 6.5 years), respectively. The groups significantly differed with regard to relationship status (p =.002) and race (p = 0.03), but did not differ in years of education (p = 0.49), income level (p = 0.29) or duration of symptoms (p = 0.09) Post-menopausal women reported significantly more vulvar burning (70.00% vs. 43.42%, p =0. 03), but there were no differences in vulvar itching (20.00% vs. 22.37%, p =0.82), vulvar stinging (40.00% vs. 36.84%, p = 0.79), vulvar aching (50.00% vs. 63.16, p = 0.28), and vulvar stabbing (60.00% vs. 71.06% p = 0.34) or in mean number of symptoms (2. 40 ± 1.0 vs. 2.37 ± 1.4, p = 0.92). Of the 70 subjects completing diaries and meeting tampon insertion pain, there were no significant differences in mean (+/− SD) NRS pain ratings of postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women for tampon insertion (5.66 ± 1.93 vs. 5.83 ± 2.15, p = 0.77), daily vulvar pain (3.20 ± 2.55 vs. 3.83 ± 2.49, p = 0.38) and sexual intercourse (6.00 ± 2.53 vs. 5.98 ± 2.29, p= 0.98).

CONCLUSIONS

Pre- and post-menopausal women with PVD have similar pain scores, and with the exception of a higher incidence of burning in postmenopausal women, similar presenting clinical symptoms. The statistical power of this conclusion is limited by the small number of postmenopausal women in the study. Further research on the vulvar pain experience of the older woman with PVD is warranted.

Keywords: vulvodynia, presenting symptoms, premenopausal, postmenopausal

INTRODUCTION

Vulvodynia is a chronic pain disorder of the vulva, defined as “a vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain, occurring in the absence of relevant findings or a specific clinically identified neurologic disorder. “The International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease (ISSVD) classifies vulvodynia as generalized (involving the entire or large portions of the area between the mons and anus) or localized (involving a defined area, such as the vestibule or clitoris). Each may be further subdivided into provoked (pain with contact, such as tampon insertion or intercourse), unprovoked (continuous pain present without contact) or both. (1) Vulvodynia may also present as stinging, irritation, itching, pain or rawness. Provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), the most common form of vulvodynia, is pain with contact to the area immediately anterior to the hymenal ring, known as the vestibule.

Vulvodynia is estimated to affect 8 – 15% of women (2, 3, 4,) and one report described this pain syndrome as the leading cause of dyspareunia in women under the age of fifty. (5) Vulvodynia, however, has been diagnosed across the lifespan of women. A recent population-based telephone survey of 2269 women reported a weighted vulvodynia incidence of 8%, which remained stable until the age of 70, after which it declined. (6). In this study, peri- and post-menopausal women reported pain symptoms at a similar rate irrespective of hormone therapy, suggesting symptoms may not have been directly cause by estrogen loss changes, and women after the age of 70 had no decline in prevalence compared to younger women when those women who had had intercourse in the last 6 months were evaluated separately.

Despite these studies which evaluate the incidence of vulvodynia in peri- and post- menopausal women, little data exist which compare the symptoms of vulvodynia in this population with premenopausal women. It has been postulated that the overlap of symptoms of vulvodynia with the symptoms associated with the genitourinary syndrome of menopause leads to under-diagnosis and subsequent inadequate treatment of vulvodynia in the hormone deficient woman. (7)

Our objective was to determine whether there were differences in the clinical presentation of symptoms and vulvar pain ratings in affected postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) enrolled in a clinical trial.

METHODS

Questionnaire data was collected from women enrolled between August 2011 and October 2014 in a multi-site, NIH-funded, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of extended release gabapentin in the treatment of PVD. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all three study sites, the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, and the University of Rochester Medical Center. Women were enrolled in the study if they were over the age of 18 years old, had greater than 3 continuous months of insertional dyspareunia, pain to touch, or both with tampon insertion, modified Freidrich's Criteria for vulvodynia (8), and demonstrated an average of “4” or greater on the 11-point tampon test (10) (0=no pain at all; 10 = worse pain ever) recorded in electronic diaries over the 2-week screening period.

Modified Freidrich's criteria was fulfilled if the woman; (1) reported greater than 3 continuous months of vulvar symptoms including insertional dyspareunia, pain with tampon insertion or pain to touch (2) demonstrated on physical exam moderate to severe tenderness to touch, localized to the vulvar vestibule, and (3) demonstrated absent or variable degrees of erythema of the vestibule. The 11 – point tampon test is a self-report pain scale caused by pain with tampon insertion, shown to be valid and reliable in the diagnosis and monitoring of provoked vestibulodynia. (9)

Exclusion criteria included: (1) other vulvar conditions or active infections identified clinically or by a positive Affirm test (VPIII microbial identification test), (2) a prior vestibulectomy, (3) pregnant or at risk for pregnancy and not using a reliable contraceptive for 3 months prior to and during the study (4) a major medical or psychiatric condition, including substance abuse, (5) a score of greater than or equal to ≥ 12 on the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), indicating a major depressive episode (10), (6) use of centrally-acting medications, excluding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and (7) use of topical lidocaine.

At the screening visit, a self-administered questionnaire collected detailed demographic data and a complete medical and gynecological history, including current medications. Menopausal status was self-reported. A visual inspection of the vulva, speculum exam and bimanual pelvic exam was performed. A cotton swab test was used to clinically confirm PVD, an Affirm test collected, and a vaginal swab obtained for Rakoff stain evaluation to determine vaginal estrogen status. (18) If the Affirm test was positive for yeast, Gardenerella or trichomonas, the woman was treated and re-screened. Women with Rakoff stain showing greater than 10% parabasal cells were treated with local estrogen, if appropriate, and rescreened after 6 weeks. Women continued the 2 week screening phase only after a negative Affirm test and a Rakoff with less than 10% parabasal cells was demonstrated.

Women completed a standardized questionnaire at baseline describing their vulvar symptoms and rated daily pain on a visual analogue scale (0 = no pain to 10 = worse pain imaginable) from sexual intercourse, tampon insertion (as a surrogate measure of intercourse) and 24-hour vulvar pain during a 2 week screening period using an electronic diary. Pre-treatment data were analyzed prior to pharmacologic intervention. Chi-Square was used to determine differences between pre- and postmenopausal women in demographic characteristics and clinical presentation, and independent t-tests were used to analyze pain ratings by (0-10) numeric rating scale (NRS).

RESULTS

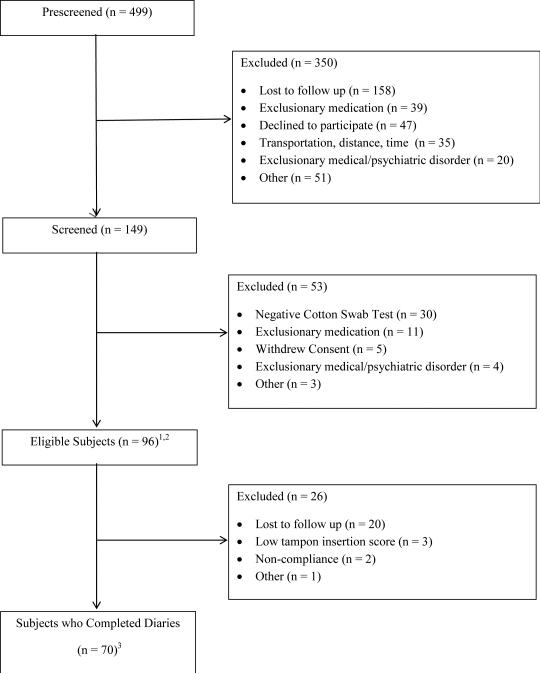

Of the four-hundred ninety-nine women prescreened by a telephone questionnaire,, 149 were screened, 96 were eligible and 70 completed daily diaries during the 2 week screening period. Two subjects had ≥ 10 parabasal cells and vaginal atrophy at screening and entered the study after 6 weeks of topical hormone therapy. Three other subjects were receiving topical hormone therapy at screening. Twenty-five subjects who met all other eligibility criteria had vaginitis (diagnosed either with clinical evaluation or with a positive affirm test) at screening and entered the study after treatment. (Figure 1) The average ages of premenopausal and postmenopausal women were (30.6 ±8.6 years) and (54.4 ± 6.5 years), respectively. The groups did not differ in years of education (p = 0.49), income level (0.29) or duration of symptoms (p =0.09), but postmenopausal women were more likely to be in a partnered relationship (p = .002) and more likely to be white (p = .03) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Symptoms in post-versus pre-menopausal women.

Burning was the only presenting symptom of vulvodynia reported by significantly more post- versus pre-menopausal women.

Subject enrollment flow diagram. 12 subjects had ≥ 10 parabasal cells and vaginal atrophy at screening and entered the study after 6 weeks of topical hormone therapy. Three other subjects were receiving topical hormone therapy at screening. 225 subjects had vaginitis and entered the study after treatment. 3Of the 70 subjects completing diaries, 16 were postmenopausal and 54 were premenopausal. Of the 43 subjects having sexual intercourse, 6 were postmenopausal and 37 were premenopausal.

Postmenopausal women were more likely to report burning (70.00% vs 43.42%, p = 0.03), but there were no significant differences, in vulvar itching (20.00% vs. 22.37%, p =0.82), vulvar stinging (40.00% vs. 36.84%, p = .79), vulvar aching (50.00% vs.63.16%, p = 0.28), vulvar stabbing (60.00% vs. 71.06% p = 0.34) (Figure 2) or in mean number of symptoms (2.40 ± 1.0 vs. 2.37± 1.4, p = 0.92). The percentage of post women who complained of vulvar burning did not differ with respect to use or nonuse of hormone therapy (80.00% vs 70.59%, p = 1.0)

Figure 2. symptoms in post- versus pre-menopausal women.

Mean pain scores post-versus pre-menopausal women. (based on worst pain ever felt, 1-10, 10 being the worst.

There was no difference in severity of symptoms on any recorded measure between post-and pre-menopausal women with vulvodynia.

Of the 70 women completing the 2 week screening diary (54 pre- and 16 post-menopausal)and meeting tampon insertion pain, there were no significant differences in mean (+/− SD) NRS pain ratings of postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women for tampon insertion (5.66 ± 1.93 vs. 5.83 ± 2.15, p = 0.77) or daily vulvar pain (3.19± 2.55 vs. 3.83 ± 2.49, p = 0.38). Of the 43 women reporting sexual intercourse (37 pre- and 6 post-menopausal), there were no differences in pain ratings (6.00 ± 2.53 vs. 5.98 ± 2.29 ± p= 0.98 (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Vulvodynia has been shown to both develop and persist in peri- and post-menopausal women, with incidences reported as high as 15.6% in women over age 65. (11) Studies have also shown similar histopathology between premenopausal and postmenopausal women with vestibulodynia, although the latter had increased lymphocytic infiltration. (12) Despite this interest in post-menopausal vulvodynia, little attention has been paid to the presenting symptoms in this population. Goetsch reported a series of seven postmenopausal women who presented with debilitating vulvar burning, with variable responses to local estrogen therapy, felt to have vulvodynia. (13) Most published demographic data reports primary and presenting symptoms, but does not stratify these symptoms in terms of menopausal status (14, 15, 16, 17) Our data provide a comparison of symptoms of pre- and post-menopausal women identified clinically with PVD who were enrolled in a clinical study. The results suggested that, with the exception of a burning, there is no difference in either type or number of presenting symptoms, daily pain scores or pain with tampon insertion or sexual intercourse in post – menopausal versus pre-menopausal women with PVD.

The reason why vulvar burning was more commonly reported in postmenopausal women is unclear. Chronicity of illness may be a contributing factor because almost 64% of postmenopausal women reported symptom duration of greater than 5 years compared to 49% of premenopausal women (p = .09). However, age was not a significant predictor of burning. Further, infection and other vulvar pathology had been evaluated, with exclusion from the clinical trial if present and untreated.

The question of whether a hypo-estrogenic state could have been the cause of the greater incidence of burning in the post-menopausal population remains unanswered. All women included in the study had a normal maturation index, with less than 10% parabasal cells. Our inclusion of a maturation index as a screening test was to provide an objective uniformity in our sample population, as a measure of vaginal estrogenization, not necessarily to reflect lack of genitourinary symptoms of menopause. However, neither of the 2 women who were placed on local estrogen therapy after identification of an elevated parabasal cell count had symptom improvement or improved cotton swab or 11-point tampon test point scores after parabasal count improved.

It is possible that the more severe chronic inflammation found in postmenopausal tissue (12) may place these women at increased risk for burning, but these relationships have not been explored.

Race should also be considered when interpreting differences in symptoms since race was a significant predictor of burning on multivariate analysis (P < .0001). Future studies should evaluate the effect of race on presenting symptoms as well as pain severity in women with vestibulodynia.

As expected, daily pain was lower than tampon pain insertion and sexual intercourse in both groups, as our population included women with PVD rather than generalized vulvodynia, where pain is most likely to be continuous.

The strength of our data was that it included only women with absence of vulvar disease on visual inspection or infection by Affirm testing. The use of the 11-point tampon test as a surrogate measure of PVD pain with intercourse allowed comparison of pain in both sexually active and inactive women.

Weaknesses of our study include the use of self-report measure for vulvodynia symptoms, rather than an instrument specifically designed to measure pain descriptors, which would have provided more word choices and categories of severity. Menopausal status was also self-reported. Another limitation is lack of uniformity of hormone use. However, only 5 of the 22 women were taking HT, and when the two groups were compared, results did not vary. Additionally, the statistical power of our conclusion is limited by the small number of women in the study. Only burning showed significance. In order to detect the differences for other outcome variables with 80% power at 5% significance level, we would have needed to increase the sample size per group to 161 for aching, and more than 1000 for itching, stinging and stabbing symptoms. To detect a difference of 1 in the 11-point tampon test, we would have needed 67 women in each group; however such a minor decrease would not be considered clinically meaningful. The power necessary to detect these differences was from 0.07 to 0.40.

CONCLUSION

Pre- and post-menopausal women with PVD have similar pain scores, and, with the exception of a higher prevalence of burning in postmenopausal women, similar presenting clinical symptoms. As burning is often the presenting symptom in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause, our study suggests a rigorous clinical evaluation for vulvodynia may be warranted in postmenopausal women in whom treatment of presumed symptoms from atrophy does not alleviate symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grant number R01HD065740 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of Women's Health Research (OWHR), the University of Tennessee General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) and Depomed, Inc. who provided gabapentin extended release and matching placebo for the study. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NICHD, ORWH, GCRC or Depomed, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Bachmann served on an Advisory Board for TEVA Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., which produces a generic equivalent to the study drug, gabapentin, called Neurontin.® No competing financial interests exist for Drs. Phillips, Brown , Foster or Bachour, Rawlison, or Wan.

Bibliography

- 1.Haefner HK. Report of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease terminology and classification of vulvodynia. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2007;11:48–49. doi: 10.1097/01.lgt.0000225898.37090.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: [prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1609–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harlow BL, Stewart E. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia. J Am Women Assoc. 2003;58:82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed BD, Haefner HK, Harlow SD, DW, Sen A. Reliability and Validity of Self-reported symptoms for predicting vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:906–13. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000237102.70485.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meana M, Binik YM, Khalife S, Cohen DR. Biopsychosocial profile of women with dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:583. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)80136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, Legocki LJ, Edwards RM, Arota N, Haefner HK. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips NA, Bachmann GB. Vulvodynia: an often-overlooked cause of dyspareunia in the menopausal population. Menopausal Med. 2010;18(2):S1–S5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freidrich EG. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, Watts BS, Oakes D, Howard FM, Stodgell CJ, Dworkin RH. The tampon test for vulvodynia research: reliability, construct validity, responsiveness. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:825–32. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819bda7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, et al. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:170, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lecaliar CM, Goetsch MF, Li H, Morgan T. Histopathologic characteristics of menopausal vestibulodynia. Obstet & Gynecol. 2013;122(4):787–793. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a5f25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetsch MF. Unprovoked vestibular burning in late estrogen deprived menopause: a case series. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2012;16(4):442–446. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31825c2d28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold LD, Bachmann GA, Rosen R, Rhoads GG. Assessment of vulvodynia symptoms in a sample of US women: a prevalence survey with a nested case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:128. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon A, Panahian-Jand M. Characteristics of women with vulvar pain disorders: Responses to a web-based survey. J Sex Marit Ther. 2003;29:45–58. doi: 10.1080/713847126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlow BL, Vazquez G, MacLehose RF, et al. Self-reported vulvar pain characteristics and their association with clinically confirmed vestibulodynia. J Women's Health. 2009;18:1333–1339. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients: A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:679–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEndree B. Clinical application of the vaginal maturation index. Nurse Pract. 1999;24(9):48–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]