Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) arise from hematopoietic stem cells and develop into a discrete cellular lineage distinct from other leucocytes. Mainly three phenotypically and functionally distinct DC subsets are described in the human peripheral blood (PB): plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), which express the key marker CD303 (BDCA-2), and two myeloid DC subsets (CD1c+ DC (mDC1) and CD141+ DC (mDC2)), which express the key markers CD1c (BDCA-1) and CD141 (BDCA-3), respectively. In addition to these primary cell subsets, DCs can also be generated in vitro from either CD34+ stem/progenitor cells in the presence of Flt3 (Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3) ligand or from CD14+ monocytes (monocyte-derived DCs (mo-DCs)) in the presence of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor+interleukin-4 (GM-CSF+IL-4). Here we compare the reactivity patterns of HLDA10 antibodies (monoclonal antibody (mAb)) with pDCs, CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs, as well as with CD14+-derived mo-DCs cultured for 7 days in the presence of 100 ng/ml GM-CSF plus 20 ng/ml IL-4. A detailed profiling of these DC subsets based on immunophenotyping and multicolour flow cytometry analysis is presented. Using the panel of HLDA10 Workshop mAb, we could verify known targets selectively expressed on discrete DC subsets including CD370 as a selective marker for CD141+ DCs and CD366 as a marker for both myeloid subsets. In addition, vimentin and other markers are heterogeneously expressed on all three subsets, suggesting the existence of so far not identified DC subsets.

Dendritic cells (DCs) form a subset of antigen-presenting cells bridging the adaptive and innate immune system.1 DCs in their immature state are sentinels of the immune system as they patrol in the periphery and continuously take up different kinds of antigens.2 Following uptake, antigens are processed and presented in the form of peptides bound to major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) on the cell surface. Activation of DCs is induced, for example, by microorganisms, infected cells or apoptotic bodies from dying cells.3, 4, 5 After stimulation, immature DCs transform into mature DCs, which is accompanied by the upregulation of surface MHC class II (MHC-II) and costimulatory molecules, leading to exceptional capacity for T-cell stimulation.6

The DC family consists of two main populations called classical DCs and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) located in the blood, peripheral and lymphoid organs and of the nonclassical Langerhans cells located in the epidermis. The latter morphologically resemble plasma cells and produce high amounts of interferon-α upon viral stimulation.7 Human blood DCs constitutively express MHC-II and lack the lineage (Lin) markers CD3, CD19, CD14, CD20, CD56 and glycophorin A. Human pDCs are characterized as Lin−MHC-II+CD303(BDCA-2)+CD304(BDCA-4)+ and do weakly express the integrin CD11c. In contrast, classical DCs are characterized as Lin−MHC-II+CD11c+, although in humans, CD11c is also expressed on most monocytes and macrophages. In humans two classical DC subsets expressing the non-overlapping markers CD1c (BDCA-1) or CD141 (BDCA-3) are present in the blood circulation. CD1c+ DCs (mDC1) represent the predominant DC subset in human blood and are related to mouse CD11b+ DCs, whereas CD141+ DCs (mDC2) related to mouse CD8+ DCs are less abundant.8 Human blood DC subsets differ in their Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression profile: pDC express TLR1, TLR6, TLR7, TLR9 and TLR10; resident CD1c+ DCs express TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6 and TLR8; and resident CD141+ DCs express TLR1, TLR3, TLR6, TLR8 and TLR10.9

Further characterization of CD141+ DCs revealed that they uniquely express the lectin Clec9A,10, 11, 12 the chemokine receptor XCR113, 14 and the transcription factors Batf3 and IRF8.8, 15, 16 Similar to mouse DCs, human blood CD141+ DCs express TLR3. Upon activation with the TLR3 ligand poly(I:C), they are capable of cross-presenting cell-associated and soluble antigens.14, 15, 16 Recently, a study compared the function of human CD141+ and CD1c+ DCs. The subsets differ in their TLR expression profile and production of inflammatory cytokines but produce similar amounts of IL-12p70 and cross-present soluble antigens to CD8+ T cells in response to stimulation with CD40L together with a cytokine mixture.17 However, activated blood CD141+ DCs are more efficient in cross-presenting dead cell-derived antigen. This might be because of their selective expression receptors recognizing necrotic cells such as Clec9A.9 Blood CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs are equally competent for Th1 polarization; however, because of the selective expression of OX40-L, CD141+ DCs appear to be more potent inducers of Th2 cells.18 Thus, functional specialization of DC subsets is ensured by the differential expression of pathogen-recognition receptors in response to pathogens or vaccines.9, 19

Human DCs have been generated in vitro either by culturing CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors in the presence of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and tumour necrosis factor-α, giving rise to dermal DC-like cells,20 or by culturing blood monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4, ending up with dermal-like CD1a+ DCs.21, 22 Recently, both pDCs and BDCA-3+ and BDCA-1+ cDCs could be generated by culturing CD34+ progenitors in the presence of Flt3 (Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3) ligand and thrombopoietin.15, 23 Here we tested the reactivity patterns of 85 antibodies (Abs) submitted to the HLDA10 Workshop in Wollongong, Australia, in a blind study with human blood-derived pDCs, CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs, as well as with in vitro generated CD14+-derived mo-DCs (monocyte-derived DCs).

RESULTS

Profiling of primary peripheral blood-derived DCs with HLDA10 Abs

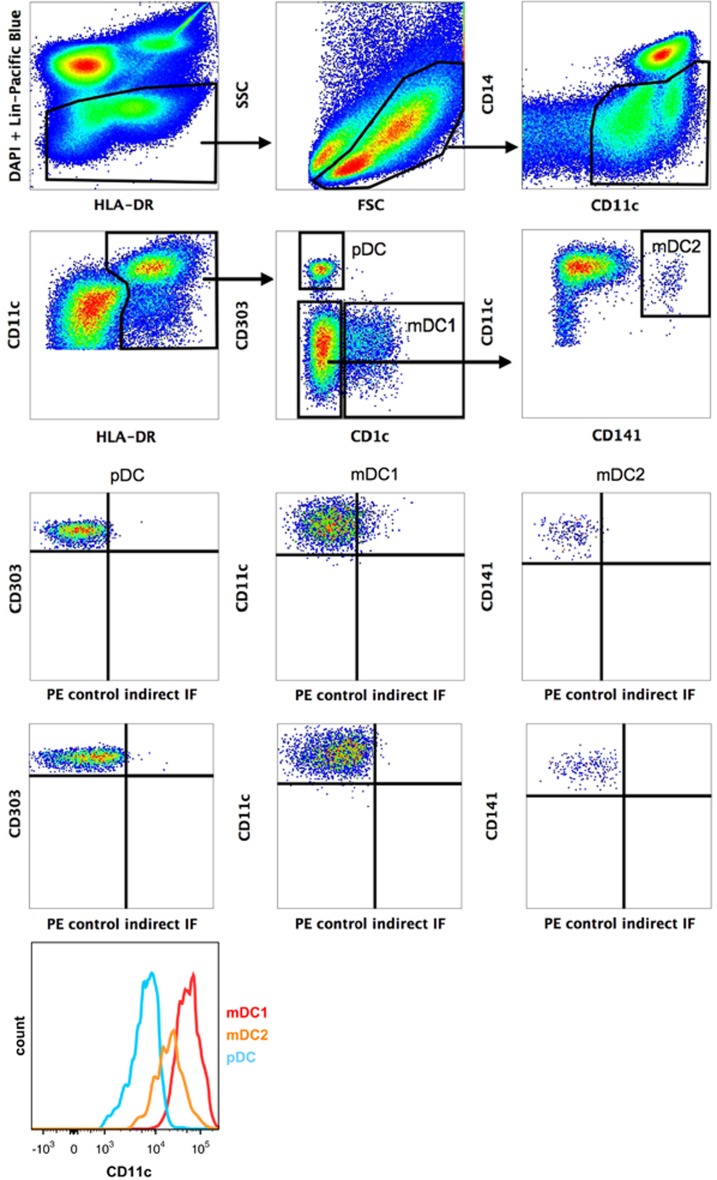

Ficoll-isolated mononuclear peripheral blood (PB) cells from healthy donors were stained with Abs against the Lin markers CD3, CD19 and CD56, as well as with HLA-DR, CD14, CD11c, CD141, CD1c, CD303 and the indicated workshop Abs (Table 1). pDCs and two distinct myeloid DCs (CD1c+ DCs, CD141+ DCs) were defined by multicolour immunofluorescence according to the flow cytometry gate setting strategy shown in Figure 1. All DC subsets are characterized by the absence of the Lin markers and CD14 and the presence of HLA-DR and CD11c. mDC2 were additionally selected by their absence of CD1c. Based on this multigating strategy, pDCs express the key marker CD303 (BDCA-2), whereas the myeloid DC subsets express the key markers CD1c (BDCA-1) and CD141 (BDCA-3). As demonstrated in Figure 1, mDC1 and mDC2 express high or medium levels of CD11c, respectively, whereas CD11c is only weakly expressed by pDC.

Table 1. Reactivity of workshop mAb with cells of the indicated DC subsets.

| Antibody (antigen) | Clone | pDC | CD1c+DC | CD141+DC | Antibody (antigen) | Clone | pDC | CD1c+DC | CD141+DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-01 (CD369) | GE2 | − | − | − | 10-45 (CD370) | FAB6049P | − | − | + |

| 10-02 (CD370) | 8F9 | − | − | + | 10-47 (FPR1) | FAB3744P | − | − | − |

| 10-03 (CD1a) | 010e | − | − | − | 10-48 (CD245) | DY35 | ± | ± | ± |

| 10-04 (LPAP) | CL3 | − | − | − | 10-50 (Axl) | FAB154P | − | − | − |

| 10-06 (CLEC2D) | FAB3480P | − | − | − | 10-51 (CD371) | FAB2946P | Sub-pop | + | + |

| 10-07 (Trem-2) | FAB17291P | − | − | − | 10-52 (ULBP-3) | FAB1517P | − | − | − |

| 10-08 (FAT1 Cad) | FMU-FAT-6 | − | − | − | 10-53 (IL-1RAcP) | AY19 | − | + | ± |

| 10-09 (CD370) | 9A11 | − | − | + | 10-54 (CLEC13A) | FAB637P | − | − | − |

| 10-10 (CD1a) | 0619 | − | − | − | 10-55 (vimentin) | SC5 | Sub-pop | Sub-pop | Sub-pop |

| 10-11 (LPAP) | CL4 | − | − | − | 10-56 (Tie-2) | FAB3131P | − | − | − |

| 10-12 (CD276) | 58B1 | − | − | − | 10-57 (CLEC14A) | FAB7436P | − | − | − |

| 10-13 (CD367) | FAB1748P | + | + | ± | 10-59 (unknown) | MDR64 | − | − | − |

| 10-15 (CD135, Flt3) | FAB812P | + | + | + | 10-61 (CD273) | ANC8D12 | − | − | − |

| 10-16 (FAT1 Cad) | FMU-FAT1-7 | − | − | − | 10-62 (GARP) | ANC8C9 | − | − | − |

| 10-17 (CD371) | HB3 | + | + | + | 10-63 (GARP) | ANC10G10 | − | − | − |

| 10-18 (CD1b) | O249 | − | ± | − | 10-64 (B7-H4) | MIH43 | − | − | − |

| 10-19 (LPAP) | CL7 | − | − | − | 10-65 (CD370) | 8F9 | − | − | + |

| 10-21 (CD368) | FAB2806P | − | − | − | 10-66 (CD85g) | 17G10.2 | − | − | − |

| 10-23 (calreticulin) | FMU-CRT-2 | − | − | − | 10-67 (CD365) | 1D12 | − | − | − |

| 10-24 (CD366) | FAB2365P | − | + | + | 10-68 (TSLP-R) | 1B4 | − | − | − |

| 10-25 (unknown) | W4A5 | Sub-pop | Sub-pop | Sub-pop | 10-69 (unknown) | CMRF-56 | − | Sub-pop | Sub-pop |

| 10-26 (CD1c) | L161 | − | − | − | 10-70 (P2X7) | L4 | ± | + | ± |

| 10-28 (CLEC5A) | FAB238P | − | − | − | 10-71 (CD367) | 111F8.04 | − | ± | − |

| 10-29 (calreticulin) | FMU-CRT-8 | − | − | − | 10-72 (CD367) | 9E8 | + | + | + |

| 10-30 (IL-13 Ra2) | FMU-IL13RA2-7 | − | Sub-pop | Sub-pop | 10-73 (CD371) | 50C1 | + | + | + |

| 10-31 (CLEC5C) | FAB1900P | − | − | − | 10-74 (CD85h) | 24 | − | + | + |

| 10-32 (unknown) | W5C4 | − | − | − | 10-75 (CD366) | F38-2E2 | − | + | + |

| 10-34 (CD101) | BB27 | − | + | + | 10-76 (CCR5) | HEK/1/85 | + | + | ± |

| 10-35 (CD369) | FAB1859P | − | − | ± | 10-77 (DORA) | 104A10.01 | − | − | − |

| 10-36 (FPRL1) | FAB3479P | − | − | − | 10-78 (CD368) | 9B9 | + | + | + |

| 10-37 (IL-13 Ra2) | FMU-IL13RA2-8 | − | − | − | 10-79 (CD369) | 15 E 2 | ± | + | + |

| 10-38 (unknown) | BGA69 | − | − | − | 10-80 (MAIR II) | TX45 | ± | + | ± |

| 10-39 (unknown) | F9-3C2 | − | − | − | 10-81 (Tim-4) | 9F4 | + | + | + |

| 10-40 (CLEC8A) | FAB1798P | − | − | − | 10-82 (unknown) | CMRF-44 | − | − | − |

| 10-41 (IL-13 Ra2) | FMU-IL13RA2-14 | − | − | − | 10-83 (DCSIGN like) | 118A8.05 | − | − | − |

| 10-42 (calreticulin) | FMU-CRT-17 | − | − | − | 10-84 (FDFO3) | 36H2 | − | ± | − |

| 10-43 (CD245) | DY12 | + | + | ± | 10-85 (TetanusT) | CMRF-81 | − | − | − |

| 58B3 (unknown) | + | + | + |

Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; mAb, monoclonal antibody; sub-pop., indicates positive signal on a sub-population of the analysed DC subset; ±, indicates that positive signals are close to background signals and cannot be interpreted as positive or negative signals because of the unspecific background staining caused by some of the antibodies.

Figure 1.

Gating strategy to identify pDC, CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs after staining of PBMCs with the indicated Abs. Five hundred thousand stained PBMCs were analysed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (Heidelberg, Germany) and sequential gating was performed using the FlowJo software. DC subsets were identified as pDCs: lin− (CD3, CD19, CD56) CD14−CD11cdimHLA-DR+CD1c−CD303+, CD1c+ DCs: lin− (CD3, CD19, CD56) CD14−CD11c+HLA-DR+CD1c+CD303− and CD141+ DCs: lin− (CD3, CD19, CD56) CD14−CD11c+HLA-DR+CD1c−CD303−CD141+.

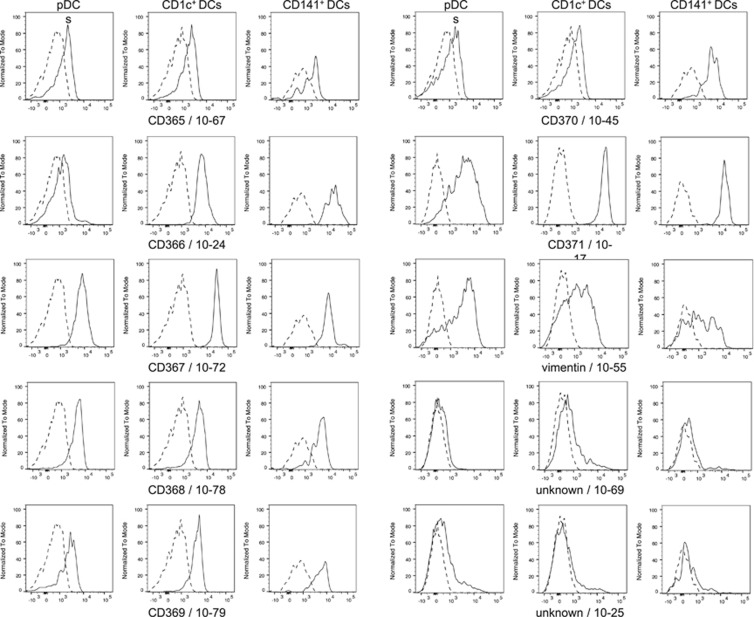

For profiling of DC subsets with workshop Abs, plots of CD1c, CD141 or CD303 versus the selected monoclonal antibody (mAb)-defined antigens were compared with the corresponding controls. In Figure 2 the reactivity profiles of the selected mAb are shown. The profiles demonstrate that CD370 (CLEC9A/DNGR-1) is almost exclusively expressed on CD141+ DCs, whereas CD366 (Tim-3) and CD101 (Table 1) expression is restricted to both myeloid DC subsets, and CD371 (CLEC12A, CLL, MICL) is expressed on all three DC subsets. IL-13-Ra2 and vimentin, as well as two Ab-defined antigens of unknown targets, show heterogeneous reactivity profiles on either the two myeloid DC subsets (10-30/IL-13-Ra2/clone FMU-IL-13RA2-7 and 10-69/clone CMRF-56) or on all three DC subsets (10-55/vimentin/clone SC5 and 10-25/clone W4A5) (Table 1). This suggests that all three DC populations contain additional subsets with probably unknown function.

Figure 2.

Stained PBMCs were used to demonstrate the reactivity of selected Abs with pDC, CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs, respectively. Plots show histogram overlays of specific HDLA-10 Ab staining (solid line) and control staining (dotted line). Note that Ab 10-45 recognize CD141+ DCs but not the other DC subsets, and that Abs 10-55, 10-69 and W4A5 show heterogeneous reactivity patterns.

Of the new clustered molecules at the HLDA10 conference, CD365 (TIM-1) is not expressed on primary DCs and weak CD368 (CLEC4D, Dectin-3) expression on these cells is only verified by one of two submitted Abs (positive with clone 9B9 (10-78), but not with clone FAB2806P (10-21)). CD367 (CLEC4A, DCIR) and CD369 (CLEC7A, Dectin-1) are weakly expressed on all DC subsets shown by staining with two out of three CD367-reactive Abs (clones FAB1748P (10-13) and 9E8 (10-72)). In contrast, anti-CD369 Abs showed clone-dependent reactivity patterns to peripheral blood DCs. Clone GE2 was not reactive to all three analysed DC populations, whereas clone FAB1859P (10-35) interacted weakly with CD141+ DCs and clone 15E2 (10-79) weakly with pDCs, CD1c+ and CD141+ DCs; Table 1). The reactivity profiles of all available workshop mAbs to DC subsets are summarized in Table 1.

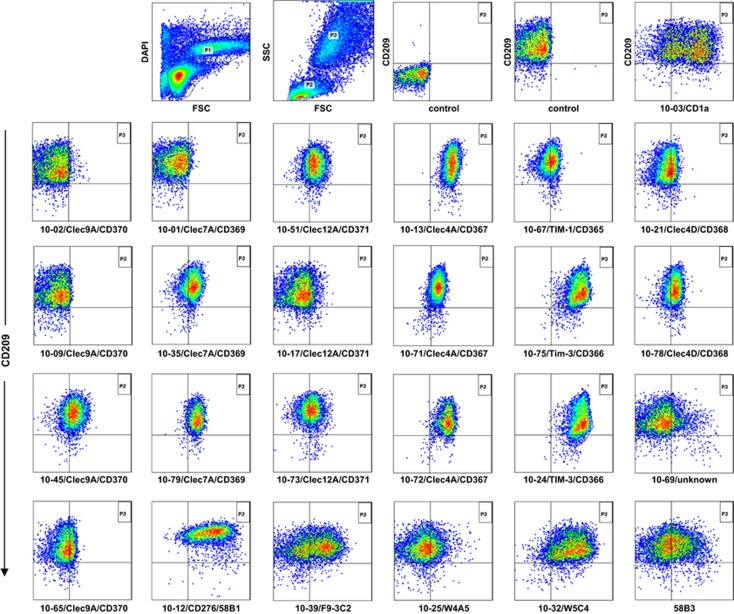

Profiling of mo-DCs with HLDA10 Abs

Workshop mAbs were additionally analysed for their recognition of mo-DCs, which were obtained after culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for 7 days in the presence of 100 ng ml−1 GM-CSF and 20 ng ml−1 IL-4. After culture, cells were double-stained with anti-CD209 (DC-SIGN)-APC and the indicated workshop Abs and analysed by flow cytometry. Figure 3 shows that cultured DCs reside in the ‘monocyte' gate in the dual scatter plot, which was verified by their expression of CD209.24 After gating, cells were analysed by plotting CD209 versus workshop mAb and compared with appropriate controls. The reactivity patterns of selected mAb with CD209+ DCs are shown in Figure 3. The complete set of new CD molecules clustered at the HLDA10 conference (CD365-371) is expressed on mo-DCs at varying intensity. However, some Abs such as 10-1 (CD369), 10-2 (CD370) and 10-17 (CD371) did not recognize the epitopes on mo-DCs, although other workshop mAbs against these molecules showed a positive staining on these cells. Several Abs reacted with cultured but not with primary DCs. Among these, mAb against CD273 and CD276, as well as the Ab-defined antigens 58B3, F9-3C2 (10-39), W4A5 (10-25) and W5C4 (10-32) show unique reactivity patterns (Figure 3). In particular, mAb 10-61 (CD273), mAb 10-69 (CMRF-56), mAb 10-39 (F9-3C2) and mAb 10-25 (W4A5) give rise to heterogeneous reactivity patterns, suggesting that cultured DCs do not consist of a homogeneous cell population. The reactivity profiles on mo-DC of all available workshop mAb are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Staining of mo-DC with CD209-APC and workshop Abs. Hundred thousand stained cells were analysed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer and gating (P1+P3) was performed using the FlowJo software. CD209 was used as a key marker to identify cultured DCs.

Table 2. Reactivity of workshop mAb with mo-DC.

| Antibody (antigen) | Clone | Mo-DC | Antibody (antigen) | Clone | Mo-DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-01 (CD369) | GE2 | − | 10-45 (CD370) | FAB6049P | + |

| 10-02 (CD370) | 8F9 | − | 10-47 (FPR1) | FAB3744P | + |

| 10-03 (CD1a) | 010e | Sub-pop. | 10-48 (CD245) | DY35 | + |

| 10-04 (LPAP) | CL3 | − | 10-50 (Axl) | FAB154P | − |

| 10-06 (CLEC2D) | FAB3480P | + | 10-51 (CD371) | FAB2946P | + |

| 10-07 (Trem-2) | FAB17291P | + | 10-52 (ULBP-3) | FAB1517P | + |

| 10-08 (FAT1 Cad) | FMU-FAT-6 | − | 10-53 (IL-1RAcP) | AY19 | + |

| 10-09 (CD370) | 9A11 | − | 10-54 (CLEC13A) | FAB637P | ± |

| 10-10 (CD1a) | 0619 | Sub-pop. | 10-55 (vimentin) | SC5 | ± |

| 10-11 (LPAP) | CL4 | − | 10-56 (Tie-2) | FAB3131P | + |

| 10-12 58B1 (CD276) | FAB1748P | + | 10-57 (CLEC14A) | FAB7436P | + |

| 10-13 (CD367) | FAB1750P | + | 10-59 (unknown) | MDR64 | − |

| 10-15 (CD135, Flt3) | FAB812P | ± | 10-61 (CD273) | ANC8D12 | + |

| 10-16 (FAT1 Cad) | FMU-FAT1-7 | − | 10-62 (GARP) | ANC8C9 | − |

| 10-17 (CD371) | HB3 | ± | 10-63 (GARP) | ANC10G10 | − |

| 10-18 (CD1b) | O249 | + | 10-64 (B7-H4) | MIH43 | − |

| 10-19 (LPAP) | CL7 | − | 10-65 (CD370) | 8F9 | ± |

| 10-21 (CD368) | FAB2806P | ± | 10-66 (CD85g) | 17G10.2 | ± |

| 10-23 (calreticulin) | FMU-CRT-2 | − | 10-67 (CD365) | 1D12 | + |

| 10-24 (CD366) | FAB2365P | + | 10-68 (TSLP-R) | 1B4 | − |

| 10-25 (unknown) | W4A5 | + | 10-69 (unknown) | CMRF-56 | Sub-pop |

| 10-26 (CD1c) | L161 | + | 10-70 (P2X7) | L4 | − |

| 10-28 (CLEC5A) | FAB238P | − | 10-71 (CD367) | 111F8.04 | + |

| 10-29 (calreticulin) | FMU-CRT-8 | − | 10-72 (CD367) | 9E8 | + |

| 10-30 (IL-13 Ra2) | FMU-IL13RA2-7 | − | 10-73 (CD371) | 50C1 | + |

| 10-31 (CLEC5C) | FAB1900P | − | 10-74 (CD85h) | 24 | + |

| 10-32 (unknown) | W5C4 | + | 10-75 (CD366) | F38-2E2 | + |

| 10-34 (CD101) | BB27 | − | 10-76 (CCR5) | HEK/1/85 | + |

| 10-35 (CD369) | FAB1859P | + | 10-77 (DORA) | 104A10.01 | − |

| 10-36 (FPRL1) | FAB3479P | + | 10-78 (CD368) | 9B9 | + |

| 10-37 (IL-13 Ra2) | FMU-IL13RA2-8 | − | 10-79 (CD369) | 15 E 2 | + |

| 10-38 (unknown) | BGA69 | ± | 10-80 (MAIR II) | TX45 | + |

| 10-39 (unknown) | F9-3C2 | Sub-pop. | 10-81 (Tim-4) | 9F4 | + |

| 10-40 (CLEC8A) | FAB1798P | + | 10-82 (unknown) | CMRF-44 | − |

| 10-41 (IL-13 Ra2) | FMU-IL13RA2-14 | − | 10-83 (DCSIGN like) | 118A8.05 | + |

| 10-42 (calreticulin) | FMU-CRT-17 | − | 10-84 (FDFO3) | 36H2 | ± |

| 10-43 (CD245) | DY12 | + | 10-85 (TetanusT) | CMRF-81 | − |

| 58B3 (unknown) | + |

Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; mAb, monoclonal antibody; mo-DC, monocyte-derived DC; sub-pop., indicates positive signal on a sub-population of the analysed Mo-DCs; ±, indicates that positive signals are close to background signals and cannot be interpreted as positive or negative signals because of the unspecific background staining caused by some of the antibodies.

Discussion

We screened Abs submitted from different providers to the HLDA10 workshop in Wollongong, Australia, for their reactivity with primary human blood DC subsets as well as with in vitro generated mo-DCs. The Abs were either purified, delivered as ascites or directly conjugated with FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) or PE (phycoerythrin) and assigned to consecutive numbers.

Two new Abs cluster to single-span class-1 transmembrane proteins, namely CD365 (Tim-1) and CD366 (Tim-3). Both proteins are expressed on activated CD4+ T-helper cells. Tim-3 has a critical role in regulating the activities of T cells, macrophages, monocytes, DCs, mast cells, natural killer cells and endothelial cells.25 Whether these molecules are also expressed on human blood DC subsets was not yet investigated. Here we could show that CD365 is also weakly expressed on primary blood pDCs, CD1c+ and CD141+ DCs, as well as on mo-DCs. In contrast, CD366 is highly expressed on CD1c+ and CD141+ DCs, as well as mo-DCs, but only near to background levels on pDCs. These data are in contrast to a recent study showing no CD366 expression on mo-DCs from healthy volunteers or patients with different tumours, whereas tumour-associated CD11c+ DCs express high levels of CD366.26 This study did not discriminate between different subsets of tumour-associated CD11c+ DCs nor analysed peripheral blood DCs.26

We could show that all four HLDA10 Abs generated against CD370 (CLEC9A) specifically recognize CD141+ DCs, although Abs 10-45 and 10-65 weakly reacted with pDCs, CD1c+ DCs and in vitro generated mo-DCs. CD370 functions as an endocytic receptor specific for the uptake of degraded components from dead cells16 and is specifically expressed by CD141+ DCs.11, 15, 16, 27 The reasons for the occasionally decreased performance of workshop Abs can be several: First, Abs were shipped under non-dry ice conditions. Second, the quality of Abs varied considerably, some were shipped as purified, some as culture supernatant, some as ascites fluid and others as FITC or PE conjugates. Third, many Abs could be visualized only by indirect staining in combination with multicolour immunofluorescence analysis. As a result, the weaker binding of Abs 10-45 and 10-65 compared with 10-02 and 10-09 can be explained by these reasons. This is of particular evidence with regard to Abs 10-02 and 10-65, as these reagents are derived from the same clone. And finally, different epitopes of the same molecule could be differentially expressed on the cell surface of primary and cultured DCs, resulting in a differential recognition of molecules by Abs with the same molecule specificity.

CD369 (CLEC7A/Dectin-1) is an another pattern recognition receptor specific for β-glucans, components of pathogenic bacteria and fungi and is expressed on DCs.28, 29 We could validate that the submitted CD370-reactive Abs bind to primary blood CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs, as well as to in vitro generated mo-DCs, but not to pDCs.17 In addition, all submitted Abs against the C-type lectins including CD367 (CLEC4A/DCIR), CD368 (CLEC4D) and CD371 (CLEC12A/MICL) bound to all DC subsets analysed.17 CD367 expression is decreased upon maturation,30 but because of limited amount of Abs provided, we were not able to confirm these findings.

Finally, we identified three Abs recognizing targets that are heterogeneously expressed on all primary blood DC subsets including vimentin, Ab 10-69 and Ab W4A5. Although the latter two targets are not yet identified, they appear to be of particular interest because they are able to subdivide the subsets into either further sub-populations or into defined activation stages. In conclusion, using Abs submitted to the HLDA10 Workshop, we could not only confirm the expression patterns of known DC targets but also expand the knowledge of molecules expressed on DCs by either demonstrating new reactivity patterns of known targets or presenting heterogeneous expression profiles of known and unknown targets on DC subsets.

METHODS

PBMCs and flow cytometry

Peripheral blood was collected from two healthy donors according to the guidelines of the local ethics committee. PBMCs were obtained after Ficoll isolation using the interphase cells. Primary DCs were directly labelled after washing using the following procedures. When fluorochrome-conjugated workshop Abs were available, cells were incubated with a mixture of all Ab conjugates for 30 min at 4 °C. Conjugates consisted of the Lin markers CD3-Pacific Blue (SK7), CD19-Pacific Blue (HlB19) and CD56-Pacific Blue (MEM-188), as well as of anti-HLA-DR-Brilliant Violet 510 (L243), CD14-FITC (M5E2), CD11c-PE-Cy7 (Bu15), CD141-APC (M80), CD1c-APC-Cy7 (L161) and CD303-PerCP-Cy5.5 (201 A) (purchased from BioLegend Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), and of PE-conjugated workshop Abs. After washing with FACS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 0.1% NaN3, 1% bovine serum albumin), cells were additionally stained for 10 min with 3 μm DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)at room temperature (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) for dead cell exclusion and acquired on a FACSCanto II analyser (Heidelberg, Germany). Stored data were analysed using the FlowJo software programme (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). The gating and plotting strategy to define pDC, CD1c+ DCs and CD141+ DCs is shown in Figure 1.

In the case where only non-conjugated workshop Abs were available, cells were first labelled with the workshop Abs. After washing, cells were stained with PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse antisera (Biozol Diagnostica GmbH, Eching, Germany). In the next step, cells were incubated with ‘non-reacting' mouse Ab (Biozol Diagnostica GmbH) to block free binding sites of the secondary-step reagent. In the final step, cells were incubated with the commercially available Ab conjugates.

Generation of mo-DCs

For generation of mo-DCs, monocytes were purified by plastic adherence of PBMCs. For this purpose, cells were seeded (1 × 108/10 ml) into 75 cm2 cell culture flasks (Corning, Cambridge, MA, USA) in serum-free X-VIVO 20 medium (Cambrex Bio Science, Verviers, Belgium). After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C/5% CO2, non-adherent cells were removed. The monocytes were cultured in 10 ml RP10 medium (RPMI-1640 with glutamax-I), supplemented with 10% inactivated foetal calf serum and antibiotics (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). GM-CSF (100 ng ml−1; Leukine Liquid Sargramostim; Sanofi, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) and IL-4 (20 ng ml−1; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) were added every second day for 7 days. After culture, cells were trypsinized and the reaction was blocked with culture medium. After washing two times with FACS buffer, cells were stained with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD209 Ab (DCN46; BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and the indicated workshop Abs using the protocol described above. CD209 was used as the key marker to define mo-DCs.24

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Manina Günter for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, SFB 685 Immunotherapy: Molecular Basis and Clinical Application, Projects Z5: Immunomonitoring (to CG, SG and HJB) and A3 (to SEA): Evasion and exploitation of innate and adaptive immunity by Staphylococcus aureus and the European Social Fund of Baden-Württemberg (to SMR and SEA).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature 2007; 449: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu Y-J et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18: 767–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Théry C, Amigorena S. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2002; 20: 621–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen presentation in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol 2005; 23: 975–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P. Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7: 543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6: 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Reizis B, Bunin A, Ghosh HS, Lewis KL, Sisirak V. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: recent progress and open questions. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29: 163–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Robbins SH, Walzer T, Dembélé D, Thibault C, Defays A, Bessou G et al. Novel insights into the relationships between dendritic cell subsets in human and mouse revealed by genome-wide expression profiling. Genome Biol 2008; 9: R17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Durand M, Segura E. The known unknowns of the human dendritic cell network. Front Immun 2015; 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Sancho D, Mourão-Sá D, Joffre OP, Schulz O, Rogers NC, Pennington DJ et al. Tumor therapy in mice via antigen targeting to a novel, DC-restricted C-type lectin. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 2098–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Huysamen C, Willment JA, Dennehy KM, Brown GD. CLEC9A is a novel activation C-type lectin-like receptor expressed on BDCA3+ dendritic cells and a subset of monocytes. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 16693–16701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Caminschi I, Proietto AI, Ahmet F, Kitsoulis S, Shin Teh J, Lo JCY et al. The dendritic cell subtype-restricted C-type lectin Clec9A is a target for vaccine enhancement. Blood 2008; 112: 3264–3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Bachem A, GUttler S, Hartung E, Ebstein F, Schaefer M, Tannert A et al. Superior antigen cross-presentation and XCR1 expression define human CD11c+CD141+ cells as homologues of mouse CD8+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2010; 207: 1273–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Crozat K, Guiton R, Contreras V, Feuillet V, Dutertre C-A, Ventre E et al. The XC chemokine receptor 1 is a conserved selective marker of mammalian cells homologous to mouse CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2010; 207: 1283–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Poulin LF, Salio M, Griessinger E, Anjos-Afonso F, Craciun L, Chen J-L et al. Characterization of human DNGR-1+ BDCA3+ leukocytes as putative equivalents of mouse CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2010; 207: 1261–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Jongbloed SL, Kassianos AJ, McDonald KJ, Clark GJ, Ju X, Angel CE et al. Human CD141+ (BDCA-3)+ dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. J Exp Med 2010; 207: 1247–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Mittag D, Proietto AI, Loudovaris T, Mannering SI, Vremec D, Shortman K et al. Human dendritic cell subsets from spleen and blood are similar in phenotype and function but modified by donor health status. J Immunol 2011; 186: 6207–6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Yu CI, Becker C, Metang P, Marches F, Wang Y, Toshiyuki H et al. Human CD141+ dendritic cells induce CD4+ T cells to produce type 2 cytokines. J Immunol 2014; 193: 4335–4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Jin JO, Zhang W, Du JY, Yu Q. BDCA1-positive dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique human myeloid DC subset that induces innate and adaptive immune responses to Staphylococcus aureus infection. Infect Immun 2014; 82: 4466–4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. GM-CSF and TNF-alpha cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature 1992; 360: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med 1994; 179: 1109–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as the terminal stage of monocyte differentiation. J Immunol 1998; 160: 4587–4595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Chen W, Antonenko S, Sederstrom JM, Liang X, Chan ASH, Kanzler H et al. Thrombopoietin cooperates with FLT3-ligand in the generation of plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors from human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood 2004; 103: 2547–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y et al. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell 2000; 100: 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Han D, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Dang NN, Kim YF, Kim J et al. Dendritic cell expression of the signaling molecule TRAF6 is critical for gut microbiota-dependent immune tolerance. Immunity 2013; 38: 1211–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Chiba S, Baghdadi M, Akiba H, Yoshiyama H, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H et al. Tumor-infiltrating DCs suppress nucleic acid–mediated innate immune responses through interactions between the receptor TIM-3 and the alarmin HMGB1. Nat Immunol 2012; 13: 832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Sancho D, Joffre OP, Keller AM, Rogers NC, Martínez D, Hernanz-Falcón P et al. Identification of a dendritic cell receptor that couples sensing of necrosis to immunity. Nature 2009; 458: 899–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Ni L, Gayet I, Zurawski S, Duluc D, Flamar AL, Li XH et al. Concomitant activation and antigen uptake via human Dectin-1 results in potent antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol 2010; 185: 3504–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Willment JA, Marshall ASJ, Reid DM, Williams DL, Wong SYC, Gordon S et al. The human beta-glucan receptor is widely expressed and functionally equivalent to murine Dectin-1 on primary cells. Eur J Immunol 2005; 35: 1539–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Klechevsky E, Flamar A-L, Cao Y, Blanck J-P, Liu M, O'Bar A et al. Cross-priming CD8+ T cells by targeting antigens to human dendritic cells through DCIR. Blood 2010; 116: 1685–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]