Abstract

Patients with schizophrenia present with deficits in specific areas of cognition. These are quantifiable by neuropsychological testing and can be clinically observable as negative signs. Concomitantly, they self-administer nicotine in the form of cigarette smoking. Nicotine dependence is more prevalent in this patient population when compared to other psychiatric conditions or to non-mentally ill people. The target for nicotine is the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR). There is ample evidence that these receptors are involved in normal cognitive operations within the brain. This review describes neuronal nAChR structure and function, focusing on both cholinergic agonist-induced nAChR desensitization and nAChR up-regulation. The several mechanisms proposed for the nAChR up-regulation are examined in detail. Desensitization and up-regulation of nAChRs may be relevant to the physiopathology of schizophrenia. The participation of several subtypes of neuronal nAChRs in the cognitive processing of non-mentally ill persons and schizophrenic patients is reviewed. The role of smoking is then examined as a possible cognitive remediator in this psychiatric condition. Finally, pharmacological strategies focused on neuronal nAChRs are discussed as possible therapeutic avenues that may ameliorate the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Nicotinic receptors

Introduction

Persons with schizophrenia present with alogia, avolition, apathy, anhedonia, asociality, flattening of affect, attentional deficits, decreased spontaneous movements, and clinically observable neurological signs. These signs, classically termed negative, may co-exist with classical positive symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations.

It is now recognized that these signs are directly correlated with profound cognitive deficits and that they represent the core feature of schizophrenia (Heinrichs and Zakzanis 1998; Elvevag and Goldberg 2000; Kuperberg and Heckers 2000; O’Leary et al. 2000; Friedman et al. 2001).

Several cognitive operations within the brain are a function of intact neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (neuronal nAChRs) localized in discrete neuroanatomical pathways (Levin and Simon 1998; Levin and Rezvani 2002; Levin et al. 2005, 2006). Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type offers a patent example of the correlation between profound cognitive impairment and impaired neuronal nAChR function (Perry et al. 2000). Hence, this review will focus on the evidence that links nAChR function and the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia.

In the first section the structure, localization, and function of neuronal nAChRs will be discussed. Then, the paradoxical phenomenon of nicotine-induced neuronal nAChR up-regulation will be described. This is particularly important since schizophrenic patients who smoke do not exhibit this phenomenon (Breese et al. 2000).

After establishing the basic science background, the possible participation of diverse neuronal nAChR subtypes in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia will be discussed. The emphasis will be on two receptor subtypes: the α7-nAChR subtype which is known to be implied in the pathophysiology of attentional deficits of schizophrenia (Freedman et al. 1996, 1997; Olincy et al. 2006) and in the α4β2-nAChR subtype. This is the most abundant subtype in the brain, and is preferentially activated, desensitized, and up-regulated by nicotine (Flores et al. 1992; Ochoa 1994; Vibat et al. 1995).

The importance of the α4β2-nAChR will be underscored by describing current therapeutic strategies that target this receptor subtype: varenicline, a α4β2-nAChR partial agonist recently approved by the FDA for smoking cessation (Coe et al. 2005a, b) and by allosteric potentiators of the nAChR such as galantamine (Albuquerque et al. 2001; Maelicke et al. 2001; Pereira et al. 2002; Santos et al. 2002). Galantamine has been already used to ameliorate alogia and the attentional and memory deficits of schizophrenic patients (Allen and McEvoy 2002; Rosse and Deutsch 2002; Ochoa and Clark 2004; Bora et al. 2005; Ochoa and Clark 2006; Schubert et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2007).

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

The nAChRs are ligand-gated cation channels that belong to a gene super family of homologous receptors that includes the NMDA receptor, the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, the glycine receptor, and the 5-HT3 serotonin receptor (Sargent 1993; Karlin and Akabas 1995). nAChRs are known as Cys-loop receptors due to the presence of a conserved sequence containing a pair of cysteines separated by 13 amino acid residues and linked by a disulfide bridge (Hogg et al. 2003). The nAChR has been proposed as a model of an allosteric protein in which effects initiated from the binding of a ligand to a site on the receptor can lead to structural changes in another part of the molecule. When an agonist molecule, such as ACh, binds to the nAChR it produces an allosteric transition that allows the channel to go from the closed to an open state, thus permitting the flow of sodium and potassium cations through the channel pore (Changeux and Edelstein 2005). Nicotinic AChRs are divided into two classes: muscle and neuronal receptors.

Cholinergic pathways have been implied as participating in the physiopathology of schizophrenia (for a recent review see Berman et al. 2007). Furthermore, neuronal nAChRs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of some deficits seen in schizophrenic patients (Freedman et al. 1994). Clinically, this concept is supported by the high prevalence of smoking among these patients (de Leon et al. 1995; DeLeon et al. 1995; Stassen et al. 2000) and by the amelioration effected by nicotine and its agonists of some of the neurophysiological deficits exhibited in this disorder (Levin and Rezvani 2002; Harris et al. 2004).

Neuronal nAChRs

Neuronal nAChRs are distributed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems. In contrast with their muscle counterparts, they serve more of a modulatory function in synaptic transmission (Role and Berg 1996; Wonnacott 1997). Elucidation of the functional and structural characteristics of neuronal nAChRs started later due to their lower concentrations in more heterogeneous tissues (Lindstrom 1997). Many properties of the neuronal nAChRs, such as their ion selectivity and gating properties, are similar to their counterparts in skeletal muscle and Torpedo tissues.

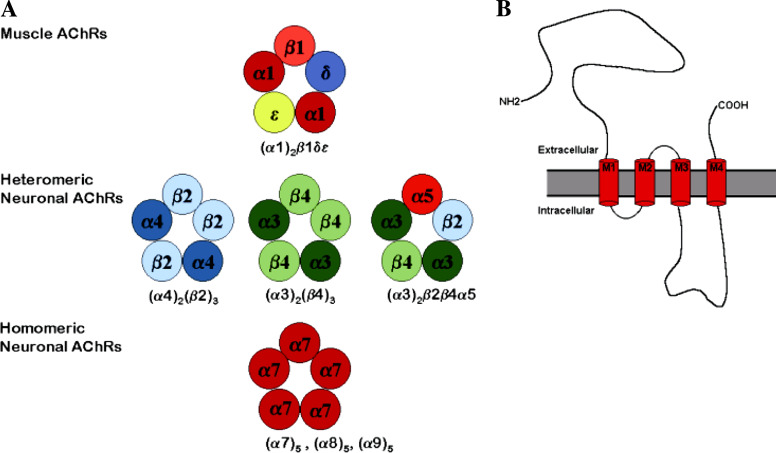

Although these receptors are distinguished by their great diversity (Role 1992; Sargent 1993), neuronal nAChR subunits share many of the structural hallmarks of their muscle relatives, including the prominent N-terminus, four transmembrane domains, a large cytoplasmic loop between M3 and M4 regions, and the short extracellular C-terminal domain (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Putative subunit arrangements of some nAChR subtypes. The nAChRs have a pentameric structure consisting of five membrane-spanning subunits around a central ion channel. (B) Topology of nAChR subunit. All nAChR subunits share a similar hydrophobicity profile: a large hydrophilic N-terminal domain that faces the extracellular environment, four transmembrane segments (M1, M2, M3, and M4), a variable cytoplasmic domain between M3 and M4, and a short extracellular carboxylic domain

Overview of Neuronal Nicotinic Receptor Structure

Like nAChR from the neuromuscular endplate, neuronal nAChRs have a pentameric structure with five rod-like membrane spanning regions around a central ionic channel, but do not contain γ, δ, or ε subunits. Instead, most neuronal nAChRs are formed only by α and β subunits. Their functional properties result from the assembly of the α and β subunits within the receptor complex (Buisson and Bertrand 2001).

The α subunits are characterized by the presence of a cysteine pair homologous to position 192 and 193 of muscle α subunit, whereas β subunits lack this cysteine pair. Presently, nine subtypes of α subunitS (α2-α10) and three subtypes of β subunits (β2-β4) have been identified and cloned in vertebrate systems (Fig. 1A). The overall amino acid homology between the genes coding for the neuronal and muscle subunits genes from the same species is about 40–55% (Sargent 1993). Homology is higher (∼100%) in the membrane-spanning regions M1–M3 and in certain regions of the N-terminal domain (Fig. 1B), albeit the amino acid sequence of the cytoplasmic domain between M3 and M4 transmembrane segments is divergent (Sargent 1993).

Neuronal nAChRs also differ from their skeletal muscle counterparts in their biophysical properties. Two characteristics that distinguished neuronal nAChRs are: inward rectification and large calcium permeability (Bertrand et al. 1990; Vernino et al. 1992, 1994 Seguela et al. 1993). This inward rectification occurs independently of the current polarity and depends primarily upon the membrane potential and internal Mg2+ (Mathie et al. 1990; Neuhaus and Cachelin 1990; Sands and Barish 1992) reviewed by Sargent (1993). Different neuronal nAChRs have different permeabilities to Ca2+, but overall they are more permeable to this cation than muscle nAChRs. The pCa2+/pNa+ for neuronal nAChRs ranges from 15 to 0.5, whereas the muscle nAChR displays a pCa2+/pNa+ of ∼0.2 (Decker and Dani 1990; Sands and Barish 1991; Adams and Nutter 1992; Vernino et al. 1992; Changeux et al. 1998).

The passage of Ca2+ through nAChR channels could activate intracellular cascades or other ion channels and potentially induce changes in the phosphorylation states of specific nAChR subunits (Vijayaraghavan et al. 1990; Mulle et al. 1992; Vernino et al. 1992; Nakayama et al. 1993).

The neuronal nAChRs can be divided into two main groups: the heteromeric and the homomeric receptors (Fig. 1A). The heteromeric receptors are composed of α and β subunits in different stoichiometries. The homomeric receptors consist of one type of subunit only. When α2, α3, or α4 subunits are expressed in pair wise combinations with β2 or β4 subunits, functional receptors with different electrophysiological and pharmacological properties can be assembled (i.e., α2β2, α2β4, α3β2, α3β4, α4β2, α4β4) (Sargent 1993; McGehee and Role 1995; Gotti et al. 2006). Although α subunits contain the ACh binding sites, several studies have revealed that β subunits have a strong influence on the dissociation rate of agonists and antagonists from the receptor, as well as on the opening rate of an agonist-bound receptor (Papke and Heinemann 1991; Papke et al. 1993; Paterson and Nordberg 2000).

The assembly of three or more neuronal subunit types could also form functional heteromeric nAChRs (Role and Berg 1996; Wang et al. 1996). For example, although the α5 subunit cannot form functional receptors in combination with β2 or β4, when expressed with α3 and β2 or α3 and β4, it gives rise to functional nAChRs (Ramirez-Latorre et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996). In this respect, a neuronal nAChR can be detected in ciliary ganglion neurons with a α3β2β4α5 subunit composition (Vernallis et al. 1993). Similarly, the β3 subunit, forms functional nicotinic receptors only when co-expressed with at least two other subunit types (Groot-Kormelink et al. 1998).

Neuronal nAChR Cellular Localization and Function

In contrast with muscle nAChRs that have a predominant postsynaptic localization, most neuronal nAChRs are located presynaptically at cholinergic and at noncholinergic terminals (i.e., they are heteroreceptors). At these locations, they regulate cholinergic, glutamatergic, dopaminergic, serotoninergic, adrenergic, and endogenous opiate neurotransmission (McGehee et al. 1995; McGehee and Role 1995; Wonnacott 1997).

Nicotine regulates ACh release from areas involved in cognition that are putatively defective in schizophrenia: cholinergic terminals from rat cortex and striatum (Rowell and Winkler 1984) (Rowell and Wonnacott 1990), (O’Shea and Ochoa 1993; Ochoa and O’Shea 1994) and from rat hippocampus (Wonnacott and Thorne 1990; Tandon and Ochoa 1992).

These sites are identified as functional presynaptic α3β2 and α4β2-nAChRs and modulate dopamine release from rat cortex and nigrostriatal terminals (Soliakov and Wonnacott 1996; Luo et al. 1998; Wonnacott et al. 2000; Hogg et al. 2003) (Sharples et al. 2000). There is also evidence to support the presynaptic locus of α7-nAChRs in the hippocampus, where they regulate glutamate release (Gray et al. 1996).

Presynaptic facilitation of neurotransmitter release by nAChRs implies their agonist-induced activation, which in turn induces depolarization of presynaptic membranes and Ca2+ entry into the presynaptic terminal (McGehee et al. 1995) through voltage activated Ca2+ channels (Hogg et al. 2003). Desensitization of these receptors may mediate inhibition of neurotransmitter release, providing a modulatory mechanism for this function.

Postsynaptic α9 nAChRs have been described in rat cochlear hair cells (Elgoyhen et al. 1994), where they mediate a long-lasting inhibitory response through Ca2+-activated potassium channels (Fuchs 1996). In the autonomic nervous system, α3 containing nAChRs also act primarily as postsynaptic receptors (Sargent 1993; Vernallis et al. 1993; Role and Berg 1996; Lindstrom 1997).

In addition to postsynaptic and presynaptic sites, nAChRs have been found at perisynaptic, extrasynaptic, and somatodendritic locations. Perisynaptic α7 nAChRs with trophic and neurotransmission functions have been detected in ciliary ganglia (Horch and Sargent 1995; Zhang et al. 1996; Ullian et al. 1997) and in hippocampal interneurons (Hurst et al. 2005). nAChRs located in the somatodendritic area are involved in catecholamine release (Rahman et al. 2003), whereas extrasynaptic nAChR localizations may provide for a novel mechanism of communication within the brain (Coggan et al. 2005).

Relevance of Presynaptic nAChRs in Schizophrenia

The most abundant nAChRs in the central nervous system are the α4β2-nAChRs, accounting for >90% of the high-affinity nicotine binding sites in the brain (Whiting and Lindstrom 1988; Flores et al. 1992; Brody et al. 2006).

This receptor subtype is the one preferentially activated, desensitized and up-regulated by nicotine (Flores et al. 1992; Ochoa 1994; Vibat et al. 1995) and it may be crucial to both the pathophysiology of nicotine dependence (Ochoa et al. 1990; Ochoa 1994) and schizophrenia (Freedman et al. 1997).

Dopaminergic neurons located at the mesencephalic ventral tegmental area (VTA) project to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (mesocortical dopaminergic pathway) and to several limbic areas of the brain such as the nucleus accumbens (mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway) (Di Chiara and Imperato 1988; Di Chiara 2000).

Nicotine stimulates dopamine release in the mesolimbic pathway (Corrigall et al. 1992) by way of nAChRs located in the VTA (Nisell et al. 1994, 1995) and the nucleus accumbens (Pontieri et al. 1996). This nicotine-induced release of dopamine has been correlated with the pleasurable effects of nicotine experienced by smokers (Benowitz 1992).

VTA neurons can be over stimulated in stressful conditions (Horger and Roth 1996) a fact particularly relevant to schizophrenia, where different types of stressors are known to precipitate a psychotic break (Lysaker et al. 2005).

Agonist-Induced Desensitization of nAChR Function

A general feature of nAChRs is that they are reversibly desensitized on chronic exposure to an agonist (Ochoa et al. 1989; Ochoa 1994; Dani and Heinemann 1996). Desensitization has been defined as a decrease or loss of the biological response after prolonged or repetitive stimulation (see review in Ochoa et al. 1989 and references therein).

The onset of desensitization depend on both time and agonist concentration (Katz and Thesleff 1957). These authors first demonstrated that prolonged exposure to sub-stimulating concentrations of nicotinic agonists reduced receptor function. They further proposed a cyclical model postulating inter-convertible high- and low-affinity agonist binding sites to explain the desensitization observed following an exposure to non-stimulating and stimulating concentration of agonists, respectively.

According to this model, the affinity of the nicotinic receptor for nicotine is higher in the desensitized state (D) than for the activable state (R) (k0 >> k1). Therefore, under prolonged nicotine exposure, receptors should stabilize in the agonist-bound desensitization state (AD).

Nicotine-Induced Up-Regulation of Neuronal nAChR

One of the most striking and puzzling effects of chronic nicotine exposure is the up-regulation of neuronal nAChRs, and in particular the α4β2 subtype in the CNS (Marks et al. 1983; Schwartz and Kellar 1985; Benwell et al. 1988a, b; Flores et al. 1992; Breese et al. 1997; Whiteaker et al. 1998). For a comprehensive review see Gentry and Lukas (2002).

Postmortem binding studies have revealed increased [3H]-nicotine and [3H]-ACh binding sites in the brains of smokers as compared to nonsmokers, with an increase in binding sites being dependent on nicotine dose (Benwell et al. 1988a, b; Breese et al. 1997). The nicotine-induced up-regulation of nAChR binding sites has been termed paradoxical (Wonnacott 1990), because chronic agonist treatment is expected to down-regulate receptor numbers.

Up-regulation of neuronal nAChR induced by chronic nicotine exposure has also been demonstrated in different in vivo systems, including rats (Schwartz and Kellar 1985; Collins 1990; Flores et al. 1992) and mice (Marks et al. 1983), and in vitro systems such as cell lines (Peng et al. 1994a, b; Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997; Whiteaker et al. 1998) and heterologous expression system (e.g., Xenopus oocytes) (Peng et al. 1994a, b; Fenster et al. 1999b; Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004).

This phenomenon reflects an apparent increase in receptor number rather than an increase in their affinity for nicotine (Marks and Collins 1985; Schwartz and Kellar 1985; Sanderson et al. 1993; Peng et al. 1994a). It is not dependent on cell type, since α4β2-nAChRs expressed in fibroblasts or in oocytes also exhibit nicotine-induced up-regulation of these receptors (Peng et al. 1994a; Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004). This notion, held for about 20 years, has been challenged recently (see below (Vallejo et al. 2005).

In humans, up-regulation is reversible (Breese et al. 1997). It is associated with tolerance to nicotine in rodents (Collins et al. 1988, 1990; Marks et al. 1993) and coincides with the time course of development of behavioral tolerance to nicotine (Marks et al. 1983; Hulihangiblin et al. 1990). Behavioral tolerance is related to desensitization of neuronal nAChR function (Marks and Collins 1993; Marks et al. 1993), but the relationship between up-regulation and dependence to nicotine is still obscure (Collins et al. 1990; McCallum et al. 1999, 2000).

Nicotine-induced up-regulation is not unique to the α4β2-nAChRs. Chronic intravenous infusion of mice with nicotine elicited an increase in brain [125I]-α-bungarotoxin ([125I]-αBgt) binding (Marks et al. 1985).

α7-nAChRs are the predominant αBgt-binding proteins in the brain. They have a higher affinity for nicotine than for ACh, but much lower affinity for nicotine than do α4β2-nAChRs (Anand et al. 1993). The extent and the duration of nicotine-induced up-regulation of [125I]-αBgt binding sites in rat brain were both less than the increase in [3H]-nicotine binding (Marks et al. 1985).

In vitro experiments showed that chronic nicotine exposure of hippocampus neurons elicits a 40% increase in the number of [125I]-αBgt binding sites (Barrantes et al. 1995). More recently, Molinari et al. reported that long-term exposure to nicotine increase the density of α7 nAChR stably expressed in HEK 293 cells (Molinari et al. 1998).

The half-maximal effective concentration to induce up-regulation of α4β2-nAChRs expressed in mouse fibroblasts (M10 cells) and Xenopus oocytes are 0.21 and 0.19 μM nicotine, respectively (Peng et al. 1994a, b). These values are very close to the typical, mean, steady state, serum concentration of nicotine in tobacco smokers (0.100-300 nM) (Benowitz 1990).

The affinity of nAChRs for nicotine and cholinergic ligands is unchanged (Marks et al. 1983; Schwartz and Kellar 1983, 1985; Collins and Marks 1987; Marks et al. 1992; Sanderson et al. 1993).

Up-regulation of α3 and α7 receptors, unlike α4β2-nAChRs, requires much higher-nicotine concentrations than those encountered in smokers. The upregulation of α3 receptors is more complex, for instance, α3β4 receptors do not upregulate well with nicotine, whereas α3β2 receptors do (Xiao and Kellar 2004). α3-containing and α7 nAChRs up-regulate at EC50 values of 100 and 65 μM nicotine, respectively, which are higher values than the nicotine concentration typical of smoker’s serum (Lindstrom 1997). Also, the extent of increase in cell surface nAChRs is less; and the mechanisms of up-regulation are different than for α4β2 nAChRs (Peng et al. 1997)

On the other hand, peripheral (i.e., skeletal muscle) nAChRs or ACh receptors of the muscarinic type are not up-regulated by nicotine (Marks et al. 1983; Collins and Marks 1987; Sanderson et al. 1993).

Up-Regulation of Neuronal nAChRs Induced by Agents other than Nicotine

Nicotine is not unique in eliciting up-regulation of α4β2 nAChRs following chronic treatment. Endogenous ACh can also up-regulate α4β2 receptors (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997; Whiteaker et al. 1998). Studies in vivo have shown an increase in high-affinity agonist binding following chronic intraperitoneal injection with cytisine (Schwartz and Kellar 1985), chronic subcutaneous infusion of anatoxin-α (Rowell and Wannacott 1990), and chronic intraventicular injection of methylcarbachol to rats (Yang and Buccafusco 1994).

Also, chronic infusion of anabasine produced an increase of high-affinity nicotinic sites in mice (Bhat et al. 1991). Furthermore, studies in cells and cell lines have shown that some nicotinic agonists can induce up-regulation of α4β2-nAChRs (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997; Whiteaker et al. 1998; Fenster et al. 1999b).

Repeated administration of the nicotinic agonist cytisine, also results in nicotinic receptor up-regulation (Schwartz and Kellar 1985). (+)-Anatoxin-α, a secondary amine, increased the density of nicotine binding sites in striatal synaptosomes (Rowell and Wonnacott 1990). Membrane impermeable quaternary amines, including the nicotinic agonist 1,1-dimethyl-4-phenylpiperazinium (DMPP) and carbamylcholine, also cause up-regulation of α4β2 nAChRs in vitro (Peng et al. 1994a). DMPP and carbamylcholine may be assumed to produce their effects from outside the cell on α4β2 nAChRs that are already in the surface membrane (Peng et al. 1994a).

Additionally, cholinergic ligands of human α4β2-nAChRs expressed in HEK293 cells also induce up-regulation (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997). Treatment with (−)-cytisine, DMPP, (±)-epibatidine, ABT-418, and A-85380, for 168 hours increases [3H]-cytisine binding level in a concentration-dependent manner (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997). The relative potencies were (±)-epibatidine >A-85380 > (−)-nicotine > (+)-nicotine > (−)-cytisine > ABT-418 > DMPP. The EC50 values for up-regulation correlated well with their binding affinities, indicating that receptor up-regulation may be related to the interaction of these ligands with the high-affinity desensitized state of nAChRs (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997).

Other extensive studies of agonist-induced up-regulation of α4β2 nAChRs in M10 cells have covered a wide spectrum of nicotinic agonists, including (−)-nicotine, (±)-epibatidine, methylcarbamylcholine (MCC), (±)-Anatoxin-a, (−)-cytisine, ABT-418, and tetramethylammonium (TMA) (Whiteaker et al. 1998). The maximum up-regulation elicited by each of the agonists was similar, except forfs MCC and (±)-epibatidine, which elicited only 16% and 38% respectively, of the maximum up-regulation observed for (−)-nicotine. Thus, MCC and (±)-epibatidine were less efficacious as inducers of the up-regulation phenomenon.

Chronic treatment with neuronal-nAChR antagonists could elicit nAChR up-regulation, although data are contradictory for some ligands. For example, the noncompetitive antagonist mecamylamine causes up-regulation of the α4β2 nAChRs (Peng et al. 1994a) but a chronic injection effect has not been detected with this compound (Schwartz and Kellar 1985). In addition, no up-regulation of α4β2 nAChRs expressed in M10 cells for mecamylamine (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997; Whiteaker et al. 1998).

Competitive antagonists such as d-tubocurarine, dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), and methyllycaconitine increase [3H]-cytisine binding in HEK293 cells (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997), leading to the proposal that nAChR functional stimulation is not required to induce up-regulation.

Since different expression systems and experimental conditions may be responsible for the aforementioned discrepancies, more work is needed to define the role of agonist, competitive and noncompetitive antagonists, competitive and noncompetitive blockers, allosteric activators and inhibitors in the up-regulation of nAChR number in these in vitro conditions

It has become very evident that the mechanisms involved in the up-regulation of nAChRs are diverse and structure-dependent. From a critical perspective, we suggest that nicotinic or other ligands acting at different sites (Fig. 2), and perhaps through diverse mechanisms, to regulate stabilization of nAChR in distinct conformations representing functionally active, functionally inactive, or up-regulated states.

Fig. 2.

Schematic cross section of the nAChR showing ion channel, ACh binding site and multiple type of ligands (NCA, CA, NCB, AA, AI, and CB) extracellular domains and ion-channel pathway of the receptor

In order to induce up-regulation, a given drug must induce a conformational state of the nAChR which is directly (or indirectly) linked to the trasmembrane signal that will trigger the incorporation of presynthesized receptors into the plasma membrane. This hypothesis departs from the traditional proposal that agonists lock nAChRs in a stable conformation, leading to their accumulation in the plasma membrane.

Functionality of Up-Regulated nAChRs

Chronic smokers typically have steady state plasma nicotine concentration of 10–50 ng/ml (100–300 nM nicotine; (Benowitz 1990)). However, nicotine levels in the mammalian brain are about three times higher (Ghosheh et al. 2001).

At this concentration of nicotine, the α4β2 nAChR will be activated preferentially over other subtypes. It has been suggested that in chronic smokers most α4β2-nAChRs (50%) are inactivated at average serum nicotine concentrations (Brody et al. 2006). The EC50 for this AChR subtype is 1–3 μM (Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004).

Recent evidence using PET scans of human smokers with the newly developed radioligand 2-FA (specific for α4β2-nAChRs) showed that their α4β2-nAChRs are totally saturated in a 24 h period (Brody et al. 2006). Saturation should keep these receptors in the desensitized state (alleviating withdrawal symptoms), and induce up-regulation of nAChRs, as seen in chronic smokers (Benwell et al. 1988a, b).

Continued smoking, despite saturation of receptor sites, may occur in order to avoid having unoccupied receptors (responsible for craving). Alternatively, persistent smoking may produce positive reinforcement via nicotine-induced activation of other α4β2 receptors of unknown stoichiometry (which are not labeled by the radioligand) (Brody et al. 2006). This study is particularly relevant to elucidate the basic mechanisms of nicotine dependence in schizophrenic smokers.

In contrast, α3-nAChRs (EC50 30 μM), α7-nAChRs (EC50 10 μM) and muscle type nAChRs (EC50 100 μM) are more resistant to inactivation by chronic nicotine exposure This has been explained postulating that a significant fraction of the α3-nAChRs, and the α7-nAChRs subtypes are already in the desensitized state due to their higher affinity for nicotine (10nM and 1.0 μM) (Quick and Lester 2002; Giniatullin et al. 2005).

Thus, while α4β2-nAChRs are subject to desensitization and functional inactivation by low concentrations of nicotine, α3β2-nAChRs are not permanently inactivated by chronic exposure to nicotine (Hsu et al. 1996), and α7-nAChRs are subject to a more rapid desensitization than α4β2-nAChRs (Albuquerque et al. 2000).

Although nicotine-induced up-regulation of nAChRs have been demonstrated to occur in both in vivo and in vitro experiments, it is still unclear whether this increase in receptor number is accompanied by long-lasting inactivation or functional up-regulation.

It is commonly held that functional activity of neuronal nAChRs is lost as a result of a rapid and persistent desensitization induced by chronic nicotine exposure (Sharp and Beyer 1986; Lapchak et al. 1989; Lukas 1991; Marks and Collins 1993; Olale et al. 1997; Shioda et al. 1997; Ke et al. 1998).

Chronic nicotine treatments induce up-regulation, which produces a non-functional, desensitized receptor (Lapchak et al. 1989; Hulihangiblin et al. 1990; Marks et al. 1993). This can be caused by agonists (e.g., nicotine) or by any agent that promotes a nonfunctional state of the receptor [e.g., mecamylamine (Collins et al. 1994; Peng et al. 1994a) or chlorisondamine (El-Bizri and Clarke 1994). Behavioral desensitization, however, is specific to the agonist (Yang and Buccafusco 1994). Recently, Girod and Role (2001) reported that presynaptic nAChR function could be lost for >24 h following a 24–72 h treatment with low doses of nicotine.

In contrast with these traditional notions based on a series of experimental results, other studies using cell lines suggested that nAChRs are functionally more active with chronic nicotine exposure (Gopalakrishnan et al. 1997; Buisson and Bertrand 2001; Nelson et al. 2003; Vallejo et al. 2005).

The difference in the effects of nicotine detected in these studies could be explained by different incubation requirements, such as temperature or culture medium of the different expression systems. Furthermore, mammalian cell lines and Xenopus oocytes may differ in the protein kinase modulation of channels expressed or in the posttranslational modifications made inside the host cells [reviewed by (Hogg et al. 2003)].

Proposed Mechanisms of Neuronal nAChR Up-Regulation

Nicotine-Induced Desensitization of Neuronal nAChRs

Both acute and chronic specific desensitization of nAChR (Changeux and Revah 1987; Ochoa et al. 1989, 1990; Changeux 1990; Ochoa 1994) have been invoked to explain the effects of nicotine on the smoker’s brain. Specific acute desensitization (tachyphylaxis) to nicotine is reversible, has rapid rates of onset and recovery, and does not correlate with alterations in nAChR number. It is responsible for developing daily tolerance to several acute effects of nicotine that resensitize rapidly overnight (e.g., muscular relaxation or enhanced cognition).

Specific chronic desensitization occurs after prolonged exposure to nicotine is less reversible than the acute type and has slower rates of development and recovery, and may be responsible for tolerance to both the rewarding properties of nicotine and to aversive effects such as nausea or dizziness.

Chronic nicotine use may induce tolerance via repeated cycles of activation of reversibly desensitized receptors and a progressive shift of the total population of activatable receptors to the desensitized state (Ochoa et al. 1990). Chronic agonist treatment could lead to an incomplete recovery that results from a long-lasting accumulation of receptors in one or more desensitized states or a permanent loss of functional channels (Lukas 1991) reviewed by (Quick and Lester 2002).

Desensitization of neuronal nAChRs may be the driving force for the up-regulation (Marks et al. 1983; Schwartz and Kellar 1985; Fenster et al. 1999a), but acute administration of nicotine and rapid desensitization are not sufficient to produce up-regulation. Prolonged administration and chronic desensitization appear to be important (Schwartz and Kellar 1985).

Chronic agonist exposure may thus result in an initial rapid desensitization, leading to further chronic inactivation of function and cholinergic deficit which is then counteracted by an increase in receptor number (Schwartz and Kellar 1985). This increase in nAChR number could be responsible for nicotine tolerance and dependence.

When the concentration of nicotine is low or absent in the brain of chronic smokers, the excess nAChRs recover from desensitization, causing hyperexcitability at the cholinergic synapses (Dani and De Biasi 2001). The hyperexcitability of the nicotinic cholinergic system could explain the urge to continue smoking cigarettes throughout the day and the withdrawal symptoms experienced by smokers when they stop smoking.

Individual nAChR subtypes vary in sensitivity to desensitization and inactivation following agonist exposure. We have demonstrated that both the rate of desensitization resulting from prolonged exposure to an agonist and the rate of recovery from desensitization depends on the subunit composition of the receptors (Vibat et al. 1995).

Three rat neuronal nAChR subunit combinations were expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes (α2β2, α3β2 and α4β2). In contrast with results obtained using the other two-subunit combinations, the α4β2-nAChR exhibited a depression of the maximum in the dose-response curves, a slower rate of nicotine desensitization, and a depression in the response to nicotine after repetitive application of the agonist.

Although the α4β2 subunit combination showed a slower-desensitization rate compared to its α2β2 and α3β2 counterparts, it remained longer in the desensitized state (Vibat et al. 1995). Precisely, the α4β2-nAChR is the one that is more abundant in the human brain and the one that is predominantly up-regulated after chronic nicotine exposure in the CNS (Flores et al. 1992; Whiteaker et al. 1998).

Later, Fenster et al. (1999b) presented four additional lines of evidence which suggest that nicotine-induced desensitization of neuronal nAChR initiates up-regulation: (1) the half-maximal nicotine concentration necessary to produce desensitization (9.7 nM) was the same as that needed to induced up-regulation (9.9 nM); (2) the concentration of [3H]-nicotine for half-maximal binding to surface nAChRs on intact oocytes (11 nM) was comparable with that for desensitization; (3) functional desensitization of α3β4 receptors required a 10-fold higher-nicotine concentrations that was mirrored by a 10-fold shift in concentrations necessary for up-regulation; and (4) mutant α4β2 receptors that do not recover fully from desensitization were up-regulated after acute (1 hour) application of nicotine.

Other lines of evidence support the desensitization hypothesis. For example: the concentrations of nicotine that induce half-maximal increases in nicotinic binding for α4β2, α3, and α7-containing nAChRs are qualitatively similar to the concentrations required for desensitization of rat receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Peng et al. 1994a, 1997). In this cell, α4β2 receptors are 50-fold more sensitive to nicotine-induced desensitization than α3- or α7-containing subtypes (Fenster et al. 1997).

Protein Kinase Modulation of nAChR Desensitization

Phosphorylation of nAChR subunits regulates many aspects of receptor function, including desensitization [reviewed by (Quick and Lester 2002)]. It is possible that such intracellular mechanisms could confer long-lasting changes during abnormal conditions, as those that occur during and after chronic nicotine exposure (Peng et al. 1994a; Fenster et al. 1999b).

As previously discussed before, chronic nicotine exposure (at levels related to those found on active smokers) both activates and desensitizes α4β2-nAChRs (Vibat et al. 1995; Fenster et al. 1997), a phenomenon believed to be responsible for initiating nAChR up-regulation (Marks et al. 1983; Schwartz and Kellar 1985; Fenster et al. 1999b).

It seems conceivable that factors that regulate desensitization of α4β2-nAChRs may contribute to the long-term effects of nicotine on neuronal nAChR number and on their function (Fenster et al. 1999a).

Evidence for the role of phosphorylation in the desensitization process came from muscle nAChRs. Direct phosphorylation of γ and δ subunits at serine residues by protein kinase A (PKA) increased the rate of desensitization (Huganir et al. 1986). Subsequently, studies of neuronal nicotinic receptors in chick sympathetic ganglia (containing α3, α4, α5, α7, β2, β3 and β4 subunits) have indicated that cyclic AMP-dependent PKA and protein kinase C (PKC) can phosphorylate this receptors, and that phosphorylation may regulate agonist-induced desensitization (Downing and Role 1987; Vijayaraghavan et al. 1990).

As mentioned earlier, nAChRs display high Ca2+ permeability (Mulle et al. 1992; Vernino et al. 1992). Thus, Ca2+ entry through these channels could regulate nicotinic receptor desensitization either directly or indirectly via protein kinase activation (Quick and Lester 2002).

In addition to the effect of Ca2+ ions on desensitization of skeletal nAChRs (Miledi 1980), it was demonstrated that the recovery rate from desensitization was most influenced by Ca2+ (Khiroug et al. 1997; Fenster et al. 1999a). Nevertheless, the way in which this cation affects the rate of recovery from desensitization remains elusive.

Whereas increased levels in intracellular Ca2+ following nAChR stimulation inhibit recovery from desensitization (Khiroug et al. 1997), this process is largely eliminated after replacement of external Ca2+ with Ba2+(Fenster et al. 1999a). It has been proposed that Ca2+ facilitates recovery from desensitization through the activation of PKC (Fenster et al. 1999a).

Activation of protein kinases (such as PKA and PKC) has been demonstrated to promote recovery from desensitization (Khiroug et al. 1998; Fenster et al. 1999a). Moreover, several studies suggested that desensitization is mediated by an alteration in the balance between the functions of protein kinase and protein phosphatase: inhibition of a Ca2+-dependent phosphatase speeds recovery from desensitization and a decrease in cellular phosphorylation prolongs the time the receptor remains in the inactivated state (Quick and Lester 2002).

Since the role that phosphorylation of nAChR subunits play on the desensitization process is still unknown, it is important to evaluate what nAChR subunits are subjected to additions of phosphate moieties. The majority of the consensus sequences for phosphorylation are located in the cytoplasmic domain between M3 and M4 transmembrane regions (Swope et al. 1992).

For example, the α4 subunit contains at least nine serine phosphorylation consensus sites. Several in vitro studies have demonstrated that some of these sites are directly phosphorylated by PKA or PKC (Vijayaraghavan et al. 1990; Nakayama et al. 1993; Moss et al. 1996; Wecker et al. 2001). Biochemical studies on rat α4β2- nAChR either isolated from rat brain (Nakayama et al. 1993) or immunoprecipitated from Xenopus oocytes (Hsu et al. 1997) provided evidence that the α4 subunit is a substrate for phosphorylation by PKA.

There are also phosphorylation sites for cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and protein kinase C in the amino acid sequence corresponding to the M3/M4 cytoplasmic domain of the α4 subunit expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Wecker et al. 2001; Guo and Wecker 2002; Wecker and Rogers 2003). Ser365, Ser472, and Ser491 are phosphorylated by PKA, suggesting that these positions represent posttranslational regulatory sites on the(α4β2 nAChR (Guo and Wecker 2002). S470, S493, S517, and S590 are not phosphorylated by PKC or PKA. Elimination of a PKC phosphorylation site in the α4 subunit, by the replacement of a serine at position 336 for an alanine residue, inhibited recovery from desensitization of α4β2 nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Fenster et al. 1999a).

Since phosphorylation of nAChR subunits plays a pivotal role in nAChR desensitization, the study of factors that alter the balance of protein kinase/protein phosphatase function could be critical to fully understand α4β2-nAChR up-regulation.

Reduced Receptor Turnover

Although receptor desensitization may be important in the initial stages of receptor up-regulation, it is possible that other factors also mediate increases in receptor number. For example, chronic nicotine exposure of M10 cells expressing α4β2 receptors produced a decrease in the rate of receptor turnover (Peng et al. 1994a).

The decrease in the rate of receptor turnover could explain the nicotine-induced increase in nAChR number. It was unlikely that nicotine regulated nAChR expression by changing transcriptional activities, because the levels of messenger RNA for both the α4 and β2 protein subunits were not changed after chronic nicotine exposure (Peng et al. 1994a).

Surface Versus Internal Up-Regulation

A very elegant study by Darsow et al. appears to contradict the notion that increased turnover is a satisfactory explanation of receptor up-regulation (Darsow et al. 2005). Using HEK293 cells expressing the α4β2-nAChR and brefeldin A, a fungal metabolite that disrupts transport of secreted proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi, it was found that neither acute nor chronic administration of nicotine altered endocytic trafficking of α4β2 2nAChRs. Instead, chronic nicotine exposure increased α4β2-nAChR number transiting from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the surface membrane. A similar result was obtained using the same HEK293 cells and human neuroblastoma cells transfected with the α4β2-nAChR (Sallette et al. 2005).

These results are consistent with previous studies on the muscle AChR, where the limiting step for surface expression appears to be at the ER (Ross et al. 1991; Wang et al. 2002). Based on these findings, nAChR up-regulation would occur prior to their insertion in the plasma membrane.

Influence of Receptor Subunit Composition in Up-Regulation of the α4β2-nAChR

Although the (α4)2(β2)3 was the subunit stoichiometry proposed for the α4β2- nAChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Anand et al. 1991; Cooper et al. 1991), several functional studies suggest that this is not the only stoichiometry present in cells that express this nAChR subtype.

Patch clamp recordings from oocytes expressing the α4β2 nAChR have demonstrated that single-channel conductance depends on the α:β ratio of the mRNA injected into the oocyte (Papke et al. 1989). When three different ratios of α4 and β2 were injected into the nucleus of Xenopus oocytes, different sensitivities to ACh and d-tubocurarine were obtained using voltage clamp recording (Zwart and Vijverberg 1998)suggesting that the subunit stoichiometry of functional heteromeric α4β2 nAChRs is not limited to (α4)2(β2)3.

Furthermore, using human embryonic kidney cells as a expression system, two functional types of α4β2 nAChRs have been reported (Nelson et al. 2003). The predominant subunit stoichiometry of α4β2 nAChRs expressed in human embryonic kidney cells was 3(α4):2(β2), but overnight nicotine exposure increased the proportion of nAChRs with a 2(α4):3(β2) stoichiometry.

The α4:β2 mRNA stoichiometry plays a critical role in nAChR up-regulation and functional loss induced by chronic nicotine exposure (Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004). Oocytes microinjected with the 2(α4):3(β2) stoichiometry displayed an increase in membrane nAChR following chronic nicotine exposure. After chronic nicotine exposure, the 2(α4):3(β2) was the only stoichiometry that clearly up-regulated. In contrast, 4(α4):1(β2) which produced the largest amount of macroscopic current, apparently, showed down-regulation and 1(α4):4(β2) did not show a significant change. Since the stoichiometry with the highest proportion of the α4 subunit, 4(α4):1(β2), resulted in receptor down-regulation and drastic loss in function, our data suggest that the α4 subunit controls the inactivation and trafficking of the nAChR heteropentamer (Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004).

The properties of agonist binding for α4β2 channel activation might also have distinct dynamics or perhaps structural requirements for ACh and nicotine.

In contrast to the nicotine-induced activation of α4β2-nAChR that appeared to be independent of the subunit ratio expressed on the oocyte surface, desensitization was remarkably affected by acute nicotine exposure. Activation and desensitization of α4β2-nAChR by nicotine could be triggered by two independent mechanisms, which in turn suggest the possibility of at least two distinct binding sites for nicotine.

Since nicotine-induced desensitization and up-regulation of α4β2 nAChR is regulated by subunit ratio (Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004) and given that this receptor subtype is wide spread in brain presynaptic terminals, control of the subunit ratios of these heteropentamer receptors could regulate neurotransmitter release in the central nervous system and nicotine sensitivity in humans.

We suggest that abnormal up-regulation of receptor subtypes such as the one observed in vitro (Lopez-Hernandez et al. 2004) should be considered from an in vivo perspective, when considering the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, where neuronal nAChRs with different subunit types and stoichiometries could be responsible for defective up-regulation of nicotinic receptors (Breese et al. 2000) (see discussion below).

An indirect support for this argument could be found in a recent study by De Luca et al. (2006) where the polymorphisms in the CHRNA4 and the CHRNB2 genes (which control the expression of the neuronal α4 and β2 subunits respectively) were explored in 117 Canadian families having at least one schizophrenic patient.

The interactions between the CHRNA4 and CHRNB2 genes produced a significant risk effect for schizophrenia, but this was not the case for each gene acting separately. The effects of the interactions between other genes for other neuronal nAChRs are still unknown.

Another Mechanism Proposed for Up-Regulation

In contrast to the aforementioned studies, chronic nicotine treatment of K-177 cells expressing the human α4β2-nAChR resulted in functional receptor up-regulation (Buisson and Bertrand 2001). Using a heterologous expression system, the same authors reported an increase in the ACh-evoked response measured by whole cell voltage clamp, contradicting the notion of that these receptors are non functional after chronic exposure to nicotine (Vallejo et al. 2005).

These investigators hypothesized that chronic nicotine treatment produced a conversion from low-affinity nAChRs into high-affinity nAChRs (the phenomenon being termed “functional up-regulation”). The two distinct affinities observed for the ACh concentration–response curves were interpreted as a result of two distinct functional states of the α4β2 receptors. Subunit phosphorylation was suggested as a possible mechanism for the interconversion from low-affinity into high-affinity α4β2-nAChRs.

The up-regulated AChR displayed a larger single-channel conductance, suggesting a remarkable functional change of state with nicotine exposure. This functional change was probably not due to a change in subunit stoichiometry, since a change in receptor subunit stoichiometry was unlikely after receptor insertion into the plasma membrane.

Thus, nicotine may slowly transform α4β2-nAChRs into an up-regulated state that displays increased response and sensitivity to agonist (Vallejo et al. 2005).

Abnormal Nicotine-Induced Regulation of Receptor Number in Schizophrenia

The human brain exhibits the phenomenon of receptor up-regulation (Benwell et al. 1988a, b). Simmilarly, autopsy material from chronic smokers showed increased number of nAChRs depending on the number of cigarettes smoked daily (Breese et al. 2000). This was evidenced by 3H-epibatidine binding to postmortem material from hippocampus, cortex, caudate, and thalamus, suggesting that the up-regulation phenomenon had poor-region specificity.

The affinity for the ligand remained unchanged and the increase in receptor number was reversible (Breese et al. 1997, 2000). The same authors showed that administration of concomitant antipsychotic medication (in this case the typical antipsychotic haloperidol) did not influence the nicotine-induced receptor up-regulation (Breese et al. 2000).

Surprisingly, the study showed that schizophrenic patients have fewer high- affinity nAChRs than either chronic smokers or than chronic smokers who are mentally ill with comparable daily use of cigarettes (Breese et al. 2000). The subunit composition and the functionality of these receptors were unknown, although it is conceivable that they were α4β2-nAChRs due to their predominance in the brain over other receptor subtypes.

Overview of Neuronal nAChR Up-Regulation: Perspectives for Future Therapeutic Strategies Aimed at Cholinergic Deficit Remediation

A reduction in the number of nAChRs is associated with diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies, and Parkinson’s disease (Nordberg 1994; Court et al. 1999; Perry et al. 2000). Furthermore, patients with schizophrenia who are chronic smokers do not up-regulate their nAChRs (Breese et al. 2000).

Since alterations in nicotine-induced nAChR number are associated to several pathologies, and due to the central role that these receptors have in cognitive operations within the brain (see below), there are several fundamental questions that deserve further experimental inquiry:

What is the functional state (active/inactive) of new neuronal nAChRs that are being exported from the EM (see Fig. 3)?

What is the mechanistic relationship (if any) between nAChR desensitization, inactivation, and up-regulation?

What is the relationship between allosteric states of the nAChR and their loss/activation of function? Does this relationship depend on the dose and on the length of nicotine exposure (see Fig. 3, R ↔ D ↔D*nic ↔ I nic)?

What is the effect of phosphorylation on nAChR function and up-regulation? What are the specific contributions of all the putative phosphorylation consensus sequences in the M3/M4 intracellular loop?

Is there any altered nAChR subunit stochiometry in a specific receptor subtype(s) in the schizophrenic brain that is responsible for a defective nicotine-induced nAChR up-regulation?

What is the potential chronic affect of medications that affect nAChRs (such as allosteric potentiators, see below) on their ability to increase the number of nAChRs. How does this affect the potential clinical benefits of these medications?

Fig. 3.

Overview of the proposed mechanisms for up-regulation of the α4β2 nAChR. A resting α4β2 nAChR is desensitized (D nic) after acute nicotine exposure. Recovery from D nic to the resting is relatively fast (5 min). After chronic exposure the D nic enters into a long-lived desensitized state from which recovery is very slow (hours) depending on the period of exposure). The long-lived desensitized state D*nic represents a different conformation than R and D nic. The majority of studies in heterologous and natural expression experimental systems have indicated that chronic nicotine induces a persistent inactivation (loss of functional responsiveness) and a numerical up-regulation of α4β2-nAChR. Mechanistically, the relation between numerical up-regulation and inactivation remains to be defined. Several posttranscriptional mechanisms have been demonstrated to contribute to the functional changes and numerical up-regulation (i.e. phosphorylation of the M3/M4 loop, increase in transport of the α4β2 nAChR from the ER to the plasma membrane and changes in α4/β2 subunit ratio). A subset of studies has suggested that chronic nicotine exposure does not produce a numerical up-regulation of the α4β2 nAChR. Rather than proposing numerical receptor up-regulation, these studies suggest that after chronic nicotine exposure the receptor increases its functional response and its sensitivity to the agonist

Understanding the basic mechanisms of nicotine-induced numerical regulation of nAChRs will facilitate the development of more effective therapeutic agents used in diseases where cognitive dysfunction is the prime target

Neuronal nAChRs are Involved in Normal Mammalian Cognitive Processess

Cholinergic receptors of both the nicotinic and the muscarinic type are involved in cognitive processes within the brain. The latter is substantiated by the acute confusional states induced in humans by antimuscarinic drugs (Tune and Egeli 1999; Tune 2001). The focus of this review, however, will remain on specific cognitive functions subserved by neuronal nAChRs.

Neuronal nAChRs participate in attentional and memory processes of humans and other animals (Levin 1992; Holscher 1999; Perry et al. 1999; Woolf 1999; Levin 2002; Levin et al. 2002, 2005). Administration of nicotine enhances cognition (Warburton 1992; Levin and Simon 1998; Grilly et al. 2000; Levin and Rezvani 2002), whereas nicotinic antagonists impair it (Levin et al. 2006).

As mentioned before, neuronal nAChRs are reduced in number in Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type and are responsible for the cognitive deficits exhibited by these patients (Coyle et al. 1983; Whitehouse and Kellar 1987; Nordberg et al. 1989; Maelicke and Albuquerque 2000; Perry et al. 2000).

Most of the information on the possible participation of specific subtypes of nAChRs in the pathophysiology of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia comes from the use of specific agonist/antagonist of receptor subtypes which are injected in key areas known to be affected in the disease (Levin et al. 2006).

The hippocampus is an important area of the brain involved in working memory. This can be demonstrated by injecting the nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine and by observing the subsequent impairment in this cognitive function (Ohno et al. 1993; Kim and Levin 1996). At least two subtypes of nAChRs are involved: α7-nAChRs and α4β2-nAChRs. Acute infusions of either MLA (an α7-nAChR antagonist) into the ventral hippocampus or of DHβE (an α4β2-nAChR antagonist) cause impairment in working memory (Levin et al. 2002). Administration of nicotine reverses only the DHβE effect, indicating that the nicotine enhancing effects on working memory fully depend on α7-nAChRs rather than on α4β2-nAChRs.

DHβE or MLA injections into the medial or the lateral-frontal cortex failed to impair working memory (Levin et al. 2004). As previously seen, these agents impair working memory when infused in the ventral hippocampus (Levin et al. 2002).

The thalamus is a site of great density of nicotinic receptors (Rubboli et al. 1994). When DHβE is infused in the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (a nucleus that has reciprocal connections with the frontal cortex), working memory improves (Levin et al. 2004). The function of nicotinic receptors in the anterior thalamic nuclei (which receive projections from the limbic system) has not been characterized. Muscarinic receptors in this area may be important, since scopolamine infusion causes memory impairment (Mitchell et al. 2002).

Another important subcortical nucleus, the amygdala, is implied in working memory. Blocking α7 and α4β2-nAChRs in the basolateral amygdala causes deficits in this cognitive function (Levin and Rezvani 2002).

More caudally in the central nervous system, midbrain dopaminergic nuclei such as the VTA and the substantia nigra are also implied in working memory regulation. Mecamylamine (but not the muscarinic agent scopolamine) is able to impair working memory when injected into these nuclei (Levin et al. 1994).

Genetically engineered mice have provided another line of evidence regarding participation of neuronal nAChRs in cognition. The α4 (Tapper et al. 2004) and the β2 subunit (Picciotto et al. 1999; Maskos et al. 2005) are linked to both the reinforcing properties and to the cognitive augmenting effects of nicotine.

Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia: The Core Feature of the Disorder

Abnormalities in brain structure have been documented in certain patients with schizophrenia (Silbersweig et al. 1995; McCarley et al. 1999). About 15 to 30% of patients with schizophrenia have an enlargement of both the lateral and the third ventricles (Johnstone et al. 1976), a finding also confirmed in first episode patients (Lieberman et al. 1992). Abnormalities in the thalamus (Andreasen et al. 1994; Jones 1997; Gilbert et al. 2001) and in the left hemisphere have also been documented (Friston et al. 1992).

The cellular basis of these abnormalities appear to be a disruption in normal synaptic organization rather than neuronal loss (Selemon and Goldman-Rakic 1999) possibly due to aberrant programed cell death (Kozlovsky et al. 2002). Taken altogether, these abnormalities appear to be a sufficient anatomical substrate to explain cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia.

Clinically, these patients present as three distinct clusters of symptoms when factor analysis techniques are used (Liddle et al. 1989): the psychotic/reality distortion cluster (delusions and hallucinations), the disorganization cluster (disorganized behavior and thinking and inappropriate affect), and the psychomotor poverty cluster (decreased spontaneous movements, plus the classical negative signs identified as: attentional deficits, alogia, affective flattening, avolition/apathy, asociality, and anhedonia).

Negative signs and the disorganization cluster (but not the psychotic cluster) can be correlated with cognitive deficits using more elaborate neuropsychological testing (Elvevag and Goldberg 2000; Kuperberg and Heckers 2000; O’Leary et al. 2000).

Schizophrenic patients score one (or more) standard deviation below the mean of healthy controls across several neuropsychological tests (Saykin et al. 1991; Hoff et al. 1992; Mohamed et al. 1999). The NIMH-established program known as MATRICS (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) (Green et al. 2004; Nuechterlein et al. 2004) has identified several key cognitive domains as impaired in schizophrenia (for a review see Green 2006).

These include deficits in speed of processing and visuomotor skills (Censits et al. 1997; Heinrichs and Zakzanis 1998) , selective attention, working memory, and executive function, and IQ values that go from normal to mental retardation values.

Verbal declarative memory and selective attention (vigilance, but not divided and sustained attention) are exquisitely impaired in schizophrenia. Language is also defective as demonstrated by simple tests that measure reasoning and verbal fluency. All these deficits are premorbid to the full blown syndrome of schizophrenia and predate antipsychotic treatment (Saykin et al. 1994; Torrey 2002).

Apart from the aforementioned negative signs, cognitive deficits manifest themselves in neurological signs: deficits in motor coordination, cerebellar signs as finger to nose or heel to shin, Romberg sign, tandem walking, and motor sequences that require an intact frontal cortex. Perceptual abnormalities are also demonstrated as poor stereognosis and graphestesia.

Negative symptoms and cognitive deficits can be confounded by depression, dyskinetic-inducing effects of antipsychotic medications, paranoia preventing social interaction, or the isolating effect of institutionalization. However, it is now recognized that cognitive impairment is a phenomenon unique and central to schizophrenia, since cognitive deficits predate the onset of psychosis (Saykin et al. 1994; Torrey 2002). Improvement in positive symptoms does not necessarily imply amelioration of cognitive impairment, and negative symptoms are stable over time once they appear (Hirsch and Weinberger 2003).

Cognitive deficits and the psychomotor poverty cluster (but not the psychotic/reality distortion cluster) are important as prognostic indicators of how well patients will be able to function more or less independently in the community (Andreasen 1982).

Due to the salient role of neuronal nAChRs in normal cognition, and given that schizophrenia is a disorder defined by specific cognitive deficits, a question that naturally follows is: what is the role of neuronal nAChRs in the pathophysiology of this brain disorder?

Nicotinic Receptors are Involved in Abnormal Human Cognitive Processess: Relevance to Schizophrenia

The α7-nAChR Subtype

When nonmentally ill subjects are exposed to paired auditory stimuli and the corresponding evoked potentials are recorded, the amplitude of the second auditory response (P50 component of the evoked response) is reduced, compared to the amplitude of the first response. The evoked potential change is cholinergically mediated (Luntz-Leybman et al. 1992) and reflects inhibitory mechanisms that reduce sensory overload in healthy subjects.

Indirect evidence from animal models suggests that activation of α7-nAChRs located in hippocampal interneurons is essential for normal attentional processes, although α4β2-nAChRs might be even more prominent in this respect as suggested by Albuquerque (Alkondon and Albuquerque 2001).

Interestingly, the impairment in sustained attention seen in schizophrenic patients can be correlated with neurophysiological deficits using the P50 auditory evoked potential (Freedman et al. 1997). These patients cannot filter, as normal controls do, the second of two paired auditory stimuli (Freedman et al. 1991; Waldo et al. 1991; Adler et al. 1992). Smoking (Adler et al. 1993) or administration of nicotine (Adler et al. 1992) reverses this P50 deficit.

This phenotypic trait in schizophrenia is transmitted as an autosomal dominant phenotype and has been linked to a dinucleotide repeat polymorphism located less than 120 kb from CHRNA7 on chromosome 15q14 (Freedman et al. 1997; Weiland et al. 2000).

Expression of the α7 subunit is decreased in postmortem hippocampus from schizophrenia patients when compared to controls (Freedman et al. 1995) and the frontal cortex of the schizophrenic brain shows decreased levels of this subunit (Guan et al. 1999). Antagonists of α7 induce sensory gating deficits analogous to those seen in schizophrenic patients (Stevens et al. 1996).

Another marked deficit exhibited by schizophrenic patients is reflected in smooth pursuit eye movement (Radant and Hommer 1992) a sensory defect also normalized by nicotine (Olincy et al. 1998).

The aforementioned body of evidence led to the hypothesis that defective activation of α7-nAChRs is implied in attentional deficits in schizophrenia and prompted the development of partial agonists of α7-nAChRs in a recent proof-of-concept trial of 12 patients with schizophrenia (Olincy et al. 2006).

Schizophrenic patients self-administer more nicotine than nonschizophrenics, because their smoking pattern is characterized by deep inhalation patterns, shown by elevated blood levels of cotinine when compared with nonmentally ill chronic smokers (Olincy et al. 1997). This behavior delivers more nicotine per puff and conceivably increases nicotine concentration in the vicinity of neurons (Olincy et al. 1997). It is not known whether such high concentrations of nicotine are capable of desensitizing and up-regulating α7 receptors.

Desensitization of α7-nAChRs has been invoked as the basis of sensory gating defects in schizophrenia (Griffith et al. 1998). At the concentrations seen in the plasma of smokers, nicotine activates nAChRs (Gray et al. 1996) and desensitizes nAChRs (Fenster et al. 1997), but it is unable to up-regulate α7-nAChRs (Marks et al. 1985; Collins et al. 1994). Only high concentrations of nicotine up-regulate α7-nAChRs (Marks et al. 1983).

Although the evidence on the α7-nAChR participation in schizophrenia is compelling, this nicotinic receptor subtype is only involved in selective attentional deficits (Olincy et al. 2006) leaving unanswered the question of what other nAChR sybtypes are involved in other deficits.

Given the diversity of nAChRs in the brain (see pertinent section of this review), it seems logical to conclude that nAChR subtypes other than the α7-nAChR might be involved in the pathophysiology of cognitive deficits seen in patients with schizophrenia.

Cigarette Smoking as a Possible Alleviation of Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia

Smoking is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in the general population (Piasecki and Newhouse 2000). The high prevalence of smoking in schizophrenia (O’Farrell et al. 1983; Masterson and O’Shea 1984; Hughes et al. 1986; Ziedonis et al. 1994; de Leon et al. 1995) may provide a clue for understanding the cognitive deficits that predate this neuropsychiatric disorder. Patients with schizophrenia smoke more than smokers who do not carry this psychiatric diagnosis (de Leon et al. 1995) or more than patients with other psychiatric disorders (Hughes et al. 1986; de Leon et al. 1995; Diwan et al. 1998).

The relationship between smoking and schizophrenia can be explained by two, not necessarily mutually exclusive, hypotheses (Dalack et al. 1998):

schizophrenic patients smoke to alleviate mood and cognitive symptoms induced by antipsychotic agents

schizophrenic patients smoke to alleviate mood and cognitive symptoms that predate the onset of the illness (Dalack and Meador-Woodruff 1996)

With regard to the first hypothesis, it has been shown that nicotine relieves the undesired side effects of the typical antipsychotic medications (Goff et al. 1992). Five milligrams of haloperidol given to either a non-schizophrenic smoker or to a schizophrenic patient who smokes, increases their consumption of cigarettes (Dawe et al. 1995; McEvoy et al. 1995a). It can be postulated that blockade of D2 receptors, concentrated in the so called “pleasure giving” dopaminergic pathways, reduces subjective levels of reward that can be compensated by nicotine.

Interestingly, clozapine decreases smoking in schizophrenic patients (McEvoy et al. 1995b, 1999), normalizes P50 gating at 500 msecs (Nagamoto et al. 1996), and induces c-fos expression in the prefrontal cortex (Deutch and Duman 1996) and the thalamic paraventricular nucleus (Deutch et al. 1995) by a yet to be identified mechanism. The effects of clozapine on nAChR function are still unknown.

There is a good evidence that cigarette smoking affects the blood concentration of antipsychotic medications or their metabolites. A significant reduction (20–40% lower) in plasma levels is documented for clozapine (Seppala et al. 1999), haloperidol (Shimoda et al. 1999) and olanzapine (Zyprexa, package insert).

With regard to the second hypothesis (smoking alleviates naturally occurring cognitive deficits), it has been proposed that the heavy smoking of schizophrenic patients may be an attempt to help them focus in a heavy-loaded sensory environment (Adler et al. 1992). In this regard, the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia can be partially ascribed to a defective prefrontal dopamine transmission in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Laruelle 2003).

Amelioration of Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia: Focus on Neuronal nAChRs

Non-Pharmacological Strategies

Therapeutic approaches designed to reduce cognitive impairment in schizophrenia can be divided into non-pharmacological and pharmacological. Among the former, modalities such as Modularized Social Skills Training (Liberman 1998), Family Psychoeducation (Pitschel-Walz et al. 2006; Pollio et al. 2006), and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Chadwick and Lowe 1990, 1994) are all validated therapies.

Pharmacological Strategies

A variety of pharmacological treatments have been proposed, which include the cognitive enhancing effects of second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (Purdon et al. 2000; Keefe et al. 2006) manipulations of the cholinergic nicotinic and muscarinic systems (Friedman 2004) or anabaseine derivatives (Olincy et al. 2006). Nicotine, of itself, improves attention but not other cognitive functions. Desensitization of nAChRs is the most probable explanation for this modest effect of nicotine on cognition (Harris et al. 2004).

Second-Generation Antipsychotics (SGA)

These agents have improved the natural course of schizophrenia but negative symptoms have proven to be somewhat refractory to pharmacotherapy (O’Leary et al. 2000). The cognitive enhancing properties of the so-called atypical antipsychotic drugs have been demonstrated at least for olanzapine and risperidone (Purdon et al. 2000; Keefe et al. 2006) although there is no evidence that they have direct effects on nAChRs. Interestingly, atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine or risperidone reversibly and dose-dependently reduce the frequency of miniature endplate potentials for vertebrate muscle nAChRs (Nguyen et al. 2002). Although muscle nAChRs are structurally related to their brain counterparts, there is no conclusive evidence to date that interactions between atypical antipsychotics and neuronal nAChRs can be ascribed to clinically relevant antipsychotic or to cognitive-enhancing effects.

Galantamine

This drug is used clinically to enhance cholinergic transmission and has been approved by the FDA to treat the cognitive deficits associated with Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (Tariot et al. 2000; Wilcock et al. 2000). Galantamine allosterically potentiates neuronal nAChRs (Albuquerque et al. 1997; Maelicke and Albuquerque 2000) and is also a cholinesterase inhibitor. The activity of cholinergic receptors of the muscarinic type is not affected by galantamine, indicating that its sensitizing effects on nAChRs is via true allosteric potentiation rather than by an enhancement in cholinergic transmission due to acetylcholinesterase inhibition (Samochocki et al. 2003).

Using mouse brain slices (Zhang et al. 2004) and in vivo microdyalisis experiments in rats (Schilstrom et al. 2006), it has been shown that galantamine increases dopamine release (Zhang et al. 2004) and the firing activity of dopaminergic cells in the ventral tegmental area via allosteric potentiation of presynaptic nAChRs (Schilstrom et al. 2006). The same mechanism was invoked to explain an increased release of dopamine in the medial prefrontal cortex (Schilstrom et al. 2006).

Preliminary evidence suggests that galantamine can improve negative symptoms in schizophrenia (Vovin et al. 1991, 1992; Rosse and Deutsch 2002; Arnold et al. 2004). It is thus reasonable to assume that enhancement of nAChRs function may improve cognitive deficits related to negative symptoms as well.

Galantamine differs from the pure AChE inhibitor donepezil which does not have effects on either positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Buchanan et al. 2003), see also references in (Vovin et al. 1992). A randomized controlled trial using another cholinesterase inhibitor, rivastagmine, failed to demonstrate any beneficial effects on cognition in 40 patients with schizophrenia (Sharma et al. 2006).

The earliest report in the literature of cognitive benefits of galantamine was performed in Russia (Vovin et al. 1991, 1992) showing that 18 out of 30 patients clinically improved their attention in 3–4 weeks when galantamine (10–20 mg/d) was combined with the antipsychotic pimozide (unknown dose, unknown if patients were stable on the neuroleptic) and benactyzine, a muscarinic blocking agent (1–2 mg/d). The scales used were the BPRS (Rhoades and Overall 1988) and a scale used to assess negative deficits developed by the authors (Vovin et al. 1992). The smoking status of these patients was unknown.

In 2002, the case of two treatment-resistant patients with schizophrenia (smoking status unknown) was reported by Allen and McEvoy (2002). Risperidone (at unknown dose, unknown smoking status of patients) was combined with galantamine (8 mg/d). In both patients both positive and negative symptoms were assessed merely clinically. In one of the two patients, disorganized thinking cleared dramatically when the galantamine dose was escalated to 12 mg twice a day. The follow-up in this study was up to 2 months for one patient.

The case of a 42-year-old man with a 20-year history of schizophrenia who needed a complicated medication regimen (four neuroleptics) to maintain clinical stability (plus the use of nicotine gum) was reported by Rosse and Deutsch (2002). The patient was cotreated with galantamine (8 mg/d), which was increased to 24 mg/d for 2 months. There was an improvement in negative (but not positive) symptoms as measured with the total scores of the Scale for the assessment of Negative Symptoms (Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, SANS (Andreasen 1982)). This easily administered scale, is a reliable indicator of cognitive impairment (Andreasen 1982; O’Leary et al. 2000).

At day 55 of drug administration, galantamine was discontinued and the SANS scores dramatically increased (Rosse and Deutsch 2002). The same group also reported an adjuvant therapeutic effect of galantamine (8–24 mg/d) on apathy (using the Apathy Evaluation Scale; AES) in one smoking-free patient with schizophrenia treated stable on both (unknown doses) risperidone and olanzapine (Arnold et al. 2004).

All these reports support the notion of a galantamine-induced cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia, but do not indicate which cognitive domains are affected. We first reported cognitive changes using a psychometric measure of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia (Purdon 2005, Personal Communication) termed Scale for the Assessment of Cognitive Impairment in Psychosis (SCIP) and the SANS (Ochoa and Clark 2004). This was a rapid (15–20 days) improvement in negative symptoms of schizophrenia in thirteen in-patients who were smoke-free and treated with neuroleptics (mainly olanzapine, initiated at the time of admission) and adjuvant galantamine (8–12 mg/d). Clinical ratings of alogia and attention were specifically improved in most cases in 20–30 days (SANS scores). One patient also showed a marked improvement in both working memory and delayed recall with the SCIP (Ochoa and Clark 2006).

Furthermore, five patients (four were nonsmokers) with schizophrenia treated with 250–450 mg/d of clozapine (a drug that has potent anticholinergic effects) plus 16 mg/d galantamine after 8 weeks also showed improved sustained attention using a neurocognitive battery (Bora et al. 2005). The PANNS (Kay et al. 1987) scores of these patients were unchanged suggesting that cognitive amelioration was independent of clinical presentation.

The most reliable studies to date are two randomized controlled trials recently published. In the first study, 16 patients (all but one smokers) already stabilized on 4–6 mg/d risperidone were given supplemental galantamine (8–24 mg/d) (Schubert et al. 2006). Using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (R-BANS; (Randolph et al. 1998) these authors demonstrated improvements in total scores, and in the attention and delayed memory subscales. The improvement observed in these two subscales of the R-BANS coincided with the preliminary report using the SCIP, which suggested improvements in both delayed recall and attention (Ochoa and Clark 2006).

The second-randomized controlled trial is a 12-week study of 24 patients already stable on a typical or first generation antipsychotic (chlorpromazine dose equivalent to 1390 mg/d) that were randomized to either placebo or galantamine (8 mg/d). The dose of galantamine was increased to 12 mg/d after six weeks (Lee et al. 2007). The authors found no substantial differences between both groups except for the increased recognition in the recognition portion of the Rey Complex Figure Test (Loring et al. 1990).

Based on their findings the authors concluded that galantamine provided little if any cognitive improvement when added to first generation antipsychotics. Notwithstanding, two possible confounding factors in this trial are (1) patients had free access to nicotine during the trial, and (2) they were on first generation antipsychotics, medications that may have potential deleterious effects on cognition (Borison 1996; Gallhofer et al. 1996).

Overall, the evidence accumulated so far indicates that galantamine provides modest cognitive remediation in schizophrenia.

Interestingly, a recent in vitro study using rat brain, showed that galantamine up-regulates nAChRs on its own (Kume et al. 2005). This finding raises the following question: what is the in vivo relationship between neuronal nAChR up-regulation and the potential therapeutic benefits of this drug?

Anabaseine Derivatives

Benzylidene derivatives of a marine worm toxin, anabaseine, have high selectivity for the α7 receptor subtype. Substituting at the 2 and 4 positions of the benzylidene ring of anabaseine renders 3-anabaseine dihydrochloride (GTS-21 or DMXB-A) and 4OH-GTS-21. In particular, GTS-21 is a partial agonist at α7-nAChRs and an antagonist at α4β2-nAChRs (Briggs et al. 1997; Kem 2000).

Due to their α7 selectivity these two compounds may have potential for treating cognitive deficits of schizophrenia (Olincy et al. 2006). The following animal and human experiments support this contention.

Aged rats improve learning and memory with chronic administration of GTS-21 (Arendash et al. 1995). Also, GTS-21 improved passive avoidance behavior and spatial memory-related behaviors in rats with bilateral lesions of the nucleus basalis in a mecamylamine-sensitive manner. Xenopus oocyte-expressed α7-nAChRs were also activated by GTS-21 (Meyer et al. 1997).

GTS-21 ameliorates cognitive deficits (radial maze learning performance) caused by permanent occlusion of bilateral common carotid arteries in rats (Nanri et al. 1998) It also improves the auditory gating deficit seen in isolation-reared rats (O’Neill et al. 2003).

Certain inbred mouse strains (such as DBA mice) exhibit sensory deficits analogous to those in patients with schizophrenia. (diminished response of the hippocampal evoked potential to the second of closely paired auditory stimuli). The severity of the deficits has been correlated with reduced α7-nAChRs in the hippocampus. GTS-21 normalized inhibition of auditory. response in DBA mice (Stevens et al. 1998). Normalization of these deficits by GTS-21 is blocked by α-bungarotoxin but not mecamylamine, indicating that the response is mediated via α7-nAChRs (Simosky et al. 2001).