Abstract

Many consensus guidelines encourage parents and teachers to openly communicate about their concerns regarding their children. These guidelines attest to the importance of achieving consensus about what issues are most critical and how to address them. The purpose of this study was to examine whether parents and teachers (1) agree about their concerns for their children with autism and (2) when given the opportunity, whether they discussed these concerns. Participants were 39 parent–teacher dyads of children with autism in kindergarten-through-fifth grade autism support classrooms. Each parent and teacher was interviewed separately about their concerns and then observed together in a discussion about the child. Parents and teachers generally agreed about their primary and secondary concerns. When given an opportunity to communicate their concerns, 49% of the parent–teacher dyads discussed problems that neither reported as their primary concern, and 31% discussed problems that neither reported as their primary or secondary concern. These findings suggest that interventions should target parent–teacher communication, rather than agreement, to facilitate home–school collaboration.

Keywords: autism, autism spectrum disorders, family–school partnerships, parent–teacher communication

Families are essential partners in the education of children with autism. Laws such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (US Department of Education, 2004) and No Child Left Behind Act (US Department of Education, 2001) and professional educational organizations such as the Council for Exceptional Children and the Autism Society of America support the importance of family–school partnerships (Murray et al., 2011). Numerous conceptual articles encourage parents and teachers to openly communicate about their concerns regarding their children. These articles attest to the importance of coming to consensus on the most critical issues and how to address them. However, there are no investigations to our knowledge that examine these processes empirically.

Given the pervasive nature of autism and its effects on individuals’ functioning at home and school (Iovannone et al., 2003), having parents participate in educational planning and service delivery is crucial (Cavkaytar and Pollard, 2009). We use the term “family–school partnerships” to encompass the variety of concepts and names that include parents in service delivery, including family–school collaboration (Blair et al., 2011), parent–professional partnerships (Bernheimer et al., 1990; Renty and Roeyers, 2006), family-centered care (Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009; McPherson, 2005), family-centeredness (Dunst, 2002), and family/parent involvement (Epstein, 2001; McWilliam et al., 1999). Family–school partnerships lead to more effective intervention implementation (Iovannone et al., 2003), improved relationships and greater satisfaction with care (Renty and Roeyers, 2006), superior outcomes for children including the acquisition, generalization, and maintenance of skills (e.g. challenging behavior; Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009; Moes and Frea, 2002; Simpson, 2005), and enhanced family functioning (e.g. more positive interactions; Benson et al., 2008; Koegel et al., 1996). It is now widely accepted that collaboration with parents constitutes a “best practice” in the education of children with autism (National Research Council, 2001).

One essential component in effective family–school partnerships is for parents and teachers to openly share their concerns and come to consensus about prioritizing and addressing them (Esquivel et al., 2008; Jivanjee et al., 2007). Parents place a high value on teachers’ willingness to listen to and take their concerns seriously (Renty and Roeyers, 2006; Whitaker, 2007). Parents also stress the importance of consistent and reliable communication with teachers (Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009), especially because their child with disabilities may not be able to talk about the school day (Renty and Roeyers, 2006). According to Spann et al. (2003), parents and teachers communicate to (1) exchange information related to the child’s needs and performance, (2) stay informed, and (3) brainstorm strategies to resolve problems that arise at home or school.

Prior research suggests the importance of establishing and maintaining a collaborative partnership between families of children with autism and schools on theoretical grounds, but this process is rarely operationalized or studied (Blair et al., 2011; National Research Council, 2001). The literature in this area suggests that teachers and parents of children with autism may not collaborate to the extent warranted (Blair et al., 2011). Parents of children with autism often are dissatisfied with their communication with teachers (Zablotsky et al., 2012) and communication worsens as children age (Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009; McWilliam et al., 1999). Parental and professional views do not always concur (Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009; Nissenbaum et al., 2002). For example, in one study, parents of preschoolers with autism were more concerned about their children’s friendships, whereas clinicians were more concerned about communication (Rapin et al., 1999). A more recent study by Dillenburger et al. (2010) found that professionals were concerned about externalizing behaviors, while parents were more worried about behaviors commonly associated with autism such as deficits in social skills. Some studies suggest that teachers report fewer and less significant concerns than parents do (Barnhill et al., 2000).

It is unclear whether the breakdown in partnerships occurs because of a lack of agreement about children’s concerns, an inability to communicate about these concerns, or both. As a first step toward better understanding the specifics of family–school partnerships for children with autism, we examined (1) whether, when queried separately, parents and teachers agree about their concerns for elementary children with autism, and (2) whose concerns are discussed when these parents and teachers engage in a conversation about the child.

Method

Participants

Participants were 39 parent–teacher dyads of children with autism in kindergarten-through-fifth grade autism support classrooms in an urban public school district. Recruitment of teachers took place with an email sent to all teachers who had participated in a larger randomized-controlled trial. The goal of the larger randomized trial was to test the effectiveness of a classroom-based autism intervention (Mandell et al., 2013). In total, 33 emails to 22 schools were sent describing the project. In all, 27 teachers from 18 schools expressed interest and subsequently consented to participate. Packets of information describing the study were sent home with the students of the consented teachers. Parents whose primary language was not English were excluded from the study. A total of 46 parents from 18 classrooms in 13 schools consented to participate. Each classroom contained between 1 and 6 parent participants. Six parents were dropped from the study because they did not keep their initial phone interview. One parent was dropped from the study because she did not participate in the dyad observation. Final recruitment numbers were 18 teachers and 39 parents from 13 schools.

As shown in Table 1, a majority of the teachers were female (89%) with an average age of 36 years (standard deviation (SD) = 11.3 years). We assessed ethnicity and race separately. With regard to ethnicity, no teachers identified as Hispanic or Latino. With regard to race, approximately 83.3% identified as White, 11.1% as African American/Black, and 5.6% as American Indian/Alaska Native. All teachers taught in autism support classrooms; a third taught in kindergarten-through-second grade classrooms. On average, teachers reported teaching special education for 10.3 years (SD = 11.4 years) and teaching children with autism for 6 years (SD = 3.4 years).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Variable | Mean (SD) or percentage |

|---|---|

| Teacher characteristics | |

| Male | 11.1 |

| Female | 88.9 |

| Age (in years) | 36.0 (11.3) |

| Caucasian/white | 83.3 |

| African American/black | 11.1 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5.6 |

| Kindergarten–first grade | 5.6 |

| Kindergarten–second grade | 33.3 |

| Kindergarten–third grade | 16.7 |

| First grade–third grade | 5.6 |

| Second grade–third grade | 5.6 |

| Second grade–fourth grade | 11.1 |

| Third grade–fifth grade | 22.2 |

| Years teaching in special education | 10.3 (11.4) |

| Years teaching children with autism | 6.0 (3.4) |

| Parent characteristics | |

| Fathers | 2.6 |

| Mothers | 94.9 |

| Other | 2.6 |

| Age (in years) | 34.9 (6.2) |

| Caucasian/White | 35.9 |

| African American/Black | 56.4 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2.6 |

| Other | 5.1 |

| Less than college | 30.8 |

| At least some college or more | 69.2 |

| Annual income of US$45,000 or less | 77.0 |

| Annual income of more than US$45,000 | 23.0 |

SD: standard deviation.

Parents were primarily mothers (95%) who averaged 34.9 years of age (SD = 6.2 years). With regard to ethnicity, a small percentage (13%) of parents identified as being Hispanic or Latino, particularly of Mexican (5%) or Puerto Rican (8%) descent. With regard to race, approximately 35.9% identified as White, 56.4% as African American/Black, 2.6% as American Indian/Alaska Native, and 5.1% as other. Most (69%) parents reported at least some college education, 49% were employed, 77% of parents reported an annual income of US$45,000 or less, and 36% were married. With regard to ethnic and racial match, in 87.2% of the dyads neither parent nor teacher reported being Hispanic/Latino; 35.9% of the dyads reported the same race.

Children were on average 7.4 years old (SD = 1.6 years); 70% were males. Most children lived with their biological parents (95%), 64% were in kindergarten-through-second grades, and 74% enrolled in free and reduced lunch programs. A majority of children were receiving speech therapy (95%) or occupational therapy (77%).

Procedure

All research activities were approved by the university’s institutional review board and school district’s research review committee. After obtaining proper consents, the first author (G.A.) contacted parents to briefly explain the study, answer any questions, and schedule a 20-min phone interview. G.A. also contacted the consented teachers to schedule the dyad observation. At the conclusion of the parent interview, the dyad observation was scheduled based on the parent’s and teacher’s availability. G.A. interviewed all parents and teachers individually, and teacher interviews were conducted after the parent interviews. Demographic information (e.g. race and ethnicity) was obtained using multiple choice questions during the interviews. A follow-up email was sent to the teacher to confirm the day/time of the dyad observation. Parents and teachers received confirmation phone calls and/or emails the day before the dyad observation. Observations were completed a few weeks after the initial parent interview.

Measures

Individual interviews

Parents and teachers were interviewed individually about their current and ideal interactions with each other, as well as their three main concerns for the child with autism (i.e. “What are your top three concerns about [insert child’s name] right now?”). Interviewees were prompted to list their concerns in rank order. For the current study, we examined parents’ and teachers’ primary and secondary concerns because many participants did not report a third concern.

Dyad observations

We observed a discussion of concerns between parents and teachers of children with autism. Each dyad was given 7 min to respond to the prompt, “Discuss a problem that [insert child’s name] has at home and at school. Provide a solution that can be used in both places.” All dyad observations were conducted in the school and videotaped.

Analysis

We computed percentages to address two research questions. First, we were interested in the extent to which parents and teachers agreed about their concerns. To answer this question, two research assistants transcribed all parent and teacher interviews. G.A. coded each primary concern into one of six categories: (1) academics, (2) problem behaviors, (3) self-help, (4) social interaction, (5) communication, or (6) restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors. This process was repeated for secondary concerns. Our second question was “Whose concern is discussed when the parents and teachers engage in a conversation about the child?” To answer this question, G.A. coded each dyad observation into the following categories: (1) Both parent and teacher concerns, (2) teacher concerns only, (3) parent concerns only, or (4) neither parent nor teacher concerns.

Results

As shown in Table 2, the most common primary concern for parents was deficits in social interaction (28%), followed by problem behavior (26%), and academics (18%). The most common primary concern for teachers was problem behaviors (31%), followed by deficits in social interaction (18%) and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors (18%). The fourth and fifth most common concerns for both parents and teachers were communication (15%) and self-help (10%). Parents’ least common concern was restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors (3%) and teachers’ least common concern was academics (8%).

Table 2.

Parents’ and teachers’ concerns in order of preference.

| Parents | Percentage | Teachers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary concerns | Primary concerns | ||

| 1. Social interaction | 28 | 1. Problem behavior | 31 |

| 2. Problem behavior | 26 | 2. Social interaction | 18 |

| 3. Academics | 18 | 3. Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors | 18 |

| 4. Communication | 15 | 4. Communication | 15 |

| 5. Self-help | 10 | 5. Self-help | 10 |

| 6. Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors | 3 | 6. Academics | 8 |

| Secondary concerns | Secondary concerns | ||

| 1. Problem behavior | 36 | 1. Social interaction | 26 |

| 2. Academics | 18 | 2. Problem behavior | 26 |

| 3. Social interaction | 15 | 3. Academics | 20 |

| 4. Communication | 13 | 4. Communication | 10 |

| 5. Self-help | 10 | 5. Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors | 10 |

| 6. Did not report a concern | 5 | 6. Self-help | 8 |

| 7. Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors | 3 |

The most common secondary concern for parents was problem behavior (36%), followed by academics (18%) and social interaction (15%). The most common secondary concern for teachers was deficits in social interaction (26%) and problem behavior (26%), followed by academics (20%). Both parents (13%) and teachers (10%) listed communication as their fourth secondary concern.

Parents and teachers shared the same primary concern 28% of the time. For 74% of our sample, either the parents’ primary or secondary concern was the same as the teachers’ primary or secondary concern; 69% of parents and teachers shared the same top two concerns, even if they were not in the same order. There were two cases in which parents and teachers reported different types of problem behaviors and self-help skills for their primary concern. In the first case, the parent was concerned about the child’s whining and the teacher was concerned about how the child sucked her fingers. In the second case, the parent was concerned about the child’s personal safety (e.g. child does not understand that riding his bike down stairs is dangerous) and the teacher was concerned about potty training. In these cases, the parent and teacher were not coded as having the same category of concern. For secondary concerns, there were no cases where parents and teachers reported different issues within the same category of concern.

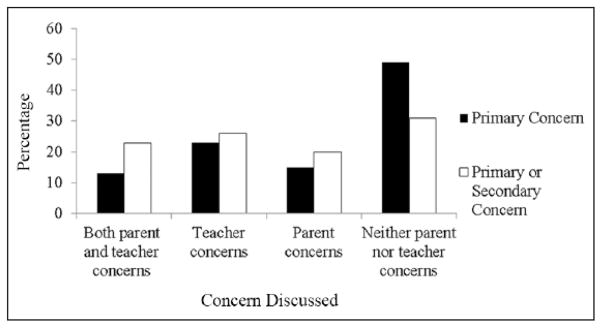

As shown in Figure 1, during the discussion about the child, 49% of the parent–teacher dyads discussed problems that neither reported as their primary concern, and 31% discussed problems that neither reported as their primary or secondary concern. Of the dyads, 23% discussed the teachers’ primary concern (and not the parents’ primary concern), 15% discussed the parents’ primary concern (and not the teachers’ primary concern), 26% discussed the teachers’ primary or secondary concern, 20% discussed the parents’ primary or secondary concern, and 13% discussed a problem that was of primary concern for both parents and teachers. For the minority of cases where parents and teachers discussed their primary concern, 40% discussed problems behaviors and 20% discussed communication, self-help, or academic concerns; no dyads discussed social interaction or restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors. Of parent–teacher dyads, 23% discussed a problem that was of primary or secondary concern for both parents and teachers.

Figure 1.

Concerns discussed by parents and teachers during dyad observations.

Discussion

Our results indicated that parents and teachers generally agreed about their top two concerns, when asked to report on multiple concerns. When they spoke with each other, however, they did not discuss either’s primary or secondary concern, instead the dyads discussed concerns that neither had reported previously.

Our first finding was that parents and teachers generally agreed about their primary and secondary concerns. Problem behavior and deficits in social interaction were the most common among parents’ and teachers’ top three primary concerns. One point of disagreement between parents and teachers was that parents rated academics as their third primary concern, whereas teachers rated this category as their last concern. In contrast, teachers rated restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors as their third primary concern, whereas parents rated this category as their last concern. It is possible that teachers were less concerned about academics than parents, because they are more familiar with the normative range of academic performance. Likewise, teachers may be more concerned with repetitive behaviors because they are disruptive in the classroom, whereas parents may have adapted to these behaviors at home.

Among concerns listed as secondary, parents and teachers reported the same three top concerns (i.e. problem behavior, social interaction, and academics), but in a slightly different order. Both parents and teachers listed communication as their fourth secondary concern. Across primary and secondary concerns, deficits in communication appeared as the fourth concern for both parents and teachers. We also found that approximately a third of parents and teachers agreed about their primary concern; however, almost three-fourths agreed when examining both primary and secondary concerns.

Our findings are inconsistent with prior investigations that have shown that parents and teachers do not share the same concerns (Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009; Nissenbaum et al., 2002). It is likely that our findings differ from previous research because we asked parents and teachers to report on multiple concerns, whereas prior studies have only focused on one main concern. If we only examined parents’ and teachers’ primary concern, our findings would be consistent with previous studies.

We also found that when parents and teachers discussed the child with each other, approximately half discussed concerns that neither reported as their primary concern and a third discussed concerns that neither reported as their primary or secondary concern. There are at least three possible reasons why parents and teachers may have discussed neither person’s concerns. First, parents and teachers may not be comfortable with each other. Prior research has established the potential adversarial relationship between parents and teachers. For example, teachers often position parents as part of the problem rather than a critical part of the solution (Wood and Olivier, 2011). Many families also report conflicts centering on a variety of issues such as differences in opinion on how to address an issue, as well as the teacher’s failure to reply to a parent’s question or request (Spann et al., 2003).

Another reason that parents and teachers of children with autism may not bring up their concern is that neither is adequately prepared to effectively communicate with the other. Teacher training programs rarely provide training on how to work with parents. Typically, teachers are trained to work with children, not adults (Ingersoll and Dvortcsak, 2006; Murray et al., 2011). Likewise, parent education programs generally do not emphasize interactions with professionals. Neither type of program addresses effective communication for successful family–school partnerships (Murray et al., 2011; Renty and Roeyers, 2006). As a result, the relationship between parents and teachers has been characterized as hierarchical, rather than as a partnership (Sperry et al., 1999). Parents and teachers may not know how to effectively negotiate with each other in choosing a topic of concern. Neither party may feel comfortable rejecting the others’ concern, even if they do not consider it a priority. It is also possible that parents and teachers do not remember their concerns when they feel pressured, as they may during their interactions, especially when being observed by a researcher.

Several study limitations should be noted. First, due to the small sample size, we did not examine other characteristics of parents, teachers, or children that may have affected their concerns or communication. For example, social support is associated with the degree to which parents are involved in the education of children with autism (Benson et al., 2008). Furthermore, several child characteristics, such as behavioral problems, verbal language, and severity of autism symptoms, have been shown to influence parents’ participation levels (Benson et al., 2008; Gabovitch and Curtin, 2009; Murray et al., 2011; Zablotsky et al., 2012). We also did not have information on how children received their autism diagnosis, which limits the external validity of our findings. However, we acknowledge this as one of the challenges in doing school-based research. Second, our observations were conducted over just 7 min and were videotaped, which may have affected parent and teacher communication. It is possible that teachers and parents may not achieve the level of comfort necessary to bring up more difficult, serious, or emotionally charged areas of concern. Third, we only investigated concerns and communication about these concerns during one point in time. Improvement in parents’ and teachers’ ability to communicate about concerns may be more apparent if examined at the beginning verses end of the school year. Fourth, we did not ask parents and teachers about the context of their concern (i.e. whether it was present at home, school, or both). It is possible that the problem the child had at both home and school (for which parents and teachers could brainstorm a solution) was not always a primary or secondary concern that parents and teachers reported individually.

Despite these limitations, the findings from this study have important implications for interventions targeting family–school partnerships for children with autism. Our results indicated that it is critical for parents and teachers to share a comprehensive list of their concerns in order to find a point of consensus. The challenge for parents and teachers appears, however, to be not so much about agreeing on a concern but rather about communicating with each other about this concern. Therefore, intervention efforts should focus on targeting parent–teacher communication, rather than agreement. For example, during conferences, one way to improve the quality of parent–teacher communication would be to ask parents and teachers to list their concerns prior to talking about them and to bring these lists to their meeting. Facilitating open discussion about a mutual problem is imperative, because effective interventions begin with an operational definition of the target behavior that is of concern to both parents and teachers. Asking parents and teachers to implement interventions consistently across home and school is an unrealistic expectation, if they cannot first communicate about a mutual concern. According to Kamimura and Ishikuma (2007), creating mutual understanding between parents and teachers requires teachers to modify their own understanding by incorporating the parents’ philosophy. In future studies, it will be important to examine whether improving parent–teacher communication has a subsequent impact on enhancing collaboration (Christenson and Sheridan, 2001).

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health National Research Service Award (F32) (grant number 1-F32-MH101994), the Autism Science Foundation Research Enhancement Mini Grant (grant number REG 14-01), the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number 1 R01 MH083717), and the Institute of Education Sciences (grant number R324A080195).

References

- Barnhill GP, Hagiwara T, Myles BS, et al. Parent, teacher, and self-report of problem and adaptive behaviors in children and adolescents with Asperger Syndrome. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2000;25(2):147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Benson P, Karlof KL, Siperstein GN. Maternal involvement in the education of young children with spectrum disorders. Autism. 2008;12(1):47–63. doi: 10.1177/1362361307085269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer L, Gallimore R, Weisner T. Ecocultural theory as a context for the individual family service plan. Journal of Early Intervention. 1990;14:219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Blair WC, Lee I, Cho S, et al. Positive behavior support through family-school collaboration for young children with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2011;31(1):22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cavkaytar A, Pollard E. Effectiveness of parent and therapist collaboration program (PTCP) for teaching self-care and domestic skills to individuals with autism. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;44(3):381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson SL, Sheridan SM. Schools and Families: Creating Essential Connections for Learning. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dillenburger K, Keenan M, Doherty A, et al. Living with children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder: parental and professional views. British Journal of Special Education. 2010;37(1):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst C. Family-centered practices: birth through high school. Journal of Special Education. 2002;36:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. School, Family, & Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel SL, Ryan CS, Bonner M. Involved parents’ perceptions of their experiences in school-based team meetings. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2008;18:234–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gabovitch EM, Curtin C. Family-centered care for children with autism spectrum disorders: a review. Marriage & Family Review. 2009;45(5):469–498. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, Dvortcsak A. Including parent training in the early childhood special education curriculum for children with autism spectrum disorder. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2006;26(3):179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Iovannone R, Dunlap G, Huber H, et al. Effective educational practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2003;18(3):150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Jivanjee P, Kruzich JM, Friesen BJ, et al. Family perceptions of participation in educational planning for children receiving mental health services. School Social Work Journal. 2007;32(1):75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura E, Ishikuma T. Teachers’ process of building rapport in parent-teacher conferences: analysis of teachers’ speech based on grounded theory approach. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;55(4):560–572. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Bimbela A, Schreiman L. Collateral effects of parent training on family interactions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1996;26:347–359. doi: 10.1007/BF02172479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M. MCHB definition of family-centered care. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Maternal and Child Health Bureau; 2005. [accessed 4 November 2014]. Available at: http://mchb.hrsa.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam R, Maxwell K, Sloper K. Beyond “involvement”: are elementary schools ready to be family-centered? School Psychology Review. 1999;28:378–394. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Stahmer A, Shin S, et al. The role of treatment fidelity on outcomes during a randomized field trial of an autism intervention. Autism. 2013;17:281–295. doi: 10.1177/1362361312473666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moes D, Frea WD. Contextualized behavioral support in early intervention for children with autism and their families. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;3:519–533. doi: 10.1023/a:1021298729297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MM, Ackerman-Spain K, Williams EU, et al. Knowledge is power: empowering the autism community through parent-professional training. The School Community Journal. 2011;21(1):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Educating Children with Autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nissenbaum MS, Tollefson N, Reese RM. The interpretative conference: sharing a diagnosis of autism with families. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2002;17(1):30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rapin I, Steinberg M, Waterhouse L. Consistency in the ratings of behaviors of communicatively impaired autistic and non-autistic preschool children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;8(3):214–224. doi: 10.1007/s007870050132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renty J, Roeyers H. Satisfaction with formal support and education for children with autism spectrum disorders: the voices of the parents. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2006;32(3):371–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson R. Evidence-based practices and students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20(3):140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Spann SJ, Kohler FW, Soenksen D. Examining parents’ involvement in and perceptions of special education services: an interview with families in a parent support group. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2003;18(4):228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Sperry L, Whaley K, Shaw E, et al. Services for young children with autism spectrum disorder: voices of parents and providers. Infants and Young Children. 1999;11:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Education. No Child Left Behind Act. 2001 Available at: http://mchb.hrsa.gov/

- US Department of Education. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. 2004 Available at: http://idea.ed.gov/

- Whitaker P. Provision for youngsters with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream schools: what parents say—and what parents want. British Journal of Special Education. 2007;34(3):170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wood L, Olivier T. Video production as a tool for raising educator awareness about collaborative teacher-parent partnerships. Educational Research. 2011;53(4):399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky B, Boswell K, Smith C. An evaluation of school involvement and satisfaction of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(4):316–330. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]