In a retrospective analysis of the EMILIA study, the rate of central nervous system (CNS) progression in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer was similar for trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and for capecitabine–lapatinib. In patients with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases at baseline, T-DM1 was associated with significantly improved overall survival versus capecitabine–lapatinib.

Keywords: ado-trastuzumab emtansine, T-DM1, metastatic breast cancer, central nervous system metastasis

Abstract

Background

We characterized the incidence of central nervous system (CNS) metastases after treatment with trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) versus capecitabine–lapatinib (XL), and treatment efficacy among patients with pre-existing CNS metastases in the phase III EMILIA study.

Patients and methods

In EMILIA, patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive advanced breast cancer previously treated with trastuzumab and a taxane were randomized to T-DM1 or XL until disease progression. Patients with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases at baseline and patients developing postbaseline CNS metastases were identified retrospectively by independent review; exploratory analyses were carried out.

Results

Among 991 randomized patients (T-DM1 = 495; XL = 496), 95 (T-DM1 = 45; XL = 50) had CNS metastases at baseline. CNS progression occurred in 9 of 450 (2.0%) and 3 of 446 (0.7%) patients without CNS metastases at baseline in the T-DM1 and XL arms, respectively, and in 10 of 45 (22.2%) and 8 of 50 (16.0%) patients with CNS metastases at baseline. Among patients with CNS metastases at baseline, a significant improvement in overall survival (OS) was observed in the T-DM1 arm compared with the XL arm [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.38; P = 0.008; median, 26.8 versus 12.9 months]. Progression-free survival by independent review was similar in the two treatment arms (HR = 1.00; P = 1.000; median, 5.9 versus 5.7 months). Multivariate analyses demonstrated similar results. Grade ≥3 adverse events were reported in 48.8% and 63.3% of patients with CNS metastases at baseline administered T-DM1 and XL, respectively; no new safety signals were observed.

Conclusion

In this retrospective, exploratory analysis, the rate of CNS progression in patients with HER2-positive advanced breast cancer was similar for T-DM1 and for XL, and higher overall in patients with CNS metastases at baseline compared with those without CNS metastases at baseline. In patients with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases at baseline, T-DM1 was associated with significantly improved OS compared with XL.

introduction

The central nervous system (CNS) is a common site of breast cancer metastasis [1, 2]. The development of CNS disease can be associated with debilitating neurological symptoms and poor survival [3, 4]. Patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are at increased risk for developing CNS metastases, with an incidence of 30%–55% [2, 5–7] compared with 5%–15% in the overall MBC population [8, 9]. Localized therapies, including surgery, whole-brain radiation, and stereotactic radiosurgery, are indicated for the treatment of CNS metastases across breast cancer subtypes, but are associated with high rates of intracranial progression [10–12].

The efficacy of systemic therapy may be limited by an inability to access the brain, drug efflux pumps that may exclude cytotoxic and HER2-directed agents, and acquired resistance to prior treatment regimens [13, 14]. Accumulating evidence, however, suggests a potential role for HER2-directed therapy in patients with CNS metastases secondary to HER2-positive MBC. In several prospective trials, lapatinib—as a single agent or combined with capecitabine (XL)—demonstrated some activity in HER2-positive CNS metastases [15–17]. It has been proposed that switching patients with treated CNS metastases to XL may prevent further CNS progression and improve patient outcomes [18]. Retrospective studies have indicated that use of trastuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting HER2, is associated with an increased time to development of brain metastases and improved survival after the development of brain metastases [4, 5, 19–21]. Although trastuzumab is generally believed to be too large to cross the blood–brain barrier, a recent positron emission tomography imaging study using 89Zr-trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive MBC has shown that trastuzumab can access brain metastases, possibly due to a compromised blood–brain barrier [22].

Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1), an antibody drug conjugate composed of the cytotoxic agent DM1 conjugated to trastuzumab via a stable linker, facilitates intracellular delivery of DM1 to HER2-overexpressing tumor cells, resulting in inhibition of microtubule function and cell death [23]. Like trastuzumab, T-DM1 inhibits HER2 signaling, prevents HER2 shedding, and induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [24]. T-DM1 is approved in several countries as a single agent for HER2-positive MBC previously treated with trastuzumab and a taxane. In the phase III EMILIA trial, T-DM1 significantly prolonged median progression-free survival [PFS; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.65; P < 0.001; 9.6 versus 6.4 months] and median overall survival (OS; HR = 0.68; P < 0.001; 30.9 versus 25.1 months), with less grade ≥3 toxicity, compared with XL in patients with previously treated HER2-positive locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) or MBC [25]. Here, we present the rates of CNS progression in the overall EMILIA population, as well as efficacy and safety results from the subgroup of EMILIA participants with pre-existing, treated/stable CNS metastases.

methods

study design and patients

EMILIA (NCT00829166) is a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial in which 991 patients with documented progression of HER2-positive, unresectable, LABC or MBC previously treated with trastuzumab and a taxane were randomized 1 : 1 to T-DM1 or XL (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Eligible patients had centrally confirmed HER2-positive tumor status, measurable and/or nonmeasurable disease, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1. Prior exposure to T-DM1, lapatinib, or capecitabine was not permitted.

Patients received T-DM1 3.6 mg/kg i.v. every 21 days or capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 orally twice-daily on days 1–14 of each 21-day cycle and lapatinib 1250 mg orally once-daily on days 1–21. Treatment continued until progressive disease (PD) or unacceptable toxicity. PFS and OS benefits in favor of T-DM1 were demonstrated in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population [25]. Patients in the XL arm were allowed to receive post-progression treatment with T-DM1 after a survival benefit in favor of T-DM1 was demonstrated in the ITT population [25].

Tumor assessments of extracranial sites were carried out by investigators and an independent review committee (IRC) at baseline and every 6 weeks thereafter, using computed tomography (CT), bone scans, X-rays, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as indicated, until investigator-assessed PD; a final assessment was required 6 weeks post-progression. Once PD was reported, patients were followed for survival every 3 months until death, loss to follow-up, withdrawal of consent, or study termination. Information on subsequent anticancer therapies after study treatment discontinuation was collected.

The primary results of EMILIA, including detailed eligibility criteria and methodology, have been published [25]. As with the primary analysis [25], a 14 January 2012 cutoff was used for PFS and time-to-symptom progression analyses. A 31 July 2012 data cutoff was used for the OS and safety analyses presented here.

The protocol was approved by the relevant institutional review boards/ethics committees. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practices, and applicable local laws. Patients provided written informed consent.

CNS metastases

All patients underwent brain MRI or CT at screening. Follow-up scans were carried out as clinically indicated, but were not mandated. Patients with CNS metastases that were untreated, were symptomatic, or required therapy to control symptoms ≤2 months before randomization were excluded, as were patients with CNS-only disease. Patients with asymptomatic CNS metastases previously treated with radiotherapy were eligible to enroll 14 days after last radiotherapy treatment.

Patients with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases at baseline or who developed CNS metastases on-study were identified retrospectively using tumor assessment data from the IRC; this analysis was exploratory and not prespecified. Kaplan−Meier methodology was used to estimate median PFS, OS, and time-to-symptom progression in the subgroup with baseline CNS metastases. These end points are defined in the supplementary Material, available at Annals of Oncology online. Stratified Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate HRs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs); P-values were calculated via a stratified log-rank test. No correction for multiple testing was carried out in these exploratory analyses. Strata were world region, prior chemotherapy regimen for LABC/MBC, and presence of visceral disease. A multivariate Cox regression model, which adjusted for potential confounding factors, was also used to estimate HRs for PFS and OS. The model included world region, prior chemotherapy regimens for LABC/MBC, presence of visceral disease, age, race, number of disease sites, prior anthracycline therapy, baseline ECOG PS, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status, baseline disease measurability, menopausal status, prior anticancer therapy, prior trastuzumab therapy, and HER2 status by fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry.

results

patients and exposure

Of the 991 patients enrolled in EMILIA, 45/495 in the T-DM1 arm and 50/496 in the XL arm had previously treated and stable CNS metastases at baseline (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Median follow-up in the ITT population was 19.1 months for T-DM1 and 18.6 months for XL. Baseline characteristics were generally similar between patients with baseline CNS metastases and the ITT population, except that patients with CNS metastases were more likely to have an ECOG PS of 1 (versus 0), ≥3 sites of disease, and visceral disease involvement (Table 1). Within the subset of patients with baseline CNS metastases, baseline characteristics were similar between treatment arms, although there was a higher proportion of Asian patients (race and region) and patients with hormone receptor-positive cancers in the T-DM1 arm and a higher proportion of patients who received whole-brain radiotherapy (versus localized radiotherapy) in the XL arm.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristics | XL |

T-DM1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with CNS metastases at baseline (N = 50) | ITT population (N = 496) | Patients with CNS metastases at baseline (N = 45) | ITT population (N = 495) | |

| Age, median (range) | 53 (34–80) | 53 (24–83) | 51 (27–71) | 53 (25–84) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 38 (76.0) | 374 (75.4) | 28 (62.2) | 358 (72.3) |

| Asian | 8 (16.0) | 86 (17.3) | 15 (33.3) | 94 (19.0) |

| Black or African American | 3 (6.0) | 21 (4.2) | 2 (4.4) | 29 (5.9) |

| Other | 1 (2.0) | 10 (2.0) | 0 | 7 (1.4) |

| Not available | 0 | 5 (1.0) | 0 | 7 (1.4) |

| World region, n (%) | ||||

| United States | 17 (34.0) | 136 (27.4) | 4 (8.9) | 134 (27.1) |

| Western Europe | 14 (28.0) | 160 (32.3) | 12 (26.7) | 157 (31.7) |

| Asia | 8 (16.0) | 76 (15.3) | 15 (33.3) | 82 (16.6) |

| Other | 11 (22.0) | 124 (25.0) | 14 (31.1) | 122 (24.6) |

| ECOG PS,a n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 24 (49.0) | 312 (63.9) | 22 (48.9) | 299 (60.6) |

| 1 | 25 (51.0) | 176 (36.1) | 23 (51.1) | 194 (39.4) |

| ER and PR status, n (%) | ||||

| ER-positive and/or PR-positive | 23 (46.0) | 264 (53.2) | 25 (55.6) | 282 (57.0) |

| ER-negative and PR-negative | 27 (54.0) | 224 (45.2) | 19 (42.2) | 202 (40.8) |

| Other | 0 | 8 (1.6) | 1 (2.2) | 11 (2.2) |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | ||||

| Premenopausal | 22 (44.0) | 229 (46.2) | 19 (42.2) | 222 (44.8) |

| Perimenopausal | 1 (2.0) | 16 (3.2) | 3 (6.7) | 22 (4.4) |

| Postmenopausal | 25 (50.0) | 204 (41.1) | 19 (42.2) | 196 (39.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (4.0) | 38 (7.7) | 3 (6.7) | 41 (8.3) |

| N/A | 0 | 9 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | 14 (2.8) |

| Baseline LVEF by local assessment,b median (range) | 60.0 (52.0–83.0) | 61.0 (50.0–88.0) | 62.0 (50.0–76.0) | 62.0 (50.0–87.0) |

| Segmental wall abnormality at baseline by local assessment,c n (%) | ||||

| No | 46 (92.0) | 471 (95.0) | 45 (100) | 477 (96.6) |

| Yes | 4 (8.0) | 25 (5.0) | 0 | 17 (3.4) |

| Number of sites of disease per IRC, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 151 (30.4) | 1 (2.2) | 143 (28.9) |

| 2 | 8 (16.0) | 156 (31.5) | 7 (15.6) | 155 (31.3) |

| ≥3 | 42 (84.0) | 175 (35.3) | 37 (82.2) | 189 (38.2) |

| Unknown | 0 | 14 (2.8) | 0 | 8 (1.6) |

| Disease involvement, n (%) | ||||

| Visceral | 38 (76.0) | 335 (67.5) | 37 (82.2) | 334 (67.5) |

| Nonvisceral | 12 (24.0) | 161 (32.5) | 8 (17.8) | 161 (32.5) |

| Measurable disease per IRC, n (%) | 43 (86.0) | 389 (78.4) | 38 (84.4) | 397 (80.2) |

| Number of prior systemic agents in any setting,d median (range) | 4 (2–13) | 5 (2–13) | 5 (2–10) | 5 (2–17) |

| Number of prior systemic agents in the metastatic setting,d,e median (range) | 3 (1–13) | 3 (1–13) | 3 (1–8) | 3 (1–9) |

| Prior radiotherapy for CNS metastases, n (%) | ||||

| Whole-brain radiation | 30 (60.0) | – | 23 (51.1) | – |

| Local treatment | 5 (10.0) | – | 8 (17.8) | – |

| None | 15 (30.0) | – | 14 (31.1) | – |

aCNS metastases: XL, n = 49; T-DM1, n = 45; ITT: XL, n = 488; T-DM1, n = 493.

bCNS metastases: XL, n = 46; T-DM1, n = 43; ITT: XL, n = 472; T-DM1, n = 489.

cCNS metastases: XL, n = 50; T-DM1, n = 45; ITT: XL, n = 496; T-DM1, n = 494.

dExcluding hormonal therapy.

eCNS metastases: XL, n = 46; T-DM1, n = 42; ITT: XL, n = 430; T-DM1, n = 429.

CNS, central nervous system; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ER, estrogen receptor; IRC, independent review committee; ITT, intent-to-treat; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; N/A, not applicable; PR, progesterone receptor; T-DM1, trastuzumab emtansine; XL, capecitabine–lapatinib.

Patients with baseline CNS metastases randomized to T-DM1 had a longer treatment duration and higher dose intensity compared with patients randomized to XL (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The percentage of patients with CNS metastases at baseline who required a dose reduction of T-DM1 versus lapatinib was similar [23.3% (10/43) versus 24.5% (12/49)]; however, 49.0% (24/49) of patients required a dose reduction of capecitabine. Of the 10 patients requiring a dose reduction of T-DM1, dose was reduced to 3.0 mg/kg in 8. A description of the anticancer therapies used in the post-progression setting is provided supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online.

efficacy

Although the absolute risk of CNS progression on study was higher in patients with baseline CNS metastases, the percentage of patients with CNS progression on study was similar for the two regimens, regardless of whether patients had pre-existing CNS metastases at baseline. Among those patients without CNS metastases at baseline, 2.0% (9/450) and 0.7% (3/446) developed CNS progression on study in the T-DM1 and XL arms, respectively. Among the 95 patients with CNS metastases at baseline, 22.2% (10/45) and 16.0% (8/50), respectively, developed CNS progression on study.

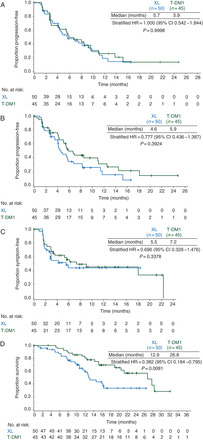

In the subgroup of patients with baseline CNS metastases, the estimated median PFS for T-DM1 (5.9 months) was similar to that for XL (5.7 months) per IRC assessment (HR = 1.00; 95% CI 0.54–1.84; P = 1.000) (Figure 1A). For comparison, median PFS among all randomized EMILIA participants was 9.6 months in the T-DM1 arm and 6.4 months in the XL arm (HR = 0.65; P < 0.001) [25]. Multivariate analysis of IRC-assessed PFS, which adjusted for baseline risk factors, was consistent with the unadjusted analysis in this subgroup (HR = 0.97; P > 0.908). Investigator-assessed median PFS also appeared similar for the T-DM1 and XL arms in patients with CNS metastases at baseline (HR = 0.78; 95% CI 0.44–1.39; P = 0.392; 5.9 versus 4.6 months) (Figure 1B). A significant difference in median time-to-symptom progression was not observed between treatment arms (HR = 0.70; 95% CI 0.33–1.48; P = 0.338; 7.2 versus 5.5 months, respectively) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Outcomes for the subgroup of patients with CNS metastases at baseline. (A) Progression-free survival according to independent review committee, (B) progression-free survival according to investigator assessment, (C) time-to-symptom progression and (D) overall survival. CI, confidence interval; CNS, central nervous system; HR, hazard ratio; T-DM1, trastuzumab emtansine; XL, capecitabine – lapatinib.

At data cutoff, there was a significant difference in OS between treatments in the subgroup of patients with baseline CNS metastases (HR = 0.38; 95% CI 0.18–0.80; P = 0.008) (Figure 1D). The estimated median OS was 26.8 months with T-DM1 versus 12.9 months with XL. This finding was consistent with the OS result among all randomized patients in EMILIA, with a median OS of 30.9 months in the T-DM1 arm and 25.1 months in the XL arm (HR = 0.68; P < 0.001) [25]. Multivariate analysis, which adjusted for baseline risk factors, showed a similar improvement in OS with T-DM1 relative to XL, as in the unadjusted analysis (HR = 0.28; P < 0.001).

safety

No new safety signals were observed in patients with baseline CNS metastases (T-DM1, n = 43; XL, n = 49), with the safety profiles of both treatments being generally similar to those reported in the overall treated population. In patients with CNS metastases at baseline, grade ≥3 adverse events (AEs; 48.8% versus 63.3%), serious AEs (18.6% versus 26.5%), AEs leading to treatment discontinuation (2.3% versus 12.2%), any-grade diarrhea (18.6% versus 79.6%), and any-grade hand-foot syndrome (2.3% versus 46.9%) occurred more frequently with XL. In contrast, a higher incidence of any-grade hepatotoxicity (25.6% versus 14.3%), any-grade thrombocytopenia (32.6% versus 4.1%), and any-grade hemorrhage (27.9% versus 12.2%) was reported with T-DM1 (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Two patients experienced cerebral hemorrhage (grade 3 subdural hemorrhage, grade 2 extradural hemorrhage); both were assigned to XL.

discussion

An important consideration when administering systemic treatment of HER2-positive MBC is the potential for CNS progression, given that the CNS may act as a sanctuary for metastatic disease in the context of a preserved blood–brain barrier [14]. This retrospective, exploratory analysis characterized the incidence of CNS progression following treatment with T-DM1 or XL in patients with HER2-positive MBC in the EMILIA study. The percentage of patients with CNS progression on-study was similar between the two treatments, irrespective of whether patients had baseline CNS metastases. These findings are consistent with the results of a prospective phase III study in patients with HER2-positive MBC without CNS metastases, which showed that the incidence of CNS metastases as the site of first relapse [odds ratio (OR) = 0.65; P = 0.360] and at any time point (OR = 1.14, P = 0.865) was similar whether a patient received trastuzumab plus capecitabine or XL [26]. In the current analysis, the low incidence of CNS progression in patients without CNS metastases at baseline may be due, in part, to continued HER2 tumor suppression, which potentially contributes to delayed development of CNS metastases by controlling extracranial disease [27–29]. Moreover, the permeability of the blood–brain barrier may be increased with the development of CNS metastases, thereby facilitating drug uptake and allowing greater local control [22, 30].

We also evaluated the efficacy and safety of T-DM1 versus XL in patients with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases at baseline. Similar to the EMILIA ITT population [25], T-DM1 was associated with significantly improved OS compared with XL in this subgroup. Although median PFS and time-to-symptom progression tended to favor T-DM1, these outcomes did not differ significantly between treatments. The reasons for the discrepancy in OS and PFS findings in patients with baseline CNS metastases are unclear. Possible explanations include the small subgroup size and asymmetry in the use and type of subsequent anticancer therapies after study treatment discontinuation. Alternatively, the effect of T-DM1 in improving OS may have stemmed from improved control of systemic extracranial disease and/or other factors. Moreover, brain metastases, which can compromise the integrity of the blood–brain barrier, could have facilitated the entry of T-DM1 into the CNS compartment [22].

The safety profiles of T-DM1 and XL in patients with baseline CNS metastases were consistent with those in the EMILIA primary analysis [25], with T-DM1 associated with a lower incidence of grade ≥3 and serious AEs. Importantly, the incidence of hemorrhage following T-DM1 was comparable between the subgroup of patients with CNS metastases at baseline and the overall safety population. No new safety signals were identified in this exploratory subgroup.

When considering the clinical implications of the current analysis, it is important to understand the benefit-to-risk ratio for distinct subpopulations of patients with HER2-positive MBC: those without detectable CNS metastases; those with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases; and those with progressive, symptomatic metastases. In this subgroup analysis, patients without detectable CNS metastases at baseline and those with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases experienced significantly longer survival with T-DM1 compared with XL, with no major differences in the rate of CNS progression between treatments. Our results, therefore, support use of T-DM1, after prior therapy with a taxane and trastuzumab, in both patient subsets.

The current analysis is limited in that the evaluation of CNS metastases was retrospective and exploratory, and the sample size was relatively small (potentially resulting in an over-adjusted multivariate model). Additionally, while brain imaging was reviewed by the IRC, there was no mandatory or prespecified imaging requirement except at screening, potentially resulting in an underestimate of the incidence of CNS progression in both treatment arms. Moreover, there may have been bias toward a lower incidence of CNS progression in the XL arm since the ITT population had shorter PFS, decreasing the possibility of detecting CNS progression that may have occurred after the first site of progression. Importantly, since patients with progressive CNS metastases were excluded, the study was not able to test whether T-DM1 can induce CNS tumor shrinkage or stabilization in the setting of untreated or active CNS disease. A recently published case report suggests that T-DM1 may be active in the brain [31].

In conclusion, our analysis suggests that T-DM1 may confer a survival advantage over XL in patients with treated, asymptomatic CNS metastases and previously treated HER2-positive MBC, without increasing the risk for CNS progression. These findings challenge the concept that patients with stable CNS disease should be switched to lapatinib-based therapy after localized treatment to prevent further CNS progression or to improve clinical outcomes. We acknowledge that these data are hypothesis-generating; however, we believe they warrant prospective study into the activity of HER2-directed therapies in patients with CNS metastases stemming from HER2-positive MBC.

funding

This work was supported by Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche Group. The protocol was designed in collaboration with the steering committee by the sponsor. The sponsor managed the data and carried out statistical analyses. The authors had access to all data and were involved in data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final manuscript approval. The sponsor also reviewed the manuscript.

disclosure

IEK has received research support from Genentech, Inc. NUL has received research funding (no direct salary support) from GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Inc., Novartis, Array Biopharma, Kadmon, and Geron. She has also served as a consultant (<$10 000) for GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. KB has served as a consultant for F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Celgene, and Novartis. Her organization has received research support from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Celgene, and Novartis. EG, ML, and MS are salaried employees of Genentech, Inc., and own stock in F. Hoffmann-La Roche. JH has served as a consultant for F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, Inc., and GlaxoSmithKline and has received grant support from GlaxoSmithKline. DM has served on advisory boards for F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, Inc. MW has served as a consultant and has received honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche. VD has served as a consultant for and has receved honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech, Inc.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript, furnished by Glen Miller, was provided by Genentech, Inc.

references

- 1.Lin NU, Bellon JR, Winer EP. CNS metastases in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3608–3617. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3271–3277. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weil RJ, Palmieri DC, Bronder JL, et al. Breast cancer metastasis to the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:913–920. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61180-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichler AF, Kuter I, Ryan P, et al. Survival in patients with brain metastases from breast cancer: the importance of HER-2 status. Cancer. 2008;112:2359–2367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brufsky AM, Mayer M, Rugo HS, et al. Central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: incidence, treatment, and survival in patients from registHER. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4834–4843. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson EM, Najita JS, Sohl J, et al. Clinical outcomes and treatment practice patterns of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in the post-trastuzumab era. Breast. 2013;22:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pestalozzi BC, Holmes E, de Azambuja E, et al. CNS relapses in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who have and have not received adjuvant trastuzumab: a retrospective substudy of the HERA trial (BIG 1-01) Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:244–248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, et al. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2865–2872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller KD, Weathers T, Haney LG, et al. Occult central nervous system involvement in patients with metastatic breast cancer: prevalence, predictive factors and impact on overall survival. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1072–1077. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2483–2491. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer MA, Kelly PJ, Chen YH, et al. Importance of extracranial disease status and tumor subtype for patients undergoing radiosurgery for breast cancer brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e479–e486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsao MN, Lloyd N, Wong RK, et al. Whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD003869. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003869.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polli JW, Humphreys JE, Harmon KA, et al. The role of efflux and uptake transporters in [N-{3-chloro-4-[(3-fluorobenzyl)oxy]phenyl}-6-[5-({[2-(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]amino}methyl)-2-furyl]-4-quinazolinamine (GW572016, lapatinib) disposition and drug interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:695–701. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steeg PS, Camphausen KA, Smith QR. Brain metastases as preventive and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:352–363. doi: 10.1038/nrc3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin NU, Diéras V, Paul D, et al. Multicenter phase II study of lapatinib in patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1452–1459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachelot T, Romieu G, Campone M, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): a single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:64–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin NU, Freedman RA, Ramakrishna N, et al. A phase I study of lapatinib with whole brain radiotherapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer brain metastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:405–414. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metro G, Foglietta J, Russillo M, et al. Clinical outcome of patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer treated with lapatinib and capecitabine. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:625–630. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirsch DG, Ledezma CJ, Mathews CS, et al. Survival after brain metastases from breast cancer in the trastuzumab era. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2114–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawood S, Broglio K, Esteva FJ, et al. Defining prognosis for women with breast cancer and CNS metastases by HER2 status. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1242–1248. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karam I, Nichol A, Woods R, Tyldesley S. Population-based outcomes after whole brain radiotherapy and re-irradiation in patients with metastatic breast cancer in the trastuzumab era. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:181. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dijkers EC, Oude Munnink TH, Kosterink JG, et al. Biodistribution of 89Zr-trastuzumab and PET imaging of HER2-positive lesions in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:586–592. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis Phillips GD, Li G, Dugger DL, et al. Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9280–9290. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junttila TT, Li G, Parsons K, et al. Trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1) retains all the mechanisms of action of trastuzumab and efficiently inhibits growth of lapatinib insensitive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:347–356. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, et al. EMILIA Study Group. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1783–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209124. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pivot X, Semiglazov V, Zurawski B, et al. CEREBEL (EGF111438): an open label randomized phase III study comparing the incidence of CNS metastases in patients (pts) with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC), treated with lapatinib plus capecitabine (LC) versus trastuzumab plus capecitabine (TC). Presented at the European Society of Medical Oncology 2012 Meeting; Vienna, Austria; 28 September–2 October; 2012. Abstract 3778. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron D, Casey M, Press M, et al. A phase III randomized comparison of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in women with advanced breast cancer that has progressed on trastuzumab: updated efficacy and biomarker analyses. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:533–543. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9885-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park YH, Park MJ, Ji SH, et al. Trastuzumab treatment improves brain metastasis outcomes through control and durable prolongation of systemic extracranial disease in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:894–900. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musolino A, Ciccolallo L, Panebianco M, et al. Multifactorial central nervous system recurrence susceptibility in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer: epidemiological and clinical data from a population-based cancer registry study. Cancer. 2011;117:1837–1846. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockman PR, Mittapalli RK, Taskar KS, et al. Heterogeneous blood-tumor barrier permeability determines drug efficacy in experimental brain metastases of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5664–5678. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartsch R, Berghoff AS, Preusser M. Breast cancer brain metastases responding to primary systemic therapy with T-DM1. J Neurooncol. 2014;116:205–206. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.