Abstract

Prior biochemical analysis of the heterodimeric vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme suggests roles not only in mRNA capping but also in early viral gene transcription termination and intermediate viral gene transcription initiation. Prior phenotypic characterization of Dts36, a temperature sensitive virus mutant affecting the large subunit of the capping enzyme was consistent with the multifunctional roles of the capping enzyme in vivo. We report a biochemical analysis of the capping enzyme encoded by Dts36. Of the three enzymatic activities required for mRNA capping, the guanylyltransferase and methyltransferase activities are compromised while the triphosphatase activity and the D12 subunit interaction are unaffected. The mutant enzyme is also defective in stimulating early gene transcription termination and intermediate gene transcription initiation in vitro. These results confirm that the vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme functions not only in mRNA capping but also early gene transcription termination and intermediate gene transcription initiation in vivo.

Keywords: vaccinia virus, capping enzyme, mRNA capping, transcription termination, transcription initiation

Introduction

The poxvirus vaccinia contains a 200 kb dsDNA genome encoding approximately 200 annotated gene products, and replicates in the cell cytoplasm (Moss, 2013). The cytoplasmic site of replication demands that the virus encode and package in the virion an entire complement of enzymes required for production of capped and polyadenylated mRNA, including a multisubunit RNA polymerase, a heterodimeric poly(A) polymerase and a heterodimeric mRNA capping enzyme. For this reason, vaccinia has a long been utilized as a simple model system for understanding basic mechanisms of mRNA metabolism. Interestingly, despite a relatively large coding capacity, vaccinia has nevertheless apparently evolved to economize on genetic content by elaborating multiple roles for several viral enzymes. Notable in this regard is the viral mRNA capping enzyme, which serves not only to cap the mRNA 5′ end, but also as an early gene transcription termination factor and an intermediate gene transcription initiation factor. Understanding the mechanisms of this multifunctionality is of intrinsic interest in the context of virus biology and evolution.

Transcription during vaccinia infection is regulated to yield three waves of gene expression: early, intermediate and late (Broyles, 2003). The viral RNA polymerase exists in two forms, one specific for early gene transcription, and one for intermediate and late (together called postreplicative) gene transcription. Both forms of the RNA polymerase contain eight core subunits. The core enzyme transcribes postreplicative genes. The early gene-specific form of the RNA polymerase contains an additional subunit, encoded by gene H4, which interacts with an early promoter-binding viral early transcription factor (Yang & Moss, 2009). Early mRNAs are synthesized from infecting virion core particles using transcription and mRNA modification enzymes packaged in the virion. Early transcripts encode both viral DNA replication enzymes and intermediate transcription factors, which together with newly synthesized viral RNA polymerase activate transcription from intermediate gene promoters on replicating viral DNA released during uncoating of the virion cores. Intermediate genes encode late transcription factors which in turn activate transcription from late gene promoters. Late genes encode virion structural proteins plus the enzymes required for early gene transcription, which are packaged into maturing virions for the subsequent round of infection.

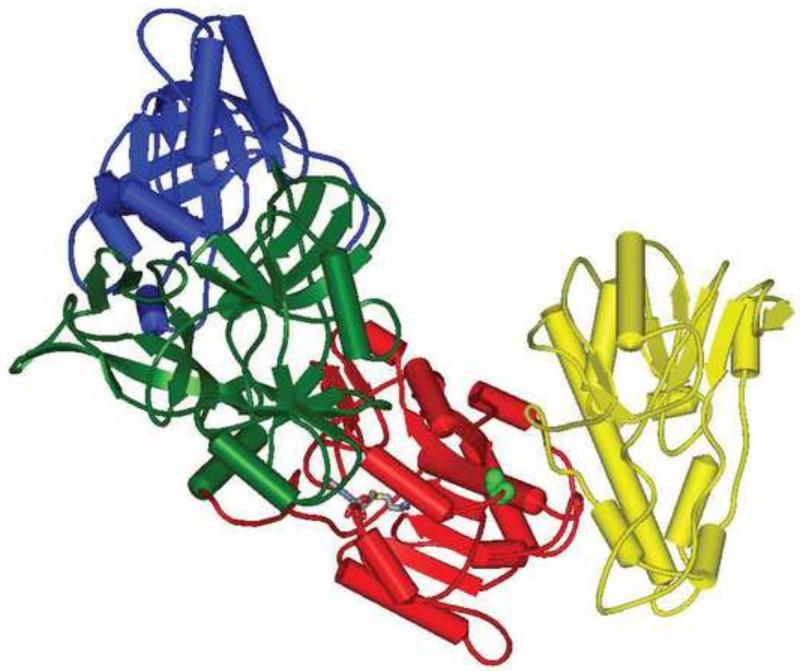

The viral mRNA capping enzyme (CE) is comprised of two subunits of 97 kDa and 33 kDa, the products of gene D1 and D12 respectively (Martin et al., 1975; Morgan et al., 1984; Niles et al., 1989; Guo & Moss, 1990). Biochemical and genetic analysis of the enzyme coupled with a recent crystal structure (Kyrieleis et al., 2014) (Fig. 1) reveal three separate and distinct catalytic domains in the D1 subunit which together carry out the three reactions (Martin & Moss, 1975; Martin & Moss, 1976; Shuman & Hurwitz, 1981) required for cap formation on a nascent 5′ triphosphorylated RNA shown below:

| I: | pppRNA →ppRNA + Pi |

| IIa: | GTP + enz → enz-GMP + Pi |

| IIb: | enz-GMP + ppRNA → GpppRNA + enz |

| III: | GpppRNA +SAM → meGpppRNA + SAH |

The first reaction, removal of the gamma phosphate from the triphosphorylated RNA to yield a 5′ diphosphorylated RNA, is catalyzed by the N-terminal RNA triphosphatase (TPase) domain of D1 (Yu & Shuman, 1996; Myette & Niles, 1996a; Gong & Shuman, 2003). The second reaction, addition of a GMP to the 5′ diphosphorylated RNA in a 5′-5′ linkage to yield an unmethylated cap structure, proceeds through a covalent enzyme GMP complex (Shuman & Hurwitz, 1981) and is catalyzed by the internal guanylyltransferase domain (GTase) of D1 (Niles & Christen, 1993; Cong & Shuman, 1995; Myette & Niles, 1996b). The third reaction, transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine to the 7 position of the cap guanine to yield a cap 0 structure and S-adenosylhomocysteine, is catalyzed by the C-terminal methyltransferase domain (MTase) of D1 (Higman et al., 1994; Mao & Shuman, 1994). The D12 subunit forms a stable complex with the methyltransferase domain of D1. D12 has no known enzymatic activity but serves to stimulate the otherwise relatively weak intrinsic methyltransferase activity of D1.

Fig. 1. Structure of the vaccinia virus capping enzyme.

Ribbon diagram representation of the structure of CE. The three domains of the large D1 subunit are represented in different colors. The TPase domain (residues 1-225) is blue, the GTase domain (residues 226-545) is green, and the MTase domain (residues 548-844) is red. The small D12 subunit is yellow. The bound S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine in the MTase active site is shown in stick models colored by element. Gly 705, which is replaced with Asp in the Dts36 mutant, is depicted in space-filling models colored light green.

The D1/D12 heterodimer is a required cofactor for viral early gene transcription termination (Shuman et al., 1987; Luo et al., 1991). Early gene transcription termination is a sequence specific event triggered by the sequence U5NU found 20-50 nt upstream of early gene 3′ ends (before polyadenylation) (Yuen & Moss, 1987). During viral early gene transcription termination, the sequence U5NU is recognized by CE via the N-terminal TPase domain of D1 (Christen et al., 2008). Termination itself is catalyzed by a DNA-dependent nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase (NPHI, gene D11), which interacts with the early form of the RNA polymerase through contacts with the early gene specific H4 subunit (Deng & Shuman, 1996; Deng & Shuman, 1998; Christen et al., 1998; Mohamed & Niles, 2000). CE can induce pausing by elongating RNA polymerase, which could theoretically provide a properly configured ternary complex of polymerase, DNA and RNA, primed for NPHI termination activity (Tate & Gollnick, 2011). The mRNA capping activity of CE is not required for early gene transcription termination, however both the D1 and D12 subunits must be present (Luo et al., 1995; Condit et al., 1996; Yu & Shuman, 1996).

CE is one of three viral factors required for intermediate gene transcription initiation (Vos et al., 1991b). The other factors are VITF1, comprised of the E4 core subunit of RNA polymerase, and VITF3, a heterodimer of the viral A8 and A23 proteins (Rosales et al., 1994; Sanz & Moss, 1999). A cellular factor consisting of G3BP and p137 has also been reported to stimulate intermediate gene transcription in vitro (Katsafanas & Moss, 2004). Formation of a stable complex between capping enzyme and RNA polymerase seems to be a prerequisite for intermediate gene transcription, otherwise little is known about the mechanism of action of intermediate gene transcription initiation factors (Vos et al., 1991a). The mRNA capping activity of CE is not required for intermediate gene transcription initiation, however both the D1 and D12 subunits must be present (Harris et al., 1993; Condit et al., 1996).

We have described previously a temperature sensitive mutant in gene D1R, Dts36, the phenotype of which suggests effects on all three roles of CE: mRNA capping, early gene transcription elongation and intermediate gene transcription initiation (Shatzer et al., 2008). Specifically, although mRNA capping was not examined directly, steady state levels of some early viral mRNAs were decreased, consistent with a defect in mRNA capping. The mutant also displayed transcriptional readthrough of early viral genes consistent with a defect in early gene transcription termination, and decreased steady state levels of specific intermediate but not late gene transcripts, consistent with a defect in intermediate gene transcription initiation. The mutation comprises a glycine to aspartic acid substitution on the surface of the MTase domain of D1, distant from either the catalytic site or the D12 interaction domain. Our goal in the work presented here was to perform a biochemical analysis of the Dts36 mutant CE in order to substantiate the phenotypic analysis and provide additional mechanistic insight into the multifunctional nature of the enzyme. We find that the mutant enzyme displays defects in both MTase and GTase activities while the TPase activity and the D12 subunit interaction are unaffected. The mutant enzyme is also defective in stimulating early gene transcription termination and intermediate gene transcription initiation in vitro. The findings are interpreted in light of the 3D structure of the enzyme.

Results

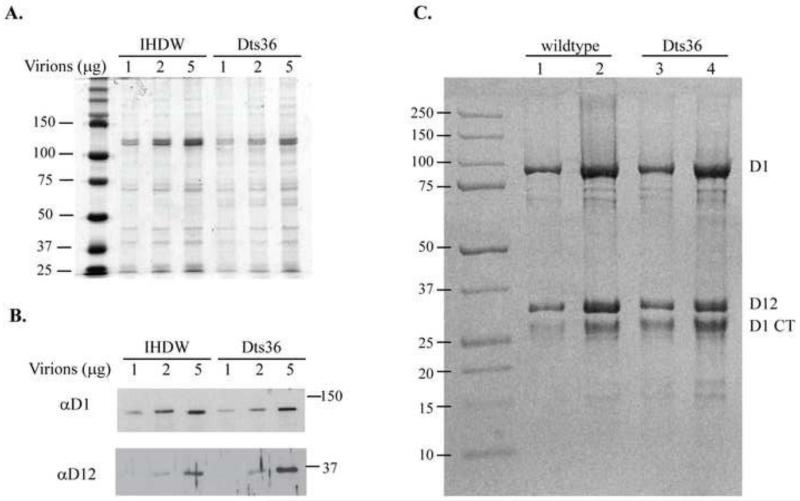

CE abundance in WT and Dts36 virions; enzyme purification

WT and Dts36 virions were purified from BSC-40 cells grown at 30°C. The overall protein content in the virion preparations was examined by SDS-PAGE analysis of varying amounts of WT virions and Dts36 virions, visualized by Coomassie stain (Fig. 2A). Similar polypeptide staining patterns were observed between WT virions and Dts36 virions, suggesting that purified Dts36 virions were comparable in protein content and abundance to that of WT virions. Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B) revealed no significant difference between WT and Dts36 virions in abundance or size of CE subunits D1 and D12.

Fig. 2. SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis of virion-encapsidated and purified CE.

Varying amounts of purified IHDW and Dts36 virions were denatured and their polypeptides separated by 11% SDS-PAGE. A) Polypeptides visualized by Coomassie stain. Protein standards in the first lane indicate the size of the polypeptides. B) Western blot of the CE subunits, D1 and D12. (Top panel) D1 was detected using anti-D1 polyclonal primary antibody followed by anti-rabbit-HRP monoclonal secondary antibody. (Bottom panel) D12 was probed using anti-D12 polyclonal primary antibody followed by anti-rabbit HRP monoclonal secondary antibody. Molecular weight markers are indicated to the right of the blot C) Recombinant wildtype and Dts36 CE proteins purified from E. coli analyzed on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue. Lanes 1 and 3 contain 3ug of each protein and lanes 2 and 4 contain 6ug of each protein. Molecular weight markers are indicated to the left of the gel, and the identities of the major bands are indicated at the right. D1 CT indicates a C-terminal proteolytic fragment of the D1 protein that is consistently observed when CE is expressed in and purified from E. coli.

WT and Dts36 CE D1 and D12 subunits were co-expressed in E. coli and affinity purified by virtue of a histidine tag on the N-terminus of the D1 subunit as described in Materials and Methods. Following the initial purification, the N-terminal tag was proteolytically removed from the D1 subunit and CE further purified by gel filtration chromatography. The proteolysis step leaves the D1 subunit with an unmodified N-terminus but also produces a D1 C-terminal fragment that was identified using antibodies specific for the N and C terminus of D1 (data not shown). The purity of the finished enzyme preparations was examined by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (Fig. 2C.)

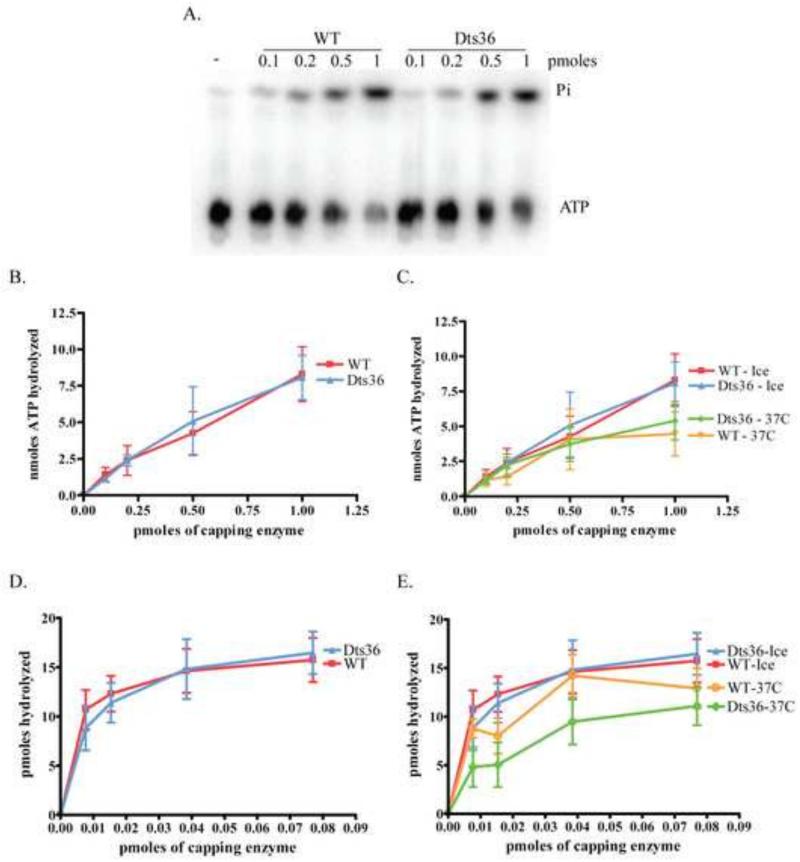

Dts36 Nucleoside Triphosphate Phosphohydrolase (TPase) Activity

As described in the Introduction, the CE TPase hydrolyzes the gamma phosphate from a nascent triphosphorylated mRNA 5′ terminus, thus priming the RNA to accept an incoming GMP for the subsequent GTase reaction (Yu & Shuman, 1996; Myette & Niles, 1996a). The TPase will also hydrolyze the gamma phosphate from free nucleotides in vitro, providing a convenient in vitro assay (Myette & Niles, 1996a).

Dts36 CE TPase activity was measured by examining the amount of ATP hydrolyzed in the presence of CE using either ATP or RNA as a substrate. Increasing amounts of either purified WT or Dts36 CE were incubated with γ32P-ATP for 15 min at 37°C. Reaction products were separated by PEI-cellulose thin layer chromatography and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 3A). The percentage of ATP hydrolyzed was calculated and plotted as a function of CE concentration (Fig. 3B). Addition of increasing amounts of either WT or Dts36 CE resulted in a linear increase in ATP hydrolyzed. No differences in ATPase activity were observed comparing the WT and mutant enzyme. TPase activity was also tested using an RNA substrate. A synthetic 25 nt 5′ gamma 32P labeled RNA was incubated with increasing amounts of either WT or Dts26 CE and liberation of 32Pi was assessed by thin layer chromatography as described in Materials and Methods (Fig 3D). The plateau observed in these titrations occurs because at high concentrations of enzyme the substrate is exhausted. Nevertheless, WT and Dts36 CE both hydrolyzed Pi from RNA with identical kinetics. These results suggest that the TPase activity of CE is unaffected by the Dts36 mutation.

Fig. 3. Dts36 TPase activity.

A) Autoradiogram of ATPase assay of WT and Dts36 CE. B) The moles of ATP hydrolyzed were determined by determining the fraction of Pi released from a known input mols of ATP. C) Analysis of the thermostability of the TPase activity of WT and Dts36 CE. Enzymes were pre-incubated for 15 min either on ice or at 37 °C after which hydrolysis of ATP was assayed as in (A) and plotted as in (B). D) TPase activity using an RNA substrate was determined by calculating the amount of Pi hydrolyzed from 5′-[32P] RNA. Pmoles hydrolyzed was plotted versus the amount of CE in the reaction. E) The thermostability of the TPase activity on an RNA substrate was analyzed by pre-incubating CE samples on ice or at 37°C for 15 minutes and then assaying TPase activity. Activity was calculated and plotted as is (D).

To examine whether Dts36 CE TPase activity is thermolabile, the ATPase assays were repeated using either ATP (Fig. 3C) or RNA (Fig. 3D) as a substrate, but with CEs that had been pre-incubated for 15 min at either 0°C or 37°C. Hydrolysis was plotted as a function of enzyme concentration. Pre-incubation at on ice did not affect either enzyme’s ATPase activity. Although both WT and Dts36 CE showed a slight decrease in activity following pre-incubation at 37°C, no significant difference in thermolability was observed comparing the two enzymes. These results suggest that the Dts36 CE mutation does not affect TPase thermolability.

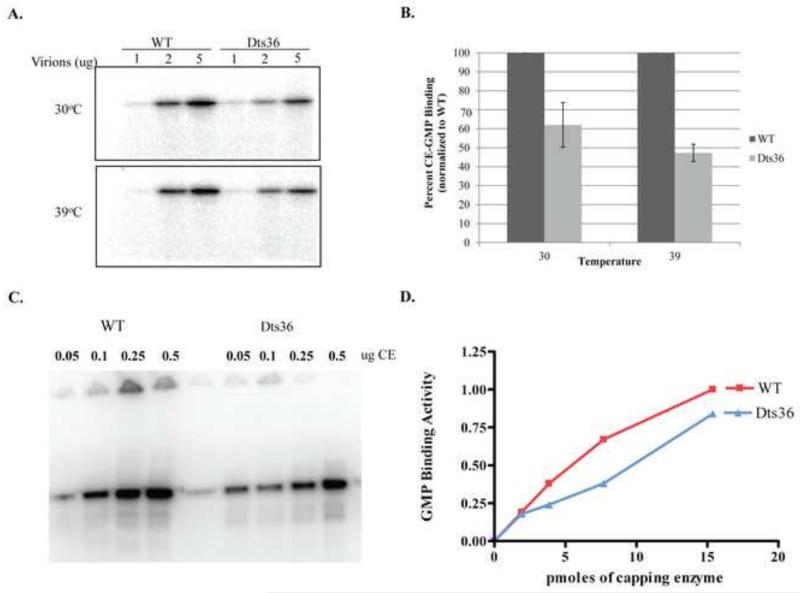

Dts36 Guanylyltransferase (GTase) Activity

As outlined in the Introduction, the GTase activity of CE comprises two partial reactions (Shuman & Hurwitz, 1981). The first reaction involves hydrolysis of GTP to GMP and formation of a covalent CE-GMP complex intermediate. CE-GMP complex formation can occur in either the presence or absence of acceptor RNA. The second reaction involves the transfer of the GMP to the 5′-diphosphate terminus of the acceptor mRNA through an inverted G(5′)ppp(5′)N linkage. This latter reaction is referred to as transguanylylation.

GTase activity in Dts36 virions was first examined by comparing the formation of the CE-GMP intermediate using permeabilized WT and Dts36 virions. CE-GMP formation was assayed by incubating increasing amounts of permeabilized virions at 30°C or 39°C in the presence of γ32P-GTP. After 15 min of incubation, the reactions were stopped with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (Fig. 4A). A single radioactive band, corresponding to the large subunit of CE (~97 kDa), was observed in the autoradiogram. The intensity of the band was proportional to the amount of virions in the reaction. Band intensity at each amount of Dts36 virions was compared to the band intensity in the corresponding WT reaction, and the relative fraction of CE-GMP complex formation was calculated (Fig. 4B). Dts36 virions were approximately 50% as active as WT in forming CE-GMP complexes at both the permissive (30°C) and non-permissive temperatures (39°C). CE-GMP complex formation was also determined using purified recombinant WT and Dts36 CE (Fig. 4C and D). Similar to the result obtained with permeabilized virions, CE-GMP complex formation using Dts36 CE was reduced to approximately 60% of the amount observed with WT CE.

Fig. 4. CE:GMP complex formation.

A) Varying amounts of permeabilized IHDW or Dts36 virions were incubated with α32P-GTP at either 30°C or 39°C for 15 min. Reactions were analyzed on a 11% SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. B) The amount of CE:GMP present was calculate by dividing the band intensity by the amount of virions present in the reaction. Percent CE:GMP was then calculated by normalizing to the amount of CE:GMP present in the corresponding reactions containing IHDW virions. (C) Varying amounts of purified WT or Dts36 CE were incubated with α32P-GTP at 30 °C for 15 min and analyzed by SDS PAGE as described in (A). (D) Plot of the amount of CE-GMP complex formed with WT and Dts36 CE. The amount of CE-GMP complex formed with 0.5 μg WT CE was set at 100%

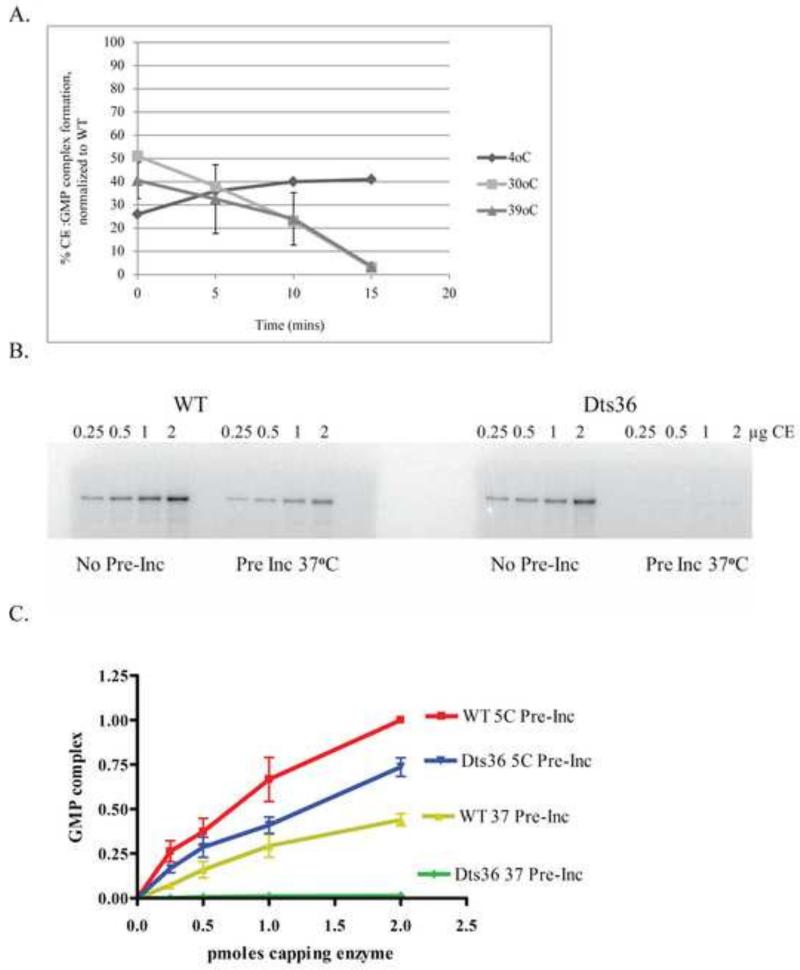

To determine whether CE-GMP complex formation was thermolabile, permeabilized virions or purified CE was pre-incubated at varying temperatures prior to incubation with γ32P-GTP (Fig. 5). Using either permeabilized virions or purified CE, the amount of Dts36 CE-GMP formation decreased relative to WT CE-GMP formation, demonstrating that the Dts36 mutation causes CE-GMP formation to be thermolabile. It seems likely that the formation of the CE-GMP complex is sufficiently rapid such that the thermolability observed upon preincubation of virions or purified enzyme (Fig. 5) is masked if reactions are done at non-permissive temperatures in the absence of preincubation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5. Thermolability of Dts36 CE:GMP complex formation.

(A) Permeabilized IHDW and Dts36 virions were preincubated at 4, 30, or 39°C for 0, 5, 10, and 15 min. These virions were then incubated with α32P-GTP at 39°C for 15 min. Reactions were analyzed on an 11% SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The amount of CE:GMP present was calculated by dividing the band intensity by the amount of virions present in the reaction. Percent CE:GMP was then calculated by normalizing to the amount of CE:GMP present in the corresponding reactions containing IHDW virions. (B) Thermolability of GMP complex formation with purified WT and Dts36 CE. Purified WT or Dts36 CE was pre-incubated at either 5°C or 37 °C for 15 min and then mixes with α32P-GTP and incubated at 30 °C for 15 min. The reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described in (A). (C) Plot of GMP complex formation from (B). The amount of complex formed with 2.0 μg WT CE pre-incubated at 5°C was set at 1.00 and the other samples normalized to this value.

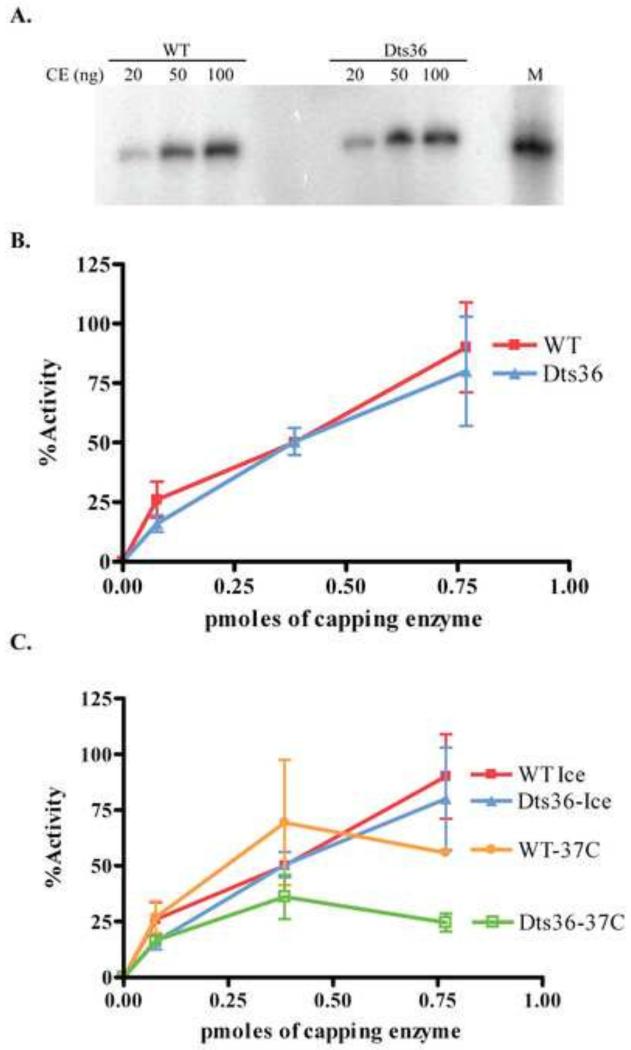

The GTase of Dts36 was next examined for transguanylylation activity. Unlabeled 5′ triphosphorylated RNA was synthesized in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase. Increasing amounts of WT or Dts36 CE were incubated with the unlabeled RNA in the presence of α32P-GTP and GTP at 37°C for 4 min. Excess GTP was included in the reactions in an attempt to overcome defects in CE-GMP complex formation detected previously. RNA was then separated by denaturing PAGE and imaged by autoradiography (Fig. 6A). The band observed represents RNA that has had a 32P-GMP transferred to its 5′ terminus. The amount of Dts36 CE transguanylylation activity was calculated as a fraction of maximum WT CE transguanylylation activity (Fig. 6B). No significant difference in transguanylylation activity was observed between WT CE and Dts36 CE under these reaction conditions. We then tested WT and Dts36 CE to determine whether the transguanylylation activity was thermolabile. WT and Dts36 CE were preincubated for 10 min on ice or at 37°C and then assayed for transfer of 32P-GMP to the 5′ triphosphorylated RNA substrate as described above (Fig. 6C). Preincubation of Dts36 CE at 37°C reduced transguanylylation activity compared to WT enzyme preincubated at either 37°C or on ice, or Dts36 enzyme preincubated on ice, demonstrating that the Dts36 CE is thermolabile for transguanylylation. Given that CE-GMP complex formation is also thermolabile, it is difficult to determine whether the transguanylylation partial reaction is specifically thermolibile as well, however in aggregate the results show that the GTase activity of the Dts36 CE is thermolabile.

Fig. 6. Dts36 guanyltransferase activity.

(A) Purified T7 synthesized RNA was incubated with α32P-GTP and either WT or Dts36 CE (20, 50, and 60 ng) at 37°C for 4 min. Samples were analyzed by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The marker lane (M) contains the same RNA used as substrate, however uniformly labeled during synthesis. (B) Plot of guanyltransferase activity from several assays as shown in (A). The activity obtained with 100 ng WT CE was set at 1.00 and the other samples normalized to this value. Values shown are the average of three independent assays each done in duplicate with error bars representing standard deviations. (C) Guanylyltransferase was assayed after preincubation of either WT or Dts36 CE for 10 min on ice or at 37°C. Reactions were analyzed and quantified as in (A) and (B).

Dts36 Methyltransferase Activity

(N7-) methylation of the 5′ guanylate cap on viral mRNA is the final reaction in the cap 0 structure formation. The viral capping enzyme (CE) methyltransferase (MTase) activity transfers a methyl group from a S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) donor to an acceptor, which can be either a 5′ guanylate capped mRNA or free GTP with a Km of 0.21 μM and 33 μM respectively (Martin & Moss, 1976; Higman et al., 1994).

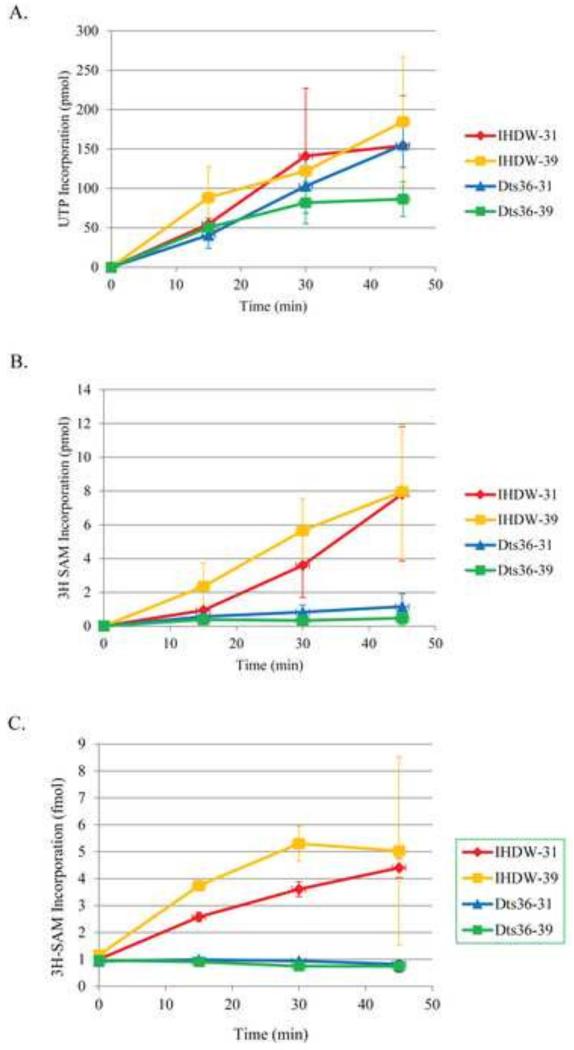

Dts36 MTase activity was first measured in the context of permeabilized virions using viral transcripts as the methyl acceptor, such that guanylylated mRNA transcribed in virions would be transmethylated concurrently with transcription. Viral transcription was performed by incubation of permeabilized virions in the presence of α32P-UTP and unlabeled SAM to monitor the amount of RNA synthesis during the incubations. Transcripts were quantified by TCA precipitation and scintillation counting (Fig. 7A). Transcription from Dts36 virions levels off after 30 min of incubation at 39°C, otherwise no significant difference in RNA synthesis was observed between reactions containing WT virions compared to reactions containing Dts36 virions, nor was a difference observed between permissive and non-permissive temperatures. Co-transcriptional transmethylation was measured by incubation of permeabilized virions in the presence of all 4 NTPs and 3H-SAM at either the permissive (30°C) or non-permissive (39°C) temperatures. Methylated transcripts, which contain a 3H radiolabeled methyl group, were quantified by TCA precipitation and scintillation counting (Fig. 7B). Reactions containing WT virions contained measurable quantities of methylated transcripts after 15 mins of incubation at either 30°C or 39°C, and methylated transcripts continued to accumulate during the entire 45 min incubation. Conversely, reactions containing Dts36 virions failed to accumulate methylated transcripts at either temperature. Given that transcription was unaffected in Dts36 virions, the absence of methylated transcripts in reactions containing Dts36 virions is likely a result of a defect in mRNA capping and not in mRNA synthesis. However, given that CE-GMP complex formation is at least partially defective under these conditions and could therefore decrease the availability of transguanylylated substrate in premeabilized virions, we sought to assess MTase independently of GTase.

Fig. 7. Methyltransferase activity in IHDW and Dts36 virions.

A) Transcription. Transcription was stimulated in permeabilized IHDW or Dts36 virions by the addition of all four nucleotides in the presence of α32P-UTP and SAM and incubation at either 30 or 39°C. A various times samples were TCA precipitated and quantified by scintillation counting. B) Transcript methylation. Transcription was stimulated in permeabilized IHDW or Dts36 virions by the addition of all four nucleotides in the presence 3H-SAM and incubation at either 30 or 39°C. A various times samples were TCA precipitated and quantified by scintillation counting. (C) GTP methylation. Permeabilized IHDW or Dts36 virions were incubated with GTP and 3H-SAM at either 31 or 39°C. A various times samples were spotted on DEAE-cellulose filters, washed to remove unincorporated 3H-SAM and quantified by scintillation counting.

Virion MTase activity in permeabilized virions was assayed independently of GTase using free GTP as the methyl acceptor. The reaction conditions were the same as for the coupled transcription MTase assays described above except that CTP, ATP, and UTP were excluded from the reaction. Following incubation, methylated GTP was quantified by binding to anion-exchange filters and scintillation counting (Fig. 7C). The results show that Dts36 virions are inactive for MTase activity at both 30°C and 39°C, unlike WT virions, which showed MTase activity at both temperatures.

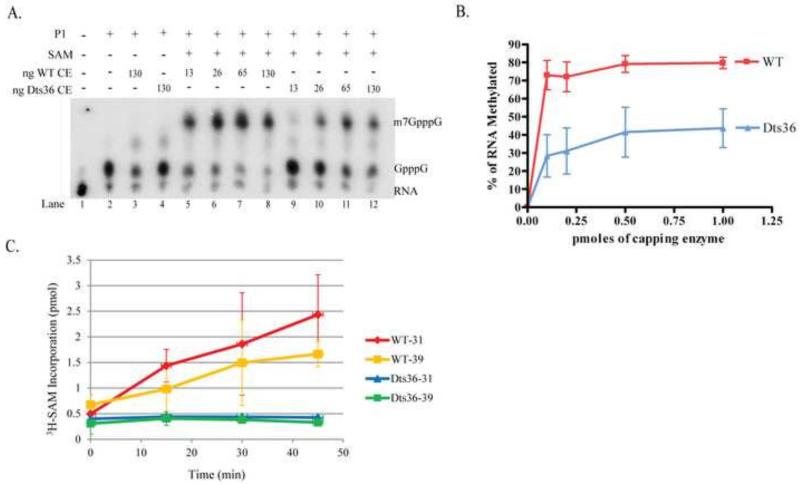

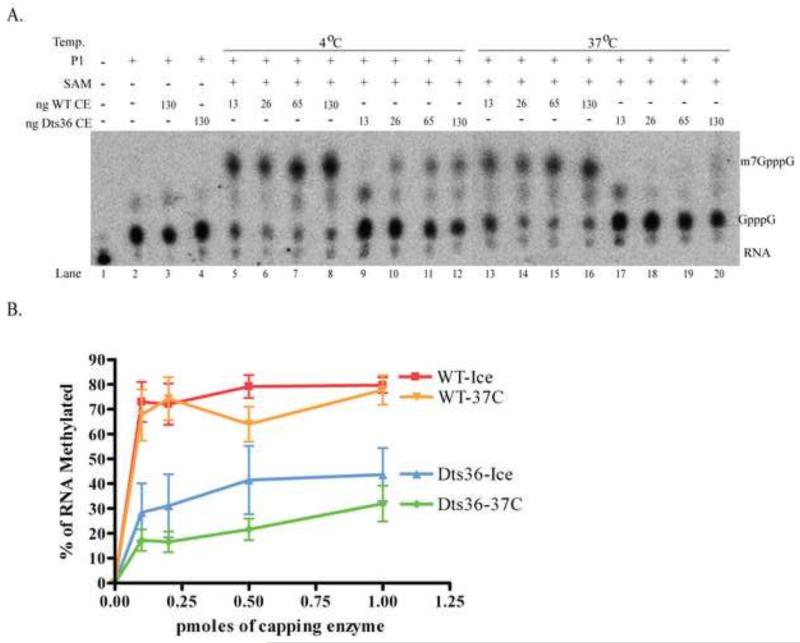

MTase activity of purified CE was assessed using an authentic RNA substrate. Unlabeled RNA was synthesized in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase and then transguanylylated using CE in the presence of α32P-GTP to yield radiolabeled, guanylylated, unmethylated substrates (G32pppNpNp….) for the transmethylation reaction. Varying amounts of purified CE were incubated with the radiolabeled guanylylated RNA at 37°C for 15 min in the presence or absence of SAM. Following incubation, the RNA was treated with P1 nuclease to cleave the 5′ cap from the RNA and the cleavage products were separated by PEI-cellulose thin layer chromatography (Fig. 8A). The percentage of transcripts methylated by either WT CE or Dts36 CE was calculated and plotted as a function of enzyme concentration (Fig. 8B). In the absence of SAM, addition of either WT or Dts36 CE had no effect on the guanylylated cap (compare Fig. 8A, lanes 3-4 and lane 2). Addition of 13 ng of WT CE and SAM resulted in ~60% of the guanylated caps being methylated (Fig. 8A, lane 5 and Fig. 8B) and MTase activity plateaued at ~80% with addition of 65 ng WT CE (Fig. 8A, lane 7 and Fig. 3B). Addition of Dts36 CE and SAM also resulted in methylated transcripts (Fig. 8A, lanes 9-12), however the Dts36 MTase activity plateaued at ~40%, half that of WT CE (Fig. 8B). Unlike previous MTase experiments using permeabilized virions (Fig. 7), these results suggest that Dts36 CE MTase activity is impaired but still active.

Fig. 8. Methyltransferase activity of purified Dts36 CE.

A) Purified T7 synthesized RNA was guanylylated using α32P-GTP and WT CE and incubated with increasing amounts of either WT or Dts36 CE and in the presence or absence of SAM at 37°C for 15 min. The 5′ caps were cleaved off the RNA with P1 nuclease. Products were resolved by PEI cellulose TLC and visualized by autoradiography. B) Percent methylation was calculated as the amount of m7GpppG divided by the sum of m7GpppG and GpppG, and plotted versus the amount of CE present in the reaction. C) GTP methylation. Purified WT or Dts36 CE was incubated with GTP and 3H-SAM at either 30 or 39°C. A various times samples were captured on DEAE-cellulose filters and the amount of 3H-labeled GTP was measured by scintillation counting. The amount of 3H incorporation is plotted as a function of time.

The apparent discrepancy in MTase activity observed between virion and purified CE could theoretically be attributed to either the different methyl acceptors employed or the different CE sources. To ensure that purified recombinant Dts36 CE behaves in a similar fashion as the Dts36 CE packaged within the virions, the previous MTase assay, which used 3H-SAM as the methyl donor and free GTP as the methyl acceptor (Fig. 8C), was repeated with purified CE. In the presence of WT CE, significant levels of methylated GTP accumulated during the 45 min incubation at both 30°C and 39°C. However, Dts36 CE failed to methylate GTP at either temperature. These results are consistent with the data obtained using permeabilized virions as the CE source, demonstrating that Dts36 CE MTase activity is comparable using permeabilized virions or purified enzyme. Therefore, the Dts36 MTase activity observed in Fig. 8 is likely attributable to the different methyl acceptors used. CE has a higher affinity for guanylylated transcripts compared to free GTP as the methyl acceptor at sub-saturating SAM concentrations. The lower affinity for GTP methylation may be exacerbating the defect in Dts36 CE MTase activity. Furthermore, the lack of measureable MTase activity in Dts36 virions when viral transcripts were used as the methyl acceptor (Fig. 7A) may be due to a defect in an upstream capping reaction such as guanylyltransferase, which is bypassed when guanylylated transcripts are synthesized in vitro (Fig. 8).

To assess whether the Dts36 CE MTase activity observed in Fig. 8 is thermolabile, WT CE and Dts36 CE were pre-incubated for 15 min at either 5°C or 37°C and then assayed for MTase using guanylylated RNA as a substrate (Fig. 9). In the absence of SAM, WT CE and Dts36 CE failed to methylate the guanylated RNAs (Fig. 9A, compare lanes 2 and 3-4). When WT CE or Dts36 CE were pre-incubated at 4°C, methylated caps were observed (Fig. 9A, lanes 5-8 and lanes 9-12 respectively) and the percentage of methylated caps was similar to previous measurements (compare Fig. 8 and Fig. 9). Pre-incubation of Dts36 CE at 37°C caused a larger percentage decrease its MTase activity compared to the WT enzyme, suggesting that the Dts36 CE MTase activity is slightly thermosensitive.

Fig. 9. Thermolability of methyltransferase activity of purified Dts36 CE.

A) Purified T7 synthesized RNA was guanylylated using α32P-GTP and WT CE. These guanylated transcripts were incubated with increasing amounts of either WT or Dts36 CE preincubated at either 4 or 37°C, and in the presence or absence of SAM at 37°C for 15 min. The 5′ caps were cleaved from RNA with P1 nuclease and products were resolved by PEI cellulose TLC and visualized by autoradiography. B) Percent methylation was calculated as the amount of m7GpppG divided by the sum of m7GpppG and GpppG, and plotted against the amount of CE present in the reaction.

Dts36 Early Gene Transcription Termination

In addition to generating the 5′ cap 0 structure on viral mRNA, vaccinia CE also functions as an early gene transcription termination factor (Shuman et al., 1987; Luo et al., 1991). Prior data suggest that the role of CE in transcription termination is to recognize the termination signal, U5NU, located in the nascent transcript (Christen et al., 2008). In vivo studies of Dts36 revealed that early transcripts were abnormally long and had increased heterogeneity in their 3′ termini, suggesting a defect in early gene transcription termination (Shatzer et al., 2008). To confirm this hypothesis, in vitro early transcription termination assays were performed using purified Dts36 CE.

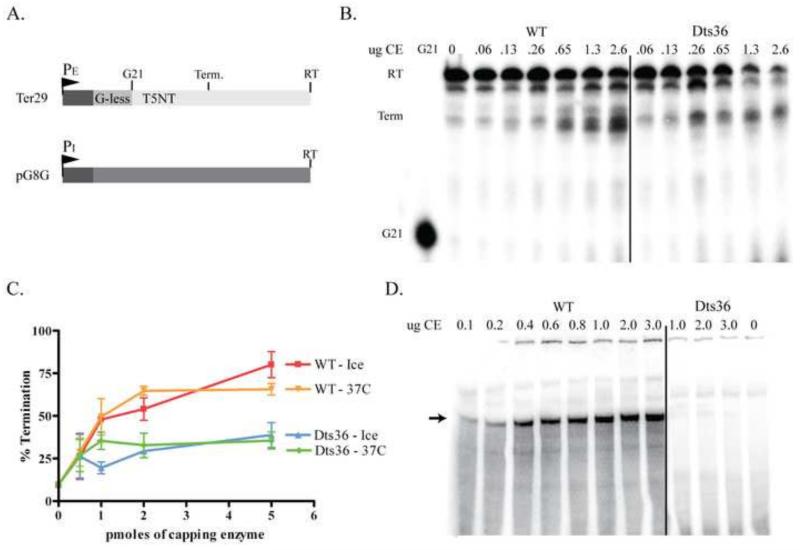

Transcription termination assays were carried out using an artificial early gene template, Ter29, attached to paramagnetic beads. The Ter29 template contains a strong synthetic vaccinia early promoter driving transcription through a 20 bp G-less cassette followed by a 169 bp of nonspecific DNA (Fig. 10A). The T5NT sequence, which acts as the transcription termination signal when transcribed into U5NU, is located 8 bp downstream of the G-less cassette. When U5NU is extruded from the transcription elongation complex, CE recognizes the termination signal and stimulates transcription termination to occur ~75 nt downstream from the start of transcription. In the absence of CE, the transcription elongation complex does not terminate in a signal-dependent manner but rather transcribes to the end of the DNA template to produce a 189 nt read-through (RT) transcript.

Fig. 10. Dts36 activity in in vitro transcription termination and initiation.

A) Diagram of the transcription templates Ter29 and pG8G. Ter29 contains an early gene promoter (PE) followed by a 20 bp G-less cassette and 169 bp of random sequence. Readthrough transcripts (RT) proceed to the end of the template to yield 189 nt transcript. The termination signal, T5NT, is located 9 bp downstream of the G-less cassette and stimulates termination to occur ~55 bp downstream of the G-less cassette to yield a ~75 nt terminated transcript (Term). Template pG8 contains an intermediate gene promoter (PI) followed by 380 bp G-less cassette (RT). B) Early transcription termination. Ter29 templates were incubated with ATP, CTP, α32P-UTP, 3′O-Methyl GTP, and virion extracts at 30°C for 15 min, which results in transcription elongation complexes stalled at G21 (leftmost lane). Stalled complexes were washed to remove endogenous CE and nucleotides. All four nucleotides and increasing amounts of either WT or Dts36 CE were added to the reactions, and transcription was allowed to proceed past G21 by incubating at 30°C for 15 min. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing PAGE and autoradiographed. Two predominant groups of transcripts, RT and Term, are observed. C) Percent termination was calculated by dividing the amount of Term transcripts by the sum of RT and Term transcripts. Percent termination was then plotted against the amount of CE. D) Intermediate transcription initiation. pG8 templates were incubated with ATP, GTP, CTP, α32P-UTP, purified His-A24 RNA Polymerase, VITF-3 and increasing amounts of either WT or Dts36 CE at 30°C for 30 min. Reactions were analyzed by denaturing PAGE and autoradiographed. The arrow indicates the expected 350 nt transcription product.

Transcription was initiated by the addition of virion extract, ATP, CTP, α32P-UTP, and 3′O-Methyl-GTP to bead-bound Ter29 template and incubation for 15 min at 30°C. Under these reaction conditions, radiolabeled 21 nt transcripts were synthesized and the ternary elongation complex was halted at G21. Elongation complexes were washed with reaction buffer to remove unincorporated nucleotides and endogenous CE. After washing, all four NTPs and either WT or Dts36 CE were added to the reactions and transcription continued past G21. Resulting transcripts were separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, visualized by autoradiography and the autoradiograms quantified (Fig. 10B, C). Two major bands were observed. The uppermost doublet represents full length (~189 nt) RT transcripts, and the lower band represents terminated transcripts (Term) (~75 nt). In the absence of exogenous CE, the majority of radiolabeled products were RT transcripts, with only ~10% of the products being terminated transcripts. As increasing amounts of WT CE were added to the reactions, the percentage of terminated transcripts (Term) increased from ~10% to ~80%. When increasing amounts Dts36 CE were added to the reactions, the percentage of terminated transcripts only increased from ~10% to ~30%, demonstrating a defect in the ability of Dts36 CE to stimulate early gene transcription termination.

Dts36 Intermediate Gene Transcription Initiation

Vaccinia capping enzyme is also required for initiation of intermediate gene transcription, along with the Vaccinia Intermediate Transcription Factor 3 (VITF-3) (Vos et al., 1991b; Sanz & Moss, 1999). The role of either protein in transcription initiation remains unclear. Phenotypic studies of Dts36 virus demonstrated that intermediate gene expression was diminished during infection at non-permissive temperatures with this virus, suggesting the G705D mutation in Dts36 CE compromises its role in intermediate transcription initiation (Shatzer et al., 2008). To test this hypothesis, in vitro intermediate transcription assays were examined for RNA synthesis in the presence of either WT or Dts36 CE. A linearized plasmid (pG8G) containing the vaccinia intermediate gene G8R promoter followed by a ~380 bp G-less cassette was used as an artificial intermediate gene template in these assays. Reaction mixtures contained the pG8G template, CTP, ATP, UTP, and α32P-UTP. Purified vaccinia RNA polymerase, VITF-3, and either WT or Dts36 CE were added to the reaction mixtures and incubated at 30°C for 15 mins. Transcripts were isolated by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 10D). At all concentrations of WT CE, the reactions resulted in the expected 350 nt transcript. Conversely, the 350 nt transcript was not observed in reactions containing Dts36 CE, regardless of the concentration used, nor were shorter transcripts observed. These results show that the Dts36 mutant capping enzyme is defective in stimulating intermediate gene transcription, presumably via a defect in its previously described activity in transcription initiation.

Dts36 Subunit Association

D1 TPase and GTase activity can be observed in the absence of the D12 subunit, however the D1-D12 subunit interaction is required for full MTase activity of CE (Higman et al., 1994; Mao & Shuman, 1994). In addition, both subunits must be present in order for CE to function as a viral early gene transcription termination factor or a viral intermediate gene transcription initiation factor (Condit et al., 1996). Since Dts36 CE is impaired in MTase, early gene transcription termination and intermediate gene transcription initiation, one unifying hypothesis to these defects is that the G705 mutation disrupts or weakens the D1-D12 association. We therefore tested for D1-D12 subunit interaction in the Dts36 mutant capping enzyme using co-immunoprecipitation of affinity tagged D1 and D12 proteins synthesized in vitro in a reticulocyte lysate and observed no defect in D1-D12 subunit association in the mutant enzyme compared to WT (data not shown). Importantly, purification of WT and Dts36 CE overexpressed in E. coli reproducibly yielded enzymes with comparable ratios of D1 to D12 subunits (Fig. 2C). We conclude that the G705D mutation does not significantly affect CE subunit dimerization.

Discussion

All of the original studies elucidating the activities of the vaccinia virus capping enzyme (CE) were purely biochemical in nature. The enzyme was originally purified from vaccinia virions based on its ability to cap a nascent RNA transcript in vitro (Shuman et al., 1980). Numerous subsequent biochemical studies defined the three enzymatic domains of the large D1 subunit of the CE heterodimer, TPase, GTase and MTase, and delineated the MTase stimulatory role of the small D12 subunit (see Introduction for references). These studies culminate in the recent elegant atomic structure of the enzyme, clearly demonstrating the organization of the capping activities into three contiguous domains, and the association of the D12 subunit with the MTase domain (Kyrieleis et al., 2014). In parallel with characterization of the mRNA capping activities of CE, purification from virions of an activity required for early viral gene transcription termination in vitro yielded CE as the viral termination factor (VTF) (Shuman et al., 1987). Remarkably, purification from infected cells of an activity required for initiation in viral intermediate gene transcription in vitro once again yielded CE (Vos et al., 1991b). While in aggregate these studies suggested that CE functions not only to cap viral mRNA but also to terminate early gene transcription and initiate intermediate gene transcription, evidence for the multifunctional role of CE in vivo was lacking until the phenotypic characterization of Dts36, a vaccinia virus temperature sensitive mutant bearing a missense mutation in the D1 subunit of CE (Shatzer et al., 2008). The phenotype of this mutant was consistent with CE playing a role in mRNA capping, early gene transcription termination and intermediate gene transcription initiation, however some of the evidence was of necessity circumstantial. Under non-permissive conditions, the mutant clearly produced 3′ extended early mRNAs consistent with a defect in early gene transcription termination. Some early mRNAs were decreased in abundance, consistent with a defect in mRNA capping, however cap formation in vivo was not assessed directly. Steady state levels of intermediate gene transcripts were selectively reduced relative to late gene transcripts, however a specific defect in intermediate gene transcription initiation was not demonstrated. With the biochemical characterization of CE encoded by Dts36 presented here, the circle is closed. We report that the Dts36 CE is defective in both GTase and MTase but not TPase in vitro, consistent with an mRNA capping defect in vivo, and we report that the Dts36 CE is defective in viral early gene transcription termination and viral intermediate gene initiation in vitro, consistent with defects in these same processes in vivo. We can now state with confidence that the vaccinia CE does indeed play a role in all three processes during virus infection.

Based on the nature of the mutation in Dts36 and the specifics of the defects in mRNA capping described, we can speculate on the mechanism of temperature sensitivity in the mutant enzyme. The mutation comprises a change from glycine to aspartic acid at position 705 in the methyltransferase domain of the D1 subunit of CE. G705 is conserved in all poxviruses and cellular cap methyltransferases as well as Shope fribroma virus and African swine fever virus (Mao & Shuman, 1994; Schwer & Shuman, 2006). G705 is on the surface of the enzyme, comprising part of beta strand 5 (701-712) which is a well conserved feature of an ordered seven stranded beta-sheet characteristic of class I methyltransferases (de la Pena et al., 2007). Importantly, in the 3D structure of CE, G705 is significantly removed from both the MTase active site (represented by the SAH binding site in Fig. 1) and is also distant from the D1/D12 interaction surface. The G705D mutation does not measurably affect the D1/D12 subunit interaction or the activity of the TPase, however both MTase and GTase activity are compromised. The magnitude of the defect in MTase and GTase depends somewhat on the assay used for activity. Thermolability of both activities can be demonstrated, consistent with the temperature sensitive character of the mutant virus in vivo. The simplest mechanistic explanation for the effects of the G705D mutation is that it causes a conformational change in the MTase domain that propagated laterally into the GTase domain and exacerbated by elevated temperature, thus compromising both MTase and GTase activities while leaving TPase activity and D1/D12 subunit interaction unaffected.

The effects of the G705D mutation on capping provide some insight into the mechanism of action of CE in early viral gene transcription termination and intermediate viral gene transcription initiation. Previous studies demonstrate that mRNA capping is not required for CE activity in early viral gene transcription termination and intermediate viral gene transcription initiation, however both the D1 and D12 subunits must be present (Harris et al., 1993; Luo et al., 1995; Yu & Shuman, 1996; Condit et al., 1996). As described in the Introduction, during early viral gene transcription termination CE is responsible for recognition of the U5NU termination sequence via an apparent interaction with the TPase domain (Christen et al., 2008). Our results show that the TPase activity of Dts36 CE is intact, implying that the TPase domain of the Dts36 CE is unaltered, suggesting that the sequence recognition activity of CE in early termination may be unimpaired. Given that the conformation of the MTase and GTase domains are altered, we speculate that the mechanism by which CE effects early gene transcription termination must involve an interaction between the MTase and/or GTase domains and another factor involved in termination, namely RNA polymerase, H4 or NPHI. CE interaction with RNA polymerase has been demonstrated in two laboratories (Broyles & Moss, 1987; Hagler & Shuman, 1992). As noted in the introduction, the mechanism by which CE stimulates intermediate gene transcription initiation apparently involves formation of a complex between CE and RNA polymerase (Vos et al., 1991a). Our results suggest that this interaction may involve the MTase and/or GTase domains of CE. Given that the two transcription reactions, early gene termination and intermediate gene initiation, have only CE and RNA polymerase in common, it is amusing to speculate that the two reactions have in common the same interaction between RNA polymerase and the MTase and or GTase domains of CE. Hopefully, future studies will provide a detailed mechanistic picture of the role of CE in transcription.

Materials and Methods

Virion purification and virion extract preparation

Wild type vaccinia virus strain IHDW and the temperature sensitive mutant Dts36 have been described previously (Shatzer et al., 2008). For purification, virus was grown on BSC-40 cells at 30°C (the permissive temperature for Dts36) as described (Shatzer et al., 2008). Virus was purified from cytoplasmic extracts of infected cells by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion followed by banding on potassium tartrate equilibrium density gradients as previously described (Moussatche & Keller, 1991). The purified virions were quantified by optical density at 260 nm (1 OD260 = 64 μg virus). Extracts for early gene transcription reactions were prepared from purified virions as described previously (Tate & Gollnick, 2011).

Construction of vA24his

Vaccinia virus gene A24R encodes the second largest subunit of the viral RNA polymerase. A recombinant vaccinia virus, vA24his, was constructed containing a 10 × histidine tag fused to the C terminus of gene A24R, followed by GFP expressed from a synthetic vaccinia early/late promoter to facilitate screening for recombinant virus. In WT WR, a fragmented copy of the non-essential A-type inclusion (ATI) gene lies immediately downstream of A24R in the opposite orientation relative to A24R. A PCR fragment designed for insertion of the desired sequences was constructed from three precursor PCR fragments. Fragment 1 (531 bp) containing the C terminal 0.5 kb of gene A24R with the 10 × his sequence fused to the C terminus of A24R was amplified from genomic vaccinia virus strain WR DNA using a downstream primer that included the added synthetic 10 × his sequence. Fragment 2 (935 bp) containing GFP driven by a synthetic early/late vaccinia virus promoter was amplified from the plasmid pSC65-gfp-PCT (a gift of Dr. Peter Turner, University of Florida) using an upstream primer encoding the 10 × his tag to overlap fragment 1, and a downstream primer containing sequences from the vaccinia virus ATI gene. Fragment 3 (545 bp) containing the C terminal 0.5 kb of the ATI gene was amplified from genomic vaccinia virus strain WR DNA using an upstream primer containing both GFP and ATI sequences designed to overlap the downstream end of fragment 2. The three fragments were mixed and amplified using the outermost primer pair to yield a single fragment of 1920 bp. This fragment was transfected into WT vaccinia virus strain WR infected BSC40 cells, and lysates from the infected, transfected cells were screened for formation of green fluorescent plaques. Virus from green plaques was repeatedly plaque purified, grown and the relevant region was sequenced to confirm the accuracy of the construction.

Cloning genes for recombinant vaccinia proteins

Capping Enzyme (CE) was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with pET26Smt3D1R-D12L. This plasmid contains the vaccinia D1R and D12L genes, which encode the large and small subunits respectively of CE. The D1 coding segment is in-frame with the yeast SUMO protein Smt3, which contains 10 His codons at the N-terminus and is expressed from a T7 promoter in the plasmid. The D12L gene is expressed from its own T7 promoter.

To create pET26Smt3D1R/D12L, the D1R coding segment was amplified by PCR from Pet3D1R-63 (generously provided by Dr. Edward Niles). The primers used incorporated BglII and HindII sites into the 5′ and 3 ends of the gene respectively. The resulting dsDNA fragment was digested with BglII and HindIII and ligated into pET26Smt3 digested with BamHI and HindIII. This ligation results in D1 being in frame with Smt3 following the Gly-Gly motif near the C-terminus of the coding segment (Generous gift from Dr. Kiong Ho). The resulting plasmid was named pET26Smt3-D1R.

The D12L gene was amplified from pET3aD12L-8 (Generous gift from Dr. Edward Niles). The upstream primer was complementary to the plasmid upstream of the T7 promoter and incorporated a NotI site upstream of the promoter. The downstream primer bound to the 3′ end of the D12L gene and incorporated an XhoI site following the stop codon. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with NotI and XhoI and ligated into similarly digested pET26Smt3-D1R yielding plasmid pET26Smt3D1R/D12L.

To create pET26Smt3D1R(G705D)/D12L, the G705D mutation in the D1R sequence was incorporated into pET26Smt3D1R/D12L using the QuikChange site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

The Dts36 mutation in pET26Smt3D1R(G705D)/D12L is in a D1R sequence derived from a WR virus strain background, while the Dts36 mutation exists originally in an IHDW virus strain background. The D1R sequence from IHDW possesses three coding polymorphisms relative to the WR D1R sequence: V5I, T202K, and R812K (Shatzer et al., 2008). To control for potential effects of these polymorphisms, the D1R sequence of pET26Smt3D1R(G705D)/D12L was altered to match the IHDW Dts36 sequence by incorporating the V5I, T202K and R812K sequence changes using the QuikChange site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). This IHDW Dts36 CE was purified as described below and compared to WR Dts36 enzyme in early gene transcription termination, ATPase, GMP binding, and methyltransferase assays. In all assays the IHDW Dts36 enzyme had the same levels of activity as the WR Dts36 enzyme.

Purification of recombinant vaccinia proteins

WT and Dts36 CE

Six liters of BL21(DE3) cells transformed with either pET26Smt3-D1R/D12L or pET26Smt3-D1R(G705D)/D12L were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin at 37°C to an A600 of 0.6. Cells were chilled on ice for 30 min and ethanol was added to final concentration of 1%. Cells were harvested after additional 18 hr at 18°C and resuspended in 40 mL of Lysis Buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% SDS, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM PMSF). Following 2 passages through a French Press, the cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 20 min. Cleared lysates were incubated with Ni-agarose beads at 4°C for 1 hr. Beads were washed with Binding Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA), followed by Wash Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5 M NaCl, 60 mM Imidazole (pH 8)). Smt3-D1/D12 was eluted from the Ni-Agarose beads with Elution Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 0.5 M NaCl, 1 M Imidazole pH 8). The eluted Smt3-D1/D12 was treated with 1:50 molar ratio of ULP1 enzyme to cleave off the Smt3-His tag from D1. The cleavage reaction was concurrent with dialysis in Buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM NaCl) overnight at 4°C. ULP1-cleaved Smt3 was separated from D1/D12 using S-200 size exclusion chromatography. Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay with BSA as standard.

VITF-3

The plasmid encoding a recombinant VITF-3, pHisA8R-A23R, was a generous gift from Dr. Bernard Moss. VITF-3 was purified from 5 L of BL2(DE3) cells transform with the above plasmid and was prepared as described (Sanz & Moss, 1999).

A24his viral RNA Polymerase

Six liter batches of HeLa S3 cells in suspension were infected with vA24his at moi=5 for 18 hr at 37 degrees, and washed cell pellets were stored at −80°C as previously described (Kay et al., 2013). All purification procedures were performed at 4°C. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared as follows. Pellets were thawed and resusupended in 2 packed cell volumes of low salt buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)), incubated 10 min and Dounce homogenized 30-50×. Homogenates were centrifuged at 3200 × g for 30 min. Supernatants were decanted and saved and the pellets resuspended in 1 packed cell volume low salt buffer and centrifuged 3200 × g for 15 min. The supernatants were combined and adjusted to 50 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol. Extracts were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 hr and the supernatnant decanted, adjusted to 0.5% NP40, flash frozen and stored at −80°C. Protein purification was done on extracts prepared from 18 L of infected cells. Extracts from 3 × 6 L cytoplasmic extract preparations were thawed, pooled, adjusted to 20 mM imidazole and filtered through a 0.45 μM filter. Extract was applied to a 5 ml HisTrap column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The column was washed with 20 column volumes of Buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 2 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)) containing 1 M NaCl and 20 mM imidazole. The column was then washed with 20 column volumes buffer A containing 1 M NaCl and 60 mM imidazole, followed by 20 column volumes of buffer A containing 100 mM NaCl and 60 mM imidazole. Bound polymerase was eluted in 1 ml fractions with 20 column volumes buffer A containing 100 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole. Fractions representing a peak of absorbance at OD280 were pooled and dialyzed into 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 (titrated with KOH), 100 mM KOAc, 1 mM DTT, 15% glycerol and flash frozen in small aliquots at −80°C. Analysis of the affinity purified RNA polymerase by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining and by western blotting shows that the preparation is still impure but does not contain detectable amounts of intermediate gene transcription initiation factors, including CE (data not shown).

Western Blotting

Virion proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by protein transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, as described (Towbin et al., 1979). Polyclonal antibodies against D1 and D12 were generously provided by Dr. Edward Niles and used at a 1:2000 dilution. The primary antibodies were detected using polyclonal anti-rabbit conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a 1:10,000 dilution. The secondary antibodies were visualized using Amersham ECL Western Blot Detection kit as per manufacturer’s instructions.

TPase Assay

ATP substrate

TPase assays with purified WT or Dts36 CE were carried out at 37°C for 15min in 10 uL reactions containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, and 16.6 nM γ32P –ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer). 2 uL of each reaction was spotted on a PEI-Cellulose TLC plate, which was developed with 0.5M LiCl and 1M formic acid (Myette & Niles, 1996b). Plates were dried and reaction products were quantified using a phosphoimager.

RNA substrate

RNA consisting of 5 repeats of the sequence GAGUU (GAGUU-5) was used as a substrate for RNA triphosphatase assays.γ-32P-labeled GAGUU-5 was synthesized as previously described (Myette and Niles, 1996). Transcription reactions containing 400 μg of linearized plasmid DNA, 1 mM ATP, CTP, and UTP, 0.5 mM GTP, 0.25 mCi of [γ-32P]GTP (6000 Ci/mmol) and 500 units of T7 RNA polymerase per 1 ml of reaction were incubated 2 h at 37°C. The RNA products were gel purified from an 8% acrylamide, 8M urea gel. Assays contained 2 mM MgCl2 and 3 μM γ-32 P -labeled RNA in a 10-μl reaction volume. Reactions were incubated for 2 min at 37°C and 2 μl were spotted onto PEI-cellulose TLC plates. Plates were developed in 0.75M KH2PO4, pH3.4. Reaction products were quantified using a phosphoimager.

CE-GMP complex formation

CE-GMP complex formation in the context of permeabilized virions was assayed by incubating varying amounts of purified WT or Dts36 virions in 16 ul reaction mixtures containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 10 mM DTT, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 uCi α32P-GTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer). Reactions were incubated either at 30°C or 39°C for 15 min. Products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography (Shuman & Moss, 1990). Thermolability of CE-GMP formation in permeabilized virions was analyzed in a similar fashion except virions were pre-incubated at 4°C or 39°C for various lengths of time in reaction buffer lacking GTP. Following pre-incubation, GTP and α32P-GTP were added to the reactions and reactions were incubated at 39°C for 10 min.

CE-GMP complex formation using purified CE was assayed by titrating purified WT or Dts36 CE in 15 ul reaction mixtures containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 uM unlabeled GTP and 3 uCi α32P-GTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer). Reactions were incubated at 30°C or 37°C for 15 min, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography (Shuman & Moss, 1990). Thermolability of CE-GMP formation by purified CE was analyzed as above except WT or Dts36 CE was pre-incubated at 4°C or 37°C for 15 min.

Transguanylylation assays

RNA, (GAGUU)11, was synthesized using T7 polymerase. Transcripts were isolated by PAGE, eluted, and quantified. WT or Dts36 CE was incubated in reaction mixtures containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM DTT, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM GTP, 5.5 μM 55-mer RNA, 33 nM α32P-GTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer) in a final volume of 15 uL. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 4 min. Samples were analyzed by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Methyltransferase assays

Viral transcripts as methyl acceptor

Methyltransferase activity in permeabilized virions was assessed by measuring the transfer of 3H-labeled S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) methyl group to viral transcripts synthesized and guanylylated within the virions as described (Gershowitz & Moss, 1979). 2.7 μg of purified virions were incubated in 100 uL reactions containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM CTP, 1 mM GTP, 1 mM UTP, and 3.7 uCi 3H-SAM (18 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer) at 30°C or 39°C. At various times, 20 uL samples were removed into 1 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Precipitated RNA was collected on glass microfiber filters (Whatman) and unincorporated radioactivity was removed by washing with 5% TCA. Filters were analyzed by liquid scintillation counting. Concurrent transcription reactions contained 2.7 μg of purified virions in 100 uL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM CTP, 1 mM GTP, 0.20 mM UTP and 12.5 uCi α32P-UTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer). Transcription reactions were incubated at either 30°C or 39°C. At various times, 20 uL samples were analyzed by TCA precipitation as described above.

GTP as methyl acceptor

Methyltransferase activity in permeabilized virions using GTP as a methyl acceptor (Shuman & Moss, 1990) was measured by incubating 2.7 μg of purified virions in 100 uL of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10 mM DTT, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM GTP, and 5 uCi 3H-SAM (18 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer) at 30°C or 39°C. At various times, 20 uL samples were removed and spotted on DE81 filter paper (Whatman). Unincorporated radioactivity was removed by washing with 0.5 M Na2HPO4. Radioactive GTP retained on the filter was analyzed by liquid scintillation counting. Methyltransferase activity of purified capping enzyme was assayed in identical reactions except that virions were replaced with 162 ng purified capping enzyme per 100 ul reaction.

T7 transcripts as methyl acceptor using purified CE

RNA, (GAGUU)11, was synthesized using T7 polymerase and guanylylated using WT CE following the transguanylyation protocol described above. WT CE was deactivated by incubating reactions at 60°C for 5 min. Guanylylated RNA was isolated by passage through three sequential 1 ml G-50 size exclusion columns. WT or Dts36 CE was titrated in reactions containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 680 nM guanylylated RNA in the presence or absence of 50 μM SAM. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 15 mins. The 5′ caps were cleaved off the RNA with P1 nuclease in the presence of 0.1 M NaOAc (pH 5.5) at 50°C for 1 hr. Products were resolved by PEI cellulose TLC in 0.7 M LiCl. Thermoliability assays followed the above procedure with the exception that WT CE and Dts36 CE were preincubated at 37°C for 15 min.

Transcription assays

Template preparation for in vitro transcription assays

Ter29 is a synthetic DNA template (Fig. 10A) for in vitro early gene transcription studies of vaccinia early genes (Deng et al., 1996) generously provided by Dr. Edward Niles. The template consists of a strong early gene promoter fused to a 20 base-pair G-less cassette. The G-less cassette is followed by a 169 base-pair of random sequence that begins with four G residues, and contains a stretch of 9 T residues beginning at +29, which acts as the termination signal when transcribed into RNA. The Ter29 template for in vitro transcription was generated by PCR amplification of the Ter29 plasmid using the M13 forward primer and the M13 reverse primer with a biotin on the 5′ end. The amplified linear double-stranded templates were isolated using 1% agarose gels followed by extraction using the Qiagen spin-column kit as per manufacturer’s instructions. Purified templates were bound to streptavidin coated paramagnetic beads (Promega) and stored in DEPC-treated water at 4°C.

pG8G is a synthetic DNA template (Fig. 10A) for in vitro intermediate gene transcription (Condit et al., 1996). The template consists of the G8R intermediate gene promoter fused to a 350 base-pair G-less cassette. The template was linearized by digestion with HindIII. Linearized plasmid was isolated using 1% agarose gels followed by extraction using the Qiagen spin-column kit as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Early gene transcription termination assay

Transcription termination assays involved a two-step, pulse-chase reaction as described previously (Hagler et al., 1994; Deng et al., 1996). Step 1 of transcription was conducted with 1 mM ATP, 1 mM CTP, 5 μCi α32P-UTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer), 100 fmol template, and 0.5 uL of virion extract in transcription buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 6 mM MgCl2, 2mM DTT, 8% glycerol). Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 15 minutes. This step results in transcription initiation and elongation to the end of the G-less cassette to yield stable transcription elongation complexes (TEC) containing a 21 nucleotide radiolabeled transcript. TECs stalled at G21 were washed three times in transcription buffer by drawing aside the bead-bound templates with a magnet, removing the reaction buffer and re-suspending the beads in transcription buffer. Step 2 of transcription consisted of a 20 uL reaction containing 1 mM CTP, GTP, UTP and ATP in transcription buffer. Reactions were incubated for 15 minutes at 30°C. Where indicated, WT or Dts36 CE was added at the onset of Step 2 of transcription. Reactions were stopped with 20 uL 95% formamide, boiled, and subjected to denaturing PAGE. The resulting RNAs were visualized by autoradiography. Termination on the Ter29 template produces transcripts of ~75 nt, and ternary complexes that fail to terminate yield 189 nt runoff transcripts. Percent termination was calculated as the fraction of terminated transcripts in the supernatant compared to the sum of the terminated transcripts and the read-through transcripts.

Intermediate gene transcription assay

Intermediate transcription assays of WT or Dts36 CE activity contained 0.8 mM ATP, 0.8 mM CTP, 6 uCi α32P-UTP, 10 μM UTP, 0.4 μg pG8G, 2 μg VITF-3 and 6 μg vaccinia RNA polymerase in 25 uL of transcription buffer (see above). (In our hands neither VITF-1 nor the cellular factor are required for optimal intermediate gene transcription in vitro. A manuscript detailing these observations is in preparation.) Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 15 min and stopped with 25 uL of 95% formamide. Transcripts were isolated by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. In these reactions, which lack GTP, transcription stops when the TECs reach the end of the G-less cassette, yielding a ~350 nt transcript.

Statistical analysis

For all graphs in which error bars are shown, the experiments were repeated a minimum of three times and the values shown represent averages plus and minus standard deviations.

Highlights.

The vaccinia virus ts mutant Dts36 encodes a mutant mRNA capping enzyme

The Dts36 capping enzyme is defective in two of three mRNA capping reactions

The Dts36 capping enzyme is defective in early gene transcription termination

The Dts36 capping enzyme is defective in intermediate gene transcription initiation

Acknowledgements

We thank Ed Niles for antibodies and Christopher Menster for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI18094 to RCC and NSF grant MCB 1019969 to PG.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Broyles SS. Vaccinia virus transcription. J.Gen.Virol. 2003;84:2293–2303. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18942-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles SS, Moss B. Sedimentation of an RNA polymerase complex from vaccinia virus that specifically initiates and terminates transcription. Mol.Cell Biol. 1987;7:7–14. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen LA, Piacente S, Mohamed MR, Niles EG. Vaccinia virus early gene transcription termination factors VTF and Rap94 interact with the U9 termination motif in the nascent RNA in a transcription ternary complex. Virology. 2008;376:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen LM, Sanders M, Wiler C, Niles EG. Vaccinia virus nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I is an essential viral early gene transcription termination factor. Virology. 1998;245:360–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit RC, Lewis JI, Quinn M, Christen LM, Niles EG. Use of lysolecithin-permeabilized infected-cell extracts to investigate the in vitro biochemical phenotypes of poxvirus ts mutations altered in viral transcription activity. Virology. 1996;218:169–180. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong P, Shuman S. Mutational analysis of mRNA capping enzyme identifies amino acids involved in GTP binding, enzyme-guanylate formation, and GMP transfer to RNA. Mol.Cell Biol. 1995;15:6222–6231. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pena M, Kyrieleis OJ, Cusack S. Structural insights into the mechanism and evolution of the vaccinia virus mRNA cap N7 methyl-transferase. EMBO J. 2007;26:4913–4925. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Hagler J, Shuman S. Factor-dependent release of nascent RNA by ternary complexes of vaccinia RNA polymerase. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:19556–19562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Shuman S. An ATPase component of the transcription elongation complex is required for factor-dependent transcription termination by vaccinia RNA polymerase. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:29386–29392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Shuman S. Vaccinia NPH-I, a DExH-box ATPase, is the energy coupling factor for mRNA transcription termination. Genes Dev. 1998;12:538–546. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershowitz A, Moss B. Abortive transcription products of vaccinia virus are guanylylated, methylated, and polyadenylylated. J.Virol. 1979;31:849–853. doi: 10.1128/jvi.31.3.849-853.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C, Shuman S. Mapping the active site of vaccinia virus RNA triphosphatase. Virology. 2003;309:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo PX, Moss B. Interaction and mutual stabilization of the two subunits of vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme coexpressed in Escherichia coli. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1990;87:4023–4027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler J, Luo Y, Shuman S. Factor-dependent transcription termination by vaccinia RNA polymerase. Kinetic coupling and requirement for ATP hydrolysis. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:10050–10060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler J, Shuman S. A freeze-frame view of eukaryotic transcription during elongation and capping of nascent mRNA. Science. 1992;255:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1546295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N, Rosales R, Moss B. Transcription initiation factor activity of vaccinia virus capping enzyme is independent of mRNA guanylylation. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1993;90:2860–2864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higman MA, Christen LA, Niles EG. The mRNA (guanine-7-)methyltransferase domain of the vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme. Expression in Escherichia coli and structural and kinetic comparison to the intact capping enzyme. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:14974–14981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsafanas GC, Moss B. Vaccinia virus intermediate stage transcription is complemented by Ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3 domain-binding protein (G3BP) and cytoplasmic activation/proliferation-associated protein (p137) individually or as a heterodimer. J.Biol.Chem. 2004;279:52210–52217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay NE, Bainbridge TW, Condit RC, Bubb MR, Judd RE, Venkatakrishnan B, McKenna R, D’Costa SM. Biochemical and biophysical properties of a putative hub protein expressed by vaccinia virus. J.Biol.Chem. 2013;288:11470–11481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.442012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrieleis OJ, Chang J, de la Pena M, Shuman S, Cusack S. Crystal structure of vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme provides insights into the mechanism and evolution of the capping apparatus. Structure. 2014;22:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Hagler J, Shuman S. Discrete functional stages of vaccinia virus early transcription during a single round of RNA synthesis in vitro. J.Biol.Chem. 1991;266:13303–13310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Mao X, Deng L, Cong P, Shuman S. The D1 and D12 subunits are both essential for the transcription termination factor activity of vaccinia virus capping enzyme. J.Virol. 1995;69:3852–3856. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3852-3856.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Shuman S. Intrinsic RNA (guanine-7) methyltransferase activity of the vaccinia virus capping enzyme D1 subunit is stimulated by the D12 subunit. Identification of amino acid residues in the D1 protein required for subunit association and methyl group transfer. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:24472–24479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA, Moss B. Modification of RNA by mRNA guanylyltransferase and mRNA (guanine-7-)methyltransferase from vaccinia virions. J.Biol.Chem. 1975;250:9330–9335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA, Moss B. mRNA guanylyltransferase and mRNA (guanine-7-)-methyltransferase from vaccinia virions. Donor and acceptor substrate specificites. J.Biol.Chem. 1976;251:7313–7321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA, Paoletti E, Moss B. Purification of mRNA guanylyltransferase and mRNA (guanine-7-) methyltransferase from vaccinia virions. J.Biol.Chem. 1975;250:9322–9329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MR, Niles EG. Interaction between nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I and the H4L subunit of the viral RNA polymerase is required for vaccinia virus early gene transcript release. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:25798–25804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JR, Cohen LK, Roberts BE. Identification of the DNA sequences encoding the large subunit of the mRNA-capping enzyme of vaccinia virus. J.Virol. 1984;52:206–214. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.206-214.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B. Poxviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Wolters Kluwer-Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 2129–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Moussatche N, Keller SJ. Phosphorylation of vaccinia virus core proteins during transcription in vitro. J.Virol. 1991;65:2555–2561. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2555-2561.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myette JR, Niles EG. Characterization of the vaccinia virus RNA 5′-triphosphatase and nucleotide triphosphate phosphohydrolase activities. Demonstrate that both activities are carried out at the same active site. J.Biol.Chem. 1996a;271:11945–11952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myette JR, Niles EG. Domain structure of the vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme. Expression in Escherichia coli of a subdomain possessing the RNA 5′-triphosphatase and guanylyltransferase activities and a kinetic comparison to the full-size enzyme. J.Biol.Chem. 1996b;271:11936–11944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles EG, Christen L. Identification of the vaccinia virus mRNA guanyltransferase active site lysine. J.Biol.Chem. 1993;268:24986–24989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles EG, Lee-Chen GJ, Shuman S, Moss B, Broyles SS. Vaccinia virus gene D12L encodes the small subunit of the viral mRNA capping enzyme. Virology. 1989;172:513–522. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R, Harris N, Ahn BY, Moss B. Purification and identification of a vaccinia virus-encoded intermediate stage promoter-specific transcription factor that has homology to eukaryotic transcription factor SII (TFIIS) and an additional role as a viral RNA polymerase subunit. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;269:14260–14267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz P, Moss B. Identification of a transcription factor, encoded by two vaccinia virus early genes, that regulates the intermediate stage of viral gene expression. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1999;96:2692–2697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Shuman S. Genetic analysis of poxvirus mRNA cap methyltransferase: suppression of conditional mutations in the stimulatory D12 subunit by second-site mutations in the catalytic D1 subunit. Virology. 2006;352:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatzer AN, Kato SE, Condit RC. Phenotypic analysis of a temperature sensitive mutant in the large subunit of the vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme. Virology. 2008;375:236–252. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman S, Broyles SS, Moss B. Purification and characterization of a transcription termination factor from vaccinia virions. J.Biol.Chem. 1987;262:12372–12380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman S, Hurwitz J. Mechanism of mRNA capping by vaccinia virus guanylyltransferase: characterization of an enzyme--guanylate intermediate. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1981;78:187–191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman S, Moss B. Purification and use of vaccinia virus messenger RNA capping enzyme. Methods Enzymol. 1990;181:170–180. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)81119-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman S, Surks M, Furneaux H, Hurwitz J. Purification and characterization of a GTP-pyrophosphate exchange activity from vaccinia virions. Association of the GTP-pyrophosphate exchange activity with vaccinia mRNA guanylyltransferase. RNA (guanine- 7-)methyltransferase complex (capping enzyme) J.Biol.Chem. 1980;255:11588–11598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate J, Gollnick P. Role of forward translocation in nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I (NPH I)-mediated transcription termination of vaccinia virus early genes. J.Biol.Chem. 2011;286:44764–44775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos JC, Sasker M, Stunnenberg HG. Promoter melting by a stage-specific vaccinia virus transcription factor is independent of the presence of RNA polymerase. Cell. 1991a;65:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90412-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos JC, Sasker M, Stunnenberg HG. Vaccinia virus capping enzyme is a transcription initiation factor. EMBO J. 1991b;10:2553–2558. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Moss B. Interaction of the vaccinia virus RNA polymerase-associated 94-kilodalton protein with the early transcription factor. J.Virol. 2009;83:12018–12026. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01653-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Shuman S. Mutational analysis of the RNA triphosphatase component of vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme. J.Virol. 1996;70:6162–6168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6162-6168.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen L, Moss B. Oligonucleotide sequence signaling transcriptional termination of vaccinia virus early genes. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1987;84:6417–6421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]