Abstract

Increased activity of the endocannabinoid system has emerged as a pathogenic factor in visceral obesity, which is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The endocannabinoid system is composed of at least two G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1), and the cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2). Downregulation of CB1 activity in rodents and humans has proven efficacious to reduce food intake, abdominal adiposity, fasting glucose levels, and cardiometabolic risk factors. Unfortunately, downregulation of CB1 activity by universally active CB1 inverse agonists has been found to elicit psychiatric side effects, which led to the termination of using globally active CB1 inverse agonists to treat diet-induced obesity. Interestingly, preclinical studies have shown that downregulation of CB1 activity by CB1 neutral antagonists or peripherally restricted CB1 inverse agonists provided similar anorectic effects and metabolic benefits without psychiatric side effects seen in globally active CB1 inverse agonists. Furthermore, downregulation of CB1 activity may ease endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial stress which are contributors to obesity-induced insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. This suggests new approaches for cannabinoid-based therapy in the management of obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: CB1, Obesity, Type two diabetes mellitus, Inverse agonist, Endocannabinoid

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a metabolic disease with key pathological features of impaired insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells and insulin resistance in glucose consumption and storage sites such as adipose, liver, and skeletal muscle (Ashcroft and Rorsman 2012). This metabolic disorder affects about 380 million people worldwide (Guariguata et al. 2014). Studies have linked T2DM with obesity (Bastard et al. 2006; Eckel et al. 2011), while other factors such as genetic mutations (Herder and Roden 2011), overexpression of the hormone amylin (Zhang et al. 2014), and a disturbance of the body’s natural clock (Buxton et al. 2012; Shi et al. 2013) have also been recognized as contributors to the development of T2DM. Growing evidence indicates that excessive body fat, particularly abdominal fat, can cause chronic subclinical inflammation (Donath 2014; Hameed et al. 2015; Li et al. 2015; Spranger et al. 2003; Van Greevenbroek et al. 2013). Excessive abdominal fat induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and hypertrophy in adipocytes, both of which have been associated with the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Hotamisligil 2010). ER stress can also trigger an adaptive compensatory unfolded protein response (UPR) (Cnop et al. 2012; Leem and Koh 2011), which in turn leads to inflammatory processes (Hotamisligil 2008). This inflammation interferes with insulin receptor signaling through the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and subsequent serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) (Hotamisligil 2008) and via induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activation of the nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB) (Hotamisligil 2010; Zhang and Kaufman 2008). It has been demonstrated that reversal of ER stress either by genetic overexpression of ER chaperones (Kammoun et al. 2009; Ozawa et al. 2005) or administration of chemical chaperones (Özcan et al. 2006) enhanced insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, muscle, and liver of experimental animals (Fig. 1).

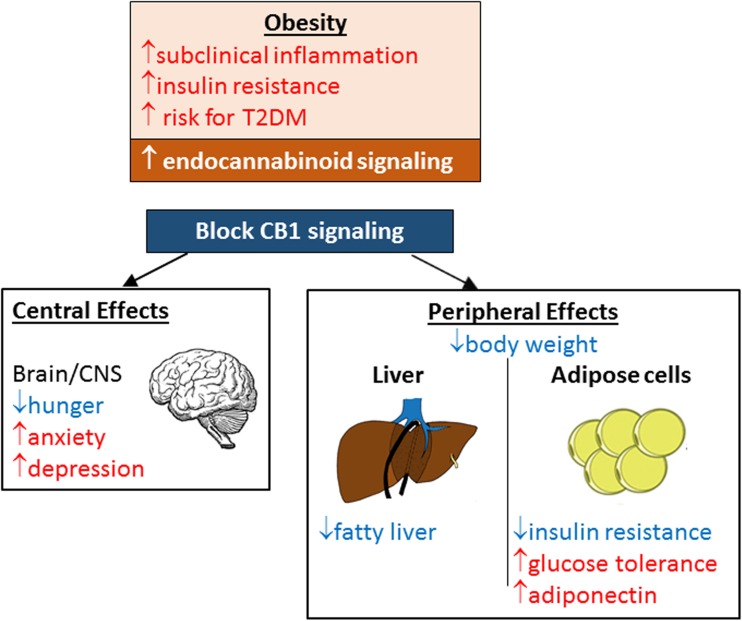

Fig. 1.

The impact of blocking CB1 signaling on obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Blocking CB1 signaling globally causes weight loss and decreases insulin resistance but also causes anxiogenic effects. However, blocking CB1 signaling peripherally maintains the benefits of blocking CB1 in liver and adipose cells while avoiding these anxiogenic effects

The interplay of mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress has been well documented (Leem and Koh 2011; Rieusset 2011). Imbalanced nutrient supply, energy expenditure, and oxidative respiration leads to the dysfunction of mitochondria, which contributes to the development of insulin resistance and T2DM (Goossens 2008; Lim et al. 2009; Rieusset 2011). Furthermore, obesity can lead to the expansion, hyperplasia, and hypertrophy of adipocytes, which pathologically involve ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative and other cellular stress (Tripathi and Pandey 2012). Collectively, obesity-induced stress alters the secretion properties of adipocytes and leads to elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and other biomarkers of inflammation (Apovian et al. 2008; Dahlén et al. 2014; Fontana et al. 2007; Hotamisligil et al. 1995; Hotamisligil et al. 1993). These pro-inflammatory cytokines impair insulin signaling (Howard and Flier 2006; Lebrun and Van Obberghen 2008) and recruit pro-inflammatory immune cells such as macrophages to adipose tissue (Cinti et al. 2005). The infiltrated macrophages also produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can worsen the inflammation in adipose tissues and lead to the pathogenesis of insulin resistance (Dahlén et al. 2014; Fontana et al. 2007; Van Greevenbroek et al. 2013).

The importance of weight control has been well-established in the management of type 2 diabetes (Klein et al. 2004). Evidence from preclinical and clinical observations suggests that the endocannabinoid (EC) system is overactive in the presence of abdominal obesity and/or diabetes (Scheen 2007). Hence, attenuation of the EC system overactivity has been proposed as a new approach for the treatment of obesity and its related disorders.

The overactive endocannabinoid system in obesity

The EC system is composed of two G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1), cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2), a group of lipid-derived endogenous ligands called endocannabinoids, and several metabolic enzymes that are involved in the synthesis and degradation of endocannabinoids. The endocannabinoids include arachidonoylethanolamide (AEA, anandamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (Pertwee et al. 2010). The major physiological role of endocannabinoids is to modulate the release of neurotransmitters including excitatory amino acids (glutamate), inhibitory amino acids (GABA, glycine), and monoamines (dopamine, serotonin, noradrenaline, acetylcholine) (Di Marzo et al. 2004; Pertwee et al. 2010). The CB1 receptor possesses constitutive (also known as basal) activity in the absence of any ligand (Pertwee et al. 2010). A CB1 agonist augments the activity of the receptor above its basal level, whereas a CB1 inverse agonist decreases the activity below the basal level. A neutral CB1 antagonist has no activity, but occupies the endogenous ligand binding site to block its activity. The term “blockers” is used here to refer to antagonists or inverse agonists.

The EC system was initially known as a neuromodulatory system and has emerged as an important intercellular signaling system that regulates energy balance (Pagotto et al. 2006) and other physiological functions (Pacher et al. 2006). In general, activation of the EC system depends upon external stimuli such as cellular stress, tissue damage, or metabolic challenges (Di Marzo et al. 2004; Piomelli 2003). Experimental evidence indicates that the endocannabinoid system is chronically activated in obese states (Blüher et al. 2006; Di Marzo 2008; Engeli 2008; Engeli et al. 2005). Overactivity of the EC system may result from increased synthesis of endocannabinoids, overexpression of the cannabinoid receptors, or decreased degradation of endocannabinoids. In human obese subjects, various genetic variations of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) have been identified (Sipe et al. 2010). Genetic alteration of FAAH can lead to elevated circulating levels of AEA and other endocannabinoids (Sipe et al. 2010).

In human subjects, circulating 2-AG was correlated with body fat, visceral fat mass, and fasting plasma insulin concentrations (Cote et al. 2007). Additionally, circulating AEA and 2-AG were higher in obese menopausal women compared to lean menopausal women (Engeli et al. 2005). Increased availability of endocannabinoids may lead to an enhanced activation of cannabinoid receptors in both central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral organs (De Kloet and Woods 2009). Numerous experimental data indicate that activation of the CB1 receptor by endocannabinoids promotes food intake (Di Marzo et al. 2001), increases lipogenesis in adipose tissue and liver (Cota et al. 2003; Jourdan et al. 2012; Osei-Hyiaman et al. 2005), and induces insulin resistance and dyslipidemia (Eckardt et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2012).

Clinical evidence suggests that accumulation of abdominal fat is a critical correlate of the overactive peripheral endocannabinoid system in human obesity (Blüher et al. 2006; Cote et al. 2007). Therefore, downregulation of the overactive endocannabinoid system, particularly CB1 receptor activity, represents an attractive approach for the treatment of obesity-derived metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes.

Downregulation of the endocannabinoid system by CB1 receptor blockers

It has been demonstrated that downregulation of CB1 receptor activity by various CB1 inverse agonists can reduce body weight, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and fatty liver in obese experimental animals (Jourdan et al. 2010; Simiand et al. 1998; Trillou et al. 2003). Similar “proof-of-concept” results have been obtained from preclinical studies of CB1 receptor inverse agonists (Black 2004; Lange and Kruse 2004; Smith and Fathi 2005). In preclinical settings, activation of the CB1 receptor elicits metabolic stress conditions linked to insulin resistance and T2DM. Examples include the induction of ER stress in human and mice hepatocytes (Liu et al. 2012), impaired mitochondrial biogenesis in mice white adipose, muscle, and liver tissues (Tedesco et al. 2010), and altered hepatic mitochondrial function (Lipina et al. 2014) as well as induction of adipose hypertrophy and macrophage infiltration (Wong et al. 2012). On the other hand, downregulation of CB1 receptors by the CB1 inverse agonist rimonabant has been found to improve hepatocyte (Flamment et al. 2009) and adipocyte (Tedesco et al. 2008) mitochondrial functions, to induce transdifferentiation of white adipocytes to brown fat (Perwitz et al. 2010), and to reduce hypertrophy of adipocytes (Jbilo et al. 2005).

The therapeutic value of rimonabant, the first CB1 inverse agonist, has been assessed in multiple clinical trials (i.e., RIO Europe, RIO North America, and RIO Lipids) (Christopoulou and Kiortsis 2011). In overweight/obese non-diabetic patients, rimonabant produced significant weight loss (−4.7 to −5.4 kg) and waist circumference reduction (−3.6 to −4.7 cm). At the same time, there was a decrease in cardiometabolic risk factors (Pi-Sunyer et al. 2006; Van Gaal et al. 2005; Van Gaal et al. 2008). Along with these clinical benefits, increasing plasma adiponectin and decreasing plasma leptin and CRP were also achieved (Després et al. 2005). Adiponectin is a plasma protein exclusively secreted by adipose tissue. It induces free fatty acid oxidation, decreases hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, and leads to body weight reduction (Diez and Iglesias 2003; Yamauchi et al. 2001). Data from the same clinical trials (i.e., the RIO trials) revealed that rimonabant not only can lead to significant reductions in plasma glucose and insulin levels but can also prevent or reverse progression of glucose intolerance in overweight/obese non-diabetic patients (Scheen 2007). Clinical assessment of rimonabant in drug-naive type 2 diabetic patients has shown that the drug at a 20-mg dosage reduced HbA1C (glycated hemoglobin) and fasting plasma glucose levels, while body weight, waist circumference, and cardiometabolic risk factors were decreased (Iranmanesh et al. 2006; Rosenstock et al. 2008). Furthermore, rimonabant was investigated in overweight/obese type 2 diabetic patients who were insulin-treated or on metformin or sulphonylurea monotherapy. In this trial, reduction of body weight and HbA1c were achieved, while lipid profiles were improved (Hollander et al. 2010; Scheen et al. 2006). The clinical efficacy of rimonabant and several follow-up CB1 inverse agonists (Janero and Makriyannis 2009) in the management of body weight indicated an exciting path for the translation of CB1 receptor blockers into antiobesity and antidiabetic medications. However, soon after the regulatory approval of rimonabant in Europe, the drug was found with psychiatric side effects such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Christensen et al. 2007; Moreira and Crippa 2009). These untoward psychiatric side effects of rimonabant caused all CB1 inverse agonists to be abandoned from further clinical development (Janero and Makriyannis 2009). However, the clinically tested CB1 inverse agonists all are CB1 blockers that can target CB1 receptors located in both central circuits and in peripheral organs (Janero and Makriyannis 2009). Given that the modulation of food intake and feeding behavior by the EC system was initially attributed to both central (Cota et al. 2003; Di Marzo and Matias 2005) and peripheral (Cota et al. 2003; Gómez et al. 2002) mechanisms, the metabolic benefits from rimonabant or other clinically tested CB1 inverse agonists cannot be exclusively ascribed to the CB1 receptors present in central circuits. The involvement of the downregulation of CB1 receptors present in the liver, muscle, adipocytes, and endocrine pancreatic cells cannot be excluded (Quarta et al. 2011). In this context, peripherally active CB1 blockers with limited brain penetration may be promising for the management of obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders without the depressive side effects (Kunos and Tam 2011).

Investigations of the therapeutic benefits from downregulation of peripheral CB1 receptors have started recently. A number of peripherally restricted CB1 antagonists such as AM6545 (Cluny et al. 2010; Tam et al. 2010) and inverse agonists such as JD5037 (Chorvat et al. 2012; Tam et al. 2012) and others (Chorvat 2013; Dow et al. 2012; Hortala et al. 2010; Silvestri and Di Marzo 2012; Son et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2011) have provided proof of concept in preclinical studies. For instance, in mice with genetic and diet-induced-obesity (DIO), AM6545 at the dose of 10 mg/kg/day led to a 12 % weight reduction as compared to rimonabant, which caused a 21 % reduction at the same dose. Interestingly, AM6545 does not show an anxiogenic effect, which is prophetic for the neuropsychiatric side effects of centrally active CB1 inverse agonists like rimonabant (Tam et al. 2010). As a glycemic control, AM6545 is almost as efficacious as rimonabant in improving glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, reversing fatty liver, and improving the plasma lipid profile of the experimental animals. These effects were attributed to the blockade of CB1 receptors in peripheral tissues, as proven by the use of hepatic CB1-deficient mice (Tam et al. 2010). Similarly, the peripherally restricted CB1 inverse agonist JD5037 was demonstrated to elicit effects of reducing food intake, body weight, and adiposity without anxiogenic effects in mice models (Chorvat et al. 2012; Tam et al. 2012). Collectively, these preclinical results indicate that blockade of peripheral CB1 receptors may be sufficient to produce antiobesity effects without CNS liabilities. In addition to the effects of reducing food intake and body weight, downregulation of CB1 receptor activity by CB1 inverse agonists has been found to suppress insulin hypersecretion under conditions of metabolic dysfunction (Getty‐Kaushik et al. 2009; Lynch et al. 2012; Rohrbach et al. 2012) and to promote the proliferation and survival of β-cells in pancreases of obese animal models (Doyle et al. 2011; Duvivier et al. 2009; Janiak et al. 2007; Jourdan et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2012). These effects probably resulted from the reduction of lipotoxicity, which has been implied to cause β-cell death in rodents and humans (Unger and Orci 2001).

Besides peripherally active CB1 inverse agonists, a novel class of CB1 ligands has been discovered in the last few years. This class of compounds can allosterically modulate the activity of the CB1 receptor through a site topographically distinct from the endogenous ligand binding site (Ross et al. 2012). One of these CB1 allosteric modulators, PSNCBAM-1, was characterized as an allosteric CB1 antagonist (Horswill et al. 2007). It interacts with the CB1 receptor at a receptor site that is different from the active site where traditional CB1 inverse agonists bind. The compound was demonstrated to induce acute hypophagia and weight loss in male Sprague–Dawley rats (Horswill et al. 2007). Whether the hypophagic effects from allosteric CB1 antagonists can be achieved in obese models and translated into therapeutic implications for obesity and T2DM remains to be investigated.

Conclusions

Obesity-provoked subclinical inflammation is pathogenic for insulin resistance, which is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes. Overactivation of the endocannabinoid system has been found to underpin factors of obesity. The antiobesity efficacy and metabolic benefits from blocking the CB1 receptor have been confirmed by numerous preclinical studies and multiple clinical trials of rimonabant and other CB1 inverse agonists. However, the psychiatric side effects of globally active CB1 inverse agonists like rimonabant prevent clinical applications of this class of compounds. Alternative approaches to downregulate the endocannabinoid system by selectively blocking the CB1 receptor in the peripheral tissues have been demonstrated in preclinical studies as a viable strategy to avoid CNS side effects while maintaining therapeutic benefits. New approaches to downregulate CB1 activity through allosteric modulation are also emerging. Collectively, controlled downregulation of CB1 activity could provide a promising strategy to treat obesity and obesity-related disorders such as type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kwang Hyun Ahn for his assistance with the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Grant DA020763 (to D.A.K.) and a Faculty Development Fund from Texas A&M Health Sciences Center (to D.L.).

Abbreviations

- 2-AG

2-Arachidonoylglycerol

- AEA

Arachidonoylethanolamide

- CB1

Cannabinoid receptor type 1

- CB2

Cannabinoid receptor type 2

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CNS

Central nervous system

- EC

Endocannabinoid

- FAAH

Fatty acid amide hydrolase

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin

- MAGL

Monoacylglycerol lipase

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

References

- Apovian CM, et al. Adipose macrophage infiltration is associated with insulin resistance and vascular endothelial dysfunction in obese subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1654–1659. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.170316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Diabetes mellitus and the β cell: the last ten years. Cell. 2012;148:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastard J-P, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S (2004) Cannabinoid receptor antagonists and obesity Current opinion in investigational drugs (London, England: 2000) 5:389-394 [PubMed]

- Blüher M, et al. Dysregulation of the peripheral and adipose tissue endocannabinoid system in human abdominal obesity. Diabetes. 2006;55:3053–3060. doi: 10.2337/db06-0812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton OM, et al. Adverse metabolic consequences in humans of prolonged sleep restriction combined with circadian disruption. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:129ra143. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorvat RJ. Peripherally restricted CB1 receptor blockers. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:4751–4760. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorvat RJ, Berbaum J, Seriacki K, McElroy JF. JD-5006 and JD-5037: peripherally restricted (PR) cannabinoid-1 receptor blockers related to SLV-319 (Ibipinabant) as metabolic disorder therapeutics devoid of CNS liabilities. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:6173–6180. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A. Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;370:1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulou F, Kiortsis D. An overview of the metabolic effects of rimonabant in randomized controlled trials: potential for other cannabinoid 1 receptor blockers in obesity. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti S, et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluny N, et al. A novel peripherally restricted cannabinoid receptor antagonist, AM6545, reduces food intake and body weight, but does not cause malaise, in rodents. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161:629–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnop M, Foufelle F, Velloso LA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, obesity and diabetes. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Investig. 2003;112:423. doi: 10.1172/JCI17725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote M, Matias I, Lemieux I, Petrosino S, Almeras N, Despres J, Di Marzo V. Circulating endocannabinoid levels, abdominal adiposity and related cardiometabolic risk factors in obese men. Int J Obes. 2007;31:692–699. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlén EM, Tengblad A, Länne T, Clinchy B, Ernerudh J, Nystrom F, Östgren C. Abdominal obesity and low-grade systemic inflammation as markers of subclinical organ damage in type 2 diabetes. Diabete Metab. 2014;40:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet AD, Woods SC. Endocannabinoids and their receptors as targets for obesity therapy. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2531–2536. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Després J-P, Golay A, Sjöström L. Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2121–2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V. The endocannabinoid system in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1356–1367. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Matias I. Endocannabinoid control of food intake and energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:585–589. doi: 10.1038/nn1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, et al. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature. 2001;410:822–825. doi: 10.1038/35071088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Bifulco M, De Petrocellis L. The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:771–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez JJ, Iglesias P. The role of the novel adipocyte-derived hormone adiponectin in human disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;148:293–300. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1480293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath MY. Targeting inflammation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: time to start. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrd4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow RL, et al. Design of a potent CB1 receptor antagonist series: potential scaffold for peripherally-targeted agents. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:397–401. doi: 10.1021/ml3000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle ME et al. (2011) Cannabinoids Inhibit Insulin Receptor Signaling in Pancreatic\(\ beta\)-Cells [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Duvivier VF, et al. Beneficial effect of a chronic treatment with rimonabant on pancreatic function and β-cell morphology in Zucker Fatty rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;616:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt K, et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptors in human skeletal muscle cells participate in the negative crosstalk between fat and muscle. Diabetologia. 2009;52:664–674. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel RH, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes: what can be unified and what needs to be individualized? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1654–1663. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeli S. Dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system in obesity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:110–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeli S, et al. Activation of the peripheral endocannabinoid system in human obesity. Diabetes. 2005;54:2838–2843. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamment M, Gueguen N, Wetterwald C, Simard G, Malthièry Y, Ducluzeau P-H. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 antagonist rimonabant on hepatic mitochondrial function in rats fed a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E1162–E1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00169.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Eagon JC, Trujillo ME, Scherer PE, Klein S. Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans. Diabetes. 2007;56:1010–1013. doi: 10.2337/db06-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getty‐Kaushik L, Richard AMT, Deeney JT, Krawczyk S, Shirihai O, Corkey BE. The CB1 antagonist rimonabant decreases insulin hypersecretion in rat pancreatic islets. Obesity. 2009;17:1856–1860. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez R, et al. A peripheral mechanism for CB1 cannabinoid receptor-dependent modulation of feeding. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9612–9617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09612.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens GH. The role of adipose tissue dysfunction in the pathogenesis of obesity-related insulin resistance. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guariguata L, Whiting D, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw J. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2014;103:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed I, Masoodi SR, Mir SA, Nabi M, Ghazanfar K, Ganai BA. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: from a metabolic disorder to an inflammatory condition. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:598. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herder C, Roden M. Genetics of type 2 diabetes: pathophysiologic and clinical relevance. Eur J Clin Investig. 2011;41:679–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander PA, Amod A, Litwak LE, Chaudhari U. Effect of rimonabant on glycemic control in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: the ARPEGGIO trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:605–607. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horswill J, et al. PSNCBAM‐1, a novel allosteric antagonist at cannabinoid CB1 receptors with hypophagic effects in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:805–814. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortala L, et al. Rational design of a novel peripherally-restricted, orally active CB 1 cannabinoid antagonist containing a 2,3-diarylpyrrole motif. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:4573–4577. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil G. Inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity and diabetes. Int J Obes. 2008;32:S52–S54. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 2010;140:900–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:2409. doi: 10.1172/JCI117936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JK, Flier JS. Attenuation of leptin and insulin signaling by SOCS proteins. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh A, Rosenstock J, Hollander P. SERENADE: rimonabant monotherapy for treatment of multiple cardiometabolic risk factors in treatment-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:230. [Google Scholar]

- Janero DR, Makriyannis A (2009) Cannabinoid receptor antagonists: pharmacological opportunities, clinical experience, and translational prognosis [DOI] [PubMed]

- Janiak P, et al. Blockade of cannabinoid CB1 receptors improves renal function, metabolic profile, and increased survival of obese Zucker rats. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1345–1357. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jbilo O, et al. The CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant reverses the diet-induced obesity phenotype through the regulation of lipolysis and energy balance. FASEB J. 2005;19:1567–1569. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3177fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan T, Djaouti L, Demizieux L, Gresti J, Vergès B, Degrace P. CB1 antagonism exerts specific molecular effects on visceral and subcutaneous fat and reverses liver steatosis in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2010;59:926–934. doi: 10.2337/db09-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan T, Demizieux L, Gresti J, Djaouti L, Gaba L, Vergès B, Degrace P. Antagonism of peripheral hepatic cannabinoid receptor‐1 improves liver lipid metabolism in mice: evidence from cultured explants. Hepatology. 2012;55:790–799. doi: 10.1002/hep.24733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan T, et al. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in infiltrating macrophages by endocannabinoids mediates beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. 2013;19:1132–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun HL, et al. GRP78 expression inhibits insulin and ER stress–induced SREBP-1c activation and reduces hepatic steatosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1201. doi: 10.1172/JCI37007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W et al (2012) Cannabinoids induce pancreatic β-cell death by directly inhibiting insulin receptor activation Science signaling 5:ra23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klein S, Sheard N, Pi-Sunyer X, Daly A, Wylie-Rosett J, Kulkarni K, Clark NG. Weight management through lifestyle modification for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: rational and strategies: a statement of the American Diabetes Association, the North American Association for the Study of Obesity, and the American Society for Clinical Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:257–263. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunos G, Tam J. The case for peripheral CB1 receptor blockade in the treatment of visceral obesity and its cardiometabolic complications. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1423–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange J, Kruse C. Recent advances in CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonists. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev. 2004;7:498–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun P, Van Obberghen E. SOCS proteins causing trouble in insulin action. Acta Physiol. 2008;192:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem J, Koh EH (2011) Interaction between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum: implications for the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus Experimental diabetes research 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li P et. al (2015) LTB4 promotes insulin resistance in obese mice by acting on macrophages, hepatocytes and myocytes Nature medicine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lim JH, Lee HJ, Jung MH, Song J. Coupling mitochondrial dysfunction to endoplasmic reticulum stress response: a molecular mechanism leading to hepatic insulin resistance. Cell Signal. 2009;21:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipina C, Irving AJ, Hundal HS. Mitochondria: a possible nexus for the regulation of energy homeostasis by the endocannabinoid system? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307:E1–E13. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00100.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, et al. Hepatic cannabinoid receptor-1 mediates diet-induced insulin resistance via inhibition of insulin signaling and clearance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1218–1228. e1211. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch CJ, et al. Some cannabinoid receptor ligands and their distomers are direct-acting openers of SUR1 KATP channels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E540–E551. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00250.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FA, Crippa JAS. The psychiatric side-effects of rimonabant. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31:145–153. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462009000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Hyiaman D, et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J Clin Investig. 2005;115:1298. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum chaperone improves insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:657–663. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özcan U, et al. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1128294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:389–462. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagotto U, Marsicano G, Cota D, Lutz B, Pasquali R. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:73–100. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee R, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:588–631. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perwitz N, et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor blockade induces transdifferentiation towards a brown fat phenotype in white adipocytes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873–884. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, Devin J, Rosenstock J, Group R-NAS Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:761–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta C, Mazza R, Obici S, Pasquali R, Pagotto U. Energy balance regulation by endocannabinoids at central and peripheral levels. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieusset J. Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum: mitochondria–endoplasmic reticulum interplay in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach K, et al. Ibipinabant attenuates β‐cell loss in male Zucker diabetic fatty rats independently of its effects on body weight. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:555–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Chevalier S, Iranmanesh A. SERENADE: The Study Evaluating Rimonabant Efficacy in Drug-Naive Diabetic Patients Effects of monotherapy with rimonabant, the first selective CB1 receptor antagonist, on glycemic control, body weight, and lipid profile in drug-naive type 2 diabetes*. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2169–2176. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RA, Baillie GL, Pertwee RG. Allosteric modulation of cannabinoid CB1 receptor. FASEB J. 2012;26:836. [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ. Cannabinoid-1 receptor antagonists in type-2 diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21:535–553. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ, Finer N, Hollander P, Jensen MD, Van Gaal LF, Group R-DS Efficacy and tolerability of rimonabant in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2006;368:1660–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S-q, Ansari TS, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH, Johnson CH. Circadian disruption leads to insulin resistance and obesity. Curr Biol. 2013;23:372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri C, Di Marzo V. Second generation CB1 receptor blockers and other inhibitors of peripheral endocannabinoid overactivity and the rationale of their use against metabolic disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1309–1322. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.704019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simiand J, Keane M, Keane P, Soubrie P. SR 141716, a CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist, selectively reduces sweet food intake in marmoset. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipe JC, Scott TM, Murray S, Harismendy O, Simon GM, Cravatt BF, Waalen J. Biomarkers of endocannabinoid system activation in severe obesity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Fathi Z. Recent advances in the research and development of CB1 antagonists. IDrugs Investig Drugs J. 2005;8:53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son M, et al. Peripherally acting CB1-receptor antagonist: the relative importance of central and peripheral CB1 receptors in adiposity control. Int J Obes. 2010;34:547–556. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spranger J, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes. 2003;52:812–817. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J, et al. Peripheral CB1 cannabinoid receptor blockade improves cardiometabolic risk in mouse models of obesity. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2953. doi: 10.1172/JCI42551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J, et al. Peripheral cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonism reduces obesity by reversing leptin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;16:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco L, et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor blockade promotes mitochondrial biogenesis through endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in white adipocytes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2028–2036. doi: 10.2337/db07-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco L, et al. Cannabinoid receptor stimulation impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse white adipose tissue, muscle, and liver: the role of eNOS, p38 MAPK, and AMPK pathways. Diabetes. 2010;59:2826–2836. doi: 10.2337/db09-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trillou CR, Arnone M, Delgorge C, Gonalons N, Keane P, Maffrand J-P, Soubrié P. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00545.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi YB, Pandey V (2012) Obesity and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stresses Frontiers in immunology 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Unger RH, Orci L. Diseases of liporegulation: new perspective on obesity and related disorders. FASEB J. 2001;15:312–321. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal LF, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rössner S, Group R-ES Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet. 2005;365:1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaal LF, Scheen AJ, Rissanen AM, Rössner S, Hanotin C, Ziegler O. Long-term effect of CB1 blockade with rimonabant on cardiometabolic risk factors: two year results from the RIO-Europe Study†. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1761–1771. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Greevenbroek M, Schalkwijk C, Stehouwer C. Obesity-associated low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: causes and consequences. Neth J Med. 2013;71:174–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A, et al. The major plant-derived cannabinoid Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol promotes hypertrophy and macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44:105. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y-K, Yeh C-F, Ly TW, Hung M-S. A new perspective of cannabinoid 1 receptor antagonists: approaches toward peripheral CB1R blockers without crossing the blood-brain barrier. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:1421–1429. doi: 10.2174/156802611795860997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. 2008;454:455–462. doi: 10.1038/nature07203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, et al. The pathogenic mechanism of diabetes varies with the degree of overexpression and oligomerization of human amylin in the pancreatic islet β cells. FASEB J. 2014;28:5083–5096. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-251744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]