Abstract

Objective

The Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 (PATENT-1) was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial evaluating riociguat in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). PATENT-2 was an open-label long-term extension to PATENT-1. Here, we explore the efficacy and safety of riociguat in the subgroup of patients with persistent/recurrent PAH after correction of congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD) from the PATENT studies.

Methods

In PATENT-1, patients received riociguat (maximum 2.5 or 1.5 mg three times daily) or placebo for 12 weeks; efficacy assessments included change from baseline to study end in 6-min walking distance (6MWD; primary), pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), N-terminal of the prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), WHO functional class (WHO FC) and time to clinical worsening. In PATENT-2, eligible patients from PATENT-1 received long-term riociguat (maximum 2.5 mg three times daily); the primary assessment was safety and tolerability. All PAH-CHD patients had a corrected cardiac defect.

Results

In PATENT-1, riociguat increased mean±SD 6MWD from baseline to week 12 by 39±60 m in patients with PAH-CHD versus 0±42 m for placebo. Riociguat also improved several secondary variables versus placebo, including PVR (−250±410 vs −66±632 dyn·s/cm5), NT-proBNP (−164±317 vs −46±697 pg/mL) and WHO FC (21%/79%/0% vs 8%/83%/8% improved/stabilised/worsened). One patient experienced clinical worsening (riociguat 1.5 mg group). Riociguat was well tolerated. In PATENT-2, riociguat showed sustained efficacy and tolerability in patients with PAH-CHD at 2 years.

Conclusions

Riociguat was well tolerated in patients with PAH-CHD and improved clinical outcomes including 6MWD, PVR, WHO FC and NT-proBNP.

Trial registration number

The clinical trials numbers are NCT00810693 for PATENT-1 and NCT00863681 for PATENT-2.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a life-threatening condition characterised by increased pulmonary artery pressure and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) that leads to cardiac remodelling and right heart failure.1 2 PAH is a common complication in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD)3–5 and PAH associated with CHD (PAH-CHD) is currently the second most common associated form of PAH in adults, after PAH associated with connective tissue disease.1 4 It has been estimated that 4%–28% of patients with CHD will go on to develop PAH, although this varies with the type, size and location of the cardiac defect.3–5 Development of PAH in patients with CHD may be due to an incomplete or delayed repair of the cardiac defect or late diagnosis of CHD; however, PAH may persist or may develop over time in patients who have had a full repair. A recent update to the clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension identifies four subtypes of PAH-CHD: Eisenmenger syndrome, left-to-right shunts, PAH with coincidental CHD and persistent/recurrent PAH after correction of CHD.6

Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CHD have led to an increase in the number of patients with CHD surviving into adulthood.3 4 Consequently, an increasing number of patients with CHD are adults, as demonstrated by data from the Quebec CHD database which showed that, by 2010, adults accounted for 66% of patients with CHD.7

Management of adult patients with PAH-CHD presents a challenge owing to the heterogeneous nature of PAH-CHD and the increased likelihood of comorbidities in older patients. In addition, in contrast to idiopathic PAH, there are very few data from randomised controlled trials demonstrating the efficacy and tolerability of targeted therapies in patients with PAH-CHD. Current medical treatment options for patients with PAH-CHD include PAH-targeted therapies such as phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs), prostanoids and soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulators.1 4 However, although some data are available on the use of PAH-targeted therapies in patients with PAH-CHD, guidelines on pharmacological therapy for PAH-CHD are still largely based on expert opinion rather than clinical trial results. The ERA bosentan has been studied in a randomised controlled trial in patients with PAH-CHD (the Bosentan Randomized trial of Endothelin Antagonist THErapy (BREATHE)-5 trial);8 however, this study focused on patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. To date, there are no published randomised controlled studies that have prospectively assessed PAH-targeted therapies in the clinically important subgroup 4 of PAH-CHD: patients with persistent/recurrent PAH after correction of CHD.

Riociguat is a novel sGC stimulator that has been approved in the USA and Europe for the treatment of adult patients with PAH.9 10 Riociguat has a dual mode of action, sensitising sGC to endogenous nitric oxide (NO) by stabilising NO–sGC binding, and also directly stimulating sGC via a different binding site, independently of NO.11 12 This restores the NO–sGC–cGMP pathway, leading to increased cGMP and vasodilation through the relaxation of smooth muscle cells. Approval of riociguat for the treatment of PAH was based on a pivotal, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial, Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 (PATENT-1), which demonstrated that riociguat was well tolerated and significantly improved 6-min walk distance (6MWD), PVR, N-terminal of the prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels, WHO functional class (WHO FC), time to clinical worsening and Borg dyspnoea score.13 Furthermore, recent findings from PATENT-2, an open-label extension study to PATENT-1, showed that long-term riociguat was well tolerated in patients with PAH and demonstrated sustained improvements in exercise capacity and functional capacity at 2 years.14 15 Here, we have conducted an exploratory post hoc analysis of the efficacy and safety of riociguat in the subgroup of patients with persistent/recurrent PAH following complete repair of CHD in PATENT-1 and PATENT-2, as the prognosis for these patients is particularly poor and presents a significant challenge to treatment.16

Methods

Patients, study design and outcome measures

Full details of the PATENT-1 and PATENT-2 study methodologies have been reported previously13 14 and a summary of patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, study design and outcome measures is provided in the online supplementary appendix. All patients gave their written informed consent. All patients with PAH-CHD had received complete corrective surgery for their cardiac defects and had no residual shunts.

Statistical analysis

Data from this subgroup analysis are exploratory as PATENT-1 was not designed to show statistically significant differences in subgroup populations. The primary efficacy analysis was performed on data from the modified intent-to-treat population (all patients who were randomised and received one or more doses of study drug). The data presented here are observed values and are analysed descriptively; observed values were used due to the small sample size and the retrospective, exploratory nature of the analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the PAH-CHD patient population

Overall, there were 35 patients with persistent/recurrent PAH following complete repair of CHD in PATENT-1 (n=12, 15 and 8 in the placebo, riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum and riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum groups, respectively). Table 1 shows the characteristics of this subgroup at PATENT-1 baseline. Characteristics were generally well balanced between the treatment groups, although there was some variation in parameters such as 6MWD, WHO FC, NT-proBNP and haemodynamics (tables 1–3). The mean±SD age of patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-1 was 38±15 years, mean±SD 6MWD was 371±11 m and all were in WHO FC II (60%) or III (40%; table 1). The patients had severely impaired haemodynamics at baseline, with mean PVR >1000 dyn·s/cm5 and mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) >59 mm Hg across the three treatment arms (table 3). Overall, 57% of patients with PAH-CHD were treatment-naïve while 43% were pretreated with ERAs or prostanoids. Most patients with PAH-CHD had atrial or ventricular septal defects (40% and 34%, respectively); the remaining 23% had persistent ductus arteriosus. All patients had received complete corrective interventional or surgical treatment for the defect, with a mean±SD age at last corrective surgery of 21±12 years. The mean±SD time since the last repair was 17±13 years.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with PAH-CHD in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=12) |

Riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum (n=15) | Riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum (n=8) | Total (n=35) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 10 (83) | 13 (87) | 6 (75) | 29 (83) |

| Age, mean±SD (years) | 40±16 | 35±14 | 41±15 | 38±15 |

| Body mass index, mean±SD (kg/m2) | 24±3 | 21±2 | 24±5 | 23±4 |

| CHD subtype, n (%) | ||||

| Corrected atrial septal defect | 6 (50) | 5 (33) | 3 (38) | 14 (40) |

| Corrected ventricular septal defect | 3 (25) | 7 (47) | 2 (25) | 12 (34) |

| Corrected persistent ductus arteriosus | 3 (25) | 2 (13) | 3 (38) | 8 (23) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| WHO FC II/III, % | 58/42 | 67/33 | 50/50 | 60/40 |

| Time since last corrective surgery, mean±SD (years) | 16±12 | 19±14 | 13±11 | 17±13 |

| In receipt of additional PAH treatment at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| No | 8 (67) | 8 (53) | 4 (50) | 20 (57) |

| Yes | 4 (33) | 7 (47) | 4 (50) | 15 (43) |

| ERA | 3 (25) | 5 (33) | 4 (50) | 12 (34) |

| Prostanoid | 1 (8) | 2 (13) | 0 | 3 (9) |

| 6MWD, mean±SD (m) | 360±59 | 369±78 | 391±59 | 371±11 |

6MWD, 6-min walking distance; CHD, congenital heart disease; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; WHO FC, WHO functional class.

Table 2.

Change from baseline to end of week 12 in primary and secondary variables in the subgroup of patients with PAH-CHD in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 (observed values)

| Placebo | Riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum | Riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline | Change from baseline | n | Baseline | Change from baseline | n | Baseline | Change from baseline | |

| 6MWD (m) | 12 | 360±59 | 0±42 | 15 | 369±78 | +39±60* | 8 | 391±59 | +43±54† |

| PVR (dyn·s/cm5) | 11 | 1312±763 | −66±632 | 13 | 1130±664 | −250±410 | 7 | 1047±564 | −126±368 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 12 | 1573±1775 | −46±697 | 13 | 761±1172 | −164±317† | 7 | 1352±1350 | −872±1147† |

| WHO FC (%) | 12 | II–58% III–42% |

Improved 8% Stabilised 83% Worsened 8% |

15 | II–67% III–33% |

Improved 21% Stabilised 79% Worsened 0%† |

8 | II–50% III–50% |

Improved 29% Stabilised 71% Worsened 0%† |

| Borg dyspnoea score | 12 | 4.3±2.7 | −0.1±2.4 | 15 | 2.5±1.4 | −0.3±1.3* | 8 | 3.2±1.6 | −0.8±0.8† |

| EQ-5D score | 12 | 0.74±0.16 | −0.05±0.22 | 15 | 0.78±0.15 | +0.03±0.18† | 8 | 0.74±0.08 | +0.09±0.14† |

| LPH score | 12 | 40.4±20.0 | −0.1±15.8 | 15 | 34.9±26.0 | −8.0±15.9† | 8 | 40.0±15.3 | −13.7±13.2† |

Data are mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

*Data missing for two patients.

†Data missing for one patient.

6MWD, 6-min walking distance; CHD, congenital heart disease; EQ-5D, EuroQol Group 5-Dimensional Self-report Questionnaire (scores range from −0.6 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating a better quality of life); LPH, Living with Pulmonary Hypertension questionnaire (an adaptation of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; scores range from 0 to 105, with higher scores indicating worse quality of life); NT-proBNP, N-terminal of the prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; WHO FC, WHO functional class.

Table 3.

Change from baseline to end of week 12 in haemodynamic variables in the subgroup of patients with PAH-CHD in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 (observed values)

| Placebo | Riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum | Riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline | Change from baseline | n | Baseline | Change from baseline | n | Baseline | Change from baseline | |

| PVR (dyn·s/cm5) | 11 | 1312±763 | −66±632 | 13 | 1130±664 | −250±410 | 7 | 1047±564 | −126±368 |

| mPAP (mm Hg) | 11 | 61±23 | +1±8 | 14 | 59±21 | −4±7 | 7 | 67±19 | −3±10 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 11 | 2.2±0.6 | +0.2±0.7 | 13 | 2.6±0.6 | +0.4±0.6 | 7 | 3.3±1.4 | +0.3±1.2 |

| Right atrial pressure (mm Hg) | 10 | 8.1±6.0 | +2.7±6.4 | 14 | 8.4±5.3 | −0.3±4.3 | 7 | 9.7±3.1 | −1.7±2.8 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 12 | 90±9 | −3±8 | 14 | 82±13 | −7±9 | 7 | 92±21 | −9±9 |

| Systemic vascular resistance (dyn·s/cm5) | 10 | 1995±394 | −287±587 | 13 | 1516±376 | −307±326 | 7 | 1388±398 | −278±472 |

| Mixed venous oxygen saturation (%) | 11 | 62±10 | −3±7 | 13 | 69±8 | +2±6 | 7 | 68±7 | +1±6 |

Data are mean±SD.

CHD, congenital heart disease; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Efficacy of riociguat in the PAH-CHD patient population

Efficacy in the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group

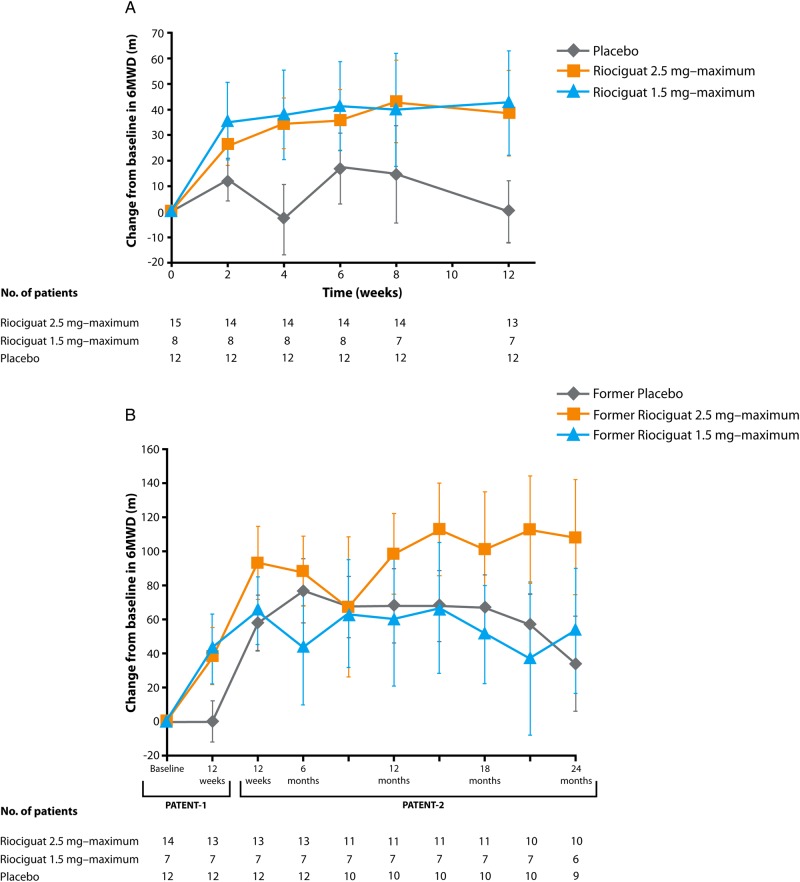

At week 12 in PATENT-1, 6MWD had increased from baseline by a mean±SD of 39±60 m in patients with PAH-CHD in the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group and was unchanged from baseline in the placebo group (figure 1A). In addition, patients with PAH-CHD in the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group showed improvements in a range of secondary variables, including PVR (−250±410 dyn·s/cm5), NT-proBNP (−164±317 pg/mL) and WHO FC (21%/79%/0% improved/stabilised/worsened), compared with patients receiving placebo (table 2). Riociguat up to 2.5 mg also improved additional haemodynamic variables, including mPAP and cardiac index, compared with the placebo group (table 3). Online supplementary figure S1 shows the changes in 6MWD, PVR, NT-proBNP, mPAP, cardiac index and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure in individual patients over the course of PATENT-1.

Figure 1.

Change from baseline in 6-min walking distance (6MWD) in the subgroup of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 (PATENT-1; A) and PATENT-2 (B). Data are observed values (mean±SEM).

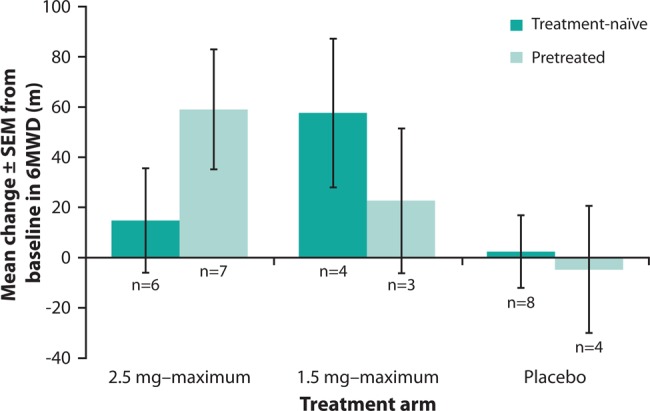

Increases in 6MWD were observed in both patients who were treatment-naïve and patients who were pretreated with PAH-specific therapies (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline in 6-min walking distance (6MWD) in treatment-naïve and pretreated patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1. Data are observed values (mean±SEM).

Efficacy in the riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group

Consistent with the findings in the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group, patients in the riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group showed a similar increase from baseline to week 12 in 6MWD (43±54 m; figure 1A). Improvements were also seen with riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum in a range of secondary variables including PVR, NT-proBNP, WHO FC, Borg dyspnoea score and quality of life scores and additional haemodynamic parameters such as mPAP and cardiac index (tables 2 and 3, see online supplementary figure S1). One patient with PAH-CHD in the riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group experienced clinical worsening (death); no other clinical worsening events were reported.

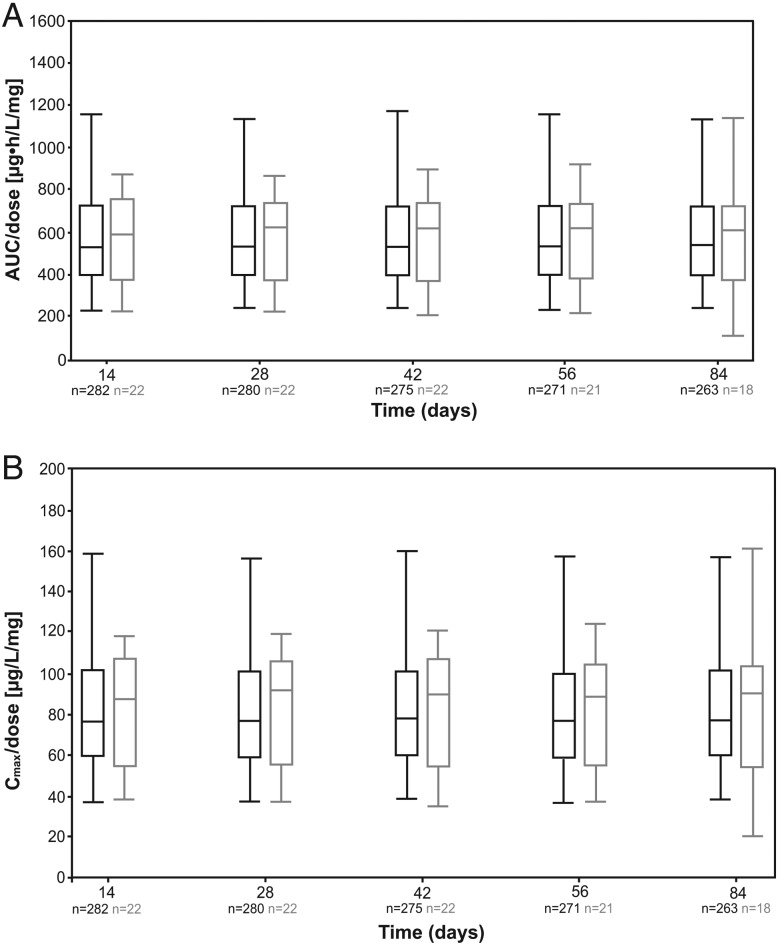

Pharmacokinetics of riociguat

An analysis of the pharmacokinetics of riociguat showed comparable area under the plasma concentration–time curve and maximum plasma concentration between patients with PAH-CHD and patients with other PAH aetiologies in the PATENT-1 population (figure 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Box plots for dose-normalised area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC; A) and maximum riociguat plasma concentration (Cmax; B) in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD) and patients with other PAH aetiologies in the Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 population. Plots show the fifth, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles. Grey boxes represent patients with PAH-CHD and black boxes represent patients with other PAH aetiologies.

Safety

The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) are shown in table 4. Overall, six serious AEs were reported in four (11%) patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-1: one event each of intra-abdominal haemorrhage (riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group); right ventricular failure and worsening PAH (riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group); and loss of consciousness, pneumothorax and supraventricular tachycardia (placebo group). None were considered related to study drug by the investigators. The case of intra-abdominal haemorrhage occurred in a 32-year-old woman and resolved without the need for riociguat dose adjustment or withdrawal. The patient completed PATENT-1 and is continuing to receive riociguat therapy in the PATENT-2 long-term extension at the time of writing (March 2015).

Table 4.

Treatment-emergent adverse events in the subgroup of patients with PAH-CHD in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1

| Adverse event, n (%) | Placebo (n=12) | Riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum (n=15) |

Riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum (n=8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 10 (83) | 14 (93) | 6 (75) |

| Adverse events occurring in ≥10% of patients in any treatment group | |||

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 4 (27) | 0 |

| Headache | 2 (17) | 4 (27) | 2 (25) |

| Dizziness | 2 (17) | 3 (20) | 2 (25) |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Anaemia | 0 | 2 (13) | 1 (13) |

| Epistaxis | 0 | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (8) | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Palpitations | 2 (17) | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Peripheral oedema | 1 (8) | 2 (13) | 1 (13) |

| Back pain | 2 (17) | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Face oedema | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 1 (13) |

| Hiccups | 0 | 1 (7) | 1 (13) |

| Hypokalaemia | 0 | 1 (7) | 1 (13) |

| Anxiety | 1 (8) | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Asthenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Blood potassium decreased | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Gastritis | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Insomnia | 1 (8) | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Nausea | 2 (17) | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Right ventricular failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Vomiting | 2 (17) | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Worsening PAH | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) |

| Chest discomfort | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnoea | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 |

CHD, congenital heart disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

There was one death in the riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group (due to right ventricular failure and worsening PAH); all other serious AEs resolved. In PATENT-1, one patient discontinued treatment owing to AEs of supraventricular tachycardia and hypotension (riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group; considered drug related) and one patient discontinued owing to a serious AE of pneumothorax (placebo group; not considered drug related).

Long-term extension study (PATENT-2)

Of 35 patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-1, 33 (94%) entered PATENT-2. At the March 2014 cut-off, median (range) riociguat treatment duration in patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-2 was 139 (<1–231) weeks overall, with median (range) treatment durations in the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum, riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum and placebo groups of 140 (4–231), 127 (90–192) and 127 (<1–217) weeks, respectively.

Improvements in 6MWD in patients with PAH-CHD in the riociguat groups in PATENT-1 were sustained at 2 years of PATENT-2 (mean±SD change from PATENT-1 baseline to 2 years of PATENT-2 was +108±107 m in the former riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group, n=10; figure 1B). Furthermore, patients with PAH-CHD in the placebo group of PATENT-1 showed a comparable increase in 6MWD to the former riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group, and to a lesser extent the former riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group, following transition to riociguat in PATENT-2 (mean±SD change from PATENT-1 baseline to 2 years of PATENT-2 was 34±84 m in the former placebo group, n=9, and 53±90 m in the former riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group, n=6; figure 1B). The mean±SD change from baseline in 6MWD in the overall population of patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-2 was +78±81 m at 1 year (n=28) and +68±97 m at 2 years (n=25). Sustained improvements in WHO FC were also seen in patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-2. At 1 and 2 years of PATENT-2, WHO FC had improved/stabilised/worsened in 39%/57%/4% (n=28) and 32%/60%/8% (n=25), respectively, of patients with PAH-CHD. At the March 2014 cut-off of PATENT-2, eight (24%) patients with PAH-CHD had experienced clinical worsening (table 5).

Table 5.

Incidence of clinical worsening in patients with PAH-CHD in Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-2

| Clinical worsening event, n (%)* | Total (n=33) |

|---|---|

| Patients with clinical worsening | 8 (24) |

| Hospitalisation due to PH | 4 (12) |

| Start of new PH treatment | 7 (21) |

| Decrease in 6MWD due to PH | 2 (6) |

| Death | 4 (12) |

*One patient can experience more than one event.

6MWD, 6-min walking distance; CHD, congenital heart disease; PAH, pulmonary atrial hypertension; PH, pulmonary hypertension.

Discussion

The number of adult patients with PAH-CHD is increasing due to improvements in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of CHD. This, coupled with the heterogeneous nature of PAH-CHD, presents a challenge to physicians treating adult patients with PAH-CHD and, in particular, patients with residual or recurrent PAH after defect closure who commonly have a poor prognosis.16 Furthermore, there have been few randomised controlled trials assessing PAH-specific therapies in patients with PAH-CHD, and these have focused on patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. No randomised controlled studies have prospectively evaluated PAH-specific therapies in patients with CHD and PAH after defect repair.

The recent randomised controlled phase III study in adult patients with PAH (PATENT-1) and its long-term extension study (PATENT-2) showed that riociguat significantly improved a number of efficacy outcomes versus placebo, including 6MWD, NT-proBNP and WHO FC,13 and that these benefits were sustained at 2 years.14 15 In this exploratory analysis of the subgroup of patients with persistent/recurrent PAH following complete surgical repair of CHD from these studies, riociguat improved 6MWD in the PAH-CHD population, consistent with that observed in the overall PATENT-1 population (increases in 6MWD in the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum groups of 39 m in the PAH-CHD subgroup and 30 m in the overall study population).13 Furthermore, the improvement in 6MWD in the PAH-CHD population appeared to be sustained at 2 years, again similar to the findings in the overall PATENT-2 population (increases of 68 and 47 m in the PAH-CHD subgroup and overall study population, respectively).15 The improvement in 6MWD with riociguat in patients with PAH-CHD in PATENT-1 is within the range of the minimally important difference (the smallest change or difference in outcome measure, perceived as beneficial, that would justify a change in a patient's medical management) of 33–42 m for 6MWD in patients with PAH.17 18

Improvements in secondary efficacy variables with riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum in the PAH-CHD subgroup appeared to be consistent with the findings in the overall PATENT-1 population. In particular, at week 12, riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum decreased NT-proBNP levels from baseline by 164 pg/mL in the PAH-CHD subgroup, compared with a decrease of 198 pg/mL in the overall PATENT-1 population. Riociguat up to 2.5 mg three times daily also improved WHO FC in patients with PAH-CHD consistent with improvements observed in the overall study population (21%/79%/0% and 21%/76%/4% were improved/stabilised/worsened vs baseline in the PAH-CHD subgroup and overall population, respectively). Riociguat improved a range of other secondary clinical outcomes in patients with PAH-CHD including haemodynamics, Borg dyspnoea score and quality of life. Importantly, the treatment benefits seen with riociguat in 6MWD and WHO FC were sustained at 2 years in patients with PAH-CHD. In the overall PATENT-1 study, riociguat improved a range of haemodynamic parameters, and a small but significant correlation has been shown between change in 6MWD and change in haemodynamics, indicating the importance of assessing several parameters to evaluate the overall treatment effect of a therapy in the individual patient.19 In this study, the improvements in PVR, mPAP, right atrial pressure and cardiac index seen with riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum in the PAH-CHD subgroup were similar to those observed in the overall PATENT-1 study population.

In PATENT-1, the efficacy findings in the riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group were consistent with the riociguat 2.5 mg–maximum group of patients with PAH-CHD and also comparable with the riociguat groups in the overall study population. In addition, exposure to riociguat in patients with PAH-CHD was generally comparable with that in patients with other PAH aetiologies in the PATENT-1 population. However, the long-term response in PATENT-2 appeared to be less pronounced in patients in the former riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum or former placebo groups versus the 2.5 mg–maximum group (figure 1B).

Riociguat was well tolerated in patients with PAH over 12 weeks in PATENT-113 and at 2 years in PATENT-2.14 15 Riociguat was also well tolerated in the subgroup of patients with PAH-CHD; the incidences of syncope and hypotension—AEs that have been reported as occurring frequently with riociguat—were relatively low in these patients. Haemoptysis is a serious, often life-threatening, complication of PAH-CHD.20 Riociguat has been associated with a potentially increased risk of respiratory tract bleeding.9 10 One (3%) serious AE of respiratory tract bleeding (pulmonary haemorrhage) was reported in the PAH-CHD subgroup in PATENT-2; this incidence is comparable to that seen in the overall study population.14 15

Currently, most studies of PAH-specific therapies (including ERAs and PDE-5 inhibitors) in patients with PAH-CHD are small, retrospective or have no control arm.21–23 In addition, most studies either do not differentiate between the various aetiologies of PAH-CHD or focus on a particular subtype, such as Eisenmenger syndrome. Therefore, it is difficult to make comparisons between these studies and the PATENT subanalysis data presented here.

In the PATENT studies, patients in the PAH-CHD subgroup all had persistent/recurrent PAH following complete surgical or interventional repair of CHD. This fourth clinical subclass of PAH-CHD seems to represent one of the largest groups of PAH patients in recent registry studies,24 with a remarkably high estimated prevalence in adults with CHD of almost 6%.24 These patients have a particularly poor prognosis; the estimated 20-year survival rate is 36% and is significantly worse than the survival rates in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome or systemic-to-pulmonary shunts.16 The reasons for the worse prognosis of these patients compared with patients with Eisenmenger syndrome are unclear, but may include the lack of a possible pulmonary-to-systemic shunt in the case of elevation of PVR, leading to right ventricular failure in the absence of a ‘pop off’ possibility through the hole or impaired adaptation of the right ventricle to an increase in afterload during the first months/years of life. An increase in mortality rate in patients with persistent/recurrent PAH after defect closure compared with patients with Eisenmenger syndrome has also been reported in the paediatric age group.25 However, in this series, PAH was likely to be a relatively early complication after cardiac defect correction (the average age of the children was 6.9 years), compared with reported adult populations in which PAH was detected very late after correction.26

The exploratory subgroup analysis data presented here suggest that riociguat is well tolerated and may be effective in improving a range of clinical outcomes in patients with persistent/recurrent PAH following surgically corrected CHD. Treatment goals for PAH in both adults and children with PAH-CHD include improvements in WHO FC and NT-proBNP levels,27–30 both of which were improved with riociguat in this subanalysis.

A limitation of this subgroup analysis is that PATENT-1 and PATENT-2 were not designed to show statistically significant differences in subgroup populations. Therefore, the data presented should be considered exploratory. In addition, the patient numbers in the subgroups were low, particularly in the riociguat 1.5 mg–maximum group.

In conclusion, this subgroup analysis showed that riociguat was well tolerated in patients with persistent/recurrent PAH following complete surgical repair of CHD and improved a range of clinical outcomes including 6MWD, PVR, WHO FC and NT-proBNP.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a serious and progressive condition that can lead to death due to right heart failure, is a common complication in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD). The prognosis for patients who develop persistent/recurrent PAH after surgical or interventional correction of CHD is particularly poor and presents a challenge to treatment.

What might this study add?

This post hoc subgroup analysis of the Pulmonary Arterial hyperTENsion sGC-stimulator Trial-1 (PATENT-1) and PATENT-2 studies shows that riociguat, a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator approved for PAH, is a safe and effective treatment in adult patients with persistent/recurrent PAH after correction of CHD. Riociguat improved a range of clinical outcomes versus placebo in these patients, and improvements in exercise capacity and functional capacity persisted at 2 years in the PATENT-2 long-term extension.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

These data suggest that riociguat is a promising treatment for adult patients with persistent/recurrent PAH after correction of CHD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Bayer Pharma AG (Berlin, Germany). Editorial assistance was provided by Adelphi Communications Ltd (Bollington, UK), sponsored by Bayer Pharma AG.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and the drafting, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Funding: Bayer Pharma AG.

Competing interests: SR has received fees for lectures and/or consultancy from Actavis, Actelion, Bayer Pharma AG, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Co, Novartis, Pfizer, and United Therapeutics and fees for clinical trials/research support from Actavis, Actelion, Bayer Pharma AG, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and United Therapeutics. H-AG has received grants from Actelion, Bayer Pharma AG, Ergonex and Pfizer and personal fees from Actelion, Bayer Pharma AG, Ergonex, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis and Pfizer. MB has received grants from Actelion and Bayer Pharma AG and personal fees from Actelion, Bayer Pharma AG, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Pfizer. DI has acted as a consultant to Bayer Pharma AG through a contract between the University of Colorado and Bayer Pharma AG. RF, AF, GW and SS are full-time employees of Bayer Pharma AG.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of all participating centres.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. . Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1219–63. 10.1183/09031936.00139009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Wilkins MR, et al. . Mechanisms of disease: pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:443–55. 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulder BJ. Changing demographics of pulmonary arterial hypertension in congenital heart disease. Eur Respir Rev 2010;19:308–13. 10.1183/09059180.00007910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Alto M, Mahadevan VS. Pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Eur Respir Rev 2012;21:328–37. 10.1183/09059180.00004712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatzoulis MA, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Beghetti M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in paediatric and adult patients with congenital heart disease. Eur Respir Rev 2009;18:154–61. 10.1183/09059180.00003309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. . Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:D34–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marelli AJ, Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, et al. . Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation 2014;130:749–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galiè N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, et al. . Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation 2006;114:48–54. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayer Pharma AG. Adempas (riociguat) EU Summary of Product Characteristics 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002737/WC500165034.pdf

- 10.Bayer Pharma AG. Adempas® US prescribing information. 2013. http://labeling.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Adempas_PI.pdf

- 11.Stasch JP, Evgenov OV. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators in pulmonary hypertension. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2013;218:279–313. 10.1007/978-3-642-38664-0_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Follmann M, Griebenow N, Hahn MG, et al. . The chemistry and biology of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and activators. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2013;52:9442–62. 10.1002/anie.201302588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghofrani HA, Galiè N, Grimminger F, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013;369:330–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin LJ, Galiè N, Grimminger F, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a long-term extension study (PATENT-2). Eur Respir J 2015;45:1303–13. 10.1183/09031936.00090614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin LJ, Galiè N, Grimminger F, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH): 2-year results from the PATENT-2 long-term extension (abstract). Eur Respir J Suppl 2014;44:1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manes A, Palazzini M, Leci E, et al. . Current era survival of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease: a comparison between clinical subgroups. Eur Heart J 2014;35:716–24. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabler NB, French B, Strom BL, et al. . Validation of 6-minute walk distance as a surrogate end point in pulmonary arterial hypertension trials. Circulation 2012;126:349–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathai SC, Puhan MA, Lam D, et al. . The minimal important difference in the 6-minute walk test for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:428–33. 10.1164/rccm.201203-0480OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galiè N, Grimminger F, Grünig E, et al. . Correlation of improvements in hemodynamics and exercise capacity in patients with PAH: Results from the phase III PATENT-1 study. Eur Respir J 2013;42:1784. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roofthooft MT, Douwes JM, Vrijlandt EJ, et al. . Frequency and prognostic significance of hemoptysis in pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1505–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monfredi O, Griffiths L, Clarke B, et al. . Efficacy and safety of bosentan for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1483–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng WJ, Lu XL, Xiong CM, et al. . The efficacy and safety of sildenafil in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with the different types of congenital heart disease. Clin Cardiol 2011;34:513–18. 10.1002/clc.20917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu XL, Xiong CM, Shan GL, et al. . Impact of sildenafil therapy on pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults with congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc Ther 2010;28:350–5. 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Riel AC, Schuuring MJ, van Hessen ID, et al. . Contemporary prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in adult congenital heart disease following the updated clinical classification. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:299–305. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haworth SG, Hislop AA. Treatment and survival in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension: the UK Pulmonary Hypertension Service for Children 2001–2006. Heart 2009;95:312–17. 10.1136/hrt.2008.150086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manes A, Palazzini M, Tremblay G, et al. . Combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) reduces consistently clinical worsening as compared to monotherapy: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (abstract). Eur Heart J 2014;35 (Abstract supplement). 10.1093/eurheartj/eht072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ploegstra MJ, Douwes JM, Roofthooft MT, et al. . Identification of treatment goals in paediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1616–26. 10.1183/09031936.00030414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nickel N, Golpon H, Greer M, et al. . The prognostic impact of follow-up assessments in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012;39:589–96. 10.1183/09031936.00092311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barst RJ, Chung L, Zamanian RT, et al. . Functional class improvement and 3-year survival outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the REVEAL Registry. Chest 2013;144:160–8. 10.1378/chest.12-2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivy DD, Abman SH, Barst RJ, et al. . Pediatric pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:D117–26. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.