Abstract

There is good evidence that morbidity and mortality increase for young persons (YP) following the move from paediatric to adult services. Studies show that effective transition between paediatric and adult care improves long-term outcomes. Many of the issues faced by young people across subspecialties with a long-term condition are generic. This article sets out some of the obstacles that have delayed the implementation of effective transition. It reports on a successful generic transition programme ‘Ready Steady Go’ that has been implemented within a large National Health Service teaching hospital in the UK, with secondary and tertiary paediatric services, where it is now established as part of routine care.

Keywords: Adolescent Health, Cardiology, Cystic Fibrosis, Diabetes, Nephrology, Patient empowerment

Introduction

There is good evidence that morbidity and mortality increase for young persons (YP) following the move from paediatric to adult services.1–5 In response to this evidence, there have been a number of reports and guidelines seeking to reduce the risks associated with moving to adult services.6–9 Central to this work is the concept of transition10—a gradual process of empowerment that equips young people with the skills and knowledge necessary to manage their own healthcare in paediatric and adult services. Effective transition has been shown to improve long-term outcomes11–13 and to improve the YP experience.14 In addition, the importance of a holistic programme that addresses the medical, psychosocial and vocational needs of the YP within YP-friendly services has also been recognised.14–17 However, despite the evidence of the risks associated with a poorly managed move to adult services and availability of potential solutions, studies continue to show that the move remains ad hoc and an unsatisfactory experience for a significant number of YP and their families.18

This paper sets out some of the obstacles that have prevented progress and reports on a successful transition programme implemented within a large National Health Service (NHS) teaching hospital in the UK, with secondary and tertiary paediatric services, where it is now established as part of routine care. The programme is also being adopted by hospitals across the UK and gaining international interest.

What are the barriers to high-quality transition?

The development and introduction of high-quality transition, supported by a simple tool, has been delayed by numerous misconceptions (see box 1).

Box 1. Common misconceptions preventing timely implementation of effective transition.

Transition and transfer—what is the difference?

Transition is sometimes treated as an event rather than a gradual process of empowerment. Some healthcare professionals report they have transition arrangements in place but on closer examination it appears that they are simply transferring the young persons (YP) to adult services with no empowerment of the YP or carer.19

Do you need to have a ‘transition clinic’ in place in order to start transition?

Some healthcare professionals assume that transition can only occur in a transition clinic in the presence of a specialist transition team and cannot occur in their usual clinic. This is not the case. Empowering YP and equipping them with the knowledge and skills to manage their healthcare can occur in any clinic.

Can transition begin without an identified adult team to which the YP's care can be transferred?

Some paediatricians state that transition cannot occur without the presence of an adult physician in the paediatric clinic. Joint clinics with the adult team is the ideal but transition should not be delayed due to the non-availability or identification of an adult team. Transition should focus on preparing the YP for the adult service whilst an adult team in primary, secondary or tertiary care is being identified. Those YP that are being transferred to primary care for long-term follow-up should also undergo the same transition process.

Does a transition tool need to be subspecialty specific?

It is a common assumption among some paediatricians that their specialty and locality requires a unique approach to transition.20 21 However, many of the issues faced by YP during transition are generic regardless of the nature of their long-term condition. This allows a generic programme to be adopted.

Can a YP with learning disabilities undergo transition?

Some healthcare professionals and carers assume that YP with significant learning difficulties are not able to be involved in the transition process. However, studies show that they should also be prepared for adult services as far as possible22 whilst at the same time supporting their carers through the transition process using the same programme;23 research continues in this challenging area.24

At what age should transition be started?

It is a common belief among some healthcare professionals that transition should start a year or so prior to transfer to adult services. Studies show that starting transition at around 11–12 years of age leads to better knowledge and skills,25 resulting in improved long-term outcomes. Starting around 11 years of age or soon after ensures the YP and carer has more time to prepare for adult services and can move through the process at their own pace. For many YP, this is also a time of change as they are moving from junior to secondary school, are taking on more responsibility and ‘feeling like big boys and girls’.

Is it right to introduce an additional goal of effective transition for YP with a long-term condition who are already going through significant challenges associated with adolescence?

YP with a long-term medical condition have a great deal in common as they face the emotional and intellectual challenges of becoming an adult. There are often challenges with this age group that may be biologically driven even when there are no cognitive consequences associated with the underlying chronic disease, but these can be overcome if the process continues with a well-trusted team over a long period of time.

The challenge has been to develop a generic transition tool that is simple and easy to use for the YP and carer, is accepted and addresses all the healthcare issues considered important by subspecialty healthcare professionals (HCPs) as well as being straightforward and economical to implement. In short, a means of engendering a cultural change towards transition is required; Ready Steady Go is designed to support such a change.

What is Ready Steady Go?

Aware of the evidence and taking into account the principles of transition, a large NHS teaching hospital in the UK, with secondary and tertiary paediatric services, has developed and implemented a transition programme called Ready Steady Go. It is a generic programme for YP with a long-term condition aged 11+ years. It can be used across all subspecialties. Ready Steady Go is a structured, but where necessary adaptable, transition programme. A key principle throughout Ready Steady Go is ‘empowering’ the YP to take control of their lives and equipping them with the necessary skills and knowledge to manage their own healthcare confidently and successfully in both paediatric and adult services. This is initiated through the completion of a series of questionnaires.

The scope of the questionnaires is as follows:

To assess knowledge of their condition, their treatments and that they know who's who in their healthcare team.

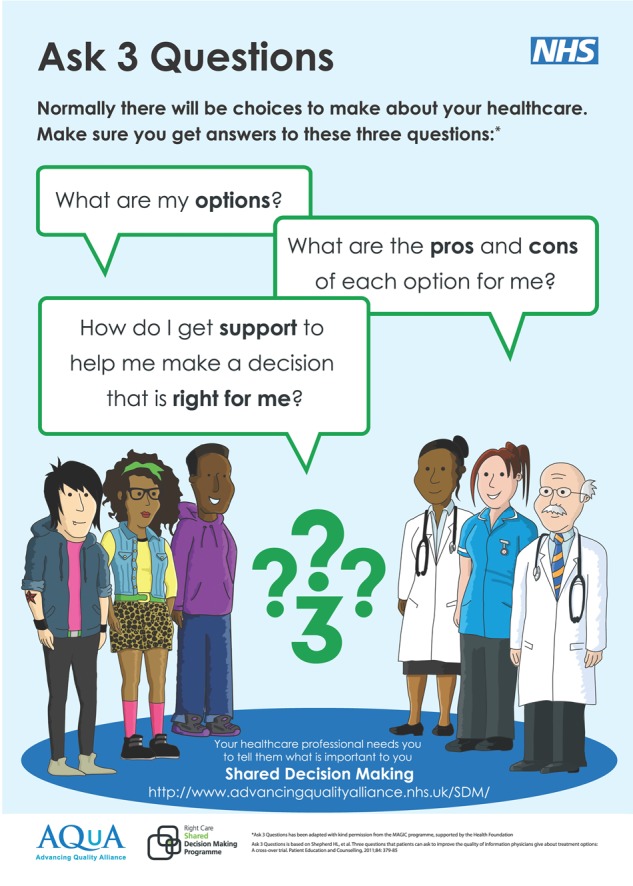

To support the development of self-advocacy (speaking up for yourself). The extent to which they can speak up for themselves and ask their own questions in clinic and be involved in shared decision–making, for example, Ask 3 Questions (figure 1) is an important measure of progress. The programme works towards the YP being seen in clinic on their own, being responsible for changing their appointments and knowing from whom and when they should seek help.

To develop an understanding of the issues around a healthy lifestyle, sexual heath and where relevant pregnancy.

To review educational and vocational issues to ensure the YP has high but also realistic expectations and has a plan to achieve their potential.

To identify any psychosocial issues.

To develop an understanding of the concept of transition.

Figure 1.

Ask 3 Questions (reproduced by kind permission of Advancing Quality Alliance).

The questions are deliberately broad, providing the opportunity for the HCP to ask targeted questions specific to their condition. The answers are used as a basis for starting discussion that reveals whether the extent of the patient's perception of their own knowledge and skills is justified. Some are prone to misrepresentation—accidentally or otherwise, this is readily identified through discussion and the underlying issues can then be addressed. The questionnaires also prompt appropriate engagement over potentially difficult issues such as sex and psychosocial concerns. Any issues that may arise are carefully addressed prior to transfer to adult services.

The intent of Ready Steady Go is that the YP will be able to manage their healthcare successfully not just in their local adult service but in any adult service across the country—whether or not they have previously met the adult physician or general practitioner (GP) to whom their care is transferred. Where the YP has learning difficulties, the carer works through the Ready Steady Go programme with the YP engaging as much as possible so that they too are prepared for the move to adult services; the programme allowing all concerns/issues to be carefully addressed and progress monitored prior to transfer.

Successful transition also needs carers to be part of the transition process. This is achieved by engaging with the carer over issues that are raised during the completion of the parent/carer questionnaire. Ready Steady Go actively involves and supports them through the process, thus making it easier for them to ‘let go’ and enabling the YP to gain independence.

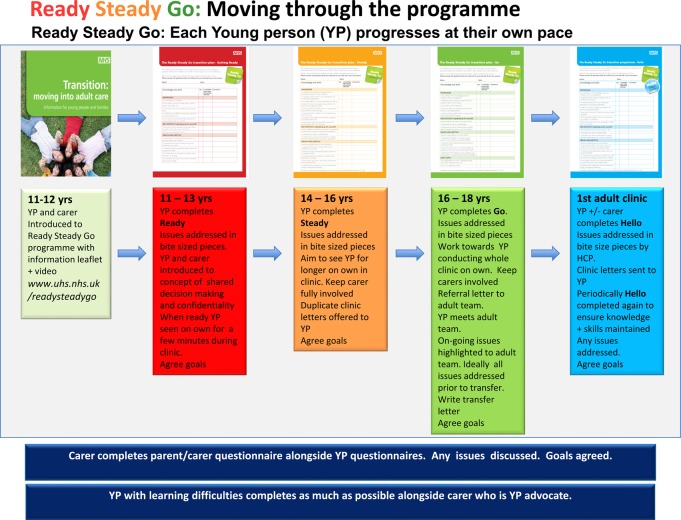

Moving through the Ready Steady Go programme (figure 2)

Figure 2.

Ready Steady Go: moving through the programme.

YP and their carers start the Ready Steady Go programme at around 11 years of age, if developmentally appropriate. They are introduced to ‘Ready Steady Go’ through an introductory video and the ‘Transition: moving into adult care’ information leaflet. These resources and all other supporting documentation in the article can be found at http://www.uhs.nhs.uk/readysteadygo.

The ‘Transition: moving into adult care’ leaflet introduces

the concept of transition and why the YP will eventually need to move to adult services;

the timing of the move to adult services and to which adult service their care may be transferred;

the topics that will be covered in ‘Ready Steady Go’ and who will provide the information and support to help them work successfully through the programme;

how the family can help support the YP through the process and some questions they may like to ask their healthcare team.

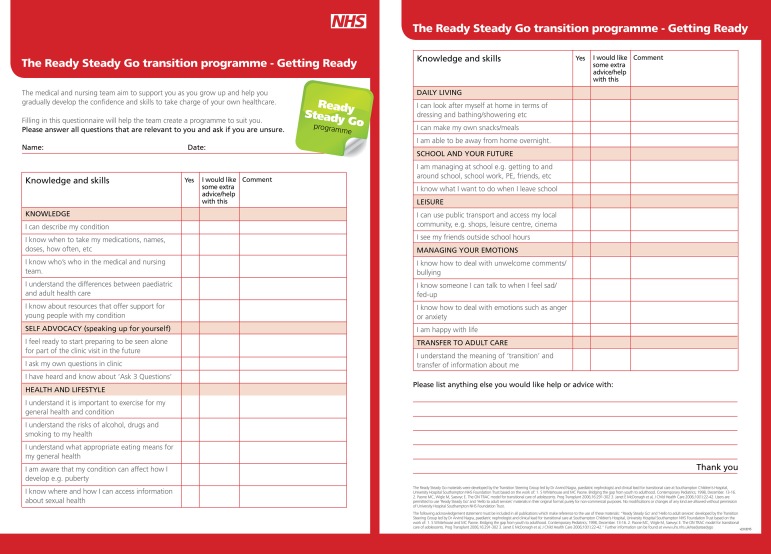

At the next consultation, the YP completes the ‘Getting Ready’ questionnaire (figure 3), which, through a series of structured questions, is designed to establish what needs to be done for a successful move to adult services. The issues are not addressed in a single consultation but over the following 1–2 years in ‘bite-sized pieces’ at a pace appropriate for the YP and carer. Goals are agreed with the YP and carer. Progress and goals are documented in the transition plan by the HCP, which remains in the patient notes. The carer completes a separate questionnaire that follows the same format as the Ready Steady Go questionnaires, alongside the YP, to ensure that they are also supported through the transition process. It is during this time the YP and carer is introduced to the concepts of confidentiality and shared decision-making (Ask 3 Questions). The YP is also encouraged to start speaking up for themselves and spend a few minutes of the consultation without their carer being present.

Figure 3.

Getting Ready questionnaire.

In due course around age 13–14 years, the YP completes the ‘Steady’ questionnaire, which covers the topics in greater depth. It is used to monitor progress on existing issues and ensure that any new issues that may arise are also identified and tackled at an appropriate pace over the following two years, again with agreed targets and goal setting. If necessary, the carer may also fill in the parent/carer questionnaire again to ensure issues are addressed. During this stage, the YP is encouraged to engage in more depth in their healthcare and spend more time in the consultation on their own. It is still appropriate for the carer to be involved in a significant part of the consultation—this will be determined by the progress of the YP. The YP is also offered duplicate clinic letter during this stage.

The ‘Go’ questionnaire is started at around 16 years of age to ensure that they have all the skills and knowledge in place to 'Go' to adult services. By the end of the Go stage, the YP should have the confidence and ability to conduct the whole clinic consultation on their own. Any new issues are highlighted and once again goals are agreed and worked towards in preparation for the move to adult services. During the ‘Go’ stage, the YP is introduced to the adult team. The introduction should be at least a year prior to transfer and earlier in the programme if resources permit. The number of joint clinics with the adult team will be dependent on the needs of the YP and carer. The actual timing of the move to adult services is one that is mutually agreed by the YP, parents or carers and medical professionals. Prior to the move, a letter is written to the adult team summarising the medical condition of the YP, their progress through the Ready Steady Go programme and any issues that are outstanding or of concern. Where the long-term care is to be delivered solely in primary care services, the letter should also include a detailed follow-up plan for the GP and YP.

Arrival in adult services: Hello

For a seamless transfer to adult services, the YP completes a ‘Hello to Adult Services’ at their first clinic appointment in adult services. The ‘Hello’ questionnaire follows the same format as the ‘Go’ questionnaire for familiarity and to support the continued delivery of holistic care, self-management and shared decision-making in adult services. Any issues raised are addressed, goals set, progress monitored and recorded in the Hello to Adult Services transition plan . Periodically the ‘Hello’ questionnaire is reused to ensure they maintain knowledge and skill levels and that any new or ongoing concerns or problems are addressed. The carer can complete a separate questionnaire if considered necessary and they wish to do so.

There is a discrete ‘Hello to Adult Services’ programme that can be found at http://www.uhs.nhs.uk/OurServices/Childhealth/TransitiontoadultcareReady SteadyGo/Hello-to-adult-services.aspx. This follows the same format as Ready Steady Go and is used for YP and adults whose first presentation with a long-term condition is in adult services. Age and subspecialty is not a barrier to using the programme.

Making it happen

Ready Steady Go is being implemented within a large NHS teaching hospital in the UK, with secondary and tertiary paediatric services, where it is now established as part of routine care. The programme is promoted through standard approaches such as staff briefings and workshops and the use of posters in clinic. More uniquely, 4 weeks a year ‘11+ clinic weeks’ are held. All clinics during these weeks are intended for YP aged 11+ years. These targeted weeks allow the physical environment to be made ‘YP friendly’ and encourage the YP to start taking the first steps towards independence of care as they watch other YP/peers go through the same process. Seeing other YP and carers go through the programme also helps carers understand that letting the YP become more responsible for their care is expected and to be encouraged.

In addition, the ‘11+ clinic weeks’ focus health professionals on transition and encourage them to adopt the Ready Steady Go Programme as part of their regular clinical practice so that effective transition becomes part of their routine throughout the year.

Initially there was reluctance to support the implementation of 11+ clinic weeks due to concerns about an increase in the administrative burden to cohort YP. This was overcome once the healthcare teams and hospital management appreciated that the majority of appointments are follow-up reviews so to cohort these YP should not increase administration time or require an increase in resources. The appointments for YP have started to come in-step with the 11+ clinic weeks, and >80% of the patients attending clinic during these weeks are 11 years of age or older. There is no expectation, or need, to achieve figures of 100% as urgent clinical reviews of younger patients are still sometimes required.

What do the users of Ready Steady Go think of the programme?

The programme has been in place for 3 years. A survey was conducted through use of a questionnaire to assess the effectiveness of the documentation that underpins the Ready Steady Go programme. This was completed by YP, carers and HCPs who were part of the Ready Steady Go programme. Just over a hundred questionnaires were returned. Feedback from all groups was excellent, showing that the Ready Steady Go documentation is simple to understand, easy to use, helps address the key issues for a good transition to adult services and improves clinical practice.

HCPs reported that they now addressed their conversation to the YP and not solely the carer; copies of letters were being offered and sent to the YP. In particular, difficult issues were being addressed in clinic and a more holistic approach was being adopted as a result of using the questionnaires. These findings were also echoed by some of the YP and their parents/carers.

Two minor areas of concern were reported on which the following observations are made.

Relevance of all questions and its use in YP with learning disabilities

It is accepted that using a generic tool may result in a few unnecessary questions but the YP is asked only to complete those questions they think are relevant to them and to ask their healthcare provider if they are unsure. This allows the YP with a long-term condition that involves multiple specialties to use only one tool. It also enables the YP to experience supportive camaraderie through being on the same programme as their peers. Where the YP has learning difficulties, the carer works through the Ready Steady Go programme with the YP engaging as much as possible. Carers with a severely disabled YP also start Ready Steady Go so that they too are prepared for the move to adult services; the programme allowing concerns/issues to be carefully addressed and progress monitored prior to transfer.

We believe that the benefits of a generic questionnaire significantly outweigh any minor frustrations over the relevance of certain questions. This has been echoed by many young people, carers and HCPs.

Increase in consultation time

It is acknowledged that there is a marginal increase in consultation time when Ready Steady Go is first introduced to the YP and their carer. This is anticipated to decrease with the introduction of the Ready Steady Go information video for the YP and carers.

It is not intended that all the potential issues covered by the programme are addressed in a single consultation, rather that they should be worked through over a number of consultations over a period of years.

The earlier the programme starts, the longer the YP has to prepare for adult services and in due course this allows for shorter and more efficient consultations. At steady state there should be no increase in the time to run a clinic session; although a YP new to the programme may take a little longer, those already on the programme should take less time.

Next steps

The following initiatives are underway to promote the Ready Steady Go programme and ease its implementation.

An information video for the YP and carers to introduce the Ready Steady Go programme has just been produced. This will reduce the time taken in clinic to introduce the programme to young people and their carers. It is also intended to address any concerns the YP and carer may have about starting the programme and emphasise the benefits of the programme.

Production of a training video for HCP on how to use Ready Steady Go.

An online version of Ready Steady Go and Hello to Adult Services, on ‘My Health Record’ (MHR) is currently being piloted. It allows YP and carers to complete questionnaires online and return them to their HCP. The completed questionnaires are stored in their electronic patient records. The HCP can send additional generic information and, if required, disease-specific links in answer to the responses on the questionnaire. MHR links into the electronic patient record and allows patients to have access to their medical letters, results, appointments and a list of their medications with the option of setting reminders. The information in MHR stays with the patient and can be shared with anyone the patient so chooses—both nationally and internationally. Studies show this improves YP experience and engagement.26

Wider implementation of the ‘Hello to Adult Services' programme across adult subspecialties as many of the issues facing any patient with a long-term condition are similar regardless of age. Anecdotal evidence indicates adult patients and physicians strongly welcome the Hello programme.

Finalisation of a 'Hello to Children's Services' programme that follows the Ready Steady Go format for parents and carers of young children diagnosed with long-term conditions. They too have the same issues that need addressing using a structured approach.

A study to measure the effectiveness of the Ready Steady Go programme across subspecialties and all age groups looking at patient experience, engagement, morbidity and mortality will be conducted. It is anticipated that the study will show better clinical outcomes with a reduction in morbidity, mortality and significant savings to the NHS in the longer term.

Summary

The Ready Steady Go programme

Is designed to deliver high-quality transition for YP across all subspecialties, which is in line with recent publications on Transition15 (see box 2).

Addresses the full range of issues for good transition and facilitates discussion in greater depth where required by the YP, carer or HCP.

Is simple to understand and use. It has been widely and enthusiastically adopted and has led to a cultural change in healthcare practice where implemented.

Improves clinical practice.

Empowers the YP to manage their healthcare confidently and successfully in both paediatric and adult services.

Is easy to implement and requires very little additional resource.

Box 2. Recommendation 2 of the Care Quality Commission: from the pond into the sea. Children's transition to adult health services.

A key accountable individual responsible for supporting their move to adult health services.

A documented transition plan that includes their health needs.

A communication or ‘health passport’ to ensure relevant professionals have access to essential information about the young person.

Health services provided in an appropriate environment that takes account of their needs without gaps in provision between children's and adult services.

Training and advice to prepare them and their parents for the transition to adult care including consent and advocacy.

Respite and short break facilities available to meet their needs and those of their families.

Children's services provided until adult services take over.

An effectively completed assessment of their carers’ needs.

Adequate access to independent advocates for young people.

Ready Steady Go has been successfully introduced and implemented within a large NHS teaching hospital in the UK, with secondary and tertiary paediatric services, where it is now established as part of routine care. It is also being adopted widely across the UK and there is developing international interest in the programme.

The Ready Steady Go materials were developed by the Transition Steering Group led by Dr Arvind Nagra, paediatric nephrologist and clinical lead for transitional care at Southampton Children's Hospital, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust based on the work of the following:

S Whitehouse and MC Paone. Bridging the gap from youth to adulthood. Contemporary Pediatrics 1998:13–16.

Paone MC, Wigle M, Saewyc E. The ON TRAC model for transitional care of adolescents. Prog Transplant 2006;16:291–302

Janet E McDonagh, et al. J Child Health Care 2006;10:22–42.

Users are permitted to use ‘Ready Steady Go’ and ‘Hello to adult services’ materials in their original format purely for non-commercial purposes. No modifications or changes of any kind are allowed without permission of University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

The following acknowledgement statement must be included in all publications which make reference to the use of these materials: “‘Ready Steady Go’ and ‘Hello to adult services’ developed by the Transition Steering Group led by Dr Arvind Nagra, paediatric nephrologist and clinical lead for transitional care at Southampton Children's Hospital, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust based on the work of: 1. S Whitehouse and MC Paone. Bridging the gap from youth to adulthood. Contemporary Pediatrics; 1998, December. 13–16. 2. Paone MC, Wigle M, Saewyc E. The ON TRAC model for transitional care of adolescents. Prog Transplant 2006;16:291–302 3. Janet E McDonagh et al, J Child Health Care 2006;10(1):22–42.” Further information can be found at www.uhs.nhs.uk/readysteadygo

Test your knowledge.

When would you normally consider starting transition? 1 year before transfer to adult services Or at: 11, 12, 13 , 14 , 15 , 16, 17 , 18 years

Does an adult physician need to be identified prior to starting transition? Yes No

Is transition required if a YP with an long term condition is discharged back to their GP for follow-up? Yes No

Would you start transition for a YP with a learning disability? Yes No

Is a disease-specific programme required for transition? Yes No

The answers are at the end of the references.

Answers to the quiz on page 319.

(1) 11 years. (2) No. (3) Yes. (4) Yes. (5) No.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the input of Dr McDonagh and her co-workers to the development of our Ready Steady Go materials. Also to Martin Stephens for advice in drafting this paper and the Wessex AHSN for helping to support and promote the programme.

Correction notice: This paper has been amended since it was published Online First. References 15 and 17 have been added and the acknowledgement has been amended.

Twitter: Follow Ready Steady Go SCH at @ReadySteadyGo3

Collaborators: Dr Gary Connett, Amanda-Lea Harris, Judi Maddison, Denise Franks, Louise Hooker.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Dr Gary Connett, Amanda-Lea Harris, Judi Maddison, Denise Franks, and Louise Hooker

References

- 1.Kipps S, Bahu T, Ong K, et al. . Current methods of transfer of young people with Type 1 diabetes to adult services. Diabet Med 2002;19:649–54. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryden KS, Dunger DB, Mayou RA, et al. . Poor prognosis of young adults with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1052–7. 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatr Nephrol 2000;14:469–72. 10.1007/s004670050794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somerville J. Management of adults with congenital heart disease: an increasing problem. Annu Rev Med 1997;48:283–93. 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomlinson P, Sugarman ID. Complications with shunts in adults with spina bifida. BMJ 1995;311:286–7. 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Your welcome. London: DH, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Transition getting it right for young people. London: DH, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Transition: moving on well. London: DH, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Physicians; Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics 2011;128:182–200. 10.1542/peds.2011-0969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. . Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570–6. 10.1016/1054-139X(93)90143-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duguépéroux I, Tamalet A, Sermet-Gaudelus I, et al. . Clinical changes of patients with cystic fibrosis during transition from pediatric to adult care. J Adolesc Health 2008;43:459–65. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, et al. . Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ 2012;344:e3718 10.1136/bmj.e3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prestidge C, Romann A, Djurdjev O, et al. . Utility and cost of a renal transplant transition clinic. Pediatr Nephrol 2012;27:295–302. 10.1007/s00467-011-1980-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw KL, Watanabe A, Rankin E, et al. . Walking the talk. Implementation of transitional care guidance in a UK paediatric and a neighbouring adult facility. Child Care Health Dev 2014;40:663–70. 10.1111/cch.12110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehouse S, Paone MC. “Patients in Transition: Bridging the healthcare gap from youth to adulthood”. Contemporary Paediatrics 1998;13:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paone MC, Wigle M, Saewyc E. The ON TRAC model for transitional care of adolescents. Prog Transplant 2006;16:291–302. 10.7182/prtr.16.4.6l055204763t62v7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonagh JE, Southwood TR, Shaw KL. Growing up and moving on in rheumatology: development and preliminary evaluation of a transitional care programme for a multicentre cohort of adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis J Child Health Care 2006;10:22–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Care Quality commission. From the pond into the sea: Children's transition to adult health services. June 2014.

- 19.Gosden C, Edge JA, Holt RI, et al. . The fifth UK paediatric diabetes services survey: meeting guidelines and recommendations? Arch Dis Child 2010;95:837–40. 10.1136/adc.2009.176925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gleeson H, Davis J, Jones J, et al. . The challenge of delivering endocrine care and successful transition to adult services in adolescents with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: experience in a single centre over 18 years. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78:23–8. 10.1111/cen.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonagh JE, Foster HE, Hall MA, et al. . Audit of rheumatology services for adolescents and young adults in the UK. British Paediatric Rheumatology Group. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:596–602. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.6.596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connell B, Bailey S, Pearce J. Straddling the pathway from paediatrician to mainstream health care: transition issues experienced in disability care. Aust J Rural Health 2003;11:57–63. 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2003.00465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingsnorth S, Gall C, Beayni S, et al. . Parents as transition experts? Qualitative findings from a pilot parent-led peer support group. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:833–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colver AF, Merrick H, Deverill M, et al. . Study protocol: Longitudinal study of the transition of young people with complex health needs from child to adult health services. BMC Public Health 2013;13:675 10.1186/1471-2458-13-675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw KL, Southwood TR, McDonagh JE. Young people's satisfaction of transitional care in adolescent rheumatology in the UK. Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:368–79. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2830. Huang JS, Terrones L, Tompane T, et al. Preparing adolescents with chronic disease for transition to adult care: a technology program. Pediatrics 2014;133:e1639–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]