Abstract

Objective To evaluate doctors’ coffee consumption at work and differences between specialties.

Design Single centre retrospective cohort study.

Setting Large teaching hospital in Switzerland.

Participants 766 qualified doctors (425 men, 341 women) from all medical specialties (201 internal medicine, 76 general surgery, 67 anaesthetics, 54 radiology, 48 orthopaedics, 43 gynaecology, 36 neurology, 23 neurosurgery, 96 other specialties).

Data source Staff purchasing history from staff canteens’ electronic payment system linked to separate anonymised personal data from the human resource database.

Main outcome measure Numbers of coffees purchased per person per year.

Results 84% (644) of doctors purchased coffee at one of the hospital canteens. 70 772 coffees were consumed by doctors in 2014. There was a significant association between specialty and yearly coffee purchasing (F=12.45; P<0.01). On average orthopaedic surgeons purchased the most coffee per person per year (mean 189, SD 136) followed by radiologists (177, SD 191) and general surgeons (167, SD 138). Anaesthetists purchased the least coffee (39, SD 48). Male doctors bought significantly more coffees per person per year (128 (SD 140) v 86 (SD 86), t=−4.66, P<0.01) and twice as many espressos as female doctors (mean 27 (SD 46) v 10 (SD 19), t=−6.54, P<0.01). Hierarchical position was associated with coffee purchasing (F=4.55; P=0.04). Senior consultants (>5 years’ experience) bought most coffees per person per year (140, SD 169) and junior doctors and registrars bought fewest (95, SD 85). Propensity of buying rounds also increased with hierarchical position (χ2=556.24; P<0.01), with heads of departments buying more rounds than junior doctors (30% v 15%).

Conclusions Doctors commonly use coffee as a stimulant. Substantial variation exists between specialties. Surgeons drink notably more coffee than physicians, with orthopaedic surgeons consuming the greatest amount in the communal cafeteria setting, though this might reflect social tendencies rather than caffeine dependency. Hierarchical position is positively correlated with coffee consumption and generosity with regard to buying rounds of coffee.

Introduction

The stimulating effect of caffeine has been known for a thousand years. Legend describes its discovery by herders in Ethiopia who observed the energising effects on their goats when they ate the berries of coffee plants.1 The first European to mention coffee was Leonhart Rauwolff, a German physician, in 1582 on his return from Mesopotamia in search of herbal remedies. In his book “Aigentliche Beschreibung der Raiß inn die Morgenländer” he described “A very good drink that is as black as ink and very good in illness, especially of the stomach.”2 The first coffee house was in Constantinople (1555), but rapid promotion of this “black medicine” followed throughout Europe in the 17th century in Venice, Hamburg, Vienna, Amsterdam, and Paris. Today coffee houses enjoy prominence of the high streets of every European city. Geneva was the first city in Switzerland to host a coffee house in the late 17th century as it was the main trading place for colonial goods at the time.3 Today’s Swiss coffee culture is built on an amalgam of Italian and French coffee tradition with regional differences.

The medical benefits of coffee are debatable. Detractors suggest that it increases blood pressure and hypertension, though recent meta-analyses concluded that evidence is weak and no recommendation for or against can be made.4 5 6 Others have described beneficial effects of regular coffee drinking such as reduced risk of diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, hepatic cirrhosis, rectal cancer, suicide, and cardiovascular disease,7 8 9 10 11 12 13 as well as an overall reduced mortality.14

The stimulating effect of caffeine is also well known, and doctors, who often work long hours, sometimes depend on the stimulation of coffee to perform at their best. Perhaps tellingly the “fatigue management strategy” of Queensland Health (Australia) suggests the “strategic use of caffeine” in tired and overworked doctors.15 They proposed 400 mg of caffeine per working day to stay awake in the job. This is a huge dose, equivalent to six cups of coffee. Although, to our knowledge, such strategies are not in place in Europe, daily caffeine boosts are the norm for many doctors.16 It is not known, however, whether different specialties are more or less dependent on coffee to get through the day.

Methods

We accessed data for coffee purchasing as a proxy measure of consumption at a large teaching hospital in Switzerland over one calendar year (2014). Precise information on type of coffee, time of sale, and number of products bought was recorded through the hospital’s electronic payment system, which is linked to the individual’s ID badge. This is the routine way staff pay for food and drink as the hospital offers a heavy staff discount of 45%. The cash register database contains ID serial numbers in isolation. We merged this database with another from human resources that holds information on profession, affiliation, medical specialty, position, sex, and age. Before release, data were filtered to include only medical doctors and anonymised.

Doctors were stratified by medical specialty, position, and sex. Specialties with few doctors and subspecialties were grouped (table 1). We grouped doctors by position: those in training (junior doctors and registrars), consultants, senior consultants (more than five years’ experience), and heads of departments.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospital doctors according to coffee consumption. Figures are numbers (percentage)

| Coffee drinkers (n=644) | Non-coffee drinkers (n=122) | Statistic | |

| Mean (SD; range) age (years) | 39 (9; 24-69) | 39 (10; 23-64) | t=0.27, P=0.78 |

| Men | 359 (56) | 66 (54) | P=0.77 |

| Women | 285 (44) | 56 (46) | |

| Position | |||

| Junior doctors and registrars | 288 (45) | 54 (44) | χ2=3.52, P=0.48 |

| Consultants | 150 (23) | 34 (28) | |

| Senior consultants | 140 (22) | 32 (26) | |

| Heads of department | 29 (5) | 2 (2) | |

| Other | 37 (6) | 6 (5) | |

| Specialty | |||

| General surgery | 76 (12) | 9 (7) | χ2=12.16, P=0.14 |

| Internal medicine | 201 (31) | 43 (35) | |

| Gynaecology | 43 (7) | 7 (6) | |

| Anaesthetics | 67 (10) | 14 (12) | |

| Neurology | 36 (6) | 4 (3) | |

| Neurosurgery | 23 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Radiology | 54 (8) | 7 (6) | |

| Orthopaedics | 48 (8) | 8 (7) | |

| Other | 96 (15) | 29 (24) | |

The hospital offers four cafeterias with social seating areas from which to purchase coffee (open from 6 15 am until 8 15 pm every day of the year). Data from 14 vending machines were not analysed.

We used χ2, Fisher’s exact, or t test as appropriate for statistical comparison of coffee versus non-coffee drinkers. For description of circadian consumption we present absolute numbers of coffees sold per hour aggregated across the year. Main analyses are numbers of coffees drunk per person per year. We used t tests and univariate analysis of variance (analysis of variance) to determine the influence of sex, hierarchical position, and specialty. Analysis also included frequency of buying rounds of coffees, identified as purchases of more than one coffee at a time. These are reported as a percentage of an individual’s total purchases. To allow ranking of individual groups we provide 95% confidence intervals for means and frequencies.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in the design and implementation of the study. There are no plans to involve patients in dissemination.

Results

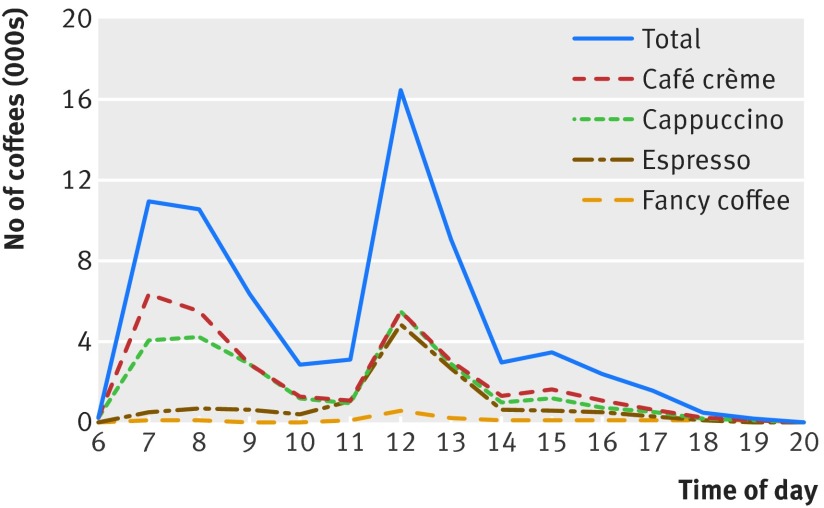

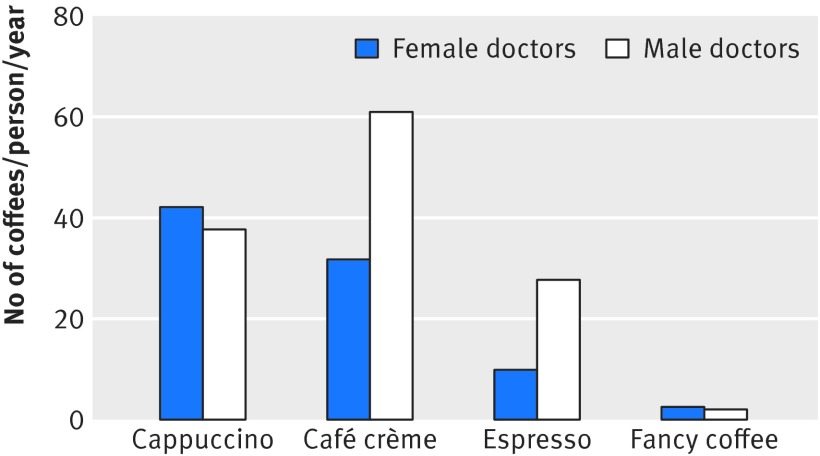

Over 84% (644/766) of doctors purchased at least one coffee during the study period. A total of 70 772 coffees were sold to doctors across the cafeterias. Daily consumption peaked on Friday 19 December at 371. There were distinct peaks in the timing of self caffeination and specific consumer patterns with regard to coffee type. Café crème was most popular in the mornings, whereas espresso was predominantly savoured after lunch (fig 1). Table 2 and figure 2 show the distribution of consumption of different types of coffee by sex.

Fig 1 Yearly number of coffees consumed in 2014 in total and per type of coffee as function of time of day (total n=70 772). Sold coffees are grouped per hour

Table 2.

Coffees sold per person per year per type of coffee by sex. Figures are means (95% CI; SD)

| Coffee type | Female doctors | Male doctors | t test, P value |

| Cappuccino | 42 (35 to 49; 62) | 38 (32 to 44; 60) | 0.93, P=0.36 |

| Café crème* | 32 (27 to 36; 44) | 61 (50 to 72; 104) | −4.81, P<0.01 |

| Espresso | 10 (8 to 12; 20) | 28 (23 to 32; 46) | −6.54, P<0.01 |

| Fancy coffee† | 3 (2 to 4; 8) | 2 (1 to 3; 7) | 0.82, P=0.41 |

| Total | 87 (76 to 97; 87) | 129 (114 to 143; 140) | −4.66, P<0.01 |

*Swiss type “caffè lungo.”

†Includes flavoured coffees, iced coffees, and weekly specials.

Fig 2 Mean number of coffees sold per person per year per coffee type as function of sex

Table 3 shows that medical specialty was significantly associated with the number of coffees drunk per year (F=12.455; P<0.001). Orthopaedic surgeons drank most coffee per person per year (mean 189.4, SD 136.4), followed by radiologists (176.5, SD 191.1) and general surgeons (166.7, SD 137.9). Anaesthetists were comparatively rarely seen in the cafeteria, drinking only 38.8 coffees on average (SD 48.2) per person per year.

Table 3.

Yearly coffee consumption by specialty per person

| Specialty | Mean (95% CI; SD) |

| Orthopaedics | 189 (151 to 228; 136) |

| Radiology | 177 (126 to 228; 191) |

| General surgery | 167 (136 to 198; 138) |

| Neurosurgery | 116 (79 to 153; 90) |

| Neurology | 104 (75 to 133; 89) |

| Internal medicine | 90 (77 to 103; 95) |

| Gynaecology | 75 (43 to 106; 106) |

| Anaesthetics | 39 (27 to 50; 48) |

| Other | 95 (74 to 116; 105) |

Coffee consumption was also related to position, with a positive association between intake and hierarchy (F=4.546; P=0.004). Senior consultants consumed on average 45 coffees more per year than junior doctors and registrars (table 4). The propensity for buying rounds increased with hierarchical position (χ2=556.24; P<0.001). Although heads of departments drank less coffee than senior consultants, they paid for rounds more often, buying a round with nearly every third coffee they drank in cafeterias (table 4).

Table 4.

Association between coffee consumption and hierarchical position (coffee rounds bought by individuals are given as percentages of individual coffee consumption)

| Position | Mean (95% CI; SD) No of coffees per person per year | Frequency (95% CI) of rounds* |

| Junior doctors and registrars | 96 (86 to 105.5; 86) | 14.8% (11 to 19%) |

| Consultants | 108 (88 to 127.1; 121) | 16.2% (10 to 22%) |

| Senior consultants | 141 (113 to 168.7; 170) | 21.8% (15 to 29%) |

| Heads of departments | 117 (84 to 149.6; 90) | 29.7% (13 to 46%) |

*No of coffees bought in rounds of at least two coffees as a percentage of overall purchases per person.

Discussion

In this detailed analysis of doctors’ coffee purchasing habits at work over a 12 month period in a large teaching hospital in Switzerland we found variation between specialties, hierarchy, and sex. The sex difference found with regard to absolute coffee consumption and the differing preferences for coffee style was in line with general population data.17 The large coffee companies are certainly aware of differences in attitude to coffee between men and women; typical advertisements exploit sex role issues, with men enjoying a decent espresso (what else?) and women chatting with friends on a sofa over a cappuccino. Tifferet and colleagues investigated consumer behaviour in 1053 medical students and reported that men were more attracted to branded coffee (85%) than women (64%); suggesting that advertising affects young doctors as it does in the wider population, promoting certain coffee drinking behaviours.18

A pleasing result is the finding that hierarchical position is positively correlated with generosity at the caffeine refuelling stations (table 4). The reasons why senior doctors consumed more coffee than their younger colleagues can only be speculated on. Increased coffee intake might help fight age and fatigue to keep up with the younger workforce, though another popular opinion (repeatedly expressed to the authors during daily qualitative groundwork for this study) is that senior doctors have more time to socialise and network. The study design did not allow tracking of who actually drank the coffees paid for as a round; we assume that the coffees bought by senior doctors were often for junior staff. Our analysis might therefore overestimate the mean coffee consumption among higher positions.

Who drinks the most coffee?

Within this study, we also tried to settle the debate as to whether surgeons, radiologists, or physicians drink more coffee. We believe we have finally clarified this important question, unresolved for so many years. It is in fact the orthopaedic surgeons who drink the most black medicine. This suggests either that their “work hard/play hard/drink hard” persona extends to hospital canteens, highlighting their productivity, or that they have too much time to kill and can be found hanging out in cafeterias. Radiologists are also frequently found in the cafeterias, perhaps to escape their dark working environment. Their demanding job that puts them in front of computer screens in dimmed light can be tiring after short periods. Regular caffeine boosts could revitalise the spirit and improve performance. The relatively low coffee consumption of our colleagues from anaesthetics warrants further attempts at explanation. Anaesthetists might be too busy to find their way to the coffee outlets, though a more likely explanation for their rare sociable appearances is that they have set up their own coffee machines in the theatre suites. Whether this belies a social issue cannot be answered with these data. General surgeons and orthopaedic surgeons also seek additional caffeine boosts in the theatre area, though this does not seem to impair their purchasing habits in the more sociable canteens in the same way.

Strengths and weaknesses

A notable strength of this study is the detailed analysis of a comprehensive dataset of all doctors’ coffee purchasing through the hospital over a 12 month period, which can be directly linked to specialty and demographics. There are also, however, several limitations. We could analyse data only on coffees purchased between 6 15 am and 8 15 pm at the hospital canteens and cannot comment on night time consumption. There is a dark spectre of other coffee sources in operating suites and from personal coffee machines, hidden in doctors’ offices. Heads of departments generally have their own coffee machines and indeed secretaries who assist in the preparation of the black medicine. A wider source of potential bias is that coffee aficionados might have their first cup at home and come to work pre-caffeinated. As noted in the methods, we excluded cheap instant coffee from vending machines from this analysis. Although these beverages do contain caffeine we believe this brew does not merit the name coffee. As such, it is likely we have substantially underestimated overall caffeine intake across the board. The hospital canteen is a central part of our local coffee culture—we do not have staff rooms at our institution and instead congregate in the sociable meeting places, typically over coffee. A generous staff discount is awarded to coffee purchases and is thus the dominant method by which staff members purchase coffee at work. As this study was set in a single Swiss institution, findings might not be fully transferable to other settings.

Despite the limitations and underestimation of doctors’ overall coffee consumption at work, our study sheds light on a previously neglected topic and gives a representative overview on doctors’ coffee drinking patterns.

What is already known on this topic

Coffee is known to be a widely used stimulant, particularly among doctors

The health benefits of coffee consumption might outweigh the possible health risks

What this study adds

Different medical specialties have different coffee purchasing habits

More senior doctors purchase more coffee than junior doctors

Of all specialties, orthopaedic surgeons drink the most coffee at work

We thank Daniel Germann (hospital director) for his support of this project and Hubert Giesinger for his expertise on the cultural and historical background of coffee. We also thank the wonderful cafeteria staff for lovingly preparing our black medicine every day.

Contributors: KG and JMG conceived the study. KG, JMG, and DFH drafted the manuscript. JMG performed the statistical analysis. KG, JMG, DFH, ME, and BJ interpreted the results and finalised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. KG is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: As the study did not involve patients, we sought permission from hospital management and the data protection officer to release anonymised data used in this study.

Transparency statement: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Weinberg BA. The world of caffeine: The science and culture of the world’s most popular drug. Routledge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray J, Willoughby F, Rauwolf L. Travels through the Low-Countries, Germany, Italy and France, with curious observations, natural, topographical, moral, physiological. 1738.

- 3.Rossfeld R. Genuss und Nüchternheit: Geschichte des Kaffees in der Schweiz vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart. hier und jetzt, 2002.

- 4.Steffen M, Kuhle C, Hensrud D, Erwin PJ, Murad MH. The effect of coffee consumption on blood pressure and the development of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 2012;30: 2245-54. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283588d73 23032138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesas AE, Leon-Muñoz LM, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E. The effect of coffee on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94: 1113-26. 21880846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-Garcia E, Guallar-Castillon P, Leon-Muñoz L, Graciani A, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Coffee consumption and health-related quality of life. Clin Nutr 2014;33: 143-9.. 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.004 23622779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A. Coffee, caffeine, and coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 2007;18: 13-9. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3280127b04 17218826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palacios N, Gao X, McCullough MLet al. Caffeine and risk of Parkinson’s disease in a large cohort of men and women. Mov Disord 2012;27: 1276-82. 10.1002/mds.25076 22927157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovannucci E. Meta-analysis of coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147: 1043-52. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009398 9620048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Coffee and tea consumption are associated with a lower incidence of chronic liver disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2005;129: 1928-36.. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.056 16344061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen LF, Jacobs DR, Carlsen MH, Blomhoff R. Consumption of coffee is associated with reduced risk of death attributed to inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases in the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83: 1039-46. 16685044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iso H, Date C, Wakai K, Fukui M, Tamakoshi AJACC Study Group. The relationship between green tea and total caffeine intake and risk for self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese adults. Ann Intern Med 2006;144: 554-62. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00005 16618952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas M, O’Reilly EJ, Pan Aet al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of completed suicide: results from three prospective cohorts of American adults. World J Biol Psychiatry 2014;15: 377-86. 10.3109/15622975.2013.795243 23819683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crippa A, Discacciati A, Larsson SC, Wolk A, Orsini N. Coffee consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180: 763-75. 10.1093/aje/kwu194 25156996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Queensland Government QH. Queensland health fatigue risk management system resource pack. http://enhancingresponsibility.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Queensland-Health-Fatigue-Risk-Management-System-resource-pack-2009.pdf

- 16.CareerBuilder. CareerBuilder and Dunkin’ Donuts survey finds which professions need coffee the most. http://goo.gl/HBx8M3.

- 17.Demura S, Aoki H, Mizusawa Tet al. Gender differences in coffee consumption and its effects in young people. Food Nutr Sci 2013;4: 748-57. 10.4236/fns.2013.47096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tifferet S, Shani N, Cohen H. Gender differences in the status consumption of coffee. Hum Ethol Bull 2013;28: 5-9. [Google Scholar]