Abstract

There are a variety of medical conditions associated with chronic sinonasal inflammation including chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and cystic fibrosis. CRS in particular can be divided into two major subgroups based upon whether nasal polyps are present (CRSwNP) or absent (CRSsNP). Unfortunately, clinical treatment strategies for patients with chronic sinonasal inflammation are limited, in part because the underlying mechanisms contributing to disease pathology are heterogeneous and not entirely known. It is hypothesized that alterations in mucociliary clearance, abnormalities in the sinonasal epithelial cell barrier and tissue remodeling all contribute to the chronic inflammatory and tissue deforming processes characteristic of CRS. Additionally, the host innate and adaptive immune responses are also significantly activated and may be involved in pathogenesis. Recent advancements in the understanding of CRS pathogenesis are highlighted in this review with special focus placed on the roles of epithelial cells and the host immune response in cystic fibrosis, CRSsNP and CRSwNP.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis, Nasal Polyps, Mucociliary Clearance, Epithelial Cells, Inflammation, Microbiome

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is characterized by chronic inflammation of the sinonasal mucosa and is clinically associated with sinus pressure, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and a decreased sense of smell persisting for greater than 12 weeks1. CRS can be subdivided into 2 major categories based upon whether nasal polyps are present (CRSwNP) or absent (CRSsNP)2. While CRS is estimated to affect over 10 million patients in the US and lead to $22 billion in total annual costs1, 3, there are other diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, that also involve chronic sinonasal inflammation and nasal polyp formation that have important clinical implications. In order to advance the current diagnostic and treatment strategies available for affected patients, a better understanding of CRS pathogenesis is needed.

The Sinonasal Microbiome

Much like the gut, the sinonasal cavity has a resident flora that maintains an environment conducive to respiratory health. Substantial effort has recently been made using culture independent techniques, i.e. molecular diagnostics, to attempt to understand and define the microbial community or microbiome of the human sinonasal cavity in the healthy and diseased (CRS) states4–10. No consistent patterns have emerged in the diseased state to implicate specific organism(s) as causative, but data suggest an imbalance, or dysbiosis, is found in CRS, with a decrease in microbial diversity. Another concept that has emerged is that the correct balance of microbes within the local microbiome may be immunomodulatory and that an imbalance shifts an important regulator of local inflammation11. Puzzles that remain include the existence of similar microbial species in both healthy and CRS patients, albeit in different abundances8, the fact that traditional pathogenic microbes e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Enterobacter species are also found in healthy cavities, albeit at lower abundances8, as well as how innate and adaptive immune mechanisms (described below) can discriminate between bacterial species to help set the nasal microbiome.

Mucociliary Clearance—The Foundation of Sinonasal Innate Immunity

The upper airways play an important role in removing particulates and pathogens from inspired air via mucociliary clearance (MCC)12, a specialized function unique to the airway epithelium. MCC is the primary physical defense of the respiratory tract, complimenting the physical epithelial barrier (Figure 1). MCC relies upon both mucus production and transport. The airway surface liquid (ASL) lining the respiratory tract consists of two layers. The top is an antimicrobial-rich mucus “gel,” formed by mucins produced by goblet cells and submucosal glands13. Mucins are large thread-like glycoproteins14 with “sticky” carbohydrate side chains15 that can bind surface adhesins on microorganisms15, including Mycoplasma pneumonia16, Haemophilus influenza17, Moraxella catarrhalis18, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa19 and cepacia20. The mucus layer rests on top of a less-viscous fluid periciliary layer (PCL) that surrounds the cilia of airway epithelial cells and allows them to beat rapidly (~8–15 Hz). Membrane-tethered mucins on the apical membrane of ciliated cells may form a “lubricating” brush-like structure that keeps the mucus and PLC layers separate to facilitate MCC21. Coordinated and directional ciliary beating (known as the “metachronal wave”22) facilitates transport of debris-laden mucus through the sinonasal cavity to the oropharynx, where it is swallowed or expectorated.

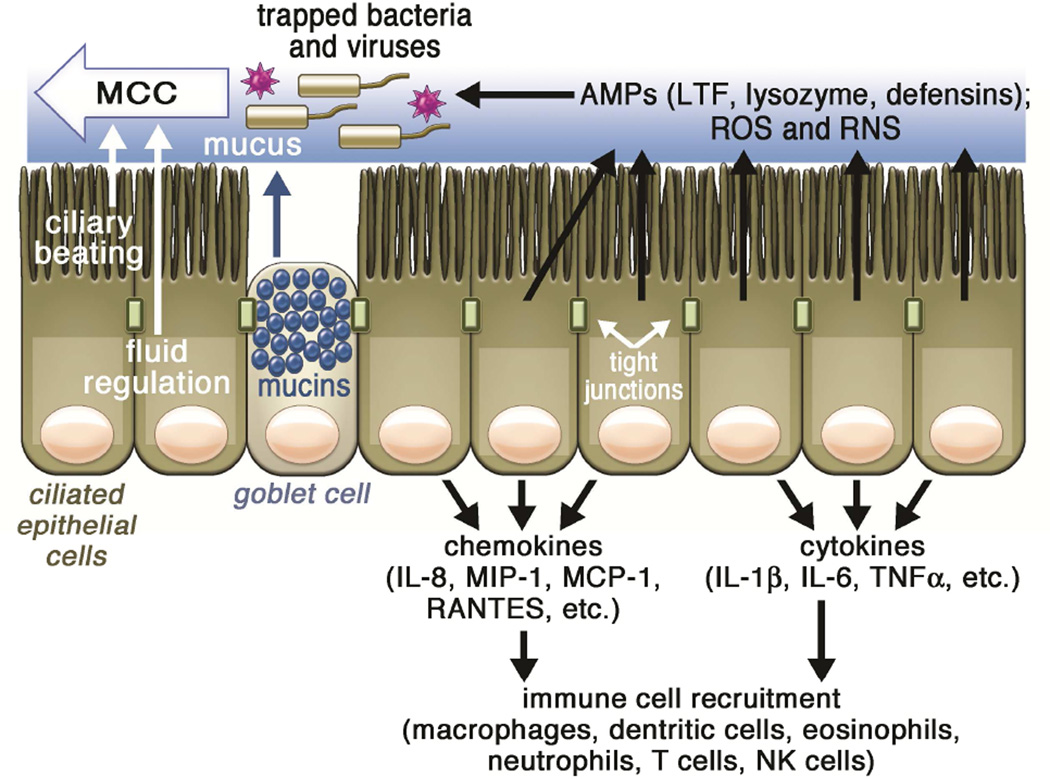

Figure 1. Overview of sinonasal innate immunity.

In healthy tissue, respiratory epithelial cells are linked by tight junctions to form a protective physical barrier. Inhaled pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, and fungal spores, are trapped by airway mucus and then removed by mucociliary clearance. Constant beating of cilia drives the pathogen-laden mucus toward the oropharynx, where it is then cleared out of the airway by expectoration or swallowing. Mucociliary clearance is further regulated by secretion of mucus as well as ion and fluid transport, which controls the mucus viscosity. Mucociliary transport is complemented by the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS, respectively) and the production of antimicrobial peptides. During more chronic exposure to pathogens, epithelial cells secrete cytokines to activate inflammatory pathways and recruit dedicated immune cells.

Abbreviations: AMP, antimicrobial peptide; LTF, lactotransferrin; IL, interleukin; MCC, mucociliary clearance; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein 1; MIP-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1; RANTES, Regulated on Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted protein; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species, TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha;

MCC is regulated by small molecule neurotransmitter (e.g., adenosine trisphosphate, acetylcholine, etc.) and neuropeptide (vasoactive intestinal peptide, substance P, etc.) receptors that regulate mucus and fluid secretion23 and ciliary beating24, as well as receptors for bacterial products25 and mechanical stresses26. While other mechanisms defend the airway in addition to MCC (described below), the importance of MCC is illustrated by direct links between MCC defects and disease. In cystic fibrosis (CF), defects in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) anion channel result in impaired salt and water secretion23 as well as possibly enhanced absorption27, creating dehydrated mucus and impaired MCC. CF patients frequently develop severe recurrent sinonasal infections28 that may also seed or exacerbate lung infections. Additionally, the epithelial anion transporter, pendrin, is elevated in nasal polyps compared with uncinate tissue (UT) isolated from healthy controls29, 30. Upregulated pendrin expression in the airway has been linked to IL-4, IL-13, and IL-17A31–33. However, further studies are needed to investigate how pendrin contributes to MCC, epithelial dysfunction, and CRSwNP pathogenesis. Increased mucus production may also impair MCC. In CRSwNP, Muc5AC was found to be elevated in nasal polyps when compared with UT from CRSsNP or healthy patients29.

Defects involving epithelial cell cilia can also impact MCC and contribute to chronic sinonasal inflammation. For example, in primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), abnormal ciliary function and/or structure result in impaired MCC and increased incidences of upper respiratory infections34. More commonly, though, acquired ciliary dysfunction occurs through exposure to environmental or microbial toxins and/or as a secondary consequence of disease through exposure to inflammatory stimuli35. Nonetheless, this likely contributes to pathogenesis of upper respiratory infections. Several pathogens produce compounds that impair ciliary motion and/or coordination, including Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Aspergillus fumagatus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa36–39. Hypoxia created by mucostasis or anatomical obstruction may also affect MCC by inhibiting ion transport40 or promoting polypogenesis41. Approaches designed to increase ciliary beating or enhance fluid secretion to thin mucus remain attractive therapeutic strategies for enhancing MCC in CRS with impaired MCC. Additionally, high volume low pressure sinonasal lavage has been demonstrated to be effective in mobilizing the copious secretions associated with CRS42.

Epithelial-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides and Radicals

In addition to transporting mucus, sinonasal epithelial cells produce substances that have direct anti-pathogen effects43, 44 (Figure 1). These include well-characterized proteins, such as lysozyme, lactoferrin, antitrypsin, defensins, S100 proteins and surfactants. Some are tonically secreted, but the expression of many are up-regulated during infection45. Moreover, after epithelial damage, concentrations of these proteins may increase further due to plasma extravasation46.

Lysozyme is a small cationic protein secreted submucosal glands47. Lysozyme catalyzes the breakdown of the β-1,4-glycosidic bonds between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine in the outer bacterial cell wall. Additionally, binding of lysozyme to bacterial cell walls facilitates phagocytosis by macrophages45. Lysozyme is most effective against gram-positive bacteria, but also has effects against gram-negative bacteria48, 49 and fungi50. Various studies have examined lysozyme in CRS. However, controversy exists over whether levels are increased51 or decreased52, 53 in CRS. Lysozyme is produced by submucosal glands, which are diminished in nasal polyp tissue, thus lysozyme decrease in polyp tissue may contribute to the variability of reported results54.

Lactoferrin (also known as lactotransferrin) chelates and sequesters iron important for bacterial and fungal metabolism45. Bacteria may also use iron to catalyze mucin degradation to help break through the protective mucosal barrier, a process likely inhibited by lactoferrin55. Lactoferrin also binds certain conserved microbial structures known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from the gram-negative cell wall and unmethylated bacterial CpG containing DNA. Lactoferrin may act as an anti-inflammatory by inhibiting binding of these molecules to pro-inflammatory receptors56. However, the immune regulatory role of lactoferrin is complex, as lactoferrin may also act alone or as a “partner molecule” with PAMPs to promote activation of pattern recognition receptors on immune cells56. Lactoferrin binding to LPS can also cause gram-negative bacterial permeabilization56. Lactoferrin inhibits entry of RNA and DNA viruses into host cells by binding host viral receptors or the viruses themselves57. Lactoferrin levels may be reduced in CRS, especially in those patients with bacterial biofilms58.

Collectin (collagen-lectin) proteins, such as surfactant proteins (SP-A and SP-D), C-reactive protein, and mannose-binding lectin, interact with numerous airway bacteria and can activate complement and exhibit antimicrobial properties59. Collectins recognize and bind to PAMPs, including LPS, via their calcium-dependent carbohydrate-binding domains, promoting bacterial clearance59. LL-37 is produced by the human nasal mucosa60, 61 by kallikrein and other proteases from a precursor molecule, cathelicidin. LL-37 activation is regulated by SPINK5 and other protease inhibitors expressed in the epithelium62. LL-37 has broad antibacterial properties, and may even have effects against Pseudomonas biofilms in animal models of CRS63. LL-37 may be anti-inflammatory by neutralizing LPS64. Of note, the transcription of the LL-37 gene is induced by binding of the bioactive form of vitamin D to its receptor65. Sinonasal epithelial cells express the 1-α-hydroxylase enzyme important for synthesis of bioactive vitamin D; when sinonasal epithelial cells are exposed to inactive vitamin D precursors, they synthesize bioactive vitamin D and increase LL-37 production66. Vitamin D may thus contribute to airway innate immunity67, including in CRS and allergic rhinitis68, 69.

Members of the α-defensin and β-defensin families are also expressed in the sinonasal epithelium70, 71. Defensins are up-regulated in response to bacterial or viral challenge72, 73. Defensins have broad antimicrobial effects against both bacteria and fungi, likely through formation of pores in bacterial and fungal membranes. β-defensins 2 and 3 have been shown to directly bind viruses to inhibit their entry into host cells as well as activate cytokine production to alert immune cells74, 75. Notably, the function of cationic defensins is inhibited under high ionic strength conditions76, suggesting that abnormalities in ion transport, as in CF, may reduce defensin function through alteration of ASL electrolyte concentration77.

Other antimicrobial peptides may have important roles in CRSwNP. Members of the palate, lung, and nasal epithelial clone (PLUNC) family, including SPLUNC-1, have antimicrobial and surfactant properties but were decreased in nasal polyps compared with healthy sinonasal tissue54. In addition to having antimicrobial properties, SPLUNC-1 affects ASL volume by inhibiting activation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC)78. ENaC mediates sodium and fluid absorption in airway epithelia. Thus, reductions of SPLUNC-1 could have detrimental effects on MCC. Additionally, epithelial defense proteins S100A7 (psoriasin) and S100A8/9 (calprotectin) are reduced in CRSwNP79. While antimicrobial protein levels differ between healthy and diseased sinonasal tissue, levels also can vary by location within the sinonasal cavity80. For example, lactoferrin is higher in healthy UT compared with healthy inferior turbinate, while S100A7 is higher in inferior turbinate compared with UT80. Taken together, regional variability suggests that the sinonasal cavity is not uniform, but rather has complex and unique roles dependent upon specific anatomic location.

The lipids cholesteryl linoleate and cholesteryl arachidonate may contribute to antimicrobial properties of nasal secretions81, and their levels may be increased in CRS nasal secretions82. The sinonasal mucosa also generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can directly damage bacteria. Lactoperoxidase (LPO;83) catalyzes the oxidation of substrates by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Airway epithelial ciliated cells produce H2O2 through the action of NADPH oxidase isoforms, including DUOX1 and DUOX284. A potentially important substrate for the LPO/ H2O2 system is thiocyanate. Thiocyanate is oxidized via LPO to hypothiocyanite, a compound with antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral effects85. Both CFTR and pendrin may regulate thiocyanate transport, linking ion transport with host defense86. CFTR defects that reduce thiocyanate secretions may impair airway innate defense mechanisms in CF87. Pendrin elevation in CRS may also influence thiocyanate transport29.

The generation of nitric oxide (NO) by the sinonasal epithelium is thought to be critical for airway innate immunity, with the major source being the paranasal sinuses88. NO is generated by NO synthase (NOS). NOS isoforms vary in their mRNA inducibility as well their sensitivity to intracellular calcium. NOS isoforms are expressed in the cilia and microvilli of epithelial cells89, with the maxillary sinus being a site of high expression90. NO activates guanylyl cyclase to increase ciliary beating via cyclic-GMP and protein kinase G. NO and reactive derivatives such as peroxynitrite91 also directly damage bacterial proteins and DNA92, 93 and inhibit viral replication75. While studies have linked increased NO with host defense in vivo, others have suggested elevated NO is detrimental94. The wide range of NO measurement methods and heterogenous study populations have limited the conclusions that can be drawn from studies investigating NO as a diagnostic, prognostic, or efficacy indicator in sinonasal disease94.

Regulation of Antimicrobial Compound Production and Secretion

The most well-studied pathway for regulation of antimicrobial compounds by sinonasal epithelial cells is through toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize microbial PAMPs45 (Figure 2A). Sinonasal cells express ~10 TLRs, with expression changes observed in CRS95. TLRs stimulate the direct transcription and/or translation of mucins and AMPs45, 96. TLR responses occur over the course of hours, likely critically important during times of sustained colonization or infection. TLRs activate airway epithelial cells to secrete defense molecules as well as cytokines and chemokines that recruit dedicated immune cells and activate inflammation, which may play an important role in CRS pathogenesis. Epithelial cells from CRS patients produce less IL-8 in response to TLR2 ligands, which may impair immunity. TLRs also play an important role in detection of rhinoviruses, RSV, and influenza, and can stimulate induction of type I interferon75.

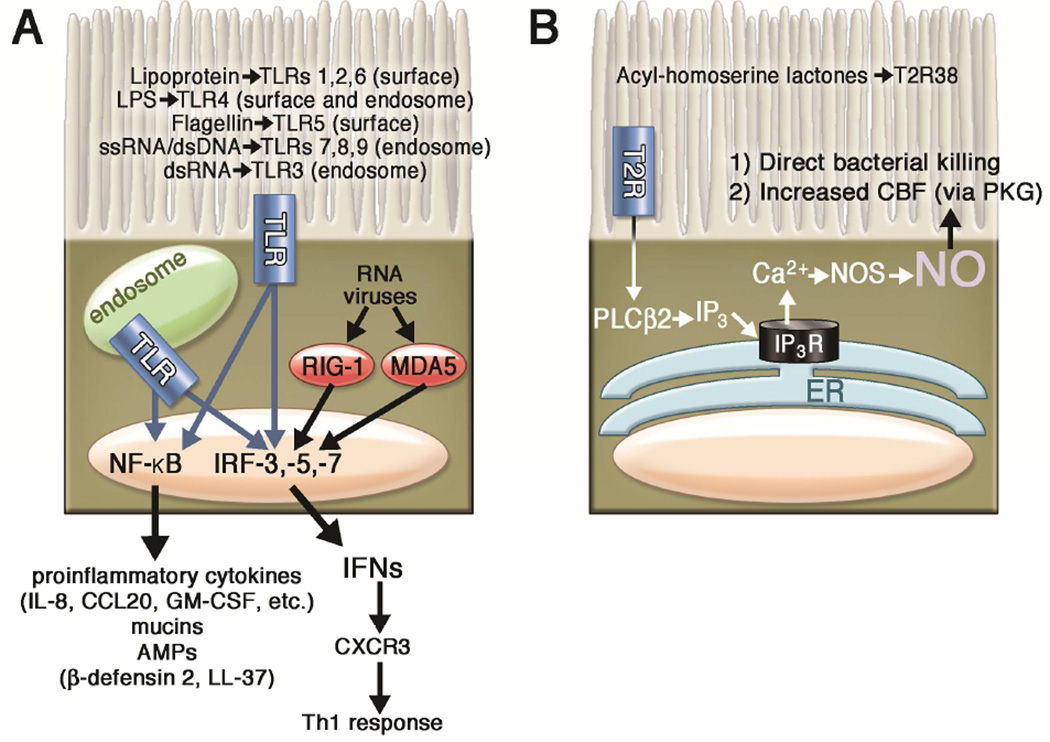

Figure 2. Role of toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) as well as taste family type 2 receptors (T2Rs) in regulation of sinonasal innate immunity by ciliated epithelial cells.

(A) TLRs located both on the cell surface and in intracellular endosomes of epithelial cells recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and stimulate innate immune responses. PAMPs recognized by specific TLRs are indicated in the figure. TLRs activate downstream intracellular signaling proteins MyD88, TIRAP, TRAM, and TRIF (not shown), which activate transcription factors such as CREB (not shown), NFκB, and interferon response factors (IRFs) that activate transcription of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), cytokines, and chemokines. The secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and interferons links innate and adaptive immunity. Additionally, the cytoplasmic helicases RIG-1 and MDA5 recognize RNA viruses by detecting intracellular viral double-stranded (ds) RNA, including viral genomic RNA (vRNA) (B) T2R38 expressed in ciliated epithelial cells recognizes bacterial homoserine lactones to stimulate calcium-dependent nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activation and NO production. This NO diffuses into the ASL and has direct antibacterial effects. NO also acts as an intracellular signaling molecule to stimulate ciliary beat frequency through protein kinase G (PKG).

Abbreviations: AMP, antimicrobial peptide, CCL20, Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20; CXCR3, Chemokine (C-X-C Motif) Receptor 3; ER, endoplasmic reticulum, GM-CSF, Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate receptor; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; MDA-5, Melanoma Differentiation-Associated protein 5; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; PLCβ2, phospholipase C isoform β2; RIG-1, retinoic acid-inducible gene 1; Th1, T helper cell 1; TLR, toll-like receptor;

Human ciliated epithelial cells also express T2R bitter taste receptors, originally identified on the tongue. At least one T2R, T2R38, is expressed in ciliated epithelial cells, detects bitter acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing molecules secreted by gram-negative bacteria and stimulates an increase in mucociliary clearance and production of bactericidal levels of nitric oxide25 (Figure 2B). T2R38 function has also been linked to antibacterial immune responses in vitro25 as well as gram-negative upper respiratory infection25 and chronic rhinosinusitis susceptibility in vivo97–101. Bitter taste receptors are also expressed in specialized epithelial cells termed solitary chemosensory cells (SCCs), a specialized cell type that stimulates the rapid release of stored AMPs from surrounding cells96, 102. Because of the rapid innate immune responses observed during stimulation of bitter taste receptors in the airway, it appears that they constitute an “early-warning” arm of the sinonasal innate immune system. T2Rs SCCs are also regulated by T1R sweet taste receptors (reviewed in103, 104), a mechanism which may be important in diabetics and CRS patients, both of which have elevated glucose in their ASL105–107. Taste receptors are emerging as a “front line” defense mechanism against microbial invaders, and there are exceedingly common functional polymorphisms found in all the taste receptor genes108. Thus, each individual’s “bitterome,” or collection of T2R polymorphisms, may define the permitted and excluded microbes, thus shaping each person’s baseline microbiota.

Epithelial Cell Barrier in Host Defense

In addition to secreting anti-microbial products, epithelial cells lining the sinonasal mucosa are involved in other aspects of host defense. Epithelial cells form a physical barrier involving tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes that protect the underlying sinonasal tissue from damage caused by inhaled pathogens, allergens, and other irritants. However, in CRS, studies have suggested that this barrier is compromised. Reductions in tight junction proteins, occludin-1 and zonula occludens 1, were observed in CRSwNP compared to healthy controls and this was associated with decreased epithelial electrical resistance109. Other markers of epithelial cell dysfunction commonly observed in CRS include abnormal ion transport as mentioned previously, goblet cell hyperplasia, basal cell proliferation, acanthosis and acantholysis.

There remains some debate as to whether epithelial cells in CRS are inherently dysfunctional or if exposures to external or internal factors induce this dysregulation. In support of the former argument, ex-vivo cultures of epithelial cells taken from patients with CRSwNP showed reduced electrical resistance when compared to healthy sinonasal tissue109. This is in contrast to another recent study that found no difference in electrical resistance in epithelial cells cultured from patients with CRSwNP, CRSsNP, or healthy controls110. Interestingly, in this latter study, Oncostatin M, a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines, was elevated in nasal polyps compared to healthy controls and could induce tissue permeability, disrupt tight junctions, and decrease electrical resistance in cultured human epithelial cells110. It will be important to resolve whether there are epithelial cell intrinsic defects in barrier and whether elevated levels of Oncostatin M and other inducers of the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) in CRSwNP contribute to epithelial barrier dysfunction. It should be noted that loss of epithelial barrier has been reported in asthma and atopic dermatitis as well, and both epithelial cell intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms have been discovered (e.g. filaggrin mutations and type-2 cytokine mediated changes).

Finally, pathogens are another possible external factor that could directly impact the sinonasal epithelial cell barrier. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was shown to transiently disrupt the tight junction proteins occludin and claudin-1 in cultured human nasal epithelial cells111. Additionally, Staphylococcus aureus as well as various fungi have been found to secrete products that could also disrupt zona occludens-1 in human nasal epithelial cells in vitro112. In some cases, the microbes produce proteases that can either cleave the junctional proteins or activate epithelial changes through protease activated receptors such as PAR2113, 114. It is possible that the pathogen-induced disruption of the sinonasal epithelium could promote further bacterial infection, colonization, or even biofilm formation and in turn further potentiate the overall chronic disease process.

The Host Immune Response: Inflammatory Mediators

The host immune system is also thought to play a prominent role in CRS pathogenesis. The effector functions of innate and adaptive immune cells as well as the various mediators they produce can all contribute to the chronic inflammatory environment characteristic of CRS (Figure 3). To this end, the type of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines identified within the sinonasal mucosa has historically been used to help define particular subsets of CRS. For example, cystic fibrosis has classically been characterized by a type-1 inflammatory response with elevated levels of interferon (IFN)-γ in the sinonasal tissue compared to healthy controls115, 116.

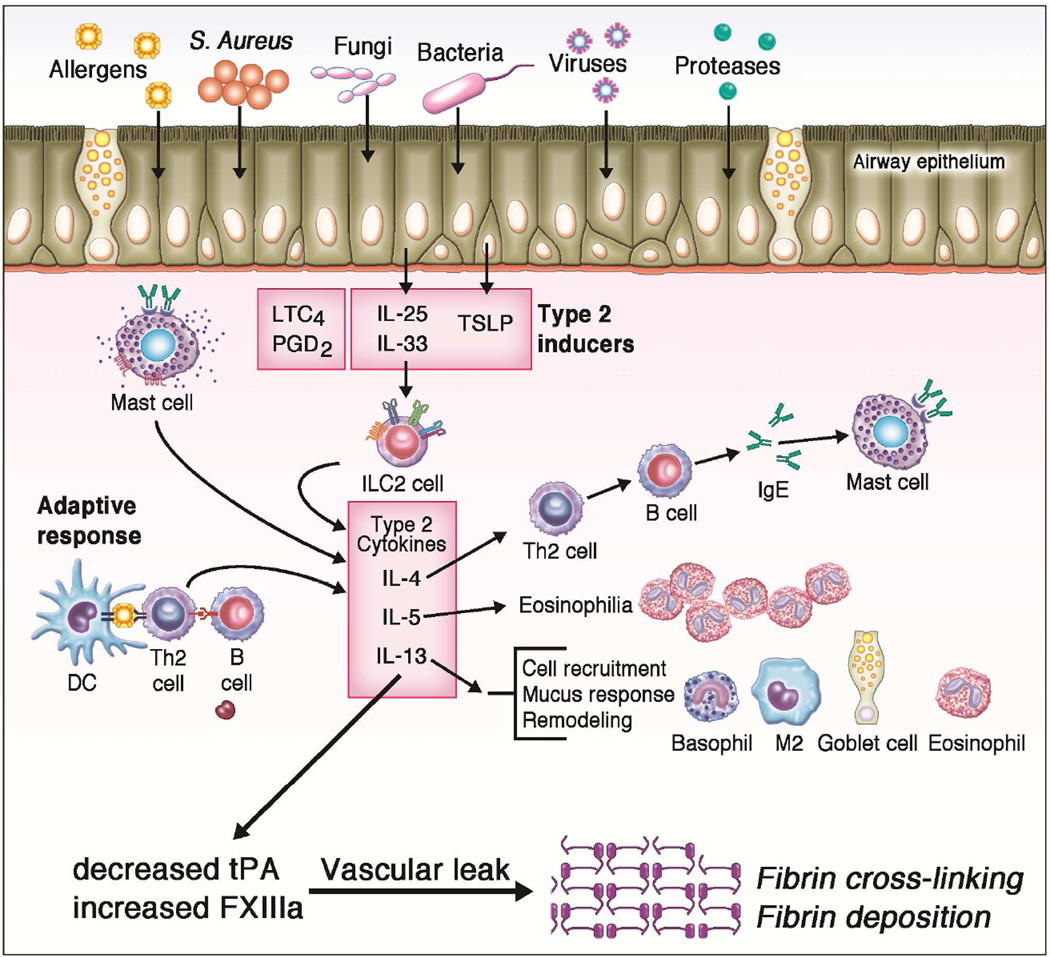

Figure 3. Role of the Host Immune Response in CRSwNP.

The dysregulated epithelial barrier in CRS can lead to enhanced exposures to various inhaled allergens, bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Additionally, colonization with Staphylococcus aureus may also occur. In CRSwNP nasal polyps, epithelial cells can release various inflammatory mediators, most notably thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), which in turn promote the development of a type-2 immune response. Innate immune cells including innate type-2 lymphoid cells (ILC2), mast cells, and eosinophils are all elevated in nasal polyps. These cells can release type-2 cytokines that further perpetuate the ongoing inflammatory response as well as specific granule proteins that can contribute to tissue injury. Adaptive immune cells including both naive B cells and activated plasma cells are also elevated in nasal polyps and contribute to increased local production of antibodies within the sinonasal tissue. Finally, type-2 cytokines are also thought to contribute to decreased t-PA and increased FXIIIa which, in the setting of increased vascular leak, lead to increased fibrin deposition and cross-linking within nasal polyps.

In contrast, CRSwNP, one of the most extensively studied CRS subtypes, is typically regarded as having a type-2 inflammatory environment, at least in the US and Europe (see below). Type-2 inflammation refers to a response typically driven by the type-2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. Such inflammation typically is characterized by infiltration of large numbers of eosinophils, basophils and mast cells. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cell-derived cytokine that plays an important role in promoting type-2 responses, is elevated and has enhanced activity in nasal polyps of CRSwNP when compared to healthy sinonasal tissue117. There remains some debate as to whether IL-33 and IL-25, other epithelial derived cytokines that promote type-2 inflammation, are elevated in nasal polyps118–121. Other classic type-2 inflammatory mediators including IL-5, IL-13, Eotaxin-1 (CCL11), Eotaxin-2 (CCL24) and Eotaxin 3 (CCL26) are often the products of epithelium and have been reported to be elevated in nasal polyps compared to healthy control tissues122–127.

It is important to note, however, that most early studies examining CRSwNP evaluated patients of European descent. More recently, studies have reported that nasal polyps from Asian patients living in Asia or second generation Asians residing in the United States have an enhanced type-1 inflammatory environment with elevated levels of IFN-γ and reduced levels of IL-5128, 129. It remains unclear why Asian patients are more likely to have a type-1 inflammatory profile in nasal polyps compared to patients from Western countries but a yet-to-be-identified genetic factor may play a role129.

Finally, unique characteristics that distinguish CRSsNP from other CRS subsets remain under debate. Historically, CRSsNP was thought to have a predominant type-1 inflammatory environment with more IFN-γ and less IL-5 expression than in nasal polyps from CRSwNP124, 125. More recently, however, this classification has been under review with several studies reporting similar levels of IFNγ expression in CRSwNP nasal polyps when compared to CRSsNP UT, control UT, or control IT tissues117, 128. In a more comprehensive analysis, no differences in gene expression levels of several interferon family members (IFNγ, IFNα2, IFNα8, and IFNβ1) were found between CRSwNP nasal polyps, CRSsNP UT, and control UT126. Furthermore, no significant difference in IFNγ protein levels was observed among all the sinonasal tissues examined126. Taken together, these findings suggest CRSsNP may not necessarily be more “type-1” than CRSwNP. However, regional variations in protein expression levels within the sinonasal cavity could possibly explain the discrepancies in IFNγ observed among the nasal polyp, ethmoid mucosa, inferior turbinate, middle turbinate and uncinate process sinonasal tissues80. Given these findings, further work is needed to more extensively characterize the cytokine environments in CRSsNP as well as CRSwNP.

The Innate Immune Response

There have been numerous studies examining the role of innate immune cells in the development of CRS pathology. In CRSwNP, type-2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) are thought to be early contributors to the type-2 inflammatory response. These specialized innate effector cells are elevated in nasal polyps and are activated by epithelial derived-cytokines such as TSLP and IL-33 to secrete IL-5 and IL-13130, 131. Interleukin-5 is a potent activator and survival factor for eosinophils and studies have shown that ILC2 numbers are doubled in eosinophilic compared to non-eosinophilic nasal polyps132.

While eosinophils are one of the major hallmarks of Western nasal polyps, mast cells and basophils, other type-2 innate inflammatory cells, are also elevated in CRSwNP compared to healthy controls133, 134. These innate effector cells can release a variety of inflammatory mediators and toxic granules that can perpetuate the chronic type-2 inflammatory response and induce sinonasal mucosal damage. Interestingly, a unique subset of mast cells was found in nasal polyp glandular epithelial cells that produced tryptase, carboxypeptidase A3, and chymase134. Since chymase is a known inducer of mucus, it is hypothesized that these specialized mast cells may play a role in the over-production of mucus commonly seen in CRSwNP134. Furthermore, a recent small study in CRSwNP reported that mast cells may be a reservoir for S. aureus and thus contribute to the chronicity of this infection in certain patients135.

In contrast to Western nasal polyps, Asian nasal polyps are characterized by reduced numbers of eosinophils as well as decreased levels of IL-5, Eotaxin, and eosinophil cationic protein, a protein found in eosinophil granules128, 129. In cystic fibrosis, neutrophils and macrophages are commonly detected115, 116. Unfortunately, no single defining innate effector cell has been identified in CRSsNP to date but this CRS subtype is associated with a lack of type-2 inflammation as previously discussed.

The Adaptive Immune Response

Along with the innate immune response, the adaptive immune system also contributes to the chronic inflammation seen in CRS. T cells represent a major component of adaptive immunity and, despite conflicting reports in CRSsNP, CD3+ T cells have been shown to be elevated in nasal polyps compared to healthy sinonasal tissue124, 127. Upon further analysis of CD3+ T cell populations by flow cytometry, no differences were reported in the number of either CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells in nasal polyps of CRSwNP versus inferior turbinates of patients with CRSsNP127. However, in this study, the ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells was significantly higher in CRSwNP than CRSsNP127. Finally, there have been several conflicting reports regarding the importance of regulatory T cells in CRS pathogenesis. Van Bruaene and colleagues initially identified a decrease in Foxp3 expression as well as the regulatory cytokine TGF-beta125. A later study found that suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) could negatively regulate Foxp3 expression in human airway mucosa and that SOCS3 protein levels were elevated in inflammatory cells in the airway mucosa136. These findings suggested that T regulatory cells were impaired in CRSwNP thus leading to an imbalance in pro- and anti-inflammatory responses. However, a later study using flow cytometric analyses reported increased numbers of T regulatory cells in CRSwNP137. Taken together, further studies examining T regulatory cells are needed to elucidate their role in CRSwNP and to determine if they are important in CRSsNP pathology.

In addition to T cells, B cells may also significantly contribute to the ongoing sinonasal inflammation observed in CRS138. In CRSwNP, naive B cells as well as activated plasma cells were found to be elevated in nasal polyps when compared to CRSsNP or healthy control tissue139–141. This influx in B cells may be secondary to the elevated levels of B cell chemotactic factors CXCL13 (BCA-1) and CXCL12 (SDF-1a, Stromal cell-derived factor-1) observed in nasal polyps142. BAFF and IL-6, both mediators important in B cell activation and proliferation, are increased in nasal polyps compared to controls with levels of BAFF strongly correlating with expression of CD20, another B cell marker140, 143.

Interestingly, B cells in nasal polyps also appear to have local effector functions. Levels of IgG1, IgG2, IgG4, IgA, IgE and IgM were all elevated in nasal polyps versus healthy sinonasal tissue141. Importantly, there was no concomitant elevation in these antibodies in the peripheral blood of the same CRSwNP patients suggesting that B cell antibody production in CRSwNP is not a systemic response but rather driven by a stimulus within the local sinonasal inflammatory environment141.

Unfortunately, the specificity of the majority of antibodies detected locally in nasal polyps in CRSwNP remains unclear. A certain subset of patients with CRSwNP who are also colonized with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) can develop specific IgE antibodies directed against S. aureus enterotoxins within nasal polyp tissue144. Additionally, other studies have reported elevated levels of IgG and IgA autoantibodies, particularly against nuclear antigens, locally produced in nasal polyps145. However, it remains unclear how these autoantibodies may contribute to disease pathology in CRSwNP.

Finally, even less is known regarding the role that B cells may play, if any, in CRSsNP. Naive B cells and plasma cells were not increased in UT from patients with CRSsNP compared to controls141. Additionally, there were no significant elevations in the immunoglobulin subtypes IgG, IgA, IgE, or IgM141, IgA or IgG autoantibodies145 or specific IgE to S. aureus144 locally in CRSsNP sinonasal tissue versus healthy controls. Interestingly, however, patients with CRSsNP are unique in that IgD is locally elevated within the sinonasal tissue in this population unlike in healthy controls or patients with CRSwNP146.

Tissue Remodeling

As in other chronic inflammatory diseases, tissue remodeling also occurs in CRS. However, the histological characteristics as well as mechanisms contributing to this upper airway remodeling are hypothesized to differ between CRSsNP and CRSwNP. Traditionally, CRSsNP is characterized by fibrosis, basement membrane thickening, and goblet cell hyperplasia. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), a key mediator in promoting fibrosis and airway remodeling, was found to be elevated in CRSsNP compared to CRSwNP and to healthy controls147. Likewise, expression of the TGF-β receptor as well as mediators critical in TGF-β signaling was also enhanced in CRSsNP sinonasal tissue147. Interestingly, there appears to be some regional variation in TGF-β protein expression throughout the sinonasal cavity with the inferior and middle turbinates having the lowest level of expression in CRSsNP148.

In contrast to CRSsNP, CRSwNP is histologically characterized by a significant inflammatory cell infiltrate, the formation of pseudocysts, and stromal tissue edema. Collagen levels are reduced in nasal polyps149 but there have been conflicting reports regarding TGF-β. One study suggests that TGF-β is reduced in CRSwNP125 while another study reported elevated levels when compared to healthy controls and/or CRSsNP150. More recently, TGF-β expression was found to be lower in epithelial cells but elevated in stromal cells in nasal polyps compared to the same cell subtypes in healthy sinonasal tissue151. These regional differences may also explain recent conflicting reports regarding the expression levels of Activin A, a member of the TGF-β superfamily hypothesized to play a role in remodeling in nasal polyps152, 153.

Another aspect of CRSwNP pathogenesis relates to the growth of nasal polyps themselves. In general, plasma proteins are enriched in affected sinus and polyp tissue due to vascular leak, and can traverse the dysfunctional epithelial barrier into the lumen in CRS. In nasal polyps, studies have shown that fibrin deposition is increased which, in turn, can form a scaffold, trapping plasma proteins and enhancing tissue edema154. This fibrin mesh is further stabilized by Factor XIIIa, which is also elevated in CRSwNP and thought to be another signature of a type-2 inflammatory environment155. Additionally, nasal polyps also have reduced levels of tissue plasminogen activator, an enzyme critical for the breakdown of fibrin mesh, as well as d-dimer, a product of fibrin degradation154. Taken together, these studies suggest that an imbalance in fibrin formation (elevated fibrin and factor XIIA) and degradation (reduced t-PA and d-dimer) may contribute to the polyp growth observed in CRSwNP (Figure 3).

Conclusions

In conclusion, significant advances have been made in the understanding of CRS pathogenesis. Mechanisms involving mucocilliary clearance, epithelial barrier dysfunction, the host immune response, and tissue remodeling all are thought to work in concert and contribute to the chronic inflammation characteristic of CRS. It is the goal of all working in this field that laboratory and clinical findings will continue to build the foundation upon which more developmental studies may be performed that advance diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for the benefit of affected patients.

Acknowledgements

Some of the research described in this review and effort directed towards writing the review was supported by USPHS grants R01DC013588, R21DC013886 (NAC), R03DC013862 (RJL); the National Institutes of Health grants T32 AI083216, R01 AI104733 (RPS); the Ernest S. Bazley Foundation (RPS); the Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Studies Program U19-AI106683 (RPS) and a philanthropic contribution from the RLG Foundation Inc., (NAC).

Figure 3 is a composite of two previous figures prepared by Ms. Jacqueline Schaffer and we would like to acknowledge her contribution.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl. 2012;3:1–298. p preceding table of contents. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, Dykewicz MS, Hellings PW, Naclerio RM, et al. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: a PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1479–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KA, Orlandi RR, Rudmik L. Cost of adult chronic rhinosinusitis: A systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1547–1556. doi: 10.1002/lary.25180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abreu NA, Nagalingam NA, Song Y, Roediger FC, Pletcher SD, Goldberg AN, et al. Sinus microbiome diversity depletion and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum enrichment mediates rhinosinusitis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:151ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feazel LM, Robertson CE, Ramakrishnan VR, Frank DN. Microbiome complexity and Staphylococcus aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:467–472. doi: 10.1002/lary.22398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boase S, Foreman A, Cleland E, Tan L, Melton-Kreft R, Pant H, et al. The microbiome of chronic rhinosinusitis: culture, molecular diagnostics and biofilm detection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aurora R, Chatterjee D, Hentzleman J, Prasad G, Sindwani R, Sanford T. Contrasting the microbiomes from healthy volunteers and patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:1328–1338. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.5465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramakrishnan VR, Feazel LM, Gitomer SA, Ir D, Robertson CE, Frank DN. The microbiome of the middle meatus in healthy adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e85507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas K, Hoggard M, Jain R, Taylor MW, Douglas RG. The nasal microbiota in health and disease: variation within and between subjects. Front Microbiol. 2015;9:134. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilos DL. Host-microbial interactions in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:640–653. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, Yoshinaga K, Rifkin DB, Sartor RB, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:571–577. doi: 10.1172/JCI15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groneberg DA, Peiser C, Dinh QT, Matthias J, Eynott PR, Heppt W, et al. Distribution of respiratory mucin proteins in human nasal mucosa. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:520–524. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillehoj EP, Kato K, Lu W, Kim KC. Cellular and molecular biology of airway mucins. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;303:139–202. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407697-6.00004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamblin G, Lhermitte M, Klein A, Houdret N, Scharfman A, Ramphal R, et al. The carbohydrate diversity of human respiratory mucins: a protection of the underlying mucosa? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:S19–S24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_pt_2.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feizi T, Gooi HC, Childs RA, Picard JK, Uemura K, Loomes LM, et al. Tumour-associated and differentiation antigens on the carbohydrate moieties of mucin-type glycoproteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 1984;12:591–596. doi: 10.1042/bst0120591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies J, Carlstedt I, Nilsson AK, Hakansson A, Sabharwal H, van Alphen L, et al. Binding of Haemophilus influenzae to purified mucins from the human respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2485–2492. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2485-2492.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy MS, Murphy TF, Faden HS, Bernstein JM. Middle ear mucin glycoprotein: purification and interaction with nontypable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:175–180. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prince A. Adhesins and receptors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated with infection of the respiratory tract. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:251–260. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90035-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sajjan SU, Forstner JF. Identification of the mucin-binding adhesin of Pseudomonas cepacia isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1434–1440. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1434-1440.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Button B, Cai LH, Ehre C, Kesimer M, Hill DB, Sheehan JK, et al. A periciliary brush promotes the lung health by separating the mucus layer from airway epithelia. Science. 2012;337:937–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1223012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanderson MJ, Sleigh MA. Ciliary activity of cultured rabbit tracheal epithelium: beat pattern and metachrony. J Cell Sci. 1981;47:331–347. doi: 10.1242/jcs.47.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee RJ, Foskett JK. Ca(2)(+) signaling and fluid secretion by secretory cells of the airway epithelium. Cell Calcium. 2014;55:325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Workman AD, Cohen NA. The effect of drugs and other compounds on the ciliary beat frequency of human respiratory epithelium. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:454–464. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee RJ, Xiong G, Kofonow JM, Chen B, Lysenko A, Jiang P, et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4145–4159. doi: 10.1172/JCI64240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao KQ, Cowan AT, Lee RJ, Goldstein N, Droguett K, Chen B, et al. Molecular modulation of airway epithelial ciliary response to sneezing. FASEB J. 2012;26:3178–3187. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mall MA, Galietta LJ. Targeting ion channels in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Illing EA, Woodworth BA. Management of the upper airway in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:623–631. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seshadri S, Lu X, Purkey MR, Homma T, Choi AW, Carter R, et al. Increased expression of the epithelial anion transporter pendrin/SLC26A4 in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishida A, Ohta N, Suzuki Y, Kakehata S, Okubo K, Ikeda H, et al. Expression of pendrin and periostin in allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol Int. 2012;61:589–595. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.11-OA-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams KM, Abraham V, Spielman D, Kolls JK, Rubenstein RC, Conner GE, et al. IL-17A induces Pendrin expression and chloride-bicarbonate exchange in human bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nofziger C, Dossena S, Suzuki S, Izuhara K, Paulmichl M. Pendrin function in airway epithelia. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28:571–578. doi: 10.1159/000335115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nofziger C, Vezzoli V, Dossena S, Schonherr T, Studnicka J, Nofziger J, et al. STAT6 links IL-4/IL-13 stimulation with pendrin expression in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:399–405. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gudis DA, Cohen NA. Cilia dysfunction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43:461–472. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gudis D, Zhao KQ, Cohen NA. Acquired cilia dysfunction in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:1–6. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson R, Pitt T, Taylor G, Watson D, MacDermot J, Sykes D, et al. Pyocyanin and 1-hydroxyphenazine produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibit the beating of human respiratory cilia in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:221–229. doi: 10.1172/JCI112787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao KQ, Goldstein N, Yang H, Cowan AT, Chen B, Zheng C, et al. Inherent differences in nasal and tracheal ciliary function in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa challenge. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:209–213. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen JC, Cope E, Chen B, Leid JG, Cohen NA. Regulation of murine sinonasal cilia function by microbial secreted factors. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2:104–110. doi: 10.1002/alr.21002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amitani R, Taylor G, Elezis EN, Llewellyn-Jones C, Mitchell J, Kuze F, et al. Purification and characterization of factors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus which affect human ciliated respiratory epithelium. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3266–3271. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3266-3271.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blount A, Zhang S, Chestnut M, Hixon B, Skinner D, Sorscher EJ, et al. Transepithelial ion transport is suppressed in hypoxic sinonasal epithelium. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1929–1934. doi: 10.1002/lary.21921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin HW, Cho K, Kim DW, Han DH, Khalmuratova R, Kim SW, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates nasal polypogenesis by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:944–954. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1706OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei CC, Adappa ND, Cohen NA. Use of topical nasal therapies in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2347–2359. doi: 10.1002/lary.24066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ooi EH, Wormald PJ, Tan LW. Innate immunity in the paranasal sinuses: a review of nasal host defenses. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:13–19. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramanathan M, Jr, Lane AP. Innate immunity of the sinonasal cavity and its role in chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker D, Prince A. Innate immunity in the respiratory epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:189–201. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0011RT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Persson CG. Plasma exudation in the airways: mechanisms and function. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:1268–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klockars M, Reitamo S. Tissue distribution of lysozyme in man. J Histochem Cytochem. 1975;23:932–940. doi: 10.1177/23.12.1104708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nash JA, Ballard TN, Weaver TE, Akinbi HT. The peptidoglycan-degrading property of lysozyme is not required for bactericidal activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:519–526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prokhorenko IR, Zubova SV, Ivanov AY, Grachev SV. Interaction of Gram-negative bacteria with cationic proteins: Dependence on the surface characteristics of the bacterial cell. Int J Gen Med. 2009;2:33–38. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods CM, Hooper DN, Ooi EH, Tan LW, Carney AS. Human lysozyme has fungicidal activity against nasal fungi. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:236–240. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woods CM, Lee VS, Hussey DJ, Irandoust S, Ooi EH, Tan LW, et al. Lysozyme expression is increased in the sinus mucosa of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 2012;50:147–156. doi: 10.4193/Rhino11.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tewfik MA, Latterich M, DiFalco MR, Samaha M. Proteomics of nasal mucus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:680–685. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalfa VC, Spector SL, Ganz T, Cole AM. Lysozyme levels in the nasal secretions of patients with perennial allergic rhinitis and recurrent sinusitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:288–292. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seshadri S, Lin DC, Rosati M, Carter RG, Norton JE, Suh L, et al. Reduced expression of antimicrobial PLUNC proteins in nasal polyp tissues of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2012;67:920–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clamp JR, Creeth JM. Some non-mucin components of mucus and their possible biological roles. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;109:121–136. doi: 10.1002/9780470720905.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Legrand D. Lactoferrin, a key molecule in immune and inflammatory processes. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90:252–268. doi: 10.1139/o11-056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sano H, Nagai K, Tsutsumi H, Kuroki Y. Lactoferrin and surfactant protein A exhibit distinct binding specificity to F protein and differently modulate respiratory syncytial virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2894–2902. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Psaltis AJ, Wormald PJ, Ha KR, Tan LW. Reduced levels of lactoferrin in biofilm-associated chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:895–901. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816381d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woodworth BA, Lathers D, Neal JG, Skinner M, Richardson M, Young MR, et al. Immunolocalization of surfactant protein A and D in sinonasal mucosa. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:461–465. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen PH, Fang SY. The expression of human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in the human nasal mucosa. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18:381–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim ST, Cha HE, Kim DY, Han GC, Chung YS, Lee YJ, et al. Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is upregulated in chronic nasal inflammatory disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:81–85. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000028089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamasaki K, Schauber J, Coda A, Lin H, Dorschner RA, Schechter NM, et al. Kallikrein-mediated proteolysis regulates the antimicrobial effects of cathelicidins in skin. FASEB J. 2006;20:2068–2080. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6075com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chennupati SK, Chiu AG, Tamashiro E, Banks CA, Cohen MB, Bleier BS, et al. Effects of an LL-37-derived antimicrobial peptide in an animal model of biofilm Pseudomonas sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:46–51. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Golec M. Cathelicidin LL-37: LPS-neutralizing, pleiotropic peptide. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2007;14:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yim S, Dhawan P, Ragunath C, Christakos S, Diamond G. Induction of cathelicidin in normal and CF bronchial epithelial cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sultan B, Ramanathan M, Jr, Lee J, May L, Lane AP. Sinonasal epithelial cells synthesize active vitamin D, augmenting host innate immune function. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:26–30. doi: 10.1002/alr.21087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hansdottir S, Monick MM. Vitamin D effects on lung immunity and respiratory diseases. Vitam Horm. 2011;86:217–237. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386960-9.00009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Akbar NA, Zacharek MA. Vitamin D: immunomodulation of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;19:224–228. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283465687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mulligan JK, Bleier BS, O'Connell B, Mulligan RM, Wagner C, Schlosser RJ. Vitamin D3 correlates inversely with systemic dendritic cell numbers and bone erosion in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164:312–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen PH, Fang SY. Expression of human beta-defensin 2 in human nasal mucosa. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:238–241. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0682-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee SH, Kim JE, Lim HH, Lee HM, Choi JO. Antimicrobial defensin peptides of the human nasal mucosa. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:135–141. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harder J, Meyer-Hoffert U, Teran LM, Schwichtenberg L, Bartels J, Maune S, et al. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa, TNF-alpha, and IL-1beta, but not IL-6, induce human beta-defensin-2 in respiratory epithelia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:714–721. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Proud D, Sanders SP, Wiehler S. Human rhinovirus infection induces airway epithelial cell production of human beta-defensin 2 both in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:4637–4645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schutte BC, McCray PB., Jr [beta]-defensins in lung host defense. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:709–748. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.134340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR, Regamey N. The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:210–229. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh PK, Jia HP, Wiles K, Hesselberth J, Liu L, Conway BA, et al. Production of beta-defensins by human airway epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14961–14966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tarran R, Grubb BR, Parsons D, Picher M, Hirsh AJ, Davis CW, et al. The CF salt controversy: in vivo observations and therapeutic approaches. Mol Cell. 2001;8:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tarran R, Redinbo MR. Mammalian short palate lung and nasal epithelial clone 1 (SPLUNC1) in pH-dependent airway hydration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;52:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tieu DD, Peters AT, Carter RG, Suh L, Conley DB, Chandra R, et al. Evidence for diminished levels of epithelial psoriasin and calprotectin in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:667–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seshadri S, Rosati M, Lin DC, Carter RG, Norton JE, Choi AW, et al. Regional differences in the expression of innate host defense molecules in sinonasal mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1227–130. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Do TQ, Moshkani S, Castillo P, Anunta S, Pogosyan A, Cheung A, et al. Lipids including cholesteryl linoleate and cholesteryl arachidonate contribute to the inherent antibacterial activity of human nasal fluid. J Immunol. 2008;181:4177–4187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee JT, Jansen M, Yilma AN, Nguyen A, Desharnais R, Porter E. Antimicrobial lipids: novel innate defense molecules are elevated in sinus secretions of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24:99–104. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wijkstrom-Frei C, El-Chemaly S, Ali-Rachedi R, Gerson C, Cobas MA, Forteza R, et al. Lactoperoxidase and human airway host defense. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:206–212. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0152OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fischer H. Mechanisms and function of DUOX in epithelia of the lung. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2453–2465. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fragoso MA, Fernandez V, Forteza R, Randell SH, Salathe M, Conner GE. Transcellular thiocyanate transport by human airway epithelia. J Physiol. 2004;561:183–194. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Conner GE, Wijkstrom-Frei C, Randell SH, Fernandez VE, Salathe M. The lactoperoxidase system links anion transport to host defense in cystic fibrosis. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moskwa P, Lorentzen D, Excoffon KJ, Zabner J, McCray PB, Jr, Nauseef WM, et al. A novel host defense system of airways is defective in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:174–183. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maniscalco M, Sofia M, Pelaia G. Nitric oxide in upper airways inflammatory diseases. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:58–69. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Degano B, Valmary S, Serrano E, Brousset P, Arnal JF. Expression of nitric oxide synthases in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1855–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Deja M, Busch T, Bachmann S, Riskowski K, Campean V, Wiedmann B, et al. Reduced nitric oxide in sinus epithelium of patients with radiologic maxillary sinusitis and sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:281–286. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-640OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Knight JA. Review: Free radicals, antioxidants, and the immune system. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2000;30:145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoon SS, Coakley R, Lau GW, Lymar SV, Gaston B, Karabulut AC, et al. Anaerobic killing of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa by acidified nitrite derivatives under cystic fibrosis airway conditions. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:436–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI24684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Major TA, Panmanee W, Mortensen JE, Gray LD, Hoglen N, Hassett DJ. Sodium nitrite-mediated killing of the major cystic fibrosis pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Burkholderia cepacia under anaerobic planktonic and biofilm conditions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4671–4677. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00379-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Phillips PS, Sacks R, Marcells GN, Cohen NA, Harvey RJ. Nasal nitric oxide and sinonasal disease: a systematic review of published evidence. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:159–169. doi: 10.1177/0194599810392667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lane AP, Truong-Tran QA, Schleimer RP. Altered expression of genes associated with innate immunity and inflammation in recalcitrant rhinosinusitis with polyps. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee RJ, Kofonow JM, Rosen PL, Siebert AP, Chen B, Doghramji L, et al. Bitter and sweet taste receptors regulate human upper respiratory innate immunity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1393–1405. doi: 10.1172/JCI72094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Farquhar DR, Kovatch KJ, Palmer JN, Shofer FS, Adappa ND, Cohen NA. Phenylthiocarbamide taste sensitivity is associated with sinonasal symptoms in healthy adults. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:111–118. doi: 10.1002/alr.21437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Adappa ND, Zhang Z, Palmer JN, Kennedy DW, Doghramji L, Lysenko A, et al. The bitter taste receptor T2R38 is an independent risk factor for chronic rhinosinusitis requiring sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:3–7. doi: 10.1002/alr.21253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee RJ, Cohen NA. The emerging role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:283–286. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Adappa ND, Howland TJ, Palmer JN, Kennedy DW, Doghramji L, Lysenko A, et al. Genetics of the taste receptor T2R38 correlates with chronic rhinosinusitis necessitating surgical intervention. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:184–187. doi: 10.1002/alr.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mfuna Endam L, Filali-Mouhim A, Boisvert P, Boulet LP, Bosse Y, Desrosiers M. Genetic variations in taste receptors are associated with chronic rhinosinusitis: a replication study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:200–206. doi: 10.1002/alr.21275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee RJ, Cohen NA. Sinonasal solitary chemosensory cells "taste" the upper respiratory environment to regulate innate immunity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:366–373. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee RJ, Cohen NA. Bitter and sweet taste receptors in the respiratory epithelium in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92:1235–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee RJ, Cohen NA. Taste receptors in innate immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:217–236. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1736-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pezzulo AA, Gutierrez J, Duschner KS, McConnell KS, Taft PJ, Ernst SE, et al. Glucose depletion in the airway surface liquid is essential for sterility of the airways. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hatten KM, Palmer JN, Lee RJ, Adappa ND, Kennedy DW, Cohen NA. Corticosteroid use does not alter nasal mucus glucose in chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:1140–1144. doi: 10.1177/0194599815577567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang Z, Adappa ND, Lautenbach E, Chiu AG, Doghramji L, Howland TJ, et al. The effect of diabetes mellitus on chronic rhinosinusitis and sinus surgery outcome. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:315–320. doi: 10.1002/alr.21269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim U, Wooding S, Ricci D, Jorde LB, Drayna D. Worldwide haplotype diversity and coding sequence variation at human bitter taste receptor loci. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:199–204. doi: 10.1002/humu.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Soyka MB, Wawrzyniak P, Eiwegger T, Holzmann D, Treis A, Wanke K, et al. Defective epithelial barrier in chronic rhinosinusitis: the regulation of tight junctions by IFN-gamma and IL-4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1087–1096. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pothoven KL, Norton JE, Hulse KE, Suh LA, Carter RG, Rocci E, et al. Oncostatin M promotes mucosal epithelial barrier dysfunction, and its expression is increased in patients with eosinophilic mucosal disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nomura K, Obata K, Keira T, Miyata R, Hirakawa S, Takano K, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase causes transient disruption of tight junctions and downregulation of PAR-2 in human nasal epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2014;15:21. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Malik Z, Roscioli E, Murphy J, Ou J, Bassiouni A, Wormald PJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus impairs the airway epithelial barrier in vitro. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:551–556. doi: 10.1002/alr.21517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rudack C, Steinhoff M, Mooren F, Buddenkotte J, Becker K, von Eiff C, et al. PAR-2 activation regulates IL-8 and GRO-alpha synthesis by NF-kappaB, but not RANTES, IL-6, eotaxin or TARC expression in nasal epithelium. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1009–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ossovskaya VS, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptors: contribution to physiology and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:579–621. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sobol SE, Christodoulopoulos P, Manoukian JJ, Hauber HP, Frenkiel S, Desrosiers M, et al. Cytokine profile of chronic sinusitis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1295–1298. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.11.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Steinke JW, Payne SC, Chen PG, Negri J, Stelow EB, Borish L. Etiology of nasal polyps in cystic fibrosis: not a unimodal disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121:579–586. doi: 10.1177/000348941212100904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nagarkar DR, Poposki JA, Tan BK, Comeau MR, Peters AT, Hulse KE, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin activity is increased in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:593–600. e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Baba S, Kondo K, Kanaya K, Suzukawa K, Ushio M, Urata S, et al. Expression of IL-33 and its receptor ST2 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:E115–E122. doi: 10.1002/lary.24462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lam M, Hull L, McLachlan R, Snidvongs K, Chin D, Pratt E, et al. Clinical severity and epithelial endotypes in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:121–128. doi: 10.1002/alr.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Miljkovic D, Bassiouni A, Cooksley C, Ou J, Hauben E, Wormald PJ, et al. Association between group 2 innate lymphoid cells enrichment, nasal polyps and allergy in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2014;69:1154–1161. doi: 10.1111/all.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lam M, Hull L, Imrie A, Snidvongs K, Chin D, Pratt E, et al. Interleukin-25 and interleukin-33 as mediators of eosinophilic inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015;29:175–181. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Olze H, Forster U, Zuberbier T, Morawietz L, Luger EO. Eosinophilic nasal polyps are a rich source of eotaxin, eotaxin-2 and eotaxin-3. Rhinology. 2006;44:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yao T, Kojima Y, Koyanagi A, Yokoi H, Saito T, Kawano K, et al. Eotaxin-1, -2, and -3 immunoreactivity and protein concentration in the nasal polyps of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1053–1059. doi: 10.1002/lary.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Van Zele T, Claeys S, Gevaert P, Van Maele G, Holtappels G, Van Cauwenberge P, et al. Differentiation of chronic sinus diseases by measurement of inflammatory mediators. Allergy. 2006;61:1280–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Van Bruaene N, Perez-Novo CA, Basinski TM, Van Zele T, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, et al. T-cell regulation in chronic paranasal sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1435–1441. 41 e1–41 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Stevens WW, Ocampo CJ, Berdnikovs S, Sakashita M, Mahdavinia M, Suh L, et al. Cytokines in Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Role in Eosinophilia and Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2278OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Derycke L, Eyerich S, Van Crombruggen K, Perez-Novo C, Holtappels G, Deruyck N, et al. Mixed T helper cell signatures in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without polyps. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhang N, Van Zele T, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene N, Holtappels G, DeRuyck N, et al. Different types of T-effector cells orchestrate mucosal inflammation in chronic sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mahdavinia M, Suh LA, Carter RG, Stevens WW, Norton JE, Kato A, et al. Increased noneosinophilic nasal polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis in US second-generation Asians suggest genetic regulation of eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:576–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mjosberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, van Drunen CM, Piet B, et al. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shaw JL, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Porter PC, Corry DB, Kheradmand F, et al. IL-33-responsive innate lymphoid cells are an important source of IL-13 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:432–439. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2227OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Walford HH, Lund SJ, Baum RE, White AA, Bergeron CM, Husseman J, et al. Increased ILC2s in the eosinophilic nasal polyp endotype are associated with corticosteroid responsiveness. Clin Immunol. 2014;155:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mahdavinia M, Carter RG, Ocampo CJ, Stevens W, Kato A, Tan BK, et al. Basophils are elevated in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis without aspirin sensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1759–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Takabayashi T, Kato A, Peters AT, Suh LA, Carter R, Norton J, et al. Glandular mast cells with distinct phenotype are highly elevated in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:410–420. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hayes SM, Howlin R, Johnston DA, Webb JS, Clarke SC, Stoodley P, et al. Intracellular residency of Staphylococcus aureus within mast cells in nasal polyps: A novel observation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1648–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lan F, Zhang N, Zhang J, Krysko O, Zhang Q, Xian J, et al. Forkhead box protein 3 in human nasal polyp regulatory T cells is regulated by the protein suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1314–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Pant H, Hughes A, Schembri M, Miljkovic D, Krumbiegel D. CD4(+) and CD8(+) regulatory T cells in chronic rhinosinusitis mucosa. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:e83–e89. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.28.4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kato A, Hulse KE, Tan BK, Schleimer RP. B-lymphocyte lineage cells and the respiratory system. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:933–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.023. quiz 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Local immunoglobulin production in nasal polyposis is modulated by superantigens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1840–1847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kato A, Peters A, Suh L, Carter R, Harris KE, Chandra R, et al. Evidence of a role for B cell-activating factor of the TNF family in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1385–1392. 92 e1–92 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hulse KE, Norton JE, Suh L, Zhong Q, Mahdavinia M, Simon P, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is characterized by B-cell inflammation and EBV-induced protein 2 expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1075–1083. 83 e1–83 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Patadia M, Dixon J, Conley D, Chandra R, Peters A, Suh LA, et al. Evaluation of the presence of B-cell attractant chemokines in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24:11–16. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Peters AT, Kato A, Zhang N, Conley DB, Suh L, Tancowny B, et al. Evidence for altered activity of the IL-6 pathway in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:397–403. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Watelet JB, Claeys G, Holtappels G, Claeys C, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and IgE antibody formation to enterotoxins is increased in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:981–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tan BK, Li QZ, Suh L, Kato A, Conley DB, Chandra RK, et al. Evidence for intranasal antinuclear autoantibodies in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1198–1206. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Min JY, Kern RC, Hulse KE, Chandra R, Conley D, Suh L, et al. Evidence for Immunoglobulin D in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;133:AB236. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Van Bruaene N, Derycke L, Perez-Novo CA, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, et al. TGF-beta signaling and collagen deposition in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:253–259. 9 e1–9 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Van Bruaene N, C PN, Van Crombruggen K, De Ruyck N, Holtappels G, Van Cauwenberge P, et al. Inflammation and remodelling patterns in early stage chronic rhinosinusitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Meng J, Zhou P, Liu Y, Liu F, Yi X, Liu S, et al. The development of nasal polyp disease involves early nasal mucosal inflammation and remodelling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zaravinos A, Soufla G, Bizakis J, Spandidos DA. Expression analysis of VEGFA, FGF2, TGFbeta1, EGF and IGF1 in human nasal polyposis. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Balsalobre L, Pezato R, Perez-Novo C, Alves MT, Santos RP, Bachert C, et al. Epithelium and stroma from nasal polyp mucosa exhibits inverse expression of TGF-beta1 as compared with healthy nasal mucosa. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;42:29. doi: 10.1186/1916-0216-42-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Yang Y, Zhang N, Crombruggen KV, Lan F, Hu G, Hong S, et al. Differential Expression and Release of Activin A and Follistatin in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with and without Nasal Polyps. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]