Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) has been associated with adverse health outcomes, including reproductive function in adults1 and neurodevelopment in children exposed perinatally.2 Exposure to BPA is primarily through dietary ingestion, including consumption of canned foods.3 A less-studied source of exposure is thermal receipt paper,4 handled daily by many people at supermarkets, ATM machines, gas stations, and other settings. We hypothesized that handling of thermal receipts significantly increases BPA exposure, but use of gloves during handling minimizes exposure.

Methods

In 2010–2011, after obtaining written informed consent, we recruited Harvard School of Public Health students and staff (aged >18 years, nonpregnant) via informational fliers and e-mail. No sample size calculation was performed for this pilot study, which was approved by the Harvard University institutional review board.

We used a simulation cross-over study design. At the first simulation, participants printed and handled receipts continuously for 2 hours without gloves. After a washout period of at least 1 week, a second simulation was conducted in which participants repeated handling of receipts wearing nitrile gloves. The option to participate in the second simulation or to provide sequential urine samples following the first simulation was offered to all participants at study entry.

All participants provided a spot urine sample, collected in a sterile BPA-free polypropylene specimen cup, immediately before handling of receipts and 4 hours later. Volunteers provided additional sequential urine samples at 8, 12, and 24 hours after handling of receipts without gloves. Urinary-specific gravity was measured using a handheld refractometer. Urine was stored in polypropylene cryogenic vials at or below −20°C until analysis. Total (free plus conjugated species) urinary BPA concentration was measured at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention using published methods.1 Concentrations of BPA were adjusted for specific gravity to account for urine dilution.

Using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc), mixed regression models were used to examine associations between log-transformed specific gravity–adjusted urinary BPA concentrations for prehandling and posthandling samples and across time points for those who provided sequential urine samples. Statistical significance was set at a P ≤ .05 (2-sided test).

Results

Twenty-four volunteers (mean age [SD], 35 [12] years) provided at least 2 urine samples for the simulation without gloves; 12 volunteers provided additional sequential samples and 12 also completed the simulation with gloves (Table). We excluded 1 participant for reporting consumption of 4 cans of beverage prior to the simulation (baseline urinary BPA concentration of 49.3 µg/L vs <2 µg/L for the remaining participants, decreasing to 12.0 µg/L postsimulation).

Table.

Demographic Characteristics of 24 Study Participants

| Simulation Without Gloves (n = 24)a |

Sequential Urine Samples (n = 12) |

Simulation With Gloves (n = 12) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Femalea | 19 (79) | 8 (67) | 9 (75) |

| Male | 5 (21) | 4 (33) | 3 (25) |

| Age, mean (SD) [range], y | 35 (12) [26–71] | 33 (12) [26–71] | 34 (13) [26–71] |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| Whitea | 15 (63) | 9 (75) | 7 (58) |

| Black | 5 (21) | 2 (17) | 2 (17) |

| Asian | 4 (17) | 1 (1) | 3 (25) |

| Specific gravity–adjusted bisphenol A at baseline, geometric mean (95% CI), µg/L | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | 2.1 (1.4–3.3) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1)b |

One participant was excluded from final analyses because of high background exposure to bisphenol A from consuming 4 cans of cold beverage (had urinary-specific gravity–adjusted bisphenol A concentration 25-fold higher than the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2010 geometric mean of 1.83 µg/L6).

There was no statistically significant baseline difference for simulations with gloves vs without gloves (P = .76).

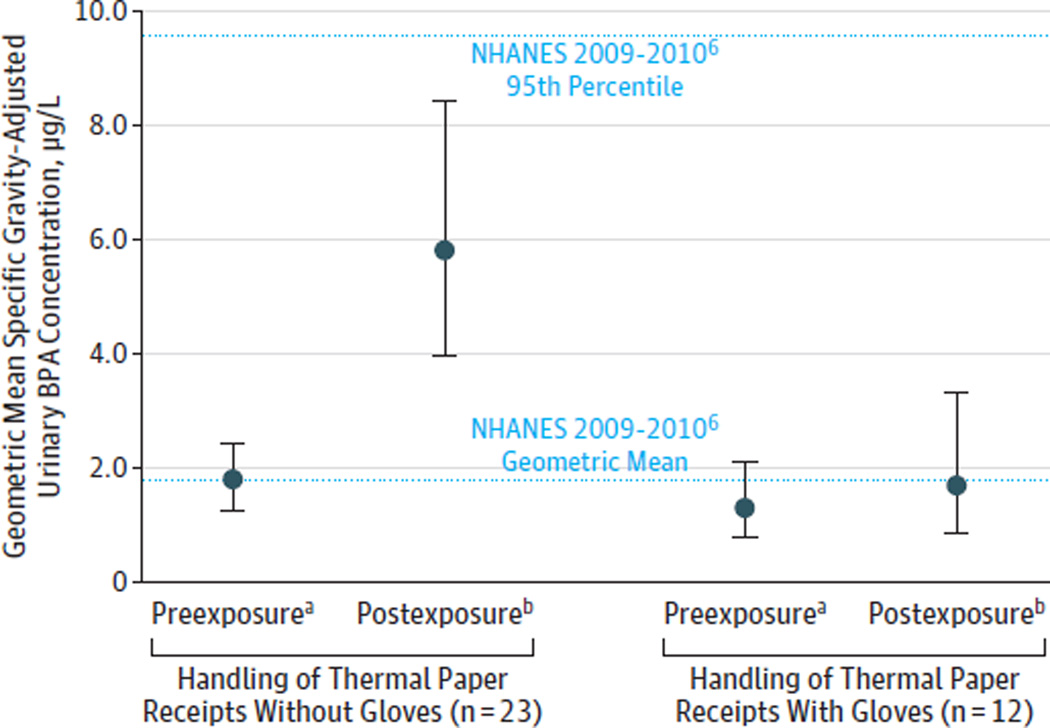

We detected BPA in 83% (n = 20) of samples at baseline and in 100% of samples after handling receipts without gloves. The geometric mean urinary BPA concentration was 1.8 µg/L (95% CI, 1.3–2.4 µg/L) before simulation and 5.8 µg/L (95% CI, 4.0–8.4 µg/L) postsimulation (P = .005 for interaction between presimulation and postsimulation BPA and glove status). The geometric mean BPA urinary concentrations from 12 participants who provided sequential samples following receipt handling without gloves were 2.1 µg/L (95% CI, 1.4–3.3 µg/L) at baseline, 6.0 µg/L (95% CI, 3.4–10.7 µg/L) at 4 hours, 11.1 µg/L (95% CI, 5.5–22.8 µg/L) at 8 hours, 10.5 µg/L (95%CI, 4.9–22.6 µg/L) at 12 hours, and 4.7 µg/L (95%CI, 2.4–9.1 µg/L) at 24 hours. Each measure was significantly different from baseline (P < .001 for 4-hour, 8-hour, and 12-hour urine samples and P = .04 for 24-hour samples). We observed no significant increase in urinary BPA after handling receipts with gloves (Figure).

Figure. Geometric Mean–Specific Gravity-Adjusted Urinary Bisphenol A (BPA) Concentration.

Error bars indicate 95%confidence intervals. NHANES indicates National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

a Adjusted BPA at 0 hours (baseline).

b Adjusted BPA at 4 hours (handled receipts for 2 hours).

Discussion

In this pilot study, we observed an increase in urinary BPA concentrations after continuously handling receipts for 2 hours without gloves, but no significant increase when using gloves. The peak level (5.8 µg/L) was lower than that observed after canned soup consumption (20.8µg/L).3 The clinical implications of the height of the peak level and the chronicity of exposure are unknown, but may be particularly relevant to occupationally exposed populations such as cashiers,5 who handle receipts 40 or more hours per week.

Limitations include the small volunteer sample and loss of participants in the second simulation. However, urinary BPA concentrations at baseline were similar in the full and smaller groups and similar to the US population (1.83 µg/L).6 A larger study is needed to confirm our findings and evaluate the clinical implications.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This project was supported by grant 2 T42 OH008416-05 from the Harvard-NIOSH Education and Research Center.

Role of the Sponsor: The Harvard-NIOSH Education and Research Center had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We thank Lori Torf (Harvard School of Public Health cafeteria) for providing us with access to the cafeteria cash registers for the simulations. We also thank the Hauser staff for assistance with storage of samples and supplies, Greg Wagner, MD (Harvard School of Public Health), for his advice and support at the start of the study, and Xiaoyun Ye, MS, Xiaoliu Zhou, MS, Tao Jia, MS, and Joshua Kramer (all 4 with the CDC) for technical assistance in measuring urinary bisphenol A. None of the individuals acknowledged were compensated for their contributions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Ehrlich had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Ehrlich, Smith, Hauser.

Acquisition of data: Ehrlich, Calafat.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Ehrlich, Calafat, Humblet, Smith, Hauser.

Drafting of the manuscript: Ehrlich, Humblet, Hauser.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ehrlich, Calafat, Humblet, Smith, Hauser.

Statistical analysis: Ehrlich, Humblet, Hauser.

Obtained funding: Ehrlich.

Administrative, technical, and material support: Ehrlich, Calafat.

Study supervision: Ehrlich, Calafat, Hauser.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The involvement of the CDC was determined not to constitute engagement in human subjects research.

References

- 1.Ehrlich S, Williams PL, Missmer SA, et al. Urinary bisphenol A concentrations and early reproductive health outcomes among women undergoing IVF. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3583–3592. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Calafat AM, et al. Impact of early-life bisphenol A exposure on behavior and executive function in children. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):873–882. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carwile JL, Ye X, Zhou X, Calafat AM, Michels KB. Canned soup consumption and urinary bisphenol A: a randomized crossover trial. JAMA. 2011;306(20):2218–2220. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biedermann S, Tschudin P, Grob K. Transfer of bisphenol A from thermal printer paper to the skin. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398(1):571–576. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3936-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Calafat AM, et al. Variability and predictors of urinary bisphenol A concentrations during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(1):131–137. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Environmental Health. Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals, updated tables. [January 25, 2014];2013 Sep; http://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/.