Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread protozoan parasite infecting nearly all warm-blooded organisms. Asexual reproduction of the parasite within its host cells is achieved by consecutive lytic cycles, which necessitates biogenesis of significant energy and biomass. Here we show that glucose and glutamine are the two major physiologically important nutrients used for the synthesis of macromolecules (ATP, nucleic acid, proteins, and lipids) in T. gondii, and either of them is sufficient to ensure the parasite survival. The parasite can counteract genetic ablation of its glucose transporter by increasing the flux of glutamine-derived carbon through the tricarboxylic acid cycle and by concurrently activating gluconeogenesis, which guarantee a continued biogenesis of ATP and biomass for host-cell invasion and parasite replication, respectively. In accord, a pharmacological inhibition of glutaminolysis or oxidative phosphorylation arrests the lytic cycle of the glycolysis-deficient mutant, which is primarily a consequence of impaired invasion due to depletion of ATP. Unexpectedly, however, intracellular parasites continue to proliferate, albeit slower, notwithstanding a simultaneous deprivation of glucose and glutamine. A growth defect in the glycolysis-impaired mutant is caused by a compromised synthesis of lipids, which cannot be counterbalanced by glutamine but can be restored by acetate. Consistently, supplementation of parasite cultures with exogenous acetate can amend the lytic cycle of the glucose transport mutant. Such plasticity in the parasite's carbon flux enables a growth-and-survival trade-off in assorted nutrient milieus, which may underlie the promiscuous survival of T. gondii tachyzoites in diverse host cells. Our results also indicate a convergence of parasite metabolism with cancer cells.

Keywords: bioenergetics, energy metabolism, gluconeogenesis, glucose metabolism, glutamine, glycolysis, lipid synthesis, metabolic regulation, parasite metabolism, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) (Krebs cycle)

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is an opportunistic intracellular pathogen of the phylum Apicomplexa that inflicts life-threatening acute and chronic infections in humans and animals (1). The parasite causes ocular and cerebral toxoplasmosis and sporadic abortion/stillbirth as a consequence of severe tissue necrosis in individuals with a poor or weakened immunity, e.g. neonates, AIDS, and organ-transplantation patients. The lytic cycle of T. gondii starts with the active energy-dependent invasion of host cells by the tachyzoite stage that is followed by rapid intracellular replication, egress by host-cell lysis, and reinvasion of adjacent cells. Upon infection of host cells in vitro, one tachyzoite can usually produce 32–64 daughter cells within a nonfusogenic vacuole, which provides a safe niche for the parasite replication and an interface for acquisition of host resources (1). Such an efficient asexual reproduction and concomitant expansion of the parasite vacuole requires a significant nutritional import and biomass synthesis within the parasite. Moreover, tachyzoites likely need to adjust metabolism according to variable bioenergetic demands of extracellular and intracellular states as well as to the nutritional cues in distinct host cells encountered by the parasite during its natural life cycle.

Tachyzoites encode all major pathways of central carbon metabolism including glycolysis, TCA cycle, pentose phosphate shunt and gluconeogenesis (2–4). Our earlier work showed that tachyzoites harbor a high affinity glucose transporter (TgGT1)3 in the plasma membrane that allows an efficient glucose import to the parasite interior (5) and a rapid glycolytic flux concurrent with excretion of lactate (6). Surprisingly, although glucose transport is required for an optimal growth of tachyzoites, it is dispensable for the parasite survival and virulence (5). The parasite mutant lacking the glucose transporter (Δtggt1) shows a higher uptake of glutamine, which can enable parasite motility and appears to offset the lack of sugar (5). Isotope-resolved metabolomics studies have confirmed catabolism of glucose and glutamine (7) as well as induction of gluconeogenesis upon glucose deprivation (8, 9). It has also been shown that T. gondii has repurposed a branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase for connecting glycolysis to the TCA cycle (8). Branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase converts glucose-derived pyruvate into acetyl-CoA and seems to substitute for pyruvate dehydrogenase, located in the parasite apicoplast (a non-photosynthetic plastid relict) instead of being in the mitochondrion (3). Pyruvate dehydrogenase produces the precursor acetyl-CoA for de novo synthesis of acyl chains via fatty acid synthase 2 pathway (FAS2) in the apicoplast of T. gondii (10).

In free-living organisms the aforementioned four routes of carbon metabolism constitute a metabolic hub to ensure the biomass, energy, and redox demands during cell proliferation as well as differentiation. The scope and extent to which these pathways satisfy the bioenergetic obligations during the intracellular and extracellular stages of T. gondii, is poorly understood, however. In particular, the following queries remain to be resolved: (a) does the Δtggt1 mutant indeed lack a glycolytic flux, especially when intracellular with access to host-derived metabolites; (b) what underlies such a modest growth defect in the mutant given the extensive and diverse metabolic usage of glucose; (c) how important is glutamine-derived carbon for parasite growth and survival; (d) how is metabolism of the two nutrients balanced to accommodate the biogenesis of macromolecules; (e) what are the actual mechanisms that ensure parasite survival in different milieus? Here, we show the mutual cooperation and importance of glucose, glutamine, and acetate metabolism in T. gondii while emphasizing the impact of parasite's metabolic potential on its pathogenesis and adaptation.

Materials and Methods

Biological Reagents and Resources

Cell culture media and additives were obtained from PAA and Biochrom (Germany). Other chemicals were purchased from Carl Roth (Germany), Sigma (Germany), and Applichem (Germany). Stable isotopes, d-[U-13C]glucose and l-[U-13C]glutamine, were acquired from Euriso-top and Campro Scientific (Germany). All U-14C-radioisotopes, namely glucose, glutamine, acetate, choline, ethanolamine, and serine were procured from Hartmann-Analytic (Germany). A mixture of [35S]cysteine/[35S]methionine (22:73) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Atovaquone, 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) and anti-HA antibody were obtained from Sigma. DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs. Oligonucleotides and fluorophore-conjugated antibodies (Alexa488, Alexa594) were acquired from Life Technologies. The RHΔku80-hxgprt− (11, 12) and RHΔku80-TaTi (13) strains of T. gondii were provided by Vern Carruthers (University of Michigan) and Boris Striepen (University of Georgia), respectively. TgGap45 (14), TgSag1 (15), and TgHsp90 (16) antibodies were donated by Dominique Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva, Switzerland), Jean-Francois Dubremetz (University of Montpellier, France), and Sergio Angel (National University of San Martín, Argentina), respectively. The plasmid for tagging and knock-out (pTKO) was provided by John Boothroyd (Stanford School of Medicine).

Cell Culture and Preparation of Extracellular Parasites

Tachyzoites of the specified strains were maintained by periodic passage in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF). Host cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), glucose (4.5 g/liter), glutamine (2 mm), sodium pyruvate (1 mm) non-essential amino acids (required for minimum essential medium), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) in a humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). Freshly egressed tachyzoites were used to infect confluent monolayers of HFF at a multiplicity of infection of 3 and cultured every second day unless stated otherwise. To prepare extracellular parasites for biochemical assays, infected host cells were grown in standard culture medium (multiplicity of infection 3; 40–44 h infection). Parasitized cultures were scraped in ice-cold PBS and extruded through 23G (1×) and 27G (2×) syringes, followed by filtering (5 μm) and centrifugation (400 × g, 10 min, 4 °C). Parasites were suspended in a defined medium (20 mm HEPES, 140 mm KCl, 10 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 μm CaCl2, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, MEM vitamins, MEM amino acids, nonessential amino acids, pH 7.4 (17)) for metabolic labeling assays. To test the viability, extracellular tachyzoites were mixed with 0.6% fluorescein diacetate and ethidium bromide solution and incubated for 5 min. Cells were visualized for green (viable) and/or red (dead) fluorescence signal. Our isolation procedure typically yielded viable extracellular parasites free of host-cell debris; a minor contribution of host metabolites cannot be entirely excluded, however.

Making of Δtggt1 and Δtggt1-TgGT1 Strains

The deletion of TgGT1 gene was performed in the RHΔku80-TaTi strain, essentially as shown before for the RH hxgprt− strain of T. gondii (5). Briefly, the knock-out construct contained 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR of the TgGT1 gene (2.7 kb each) flanking the chloramphenicol resistance cassette in the pTUB8CAT vector. Tachyzoites (107) were transfected with the plasmid (10 μg) and selected with chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) (18). Individual clones lacking TgGT1 expression (Δtggt1) were isolated by recombination-specific PCR screening of genomic DNA (5). The newly generated Δtggt1 strain differs from the former mutant with respect to the parental genotype (RHΔku80-TaTi instead of RH-hxgprt−). The RHΔku80-TaTi strain (13) offers two specific advantages; (a) first, the strain is deficient in non-homologous end-joining DNA repair (Δku80) (11, 12) and thus more amenable to homologous recombination-mediated genetic manipulation; (b) second, the TaTi (trans-activator trap identified) genotype permits conditional knockouts using the tetracycline-repressible transactivator system (19). These features together enable a comprehensive dissection of carbon metabolism in T. gondii that has not been so feasible otherwise. A complemented (Δtggt1-TgGT1) strain expressing the open reading frame of TgGT1 under the control of the NTP3-5′-UTR and 3′-UTR was produced by pyrimethamine (1 μm) selection (20).

Expression of Acetyl-CoA Synthetase (ACS)-HA in Tachyzoites

A single putative ACS, TGGT1_266640, was identified in the parasite genome (ToxoDB) by similarity with ACS sequences from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (YAL054C and YLR153C; Saccharomyces Genome Database). The open reading frame of TgACS was cloned, sequenced, and deposited to the NCBI GenBankTM database (accession number, KR013277). For C-terminal HA tagging of the endogenous TgACS protein, we amplified the 3′-end of the gene using CTCATCCCACCGGTCACCTGGAGTGGAAATGAAATCGAAGGG (the underline indicates the XcmI restriction site) and CTCATCGAATTCCTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAAGCTTTCGCAAGAGAGCCC (the underline indicates the in-frame HA tag and EcoRI restriction site) as the forward and reverse primers, respectively. The amplicon was cloned into pTKO-HXGPRT vector using XcmI and EcoRI enzymes. Tachyzoites (107) of the RHΔku80-hxgprt− strain were transfected with PstI-linearized construct (10 μg), and parasites expressing TgACS-HA under the regulation of native promoter and TgGRA2–3′-UTR were drug-selected with mycophenolic acid (25 μg/ml) and xanthine (50 μg/ml), as described elsewhere (21).

Immunodetection of Acetyl-CoA Synthetase

HFF host cells grown on glass coverslips were infected with the parasite strain expressing TgACS-HA. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (10 min), followed by neutralization with 0.1% glycine in PBS (5 min). Samples were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS (20 min), blocked with 2% BSA solution in 0.2% Triton X-100 and then stained with mouse αHA (1:1000) and rabbit αTgHsp90 (1:3000) antibodies. They were washed 3 times with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated with goat anti-mouse Alexa488- and anti-rabbit Alexa594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000), followed by 3× washing with PBS and mounting in DAPI-fluoromount G solution. Images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope equipped with AxioVision software (ApoTome, Zeiss, Germany). For immunoblot analysis, extracellular tachyzoites (∼2 × 107) were washed once with PBS (400 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Samples were first probed with rabbit anti-HA (1:3000, 2 h) and mouse anti-TgSag1 (1:1500, 2 h) as the primary antibodies and then with IRDye® 680RD and IRDye® 800CW as the secondary antibodies (1:15,000, 1 h).

Lytic Cycle Assays

Comparative growths of the indicated parasite strains were determined by plaque assays, which represent successive rounds of lytic cycles. Fresh extracellular tachyzoites (250) were used to infect PBS-washed confluent HFF monolayers in 6-well plates. Infected cells were cultured unperturbed for 7 days (37 °C, 5% CO2) in standard medium supplemented with normal FCS (10%) or with dialyzed FCS (10%) and additives as indicated. Samples were fixed with cold methanol (−80 °C) and stained with crystal violet for 10 min. Plaques were imaged and analyzed using the ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health). The parasite replication was examined by infecting HFF with 105 tachyzoites on glass coverslips placed in 24-well plates. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde 24 h post-infection and stained with rabbit αTgGap45 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa594 antibodies, as described above. Immunostained images were used to count the parasites replicating in vacuoles.

To assess invasion rates, fresh extracellular tachyzoites were suspended in standard culture medium with dialyzed serum (10%) and additives as indicated in figure legends. Subsequently, HFF cells seeded on glass coverslips were infected with fresh tachyzoites (4 × 105, 1 h, 37 °C, 5% CO2) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Parasitized cells were stained with mouse αTgSag1 antibody (1:1500) before permeabilization and incubated with rabbit αTgGap45 antibody (1:3000) after treatment with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Samples were then treated with goat anti-mouse Alexa488 and anti-rabbit Alexa594 antibodies (1:3000) before mounting in DAPI-fluoromount G solution. Immunofluorescence imaging was performed using the ApoTome microscope equipped with AxioVision software (Zeiss, Germany). Intracellular and extracellular parasites were identified by differential staining with TgGap45 only or with TgSag1 and TgGap45 antibodies, respectively. We also performed synchronized invasion assays following Kafsack et al. (22). Briefly, HFF cells grown on glass coverslips were infected with fresh syringe-released parasites (4 × 105) either in standard culture medium (control) or high potassium buffer (44.7 mm K2SO4, 10 mm MgSO4, 106 mm sucrose, 5 mm glucose, 20 mm Tris, 3.5 mg BSA/ml, pH 8.2). Parasites were allowed to settle for 30 min before medium was carefully replaced by standard culture medium (0.005 mm potassium) with or without 2 mm glutamine. Invasion assay was performed for 1 h, and samples were immunostained, as described above.

Stable Isotope Labeling of Tachyzoites

Tachyzoites of the indicated strains were labeled either during extracellular or intracellular stages. Extracellular parasites were prepared by syringe extrusion and filtering and washed 2× with ice-cold PBS. Purified parasites (108) were suspended in a defined labeling medium (20 mm HEPES, 140 mm KCl, 10 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 μm CaCl2, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, MEM vitamins, MEM amino acids, nonessential amino acids, pH 7.4 (17), supplemented with 5 mm [U-13C]glucose and 2 mm glutamine or with 5 mm glucose and 2 mm [U-13C]glutamine. The reactions were performed in a humidified incubator (4 h, 37 °C, 5% CO2). Metabolism was quenched by rapid cooling on ice, followed by centrifugation (400 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) and 2× washing of the parasite samples with ice-cold PBS. The parasite pellet was subjected to metabolite extraction, as described below. For intracellular labeling, parasites replicating in host cells (multiplicity of infection 3; 40 h infection) were incubated in standard culture medium containing either 5 mm [U-13C]glucose and 2 mm glutamine or 5 mm glucose and 2 mm [U-13C]glutamine (4 h, 37 °C, 5% CO2). Parasites were then purified for metabolite extraction by syringe extrusion and filtering, as stated above.

Metabolite Extraction and Metabolomics

Parasites (108) were suspended in 1 ml of ice-cold mixture of chloroform:methanol:water (1:3:1 v/v), and metabolites were extracted for 20 min at 60 °C, as described previously (7). After induction of phase separation with 0.4 ml of water, the polar phase was dried under vacuum, and the dry residue was derivatized in two steps, first with 2 μl of 4% solution of methoxyamine in pyridine (90 min, 30 °C), followed by the addition of 18 μl of MSTFA (N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide; 30 min, 37 °C).3 μl of the derivatized solution were injected onto the column for GC-MS analysis using Pegasus IV instrument (Leco Corp.), as reported elsewhere (23). Data extraction was performed using Leco ChromaTOF software. Metabolites were identified by fragmentation pattern using reference standards from the Golm metabolome database and by matching the retention index to the standard library of metaSysX GmbH. Inclusion of stable isotopes was calculated essentially as reported elsewhere (24). We identified an m/z peak corresponding to the intact or poorly fragmented derivatized analyte (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Centroid intensity of the unlabeled peak (M) or intensities of the labeled peaks with isotope inclusion from M+1 to M+n (where n corresponds to the number of carbons in underivatized metabolite) were used to quantify the incorporation of [13C]glucose and [13C]glutamine. The correction for the natural abundance of the stable isotopes present in the unlabeled precursors and in the trimethylsilyl derivatization group was performed assuming that M+1 analyte includes input from the natural isotopes in M (13C with a rate of natural occurrence equal to 1.1% or from 29Si with a rate of natural occurrence equal to 4.7%). Likewise, M+2 analyte includes input from M (30Si with a rate of natural occurrence equal to 3.02%) or from M+1, and M+3 analyte includes input from M+1 or from M+2, and so forth. Inclusion of isotopes was determined as the percentage of the sum of intensities of the labeled peaks to the total intensity of all detected isotopomers for a given metabolite (supplemental Table S1). Fractional abundance of 13C atoms as well as of individual isotopomers is shown for all those metabolites that were reproducibly detectable in independent assays (Fig. 1–2, supplemental Figs. S1–S6).

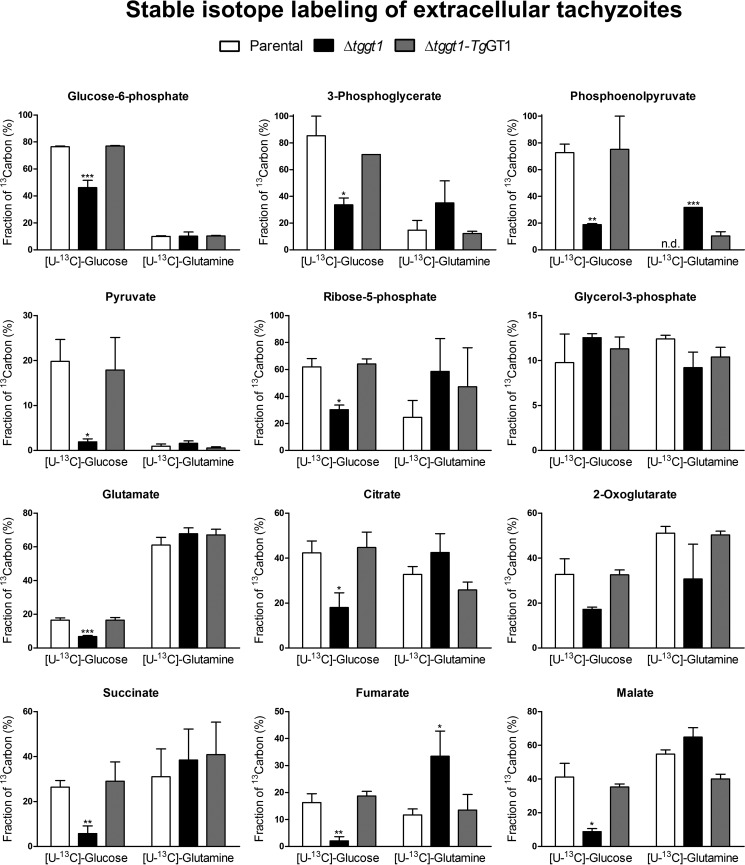

FIGURE 1.

Extracellular Δtggt1 strain is deficient in utilizing glucose-derived carbon, whereas glutamine metabolism is constitutively active. Shown is fractional abundance of 13C atoms in the carbon pool of selected metabolites from the indicated parasite strains labeled either with [U-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glutamine. Extracellular parasites were incubated with 5 mm [U-13C]glucose and 2 mm glutamine or with 2 mm [U-13C]glutamine and 5 mm glucose for 4 h (37 °C, 5% CO2) and then subjected to metabolomics analysis by GC-MS, as described under “Materials and Methods” (mean ± S.E., n = 4 assays). Corresponding heat-maps and labeling of individual isotopomers are illustrated in supplemental Figs. S3 and S4, respectively. Statistical significance was measured separately for each group compared with the parental strain using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). n.d., not detectable.

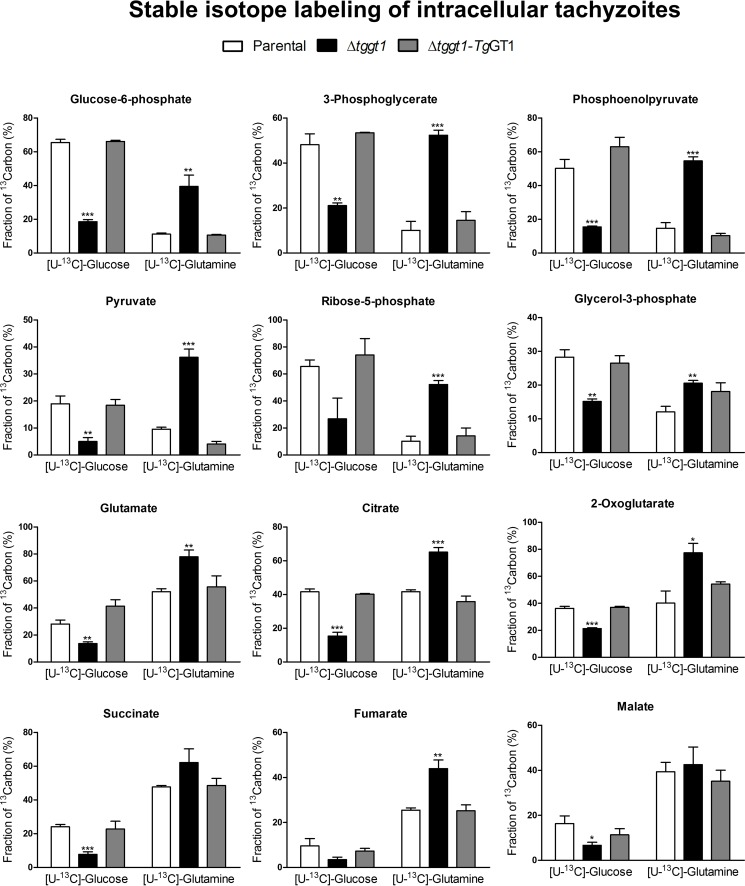

FIGURE 2.

Glutamine-derived carbon flux is induced in intracellular tachyzoites of the Δtggt1 strain. Fractional abundance of 13C atoms in the carbon pool of select metabolites from the indicated parasite strains incubated with 5 mm [U-13C]glucose and 2 mm glutamine or with 2 mm [U-13C]glutamine and 5 mm glucose. Intracellular parasites were labeled with either of the isotopes for 4 h (37 °C, 5% CO2) and subjected to metabolomics analysis by GC-MS, as defined under “Materials and Methods” (mean ± S.E., n = 4 assays). Corresponding heat-maps and labeling of individual isotopomers are shown in supplemental Figs. S5 and S6, respectively. Statistical significance was done separately for each group compared with the parental strain using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

Lipidomics Analysis

For lipidomics measurements, the parasite pellet (5 × 107) was suspended in ice-cold mixture (1.425 ml) of methyl tert-butyl ether and methanol (3:1, v/v). Samples were sonicated in a water bath (10 min, 4 °C) and then incubated on ice for 8 h with vortex-mixing every hour. Phase separation was achieved by adding 0.542 ml of cold H2O, followed by incubation on ice for an additional 2 h and centrifugation (5000 × g, 5 min). The upper organic phase was collected, dried under vacuum, dissolved in 120 μl of isopropyl alcohol and acetonitrile (3:7, v/v) and analyzed by ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatography (C8 column, Waters Inc.) coupled to MS/MS (Q Exactive Orbitrap, Excalibur suite (Thermo Scientific)), as described elsewhere (25). The electrospray ionization source was operated under standard conditions, and data were acquired in data-dependent acquisition mode with collision-induced dissociation fragmentation of precursor ions at 40 eV. Acyl composition of triacylglycerol species was determined by the [Acyl+NH4] neutral loss pattern of the precursor in positive ionization mode. Areas of chromatographic peaks of the selected lipid species were used to quantify the relative amount of lipids in the indicated parasite strains using Genedata Refiner 7.5 (supplemental Table S2).

Radiolabeling and Isolation of Biomass

Extracellular parasites (0.5–1 × 108) were incubated (4 h, 37 °C, 5% CO2) in defined labeling medium (17) containing either [U-14C]glucose (0.5 μCi, 0.1 mm) and 2 mm glutamine, or [U-14C]glutamine (0.5 μCi, 0.1 mm) and 2 mm glucose, or the precursors of major phospholipids, such as [U-14C]choline (2 μCi, 50 μm), [U-14C]serine (2 μCi, 90 μm), [U-14C]ethanolamine (1 μCi, 25 μm) or [U-14C]acetate (2 μm, 0.2 mm), or a mix of [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine (2 μCi, 0.2 mm each). Intracellular parasites (multiplicity of infection 3; 40 h infection) were labeled in standard culture medium containing the specified isotopes (4 h, 37 °C, 5% CO2) and then syringe-released and filtered to collect host-free parasites. Radiolabeled parasites were washed 3× in cold PBS to remove excess (unincorporated) radioactivity and subjected to nucleotide, protein, or lipid extractions as appropriate. Briefly, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol and PureLink kit (Life Technologies). Total proteins were extracted from the parasite pellets suspended in H2O (1 ml) and trichloroacetic acid (250 μl), followed by 2× washing with ice-cold acetone (15,000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) and drying at 95 °C. The eventual protein pellet was dissolved in water. Lipids were isolated by methanol-chloroform extraction, as described by Bligh and Dyer (26). The chloroform phase containing lipids was dried and suspended in 100 μl of chloroform/methanol (9:1) for measuring radioactivity and/or for two-dimensional thin layer chromatography on silica 60 plates in chloroform/methanol/ammonium hydroxide (84.5:45.5:6.5) and chloroform/acetic acid/methanol/water (80:12:9:2). Lipids were visualized by iodine staining and identified by their co-migration with commercial standards. Incorporation of radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry of individually isolated biomass fractions.

Quantification of Biomass and ATP

The parasite RNA was quantified by UV-absorption spectroscopy using the Beer-Lambert law. Total proteins were measured by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) using BSA as the internal standard (27). Phospholipids were scraped off the silica plate and measured by chemical phosphorus assay (28). To determine the cellular ATP, syringe-released parasites were filtered and washed 3× in ice-cold PBS. The parasite pellets (5 × 107 cells) were suspended in 250 μl of boiling water, cooled on ice, and then centrifuged (15,000 × g, 5 min, 4 °C) to generate the supernatant. ATP levels in the supernatant were measured using a commercial kit (Promega BacTiter-GloTM).

Data Plotting and Statistical Analyses

All assays were performed at least three independent times unless specified otherwise. Graphs were plotted using the GraphPad Prism suite. Error bars signify S.E. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test or analysis of variance and Bonferroni tests (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

Results

Genetic Ablation of Sugar Transport in T. gondii Impairs the Central Carbon Flux

We previously showed that the Δtggt1 mutant shows a negligible transport of glucose to the parasite interior (5). It is unclear, however, whether a defective sugar transport translates into a compromised glycolysis and TCA cycle. To answer this, we first generated the Δtggt1 mutant in the RHΔku80-TaTi strain, as reported before for the RH hxgprt− parental strain (5). We then performed labeling of extracellular parasites with [13C]glucose in defined medium supplemented with glutamine and other pertinent nutrients, and monitored the inclusion of stable isotopes into primary metabolites of the central carbon metabolism employing GC-MS. As shown elsewhere (7, 8), a panel of metabolites of glycolysis, pentose phosphate shunt, and TCA cycle as well as glycerol 3-phosphate (a precursor for lipid synthesis) and glutamate were significantly labeled in the parental strain (Fig. 1, supplemental Figs. S3 and S4). Usually, glycolytic and pentose phosphate shunt metabolites showed a higher (60–80%) fraction of 13C pool compared with the TCA cycle and other intermediates, which showed only 20–40% labeling with glucose (Fig. 1). The Δtggt1 mutant strain displayed an evidently lower inclusion of glucose-derived carbon in most of the metabolites, as shown by the fractional abundance of stable isotope in the indicated metabolites (Fig. 1, supplemental Fig. S3), as well as in their respective isotopomers (supplemental Fig. S4). The results suggested an impaired flux of glucose-derived carbon through glycolysis, pentose phosphate shunt, and the TCA cycle. As anticipated, ectopic expression of a functional glucose transporter in the complemented strain largely restored the carbon flux through all mentioned pathways.

Because intracellular parasites may access the metabolic intermediates generated by host metabolism of glucose, we examined the extent to which glycolysis and TCA cycle are operative in parasites replicating intracellularly. We labeled the parental, mutant and complemented strains replicating within human host cells in cultures containing [13C]glucose as a carbon source (Fig. 2, supplemental Figs. S5 and S6). The labeling patterns of the specified metabolites across the strains were similar to those seen in the extracellular parasites. Yet again, the Δtggt1 mutant exhibited a significant decline of sugar flux into all three pathways, and the TgGT1-complemented strain displayed an expected reversal of metabolic phenotype similar to the parental parasites (Fig. 2, supplemental Figs. S5 and S6). These data confirmed an impaired glycolysis in the Δtggt1 strain, which in turn reduces the carbon flux via pentose phosphate shunt and TCA cycle.

The Δtggt1 Mutant Shows Induction of Glutamine Metabolism

Previously, we showed that the parasite can utilize host-derived glutamine, and its consumption is enhanced when glucose is not available (5); therefore, a substitutive role of glutamine is anticipated. However, it is not known how the carbon fluxes of the two nutrients are balanced in extracellular and intracellular Δtggt1 parasites. To address this question, we labeled the mutant as well as parental and complemented strains with [13C]glutamine in cultures supplemented with glucose, followed by GC-MS analysis. All three strains utilized glutamine-derived carbon into the TCA cycle of extracellular (Fig. 1, supplemental Figs. S3 and S4) as well as of intracellular (Fig. 2, supplemental Figs. S5 and S6) stages under glucose-replete milieus. In contrast to glucose, incorporation of glutamine was more prevalent in the TCA cycle intermediates than glycolysis in the parental strains. Inclusion of glutamine into metabolites of central carbon metabolism was distinctly increased in the Δtggt1 mutant. Unlike the reference strains, the Δtggt1 mutant showed a prominently higher labeling of all detectable analytes of glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway with glutamine, indicating the activation of gluconeogenesis (Fig. 2, supplemental Figs. S5 and S6). Isotope labeling was reverted when glucose import was reinstated, which indicated a co-regulation of sugar and amino acid metabolism.

Glucose and glutamine together accounted for ∼60–80% of carbon tracer in TCA cycle metabolites (citrate, 2-oxoglutarate, succinate, malate) and glutamate in all three strains even though their relative proportions varied among individual strains (Fig. 1 and 2). In other words glutamine carbon largely compensated for the deficit of sugar in the Δtggt1 parasites, and catabolism of the amino acid reverted to the parental level when glucose transport was restored by complementation. Consistent with a high metabolic demand imposed by parasite division, labeling of intracellular parasites was usually more prominent than extracellular stage (supplemental Table S1). Collectively, the results show a constitutive metabolism of glutamine and suggest a mutual regulation of glycolysis, TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis in T. gondii.

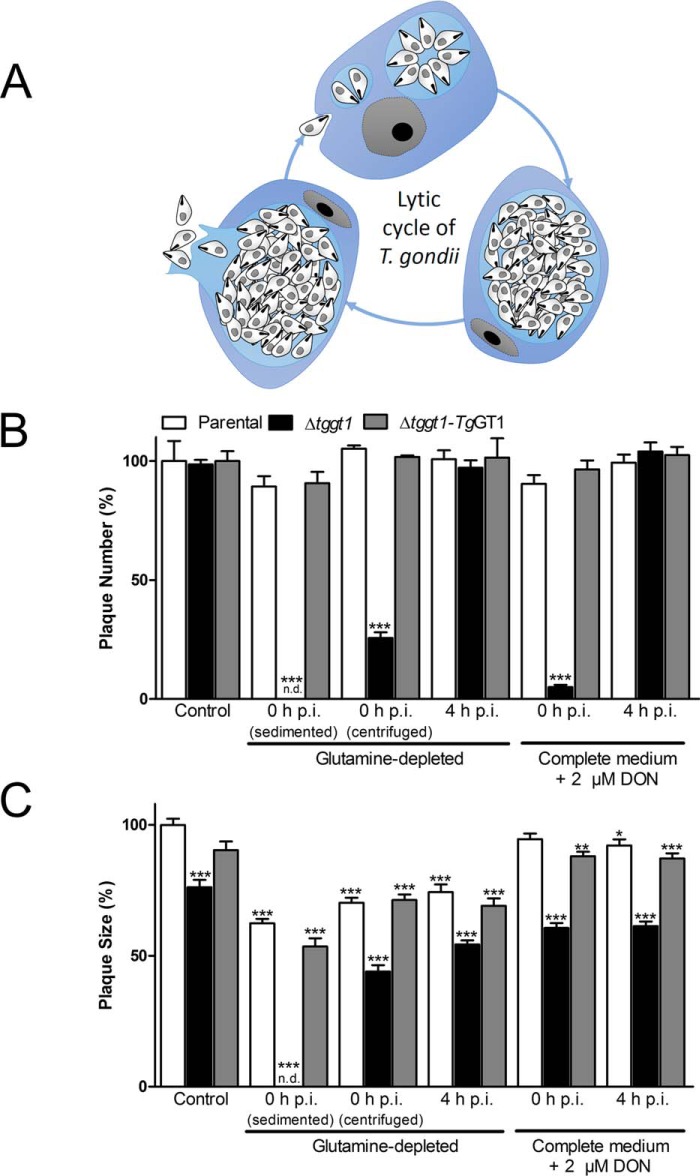

Glutamine Is Required to Establish the Infection but Not for Replication of the Δtggt1 Mutant

To examine the relative importance of glucose and glutamine for the overall growth of T. gondii, we performed plaque assays (Fig. 3, supplemental Fig. 7). The Δtggt1 mutant displayed an expected 25% growth defect in standard medium when compared with the parental and complemented parasites (5). An early removal of glutamine from cultures (Fig. 3B; 0 h sample, sedimented, i.e. natural floating of parasites to the host-cell monolayer) abolished the plaque formation in the mutant (no plaques), whereas the control strains exhibited normal plaque numbers. Consistently, the number of plaques formed by the Δtggt1 mutant was nearly ablated when a known analog inhibitor of glutamine catabolism, DON (29), was applied while setting up the assay (0 h). Conversely, consistent with glutamine-free cultures, the plaque numbers were largely unaffected in the parental and complemented strains treated with DON (compare 0 h samples; Fig. 3B). All three strains formed fairly similar number of plaques when withdrawal of glutamine or treatment with DON was deferred by 4 h to enable the initial parasite infection of host cells. Interestingly, the parental and complemented strains grown in glutamine-depleted medium showed only a modest 25% decline in plaque sizes when compared with the control cultures, whereas the Δtggt1 mutant displayed a somewhat accentuated 45% growth defect (Fig. 3C). Likewise, DON treatment exerted either negligible or a moderate (40%) effect on the control and Δtggt1 strains, respectively. These data demonstrate that exogenous glutamine is expendable in parasite cultures. They also show a differential dependence of glycolysis-competent and glycolysis-deficient parasites on glutamine catabolism for the lytic cycle.

FIGURE 3.

The Δtggt1 mutant can replicate without exogenous glutamine even though it is vital to establish the parasite infection. A, schematized lytic cycle of T. gondii tachyzoites showing the consecutive events of invasion, replication, and egress. B and C, plaque assays. Tachyzoites were cultured with or without glutamine (2 mm) in medium containing 10% dialyzed serum or treated without or with DON (2 μm) in standard culture medium (37 °C, 7 days, 5% CO2). Parasites added into the wells were allowed to sediment onto host cells by natural floating (sedimented) or centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min immediately after adding parasites (centrifuged). DON was added at the time of (0 h) or after (4 h) infection of host-cell monolayers. Plaques were stained by crystal violet and analyzed using the ImageJ suite. Plaque numbers (B) and sizes (C) from three assays are shown (mean ± S.E.). Supplemental Fig. S7 shows the corresponding plaque images. Statistics (Student's t test) in panels B and C were done with respect to the parental strain grown under control condition (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). n.d., not detectable ; p.i., post-infection.

The aforementioned plaque assays also indicated a possible role of glutamine in host-cell invasion by tachyzoites. Given that plaques are formed after multiple rounds of cell lysis and re-invasion, a modest difference in plaque size upon glutamine withdrawal (4 h) can also be interpreted as no subsequent invasion defect in the Δtggt1 strain. In other words, the invasion defect is seen only upon the addition of the mutant to the wells in the absence of glutamine (0 h), which may be caused by the loss of parasite viability during the time they naturally float down to host cells. In subsequent cycles, parasites can invade host cells more rapidly because they have less far to travel. To test the notion, we set up plaque assays in which parasites were rapidly settled by centrifugal force, thereby reducing the travel time to ≤10 min (0 h, centrifuged; Fig. 3B). Indeed, we observed some plaques in the mutant strain cultured in glutamine-free medium; however, their number was still markedly reduced (up to 80%) compared with control strains. Moreover, consistent with other data (Fig. 3C), the areas of those few emergent plaques were only moderately affected. These results together suggest a critical requirement of exogenous glutamine for the initial infection event (i.e. host-cell invasion) when glucose import is impaired.

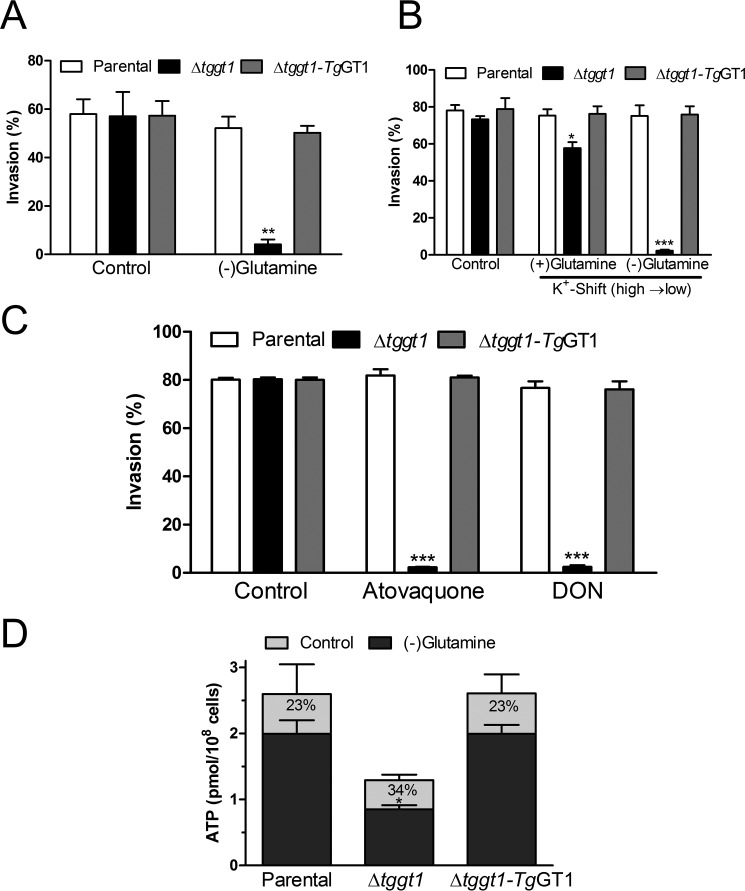

Glycolysis or Oxidative Phosphorylation Alone Is Sufficient to Drive the Invasion by T. gondi

Next, we tested the relative importance of glucose and glutamine catabolism by invasion assays using human fibroblast host cells (Fig. 4, A–C). Under normal culture conditions (control), all parasite strains invaded with a similar efficiency, which remained unaltered for the parental and complemented strains when glutamine was omitted. The Δtggt1 strain exhibited a nearly complete block of invasion in glutamine-free culture (Fig. 4A). To determine a direct involvement of glutamine in host-cell invasion, we performed a synchronized invasion assay, i.e. parasites were settled in high K+ medium before switching to low K+ (high Na+) medium to induce invasion (22). The mutant displayed a nearly complete loss of invasion when supplied with glutamine-free medium at the time of potassium shift, indicating a need of glutamine for host-cell infection. In contrast, a switching to glutamine-supplemented medium exerted only an ≈20% decline, which confirmed the viable and infective nature of most mutant parasites (Fig. 4B). We also examined invasion rates in the presence of DON (29) and atovaquone (inhibitor of respiratory chain; Ref. 30). Neither of the two inhibitors exerted a significant effect on the parental and complemented strains compared with the control samples; in contrast, both of them abolished invasion of the Δtggt1 strain (Fig. 4C). The results are consistent with plaque numbers in glutamine-depleted and DON-treated cultures (0 h time point in Fig. 3B). They also resonate well with hitherto known facts that the Δtggt1 mutant is impaired in gliding motility (required for invasion) in minimal medium, which could be restored by glutamine but not by pyruvate (5). Consistently, pyruvate (supplied in medium used for invasion assays) seems unable to counteract the collective absence of glucose and glutamine. These results show a strong dependence of tachyzoites on glutamine to facilitate the invasion event in the absence of glucose import.

FIGURE 4.

Glucose as well as glutamine alone can supply ample energy for host-cell invasion by T. gondii. A, invasion efficiency of the indicated parasite strains in culture medium supplemented with dialyzed serum (10%) and glutamine (2 mm, if any). Fresh syringe-released extracellular parasites were used to infect human fibroblast cells (37 °C, 5% CO2, 60 min), followed by staining with α-TgSag1 and α-TgGap45 antibodies. Glutamine-free samples were incubated without the amino acid for 30 min before invasion assay. B, synchronized host-cell invasion assay. Fresh tachyzoites were suspended in high K+ buffer and allowed to settle on host-cell monolayers for 30 min before exchanging buffers (high to low K+). Parasites were stained, as described in panel A. C, effect of known inhibitors of mitochondrial electron transport (atovaquone, 0.1 μm) and of glutamine catabolism (DON, 2 μm) on invasion rates of different parasite strains. Host cells were washed with ice-cold PBS before infection, and fresh medium supplemented with individual inhibitors was added at the time of invasion assay. D, ATP contents of extracellular parasites after incubation (37 °C, 5% CO2, 30 min) in culture medium supplemented with dialyzed FCS (10%) and glutamine (2 mm, if any). Relative declines are shown as percentages. The viability of all parasite strains was nearly 100%, which remained unaltered by glutamine depletion (not shown). Statistical significance (Student's t test) was measured separately for each group by comparing to the parental strain (panels A and B) or to the ATP levels of individual strains under control conditions (panel C) (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

We next measured ATP levels in fresh extracellular parasites incubated with or without glutamine (Fig. 4D). The steady-state ATP level in the Δtggt1 mutant was nearly half of the parental and complemented strains, which was nonetheless sufficient to sustain the invasion process (Fig. 4C). A short (30 min) incubation in glutamine-free medium caused a statistically significant 34% decline in ATP content of the mutant compared with a less prominent decline of 23% in the parental and complemented strains. The viability of all parasites in glutamine-free medium was not affected (not shown). Our invasion and ATP assays on the parental strains (Fig. 4) agree with earlier work reporting that extracellular parasites (RH hxgprt−) do not require an exogenous carbon source for the maintenance of ATP, gliding motility, and invasion (31). The fact that ATP content is reduced but not ablated in the glutamine-free Δtggt1 tachyzoites can be explained by endogenous glutamine and/or potential usage of alternative energy sources including γ-aminobutyric acid (7). A decline in energy below a certain threshold, however, appears to be inadequate for invasion by the Δtggt1 strain (Fig. 4). In conclusion, glucose and glutamine can deliver adequate energy for a normal invasion process, and glutamine-dependent ATP synthesis becomes very important when the parasite is unable to import glucose.

Glucose and Glutamine Together Facilitate the Biogenesis of Biomass in T. gondi

To investigate the importance of glucose and glutamine for anabolic metabolism, we determined their usage into major biomass components, i.e. nucleotides, proteins, and lipids. We incubated extracellular parasites of the aforementioned strains with either [14C]glucose or [14C]glutamine in defined medium with both carbon sources and quantified the incorporation of radioactivity into individual biomass fractions (Figs. 5 and 6A). We detected a robust incorporation of the radioactive label from glucose into the RNA of the parental and complemented strains, confirming the operation of pentose phosphate shunt in T. gondii (Fig. 5A), whereas incorporation of glutamine was significantly lower. Consistent with its inability to import the sugar (5), utilization of [14C]glucose was negligible in the Δtggt1 mutant. Conversely, [14C]glutamine labeling was similar to that of [14C]glucose in the parental and complemented strains. Total RNA levels were comparable in all three strains (Fig. 5B), signifying that even upon impairment of glycolysis the parasite maintained the necessary carbon flux through pentose phosphate pathway, apparently using glutamine-fueled gluconeogenesis. Neither glucose nor glutamine was utilized significantly for DNA synthesis, which resonates with the quiescent nature of extracellular parasites (not shown).

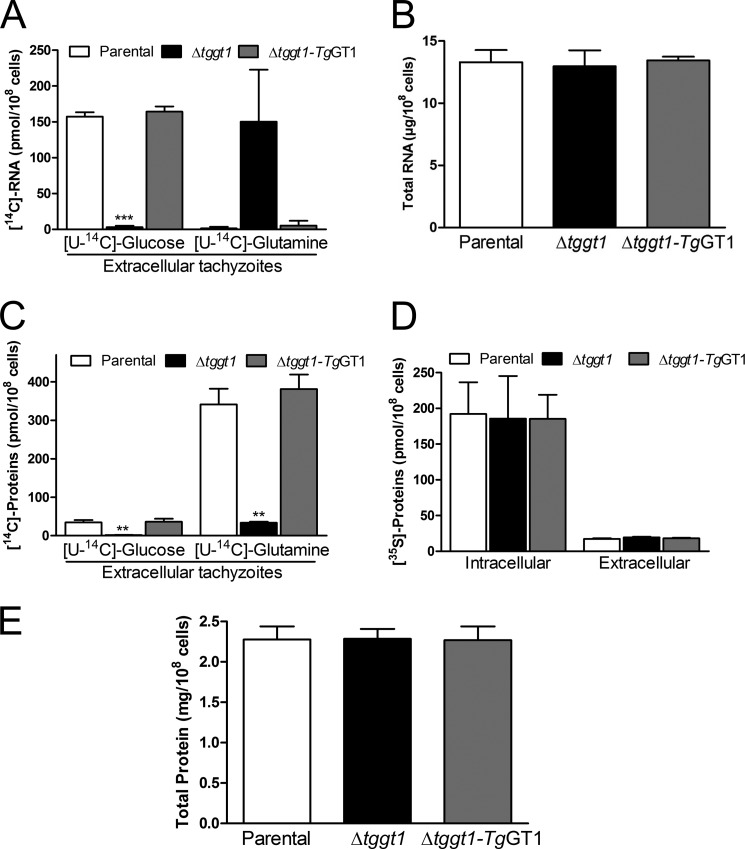

FIGURE 5.

Glucose and glutamine are co-utilized and co-regulated for ribogenesis and protein synthesis. A, metabolic labeling of RNA with [U-14C]glucose or [U-14C]glutamine. Fresh syringe-released parasites were cultured with either of the radioisotopes, followed by quantification of radiolabeling in total purified RNA (mean ± S.E., n = 3). RNA yields in all radiolabeled samples were similar (not shown). B, steady-state RNA content in extracellular tachyzoites, as quantified by UV absorption spectroscopy. C, radioisotope labeling of nascent proteins in extracellular parasites incubated with [U-14C]glucose or [U-14C]glutamine. The parasite proteins were extracted to determine the incorporated radioactivity (mean ± S.E., n = 3). D, radiolabeling of total proteins in extracellular and intracellular parasites incubated with a commercial mixture of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (mean ± S.E., n = 3). E, protein contents in extracellular parasites, as measured by bicinchoninic acid assay. Statistics was performed separately for each group using Student's t test (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

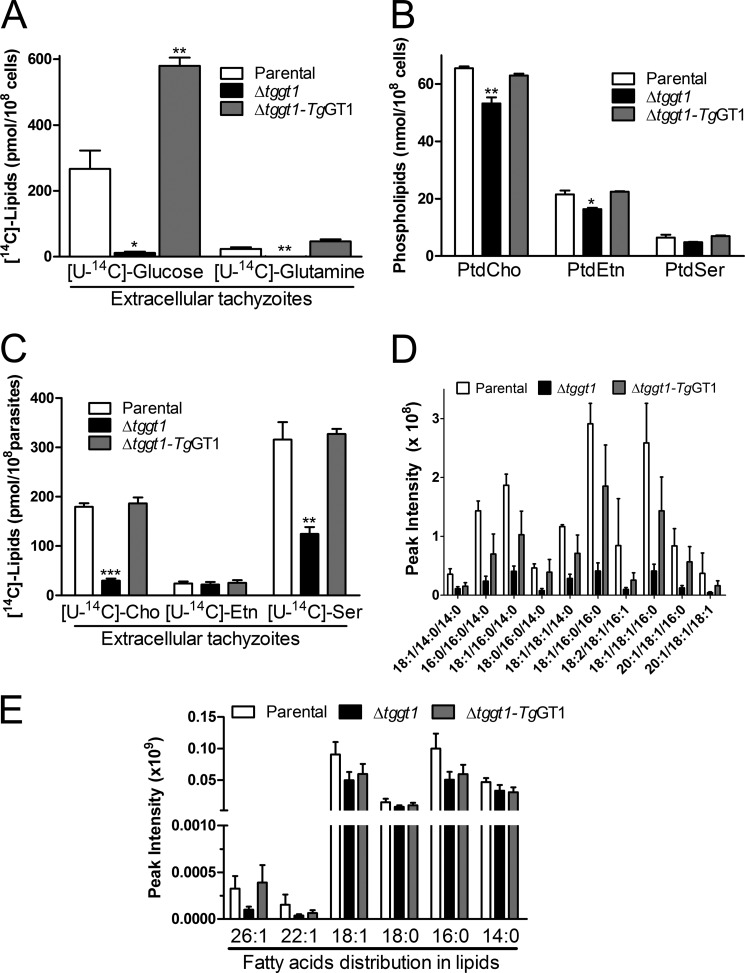

FIGURE 6.

A dysfunctional glycolysis is detrimental to the membrane biogenesis. A, metabolic labeling of nascent lipids using [U-14C]glucose or [U-14C]glutamine in extracellular parasites. Total parasite lipids were prepared to determine the radiolabeling by liquid scintillation counting. B, comparative amounts of three major lipids in the depicted strains. Phospholipids extracted from extracellular parasites were resolved by thin layer chromatography, detected by iodine-vapor staining, and quantified by chemical-phosphorous assay (see supplemental Fig. S8 for TLC images). PtdCho, phosphatidylcholine, PtdEtn, phosphatidylethanolamine, PtdSer, phosphatidylserine. C, radiolabeling of parasite lipids with choline, ethanolamine, or serine. Extracellular tachyzoites were incubated with either of the U-14C-labeled head groups and radiotracer incorporated into total lipids was measured. The data plotted in panels A–C show mean ± S.E. from three assays. D, relative contents of the major triacylglycerol species in the three parasite strains, as monitored by lipidomics analysis. Lipids isolated from fresh extracellular parasites were analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (mean ± S.E., n = 5). E, estimated amounts of acyl chains conjugated to total lipids in specified strains. Intensities on the y axis denote cumulative sum of all peaks corresponding to a given acyl chain irrespective of the bound lipid (mean ± S.E., n = 5). Lipids bound to the specific acyl chains were quantified from the areas of chromatographic peaks. Statistical significance was measured separately for each group with respect to the parental strain using Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). Note that the Δtggt1 mutant in panels D–E did not show any significant difference for individual lipid species; however, a collective reduction across all lipid species is very significant (two-way analysis of variance) (panel D, p < 0.0001; panel E, p = 0.0060).

The radiolabeling of total parasite protein in the parental and complemented strains demonstrated that incorporation of glucose was ∼6-fold lower than that of glutamine (Fig. 5C). Labeling of nascent proteins by glucose can be explained by the synthesis of nonessential amino acids (e.g. glutamate) from sugar (Figs. 1 and 2), whereas glutamine is possibly incorporated into proteins directly. A fraction of sugar-labeled proteins may also represent glycosylated proteins present in tachyzoites (32). Protein labeling was either completely ablated (in the case of [14C]glucose) or evidently reduced (if [14C]glutamine was used) in the Δtggt1 mutant. Although the absence of protein labeling with radioactive glucose in the Δtggt1 strain can be explained by impaired glycolysis, a significant decline in glutamine usage is intriguing. To test whether such a regression was caused by a systemic shutdown of protein synthesis in the mutant due to an compromised flow of carbon, we labeled tachyzoites with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (Fig. 5D). As anticipated, protein synthesis in intracellular and extracellular parasites corresponded to their metabolically active and quiescent nature, respectively. More importantly, all three strains exhibited a comparable inclusion of radioisotopes into nascent protein pools during extracellular as well as intracellular stages. In accord with a comparable protein synthesis, protein contents of the strains were also equivalent (Fig. 5E). The observed decline in glutamine labeling of the Δtggt1 mutant, therefore, appears to be a consequence of metabolic rewiring aimed at accommodating the energy demands of extracellular parasites.

The Δtggt1 Mutant Displays a Defective Biogenesis of Lipids

We next analyzed the contributions of glucose and glutamine for lipogenesis in extracellular tachyzoites. Similar to the RNA and protein pools, we observed a considerable labeling of lipids with radioactive glucose in the parental and complemented strains, which indicated influx of sugar-derived carbon (e.g. glycerol-3-phosphate, fatty acids) for the membrane biogenesis (Fig. 6A). Labeling was nearly absent in the Δtggt1 strain, as predicted by glycolytic defects. No obvious inclusion of glutamine into lipids was detected in any of the three strains, which ruled out its possible contribution to lipid synthesis and signified a lack of counteracting mechanism to sustain lipid biogenesis in the Δtggt1 strain. To further examine the observation, we quantified three major phospholipids by chemical phosphorous assays. Indeed, we found a statistically significant ≈20% decrease in phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn; Fig. 6B, supplemental Fig. S8). To confirm whether such declines were caused by defective syntheses of indicated lipids in the mutant, we performed metabolic labeling with corresponding head groups ([14C]choline, [14C]ethanolamine, [14C]serine) as reported in our earlier work (17). Whereas choline and ethanolamine are used to produce phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine, respectively, serine is adeptly utilized to synthesize both phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine (17, 33). Indeed, radiolabeling with two of three major precursors of phospholipid synthesis (choline and serine) was decreased in the Δtggt1 strain (Fig. 6C). The mutant also showed declines in the predominant species of triacylglycerol (Fig. 6D) as determined by lipidomics analyses. A comparative estimate of fatty acids bound to all membrane lipids present in the Δtggt1 strain revealed an apparently specific regression in long chain fatty acids (26:1, 22:1; Fig. 6E). These results together showed an important role of glycolysis in lipogenesis and implied a deficit of glucose-derived acetyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis in the mutant.

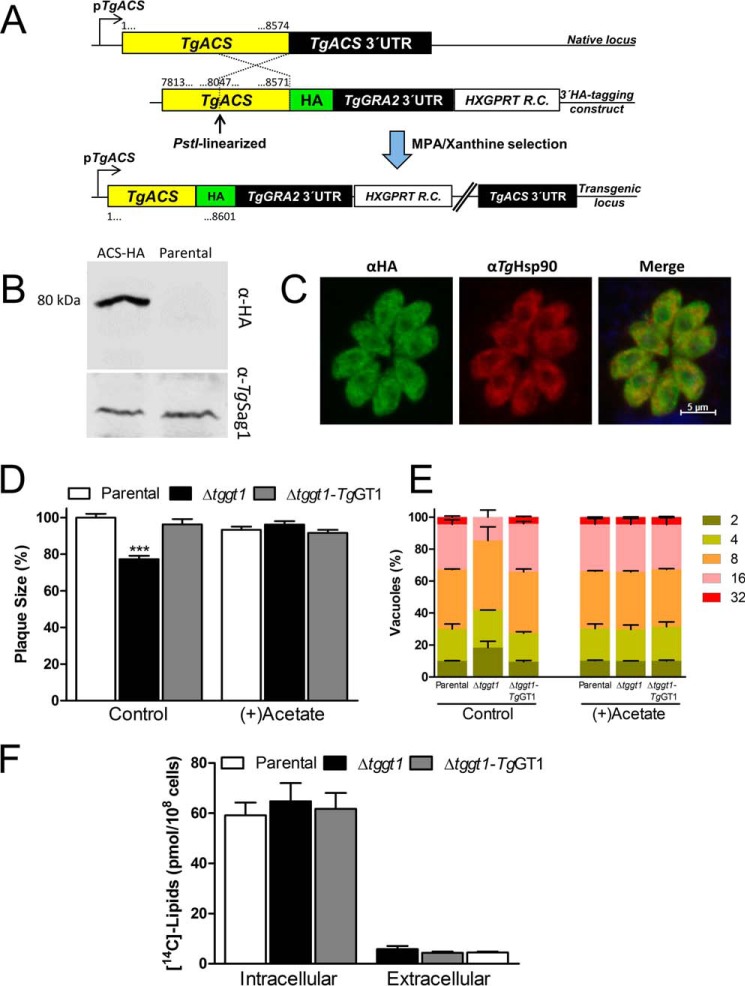

Acetate Supplementation Can Amend the Phenotypic Defects in the Δtggt1 Mutant

It has been shown previously that tachyzoites can incorporate acetate, particularly into long chain fatty acids produced by elongase (and/or FAS1?) pathways (34, 35). Accordingly, our bioinformatics search identified a putative acetyl-CoA synthetase (TgACS) in the parasite database (ToxoDB). We performed 3′-genomic tagging of TgACS protein with a C-terminal HA epitope (Fig. 7A). Expression of TgACS-HA in the eventual transgenic strain was regulated by its native promoter and TgGRA2–3′-UTR. Immunoblot analysis revealing a single band of expected size (about 80 kDa) confirmed the protein integrity and endogenous expression of TgACS in tachyzoites (Fig. 7B). Immunofluorescence assays showed a predominantly cytosolic expression of the epitope-tagged protein in intracellular tachyzoites, which co-localized with a known cytosolic marker TgHsp90 (Ref. 16; Fig. 7C). We next compared the influence of exogenous acetate on the plaque and replication phenotypes of all strains (Fig. 7, D and E). Consistent with reduced plaque size in regular (acetate-free) medium, the Δtggt1 strain replicated slower, as discerned by a higher fraction of smaller vacuoles compared with the control strains. Both phenotypic defects were entirely restored in the Δtggt1 mutant cultured with acetate (Fig. 7, D and E). Labeling of parasites with radioactive acetate demonstrated a significant incorporation into lipids of all three strains, with intracellular parasites showing an expectedly higher inclusion of isotope (Fig. 7F). In agreement with its recovered growth and replication, the Δtggt1 mutant assimilated as much isotope as the parental and complemented strains. These results show that a dysfunction of glycolysis impairs lipogenesis, which compromises the lytic cycle of T. gondii in standard cultures lacking acetate. The data also show a flexible use of available nutrients by the parasite.

FIGURE 7.

Growth impairment in the Δtggt1 mutant is restored by acetate supplementation. A, schematic illustration of epitope-tagging for expressing TgACS-HA under the control of its native promoter and TgGRA2–3′-UTR. The construct for 3′-HA tagging of the TgACS gene was transfected and drug-selected in the RHΔku80-hxgprt− strain. B, immunoblot of transgenic (expressing TgACS-HA) and parental strains using α-HA and α-TgSag1 (loading control) antibodies. C, immunofluorescent localization of TgACS-HA protein in intracellular tachyzoites. Parasitized cells (24 h infection) were immunostained with α-HA and α-TgHsp90 (cytosolic marker) antibodies. D, plaque growth of the designated parasite strains cultured in standard culture medium with or without 2 mm acetate (7 days, 37 °C, 5% CO2). Plaques were stained with crystal violet before ImageJ analysis (mean ± S.E., n = 3). Statistical significance (Student's t test) was measured separately for each group with respect to the parental strain (***, p < 0.001). E, replication rates of the three parasite strains cultured in the absence or presence of 2 mm acetate. Parasitized fibroblasts (24 h infection) were immunostained with αTgGap45, and the parasitophorous vacuoles were scored for the parasite numbers (mean ± S.E., n = 3). F, radiolabeling of total parasite lipids using [U-14C]acetate. Extracellular or intracellular tachyzoites were incubated with the radioisotope for 4 h (37 °C, 5% CO2), followed by scintillation counting of lipid fractions isolated from purified parasites (mean ± S.E., n = 3). MPA, mycophenolic acid; R.C., resistance cassette.

Discussion

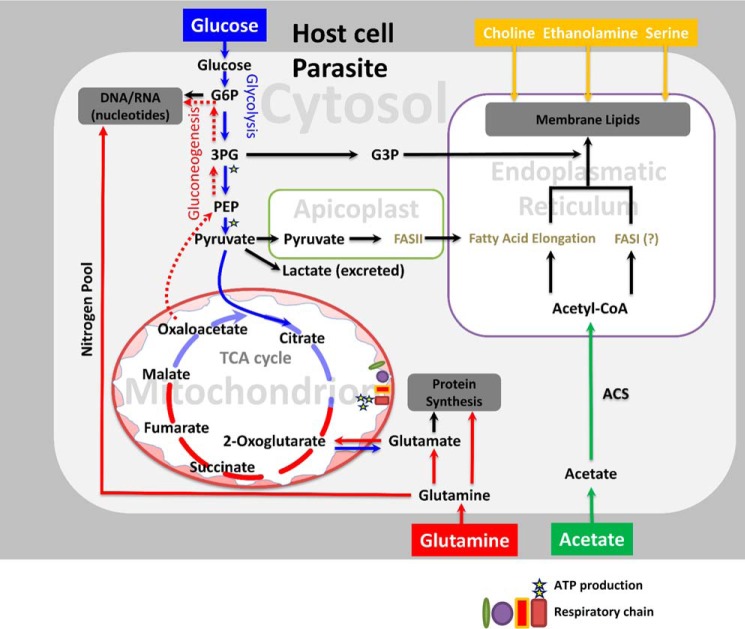

T. gondii is an obligate parasite that can infect and replicate in nearly all nucleated cells of an exceptionally wide range of host organisms. Asexual growth of this parasite involves successive rounds of lytic cycles, which comprise invasion, replication, egress, and reinvasion of neighboring host cells. We show that glucose and glutamine together furnish a major fraction of biomass and energy in a co-regulated manner (Fig. 8), and such a cooperative metabolism is critical to realize a successful lytic cycle of T. gondii in human cells. The facts that the parasite can endure a dearth of either nutrient and continues to replicate even without these two major carbon sources reflects an unparalleled metabolic plasticity in T. gondii given its evolutionary adaptation to obligate intracellular parasitism. Furthermore, tachyzoites rewire the central carbon metabolism during extracellular and intracellular stages according to their low and high bioenergetic demands, respectively. Last but not least, the parasite is competent in utilizing acetate when available, which can override the glycolytic defect. Not only do all these features ensure the survival of extracellular and intracellular states, but they may also underlie the parasite growth in variable milieus encountered in distinct host-cell types.

FIGURE 8.

Carbon metabolism of T. gondii converges with tumor cells. Proposed model of central carbon metabolism is constructed based on this work, published literature, and annotations of select enzymes expressed in the tachyzoite stage (ToxoDB). Only those metabolites detectable or relevant to this work are shown for simplicity. Glucose and glutamine are co-utilized to satisfy the demands of biomass (proteins, nucleotides, lipids), energy, and reducing equivalents (not depicted). Nucleotides synthesis requires ribose 5-phosphate produced by diversion of glycolytic metabolites to the pentose phosphate shunt. Lipid biogenesis utilizes acetyl-CoA and glycerol-3-phosphate, which are primarily derived from glucose under normal condition. Likewise, protein synthesis needs glucose-derived amino acids. When replicating intracellular, glutamine catabolism enables an efficient biosynthetic use of glucose by replenishing the TCA cycle metabolites drained by biogenesis of macromolecules. Glutamine also confers the much-needed pool of nitrogen for nucleotide and protein syntheses. Extracellular parasites can use either of the two nutrients to produce sufficient energy for the host-cell invasion. Glutamine-derived carbon flux (TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis) sustains the parasite survival with a minimal growth defect when glycolysis is compromised. The parasite can also deploy acetate as a carbon source when available in culture. Carbon metabolism is reprogrammed according to proliferating (intracellular) and non-proliferating (extracellular) demands and in response to the available nutrients. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; G3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Extracellular parasites strictly depend on glucose and/or glutamine to invade host cells, likely because the extracellular milieu lacks any other substitutive nutrients, which can operate glycolysis and/or TCA cycle adequately enough to facilitate the invasion process. Intriguingly, despite a substantially reduced ATP in the Δtggt1 strain, the parasite invasion was not affected in normal medium. A pharmacological inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation or absence of glutamine severely compromised the process in the mutant even though the ATP pool was not ablated. It appears as though a threshold level of energy is required by extracellular parasites and/or another factor (e.g. redox state) plays a key role in sustaining the process of invasion. Unlike energy, the protein and RNA contents of the Δtggt1 mutant were surprisingly normal, implying a flexible usage of compensatory nutrients during its proliferation phase. Indeed, intracellular parasites exhibited a much greater resilience possibly by exploiting host-derived glycolytic intermediates and amino acids. The observed metabolic plasticity in response to nutritional cues appears to ensure the lytic cycle with a minimal trade-off in tachyzoite growth.

We have previously shown that extracellular parasites can actively assemble phospholipids (17, 33) even though they seem unable to synthesize acyl chains (7, 34). Here, we show that unlike glucose, glutamine does not adequately support lipogenesis, resulting in a wide-spectrum deficit of lipids upon impairment of glycolysis. It appears as though synthesis of acyl chains becomes limited in the mutant deficient in glucose import. In T. gondii, acetyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis can be derived via multiple sources, including pyruvate dehydrogenase located in the apicoplast (3), branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase in the mitochondrion (8), and ATP-citrate lyase and acetyl-CoA synthetase in the cytosol ((36), this work). The latter two proteins are genetically redundant and synthetically lethal for the parasite (36), and therefore appear to be functionally redundant with each other. Although the role of citrate for fatty acid synthesis remains to be explored, acetate is efficiently utilized by elongase (and FAS1?) to produce long acyl chains in the parasite ER (34), which resonates with the expression of acetyl-CoA synthetase in tachyzoites and restoration of lipogenesis by acetate in the Δtggt1 mutant. Acetate is not used in routine parasite cultures; it is however present in the human blood with its concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 0.18 mm (37, 38). Besides, acetate has been shown to be utilized as a carbon and/or energy source in astrocytes and neurons (39–42). The natural occurrence and utilization of acetate may be relevant to in vivo development and pathogenesis of T. gondii. Future work on acetate metabolism should reveal the physiological importance and mutual regulation of acetyl-CoA pools in T. gondii.

Over the last decade, a consistent picture of carbon metabolism has emerged from studies on diverse types of proliferating cells (tumors, stem cells, lymphocytes), whose metabolic requirements are different from differentiated (quiescent) cells (43, 44). Proliferating cells must continually produce major constituents of biomass (nucleic acids, proteins, membranes). Most quiescent cells, however, are relieved of such liabilities and reduce their carbon flux to promote maintenance and survival. Metabolic demands of differentiated cells are primarily met by glucose, most of which (>90%) enter the TCA cycle as pyruvate, and only a small fraction (<10%) is converted to lactate (45). Most dividing cells instead require a rapid glycolysis along with lactate production and glutamine catabolism. At first glance, such a carbon flux seems rather inefficient for making ATP and the waste of three carbons as lactate; however, it confers a much-needed benefit to the dividing cells by routing glycolytic and TCA cycle metabolites for making macromolecules. Moreover, two recent studies (46, 47) show that several types of cancer cells fuel biogenesis by avidly consuming acetate. Notably, parasites appear to show a similar metabolic phenotype. We demonstrate that co-usage, quintessence (tangible metabolic benefits), and cooperation of glucose, glutamine, and acetate in T. gondii resemble the physiology of tumor cells. Such a metabolic convergence might eventually be exploited to develop common therapeutics targeting the parasite and cancer metabolism.

Author Contributions

R. N. and V. Z. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments and wrote the paper. R. L. contributed analytical tools/reagents. N. G. conceived, designed, and coordinated the study, analyzed experiments, and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Kempa (Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin) for initial metabolomics studies, and Martin Blume, Emanuel Heitlinger and Grit Meusel (Humboldt University) for methodical and technical contributions to this work. We also thank Vern Carruthers (University of Michigan), Boris Striepen (University of Georgia), Dominique Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva, Switzerland), Jean-Francois Dubremetz (University of Montpellier, France), Sergio Angel (National University of San Martín, Argentina) and John Boothroyd (Stanford School of Medicine) for sharing biological reagents.

The work was supported by German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) Grants GRK1121/A7 and GU1100/3-1 (to N. G.). The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest pertaining to this work.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S8

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) KR013277.

- GT1

- glucose transporter 1

- TCA

- tricarboxylic acid

- ACS

- acetyl-CoA synthetase

- DON

- 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine

- HFF

- human foreskin fibroblasts

- MEM

- minimum Eagle's medium.

References

- 1.Dubey J. P., Lindsay D. S., and Speer C. A. (1998) Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 267–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissinger J. C., Gajria B., Li L., Paulsen I. T., and Roos D. S. (2003) ToxoDB: accessing the Toxoplasma gondii genome. Nucleic acids Res. 31, 234–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleige T., Fischer K., Ferguson D. J., Gross U., and Bohne W. (2007) Carbohydrate metabolism in the Toxoplasma gondii apicoplast: localization of three glycolytic isoenzymes, the single pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, and a plastid phosphate translocator. Eukaryotic cell 6, 984–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleige T., Pfaff N., Gross U., and Bohne W. (2008) Localisation of gluconeogenesis and tricarboxylic acid (TCA)-cycle enzymes and first functional analysis of the TCA cycle in Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 38, 1121–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blume M., Rodriguez-Contreras D., Landfear S., Fleige T., Soldati-Favre D., Lucius R., and Gupta N. (2009) Host-derived glucose and its transporter in the obligate intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii are dispensable by glutaminolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12998–13003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohsaka A., Yoshikawa K., and Hagiwara T. (1982) 1H-NMR spectroscopic study of aerobic glucose metabolism in Toxoplasma gondii harvested from the peritoneal exudate of experimentally infected mice. Physiol. Chem. Phys. 14, 381–384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacRae J. I., Sheiner L., Nahid A., Tonkin C., Striepen B., and McConville M. J. (2012) Mitochondrial metabolism of glucose and glutamine is required for intracellular growth of Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Host Microbe 12, 682–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oppenheim R. D., Creek D. J., Macrae J. I., Modrzynska K. K., Pino P., Limenitakis J., Polonais V., Seeber F., Barrett M. P., Billker O., McConville M. J., and Soldati-Favre D. (2014) BCKDH: the missing link in apicomplexan mitochondrial metabolism is required for full virulence of Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium berghei. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blume M., Nitzsche R., Sternberg U., Gerlic M., Masters S. L., Gupta N., and McConville M. J. (2015) A Toxoplasma gondii gluconeogenic enzyme contributes to robust central carbon metabolism and is essential for replication and virulence. Cell Host Microbe 18, 210–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazumdar J., H Wilson E., Masek K., A Hunter C., and Striepen B. (2006) Apicoplast fatty acid synthesis is essential for organelle biogenesis and parasite survival in Toxoplasma gondii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13192–13197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox B. A., Ristuccia J. G., Gigley J. P., and Bzik D. J. (2009) Efficient gene replacements in Toxoplasma gondii strains deficient for nonhomologous end joining. Eukaryotic cell 8, 520–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huynh M. H., and Carruthers V. B. (2009) Tagging of endogenous genes in a Toxoplasma gondii strain lacking Ku80. Eukaryotic cell 8, 530–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheiner L., Demerly J. L., Poulsen N., Beatty W. L., Lucas O., Behnke M. S., White M. W., and Striepen B. (2011) A systematic screen to discover and analyze apicoplast proteins identifies a conserved and essential protein import factor. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plattner F., Yarovinsky F., Romero S., Didry D., Carlier M. F., Sher A., and Soldati-Favre D. (2008) Toxoplasma profilin is essential for host cell invasion and TLR11-dependent induction of an interleukin-12 response. Cell Host Microbe 3, 77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubremetz J. F., Rodriguez C., and Ferreira E. (1985) Toxoplasma gondii: redistribution of monoclonal antibodies on tachyzoites during host cell invasion. Exp. Parasitol. 59, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Echeverria P. C., Figueras M. J., Vogler M., Kriehuber T., de Miguel N., Deng B., Dalmasso M. C., Matthews D. E., Matrajt M., Haslbeck M., Buchner J., and Angel S. O. (2010) The Hsp90 co-chaperone p23 of Toxoplasma gondii: identification, functional analysis and dynamic interactome determination. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 172, 129–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta N., Zahn M. M., Coppens I., Joiner K. A., and Voelker D. R. (2005) Selective disruption of phosphatidylcholine metabolism of the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii arrests its growth. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16345–16353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K., Soldati D., and Boothroyd J. C. (1993) Gene replacement in Toxoplasma gondii with chloramphenicol acetyltransferase as selectable marker. Science 262, 911–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meissner M., Schlüter D., and Soldati D. (2002) Role of Toxoplasma gondii myosin A in powering parasite gliding and host cell invasion. Science 298, 837–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donald R. G., and Roos D. S. (1993) Stable molecular transformation of Toxoplasma gondii: a selectable dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase marker based on drug-resistance mutations in malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11703–11707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donald R. G., Carter D., Ullman B., and Roos D. S. (1996) Insertional tagging, cloning, and expression of the Toxoplasma gondii hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase gene: use as a selectable marker for stable transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14010–14019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kafsack B. F., Beckers C., and Carruthers V. B. (2004) Synchronous invasion of host cells by Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 136, 309–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lisec J., Schauer N., Kopka J., Willmitzer L., and Fernie A. R. (2006) Gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat. Protoc. 1, 387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung J.-Y., and Oh M.-K. (2015) Isotope labeling pattern study of central carbon metabolites using GC/MS. J. Chromatogr. B. 974, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel J., Segu S., Li Y., Irgang S., Jueppner J., and Giavalisco P. (2011) Ultra performance liquid chromatography and high resolution mass spectrometry for the analysis of plant lipids. Front. Plant Sci. 2, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bligh E. G., and Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith P. K., Krohn R. I., Hermanson G. T., Mallia A. K., Gartner F. H., Provenzano M. D., Fujimoto E. K., Goeke N. M., Olson B. J., and Klenk D. C. (1985) Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouser G., Fkeischer S., and Yamamoto A. (1970) Two dimensional then layer chromatographic separation of polar lipids and determination of phospholipids by phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids 5, 494–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thangavelu K., Chong Q. Y., Low B. C., and Sivaraman J. (2014) Structural basis for the active site inhibition mechanism of human kidney-type glutaminase (KGA). Sci. Rep. 4, 3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vercesi A. E., Rodrigues C. O., Uyemura S. A., Zhong L., and Moreno S. N. (1998) Respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31040–31047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin S. S., Blume M., von Ahsen N., Gross U., and Bohne W. (2011) Extracellular Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites do not require carbon source uptake for ATP maintenance, gliding motility, and invasion in the first hour of their extracellular life. Int. J. Parasitol. 41, 835–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Q., Upadhya R., Zhang H., Madrid-Aliste C., Nieves E., Kim K., Angeletti R. H., and Weiss L. M. (2011) Analysis of the glycoproteome of Toxoplasma gondii using lectin affinity chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Microbes Infect. 13, 1199–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann A., Hellmund M., Lucius R., Voelker D. R., and Gupta N. (2014) Phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis in the parasite mitochondrion is required for efficient growth but dispensable for survival of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 6809–6824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramakrishnan S., Docampo M. D., Macrae J. I., Pujol F. M., Brooks C. F., van Dooren G. G., Hiltunen J. K., Kastaniotis A. J., McConville M. J., and Striepen B. (2012) Apicoplast and endoplasmic reticulum cooperate in fatty acid biosynthesis in apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 4957–4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramakrishnan S., Docampo M. D., MacRae J. I., Ralton J. E., Rupasinghe T., McConville M. J., and Striepen B. (2015) The intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii depends on the synthesis of long chain and very long-chain unsaturated fatty acids not supplied by the host cell. Mol. Microbiol. 97, 64–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tymoshenko S., Oppenheim R. D., Agren R., Nielsen J., Soldati-Favre D., and Hatzimanikatis V. (2015) Metabolic needs and capabilities of Toxoplasma gondii through combined computational and experimental analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skutches C. L., Holroyde C. P., Myers R. N., Paul P., and Reichard G. A. (1979) Plasma acetate turnover and oxidation. J. Clin. Invest. 64, 708–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tollinger C. D., Vreman H. J., and Weiner M. W. (1979) Measurement of acetate in human blood by gas chromatography: effects of sample preparation, feeding, and various diseases. Clin. Chem. 25, 1787–1790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dienel G. A., and Cruz N. F. (2006) Astrocyte activation in working brain: energy supplied by minor substrates. Neurochem. Int. 48, 586–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cerdan S., Künnecke B., and Seelig J. (1990) Cerebral metabolism of [1,2–13C2]acetate as detected by in vivo and in vitro 13C NMR. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 12916–12926 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brand A., Richter-Landsberg C., and Leibfritz D. (1997) Metabolism of acetate in rat brain neurons, astrocytes, and cocultures: metabolic interactions between neurons and glia cells, monitored by NMR spectroscopy. Cell. Mol. Biol. 43, 645–657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waniewski R. A., and Martin D. L. (1998) Preferential utilization of acetate by astrocytes is attributable to transport. J. Neurosci. 18, 5225–5233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lunt S. Y., and Vander Heiden M. G. (2011) Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 441–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T., Marquardt C., and Foker J. (1976) Aerobic glycolysis during lymphocyte proliferation. Nature 261, 702–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vander Heiden M. G., Cantley L. C., and Thompson C. B. (2009) Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comerford S. A., Huang Z., Du X., Wang Y., Cai L., Witkiewicz A. K., Walters H., Tantawy M. N., Fu A., Manning H. C., Horton J. D., Hammer R. E., McKnight S. L., and Tu B. P. (2014) Acetate dependence of tumors. Cell 159, 1591–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mashimo T., Pichumani K., Vemireddy V., Hatanpaa K. J., Singh D. K., Sirasanagandla S., Nannepaga S., Piccirillo S. G., Kovacs Z., Foong C., Huang Z., Barnett S., Mickey B. E., DeBerardinis R. J., Tu B. P., Maher E. A., and Bachoo R. M. (2014) Acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma and brain metastases. Cell 159, 1603–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]