Abstract

Coronary artery aneurysms that occur in 25% of untreated Kawasaki disease (KD) patients may remain clinically silent for decades and then thrombose resulting in myocardial infarction. Although KD is now the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in Asia, the United States, and Western Europe, the incidence of KD in Egypt is unknown. We tested the hypothesis that young adults in Egypt presenting with acute myocardial ischemia may have coronary artery lesions due Kawasaki disease (KD) in childhood. We reviewed a total of 580 angiograms of patients ≤ 40 years of age presenting with symptoms of myocardial ischemia. Coronary artery aneurysms were noted in 46 patients (7.9 %) of whom nine presented with myocardial infarction. The likelihood of antecedent KD as the cause of the aneurysms was classified as definite (n=10), probable (n=29), or equivocal (n=7). Compared to the definite and probable groups, the equivocal group had more traditional cardiovascular risk factors, smaller sized aneurysms, and fewer coronary arteries affected. In conclusion, in a major metropolitan center in Egypt, 6.7% of adults age 40 years or younger undergoing angiography for evaluation of possible myocardial ischemia had lesions consistent with antecedent KD. Because of the unique therapeutic challenges associated with these lesions, adult cardiologists should be aware that coronary artery aneurysms in young adults may be due to missed KD in childhood.

Keywords: Aneurysm, Kawasaki Disease, Ischemic Heart Disease, Coronary Artery Disease, Angiograms, Multi-slice CT

Introduction

To investigate the prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms as a cardiovascular sequel of untreated or missed KD in childhood among young adults in Egypt, we reviewed angiograms of patients under 40 years of age who presented to a university hospital, a private clinic, and a private imaging facility with signs and symptoms of myocardial ischemia.

Methods

Subjects who underwent coronary angiography for evaluation of suspected myocardial ischemia from July 2010 through December 2011 at a university hospital (Kasr El Aini Hospital, Cairo), and had coronary artery aneurysms detected (n=9), were prospectively identified and enrolled after providing informed consent. The total number of patients 40 years of age or younger undergoing invasive coronary angiography at this facility during the same time period was also determined (n=140). The age of 40 years was chosen as an arbitrary cut-off in order to minimize the number of subjects with aneurysms due to atherosclerosis. The study protocol and consents for prospectively enrolled patients were approved by the Ethics Committee of Kasr Al Aini Hospital.

In addition, we retrospectively reviewed all conventional coronary angiograms (n=140) and MSCT scans (n=300) performed at a private, free-standing clinic (Cairo Cath), and a private imaging facility (Alfa Scan) between January 2008 and December 2011 (due to availability of records for this time period only) on patients 40 years of age or younger, with coronary aneurysms noted in their angiograms (n=13 and n=24 respectively). The study protocol for the retrospective review was approved by the Clinical Director of each of the private facilities.

Data collected for each patient included demographic characteristics, medical history, clinical and laboratory data, electrocardiographic, and angiographic findings. A past medical history consistent with acute KD (history of fever > 5 days in childhood associated with rash, conjunctival injection, and periungual desquamation in the convalescent phase) was sought from the patients prospectively enrolled in the study. A history of a KD-compatible illness (e.g. scarlet fever, measles) was also sought. None of the patients had received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment and none had a diagnosis of vasculitis, connective tissue disease, or autoimmune disorders. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors were recorded including fasting lipid levels, smoking history (current, past, never), hypertension (defined as a physician-documented history of high blood pressure), diabetes, and family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) (defined as mother with CAD at age ≤65 years and/or father with CAD at age ≤55 years). Subjects were given a risk factor score based on the number of cardiovascular risk factors present (maximum score = 5).

All 580 angiograms were reviewed by two of the authors (El Said and Rizk). Then angiograms showing coronary aneurysms were reviewed by co-authors Gordon and Daniels who were blinded to the history and risk factors of all patients. Coronary artery aneurysms were confirmed if the internal diameter of the coronary artery segment measured ≥1.5 times that of an adjacent segment. Aneurysms were adjudicated as “definitely attributable to antecedent KD” if the patient had a known history of KD or a KD-compatible illness and the aneurysm location was proximal, and the distal coronary artery segments were angiographically normal. Aneurysms were adjudicated as “probably attributable to antecedent KD” when angiographic findings were as above, but there was no known KD-compatible illness, or prior medical history was unavailable. Aneurysms adjudicated as “equivocal” had diffuse ectasia or distal CAD consistent with atherosclerosis.

Categorical data are presented as percentages; continuous data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges. The equivocal group was compared to the definite and probable groups combined. Non-parametric data were compared using the Mann Whitney test. Categorical data were compared using the Fisher exact test. All p-values are two-sided with values <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 580 angiograms (conventional and multi-slice CT) of patients age 40 years or younger were reviewed from the three centers. Coronary artery aneurysms were reported in 46 cases (7.9%). The majority of patients were male. The most commonly encountered risk factors were smoking followed by dyslipidemia (Table 1). The group adjudicated as equivocal had more traditional cardiovascular risk factors compared to the definite and probable groups combined (p<0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of young adult patients undergoing angiography for evaluation of suspected myocardial ischemia. Only those patients with aneurysms noted in their angiograms were included. Patients were stratified with respect to the likelihood that the aneurysms were due to antecedent KD. P values are for comparison of the definite and probable groups combined versus the equivocal group.

| Characteristic | Definite n = 10 |

Probable n = 29 |

Equivocal n = 7 |

Total n= 46 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 35 (14 – 40) | 39 (25 – 40) | 40 (37 – 40) | 39 (14 – 40) | 0.15 |

|

| |||||

| Male (%) | 10 (100%) | 29 (100%) | 6 (86%) | 45 (98%) | 0.15 |

|

| |||||

| CAD risk factors, n (%) | |||||

| Smoking | 6 (60%) | 14 (48%) | 4 (57%) | 24 (52%) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 3 (10%) | 3 (43%) | 6 (13%) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 8 (28%) | 4 (57%) | 12 (26%) | 0.06 |

| Dyslipidemia | 6 (60%) | 10 (35%) | 5 (71%) | 21 (46%) | 0.22 |

| LDL >130 mg/dl | 3 (30%) | 5 (17%) | 4 (57%) | 12 (26%) | 0.06 |

| HDL <40 mg/dl | 3 (30%) | 8 (28%) | 3 (43%) | 14 (30%) | 0.66 |

| TC >200 mg/dl | 3 (30%) | 5 (17%) | 4 (57%) | 12 (26%) | 0.06 |

| TG >150 mg/dl | 2 (20%) | 5 (17%) | 4 (57%) | 11 (24%) | 0.046 |

| Family history of CAD | 0 | 1 (3%) | 1 (14%) | 2 (4%) | 0.28 |

|

| |||||

| Number of risk factors | 0.04 | ||||

| 0 | 2 (20%) | 9 (31%) | 1 (14%) | 12 (26%) | |

| 1 | 4 (40%) | 7 (24%) | 0 | 11 (24%) | |

| 2 | 4 (40%) | 11 (38%) | 3 (43%) | 18 (39%) | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 1 (14%) | 2 (4%) | |

| 4 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 2 (29%) | 3 (7%) | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

Indications for angiographic evaluation of these 46 patients with aneurysms were as follows: nine had myocardial infarction with elevated troponin-I levels (including five with inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), two with anterior STEMI, and two with non-STEMI) while the remaining patients had angina (23 with unstable angina and 14 with exertional angina either not responding to medical treatment or confirmed by positive stress test).

Of the 46 patients with aneurysms, ten (22%) were adjudicated as definitely due to antecedent KD. All had a history of KD or a KD-compatible illness (history of classic KD that was misdiagnosed in three, scarlet fever in one, and measles in six). One of the three patients with missed KD was a 14 year old male presenting with an anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Seven years previously he had presented with clinical criteria for KD but was misdiagnosed with acute rheumatic fever. Echocardiography at presentation showed no coronary artery abnormalities but a repeat echocardiogram three months later revealed aneurysms of the proximal right and left coronary arteries.

An additional 29 patients had no history of a KD-compatible illness but had aneurysms adjudicated as probably due to antecedent KD based on their proximal location, and angiographically normal distal vessels without changes suggesting atherosclerosis. Of these 29 patients, 24 patients underwent MSCT and 8/24 (33%) had calcification of their aneurysms.

Seven of the 46 patients (15%) were adjudicated as equivocal because their aneurysms were diffuse, with or without significant luminal narrowing suggestive of atherosclerosis. The median size of the largest aneurysm was 9.0 mm (7.0 – 12.0) for the definite group, 7.5 mm (6.5 – 54.0) for the probable group, and 6.5 mm (6.0 – 7.5) for the equivocal group (p=0.03 for the difference between definite and probable groups vs. equivocal group) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Internal diameter of the largest aneurysm stratified by the likelihood of antecedent KD.

Box plot shows median (bar) and interquartile range (box) and 5% and 95% (whiskers).

Comparison by the Mann Whitney test.

Assessmnet of the distribution of coronary arteries affected by aneurysms revealed that the left anterior descending artery was the most commonly affected artery followed by the right coronary artery (Table 2). The distribution of patients with one, two, or three coronary arteries with aneurysms differed by the group classification. Of the ten patients with only one coronary artery affected, five (71%) were classified as equivocal, four (14%) were probable, and only one (10%) was definite. Of the 36 patients with two or more coronary arteries affected, only two (29%) were classified as equivocal, 25 (86%) were probable, and nine (90%) were definite (p=0.003). Giant coronary artery aneurysms (≥ 8 mm) were present in 22 patients (48%), and eight patients (36%) had thrombi in their coronary aneurysms.

Table 2.

The distribution of coronary arteries affected by aneurysms.

| Definite n = 10 |

Probable n = 29 |

Equivocal n = 7 |

Total n = 46 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left main trunk | 1 (10%) | 2 (7%) | 0 | 3 (7%) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 9 (90%) | 29 (100%) | 5 (71%) | 43 (94%) |

| Left circumflex artery | 6 (60%) | 13 (45%) | 1 (14%) | 20 (44%) |

| Right coronary artery | 9 (90%) | 22 (76%) | 4 (57%) | 35 (76%) |

Acute management of the 46 patients was as follows: all patients received aspirin, a β-blocking agent, nitrates, and statins. Patients with hypertension or myocardial infarction also received an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. Six patients underwent percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with stent placement, four had angioplasty alone, and 21 patients were started on oral anticoagulation with warfarin. One patient underwent surgical excision of a 54 mm right coronary artery aneurysm with interposition of a saphenous vein graft (Figure 2); histologic examination of the excised right coronary artery aneurysm revealed moderate degenerative changes with mild hyalinosis and loss of the elastic lamina.

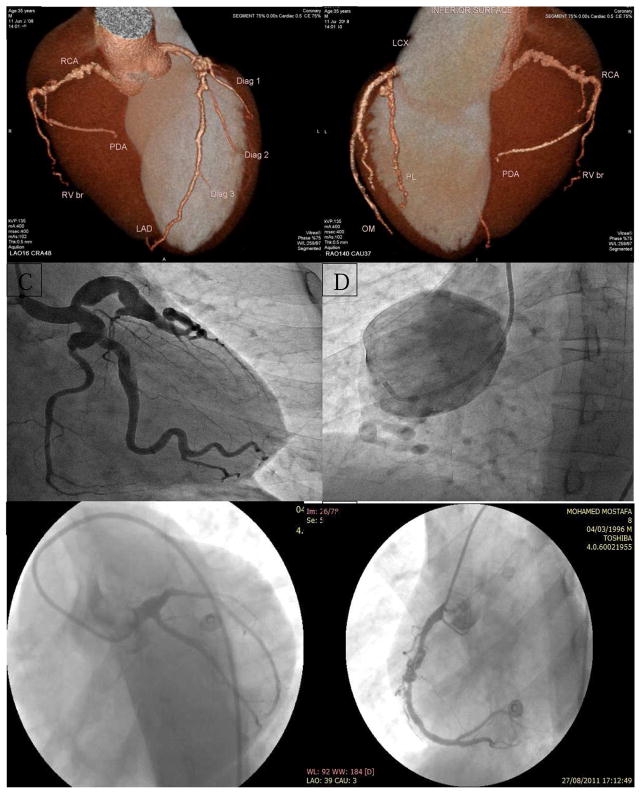

Figure 2.

Examples of angiograms of definite and probable KD cases

A & B. MSCT (reconstructed image) of a 35-year old male patient who presented with unstable angina, showing proximal LAD (9 mm), mid LCX (7 mm), and proximal RCA (7 mm) aneurysms with angiographically normal distal segments.

C & D: Coronary angiogram of a 25-year old male patient presenting with typical chest pain at rest, showing proximal LAD, LCX, and obtuse marginal branch (OMB) aneurysms (left image) and proximal RCA 54 mm aneurysm (right image)

E & F: Coronary angiogram of a 14-year old male patient with history of missed KD in childhood presenting with anterior myocardial infarction, showing proximal LAD total occlusion by a thrombus (left image) and proximal and mid-RCA aneurysms with thrombus in the more distal aneurysm (right image).

Discussion

KD is an acute, self-limited vasculitis of unknown etiology, first described by Tomisaku Kawasaki four decades ago.1 It has replaced acute rheumatic fever as the leading cause of acquired heart disease among children in developed countries.2 In Egypt, where rheumatic fever is still common in childhood, the incidence of KD is unknown. Treatment with IVIG is available only in certain governmental and university hospitals where its cost is subsidized by the government and partly by insurance. However, many patients are not covered by insurance and the co-payment is prohibitive for many families. In the present study, we found that 6.7% of young adults who undergo angiography to evaluate symptoms of suspected myocardial ischemia have coronary artery aneurysms that may be due to antecedent KD. This raises the possibility that KD is not uncommon in Egypt where other pediatric rash/fever illness such as measles, scarlet fever, and acute rheumatic fever are still prevalent. Historically, case definitions were developed to try to differentiate KD from these other, more common diseases including acute rheumatic fever.3

Reports of missed KD in young adults began to emerge following Kawasaki’s original publication and two series, one from Japan and one from the U.S., established that the sequelae of untreated KD in young adults includes myocardial ischemia, infarction, congestive heart failure, and sudden death.4, 5 Reports from around the world suggest that where there are children, there is KD; whether the emergence of KD represents recognition of a new disease or the unmasking of a disease that was hidden in other disease categories in the pre-antibiotic and pre-vaccination era remains unknown.6

Angiographic findings that make antecedent KD likely include proximal aneurysms with or without calcification, associated with angiographically normal distal segments.7 Because a history of KD may be difficult to obtain from young adults who might have been too young to have a personal memory of the illness, recent guidelines from Japan recommend that patients with acute coronary syndromes and aneurysms be diagnosed as having sequelae of KD if other conditions causing aneurysms such as collagen vascular disease are excluded.8 Based on our study, clinical characteristics that make antecedent KD more likely include fewer traditional cardiovascular risk factors, aneurysms in more than one coronary artery, and the presence of giant coronary artery aneurysms. The majority of cases in our series were men and KD is known to have a male predominance with more severe outcomes in male children.9, 10 Smoking has been noted as a prominent risk factor among young adults with a history of KD presenting with myocardial infarction, which suggests a possible acceleration of ischemic complications in this subset of KD patients.10 In recent years, smoking in Egypt has reached an historic high with an estimated 40% of young males smoke according to European Research Council (ERC) Statistics International done in 2001.11 Consistent with the high prevalence of smoking in Egypt, 52% of patients in the present series had a history of smoking. Dyslipidemia was also found to be a prominent additional risk factor, with low HDL being the most common lipid abnormality present in 30% of patients. Of interest, children with KD have also been noted to have low HDL levels during the sub-acute and convalescent phase of their illness.12

To our knowledge, this is the first study in the Middle East to systematically evaluate a population of young adults undergoing coronary angiography to estimate the prevalence of missed KD as a potential contributing factor. In Japan, the country with the highest incidence of KD, Kato et al. surveyed adult cardiologists and retrospectively identified 130 patients ages 20 to 63 with angiographic and clinical findings suggestive of KD.4 Although a definite history of KD was elicited in only two patients, the authors concluded that all 130 patients were likely to have had KD as the cause of their cardiovascular abnormalities. A similar study was conducted by Daniels et al., who evaluated a similar population of young adults from the U.S. and found that approximately 5% had findings consistent with antecedent KD.13

Our findings have important implications for adult cardiologists. The pathology of coronary lesions in patients with KD vasculopathy is very different from the pathology of typical coronary atherosclerosis and so optimal treatment is also different.14, 15 While typical atherosclerosis is characterized by lipid-laden macrophages, extracellular lipid droplets, and cholesterol crystals, these are not the features of coronary lesions after KD;16 and this was revealed by the histologic examination of the resected giant RCA aneurysm.

We recognize several strengths and limitations to the present study. The large number of cases from diverse centers that included both university (public) and private facilities makes it likely that our study encompassed a representative population in Egypt without specific biases. The retrospective nature of some of the data collection has all the limitations inherent in a retrospective study design. Recall bias is a possibility as a history of KD may be difficult to obtain from young adults who may have been too young to have a personal memory of the illness and their parents were not available. Limited availability of older medical records in Egypt prevented us from studying trends in aneurysm rates over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elizabeth Barrett-Connor MD, PhD, for helpful discussion and Yuichiro Sato MS for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by grants from the American Heart Association, National Affiliate (LBD); the National Institutes of Health, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (JCB; RO1-HL69413); the Macklin Foundation (LBD and JCB); and Al-Alfi Foundation for Human and Social Development.

We also thank Cairo Cath & Alfa Scan for giving us access to their records.

Footnotes

This work presented in part as an abstract at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting, held on March 29–31, 2014.

Conflicts of interest: None to be declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (mlns) prevailing in japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taubert KA, Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Nationwide survey of Kawasaki disease and acute rheumatic fever. J Pediatr. 1991;119:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushner HI, Bastian JF, Turner CH, Burns JC. Rethinking the boundaries of Kawasaki disease: Toward a revised case definition. Perspectives in biology and medicine. 2003;46:216–233. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato H, Inoue O, Kawasaki T, Fujiwara H, Watanabe T, Toshima H. Adult coronary artery disease probably due to childhood Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1992;340:1127–1129. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93152-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns JC, Shike H, Gordon JB, Malhotra A, Schoenwetter M, Kawasaki T. Sequelae of Kawasaki disease in adolescents and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns JC, Kushner HI, Bastian JF, Shike H, Shimizu C, Matsubara T, Turner CL. Kawasaki disease: A brief history. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E27. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon JB, Kahn AM, Burns JC. When children with Kawasaki disease grow up: Myocardial and vascular complications in adulthood. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1911–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of cardiovascular sequelae in Kawasaki disease (jcs 2008)--digest version. Circ J. 2010;74:1989–2020. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-74-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudo D, Monobe Y, Yashiro M, Sadakane A, Uehara R, Nakamura Y. A case-control study of giant coronary aneurysms due to Kawasaki disease: The 19th nationwide survey. Pediatr Int. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuda E, Abe T, Tamaki W. Acute coronary syndrome in adult patients with coronary artery lesions caused by Kawasaki disease: Review of case reports. Cardiology in the young. 2011;21:74–82. doi: 10.1017/S1047951110001502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Last accessed 19 September 2014]; www.who.int/tobacco/media/en/Egypt.pdf.

- 12.Newburger JW, Burns JC, Beiser AS, Loscalzo J. Altered lipid profile after Kawasaki syndrome. Circulation. 1991;84:625–631. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniels LB, Tjajadi MS, Walford HH, JimenezFFernandez S, Trofimenko V, Fick DB, Jr, Phan HA, Linz PE, Nayak K, Kahn AM, Burns JC, Gordon JB. Prevalence of Kawasaki disease in young adults with suspected myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2012;125:2447–2453. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuda E, Matsuo M, Naito H, Noguchi T, Nonogi H, Echigo S. Clinical features in adults with coronary arterial lesions caused by presumed Kawasaki disease. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:84–89. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suda K, Kudo Y, Higaki T, Nomura Y, Miura M, Matsumura M, Ayusawa M, Ogawa S, Matsuishi T. Multicenter and retrospective case study of warfarin and aspirin combination therapy in patients with giant coronary aneurysms caused by Kawasaki disease. Circ J. 2009;73:1319–1323. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]