Abstract

Background

Cerclage therapy is an important treatment option for preterm birth prevention. Several patient populations benefit from cerclage therapy including patients with a classic history of cervical insufficiency; patients who present with advanced cervical dilation prior to viability; and patients with a history of prior preterm birth and cervical shortening. Although cerclage is an effective treatment option in some patients, it can be associated with limited efficacy and procedure complications. Development of an alternative to cerclage therapy would be an important clinical development. Here we report on an injectable, silk protein-based biomaterial for cervical tissue augmentation. The rationale for the development of an injectable biomaterial is to restore the native properties of cervical tissue. While cerclage provides support to the tissue, it does not address excessive tissue softening, which is a central feature of the pathogenesis of cervical insufficiency. Silk protein-based hydrogels, which are biocompatible and naturally degrade in vivo, are suggested as a platform for restoring the native properties of cervical tissue and improving cervical function.

Objective

We sought to study the properties of an injectable, silk-based biomaterial for potential use as an alternative treatment for cervical insufficiency. These biomaterials were evaluated for mechanical tunability, biocompatibility, facile injection and in vitro degradation.

Study Design

Silk protein solutions were crosslinked by an enzyme catalyzed reaction to form elastic biomaterials. Biomaterials were formulated to match the native physical properties of cervical tissue during pregnancy. The cell compatibility of the materials was assessed in vitro using cervical fibroblasts, and biodegradation was evaluated using concentrated protease solution. Tissue augmentation or bulking was demonstrated using human cervical tissue from non-pregnant hysterectomy specimens. Mechanical compression tests measured the tissue stiffness as a function of the volume of injected biomaterial.

Results

Silk protein concentration, molecular weight and concentration of crosslinking agent were varied to generate biomaterials that functioned from hard gels to viscous fluids. Biomaterials which matched the mechanical features of cervical tissues were chosen for further study. Cervical fibroblasts cultured on these biomaterials were proliferative and metabolically active over 6 days. Biomaterials were degraded in protease solution, with rate of mass loss dependent on silk protein molecular weight. Injection of cervical tissue samples with 100 μL of the biomaterial resulted in a significant volume increase (22.6% ± 8.8%, p<0.001) with no significant change in tissue stiffness.

Conclusion

Cytocompatible, enzyme-crosslinked silk protein biomaterials show promise as a tissue bulking agent. The biomaterials were formulated to match the native mechanical properties of human cervical tissue. These biomaterials should be explored further as a possible alternative to cerclage for providing support to the cervix during pregnancy.

Keywords: Cervical shortening, cervical tissue bulking, hydrogels, preterm birth, silk protein

Introduction

Annually, more than one million newborns die worldwide as a direct consequence of prematurity.1 Preterm infants that survive are at risk for significant long-term morbidity including visual and hearing impairment,2–4 lung disease,5 and neurodevelopmental abnormalities.6–9 Although preterm birth is a multifactorial disorder,10,11 a dysfunctional cervix is prominent in many cases of spontaneous preterm birth. A short cervix measured in the midtrimester is associated with increased risk of subsequent preterm birth, with the shortest cervix conferring the highest risk.12 Cervical shortening occurs at a faster rate in women destined to deliver preterm; this rate is the same regardless of the ultimate phenotype of preterm birth.13 Indeed, clinical guidelines from the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine recommend serial cervical length measurements for all women with a history of preterm birth to determine who may benefit from cerclage therapy.14–16

Cerclage is an important treatment option for women with cervical insufficiency.17–19 Several patient populations benefit from cerclage therapy including patients with a classic history of cervical insufficiency;20 patients who present with advanced cervical dilation prior to viability;21,22 and patients with a history of prior preterm birth and cervical shortening.23 Although cerclage has shown benefit in these patient populations, it also has limitations. Cerclage can be associated with difficult removal and cervical laceration.24 In addition, many women with cerclage deliver preterm.23 The successful development of a therapeutic alternative to cerclage would be an important clinical development.

We have previously reported on injectable, silk protein-based biomaterials for cervical tissue augmentation.25,26 The rationale for the development of an injectable biomaterial is to restore the native properties of cervical tissue. While cerclage provides support to the tissue, it does not address excessive tissue softening, which is a central feature of the pathogenesis of cervical insufficiency.27 Silk fibroin is a naturally derived, fibrous protein which is non-immunogenic and FDA-approved for reconstructive surgery. Furthermore, the processing capabilities of silk allow for the formation of a versatile set of material formats, such as films, hydrogels and sponges.28 Silk hydrogels are particularly appealing for their tunable mechanics and capacity to serve as carriers for growth factors and therapeutics. Our earlier prototypes of silk hydrogels for cervical augmentation had certain drawbacks, such as gels being significantly stiffer than native cervical tissue, or requiring exogenous ethanol to initiate the gelation mechanism.25,26 We have recently discovered a relatively simple method of enzymatically catalyzing crosslinks between silk protein chains to produce an elastomeric hydrogel that mimics the native mechanical features of cervical tissue without the use of ethanol.29

The goal of this study was to investigate the potential of an injectable, silk biomaterial to act as a bulking agent for cervical tissue, increasing tissue volume without causing excessive stiffening. Silk biomaterial formulations were assessed for mechanical properties, facile injection, cytocompatibility and in vitro degradation. We hypothesized that the silk biomaterials would be biocompatible with cervical fibroblasts, and that injection into cervical tissue would cause bulking without significantly increasing tissue stiffness.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Silk Fibroin Solution and Enzymatically Crosslinked Hydrogels

Silk fibroin protein was purified as we have previously described.25 Briefly, Bombyx mori cocoons were extracted for 10, 30 or 60 minutes to remove the sericin coating from the fibroin fibers. Increasing the extraction time reduces the molecular weight of silk peptides.30 10 min, 30 min and 60 min fibers were rinsed in deionized water, dissolved in a 9.3 M LiBr solution and dialyzed against water for 72 hours to remove LiBr. Enzymatically crosslinked hydrogels were prepared as previously described.29 Silk solutions were diluted to three different concentrations: 3%, 5% and 7% (w/v). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP), type VI lyophilized powder (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was reconstituted in deionized water and added to the silk solution in a ratio of 10, 5 or 2.5 U HRP to 1 mL of silk solution. Gelation was initiated by adding 10 μL of a 1.25%, 1.0% 0.5% or 0.25% (v/v in water) hydrogen peroxide solution per 1 mL of silk-HRP (final H2O2 molarity 4.08, 3.27, 1.63, 0.82 mM, respectively). Gels were allowed to set at room temperature for 2 hours. For cell seeding studies, all materials were sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter before gelation.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis of Silk-HRP Hydrogels

The mechanical properties of the silk-HRP hydrogels were tested via unconfined compression and compared to the mechanical characteristics of native cervical tissue.31 Hydrogels were equilibrated overnight in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) for 12 hours prior to mechanical testing. Samples (8 mm diameter, 5 mm height) were loaded onto a TA Instruments RSA3 Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) between stainless steel parallel plates in an immersion chamber containing fresh DMEM. A preload of 2 grams was used to ensure proper contact with the sample.

Each hydrogel was subjected to two different unconfined compression modes: load-unload cycles and ramp-relaxation. Each hydrogel was initially loaded to 40% axial strain and unloaded back to 0% strain at a constant rate of 1 mm/sec. This cycle was repeated four times total, with data reported for the final cycle. After re-equilibration in DMEM for 30 minutes, each hydrogel was subjected to unconfined ramp-relaxation to axial strain levels of 10%, 20% and 30% with a ramp rate of 1 mm/sec. Each strain level was held for 30 minutes to measure the relaxation response of the material.

In Vitro Degradation by Protease XIV

Mass loss induced by proteolytic degradation was determined by incubating hydrogels in protease XIV.32 Lyophilized protease XIV powder (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was reconstituted to 0.1 U/mL in 1X PBS with continuous stirring for one hour. Hydrogels were incubated in 500 μL protease solution for 6 days. Each day, one set of samples was removed, washed in deionized water for 24 hours and lyophilized before mass measurement.

Cervical Fibroblast Culture, Biocompatibility and Proliferation

Cervical biopsies were acquired from premenopausal women after hysterectomy for benign indications, as described previously.33 Institutional review board approval (IRB# 8315, approved 7/25/2007) and informed consent were obtained prior to study initiation. Cells were isolated via explant culture method. Cells from passage 2 to 4 were used for all experiments. DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic was used as standard medium. Cervical fibroblasts were cultured on the surface of sterile, pre-formed silk hydrogels and compared to cell responses on tissue culture plastic (TCP). Cellular viability was determined by a LIVE/DEAD viability/cytotoxicity kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), cell metabolic activity by alamarBlue reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and cell proliferation by Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

For cell viability and metabolic activity, cells were applied to the surface of silk hydrogels at 20,000 cells/cm2 in standard medium. Time points were taken at 2, 4 and 6 days. For cell viability, wells were sacrificed and incubated in calcein AM (1 μmol/L) and ethidium bromide (2 μmol/L) for 30 minutes at 37°C and visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope (AxioVert S100, Carl Zeiss, Germany). For metabolic activity, wells were incubated in 1X alamarBlue solution for 4 hours at 37°C, and fluorescence was read at 560/590 nm excitation/emission. For cell proliferation tests, cells were seeded onto sterile gels at 5000 cells/cm2. Wells were frozen at −20°C for 12 hours and lyophilized to lyse cells. The supernatant from solubilized freeze-dried scaffolds was quantified by PicoGreen assay. For all tests, silk hydrogels without cells were used as controls.

In Vitro Bulking by Injection into Human Cervical Tissue

Cervical tissue specimen were extracted from patients after hysterectomy (N = 3) and tested on the same day as the procedure. Institutional review board approval (IRB# 8315, approved 7/25/2007) and informed consent was obtained. After removal of cervix and uterus, a portion of the cervix between the internal and external os was removed and stored in cold saline. Two samples from each patient tissue were removed using a 10 mm biopsy punch and cut to a height of 5 mm. Silk hydrogel was injected via a 21G, 12.7 mm length needle, and tissue volume and mechanics were assessed as a function of injected silk hydrogel volume.

Injected explants were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin-embedded. Sample sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to visualize presence of silk gel within the tissue and imaged using a Zeiss AxioVert 40 CFL microscope and a 10X objective (Carl Zeiss AG, Germany).

Injection Profile Analysis

Mechanical testing was performed to determine the force required for injection of silk hydrogels through a 21G needle. 1 mL of silk-HRP solution with hydrogen peroxide was loaded into a 1 mL Leur-lock syringe with 21G, 12.7 mm length needle and left at room temperature for 2 hours to set. Injection tests were performed on an Instron 3366 (Norwood, MA, USA) with an attached 100 N load cell. After gelation, the syringes were vertically mounted onto a custom platform and compressive force was applied to the plunger at a clinically relevant rate of 1 mm/sec (approximately 1 mL/min extrusion rate).

Statistics

Hydrogel peak and relaxation stresses were reported as the average and standard deviation of N=4. Mass loss was reported as the average and standard deviation of N=5 per time point, and significance determined by two tailed t-test with p<0.05. Cell proliferation (N=5), metabolic activity (N=5) and cervical tissue bulking (N=2 per patient, three patients) data reported as average and standard deviation with significance determined by 1-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc analysis for p<0.01 (in vitro cell culture) and p<0.05 (tissue bulking). Injection force reported as average force over 30 seconds of injection for N=1.

Results

Mechanical Analysis of Silk Biomaterials

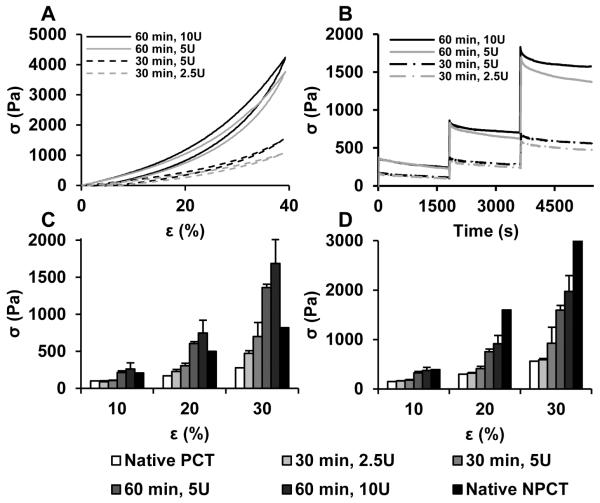

108 different silk biomaterial formulations (SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S1) were screened for rapid gelation (< 2 hours) and mechanical properties comparable to previously published values for pregnant and non-pregnant cervical tissue.31 By altering the silk composition and crosslinker concentration, hydrogels with a range of mechanical properties were formed. Optimized hydrogel formulations (FIGURE 1, TABLE 1) which best recapitulated the stress-strain profile (Figure 1A) and compressive stress-relaxation profiles (Figure 1B) of native cervical tissue were chosen for analysis. These formulations demonstrate high elasticity as indicated by recovery from 40% compressive strain with minimal hysteresis. The relaxation and peak stresses (Figures 1C, 1D), which partially define the mechanical behavior of materials under an applied force, are within the range of native pregnant and non-pregnant cervical tissue. These hydrogels were slightly stiffer than pregnant cervical tissue yet softer than non-pregnant tissue, making them ideal for bulking and support. Mechanical features were similar between hydrogel formulations 1 & 2 and 3 & 4, therefore, only formulations 1 and 3 were chosen for further analysis based on their lower HRP content.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanical characterization of silk hydrogels. A) stress-strain profiles; B) stress-relaxation curves at 10, 20 and 30% strain; C) peak stress, and D) relaxation stress of silk hydrogels compared to pregnant and non-pregnant cervical tissues.31 PCT = pregnant cervical tissue; NPCT = non-pregnant cervical tissue; σ = mechanical stress; ε = mechanical strain.

Table 1.

Optimized Silk Hydrogel Formulations

| Parameter | Formulation 1 | Formulation 2 | Formulation 3 | Formulation 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silk Extraction (min) | 30 | 30 | 60 | 60 |

| Silk Conc. (w/v %) | 5.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| HRP Conc. (U/mL) | 2.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 10 |

| H2O2 Conc. (mM) | 0.82 | 0.82 | 1.63 | 1.63 |

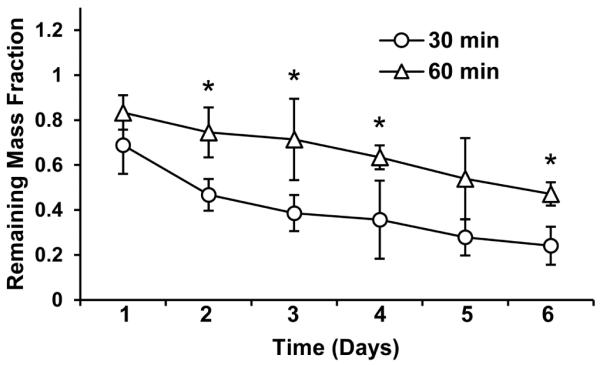

In Vitro Degradation by Protease XIV

Degradation of silk fibroin biomaterials has previously been studied using protease XIV.34–36 In the presence of 0.1 U/mL protease XIV, silk hydrogels from either 30 or 60 min extracted silk stock degraded rapidly, losing over 50% mass after six days (FIGURE 2). The hydrogel from 30 min extracted silk lost significantly more mass after six days compared to the 60 min extracted silk (75.9% ± 8.4% vs. 52.8% ± 5.2%, p=0.0005), indicating tunable control of degradation rate based on the hydrogel formulation.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro degradation of silk hydrogels in concentrated protease solution. The two hydrogel formulations show significant differences in hydrogel mass loss over 6 days. * = p<0.05

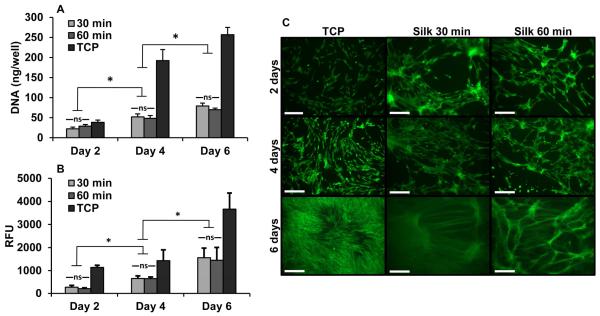

Cervical Fibroblast Culture, Biocompatibility and Proliferation

In vitro cervical fibroblast survival studies were performed in 2D culture on pre-formed silk hydrogels. Fibroblasts seeded on both 30 and 60 minute boil silk hydrogels were proliferative and metabolically active over 6 days of culture (FIGURE 3). No significant difference was seen in cell responses between the two gels. However, the gels showed significantly decreased proliferation and decreased metabolic activity compared with tissue culture plastic (proliferation: p< 0.05; metabolic activity: p<0.001; all time points). LIVE/DEAD assay revealed that seeded cells assumed a spindle-shaped morphology on the gel surface consistent with a fibroblast phenotype.

FIGURE 3.

In vitro 2D cell culture with cervical fibroblasts. A) DNA quantification, B) metabolic activity and C) LIVE/DEAD stain over 6 days of cell culture on silk biomaterials. Scale bar = 250 um; ns = not significant; * = p<0.01

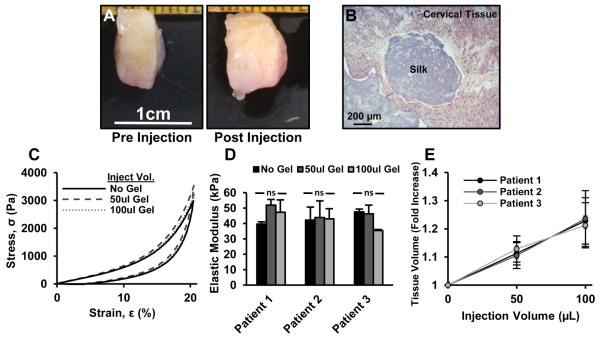

In Vitro Bulking of Human Cervical Tissue

In vitro injection of human cervical tissue showed that tissue volume could be increased without causing a significant change in cervix stiffness (FIGURE 4). Macroscopically, biopsied tissue segments (10 mm diameter, 5 mm height) increased in thickness when injected with 100 μL of silk hydrogel (Figure 4A), and histology clearly showed the injected material within the tissue matrix (Figure 4B). The stress-strain profile of the tissues did not substantially change with the addition of silk hydrogel (Figure 4C), and the augmented cervical tissue did not show significant stiffening with an increase in injected gel volume for all three tissue samples (Figure 4D). As hydrogel was injected, tissues showed an average volumetric increase of 22.6% ± 8.8% with injection of 100 μL of silk hydrogel (Figure 4E).

FIGURE 4.

In vitro bulking of human cervical tissue with injected silk hydrogels. A) Biopsied cervical tissue after hydrogel injection; B) H&E staining confirming silk within bulk tissue; C) stress-strain profiles indicating comparable tissue mechanics after gel injection; D) elastic modulus calculated from C; E) quantified volumetric bulking of tissues after gel injection. ns = not significant.

Injection Profile of Silk Biomaterials

Injection force was measured through 21G 12.7 mm length needles at a clinically relevant flow rate. The most useful materials had an injection force between 10-20 N. In SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S1, altering the silk protein concentration and molecular weight, as well as HRP and peroxide concentrations resulted in hydrogels ranging from firm gels to viscous liquids, ultimately affecting the required injection force. In general, increasing the silk protein molecular weight, silk protein concentration and HRP concentration produced stiffer gels that required greater force for injection. In SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE S2, extrusion force profiles were evaluated for hydrogel formulations. Consistent and low (10-20 N) injection force throughout delivery is desired to reduce tissue damage, avoid patient discomfort and reduce the mechanical shearing of hydrogels which can alter the material properties. Lower molecular weight silk proteins and low HRP concentrations routinely produced profiles with consistently low injection forces.

Comment

An enzymatically crosslinked silk hydrogel with promising properties for use as an alternative treatment for cervical insufficiency is reported. The selected hydrogel formulations matched the mechanical properties of native cervical tissue, required low injection force, and increased cervical tissue volume in vitro without causing tissue stiffening. In addition, the hydrogels exhibited in vitro cytocompatibility with cervical fibroblasts and biodegradation with protease solutions. These results are critical towards the continued study of an injectable biomaterial alternative to cervical cerclage.

The pathogenesis of cervical insufficiency is complex because different etiologies of preterm birth can lead to a similar phenotype – painless cervical dilation in the midtrimester.17 However, it is likely that excessive softening of the cervical tissue contributes to cervical changes leading to preterm birth.27,37,38 Although cerclage provides support to the cervix, it does not address dysfunctional tissue, which may be central to the pathogenesis of the disease. An injectable hydrogel that improves tissue function could show improved efficacy over current therapies and delay the natural history of preterm birth.

Hydrogels are an attractive class of biomaterials for tissue augmentation because the mechanical properties can be tuned to meet clinical needs. This feature is particularly important during pregnancy because biomaterials that do not match the native tissue may lead to safety concerns such as excessive tissue stiffening. We designed the hydrogels to closely match the mechanical features (softness, elasticity, etc.) of native cervical tissue during pregnancy.37 We hypothesize that hydrogels that match the mechanical features of native tissue will not impede safe dilation should induction of labor be required. Future studies will focus on testing the hydrogels in an animal model of pregnancy. The goal of animal testing will be to assess the safety of the hydrogel prior to human use.

In the present study, we focused on a silk-based hydrogel as silk protein is biocompatible and chemically versatile.39 Previous work with injectable silk hydrogels demonstrated in vitro tissue stiffening and in vivo biocompatibility in a pregnant rat model.25,26 However, the gelation mechanism used in those studies produced hydrogels that were both significantly stiffer and more brittle than native cervical tissue. In order to overcome the brittle nature of previous silk hydrogel systems, we utilized a simple method for enzyme catalyzed crosslinking of amino acid phenolic groups on the silk protein which has been employed in other biomaterial hydrogels.40,41 In previous reports, these silk hydrogels demonstrated elastomeric properties and highly tunable mechanics.29 In the present study, we demonstrate how tuning the ratios of silk protein, HRP and hydrogen peroxide concentration can produce an array of crosslinked materials from firm hydrogels to viscous fluids. Our optimized hydrogel formulations demonstrated mechanical characteristics that matched the features of pregnant and non-pregnant cervical tissues (FIGURE 1) without causing significant stiffening to cervical tissue after injection (FIGURE 4).

Useful hydrogels for cervical tissue bulking should have predictable degradation profiles on the order of several months. This duration would allow cervical support during the preterm period but full degradation by the end of pregnancy. Previous work showed that the rate of silk biomaterial degradation can be tuned by changing silk concentration, morphology and processing techniques.42 Protease XIV was selected to accelerate silk biomaterial degradation in vitro in order to elucidate differences in degradation rate due to hydrogel formulation (FIGURE 2). We expect significantly slower degradation in vivo because the concentration of protease is lower in the body. Future in vivo studies will determine how certain variables (e.g. material formulation, injection volume, etc.) affect degradation time within the cervix.

In future work, the chemical versatility of silk based biomaterials can be exploited to optimize tissue responses. Previous work with silk biomaterials demonstrated that by coupling the silk protein to integrin recognition sequences43,44 or collagen binding peptides45 tissue – biomaterial interactions can be controlled. In addition, silk biomaterials can be used in a drug delivery capacity,46,47 which may be exploited for local delivery of anti-inflammatory cytokines or progesterone. Although this report focused on silk-based biomaterials, we recognize that there are other potential biomaterial candidates (i.e. polyethylene glycol,48,49 hyaluronic acid50). However, silk-based biomaterials possess mechanical tunability, safety/biocompatibility and degradation kinetics ideal for an injectable application in the cervix. For these reasons, we elected to focus our initial studies on silk-based biomaterials.

In summary, we report on a highly elastic, cytocompatible silk based hydrogel bulking agent which can provide mechanical support to cervical tissue. This project is part of a long-term effort to design alternative, effective and safe therapies for treating cervical insufficiency. Future work will study the use of this material in pregnant animal models.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1: Injection force measurements for silk hydrogels. Hydrogel stiffness was tunable by modulating silk composition, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentrations.

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 2: Injection force profiles for selected hydrogel formulations. Hydrogels were selected for facile injection and smooth extrusion profile to reduce tissue damage and patient discomfort during injection.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NIH P41 EB002520 for support of this work.

Source and purpose of financial support: The project was supported by NIH P41 EB002520. B.P.P. was supported by the Department of Defense (DoD) through the National Defense Science & Engineering Graduate Fellowship (NDSEG) Program. The funding supported some of the personnel and research supplies for the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, Rubens CE, Stanton C. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S1. (Suppl 1) DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connor A, Wilson C, Fielder A. Ophthalmological problems associated with preterm birth. Eye. 2007;21:1254–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702838. DOI: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, Samara M. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(1):9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041367. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle LW. Outcome at 5 years of age of children 23 to 27 weeks’ gestation: refining the prognosis. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):134–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.134. DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenough A. Long term respiratory outcomes of very premature birth (<32 weeks) Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17(2):73–6. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.01.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwaniki MK, Atieno M, Lawn JE, Newton CRJC. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after intrauterine and neonatal insults: A systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):445–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howson C, Kinney M, Lawn J, editors. Born too soon. The Global Action Report on Preterm Birth. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manuck TA, Sheng X, Yoder BA, Varner MW. Correlation between initial neonatal and early childhood outcomes following preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(5):426.e1–426.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.046. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teune MJ, Van Wassenaer AG, Van Dommelen P, Mol BWJ, Opmeer BC. Perinatal risk indicators for long-term neurological morbidity among preterm neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(5):396.e1–396.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.055. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Preterm Birth 1: Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer MS, Papageorghiou A, Culhane J, et al. Challenges in defining and classifying the preterm birth syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.864. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iams J, Goldenberg R, Meis P, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iams JD, Cebrik D, Lynch C, Behrendt N, Das A. The rate of cervical change and the phenotype of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):130.e1–130.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.021. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iams JD, Berghella V. Care for Women with Prior Preterm Birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.004. DOI: 10.1002/9781444317619.ch11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parry S, Simhan H, Elovitz M, Iams J. Universal maternal cervical length screening during the second trimester: Pros and cons of a strategy to identify women at risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.021. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Practice Bulletin No.142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):372–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000443276.68274.cc. DOI: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000443276.68274.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoen CN, Tabbah S, Iams JD, Caughey AB, Berghella V. Why the United States preterm birth rate is declining. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;213(2):175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.011. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berghella V. Cerclage decreases preterm birth: finally the level I evidence is here. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):89–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.079. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macnaughton M, Chalmers I, Dubowitz V, et al. Final report of the Medical Research Council/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists multicentre randomised trial of cervical cerclage. MRC/RCOG Working Party on Cervical Cerclage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100(6):516–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15300.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daskalakis G, Papantoniou N, Mesogitis S, Antsaklis A. Management of cervical insufficiency and bulging fetal membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):221–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187896.04535.e6. DOI: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000220658.12735.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira L, Cotter A, Gómez R, et al. Expectant management compared with physical examination-indicated cerclage (EM-PEC) in selected women with a dilated cervix at 14(0/7)-25(6/7) weeks: results from the EM-PEC international cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(5):483.e1–483.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.041. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen J, Hankins G, Iams JD, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(4):375.e1–375.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.015. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landy HJ, Laughon SK, Bailit J, et al. Characteristics associated with severe perineal and cervical lacerations during vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):627–35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820afaf2. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820afaf2.Characteristics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Critchfield AS, McCabe R, Klebanov N, et al. Biocompatibility of a sonicated silk gel for cervical injection during pregnancy: in vivo and in vitro study. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(10):1266–73. doi: 10.1177/1933719114522551. DOI: 10.1177/1933719114522551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heard A, Socrate S, Burke K, Norwitz E, Kaplan D, House M. Silk-based injectable biomaterial as an alternative to cervical cerclage: an in-vitro study. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(8):929–36. doi: 10.1177/1933719112468952. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers KM, Feltovich H, Mazza E, et al. The mechanical role of the cervix in pregnancy. J Biomech. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.02.065. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vepari C, Kaplan D. Silk as a biomaterial. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32(8-9):991–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.013.Silk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partlow BP, Hanna CW, Rnjak-Kovacina J, et al. Highly Tunable Elastomeric Silk Biomaterials. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24(29):4615–24. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201400526. DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201400526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wray LS, Hu X, Gallego J, et al. Effect of processing on silk-based biomaterials: reproducibility and biocompatibility. J Biomed Mater Res, Part B. 2011;99(1):89–101. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31875. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.b.31875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers KM, Paskaleva AP, House M, Socrate S. Mechanical and biochemical properties of human cervical tissue. Acta Biomater. 2008;4(1):104–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horan RL, Antle K, Collette AL, et al. In vitro degradation of silk fibroin. Biomaterials. 2005;26(17):3385–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.020. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.House M, Sanchez C, Rice W, Socrate S, Kaplan DL. Cervical tissue engineering using silk scaffolds and human cervical cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(6):2101–12. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0457. DOI: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, Ogiso M, Minoura N. Enzymatic degradation behavior of porous silk fibroin sheets. Biomaterials. 2003;24(2):357–65. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00326-5. DOI: 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Q, Zhang B, Li M, et al. Degradation mechanism and control of silk fibroin. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(4):1080–6. doi: 10.1021/bm101422j. DOI: 10.1021/bm101422j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Numata K, Cebe P, Kaplan DL. Mechanism of enzymatic degradation of beta-sheet crystals. Biomaterials. 2010;31(10):2926–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.026. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers KM, Socrate S, Paskaleva A, House M. A study of the anisotropy and tension/compression behavior of human cervical tissue. J Biomech Eng. 2010;132(2):021003. doi: 10.1115/1.3197847. DOI: 10.1115/1.3197847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.House M, Kaplan DL, Socrate S. Relationships between mechanical properties and extracellular matrix constituents of the cervical stroma during pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33(5):300–7. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.06.002. DOI: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. New opportunities for an ancient material. Science. 2010;329(5991):528–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1188936. DOI: 10.1126/science.1188936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amini AA, Nair LS. Enzymatically cross-linked injectable gelatin gel as osteoblast delivery vehicle. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2012;27(4):342–55. DOI: 10.1177/0883911512444713. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurisawa M, Chung JE, Yang YY, Gao SJ, Uyama H. Injectable biodegradable hydrogels composed of hyaluronic acid-tyramine conjugates for drug delivery and tissue engineering. Chem Commun. 2005;(34):4312–4. doi: 10.1039/b506989k. DOI: 10.1039/b506989k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Rudym DD, Walsh A, et al. In vivo degradation of three-dimensional silk fibroin scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3415–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gil ES, Mandal BB, Park SH, Marchant JK, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Helicoidal multi-lamellar features of RGD-functionalized silk biomaterials for corneal tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31(34):8953–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.017. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu J, Rnjak-Kovacina J, Du Y, Funderburgh ML, Kaplan DL, Funderburgh JL. Corneal stromal bioequivalents secreted on patterned silk substrates. Biomaterials. 2014;35(12):3744–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.078. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.An B, DesRochers TM, Qin G, et al. The influence of specific binding of collagen-silk chimeras to silk biomaterials on hMSC behavior. Biomaterials. 2013;34(2):402–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.085. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yucel T, Lovett ML, Kaplan DL. Silk-based biomaterials for sustained drug delivery. J Control Release. 2014;190:381–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.059. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Numata K, Kaplan DL. Silk-based delivery systems of bioactive molecules. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(15):1497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin C-C, Anseth KS. PEG hydrogels for the controlled release of biomolecules in regenerative medicine. Pharm Res. 2009;26(3):631–43. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2. DOI: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:18–23. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00239-3. DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lam J, Truong NF, Segura T. Design of cell-matrix interactions in hyaluronic acid hydrogel scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(4):1571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.025. DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1: Injection force measurements for silk hydrogels. Hydrogel stiffness was tunable by modulating silk composition, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentrations.

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 2: Injection force profiles for selected hydrogel formulations. Hydrogels were selected for facile injection and smooth extrusion profile to reduce tissue damage and patient discomfort during injection.