Abstract

Chronic intake of alcohol undoubtedly overwhelms the structural and functional capacity of the liver by initiating complex pathological events characterized by steatosis, steatohepatitis, hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis. Subsequently, these initial pathological events are sustained and ushered into a more complex and progressive liver disease, increasing the risk of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. These coordinated pathological events mainly result from buildup of toxic metabolic derivatives of alcohol including but not limited to acetaldehyde (AA), malondialdehyde (MDA), CYP2E1-generated reactive oxygen species, alcohol-induced gut-derived lipopolysaccharide, AA/MDA protein and DNA adducts. The metabolic derivatives of alcohol together with other comorbidity factors, including hepatitis B and C viral infections, dysregulated iron metabolism, abuse of antibiotics, schistosomiasis, toxic drug metabolites, autoimmune disease and other non-specific factors, have been shown to underlie liver diseases. In view of the multiple etiology of liver diseases, attempts to delineate the mechanism by which each etiological factor causes liver disease has always proved cumbersome if not impossible. In the case of alcoholic liver disease (ALD), it is even more cumbersome and complicated as a result of the many toxic metabolic derivatives of alcohol with their varying liver-specific toxicities. In spite of all these hurdles, researchers and experts in hepatology have strived to expand knowledge and scientific discourse, particularly on ALD and its associated complications through the medium of scientific research, reviews and commentaries. Nonetheless, the molecular mechanisms underpinning ALD, particularly those underlying toxic effects of metabolic derivatives of alcohol on parenchymal and non-parenchymal hepatic cells leading to increased risk of alcohol-induced fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis, are still incompletely elucidated. In this review, we examined published scientific findings on how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives mount cellular attack on each hepatic cell and the underlying molecular mechanisms leading to disruption of core hepatic homeostatic functions which probably set the stage for the initiation and progression of ALD to fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. We also brought to sharp focus, the complex and integrative role of transforming growth factor beta/small mothers against decapentaplegic/plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and the mitogen activated protein kinase signaling nexus as well as their cross-signaling with toll-like receptor-mediated gut-dependent signaling pathways implicated in ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. Looking into the future, it is hoped that these deliberations may stimulate new research directions on this topic and shape not only therapeutic approaches but also models for studying ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis.

Keywords: Alcoholic hepatitis, Lipopolysaccharide, Fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis, Mitogen activated protein kinase, Transforming growth factor beta, Small mother against decapentaplegic

Core tip: Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) leading to fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis may show a bidirectional origin within the gut-liver axis. We bring to light the subtle reprogramming of the gut epithelium, gut microbiome and hepatic cells by both metabolic derivatives and unstable chemical species secondary to chronic alcohol intake, and their concerted role in ALD. We specifically highlight the integrative role of transforming growth factor-β/Smad, which synchronizes inflammatory and fibrogenic signals within the gut-liver axis. The gut may provide a less invasive option not only for prognosis and treatment of ALD but also for future research. We suggest that therapies for ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis should focus on restoring the gut microbiome.

INTRODUCTION

It is a common knowledge that continuous heavy alcohol intake (80 g/d by men and 40 g/d by women) spanning several years (10-20 years)[1-3] may ultimately lead to chronic liver injury most often characterized by steatosis, steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis leading to increased risk of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis[1,4-6]. Many reviews[6-9] and research reports[10-12], just to mention but a few, have all emphasized the pathological role of alcohol and its metabolic derivatives in ALD as well as efforts to identify some of the signaling pathways crucial in alcohol-induced liver disease. These important expert inputs have provided new insights in our understanding of ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis and have also provided new research directions about these diseases. Nevertheless, the pathological and molecular signaling pathways which underpin the initiation and progression of alcohol-induced liver injury leading to fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis still remain incompletely elucidated. For instance, signaling pathways that integrate gut-dependent alcohol-induced dysbiosis, inflammation and liver-specific alcohol-related inflammation, immune regulation and fibrogenic signals have so far remained elusive. The current difficulty in elucidating the molecular pathogenesis of alcohol-induced liver disease is multifaceted. (1) The anatomical position of the liver coupled with the diversity of agents in terms of number, biochemical properties, physicochemical properties, toxicity potential, their duration/frequency of exposure to the liver have obscured well designed attempts to delineate and characterize agent-specific effects on the liver much less the signaling pathways involved; (2) There is accumulating evidence, which seems to indicate that buildup of mutations in hepatic alcohol metabolizing enzymes (alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase, CYP2E1) and genetic alterations induced by alcohol in hepatic cells[13,14] may have further obscured attempts to elucidate the signaling pathways in ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis; and (3) Perhaps the most major difficulty is the bidirectional origin of ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis (gut to liver or liver to gut) and the dysregulation of key homeostatic functions (inflammation, immune regulation and regulation of fibrogenic signals). Notably, hepatic metabolism of alcohol as well as effect of alcohol on the gut generates many toxic chemical species with different mechanisms of hepatic toxicity which makes it difficult to distinctly identify their individual effects and signaling pathways involved.

This review takes a close look at current perspectives and scientific investigations on the effect of alcohol and its metabolic derivatives on hepatic parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells, bidirectional origin of ALD as well as the subtle conspiracy at the molecular level involving inflammatory, immune and fibrogenic signaling pathways underpinning ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. Specifically, we put into perspective the complex and integrative roles of TGF-β (a key fibrogenic cytokine), Smad proteins, and MAPK signaling pathways which pathologically suffer complicity in ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis mainly due to up-regulation of PAI-1 gene (a key downstream target gene of dysregulated TGF-β/Smad signaling in fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis) as well as recruitment of inflammatory and immune signaling pathways to promote ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. Of note, the pathological role of PAI-1 in liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and cancer in general has been reported[15]. And these pathological roles of PAI-1 may be linked to dysregulated TGF-β/Smad and MAPK pathways.

Transforming growth factor beta is a prototype of a superfamily of multi-functional cytokines including bone morphogenetic protein (BMPs), activin, inhibin, growth and differentiation factors, nodal, and anti-Mullerian hormone[16]. The TGF-β1 subtype has been extensively studied, mainly due to its physiological and pathological roles in the regulation of metazoan development, differentiation and homeostasis. It is in the light of these that the TGF-β class of cytokines is seen as a necessary evil in metazoan biology. In fact, TGF-β signaling pathway plays an important role during embryonic development, normal physiological processes and disease states by regulating several cellular processes, including cell growth and differentiation, cell migration, apoptosis, extracellular matrix formation[16] and inhibition of cell proliferation in the early stages of carcinogenesis mainly by blocking uncontrolled proliferation of epithelial, endothelial and hematopoietic cells[17]. However, genetic and epigenetic alterations of the TGF-β ligand, TGF-β-specific membrane receptors (TβRI, TβRII and TβRIII), and mediators (Smad proteins) may switch its tumor suppressor effects into tumor promotion. The susceptibility of TGF-β to loss of function mutations in various cancers has been reported[18]. For example, loss or gain of function mutations in TβRI[19] TβRII[20-22], Smad2[23,24], Smad3[25] and Smad4[23,26] have all been implicated in various human cancers. Therefore, it is not surprising that dysregulated TGF-β signaling pathway suffer complicity in almost all known human cancers[27-30]. It is maintained that genetic and epigenetic factors conspire to mastermind switching of TGF-β function by rendering tumor cells resistant or unresponsive to TGF-β-mediated growth arrest, and other homeostatic functions. TGF-β has been branded as the key factor regulating the acquisition of all the phenotypic hallmarks of cancer (cell proliferation, induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), induction of tissue invasion and migration, induction of tumor angiogenesis, inhibition of immune surveillance, induction of cancer cell survival, cancer cell immortality and resistance to TGF-β-mediated cytostasis)[27,30]. Recent evidence shows that mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway regulate linker-dependent phosphorylation of receptor mediated Smads (Smad2 and Smad3) to promote pathological roles of dysregulated TGF-β/Smad signaling in liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[31,32]. The question arises as to how these signaling pathways act in synchrony to modulate alcohol-dependent activation of the hepatic cells to promote ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis from the perspective of the gut and the liver. Does chronic alcohol exposure alter TGF-β/Smad and MAPK signaling pathways? If it does, how and which component of the TGF-β/Smad signaling mediators is/are altered and how? Finally, how do deliberations on these questions inform us of future research directions and therapeutic strategies against ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis? The above questions are the preoccupation of the present review.

HEPATIC ALCOHOL METABOLISM

The liver metabolizes alcohol by employing two mechanisms, either through cytosol degradation by alcohol dehydrogenase to acetaldehyde (AA), then to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase in the mitochondria or via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzyme system where CYP2E1 actively metabolizes alcohol in cases of heavy alcohol ingestion[33-35]. Efficient functioning of these two hepatic alcohol metabolic processes ensure that toxic metabolites of alcohol, mainly AA (a hepatotoxin as well as a neurotoxin), MDA (a hepatotoxin) and some other unstable derivatives of the metabolites including CYP2E1-generated free radicals, protein adducts of AA and MDA, are rendered inactive or cleared from the system long before they cause any cellular damage. Indeed, buildup of AA and MDA, an inevitable phenomenon in chronic alcohol intake, is implicated for most of the toxic effects associated with chronic alcohol use[34].

Interestingly, it was reported that CYP2E1 activity may be induced about two to tenfold after chronic alcohol exposure and the underlying mechanism was linked to oxidative stress[36]. It was also reported that CYP2E1-dependent alcohol metabolism causes oxidative stress through increased output of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[37-39], which has already been implicated in lipid peroxidation and liver injury[40].

It must be noted that both cytosolic and mitochondrial alcohol metabolic pathways reduce NAD+ to NADH (addition of a hydrogen atom to NAD+ to convert it to NADH), however, impairment of any of the two metabolic pathways as a result of chronic alcohol intake may lead to a high NADH/NAD+ ratio which by extension affects cytosolic and mitochondrial metabolism of carbohydrate and lipid substrates leading to impaired gluconeogenesis[4]. It was reported that alcohol exposure induces fatty liver disease by increasing NADH/NAD+ ratio[41]. It remains to be established whether alcohol-induced NADH/NAD+ turnover underlies reprogramming and switching energy metabolism of pre-neoplastic hepatic cells from efficient mitochondria oxidative phosphorylation to that of inefficient but protective aerobic glycolysis (so-called Warburg effect). The net effect is that there is diminished substrate flow through the Kreb’s cycle, giving rise to diversion of acetyl CoA to fatty acid synthesis and this possibly underlies NADH-induced inhibition of mitochondria fatty acid β-oxidation and elevated fatty acid synthesis leading to the onset of alcoholic liver disease[42-44].

Currently, it has been proposed that the pathogenesis of a healthy liver to one of alcohol-induced liver damage may involve a two-hit progression with steatosis being considered as the “first hit”, followed by cellular insults such as oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, direct lipid toxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction and/or infection to cause hepatic inflammation leading to alcoholic steatohepatitis[4-6]. As useful as this current “two hit” proposal may be, it remains to be clarified whether the pathological sequence of ALD leading to fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis lend itself to any particular set pattern, in view of the fact that diverse toxic agents of non-alcoholic origin may also influence ALD progression. The effect of co-morbidity factors such as hepatitis B and C infections has been shown to increase the progression of ALD. However, it is still difficult to clarify the question of which toxic agent first initiates liver damage and which toxic agent takes over at what cellular time scale and how? Is it alcohol or the co-morbidity factors that first initiate liver damage? It appears that alcohol-induced liver damage leading to ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis may not follow any specific temporal sequence, in view of the presence of other non-alcohol toxic agents. It is possible that the underlying non-alcohol liver-specific toxic agents may be the determinants of the temporal sequence of alcohol-induced liver disease.

Alcohol-induced liver damage displays bidirectional origin in view of the significant nauseating role of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from progressive alteration of the gut microenvironment by chronic alcohol intake.

ALCOHOL AND ALTERATION OF GUT MICROBIOME

The invention of the microscope[45] provided the impetus to uncover the co-existence of micro-organisms and humans[46]. It is now a common knowledge that the human gut, (a prominent barrier organ) harbors a metagenomic community of some 1014 micro-organisms[47] mainly dominated by bacteria. The gut microbiome does play many regulatory functions spanning regular modulation of the innate and adaptive immune systems[48], synthesis and release of nutrients, vitamins, and preservation of the structural and functional integrity of the gut wall[46]. For instance, in the course of evolution of the gut microbiome, the diverse gut microorganisms have progressively managed to adapt as commensals, producing nutrients, such as vitamins of the B and K subclasses[49], and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). About 60%-90% of SCFAs in the gut lumen are absorbed by enterocytes to regulate energy supply, control gut pH, and resist pathogenic growth[50] probably via inflammasome[51]. The gut microbiome also plays a role in bile acid regulation[52,53], exchange of phenolic and aromatic acids[54], cholines, fatty acids and phospholipids[55,56]. Liver-specific biosynthesis of primary bile acids are reported to be dehydroxylated by some of these gut microbiome giving rise to secondary bile acids, which may be absorbed by the enterocytes to promote lipid absorption and energy homeostasis[52,53]. In view of the above, the importance of the gut microbiome in anti-oxidant, inflammatory, immune and energy homeostasis cannot be underestimated and therefore it represents a crucial determinant of the body’s susceptibility to irritants including alcohol and its metabolic derivatives.

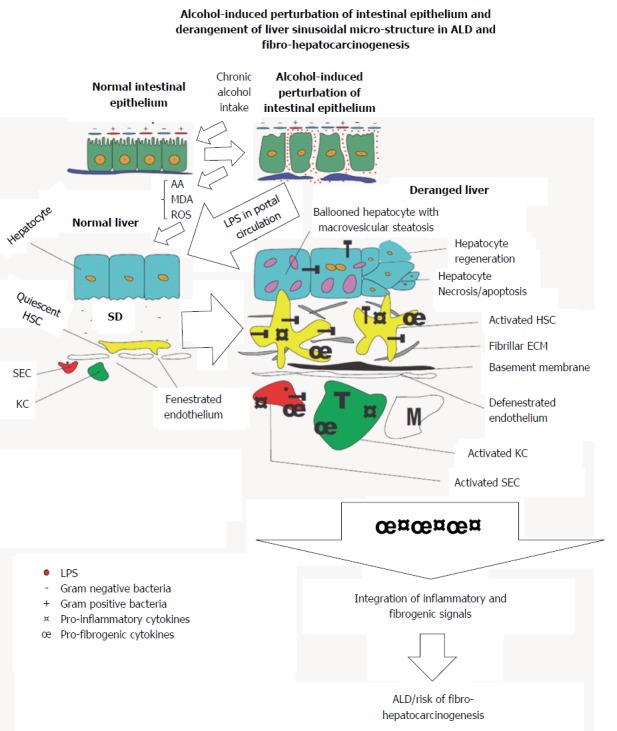

It is not surprising that alterations in the number and species diversity of the gut microbiome culminating from host-behaviors including but not limited to chronic alcohol intake derail the essential benefits of the gut microbiome[57] and may provide avenue for the onset of various inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal system and its accessory organs, of which the liver is the most affected. From hindsight, change in gut microbial diversity has long been implicated in Crohn’s disease (CD)[46], ulcerative colitis (UC)[46] and irritable bowel disease (IBD)[46,58]. The case is not different with chronic alcohol exposure and the possible increase in Gram negative/Gram positive bacteria ratio (Figure 1). Nakayama et al[59] have shown that increased translocation of Streptococcus suis and its degraded products across the gut wall secondary to alcohol exposure correlated with progression of ALD. Accumulating evidence show that chronic alcohol intake may switch the afore-mentioned essential regulatory functions of the gut microbiome into a rather deleterious one. For example, alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis increases endotoxin turnover[60,61], particularly LPS[6,62], which leads to increased leakage of endotoxins into portal circulation and chronic stimulation of the liver. By diverse mechanisms, alcohol and its metabolic derivatives have been implicated in dysbiosis of the gut mucosal layer[63-66].

Figure 1.

An illustration of the bidirectional origin of alcoholic liver disease and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis within the gut-liver axis. Chronic alcohol use induces derangement of the gut epithelium, increases Gram-/Gram+ bacteria ratio, increases endotoxin turnover, increases permeability of gut epithelium to endotoxins including lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Subsequently leakage of LPS into portal circulation gain access to liver to initiate activation of hepatic cells. LPS-dependent activation of hepatic cells is further augmented by metabolic derivatives of alcohol to promote alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. T: Toll-like receptor 4; HSC: Hepatic stellate cell; KC: Kupffer cell; SD: Space of disse; SEC: Sinusoidal endothelial cell; M: Monocyte.

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are breakdown products of bacterial cell walls, specifically pathogenic Gram negative bacteria strains[67] and it is reported that it can activate hepatic cells[6,67] and initiate overt inflammatory responses via TNF-α mediation[68,69]. Under normal physiological conditions, release of LPS from breakdown of pathogenic Gram negative bacteria into portal circulation is rendered harmless by endothelial cells lining blood vessels, sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) of the liver as well as liver-resident macrophages (KCs) or its cellular concentration is reduced to levels well below physiological concentrations insufficient to elicit any inflammatory response. But perturbations of the gut wall as a result of chronic alcohol intake (Figure 1), increases gut permeability to LPS derived from degraded bacterial cells[62] and this certainly leads to leakage of high concentrations of LPS into portal circulation. The high levels of LPS in portal circulation overwhelms the regulatory capacity of SECs and endothelial cells leading to chronic liver injury[41]. Continual exposure of the liver to gut-derived LPS serves as an inflammatory nosae, first by disrupting the balance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory homeostatic regulation. This balance is shifted to favor heightened or sustained inflammatory response. To sustain the exaggerated inflammatory response, LPS first activates hepatic parenchymal cells, precisely SECs KCs and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) leading to re-programming of their core functions. It is not surprising that a correlation was reported between increased intestinal LPS permeability and alcoholic hepatitis[60,61]. Similarly, LPS derived from alcohol-induced increase in gut permeability was shown in alcoholics to correlate with the pattern and the amount of alcohol consumed[70,71] while high levels of LPS were detected in the sera and livers of patients with alcohol-induced liver disease[62]. The hepatotoxic effect of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), e.g., LPS[72] has been shown to be mediated through toll-like receptors (TLRs)[73]. LPS is specifically reported to be the ligand for TLR4 subtype[67]. Importantly, TLR4 as well as other TLR subtypes have been shown to be expressed on KCs, HSCs and hepatocytes under inflammatory conditions[9,74]. TLRs are crucial in the regulation of innate immune responses, sensing of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) as well as PAMPs, of which LPS is an integral component. Also, it was reported that LPS/TLR4 signaling involves LPS-binding protein (LBP), CD14 and MD-2[75,76]. LBP facilitates the transfer of LPS from the outer membrane of bacterial cells to CD14, which in turn ensures the formation of TLR4-MD-2[77] to trigger LPS/TLR4 signaling, but downstream of this TLR4-mediated LPS-induced liver inflammation is myeloid differentiation factor protein 88 (MyD88). LPS-induced release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12), chemokines (INF-γ, MCP-1)[78] as well as cell adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1) via activation of NF-κB and IκB in injured hepatic cells was MyD88-dependent[78]. LPS-induced activation of the MAPK pathway leading to the expression of activator protein (AP)-1 was also reported to be MyD88-dependent[79-81].

In short, chronic alcohol intake may generate an inflammatory arsenal comprising LPS, ROS, AA and MDA together with their respective protein adducts, which launches continuous attack on hepatic cells (Figure 1). The pathological manifestation of these acohol-mediated attacks on the liver may depend in part on the synergistic interaction between alcohol and non-alcohol co-morbidity factors. Consequently, this sets the stage for the onset of liver fibrosis and its progression to cirrhosis, thus increasing the risk of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. To appreciate how the alcohol generated inflammatory arsenal attack the hepatic cells, we take a cursory look at each of the hepatic cells in the light of their normal structure and function vs their alteration by alcohol and its metabolic derivatives.

ALCOHOL, METABOLIC DERIVATIVES OF ALCOHOL AND ACTIVATION OF HEPATIC CELLS

Sinusoidal endothelial cells

Sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs) are hepatic non-parenchymal cells characterized by flattened and highly fenestrated features[6]. SECs have no basement membrane and their microstructure endows them with the ability to selectively filter blood components from portal circulation into the space of Disse, for subsequent presentation to the hepatocytes and lipid storage cells[6].

Additionally, SECs are endowed with scavenger receptors (SRs) and higher permeability properties, and these factors make it possible for SECs to engage in phagocytosis, clearing blood of harmful toxins and ensuring bidirectional exchange of substances between the hepatic parenchyma cells and portal blood. The SECs, by logic provides the first line of defense for the liver, essentially scavenging and clearing potential harmful products from attacking the liver. Many immunological functions, including but not limited to the following, removal of small molecules (< 200 nm) from the blood using innate immune mechanisms such as scavenger and mannose receptors[82,83], expressions of MHC class II and co-stimulatory molecules (CD54 and CD106), and antigen processing, presentation, and leukocyte recruitment[83], have been attributed to SECs.

The afore-mentioned homeostatic functions of SECs in the liver of an alcoholic become derailed due to continuous and sustained activation of SECs by gut-derived LPS leakage into portal circulation. For example, exposure of SECs to LPS was shown to have induced basement membrane formation[84], and this observation was said to have preceded fibrogenesis. Some results from in vitro studies have also shown that SECs can reverse activated HSCs back to their quiescent state, but SECs loose this property following capillarization due to LPS activation[85]. Serious is the fact that continuous LPS-activation of SECs induces decreased responsiveness of SECs to LPS and also diminishes SEC-dependent scavenger functions. Eventually, the liver may be exposed to potentially damaging insults including metabolic derivatives of alcohol.

Accordingly, AA and MDA were shown to have formed protein adducts, which in turn stimulated SECs to produce more fibrogenic cytokines[6]. A clear attestation to this observation was demonstrated by fibronectin. Fibronectin was shown to be overexpressed following alcohol-induced liver damage and it was implicated in the activation of HSCs leading to liver fibrosis[6]. MDA-derived protein adducts were reported to have increased the expression of soluble fibronectin, cellular fibronectin and EIIIA fibronectin variant (the variant form of fibronectin, most implicated in HSC activation)[86,87]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 were similarly shown to have increased following treatment of isolated SECs with MDA-derived protein adducts[87,88]. Also, AA/MDA modified proteins were reported to have induced SECs to release both pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic signals[88], while LPS was similarly reported to induce AA/MDA modified protein adduct-dependent release of chemokines and cytokines by SECs[89]. Evidently, LPS, AA, MDA, and their protein adducts act in concert to potently induce apoptosis of SECs which leads to weakening of SEC-dependent defense mechanisms of the liver, further, compounding an already compromised liver. LPS-activated SECs may in turn trans-activate KCs and HSCs in addition to their direct stimulation by LPS.

Kupffer cells

As part of the reticuloendothelial system are cells called Kupffer cells (KCs). Kupffer cells are monocyte-derived cells resident in the liver as specialized hepatic macrophages[6,90]. These cells were first observed by Karl Wilherm von Kupffer in 1876[91] to whom is credited the name KCs, but it was not until 1898 that KCs were correctly identified as macrophages[92]. Their origin can be traced to the bone marrow, where pro-monocytes and monoblasts cells differentiate into monocytes, which then enter circulation and finally transform into KCs[93].

Functionally, KCs form a major part of the reticuloendothelial system within the liver sinusoidal compartment, phagocytizing senescence red blood cells as well as phagogenic presentations. As a result, they are widely scattered within the sinusoids. In support of the phagocytizing capacity of KCs, Helmy et al[94] have reported a receptor of the immunoglobulin family (CRIg), and they further showed that CRIg null mice could not clear complement system-coated pathogens, and that CRIg is well conserved in mice and humans, emphasizing the relevance of the CRIg as a component of the innate immune system and that of the role of KCs in the innate and complement systems.

In normal physiological state, KCs perform their immuno-regulatory functions without overt release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines; however, alcohol and its associated metabolic derivatives have the potential to reprogram KCs through repeated or continuous activation. This undue activation of KCs renders them more pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic due to KC-dependent release of inflammatory and fibrogenic cytokines. For instance, it was reported that under stress conditions, KCs and other hepatic cells release cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-) and chemokines (MIP-2, IP-109, KC/GRO, MIP-1α, and RANTES)[90,95]. It is the unregulated release of these inflammatory and fibrogenic cytokines that induces liver injury. It was further shown that each of the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines could directly cause liver injury by targeting hepatic cells or indirectly through chemo-attraction of immune cells including neutrophils and lymphocytes[95]. Also, it was reported that the expression of adhesion molecules changes during LPS/alcohol-dependent liver injuries. Notably the enhanced expression of PECAM-1 and down-regulation of ICAM-1 characteristic of normal liver were reported to be reversed by TGF-β under inflammatory conditions[96].

Chronic exposure of the liver to alcohol succeeds in changing the sensitivity of KCs to LPS stimulation[97-99]. In a study to clarify alcohol-induced sensitization of KCs to LPS, Watanabe et al[100] have suggested that it could be due to the effect of alcohol on calcium channels, which is indispensable for TNF-α release. Exposure of KCs to alcohol does not only increase sensitivity of KCs to metabolites of alcohol but also increases intracellular calcium channels in KCs. It was shown that KCs exposed to alcohol for two hours lacked elevated intracellular calcium, but prolongation of alcohol exposure time to 24 h showed increased intracellular calcium, which manifested as TNF-α production and expression of LPS binding receptor (CD14), and this perhaps explains the increased sensitivity of KCs to LPS. Chronic alcohol exposure was also shown to have increased the expression of α2A-adrenoceptors in activated KCs and it was linked to the release of TNF-α and TNF-α-induced liver injury[101]. LPS was shown to augment AA/MDA protein adduct-mediated release of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic cytokines and chemokines by KCs[89]. LPS-induced acute and chronic liver injury was linked to activation of KC[102,103].

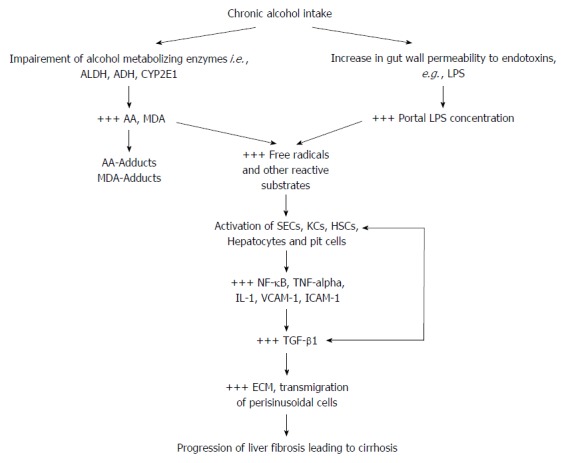

The activation of KCs is not limited to only LPS-derived from gut microbiome, and proteins modified by AA and MDA may also activate KCs leading to overt inflammatory and immunological responses injurious to the liver (Figure 2). Many alcohol modified protein adducts have been widely implicated in alcoholic liver disease[89,104,105]. Alcohol and its metabolic derivatives have also been implicated in KC/prostaglandin E2-induced liver injury[106] and this is in part attributed to endotoxin-dependent release of nitric oxide (NO) in KCs[107]. It appears that, chronic alcohol exposure in addition to AA and MDA dependent liver injury may also induce increase in gut-derived LPS, increase in LPS leakage into portal blood, increase in blood concentration of LPS, increase in LPS binding receptor expression and increased sensitivity of KCs to LPS and these may collectively sustain liver injury.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustration of the two-way attack of hepatic cells in alcoholic liver disease and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. By multiple mechanisms alcohol metabolizing enzymes and gut-derived LPS induce production of free radicals which stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic cytokines. Free radical-dependent activation of hepatic cells leads to the release of pro-inflammatory transcription factor (NF-κB) and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) which provide the signal for injurious overt hepatic inflammatory response. Secondary to the injurious hepatic inflammatory response, is the activation of hepatic cells (mainly HSCs and KCs) to further release pro-fibrogenic factors, mainly the key fibrogenic cytokine (TGF-β) which mediates a high ECM turnover (increased fibrogenesis : fibrinolysis ratio) in HSCs and the space of Disse, and trans-migration of hepatic non-parenchymal cells. These pathological events initiate liver fibrosis and cirrhosis leading to fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. AA: Acetaldehyde; ADH: Aldehyde dehydrogenase; ALDH: Alcohol dehydrogenase; ECM: Extracellular matrix; HSCs: Hepatic stellate cells; IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta; KCs: Kupffer cells; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MDA: Malondialdehyde; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa B; SECs: Sinusoidal endothelial cells; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; VCAM: Vascular cell adhesion molecule; +++: Up-regulated expression or overproduction.

LPS activation of hepatic cells shows a snowballing effect, in that apart from LPS directly activating each hepatic cell, each activated hepatic cell may in turn influence the activation of its neighboring hepatic cells in a manner akin to paracrine or hormone-like cell to cell communication. For example, LPS-induced activation of SECs leads to activation of KCs via release of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic factors, similar activation of KCs also in turn activate quiescent HSCs through the release of TNF-α and TGF-β1[6]. Typically, LPS-activated KCs were shown to have activated HSCs in vitro leading to HSC proliferation and increased ECM production[108]. Next, we look at how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives act in concert to activate HSCs to usher in liver fibrosis.

Hepatic stellate cells

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are non-parenchymal hepatic cells located within the space of Disse between endothelial cells and hepatocytes[109,110]. HSCs can exist in two distinct forms depending on whether they are activated by an external inflammatory nosae or otherwise. In their normal inactivated state, also known as quiescent stellate (Ito) cells, they function normally by storing vitamin A, and may play modulatory roles during inflammation by expressing ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. It has been shown that HSC activation (tran-differentiation of quiescent vitamin A-storing cells to proliferative myofibroblast cells) by hepatotoxins plays a crucial role in liver fibrogenesis. To substantiate this claim, it was shown that inactivation of HSCs attenuates liver fibrosis[111]. Activated HSCs, mostly release excess TGF-β1 which has been shown to down-regulate ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 while increasing N-CAM expression in HSCs. In addition, HSCs in their activated states may express TNF-α, which reduces N-CAM-coding mRNAs and also induces ICAM-I-and-VCAM-1 specific transcripts by many folds[90]. Under inflammatory conditions, HSCs trans-differentiate into myofibroblast and concomitantly increase ECM production. There is dysregulation of ECM metabolism which promotes liver fibrosis. This underlies the initiation of fibrogenesis and the complicity of HSCs in liver fibrosis[112]. Coherent with this, Knittel et al[113] have intimated the importance of HSCs during hepatic injury through the recruitment and migration of mononuclear cells in the peri-sinusoidal space. This perhaps sets the stage for the secretion of TGF-β and TNF-α and their pathological role in liver fibrosis[114,115] and several other cytokines and chemokines including MCP-1, RANTE-1, and IL-8[116-118].

The effect of alcohol and its metabolic derivatives on HSC activation and their roles in ALD progression have been extensively investigated. For example, alcohol-induced activation of HSCs was linked to the release of TGF-β1, matrix proteins, and initiation of fibrogenic response[112,119]. Karaa et al[120] have also shown that alcohol exposure to mice produced HSC activation in addition to increased hepatic collagen output and neutrophil infiltration.

Evidence implicating alcohol-specific metabolites in liver injury was clearly demonstrated by using 4-methylpyrazole (4-MP), an inhibitor of alcohol metabolism. It was shown that sustained alcohol exposure to precision cut liver slices (PCLS) produced increased levels of IL-6, depletion of GSH stores, increased lipid peroxidation, increased expression of smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and increased deposition of collagen in liver sinusoidal space[6]. But all these aforementioned alcohol exposure-specific phenotypic hallmarks were reversed by 4-MP treatment[6,121], emphasizing the involvement of alcohol and its metabolic derivatives in liver fibrosis.

Furthermore, LPS was reported to exert direct effect on HSCs[122] and also indirectly via LPS activated KCs[108,123]. LPS was shown to enhance the effect of alcohol and AA on HSC activation[124,125] and the expression of collagen 1 and IL-6[126], while AA alone induced activation and proliferation of HSCs[127,128] and expression of α-SMA[127,129].

At the mechanistic level, AA-induced activation of HSCs was linked partly to ERK1/2/PI3K pathway[130,131], JNK/α1-collagen pathway[132] and TGF-β1/TβRII signaling[133,134]. Transcriptional elevation of TGF-β and its membrane receptors (TβRI and TβRII) have been considered as key hallmarks of activated HSC[135]. And this certainly increases the sensitivity of activated HSCs to TGF-β-mediated fibrogenic signals. Siegmund et al[9] have posited that the signal for ECM production by HSCs in liver-related diseases of all etiologies including alcohol emanates from TGF-β. Corroboratively, it was shown that TGF-β protein levels increased in both experimental and human liver fibrosis[136]. Thus, TGF-β is the key contributor of irregular ECM accumulation in liver sinusoidal space by forming basal membranes leading to defenestration of the liver sinusoids[137] as well as decreasing MMPs to further halt ECM degradation[138].

Hepatocytes

Hepatocytes are the main hepatic cells in the liver accounting for 80% of the cytoplasmic mass of the liver[90]. Characteristically, hepatocytes exhibit eosinophilic cytoplasm (a cytoplasm with abundant mitochondria) and basophilic stippling (abundance of endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes)[90]. Within the liver, hepatocytes are organized into cell-thick plates separated by vascular channels[139,140]. When these structural and functional characteristics of hepatocytes are not disturbed or altered by any nosae, hepatocytes can attain an average life span of 5 months whiles retaining the capacity to regenerate[90].

Functionally, hepatocytes are involved in protein synthesis, protein storage, and transformation of carbohydrates, synthesis of cholesterol, bile salts, phospholipids, detoxification, modification and excretion of exogenous and endogenous substances[90]. Additionally, hepatocytes can biosynthesize hormones including insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1)[90,141], thrombopoietin[142], erythropoietin[143] and cytokines such as IL-8[144,145] needed for normal hepatic homeostatic processes.

In the event of liver injury due to alcohol and its metabolic derivatives, the degree of injury overwhelms the hepatocyte defense mechanisms, especially when the nosae is continuous and sustained (Figure 1). As a means of defense, hepatocytes may respond to acute phase inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 by releasing acute phase proteins including C-reactive protein (CRP)[146], serum amyloid A (SAA)[147] and also some intracellular defense proteins like heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1)[148]. In a desperate attempt to fight back, hepatocytes employ various mechanisms including release of chemokines such as MIG[149], IP-10[149], cytokine-induced neutrophil chemo-attractant (KC), MIP-1, MIP-2, and MIP-3 which act in concert to recruit and activate pro-inflammatory cells (mononuclear phagocytes) and KCs respectively. But because the inbuilt intracellular hepatocyte defense mechanisms i.e., CRP, SAA and HO-1, and the anti-oxidant system have already been weakened, by the continuous exposure of the damaging nosae, the hepatocyte defense response leads to mass hepatocyte apoptosis at a rate that further compromise the structural and functional integrity of the liver as a whole. Hepatocyte cytosol and microsomal compartments are the initial sites for alcohol metabolism before mitochondrial-dependent breakdown. The number and integrity of hepatocytes are rate-limiting factors in alcohol metabolism. Therefore, increased apoptosis of hepatocytes leads to poor alcohol metabolism which further increases the buildup of alcohol metabolites (AA and MDA), meanwhile KCs, SECs, and NKs which could clear the debris and the resulting buildup of toxins have been disabled by LPS, AA, and MDA. This situation exposes the liver to potentially damaging nosae which may set the stage for the initiation of cirrhosis leading to HCC.

Pit cells

Pit cells, lymphocyte-derived non-parenchymal cells, form about 1% of the non-parenchymal cell mass[150]. Pit cells are liver representatives of natural killer cells (NKs) in other organs. Pit cells are suspected to have originated from the bone marrow transported by blood to finally settle in the liver, where they transmogrify into their current state by lowering their density and increasing their granular content. The very existence of the pit cells are dependent on KCs[151], which suggest that whatever that happens to KCs will in turn affect the fate of pit cells.

Functionally, pit cells biosynthesize interferon gamma (IFN-γ) in response to damaging inflammatory nosae, but they can also partake in the destruction of virus-infected malignant cells. Pit cells are versatile migratory cells and they are normally activated by interleukin-2[90]. Alcohol, AA, MDA, and LPS may directly damage pit cells through continuous activation or indirectly by activated KCs and HSCs, leading to functional impairment and consequences thereof on the liver, in view of the fact that pit cells via the perforin/granzyme-dependent mechanism are indispensable in the removal and apoptosis of splenic/blood-NK-resistant tumor cells[152]. Importantly, TGF-β-induced repression of NKs, a phenomenon characteristic of chronic alcohol consumption[153], has been linked to failure of NK cell-mediated apoptosis of HSCs[154,155].

Evidently, chronic alcohol intake affects the structural and functional capacity of all the hepatic cells and this possibly may set the cellular stage for the actions of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic cytokines acting in concert to promote ALD leading to fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. At the center of this complex cellular conspiracy against the liver are the TGF-β/Smad and MAPK pathways and their downstream target genes.

TGF-β: A VERSATILE SIGNALING MODULATOR WITH COMPLEX FUNCTIONALITY IN ALD AND FIBRO-HEPATOCARCINOGENESIS

To appreciate how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives alter TGF-β/Smad signaling to promote ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis, we should first take a panoramic view of TGF-β/Smad signaling and also the cell/context-specific functions of TGF-β which perhaps may explain its complex and integrative roles in ALD. TGF-β is considered to exert growth restraints on various cancer cells at the initial stages of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis by mechanisms including cell cycle arrest at critical check points, induction of apoptosis and restoration of cellular structure[156-158], an observation which highlights TGF-β as a potent anti-tumor cytokine[31]. However, by a sudden twist of events, in a different cellular context such as in ALD, fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis as well as in other disease pathologies, it tends to promote disruption of cell adhesion, induces migration and invasion, and mediate immune suppression and angiogenesis, to become a crucial tumor promoter[158]. For example, in ALD it was reported that AA does not only increase the steady levels of TGF-β mRNA transcripts[159] but also promote activation of latent TGF-β and elevate the expression of TβRII[134]. Furtheremore, it was shown that a decrease in TGF-β protein levels correlated with a decrease in AA-induced α2 collagen (I) gene[160].

Basically, TGF-β signaling involves two major signaling modes, canonical and non-canonical. The former is mediated by Smad proteins while the latter involves cross signaling between TGF-β and other cell signaling pathways implicated in cancer such as Wnt/β-catenin pathway[161,162], VEGF pathway[163,164], aberrant FGF/FGFR signaling pathways[165,166], MAPK pathway[167,168], PI3k/AKT/ mTOR pathway[169], HGF signaling[164], aberrant EGF/EGFR signaling pathway[170], and deregulation of IGF pathway[171]. To proceed, we highlight the Smad proteins and the MAPK pathway, which have so far been shown to work closely with TGF-β signaling in both cell and animal models of ALD (Table 1) to promote liver fibrosis and HCC[31].

Table 1.

Involvement of Transforming growth factor-β, Smad, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways in alcoholic liver disease and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis

| Alcohol/ metabolic derivative | Mechanism/pathway | Cellular context | Ref. |

| Alcohol, LPS, SAMe | Inhibition of TGF-β/Smad signaling abrogates alcohol-induced liver injury | Cultured HSCs, male rats | [120,221] |

| alcohol and LPS induce liver fibrosis via activation of TGF-β signaling in a Smad3-dependent fashion and down-regulation of Smad7, but SAMe could abrogate it and also restore Smad7 expression | |||

| AA | Up-regulation of Smad3 and Smad4, increase in nuclear translocation of Smad3/4 complex, decrease in Smad7 expression, all leading to enhanced expression of COL1A2 | Human and mouse HSCs | [159,219,222,223] |

| Increase in TGF-β1 secretion and up-regulated expression of TβRII in HSCs was linked to AA | |||

| AA increased COLα1 expression in HSCs in a Smad3-dependent manner | |||

| Alcohol | Alcohol-induced increase in endotoxemia linked to up-regulated protein expression of TGF-β1, IL-6, NF-κB, TNF-α, IκBα | Guinea pig liver | [224] |

| Alcohol, LPS | Alcohol potentiates LPS-induced pancreatic fibrosis via increased production of TGF-β1 | Human pancreatic tissue sample, pancreatic acinar-like cells (AR42J) | [225] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol-induced translocation of S. suis across gut wall and also up-regulated TGF-β1 and COL 1 to promote liver disease | Alcoholics, mice, Caco-2 cells | [59] |

| Alcohol | While alcohol exposure impairs nuclear import of growth hormone-induced STAT5B and IL-6-induced STAT3, it had no effect on TGF-β1-induced nuclear import of Smad2/3 | Rat liver, adult male C57BL/6J mice | [11,184,226,227] |

| TGF-β1 mediates liver fibrosis in experimental rats in a Smad4-dependent fashion | |||

| Alcohol-induces hepatic iron overload leading to liver damage via modulation of hepcidin through BMP6/Smad4 signaling pathway | |||

| Alcohol | Alcohol modulates iron-induced liver injury via increased expression of TGF-β1, BMP2, phosphorylated Smad2 | Mice | [228] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol-induced steatosis and liver injury in Smad7 null mice is enhanced by TGF-β1 signaling and TGF-β1-induced EMT in hepatocytes | Alb-Cre mice, Smad7 (loxP/loxP) mice | [229] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol exposure induces TGF-β1 release and activation of TGF-β1-induced down-regulation of alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1) mRNA transcripts in part through TGF-β/ALK5/Smad2/3 signaling | Mice | [230] |

| Alcohol, AA | Alcohol and AA-induced activation of TGF-β1, JNK and p38 signaling pathways were inhibited by butein | HSCs, HepG2 cells | [231] |

| Alcohol | TGF-β1 mediates alcohol-induced activation of HSCs via activation of p38/JNK MAPK pathway and overexpression of HSC markers including α-SMA, procollagen1, betulin and betulinic acid can reverse these pathways to restore liver integrity | Rat HSCs | [232] |

| Alcohol, LPS | LPS and CYP2E1-dependent oxidative stress synergistically activate p38/JNK pathway via LPS/TNF-α signaling pathway | Hepatic cells | [233] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol induces cytotoxicity via activation of p38, JNK and ERK MARK pathway, but COS reversed this by inhibiting the MAPK pathway and activation of Nrf2 | Human L02 normal liver cells | [234] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol induces hepatotoxicity by activating p38/JNK MAPK pathway in addition to NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α, but these effects were reversed by MA | Mice | [235] |

| Alcohol | Activation of JNK and ERK MAPK pathway mediates alcohol-induced oxidative stress, but HO-1-derived CO reversed these effects by activating p38 MAPK pathway just as CORM-2, which suppressed TNF-α and IL-6 | Adult male Balb/c mice, primary rat hepatocytes | [236] |

| Alcohol | TLR2/4, p38/ERK MAPK pathway, IL-1β, TNF-α, COX-2 mediate alcohol-induced liver injury, but noni juice (NJ) effectively reverses alcohol-induced liver injury by modulating the above factors | Mice | [237] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol-induced hepatocyte apoptosis is mediated through activation of p38/JNK MAPK pathway and also involve Fas | Human liver adenocarcinoma (SK-Hep1) cells | [238] |

| LPS | LPS induces liver inflammation via multiple pathways including activation of p38 MAPK/Nrf2/HO-1, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, TNF-α | RAW264.7 cells, CLP-induced septic mice | [239] |

| Alcohol | ERK MAPK activation, increase in mRNA transcripts of egr-1 and PAI-1 are associated with alcohol-induced steatosis and hepatic necrosis | Rats | [240] |

| LPS | Activation of p38 MAPK pathway and COX-2 mediate LPS-induced liver injury, however, ES attenuates liver injury by modulating the above pathways | Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats | [241] |

| Alcohol | Activation of p38, JNK and ERK MAPK pathways and histone modification (acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation) mediates alcohol-induced hepatic cellular injury | Male SD rats | [242] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol enhances Fas-induced liver injury by activating p38/JNK MAPK pathway, increase caspase-3 and -8 and TNF-α | Mice | [243] |

| LPS | Alcohol induces CYP2E1 and LPS overproduction, and CYP2E1 sensitizes hepatocytes to LPS/TNF-α-dependent injury and this is mediated through activation of p38/JNK MAPK pathway | [244] | |

| Alcohol | Inhibition of liver regeneration in partial hepatectomized rats is associated with alcohol-induced p38 activation and cyclin D1 expression | Male Wistar rats | [245] |

| Alcohol | Alcohol-induced inhibition of HO-1 is mediated through blockade of p38/ERK MAPK-dependent nuclear import of Nrf2, but quercetin can reverse this blockade to restore hepatoprotection against alcohol-induced oxidative stress | Human hepatocytes | [246] |

| Alcohol | Increased gastric mRNA transcripts was reported as a response to alcohol-dependent nosae on the gut wall, suggesting the protective role of PAI-1 in the gut | C57BL/6 mice, PAI-1-1-H/Kβ mice | [247] |

| Alcohol, LPS | Increase in PAI-1 correlated with progression of ALD | In vitro and in vivo models of ALD, mice | [199-201] |

| PAI-1 was implicated in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a two-hit model of ALD involving alcohol and LPS | |||

| Alcohol-induced increased in hepatic lipids was linked to up-regulation of PAI-1, but this was reversed by metformin |

ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; HGF; Hepatocyte growth factor; ECM: Extracellular matrix; PAI: Plasminogen activator inhibitor; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; MAPK: Mitogen activated protein kinase; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; Smad: Small mother against decapentaplegic; SAMe: S-adenosyl-L-methionine.

Smad proteins

Genetic studies spanning more than a decade ago using Caenorhabditis elegans (a nematode), and Drosophila melanogaster (a fruitfly) led to the discovery of a group of genes, which were later named Smads from their original sources. Smads are the central mediators that carry signals from receptors of TGF-β, BMP, and activin cytokines to the nucleus[172]. Smads which are now identified as substrate transcriptional factors play integral functions in the intracellular signaling responses to TGF-β and its related signaling complex[173]. Basically, the Smad proteins have three forms, namely receptor mediated Smads (Smad 2 and Smad3 specific for TGF-β), inhibitory Smad (Smad7) and a common Smad (Smad4). It must be stated that mutations in these Smad types due to genetic and epigenetic causes such as alcohol exposure are linked to dysregulated TGF-β signaling in ALD and cancer in general. For example, Smad7 inhibits TGF-β/TβRI-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3[174-176] to abrogate dysregulated TGF-β/Smad signaling transduction in many disease pathologies including but not limited to ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. But, alcohol and LPS were shown to down-regulate Smad7 expression to induce liver fibrosis in a Smad3-dependent fashion[120]. Similarly, a number of reports from cell and animal studies (Table 1) have implicated receptor-mediated Smad proteins (Smad2 and Smad3) in ALD as well as in HCC patients. Smad4 deletions have been mapped in HCC[18]. Smad2[23,24], Smad3[25] and Smad4[177] mutations have been detected in various cancer subtypes. But it remains to be elucidated how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives modulate the Smad proteins and the signaling pathways they mediate, particularly the upstream (TGF-β ligand, TβRI, TβRII, Smad2, Smad3, Smad4, Smad7) and downstream (Imp7/8, PAI-1) signaling mediators of TGF-β and how such findings may inform future research directions and precisive therapeutic strategies against ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. It is worth suggesting that Smad2, Smad3, and Smad7 deletions or/and mutations should be mapped in ALD as well as in HCC to facilitate early screening, diagnosis and treatment of ALD and its related complications.

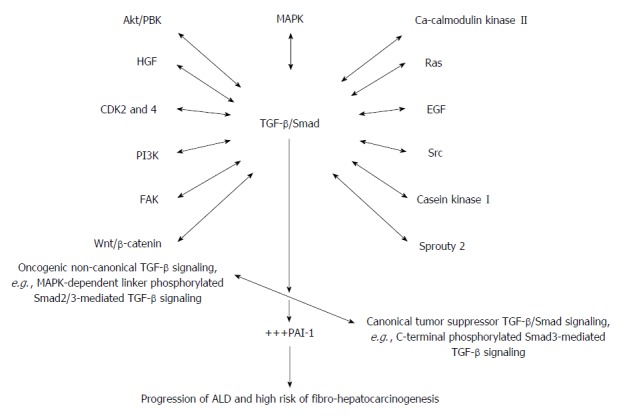

Importantly, it must be mentioned that the switch of TGF-β function from tumor suppression in early stages of cancer as well as in early stages of ALD to tumor promotion in late HCC reflects an imbalance between canonical and non-canonical TGF-β signaling and recruitment of other oncogenic signaling pathways (Figure 3). What actually causes this switch has so far remained elusive. Refreshingly, in HCC it was reported that binding of Gas6 ligand to Axl induces activation of Axl/14-3-3ζ to switch TGF-β signaling from tumor suppression to tumor promotion in a JNK/Smad3L-dependent fashion[178]. It was also mentioned that suppression of Axl succeeded in blocking oncogenic TGF-β signaling in HCC, and this has raised hopes about indirect inhibition of oncogenic TGF-β signaling using Axl-specific inhibitors. A number of Axl-specific inhibitors are under various stages of preclinical studies including SGI-7079, BGB324, DP3975 and NA80xl[179].

Figure 3.

A proposed schematic illustration of the complex and integrative role of TGF-β/Smad signaling in alcoholic liver disease and alcohol-induced fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. Alcohol and its metabolic derivatives induce the release and activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling through NF-κB/TNF-α mediation (Figure 1). The NF-κB/TNF-α-mediated activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling switches canonical tumor suppressor (C-terminal phosphorylated Smad3/Smad4-dependent TGF-β signaling) into oncogenic (MAPK-dependent linker phosphorylated Smad2/3-dependent TGF-β signaling) and also non-canonical TGF-β signaling involving cross-signaling with other signaling pathways implicated in hepatic malignancies. Key cross-signaling pathways which team up with TGF-β signaling includes but not limited to CDK 2 and 4, Ca-calmodulin kinase II, EGF, HGF, PI3K/AKT, FAK, Src, Sprouty2, casein kinase I, Wnt/β-catenin. This leads to imbalance between canonical and non-canonical TGF-β signaling. Increase in oncogenic TGF-β/Smad signaling leads to up-regulation of PAI-1 gene expression and PAI-1-mediated pathologies thereof. The key pathological effects of PAI-1 include dysregulated ECM regulation, cell proliferation and invasion, and dysregulated apoptosis and these underlie initiation and progression of alcohol-induced fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. HGF: Hepatocyte growth factor; ECM: Extracellular matrix; PAI: Plasminogen activator inhibitor; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; MAPK: Mitogen activated protein kinase; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; Smad: Small mother against decapentaplegic; +++: Up-regulated expression or overproduction.

Canonical TGF-β signaling

The canonical TGF-β signaling is mediated primarily by Smad proteins (Smad2, Smad3, Smad4) via TGF-β-specific receptors (TβRI, TβRII and TβRIII). Trans-membrane TGF-β signaling begins with ligand binding of TβRIII, which then presents TGF-β to TβRII[180], this is peculiar to TGF-β2 which only interacts with TβRIII before it becomes bound to TβRII. However, the other TGF-β family members, precisely TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 readily bind to TβRII without the need of binding to TβRIII; therefore they can transduce intracellular signals either in the presence or absence of TβRIII[17]. TGF-β activated TβRII subsequently trans-phosphorylate TβRI. Activated TβR-I in turn trans-phosphorylate latent transcriptional factors (Smad2 and Smad3) at their C-terminal SXS motif[17]. The phosphorylated Smad2/3 undergoes a rapid conformational change which facilitates their oligomerization with a common Smad4. The formation of Smad2/3/4 complex enhances preferential nuclear relocation and accumulation of the complex[181-183]. The cellular responses to TGF-β are fine-tuned by continuous nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Smad2/3, which permits continuous sensing and responds to changes in TGF-β receptor activity[184,185]. The nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Smad2/3/4 complex is crucial for TGF-β signaling and this is aided by karyopherins, particularly Imp7/8. In the nucleus, the Smad2/3/4 complex interacts with transcriptional co-activators or repressors to determine the transcription of TGF-β target genes, such as PAI-1 gene, therefore deciding the fate of cells[186].

Though alcohol and its metabolic derivatives in many studies (Table 1) have been shown to stimulate increased expression of PAI-1, it remains to be explored how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives modulate Imp7/8 which facilitates Smad2/3/4 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. It must be noted that TGF-β/Smad signaling mediated through C-terminal phosphorylation of Smad2/3 corresponds to all its tumor suppressor and cytostatic functions. The exact modulation of canonical TGF-β/Smad, particularly Smad2/3/4 and their regulation by alcohol and its metabolic derivatives need to be clarified, in the light of gut-dependent and liver-dependent alcohol-induced inflammatory and fibrogenic signals. It is currently held that ALD may begin from the gut[187-190]. A paradigm that does not only highlight the therapeutic potential of the gut[191] but also the prognostic and diagnostic value of the gut. The possible crosstalk between LPS/TLR4/TNF-α/TNF-αRI/MLCK in gut dysbiosis/inflammation and alcohol-induced liver inflammation/fibrogenesis driven by dysregulated TGF-β/Smad and the MAPK pathways remain veiled. Unveiling the link between the gut-liver axis in the light of TGF-β/Smad/MAPK and TLR4/TNF-αRI signaling will undoubtedly not only help to explain the switch of TGF-β signaling from tumor suppression to tumor promotion in ALD, but will also open a new therapeutic avenue to advance target specific therapies against ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis.

Non-canonical TGF-β signaling

Aside the canonical TGF-β signaling via TGF-β-specific membrane receptors (TβRII and TβRI) and latent Smad proteins (Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4), TGF-β also activates other signaling pathways quiet independently. Among the signaling pathways activated by TGF-β are the MAPK pathway[192-194], the growth and survival kinases (P13K, AKT/PKB, mTOR) and the small GTP-binding proteins (Ras, RhoA, Racl, and Cdc42)[195-197]. It is worth notice that oncogenic non-canonical TGF-β signaling in its full activation as is the case in ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis far outweigh the canonical tumor suppressor TGF-β/Smad signaling and could therefore explain the connivance between alcohol and its metabolic derivatives and the oncogenic non-canonical TGF-β signaling in ALD, increasing the risk of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. This is evident in the elevated expression of PAI-1 in some cell and animal models of ALD and HCC. Importantly, PAI-1 is a key target gene of TGF-β signaling and plays crucial roles in all disease pathologies in which TGF-β is implicated.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor

Plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 gene is an important inhibitor of both tissue and urokinase type plasminogen activators; as a result it inhibits fibrin degradation via inactivation of plasminogen[6] and also mediates some inflammatory responses[198]. Many reports have implicated PAI-I in alcohol-induced liver damage[199-201]. PAI-I levels were shown to increase following acute and chronic alcohol exposure[200], and a decrease in PAI-1 expression perhaps through RNA interference significantly reduced alcohol-induced steatosis and lipid peroxidation[200].

Fibrinolysis has been shown to be a common feature in alcohol-induced liver disease; meanwhile PAI-1 gene is a crucial modulator of fibrinolysis through its inhibitory action on plasminogen activator[201]. The involvement of PAI-1 in alcohol-induced liver damage could be traced to the link between TNF-α and TGF-β/Smad signaling and could also explain the integrative role of TGF-β in the gut-liver axis in alcohol-induced fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis, since PAI-1 is a major target gene of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway[31,32,202]. The complicity of TNF-α in alcohol-induced fatty liver disease, where it was purported to increase the expression of PAI-1,[6] emphasizes a more complex interaction between pro-inflammatory and fibrogenic factors in ALD. TNF-α mediates the pro-inflammatory signaling while TGF-β1 controls the fibrogenic signals. To confirm the TNF-α/PAI-1 link, alcohol-induced expression of PAI-1 in TNFR1 -/- mice was investigated and found inhibited[200], indicating that TNF-α might induce PAI-1 through the MAPK pathway[203]. But the crosstalk between the MAPK pathway and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway is a common dysregulated signaling pathway implicated in many cancers, particularly MAPK-dependent linker phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 leading to increased PAI-1 expression and occurrence of phenotypic hallmarks of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis[32].

MAPK pathway

Recent developments in the understanding of TGF-β/Smad signaling has revealed non-Smad TGF-β signaling[204] and a growing indication of a crosstalk between MAPK pathway and Smad signaling downstream of TGF-β[205]. The MAPKs represent a large class of serine/threonine protein kinases crucial in the initial responses to a diversity of extracellular signals involved in cell growth, cell differentiation and apoptosis[206] and activation of nuclear transcription factors by allowing nuclear sensing of extracellular signals[207]. They are grouped into three sub-classes: the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1, ERK2), the stress-activated protein (SAP) kinases, also known as c-jun N-terminal kinases (JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3), and the p38 MAPKs (α, β, γ, and δ)[193]. In several reports, TGF-β was shown to activate ERK, p38, and JNK in different cell types[208,209]. As a result, TGF-β signaling can be regulated via linker-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2/3. A number of protein kinases including ERK1/2[193], JNK[210] and p38[211] activated by TGF-β in turn phosphorylate Smad2/3 at the linker region. It is a common knowledge that linker-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2/3 in part switches the TGF-β/Smad signaling from tumor suppression to tumor promotion.

Notably, alcohol and its metabolic derivatives have been shown to activate the MAPK pathway, and this was reported to be crucial for collagen formation in HSCs[212]. Alcohol-dependent activation of the MAPK pathway depended on the type of hepatic cell and their physiological state, duration of alcohol exposure, and the type of agonist[212]. With specific reference to KCs, TNF-α production and release was linked to chronic alcohol exposure and LPS-induced activation of p38 MAPK[212]. Similarly, LPS-induced activation of ERK and p38 MAPKs was shown to be responsible for liver injury[213]. While elucidating how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives activate the MAPK pathway, Yao et al[214] showed that CD14-mediated LPS recognition of TLR4/MD-2 complex mediates TNF-α release secondary to MAPK activation. To stoke more arguments and perhaps stimulate search for explanation, it was reported that activation of p38 MAPK is indispensable for hepatocyte proliferation, while sustained activation of the MAPKs reverses this effect[215,216]. The TGF-β/Smad and the MAPK signaling pathways may be crucial in the initiation and progression of ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. It is apparent that a signaling loop possibly involves LPS/TLR4/MD-2/TNF-α-MAPK and TGF-β/Smad crosstalk at multiple levels and plays key roles in ALD as well as recruitment of other signaling pathways implicated in ALD (Figure 3). Some of the signaling pathways recruited into the TGF-β/Smad/MAPK signaling nexus may include but not limited to Spry2[217], EGF and FGF[218], Ras and Wnt/β-catenin[219]. For instance, TGF-β1 was shown to down-regulate Spry2 in a Smad-dependent fashion[217], meanwhile, Spry2 aids phosphorylation of PTEN and its nuclear accumulation to induce p53-mediated growth arrest[220] which perhaps underlies Spry2-dependent inhibition of HCC cell growth and inhibition of c-Met-induced proliferation and angiogenesis in fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis[218]. But PTEN, which negatively regulates PI3K/AKT signaling, is in turn down-regulated by TGF-β1[31]. However, it is yet to be determined how alcohol and its metabolic derivatives modulate the tumor suppressor PTEN via the TGF-β/Smad/MAPK pathways. Will selective inhibition of TGF-β specific receptors, MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of Smad2/3, TNF-α/TNF-αRI in ALD enhance PTEN expression to halt ALD and the risk of fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis?

CONCLUSION

The structural and functional integrity of the liver is anchored on three pillars: effective modulation of inflammation, oxidative/nitrosative stress, and the innate and adaptive immune systems. From the foregoing, it appears that alcohol and its metabolic derivatives disrupt these three cardinal hepatic functions through reprogramming the functions of hepatic cells to favor ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis progression through concerted interplay of LPS/TLR4/MD-2/TNF-α-MAPK and TGF-β/Smad signaling. Consequently, alcohol primes the liver to diverse irritants and also increases the sensitivity of hepatic cells to inflammatory nosae derived from non-alcohol sources such as those from co-morbidity factors. This may underlie the spectrum of the pathological features of ALD and other liver disorders, in view of the fact that alcoholics and non-alcoholics alike have in one way or the other been exposed to alcohol and its metabolic derivatives once in their life time either through de novo biosynthesis of alcohol from food or from some endogenous substrates under conditions of low oxygen tension such as hypoxia.

Etiologically, metabolic derivatives of alcohol as well as alcohol-dependent alteration of gut microbiome, derangements of gut wall, increased production of PAMPs such as LPS and their subsequent leakage into portal circulation, certainly are the significant alcohol-induced disrupters of inflammatory, innate and adaptive immune regulation within the gut-liver axis. Alcohol-induced liver inflammation, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis leading to increased risk of HCC may not follow a specific temporal sequence but could follow a multi-dimensional pattern determined in part by the existence of non-alcohol co-morbidity factors.

Mechanistically, alcohol and its metabolic derivatives provide a pathological platform for concerted interaction between pro-inflammatory factors (NF-κB, TNF-α, and IL-1β), pro-fibrogenic factors (TGF-β, Smad, MAPK and PAI-1) and recruitment of other signaling pathways such as the PI3K, Sprouty2 in a TGF-β/Smad-dependent fashion to promote ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis. TGF-β/Smad/MAPK and their associated cross-signaling nexus must be seen as indispensable in ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis.

At the research front, it is important that future studies on ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis focus on experimental models that will permit study of each of the distinct alcohol-derived inflammatory nosae, i.e., AA, MDA, ROS, LPS, AA/MDA-derived protein/DNA adducts and also delineation of nosae-specific pathways, while at the same time excluding overlap from co-morbidity factors. This will certainly further expand our understanding and discourse on ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis to guarantee informed prognosis, diagnosis and treatment.

Therapeutically, TGF-β receptor inhibitors, Smad3L-specific inhibitors, MAPK-specific inhibitors, TNF-α/TNF-αRI-specific inhibitors as well as gut-specific therapeutic strategies must feature prominently in therapies designed for ALD and fibro-hepatocarcinogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mr. James Asenso (Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Drug Research, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China) for typing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81374012 and No. 81573652.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 6, 2015

First decision: September 29, 2015

Article in press: November 19, 2015

P- Reviewer: Chetty R S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Liu JD, Leung KW, Wang CK, Liao LY, Wang CS, Chen PH, Chen CC, Yeh EK. Alcohol-related problems in Taiwan with particular emphasis on alcoholic liver diseases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:164S–169S. doi: 10.1111/acer.1998.22.s3_part1.164s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandayam S, Jamal MM, Morgan TR. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:217–232. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, Bennett MK, James OF. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet. 1995;346:987–990. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gyamfi MA, Wan YJ. Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: the role of nuclear receptors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:547–560. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart S, Jones D, Day CP. Alcoholic liver disease: new insights into mechanisms and preventative strategies. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:408–413. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffert CS, Duryee MJ, Hunter CD, Hamilton BC, DeVeney AL, Huerter MM, Klassen LW, Thiele GM. Alcohol metabolites and lipopolysaccharide: roles in the development and/or progression of alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1209–1218. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceni E, Mello T, Galli A. Pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: role of oxidative metabolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17756–17772. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepard BD, Fernandez DJ, Tuma PL. Alcohol consumption impairs hepatic protein trafficking: mechanisms and consequences. Genes Nutr. 2010;5:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s12263-009-0156-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegmund SV, Dooley S, Brenner DA. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Dig Dis. 2005;23:264–274. doi: 10.1159/000090174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin M, Ande A, Kumar A, Kumar S. Regulation of cytochrome P450 2e1 expression by ethanol: role of oxidative stress-mediated pkc/jnk/sp1 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e554. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez DJ, Tuma DJ, Tuma PL. Hepatic microtubule acetylation and stability induced by chronic alcohol exposure impair nuclear translocation of STAT3 and STAT5B, but not Smad2/3. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1402–G1415. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00071.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritz KS, Green MF, Petersen DR, Hirschey MD. Ethanol metabolism modifies hepatic protein acylation in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res. 2007;37 Suppl 2:S88–S94. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van De Craen B, Declerck PJ, Gils A. The Biochemistry, Physiology and Pathological roles of PAI-1 and the requirements for PAI-1 inhibition in vivo. Thromb Res. 2012;130:576–585. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-beta family proteins in development and disease. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/ncb434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian M, Neil JR, Schiemann WP. Transforming growth factor-β and the hallmarks of cancer. Cell Signal. 2011;23:951–962. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy L, Hill CS. Alterations in components of the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathways in human cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:41–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goggins M, Shekher M, Turnacioglu K, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE. Genetic alterations of the transforming growth factor beta receptor genes in pancreatic and biliary adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5329–5332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markowitz S, Wang J, Myeroff L, Parsons R, Sun L, Lutterbaugh J, Fan RS, Zborowska E, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Inactivation of the type II TGF-beta receptor in colon cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Science. 1995;268:1336–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.7761852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons R, Myeroff LL, Liu B, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Microsatellite instability and mutations of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5548–5550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myeroff LL, Parsons R, Kim SJ, Hedrick L, Cho KR, Orth K, Mathis M, Kinzler KW, Lutterbaugh J, Park K. A transforming growth factor beta receptor type II gene mutation common in colon and gastric but rare in endometrial cancers with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5545–5547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maliekal TT, Antony ML, Nair A, Paulmurugan R, Karunagaran D. Loss of expression, and mutations of Smad 2 and Smad 4 in human cervical cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:4889–4897. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prunier C, Ferrand N, Frottier B, Pessah M, Atfi A. Mechanism for mutational inactivation of the tumor suppressor Smad2. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3302–3313. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3302-3313.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han SU, Kim HT, Seong DH, Kim YS, Park YS, Bang YJ, Yang HK, Kim SJ. Loss of the Smad3 expression increases susceptibility to tumorigenicity in human gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:1333–1341. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burger B, Uhlhaas S, Mangold E, Propping P, Friedl W, Jenne D, Dockter G, Back W. Novel de novo mutation of MADH4/SMAD4 in a patient with juvenile polyposis. Am J Med Genet. 2002;110:289–291. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasche B. Role of transforming growth factor beta in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:153–168. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200002)186:2<153::AID-JCP1016>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakowlew SB. Transforming growth factor-beta in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:435–457. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boye A, Yang Y. Hepatic microRNA orchestra: a new diagnostic, prognostic and theranostic tool for hepatocarcinogenesis. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2014;14:837–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boye A, Kan H, Wu C, Jiang Y, Yang X, He S, Yang Y. MAPK inhibitors differently modulate TGF-β/Smad signaling in HepG2 cells. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:3643–3651. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-3002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zakhari S, Li TK. Determinants of alcohol use and abuse: Impact of quantity and frequency patterns on liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:2032–2039. doi: 10.1002/hep.22010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemelä O, Parkkila S, Ylä-Herttuala S, Villanueva J, Ruebner B, Halsted CH. Sequential acetaldehyde production, lipid peroxidation, and fibrogenesis in micropig model of alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 1995;22:1208–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sladek NE, Manthey CL, Maki PA, Zhang Z, Landkamer GJ. Xenobiotic oxidation catalyzed by aldehyde dehydrogenases. Drug Metab Rev. 1989;20:697–720. doi: 10.3109/03602538909103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouillon Z, Lucas D, Li J, Hagbjork AL, French BA, Fu P, Fang C, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Donohue TM, French SW. Inhibition of ethanol-induced liver disease in the intragastric feeding rat model by chlormethiazole. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;224:302–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieber CS. CYP2E1: from ASH to NASH. Hepatol Res. 2004;28:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieber CS. The discovery of the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system and its physiologic and pathologic role. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36:511–529. doi: 10.1081/dmr-200033441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parola M, Robino G. Oxidative stress-related molecules and liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2001;35:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]