Abstract

Recently, chloroquine (CQ) has been widely used to improve the efficacy of different chemotherapy drugs to treat tumors. However, the effects of single treatment of CQ on liver cancer have not been investigated. In the present study, we examined the effects of CQ on the growth and viability of liver cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, and revealed that CQ treatment triggered G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, induced DNA damage and apoptosis in a dose- and time-dependent manner in liver cancer cells. Moreover, administration of CQ to tumor-bearing mice suppressed the tumor growth in an orthotopic xenograft model of liver cancer. These findings extend our understanding and suggest that CQ could be repositioned as a treatment option for liver cancer as a single treatment or in combination.

Keywords: chloroquine, cell cycle, DNA damage, apoptosis, liver cancer

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with an estimated 782,500 new liver cancer cases and 745,500 related deaths occurring worldwide in 2012 (1). Chemotherapy is a reasonable treatment option for patients with advanced HCC. However, traditional chemotherapy has shown modest efficacy with severe side-effects. Therefore, it is necessary to identify new agents or therapeutic strategies to improve the treatment of liver cancer. One of the important methods is to understand the detailed effect of traditional drugs for drug repositioning (2).

Chloroquine (CQ) is a classic drug for the treatment of malarial (3). Recently, CQ has been widely used as an enhancing agent in cancer therapies and has a synergistic effect with ionizing radiation or chemotherapeutic agents in a cancer-specific manner (4–9). In addition, CQ was reported to inhibit cell growth and/or induce cell death in several tumor models (10–13), and showed lower toxicity to non-tumorigenic epithelial cells (14). However, the effects of single treatment of CQ on liver cancer have not been investigated.

In the present study, we examined the effects of CQ on the growth and viability of liver cancer cells in vitro and in vivo, and revealed that in vitro treatment of liver cancer cells with CQ inhibited cell proliferation and viability, induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, DNA damage and apoptosis with upregulation of pro-apoptotic protein Bim. Moreover, administration of CQ to tumor-bearing mice inhibited the tumor growth in an orthotopic xenograft model of liver cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, culture and reagents

Human liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Huh7 were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (HyClone), and were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biochrom AG) at 37°C with 5% CO2. CQ was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Cell proliferation and clonogenic assays

HepG2 and Huh7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2.5×103 cells/well) and were treated with different concentrations of CQ as indicated for 24, 48 or 72 h. Cell proliferation was determined using the ATPLite Luminescence assay kit (Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo) was used to quantify drug-induced cytotoxicity as follows. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates, exposed to different concentrations of CQ for 72 h and were then treated with CCK-8 reagent for assessment of cytotoxicity.

For the clonogenic assay, cells were seeded into 6-well plates with 500 cells/well in triplicate, treated with the indicated concentrations of CQ for 24 h, and then washed with PBS twice, followed by incubation for 9 days. The colonies formed were fixed, stained and counted. Colonies with >50 cells were counted.

Western blotting

HepG2 and Huh7 cell lysates treated with CQ were prepared for western blot analysis, using antibodies against cleaved caspase-3, cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), the Pro-Apoptosis Bcl-2 Family Antibody Sampler Kit, the Pro-Survival Bcl-2 Family Antibody Sampler kit, IAP Family Antibody Sampler kit and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells treated with CQ at the indicated concentrations were harvested, fixed in 70% ethanol at −20°C, and were then stained with propidium iodide (PI; 50 µg/ml) containing RNase A (30 µg/ml) (both from Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were then analyzed for cell cycle profile by flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton-Dickinson). Data were analyzed with ModFit LT software (verity).

Apoptosis assay

HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ for 72 h. Apoptosis was determined with the Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis kit (Biovision, Inc. Milpitas, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The early apoptotic (Annexin V-FITC-positive) and necrotic/late apoptotic (Annexin V-FITC-positive, PI-positive) cells were quantified as apoptotic cells. Caspase-3 activity was assessed by the CaspGLOW Fluorescein Active Caspase-3 Staining kit (Biovision, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Evaluation of mitochondrial membrane depolarization

HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ at the indicated concentrations. Mitochondrial membrane depolarization was detected with the mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1 according to the manufacturer's protocol (Yeasen Inc., Shanghai, China). The data were acquired and analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (15).

Immunofluorescence

HepG2 and Huh7 cells were plated on chamber slides and treated with CQ for 36 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100, and incubated overnight with the γ-H2AX antibody (Cell Signaling). Goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 fluorescent secondary antibody was used to visualize γ-H2AX foci, and DAPI was used to visualize the nuclei.

Antitumor effect of CQ in vivo

An orthotopic xenograft model of liver cancer was established by AntiCancer Biotech as previously described (15). Briefly, HepG2-GFP human liver cancer tissues that originated from subcutaneous tumors of nude mice were harvested and carefully inspected to remove necrotic tissue. The harvested tumor tissues were then equally divided into small pieces of 1 mm3 each. One 1-mm piece of the above tumor tissue fragments was inserted into the incision of the liver of each mouse. The tumor-bearing mice were randomized into 2 groups (7 mice/group) and treated with PBS or CQ (80 mg/kg, s.c.), twice a day respectively, on a 3-day-on/2-day-off schedule for 25 days. Tumor growth was observed, and the tumor area was recorded twice a week with a Fluorvivo Model-300 imaging system as previously described (16,17). Briefly, whole-body images of each mouse were obtained with a Fluorvivo Model-300 imaging system (INDEC BioSystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in live animals. High resolution images were directly captured on a personal computer (Axis 945GM) and were analyzed using Power Analysis Station (INDEC BioSystems). At the time of sacrifice, tumor tissues of the mice were collected, photographed and weighed.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. The unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for the comparison of parameters between groups. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

CQ inhibits the proliferation of liver cancer cells

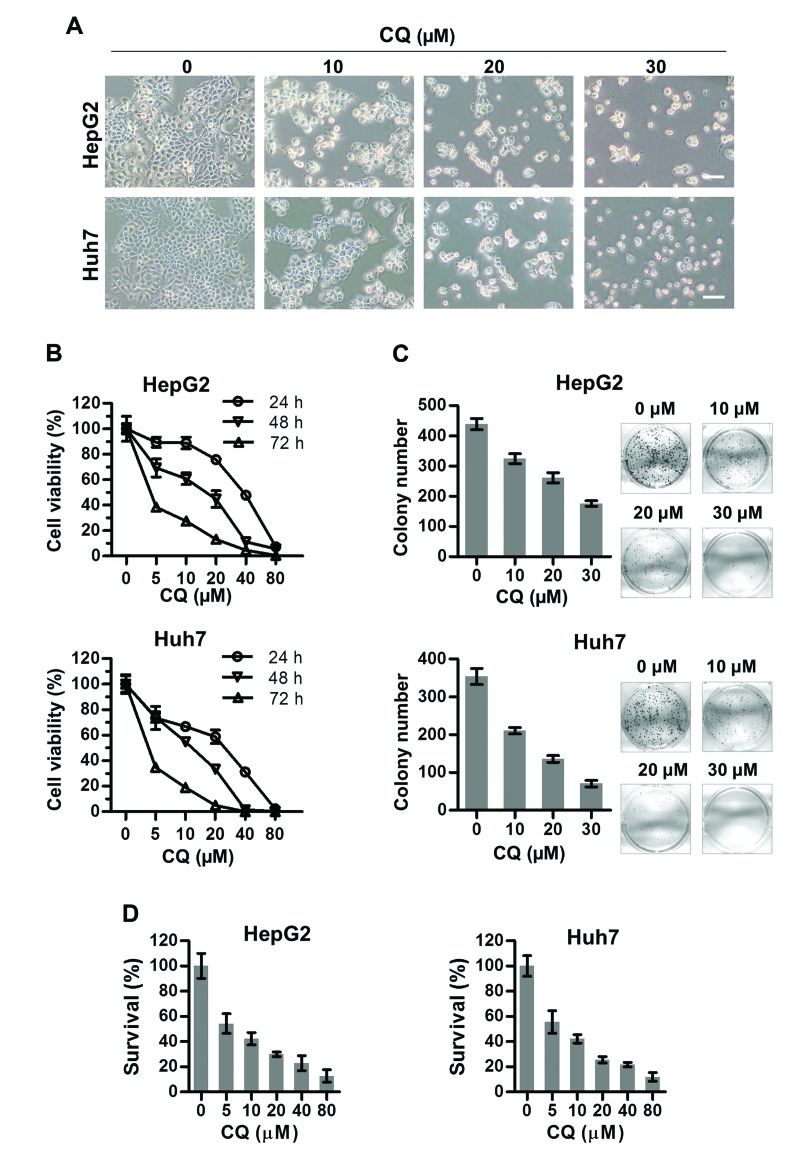

To assess the anticancer activity of CQ on liver cancer, we first investigated the effect of CQ on the proliferation of two liver cancer cell lines HepG2 and Huh7. Morphologically, we found that both HepG2 and Huh7 cells shrunk and floated with increasing concentrations of CQ (Fig. 1A). As a result, the viability of both cell lines decreased with CQ treatment in a time- and dose-dependent manner using ATPLite assay (Fig. 1B). At the same time, CQ induced a dose-dependent inhibition of cell colony formation (Fig. 1C) of liver cancer cells. Cytotoxicity of CQ was assessed in both cell lines (Fig. 1D) using the CCK-8 assay, which was in accordance with the results of the ATPLite assay (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Chloroquine (CQ) significantly suppresses the proliferation of liver cancer cells. (A) observation of cellular morphology upon CQ treatment. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ at the indicated concentrations for 72 h, followed by morphological observation. Scale bar, 1 µm. (B) CQ suppressed the proliferation of liver cancer cells. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates and treated with CQ at the indicated concentrations. Cell viability was measured at the time points indicated using the ATPLite assay. (C) Treatment with CQ suppressed colony formation in liver cancer cells. Statistical results are shown in the left panels and representative images are shown in the right panels. (D) HepG2 and Huh7 cells were exposed to different concentrations of CQ for 72 h. Cytotoxicity was measured by CCK-8 assay as described in Materials and methods.

CQ induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in liver cancer cells

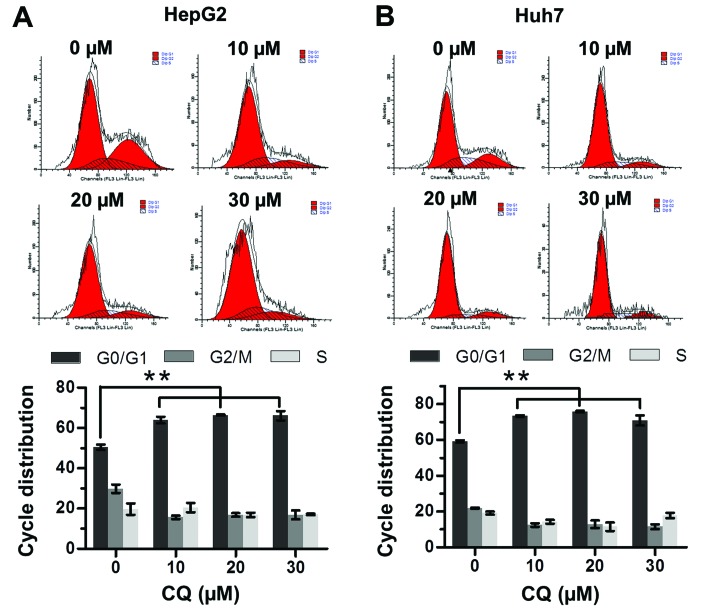

The effect of CQ on cell cycle progression was examined to elucidate the mechanism of its antiproliferative activity. Flow cytometric analysis showed that CQ triggered G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in both the HepG2 and Huh7 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Chloroquine (CQ) triggers G0/G1 cell cycle arrest. (A) HepG2 and (B) Huh7 cells were treated with CQ at different concentrations for 24 h, followed by PI staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis for the cell cycle profile. Representative images are shown in the upper panels and statistical results are shown in the lower panels.

CQ induces apoptosis in liver cancer cells

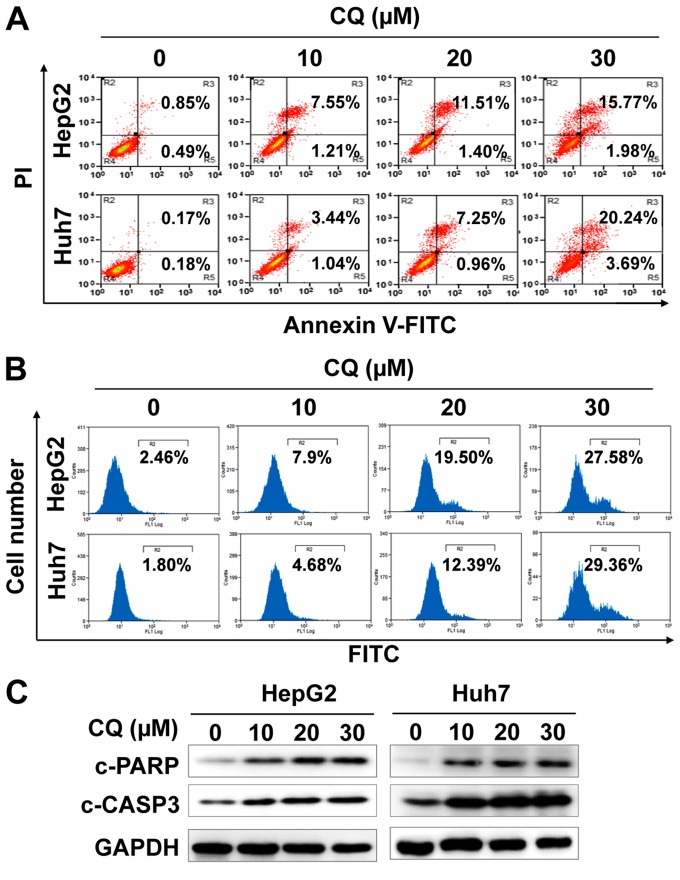

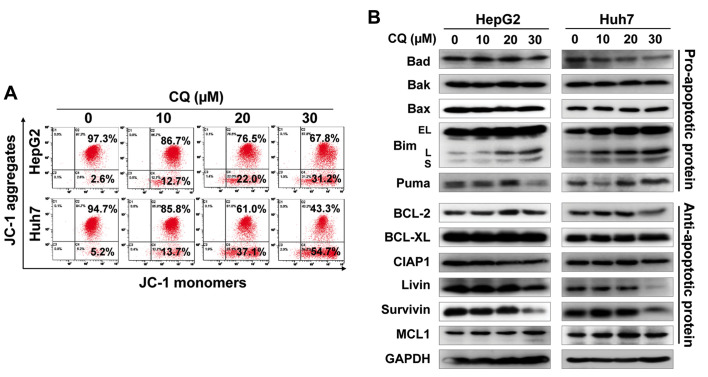

We next examined whether apoptosis was also responsible for the anticancer activity of CQ. The results showed that CQ treatment led to the accumulation of cells in early- (Annexin v+/PI−) and late-stage (Annexin v+/PI+) apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). At the same time, CQ treatment also led to the increased activity of caspase-3 (Fig. 3B), and proteolytic cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we found that CQ induced the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), a classical marker of the activation of intrinsic apoptosis (Fig. 4A), which suggested that CQ triggered mitochondrial apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Chloroquine (CQ) treatment induces the apoptosis of liver cancer cells. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ for 72 h. (A) Apoptosis was determined by Annexin V-FITC/PI double-staining analysis. Caspase-3 activity was analyzed by FACS (B) and cleaved PARP and caspase-3 were detected by western blot analysis (C).

Figure 4.

Chloroquine (CQ) induces mitochondrial apoptosis. (A) Treatment with CQ led to mitochondrial membrane depolarization. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ. Mitochondrial membrane depolarization was detected with mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1, according to the manufacturer's protocol. All data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Effects of CQ on the expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ for 72 h and subjected to western blot analysis using antibodies against pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins. GAPDH served as a loading control.

To further explore the potential mechanism of apoptosis, we systematically investigated the effect of CQ on the expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins. Among these proteins, pro-apoptotic protein Bim was substantially upregulated in both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B), suggesting that Bim may be critical for CQ-mediated apoptosis.

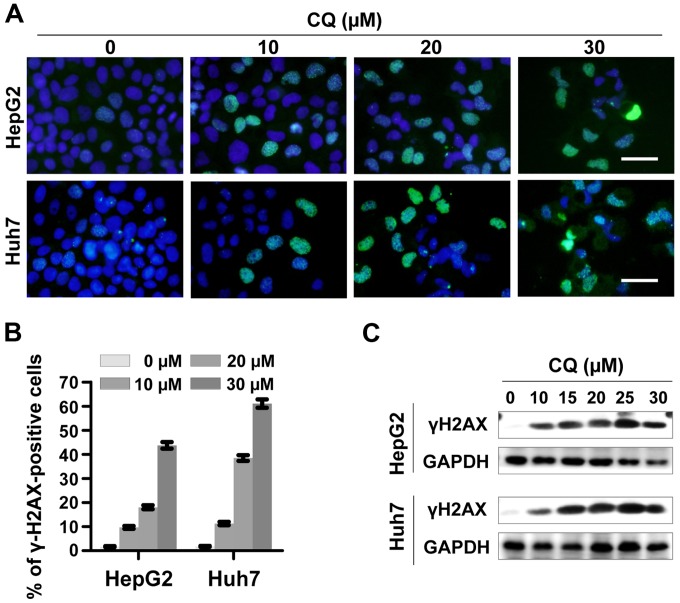

CQ induces DNA damage response

To determine whether CQ induces DNA damage response, we examined the expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX), a surrogate marker of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) by immunofluorescence and western blotting. CQ induced rapid and sustained γH2AX foci in the HepG2 and Huh7 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A and B), which was further confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Treatment with chloroquine (CQ) induces DNA damage. (A and B) γH2AX foci were determined by immunofluorescence. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ at the indicated concentrations. γH2AX foci were determined by immunofluorescence. Representative images are shown in A. (B) Cells with >10 foci were counted and the quantified data were plotted. Scale bar, 0.5 µm. (C) The expression of γH2AX was determined by western blot analysis. HepG2 and Huh7 cells were treated with CQ at the indicated concentration for 72 h. Cell extracts were subjected to western blot analysis for γH2AX. GAPDH served as a loading control.

CQ inhibits the tumor growth of liver cancer in vivo

Based on the above in vitro results, we next explored the potential anticancer effect of CQ in vivo in an orthotopic xenograft model of liver cancer. As expected, CQ led to a substantial decrease in tumor growth and weight, compared with the vehicle control (Fig. 6A–D), while little effect on the body weight of mice was noted (Fig. 6E). Moreover, a significant reduction in the proliferation marker Ki-67 and an increase in cleaved PARP were observed in the mouse tumors following treatment with CQ (Fig. 6F), suggesting that CQ effectively inhibited tumor growth in vivo by inhibiting liver cancer cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis.

Figure 6.

Antitumor efficacy of chloroquine (CQ) in vivo. (A and B) CQ significantly inhibited tumor growth as determined by fluorescence imaging. Nude mice with HepG2-GFP orthotopic human liver cancer were administered CQ according to Materials and methods. (A) Tumor size was monitored twice a week by fluorescence imaging. Scale bar, 1 µm. (B) The data were converted to tumor growth curves. (C and D) CQ treatment significantly reduced tumor volume. Mice were sacrificed on the 25th day after treatment (the end of study, n=7). Tumor tissues were harvested, photographed (C) and weighed (D). (E) No obvious toxicity against body weight gain was observed during treatment. The body weight of animals was measured twice a week during the treatment period. (F) CQ treatment decreased the expression of Ki-67 and enhanced the expression of cleaved PARP in vivo. Tumor tissues were collected; paraffin-embedded. The expression of Ki-67 and cleaved PARP was detected using immunochemistry. Scale bar, 20 cm.

Discussion

Recently, CQ has been widely used as a sensitizer of radiotherapy and chemotherapy (5,6,8,9). CQ was found to significantly promote the efficiency of traditional chemotherapy drug [such as oxaliplatin (5,6)] or tumor targeting drugs [such as sorafenib (18,19), MLN4924 (15), proteasome inhibitors (4)] in HCC xenografts. CQ was also found to enhance the efficacy of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in a rabbit VX2 liver tumor model (7). However, the antitumor effects and the related mechanisms of single CQ treatment for liver cancer have not been defined. In the present study, we assessed and validated the efficacy of a single treatment of CQ on liver cancer cells in vitro and in an orthotopic xenograft of human liver cancer in vivo. CQ had a profound effect on liver cancer cell viability, induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and promoted liver cancer cell apoptosis in both HepG2 [wild-type-p53 (20,21)] and Huh7 [mutant-p53 (20,21)] cells.

Previous studies have shown that single treatment of CQ exerted an antitumor effect in several types of tumors in a cell type-dependent manner (22–24). CQ could induce cell death in a subset of tumor cell lines; but the underlying molecular target and mechanism are still not fully understood. Recently, Lakhter et al reported that CQ promoted the apoptosis of melanoma cells by stabilizing PUMA in a lysosomal protease-independent manner (10). In the present study, we found that treatment with CQ induced DNA damage, which is in accordance with previous studies that CQ induces a genotoxic effect (25,26). Further investigation of the mechanism showed that CQ treatment led to loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which suggests that CQ treatment induces mitochondrial apoptosis in liver cancer cells. By analyzing the balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, we found that CQ treatment led to significant upregulation of pro-apoptotic protein Bim in a dose-dependent manner. As a member of the BH3-only proteins, Bim upregulation triggered cytochrome c release from mitochondria and consequently induced the activation of pro-caspase-9 (27). Previous studies have shown that targeting Bim may be an effective therapeutic strategy (27). Treatment of tumor cells, such as colorectal cancer and melanoma cell lines, with an inhibitor of the BRAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway increases the expression of Bim and induces Bim-dependent cell death (28–30). It was also reported that Bim plays an important role in gefitinibinduced cell death (31). These studies suggest that Bim is a critical mediator of drug-induced apoptosis, which perhaps plays an important role in CQ-induced apoptosis in liver cancer cells.

Together, our studies showed that single treatment of CQ effectively suppressed the growth of liver cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by triggering G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, inducing DNA damage and apoptosis in liver cancer cells. These findings extend our understanding and propose the use of CQ for the treatment of liver cancer in single treatment or in combination.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Grant of China (grant nos. 81001102 and 81101894), and the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Henan Province, China (grant no. 15A310024)

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chong CR, Sullivan DJ., Jr New uses for old drugs. Nature. 2007;448:645–646. doi: 10.1038/448645a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Bari MA. Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: New directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1608–1621. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui B, Shi YH, Ding ZB, Zhou J, Gu CY, Peng YF, Yang H, Liu WR, Shi GM, Fan J. Proteasome inhibitor interacts synergistically with autophagy inhibitor to suppress proliferation and induce apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:5560–5571. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding ZB, Hui B, Shi YH, Zhou J, Peng YF, Gu CY, Yang H, Shi GM, Ke AW, Wang XY, et al. Autophagy activation in hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to the tolerance of oxaliplatin via reactive oxygen species modulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6229–6238. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du H, Yang W, Chen L, Shi M, Seewoo V, Wang J, Lin A, Liu Z, Qiu W. Role of autophagy in resistance to oxaliplatin in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:143–150. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao L, Song JR, Zhang JW, Zhao X, Zhao QD, Sun K, Deng WJ, Li R, Lv G, Cheng HY, et al. Chloroquine promotes the anticancer effect of TACE in a rabbit VX2 liver tumor model. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:322–330. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang X, Tang J, Liang Y, Jin R, Cai X. Suppression of autophagy by chloroquine sensitizes 5-fluorouracil-mediated cell death in gallbladder carcinoma cells. Cell Biosci. 2014;4:10. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratikan JA, Sayre JW, Schaue D. Chloroquine engages the immune system to eradicate irradiated breast tumors in mice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakhter AJ, Sahu RP, Sun Y, Kaufmann WK, Androphy EJ, Travers JB, Naidu SR. Chloroquine promotes apoptosis in melanoma cells by inhibiting BH3 domain-mediated PuMA degradation. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2247–2254. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geng Y, Kohli L, Klocke BJ, Roth KA. Chloroquine-induced autophagic vacuole accumulation and cell death in glioma cells is p53 independent. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:473–481. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan C, Wang W, Zhao B, Zhang S, Miao J. Chloroquine inhibits cell growth and induces cell death in A549 lung cancer cells. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:3218–3222. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang PD, Zhao YL, Deng XQ, Mao YQ, Shi W, Tang QQ, Li ZG, Zheng YZ, Yang SY, Wei YQ. Antitumor and antimetastatic activities of chloroquine diphosphate in a murine model of breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahim R, Strobl JS. Hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and all-trans retinoic acid regulate growth, survival, and histone acetylation in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:736–745. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32832f4e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Hu T, Liang Y, Jiang Y, Pan Y, Li C, Zhang P, Wei D, Li P, Jeong LS, et al. Synergistic inhibition of autophagy and neddylation pathways as a novel therapeutic approach for targeting liver cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9002–9017. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman RM. The multiple uses of fluorescent proteins to visualize cancer in vivo. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:796–806. doi: 10.1038/nrc1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman RM, Yang M. Whole-body imaging with fluorescent proteins. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1429–1438. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer TD, Wang JH, Vlada A, Kim JS, Behrns KE. Role of autophagy in differential sensitivity of hepatocarcinoma cells to sorafenib. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:752–758. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i10.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi YH, Ding ZB, Zhou J, Hui B, Shi GM, Ke AW, Wang XY, Dai Z, Peng YF, Gu CY, et al. Targeting autophagy enhances sorafenib lethality for hepatocellular carcinoma via ER stress-related apoptosis. Autophagy. 2011;7:1159–1172. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brito AF, Abrantes AM, Pinto-Costa C, Gomes AR, Mamede AC, Casalta-Lopes J, Gonçalves AC, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, Tralhão JG, Botelho MF. Hepatocellular carcinoma and chemotherapy: The role of p53. Chemotherapy. 2012;58:381–386. doi: 10.1159/000343656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller M, Strand S, Hug H, Heinemann EM, Walczak H, Hofmann WJ, Stremmel W, Krammer PH, Galle PR. Drug-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells is mediated by the CD95 (APo-1/Fas) receptor/ligand system and involves activation of wild-type p53. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:403–413. doi: 10.1172/JCI119174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balic A, Sørensen MD, Trabulo SM, Sainz B, Jr, Cioffi M, Vieira CR, Miranda-Lorenzo I, Hidalgo M, Kleeff J, Erkan M, et al. Chloroquine targets pancreatic cancer stem cells via inhibition of CXCR4 and hedgehog signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1758–1771. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Y, Zhao YL, Deng X, Yang S, Mao Y, Li Z, Jiang P, Zhao X, Wei Y. Chloroquine inhibits colon cancer cell growth in vitro and tumor growth in vivo via induction of apoptosis. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:286–292. doi: 10.1080/07357900802427927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim EL, Wüstenberg R, Rübsam A, Schmitz-Salue C, Warnecke G, Bücker EM, Pettkus N, Speidel D, Rohde V, Schulz-Schaeffer W, et al. Chloroquine activates the p53 pathway and induces apoptosis in human glioma cells. Neuro oncol. 2010;12:389–400. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farombi EO. Genotoxicity of chloroquine in rat liver cells: Protective role of free radical scavengers. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2006;22:159–167. doi: 10.1007/s10565-006-0173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krajewski WA. Alterations in the internucleosomal DNA helical twist in chromatin of human erythroleukemia cells in vivo influences the chromatin higher-order folding. FEBS Lett. 1995;361:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akiyama T, Dass CR, Choong PF. Bim-targeted cancer therapy: A link between drug action and underlying molecular changes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3173–3180. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillings AS, Balmanno K, Wiggins CM, Johnson M, Cook SJ. Apoptosis and autophagy: BIM as a mediator of tumour cell death in response to oncogene-targeted therapeutics. FEBS J. 2009;276:6050–6062. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wickenden JA, Jin H, Johnson M, Gillings AS, Newson C, Austin M, Chell SD, Balmanno K, Pritchard CA, Cook SJ. Colorectal cancer cells with the BRAFv600E mutation are addicted to the ERK1/2 pathway for growth factor-independent survival and repression of BIM. Oncogene. 2008;27:7150–7161. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cartlidge RA, Thomas GR, Cagnol S, Jong KA, Molton SA, Finch AJ, McMahon M. Oncogenic BRAFv600E inhibits BIM expression to promote melanoma cell survival. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008;21:534–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cragg MS, Kuroda J, Puthalakath H, Huang DC, Strasser A. Gefitinib-induced killing of NSCLC cell lines expressing mutant EGFR requires BIM and can be enhanced by BH3 mimetics. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1681–1690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]