Abstract

At physiological temperatures, enzymes exhibit a broad spectrum of conformations, which interchange via thermally activated dynamics. These conformations are sampled differently in different complexes of the protein and its ligands, and the dynamics of exchange between these conformers depends on the mass of the group that is moving and the length scale of the motion, as well as restrictions imposed by the globular fold of the enzymatic complex. Many of these motions have been examined and their role in the enzyme function illuminated, yet most experimental tools applied so far have identified dynamics at time scales of seconds to nanoseconds, which are much slower than the time scale for H-transfer between two heavy atoms. This chemical conversion and other processes involving cleavage of covalent bonds occur on picosecond to femtosecond time scales, where slower processes mask both the kinetics and dynamics. Here we present a combination of kinetic and spectroscopic methods that may enable closer examination of the relationship between enzymatic C-H→C transfer and the dynamics of the active site environment at the chemically relevant time scale. These methods include kinetic isotope effects and their temperature dependence, which are used to study the kinetic nature of the H-transfer, and 2D IR spectroscopy, which is used to study the dynamics of transition-state- and ground-state-analog complexes. The combination of these tools is likely to provide a new approach to examine the protein dynamics that directly influence the chemical conversion catalyzed by enzymes.

2. Introduction

a. General

First, we wish to state up front that like most researchers studying enzyme-catalyzed reactions, we do not address “catalysis”, i.e., the ratio of the rates of the catalyzed reaction and the uncatalyzed reaction. The reason is mostly practical, namely that enzyme catalyzed C-H activations do not commonly have a relevant uncatalyzed model reaction with which to compare. A few exception where model reactions were examined are presented in ref 1 and refs cited therein. Below, we address studies of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction, and, more specifically, redox reactions involving hydride transfer.

The focus of this review is on the role of fast motions, on the femtosecond to picosecond time scale, in the H-transfer involved in C-H activation by enzymes catalyzing hydride, hydrogen, and proton transfer. The role of large motions of the protein, at the time scale of enzyme turnover (i.e., milliseconds to seconds), is well established and broadly accepted by the scientific community. These motions are mostly associated with substrate binding (i.e., “induced fit”) and product release. Studies of protein dynamics at faster time scales (microsecond to femtoseconds), on the other hand, are still in their infancy, and no single working model is broadly accepted by all researchers. While there is little doubt that proteins, like any other molecule at physiological temperatures, move and fluctuate at these fast time scales, the role of these motions in the catalyzed reaction is not fully understood. Different studies, both experimental and theoretical, lead to diverse conclusions, commonly based on the focus, strengths, and limitations of the methods applied. For example, NMR relaxation experiments examine the environmental dynamics that are coupled to the spins under study at microsecond to nanosecond time scales (µs-ns). These measurements are lengthy and use the apo-enzyme or a stable enzymatic complex that may or may not resemble one of the kinetic intermediates along the catalytic path. These studies of protein dynamics naturally monitor motions that are in thermal equilibrium (“statistical dynamics”)2 and exclude examination of motions that may not reach thermal equilibrium at the transition state. The same limitation is common to computer simulations focused on the potential of mean force (PMF) along the reaction coordinate. Nevertheless, recent calculations suggest that the relaxation to thermal equilibrium in a protein approaching the transition state may require 100 fs or more.2 Since some chemical events are faster than that time scale (e.g., QM tunneling), it is not possible to exclude the possibility that nonequilibrium fluctuations of the enzyme as it approached the transition state may affect the chemistry. It is difficult to experimentally examine dynamics that are not in equilibrium (i.e., “non-statistical” or “nonequilibrium” dynamics) let alone determine if such dynamics play a role in the catalyzed reaction. 2D IR spectroscopy measures the relaxation of equilibrium fluctuations in the enzyme active site, which, within the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, should also reflect the time scale for relaxation of nonequilibrium fluctuations. Concluding that nonequilibrium motions can persist on time scales longer than the chemical step, however, is neither evidence that such motions exist nor that they play any role in controlling the chemical kinetics.

Most kinetic models and rate theories, including those used by us, if they are sufficiently complex, can rationalize, and sometimes even qualitatively fit, the experimental kinetics, without invoking “nonequilibrium dynamics”. Frequently, these models and mathematical expressions are complex and involve more parameters than experimental data points. For non-adiabatic systems (most hydrogen radical transfer, or proton coupled electron transfer3), the C-H bond is not at all activated until the system is rearranged to the tunneling ready state (TRS, see more below). Although the rearrangement of the system toward TRS might be at the µs time scale, the actual bond activation occurs at the femtosecond time scale. Consequently, methods to study either statistical or nonequlibrium dynamics that are affecting/sensed by/or coupled to the reaction must be able to probe those motions at the chemically relevant time scale, femtosecond to picoseconds. Below we present studies attempting to both measure such dynamics and correlate these to the nature of the H-transfer step and its kinetics. Since the dynamics discussed below are measured spectroscopically, they require examination of a stable state. We try to examine states involving a TS-analog or other enzymatic complexes relevant to the reaction under study. Then we will try to pursue correlation between these fast dynamics, and kinetic properties, or the nature of the fast H-transfer step in the same enzymatic system.

b. Kinetics

The nature of the C-H→C transfer and its TS can be probed by three experimental approaches: measurements of the reaction rate (related to ΔG‡), kinetic isotope effects (KIEs, related to ΔΔG‡i-j. where i and j are the light and heavy isotopes, respectively), and linear free energy relationships (relating ΔG‡ to ΔG°, which will not be discussed further in this review). This review will focus on KIEs as a means to assess the nature of the enzyme catalyzed H-transfer. An advantage of measuring KIEs on the chemical step, as opposed to rate measurements, is that they connect more easily to calculations and simulations. Most theoretical simulations of enzyme catalyzed reactions focus only on a single step, i.e., the TS of the bond cleavage and the two stable states that it connects (reactant and product states). The absolute ΔG‡ calculations suffer from the fact that the contributions to the free energy involve hundreds of kcal/mol, but most enzymatic ΔG‡s are below 20 kcal/mol. Thus, the accuracy of the unparameterized rate calculation is often quite low. KIEs, on the other hand, are only sensitive to the few isotopically sensitive parameters and often involve the fortuitous cancelation of many of the inherent errors in the calculated free energies. Thus, KIEs provide a much more reliable assessment of the accuracy of the calculated PMF and the predicted progress of the reaction over and through the barrier.

From a kinetic point of view, examination of the chemical step (i.e., covalent bond cleavage and formation) in the complex kinetic cascade of most enzymes is a major challenge. Since most enzymes evolved under conditions other than saturation of their substrate, the turnover number measured for enzymes (kcat, measured under substrate saturation) is frequently rate limited by product release rather than by the chemistry. Under steady state conditions, the second-order rate constant in enzymatic reactions (kcat/KM, measured at very low substrate concentration) is also not typically rate limited by the chemical step, but rather by events associated with substrate binding, or induced fit motions (e.g., large scale conformational changes that follow the binding step) etc.

From an experimental point of view KIEs are measured using two basic approaches: (i) non-competitive KIEs, and (ii) competitive KIEs. The first method consists of rate measurements with two different isotopologues (i.e., reactants that only differ in their isotopic composition), followed by calculation of the ratio of the rate constants. The second method directly measures the KIE through the competition of both isotopologues in the same vessel by following the enrichment of the heavier isotope in the reactants or its depletion in the product. Although the second approach does not provide rate information and is limited to measurements of the KIE on the second order rate constant,4 it is also not subject to artifacts involving different contaminations or different conditions in the two measured rates that are common problems in the first method. Additionally, the competitive approach affords the use of trace amounts of tritium (competing with H or D) eliminating the need for “carrier free” tritiated reactant (i.e., pure T with no H or D contamination) that would be needed for non-competitive tritium KIEs. This last issue indeed dictates that when triple isotopic labeling is required for the application of Northrop’s method (see Eq. 2 below), a competitive KIE measurement is commonly used.

1) Kinetic Complexity

In studying C-H→C transfer, the advantage of KIEs is that the isotopic label is placed on a C-H bond that has little contribution to binding events, but has a substantial effect on the H-transfer, the potential energy surface along the reaction coordinate, the chemical character of the TS, and the nature of the barrier crossing can all be examined. Such KIEs involve hydrogens that are transferred in the chemical step (i.e., 1°KIEs) or are changing bond order during the transfer of another hydrogen (i.e., 2° KIEs). Unfortunately, observed KIEs are often “masked” by kinetic complexity. An example of the relationship between the observed KIE and its intrinsic value (assuming only the chemical step is isotopically sensitive), is given below for the second order rate constant, which is used in most of the case studies presented below.

When measuring KIEs, in particular, one has to bear in mind that the observed KIEs can be obscured by “kinetic complexity”, where partially rate-limiting steps that are not isotopically sensitive diminish the observed KIE relative to the value of the “intrinsic” KIE on the step of interest.5 The observed KIE i(V/K)j, where j is the lighter hydrogen isotope and i is the heavier one) is related to the intrinsic KIE by the equation:

| [1] |

where (kj/ki)int is the intrinsic KIE and EIE is the equilibrium isotope effect or the isotope effect on the equilibrium constant of the reaction. The terms Cfand Cr are the forward and reverse kinetic commitments to catalysis, respectively. Cf reflects the ratio of the forward rate of the isotopically sensitive step (the step of interest) to the net reverse rate of the non-isotopically sensitive steps that precede this step.6 Similarly, Cr reflects the reverse rate of the isotopically sensitive step to the net forward rate of the non-isotopically sensitive steps that follow this step. For an irreversible reaction, Cr = 0 and all the “kinetic complexity” is caused by Cf from the preceding steps. Analyzing the kinetic commitments can sometimes provide information on the reaction mechanism, as will be seen in the context of TSase below.

Experimentally, examination of the chemical step is challenging because most mature wild-type enzymes when catalyzing the reaction with their natural substrate under physiological conditions, are not rate limited by the chemical step. With careful experimental design and/or isotopic labeling, the chemical step is the only isotopically sensitive one, as in the comparison of C-H to C-D bonds cleaved in large biological molecules that are not otherwise different. In many cases, exposure of the isotopically sensitive step also requires the use of non-natural substrates, an active site mutation(s), or both (e.g., alcohol dehydrogenases)7.

Pre-steady state measurements are another way to remove some of the kinetic complexity. These experiments are designed to exclude effects from substrate binding and product release. These measurements focus on kinetic steps between the formation of the complex where the enzyme is already bound to all reactants (typically a binary or ternary complex), and the formation of the enzyme-bound product. Nevertheless, the measured rates often reflect the impact of other effects including conformational changes, pKa and protonation shifts, and other microscopic kinetic contributions that can still mask the chemical step. For example, many nicotinamide-dependent enzymes bind the adenine-pyrophosphate moiety of this cofactor first, followed by major conformational changes of the protein and rotation of the reactive nicotinamide ring into the active site prior to reaching the ground state of the chemical step.

For systems where these solutions are not effective an instrumental approach is to use Northrop’s method for finding intrinsic KIEs based on a combination of deuterium and tritium KIEs as is represented by the equation:8,9

| [2] |

In this equation T(V/K)D and T(V/K)H are the observed D/T and H/T isotope effects on the second order rate constant kcat/KM, respectively, and (kH/kT)int is the intrinsic H/T KIE on the chemical step of interest. Although this method uses the Swain-Schaad relationship and relies on several assumptions,10 its applicability to systems where tunneling is known to be important has been addressed and confirmed experimentally.9 A simple way to understand the Northrop Method, is that the reference isotope (tritium in Eq. 2) affords the intrinsic comparison of the ratio of kH to kD, i.e., the intrinsic KIE. It is important to note that the reference isotope is not limited to tritium (as in Eq. 2) but any of the three isotopes of hydrogen could serve as the reference.9

2) Temperature dependence of KIEs

The temperature dependence of KIEs (TDKIEs) reveals the differences in the enthalpies and entropies of activation for the two isotopes (ΔΔH°, or ΔEa and Aj/Ai, respectively). Since both isotopes share the same potential energy surface, these activation parameters reflect the nature of the reaction coordinate under study. This temperature dependence has been analyzed by a variety of theoretical approaches. Semiclassically, ΔEa reflects the difference in zero-point-energies (ZPE) for the two isotopes at the ground state (GS) as compared to the transition state (TS), and Aj/Ai should be close to unity.11,12 If a tunneling correction is added to the semiclassical model, it can be calculated using either a simple parabolic approximation (e.g. the Bell correction),13 or assuming more complex potential surfaces.14 Although such corrections can explain many observations, they cannot address other features such as temperature independent KIEs with a significant energy of activation. One model that enables a simple fit of such data is the Limbach-Bell correction, in which the Bell tunneling correction to the TST rate13 is further corrected by fitting the mass of the transferred particle as a parameter.15 Fitting this model to temperature independent KIEs with significant ΔEa results in isotopic masses that are much higher than those of H, D or T. These large masses are in accordance with coupling of the transferred particle to larger system, but provide limited physical meaning. Approaches that separate the temperature dependence of the rate from that of the KIEs reflect more realistic, multidimensional models of the reaction and are all summarized here as the Marcus-like model.

Marcus-like models assume a priori that the hydrogen atom is light enough that a full quantum mechanical treatment including quantum tunneling is necessary to adequately describe the reaction. The prevailing model of reactivity, then, is an extension of the Marcus theory of electron tunneling,16 where the tunneling particle is a hydrogen rather than an electron. This model, which has been described under different names (Marcus-like models,17 environmentally coupled tunneling,18 full-tunneling model,19 vibrationally enhanced tunneling,20etc.), proposes a mechanism where heavy atom reorganization leads to a “Tunneling Ready State” (TRS) in which the quantum states of the hydrogen in the reactant and product wells are degenerate, and, thus, the hydrogen can transfer to products via tunneling. This TRS becomes the transition state for H-transfer. Several groups have independently derived a functional form for the rate constant (k) for an H-transfer reaction within this model, which is given by the expression:3,18,21–23

| [3] |

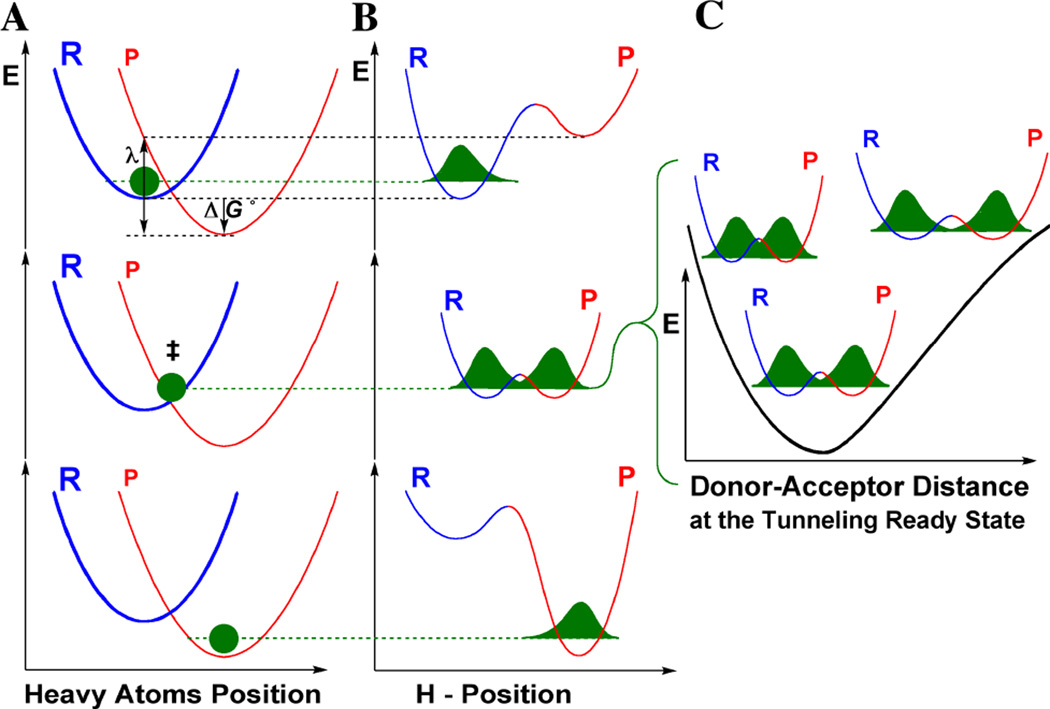

In this equation, the terms in front of the integral give the standard Marcus Theory 16 rate for reaching the TRS (Figure 1A) based on the electronic coupling (V), the reorganization energy (λ), the driving force for the reaction (ΔG°), and the absolute temperature (T). The additional term C(T) is the fraction of reactive complexes24 to account for the conformational landscape that brings the H-donor and acceptor to their chemical ground state. The terms in front of the integral are essentially insensitive to the mass of the transferring particle, so the KIE is determined by factors within the integral. The integral gives the probability of tunneling from the reactant well to the product well once the system reaches the TRS (the middle state in Figure 1A and 1B). The first term in the integral is the probability of tunneling for a particle with mass m as a function of the donor-acceptor distance (DAD). This probability is multiplied by a Boltzmann factor (second term) that gives the probability of finding the system at a particular DAD. This product is integrated over all DADs to yield the total tunneling probability. An important characteristic of this model is that the entire system is assumed to be in thermal equilibrium. In many previous publications, the use of the word “dynamics” simply referred to “motions” without distinguishing between motions that are in thermal equilibrium (i.e., “statistical dynamics”) and those that are not, i.e. non-statistical dynamics.2, 17, 19, 25, 26 This imprecise language subsequently led some to believe that a controversy exists over whether true non-equilibrium dynamics contribute to enzyme-catalyzed reactions.27, 28 Although several such proposals do exist,2 the Marcus-like models do not require and thus do not invoke non-equilibrium dynamics.

Figure 1.

Marcus-Like models of hydrogen tunneling. Three slices of the potential energy surface (PES) along components of the collective reaction coordinate showing the effect of heavy-atom motions on the zero point energy in the reactant (blue) and product (red) potential well. Panel A presents the heavy atoms coordinate, and Panel B the H-atom position. In the top panel, the hydrogen is localized in the reactant well, and the energy of the product state is higher than that of the reactant state. Heavy atom reorganization brings the system to the tunneling ready state (TRS, middle state in panels A and B), where the zero point energy levels in the reactant and product wells are degenerate and the hydrogen can tunnel between the wells, for short donor-acceptor distances (DADs). Panel C presents the effective potential surface (EPS) along the DAD coordinate at the TRS. Further heavy atom reorganization breaks the transient degeneracy and traps the hydrogen in the product state (bottom panel). The rate of reaching the TRS depends on the reorganization energy (λ) and driving force (ΔG°), which are indicated in the top panel, and further discussed under Eq. 3. Panel C shows the effect of DAD sampling on the wavefunction overlap in the TRS. Tunneling probability is proportional to the overlap integral of the hydrogen wavefunctions in the reactant (blue) and product (red) wells, which depends on the DAD.

c. 2D IR Spectroscopy

Assessment of the potential for a functional role for fast motions of the protein in the catalyzed reaction requires a way to characterize enzyme motions and to specifically identify those motions that directly affect the reactive complex when it is at the TRS. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy (2D IR) is a spectroscopic tool that has emerged over the past decade and has seen applications to a wide range of problems.29 2D IR can directly characterize protein dynamics at the enzyme active site at the time scale of hundreds of femtoseconds (fs) to tens of picoseconds (ps). Thus, 2D IR spectroscopy allows direct observation of the protein dynamics at the enzyme active site at the time scale that is most relevant for the catalyzed C-H→C transfer.

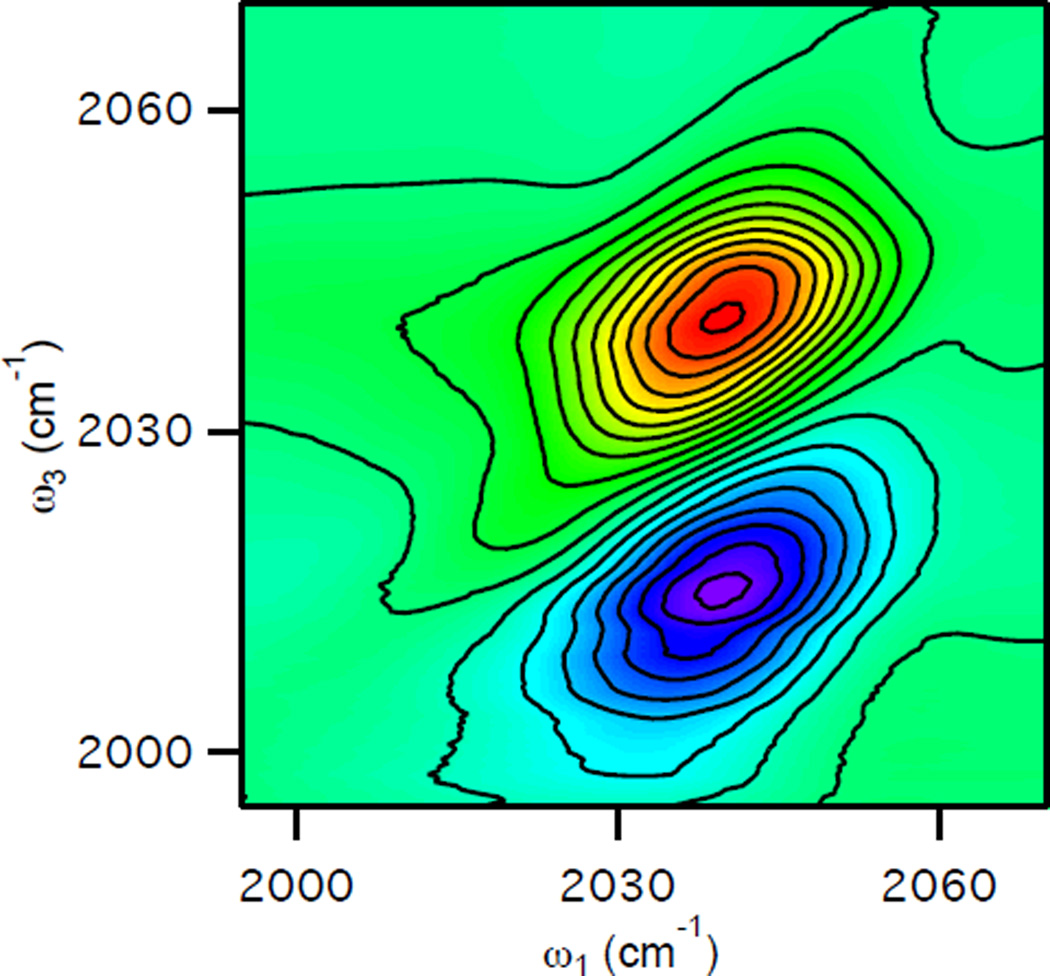

2D IR spectroscopy is an optical analog of 2D NMR spectroscopy. Specifically, when applied to problems involving dynamics, 2D IR measures correlations in a way that is directly analogous to a COSY experiment. The 2D IR spectrum is two-dimensional in that it displays the intensity of the signal as a function of two frequencies: the excitation frequency, ω1, and the detection frequency, ω3. Figure 2 shows an example of a 2D IR spectrum of azide in D2O. There are two types of signal contributions giving rise to two oppositely signed peaks in the 2D IR spectrum. Both of these peaks result from the change in absorbance of the sample as a result of the interactions with the excitation pulses. The excitation moves population from the ground state of the oscillators to the vibrationally excited state, and the probe pulse measures the change in absorbance resulting from the excitation. In the ω1 axis, both peaks appear at the fundamental transition frequency.

Figure 2.

2D IR spectrum of azide in D2O at Tw = 100 fs illustrating the two types of signals in a typical 2D IR spectrum.

Moving population out of the ground state into the first excited state causes a decrease in the absorbance of the probe beam. This signal is often referred to as a ground-state-bleach signal. In addition, the excited population can undergo stimulated emission as a result of the interaction with the probe pulse, giving rise to a signal that also behaves like a decrease in absorbance. Together, the ground-state bleach and stimulated-emission signals produce the red peak centered on the diagonal (ω3=ω1), which, when plotted in transmittance, is a positive peak (decreased absorbance corresponds to increased transmittance). The other peak in the 2D IR spectrum (blue) results from the excited-state-absorption of the vibrationally excited molecules. Because molecular vibrations are anharmonic, the transition from the first excited state to the second excited state of the vibrational manifold of a real molecule will occur with an energy that is slightly less than the transition from the ground state to the first excited state. Thus, the increase in absorbance that results from the population of molecules in the first excited state occurs at a frequency in ω3 that is below that of the fundamental absorption from the ground state to the first excited state. Furthermore, because the excited-state-absorption signal causes an increase in absorbance, it is observed as a negative peak (decreased transmittance) in the 2D IR spectrum. Thus, the two peaks in the 2D IR spectrum of a single oscillator appear in ω3 at the frequency of the fundamental absorption, often called the 0–1 frequency, and at the anharmonically shifted excited-state absorption, often called the 1–2 frequency. Because these signals result from vibrational excitation of the molecules, which moves population from the ground state to the first-excited state, the 2D IR signals that give rise to these two peaks will decrease in amplitude as the excited vibrational population relaxes back to the ground state as we increase the time delay between excitation and detection pulses, Tw. In fact, the amplitude of the features in the 2D IR spectrum will decay exponentially as a function of increasing waiting time with a time constant T1 that reflects the first-order relaxation kinetics of the vibrational excited state. With protein samples, we can, in practice, measure 2D IR spectra for waiting times up to 5T1. As discussed below, analysis of the positive peak (in red) is sufficient to determine the environmental dynamics.

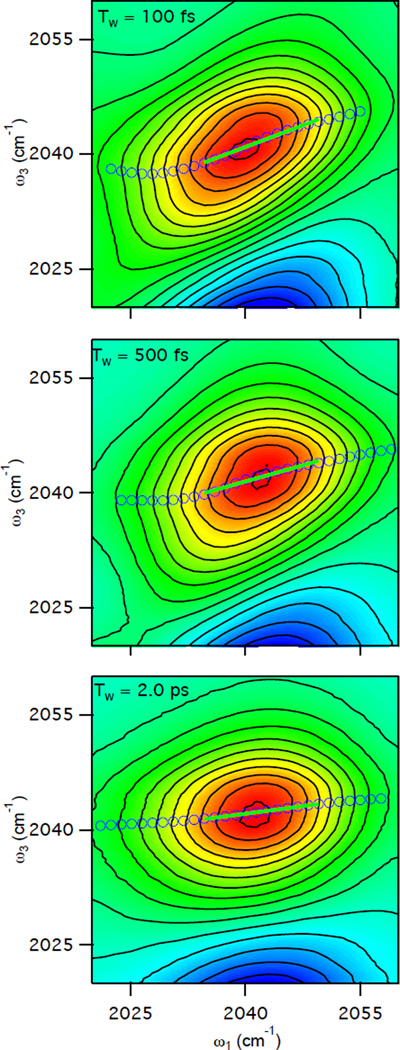

The important information in a 2D IR correlation spectrum is not found in the peak positions or amplitudes, however. Rather, the most useful information is found in the shapes of the peaks in the 2D IR spectrum. To understand the shapes of the peaks we first have to think about the behavior of an ensemble of identical oscillators in solution. In the gas phase, these identical oscillators have identical energy-level spacings and transition frequencies. In solution, however, each molecule experiences a slightly different solvent environment. The interactions with solvent molecules cause a slight shift in the energy levels of the oscillator. Thus, a distribution of identical oscillators in solution exhibits a distribution of transition frequencies. This distribution, however, is not static. The transition frequency for a particular molecule changes as a function of time as the molecule samples different solvent environments. This process by which molecules sample the distribution of frequencies is known as spectral diffusion. In a 2D IR experiment, the frequency distribution produces a line shape that is elongated parallel to the diagonal for short waiting times, Tw. For small enough Tw, a molecule that has a low transition frequency when it is excited in ω1 also has a low transition frequency when it is probed in ω3 because the molecule has not yet sampled other environments. The situation is similar for a high frequency oscillator. Thus, there is a strong correlation between the frequency in ω1 and the frequency in ω3 for small Tw delays. As a result the lineshapes of the peaks in the 2D IR spectrum are elongated along the diagonal at early waiting times. At larger waiting times, however, the molecules have an opportunity to sample different environments in between the excitation pulse pair and the probe pulse. As a result, the frequency in ω3 is increasingly less correlated with the frequency in ω1 as Tw increases and the line shape in the 2D IR spectrum tilts more towards the horizontal and becomes more rounded. Figure 3 shows a series of 2D IR spectra for increasing waiting times from top to bottom illustrating the effect of spectral diffusion as a function of the waiting time on the 2D IR line shapes.

Figure 3.

2D IR spectra of azide in D2O for waiting times (Tw) of 100 fs, 500 fs, and 2.0 ps illustrating the centerline slope (CLS) analysis of the 2D IR lineshape. The blue circles are the points of the centerline and the green line is the fit to these data from which we get the CLS.

The 2D IR line shape measures frequency correlations as a function of the waiting time. The loss of correlation between the frequencies in ω1 and ω3 reflects the spectral diffusion that results from the changes in environments around the oscillators in the sample. Thus, the time scales on which the line shape in the 2D IR spectrum changes are the time scales for the dynamics of the environment around the probe molecules. We quantify these time scales statistically using the frequency-frequency time correlation function (FFCF). Mathematically, the FFCF is defined as < δω(t)δω(0) > where the brackets indicate the ensemble average, and δω(t) is defined as ω(t)–< ω >, the instantaneous frequency of an oscillator minus the average of the frequency distribution. At t = 0, the FFCF gives the mean square of the frequency fluctuations. As t increases, the FFCF decays reflecting the loss of correlation between the frequency fluctuation at time t and its value at time 0.

The line shape of the 2D IR spectrum as a function of Tw is a quantitative measure of the FFCF. It is not trivial, however, to uniquely determine the FFCF from a series of 2D IR spectra. Among the many approaches to extracting the FFCF from 2D IR correlation spectra, one of the most straightforward and robust is the centerline slope (CLS) method first introduced by Kwak et al 30,31 The CLS is constructed by taking slices of the 2D IR spectrum for specific values of ω1 and determining the location of the maximum in ω3 for the slice. Thus, the centerline is the collection of values that correspond to the location of the maximum in ω3 for each value of ω1. For the 2D IR spectra shown in Figure 3, the blue markers show the points corresponding to the centerline, which is fit to a linear function as shown by the green line.

When the correlation between the frequencies of the oscillators in ω1 and ω3 is high, the centerline in aligned with the diagonal, and as the frequency correlations decay with increasing waiting times, the centerline rotates toward horizontal following the changes in the 2D IR lineshape. This evolution is characterized by the slop of the centerline, the CLS, which has a theoretical maximum value of 1 of the correlations in ω1 and ω3 are perfect. At large enough waiting times the CLS must decay to zero as the frequency correlations are lost completely as the molecules undergo spectral diffusion as a result of sampling the full distribution of environments. The time scales for the decay of the CLS, therefore, are a direct measurement of the time scale of the fluctuations of the environment. In general these time scales are quantitatively characterized from the CLS decay using a generalized Kubo lineshape function in which the decay of the FFCF is assumed to be multiexponential. Thus we fit the decay of the CLS to a sum of exponentials. Using the exponential time scales and their relative amplitudes from the decay of the CLS, we then fit the lineshape of the infrared absorption spectrum to determine the FFCF with the only adjustable parameters being the absolute amplitude of the FFCF and the motionally narrowed contribution to the lineshape. Thus , the FFCF will most often be reported in terms of amplitudes and time scales that correspond to a function of the form:

| [4] |

where the summation runs over as many terms as are necessary to characterize the FFCF decay. The A values give the amplitudes of the frequency fluctuations that contribute to the FFCF and the τ values give the time scales for those motions. The static contribution, given by the Δs term, is included to account for those motions that occur on time scales that are longer than the measurement time afford by the limits associated with population relaxation and are therefore not sampled within the accessible waiting times. Examples of fits to experimental data for Eq. 2 are given in below in items 4.a. and 5.b.

Thus, 2D IR spectra as a function of the waiting time allow us to uniquely determine the time scales of the environmental fluctuations about a probe molecule. In the study of enzyme dynamics, the probe molecule is chosen based on four properties:

Its ability to bind to the enzyme active site: The molecules must bind to the protein to report on enzyme dynamics, and the most relevant location to probe these motions is in the active site. Furthermore, if the molecule is a transition-state-analog inhibitor that is an added advantage in that the dynamics that are most relevant to the enzyme-catalyzed reaction will be those that occur in the transition-state complex. If the complex with the probe molecule bound mimics the transition-state complex well, then the measurements will better represent the dynamics of the most chemically relevant state of the enzyme.

The position of the transition frequency in the infrared spectrum: The probe molecule must also have its infrared transition in a suitable region of the infrared spectrum. Naturally, the solvent in enzyme dynamics experiments will be water, which has strong absorption bands throughout the infrared. The most suitable region for isolating a particular transition in an aqueous enzyme solution is between 1800 cm−1 and 2800 cm−1. There are relatively few potential chromophores that absorb in this region. The most commonly used candidates are triple-bonded small molecules or ions with absorptions associated with the triple-bond stretching motions around 2000 cm−1, such as carbon monoxide, nitriles, and azides.

The intensity of the infrared spectroscopic transition: The molecule must also have a strong transition moment for the relevant spectroscopic transition. The signal strength in 2D IR spectroscopy scales as the square of the molar absorptivity. Thus a weak chromophore will be very difficult to detect in 2D IR. This problem is amplified in measurements of enzyme dynamics because the maximum solubility of enzymes is typically on the order of 1 mM or less, which, although it is a large concentration for an enzyme, is a very small concentration for infrared spectroscopy. Consequently, with the current technology, it is best if the molar absorptivity of the spectroscopic transition of interest in the probe molecules is on the order of 1000 M−1 cm−1 or greater.

The population lifetime of the chromophore: The chromophore should also have a long population lifetime. As noted above, the population lifetime of the probe vibration sets an upper limit on the spectral diffusion time scales that are accessible by 2D IR spectroscopy. In practice, we can measure 2D IR spectra of proteins for waiting times up to 5 times the population lifetime. Because proteins can exhibit conformation dynamics over many decades of time, a probe molecule with a long vibrational lifetime provides access to dynamics on a much wider range of time scales.

3 Temperature dependence of KIEs in enzymes and solution

Several enzymatic and a few non-enzymatic systems have been examined using TDKIEs. A few examples of these systems are concisely presented here to demonstrate some applications of this methodology. The examples presented below focus on C-H bond activation via hydride or proton transfer (adiabatic processes) that are relevant to the studies of formate dehydrogenase (FDH) discussed in item 5:

a. Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR)

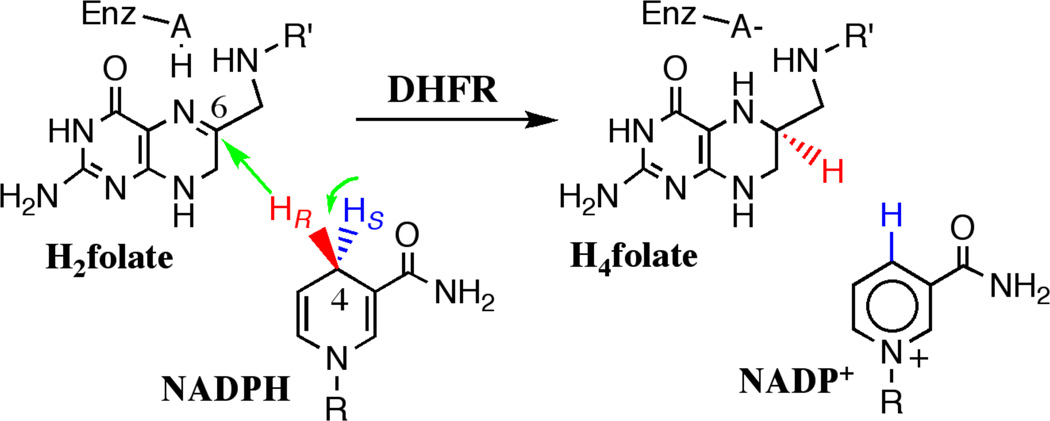

catalyzes a simple chemical transformation (Scheme 1): the NADPH-dependent reduction of 7,8-dihydrofolate (H2folate) to 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate (H4folate, Scheme 1). H4folate is an important cofactor in many biochemical processes including thymine (a DNA nucleotide) biosynthesis, and thus DHFR is a target for various antibiotic and chemotherapeutic drugs. DHFR has served as a platform for many theoretical studies (e.g. refs 2,3,32–38) and experimental studies (e.g. refs 26,39–42), and the relationship between protein dynamics and function have been specifically examined in DHFR.43–45 As a result, DHFR is an ideal model system for exploring basic physical features of enzymology. In spite of these advantages, the chemical step studied by theoreticians and illustrated in Scheme 1, is not the rate-limiting step of the enzymatic turnover and a lot of work has been invested in exposing that step and its intrinsic KIEs using the methods described above.41,46–48

Scheme 1.

The DHFR reaction. The  indicate the motion of the primary (

indicate the motion of the primary ( ) and secondary (

) and secondary ( ) hydrogens. R: adenine dinucleotide 2’-phosphate. R’: p-aminobenzoyl-glutamate.

) hydrogens. R: adenine dinucleotide 2’-phosphate. R’: p-aminobenzoyl-glutamate.

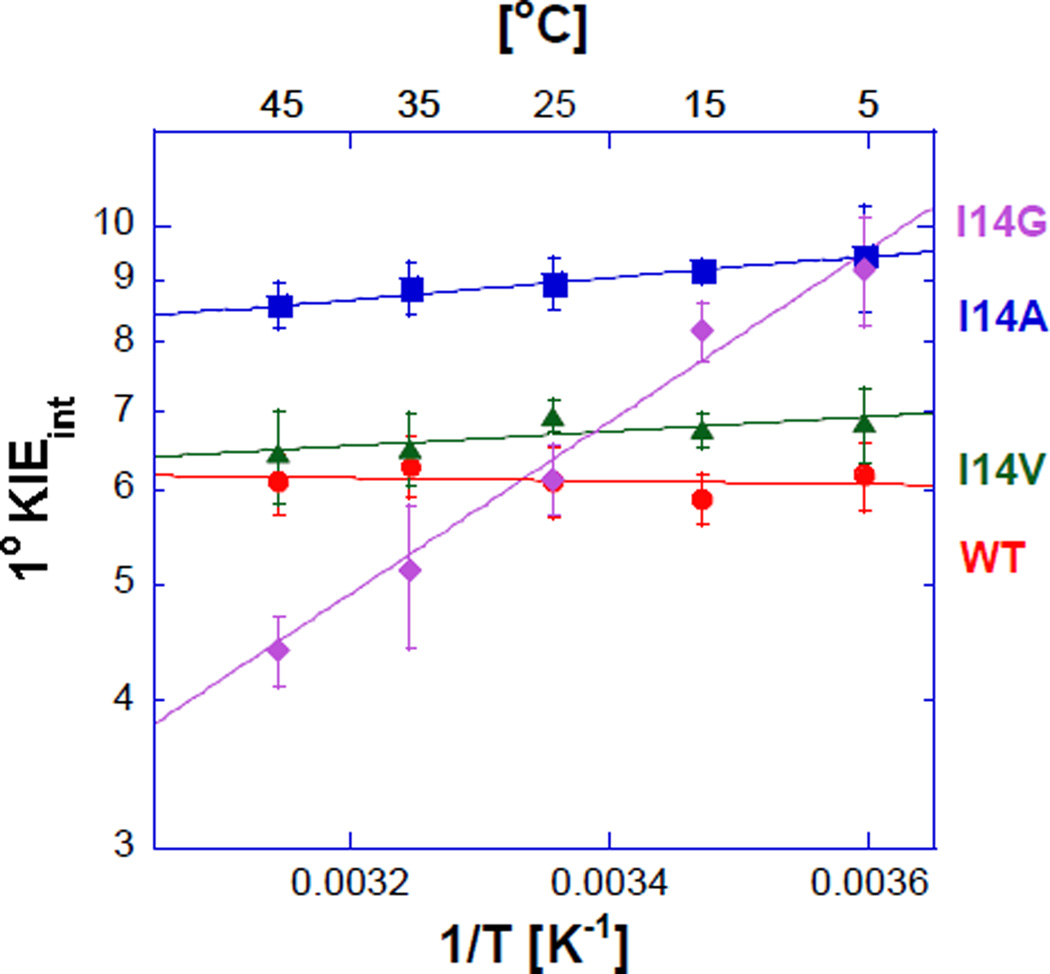

E. coli DHFR was used to study changes in the C-H→C transfer in response to a perturbation of the DAD. We altered the DAD and its dynamics by reducing the size of an active site isoleucine 14, located behind the H-donor, into valine, alanine, and glycine. These mutations minimize electrostatic changes, and a MD simulation indicated that the mutations primarily affect the distribution of DADs resulting in longer average values and a broader distribution (Figure 1.C.). Pre-steady-state kinetics indicate slower rates for smaller side-chain derivatives (table 1), in accordance with a smaller fraction of reactive conformations (CT in Eq. 3). Competitive H/T and D/T KIEs (in the 5–45 °C range) afford the intrinsic KIEs and their temperature dependence (Figure 4), which, together with the Arrhenius analysis, is provided in Table 1

Table 1.

Comparative kinetic parameters of the DHFR I14 mutants.

| Parameters | WT | I14V | I14A | I14G |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue volumea (Å3) | 124 | 105 | 67 | 48 |

| kHb [s−1] | 228 ±8 | 33.3 ±3.1 | 5.7 ±0.3 | 0.22 ±0.04 |

| AH/ATc | 7.0 ±1.5 | 4.2 ±0.4 | 4.7 ±0.5 | 0.024 ±0.003f |

| ΔEaT-Hc, [kcal/mol] | −0.1 ±0.2 | 0.27 ±0.05 | 0.39 ±0.06 | 3.31 ±0.07 |

Side chain volume.51

Presteady state rates of H transfer at 25°C and pH 7.

Similar trends were observed for H/D and D/T (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Arrhenius plot of intrinsic H/T KIEs (on a log scale) for A) wild-type (red), I14V DHFR mutant (green), I14A DHFR (blue) and I14G DHFR (purple). The lines represent the nonlinear regression to an exponential equation. Reproduced with permission from ref49.

These findings indicate a clear relationship between the DAD distribution and the temperature dependence of intrinsic KIEs. These local effects also enable a better understanding of remote mutations that indicate synergism between residues >15 Å away from the active site that are associated with a dynamic network of coupled motions across the protein that is coupled to the catalyzed chemistry.41,46–48 Although the earlier studies support the idea of a dynamic network suggested by three independent theoretical studies,2,42,50 the structural and dynamic effects of the remote mutations on the DAD were hard to assess without similar effects in active-site mutants and the associated MD simulation.49

b. Thymidylate synthase (TSase)

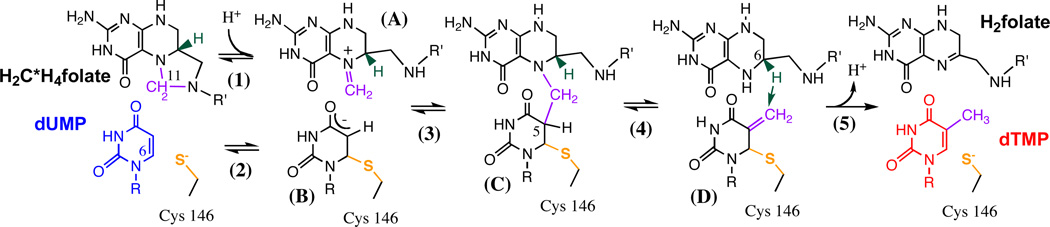

TSase catalyzes the last step of de novo synthesis of 2’-deoxythymidine0 −5’-monophosphate (dTMP, one of the four DNA bases), in which the substrate 2’-deoxyuridine-5’-monophosphate (dUMP) is methylated and reduced by the cofactor N5,N10-methylene-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate (CH2H4folate) (Scheme 2). The catalytic mechanism of TSase involves a series of bond cleavages and formations that include two different C-H bond activations: a reversible proton abstraction from C5 of the substrate, dUMP, and an irreversible, rate-limiting hydride transfer from C6 of the cofactor to C7 of the product, dTMP. Early mechanistic studies of TSase included steady state and pre-steady state kinetics, crystallography, and 1° and 2°-hydrogen isotope effects, etc., which have been summarized in a few excellent reviews.52–55 We studied the two C-H activation steps with both experimental and computational methods, and highlight here the integration of different approaches in addressing specific issues.56–63 In this section, KIEs refer to 1° KIEs, and TSase refers to the enzyme from E. coli, unless otherwise specified.

The hydride transfer (step 5 in Scheme 2): Spencer et al measured KIEs on the hydride transfer with steady state kinetic experiments of wild type TSase (wt TSase) at 20 °C.64 The authors observed a large 1° KIE (∼3.7) on both kcat and kcat/KM, suggesting that the hydride transfer step was rate limiting for the catalysis (i.e. lack of “kinetic complexity”). Subsequently, we measured intrinsic 1° KIEs on the hydride transfer step in the physiological temperature range (5–40 °C) of wt TSase.56 The small kinetic commitment (Eq. 1) observed on the hydride transfer supports the conclusions of Spencer et al that this step is rate limiting. Over the experimental temperature range (5–40 °C), the intrinsic KIEs are temperature independent (Figure 5A), and the isotope effects on the Arrhenius pre-exponential factors exceed the upper limit of semi-classical predictions. We also measured initial velocities for the reaction over the same temperature range, and observed a significant activation energy on kcat. This system is another example of an enzyme-catalyzed H-transfer with a temperature-dependent rate but temperature-independent KIEs, which is consistent with Marcus-like models but not with simple tunneling corrections to TST.

The proton transfer step (step 4 in Scheme 2): Compared with the rate-limiting hydride transfer, the proton transfer is a fast and reversible step and therefore its KIEs are greatly masked by the kinetic complexity. Previous studies used a saturating concentration of CH2H4folate and measured a 1° KIE of unity on the proton transfer due to the large kinetic commitment.55,65 We found that the observed KIE for this step varies with the concentration of CH2H4folate, owing to the sequential binding order of dUMP and CH2H4folate.58 Thus, we measured the KIEs on the proton transfer with a low concentration of CH2H4folate (yet high enough to ensure sufficient conversion of dUMP to dTMP),63 and intrinsic KIEs where assessed using Northrop’s method (Eq. 2). In contrast to the hydride transfer step, the intrinsic KIEs on the proton transfer are temperature-dependent (Figure 5B). The different temperature dependences of the KIEs on the two hydrogen transfer steps suggest that the enzyme employs different strategies in catalyzing the sequential C-H bond activations.63

Scheme 2.

TSase Catalyzed Reaction starts with Michael addition of Cys146 (step 2) and methylene transfer from methylenetetrahydrofolate (CH2H4folate) to deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) (step 3) followed by proton abstraction from C5 of dUMP and elimination of tetrahydrofolate (step 4), followed by hydride transfer to produce dihydrofolate (H2folate) and deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP) (step 5).

Figure 5.

Arrhenius plots of observed (open markers) and intrinsic (filled markers) primary KIEs on (A) the hydride transfer (step 5 in Scheme 2) and (B) the proton transfer (step 4 in Scheme 2) catalyzed by TSase. The hydride transfer (rate-limiting) presents temperature-independent KIEs, while the proton transfer presents temperature-dependent KIEs. This figure is modified from Ref 56 and Ref 63.

This is a unique example where two different C-H activation are examined in the same catalytic conversion and same active site. These findings indicate that the enzyme has evolve to carefully tune the rate limiting step (which does not happen in solution, suggesting an enormous catalytic effect), but that there is little intervention of the enzyme in the fast proton abstraction (which can be catalyzed in solution by high pH and thiols).

c. Aromatic amine dehydrogenase (AADH) and morphinone reductase (MR)

Scrutton, Sutcliffe, and coworkers have employed the temperature dependence of intrinsic KIEs to study several enzymatic systems. We discuss only one such study, for which the scope of methodologies ranged from kinetics to QM/MM examination of two enzymes. Masgrau et al.66 examined the reaction pathway for tryptamine oxidation by AADH using a combined experimental and theoretical approach. They were able to demonstrate that proton transfer in this system is dominated not by long-range promoting vibrations, but by short-range motions that modulate the distance between the proton and the acceptor oxygen atom. Similarly, Hay et al.67 used both temperature and pressure dependence measurements to study the reductive half-reaction of morphinone reductase (MR). This reaction has been proposed to involve hydride tunneling from NADH to the enzyme-bound cofactor flavin mononucleotide (FMN)68, and the measurement of the pressure-dependence of the 1° KIE for this system allowed the authors to suggest a full tunneling model for the hydride transfer that authors describe as an environmentally coupled tunneling model,21 addressed here as an example of Markus-like model.

d. Thermophillic alcohol dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearathermophilus (ht-ADH)

For this enzyme, studies indicate that the H-transfer is rate limiting across the temperature range studied. ht-ADH exhibits temperature-independent 1° KIEs within its physiological temperature range (30–65 °C) despite the fact that the overall rate is temperature-dependent.69 As noted above, temperature-independent KIEs with a temperature-dependent rate can be rationalized by the Marcus-like models described, where isotopically insensitive heavy atom motions compose the reaction coordinate, or as stated by Kiefer and Hynes “the solvent coordinate is the reaction coordinate”.70 Interestingly, below its physiological temperature range, ht-ADH shows temperature-dependent KIEs. This indicates a sort of phase transition at low temperatures, which alters the DAD sampling at the TRS (Figure 1C). This phenomenon was used to propose that certain protein motions bring the donor and acceptor close enough for hydrogen tunneling, but those motions are constrained below the physiological temperature range. Recent studies of mutants of this enzyme has further supported and extended this interpretation.71

e. Non-enzymatic Systems

Both temperature-dependent and independent KIEs have been measured for several non-enzymatic systems. Several C-H activations in intramolecular reactions that exhibit temperature-independent KIEs are especially of interest in connection with the enzymatic systems described above.72 While no rigorous explanation was proposed at the time, these results suggest that such systems could be used to better understand biological catalysis. More recent solid state NMR studies of intramolecular N-H→N reactions followed a more semiclassical path, where KIEs are temperature-dependent at high temperature and become temperature-independent at low temperature.73

4. 2D IR Spectroscopy of Proteins

The dynamics of several different proteins have been examined by 2D IR spectroscopy We summarize the results of a few such studies here to demonstrate the application of 2D IR to these systems and to identify common features and patterns that emerge in the dynamics of proteins. We have organized this summary by the type of chromophore that has been used to probe the protein spectral diffusion as the chromophore significantly impacts the range of experimentally accessible spectral diffusion time scales and the interpretation of the dynamics. The first several examples describe experiments that employ carbon monoxide as the probe. Carbon monoxide is a strong vibrational chromophore that binds tightly to the iron center of heme proteins. The CO stretching vibration absorbs at approximately 1950 cm−1, which is an accessible region of the infrared spectrum with little interference from protein or water vibrations. These characteristics make CO an excellent probe for a wide range of heme proteins.74–85 The last few examples describe experiments that use cyano86 or azido87–91 vibrations to probe the dynamics of several different enzymes. Cyano groups, which absorb near 2200 cm−1, hold great potential as probes of biomolecular dynamics,92 but they have seen limited applications because of their relatively weak transition dipole moment. Azido groups exhibit much stronger transition dipoles for the antisymmetric stretching vibration that absorbs at 2040 cm−1 in the azide anion and at somewhat higher frequencies for azido-derivatized compounds. Azides have seen more applications to protein dynamics because they can be incorporated into a wider range of systems than carbonyls, but suffer from relatively short population lifetimes that limit the time scales over which 2D IR can observe the dynamics.

a. Effect of Denaturation

As a protein denatures, the relatively narrow conformational distribution of the native protein gives way to complex conformational ensemble characteristic of a rugged energy landscape with many local minima. The dynamics of such an ensemble are sure to be different than those of the native complex. At the same time, however, the probe molecule is likely to become solvent exposed potentially resulting in spectral diffusion that is more characteristic of the solvent than of the ensemble of protein conformers. Kim et al. studied the effect of protein denaturation on the observed spectral diffusion dynamics for CO bound to the M61A mutant of cytochrome c from Hydrogenobacter thermophilus.78 Table 2 shows the FFCF parameters for CO bound to the protein both in normal aqueous buffer solution and at 5.1 M concentration of guanadinium HCl (GuHCl). In the native state, the protein exhibits dynamics on two time scales: an 8 ps component and a component that occurs on a time scale longer than the approximately 100 ps measurement time scale. Denaturing the protein with guandinium slightly increases the time scale of the fast component, but the more significant effect is that the amplitude of the frequency fluctuations at both time scales increases, with a dramatic increase in the amplitude of the static component. This static contribution to the FFCF suggests that there is a broad distribution of structures present even in the native protein, and that the heterogeneity of the ensemble increases significantly upon denaturation as would be expected. Although the dynamics of water are very fast, typically inducing nearly complete decay of the FFCF of an aqueous probe vibration in 1 ps or less,93–98 the CO group in the denatured protein does not exhibit dynamics that reflect interactions with bulk water. Instead, the large static contribution to the FFCF suggests that the denatured state at 5.1 M GuHCl is a heterogeneous ensemble of protein conformations that interconvert only on very long time scales and that interactions with these protein conformations give rise to the inhomogeneous distribution of CO transition frequencies. It is likely that the static contribution to the FFCF in these experiments is characteristic of the denatured ensemble and may, therefore, be different if the protein were to be denatured by a different mechanism. Chung et al. studied the dynamics of the same enzyme as a function of temperature both below and above the thermal denaturation temperature.76 Below the denaturation temperature, the FFCF parameters are nearly temperature independent. Above the unfolding transition, however, all of the FFCF parameters become temperature dependent. The amplitude of the fluctuations that relax on the picosecond time scale, Δ1, is larger for the unfolded state that for the native value by nearly a factor of two and continues to increases with temperature. The corresponding FFCF decay time, τ1, for the unfolded state is also larger by nearly a factor of two than for the folded state but decreases with temperature. Finally, the static contribution to the FFCF, ΔS, increases almost threefold relative to the folded protein and also decreases with temperature. These trends have a straightforward interpretation in terms of the protein dynamics. The decrease of ΔS with increasing temperature reflects the fact that as the temperature increases more of the protein conformational fluctuations occur within the ∼100 ps measurement time. This trend is consistent with the temperature dependent rise in Δ1. Thus, the unfolded state exhibits much more heterogeneity than the folded state regardless of whether the denaturation is thermal or chemical. In addition, as the temperature increases, the unfolded protein samples the available conformational space increasingly rapidly. Thus, these results suggest that the unfolded state represent a rugged conformational landscape with many local minima and that the increasing temperature increases the rate of crossing the kinetic barriers between these minima leading to the increased rate of sampling the conformational distribution.

Table 2.

FFCF parameters for native and denatured cytochrome c78

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) | τ1 (ps) | Δs (ps−1) | T1 (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cyt-c | .79 | 8 | .74 | 29 |

| cyt-c (5.1 M GuHCl) | .89 | 10 | 1.9 | 23 |

b. His-Tag Perturbations

Histidine tags (His6) are frequently used to simplify protein purification and are assumed to make only minor perturbations to the protein structure or function. Thielges et al. have studied the effect of a His tag on the spectral diffusion dynamics of CO bound to myoglobin (MbCO).75 Table 3 shows the FFCF parameters for MbCO and MbCO-His6. The presence of the His tag eliminates the contribution to the FFCF from the short time scale motions and slightly increases the static contribution to the FFCF. The effect of the His tag on the observed dynamics is surprising because there is no accompanying structural perturbation. In addition, the His tag is a relatively small collection of residues added to the end of the protein which is located far from the heme pocket. Nevertheless, it is clear from this study that the presence of the His tag does affect the protein dynamics at the active site. Although this effect is modest, the fact that it is measurably large is somewhat surprising and underscores the potential for distal perturbations to impact the dynamics at the functional binding site of a protein.

Table 3.

FFCF parameters for CO bound to myoglobin and myoglobin with a His tag.75

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) | τ1 (ps) | Δ2 (ps−1) | τ2 (ps) | Δs (ps−1) | T1 (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MbCO | .23 | 1.4 | .51 | 19 | .43 | 17 |

| MbCo-His6 | - | - | .51 | 21 | .57 | 20 |

c. Disulfide Bond Effects

Disulfide bonds contribute to protein stability and help to regulate protein activity. It seems likely that they should also have a significant impact on the conformational sampling of a protein. Ishikawa et al. reported on the effect of the disulfide bond on the protein dynamics in neuroglobin (Ngb), an oxygen-carrying member of the globin family of proteins that is expressed in the brain and other nerve tissues.80 Ngb is structurally similar to myoglobin except that it exhibits a disulfide bond. Like in myoglobin, when CO binds to the heme in Ngb, it does so in two distinct conformational substates referred to as N0 and N3, which give rise to distinct spectral features for the CO. Table 4 shows the FFCF parameters for these two substates in each of three different forms of Ngb: the wild-type protein (wt-Ngb), the protein with the disulfide bond eliminated by reduction (red-Ngb), and the protein with the disulfide bond eliminated by mutating one of the cysteine residues to serine (3cs-Ngb). These parameters show that the trends are the similar for both conformational substates at the short time scale. In each case, elimination of the disulfide bond either by reduction or by mutation accelerates the sampling at the few picosecond time scale and increases the amplitude of these frequency fluctuations, but this effect is less dramatic for the N0 state of the cysteine mutant protein. At longer time scales the two substates show distinct dynamics and trends with respect to disulfide bond cleavage. For N3, the static component gets somewhat smaller as the time scale for the intermediate time component gets somewhat larger. These two observations suggest that some of the motions that contribute to the static component in the wild type are accelerated when the disulfide bond is broken so that they now occur within the measurement window of the 2D IR experiment. For N0, however, the effects are subtler. The time scale for the spectral diffusion component of the FFCF gets faster upon reduction of the disulfide bond. Mutation of the cysteine accelerates the fast dynamics as well but not as much as in the case of reduction. In addition, disulfide bond cleavage slightly increases the size of the static contribution to the FFCF, suggesting that there is a larger range of accessible conformations for the N0 substate without the disulfide bond than there is in the wild-type enzyme. Perhaps the most critical feature of this study is that the disulfide bond is located nearly 20 Å from the binding pocket of the protein, yet there are perturbations to the dynamics of both substates of the protein which involve distinct conformations of the distal histidine. Thus, the changes in the dynamics associated with elimination of the disulfide bond must result from global changes in the protein dynamics rather than being more localized perturbations of the dynamics of the CO binding pocket.

Table 4.

FFCF parameters for CO bound to wild type neuroglobin (wt-Ngb), neuroglobin in which the disulfide bond has been reduced (red-Ngb), and neuroglobin in which one of the cysteines involved in the disulfide bond has been mutated to serine (3cs-Ngb). N3 and N0 refer to the two conformational substates of the protein.80

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) | τ1 (ps) | Δ2 (ps−1) | τ2 (ps) | Δs (ps−1) | T1 (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt-Ngb/N3 | .36 | 2.0 | .51 | 14 | .58 | 19 |

| red-Ngb/N3 | .57 | 1.3 | .62 | 22 | .55 | 16 |

| 3cs-Ngb/N3 | .38 | 0.7 | .57 | 23 | .43 | 16 |

| wt-Ngb/N0 | .34 | 11.5 | - | - | .66 | 18 |

| red-Ngb/N0 | .57 | 3.7 | - | - | .81 | 16 |

| 3cs-Ngb/N0 | .53 | 8.1 | - | - | 1.1 | 16 |

d. Horseradish Peroxidase

Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) is an iron-heme enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of a wide variety of organic substrates by hydrogen peroxide. Finkelstein et al. report a 2D IR study of HRP with CO bound to the heme in which the dynamics of the CO frequency fluctuations for ternary complexes with several different substrate analogs are compared to the dynamics of the binary complex without a substrate or substrate analog bound.83 Table 5 shows the FFCF parameters for the binary and ternary complexes of HRP. The binary complex has two substates (red and blue) that correspond to the two protonation states of the distal histidine in the active site. The red-shifted substate with the histidine protonated is the only state present with the substrates bound. In the binary complex this substate exhibits dynamics on two time scales: a fast component with a time constant of 1.5 ps and a slow component with a time constant of 21 ps. All of the ternary complexes exhibit qualitatively similar dynamics: the fast time constant is slower by a factor of two or three compared to the binary complex and the slow component becomes too slow to observe on the measurement time scale and so becomes a static component to the FFCF decay. In addition to the overall slowing of the dynamics, however, the most striking feature of the dynamics of the ternary complexes, however, is that the amplitudes of both components of the FFCF decay decrease relative to the binary complex, and, in the case of the slower component, which becomes static in the ternary complexes, the amplitude decreases by a factor of between two and three. This effect is even more significant given that the contribution to the FFCF for each component is proportional to the square of the amplitude meaning that this contribution to the FFCF decay is between 4 and 9 times smaller in the ternary complexes than in the binary complex. As a result, the infrared absorption lineshape for all of the ternary complexes is much narrower than that for the binary complex. These differences suggest that forming the ternary complex greatly diminishes the substantial dynamics of the distal histidine and arginine, which are expected to have the greatest influence on the CO frequency fluctuations. Although these dynamics are not fully arrested, the amplitude of the structure fluctuations is substantially reduced and the barriers to such motions become much larger such that the time scales for the remaining dynamics slow considerably. Thus the active site becomes structurally constrained in the ternary complex.

Table 5.

FFCF parameters for CO bound to horseradish peroxidase. The binary complex of HRP with CO has two substate denoted red and blue. The substrate-analog compounds identify the ternary complexes.

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) | τ1 (ps) | Δ2 (ps−1) | τ2 (ps) | Δs (ps−1) | T1 (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary blue | .60 | 15.0 | - | - | .45 | 12 |

| Binary red | .58 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 21 | - | 8 |

| 2-napthohydroxamic acid | .60 | 2.6 | - | - | .34 | - |

| Benzhydroxamic acid | .43 | 4.4 | - | - | .36 | - |

| Benzamide | .53 | 4.5 | - | - | .51 | - |

| Benzhydrazide | .49 | 2.6 | - | - | .51 | - |

| N-methylbenzamide | .32 | 5.4 | - | - | .38 | - |

e. Cytochrome P450

The cytochrome P450s are a class of enzymes that hydroxylate a variety of substrates. Thielges et al. report the dynamics of the camphor specific cytochrome P450 (cyt P450cam) from Pseudomonas putida using CO bound at the active site as a probe.74 Table 6 gives the FFCF parameters for the cyt P450cam complexes.

Table 6.

FFCF parameters for CO bound to cyt P450cam. The binary complex of HRP with CO has two substate denoted red and blue. The substrate-analog compounds identify the ternary complexes.

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) | τ1 (ps) | Δ2 (ps−1) | τ2 (ps) | Δs (ps−1) | T1 (ps) | KD (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary 1937 cm−1 | .62 | 17.0 | - | - | 1.0 | 18 | |

| Binary 1952 cm−1 | .36 | 9.8 | - | - | 1.2 | 21 | |

| Binary 1963 cm−1 | .32 | 11 | - | - | .55 | 24 | |

| Camphor | .53 | 6.8 | 1.0 | 370 | - | 19 | 0.8 |

| Camphane | .34 | 5.5 | .72 | 300 | - | 27 | 1.1 |

| Adamantane | .43 | 1.6 | .77 | 260 | - | 24 | 50 |

| Norcamphor | .34 | 5.8 | .60 | 110 | - | 27 | 345 |

| Norbornane | .45 | 2.2 | .89 | 230 | - | 23 | 47 |

The binary complex of the enzyme, with the CO but without a substrate molecule bound, exhibits three distinct features in the CO absorption spectrum reflecting three distinct conformational substates. 2D IR spectra show that these conformers exhibit distinct dynamics on the picosecond time scale and that substrate binding selectively stabilizes a single conformational substate that exhibits dynamics distinct from those of the substrate-free enzyme. Although all three conformational substates of the binary complex exhibit a single picosecond decay component and a static contribution to the FFCF, the FFCF decays for all of the ternary complexes are biexponential with a fast time scale component that is faster than the picosecond decay for any of the substates of the binary complex and a slow component that replaces the static component from the binary complex and relaxes on the time scale of hundreds of picoseconds. These results indicate that although substrate binding involves some degree of conformational selection, the dynamics of the substrate-bound conformer are significantly influenced by the presence of the substrate invoking features of an induced-fit binding mechanism. By studying complexes of the natural substrate, camphor, and a series of related substrates, the authors identify a correlation between the active site dynamics with each substrate and the binding affinity. Specifically, substrates with smaller Kd values show longer time constants for the slow component of the FFCF decay. The authors conclude that the conformational dynamics of the enzyme becomes constrained in the more tightly bound complexes because restricting the conformational fluctuations of the active site as the system approaches the transition state structure helps to ensure that the hydroxylation reaction occurs at the appropriate carbon. Thus, the specificity of the hydroxylation is related to the rigidity of the active site supporting the hypothesis that the protein dynamics play a functional role in controlling the outcome of the catalyzed reaction.

f. HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase

Reverse transcriptatses help to convert single-stranded RNA into double-stranded DNA and are required for the replication of viruses. As a result, HIV-I reverse transcriptase (HIV-I RT) inhibitors are of great interest in the treatment of HIV. Because of the potential for a flexible inhibitor to accommodate mutation-induced changes to the binding pocket, inhibitors with strategic flexibility have the potential to overcome the effects of drug-resistance mutations. Fang et al. report on the dynamics of HIV-1 RT with one such inhibitor TMC278.86 A unique feature of this study is that it employs intrinsic vibrations of the inhibitor itself to probe the protein dynamics. In this case, the molecule TMC278 incorporates both a cyanovinyl and a benzonitrile group each located on one arm of the molecule. These two cyano groups provide spectroscopic handles by which the dynamics of the protein can be observed using 2D IR. This experiment represents a significant challenge to the sensitivity of 2D IR, however, as the protein sample is soluble up to ∼1 mM concentration and the nitrile stretching vibration is much weaker than any other chromophores that have been used either before or since for 2D IR experiments on proteins. Nevertheless, the authors are able to measure 2D IR spectra of the complex of HIV-1 RT with TMC278 showing two distinct features corresponding to the two cyano groups of the inhibitor. Unfortunately, the transition moment of the benzonitrile group is small enough that it was not possible to determine the FFCF for this transition. Nevertheless, the authors do report the FFCF for the cyanovinyl group of the inhibitor, but because of the relatively short lifetime of the CN vibration, they can only measure 2D IR spectra for waiting times up to 5 ps leaving considerable uncertainty in the long time scale of the decay. The authors report this time scale to be 7.1 ps, and suggest that complete sampling of the nitrile frequency distribution could be complete on the tens of picoseconds time scale. Based on the structure of the binding pocket and the fact that the electrostatic interactions with the rest of the protein are likely to be screened very effectively by the aromatic residues lining the binding site for the cyanovinal group, the authors argue that the spectral diffusion dynamics are dominated by local fluctuations of the cyanovinyl arm with respect to the side chains composing the hydrophobic tunnel. The very local behavior of these dynamics is in contrast to what has been seen with CO in other proteins and reflects one of the impacts of the choice of chromophore on the observed dynamics.

g. Carbonic Anhydrase II

Carbonic anhydrases are zinc enzymes that catalyze the interconversion of bicarbonate and carbon dioxide. There are many isozymes of carbonic anhydrase and these are found throughout biology. The most common isozymes in mammals is carbonic anhydrase II (CA II), which has very high sequence homology across species. Lim et al. first reported the dynamics of azide anion bound to the active site zinc of bovine CA II.87 Subsequently, we studied the dynamics of both wild-type human CA II and two active-site mutants, T199A and L198F.91 Azide anion is a metal poison and binds to the active site zinc inhibiting the normal activity of the enzyme. Table 7 summarizes the FFCF results for both the bovine CA II (BCA II) and the human CA II (HCA II) as well as the mutants.

Table 7.

FFCF parameters for azide bound to the active site zinc bovine87 (BCA II) and human91 (HCA II) carbonic anhydrase II and the human CA II mutants T199A and L198F.

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) | τ1 (ps) | Δ2 (ps−1) | τ2 (ps) | Δs (ps−1) | T1 (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCA II | 1.6 | 0.2 | .95 | 17 | - | 2.8 |

| HCA II | 2.02 | .45 | - | - | .86 | - |

| T199A | 1.86 | .40 | - | - | .88 | - |

| L198F | 1.96 | .25 | 1.01 | 2.5 | - | - |

For BCA II, Lim et al. report a two-component FFCF decay with a subpicosecond fast contribution and a 17 ps slow contribution. For the wild type HCA II, we report a similar fast component, but, instead of a slow decay, we report a static contribution to the overall decay. Using the parameters from Lim et al. we get a nearly indistinguishable fit to our data and conclude that these two enzymes exhibit essentially the same dynamics and that the differences in the FFCF reflect differences in how the two groups choose to model the data. In their study of BCA II, Lim et al. suggest that Thr199, the residue closest to the azide in the active site, is likely to be important for modulating the transition frequency of the zinc-bound ligand. This conclusion seems reasonable as the oxygen atom of Thr199 is positioned very near the central nitrogen of the azide suggesting a strong electrostatic interaction. Based on our experiments on the T199A mutant, however, we can clearly conclude that this residue has almost no effect on the observed dynamics because the FFCF for the T199A mutant is essentially identical to that for the wild-type enzyme. In the L198F mutant, however, we see a significant change to the long-time dynamics. Specifically, the static component that is present in the wild-type enzyme gives way to a 2.5 ps decay. We propose that the phenylalanine ring itself does not directly interact with the azide causing this perturbation. Instead, we suggest that the Phe ring introduces steric hindrance in the active site that forces the azide anion to come closer to the amide proton at position 199with which it forms a hydrogen bond. This hydrogen bond makes the dominant contribution to the observed dynamics. In the wild-type enzyme the azide anion is free to explore the hydrophobic pocket of the active site and sample a wide range of hydrogen-bond distances. In the L198F mutant, however, the Phe ring fills the empty space in the active site significantly constraining the range of hydrogen-bond distances available to the azide anion. As a result, the distribution of H-bond lengths is sampled much more rapidly resulting in the 2.5 ps decay contribution to the FFCF.

Common themes from these previous studies of enzyme dynamics are the rigidification of the protein upon ligand binding (proportional to Kd) and the long range of these effects on the protein dynamics. These findings are in accordance with similar trends of rigidification of the protein upon ligand binding at nanosecond to microsecond (ns-µs) time scales measured via NMR relaxation studies of other proteins.40,99,100 While such effects are expected at longer time scales (as suggested by the “induced fit” model of substrate binding), it is less intuitive that such behavior should also be seen at the femtosecond to picosecond time scale.

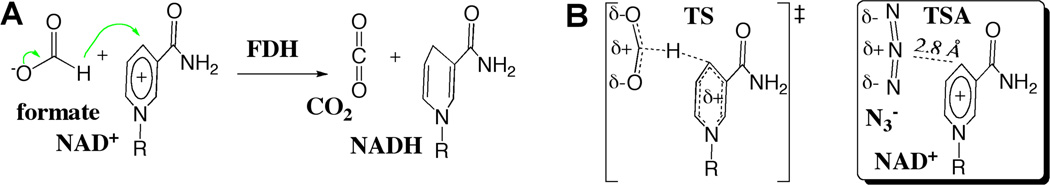

5. FDH – combining the kinetic and spectroscopic methods

Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) catalyzes the NAD+-dependent oxidation of formate to CO2 (Scheme 3). Azide (N3−), which is an excellent vibrational chromophore for IR spectroscopy, is a tight-binding inhibitor for FDH. Azide is a potent transition-state analog (TSA) of the catalyzed reaction. Thus FDH can serve to study the relationship between the H-transfer step and the TRS dynamics.

Scheme 3.

FDH Catalyzed Reaction. A. The reaction. B. A comparison of the TS and TSA complexes.

Here we will emphasize two aspects of the examination of FDH, kinetics as a measure of the nature of H-transfer, and 2DIR spectroscopy as a measure of active-site dynamics. Finding a correlation between results of these two experiments is the long term goal of the studies described here.

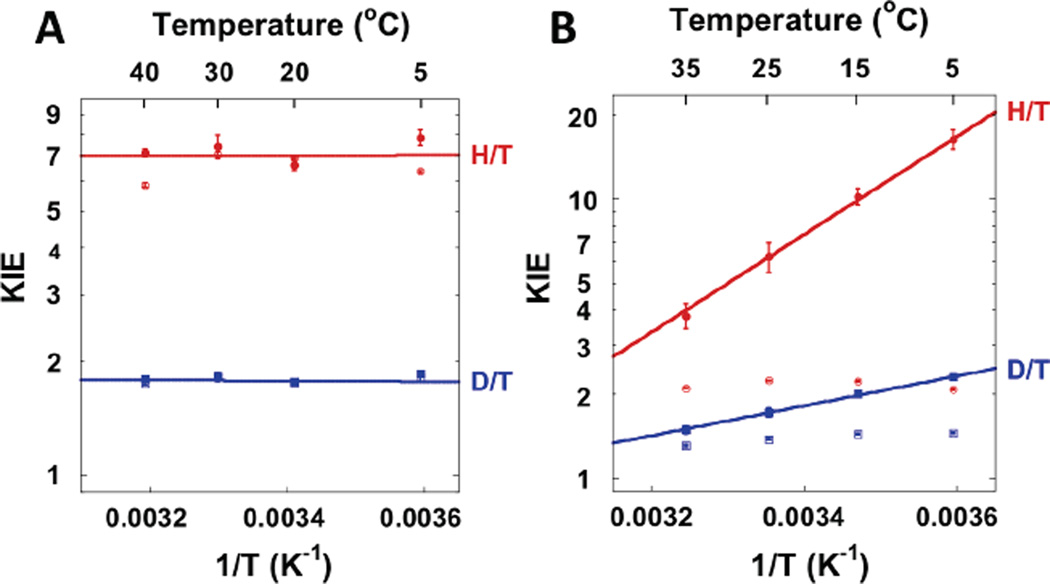

a. Kinetics and the Nature of H-transfer in FDH

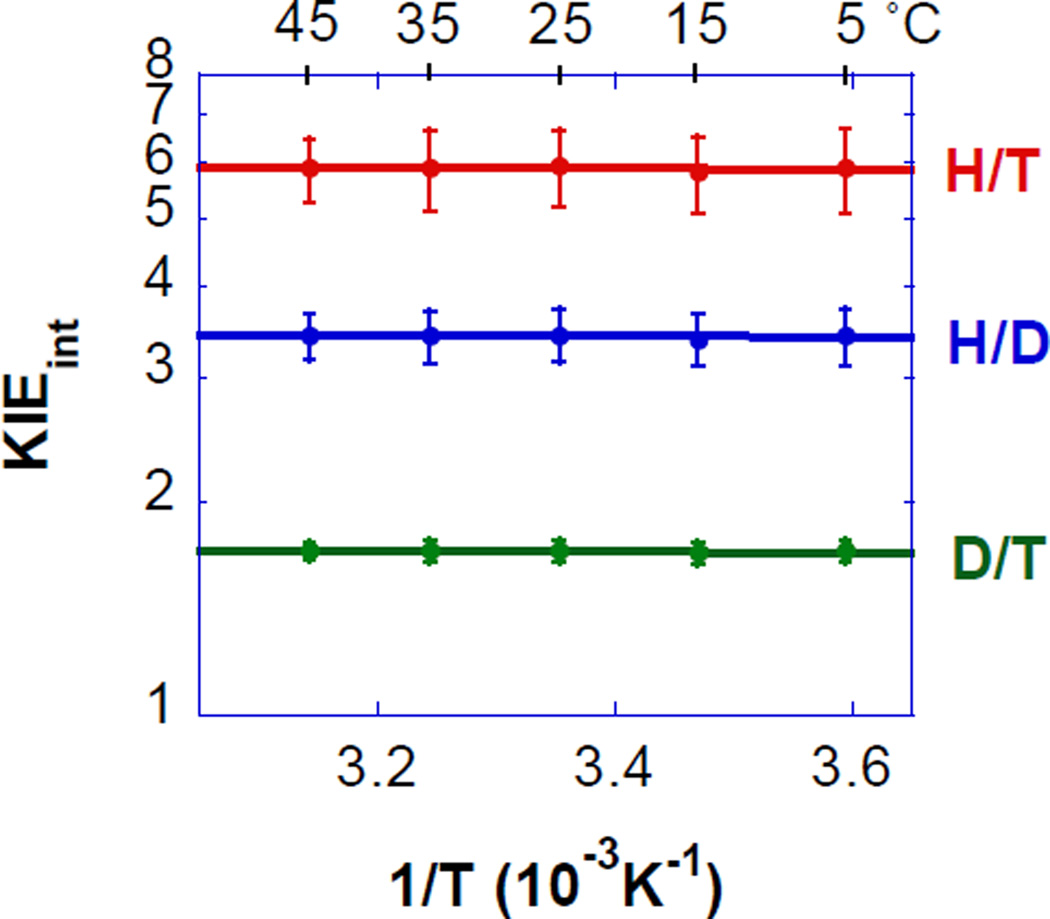

In the case of FDH from Candida boidinii we had to develop a new method to measure intrinsic KIEs as labeling of the substrate with both 14C and the isotope of interest (H or D) would have been affected by the 1° 14C KIE. Instead we used [Ad-14C]NAD+ and formic acid labeled with H or D and trace-labeling of T.101 This method proved instrumental in measuring competitive H/T and D/T 1° KIEs and the Northrop method was then used to assess the intrinsic KIEs. For the wild-type enzyme these KIEs were temperature independent (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

An Arrhenius plot of the intrinsic H/T (red), H/D (blue) and D/T (green) KIEs (log scale) vs. the reciprocal of the absolute temperature. The average KIEs are presented as points and the lines are an exponential fit of all the data points to the Arrhenius equation.

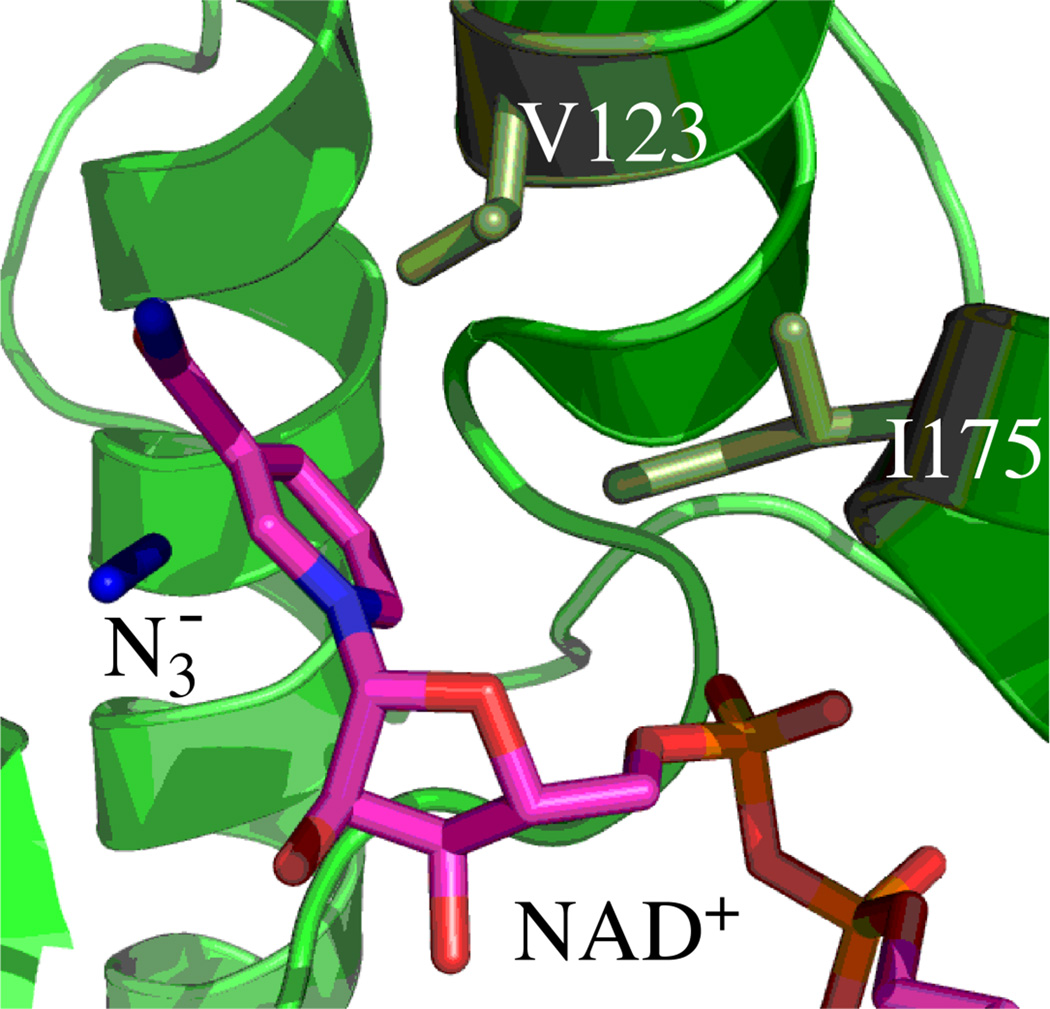

b. Dynamics of Transition-State-Analog Complexes of FDH

The ternary complex of FDH with NAD + and azide is unlike other protein complexes that have been studied previously in that the azide anion is a transition-state-analog inhibitor. Azide is isoelectronic with the carbon dioxide product of the reaction but is negatively charged like the formate reactant. It is symmetric and acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor for the highly conserved hydrogen-bond-donating residues in the active site that anchor and orient formate for the reaction. Azide binds tightly in the active site with a KD of 40 nM. Thus, azide is a good mimic of the TRS of the hydride transfer reaction. We have measured the protein dynamics in this complex to explore the potential for femtosecond to picosecond time scale motions to play a functional role in the enzyme-catalyzed hydride transfer.89

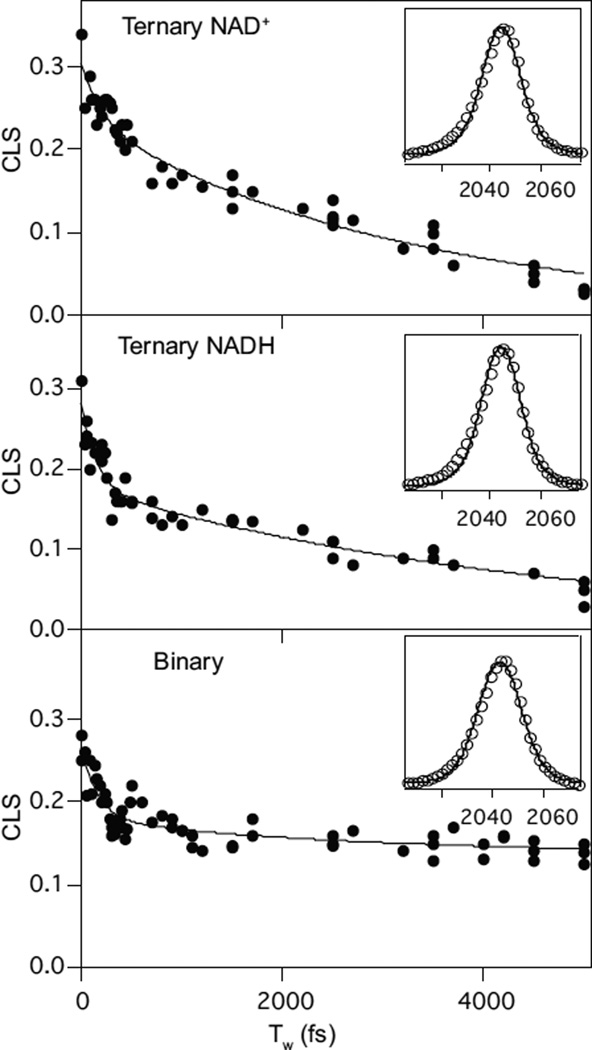

Figure 7 shows the CLS decays for the ternary and binary complexes of FDH with azide. The top panel shows the decay for the ternary complex with FDH, NAD+, and azide. The center panel shows the decay for the ternary complex with NADH, and the bottom panel shows the decay for the binary complex with just FDH and azide. Table 8 shows the FFCF parameters that result from fitting the decays and the infrared absorption spectra that are shown as insets to Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Decays of the CLS as a function of the waiting time, Tw, for the complexes of FDH with azide. The lines represent fits of Eq. 4 to the experimental data (markers). The time constants and relative amplitudes are used to fir the FTIR spectrum (inset) to get the final FFCF parameters, which are presented in Table 8. Reproduced with permission from ref 89.

Table 8.

FFCF parameters for azide in the ternary and binary complexes with FDH.89

| Protein | Δ1 (ps−1) |

τ1 (ps) |

Δ2 (ps−1) |

τ2 (ps) |

Δs (ps−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDH-N3-NAD+ | 0.9 | .21 | 1.4 | 3.2 | - |

| FDH-N3-NADH | 1.0 | .15 | 1.3 | 4.6 | - |

| FDH-N3 | 1.1 | .16 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

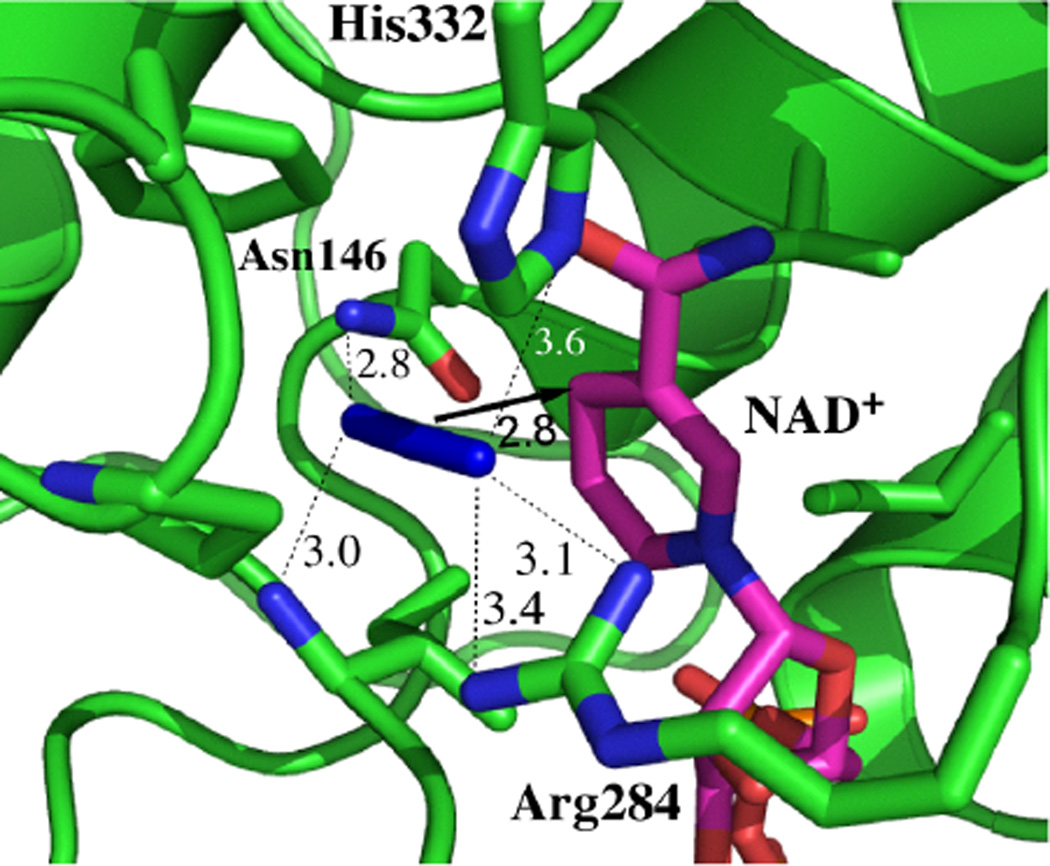

The first thing to note is that there is no static component to the decay for either of the ternary complexes. This behavior is in stark contrast to most other systems that have been studied previously. In the two other cases for which the protein dynamics are fully sampled on the time scale of a few picoseconds, in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and in the L198F mutant of human carbonic anhydrase II, the result is easily explained in terms of the structure because it can be argued that the dynamics of the probe vibration are dominated by local interactions and do not reflect the global protein dynamics. In other words, because of the nature of the local interactions, the probe is insensitive to the motions of the rest of the protein. That explanation is not reasonable for the ternary complexes of FDH. Figure 8 shows the active site structure of the ternary complex of FDH with azide and NAD+ from Pseudomonas sp.101,102 which has high sequence homology with the Candida boidinii enzyme used in our experiments. The critical features to note in this structure are the four hydrogen-bond-donating residues that anchor the azide in the active site: Asn-146, Arg-284, His-332, and the amide N-H of Ile-122. These residues are highly conserved across many species of FDH and are critical to the function of this enzyme because they bind and orient the substrate for reaction. In the context of our spectroscopic measurements, these residues are important because the hydrogen bonds that they donate to the azide anion are likely to be the dominant source of frequency fluctuations and, therefore, play a prominent role in determining the observed FFCF decay dynamics. On each side of the active site is a β-sheet–α-helix–β-sheet sandwich structural motif. Each of these residues resides at the end of one of the major secondary structural elements that comprise this motif. Asn-146 is at the end of an α-helix on one side of the azide. Arg-284 is at the end of a helix on the other side of the azide. His-332 is in the loop region between two strands of the β-sheet, and the amide group of Ile-122 is in a loop region between the end of a helix and the start of a β-sheet strand. Thus, if any of these large secondary structural elements were to undergo the kind of large amplitude motions that would be expected to the be responsible for the long time scale structural dynamics, then we would expect these motions to modulate the hydrogen-bond length between the appropriate residue and the azide in the active site thereby modulating the frequency of the anion. These motions would be expected, on our measurement time scale, to make a static contribution to the FFCF. In other words, based on the structure, we would expect the azide to be particularly sensitive to the slow motions of the overall protein structure because of the location of the hydrogen bond partners. Nevertheless, we do not observe such a static contribution to the FFCF in the ternary complexes. We conclude, therefore, that there are no dynamics of the active site residues of the protein on time scales longer than a few picoseconds in the transition-state-analog complexes of FDH.

Figure 8.

Active-site structure of FDH-azide-NAD+ complex (PDB# 2NAD102). Azide is in blue and NAD+ in magenta. Reproduced with permission form ref 89.