Abstract

There is a high rate of comorbidity between eating disorders and substance abuse, and specific evidence that weight-loss dieting can increase risk for binge pathology, rebound excessive weight gain, and initiation and relapse to drug abuse. The present overview discusses basic science findings indicating that chronic food restriction induces dopamine conservation, compensatory upregulation of D-1 dopamine receptor signaling, and synaptic incorporation of calcium-permeable glutamatergic AMPA receptors in nucleus accumbens. Evidence is presented which indicates that these neuroadaptations account for increased incentive effects of food, drugs, and associated environments during food restriction. In addition, these same neuroadaptations underlie upregulation of sucrose- and psychostimulant-induced trafficking of AMPA receptors to the nucleus accumbens postsynaptic density, which may be a mechanistic basis of enduring maladaptive behavior.

Introduction

An early and productive hypothesis guiding research into the neurobiological basis of drug abuse held that drugs with abuse liability target and appropriate the neural substrates that mediate appetitive motivation and reward. Capitalizing on existing knowledge of CNS mechanisms of appetitive behavior, and the functionally related phenomenon of electrical brain stimulation reward, drug abuse research advanced at a rapid pace, and has led to substantial understanding of the neurobiological bases of reward, addiction, withdrawal distress and relapse [1,2]. Consequently, in recent years there has been a role-reversal whereby research into the neurobiology of ingestive behavior, particularly when reward-driven, has been informed by discoveries in the drug abuse field. Though not without controversy, the current obesity epidemic has been attributed, in part, to “food addiction” or “eating addiction” [3–7]. An underlying premise, based on animal models, is that supranormally rewarding foods, especially when taken on an intermittent basis, may be similar to drugs of abuse in their ability to induce neuroplastic changes that mediate craving, compulsive pursuit, and overconsumption. Research of our laboratory summarized below, while not modeling or premised on an addiction, is proposed to offer mechanistic insight into adverse effects of food restriction as they relate to both reward-driven eating and drug abuse risk.

Among the research strategies used to explore shared mechanisms of ingestive behavior and drug abuse has been perturbation of the system that regulates one and investigation of consequences for the other. Chronic food restriction has been put to productive use in this regard and has the advantage of translational significance. There is abundant evidence of high comorbidity of disordered eating and substance abuse [8–10], and specific evidence that weight-loss dieting can increase drug abuse risk [11–13]. Further, a frequent byproduct of chronic drug use, as well as abstinence, is a change in caloric intake [14]. Consequently, this investigative approach has potential to illuminate underpinnings of some comorbidities as well as ways in which drug addiction-related changes in ingestive behavior may influence the course of that addiction.

With regard to excessive intake of highly palatable, energy dense food, and identification of factors contributing to obesity, understanding transient and enduring neuroadaptations to food restriction may provide useful insights. Severe dieting is a risk factor for binge pathology [15], and weight-loss dieting is receiving increasing attention as a practice that exacerbates future overeating and weight gain [16,17]. The remainder of this overview will therefore enumerate key neuroadaptations induced by chronic food restriction (FR), their involvement in altered behavioral responsiveness to unconditioned and conditioned reward stimuli, and potential for certain types of ingestive behavior occurring episodically during FR to increase risk for enduring maladaptive ingestive behavior. The food restriction protocol used in most studies discussed involves a decrease and clamping of body weight, in rats, at 80% of the pre-restriction value for periods ranging from four to six weeks.

Dopamine-Related Neuroadaptations Induced by Food Restriction

With a primary focus on the mesoaccumbens “reward pathway” it has been found that chronic FR decreases tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA and protein levels in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), decreases the amplitude of evoked EPSCs in presumed dopamine (DA) neurons of the VTA, decreases the evoked release of DA in nucleus accumbens (NAc), and decreases mRNA levels of neuropeptides associated with D-1 receptor-expressing medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in NAc, suggesting a sustained decrease in D-1 receptor stimulation [18,19]. These observations are in agreement with the in vivo microdialysis results of Pothos and coworkers who, using a FR protocol that produced body weight loss similar to ours, reported decreased extracellular [DA] in NAc under basal conditions as well as after a bout of food consumption [20]. Overall, these findings point to DA conservation when food is scarce. Nevertheless, there is evidence that when food or a proxy for food (i.e., a drug of abuse) is encountered, the net response of the system, including behavioral readout, is upregulated. For example, FR increases the rewarding and locomotor-activating effects of a wide range of abused drugs, whether administered systemically or directly into the NAc shell [18]. Further, if ad libitum (AL) fed subjects are conditioned to associate an environmental context with cocaine or morphine and are then switched to FR for several weeks before commencement of daily conditioned place preference (CPP) testing, the magnitude and persistence of CPP are markedly greater than in subjects that have remained AL throughout [21; morphine CPP results in preparation]. This effect does not extend to a LiCl conditioned place aversion [in preparation] and suggests that FR is specifically enhancing the incentive effects of a drug-paired environment, paralleling the enhancing effects on unconditioned drug reward.

There is support for the contention that these enhancing effects of FR result from stable neuroadaptations rather than degree of acute deprivation or meal-entrained levels of blood-borne metabolic hormones. When daily feeding is timed such that FR animals undergo behavioral testing either 1–4 or 18–20 hrs after the most recent meal, and testing at the two time points is accompanied by markedly different plasma levels of ghrelin, insulin, and corticosterone, the enhancing effects of FR on cocaine reward, amphetamine reward, and CPP persistence do not differ between groups [21]. Enhanced behavioral responsiveness appears to be due, at least in part, to upregulation of stimulus-induced D-1 DA receptor signaling in NAc [18].

Effects of Sucrose and Food Restriction on AMPA Receptor Phosphorylation and Trafficking

One downstream effect of D-1 receptor signaling is phosphorylation of the glutamatergic AMPA receptor GluA1 at Ser845. This event increases neuronal excitability by increasing channel open probability, stabilizing the receptor in the membrane, and trafficking GluA1-containg AMPA receptors (AMPARs) to the extrasynaptic membrane for synaptic insertion [22,23]. It is therefore significant that in NAc, FR rats display enhanced phosphorylation of GluA1 at Ser845 in response to brief intake of 10% sucrose, injection of D-1 agonist, injection of d-amphetamine, and exposure to an environment previously paired with cocaine [21,24,25]. Moreover, the magnitude of CPP in FR rats correlates with pSer845-GluA1 in the NAc core [21].

To examine effects of sucrose consumption on AMPAR trafficking in NAc, Tukey and coworkers [26] gave AL subjects 5-min access to 25% sucrose solution on each of seven consecutive days. Immediately and 24-h after the final bout of sucrose intake, quantitative electron microscopy revealed elevated intraspinous GluA1 in NAc MSNs, indicating that sucrose intake increases the intracellular pool adjacent to synaptic sites. Immediately following the final bout of sucrose intake there was also a transient increase in GluA1 within both the extrasynaptic membrane and postsynaptic density (PSD). In a second study, AL and FR rats consumed ~16 ml of 10% sucrose, during a 30-min access period, every other day for a total of ten sessions. Immediately after the final session, increased GluA1 abundance was again observed in the NAc PSD of AL rats. However, FR rats displayed a significantly greater increase in GluA1 as well as an increase in GluA2 [27]. Similar to sucrose, acute administration of d-amphetamine, in otherwise naïve rats, increased abundance of GluA1 and GluA2 in the NAc PSD with a greater effect in FR than AL rats [25].

AMPARs mediate fast excitatory synaptic transmission, and changes in AMPAR abundance in the synaptic membrane mediate synaptic tuning. Activity-dependent regulation of postsynaptic AMPAR mobility can alter synaptic transmission within seconds [28], while trafficking of cytoplasmic AMPARs to the membrane mediates experience-dependent plasticity [29]. AMPARs are co-expressed with DA receptors in NAc neurons [30], and most are either GluA1/GluA2 or GluA2/GluA3 heteromers [31]. GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors make up only 5–10% of the total but, when present, are of note because they increase Ca2+ conductance and enable Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling which can traffic additional GluA1-containing AMPARs to the synaptic membrane [32] and mediate synaptic strengthening via long term potentiation [33,34].

The findings of increased Ser845 phosphorylation and trafficking of GluA1-containing AMPARs to the PSD in response to sucrose, psychostimulants, and a psychostimulant-paired context in FR rats suggests a role in the associated enhancement of stimulus reward and place preference. Accordingly, the upregulation of AMPAR phosphorylation and trafficking would be expected to increase the pressure to approach and consume palatable food, particularly when FR occurs in a context containing an abundance of palatable foods and associated cues (e.g., Western societies). This hypothesis becomes especially plausible if, as suggested by the pharmacology and biochemistry, increased AMPAR abundance and function are preferentially associated with D-1 receptor-expressing MSNs in NAc, which are largely segregated from D-2 receptor-expressing MSNs [35]. Studies employing optogenetic and chemogenetic methods have demonstrated that excitation of D-1-expressing MSNs is reinforcing, increases behavioral activation, and enhances stimulus reward, while excitation of D-2-expressing MSNs exerts opposite effects [36–39].

AMPA Receptors, Synaptic Strengthening, and Enduring Effects of Sucrose Consumption During Food Restriction

Electrophysiological studies have demonstrated that reward-learning is accompanied by the formation of distinct NAc neuronal ensembles that encode the corresponding reward-directed behavior [40]. In the specific case of cocaine self-administration, the proportion of NAc neurons that code for cocaine-seeking increases during abstinence, corresponding to the incubation period for cocaine craving and relapse risk, while the proportion of neurons coding for natural reward diminishes [41]. This “rewiring” of NAc parallels the prepotency of drug-seeking and concomitant devaluation of natural rewards. Based on the role of activity-dependent AMPAR trafficking in synaptic strengthening, and the upregulation of stimulus-induced trafficking in FR subjects, it is hypothesized that increased synaptic abundance of AMPARs may mediate an enduring synaptic strengthening that increases corresponding reward-directed behavior. This could be a mechanistic basis for development of binge eating and excessive intake of palatable food as a long term consequence of episodic “loss of control” [42] during periods of severe dieting. Imagining a parallel to the cocaine studies cited above [41], subjects acquiring sucrose self-administration during FR might ultimately display a greater proportion of NAc neurons dedicated to sucrose- relative to chow- or water-seeking than subjects acquiring the same behavior in the AL fed state.

An initial experiment has been conducted to examine the interaction between FR and sucrose consumption as it relates to synaptic abundance of AMPARs and sucrose consumption following the return of FR subjects to AL feeding [43]. Three times per week, for a total of three weeks, AL and FR rats had 1-h access to a 10% sucrose solution or tap water with maximum sucrose consumption limited to achieve similar intake in the two diet groups. FR subjects were then returned to AL feeding, and experimental testing was initiated only after daily chow intake and rate of body weight gain no longer differed from that of subjects which had been AL throughout. Testing consisted either of measuring 1-h intake of 10% sucrose three times per week for four weeks, a protocol developed by Corwin and coworkers to induce binge-like intake [44], or obtaining NAc for biochemical assay following 15-min access to sucrose or water, or removal of subjects from the home cage without fluid access. Results indicated that subjects with a history of sucrose intake during FR consumed more sucrose in the four week protocol than the two AL groups and the group that had access to water during FR. The only group that displayed escalation over weeks was the group with a history of FR without sucrose access. Thus, by the fourth week of testing (i.e., seven weeks after restoration of AL feeding), sucrose intake of this group was essentially the same as that of the group with a history of sucrose intake during FR, and intake of both of these former FR groups was significantly greater than groups that had been AL throughout.

In addition, rats with a history of sucrose intake during FR displayed increased abundance of GluA1, GluA2 and GluA3 in the NAc PSD relative to rats that had been AL throughout, including those with a similar history of sucrose intake. A terminal bout of sucrose intake produced a further increase in pSer845-GluA1 and GluA2 in subjects with a history of sucrose intake during FR but not in subjects with the same history of sucrose intake during AL. Rats with a history of FR, with no history of sucrose intake and no sucrose prior to sacrifice, showed higher levels of GluA1 in the NAc PSD relative to all AL groups. These results suggest that a history of FR, alone, produces a lasting increase in synaptic incorporation of GluA1. Further, if historical FR is accompanied by episodic consumption of sucrose, there is an enduring increase in synaptic incorporation of GluA2 and GluA3. Interestingly, there is evidence that activity-dependent synaptic incorporation of GluA1, as was seen immediately after sucrose consumption [26], is transient and replaced by constitutively cycled GluA2/GluA3 AMPARs which preserve synaptic strength [45]. From these separate biochemical and behavioral observations, it would be predicted that animals in the behavioral component that had a history of FR without sucrose would have begun the subsequent four week sucrose protocol with increased GluA1 in the PSD, but by the time their sucrose intake rose to levels that surpassed both AL groups in week four, would display increased GluA2 and GluA3. Future tests of this prediction may help illuminate the relationship between FR-induced trafficking of GluA1, sucrose-induced trafficking of GluA1 and GluA2, and constitutive cycling of GluA2/GluA3, and whether any or all of these events are involved in increased sucrose consumption.

The results just summarized are consistent with the hypothesis that episodic sucrose intake during FR induces synaptic strengthening that persists following the return to AL feeding and is associated with increased sucrose consumption. Further, they suggest that a history of FR, alone, produces an enduring change in synaptic AMPAR abundance and vulnerability to escalation of sucrose intake over weeks. Although a causal relation between sucrose-induced AMPAR trafficking and consumption remains to be tested, the work with drugs of abuse, to be discussed below, indicates AMPAR involvement in the enhanced rewarding effects of unconditioned and conditioned stimuli in FR rats.

Food Restriction Induces Synaptic Incorporation of Calcium-Permeable AMPA Receptors

An interesting observation in the experiments described above is that FR subjects in control groups (i.e., drinking water instead of sucrose, injected with saline rather than psychostimulant) displayed elevated levels of GluA1, but not GluA2, in the PSD when compared to AL controls. These findings suggest that FR, itself, may induce synaptic incorporation of calcium-permeable AMPARs (CP-AMPARs). To explicitly test this hypothesis, a new experiment was conducted in which AL and FR subjects were simply maintained in home cages [in preparation]. In the NAc PSD, FR subjects displayed elevated levels of pSer845-GluA1 and GluA1, but not GluA2 or GluA3, relative to AL subjects. In addition, FR subjects displayed decreased whole cell levels of calcineurin, the phosphatase that dephosphorylates pSer845-GluA1 and enables GluA1 endocytosis. Together, these findings suggest that FR decreases calcineurin levels, which increases the stability of pSer845-GluA1, which facilitates the trafficking and maintenance of GluA1 in the postsynaptic density. This set of events is similar to those occurring in homeostatic synaptic scaling, where CP-AMPARs are inserted into the synaptic membrane following prolonged neuronal deprivation of excitatory input and decreased intracellular Ca2+ signaling [46,47]. A homeostatic incorporation of CP-AMPARs in NAc of FR rats could account, at least in part, for increased D-1 receptor dependent neuronal excitation and downstream behavioral effects, as well as the increased stimulus-induced trafficking of additional GluA1-containing AMPARs (GluA1 or GluA1/GluA2) to the postsynapse [32–34].

Confirming the inference drawn from biochemical findings, it was demonstrated that spontaneous EPSCs in NAc shell MSNs are of higher amplitude and frequency in FR relative to AL subjects; this is a hallmark indicator of synaptic insertion of CP-AMPARs. In addition, evoked EPSCs displayed a decrease in amplitude after bath application of a selective antagonist of CP-AMPARs, Naspm, but only in brain slices obtained from FR rats [in preparation]. In order to test the contribution of these receptors to behavior, Naspm was microinjected into NAc shell and shown to selectively reverse the enhancing effect of FR on rewarding effects of a D-1 agonist and d-amphetamine [24,25]. When microinjected into NAc core, Naspm blocked the robust and persistent expression of cocaine CPP in FR animals [48]. Overall, these results indicate that FR-induced synaptic incorporation of CP-AMPARs plays a fundamental role in the enhancement of behavioral responsiveness to psychostimulant drugs, associated environments, and specifically D-1 receptor stimulation. It seems reasonable to expect that the natural target of these neuroadaptations is food and associated cues/contexts, serving to facilitate acquisition and consumption, and strengthen behavior that has been successful in mitigating energy deficit.

Whether chronic DA conservation is sufficient to induce homeostatic synaptic incorporation of CP-AMPARs is not known. However, in two extreme cases of decreased DA utilization, i.e., a genetic mouse model of Parkinson’s Disease and 6-OHDA-induced DA denervation of the subthalamic nucleus, increased striatal levels of GluA1 and pSer845-GluA1, [49] and upregulation of functional postsynaptic AMPARs [50], respectively, were observed.

To summarize, two functions are being proposed for NAc AMPARs in FR subjects. First, increased synaptic incorporation of CP-AMPARs, induced by FR, is proposed to enhance DA-coded stimulus reward magnitude. Second, intracellular Ca2+ signaling via these receptors, in conjunction with increased signaling downstream of the D-1 receptor, are proposed to increase stimulus-induced synaptic plasticity, involving insertion of GluA1-containing AMPARs and eventual replacement by GluA2/GluA3 AMPARs. The hypothesized consequence is a more deeply ingrained form of reward-directed behavior than would have resulted from exposure to the same reward under free-feeding conditions.

Nucleus Accumbens Neuronal Excitation and Inhibition in the Control of Food Acquisition and Consumption

Although there are many distinct components of reward-related behavior encoded by NAc neurons [51], food consumption has been associated with NAc neuronal inhibition rather than excitation. Microinjection of the nonspecific AMPAR antagonist, DNQX, or the GABA receptor agonist, muscimol, in NAc shell induced vigorous feeding behavior, shown to be mediated by GABA release in lateral hypothalamus [52]. Electrophysiological studies confirmed the association between NAc neuronal inhibition and consumption [53]. However, it is also the case that NAc shell microinjections of muscimol had no effect, or actually decreased, progressive ratio responding for sucrose [52], suggesting an important difference between NAc neuronal mechanisms that enable feeding and those that mediate incentive motivation. Indeed, it was recently shown that the initiation and vigor of approach triggered by reward-predictive cues correlate with NAc neuronal firing rate [54]. Further, there appears to be more nuance to the association between NAc neuronal inhibition and feeding than was apparent in earlier studies. An analysis of NAc shell neuron firing in association with sucrose licking revealed one population of cells that displayed excitations and another that displayed inhibitions [55]. In response to these findings, the GENSAT image database of NAc shell D-1- and D-2-expressing MSNs from BAC transgenic mice was examined and it was found that D-2-, but not D-1-expressing, neurons project directly to lateral hypothalamus [56]. Based on the optogenetic stimulation studies, which have attributed opponent behavioral functions to these two subpopulations of NAc neurons, it was proposed that inhibition of D-2-expressing MSNS enables feeding via their lateral hypothalamic projections, while excitation of D-1-expressing MSNs sustains feeding via projections to ventral pallidum and/or their unique innervation of VTA [57]. Consistent with the idea that increased synaptic incorporation of AMPARs in D-1-expressing MSNs will promote ingestive behavior, a recent study of restraint stress-induced anorexia and sucrose indifference linked these impairments to decreased excitatory synaptic strength on D-1-expressing MSNs, resulting from internalization of AMPARs [58]. A positive role of NAc shell AMPARs, and a tempering of conclusions drawn from DNQX microinjection, are further indicated by the finding that feeding can be stimulated by NAc shell microinjection of AMPA [59]).

Conclusions

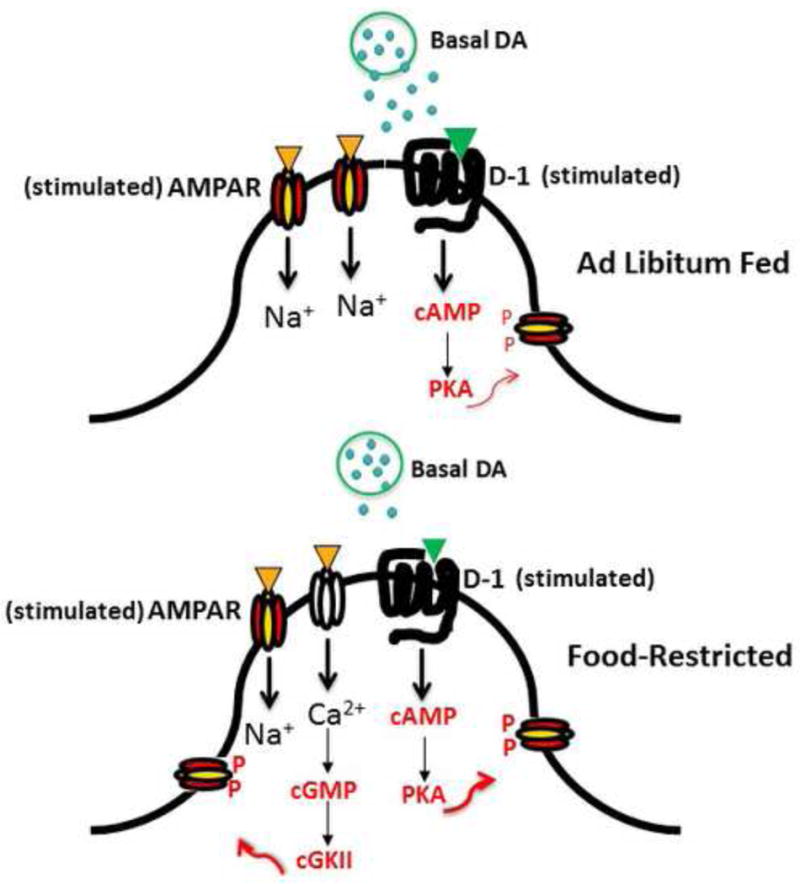

In conclusion, the scheme being proposed suggests, first, that homeostatic synaptic incorporation of CP-AMPARs in NAc contributes to the pressure to “break diet”. Second, with regard to the long term, it is suggested that enduring consumption of highly palatable food is particularly likely to become ingrained if prior intermittent consumption occurs during a period of food restriction, when mechanisms of synaptic plasticity in NAc are upregulated. While some details of this scheme (Fig 1) remain speculative, it includes (1) DA conservation which leads, in whole or part, to upregulation of D-1 receptor signaling and homeostatic trafficking of CP-AMPARs to the PSD of D-1-expressing neurons, (2) D-1- and CP-AMPAR-enabled increase in stimulus-induced trafficking of AMPARs to the PSD, (3) a resultant synaptic strengthening that persists beyond the return to AL feeding, and (4) an ascendency of reward-driven feeding in the hierarchy of goal-directed behaviors encoded by NAc neuronal ensembles.

Figure 1.

Nucleus Accumbens Medium Spiny Neuron postsynapse depicting elements of a mechanistic scheme for increased incentive effects of palatable foods and cues. Relative to the ad libitum fed state (above) food restriction (below) is associated with a decrease in basal and stimulated dopamine release which leads to compensatory upregulation of stimulus-induced signaling downstream of the D1 receptor. This, and decreased levels of the phosphatase, calcineurin, increase phosphorylation of GluA1 at Ser845. In addition, food restriction-induced insertion of GluA2-lacking Ca2+-permeable AMPARs increases excitatory synaptic strength and enables Ca2+-dependent signaling, a second pathway to Ser845 phosphorylation, and trafficking of GluA1-containing AMPARs to the extrasynaptic membrane, increasing the pool positioned for synaptic insertion.

Highlights.

Food restriction induces synaptic incorporation of AMPA receptors in accumbens

Food restriction increases stimulus-induced phosphorylation of AMPA receptors

AMPA receptors mediate increased reward of drugs and cues during food restriction

Upregulated AMPA receptor trafficking may underlie dieting as risk for binge eating

Acknowledgments

Research from the author’s laboratory and the writing of this article were supported by DA003956, DA036784, and DA033811 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and grants from the Klarman Family Foundation and NARSAD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The author declares no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Feltenstein MW, See RE. Systems level neuroplasticity in drug addiction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a011916. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koob GF1, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:20–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corwin RL, Grigson PS. Symposium overview–Food addiction: fact or fiction? J Nutr. 2009;139:617–619. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny PJ. Common cellular and molecular mechanisms in obesity and drug addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:638–651. doi: 10.1038/nrn3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gearhardt AN, Grilo CM, DiLeone RJ, Brownell KD, Potenza MN. Can food be addictive? Public health and policy implications. Addiction. 2011;106:1208–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hebebrand J, Albayrak O, Adan R, Antel J, Dieguez C, de Jong J, Leng G, Menzies J, Mercer JG, Murphy M, van der Plasse G, Dickson SL. “Eating addiction”, rather than “food addiction”, better captures addictive-like eating behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;47:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonas JM, Gold MS, Sweeney D, Pottash AL. Eating disorders and cocaine abuse: a survey of 259 cocaine abusers. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pisetsky EM, Chao YM, Dierker LC, May AM, Striegel-Moore RH. Disordered eating and substance use in high-school students: results from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:464–470. doi: 10.1002/eat.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merikangas KR, McClair VL. Epidemiology of substance use disorders. Hum Genet. 2012;131:779–789. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krahn D, Kurth C, Demitrack M, Drewnowski A. The relationship of dieting severity and bulimic behaviors to alcohol and other drug use in young women. J Subst Abuse. 1992;4:341–353. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(92)90041-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane C, Malcolm R, Brewerton T. The role of weight control as a motivation for cocaine abuse. Addict Behav. 1998;23:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo D-C, Jiang N. Associations between smoking and severe dieting among adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38:1364–1373. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orsini CA, Ginton G, Shimp KG, Avena NM, Gold MS, Setlow B. Food consumption and weight gain after cessation of chronic amphetamine administration. Appetite. 2014;78:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stice E, Davis K, Miller NP, Marti NC. Fasting increases risk for onset of binge eating and bulimic pathology: A 5-year prospective study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:941–946. doi: 10.1037/a0013644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann T, Tomiyama J, Westling E, Lew A-M, Samuels B, Chatman J. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. Amer Psychol. 2007;62:220–233. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pietilainen KH, Saarni SE, Kaprio J, Rissanen A. Does dieting make you fat? A twin study. Int J Obes. 2012;36:456–464. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr KD. Food scarcity, neuroadaptations, and the pathogenic potential of dieting in an unnatural ecology: binge eating and drug abuse. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stouffer M, Woods C, Patel J, Lee C, Witkovsky P, Bao L, Machold R, Jones K, Cabeza de Vaca S, Reith M, Carr KD, Rice M. Insulin enhances striatal dopamine release by activating cholinergic interneurons and thereby signals reward. Nature Commun. 2015;6:8543. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pothos EN, Creese I, Hoebel BG. Restricted eating with weight loss selectively decreases extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and alters dopamine response to amphetamine, morphine, and food intake. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6640–6650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06640.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng D, Liu S, Cabeza de Vaca S, Carr KD. Effects of time of feeding on psychostimulant reward, conditioned place preference, metabolic hormone levels, and nucleus accumbens biochemical measures in food-restricted rats. Psychopharmacol. 2013;227:307–320. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-2981-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry MR, Ziff EB. Receptor trafficking and the plasticity of excitatory synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He K, Song L, Cummings LW, Goldman J, Huganir RL, Lee HK. Stabilization of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors at perisynaptic sites by GluR1-S845 phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:20033–20038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910338106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr KD, Chau LS, Cabeza de Vaca, Gustafson K, Stouffer M, Tukey DS, Restituito S, Ziff EB. AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 downstream of D-1 dopamine receptor stimulation in nucleus accumbens shell mediates increased drug reward magnitude in food-restricted rats. Neurosci. 2010;165:1074–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng X-X, Cabeza de Vaca S, Ziff E, Carr KD. Involvement of nucleus accumbens AMPA receptor trafficking in augmentation of d-amphetamine reward in food-restricted rats. Psychopharmacol. 2014;231:3055–3063. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26*.Tukey D, Ferreira J, Antoine S, D’Amour J, Ninan I, Cabeza de Vaca S, Incontro S, Horwitz J, Hartner D, Guarini C, Khatri L, Goffer Y, Xu D, Titcombe R, Khatri M, Marzan D, Mahajan S, Wang J, Froemke R, Carr KD, Aoki C, Ziff E. Sucrose ingestion induces rapid AMPA receptor trafficking. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6123–6132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4806-12.2013. Using biochemistry, electron microscopy, and electrophysiology, this study demonstrated in rats that six brief episodes of sucrose consumption, on separate days, increased the intraspinous pool of GluA1 AMPA receptors in nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons, and the final episode produced a rapid but transient increase in GluA1 in the postsynaptic density. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng X-X, Ziff EB, Carr KD. Effects of food restriction and sucrose intake on synaptic delivery of AMPA receptors in nucleus accumbens. Synapse. 2011;65:1024–1031. doi: 10.1002/syn.20931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choquet D. Fast AMPAR trafficking for a high-frequency synaptic transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:250–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessels HW, Malinow R. Synaptic AMPA receptor plasticity and behavior. Neuron. 2009;61:340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glass MJ, Lane DA, Colago EEO, Chan J, Schlussman SD, Zhou Y, Kreek MJ, Pickel VM. Chronic administration of morphine is associated with a decrease in surface AMPA GluR1 receptor subunit in dopamine D1 receptor expressing neurons in the shell and non-D1 receptor expressing neurons in the core of the rat nucleus accumbens. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reimers JM, Milovanovic M, Wolf ME. Quantitative analysis of AMPA receptor subunit composition in addiction-related brain regions. Brain Res. 2011;1367:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tukey DS, Ziff EB. Ca2+-permeable AMPA (α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic Acid) receptors and dopamine D1 receptors regulate GluA1 trafficking in striatal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35297–35306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.516690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asrar S, Zhou Z, Ren W, Jia Z. Ca(2+) permeable AMPA receptor induced long-term potentiation requires PI3/MAP kinases but not Ca/CaM-dependent kinase II. PLoSOne. 2009;4:e4339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiltgen BJ, Royle GA, Gray EE, Abdipranoto A, Thangthaeng N, Jacobs N, Saab F, Tonegawa S, Heinemann SF, O’Dell TJ, Fanselow MS, Vissel B. A role for calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity and learning. PLoSOne. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Moine C, Bloch B. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor gene expression in the rat striatum: Sensitive cRNA probes demonstrate prominent segregation of D1 and D2 mRNAS in distinct neuronal populations of the dorsal and ventral striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355:418–426. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Lobo MK, Covington HE, 3rd, Chaudhury D, Friedman AK, Sun H, Damez-Werno D, Dietz DM, Zaman S, Koo JW, Kennedy PJ, Mouzon E, Mogri M, Neve RL, Deisseroth K, Han MH, Nestler EJ. Cell type specific loss of BDNF signaling mimics optogenetic control of cocaine reward. Science. 2010;330:385–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1188472. Using D1-Cre and D2-Cre mice expressing channelrhodopsin in nucleus accumbens, this study demonstrated that selective optical stimulation of D-1 receptor-expressing medium spiny neurons enhances cocaine reward and induces locomotor activation in cocaine-sensitized mice, while stimulation of D-2 receptor-expressing neurons inhibits cocaine reward and has no effect on locomotion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferguson SM, Eskenazi D, Ishikawa M, Wanat MJ, Phillips PE, Dong Y, Roth BL, Neumaier JF. Transient neuronal inhibition reveals opposing roles of indirect and direct pathways in sensitization. Nature Neurosci. 2011;14:22–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kravitz AV, Tye LD, Kreitzer AC. Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement. Nature Neurosci. 2012;15:816–818. doi: 10.1038/nn.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yawata S, Yamaguchi T, Danjo T, Hikida T, Nakanishi S. Pathway-specific control of reward learning and its flexibility via selective dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12764–12769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210797109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pennartz CM, Groenewegen HJ, Lopes da Silva FH. The nucleus accumbens as a complex of functionally distinct neuronal ensembles: an integration of behavioural, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:719–761. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron CM, Carelli RM. Cocaine abstinence alters nucleus accumbens firing dynamics during goal-directed behaviors for cocaine and sucrose. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:940–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogers PJ, Hill AJ. Breakdown of dietary restraint following mere exposure to food stimuli: interrelationships between restraint, hunger, salivation, and food intake. Addict Behav. 1989;14:387–397. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Peng X-X, Lister A, Rabinowitsch A, Kolaric R, Cabeza de Vaca S, Ziff EB, Carr KD. Episodic sucrose intake during food restriction increases synaptic abundance of AMPA receptors in nucleus accumbens and augments intake of sucrose following restoration of ad libitum feeding. Neurosci. 2015;295:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.03.025. A key finding of this study is that when rats with episodic brief access to sucrose during chronic food restriction have returned to free-feeding and show normalization of 24 h chow intake, rate of body weight gain, and plasma leptin levels, they nevertheless display increased AMPA receptor GluA1, GluA2 and GluA3 in nucleus accumbens postsynaptic density, and consume more sucrose, relative to ad libitum fed rats. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corwin RLW, Wojnicki FHE. Binge-type eating induced by limited access to optional foods. In: Avena NM, editor. Animal Models of Eating Disorders. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi S, Hayashi Y, Esteban JA, Malinow R. Subunit-specific rules governing AMPA receptor trafficking to synapses in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Cell. 2001;105:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiagarajan TC, Lindskog M, Malgaroli A, Tsien RW. LTP and adaptation to inactivity: overlapping mechanisms and implications for metaplasticity. Neuropharmacol. 2007;52:156–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Kim S, Ziff EB. Calcineurin mediates synaptic scaling via synaptic trafficking of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001900. This study, in cultured neurons, identifies a mechanistic link between chronic suppression of neuronal excitation, the associated decrease in somatic Ca2+ signaling, and synaptic incorporation of Ca2+ permeable AMPA receptors. Key is the decrease in calcineurin activity and the resultant stabilization of GluA1 phosphorylation at Ser845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng D, Jurkowski Z, Cabeza de Vaca S, Carr KD. Nucleus accumbens AMPA receptor involvement in cocaine conditioned place preference under different dietary conditions in rats. Psychopharmacol. 2015;232:2313–2322. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3863-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koutsokera M, Kafkalias P, Giompres P, Kouvelas ED, Mitsacos A. Expression and phosphorylation of glutamate receptor subunits and CaMKII in a mouse model of Parkinsonism. Brain Res. 2014;1549:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen KZ, Johnson SW. Dopamine depletion alters responses to glutamate and GABA in the rat subthalamic nucleus. Neuroreport. 2005;16:171–174. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502080-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saddoris MP, Sugam JA, Cacciapaglia F, Carelli RM. Rapid dopamine dynamics in the accumbens core and shell: Learning and action. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2014;5:273–288. doi: 10.2741/e615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE, Will MJ. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation:integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:773–795. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Dissecting motivational circuitry to understand substance abuse. Neuropharmacol. 2009;56(Suppl 1):149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGinty VB, Lardeux S, Taha SA, Kim JJ, Nicola SM. Invigoration of reward seeking by cue and proximity encoding in the nucleus accumbens. Neuron. 2013;78:910–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55*.Krause M, German PW, Taha SA, Fields HL. A pause in nucleus accumbens neuron firing is required to initiate and maintain feeding. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4746–4756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-10.2010. Using single unit recording in behaving rats this study shows that one subset of NAc neurons pause during sucrose licking, and their decreased firing is correlated with the motor pattern of licking. A second subset of NAc neurons display increased firing in association with sucrose licking. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56*.Frazier CR, Mrejeru A. Predicted effects of a pause in D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons during feeding. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9964–9966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2745-10.2010. These authors considered findings of NAc neurons that pause or fire in relation to sucrose licking [54], known neuroregulatory effects of MSN efferent projections, and outputs of D-1- and D-2 receptor-expressing MSNs based on BAC transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein under the control of the D-1 or D-2 promoter. They propose that neurons that pause to promote licking are D-2-expressing, and neurons that fire to promote licking are D-1-expressing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu XY, Ghasemzadeh MB, Kalivas PW. Expression of D1 receptor, D2 receptor, substance P and enkephalin messenger RNAs in the neurons projecting from the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci. 1998;82:767–780. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Lim BK, Huang KW, Grueter BA, Rothwell PE, Malenka RC. Anhedonia requires MC4 receptor-mediated synaptic adaptations in nucleus accumbens. Nature. 2013;487:183–189. doi: 10.1038/nature11160. This study used nucleus accumbens slices from BAC transgenic mice expressing tdTomato in D-1- and EGFP in D-2- expressing MSNs and demonstrated that restraint stress, which decreased food intake, body weight, and sucrose preference, decreased excitatory synaptic strength (AMPA/NMDA ratio) in D-1- but not D-2-expressing MSNs. Nucleus accumbens microinjection of an AAV expressing a peptide (G2CT-Pep) that prevents endocytosis of AMPARs blocked the stress-induced decrease in excitatory synaptic strength, food intake, and sucrose preference. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Echo JA, Lamonte N, Christian G, Znamensky V, Ackerman TF, Bodnar RJ. Excitatory amino acid receptor subtype agonists induce feeding in the nucleus accumbens shell in rats: opioid antagonist actions and interactions with μ-opioid agonists. Brain Res. 2001;921:86–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]