Abstract

Background

Vegetarian diets may promote weight loss, but evidence remains inconclusive.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE and UpToDate databases were searched through September 22, 2014, and investigators extracted data regarding study characteristics and assessed study quality among selected randomized clinical trials. Population size, demographic (i.e., gender and age) and anthropometric (i.e., body mass index) characteristics, types of interventions, follow-up periods, and trial quality (Jadad score) were recorded. The net changes in body weight of subjects were analyzed and pooled after assessing heterogeneity with a random effects model. Subgroup analysis was performed based on type of vegetarian diet, type of energy restriction, study population, and follow-up period.

Results

Twelve randomized controlled trials were included, involving a total of 1151 subjects who received the intervention over a median duration of 18 weeks. Overall, individuals assigned to the vegetarian diet groups lost significantly more weight than those assigned to the non-vegetarian diet groups (weighted mean difference, −2.02 kg; 95 % confidence interval [CI]: −2.80 to −1.23). Subgroup analysis detected significant weight reduction in subjects consuming a vegan diet (−2.52 kg; 95 % CI: −3.02 to −1.98) and, to a lesser extent, in those given lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets (−1.48 kg; 95 % CI: −3.43 to 0.47). Studies on subjects consuming vegetarian diets with energy restriction (ER) revealed a significantly greater weight reduction (−2.21 kg; 95 % CI: −3.31 to −1.12) than those without ER (−1.66 kg; 95 % CI: −2.85 to −0.48). The weight loss for subjects with follow-up of <1 year was greater (−2.05 kg; 95 % CI: −2.85 to −1.25) than those with follow-up of ≥1 year (−1.13 kg; 95 % CI: −2.04 to −0.21).

Conclusions

Vegetarian diets appeared to have significant benefits on weight reduction compared to non-vegetarian diets. Further long-term trials are needed to investigate the effects of vegetarian diets on body weight control.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3390-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: Vegan diet, Lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet, Overweight, Obesity, Energy restriction

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a worldwide public health problem. Between 1980 and 2013, the proportion of overweight or obese adults increased from 28.8 to 36.9 % in men and from 29.8 to 38.0 % in women.1 Obesity is associated with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, and all-cause mortality.2 It is estimated that overweight and obesity were the cause of 3.4 million deaths and 3.8 % of disability-adjusted life-years worldwide in 2010.3 The prevalence of obesity has increased sharply in the past four decades in the United States, and two-thirds of American adults are overweight or obese.4 In 1998, management of overweight or obese individuals accounted for 9.1 % of annual U.S. medical expenditures.5

As part of efforts to reduce obesity and associated morbidity, various diets for weight reduction have been proposed. Vegetarian dietary patterns have been reported to be associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and all-cause mortality.6 The two major types of vegetarian diets are the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet, in which meats are avoided but consumption of milk and eggs is allowed, and the vegan diet, in which all products originating from animals are avoided. Thus far, the results of randomized clinical trials7–19 investigating the affect of vegetarian diets on weight reduction have been inconclusive, which could be due to the diverse populations, small sample sizes, different intervention durations, and poor adherence. As there have been no studies with large sample sizes, we performed a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials conducted to date in order to compare the effect of vegetarian diets with that of non-vegetarian diets on weight reduction in the general population. We also investigated whether the effects of weight reduction differed between lacto-ovo-vegetarian and vegan diets.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

Adopting the Cochrane Collaboration search strategy,20 we searched PubMed via the NCBI Entrez system (1950 to September 22, 2014) and EMBASE via Ovid (1988 to September 22, 2014) for randomized controlled studies of the effects of vegetarian diets compared to non-vegetarian diets on weight reduction. Key words used to search for relevant publications included the following: (“weight” AND “vegetarian diet”) OR (“weight” AND “lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet”) OR (“weight” AND “vegan diet”), with the scope of the search limited to English literature. Bibliographies of identified studies and UpToDate Database 2014 were reviewed for additional reference. We contacted three original authors to clarify data.

Study Selection

We included studies that were randomized clinical controlled trials solely applying vegan or lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets compared to non-vegetarian diets, with the inclusion of changes in body weight as a study parameter or where this information could be derived by contacting the authors. We excluded non-original publications, abstracts of conferences, and studies for which details could not be obtained. Studies that included other interventions such as combined physical activity and diet interventions were also excluded, although studies where exercise was advised with dietary intervention were included.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

For every eligible study, we collected information on the year of publication, population characteristics, sample size, intervention type, follow-up period, and weight change. The means and standard deviations of weight change were obtained from all studies. For articles that did not report standard deviations,10,17,19 we imputed a change-from-baseline standard deviation using a correlation coefficient of 0.96 estimated from trials9,11,12,14,16 with available data based on Cochrane’s formula.21 For three studies9,11,15 with repeated measurements during the follow-up periods, we collected results at the 1-year time point. For one study10 that identified subjects’ dietary preferences for lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet or control diet before randomization, we attempted to separate the preference group from the no-preference group for comparison within each group. To explore study quality, we used the Jadad score, which takes into consideration the randomization appropriateness, blinded outcome assessment, and complete description of loss to follow-up. We then examined each component of the Jadad score as our study-level factor to see whether it affected the heterogeneity of the results.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Given the diversity in study design and populations, we employed a random effects model, and we also conducted a fixed effects model for sensitivity analysis.22 We calculated weighted mean differences for identical outcome measures in the vegetarian and non-vegetarian diet groups. We assessed heterogeneity of treatment effects in the included studies using the I-squared statistic and the chi-square test of the q statistic. We further evaluated study characteristics as potential sources of heterogeneity using meta-regression including type of intervention diet (vegan vs. lacto-ovo-vegetarian), type of dietary intervention (supplemented food vs. group session with dieticians), inclusion of energy restriction in the intervention diet (yes vs. no), study duration (greater vs. less than 1 year), gender involved in studies (females alone vs. both genders), overweight/obesity (selected individuals with body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25 vs. general population), population (patients vs. healthy subjects), study quality (Jadad score high: ≥ 3 vs. low: < 3), description of randomization procedures (yes vs. no), blinding (single or double vs. no) and dropout (analysis of possible effect vs. no). We conducted subgroup analysis by pooling effect estimates based on important domains of sources of bias and significant study-level factors in the meta-regression. To address the uneven study quality, we conducted sensitivity analyses only for high-quality studies. Publication bias was examined by constructing a funnel plot and was tested using the Begg19 method. All statistical procedures were conducted using Stata software (Version 12; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The work was not sponsored or supported by specific institutes.

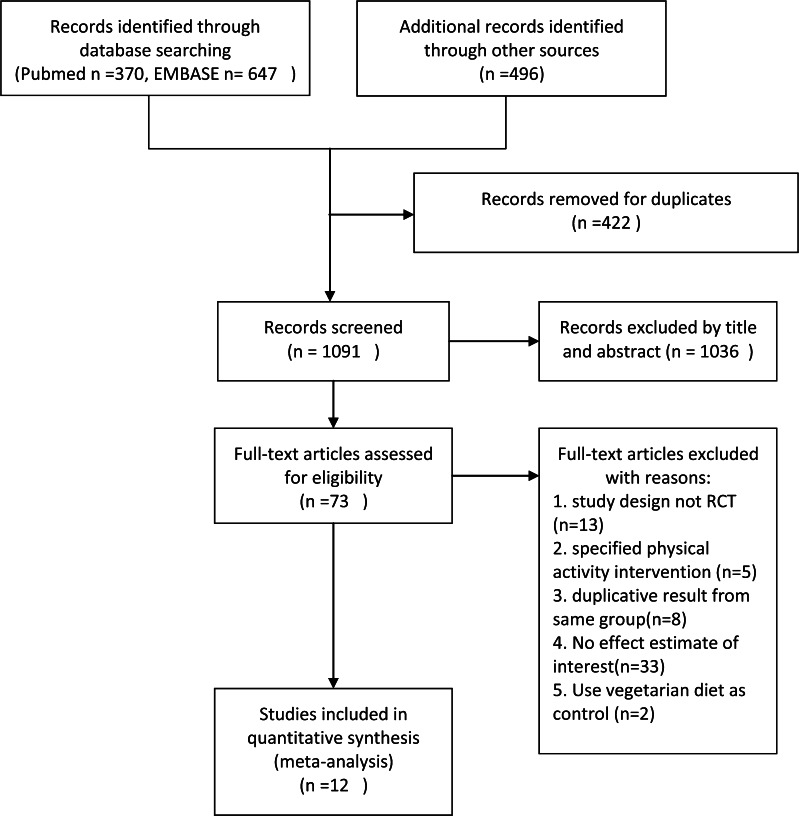

RESULTS

The literature search identified 1513 studies. After excluding 422 duplicates and 1036 articles based on title and abstract review, 73 articles remained for full-text evaluation (Fig. 1). We excluded 13 studies that were not original reports, five studies where the main intervention was a physical activity intervention, eight studies which were multiple reports of the same population, 33 studies that did not include information on outcomes of interest, and two studies that compared vegan diets versus lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets. After these exclusions, we identified 12 studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were used in the final analysis.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram. RCT randomized controlled trial

Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 12 included trials. A total of 1151 subjects were included in this analysis, with baseline age ranging from 18 to 82 years. Three studies targeted postmenopausal women and one study focused on premenopausal women. For the studies that enrolled both genders, the proportion of male subjects ranged from 13 to 52 %. The mean baseline BMI ranged from 25 to 53 kg/m2. Six studies recruited overweight or obese patients, five studies enrolled people with type 2 diabetes, and one study included patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Vegan and lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets were chosen as intervention diets in eight and four studies, respectively. Among the eight trials on vegan diets, six used low-fat (≤ 10 %) recipes, while one adopted high-carbohydrate (60 %) ingredients. The design of non-vegetarian diets varied across studies and included low-fat, anti-diabetes, lipid-lowering, and weight reduction recipes. Of the six studies that applied energy restriction, five applied the restriction to both the intervention and control arms, 8,10–12,16 while one study designated 1 week of energy restriction solely to the intervention arm.23 Among the remaining six studies without energy restriction in the intervention arms, one adopted energy restriction in their control groups who were overweight.9 The follow-up periods among these trials ranged from 8 weeks to 2 years. Meta-regression identified the length of follow-up (i.e., ≥ 1 year vs. < 1 year) as the only study-level factor with borderline significance (P = 0.045) for the pooling outcome (Figs. 2 and 3).

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Trials Comparing Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Diets

| Study | Key population characteristics | Total N | Age† | Men, % | BMI† | Intervention | Control | Energy restriction | Duration||

(weeks) |

Jadad score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mishra 20137 | Overweight or type 2 diabetes | 291 | 45 ± 15 | 17 | 35 ± 1 | Low-fat vegan | Habitual diet | No | 18 | 2 |

| Kahleova 20138 | Type 2 diabetes | 74 | 30–70 | 47 | 25–53 | Vegan | Diabetes diet | Yes | 24 | 3 |

| Barnard 20099 | Type 2 diabetes | 99 | 27–82 | 39 | 25–43 | Low-fat vegan | Diabetes diet | Yes, for BMI > 25 in control arm | 74 | 3 |

| Burke 200810 | Sedentary, overweight | 200 | 18–55 | 13 | 27–43 | Lacto–ovo–vegetarian | Low fat | Yes § | 24–72 | 3 |

| Turner 200711 | Overweight, obese postmenopausal women | 62 | 44–73 | 0 | 26–44 | Low-fat vegan | NCEP diet | Yes | 48–96 | 2 |

| Mahon 200712 | Postmenopausal women | 25 | 58 ± 2 | 0 | 29 ± 1 | Lacto–ovo–vegetarian | Habitual diet | Yes | 9 | 2 |

| Gardner 200713 | Premenopausal overweight and obese women | 155 | 25–50 | 0 | 27–40 | Low-fat lacto–ovo–vegetarian | Calories from carbohydrate, protein and fat split 40/30/30 | No | 48 | 4 |

| Barnard 200516 | Overweight or obese postmenopausal women | 64 | 44–73 | 0 | 26–44 | Low-fat vegan | NCEP diet | Yes | 14 | 2 |

| Dansinger 200515 | Overweight or obese | 80 | 22–72 | 52 | 27–42 | Low-fat lacto–ovo–vegetarian |

High-fat, high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet | No | 8–48 | 5 |

| Nicholson 199917 | Type 2 diabetes | 11 | 34–74 | 46 | – | Low-fat vegan | 55–60 % of calories from carbohydrates, < 30 % from fat | No | 12 | 2 |

| Prescott 198819 | Healthy omnivores | 64 | 18–60 | 40 | – | High-protein lacto–ovo–vegetarian | High protein from meat, 1.5 g/Kg/day | No | 12 | 2 |

| Skoldstam 197918 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 26 | 35–66 | 27 | – | Lacto–ovo–vegetarian | Habitual diet | Yes, 1st week intervention arm only | 10 | 1–2 |

Jadad score: briefly rates study quality by way of randomization, blinding, and follow-up using a 0–5 scoring system

Ranges of value

Values are reported as number (%)

§If weight < 90.5 Kg, then 1200 Kcal for women and 1500 Kcal for men; if weight > 90.5 Kg, then 1500 Kcal for women and 1800 Kcal for men

||The duration of follow-up in each study is equal to the intervention period except for three studies: Dansinger, 8 weeks of intervention; Turner, 14 weeks of intervention; and Gardener, 8 weeks of intervention

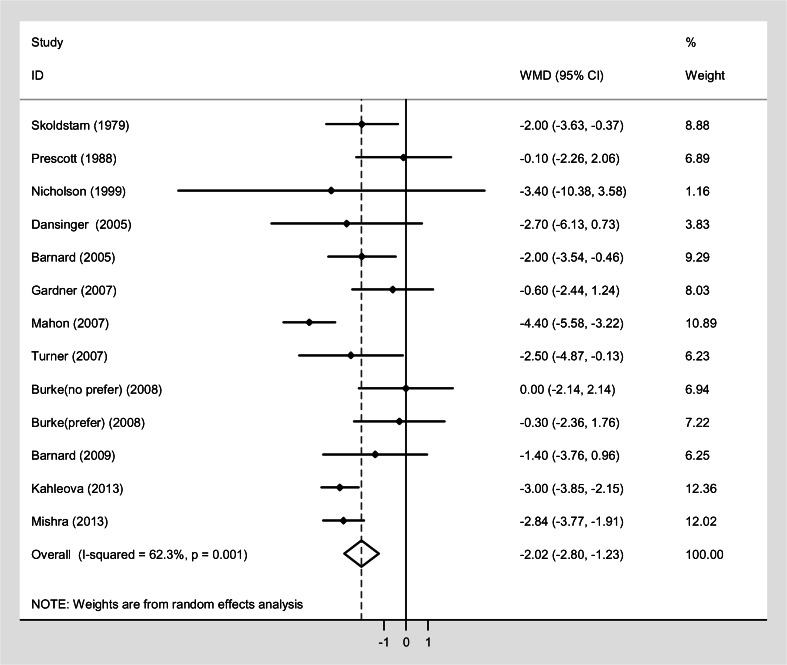

Fig. 2.

Pooled weighted mean differences in weight reduction between vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets. Effects on estimated weight reduction for each study depicted as solid squares; error bars indicate 95 % CIs. The pooled estimate of −1.99 kg (95 % CI, −2.72 to −1.25) of weight loss is shown as the diamond. RE random effect, Weight inverse variance weight, WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval

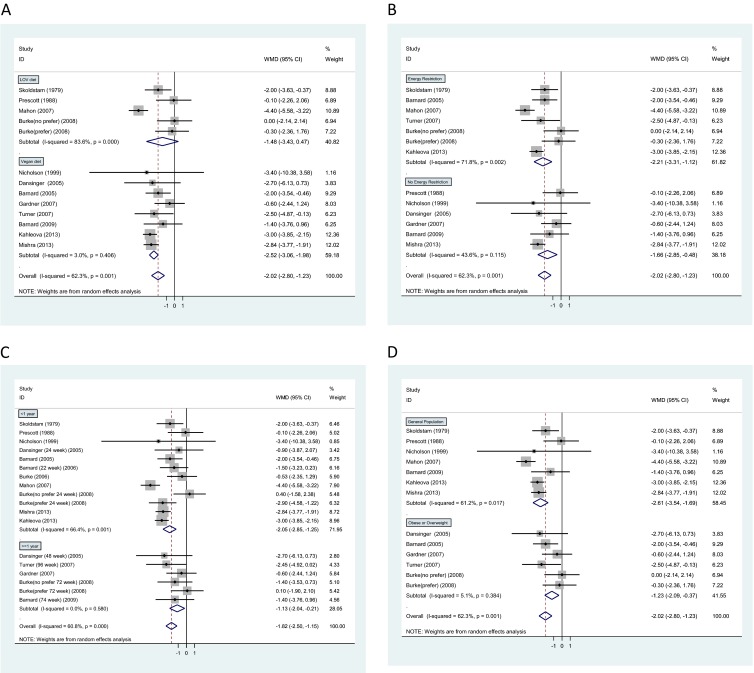

Fig. 3.

Pooled weighted mean differences in weight reduction by subgroup. Effects on estimated weight reduction for each study depicted as solid squares; error bars indicate 95 % CIs. The pooled estimate of weight loss is shown as the diamond. RE random effect, Weight inverse variance weight, WMD weighted mean difference, CI confidence interval. A. Vegan diets vs. lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV) diets. Vegan diets were defined as avoiding all animal products, whereas lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets avoided meat but consumption of milk and eggs was allowed. B. Energy restriction vs. no energy restriction group. C. Follow-up < 1 year vs. ≥ 1 year. D. General population vs. overweight or obese population. Normal represents general population including normal-weight, overweight and obese individuals

Quality of Trials

Most of the randomized clinical trials reported various approaches for evaluating adherence and causes of loss to follow-up. Blinding is difficult in dietary interventions, and only two trials13,15 adopted a blind study design. Therefore, we categorized the 13 studies based on Jadad score24 as either high quality (n = 5, score ≥ 3) or low quality (n = 7, score < 3). Meta-regression analysis revealed that randomization, blinding, follow-up, and type of dietary intervention were not important effect modifiers.

Weight Change

Individuals assigned to vegetarian diets lost more weight than those assigned to control diets (weighted mean difference, −2.02 Kg; 95 % CI: −2.80 to −1.23) in interventions ranging from 9 to 74 weeks. We observed a significant heterogeneity in weight change (P = 0.001 test for heterogeneity, I2 = 62.3 %), and consequently conducted subgroup analyses in terms of intervention type, follow-up duration, and population characteristics. Individuals randomized to vegan diets (eight studies, intervention ranging from 12–48 weeks) lost more weight than those randomized to lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets (four studies, intervention ranging from 9 to 74 weeks), relative to their respective counterparts consuming control diets. Specifically, the weighted mean weight reduction for individuals with vegan diets was −2.52 kg (95 % CI: −3.02 to −1.98, P = 0.406 for heterogeneity, subtotal I2 = 3.0 %), whereas the corresponding weight change for lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets was −1.48 kg; (95 % CI: −3.43 to −0.47, P < 0.001 for heterogeneity, subtotal I2 = 83.6 %).

Six trials of vegetarian diets with energy restriction in interventions ranging from 9 to 48 weeks showed greater weight loss (−2.21 Kg; 95 % CI: −3.31 to −1.12, P = 0.002 for heterogeneity, subtotal I2 = 71.8 %) than diets in those six trials without energy restriction (−1.66 Kg; 95 % CI: −2.85 to −0.48, P = 0.115 for heterogeneity, subtotal I2 = 43.6 %) in interventions ranging from 8 to 74 weeks. Weight loss achieved in 11 trials lasting less than 1 year (range: 6–24 weeks) was greater (−2.05 kg; 95 % CI: −2.85 to −1.25, P = 0.001 for heterogeneity, subtotal I2 = 66.4 %) than in the five trials following subjects for 1 year or more (range: 8–74 weeks) (−1.13 kg; 95 % CI: −2.04 to −0.21, P = 0.580 for heterogeneity, I2 = 0 %). In seven trials that included the general population in interventions ranging from 9 to 74 weeks, vegetarian diets resulted in substantially greater weight reduction (−2.61 kg; 95 % CI: −3.54 to −1.69, P = 0.02 for heterogeneity, subtotal I2 = 61.2 %) than in five trials restricted to overweight or obese individuals at baseline in interventions ranging from 8 to 48 weeks (−1.23 kg; 95 % CI: −2.09 to −0.37, P = 0.38 for heterogeneity, I2 = 5.1 %). In sensitivity analyses, the results of high-quality trials (−1.43 kg; 95 % CI: −2.51 to −0.35 I2 = 57.8 %) and trials of low quality (−2.51 kg; 95 % CI: −3.53 to −1.49 I2 = 60.3 %) were heterogeneous but not significantly different.

Publication Bias

The funnel plot showed slight asymmetry in both the small and large sample groups. Nevertheless, we found no evidence of substantial publication bias (Begg’s test P = 0.32) (Supplementary Fig., available online).

DISCUSSION

In this meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing body weight changes between individuals consuming vegetarian diets and those consuming non-vegetarian diets, the former showed a reduction in weight of approximately 2 kg compared to the latter. Among individuals consuming vegetarian diets, interventions with vegan diets resulted in greater weight loss than those with lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets. Weight loss was also greater in trials with energy restriction. In addition, analyses indicated that intervention effects were attenuated over time after 1 year of follow-up, but remained worthy of integration into daily practice.

Observational studies have suggested an association between self-reported vegetarian diets and weight control.25–27 In fact, the results from observational studies are in agreement with our findings, but suggested an even stronger effect than that documented in randomized trials. A prospective matched cohort study of 116 individuals who followed strict vegetarian diets for 3 years showed a 15-kg weight reduction compared to the control group.28 While this may imply that participants with better adherence to a vegetarian diet could have more profound weight loss, it also might also be explained by self-selection, residual confounding, measurement error, or lack of repeated diet and lifestyle assessment. A long-term interventional study by Ornish et al. found a weight reduction of 10 kg at 1 year and 8 kg at 5 years compared to baseline in the group consuming a vegetarian diet, while the control group experienced an increase of 2 kg.29 However, the sample size was small, and the addition of moderate exercise could have contributed to the substantial weight reduction in the vegetarian diet group. In our meta-analysis, we avoided those issues by including only randomized controlled trials and excluding those that combined diet and exercise in the intervention.

For the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets, the random effects model showed no significant effect, whereas the fixed model yielded a small but significant effect on weight reduction. The difference between the results of the fixed and random effects models could be due to limited statistical power in the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets subgroup (number of studies = 5) in the random effects model. Therefore, more studies are needed to examine the effects of lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets. As the total energy intake was not adjusted in the studies that assigned meals to two groups,8,17,19 it is not clear whether the different weight reduction effects between vegan and lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets was due to the discrepant total energy intake in the two dietary patterns.

A possible mechanism underlying the effect of vegetarian diets on weight reduction may be the abundant intake of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Whole-grain products and vegetable generally have low glycemic index values, and fruits are rich in fiber, antioxidants, phytochemicals, and minerals.2 Viscous fiber, around 20 to 50 % in whole-grain products, could delay gastric emptying and intestinal absorption.30 Several prospective studies have reported an inverse association between fiber consumption and weight loss. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study identified a significant association between dietary fiber intake and lower body weight at baseline in both whites and blacks.31 In the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), women who had greatly increased their fiber intake reported a mean weight gain that was 1.52 kg less than that in women who reported a small increase in fiber intake.32 He et al.33 further found that women in the NHS with the largest increase in fruit and vegetable intake had a 28 % lower risk of major weight gain (≥ 25 kg) than those with lowest intake. A meta-analysis that included 20 small randomized controlled trials showed that soluble fiber supplementation was not efficacious for enhancing weight loss,34 although this result cannot be generalized to long-term effects of fiber from foods on body weight.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first meta-analysis to examine the effect of a vegetarian diet on weight loss relative to other diets (e.g., the American Diabetes Association-recommended diet, the diet supported by the National Cholesterol Education Program, and the Atkins diet). We conducted an extensive literature search, thus diminishing the possibility of publication bias. However, we found significant heterogeneity among trials, which may have been largely due to different study designs, the variety of vegetarian diets, the presence or absence of energy restriction, suboptimal study quality as reflected in the lack of blindness in 11 out of 13 studies, a wide range of available dietary adherence from 51 to 83 %, and the intervention strategy (e.g., provided food or dietician instruction-based). Although we did comprehensive subgroup analysis, the reliability of results might be limited by the relatively small sizes of the subgroups. While this meta-analysis provides evidence that vegetarian diets are more effective than non-vegetarian diets for weight loss, multiple gaps in the literature remain. For example, while our analysis suggested attenuation of effects over time, in agreement with the wider literature on dietary interventions for weight loss, most of the trials included in the meta-analysis lasted less than 12 months, and none lasted more than 18 months. Therefore, the long-term effects of vegetarian diets on body weight remain unsettled. The short duration of these trials also limits the available information on other clinically relevant outcomes such as cardiovascular morbidity and cardiovascular risk factors. Hence, further intervention trials are warranted to explore the long-term effects of vegetarian diets on weight loss and clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, vegetarian diets, and vegan diets in particular, appear to have beneficial effects on weight reduction. However, these benefits were attenuated over time. Longer-term intervention trials are needed to investigate the effect of vegetarian diets on weight control and cardiometabolic risk.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 40 kb)

Acknowledgments

Dr. Chung Hsieh, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, provided conceptual advice, and Dr. Stephanie Smith-Warner provided nutritional knowledge and statistical advice.

Support

This work was supported by NIH grants P30DK46200 and 1U54CA155626.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu FB, editor. Obesity Epidemiology. 1. Boston: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States–gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: how much, and who's paying? Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W3-219–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets: what do we know of their effects on common chronic diseases? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1607S–12. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra S, Xu J, Agarwal U, Gonzales J, Levin S, Barnard ND. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a plant-based nutrition program to reduce body weight and cardiovascular risk in the corporate setting: the GEICO study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(7):718–24. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahleova H, Matoulek M, Bratova M, Malinska H, Kazdova L, Hill M, et al. Vegetarian diet-induced increase in linoleic acid in serum phospholipids is associated with improved insulin sensitivity in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/nutd.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, Turner-McGrievy G, Gloede L, Green A, et al. A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1588S–96. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke LE, Warziski M, Styn MA, Music E, Hudson AG, Sereika SM. A randomized clinical trial of a standard versus vegetarian diet for weight loss: the impact of treatment preference. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(1):166–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner-McGrievy GM, Barnard ND, Scialli AR. A two-year randomized weight loss trial comparing a vegan diet to a more moderate low-fat diet. Obesity. 2007;15(9):2276–81. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahon AK, Flynn MG, Stewart LK, McFarlin BK, Iglay HB, Mattes RD, et al. Protein intake during energy restriction: effects on body composition and markers of metabolic and cardiovascular health in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26(2):182–9. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, Kim S, Stafford RS, Balise RR, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297(9):969–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.9.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, Turner-McGrievy G, Gloede L, Jaster B, et al. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(8):1777–83. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293(1):43–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnard ND, Scialli AR, Turner-McGrievy G, Lanou AJ, Glass J. The effects of a low-fat, plant-based dietary intervention on body weight, metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. Am J Med. 2005;118(9):991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicholson AS, Sklar M, Barnard ND, Gore S, Sullivan R, Browning S. Toward improved management of NIDDM: a randomized, controlled, pilot intervention using a lowfat, vegetarian diet. Prev Med. 1999;29(2):87–91. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skoldstam L. Fasting and vegan diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1986;15(2):219–21. doi: 10.3109/03009748609102091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescott SL, Jenner DA, Beilin LJ, Margetts BM, Vandongen R. A randomized controlled trial of the effect on blood pressure of dietary non-meat protein versus meat protein in normotensive omnivores. Clin Sci (Lond) 1988;74(6):665–72. doi: 10.1042/cs0740665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6964):1286–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook For Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoldstam L, Larsson L, Lindstrom FD. Effect of fasting and lactovegetarian diet on rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1979;8(4):249–55. doi: 10.3109/03009747909114631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Diet and body mass index in 38000 EPIC-Oxford meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(6):728–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy ET, Bowman SA, Spence JT, Freedman M, King J. Popular diets: correlation to health, nutrition, and obesity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(4):411–20. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newby PK, Tucker KL, Wolk A. Risk of overweight and obesity among semivegetarian, lactovegetarian, and vegan women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(6):1267–74. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacks FM, Castelli WP, Donner A, Kass EH. Plasma lipids and lipoproteins in vegetarians and controls. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(22):1148–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197505292922203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, Armstrong WT, Ports TA, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart. Trial Lancet. 1990;336(8708):129–33. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91656-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koh-Banerjee P, Rimm EB. Whole grain consumption and weight gain: a review of the epidemiological evidence, potential mechanisms and opportunities for future research. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(1):25–9. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludwig DS, Pereira MA, Kroenke CH, Hilner JE, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, et al. Dietary fiber, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1539–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB, Rosner B, Colditz G. Relation between changes in intakes of dietary fiber and grain products and changes in weight and development of obesity among middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):920–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He K, Hu FB, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC, Liu S. Changes in intake of fruits and vegetables in relation to risk of obesity and weight gain among middle-aged women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(12):1569–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pittler MH, Ernst E. Guar gum for body weight reduction: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2001;110(9):724–30. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 40 kb)