Abstract

In smaller single-center studies, cirrhotic patients are at a high readmission risk but a multi-center perspective study is lacking.

Aim

To evaluate the determinants of 3-month readmissions in cirrhotic inpatients using the prospective 14-center NACSELD (North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease) cohort.

Methods

Cirrhotics hospitalized for non-elective indications were consented and followed for 3-months post-discharge. The number of 3-month readmissions and their determinants on index admission and discharge were calculated. We used multivariable logistic regression for all readmissions, and for hepatic encephalopathy (HE), renal/metabolic and infection-related readmissions. A score was developed using admission/discharge variables for the total sample, which was validated on a random half of the total population.

Results

1353 patients were enrolled, 1177 were eligible on discharge and 1013 had 3-month outcomes. Readmissions occurred in 53% (n=535;316 with one, 219 with ≥2), with consistent rates across sites. The leading causes were liver-related (n=333, HE, renal/metabolic and infections). Cirrhotics with worse MELD, diabetes, those taking prophylactic antibiotics and with prior HE, were more likely to be readmitted. The admission model included MELD and diabetes (c-statistic=0.64; after split-validation 0.65). The discharge model included MELD, proton pump inhibitor use and lower length-of-stay (c-statistic=0.65; after split-validation 0.70). 30% of readmissions could not be predicted. Patients with liver-related readmissions consistently had index-stay nosocomial infections as a predictor for HE, renal/metabolic and infection-associated readmissions (OR 1.9–3.0).

Conclusions

Three-month readmissions occurred in about half of discharged cirrhotics, which were associated with cirrhosis severity, diabetes and nosocomial infections. Close monitoring of advanced cirrhotics and prevention of nosocomial infections could reduce this burden.

Keywords: Hepatic Encephalopathy, Acute Kidney Injury, Nosocomial Infection, Proton Pump Inhibitors, Length of stay

Readmissions after hospital discharge are a major healthcare burden from a medical, financial and psycho-social perspective in the United States (US)(1). This is a key quality measure, and evaluation of the reasons for readmission is critical to reduce their rate(2). One of the leading causes of morbidity, hospitalization and readmissions in the US is liver cirrhosis(3, 4), which remains a challenge, even when compared to other medical populations(5). These patients are often hospitalized in the decompensated stage due to liver-related complications such as hepatic encephalopathy (HE), infections and, renal/metabolic issues(3). In smaller studies, there was a high 30-day readmission rate predicted by cirrhosis severity, complications, and co-morbid conditions such as diabetes(6–9). Models created by these studies do not readily extend to other centers and may not provide generalizable insight into the readmission risk(7). A multicenter characterization of these readmissions, which identify tangible areas for intervention to reduce readmission risk, is lacking(6, 8).

The North American Consortium for the study of End-stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) is a prospective study involving tertiary-care hepatology centers that enrolls cirrhotic inpatients and follows them through hospitalization and 3-months post-discharge(10). We used the NACSELD database to characterize the rate and determinants of readmissions within 3-months of hospital discharge after non-elective hospitalization.

Methods

Subjects enrolled in NACSELD are a prospective cohort of cirrhotics admitted for non-elective reasons. Cirrhosis was diagnosed using biopsy, endoscopic or radiological evidence of portal hypertension or cirrhosis, and/or signs of hepatic decompensation [hepatic encephalopathy (HE), ascites, variceal bleeding, jaundice]. We excluded patients with HIV, an unclear diagnosis of cirrhosis, post-transplant patients, those admitted electively or in whom consent could not be obtained. All subjects or their family members gave informed consent. Data were collected regarding cirrhosis severity including MELD (model for end-stage liver disease) score(11), hospitalization reasons, medication use, cirrhosis complications and organ failures, nosocomial infections and discharge details. Subjects were followed for 3-months or more post-discharge using systematic phone calls, evaluation of medical records and interviews to evaluate outcomes either within the discharging health system or elsewhere. Death, liver transplant and readmission details were recorded in a novel REDCAP database(12). We compared the admission and discharge details of patients who were/were not readmitted. Sites were geographically divided into four main regions [Region 1: Northern US (Yale, Univ. Pennsylvania, Mayo Rochester and Univ. Rochester), Region 2: South/Mid-Atlantic (Virginia Commonwealth Univ., Richmond VAMC, Emory Univ. and Mercy Medical Center), Region 3: Southwest US (Baylor, Univ. Colorado, Univ. Texas, Mayo Scottsdale) and Canada (Univ. Alberta and Toronto)] which were also input into the logistic regression models.

To analyze factors predicting readmission(s), two logistic regression models with 3-month readmission as the dependent variable were created(13). The first model was based on variables from the day of index hospitalization, while the second model was based on variables from the day of index hospitalization discharge. These variables encompassed demographics, cirrhosis etiology and severity, geographic location, reason for hospitalization, infections, medications, diabetes, and laboratory values. Additional variables added to the day of discharge model were presence of a nosocomial infection (defined as an infection diagnosed >48 hours after admission) and length of stay (LOS).

We divided readmission causes into liver-related and liver-unrelated. Liver-related causes included HE, renal/metabolic [acute kidney injury (AKI)(14), electrolyte abnormalities and issues with ascites and edema], infections [spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and bacteremia, respiratory, skin/soft-tissue, urinary tract or other infections], gastrointestinal bleeding, and hepatic hydrothorax. Subjects could have more than one liver-related reason for admission. All other admissions were liver-unrelated (cardiovascular, respiratory, orthopedic, procedure-related and others). Elective admissions could be liver-related transplant, transjugular intra-hepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) placement, hepatocellular cancer management] or unrelated.

We also performed logistic regression for the major reasons for readmission individually using the same methods as above. Since a patient could have several reasons for readmission which were not mutually exclusive, the team defined the main reason, which was then used to analyze the specific readmission regression models. ‘C’ statistics were computed for the model based on either admission or discharge variables. The two models were compared using the method of DeLong, et. al(15). Using a random sample of 50% of the subjects, the validity of the models was confirmed.

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards in all participating centers.

Results

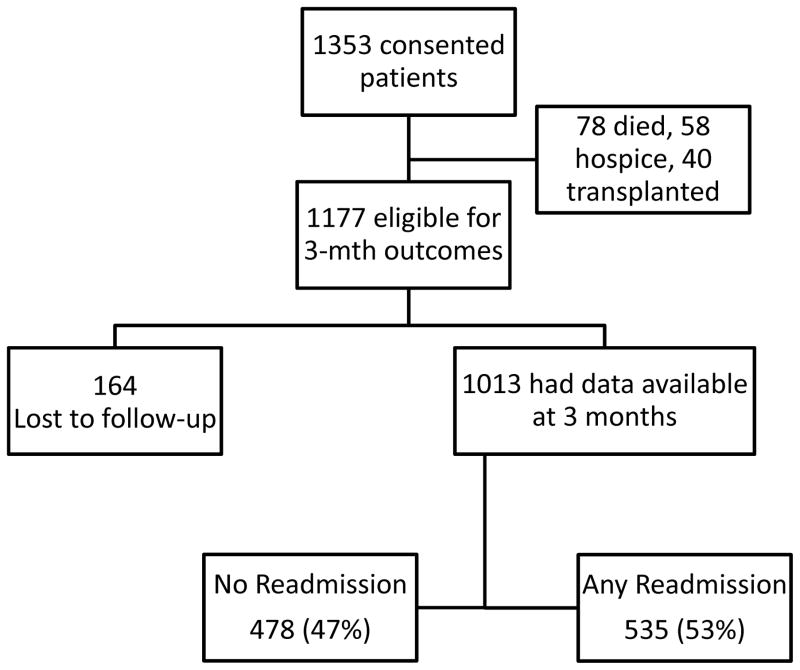

Patients were recruited from 14 centers in the US and Canada from December 1, 2013 through May 1, 2015. 1,768 potentially eligible subjects were approached; 259 refused to give informed consent while 156 did not meet eligibility criteria (92 were hospitalized electively, 43 could not consent and did not a caregiver to consent on their behalf, and 21 had a prior transplant). Therefore ultimately, 1,353 patients gave informed consent and were followed through the hospitalization (Figure 1). During index hospitalization 78 patients died, 40 were transplanted and 58 were discharged to hospice. After excluding these patients, 1,177 subjects remained, of which 1013 (86%) completed 3-month follow-up and 164 patients were lost-to follow-up. Insurance status was Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS 49% : Medicare in 41%, Medicaid 8%), private insurance in 39%, Veterans 5% and none in 7%.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study.

Details of index admission

Liver-related reasons comprised the majority of admissions with renal/metabolic issues being the leading cause (n=513), followed by infections (n=250), HE (n=154), GI bleeding (n=127) and others (n=296). There was a significantly lower LOS in subjects with GI bleeding (7.4±6.1 days) compared to the remainder (infection 11.3±10.4, HE 9.1±11.4, renal/metabolic 8.3±8.1, and others 8.3±8.4 days p=0.03).

Overall outcomes at 3-months

The majority was alive without transplant (n=810, 80%). The rest were dead without transplant (n=111, 11%) or alive after receiving a liver transplant (n=92, 9%). The majority of discharges were to the patients’ home (90%); rest were to nursing facilities (10%).

Overall 3-month Readmissions

Fifty-three percent of patients (535/1013) experienced at least one readmission (Table 1). The leading reasons for readmission were liver-related, specifically HE and renal/metabolic issues (Table 2). Of these 535, 316 had only one readmission (59%), while 219 (41%) had >1 readmission (139 patients admitted twice, 54 admitted thrice and 26 admitted ≥ four times). HE and renal/metabolic issues remained the major reasons for repeated readmissions. In the 139 patients who were admitted twice: 56 were admitted twice due to HE, 43 due to renal/metabolic issues, 19 (5 hepatic hydrothorax, 4 GI bleeding, 9 infection and 1 other) were other liver-related and 21 due to liver-unrelated reasons. In the 53 patients admitted three times: 20 were due to HE, 17 due to renal/metabolic reasons, and the remainder due to other liver-related (n=10, 5 infection, 3 hydrothorax requiring TIPS, 2 others) and liver-unrelated (n=6). A similar pattern was seen in the 26 patients admitted ≥ four times (HE in 16, 8 for renal/metabolic issues and two liver-unrelated).

Table 1.

Details of cirrhotic patients who did not require 3-month readmission compared to those who did. All non-percentage values are in mean ± SD and significant p-values are in bold.

| Not readmitted in 3 months (n=478) | Readmitted in 3 months (n=535) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 57.2 ± 10.0 | 57.0 ± 10.2 | 0.82 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender | 62% | 65% | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Alcoholic etiology | 43% | 43% | 0.95 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 33% | 40% | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| On date of index admission | |||

|

| |||

| Admitted with infection | 29% | 26% | 0.32 |

|

| |||

| WBC count (/1000 mm3) | 6.8 ± 4.7 | 6.8 ± 4.3 | 0.88 |

|

| |||

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 2.83 ± 0.64 | 2.73 ± 0.65 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| MELD score | 17.24 ± 6.58 | 18.95 ± 6.60 | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| PPI | 53% | 60% | 0.05 |

|

| |||

| Beta-blockers | 44% | 42% | 0.48 |

|

| |||

| SBP prophylaxis | 13% | 22% | 0.0002 |

|

| |||

| Lactulose | 50% | 61% | 0.0005 |

|

| |||

| Rifaximin | 35% | 41% | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Insurance Coverage | 0.60 | ||

| Medicaid | 8% | 10% | |

| Medicare | 43% | 39% | |

| Supplemental | 1% | 1% | |

| Private | 38% | 38% | |

| VA | 5% | 6% | |

| None | 6% | 8% | |

|

| |||

| During the index stay | |||

|

| |||

| Grade 3/4 HE | 11% | 15% | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Need for dialysis | 8% | 9% | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 6% | 6% | 0.83 |

|

| |||

| Shock | 3% | 2% | 0.59 |

|

| |||

| Nosocomial infection | 49% | 55% | 0.21 |

|

| |||

| Length of stay | 9.5 ± 10.5 | 9.3 ± 8.7 | 0.84 |

| On the date of discharge from the index readmission | |||

| WBC count (/1000 mm3) | 3.9 ± 5.9 | 3.9 ± 6.5 | 0.92 |

|

| |||

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.31 ± 3.16 | 3.35 ± 3.58 | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| MELD score | 16.30 ± 6.59 | 18.70 ± 6.45 | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| PPI | 63% | 67% | 0.21 |

|

| |||

| Beta-blockers | 43% | 38% | 0.09 |

|

| |||

| SBP prophylaxis | 23% | 29% | 0.07 |

|

| |||

| Lactulose | 60% | 68% | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Rifaximin | 44% | 47% | 0.45 |

|

| |||

| Discharge location | 0.74 | ||

| Home | 89% | 90% | |

| Nursing Home | 11% | 10% | |

HE: hepatic encephalopathy, WBC: white blood cell, PPI: proton pump inhibitors, SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, MELD: model for end-stage liver disease score (validated cirrhosis severity logarithmic score of INR, serum bilirubin and creatinine)

Table 2.

Reasons for the first readmission within 3-months of the index hospitalization

| Reasons for readmission | Total Number (n=535)* |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 127 |

|

| |

| Renal and metabolic issues (total) | 119* |

| Anasarca | 67 |

| AKI | 41 |

| Hyponatremia | 7 |

| Hypo/hyperglycemia | 3 |

| Hypo/hyperkalemia | 9 |

|

| |

| Infection (total) | 87* |

| Sepsis and bacteremia | 34 |

| SBP | 14 |

| Skin/soft-tissue | 10 |

| C difficile | 8 |

| Pneumonia | 7 |

| Urinary tract infection | 7 |

| Cholangitis | 3 |

| Osteomyelitis | 2 |

| Other | 4 |

|

| |

| Elective (total) | 47 |

| Liver transplant | 25 |

| TIPS Placement | 14 |

| HCC therapy | 8 |

|

| |

| GI bleeding (total) | 41 |

| Upper GI non-variceal | 23 |

| Upper GI variceal | 16 |

| Lower GI | 2 |

|

| |

| Hepatic hydrothorax | 13 |

|

| |

| Other liver-related conditions (portal vein thrombosis) | 32 |

|

| |

| Liver-unrelated | 84 |

|

| |

| Falls | 7 |

numbers may add to more than the stated total because some patients had more than one reason for readmission.

AKI: acute kidney injury defined by consensus criteria(14), SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, GI: gastrointestinal

When variables from the index admission were compared, patients were readmitted within 3-months had a significantly worse cirrhosis severity (higher MELD score, p=0.0001 and lower albumin, p=0.02) and a higher prevalence of diabetes (p=0.03, Table 1). Medication differences included a higher proportion of lactulose (indicative of HE, p=0.0005), SBP prophylaxis (p=0.0002) and proton pump inhibitor (PPI, p=0.05) use, and a trend towards greater use of rifaximin in re-hospitalized patients (p=0.06).

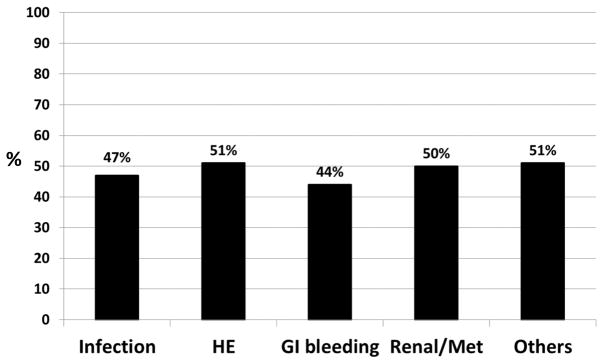

Interestingly, no significant difference in the proportion of patients readmitted based on the index admission etiology was found (Figure 2). This included index-stay infections, despite a worse cirrhosis severity and hospital course (Supplementary table 1). There were significant differences in the patient populations between the four regions based on admission and discharge variables (Supplementary table 2), but this did not impact the readmission rate significantly at the region or the individual center level (Supplementary table 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of subjects who were re-admitted in 3-months based on reason for index admission. No statistically significant difference was found (p=0.60). HE: hepatic encephalopathy, Renal/Met: renal or metabolic etiology

Details of the index hospitalization

There was a trend toward a higher readmission rate in patients with West-Haven grade III/IV HE(16) or a nosocomial infection. No significant impact was demonstrated with other organ failures (respiratory: mechanical ventilation or BiPAP, renal: renal replacement therapy, circulatory: shock requiring pressor therapy(17)) and LOS, on readmission rate. On discharge from the index hospitalizations, MELD score (p=0.0001) and lactulose use (p=0.01) differentiated the groups, with SBP prophylaxis (p=0.07) showing a positive trend (Table 1).

The model created using index admission variables showed the significant predictors of 3-month hospitalization to be liver disease severity as determined by the MELD score, lactulose use, SBP prophylaxis, diabetes, and lower serum albumin on admission (table 3). The discharge model showed the predictors of readmission to be MELD score, lactulose and PPI use and a shorter length of index hospitalization. The region-wise breakdown did not add to the models.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models from variables collected at admission and discharge predictive of 3-month readmissions

| Readmission | Admission variables | p-value | OR (95% CI) | Discharge variables | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| All readmissions | Diabetes | 0.07 | 1.36 (0.98–1.88) | LOS | 0.01 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) |

| Admitted with infection | 0.07 | 0.72 (0.51–1.03) | MELD score | 0.0002 | 1.07 (1.03–1.10) | |

| PPI | 0.07 | 1.49 (0.97–2.29) | ||||

| MELD score | 0.005 | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | Lactulose | 0.01 | 1.78 (1.13–2.79) | |

| Albumin | 0.04 | 0.78 (0.61–0.99) | ||||

| Lactulose | 0.02 | 1.46 (1.06–2.01) | ||||

| SBP Prophylaxis | 0.02 | 1.64 (1.07–2.51) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| HE | MELD score | 0.06 | 1.03 (1.00–1.07) | MELD score | 0.06 | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) |

| Lactulose | <0.001 | 3.21 (1.89–5.48) | Lactulose | 0.007 | 3.18 (1.38–7.30) | |

| Nosocomial infection | 0.02 | 1.97 (1.09–3.58) | Nosocomial infection | 0.03 | 2.25 (1.07–4.71) | |

|

| ||||||

| RenalMetabolic issues | Nosocomial infection | 0.07 | 1.92 (0.94–3.93) | SBP prophylaxis | 0.0002 | 3.77 (1.88–7.56) |

| SBP prophylaxis | 0.006 | 2.30 (1.27–4.15) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Infections | MELD score | 0.08 | 1.03 (1.00–1.07) | Male gender | 0.008 | 3.13 (1.34–7.33) |

| Male gender | 0.002 | 2.86 (1.46–5.59) | Admitted with infection | 0.06 | 2.03 (0.96–4.27) | |

| Nosocomial infection | 0.02 | 3.02 (1.20–7.62) | ||||

HE: hepatic encephalopathy, PPI: proton pump inhibitors, SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, MELD: model for end-stage liver disease score, LOS: length of stay

The c-statistic of the admission regression model was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.58–0.68) while that of the discharge model was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.59–0.69). Using 50% random sampling, admission models (c-statistic 0.65, 95% CI 0.59–0.72) and discharge models (c-statistic 0.70, 95% CI:0.83–0.78) were valid in predicting 3-month readmissions.

We used the most common liver-related causes of readmission (HE, renal/metabolic issues, and infection) as dependent variables in logistic regression (table 3). The model for HE readmissions showed that the same variables: a diagnosis of HE (as indicated by lactulose use), MELD score and nosocomial infections were predictive of a future HE readmission using both index-stay admission and discharge variables. Nosocomial infections also featured prominently in the models for infection and renal/metabolic readmissions, along with use of SBP prophylaxis and having an infection on the day of index admission.

To assess if insurance type or discharge location impacted patient readmission, variables for insurance class [(CMS insurance (Medicaid/Medicare/Supplementary), Private Insurance compared to others (VA or none)] in both admission and discharge models while location of the discharge (to nursing home compared to home) were included in discharge models only. For the model based on admission variables, insurance class was not a significant predictor (p = 0.12) while in the model based on discharge variables neither insurance class (p=0.20) nor discharge location (p=0.57) were significant predictors of 3 month readmission.

Discussion

The current experience notes that about half of hospitalized cirrhotic subjects in a multi-center North American Study require readmission within 3-months of hospital discharge. There are many readmissions related to potentially modifiable factors such as nosocomial infections and PPI use. Therefore efforts at discharge must focus on this high-risk group of patients to reduce the readmission rate.

Cirrhosis has emerged as a leading cause of readmissions in mixed inpatient populations(5, 18). Prior smaller cirrhosis studies have consistently highlighted this tremendous burden, which could be partly preventable(6–8). However current data have limited generalizability due to restricted practice constraints and populations in prior studies. Our multi-center experience shows that readmissions in 3-months remain an important issue regardless of the practice pattern or location within North America. NACSELD has a broad geographic reach and includes several practice patterns, including private University hospitals, hospitals catering to indigent populations and the Veterans affairs. The remarkable consistency of the readmission rates between centers highlights that this is a widespread reflection of clinical practice across North America.

Given the decision points to prevent readmission in any condition, we undertook a pragmatic approach of analyzing variables at the day of index admission and discharge. This should help clinicians plan readmissions prevention strategies based on data from these two time points, i.e. admission and discharge variables. Of note, the reason for index admission did not affect the risk for readmission. For example, when we studied infections as the reason for index hospitalization, we did not find a different readmission rate despite infected patients having a higher MELD score, worse in-hospital course regarding organ failures and a higher LOS. These findings are likely because the reason for index hospitalization may not be the dominant reason for continued stay, reflecting an evolving disease course during the hospitalization. Also, none of the inpatient organ failures were associated with readmissions. This could be due to their proximate impact on 30-day mortality rather than long-term prognosis(17). These findings point towards the importance of discharge variables in predicting readmission, and help clinicians appreciate that all cirrhotic inpatients, regardless of admission etiology or inpatient course, are at potential risk for readmission.

The detailed analysis of readmission indications from our large data sample is a key strength of the study. When liver-related readmissions (HE, infections and renal/metabolic abnormalities) were specifically studied, nosocomial infections during the index stay emerged as a significant factor. Nosocomial infection prevention is of critical importance not only to decrease LOS and improve in-hospital outcomes, but also to potentially decrease the risk for readmission(19). Cirrhotic subjects are at particular risk from nosocomial infections because of an impaired immune response and their natural history which consists of multiple antibiotic courses, hospitalizations and instrumentations(20, 21). The importance of infections is demonstrated by a recent study demonstrating in-hospital mortality in cirrhosis has decreased over time with the exception of those with infections(22, 23). Prior studies have shown that nosocomial and second infections are associated with increased 30-day mortality but this larger experience now extends their potential impact to the post-discharge period(10). Since susceptibility to nosocomial infections is related to the underlying liver disease severity, they were independently related to liver-related readmissions (HE, renal/metabolic issues and infections)(24). In addition, most nosocomial infections are preventable and therefore guidelines from CMS need to be urgently followed in this at-risk population(25).

Our results demonstrate that medications such as PPIs, SBP prophylaxis and lactulose, may influence re-hospitalizations. While the use of lactulose and antibiotic prophylaxis are markers of disease severity because they indicate prior HE and SBP respectively, the role of PPIs is of utmost importance from a disease-prevention standpoint. A prior smaller study restricted to infected cirrhotics from NACSELD demonstrated PPI use to be a predictor of future infections(26). These results extend it on to all hospitalizations. PPI therapy can impair immune response, alter gut microbiota, often a marker of advanced liver disease and ultimately is often not indicated in cirrhotic patients(27–29). Therefore discontinuation of unnecessary PPI therapy in cirrhotics, especially at discharge, could reduce complications and potentially, readmissions. The role of SBP prophylaxis has evolved, given the changes in bacteriology of SBP from predominantly gram-negative organisms that these antibiotics are aimed against, to gram-positive or resistant gram-negative organisms(30). Since SBP prophylaxis was related to readmissions in patients with ascites due to renal and metabolic issues, these patients should warrant careful post-discharge monitoring. However, we did not have data on whether the patients had actually received/filled the discharge medications or their adherence on these medications, which is a limitation of this study.

It is also interesting that a particular complication increased its risk in the subsequent 3-months, especially a diagnosis of HE and infections at the index stay or prior history of either predisposed to a readmission for the same condition on multi-variable analysis. HE in particular has emerged as a leading reason for readmission in a prior single-center and in our multi-center cohort(8) (31). This could be due to the dependence on a caregiver and the persistence of cognitive impairment after HE recovery, which leads to impaired insight, and difficulty with medication and clinician visit adherence(32, 33). HE can also impact the socio-economic status of patients and caregivers, which could hinder their ability to attend scheduled visits and may ultimately result in a preventable readmission(34). HE is similar to mild cognitive impairment in the non-cirrhotic population, a feature associated with readmissions(35). Therefore, careful follow-up of patients with HE and education of caregivers is of critical importance.

A longer LOS was associated with reduced readmission when the entire group was considered. While this seems counter-intuitive, since patients with more complicated courses tend to stay longer, we had excluded subjects who died or were discharged to hospice. The results therefore show that the included patients with longer LOS had a higher chance of recovering from their illness without dying from it, and the inpatient team potentially had time to provide adequate resources and post-discharge planning. Therefore, the current focus to minimize inpatient stay duration could potentially increase the readmission rate.

As several studies have noted in mixed medical populations and confirmed in our experience, the reasons for readmission may not be the indication for index hospitalization. This could be the reason for the moderate predictive capability of readmission models in prior medical inpatient and cirrhosis studies, which was also confirmed in our dataset(7, 36, 37). While most studies have focused on the 30-day readmission burden, we chose to use the longer 3-month window. The reasons for this were related to the ability of the MELD score to predict 3-month outcomes and also to get a more expansive view of the burden of readmission in cirrhotic patients(11). The 3-month interval has demonstrated to predict mortality after readmissions in cirrhosis(8, 38). Further restricting follow-up to 30-days post-discharge has been recently questioned for heart failure and should also be the case for cirrhosis(39).

The prevention of readmissions requires a concerted strategy between patients, caregivers, hospitals, outpatient medical staff and payors(40). CMS has initiated reimbursement reduction for readmissions for conditions such as myocardial infarction and heart failure; cirrhosis needs to be included in this regard(1). While every discharged cirrhotic patient should be considered at high risk for readmission given the moderate capability of our model, the current results highlight cirrhotic patients with a high MELD, those with HE, on PPI and SBP prophylaxis, and those who experienced a nosocomial infection are at the highest risk. The use of transitional care has greatly reduced the risk of readmissions in conditions such as congestive heart failure and could be an option for cirrhotic subjects(41). A recent single-center study in cirrhotic patients with ascites using this multi-disciplinary transitional care approach that included managing cirrhosis complications, ensuring optimal follow-up and prompt communication with outpatient teams, not only reduced readmissions but improved overall mortality(38). Another potential method for improvement is utilization of inpatient palliative care to ease and improve the symptomatic burden carried by cirrhotic patients(42). In non-cirrhotic subjects, such intervention has translated into lower 30-day readmissions(43). This approach needs to be applied in a multi-center strategic method to readmission prevention in patients with cirrhosis. We conclude that approximately half of the patients in a large, multi-center patient population with cirrhosis require at least one readmission within 3-months of hospital discharge. Measures that ensure close follow-up of patients with high MELD and a history of HE, re-evaluation for the need of PPI therapy and prevention of nosocomial infections may decrease this burden. Further research into a multi-center, inter-disciplinary approach that optimizes discharge suitability, fulfills palliative-care needs and improves post-discharge communications between patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals is ultimately required to prevent readmissions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support- The study was partly supported by Grifols pharmaceuticals through an investigator-initiated grant and partly through RO1DK089713 awarded to JSB. None of the funders were involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

The following coordinators and collaborators are acknowledged:

VCU: Ariel B Unser, Melanie B White, Nicole A Noble, Chathur Acharya, MD

McGuire VAMC: Edith A Gavis, Jawaid Shaw, MD, Andrew Fagan

University of Pennsylvania: Debolina Banerjee, Samuel Brayer

University of Alberta: Sylvia Kalainy

University of Toronto: Rebecca Laroux, Martha Orgill

Mayo Clinic, Rochester: Sakkarin Chirapongsathorn, MD

Yale University: Abdul Bhutta, MD, Randolph delarosa Rodriguez

University of Rochester: Krystle Bittner, Meredith Eggert

University of Colorado: Colin Jenks

Mercy Medical Center: Hemlata Lahori, Aparna Poonia

University of Texas, Houston: Sachin Batra

Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale: Meagan Kelly

Baylor University Medical Center: Tiana Purrington and Sara Leffingwell

Abbreviations

- NACSELD

North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- SBP

spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- GI

gastrointestinal

- TIPS

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting

Footnotes

Author Contributions- All authors were involved in data collection, entry and analysis and were also involved in drafting and critically revising the manuscript. JSB and LRT had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Fontanarosa PB, McNutt RA. Revisiting hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2013;309:398–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benbassat J, Taragin M. Hospital readmissions as a measure of quality of health care: advantages and limitations. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1074–1081. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States Part III: Liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1134–1144. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, Angeli P, Talwalkar J. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204–1207. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picker D, Heard K, Bailey TC, Martin NR, LaRossa GN, Kollef MH. The number of discharge medications predicts thirty-day hospital readmission: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:282. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0950-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J, Rakoski MO, Lok AS. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:247–252. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal AG, Rahimi RS, Clark C, Ma Y, Cuthbert JA, Rockey DC, Amarasingham R. An automated model using electronic medical record data identifies patients with cirrhosis at high risk for readmission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1335–1341. e1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman K, Tandra S, Forssell K, Vuppalanchi R, Burton JR, Jr, Nguyen J, Mullis D, et al. Incidence and predictors of 30-day readmission among patients hospitalized for advanced liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganesh S, Rogal SS, Yadav D, Humar A, Behari J. Risk factors for frequent readmissions and barriers to transplantation in patients with cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Olson JC, Subramanian RM, Brown G, et al. Second infections independently increase mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis: the North American consortium for the study of end-stage liver disease (NACSELD) experience. Hepatology. 2012;56:2328–2335. doi: 10.1002/hep.25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864–871. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression. 3. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong F, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Patton H, Kamath PS, Fallon MB, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. New consensus definition of acute kidney injury accurately predicts 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and infection. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1280–1288. e1281. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715–735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Biggins SW, Patton H, Fallon MB, et al. Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014;60:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.27077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong EL, Cheung AW, Leung MC, Yam CH, Chan FW, Wong FY, Yeoh EK. Unplanned readmission rates, length of hospital stay, mortality, and medical costs of ten common medical conditions: a retrospective analysis of Hong Kong hospital data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:149. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/index.html?redirect=/HospitalAcqCond/01_Overview.asp

- 20.Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Wong F, Reddy KR, Kamath PS. Bacterial infections in end-stage liver disease: current challenges and future directions. Gut. 2012;61:1219–1225. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merli M, Lucidi C, Giannelli V, Giusto M, Riggio O, Falcone M, Ridola L, et al. Cirrhotic patients are at risk for health care-associated bacterial infections. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanwal F. Decreasing mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:897–900. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt ML, Barritt AS, Orman ES, Hayashi PH. Decreasing mortality among patients hospitalized with cirrhosis in the United States from 2002 through 2010. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:967–977. e962. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez J, Gustot T. Management of bacterial infections in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012;56(Suppl 1):S1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/cms/index.html

- 26.O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Kamath PS, Patton HM, Biggins SW, Fallon MB, et al. Long-term use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors predict development of infections in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:753–759. e751–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajaj JS, Cox IJ, Betrapally NS, Heuman DM, Schubert ML, Ratneswaran M, Hylemon PB, et al. Systems Biology Analysis of Omeprazole Therapy in Cirrhosis Demonstrates Significant Shifts in Gut Microbiota Composition and Function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00268.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kedika RR, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Potential anti-inflammatory effects of proton pump inhibitors: a review and discussion of the clinical implications. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2312–2317. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merli M, Lucidi C, Di Gregorio V, Giannelli V, Giusto M, Ceccarelli G, Riggio O, et al. The chronic use of beta-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may affect the rate of bacterial infections in cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014 doi: 10.1111/liv.12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez J, Acevedo J, Castro M, Garcia O, de Lope CR, Roca D, Pavesi M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of infections by multiresistant bacteria in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2012;55:1551–1561. doi: 10.1002/hep.25532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saab S. Evaluation of the impact of rehospitalization in the management of hepatic encephalopathy. Int J Gen Med. 8:165–173. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S81878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajaj JS, Schubert CM, Heuman DM, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Topaz A, Saeian K, et al. Persistence of cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2332–2340. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riggio O, Ridola L, Pasquale C, Nardelli S, Pentassuglio I, Moscucci F, Merli M. Evidence of persistent cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;9:181–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bajaj JS, Riggio O, Allampati S, Prakash R, Gioia S, Onori E, Piazza N, et al. Cognitive dysfunction is associated with poor socioeconomic status in patients with cirrhosis: an international multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1511–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callahan KE, Lovato JF, Miller ME, Easterling D, Snitz B, Williamson JD. Associations Between Mild Cognitive Impairment and Hospitalization and Readmission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jgs.13593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tapper EB, Finkelstein D, Mittleman MA, Piatkowski G, Lai M. Standard assessments of frailty are validated predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2015;62:584–590. doi: 10.1002/hep.27830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, Kripalani S. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306:1688–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morando F, Maresio G, Piano S, Fasolato S, Cavallin M, Romano A, Rosi S, et al. How to improve care in outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites: a new model of care coordination by consultant hepatologists. J Hepatol. 2013;59:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaduganathan M, Bonow RO, Gheorghiade M. Thirty-day readmissions: the clock is ticking. JAMA. 2013;309:345–346. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.205110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ge PS, Runyon BA. Care coordination for patients with cirrhosis: a “win-win” solution for patients, caregivers, providers, and healthcare expenditures. J Hepatol. 2013;59:203–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for heart failure: predict or prevent? Circulation. 2012;126:501–506. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.125435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poonja Z, Brisebois A, van Zanten SV, Tandon P, Meeberg G, Karvellas CJ. Patients with cirrhosis and denied liver transplants rarely receive adequate palliative care or appropriate management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:692–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Connor NR, Moyer ME, Behta M, Casarett DJ. The Impact of Inpatient Palliative Care Consultations on 30-Day Hospital Readmissions. J Palliat Med. 2015 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.