ABSTRACT

Baculovirus-encoded inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins likely evolved from their host cell IAP homologs, which function as critical regulators of cell death. Despite their striking relatedness to cellular IAPs, including the conservation of two baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domains and a C-terminal RING, viral IAPs use an unresolved mechanism to suppress apoptosis in insects. To define this mechanism, we investigated Op-IAP3, the prototypical IAP from baculovirus OpMNPV. We found that Op-IAP3 forms a stable complex with SfIAP, the native, short-lived IAP of host insect Spodoptera frugiperda. Long-lived Op-IAP3 prevented virus-induced SfIAP degradation, which normally causes caspase activation and apoptosis. In uninfected cells, Op-IAP3 also increased SfIAP steady-state levels and extended SfIAP's half-life. Conversely, SfIAP stabilization was lost or reversed in the presence of mutated Op-IAP3 that was engineered for reduced stability. Thus, Op-IAP3 stabilizes SfIAP and preserves its antiapoptotic function. In contrast to SfIAP, Op-IAP3 failed to bind or inhibit native Spodoptera caspases. Furthermore, BIR mutations that abrogate binding of well-conserved IAP antagonists did not affect Op-IAP3's capacity to prevent virus-induced apoptosis. Remarkably, Op-IAP3 also failed to prevent apoptosis when endogenous SfIAP was ablated by RNA silencing. Thus, Op-IAP3 requires SfIAP as a cofactor. Our findings suggest a new model wherein Op-IAP3 interacts directly with SfIAP to maintain its intracellular level, thereby suppressing virus-induced apoptosis indirectly. Consistent with this model, Op-IAP3 has evolved an intrinsic stability that may serve to repress signal-induced turnover and autoubiquitination when bound to its targeted cellular IAP.

IMPORTANCE The IAPs were first discovered in baculoviruses because of their potency for preventing apoptosis. However, the antiapoptotic mechanism of viral IAPs in host insects has been elusive. We show here that the prototypical viral IAP, Op-IAP3, blocks apoptosis indirectly by associating with unstable, autoubiquitinating host IAP in such a way that cellular IAP levels and antiapoptotic activities are maintained. This mechanism explains Op-IAP3's requirement for native cellular IAP as a cofactor and the dispensability of caspase inhibition. Viral IAP-mediated preservation of the host IAP homolog capitalizes on normal IAP-IAP interactions and is likely the result of viral IAP evolution in which degron-mediated destabilization and ubiquitination potential have been reduced. This mechanism illustrates another novel means by which DNA viruses incorporate host death regulators that are modified for resistance to host regulatory controls for the purpose of suppressing host cell apoptosis and acquiring replication advantages.

INTRODUCTION

Apoptosis is an important defense against virus infection. This highly conserved self-destruct process is regulated by the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins, a family of critical survival factors that are also involved in development, mitosis, inflammation, and cancer (reviewed in references 1, 2, 3, and 4). Multiple insect DNA viruses, including the baculoviruses, entomopoxviruses, iridoviruses, nudiviruses, and asfarviruses, encode IAPs to inhibit virus replication-induced apoptosis and thereby expedite virus multiplication and dissemination (5, 6). Of these viruses, IAPs from the baculoviruses are the best characterized. Interestingly, despite their shared role of preventing apoptosis, the baculovirus IAPs appear mechanistically distinct from their closely related cellular homologs and are structurally dissimilar from other viral proteins that block apoptosis, including the P35 family of caspase inhibitors. As such, the viral IAPs are expected to reveal new insights into mechanisms of viral regulation of apoptosis.

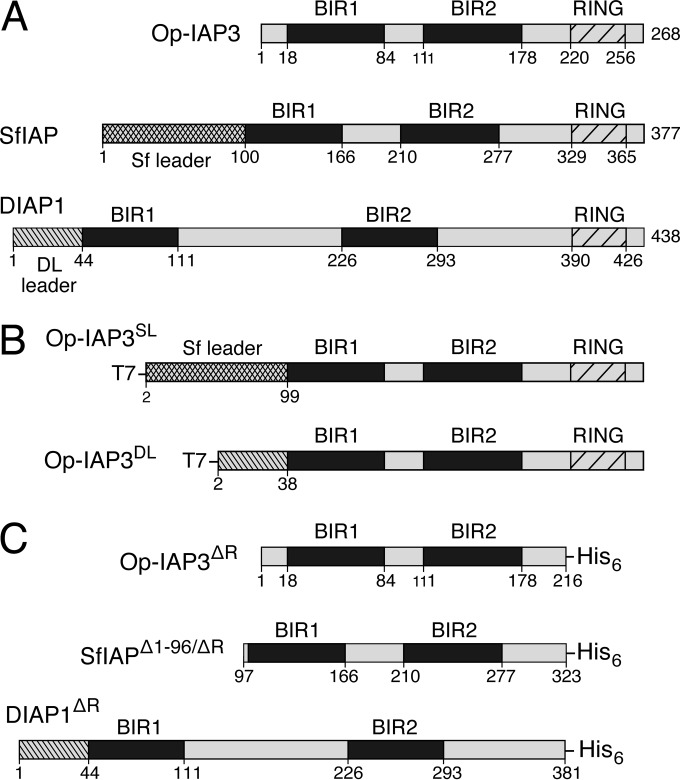

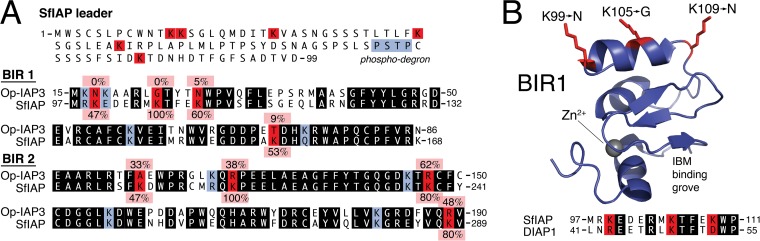

Op-IAP3 is the prototypical viral IAP (7). Encoded by the baculovirus Orgyia pseudotsugata multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (family Baculoviridae, genus Alphabaculovirus), this 268-residue modular protein is well conserved among the baculoviruses (reviewed in reference 5). Op-IAP3 possesses two baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domains, which are ∼70-residue zinc-binding modules, and a C-terminal E3 ubiquitin ligase RING domain (Fig. 1A). As such, Op-IAP3 closely resembles cellular SfIAP (8, 9) from the baculovirus-permissive moth Spodoptera frugiperda and DIAP1 (10) from the nonpermissive fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Fig. 1A). BIR1 and BIR2 are required for Op-IAP3's antiapoptotic activity (11–13), as are both BIRs of the related insect IAPs (8, 14, 15). The antiapoptotic activity of cellular IAPs derives from BIR-mediated interaction and neutralization of caspases, the prodeath proteases (reviewed in references 2, 16, 17, and 18). During apoptotic signaling, proapoptotic factors containing an IAP-binding motif (IBM) displace IAP-bound caspases, which then execute apoptosis (19). Despite its relatedness to cellular IAPs, Op-IAP3 fails to bind or inhibit any previously tested caspases (12, 14, 20, 21).

FIG 1.

Baculovirus and insect IAPs. (A) IAP organization. Baculovirus Op-IAP3 (268 residues), Spodoptera SfIAP (377 residues), and Drosophila DIAP1 (438 residues) each possess two baculoviral IAP repeats (BIRs) and an E3 ubiquitin ligase RING; residue numbers indicate domain boundaries. Cellular SfIAP and DIAP1 contain N-terminal leader domains (crosshatching and stripes) that negatively regulate IAP stability, whereas Op-IAP3 lacks a comparable instability motif (27). (B) Chimeric Op-IAP3s. The N-terminal 17 residues of Op-IAP3 were replaced with the corresponding 99 residues of SfIAP and 38 residues of DIAP1 to generate Op-IAP3SL and Op-IAP3DL, respectively. Unless otherwise stated, Op-IAP3 constructs possess an N-terminal T7 epitope tag, which does not alter function (27). (C) RING less IAPs. Due to insolubility when produced in E. coli, C-terminal residues that constitute the RING were deleted (ΔR) from Op-IAP3, SfIAP, and DIAP1 and replaced with a histidine (His6) tag. The N-terminal 96 leader residues were also removed from SfIAP, thereby improving stability (27).

In insects, including moths, butterflies, flies, and mosquitoes, loss or destruction of the principal IAP induces rapid caspase-mediated apoptosis (22–26). Thus, as expected for critical regulators of cell death, SfIAP and DIAP1 are highly responsive to host degradative signals (8, 21, 27–31). Consequently, factors that positively or negatively affect IAP levels modulate apoptosis, including that triggered by virus infection. In the case of SfIAP, a phospho-degron embedded within the N-terminal leader contributes to this turnover via proteosome-mediated degradation (27). The C-terminal RING also negatively regulates SfIAP stability, probably by autoubiquitination. The RING, as demonstrated by human XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2, is activated upon dimerization, leading to autoubiquitination or ubiquitination of BIR-bound ligands (reviewed in references 17, 32, and 33). Similarly, SfIAP and Op-IAP3 also exist as homodimeric complexes, which can be dominantly inhibited by various truncations of the same (8, 11).

Viral Op-IAP3, which lacks a degron-containing leader, is highly stable and resistant to signal-induced turnover (27). It inhibits apoptosis in baculovirus-infected Spodoptera cells, acting at a step upstream of initiator caspase activation (34–37). In mammalian cells, Op-IAP3 can block apoptosis by binding to the proapoptotic protein Smac, effectively interfering with Smac-mediated antagonism of XIAP to liberate caspases for apoptosis (20). Op-IAP3 can bind to Drosophila proapoptotic factors, including Hid, Grim, and Reaper, yet it fails to prevent apoptosis in Drosophila cells (12–14, 38–40). Thus, Op-IAP3 may use a mechanism other than neutralizing prodeath proteins in Lepidoptera.

In invertebrates, the steady-state level of cellular IAPs is regulated by diverse factors. During baculovirus infection, SfIAP is rapidly destroyed by the host's DNA damage response (DDR), which is triggered by viral DNA replication (26). This loss of SfIAP causes caspase-mediated apoptosis in the absence of viral suicide substrates from the P35 family, which otherwise covalently bind and inhibit caspases (reviewed in reference 6). In preliminary experiments, we noted that virus-induced depletion of SfIAP was mitigated by the presence of viral Op-IAP3, which correlated with apoptotic suppression. Thus, Op-IAP3 affects SfIAP self-degradation. We show here that Op-IAP3 extends the half-life of SfIAP through a mechanism that involves heterodimeric interaction. Furthermore, Op-IAP3 exhibits abrogated antiapoptotic activity by itself and instead requires SfIAP as a cofactor. We concluded that Op-IAP3 is a pseudocellular IAP that has lost normal degradative-response motifs and acts to stabilize cellular IAP through a novel mechanism requiring direct interaction. Thus, this baculovirus IAP has revealed an antiapoptotic strategy unique among known viral apoptosis suppressors and a new means to regulate critical functions of cellular IAPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and infections.

Spodoptera frugiperda IPLB-SF21 (41) and Drosophila melanogaster DL-1 (42) cells were maintained at 27°C in TC100 or Schneider's growth medium (Invitrogen), respectively, supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone). Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) recombinants wt/lacZ (p35+/iap−/polh− lacZ+), vΔp35/lacZ (p35−/iap−/polh− lacZ+), and vP35 (pIE1prm p35+/iap−/polh− lacZ+) were described previously (43, 44). vOpIAP (Op-iap3HA p35−/iap+/polh− lacZ+) isolates A and B possess Op-IAP3HA randomly inserted into the vΔp35/lacZ genome (35), whereas Op-IAP3HA was inserted at the polh locus under the control of the ie-1 promoter for isolates C and D (44). For infections, extracellular budded virus (BV) was added to monolayers at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU per cell. AcMNPV reporter assays used recombinant vΔp35/lacZ wherein lacZ is under the control of the polyhedrin promoter (8, 26, 27, 45). Intracellular β-galactosidase was measured 24 h after infection by using a Galacto-Light Plus β-galactosidase chemiluminescent assay (Tropix) and is reported as the average activities ± standard deviations obtained from triplicate assays.

Plasmids.

Transient gene expression was accomplished by using plasmid vector pIE1prm/hr5/PA (46), which possesses the constitutively active AcMNPV ie-1 promoter (prm) and hr5 enhancer. Plasmids pIE1prm/hr5/opiapHA/PA and pIE1prm/hr5/opiapT7/PA encode Op-IAP3 N-terminally tagged with hemagglutinin (HA) or T7 epitopes, respectively (11, 27, 35). Plasmids pIE1prm/hr5/opiap(Sflead)T7/PA and pIE1prm/hr5/opiap(DL)T7/PA encode T7-tagged Op-IAP3 chimeras (designated Op-IAP3SL and Op-IAP3DL), in which Op-IAP3 residues 1 to 17 were replaced with SfIAP leader residues 1 to 96 or DIAP1 leader residues 2 to 37, respectively (27). T7 epitope-tagged Op-IAP3 with the substitutions G154S, Q167R, and I223A were generated by standard PCR-based mutagenesis of pIE1prm/hr5/opiapT7/PA. HA-tagged Op-IAP3H4sub, in which residues 179 to 194 were replaced with codons encoding Gly-Ala-Gly-Gly-Ala, was generated by PCR-based mutagenesis of pIE1prm/hr5/opiapHA/PA (35). Plasmids pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapT7/PA and pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapHA/PA encode N-terminal T7- or HA-tagged SfIAP (8). pIE1prm/hr5/diap1T7/PA encoded N-terminal T7-tagged DIAP1 (27). Plasmids for protein expression in Escherichia coli for P49-His6, D94A-mutated P49-His6, P35-His6, and D87A-mutated P35-His6 have been previously described (47, 48). The expression plasmid pET22B-sfiap(Δ1-96/ΔRING)-His6 was generated by PCR amplification from the template pIE1prm/hr5/sfiapHA/PA (8) to generate an sfiap(Δ1-96/Δ324-377) fragment containing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites, which was used to replace the NdeI/XhoI fragment of pET22/Sfcasp1 (36). The pET22B-opiap(ΔRING) and pET22B-diap1(ΔRING) plasmids were generated in a similar manner. For transfections, SF21 monolayers were overlaid with medium containing purified plasmid DNA mixed with cationic liposomes as described previously (36). Plasmid transfection efficiencies were >80% (data not shown).

Recombinant proteins.

P49-His6, D94A-mutated P49-His6, P35-His6, D87A-mutated P35-His6, DIAP1(ΔRING)-His6, SfIAP(Δ1-96/ΔRING)-His6, and Op-IAP(ΔRING)-His6 were isolated from E. coli strain BL-21(DE3) by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (Qiagen) as described previously (47, 48). Eluted proteins were dialyzed into 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 10% glycerol. Protein purity was judged by SDS-PAGE and by Biosafe Coomassie blue (Bio-Rad) staining. Protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford assay using Bio-Rad protein assay reagent.

Immunoblots.

Proteins from cells lysed in 1% SDS and 1% β-mercaptoethanol (βME) were electrophoresed and transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore) or nitrocellulose (Osmonics, Inc.) membranes, which were incubated with the following antisera (diluted as indicated in parentheses): polyclonal anti-SfIAP (1:1,000), affinity purified as described in reference 8; polyclonal anti-Sf-caspase-1 (1:1,000) (36); monoclonal anti-actin (1:5,000; BD Biosciences); monoclonal anti-T7 (1:10,000; Novagen); polyclonal anti-IE1 (1:10,000) (49); polyclonal anti-DIAP1 (1:1,000) (23); polyclonal anti-DrICE, (1:1,000) (44); or polyclonal anti-His6DRONC (1:1,000) (23), which was used to detect the His6 tag. Signal development was conducted by using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) with the CDP-Star chemiluminescent detection system (Roche). Films were scanned at 300 dots per inch (dpi) and prepared using CS5 Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Protein half-life.

Cells transfected 24 h earlier with pIE1 prm-based vectors were overlaid with medium containing 400 μg of cycloheximide (CHX; Sigma) per ml, which was the minimum concentration sufficient to block 95% of SfIAP synthesis over a 4-h period (27). Immunoblots of serial dilutions of cell lysates prepared at the indicated times thereafter were quantified by densitometry (NIH ImageJ) using films exposed within the linear range. The percent protein remaining at each interval was calculated relative to actin and plotted as a function of time to obtain protein half-lives (t1/2) by using first-order decay best-fit analysis. The half-lives from at least three independent experiments were averaged, and these averages are reported with the standard deviations. P values were calculated by the heteroscedastic one-tailed Student t test.

Immunoprecipitations.

Cells transfected 24 h earlier with plasmids expressing T7-tagged proteins were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40 substitute [Fluka], 1× complete protease inhibitor [Roche]). Proteins were bound to anti-T7-conjugated agarose beads (Novagen) in IP buffer. The beads were washed with IP buffer, and proteins were eluted by boiling and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Caspase assays and pulldowns.

To prepare cell extracts, SF21 or DL-1 cells were collected by centrifugation, suspended in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 1× complete protease inhibitor (Roche), lysed by Dounce homogenization, and clarified by centrifugation as described previously (26, 44). The extracts were used immediately (preactivation) or incubated for 6 to 16 h at 27°C (postactivation) to activate Sf-caspase-1 or DrICE, respectively (26, 44). The extracts were then mixed for 45 min with the indicated His6-tagged proteins and assayed for residual caspase activity by using the substrate N-actyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (DEVD-amc) (Sigma). Values are reported as the average rates ± standard deviations of fluorescent product accumulation in relative light units (RLU) for triplicate samples. For Ni2+ affinity pulldowns, the same cell extracts (postactivation) were mixed with the indicated His6-tagged proteins in excess for 2 h at 27°C followed by binding to Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose beads (Qiagen). The beads were washed with 45 mM imidazole in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.9), 500 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. Bound proteins were eluted with 400 mM imidazole in the same buffer and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

RNA interference (RNAi).

Single-stranded RNA specific to egfp or the first 287 coding bases of the SfIAP gene (GenBank AX213188) sequence encoding the N-terminal leader of SfIAP was synthesized by using in vitro transcription reactions (Ampliscribe T3 and T7 kits; Epicentre) with linearized pBluescript K/S(+) plasmids as a template as previously described (26, 50). Complementary RNAs were heated to 65°C and cooled 1°C per min to generate double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). SF21 cells were transfected in suspension with DNA plasmids and 24 h later were transfected with a dsRNA-cationic liposome mix as described previously (50). RNA transfection efficiency was >95% (data not shown).

Protein sequence alignments and modeling.

Sequences of 21 viral IAPs and 15 cellular IAPs with alignment scores of >245 and E values of <4.40 × 10−25 were identified by a UniProt blastp search (51) using BIR1 sequences of Op-IAP3 or SfIAP, respectively. The resulting data sets were used to calculate the percentage of lysine residues at conserved positions within BIR1 and BIR2 after ClustalW alignment using the MEGA6.06 program (52). As determined by an NCBI blastp search of the RCSB Protein Data Bank, SfIAP's BIR1 (residues 97 to 167) is most closely related (44% identity, 63% similarity) to BIR1 (residues 41 to 112) of Drosophila DIAP1 (PDB 3SIP) from DIAP1 (53). Using PyMol (54), DIAP1 BIR1 residues 41 to 112 were modeled such that R43 and D53 were replaced with the corresponding SfIAP residues K99 and K109, respectively.

RESULTS

Baculoviral Op-IAP3 attenuates loss of host IAP during infection.

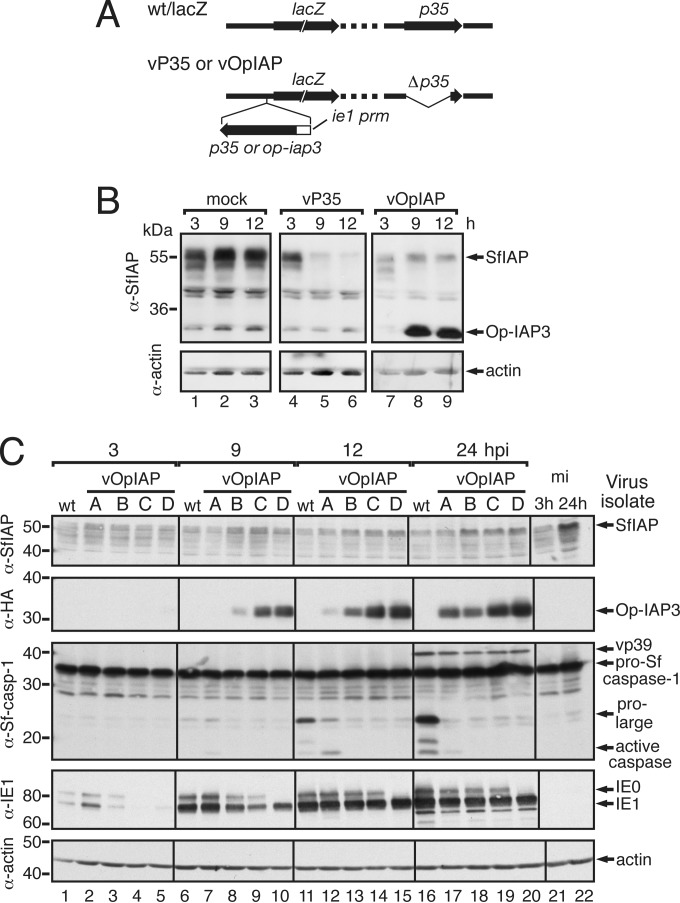

Upon AcMNPV infection, the principal antiapoptotic IAP (SfIAP) of the permissive host Spodoptera frugiperda is depleted rapidly, thereby causing apoptosis if not blocked by a virus-encoded suppressor (26). In preliminary studies that monitored the fate of SfIAP during infection, we observed that depletion of the cellular IAP was reduced when viral Op-IAP3, but not caspase inhibitor P35, was expressed (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 7 to 9 with lanes 4 to 6) from recombinants vOpIAP and vP35, respectively (Fig. 2A). This finding suggested that Op-IAP3 affects the loss of host cell SfIAP. To investigate this possibility, we compared a panel of Op-iap3+/p35− AcMNPV recombinants (Fig. 2A) that produced increasing levels of Op-IAP3. Immunoblot analysis indicated that endogenous SfIAP late in infection increased proportionally with Op-IAP3 (Fig. 2C). For example, virus isolate D produced the highest level of Op-IAP3 and maintained higher levels of endogenous SfIAP, whereas isolate A produced less Op-IAP3 and exhibited a significant reduction in SfIAP. As Op-IAP3 expression and SfIAP levels increased, the proteolytic activation of Sf-caspase-1 decreased (Fig. 2C). This caspase is the principal effector caspase of Spodoptera (36, 55). We concluded that viral IAP directly or indirectly stabilizes cellular IAP during infection.

FIG 2.

Stabilization of host SfIAP during infection. (A) AcMNPV recombinants. wt/lacZ possesses a lacZ reporter under the control of the polyhedrin promoter in place of the polyhedrin (polh) gene. vP35 and vOpIAP lack native p35 (Δp35) but have p35 or op-iap3, respectively, inserted under the control of the ie-1 promoter adjacent to lacZ (isolates C and D) or randomly into the genome (isolates A and B) (43, 44). (B) Virus-induced SfIAP depletion. Lysates of SF21 cells harvested at the indicated time (hours) after mock infection (mock) or infection with AcMNPV vP35 or vOpIAP (MOI, 10) were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP (top). Because of sequence similarities, anti-SfIAP also recognizes Op-IAP3. Protein levels were verified by using anti-actin (bottom). Protein molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are on the left. (C) Op-IAP3's effects on virus-induced SfIAP depletion. Lysates harvested at the indicated times (hours postinfection [hpi]) after mock infection (mi) or infection with AcMNPV wt/lacZ (wt) or vOpIAP isolates A, B, C, or D (MOI, 10) were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-SfIAP, anti-HA for Op-IAP3, anti-Sf-caspase-1, anti-IE1, or anti-actin. The presence of early protein IE1 was used to verify comparable levels of infection. Pro-Sf-caspase-1 and its active large subunits are indicated; AcMNPV vp39 cross-reacts with anti-Sf-caspase-1 (36).

Viral Op-IAP3 increases cellular SfIAP stability.

To assess the effect of Op-IAP3 on the relative stability of SfIAP, we used a sensitive half-life assay for proteins in native, nonapoptotic SF21 cells (8, 27). After transfection with plasmids encoding differentially epitope-tagged SfIAP and Op-IAP3, cells were treated with cycloheximide at a concentration sufficient to block >95% of SfIAP synthesis, and lysates prepared at intervals thereafter were subjected to immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3A). The most obvious effect of Op-IAP3 was increased steady-state levels of SfIAP. Consistent with increased stability, Op-IAP3 extended the half-life of SfIAP 3-fold (P < 0.01), from 43 (±15) min to 143 (±7) min (Fig. 3B). Op-IAP3 itself was long-lived relative to SfIAP, with a half-life of 220 (±75) min. Op-IAP3-mediated stabilization of SfIAP was dose dependent, as both the steady-state level and stability of SfIAP increased in proportion to the ratio of Op-IAP3 to SfIAP (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Op-IAP3 stabilization of SfIAP. (A) SfIAP turnover. SF21 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-SfIAP alone or with T7-Op-IAP3 and treated 24 h later with cycloheximide, which reduces protein synthesis by >95% (27). Lysates prepared at the indicated times thereafter were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-T7 and anti-HA. (B) IAP half-lives. Lysates from cells transfected with plasmids encoding SfIAP (Sf), Op-IAP3 (Op), chimeric Op-IAP3SL (OpSL) with the SfIAP leader, or chimeric Op-IAP3DL (OpDL) with the DIAP1 leader were subjected to turnover assays as described for panel A. Half-lives were calculated from three or more independent experiments by using best-fit first-order decay analyses on immunoblots and are reported as the average values (minutes) ± standard deviations. The measured half-life (bar) is listed on top, and the coexpressed IAP is listed below. (C) Dose effect of Op-IAP3 on SfIAP stability. SF21 cells were transfected with HA-SfIAP-encoding plasmid (1 μg) and increasing levels of T7-Op-IAP3 plasmid to give the indicated ratios; in all cases, empty vector was used to normalize total plasmid. After 24 h, lysates from cycloheximide-treated cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described for panel A. (D) Effects of Op-IAP3 during stress. SF21 cells transfected with plasmid ratios as described for panel C were transferred into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after 24 h. Lysates prepared at the indicated times (hours) thereafter were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described for panel A.

To determine whether the inherent stability of viral Op-IAP3 accounted for its effect on increasing SfIAP longevity, we tested chimeras of Op-IAP3 that were engineered for reduced stability. To this end, we used Op-IAP3 fused to the degron-containing leaders of SfIAP (Op-IAP3SL) or Drosophila DIAP1 (Op-IAP3DL) (Fig. 1B), both of which cause rapid turnover (27). As expected, Op-IAP3DL and Op-IAP3SL exhibited shortened half-lives of 19 (±6) min and 23 (±10) min, respectively, when expressed alone in transfected SF21 cells (Fig. 3B). Moreover, unlike wild-type Op-IAP3, neither Op-IAP3DL nor Op-IAP3SL significantly affected the stability of coexpressed SfIAP (Fig. 3B). Thus, unstable mutations of Op-IAP3 failed to stabilize SfIAP in this assay. We concluded that the relative stability of Op-IAP3 is a principal determinant of SfIAP stability.

Viral Op-IAP3 stabilizes SfIAP under conditions of stress.

When SF21 cells are subjected to stress, such as nutrient deprivation, intracellular SfIAP is rapidly degraded through the activity of its leader-embedded phospho-degron (27). We therefore tested the capacity of Op-IAP3 to affect stress-induced turnover of SfIAP. To trigger the stress response, SF21 cells transfected 24 h previously with plasmid encoding HA-tagged SfIAP plus increasing levels of plasmid encoding T7-tagged Op-IAP3 were transferred into serum-free, isotonic phosphate-buffered saline (27). Whereas SfIAP was rapidly degraded when transfected alone (Fig. 3D, lanes 1 to 5), it was stabilized by Op-IAP3 in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 3D, lanes 6 to 25). Both the steady-state level and the relative stability of SfIAP increased as the level of coexpressed Op-IAP3 was increased. We concluded that viral Op-IAP3 stabilizes cellular SfIAP under multiple conditions, including stress, normal growth, and virus infection.

Op-IAP3 interacts with SfIAP.

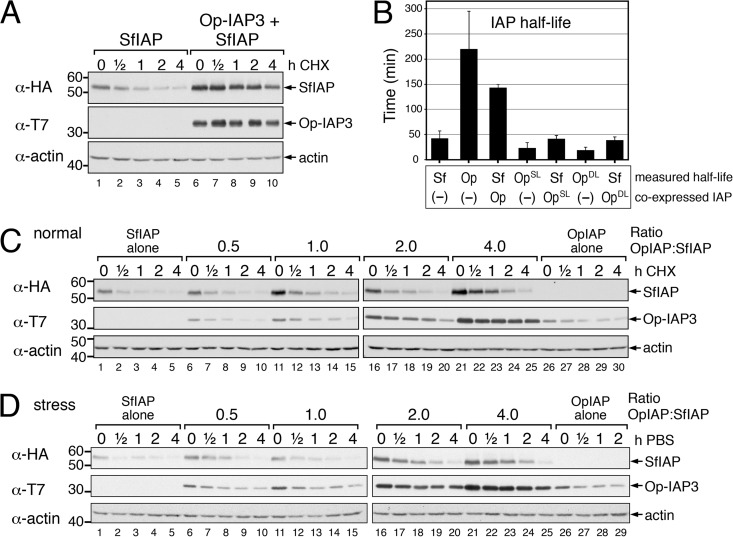

Our previous studies indicated that Op-IAP3 forms homodimers, as does SfIAP (8). Because of their high level of sequence similarity, we hypothesized that Op-IAP3 and SfIAP also interact as heterodimers. We conducted immunoprecipitation assays using extracts from SF21 cells transfected with plasmids encoding differentially tagged IAPs to test this possibility. Upon immunoprecipitation, T7-tagged Op-IAP3 readily associated with HA-tagged SfIAP (Fig. 4A, lane 5), whereas HA-tagged SfIAP exhibited little nonspecific precipitation (lane 6). Op-IAP3 also interacted with endogenous SfIAP as indicated by using SfIAP-specific antiserum (Fig. 4B, lane 5). The association between Op-IAP3 and SfIAP was confirmed by reciprocal immunoprecipitations (Fig. 4C, lane 12). We concluded that Op-IAP3 and SfIAP form a stable complex.

FIG 4.

Op-IAP3 interactions. (A) IAP immunoprecipitations. SF21 cells were transfected with (+) plasmid encoding the indicated T7- or HA-tagged proteins, and cell extracts were prepared 24 h later. Proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) by using anti-T7 beads and subjected to immunoblot analysis (lanes 5 to 8) by using anti-T7 or anti-HA serum. Lysates prior to immunoprecipitation were included (lanes 1 to 4). (B) Op-IAP3 association with endogenous (endog) SfIAP. SF21 cells transfected 24 h earlier with the indicated plasmids or empty vector were lysed and subjected to anti-T7 immunoprecipitation as described for panel A. Immunoblot analysis was conducted by using anti-SfIAP, which also recognizes Op-IAP3. (C) Interactions of chimeric Op-IAP3. Proteins from lysates prepared from cells transfected (+) with the indicated plasmids were immunoprecipitated with anti-T7 beads as described for panel A and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-T7 or anti-HA (lanes 9 to 16). Lysates prior to immunoprecipitation were included (lanes 1 to 8). (D) Sf-caspase-1 activation by chimeric Op-IAP3DL. SF21 cells transfected with plasmid encoding T7-Op-IAP3DL or β-galactosidase (control) were lysed at the indicated times (hours) after transfection and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-Sf-caspase-1, anti-T7, or anti-actin.

To determine whether Op-IAP3 interacts with other insect IAPs, we tested DIAP1 (Fig. 1A), the principal Drosophila cellular IAP, which is also depleted upon baculovirus infection (27). When coproduced in plasmid-transfected SF21 cells, only limited interaction between Op-IAP3 and DIAP1 was detected (Fig. 4A, lane 8), despite the abundance of both proteins (lane 4). When coproduced in SF21 cells, SfIAP formed a stronger association with DIAP1 than did Op-IAP3 (Fig. 4A, lane 7). These findings correlate IAP heterointeraction with function, as SfIAP suppresses apoptosis in Drosophila cells but Op-IAP3 does not (8, 12, 37, 44). We concluded that Op-IAP3 interacts selectively with invertebrate IAPs, the mechanism of which remains to be resolved (see below).

Short-lived chimeric Op-IAP3 sensitizes cells to apoptosis.

We further investigated the biochemical properties of the short-lived Op-IAP3SL and Op-IAP3DL chimeras by performing immunoprecipitation assays to assess IAP associations. Despite their lower abundance, both Op-IAP3SL and Op-IAP3DL interacted with SfIAP (Fig. 4C, lanes 13 and 15). Furthermore, both chimeras associated with wild-type Op-IAP3 in transfected cells (Fig. 4C, lanes 14 and 16), confirming the homodimeric nature of Op-IAP3 (11). We also used a more sensitive assay to measure the effects of chimeric Op-IAP3DL on endogenous SfIAP. To this end, we monitored the activation of effector caspase Sf-caspase-1, which is normally restrained by SfIAP and therefore is a biological readout for SfIAP activity (8, 26). Upon transfection of plasmid encoding Op-IAP3DL, pro-Sf-caspase-1 was proteolytically processed to its active subunits (Fig. 4D, lanes 1 to 5). Op-IAP3DL-producing cells also underwent apoptotic blebbing (data not shown). In contrast, plasmid carrying control lacZ failed to trigger caspase activation (Fig. 4D, lanes 6 to 10) or apoptotic blebbing. Consistent with the failure to stabilize SfIAP, neither Op-IAP3DL nor Op-IAP3SL prevented caspase activation or apoptosis when expressed in AcMNPV-infected SF21 cells (data not shown). Collectively, these findings suggest that the short-lived Op-IAP3 chimeras interact with SfIAP and destabilize it, thereby triggering apoptosis. Thus, depending on relative stability or instability, Op-IAP3 or mutations thereof can act as anti- or proapoptotic agents, respectively, through a mechanism that requires direct interaction with the cellular IAP.

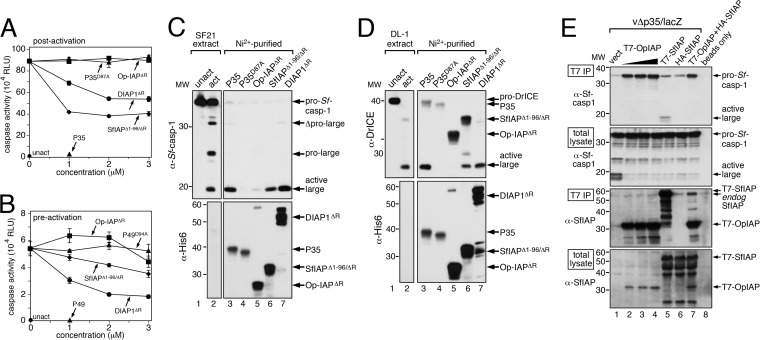

Op-IAP3 fails to inhibit or bind native Spodoptera caspases.

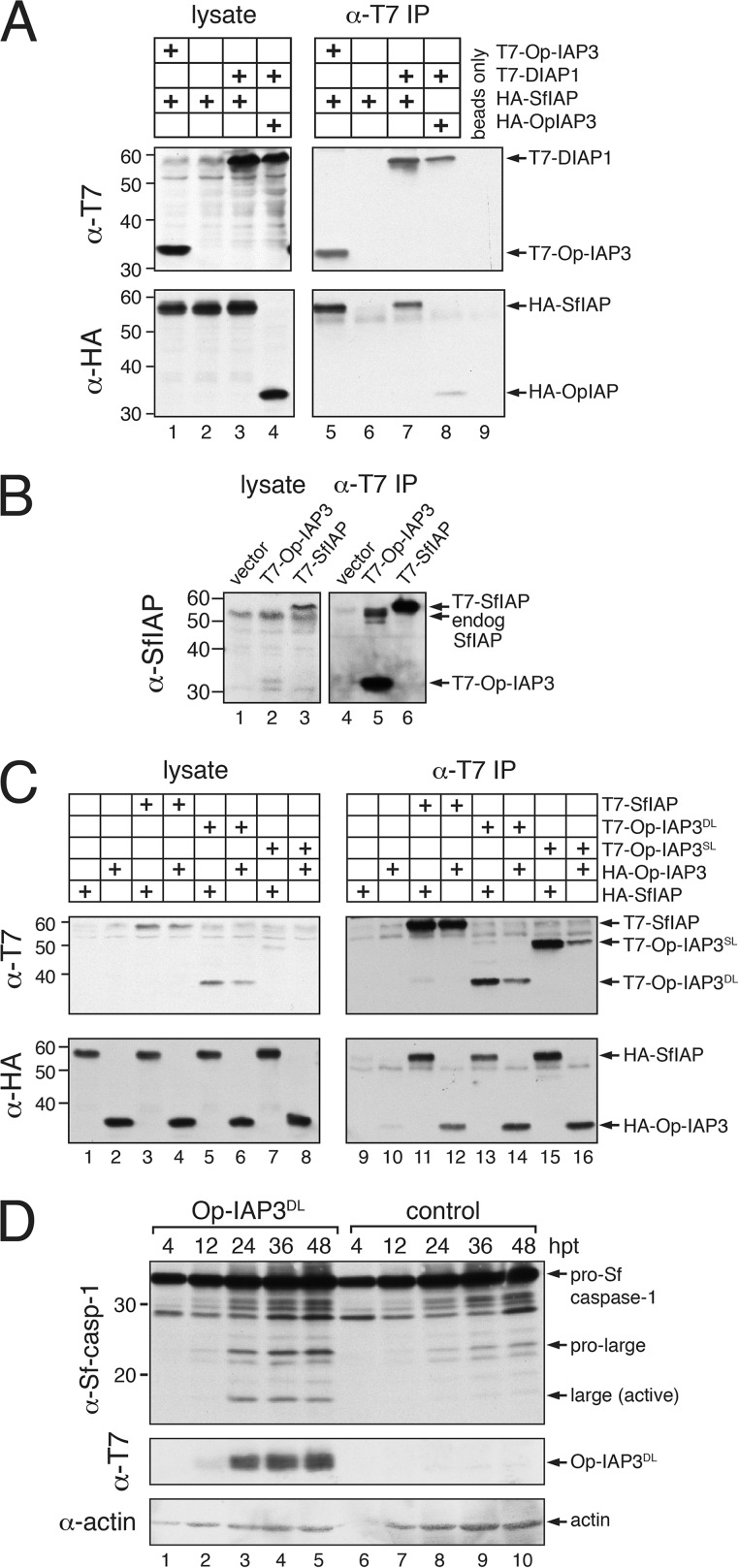

Previous studies showed that unlike cellular IAPs, Op-IAP3 fails to inhibit caspases from mammalian and Drosophila origins (12, 14, 20, 21). Thus, we tested Op-IAP3's effects on Spodoptera caspases, which are activated upon baculovirus-induced depletion of SfIAP. We first used a cell-free system derived from SF21 cells (26). Incubation of Spodoptera extracts causes spontaneous loss of SfIAP and triggers caspase activity (including Sf-caspase-1), which can be inhibited by the caspase inhibitor P35 but not by loss-of-function D87A-mutated P35 (Fig. 5A). When added to preactivated extracts, both SfIAP and DIAP1 reduced caspase activity by 50%. In contrast, Op-IAP3 failed to affect caspase activity (Fig. 5A). For each IAP tested (Fig. 1C), purified RINGless versions were used, as Op-IAP3 with its RING is insoluble when produced in E. coli. To test whether the IAPs could prevent caspase activation, recombinant proteins were added to the cell extracts prior to incubation. Only the baculovirus caspase inhibitor P49 blocked caspase activation (Fig. 5B), most likely by direct inhibition of the Spodoptera initiator caspase Sf-DRONC (37, 56). In contrast, Op-IAP3 had no effect on caspase activation (Fig. 5B), suggesting that it fails to inhibit initiator Sf-DRONC. Both SfIAP and DIAP1 exhibited partial inhibition, consistent with their anti-initiator caspase activities as cellular IAPs.

FIG 5.

IAP interactions. (A) Postactivation caspase inhibition. Cytosolic extract from Spodoptera SF21 cells was incubated at 27°C to activate endogenous caspases (26). The indicated C-terminal His6-tagged recombinant proteins [P35, D87A-mutated P35, P49, D94A-mutated P49, or RING less (ΔR) Op-IAP3, SfIAP(Δ1-96), or DIAP1] were added and incubated for 45 min, and samples were assayed for caspase activity by using Ac-DEVD-amc as a substrate. Relative light unit (RLU) values represent the average rates ± standard deviations of caspase activity for triplicate samples. (B) Preactivation caspase inhibition. Unactivated (unact) SF21 cytosolic extract was mixed with the indicated recombinant proteins, incubated for 8 h at 27°C, and assayed for caspase activity as described for panel A. (C) Sf-caspase-1 pulldown. SF21 extract was activated (act) as described for panel A, mixed with the indicated recombinant proteins in excess, and subjected to Ni2+ affinity chromatography. The resulting complexes were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-Sf-caspase-1 (top) or a His6-specific antiserum (bottom). Protein molecular size standards (in kilodaltons) are on the left. (D) DrICE pulldown. Activated (act) DL-1 cytosolic extract (44) containing active DrICE was mixed with the indicated recombinant proteins and subjected to Ni2+ affinity chromatography and immunoblot analysis by using anti-DrICE (top) or anti-His6 (bottom); both antisera detect the His6 tag. (E) Immunoprecipitations. SF21 cells transfected 24 h previously with plasmids encoding the indicated T7- or HA-tagged IAPs were infected with vΔp35/lacZ. Proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cytosolic extracts prepared 24 h later by using anti-T7 beads and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-Sf-caspase-1 or anti-SfIAP. Lysates prior to immunoprecipitation were included (total lysate).

We next verified that cellular SfIAP and DIAP1 inhibited the cell-free caspase activity by direct caspase binding. Ni2+-affinity pulldown assays using the His6-tagged versions of each protein (Fig. 1C) indicated that P35, SfIAP, and DIAP1 interacted with active Sf-caspase-1, as judged by the presence of Sf-caspase-1's large subunit in the pulldown (Fig. 5C, lanes 3, 6, and 7). In contrast, Op-IAP3 and D87A-mutated P35 exhibited little or no interaction with active Sf-caspase-1 (lanes 4 and 5). In an analogous cell-free system derived from Drosophila DL-1 cells in which effector caspase DrICE is spontaneously activated (44), SfIAP, DIAP1, and P35 interacted stably with active DrICE, whereas Op-IAP3 and D87A-mutated P35 did not (Fig. 5D). Thus, in two genera of invertebrates (Spodoptera and Drosophila) in which AcMNPV triggers caspase activation, we found no evidence for direct interaction between Op-IAP3 and the effector caspases Sf-caspase-1 and DrICE. Although this approach did not exclude the possibility that the RING is essential for in vitro anticaspase activity of Op-IAP3, these findings indicate that viral Op-IAP3 inhibits invertebrate apoptosis by a distinct mechanism.

We expanded the search for Op-IAP3-caspase interactions by using full-length, RING-containing IAPs in immunoprecipitations of infected cells. P35-deficient vΔp35/lacZ causes Sf-caspase-1 activation (Fig. 5E, lane 1). When introduced prior to infection, full-length T7-tagged SfIAP immunoprecipitated with virus-activated endogenous Sf-caspase-1 (lane 5). No active Sf-caspase-1 immunoprecipitated with T7-tagged Op-IAP3 despite its abundance (lanes 2 to 4). Rather, endogenous SfIAP immunoprecipitated with T7-tagged Op-IAP3 (lanes 2 to 4). Interestingly, the uncleaved proform of Sf-caspase-1 was immunoprecipitated by Op-IAP3 (Fig. 5E, lanes 2 to 4) but not by SfIAP (lane 5). Although an association between pro-Sf-caspase-1 and Op-IAP3 was not detected in cell extracts (Fig. 5C), it is possible that Op-IAP3 is recruited to a pro-Sf-caspase-1-containing complex, like the apoptosome.

Prodeath Smac and Hid binding sites are not required for Op-IAP3 antiapoptotic activity.

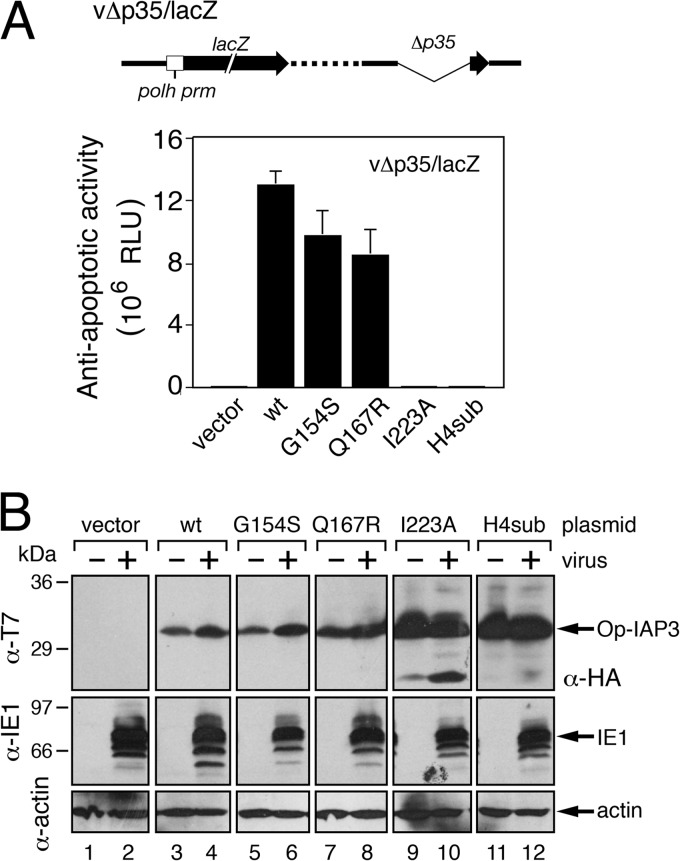

Op-IAP3 can prevent apoptosis in mammalian cells by binding and sequestering Smac, a central antagonist of XIAP (20). Smac contains an N-terminal IAP-binding motif (IBM) that interacts with the IAP BIR and displaces bound caspases to cause apoptosis (17, 19, 33). Smac, as well as IBM-containing Drosophila Hid, interacts with discrete residues at the surface of Op-IAP3 BIR2 (20, 40). To determine if Op-IAP3 binds and thereby sequesters IBM-containing proapoptotic factors as a means to preserve SfIAP activity, we tested the effect of modifying the IBM-binding grove by substitution of BIR residues. To this end, Op-IAP3 plasmid-transfected SF21 cells were infected with apoptosis-inducing recombinant virus vΔp35/lacZ (Fig. 6A). This caspase inhibitor-deficient virus has a very late polyhedrin promoter-directed lacZ reporter gene, which is active only when apoptosis is suppressed; thus, the reporter provides a sensitive measure of Op-IAP3 antiapoptotic activity (8, 11, 43). Whereas BIR2 mutations Q167R and G154S caused loss of Smac and Hid binding, respectively (20, 40), they had a minimal effect on Op-IAP3's capacity to block vΔp35/lacZ-induced apoptosis, as judged by lacZ reporter activity (Fig. 6A). As negative controls, loss-of-function Op-IAP3 mutations I223A and H4sub failed to prevent apoptosis as indicated by little or no lacZ expression. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that each Op-IAP3 construct was produced at comparable levels (Fig. 6B). These findings suggested that Op-IAP3 does not inhibit virus-induced apoptosis by sequestering Smac or Hid-like prodeath factors.

FIG 6.

Smac- and HID-binding mutations of Op-IAP3. (A) Viral lacZ reporter assays. SF21 monolayers were transfected with vector alone or pIE1 promoter plasmids encoding T7-Op-IAP3 (wt), T7-Op-IAP3(G154S), T7-Op-IAP3(Q167R), T7-Op-IAP3(I223A), or HA-tagged Op-IAP3H4sub and inoculated 24 h later with P35-deficient recombinant virus vΔp35/lacZ; expression of the late polyhedrin promoter-controlled lacZ reporter of vΔp35/lacZ (top) occurs only upon apoptotic suppression and thus is directly proportional to the antiapoptotic activity of plasmid-expressed Op-IAP3. Values shown are the average relative light units (RLU) of β-galactosidase assays of cell lysates prepared at 48 h after infection and represent the average values ± standard deviations obtained from triplicate infections. (B) Immunoblots. Cells treated as described for panel A were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-T7 or anti-HA (top), anti-IE1 (middle), or anti-actin (bottom). Protein size standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated.

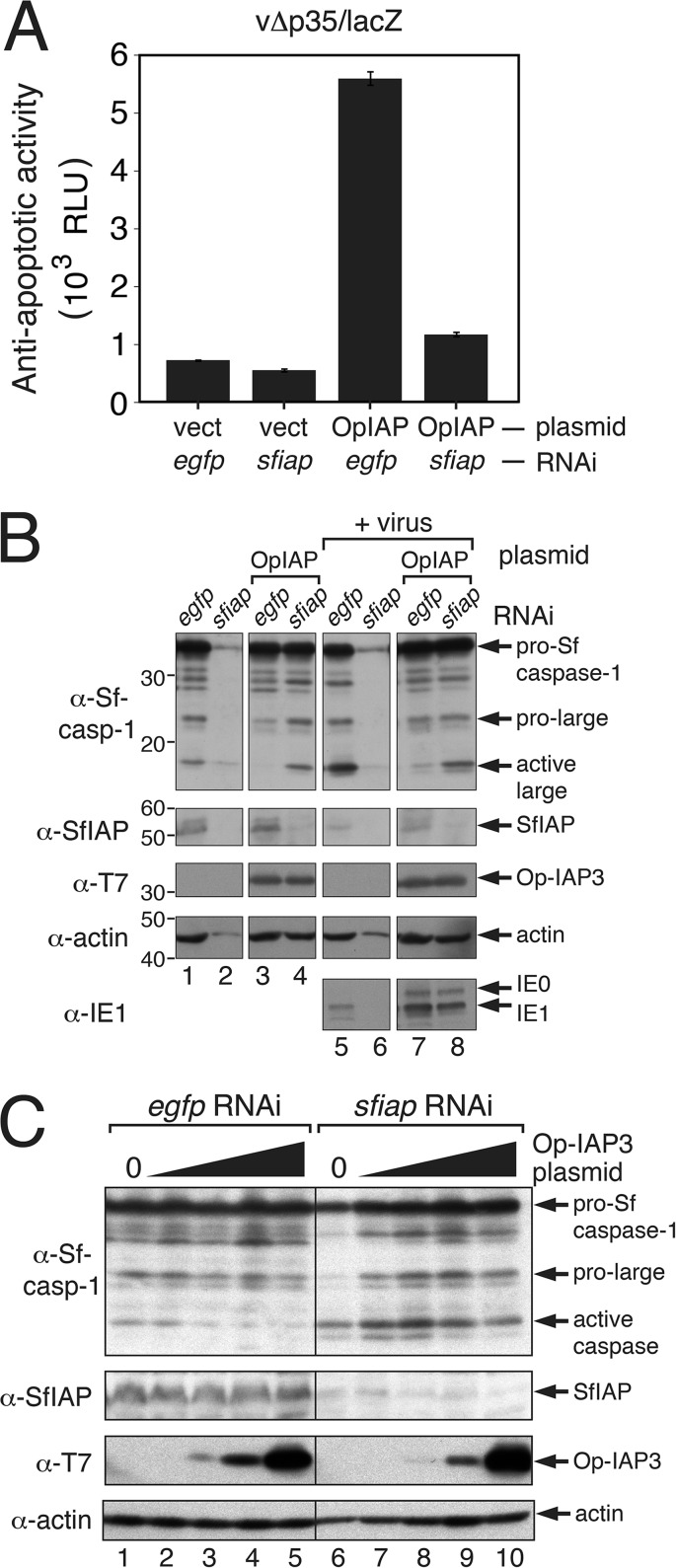

Op-IAP3 requires SfIAP as a cofactor.

Because Op-IAP3 selectively interacts with SfIAP, but not caspases, we hypothesized that Op-IAP3's antiapoptotic function is accomplished through its cellular-binding partner, SfIAP. As such, Op-IAP3 was predicted to have little or no activity in the absence of SfIAP. We tested this possibility by measuring Op-IAP3's capacity to block apoptosis after selective ablation of endogenous SfIAP by using RNA interference (RNAi). To this end, we treated SF21 cells with dsRNA complementary to the unique N-terminal leader of SfIAP, which did not affect Op-IAP3 levels. To quantify apoptosis in RNA-silenced cells, we used polh promoter-directed lacZ reporter activity obtained by infection with AcMNPV vΔp35/lacZ (see above). After plasmid transfection, followed by dsRNA transfection, Op-IAP3 significantly increased viral lacZ expression compared to vector-transfected cells treated with egfp-specific RNA (Fig. 7A). In contrast, Op-IAP3 failed to sustain lacZ expression upon treatment with sfiap-specific RNA; β-galactosidase levels were comparable to those of vector-transfected cells silenced for egfp or sfiap (Fig. 7A). RNAi specific for sfiap effectively ablated SfIAP (Fig. 7B, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). In SfIAP's absence, Op-IAP3 also failed to block viral activation of Sf-caspase-1, as indicated by the appearance of its active large subunit (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 and 8). However, in the presence of both Op-IAP3 and SfIAP, Sf-caspase-1 activation was significantly reduced; the minor level of Sf-caspase-1 activation in these cells (lanes 3 and 7) was due to the less-than-100% transfection efficiency with Op-IAP3-encoding plasmid. We concluded that Op-IAP3 has a greatly diminished capacity to suppress virus-induced apoptosis in the absence of endogenous SfIAP.

FIG 7.

Op-IAP3 and SfIAP synergism. (A) Op-IAP3 activity in infected cells upon SfIAP ablation. SF21 cells were transfected with empty vector or pIE1-promoter plasmids encoding T7-Op-IAP3 and treated 24 h later with egfp- or sfiap-specific dsRNA. After 24 h, the cells were inoculated with vΔp35/lacZ. Lysates prepared after an additional 24 h were assayed for β-galactosidase; values shown are the average RLU ± standard deviations obtained from triplicate β-galactosidase assays. (B) Immunoblots. SF21 cells transfected with plasmid and dsRNA as described for panel A were mock infected (lanes 1 to 4) or inoculated (+ virus) with vΔp35/lacZ (lanes 5 to 8) 24 h after dsRNA transfection. Lysates prepared after an additional 24 h were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-Sf-caspase-1, anti-SfIAP, anti-T7, anti-actin, and anti-IE1 (top to bottom). The presence of the AcMNPV IE1 transactivator confirmed infection. (C) Sf-caspase-1 activation in the presence of increasing Op-IAP3. SF21 cells transfected 24 h previously with a range of plasmid encoding T7-Op-IAP3 (0.01 μg to 2 μg per 106 cells) were transfected with egfp- (control) or sfiap-specific dsRNA. Lysates prepared 48 h later were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-Sf-caspase-1, anti-SfIAP, anti-T7, and anti-actin. The presence of the large Sf-caspase-1 subunit (active caspase) indicates caspase activity.

To confirm these findings, we tested Op-IAP3's capacity to prevent apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in uninfected SF21 cells that lacked SfIAP, as RNAi-mediated depletion of endogenous SfIAP causes rapid apoptosis (22, 26). Cells previously transfected with Op-IAP3-encoding plasmid were treated with sfiap-specific dsRNA and monitored for Sf-caspase-1 activation as an indicator of apoptosis. Even with increasing levels of T7-tagged Op-IAP3 (Fig. 7C, lanes 6 to 10), Sf-caspase-1 activation was robust in sfiap-silenced cells; ∼50% of these cells underwent apoptosis, as judged by apoptotic blebbing (data not shown). In contrast, caspase activation was minimal in cells treated with control egfp-specific RNA, which had no effect on SfIAP levels (Fig. 7C, lanes 1 to 5). We concluded that Op-IAP3 fails to block apoptosis in the absence of native SfIAP. Thus, SfIAP acts as a requisite cofactor for Op-IAP3.

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis is a potent antiviral defense. Not surprisingly, viruses that are susceptible to apoptosis have evolved mechanisms to usurp execution of apoptosis. A classic example is the DNA baculoviruses, which pirated host cell IAPs and modified them to block virus-induced apoptosis and thereby enhance multiplication. We report here that baculovirus Op-IAP3 functions by a newly recognized mechanism whereby it stabilizes and preserves the antiapoptotic activity of its closely related host cell IAP. By itself, Op-IAP3 has limited antiapoptotic activity in insect cells. However, by a strategy that involves direct binding, Op-IAP3 extends the life span and activity of host Spodoptera SfIAP by protecting it from death signal-induced depletion. This conferred stabilization is due to multiple evolutionary modifications to viral IAP, including the loss of degron-mediated degradation and a paucity of potential ubiquitination sites. Viral IAPs have thus provided further mechanistic insight into regulation of apoptosis during infection.

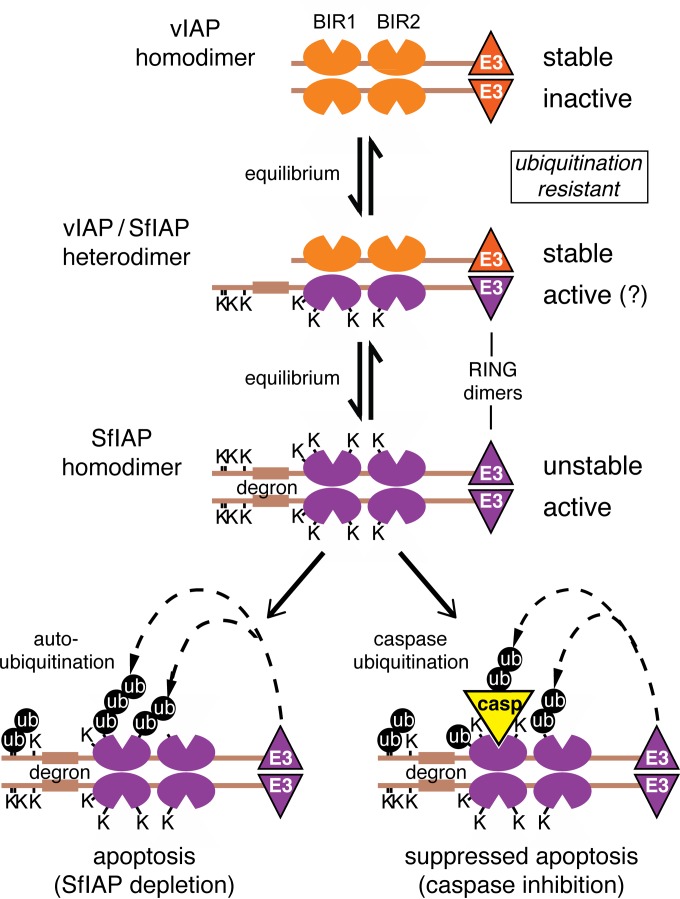

Model for Op-IAP3 antiapoptotic activity.

On the basis of our findings, Op-IAP3 suppresses apoptosis in baculovirus-permissive insects (order Lepidoptera) by enhancing the stability and thus functionality of the host cell IAP (Fig. 8). This novel mechanism capitalizes on Op-IAP3's distinct properties, which include its capacity to associate with its cellular IAP partner (Spodoptera SfIAP), its intrinsic stability, and its resistance to signal-induced degradation (see below). By itself, Op-IAP3 is inactive and requires host cell SfIAP as a cofactor to prevent apoptosis. By associating with SfIAP, most likely in the same way that Op-IAP3 and SfIAP form homodimers (8, 11), Op-IAP3 stabilizes SfIAP and protects it from signal-induced degradative pathways, including that of autoubiquitination. This stabilization preserves the pool of active SfIAP, thereby extending its anticaspase activity and the intracellular antiapoptotic state for which it is responsible. Increasing the pool of SfIAP is sufficient to prevent virus-induced apoptosis (26). Our model (Fig. 8) suggests that during infection, the increasing abundance of viral Op-IAP3 drives the equilibrium in favor of the heterodimeric viral/host IAP (Op-IAP3/SfIAP) complex. As active homodimeric SfIAP is lost to autoubiquitination, degron-mediated degradation, or caspase-binding mediated ubiquitination, additional SfIAP dissociates from the heterodimeric complex, thereby maintaining cellular IAP activities. Heterodimeric Op-IAP3/SfIAP may also provide IAP functions (see below).

FIG 8.

Model for Op-IAP3 antiapoptotic activity. Viral Op-IAP3, with its two BIRs and E3 ligase-containing RING domain, suppresses apoptosis indirectly by preserving the function of cellular IAP (SfIAP) through a mechanism involving heterodimerization. Whereas homodimeric Op-IAP3 fails to prevent apoptosis, its heterodimeric complex protects SfIAP from degradation. Compared to short-lived homodimeric SfIAP, the Op-IAP3/SfIAP heterodimer has improved stability and resistance to signal-induced depletion as a direct result of Op-IAP3's own stability, which is derived from the absence of a degron-containing leader and reduced ubiquitination potential due to lysine residue substitutions. As Op-IAP3 levels build during infection, the equilibrium favors the Op-IAP3/SfIAP heterodimeric complex. Then, as SfIAP is consumed by autoubiquitination or caspase-binding mediated ubiquitination, active SfIAP dissociates from the heterodimer to replenish it. The heterodimeric Op-IAP3/SfIAP complex may provide antiapoptotic activity as well.

Evolution of Op-IAP3 stability.

Multiple properties of Op-IAP3 are responsible for SfIAP preservation, even during proapoptotic signaling. First and most conspicuous is Op-IAP3's lack of a degron-containing N-terminal leader, which lepidopteran and dipteran IAPs possess (27, 57). For SfIAP, a signal-inducible phospho-degron embedded within its leader contributes to IAP turnover via proteosome-mediated degradation. Attachment of the leader from either SfIAP or DIAP1 destabilized Op-IAP3 and caused loss of conferred stabilization upon SfIAP (Fig. 3B; see also reference 27). Second, Op-IAP3 is stable compared to cellular IAPs despite the presence of a RING-encoded E3 ubiquitin ligase (5). This property suggests that Op-IAP3 is resistant to RING-mediated autoubiquitination, a process that contributes to cellular IAP instability (32). To explore this possibility, we surveyed Op-IAP3 and SfIAP for potential ubiquitination sites (Fig. 9). SfIAP possesses 23 lysine residues, most of which are conserved within lepidopteran cellular IAPs. Remarkably, Op-IAP3 lacks 17 of these 23 lysines. Six lysines are missing because Op-IAP3 lacks a degron-containing leader (Fig. 9A), whereas the others represent substitutions within Op-IAP3. Among 21 closely related viral IAPs, the substitutions comprise a variety of amino acid residues, suggesting that there is strong selective pressure against lysine residues at these positions within the viral IAPs (Fig. 9A). In particular, three surface-exposed lysines (K99, K105, and K109) positioned within an α-helix of SfIAP BIR1 (Fig. 9B) are replaced within Op-IAP3. Although lepidopteran IAP ubiquitination sites are not defined, the analogous α-helix within the survivin BIR is ubiquitinated here (58). Third, Op-IAP3's loss of caspase binding contributes to its stability. DIAP1's association with effector caspase DrICE leads to its cleavage and the resulting degradation by the N-end rule pathway (57). Initiator caspase DRONC also cleaves DIAP1, which leads to proteasomal degradation (59). Thus, loss of Spodoptera caspase association (Fig. 5C) likely reduces Op-IAP3 proteolysis and degradation. Collectively, these attributes contribute to Op-IAP3's half-life, which is five times longer than that of the cellular IAP (SfIAP) with which it interacts.

FIG 9.

Deficiency of potential ubiquitination sites in Op-IAP3. (A) Lysine comparisons. The 99-residue SfIAP leader contains six lysines (red) that are absent in leaderless Op-IAP3 (top). SfIAP BIR1 (middle) and BIR2 (bottom) contain four lysines each (red) that are replaced in Op-IAP3. The percent conservation (pink) of each lysine among 15 lepidopteran cellular IAPs or at the identical position among 21 viral IAPs is indicated next to the SfIAP or Op-IAP3 sequence, respectively. Lysines (blue) found in Op-IAP3 or both Op-IAP3 and SfIAP are also indicated. Overall, Op-IAP3 (12 lysines) possesses 48% fewer lysines than cellular SfIAP (23 lysines). Conserved BIR residues are highlighted in black. (B) Model of SfIAP BIR1. Residues 41 to 112 of Drosophila DIAP1's BIR1, which is most closely related to SfIAP's BIR1 (see alignment at bottom), is displayed from its crystal structure (PDB 3SIP [53]). To visualize surface-exposed lysines K99, K105, and K109 (red) that represent potential ubiquitination sites in SfIAP, the corresponding DIAP1 residues (R43, K49, and D53) were replaced with lysine by using PyMol (54). The corresponding positions in Op-IAP3's BIR1 are occupied by Asn, Gly, and Asn, respectively.

Mechanism of Op-IAP3 conferred stability.

Our findings indicate that Op-IAP3 must interact with SfIAP to prevent signal-induced turnover and thereby preserve antiapoptotic function (Fig. 8). Whereas Op-IAP3 interacted with endogenous and overexpressed SfIAP (Fig. 4A and B), it interacted poorly with cellular DIAP1. Because Op-IAP3 fails to prevent apoptosis in Drosophila cells (12, 37, 44), there is a direct correlation between IAP interaction and antiapoptotic activity. Importantly, Op-IAP3 failed to prevent apoptosis in Spodoptera cells under conditions wherein endogenous SfIAP was selectively eliminated by using RNAi (Fig. 7). Thus, Op-IAP3 requires SfIAP for antiapoptotic activity. Interestingly, Op-IAP3-mediated stabilization of SfIAP resembles that of mammalian survivin, the single BIR IAP that regulates vertebrate cell division but also can bind and stabilize caspase inhibitor XIAP, albeit through an unknown mechanism (60). Conversely, there exist examples of cellular IAPs that negatively regulate IAP abundance through heterodimeric complex formation in a RING-dependent manner (61–63). Viral Op-IAP3 provides the first example of a RING-containing IAP that is nonfunctional by itself, yet upregulates or stabilizes a cellular IAP.

Because Op-IAP3 and SfIAP are closely related and each homodimerizes (8, 11), it is likely that they heterodimerize in the same manner (Fig. 8). Our studies indicate that the BIRs (8, 11) and the C-terminal RING (D. Tran and P. Friesen, unpublished data) contribute to these IAP/IAP interactions. Dimerization of the RING of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 is required for E3 ligase activity (reviewed in reference 33). RING-mediated autoubiquitination of IAP homo- and heterodimers appears to be important for the regulation of IAP levels and thus apoptosis (32, 64). In the case of an Op-IAP3/SfIAP heterodimer, a stable autoubiquitination-resistant protein (Op-IAP3) is partnered with a closely related but ubiquitination-sensitive partner (SfIAP). Thus, the potential for autoubiquitination-mediated turnover of the heterodimer is very reduced compared to that of the cellular IAP homodimer. The Op-IAP3/SfIAP heterodimer is further stabilized by possession of only a single leader-encoded phospho-degron (Fig. 8). Our studies indicate that maximum instability is conferred by dual leader-encoded degrons, as demonstrated by the short half-life of both dimeric SfIAP and Op-IAP3SL (Fig. 3B).

An unanswered question is whether heterodimeric Op-IAP3/SfIAP also has antiapoptotic activity (Fig. 8). Despite Op-IAP3's deficiency for caspase interaction, the SfIAP partner presumably could bind Sf-caspase-1 (Fig. 5) and carry out ubiquitination. Consistent with this possibility, Op-IAP3 RING is a functional E3 ligase (27, 65) and thus could dimerize with that of SfIAP to mediate ubiquitination of bound caspases. Indeed, the Op-IAP3 RING is required for antiapoptotic activity (11, 13, 65). Further studies are required to test this possibility and uncover other mechanisms by which Op-IAP3 might improve SfIAP's anticaspase activity in a heterodimeric complex.

Alternative Op-IAP3 mechanisms.

Op-IAP3 can block apoptosis in vertebrate cells by binding to the proapoptotic IBM-containing protein Smac, thereby interfering with Smac-mediated antagonism of XIAP, which prolongs XIAP-mediated anticaspase activity (20). This finding raises the possibility that Op-IAP3 also preserves SfIAP levels and function by sequestering yet-to-be-identified IAP antagonists in baculovirus-infected Spodoptera cells that would cause SfIAP depletion. Although not ruled out, our studies here suggest that this mechanism is unlikely. First, multiple Op-IAP3 mutations in BIR2, which disrupted the IBM-binding grove and caused loss of Smac and Hid association (20), had little effect on Op-IAP3's capacity to block virus-induced apoptosis (Fig. 6A). Second, the short-lived Op-IAP3SL and Op-IAP3DL chimeras failed to block virus-induced apoptosis (data not shown). These modified IAPs were expected to have a wild-type capacity to bind IBM-containing IAP antagonists and should have titrated these death factors away from the cellular IAP. Finally, E3 ligase-defective Op-IAP3 mutation I223A was produced at high levels yet failed to block virus-induced apoptosis (Fig. 6). This finding indicates that not only is the E3 ligase activity (RING) required, but direct binding and sequestration of IBM-containing death factors do not account for the antiapoptotic activity of Op-IAP3. Indeed, sequestration of Drosophila IAP antagonists is insufficient to prevent apoptosis, as Op-IAP3 binds Reaper and Hid, yet fails to prevent apoptosis in Drosophila (12–14, 38, 39). Thus, it is unlikely that Op-IAP3 sequesters Spodoptera IAP antagonists, indirectly preserving SfIAP levels and function. Rather, our study indicates that Op-IAP3 is an evolutionarily altered cellular IAP that has lost normal degradative-response motifs and acts to stabilize cellular IAP through a novel mechanism requiring direct interaction. As such, it provides another clever example by which viruses have adopted a cellular death regulator and modified it for their specific needs, including counteracting the antiviral defenses of the host.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jonathan Mitchell and Rebecca Cerio for reagents and helpful discussions.

Funding Statement

Additional funding was provided by NIH Predoctoral Traineeships T32 GM07215 (R.L.V.) and T32 AI078985 (N.M.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Orme M, Meier P. 2009. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in Drosophila: gatekeepers of death. Apoptosis 14:950–960. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivasula SM, Ashwell JD. 2008. IAPs: what's in a name? Mol Cell 30:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumble JM, Duckett CS. 2008. Diverse functions within the IAP family. J Cell Sci 121:3505–3507. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gyrd-Hansen M, Meier P. 2010. IAPs: from caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-κB, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 10:561–574. doi: 10.1038/nrc2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clem RJ. 2015. Viral IAPs, then and now. Semin Cell Dev Biol 39:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Best SM. 2008. Viral subversion of apoptotic enzymes: escape from death row. Annu Rev Microbiol 62:171–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnbaum MJ, Clem RJ, Miller LK. 1994. An apoptosis-inhibiting gene from a nuclear polyhedrosis virus encoding a polypeptide with Cys/His sequence motifs. J Virol 68:2521–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerio RJ, Vandergaast R, Friesen PD. 2010. Host insect inhibitor-of-apoptosis SfIAP functionally replaces baculovirus IAP but is differentially regulated by its N-terminal leader. J Virol 84:11448–11460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01311-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Q, Deveraux QL, Maeda S, Salvesen GS, Stennicke HR, Hammock BD, Reed JC. 2000. Evolutionary conservation of apoptosis mechanisms: lepidopteran and baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis proteins are inhibitors of mammalian caspase-9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:1427–1432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay BA, Wassarman DA, Rubin GM. 1995. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell 83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hozak RR, Manji GA, Friesen PD. 2000. The BIR motifs mediate dominant interference and oligomerization of inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP. Mol Cell Biol 20:1877–1885. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1877-1885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright CW, Means JC, Penabaz T, Clem RJ. 2005. The baculovirus anti-apoptotic protein Op-IAP does not inhibit Drosophila caspases or apoptosis in Drosophila S2 cells and instead sensitizes S2 cells to virus-induced apoptosis. Virology 335:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vucic D, Kaiser WJ, Miller LK. 1998. A mutational analysis of the baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP. J Biol Chem 273:33915–33921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser WJ, Vucic D, Miller LK. 1998. The Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis D-IAP1 suppresses cell death induced by the caspase drICE. FEBS Lett 440:243–248. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenev T, Zachariou A, Wilson R, Ditzel M, Meier P. 2005. IAPs are functionally non-equivalent and regulate effector caspases through distinct mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol 7:70–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Riordan MX, Bauler LD, Scott FL, Duckett CS. 2008. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in eukaryotic evolution and development: a model of thematic conservation. Dev Cell 15:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mace PD, Shirley S, Day CL. 2010. Assembling the building blocks: structure and function of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell Death Differ 17:46–53. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hay BA, Guo M. 2006. Caspase-dependent cell death in Drosophila. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22:623–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012804.093845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silke J, Vucic D. 2014. IAP family of cell death and signaling regulators. Methods Enzymol 545:35–65. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801430-1.00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson JC, Wilkinson AS, Scott FL, Csomos RA, Salvesen GS, Duckett CS. 2004. Neutralization of Smac/Diablo by inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs). A caspase-independent mechanism for apoptotic inhibition. J Biol Chem 279:51082–51090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenev T, Ditzel M, Zachariou A, Meier P. 2007. The antiapoptotic activity of insect IAPs requires activation by an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Death Differ 14:1191–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muro I, Hay BA, Clem RJ. 2002. The Drosophila DIAP1 protein is required to prevent accumulation of a continuously generated, processed form of the apical caspase DRONC. J Biol Chem 277:49644–49650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Settles EW, Friesen PD. 2008. Flock house virus induces apoptosis by depletion of Drosophila inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein DIAP1. J Virol 82:1378–1388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01941-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmermann KC, Ricci JE, Droin NM, Green DR. 2002. The role of ARK in stress-induced apoptosis in Drosophila cells. J Cell Biol 156:1077–1087. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20112068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q, Clem RJ. 2011. Defining the core apoptosis pathway in the mosquito disease vector Aedes aegypti: the roles of iap1, ark, dronc, and effector caspases. Apoptosis 16:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0558-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandergaast R, Schultz KL, Cerio RJ, Friesen PD. 2011. Active depletion of host cell inhibitor-of-apoptosis proteins triggers apoptosis upon baculovirus DNA replication. J Virol 85:8348–8358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00667-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandergaast R, Mitchell JK, Byers NM, Friesen PD. 2015. Insect inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) proteins are negatively regulated by signal-induced N-terminal degrons absent within viral IAP proteins. J Virol 89:4481–4493. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03659-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brodsky MH, Nordstrom W, Tsang G, Kwan E, Rubin GM, Abrams JM. 2000. Drosophila p53 binds a damage response element at the reaper locus. Cell 101:103–113. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, Steller H. 2002. Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nat Cell Biol 4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/ncb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman-Bachinsky Y, Ryoo HD, Ciechanover A, Gonen H. 2007. Regulation of the Drosophila ubiquitin ligase DIAP1 is mediated via several distinct ubiquitin system pathways. Cell Death Differ 14:861–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuranaga E, Kanuka H, Tonoki A, Takemoto K, Tomioka T, Kobayashi M, Hayashi S, Miura M. 2006. Drosophila IKK-related kinase regulates nonapoptotic function of caspases via degradation of IAPs. Cell 126:583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaux DL, Silke J. 2005. IAPs, RINGs and ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:287–297. doi: 10.1038/nrm1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budhidarmo R, Day CL. 2015. IAPs: modular regulators of cell signalling. Semin Cell Dev Biol 39:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seshagiri S, Miller LK. 1997. Baculovirus inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) block activation of Sf-caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:13606–13611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manji GA, Hozak RR, LaCount DJ, Friesen PD. 1997. Baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis functions at or upstream of the apoptotic suppressor P35 to prevent programmed cell death. J Virol 71:4509–4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LaCount DJ, Hanson SF, Schneider CL, Friesen PD. 2000. Caspase inhibitor P35 and inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP block in vivo proteolytic activation of an effector caspase at different steps. J Biol Chem 275:15657–15664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zoog SJ, Schiller JJ, Wetter JA, Chejanovsky N, Friesen PD. 2002. Baculovirus apoptotic suppressor P49 is a substrate inhibitor of initiator caspases resistant to P35 in vivo. EMBO J 21:5130–5140. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7594736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vucic D, Kaiser WJ, Harvey AJ, Miller LK. 1997. Inhibition of Reaper-induced apoptosis by interaction with inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:10183–10188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vucic D, Kaiser WJ, Miller LK. 1998. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins physically interact with and block apoptosis induced by Drosophila proteins HID and GRIM. Mol Cell Biol 18:3300–3309. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.6.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright CW, Clem RJ. 2002. Sequence requirements for Hid binding and apoptosis regulation in the baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP. Hid binds Op-IAP in a manner similar to Smac binding of XIAP. J Biol Chem 277:2454–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaughn JL, Goodwin RH, Tompkins GJ, McCawley P. 1977. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae). In Vitro 13:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF02615077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider I. 1972. Cell lines derived from late embryonic stages of Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol 27:353–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hershberger PA, Dickson JA, Friesen PD. 1992. Site-specific mutagenesis of the 35-kilodalton protein gene encoded by Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: cell line-specific effects on virus replication. J Virol 66:5525–5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lannan E, Vandergaast R, Friesen PD. 2007. Baculovirus caspase inhibitors P49 and P35 block virus-induced apoptosis downstream of effector caspase DrICE activation in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J Virol 81:9319–9330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00247-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell JK, Byers NM, Friesen PD. 2013. Baculovirus F-box protein LEF-7 modifies the host DNA damage response to enhance virus multiplication. J Virol 87:12592–12599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02501-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cartier JL, Hershberger PA, Friesen PD. 1994. Suppression of apoptosis in insect cells stably transfected with baculovirus p35: dominant interference by N-terminal sequences p35(1-76). J Virol 68:7728–7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guy MP, Friesen PD. 2008. Reactive-site cleavage residues confer target specificity to baculovirus P49, a dimeric member of the P35 family of caspase inhibitors. J Virol 82:7504–7514. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00231-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertin J, Mendrysa SM, LaCount DJ, Gaur S, Krebs JF, Armstrong RC, Tomaselli KJ, Friesen PD. 1996. Apoptotic suppression by baculovirus P35 involves cleavage by and inhibition of a virus-induced CED-3/ICE-like protease. J Virol 70:6251–6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olson VA, Wetter JA, Friesen PD. 2001. Oligomerization mediated by a helix-loop-helix-like domain of baculovirus IE1 is required for early promoter transactivation. J Virol 75:6042–6051. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6042-6051.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schultz KL, Wetter JA, Fiore DC, Friesen PD. 2009. Transactivator IE1 is required for baculovirus early replication events that trigger apoptosis in permissive and nonpermissive cells. J Virol 83:262–272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01827-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.UniProt Consortium. 2015. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D204–D212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X, Wang J, Shi Y. 2011. Structural mechanisms of DIAP1 auto-inhibition and DIAP1-mediated inhibition of drICE. Nat Commun 2:408. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrödinger LLC. 2010. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.4.1. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmad M, Srinivasula SM, Wang L, Litwack G, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. 1997. Spodoptera frugiperda caspase-1, a novel insect death protease that cleaves the nuclear immunophilin FKBP46, is the target of the baculovirus antiapoptotic protein P35. J Biol Chem 272:1421–1424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang N, Civciristov S, Hawkins CJ, Clem RJ. 2013. SfDronc, an initiator caspase involved in apoptosis in the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 43:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ditzel M, Wilson R, Tenev T, Zachariou A, Paul A, Deas E, Meier P. 2003. Degradation of DIAP1 by the N-end rule pathway is essential for regulating apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 5:467–473. doi: 10.1038/ncb984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altieri DC. 2015. Survivin—the inconvenient IAP. Semin Cell Dev Biol 39:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muro I, Means JC, Clem RJ. 2005. Cleavage of the apoptosis inhibitor DIAP1 by the apical caspase DRONC in both normal and apoptotic Drosophila cells. J Biol Chem 280:18683–18688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dohi T, Okada K, Xia F, Wilford CE, Samuel T, Welsh K, Marusawa H, Zou H, Armstrong R, Matsuzawa S, Salvesen GS, Reed JC, Altieri DC. 2004. An IAP-IAP complex inhibits apoptosis. J Biol Chem 279:34087–34090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Conze DB, Albert L, Ferrick DA, Goeddel DV, Yeh WC, Mak T, Ashwell JD. 2005. Posttranscriptional downregulation of c-IAP2 by the ubiquitin protein ligase c-IAP1 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 25:3348–3356. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3348-3356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheung HH, Plenchette S, Kern CJ, Mahoney DJ, Korneluk RG. 2008. The RING domain of cIAP1 mediates the degradation of RING-bearing inhibitor of apoptosis proteins by distinct pathways. Mol Biol Cell 19:2729–2740. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silke J, Kratina T, Chu D, Ekert PG, Day CL, Pakusch M, Huang DC, Vaux DL. 2005. Determination of cell survival by RING-mediated regulation of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein abundance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:16182–16187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502828102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ditzel M, Meier P. 2002. IAP degradation: decisive blow or altruistic sacrifice? Trends Cell Biol 12:449–452. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Green MC, Monser KP, Clem RJ. 2004. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of the antiapoptotic baculovirus protein Op-IAP3. Virus Res 105:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]