Significance

Despite fascinating scientists for over 200 years, little at the molecular level is known about tardigrades, microscopic animals resistant to extreme stresses. We present the genome of a tardigrade. Approximately one-sixth of the genes in the tardigrade genome were found to have been acquired through horizontal transfer, a proportion nearly double the proportion of previous known cases of extreme horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in animals. Foreign genes have impacted the composition of the tardigrade genome: supplementing, expanding, and replacing endogenous gene families, including those families implicated in stress tolerance. Our results extend recent findings that HGT is more prevalent in animals than previously suspected, and they suggest that organisms that survive extreme stresses might be predisposed to acquiring foreign genes.

Keywords: horizontal gene transfer, lateral gene transfer, genome, tardigrade, stress tolerance

Abstract

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT), or the transfer of genes between species, has been recognized recently as more pervasive than previously suspected. Here, we report evidence for an unprecedented degree of HGT into an animal genome, based on a draft genome of a tardigrade, Hypsibius dujardini. Tardigrades are microscopic eight-legged animals that are famous for their ability to survive extreme conditions. Genome sequencing, direct confirmation of physical linkage, and phylogenetic analysis revealed that a large fraction of the H. dujardini genome is derived from diverse bacteria as well as plants, fungi, and Archaea. We estimate that approximately one-sixth of tardigrade genes entered by HGT, nearly double the fraction found in the most extreme cases of HGT into animals known to date. Foreign genes have supplemented, expanded, and even replaced some metazoan gene families within the tardigrade genome. Our results demonstrate that an unexpectedly large fraction of an animal genome can be derived from foreign sources. We speculate that animals that can survive extremes may be particularly prone to acquiring foreign genes.

Tardigrades (also known as water bears; Fig. 1A) are animals that are known for anhydrobiosis (surviving life without water). Tardigrades survive several additional stresses normally thought to be incompatible with life (1, 2), including extreme temperatures (−272 to 151 °C) (3, 4), radiation intensities orders of magnitude greater than humans can withstand (5, 6), incubation in organic solvents (7), and extremes of pressure (8). Tardigrades are the only animal known to survive exposure to the vacuum of space (8).

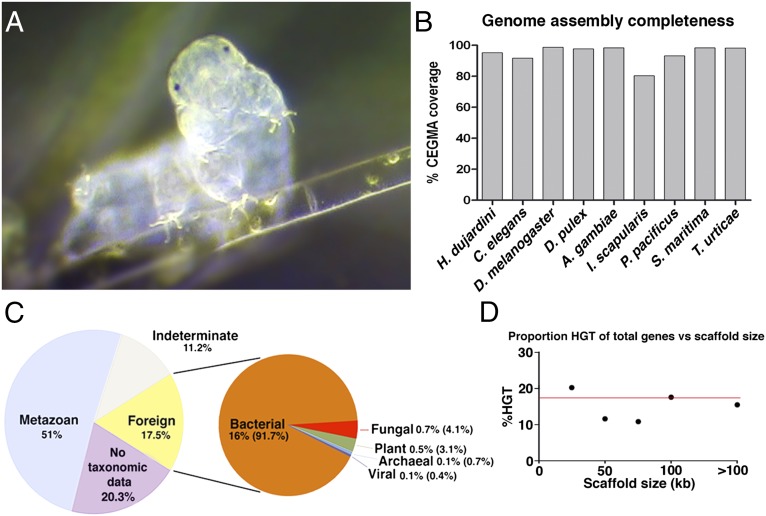

Fig. 1.

Genome of the tardigrade H. dujardini. (A) Light micrograph of a tardigrade specimen. Image courtesy of S. Stammers, used with permission. (B) Percentage of coverage (complete + partial) for core eukaryotic genes in our H. dujardini genome, as well as genome assemblies from recently sequenced and model organisms. A. gambiae, Anopheles gambiae; CEGMA, core eukaryotic genes mapping approach; D. pulex, Daphnia pulex; I. scapularis, Ixodes scapularis; P. pacificus, Pristionchus pacificus; S. maritima, Strigamia maritima; T. urticae, Tetranychus urticae. (C) Source of genes in the H. dujardini genome as determined by HGT index calculations following Galaxy tools taxonomy extraction. (D) Proportion of horizontally transferred genes vs. total number of genes by scaffold size in the H. dujardini genome. The red line indicates the proportion of HGT genes in the total assembly (17.5%).

Water bears comprise their own phylum, the phylum Tardigrada, which, along with the phyla Arthropoda and Nematoda, is contained within the group Ecdysozoa. The phylogenetic position of tardigrades near two of the best-studied invertebrate model systems, Caenorhabditis elegans (a nematode) and Drosophila melanogaster (an arthropod), makes them attractive models for studying the evolution of molecular and developmental mechanisms (9).

Despite the interest in and value of tardigrades as a model system, there are minimal sequencing resources for this phylum of animals to date. To address this deficit, we have sequenced the genome of the tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini. We find that tardigrades have been taking up and incorporating foreign DNA into their genomes to a degree unprecedented in animals.

Results and Discussion

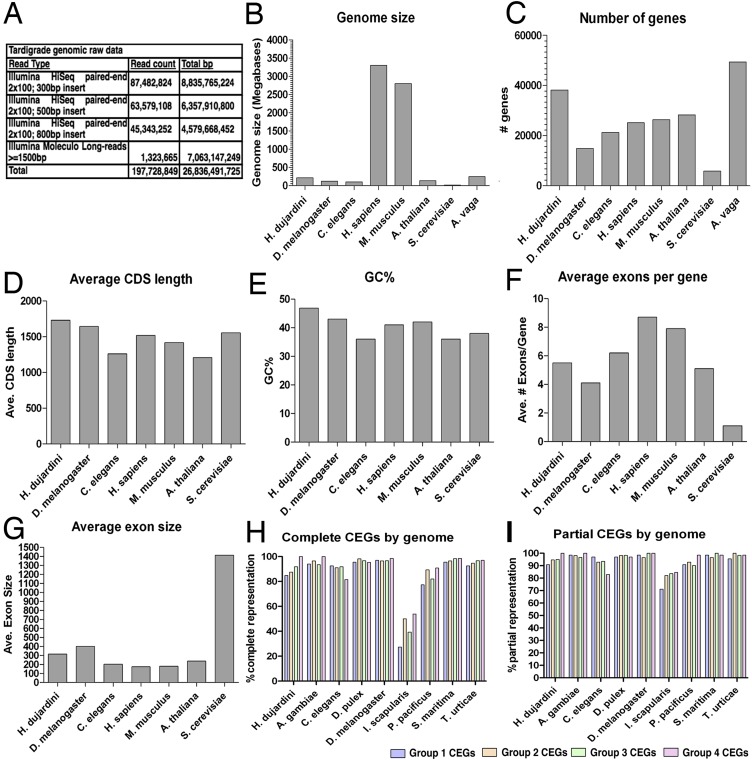

We extracted DNA from cultures of the tardigrade H. dujardini that were founded by a single parthenogenic animal, and sequenced the genome to high average coverage (126-fold) using a combination of Illumina Moleculo long reads and short insert mate pair libraries (Fig. S1A). A total of 26.8 Gb of raw reads resulted in an assembly 212.3 Mb in length containing 38,145 predicted genes (Fig. S1 B and C). The draft genome is comparable to existing eukaryotic reference genomes in terms of the percentage of guanine-cytosine content, number of exons per gene, exon size, and length of coding sequences (Fig. S1 D–G). The draft genome assembly has a contig N50 of 15.2 kb and a scaffold N50 only slightly greater (15.9 kb), despite the strong depth of coverage and the combination of paired-end reads and Moleculo long reads. Both Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Illumina scaffold analysis suggests a large degree of repetitive sequence is present in the H. dujardini genome and is a likely cause of limited scaffold assembly (SI Text). Despite the limited degree of scaffold assembly, the draft genome assembly appears nearly complete, because it contains 95.16% of core eukaryotic genes, a proportion that is similar to genomes of C. elegans and other model organisms that were used to build the core eukaryotic gene set (10, 11) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 H and I). In further support of the degree of completeness, our assembly contains 95.9% of all publicly available H. dujardini EST sequences. Of the remaining 216 missing EST sequences, only 48 are from metazoan sources, with the remaining having no hits, hits with no taxonomic information, or hits to nonmetazoan sequences, suggesting that the majority of missing ESTs are contaminants or sequencing artifact.

Fig. S1.

Comparison of H. dujardini genome statistics. (A) Genomic sequencing resources generated by this study. A comparison of the genome size (B), number of genes (C), average coding sequence length (D), guanine-cytosine content (E), average exon number per gene (F), and average exon size (G) for our H. dujardini assembly with the genome assemblies of several other model organisms was performed. Complete (H) and partial (I) core eukaryotic gene (CEG) coverage within our H. dujardini genome assembly is shown. A. gambiae, Anopheles gambiae; A. vaga, Adineta vaga; D. pulex, Daphnia pulex; I. scapularis, Ixodes scapularis; P. pacificus, Pristionchus pacificus; S. maritima, Strigamia maritima; T. urticae, Tetranychus urticae.

Preliminary BLAST analysis showed that an unexpectedly large proportion of the genes present in the H. dujardini genome had a top hit to sequences from nonmetazoan sources, suggesting that a large fraction of H. dujardini genes might have been acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), since H. dujardini split from other animals with sequenced genomes. However, BLAST analysis alone can overestimate the degree of HGT (12, 13). Therefore, we took several steps to estimate the overall degree of HGT reliably, further testing whether genes that appear to derive from HGT were indeed horizontally transferred and not simply contaminants or results of convergent evolution.

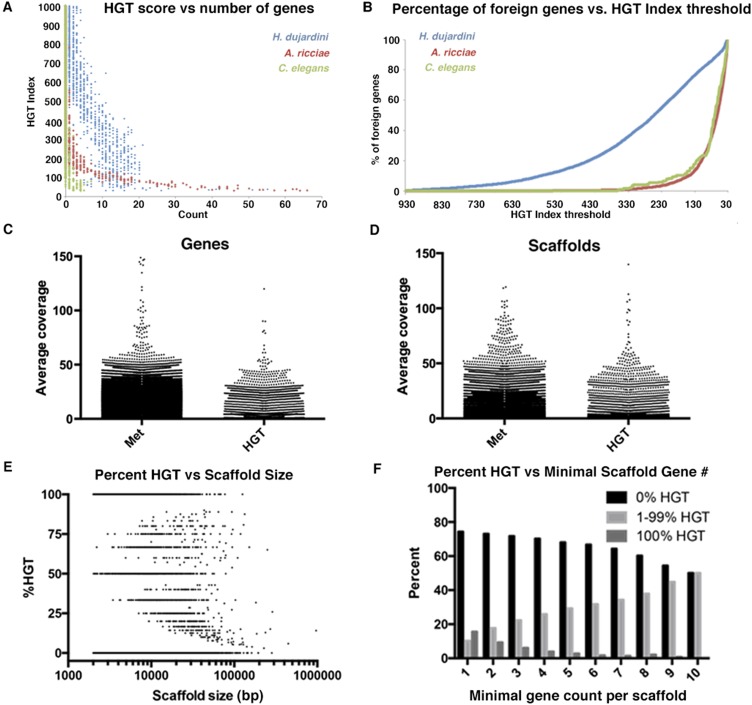

The rotifer Adineta ricciae is the animal with the highest known degree of HGT to date, for which an estimated 9.6% of genes are of foreign origin (14). We used the same metric as was used previously for A. ricciae to calculate an HGT index value for each gene. The HGT index has been validated by phylogenetics, with maximum likelihood analysis as a useful metric for HGT (14). Using the HGT indexing method, we found that 6,663 H. dujardini genes (17.5% of all genes) had HGT index values greater than or equal to a previously established threshold, suggesting that they are likely to be derived from nonmetazoan sources (14) (Dataset S1). Increasing the stringency of the threshold continued to support a high degree of HGT (Fig. S2). The 6,663 genes showed closest sequence similarity to genes from bacteria, Archaea, fungi, plants, and viruses, with the majority (91.7%) most closely matching sequences from diverse bacteria (1,361 bacterial species, 40 archaeal species, 91 fungal species, 45 plant species, and 6 different viruses; Fig. 1C and Dataset S1). Our tardigrade cultures are fed algae, not bacteria, and although our algal cultures are not axenic, we would expect little to no bacterial contamination in our sequencing data. To ensure bacterial contamination is not a major issue in our assembly, we performed several independent analyses addressing this issue. First, we examined the coverage of all genes and scaffolds within our assembly. If foreign-looking sequences were contaminants, one would expect their abundance to be significantly less than the abundance of true tardigrade genes. Although there was variation in coverage found between genes and scaffolds, this variation was not biased but rather appears to be systematically present in both metazoan and foreign sequences. For example, the SD in coverage for a gene of metazoan origin was 138 compared with 108 for genes of foreign origin. Additionally, many genes of foreign origin were found to have higher sequencing coverage than genes of metazoan origin, and vice versa (Fig. S2 C and D). Second, all available bacterial rRNA sequences were downloaded from the Ribosomal Database Project (rdp.cme.msu.edu/) and used to perform reciprocal best-hit BLAST analysis against scaffolds in our genome assembly. Only four scaffolds in our assembly encoded a putative bacterial rRNA. These scaffolds were small, ranging in size from 4,331–14,016 bases and containing only nine (eight HGT and one non-HGT of unknown function) genes, suggesting that potential bacterial contamination is minimal and does not account for the disproportionately large number of horizontally acquired genes. Furthermore, general contamination in our assembly appears to be minimal. For example, we find no human contaminating sequence (Dataset S1). Together with codon optimization, intronization, and PCR analysis (discussed below), our analysis of gene coverage and rRNA contamination suggests that widespread contamination is not a major issue within our assembly.

Fig. S2.

Most foreign tardigrade genes score well above the HGT index threshold. (A) Graph showing the number of genes with a given HGT index score (to the nearest integer) for the tardigrade H. dujardini, rotifer A. ricciae, and nematode C. elegans. (B) Graph showing the cumulative percentage of foreign genes accounted for as the HGT index threshold is lowered to 30. For example, with an HGT index threshold of 30, 100% of H. dujardini foreign genes are accounted for, whereas increasing the threshold to 250 still accounts for 50% of all H. dujardini foreign genes. (C) Average coverage for genes of metazoan (Met) or foreign origin. (D) Average coverage for scaffolds containing genes of metazoan or foreign origin. (E) Plot showing the percentage of horizontally acquired genes vs. scaffold size. (F) Graph showing the percentage of scaffolds with no (black bars), all (dark gray bars), or some (light gray bars) horizontally acquired genes, as the minimal gene count per scaffold is increased. As the minimal number of genes per scaffold increases, the number of scaffolds with only horizontally acquired genes decreases.

No one bacterial species accounted for more than 3% of horizontally transferred genes. The proportion of genes with an HGT index exceeding the threshold was similar among scaffolds of various lengths (Fig. 1D, Fig. S2, and SI Text), suggesting that the genes predicted to be horizontally transferred were not concentrated among the least well-assembled sequences and that they are not all clustered within one long scaffold but are instead proportionally distributed throughout the assembly and the genome.

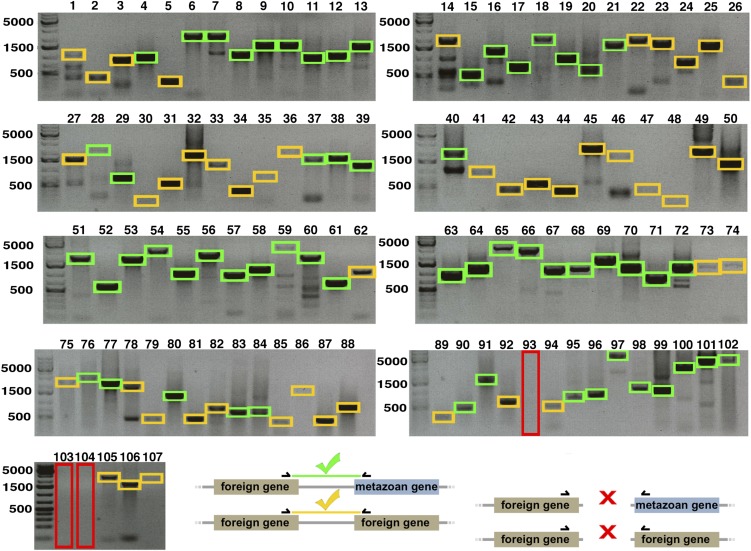

To analyze more directly whether 17.5% is a reliable estimate of the proportion of genes derived from foreign sources, we constructed and analyzed gene trees for a sample of 107 genes using both maximum likelihood and Bayesian analysis (Fig. 2B and Dataset S2). These sequences comprised 100 genes selected at random and seven hand-picked genes of interest, including predicted bacterial-, fungal-, archaeal-, plant-, and viral-derived genes. Together, the randomly selected genes represented a diverse set of gene characteristics: Percentage of identity with top nonmetazoan sources ranged from 88% to 25%, and intron counts (discussed further below) ranged from 20 to 0. A total of 103 of the 107 genes had sufficient sequence similarity to make gene trees. We used the same scoring system as was used for rotifers (14) and found that 101 of 103 of the resulting gene trees supported the HGT index-based conclusion by clustering the H. dujardini gene with a single nonmetazoan gene taxon (e.g., the H. dujardini gene fell within a clade of bacterial genes) or strongly rejecting monophyly with metazoan sequences, with the remaining two trees being ambiguous. None of our trees showed strong support for a predicted foreign gene, being instead monophyletic with metazoan sequences (Dataset S2). The tree topologies found, together with maximum likelihood and Bayesian analysis results and the lack of predicted U2-spliceosomal introns in many bacterial-like genes (42.9% of these genes, as discussed below), indicate that alternative explanations (sequence convergence or loss of genes in multiple independent metazoan clades) cannot easily explain the observed similarity to foreign sequences. These results confirm that the HGT index (14) is an effective tool for rapidly predicting the taxonomic origins of genes in large datasets, and they support the conclusion that a large proportion of genes in the draft H. dujardini genome assembly are of nonmetazoan origin.

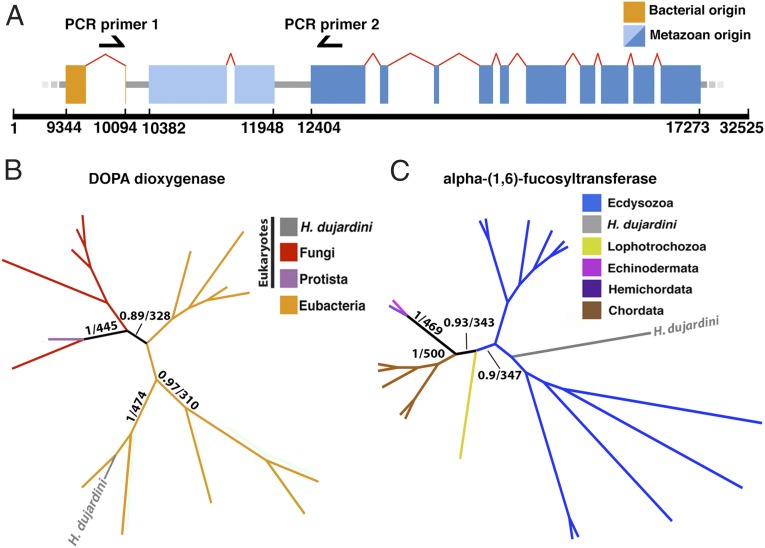

Fig. 2.

HGT in the genome of H. dujardini. (A) Schematic representation of a portion of scaffold 962. Boxes represent exons, red arches represent U2 spliceosomal introns, and black arrows represent primer sites. (B) Gene 0.37 (orange, bases 9,344–10,094) encodes a putative bacterially derived DOPA dioxygenase with no identifiable animal homologs. (C) Gene 0.3 (dark blue, bases 12,404–17,273) encodes a tardigrade (metazoan) FUT8 gene. Supports on trees in B and C are given as Bayesian/bootstrap (500) supports. Trees for the remaining 102 genes and associated information are available in Dataset S2.

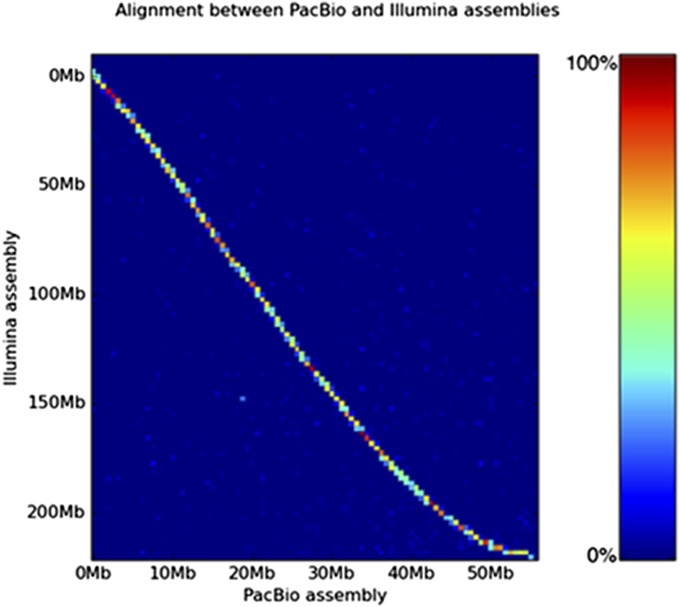

Despite similarities in coverage between metazoan and foreign sequences, assembly artifacts might result in contaminant sequences assembling next to tardigrade genes. Therefore, we looked for signs of contamination and tested directly the accuracy of assembly for a sample of genes by two methods. First, we performed PCR to test physical linkage of pairs of genes that were found on the same genomic scaffolds (Fig. 2A, Fig. S3, and Dataset S2). For PCR experiments, we used the same randomly selected set of genes as used for tree building above. For 104 of 107 genes, we recovered amplified products of the appropriate size, confirming that foreign genes are physically present within the H. dujardini genome (Fig. S3). Second, we used low-depth PacBio single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing for comparison with our initial assembly (SI Text). PacBio sequencing uses real-time imaging of synthesis of single DNA molecules to produce long sequencing reads. Because each long read comes from a single DNA molecule, the resulting contigs cannot be assembly artifacts; therefore, these data allowed us to test whether our initial assembly produced chimeric contigs. Our two assemblies were highly congruent. Synteny was preserved between contigs, and assemblies were 98.53% concordant per base (Fig. S4). Therefore, both PCR and resequencing provide support for the accuracy of our assembly.

Fig. S3.

Genes of metazoan and foreign origin are physically linked in the H. dujardini genome. Results and a schematic of PCRs performed with primers bridging genes predicted to be present on the same genomic scaffold (associated information is available in Dataset S2) are shown. Green and orange boxes highlight foreign-metazoan gene pairs and foreign-foreign gene pairs, respectively, that produced PCR products of the correct size. Large (red) boxes highlight PCR reactions failing to recover products of the correct size.

Fig. S4.

Comparison with PacBio long reads supports the accuracy of the H. dujardini genome assembly. A heat map shows the concordance between the PacBio and Illumina assemblies. The independently sequenced PacBio sequences are highly similar to the Illumina assembly, and there is no significant off-diagonal homology that would indicate misassembly or residual heterozygosity. Both sets of contigs are highly congruent. Synteny within contigs is clearly preserved, and assemblies are 98.53% concordant per base.

Fifty-nine of the gene pairs we tested above contained a predicted nonmetazoan member near a metazoan member. Of these gene pairs, 58 (98.3%) gave PCR products of the correct size, suggesting that genes confirmed by our gene trees to be of foreign origin are physically linked to genes of metazoan origin (Fig. S3). For example, these tests included a metazoan alpha-(1,6)-fucosyltransferase (FUT8) gene for which our gene tree confirmed a close relationship with sequences from animals, and specifically ecdysozoans (Fig. 2C). This FUT8 gene is located on a scaffold near a gene that we determined by a gene tree using maximum likelihood and Bayesian analysis to be of bacterial origin, and that, to date, is found in no other animal (Fig. 2B). PCR performed with primers bridging these genes resulted in the correct product being amplified. Because nearly all genes in our sample could be confirmed by gene trees to be of foreign origin and by PCR to be accurately assembled, we consider approximately one-sixth to be a conservative estimate of the proportion of genes horizontally transferred into the H. dujardini genome since the origin of the tardigrades.

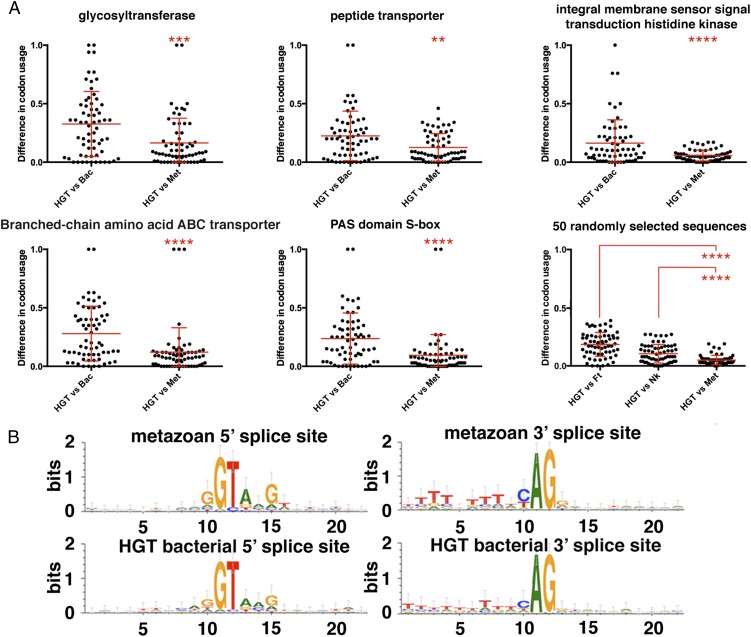

To begin to assess what happens to foreign genes after they have been horizontally transferred, we looked for diagnostic features of metazoan genes within the foreign genes found in the H. dujardini genome. Codon use of bacterially derived genes appears to have evolved metazoan bias, with codon use in horizontally acquired genes in Hypsibius being more similar to metazoan Hypsibius homologs than to their closest bacterial homolog (Fig. 3A). Additionally, average codon use in horizontally transferred genes of bacterial origin was more similar to codon use in genes of metazoan origin in the H. dujardini genome than it was to codon use in genes from highly represented bacterial species (Fig. 3A and Dataset S3). In addition, 57.1% of genes of bacterial origin contained at least one predicted U2-spliceosomal intron, a feature not found in bacterial genes (15) (Fig. 3B and Dataset S3). Consistent with most other eukaryotes, nearly all (99.0%) genes of metazoan origin in the H. dujardini genome contained predicted U2 spliceosomal introns, with the acceptor and donor consensus sequences being essentially identical between introns in genes of bacterial vs. metazoan origin (Fig. 3B). Taken together, our codon use and intron results suggest that horizontally transferred genes evolved properties characteristic of animal genes, and more specifically of the H. dujardini genome, further supporting that they are not artifacts generated by sequence from contaminating sources. Our results suggest that foreign genes have been assimilated into the genome of H. dujardini to a degree that is unprecedented to date in animals.

Fig. 3.

Horizontally transferred genes have acquired characteristics of the metazoan genes. (A) For a particular horizontally transferred gene from bacteria, its closest metazoan homolog (Met) in the H. dujardini genome and its closest bacterial homolog (Bac) were found, and codon use statistics for each codon were calculated and compared. (Lower Right) Additionally, for each of the 64 codons, the difference in codon use between genes of foreign origin in the H. dujardini genome and metazoan genes from the H. dujardini genome, the bacterium Niastella koreensis, and the bacterium Fluviicola taffensis (bacterial species with the highest representation in the H. dujardini genome) was calculated. Horizontal lines represent the average difference between the codon use in Hypsibius genes of foreign origin and each other corresponding dataset. Unpaired t test: **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. (B) Sequence logos generated for U2 intron 5′ and 3′ splice sites for genes of metazoan (Top) and bacterial (Bottom) origin.

We next analyzed the degree to which the genes of foreign origin have expanded, supplemented, or replaced metazoan gene families. Sixty-seven percent of the genes in the assembly had known Pfam annotations, a proportion similar to the proportion of well-annotated reference genomes of model organisms (Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, D. melanogaster, C. elegans, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (16). A total of 99.2% of all protein-coding genes were represented only once in the assembly, with the average number of scaffolds that a single gene was found on being 1.008. This lack of redundancy suggests that any large apparent increases in numbers of protein domains and families within our assembly are due primarily to true expansions and not to assembly redundancy.

To identify these expansions, we compared protein families and domain counts from the H. dujardini genome with protein families and domain counts of the most closely related species with well-annotated genomes [D. melanogaster (Dm) and C. elegans (Ce)]. We identified numerous and diverse expansions: The H. dujardini genome has increased numbers of proteins containing domains involved in classic stress response, including heat shock (3.5-fold vs. Dm and sevenfold vs. Ce) and other chaperone proteins (fourfold vs. Dm and eightfold vs. Ce), DNA damage repair enzymes (3.6-fold vs. Dm and 7.3-fold vs. Ce), and antioxidant pathway members (2.7-fold vs. Dm and 4.7-fold vs. Ce), as well as enzymes involved in carbohydrate (fivefold vs. Dm and 2.8-fold vs. Ce) and lipid metabolism (1.9-fold vs. Dm and 1.5-fold vs. Ce) (Dataset S4).

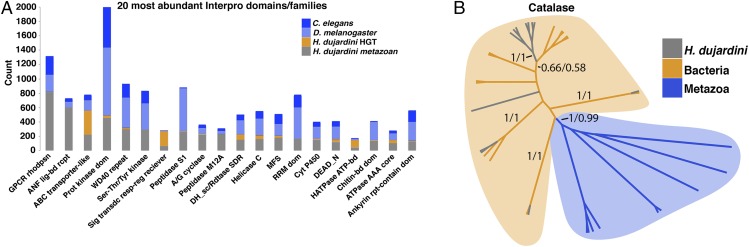

Like typical gene family expansions, many gene family expansions in the H. dujardini genome have arisen through apparent gene duplication events. Other expansions are the result of acquiring homologs by HGT (Fig. 4A and Dataset S4). Some of the most expanded families include those families involved in sensing, responding, and adapting to environmental conditions and stress (Dataset S4). Surprisingly, 13.2% of unique protein domains are represented exclusively by genes of foreign origin, and 47.6% of H. dujardini protein families have been supplemented by at least one foreign member (Dataset S4).

Fig. 4.

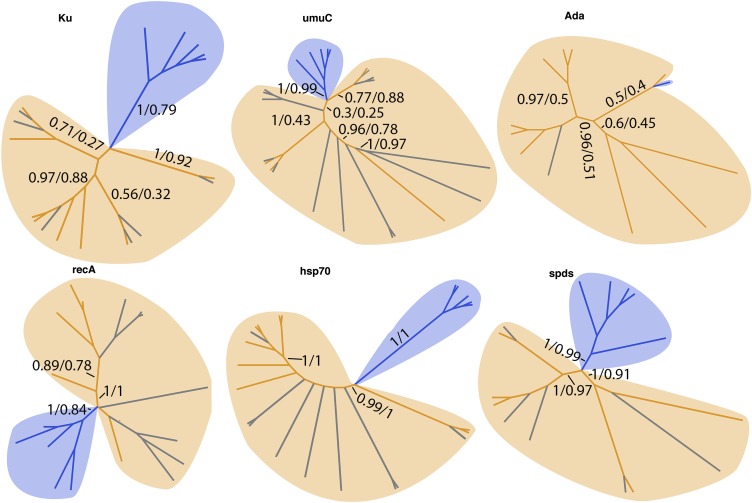

Protein families in the H. dujardini genome have been expanded, supplemented, and replaced by genes acquired through horizontal transfer. (A) Raw counts for the 20 most abundant InterPro domains and families represented by H. dujardini genes of metazoan origin (blue), along with comparative data from two closely related species, D. melanogaster (dark gray) and C. elegans (light gray). The count for each InterPro domain contributed by genes of foreign origin is also shown (orange). ABC, ATP-binding cassette transporter-like; ANF lig-bd rcpt, ligand binding receptor region; Ankyrin rpt-contain dom, Ankyrin repeat-containing domain; Chitin-bd dom, chitin binding domain; Cyt P450, Cytochrome P450; DEAD_N, DEAD-box N-terminal domain; DH_sc/Rdtase SDR, short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases family; GPCR rhodpsn, rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptor domain; HATPase ATP-bd, histidine kinase-like ATPase C-terminal domain; MFS, major facilitator superfamily; Prot kinase dom, Protein kinase domain; RRM dom, RNA recognition motif; Sig transdc resp-reg receiver, signal transduction response regulator receiver domain. (B) Cladogram showing evolutionary relationships between foreign H. dujardini (gray), bacterial (orange), and metazoan (blue) genes implicated in stress tolerance. Numbers on branches indicate Bayesian followed by bootstrap (500) supports.

The two most abundant domains that are contributed exclusively by genes acquired through HGT are catalase immune-responsive domain (IPR010582) and catalase core domain (IPR011614) (Fig. 4B and Dataset S4). Catalases are antioxidant enzymes involved in neutralizing oxidative stress, a major source of damage in cells under various stress conditions (17). Organisms closely related to tardigrades (e.g., C. elegans, D. melanogaster) encode metazoan versions of catalase genes, but H. dujardini appears to have replaced these genes with catalases acquired from foreign sources (Fig. 4B).

Tardigrades accumulate extensive DNA double-strand breaks with prolonged desiccation and when exposed to high levels of radiation (6, 18, 19). A number of protein families involved in DNA repair have been expanded in tardigrades (Dataset S4), and this expansion is due to the acquisition of foreign DNA in many cases. For example, our assembly contains eight genes encoding proteins with a Ku beta-barrel domain (IPR006164). Ku proteins are involved in double-strand break repair, and of the eight putative Ku genes found in our assembly, two are of metazoan origin and six are of foreign origin (Fig. S5 and Dataset S4). Similarly, our assembly contains nine metazoan UV mutant C (umuC) encoding genes and 14 foreign umuC encoding genes. UmuC is a DNA repair protein involved in translesion synthesis, which allows for replication to continue in the presence of broken DNA that would typically stall the replication machinery (20) (Fig. S5). Interestingly, our assembly also includes a gene of foreign origin encoding an adaptive response (Ada) DNA repair protein. Ada proteins are common bacterial enzymes that help cope with stress induced by alkylating agents (Fig. S5). Additionally, 6 of 13 DNA recombination and repair A (recA; Rad51 in eukaryotes) genes in our assembly are predicted to come from bacterial sources (Fig. S5).

Fig. S5.

Foreign genes implicated in stress tolerance have been transferred into the H. dujardini genome. Cladograms show the evolutionary relationships between foreign H. dujardini (gray), bacterial (orange), and metazoan (blue) genes implicated in stress tolerance. Numbers on branches indicate Bayesian followed by bootstrap (500) supports. recA, DNA recombination and repair A; spds, spermidine synthase.

Genes encoding enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of polyamines (small polycationic molecules known to be up-regulated during stress in plants that, among other roles, help protect membranes) have also been supplemented through acquisitions of foreign DNA. The polyamine spermidine is produced by the enzyme spermidine synthase. There are 15 spermidine synthase-encoding genes in the H. dujardini genome: 10 metazoan and five horizontally acquired (Fig. S5).

Heat shock proteins are molecular chaperones implicated in a number of stress responses (21). Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) has been implicated in a number of stress responses specifically in tardigrades, including desiccation, radiation exposure, and heat stress (22). Of the 66 genes with hsp70 domains, 9 are from foreign sources (Fig. S5).

The various stresses tardigrades are known to tolerate cause the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, damaged DNA, denaturation of proteins, and disruption of membrane integrity. In sum, our data suggest that foreign genes, whose classic role(s) are the tolerance of these stresses, have been transferred into the genome of H. dujardini from bacteria, expanding or, in some cases, replacing endogenous gene families.

Our results demonstrate that an animal genome can be composed of a much greater proportion of horizontally transferred genes than was expected. Genes of foreign origin within the tardigrade genome are physically linked to animal genes (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3), have acquired introns (Fig. 3B), and have undergone codon optimization closely mirroring the codon use of metazoan genes in the tardigrade genome (Fig. 3A). Our evidence for the distribution of foreign genes throughout the genome assembly (Fig. 1D) and the diversity of apparent sources (Dataset S1) lead us to speculate that these horizontal transfers did not take place en masse but rather accumulated over evolutionary time.

Before this study, the animal with the highest known degree of HGT was A. ricciae, a bdelloid rotifer in which 8–9% of genes appear to have been acquired from foreign sources (14). Tardigrades and rotifers also comprise two of the only five animal clades known to survive desiccation, along with some arthropods, nematodes, and the eggs of certain flatworms (23). Comparison of all 39,532 predicted H. dujardini protein sequences with all 28,937 available A. ricciae rotifer mRNA sequences revealed 4,197 putative orthologs, reciprocal best BLAST hits with an excepted value (e-value) less than or equal to 1E-10. For just 3.5% (148) of these gene pairs, both genes appear to have been horizontally transferred into H. dujardini and A. ricciae (based on HGT index; Dataset S5). This overlap comprised genes encoding putative antioxidant enzymes, including a superoxide dismutase and GST as well as a putative Ku DNA damage repair protein and a putative hsp70 in each organism (Dataset S5). Such stress-related genes shared between H. dujardini and A. ricciae are likely to have been acquired through separate HGT events, because the majority (139 of 148) of genes were more closely related to genes from distinct nonmetazoan species than to each other (Dataset S5). For example, a gene predicted to encode a glutathione synthase in tardigrades appears to be derived from bacteria, whereas the glutathione synthase gene in rotifers is derived from fungi. It appears that rotifers and tardigrades have independently acquired and retained at least some similar genes that may contribute to stress tolerance.

It has been proposed that bdelloid rotifers are ancient asexual and ameiotic organisms, and that HGT serves as a source of genetic diversity in the absence of sex (24, 25). Although our laboratory cultures of H. dujardini are, to our knowledge, completely parthenogenic, consisting exclusively of females, males of the species and the genus Hypsibius have been reported (26) and meiosis occurs in H. dujardini (27), suggesting that a high degree of HGT may be a common feature of animals that survive desiccation rather than animals that lack sex and meiosis.

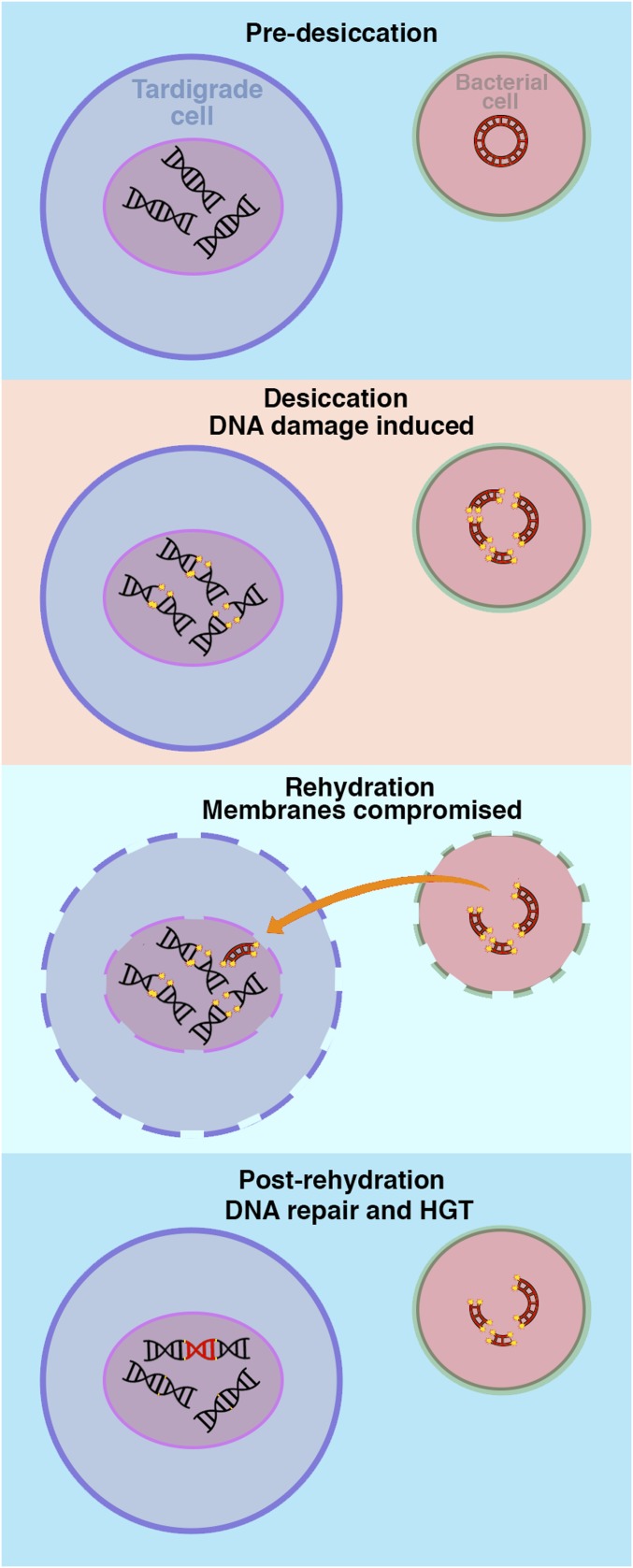

It has recently been proposed that in typical eukaryotes, horizontal transfer of genes is mediated, in large part, through endosymbiosis (28). Desiccation-tolerant organisms might be unusually susceptible to taking up and incorporating foreign DNA into their genomes from their environment rather than exclusively from endosymbionts (Fig. S6): When desiccated membranes are rehydrated, they become transiently leaky, making the uptake of large macromolecules possible (29), which has been exploited previously to introduce large nucleic acids and drugs into the cytoplasm of rehydrating anhydrobiotic cells (30–32). In addition, when tardigrades, rotifers, and other anhydrobionts desiccate, genomic double-stranded breakages and other damage are induced (19, 33, 34), and there appear to be robust mechanisms for repairing this damage (19, 34). We speculate that desiccation and associated membrane leakiness and DNA breakages might predispose these animals to take up and incorporate foreign material in their genomes (Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

Model of HGT in desiccation-tolerant organisms. Speculative model of HGT acquisition in desiccation-tolerant organisms. Prolonged desiccation induces dsDNA breaks. During rehydration, membranes become transiently leaky, allowing the transfer of large macromolecules into and out of cells, including fragmented foreign DNA. Anhydrobiotic organisms possess robust DNA repair mechanisms for fixing desiccation-induced DNA damage. If foreign DNA is present in the nucleus of an anhydrobiotic cell, it may be accidentally incorporated during postrehydration genomic repair.

SI Text

Repetitive Sequences in the H. dujardini Genome.

A total of 4,440 (10.72%) of the PacBio contigs, making up 7.91% of the assembled sequence, do not have direct homologous matches in the Illumina assembly. These contigs may represent highly repetitive sections of the genome that are difficult to assemble with short Illumina reads, or they may be misassemblies of the PacBio data due to the inherently high rate of sequencing error (10–15%). To try to resolve this question, we aligned the Illumina reads used to create our assembly to all assembled PacBio contigs using Bowtie 2. Alignment of our Illumina assembly to our PacBio assembly showed that the average coverage of the differential PacBio contigs is ∼66% of the average coverage across all PacBio contigs, indicating that these sequences are represented in the raw Illumina data but are likely repetitive, and therefore very difficult to assemble accurately.

Tandem repeats (39) (at least 2 bp × 10) were found within 20 bp of the ends of 22.85% of scaffolds. Combined with the larger scale repetitive sequence suggested by our PacBio sequencing, these results indicate that these elements are widespread and a significant hindrance to genome assembly.

Distribution of Foreign DNA Among Scaffolds.

Although, on average, the distribution of foreign genes is approximately the same through our assembly, looking at individual scaffolds, one can see that there is a bias for smaller scaffolds having either 100% HGT genes or 0% HGT genes (Fig. S2E). This bias is due to smaller scaffolds having fewer genes on them, and this bias decreases with increasing minimal gene per scaffold number (Fig. S2F). So, when comparing scaffolds with at least one gene with scaffolds with at least 10 genes, one can see a trend toward a more ubiquitous distribution of foreign genes as minimal gene count is increased.

Experimental Procedures

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation.

Short insert mate pair and Moleculo long-read libraries were generated from DNA extracted from H. dujardini. Assembly was performed with the Celera assembler, version 8.1 (35), largely following the method of McCoy et al. (36). Annotations for the H. dujardini genome assembly were generated using the automated genome annotation pipeline MAKER (16, 37, 38). Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

HGT Index Calculation and Validation.

HGT index scores were calculated as described by Boschetti et al. (14). Maximum likelihood and Bayesian supports were calculated for gene trees to complement HGT index score predictions. Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

SI Experimental Procedures

Genome and Transcriptome Sequences.

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession LMYF00000000. The version described in this paper is version LMYF01000000.

Tardigrade Culture and Isolation.

Tardigrade cultures were maintained using spring water and Chlorococcum algae (Sciento) as previously described (9). For large-scale culture, H. dujardini cultures were grown at room temperature in 10-L plastic carboys filled to 5 L with deionized water. Carboys were inoculated with Chlorococcum algae, which served as a food source for the water bears. To separate tardigrades from their algal food source for DNA and RNA isolations, carboys were shaken to suspend algal sediment evenly and this solution was decanted into 150-mm glass Petri dishes. Petri dishes were placed near a bright window, but out of direct sunlight. It has previously been observed that H. dujardini move away from sunlight. After the suspended sediment had settled on the bottom of the dish, a glass pipette was used to clear algae from the edge of the dish furthest from the window. The dish was monitored over a week until visible accumulation of tardigrades could be seen in this cleared area. Using a glass pipette, tardigrades were collected and transferred to a 50-mL beaker filled with deionized water. Tardigrades were allowed to settle to the bottom of the beaker for 2 h, and the majority of the water was then removed from the beaker without disturbing the tardigrades. The beaker was again filled with deionized water to wash the tardigrades. This washing procedure was repeated an additional two times. Following the final wash, tardigrades were allowed to settle and were left overnight at room temperature.

DNA Extraction.

Isolated specimens were transferred to 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 16,837 × g for 2 min to pellet animals. Excess liquid was removed, and tubes with pelleted specimens were dipped in liquid nitrogen and simultaneously homogenized with plastic pestles and then left briefly to thaw. Freeze/thaw douncing was repeated five times to homogenize samples. To isolate genomic DNA, homogenized samples were processed with Qiagen’s DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (catalog no. 69506) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following isolation, genomic DNA was ethanol-precipitated.

Assessment of EST and Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach Representation in the Genome.

All available H. dujardini ESTs were obtained from the GenBank. The BLAST-like alignment tool (BLAT) was used to find matches between H. dujardini ESTs and our sequencing datasets. Resulting BLAT files were used with baa.pl (40).

Core eukaryotic genes mapping approach analysis was performed as previously described (10).

Assessment of Redundancy Within the Genome.

BLAT analysis using baa.pl was performed as described above, comparing all predicted protein sequences from the H. dujardini genome annotation with assembled scaffolds.

Genomic Library Preparation and Sequencing.

Short insert mate pair libraries.

Genomic DNA libraries were constructed by Cofactor Genomics according to the following procedure. Briefly, genomic DNA was sheared to the desired size using a Covaris S2 instrument. Three libraries were constructed with the following insert sizes; 300 bp, 500 bp, and 800 bp. Following shearing, DNA was end-repaired and A-tailed to prepare for adaptor ligation. Indexed adaptors were ligated to sample DNA, and the adaptor-ligated DNA was then size-selected on a 2% SizeSelect E-Gel (Invitrogen) and amplified by PCR. Library quality was assessed by measuring nanomolar concentration and the fragment size in base pairs. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform with a 2 × 100 paired-end read configuration.

Moleculo long-read library preparation.

Isolated DNA was submitted to Illumina for preparation and sequencing using the “long-read” DNA sequencing service. Resulting sequences were assembled into long reads by Illumina.

PacBio library preparation and sequencing.

Quantity and quality were assessed using an Invitrogen Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and an Experion instrument (Bio-Rad). DNA was purified using Agencourt AMPure beads (Beckman Coulter). DNA (∼10 μg) was further prepared for sequencing using a PacBio 10-kb Preparation Kit (Pacific Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Five single molecule real-time (SMRT) cells were run using the P6-C4 chemistry and a 1 × 240 movie at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill High-Throughput Sequencing Facility.

Genomic Sequence Assembly.

Assembly was performed with the Celera assembler, version 8.1 (35). Long reads were first converted from a Fastq to Celera Assembler format with the command “fastqToCA -libraryname Hd -technology moleculo -reads LongRead.fastq > lr.frg.” The assembler was then run with the following parameters [largely following the method of McCoy et al. (36)]: unitigger = bogart merSize = 31 ovlMinLen = 2,000 utgGraphErrorRate = 0.03 utgMergeErrorRate = 0.045 obtErrorRate = 0.03 obtErrorLimit = 4.5 ovlMerSize = 31 ovlErrorRate = 0.03 batThreads = 24 cnsConcurrency = 12 frgCorrConcurrency = 12 frgCorrThreads = 12 mbtConcurrency = 12 merOverlapperThreads = 12 merylThreads = 12 ovlConcurrency = 12 ovlCorrConcurrency = 12 ovlThreads = 12. The resulting contigs and unplaced unitigs were then \scaffolded using the 300-bp, 500-bp, and 800-bp mate pair libraries with SSPACE, version 2.0 (41), and the command-line parameters: -l = libfile.txt -s = Longreads.fasta -b = Hd -x = 1 -z = 0 -k = 4 -a = 0.7 -n = 15 -T = 24 -p = 1 -o = 20 -t = 0 -m = 32 -r = 0.9.

Genomic Annotation.

Annotations for the H. dujardini genome assembly were generated using the automated genome annotation pipeline MAKER (16, 37, 38), which aligns and filters EST and protein homology evidence, identifies repeats, produces ab initio gene predictions, infers 5′ and 3′ UTRs, and integrates these data to produce final downstream gene models, along with quality control statistics.

Inputs for MAKER included the H. dujardini genome assembly, H. dujardini ESTs, a tardigrade-specific repeat library made with RepeatModeler (42) based on the reference genome assembly, and a protein database combining the UniProt/Swiss-Prot (43, 44) protein database and all sequences for D. melanogaster and C. elegans from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) protein database (45). Ab initio gene predictions were created by MAKER using the programs SNAP (46) and Augustus (47). A total of three iterative runs of MAKER were used to produce the final gene set.

Following genome annotation, final gene models were then analyzed using the program InterProScan (48) to identify putative protein domains. The final annotation set contained a total of 38,145 genes, 67% of which contain a protein domain as detected by InterProscan and 92% of which have an annotation edit distance less than 0.5, consistent with a well-annotated genome (16, 38, 49).

Taxonomic Evaluation.

The top hit to NCBI’s nr protein database was determined for each predicted gene using blastp (50). GenInfo Identifier numbers for these hits were used as input for the Galaxy fetch taxonomy tool (51, 52). Taxonomic ranks derived from this tool were used for downstream analysis.

Analysis of Putative rRNA Contamination.

All available bacterial rRNA sequences were downloaded from the Ribosomal Database Project (rdp.cme.msu.edu/) and used to perform reciprocal best-hit BLAST analysis against scaffolds in our genome assembly. Sequences with reciprocal best BLAST hits to rRNA sequences with an expected value (e-value) of less than 1E-10 were counted as putative bacterial rRNA contamination (Dataset S1).

Analysis of Putative Human Contamination.

All predicted proteins from the H. dujardini genome were used as search queries against a human protein database obtained from the NCBI. Twenty-one reciprocal best BLAST hits were found and further analyzed to assess if these sequences are truly of human origin. The 21 sequences were BLASTed against a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) proteins database (NCBI), and the e-value of each hit was used to gauge the human (or nonhuman) origin of the sequences. In all cases, the chimpanzee sequences resulted in a lower e-value, indicating that these sequences are likely not of human origin (Dataset S1).

HGT Index Calculation.

An HGT index score was calculated for each predicted gene with a top blastp hit to a nonmetazoan sequence. As previously described, a custom metazoan BLAST protein database was constructed and used to perform blastp searches, and HGT indices were calculated by subtracting the bit-score of the top metazoan BLAST hit from the bit-score of the top nonmetazoan BLAST hit for a given gene, with a threshold of 30 used to indicate likely HGT for a gene (14). All BLAST searches were carried out using the BLOSUM62 matrix.

Gene Tree Construction and Analysis.

Alignments for phylogenetic analysis were compiled by blasting predicted protein sequences of prospective horizontally transferred genes against the NCBI nr database. One hundred cases were chosen at random (SI Experimental Procedures, Bridged PCR). The top five hits from metazoa, fungi, Embryophyta (multicellular plants), single-celled eukaryotes, Archaea, and Eubacteria were used for alignment, except when probable homologs were not present in a lineage. Sequences were aligned with MUSCLE (53) and edited by eye. Alignments were trimmed using the bioinformatics program gBlocks (54) and by eye. Both maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches were used for phylogenetic analyses, implementing the Le-Gascuel (LG) model (55), with an estimated proportion of invariable sites and an estimated gamma shape parameter. PhyML (56) was used to determine maximum likelihood tree topologies, with 500 bootstrap replicates to evaluate branch supports. The Bayesian analysis was performed in MRBAYES (57), which ran for between 600,000 and 3,600,000 generations, depending on when convergence occurred, and sampled every 100 generations. For each maximum likelihood tree, posterior probability branch support estimates were calculated from the last 4,500 trees of the posterior distribution of trees sampled during the Bayesian analysis.

Bridged PCR.

Genomic coordinates for adjacent genes were obtained from the MAKER2 output general feature format (gff) file. A numbered list of all foreign genes within 4,000 bases (for efficient PCR) of another gene was constructed. This list was split into sublists based on the predicted origin of foreign genes (bacterial, plant, fungi, archaeal, viral), and test candidates were selected for PCR using a random number generator to select genes from each of these sublists. A forward primer was designed within the last 200 bases of the upstream gene, and a corresponding reverse primer was designed within the first 200 bases of the downstream gene. Primer sequences and genomic coordinates used in this study are reported in Dataset S2. Primer sets were used in conjunction with single tardigrade PCR (discussed below). Following PCR, products were run on 1% ethidium bromide agarose gels to confirm the correct amplicon length.

Single Tardigrade PCR.

A single adult tardigrade was transferred from an active culture to a dish of deionized water. The tardigrade was pipetted up and down in autoclaved deionized water with the mouth pipette several times to wash it. The cleaned tardigrade was transferred to the open lid of a 0.2-mL PCR tube. Five microliters of single tardigrade lysis solution [51 mM KCL, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.45% Nonidet P-40, 0.45% Tween-20, 0.01% gelatin, and 100 μg/mL proteinase K] was added to the bottom of each tube. Tubes were capped and centrifuged briefly to transfer the tardigrade from the cap to the lysis solution. Immediately following centrifugation, PCR tubes were transferred to −80 °C for 20 min. Following freezing, PCR tubes were placed in a thermocycler and heated at 65 °C for 60 min, followed by 80 °C for 15 min.

Lysates were used for PCR using either 2× GOtaq Master Mix (Promega) or LongAmp taq (New England BioLabs), both according to each manufacturer’s instructions. Touchdown PCR was used, starting with an annealing temperature of 70 °C and decreasing to 52 °C at −1 °C per cycle. Subsequent to touchdown cycles, an additional 30 cycles of PCR were performed at 52 °C. Extension times used were calculated based on the expected amplicon length and the manufacturer’s instructions.

Intron Splice Site Sequence Analysis.

U2 spliceosomal introns are characterized by a conserved GT dinucleotide at their 5′ splice site and a conserved AG dinucleotide at their 3′ splice site. The sequence 10 bases upstream and downstream of conserved dinucleotide was obtained manually for 50 introns present in genes of bacterial origin in the H. dujardini genome (Dataset S3). For comparison, the same procedure was used for 20 introns present in genes of metazoan origin in the H. dujardini genome (Dataset S3). Sequences were used as input for Galaxy’s Sequence Logo Motif tool (51, 52).

Codon Use.

For codon use analysis, the full predicted coding sequence of 50 randomly selected genes was obtained for genes in the H. dujardini genome of metazoan, as well as foreign, origin. In addition, the full predicted coding sequence of 50 randomly selected genes obtained from the NCBI was obtained for the two most prevalent bacterial species represented in the H. dujardini genome (Niastella koreensis and Fluviicola taffensis; Dataset S1). These sequences were used for input into the sequence manipulation suite codon use calculator (58), and the frequency of codon use for each dataset was compared. Sequences used for this analysis are available in Dataset S3.

Gene/Protein Family and Gene Ontology Analysis.

InterPro and gene ontology gene ontology identifiers were parsed from the MAKER gff output. The occurrence of each unique IPR identifier was counted (Dataset S4). To compare counts of IPR domains in the H. dujardini genome, we obtained count data for both C. elegans and D. melanogaster from the InterProScan website (www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/interproscan.html).

PacBio Genome Assembly.

We used the minhash alignment process (biorxiv.org/content/early/2014/08/14/008003) to perform alignment and self-correction of PacBio subreads. PacBio self-correction reduced read error 10-fold from an estimated 15% to 1.5% after correction. We then assembled the corrected PacBio reads using the Celera assembler.

We also performed a hybrid assembly using a strict overlap-layout-consensus method that combined our original data and the PacBio data. Although this approach marginally improved the assembly (higher N50, more EST mapped to contigs), it did not significantly improve our original assembly and added a new complication by introducing data from a new set of animals into the analysis. Intriguingly, we noted that contigs produced by all three assemblies tended to fail (i.e., end) at similar points, suggesting that current assembly algorithms may not be sufficient for assembling these regions regardless of data type.

After ∼20-fold coverage PacBio sequencing of DNA from a new set of individuals, we performed self-correction and assembly of the PacBio data. Because PacBio has a high per base error rate, ∼20-fold is not sufficient to assemble a whole genome de novo from PacBio data. However, the high-quality contigs generated by these data can be compared with the original assembly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Chalfie, W. Marshall, D. Weisblat, S. Ahmed, G. Wray, M. Srivastava, and members of the B.G. laboratory for comments. This work was funded by National Science Foundation Grant IOS 1257320 (to B.G.), National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grant 14-14SF_Step2-0019 (to T.C.B.), National Institute of General Medical Science Grant K12GM000678 (to J.R.T.), and North Carolina Biotechnology Center Grant 2013-MRG-1110 (to C.D.J.), and by contributions from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Integrative Program for Biological and Genome Sciences, Carolina Center for Genome Sciences, and Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database (accession no. LMYF00000000). The version described in this paper is version LMYF01000000.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1510461112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kinchin IM. The Biology of Tardigrades. Portland Press; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JC. Cryptobiosis 300 years on from van Leuwenhoek: What have we learned about tardigrades? Zool Anz. 2001;240(3-4):563–582. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becquerel P. La suspension de la vie au dessous de 1/20 K absolu par demagnetization adiabatique de l’alun de fer dans le vide les plus elève. CR Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1950;231:261–263. French. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahm PG. Biologische und physiologische Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Moosfauna. Zeitschrift Allg Physiologie. 1921;20:1–35. German. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jönsson KI, Harms-Ringdahl M, Torudd J. Radiation tolerance in the eutardigrade Richtersius coronifer. Int J Radiat Biol. 2005;81(9):649–656. doi: 10.1080/09553000500368453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horikawa DD, et al. Analysis of DNA repair and protection in the Tardigrade Ramazzottius varieornatus and Hypsibius dujardini after exposure to UVC radiation. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e64793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramløv H, Westh P. Cryptobiosis in the Eutardigrade Adorybiotus (Richtersius) coronifer: Tolerance to alcohols, temperature and de novo protein synthesis. Zool Anz. 2001;240(3-4):517–523. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jönsson KI, Rabbow E, Schill RO, Harms-Ringdahl M, Rettberg P. Tardigrades survive exposure to space in low Earth orbit. Curr Biol. 2008;18(17):R729–R731. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabriel WN, et al. The tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini, a new model for studying the evolution of development. Dev Biol. 2007;312(2):545–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: A pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(9):1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Grohme MA, Mali B, Schill RO, Frohme M. Towards decrypting cryptobiosis--analyzing anhydrobiosis in the tardigrade Milnesium tardigradum using transcriptome sequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salzberg SL, White O, Peterson J, Eisen JA. Microbial genes in the human genome: Lateral transfer or gene loss? Science. 2001;292(5523):1903–1906. doi: 10.1126/science.1061036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanhope MJ, et al. Phylogenetic analyses do not support horizontal gene transfers from bacteria to vertebrates. Nature. 2001;411(6840):940–944. doi: 10.1038/35082058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boschetti C, et al. Biochemical diversification through foreign gene expression in bdelloid rotifers. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(11):e1003035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy SW, Gilbert W. The evolution of spliceosomal introns: Patterns, puzzles and progress. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(3):211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt C, Yandell M. MAKER2: An annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.França MB, Panek AD, Eleutherio ECA. Oxidative stress and its effects during dehydration. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2007;146(4):621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebecchi L, Cesari M, Altiero T, Frigieri A, Guidetti R. Survival and DNA degradation in anhydrobiotic tardigrades. J Exp Biol. 2009;212(Pt 24):4033–4039. doi: 10.1242/jeb.033266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann S, Reuner A, Brümmer F, Schill RO. DNA damage in storage cells of anhydrobiotic tardigrades. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2009;153(4):425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.04.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman MF, Woodgate R. Translesion DNA polymerases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(10):a010363. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsell DA, Lindquist S. The function of heat-shock proteins in stress tolerance: Degradation and reactivation of damaged proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27(1):437–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jönsson KI, Schill RO. Induction of Hsp70 by desiccation, ionising radiation and heat-shock in the eutardigrade Richtersius coronifer. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;146(4):456–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe M. Anhydrobiosis in invertebrates. Appl Entomol Zool (Jpn) 2006;41(1):15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flot JF, et al. Genomic evidence for ameiotic evolution in the bdelloid rotifer Adineta vaga. Nature. 2013;500(7463):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gladyshev EA, Meselson M, Arkhipova IR. Massive horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers. Science. 2008;320(5880):1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1156407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidetti R, Colavita C, Altiero T, Bertolani R, Rebecchi L. Energy allocation in two species of Eutardigrada. J Limnol. 2007;66(Suppl 1):111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammerman D. The cytology of parthenogenesis in the tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini. Chromosoma. 1967;23(2):203–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00331113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ku C, et al. Endosymbiotic origin and differential loss of eukaryotic genes. Nature. 2015;524(7566):427–432. doi: 10.1038/nature14963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leopold AC, Musgrave ME, Williams KM. Solute leakage resulting from leaf desiccation. Plant Physiol. 1981;68(6):1222–1225. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.6.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boothby TC, Wolniak SM. Masked mRNA is stored with aggregated nuclear speckles and its asymmetric redistribution requires a homolog of Mago nashi. BMC Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boothby TC, Zipper RS, van der Weele CM, Wolniak SM. Removal of retained introns regulates translation in the rapidly developing gametophyte of Marsilea vestita. Dev Cell. 2013;24(5):517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolniak SM, Boothby TC, van der Weele CM. Posttranscriptional control over rapid development and ciliogenesis in Marsilea. Methods Cell Biol. 2015;127:403–444. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rebecchi L, et al. Tardigrade Resistance to Space Effects: First results of experiments on the LIFE-TARSE mission on FOTON-M3 (September 2007) Astrobiology. 2009;9(6):581–591. doi: 10.1089/ast.2008.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gladyshev E, Meselson M. Extreme resistance of bdelloid rotifers to ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(13):5139–5144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800966105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers EW, et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science. 2000;287(5461):2196–2204. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy RC, Garud NR, Kelley JL, Boggs CL, Petrov DA. Genomic inference accurately predicts the timing and severity of a recent bottleneck in a nonmodel insect population. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(1):136–150. doi: 10.1111/mec.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantarel BL, et al. MAKER: An easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18(1):188–196. doi: 10.1101/gr.6743907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yandell M, Ence D. A beginner’s guide to eukaryotic genome annotation. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(5):329–342. doi: 10.1038/nrg3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan JF. Baa.pl: A tool to evaluate de novo genome assemblies with RNA transcripts. 2013;arXiv:1309.2087. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(4):578–579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smit AFA, Hubley R. 2010 RepeatModeler Open-1.0. Available at www.repeatmasker.org/. Accessed July 31, 2015.

- 43.O’Donovan C, et al. High-quality protein knowledge resource: SWISS-PROT and TrEMBL. Brief Bioinform. 2002;3(3):275–284. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UniProt Consortium The universal protein resource (UniProt) in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D142–D148. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Klimke W, Maglott DR. NCBI Reference Sequences: Current status, policy and new initiatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanke M, Steinkamp R, Waack S, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: A web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W309–W312. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunter S, et al. InterPro: The integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eilbeck K, Moore B, Holt C, Yandell M. Quantitative measures for the management and comparison of annotated genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giardine B, et al. Galaxy: A platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 2005;15(10):1451–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy Team Galaxy: A comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010;11(8):R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56(4):564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Le SQ, Gascuel O. An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(7):1307–1320. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guindon S, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(8):754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stothard P. The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques. 2000;28(6):1102–1104. doi: 10.2144/00286ir01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.