Abstract

Background

Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have increasingly been providing more therapy hours to beneficiaries of Medicare. It is not known whether these increases have improved patient outcomes.

Objective

The study objectives were: (1) to examine temporal trends in therapy hour volumes and (2) to evaluate whether more therapy hours are associated with improved patient outcomes.

Design

This was a retrospective cohort study.

Methods

Data sources included the Minimum Data Set, Medicare inpatient claims, and the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting System. The study population consisted of 481,908 beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service who were admitted to 15,496 SNFs after hip fracture from 2000 to 2009. Linear regression models with facility and time fixed effects were used to estimate the association between the quantity of therapy provided in SNFs and the likelihood of discharge to home.

Results

The average number of therapy hours increased by 52% during the study period, with relatively little change in case mix at SNF admission. An additional hour of therapy per week was associated with a 3.1-percentage-point (95% confidence interval=3.0, 3.1) increase in the likelihood of discharge to home. The effect of additional therapy decreased as the Resource Utilization Group category increased, and additional therapy did not benefit patients in the highest Resource Utilization Group category.

Limitations

Minimum Data Set assessments did not cover details of therapeutic interventions throughout the entire SNF stay and captured only a 7-day retrospective period for measures of the quantity of therapy provided.

Conclusions

Increases in the quantity of therapy during the study period cannot be explained by changes in case mix at SNF admission. More therapy hours in SNFs appear to improve outcomes, except for patients with the greatest need.

Approximately 1.7 million beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service receive care in nearly 15,000 skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) annually.1 Medicare spending on SNF services increased from $13.6 billion in 2001 to $28.7 billion in 2012, making SNF services among the fastest growing components of Medicare expenditures.2 These rapid increases in the use of SNF services may be due, in part, to declining hospital length of stay and Medicare reimbursement policies.3,4

Medicare's prospective payment system for hospitals has incentivized shorter length of stay, which may have led to the substitution of SNF services for inpatient care. Unlike the approach of other Medicare payment structures, such as the episode-based system for home health services and the diagnosis-related group–based model for acute hospital care, days are used as the unit of payment for SNFs. Per diem reimbursements also are adjusted for the number of therapy minutes provided to patients. As indicated by a recent study5 and a report from the Office of Inspector General,6 SNFs have increasingly moved patients into higher payment categories, leading to more hours of therapy without a substantial rise in case mix. It is not known whether increases in the quantity of therapy provided to patients in SNFs improve outcomes.

Research that directly examines the quantity of therapy provided to patients in SNFs and rehabilitation outcomes is scarce. Two studies examined this relationship and showed that the amount of therapy was positively associated with improvements in patients' functional independence and increased the likelihood of patients being discharged to the community.7,8 However, these studies were limited to patients who were covered by Medicare Advantage plans and who received SNF care in one region.7,8 Research focusing solely on the association between the intensity of therapy and outcomes also is limited. Two studies examined the relationship between therapy intensity and outcomes for patients who had orthopedic impairments and who received comprehensive acute rehabilitation9 and subacute rehabilitation;10 both studies also showed a positive relationship between more therapy hours and functional improvements.

The ultimate goals of SNF treatment are regaining functional independence and decreasing impairments through appropriate rehabilitation treatment and discharge to the community. However, it is not clear whether the large documented increases in SNF services provided during the last decade or more have translated into superior outcomes for beneficiaries of Medicare. The purposes of this study were: (1) to describe temporal trends in the quantity of rehabilitation therapy provided to patients with hip fracture in SNFs and (2) to examine whether increases in the quantity of therapy have been accompanied by improvements in patient outcomes, as measured by the likelihood of discharge to home. We focused on hip fracture because it is one of the most common diagnoses associated with admission to SNFs and because it is a large contributor to Medicare spending on postacute care.11–13

Method

Data Source

The data source for this study was a longitudinal file that merged the Minimum Data Set (MDS), Medicare inpatient claims, and the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting System (OSCAR) for years 2000 through 2009. The MDS provided resident-level data, and the OSCAR provided facility-level data. Demographic and clinical characteristics of residents were obtained from the first MDS assessment completed after admission from a hospital. The MDS Resident Assessment Instrument is federally mandated for all residents of nursing homes and contains nearly 400 data elements on demographic information, diagnoses, and measures of physical and cognitive functional status. The MDS also provides discharge locations and dates for each resident, indicating whether the individual was discharged to home, was rehospitalized, or died in the nursing home, in addition to other dispositions. Minimum Data Set assessments are completed at admission and at least quarterly thereafter.14 The quality and reliability of variables in the MDS were previously validated.15,16 Medicare inpatient claims were used to identify diagnoses and to provide information on hospitalizations before SNF admissions. The OSCAR provided information on organizational characteristics of nursing homes (eg, proprietary status, number of beds, staffing). Maintained by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the OSCAR is an administrative database for collecting and recording the results of states' annual survey and certification processes.

Study Sample

The study population included people who were at least 65 years of age and covered by Medicare fee-for-service and who were admitted for the first time to SNFs (N=599,515). Patients with hip fracture were identified from Medicare inpatient claims on the basis of International Statistical Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision)17 code 820.xx. First-time SNF admissions from acute care hospitals were identified on the basis of the presence of an MDS admission assessment tracking record. An MDS admission record was eligible for inclusion if it occurred between 2000 and 2009. A first-time admission meant that, in the preceding year, our stream of MDS assessments from the repository had no record of the same beneficiary of Medicare having been in a nursing home anywhere in the United States. The MDS record field indicating the source of admission was used to identify patients who entered SNFs from acute care hospitals. Focusing on first-time SNF admissions after an inpatient stay helped to create a more homogeneous study population.

A total of 19,234 people who were not continuously enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service for at least 6 months before their SNF admission or who changed their insurance coverage during their SNF stay were excluded to account for the continuing effects of insurance status.18 Patients for whom discharge disposition was not indicated in the assessments (n=63,433), suggesting incomplete reporting, were not included in the study sample. Patients who stayed more than 100 days (n=32,408) were excluded to coincide with the number of days covered by the Medicare SNF benefit. Patients who stay beyond 100 days are often identified as long-term nursing home residents, and their care may differ from that of patients receiving short-term rehabilitation in SNFs.19 Patients in SNFs in Hawaii, Alaska, and the District of Columbia (n=2,020) were not included in the study because of the unique geographic and political characteristics of these markets.20 Lastly, patients in the highest 0.1 percentile of therapy minutes received (n=512) were excluded to reduce the influence of outliers. The final analytic file included 481,908 beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service who had hip fracture and who were discharged from acute care hospitals to 15,496 nursing homes. The cohort diagram is shown in the eFigure.

Measure of Therapy Quantity

The MDS documents rehabilitation therapy by noting the total number of minutes provided during an assessment period covering the preceding 7 days. We defined the mean quantity of therapy as the average number of minutes of therapy per week, on the basis of the 7-day retrospective period and all assessments from the entire SNF stay. The total number of minutes of therapy provided during each assessment period included the amounts of physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy. We summed the minutes for all 3 types of therapy and calculated the mean across all assessments. For example, if a patient had 3 assessments during the SNF stay, the patient's total therapy minutes from the 3 assessments were summed and divided by 3 to calculate the average quantity of therapy during the SNF stay.

Dependent Variables

Our primary outcome measure was the likelihood of discharge to the community within 100 days (yes/no), as derived from the MDS discharge record. Returning to the community was defined as discharge to home or to an assisted living facility, whereas rehospitalization, death in the nursing home, transfer to another nursing home, and other dispositions (eg, transfer to a psychiatric hospital) were collapsed into a single category to indicate an alternative discharge option. Our dependent variable reflects the most desirable outcome after SNF treatment, that is, people achieve functional recovery and are successfully discharged to home. Risk-adjusted rates of discharge to the community have been used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to evaluate the quality of care associated with SNF benefits.1

Explanatory Variables

Resident-level explanatory variables were obtained from each patient's initial MDS assessment. These variables included sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status) and measures reflective of the case mix at SNF admission, including a body mass index of greater than 30 kg/m2 (yes/no), a body mass index of less than 19 kg/m2 (yes/no), indicators for each of the 7 levels of the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) (0–6, with higher scores indicating more severe impairment),21 and a continuous measure of activities of daily living (ADLs) (28-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater disability).22 Other explanatory variables included the number of medications taken in the preceding 7 days and the use of any antipsychotic or hypnotic medications (yes/no).23 The presence of a do-not-resuscitate order (yes/no) was used as a proxy for patient preferences toward the use of aggressive treatment. To control for a patient's condition at admission to an SNF, a continuous measure (Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index24,25) and a binary indicator for any intensive care unit use from the preceding hospitalization, derived from Medicare inpatient claims, were included in the models.

Skilled nursing facility–level explanatory variables included time characteristics selected on the basis of previous studies of nursing home quality. These measures included occupancy rates (the number of patients occupying certified beds at the time of inspection divided by the total number of certified beds in the nursing home); the ratio of the number of registered nurses to the total number of registered nurses and licensed practical nurses; the presence of a physician extender (yes/no); the total number of physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists per 100 beds; and the percentages of residents in the nursing home who received Medicare and Medicaid. Nursing home fixed effects were included by creating a dummy variable for each facility in the sample in addition to indicators for the year and quarter of admission.19,20,26–33 The overall number of observations with missing values was less than 1%, and these observations were excluded from the analyses.

Data Analysis

To describe trends in the quantity of rehabilitation services and whether changes in quantity were accompanied by changes in patient outcomes, we created a longitudinal figure presenting the unadjusted total therapy minutes. Concurrent trends in case mix may explain changes in outcomes. Therefore, longitudinal trends for CPS and ADL scores also were examined. The average quantity of therapy, CPS score, and ADL score per patient were calculated across all SNF admissions in a given year. We also examined the average SNF length of stay at the patient level and the proportion of patients discharged to home for each year of the study period to characterize SNF use and patients' health status at discharge.

We used multivariable linear regression models with facility and time fixed effects to estimate the marginal effects of therapy quantity on residents' likelihood of discharge to the community. The use of nursing home fixed effects controlled for any time-invariant, facility-specific omitted variables associated with quality of care, such as provider variations in processes of care, heterogeneity in managerial approaches, and permanent market differences. Indicators for the year and quarter of admission adjusted for secular trends and seasonal effects on health outcomes. The identification strategy relied on within-nursing home variations over time and removed the unobserved and potentially confounding cross-sectional heterogeneity between nursing homes. Thus, our regression predicted the benefits of additional therapy in patients who resided in the same nursing home and who were admitted to the facility in the same quarter and year. Estimation with a linear probability model was used as a tractable approach given the size of our analytic file and the extensive use of dummy variables as controls.19,20 The estimated coefficients were scaled to hours for ease of interpretation.

Secondary Analyses

Analyses by type of therapy.

In secondary analyses, we derived estimates by using the quantity of occupational therapy and the quantity of physical therapy—the 2 major types of therapy—as the determinants of interest in separate regressions.

Analyses by Resource Utilization Group (RUG) category.

Next, to examine the potential for different effects in patients who needed different quantities of therapy, we derived separate regression estimates based on samples of patients in each of the 5 RUG categories. The RUG categories reflected the patient days of care adjusted for case mix.34

Sensitivity analyses.

We conducted multiple sensitivity analyses to validate the consistency of our results. First, we repeated our primary analysis with a sample that excluded residents who died before SNF discharge to account for mortality as a competing risk for returning to the community. Second, to assess whether the effect of additional therapy varied by SNF length of stay, we conducted separate sensitivity analyses with, as outcome measures, indicators for discharge to the community within 30, 60, or 90 days of admission.

Lastly, our main outcome measure included all discharge destinations other than home in one category. To test the robustness of our results, we conducted an analysis in which patients who were transferred to other facilities or returned to the hospital were excluded.

All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and Stata MP Version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Results are reported with 95% robust confidence intervals (CIs) adjusted for clustering at the level of the facility.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Health Services Research Dissertation Grant Award to Dr Jung) and the National Institute on Aging (Program Project Grant 1P01AG027296, Shaping Long-Term Care in America, Principal Investigator: Dr Mor).

Results

Characteristics of Patients

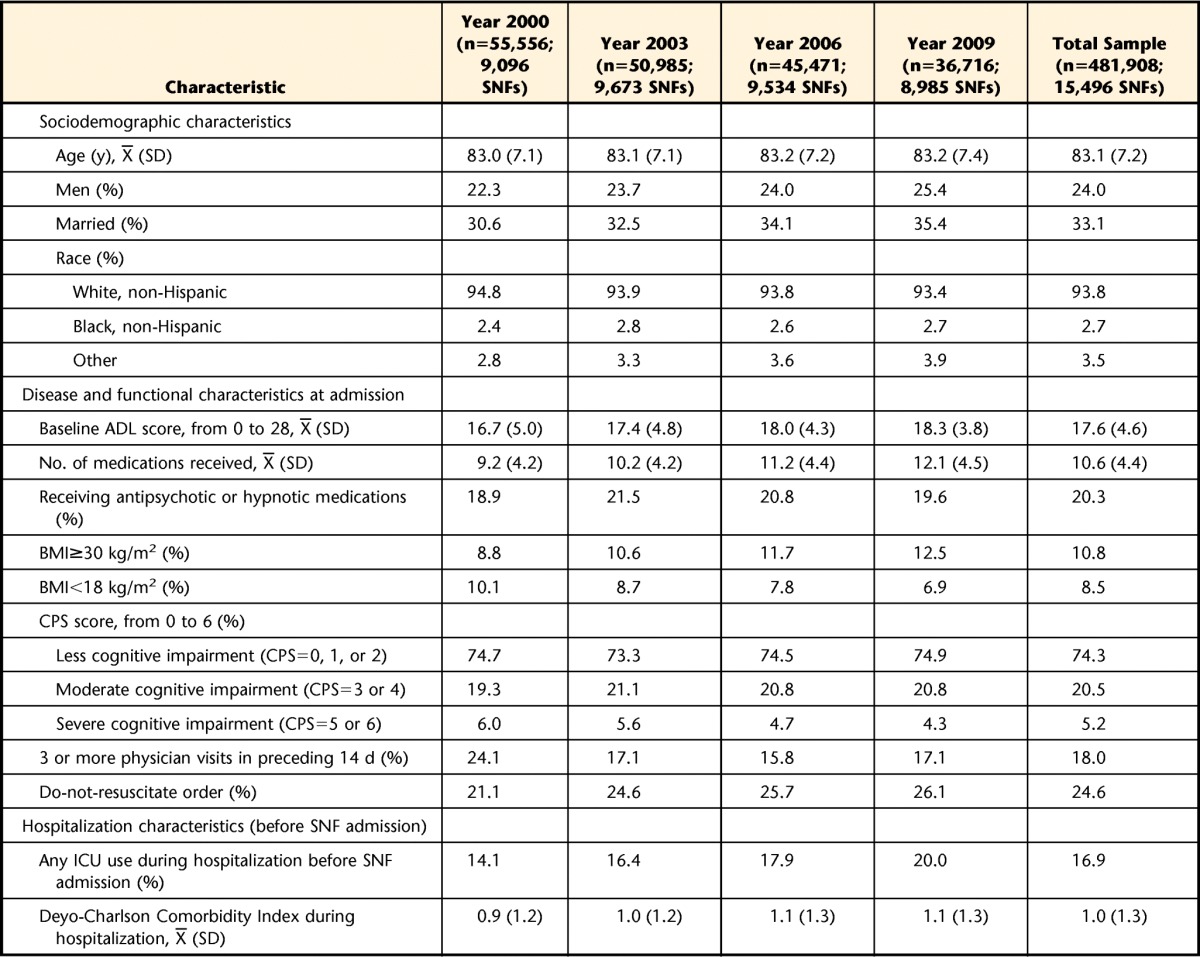

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the overall study cohort, as well as longitudinally for years 2000, 2003, 2006, and 2009. Most of the patients were white, and the mean age was 83 years. The mean ADL score at SNF admission was 18 (the maximum was 28), and more than 5% of the patients had severe cognitive impairment at SNF admission, defined as a CPS score of 5 or 6. The characteristics of hospitalizations before SNF admission showed that about 17% of the admitted patients had been treated in intensive care units; the average Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index was 1.0 and did not change between 2000 and 2009. There were no substantial changes in patient demographics over time. However, a moderate increase in the proportion of patients with intensive care unit use was observed, and there were small increases in the mean ADL score, the proportion of patients with a body mass index of greater than 30 kg/m2, and the mean number of medications received over time. The proportion of patients with 3 or more physician visits in the preceding 14 days declined during the study period.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Beneficiaries of Medicare Fee-for-Service Who Were Admitted to SNFs After Hip Fracturea

SNFs=skilled nursing facilities, ADL=activities of daily living, BMI=body mass index, CPS=Cognitive Performance Scale, ICU=intensive care unit.

Trends in Therapy Quantity and Case Mix From 2000 to 2009

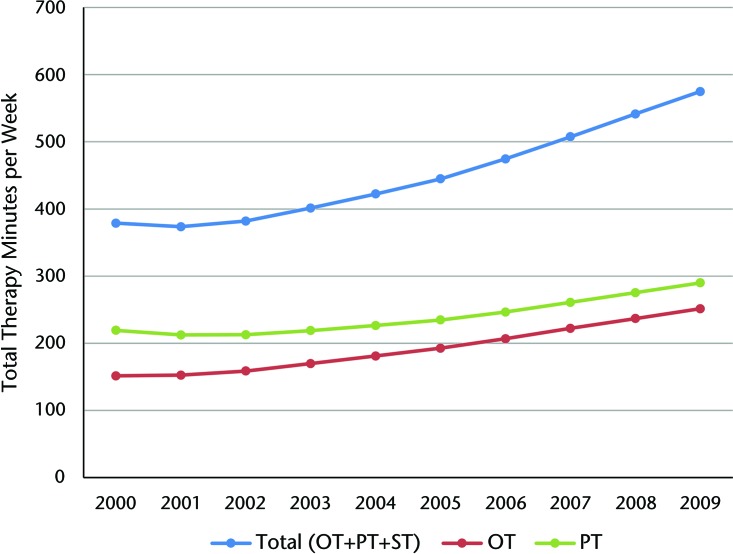

Figure 1 shows trends in the average weekly quantity of therapy per person across all SNF admissions in a given year. Clear upward trends in therapy quantity during the study period can be seen. The average number of total therapy minutes increased by more than 50%. In 2000, residents newly admitted to SNFs after hip fracture received about 379 minutes of total therapy, on average. This amount increased to 575 minutes in 2009. Among specific types of therapy, the mean number of physical therapy minutes increased more rapidly than other types, increasing 66% (from 151 minutes to 251 minutes). The mean number of occupational therapy minutes increased 32% (from 219 minutes to 290 minutes) during the study period.

Figure 1.

Total therapy minutes per week provided to beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service in skilled nursing facilities after hip fracture, from 2000 to 2009. OT=occupational therapy, PT=physical therapy, ST=speech and language therapy.

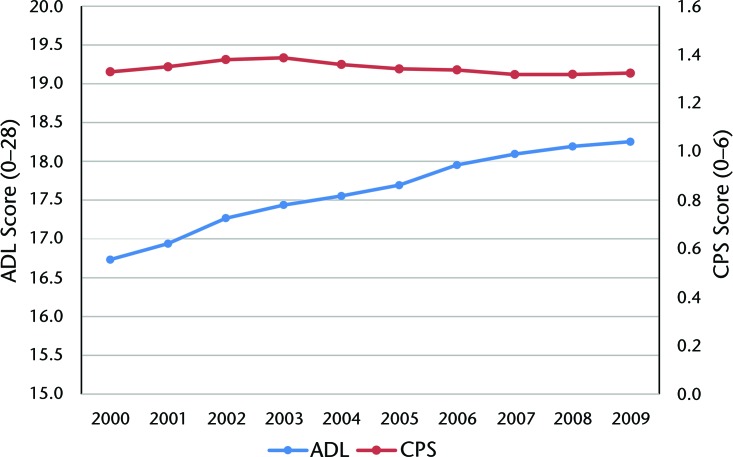

Figure 2 shows unadjusted trends in concurrent measures of residents' health status. Trends in case mix at SNF admission, measured by CPS and ADL scores, did not indicate large changes during the study period. The mean ADL score increased 1 point, from 17 in 2000 to 18 in 2009 (on a scale from 0 to 28 points). Similarly, the average CPS score (on a scale from 0 to 6 points) decreased only 0.1 point between 2000 and 2009.

Figure 2.

Case mix of beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service who were admitted to skilled nursing facilities after hip fracture, as measured by activities of daily living (ADL) and the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS), from 2000 to 2009. Activities of daily living were scored on a scale from 0 to 28 points; CPS was scored on a scale from 0 to 6 points.

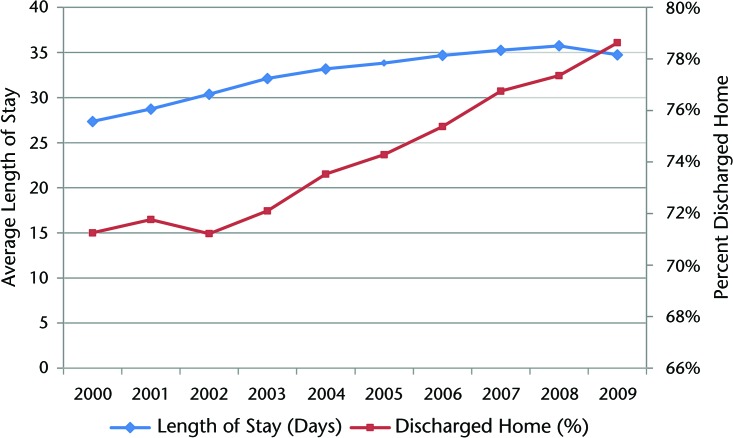

Figure 3 shows trends in the average SNF length of stay and the proportion of patients discharged to home in a given year. The length of stay increased steadily until 2006 but was relatively constant (∼35 days) between 2006 and 2009. The proportion of patients discharged to home increased from 71% in 2000 to 79% in 2009. Additional descriptive statistics, median values, and standard deviations of means associated with the annual measures in Figures 1, 2, and 3 are shown in eTables 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Average length of stay in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and the proportion of beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service who were admitted to SNFs after hip fracture and discharged to home, from 2000 to 2009.

Adjusted Association Between Quantity of Therapy and Likelihood of Discharge to Home

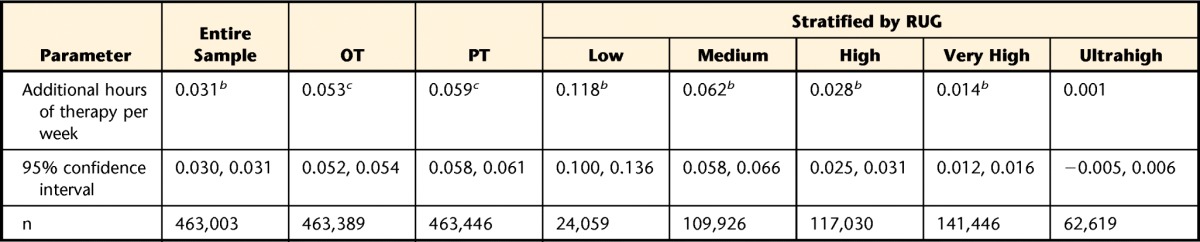

Table 2 shows the adjusted rate of discharge to home associated with an additional hour of therapy. The regression estimates suggested a positive relationship between the quantity of therapy and discharge to home after treatment in an SNF. An additional hour of therapy per week was associated with approximately a 3.1-percentage-point (95% CI=3.0, 3.1) increase in the likelihood of returning to the community.

Table 2.

Adjusted Association Between Therapy Intensity and Likelihood of Discharge to Home in Beneficiaries of Medicare Fee-for-Service Who Were Admitted to SNFs After Hip Fracturea

All models were adjusted for patient characteristics and time-varying facility characteristics. Details of the variables are described in the text. Nursing home and year-quarter fixed effects were used in all models. Minimum minutes per week for the Resource Utilization Group (RUG) categories were as follows: low (45 minutes), medium (150 minutes), high (325 minutes), very high (500 minutes), and ultrahigh (720 minutes). SNFs=skilled nursing facilities, OP=occupational therapy, PT=physical therapy.

b P<.01.

c P<.001.

The results of our secondary analyses with specific types of therapy as the determinants of interest indicated that an additional hour of occupational therapy was associated with a 5.3-percentage-point (95% CI=5.2, 5.4) increase in the likelihood of discharge to the community and that an additional hour of physical therapy was associated with a 5.9-percentage-point (95% CI=5.8, 6.1) increase in the likelihood of discharge to the community. The results of our secondary analyses stratified by RUG category also suggested a positive association between an additional hour of therapy and discharge to home, except for patients in the highest RUG category, who required the most rehabilitation. For residents who received more than 720 minutes of therapy, an additional hour of therapy was not associated with an increased likelihood of discharge to home. Likewise, the marginal effect of the quantity of therapy decreased as the RUG category increased.

The estimate from our sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who died before discharge was similar to the result from our primary analysis (2.5 percentage points; 95% CI=2.5, 2.6). Consistent with our main results, estimates from our sensitivity analyses showed a positive relationship between quantity of therapy and discharge to home after treatment in an SNF for different lengths of stay. An additional hour of therapy per week was associated with increases in the likelihood of discharge to home of 2.9 percentage points (95% CI=2.8, 2.9), 3.0 percentage points (95% CI=2.9, 3.1), and 3.0 percentage points (95% CI=3.0, 3.1) for stays of up to 30, 60, and 90 days, respectively.

Estimates from our sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who were discharged to other facilities (8.0%) or who were rehospitalized (10.3%) showed a positive association between additional therapy and discharge to home, consistent with the results of our primary analysis (excluding discharge to other facilities: 3.0 percentage points, 95% CI=2.9, 3.1; excluding patients who were rehospitalized: 2.3 percentage points, 95% CI=2.2, 2.3).

Estimated coefficients for all variables are shown in eTable 3.

Discussion

In this national study of recipients of Medicare who were admitted to an SNF directly after hospitalization for a hip fracture, we found more than a 50% increase in the quantity of therapy provided during the SNF stay and a 30% increase in the length of stay in the SNF from 2000 to 2009. As indicated by earlier reports,6,12 we also found that increases in the quantity of rehabilitation services were not explained by changes in the health status of patients with hip fracture at SNF admission. Although functional independence at SNF admission and cognitive ability declined somewhat, the magnitude of these changes was relatively small. Importantly, trends during the study period indicated that patients with hip fracture were being discharged to home at increasing frequency. Despite substantial increases in the quantity of rehabilitation services provided during the last decade, the relatively small changes in concurrent health status measures suggest that patient frailty does not largely explain the trend.

The results of our study provide insights into the potential benefit of increases in the quantity of therapy provided to patients with hip fracture in SNFs. Our findings suggest that increasing the number of hours of therapy improves outcomes for these patients, as reflected in the increased likelihood of being discharged to home. The results of our secondary analyses indicated that this relationship was true for both occupational therapy and physical therapy. Our sensitivity analyses indicated that the association between increased therapy and discharge to home was strongest for patients in lower RUG categories and was not apparent for those in the highest RUG category.

Our study makes novel contributions to the literature. First, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first nationwide examination of changes in the provision of therapy in SNFs during a 10-year period. Second, our study included an expansive set of patient and SNF characteristics that allowed for estimates of the relationship between the quantity of therapy provided and the likelihood of discharge to home that were more robust than those reported in the literature to date.

The observed association between an additional hour of therapy and the likelihood of being discharged to home is consistent with the results of earlier studies, supporting the benefits of more therapy hours, to a certain point.7,8 Although it is unlikely that the large increase in therapy hours provided to patients with hip fracture during the course of a decade is solely responsible for the large increase in the percentage of these patients being discharged to home, our estimate of a 3-percentage-point increase in the likelihood of being discharged to home for every additional hour of therapy suggests the possibility that the increased duration of therapy services was an important contributor to the increased rate of discharge to home for patients after hip fracture. From 2000 to 2009, the average number of therapy hours increased from approximately 6.3 to 9.6. On the basis of the results obtained with our model, this value translates to a 10.2-percentage-point increase in the likelihood of discharge to home—more than the observed increase of about 8 percentage points (from 71% to 79%). Because the length of SNF stays increased during this time and because of enhancements in other aspects of SNF care and the growing availability of home- and community-based services,35 it is impossible to determine how much of the observed improvement in outcomes was attributable exclusively to more therapy time. It also is possible that some of the increase in the provision of therapy in SNFs was due to postacute care being substituted for inpatient care because hospital length of stay declined during the study period. Nonetheless, because the characteristics of patients admitted to SNFs after hip fracture did not change during the study period, it is plausible that at least some of the improvement in discharge disposition was attributable to the increased quantity of therapy provided to patients in SNFs in the last decade.

Payers, providers, and policy makers have a strong interest in the quality and efficiency of postacute care in SNFs. A recent report from the Institute of Medicine noted that postacute care is the largest driver of regional variations in health care costs in the United States.36 As providers are increasingly incentivized to reduce costs through bundled payment initiatives, Accountable Care Organizations, and other policy measures, reductions in rehabilitative therapy provided by SNFs may be targeted. Our results offer important insights by demonstrating improvements in outcomes associated with increased quantities of therapy for most patients admitted to SNFs after hip fracture while also noting which patients are less likely to benefit from more therapy. Efforts to lower Medicare spending on postacute care services must be careful to avoid reducing therapy services that promote successful discharge.

Our study has limitations. First, our measure of the quantity of therapy was based on each patient's MDS assessment, which did not cover details of therapeutic interventions throughout the entire SNF stay and was not based on the actual hours of therapy delivered, as documented by the treating therapists. Our estimate reflected the average amount of therapy from the week before each MDS assessment and was not based on the total amount of therapy received across all days in the facility. However, we calculated the average quantity of therapy per week on the basis of all assessments, and this approach provided a more accurate characterization of therapy than relying solely on the initial assessments. Despite the fact that we did not have information on the clinical details of the therapy prescriptions, our measure of therapy minutes was based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' billing structure for SNFs, which accurately reflected the amounts of therapy. Next, our outcome measure was limited to the likelihood of returning to the community and considered only the first discharge location. In addition, our sample included only first-time SNF admissions to create a homogeneous sample. People with prior SNF stays were excluded because they may have differed from first-time SNF admissions in unobserved ways. For example, people who had multiple SNF stays in the past may have been in worse health. However, our approach may have led to the inclusion of a subset of older beneficiaries of Medicare who were generally in better health than other beneficiaries of the same age. Lastly, despite the use of several analytic techniques to mitigate bias, it is possible that certain unmeasured confounders influenced our results.

In conclusion, we identified upward trends in therapy quantity without notable concurrent increases in case mix in patients who had a new hip fracture and received care in SNFs. Importantly, increased therapy intensity was accompanied by a larger proportion of patients being discharged to home, suggesting better postacute outcomes. However, our findings indicate that increased therapy intensity in SNFs has not benefited all patients after hip fracture, as a higher likelihood of discharge to home was not observed for patients who were identified as having the highest impairment levels and whose need for therapy could be considered the greatest. Initiatives seeking to improve the quality of SNF care for patients after hip fracture should consider incentivizing increased therapy intensity for patients who are likely to benefit from it.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Dr Jung, Dr Trivedi, and Dr Mor provided concept/idea/research design. Dr Jung provided writing and project management. Dr Jung and Dr Mor provided data analysis. Dr Trivedi and Dr Grabowski provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

The study was approved by the Brown University Institutional Review Board.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R36 Health Services Research Dissertation Grant Award HS20756 to Dr Jung) and the National Institute on Aging (Program Project Grant 1P01AG027296, Shaping Long-Term Care in America, Principal Investigator: Dr Mor). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

References

- 1. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/mar14_entirereport.pdf?sfvrsn=0. March 2014 Accessed November 5, 2015.

- 2. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. A data book: health care spending and the Medicare program. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/publications/jun14databookentirereport.pdf?sfvrsn=1. June 2014 Accessed November 5, 2015.

- 3. Unruh MA, Trivedi AN, Grabowski DC, Mor V. Does reducing length of stay increase rehospitalization of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged to skilled nursing facilities? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garrett B, Wissoker DA. Modeling alternative designs for a revised PPS for skilled nursing facilities. Available at: http://www.urban.org/research/publication/modeling-alternative-designs-revised-pps-skilled-nursing-facilities. July 2008 Accessed November 5, 2015.

- 5. Grabowski DC, Afendulis CC, McGuire TG. Medicare prospective payment and the volume and intensity of skilled nursing facility services. J Health Econ. 2011;30:675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Office of Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services. Questionable billing by skilled nursing facilities. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-09-00202.pdf. December 2010 Accessed November 5, 2015.

- 7. Jette DU, Warren RL, Wirtalla C. Rehabilitation in skilled nursing facilities: effect of nursing staff level and therapy intensity on outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83:704–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jette DU, Warren RL, Wirtalla C. The relation between therapy intensity and outcomes of rehabilitation in skilled nursing facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirk-Sanchez NJ, Roach KE. Relationship between duration of therapy services in a comprehensive rehabilitation program and mobility at discharge in patients with orthopedic problems. Phys Ther. 2001;81:888–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen CC, Heinemann AW, Granger CV, Linn RT. Functional gains and therapy intensity during subacute rehabilitation: a study of 20 facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1514–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White C. Rehabilitation therapy in skilled nursing facilities: effects of Medicare's new prospective payment system. Health Affairs. 2003;22:214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/march-2012-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=0. March 2012 Accessed November 5, 2015.

- 13. Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Affairs. 2013;32:864–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morris JN, Hawes C, Fries BE, et al. Designing the National Resident Assessment Instrument for nursing homes. Gerontologist. 1990;30:293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gambassi G, Landi F, Peng L, et al. Validity of diagnostic and drug data in standardized nursing home resident assessments: potential for geriatric pharmacoepidemiology. Med Care. 1998;36:167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mor V, Intrator O, Unruh MA, Cai S. Temporal and geographic variation in the validity and internal consistency of the Nursing Home Resident Assessment Minimum Data Set 2.0. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, International Statistical Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9.htm.

- 18. Morgan RO, Virnig BA, DeVito CA, Persily NA. The Medicare-HMO revolving door: the healthy go in and the sick go out. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Unruh MA, Grabowski DC, Trivedi AN, Mor V. Medicaid bed-hold policies and hospitalization of long-stay nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1617–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grabowski DC, Feng Z, Intrator O, Mor V. Medicaid bed-hold policy and Medicare skilled nursing facility rehospitalizations. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1963–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M546–M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jung HY, Meucci M, Unruh MA, et al. Antipsychotic use in nursing home residents admitted with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murtaugh CM, Freiman MP. Nursing home residents at risk of hospitalization and the characteristics of their hospital stays. Gerontologist. 1995;35:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Castle NG, Mor V. Hospitalization of nursing home residents: a review of the literature, 1980–1995. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:123–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mor V, Intrator O, Fries BE, et al. Changes in hospitalization associated with introducing the Resident Assessment Instrument. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1002–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Intrator O, Castle NG, Mor V. Facility characteristics associated with hospitalization of nursing home residents: results of a national study. Med Care. 1999;37:228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carter MW, Porell FW. Variations in hospitalization rates among nursing home residents: the role of facility and market attributes. Gerontologist. 2003;43:175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Intrator O, Schleinitz M, Grabowski DC, et al. Maintaining continuity of care for nursing home residents: effect of states' Medicaid bed hold policies and reimbursement rates. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:33–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Freiman MP, Murtaugh CM. The determinants of the hospitalization of nursing home residents. J Health Econ. 1993;12:349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Intrator O, Grabowski DC, Zinn J, et al. Hospitalization of nursing home residents: the effects of states' Medicaid payment and bed-hold policies. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1651–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fries BE, Schneider DP, Foley WJ, et al. Refining a case-mix measure for nursing homes: Resource Utilization Groups (RUG-III). Med Care. 1994;32:668–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomas KS, Keohane L, Mor V. Local Medicaid home- and community-based services spending and nursing home admissions of younger adults. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e15–e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Newhouse JP, Garber AM. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1465–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.