Abstract

Excessive endogenous oxalate synthesis can result in calcium oxalate kidney stone formation and renal failure. Hydroxyproline catabolism in the liver and kidney contributes to endogenous oxalate production in mammals. To quantify this contribution we have infused Wt mice, Agxt KO mice deficient in liver alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase, and Grhpr KO mice deficient in glyoxylate reductase, with 13C5-hydroxyproline. The contribution of hydroxyproline metabolism to urinary oxalate excretion in Wt mice was 22 ± 2%, 42 ± 8% in Agxt KO mice, and 36% ± 9% in Grhpr KO mice. To determine if blocking steps in hydroxyproline and glycolate metabolism would decrease urinary oxalate excretion, mice were injected with siRNA targeting the liver enzymes glycolate oxidase and hydroxyproline dehydrogenase. These siRNAs decreased the expression of both enzymes and reduced urinary oxalate excretion in Agxt KO mice, when compared to mice infused with a luciferase control preparation. These results suggest that siRNA approaches could be useful for decreasing the oxalate burden on the kidney in individuals with Primary Hyperoxaluria.

1. Introduction

The Primary Hyperoxalurias (PH) are rare genetic diseases that result from an increased endogenous oxalate synthesis that leads to the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones and the deposition of calcium oxalate in tissues. There are 3 known forms of the disease. Type 1 results from mutations in the gene coding for alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT1); Type 2 in the gene coding for glyoxylate reductase (GRHPR); and Type 3 in the gene coding for 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase (HOGA1). We and others have developed animal models of these diseases which will be important for understanding the pathophysiology that occurs and for identifying and testing therapeutic strategies for treating the diseases [1, 2]. PH types 1 and 2 result in an inability to metabolize glyoxylate to glycine and glycolate, respectively (Fig. 1), leading to a build up of glyoxylate which can be further oxidized to oxalate by lactate dehydrogenase. Type 3 results from a deficiency in the aldolase that normally cleaves 4-hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate (HOG), a metabolite of hydroxyproline (Hyp), into pyruvate and glyoxylate. We have proposed that HOG can be split by a less efficient enzyme as the concentration of HOG increases and that the increased HOG concentration inhibits GRHPR activity [3].

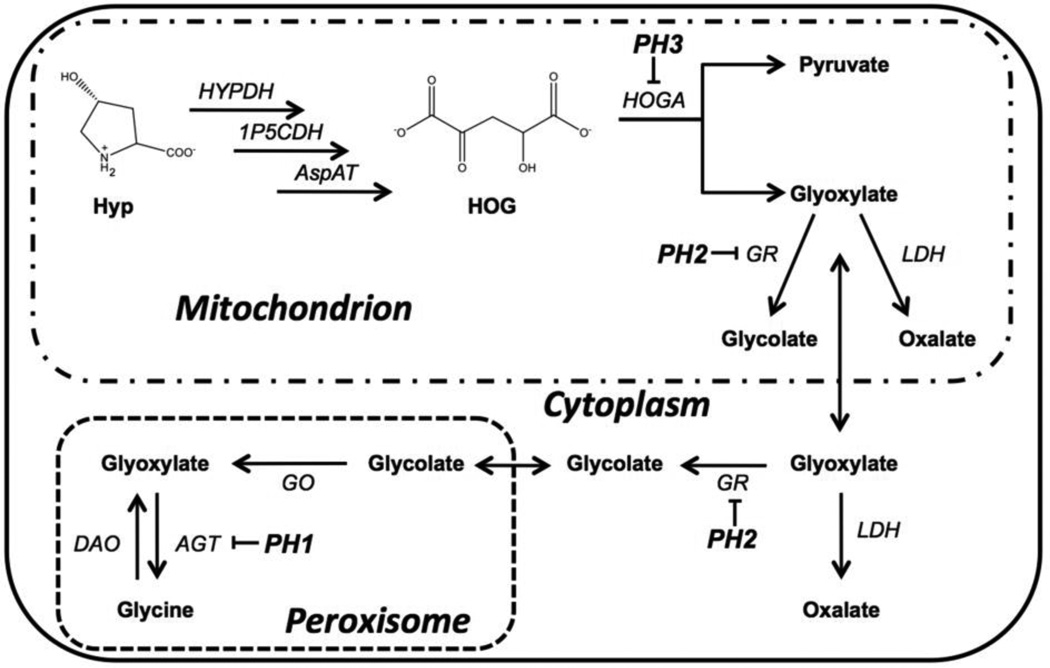

Figure 1.

The intersection between hydroxyproline and glyoxylate metabolic pathways. Hyp is acted upon by hydroxyproline dehydrogenase (HYPDH), 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase (1P5CDH), and aspartate aminotransferase in succession to give 4-hydroxy-2-oxogluatarate (HOG). HOG is cleaved by HOG aldolase (HOGA) to yield pyruvate and glyoxylate. Glyoxylate is converted to glycolate by glyoxylate reductase (GR) in both the mitochondrial and cytoplasmic compartments. Conversion of glycolate back into glyoxylate by glycolate oxidase (GO) in the peroxisome results in the formation of glycine via alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT). The enzymes mutated in PH1, PH2 and PH3 are indicated. The resulting rise in glyoxylate is shunted to oxalate formation by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). D-amino acid oxidase (DAO) can also convert Glycine into glyoxylate, but this path is considered to be minor.

Hydroxyproline metabolism occurs primarily in the liver and renal cortex [4]. This metabolism is believed to make a major contribution to endogenous oxalate synthesis [5, 6] as it results in the formation of glyoxylate, the immediate precursor of oxalate (Fig. 1). Daily collagen turnover, 2 – 3 g/day in adults, would result in the release of 300 – 450 mg of Hyp and the formation of 165 – 250 mg of glyoxylate/day [4]. Additional Hyp may be derived from the diet through the ingestion of meat, meat products and gelatin-containing foods. In this study we have measured the contribution that Hyp metabolism makes to oxalate synthesis in mouse models of PH1 (Agxt KO mouse) and PH2 (Grhpr KO mouse) by using a constant infusion of 13C5-labelled Hyp. We have also evaluated the potential of siRNAs targeting the synthesis of liver glycolate oxidase (GO or HAO1) or hydroxyproline dehydrogenase (HYPDH; also known as HPOX or PRODH2) formulated in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), to reduce urinary oxalate excretion in Agxt KO mice. Such LNPs are in use in clinical trials to test their efficacy [7]. They mimic lipoprotein nanoparticles in being taken by the liver via an endocytic process [8]. The siRNA targeting HYPDH will block the initial step in Hyp metabolism in mitochondria whereas the siRNA targeting GO will block a downstream step and prevent the synthesis of glyoxylate from glycolate in the liver (Fig. 1). The ability of such siRNAs to reduce urinary oxalate suggests that this approach is promising for the treatment of PH, particularly PH type I.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Reagent grade chemicals were obtained from either Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The synthesis of 13C5-15N-Hyp has been previously described; all carbon atoms substituted for 13C and the nitrogen atom for 15N [5]. Fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labelled sinistrin (FITC-S) was purchased from Fresenius Kabi Austria GmbH, Graz, Austria. Lipoid nanoparticles (LNPs) containing siRNA that specifically target liver GO and HYPDH were produced by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA.

2.2 Animals

The phenotype of Grhpr KO and Agxt KO mice has been previously described [1, 2]. Wild type (Wt) animals were strain C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory). Experimental animals were male and 12–15 weeks old. Mice were maintained in a barrier facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle and an ambient temperature of 23 ± 1°C and had free access to food and water. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

2.3 Metabolic Cage Collections

Animals (n=4 per strain) were equilibrated in Nalgene metabolic cages (Nalgene, Rochester, US) for 1 week and had free access to water and the custom purified diet TD.130032 (Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI) to which calcium chloride was added at 5 mg per gram dry diet. The custom purified diet has a low oxalate content (12.9 ± 1.1 µg oxalate per gram diet) and is devoid of Hyp. By weight, the diet contains 19.6% protein (whey protein isolate), 57.7% carbohydrate (maltodextrin and sucrose), 6.6% fat (lard and corn oil), and 10.3% cellulose [9]. 24-hour urines were collected on 1 ml mineral oil to prevent evaporation and 50 µl 2% sodium azide to prevent bacterial growth. Three to four 24-hour urines were performed for each mouse. Urine collections with creatinine values 25% lower/higher than mean values for each animal were considered incomplete/over collections and were discarded.

2.4 13C5-Hyp intravenous infusion

Wt and KO mice (n=4) under isoflurane anesthesia were catheterized via the jugular vein with a funnel catheter (Instech Lab Inc, PA), which was attached to a swivel (Instech Lab Inc, PA) and mounted to the metabolic cage. 13C5-Hyp was prepared in 0.9% saline containing FITC-S (0.5 mg/ml) and infused at a rate of 10 µmoles/hr/kg. FITC-S was included to ensure consistency of urine collections and infusion rate between animals. After a three day recovery period, three consistent 24 hr urines were collected from each animal in metabolic cages. 24 hour urines containing less than 75% of FITC-S infused were not included in the data analysis.

2.5 siRNA administration

Chemically modified GO, HYPDH and Luciferase siRNA were synthesized by Alnylam and characterized by anion-exchange HPLC. The LNPs were prepared using an ionizable lipid, disteroylphosphatidyl choline, cholesterol, and PEG-DMG using a spontaneous vesicle formation procedure. Nanoparticles for injection were diluted in sterile phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4, and a single dose (1mg/kg) delivered via a tail vein injection. Following siRNA administration, inhibition of liver GO and HYPDH protein and activity were determined over time by Western blot and enzymatic activity assays. 24 hour urines were collected on days 9 – 15 when GO and HYPDH protein expression were maximally knocked down.

2.6 Glomerular filtration rate

A miniaturized Non-Invasive-Clearance (NIC) technique to measure kidney function in conscious mice was applied to determine GFR, as previously described [10, 11]. The NIC-Kidney device (Mannhein Pharma and Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) allows for transcutaneous measurement of the elimination kinetics of the fluorescent renal marker FITC-S without surgery or blood and urine collection. Briefly, the NIC device was attached to the back of mice using a double-sided adhesive patch under anesthesia with 2% isoflurane. After a 5-min baseline recording, FITC-S (10–30 mg/100g body weight) was dissolved in 200 µl sterilized saline and administrated intravenously via the tail vein. Mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia and data were acquired for 90–120 minutes. The half-time of FITC-S elimination was determined using the established one compartment model and GFR was calculated.

2.7 Sample preparation

For oxalate determination, part of the urine collection was acidified to pH <1 with hydrochloric acid prior to storage at −80 °C to prevent any possible oxalate crystallization that could occur with cold storage and/or oxalogenesis associated with alkanization. The remaining non-acidified urine was frozen at −80 °C for the measurement of other urinary parameters. Plasma preparations were stored at −80 °C and filtered through Nano-sep centrifugal filters (VWR International, Batavia, IL) with a 10,000 nominal molecular weight limit (NMWL) prior to ion chromatographic analysis. Centrifugal filters were washed with 10mM HCl prior to sample filtration to remove any contaminating trace organic acids trapped in the filter device. Tissue was freeze clamped in liquid nitrogen immediately after sacrifice and stored at −80 °C.

2.8 Analytical Methods

Urinary creatinine was measured in non-acidified urine on a chemical analyzer, and oxalate in acidified urine by ion chromatography (IC), as previously described [1]. IC coupled with negative electrospray mass spectrometry (IC/MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA) was used to measure glycolate, 13C2-glycolate and 13C2-oxalate in acidified urines, as previously described [12]. The mole percent enrichment of 13C5-15N-Hyp in plasma was measured by gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy by Metabolic Solutions (Nashua, NH). FITC-S was measured as previously described [10, 11], after the urine was diluted ten-fold in 0.5 M Hepes buffer, pH 7.4. A Coomassie Plus protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard, was used to determine protein concentrations in tissue preparations.

2.9 Mitochondria isolation

Liver and kidney cortical tissue were homogenized in 0.5 mL Mitochondrial Isolation Buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Cat# 78410) using a glass dounce homogenizer. Mitochondria were isolated as previously described [13].

2.10 Enzyme Assays

Liver GO activity was measured by the formation of glyoxylate from glycolate in liver tissue lysates as previously described [14]. A Kinetex 2.6 µm C18 100 Å LC column (100 × 4.6 mm) (Phenomenex Inc, Torrance, CA) was used at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min, 20 °C, with UV detection at 320 nm to separate and measure the phenylhydrazone products. The mobile phase contained 0.1 M ammonium acetate, 4% acetonitrile and 4% methanol. Assays were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes before injection. HYPDH enzymatic activity in isolated mitochondria was measured as previously described [15]. Each assay contained 0.06 mg mitochondrial protein. The reaction product 3-OH-P5C was derivatized with o-aminobenzaldehyde (o-AB) and adduct formation monitored continuously at 443 nm over 60 minutes at 37 °C in a Syntek plate reader (Synergy HT Microplate Reader). Each sample was run in duplicate.

2.11 GO and HYPDH protein expression

Prior to GO Western blot analyses, liver tissue was homogenized in hypotonic lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.1, 0.1% Triton X-100). For HYPDH Western blot analyses, mitochondria were purified from liver tissue prior to analysis, as described above. The Western blot procedure and antibodies used have been previously described [5, 16]. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and voltagedependent anion channel (VDAC) were used as loading controls for GO and mitochondrial HYPDH, respectively.

2.12 Calculations

Fractional excretion of glycolate (FE-Glc) was calculated by determining GFR and plasma and urine glycolate concentrations in 24 urine collections from Wt and KO mice (Equation 1).

| (1) |

where P-Glc and U-Glc are plasma and urine glycolate molarity. V is 24 hour urine volume, and GFRv is the plasma volume filtered in 24 hours.

Whole body turnover rate (Qhyp) of Hyp and the contribution of Hyp catabolism to urinary oxalate and glycolate excretion were calculated as described in Equations 2 and 3, respectively.

| (2) |

where “i” is the tracer infusion rate in µmol/kg/hr and Ei /EHyp is the ratio of isotopic enrichment of the infusate (Ei) and plasma hydroxyproline (EHyp).

| (3) |

where EUox and EUGLc are the mole percent enrichment of urine with 13C2-oxalate and 13C2-glycolate, respectively.

2.13 Statistical analyses

Phenotyping differences among Wt, Agxt KO, and Grhpr KO mice with 13C5-Hyp intravenous infusion, and the effect of siRNA administration on urinary excretions among Luciferase, HYPDH and HAO1 siRNA were analyzed by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test if P<0.05. A Student’s t-test was used to compare data between baseline and post infusion, and to compare differences in GO and HYPDH activity, plasma glycolate and Hyp levels after siRNA administration relative to Luciferase siRNA. A paired t-test was used to compare data between baseline and post siRNA infusion in either WT or Agxt KO mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. The criterion for statistical significance was P < 0.05. Different superscripts indicate significant differences.

3. Results

3.1 Contribution of Hyp to plasma and urinary oxalate and glycolate

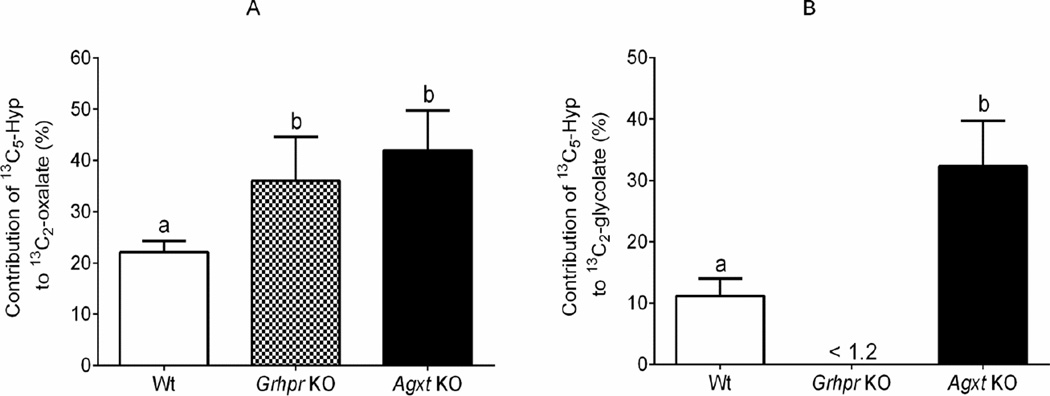

The characteristics of the mice used and their urinary excretions at baseline and with 13C5-Hyp infusion are shown in Table 1. Urinary oxalate excretion was higher in KO strains than in Wt mice, and glycolate was higher only in the Agxt KO strain, consistent with previous reports [1, 2]. The plasma Hyp level was similar before and after infusion. Urinary oxalate and glycolate also did not change during the 13C5-Hyp infusion compared to baseline values, supporting that the metabolic tracer did not alter metabolism. KO mice excreted significantly more urinary 13C2-oxalate than Wt animals. Urinary13C2-glycolate was not detectable in Grhpr KO mice, and Agxt KO mice excreted ~7 fold more 13C2-glycolate than Wt animals, as expected. Importantly, Hyp metabolism contributed ~40% to urinary oxalate in Agxt KO and Grhpr KO animals, and ~20% in Wt animals (Fig. 2A). The contribution of Hyp metabolism to urinary glycolate excretion was ~30% for the Agxt KO mice, a value ~3 fold greater than in Wt animals (Fig. 2B).

Table 1.

Plasma and 24-hour urine parameters at baseline and post 13C5-Hyp infusion in Wt, Grhpr KO, and Agxt KO micea.

| Group | Wt | Grhpr KO | Agxt KO | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 25.1 ± 0.9 | 26.7 ± 1.9 | 27.0 ± 1.6 | 0.233 |

| Baseline | ||||

| Urine volume (ml) | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.122 |

| Creatinine (mg) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.135 |

| Urinary oxalate (µg) | 32.9 ± 5.3a | 98.4 ± 26.4b | 147.7 ± 21.5c | 0.001 |

| Urinary glycolate (µg) | 54.4 ± 7.2a | 54.3 ± 10.2a | 165.2 ± 61.5b | 0.003 |

| Plasma Hyp (µM) | 17.6 ± 2.0 | 19.3 ± 5.2 | 23.5 ± 5.4 | 0.246 |

| Plasma glycolate (µM) | 25.7 ± 1.1a | 14.8 ± 1.7a | 318 ± 55b | 0.001 |

| GFR (µl/min) | 199 ± 23 | 207 ± 15 | 217 ± 6 | 0.324 |

| Post-infusion | ||||

| Urine volume(ml) | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 0.311 |

| Creatinine(mg) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.591 |

| FITC-S (% urinary recovery) | 83 ± 6 | 76 ± 6 | 84 ± 16 | 0.558 |

| Urinary oxalate (µg) | 49.3 ± 7.6a | 116.0 ± 17.6b | 170.4 ± 35.4c | 0.001 |

| Urinary 13C2-oxalate (µg) | 3.8 ± 0.8a | 14.3 ± 3.2b | 24.9 ± 7.7c | 0.001 |

| Urinary glycolate (µg) | 54.4 ± 7.5a | 61.6 ± 9.7a | 199 ± 44.4b | 0.001 |

| Urinary 13C2-(µg) | 2.1 ± 0.6a | <0.3 | 22.3 ± 8.8b | 0.004 |

| Plasma glycolate (µM) | 29.8 ± 5.6a | 13.7 ± 0.5b | 263 ± 11c | 0.001 |

| Plasma Hyp (µM) | 25.5 ± 6.5 | 26.8 ± 3.1 | 23.7 ± 3.6 | 0.643 |

| Plasma 13C5-Hyp (mole % enrichment) | 34.2 ± 6.0 | 34.5 ± 8.1 | 36.1 ± 3.1 | 0.917 |

| Whole body Hyp turnover rate (µmoles/hr/kg) | 18.2 ± 5.3 | 18.2 ± 5.4 | 16.2 ± 2.3 | 0.825 |

An independent t-test showed no difference between baseline and post 13C5-Hyp infusion in the assessed urinary parameters within each mouse strain. However, significant differences between the strains are indicated in bold-italics analyzed by one way ANOVA followed Tukey’s HSD test. Results presented are means ± SD. Values with different superscripts are significantly different (P <0.05).

Figure 2.

The contribution of hydroxyproline catabolism to urinary oxalate (panel A) and glycolate (panel B) in Wt, Grhpr KO and Agxt KO mice.. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test showed there were significant differences in contribution of 13C5-Hyp to urinary 13C2-oxalate (panel A, P = 0.011) and 13C2-glycolate (panel B, P<0.001). Results presented are means ± SD. Values with different superscripts are significantly different (P <0.05).

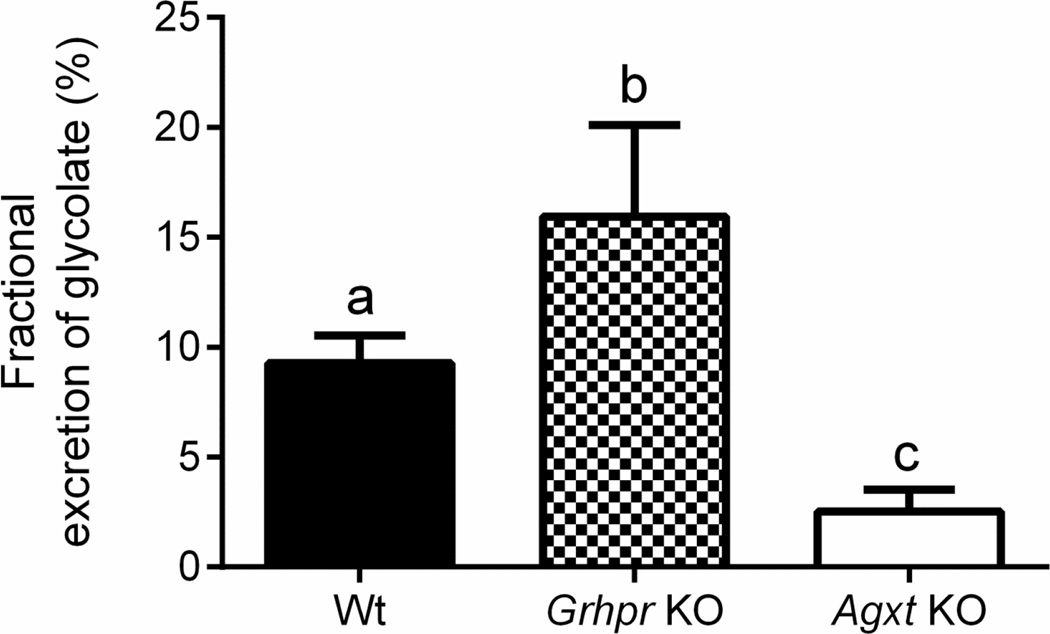

3.2 Low fractional glycolate excretion supports reabsorption with possible further metabolism

Given the high level of glycolate produced from Hyp, the fraction being excreted was calculated; it was low, ranging from 2 – 20% (Fig. 3). These values were significantly different between the strains and were highest in Grhpr KO mice and lowest in Agxt KO animals. The low clearance values indicate that the bulk of the glycolate filtered was reabsorbed and either re-entered the circulation or was metabolized in the kidney.

Figure 3.

The fractional excretion of glycolate is low. The percent fractional excretion of glycolate in Wt, Grhpr KO and Agxt KO mice was calculated using the GFR, plasma glycolate and urine glycolate values in Table 1. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test showed there was a significant difference in percent fractional excretion of glycolate in Wt, Grhpr KO and Agxt KO mice (P<0.001). Results presented are means ± SD. Values with different superscripts are significantly different (P <0.05).

3.3 siRNAs that target GO and HYPDH inhibit protein expression and activity

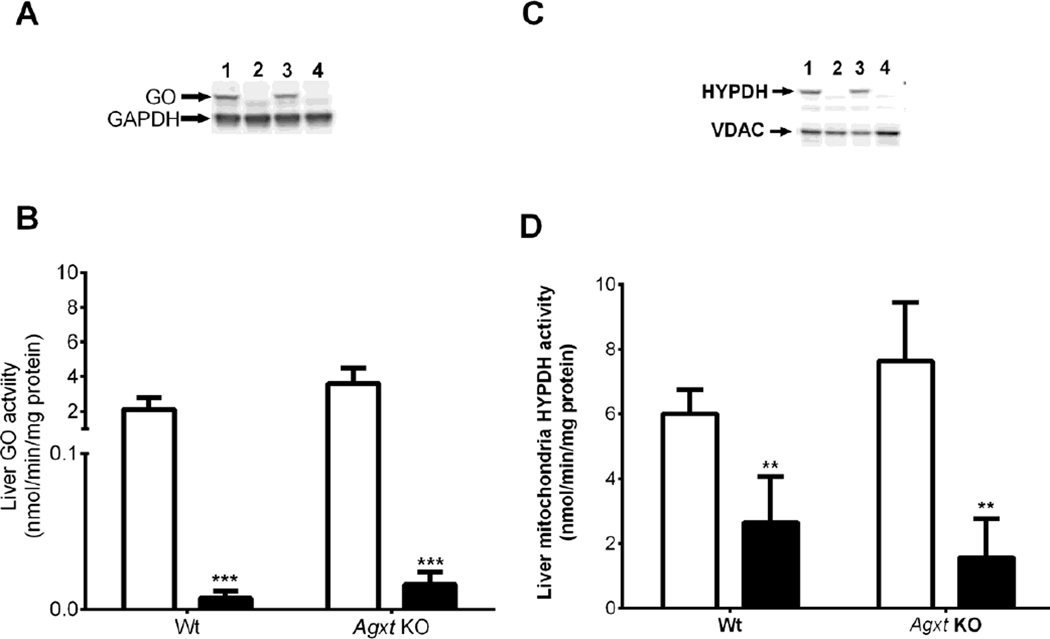

To determine the consequences of blocking Hyp and glycolate metabolism on urinary oxalate excretion, siRNA LNPs were developed to target the expression of mitochondrial HYPDH (PRODH2 gene), the first enzyme in Hyp metabolism, and peroxisomal GO (HAO1 gene), an intermediate step that converts glycolate to glyoxylate (Fig. 1). Importantly, these formulations deliver siRNAs specifically to hepatocytes. This approach has been shown to result in robust and durable reduction in genetic expression of a variety of hepatocyte targets across multiple species including humans [7, 8]. HAO1 siRNA administration resulted in almost complete knockdown of GO protein and activity in Wt and Agxt KO mice (Fig.4A and 4B). Intravenous administration of HYPDH siRNA resulted in greater than 90% knockdown of protein, and 50 – 70% reduction in mitochondrial HYPDH activity (Fig.4C and 4D). siRNA administration had no effect on Wt cortical kidney mitochondrial HYPDH activity (luciferase siRNA, 9.2 ± 2.0 nmol/min/mg protein; HYPDH siRNA, 7.9 ± 1.2 nmol/min/mg protein; P > 0.05), confirming hepatocyte targeting. Body weight did not change with siRNA treatment and no signs of toxicity were observed.

Figure 4. Knockdown of HAO1 and HYPDH using siRNA in LNPs.

A: Western blot of GO staining compared to GAPDH in liver tissue from Wt mice 15 days post luciferase siRNA (L1) or HAO1 siRNA (L2) administration, and from Agxt KO mice treated with luciferase siRNA (L3) or HAO1 siRNA (L4).

B: Liver GO activity in Wt and Agxt KO mice 15 days post luciferase siRNA (open bars) or HAO1 siRNA (filled bars) administration. C: Western blot of HYPDH staining compared to VDAC in liver mitochondria from Wt mice 15 days post luciferase siRNA (L1) or HYPDH siRNA (L2) administration, and from Agxt KO mice treated with luciferase siRNA (L3) or HYPDH siRNA (L4).

D: Liver HYPDH activity in Wt and Agxt KO mice 15 days post luciferase (open bars) or HYPDH siRNA (filled bars) administration. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, for comparisons between luciferase and HAO1 or HYPDH siRNA administration using a Student t-test. Results presented are means ± SD.

3.4 GO and HYPDH knockdown alters glycolate and oxalate levels

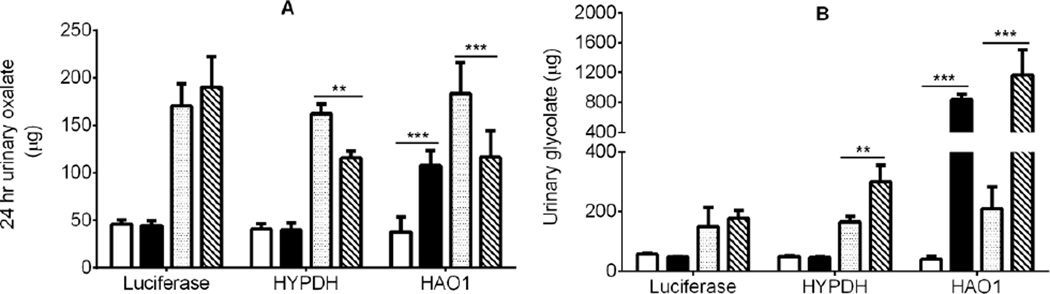

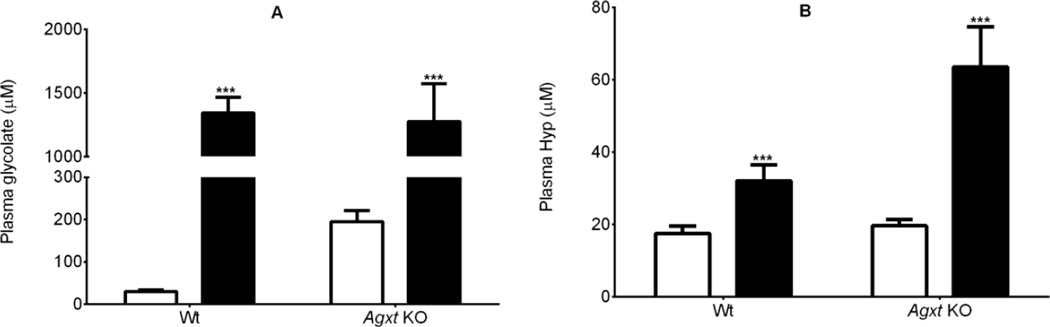

Both siRNA preparations significantly decreased urinary oxalate excretion in Agxt KO mice (Fig. 5A). The siRNA targeting HYPDH was without effect on urinary oxalate excretion in Wt mice, but the LNP preparation targeting GO unexpectedly increased oxalate excretion in these mice. Urinary glycolate excretion increased in Agxt KO mice with both LNPs: 2-fold higher with HYPDH siRNA and 6-fold higher with HAO1 siRNA (Fig. 5B). In Wt mice, glycolate excretion was unaffected by HYPDH knockdown, but increased 21-fold with GO knockdown (Fig. 5B). Plasma glycolate and plasma Hyp increased significantly after HAO1 and HYPDH siRNA administration, respectively in both Wt and Agxt KO mice (Fig.6A and 6B).

Figure 5.

The effect of the knockdown of HYPDH and GO in Agxt KO mice on urinary oxalate (panel A) and glycolate (panel B) excretion. Wt baseline, open bars; Wt post siRNA, black bars. Agxt KO baseline, dotted bars; Agxt KO post siRNA, diagonal lines. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 between baseline and post siRNA treatment analyzed by paired t-test. Results presented are means ± SD.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of GO and HYPDH in Wt and Agxt KO mice increased plasma glycolate (A), and Hyp levels (B). Luciferase siRNA, open bars; HAO1 siRNA (panel A) and HYPDH siRNA (panel B), black bars. *** P<0.001 between Luciferase siRNA and HAO1/HYPDH siRNA analyzed by Student t-test. Results presented are means ± SD.

DISCUSSION

Hyp is synthesized de novo in collagen by the hydroxylation of specific proline residues. Collagen turnover is estimated to be 2 – 4 g/day [4]. This would result in 260 – 520 mg Hyp being released into the circulation. Additional Hyp is obtained from the diet following the ingestion of meat and gelatin-containing products. Less than 50 mg of Hyp, mainly as peptides, is excreted in urine each day, illustrating that the bulk of the Hyp entering the circulation is metabolized. Each mole of Hyp is broken down (Fig. 1) to one mole of pyruvate and one mole of glyoxylate, the immediate precursor of oxalate [4, 17]. Several studies have shown that Hyp metabolism contributes to the amount of oxalate and glycolate that is excreted in urine by mammals [6, 18]. Quantifying this contribution is important for identifying possible therapeutic targets for reducing urinary oxalate excretion in individuals who form calcium oxalate stones and those with PH.

The infusion of tracer levels of 13C5-Hyp in Wt mice and mouse models of PH (Table 1), revealed that Hyp metabolism makes a major contribution to oxalate excretion. Hyp contributes up to 20% of urinary oxalate in Wt mice which increases to ~40% in Agxt KO and Grhpr KO mice. This change in metabolism illustrates the importance of AGT1 and GR in the mouse in limiting the amount of glyoxylate that could become available for conversion to oxalate. The mouse has evolved to express AGT1 in both mitochondria and peroxisomes in contrast to humans who only express it in peroxisomes [19]. The presence of AGT1 in murine mitochondria alters their metabolism of Hyp. Fig. 2 indicates that in Wt mice the metabolism of 13C5-Hyp contributes ~10% of the glycolate excreted in urine. By comparison we have found in normal human subjects 13C5-Hyp metabolism contributes up to 65% of the glycolate excreted in urine (unpublished results). This species difference is compatible with mitochondrial AGT1 in mice converting a significant portion of the 13C2-glyoxylate formed from 13C5-Hyp to 13C2-glycine.

In the Wt mouse, Hyp metabolism contributed to 20% of the oxalate excreted in urine (Fig. 2). Treatment of these mice with siRNA that targeted the expression of GO greatly decreased GO activity, increased the urinary excretion of glycolate 20-fold and increased urinary oxalate excretion more than 2-fold (Fig. 5). It is possible that this increase in oxalate excretion is related to the oxidation of glycolate to oxalate in a pathway not involving GO and we discuss below that this could occur in the kidney. Treatment of Agxt KO mice with siRNA targeting GO activity significantly decreased urinary oxalate excretion, but substantially increased urinary glycolate excretion (Fig. 5). Urinary oxalate excretion did not normalize and approach that of Wt untreated mice presumably because of the contribution of glycolate oxidation to oxalate that was not due to GO activity.

Major pathways that contribute to the endogenous synthesis of oxalate other than Hyp metabolism have not yet been clearly identified. Minor contributions are provided by the metabolism of the amino acids, glycine, phenylalanine and possibly tryptophan [12]. The breakdown of ascorbate may also produce oxalate nonenzymatically but its contribution is uncertain [20]. We have suggested that glyoxal, a dialdehyde product of lipid peroxidation and glucose autooxidation, could be an important source and have recently described a pathway in erythrocytes that could result in the conversion of glyoxal to oxalate [21]. This pathway could also account for a significant portion of the glycolate synthesized in the body as the bulk of the glyoxal formed in cells and tissues is converted to glycolate by the glyoxalase system. Therefore, at this time HYPDH and GO appear to be the best targets for reducing the production of glyoxylate and oxalate in PH patients.

GO has been viewed as a target for blocking endogenous glyoxylate and oxalate synthesis for some time [4, 17, 22–24]. Given the considerable daily turnover of Hyp, we have also proposed that HYPDH could also be an effective target as its inhibition would block Hyp metabolism and glyoxylate production [15]. The identification of individuals who lack GO or HYPDH activity, without any identifiable accompanying pathology, suggests they could be safe therapeutic targets [25–27]. The young child (8 yrs) described with mutations in GO presented with excessive glycolate excretion, but normal oxalate levels and no evidence of kidney stones or nephrocalcinosis [19]. The child also had a Triple A-like syndrome due to homozygous mutations in GMPPA, and it is possible that this syndrome could cause alterations in metabolism.

LNPs have proven to be effective carriers for delivering siRNAs that specifically target and lower the expression of liver proteins in multiple species [7, 28, 29]. LNPs containing siRNAs targeting HYPDH and GO (HYPDH and HAO1 genes) were effective in lowering the expression of their target enzymes in the liver of Wt and Agxt KO mice (Fig. 4). While the level of GO activity was consistent with this knockdown, higher than expected levels of HYPDH activity were detected. This response could be due to the non-specificity of o-aminobenzaldehyde in reacting with 3-OH-P5C, the product of Hyp metabolism. Both siRNAs significantly decreased oxalate excretion in the KO animals (Fig. 5A), indicating the potential for targeting these enzymes to lower urine oxalate in individuals with PH. Optimizing the conditions to maximize inhibition over an extended period of time is warranted and is under investigation. It also may be possible to use a co-treatment with both siRNAs to enhance their effects.

Interestingly, there was no reduction in urinary oxalate excretion in Wt animals following HYPDH knockdown by siRNA despite the >20% contribution of Hyp metabolism to urinary oxalate excretion (Fig. 5A). One possible explanation is that Hyp metabolism in the kidney compensated for that normally occurring in the liver as the siRNAs target only liver enzymes. Another unexpected observation was the doubling of the oxalate produced in the Wt mice upon GO knockdown. In addition, urinary and plasma glycolate were increased 21- and 50-fold with this treatment (Fig.5B and 6A). Taken together, these results indicate that a substantial reabsorption of glycolate occurred in the kidney and exceeded the ~90% reabsorption observed in untreated Wt animals (Fig. 3). The bulk of this glycolate may have re-entered the circulation but it is also possible that metabolism of glycolate occurs in the kidney with oxalate as a possible product. We have also observed that isolated mouse proximal tubules can convert added glycolate to oxalate (unpublished observations). Furthermore, a reduced but still significant amount of oxalate was synthesized from glycolate in hepatectomized rats, suggesting extra-hepatic oxalate production which could partly involve the kidney [30]. It is quite possible that metabolism of glycolate to oxalate occurred in Wt animals treated with siRNA targeting GO due to the high filtered load of glycolate (Fig. 6A), and that this contributed to the doubling of urinary oxalate excretion (Fig. 5A).

A significant amount of glycolate in humans also may be metabolized to oxalate in the kidney. We have reported that the clearance ratio of glycolate to creatinine is ~0.5, indicating substantial reabsorption which would support possible renal metabolism [6]. The metabolism of glycolate in the kidneys of both rodents and primates warrants further investigation to examine the implications of the increased production of glycolate.

One limitation of these studies is that the metabolism of Hyp in the mouse differs in some ways from that in humans. Whole body Hyp turnover in these mice was 18 µmoles/hr/kg, which is ~5 times higher than we have determined in humans when normalized by body weight [unpublished results]. There are also differences in the expression of enzymes involved in oxalate synthesis as well as their subcellular compartmentalization. Mouse liver contains much less AGT1 than human liver, and it is localized in both mitochondria and peroxisomes [19]. Furthermore, the expression of AGT1 in mitochondria increases as dietary protein increases [31]. Thus, in the mouse, a substantial amount of the glyoxylate produced from Hyp metabolism in mitochondria will be converted to glycine, in contrast to human mitochondria where the bulk of the glyoxylate may be converted to glycolate by GR activity. A small portion could also feasibly be converted to oxalate by mitochondrial LDH.

There are currently no therapies for PH other than pyridoxine administration for a minority of patients who fully or partially respond to this treatment. The use of RNAi therapeutics to specifically block enzymes that contribute to the excessive oxalate synthesis that occurs in PH holds promise as a novel and effective therapy.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Hydroxyproline metabolism in mice contributes significantly to oxalate synthesis

The contribution is greater in Agxt and Grhpr KO mice than in wild type mice

Decreasing hepatic GO and HYPDH expression decreases oxalate excretion

RNAi therapeutics could be helpful in treating Primary Hyperoxaluria

Acknowledgements

The technical assistance of Zhixin Wang and Song Lian Zhou was greatly appreciated. This work was supported by NIH grants DK054468, DK079337, DK083527 and HL098135 and a grant from the Oxalosis and Hyperoxaluria Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Knight J, Holmes RP, Cramer SD, Takayama T, Salido E. Hydroxyproline metabolism in mouse models of primary hyperoxaluria, American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2012;302:F688–F693. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00473.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salido EC, Li XM, Lu Y, Wang X, Santana A, Roy-Chowdhury N, Torres A, Shapiro LJ, Roy-Chowdhury J. Alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase-deficient mice, a model for primary hyperoxaluria that responds to adenoviral gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18249–18254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riedel TJ, Knight J, Murray MS, Milliner DS, Holmes RP, Lowther WT. 4-Hydroxy-2-oxoglutarate aldolase inactivity in primary hyperoxaluria type 3 and glyoxylate reductase inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phang JM, Hu CA, Valle D. Disorders of proline and hydroxyproline metabolism. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Vallee D, Childs B, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 1821–1838. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang J, Johnson LC, Knight J, Callahan MF, Riedel TJ, Holmes RP, Lowther WT. Metabolism of [13C5]hydroxyproline in vitro and in vivo: implications for primary hyperoxaluria, American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302:G637–G643. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00331.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knight J, Jiang J, Assimos DG, Holmes RP. Hydroxyproline ingestion and urinary oxalate and glycolate excretion. Kidney international. 2006;70:1929–1934. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coelho T, Adams D, Silva A, Lozeron P, Hawkins PN, Mant T, Perez J, Chiesa J, Warrington S, Tranter E, Munisamy M, Falzone R, Harrop J, Cehelsky J, Bettencourt BR, Geissler M, Butler JS, Sehgal A, Meyers RE, Chen Q, Borland T, Hutabarat RM, Clausen VA, Alvarez R, Fitzgerald K, Gamba-Vitalo C, Nochur SV, Vaishnaw AK, Sah DW, Gollob JA, Suhr OB. Safety and efficacy of RNAi therapy for transthyretin amyloidosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Y, Love KT, Dorkin JR, Sirirungruang S, Zhang Y, Chen D, Bogorad RL, Yin H, Chen Y, Vegas AJ, Alabi CA, Sahay G, Olejnik KT, Wang W, Schroeder A, Lytton-Jean AK, Siegwart DJ, Akinc A, Barnes C, Barros SA, Carioto M, Fitzgerald K, Hettinger J, Kumar V, Novobrantseva TI, Qin J, Querbes W, Koteliansky V, Langer R, Anderson DG. Lipopeptide nanoparticles for potent and selective siRNA delivery in rodents and nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3955–3960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322937111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Ellis ML, Knight J. Oxalobacter formigenes colonization and oxalate dynamics in a mouse model. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:5048–5054. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01313-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schock-Kusch D, Geraci S, Ermeling E, Shulhevich Y, Sticht C, Hesser J, Stsepankou D, Neudecker S, Pill J, Schmitt R, Melk A. Reliability of transcutaneous measurement of renal function in various strains of conscious mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e71519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber A, Shulhevich Y, Geraci S, Hesser J, Stsepankou D, Neudecker S, Koenig S, Heinrich R, Hoecklin F, Pill J, Friedemann J, Schweda F, Gretz N, Schock-Kusch D. Transcutaneous measurement of renal function in conscious mice. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2012;303:F783–F788. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00279.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight J, Assimos DG, Callahan MF, Holmes RP. Metabolism of primed, constant infusions of [1,2-(13)C(2)] glycine and [1-(13)C(1)] phenylalanine to urinary oxalate. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2011;60:950–956. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mickelson JR, Greaser ML, Marsh BB. Purification of skeletal-muscle mitochondria by densitygradient centrifugation with Percoll. Analytical biochemistry. 1980;109:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker PR, Cramer SD, Kennedy M, Assimos DG, Holmes RP. Glycolate and glyoxylate metabolism in HepG2 cells. Amer J Physiol. 2004;287:C1359–C1365. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00238.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summitt CB, Johnson LC, Jonsson TJ, Parsonage D, Holmes RP, Lowther WT. Proline dehydrogenase 2 (PRODH2) is a hydroxyproline dehydrogenase (HYPDH) and molecular target for treating primary hyperoxaluria. The Biochemical journal. 2015;466:273–281. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behnam JT, Williams EL, Brink S, Rumsby G, Danpure CJ. Reconstruction of human hepatocyte glyoxylate metabolic pathways in stably transformed Chinese-hamster ovary cells. The Biochemical journal. 2006;394:409–416. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes RP, Assimos DG. Glyoxylate synthesis, and its modulation and its influence on oxalate synthesis. The Journal of urology. 1998;160:1617–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandel NS, Henderson JD, Hung LY, Wille DF, Wiessner JH. A porcine model of calcium oxalate kidney stone disease. The Journal of urology. 2004;171:1301–1303. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110101.41653.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danpure CJ, Fryer P, Jennings PR, Allsop J, Griffiths S, Cunningham A. Evolution of alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase 1 peroxisomal and mitochondrial targeting. A survey of its subcellular distribution in the livers of various representatives of the classes Mammalia, Aves and Amphibia. European journal of cell biology. 1994;64:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nemet I, Monnier VM. Vitamin C degradation products and pathways in the human lens. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37128–37136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange JN, Wood KD, Knight J, Assimos DA, Holmes RP. Glyoxal formation and its role in endogenous oxalate synthesis. Advances in urology. 2012;2012:819202. doi: 10.1155/2012/819202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes RP. Pharmacological approaches in the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria. Journal of nephrology. 1998;11(S-1):32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray MS, Holmes RP, Lowther WT. Active site and loop 4 movements within human glycolate oxidase: implications for substrate specificity and drug design. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2439–2449. doi: 10.1021/bi701710r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rooney CS, Randall WC, Streeter KB, Ziegler C, Cragoe EJ, Schwam H, Michelson SR, Williams HWR, Eichler E, Duggan DE, Ulm EH, Noll RM. Inhibitors of glycolate oxidase. 4-Substituted 3-hydroxy-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione derivatives. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 1983;26:700–714. doi: 10.1021/jm00359a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efron ML, Bixby EM, Pryles CV. Hydroxyprolinemia. Ii. A Rare Metabolic Disease Due to a Deficiency of the Enzyme "Hydroxyproline Oxidase". The New England journal of medicine. 1965;272:1299–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196506242722501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frishberg Y, Zeharia A, Lyakhovetsky R, Bargal R, Belostotsky R. Mutations in HAO1 encoding glycolate oxidase cause isolated glycolic aciduria. J Med Genet. 2014;51:526–529. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelkonen R, Kivirikko KI. Hydroxyprolinemia: an apparently harmless familial metabolic disorder. The New England journal of medicine. 1970;283:451–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197008272830903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank-Kamenetsky M, Grefhorst A, Anderson NN, Racie TS, Bramlage B, Akinc A, Butler D, Charisse K, Dorkin R, Fan Y, Gamba-Vitalo C, Hadwiger P, Jayaraman M, John M, Jayaprakash KN, Maier M, Nechev L, Rajeev KG, Read T, Rohl I, Soutschek J, Tan P, Wong J, Wang G, Zimmermann T, de Fougerolles A, Vornlocher HP, Langer R, Anderson DG, Manoharan M, Koteliansky V, Horton JD, Fitzgerald K. Therapeutic RNAi targeting PCSK9 acutely lowers plasma cholesterol in rodents and LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11915–11920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805434105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann TS, Lee AC, Akinc A, Bramlage B, Bumcrot D, Fedoruk MN, Harborth J, Heyes JA, Jeffs LB, John M, Judge AD, Lam K, McClintock K, Nechev LV, Palmer LR, Racie T, Rohl I, Seiffert S, Shanmugam S, Sood V, Soutschek J, Toudjarska I, Wheat AJ, Yaworski E, Zedalis W, Koteliansky V, Manoharan M, Vornlocher HP, MacLachlan I. RNAi-mediated gene silencing in nonhuman primates. Nature. 2006;441:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature04688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farinelli MP, Richardson KE. Oxalate synthesis from [14C1]glycolate and [14C1]glyoxylate in the hepatectomized rat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;757:8–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(83)90146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takayama T, Fujita K, Suzuki K, Sakaguchi M, Fujie M, Nagai E, Watanabe S, Ichiyama A, Ogawa Y. Control of oxalate formation from L-hydroxyproline in liver mitochondria. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2003;14:939–946. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000059310.67812.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]